#chevalière d'eon

Text

"It should be noted here that our heroine's mother and sister, certainly better informed than anyone, had suddenly corrected their language. Her sister, who had married the Chevalier O'Gorman, sent a letter to London, dated July 15, 1777, to "Monsieur le Chevalier d'Eon, former Minister Plenipotentiary of France, in London at M. Lautrem, Brenner Street, Golden Square", and she named the recipient "mon cher frère". After long confessions about certain household difficulties, Mme O'Gorman expressed the hope of soon seeing her brother again in Tonnerre, said that their mother had the same wish, and ended, speaking of this long-promised return, with these words a little enigmatic: "Warn us, be sure of the secret!"

But, from the return to France of the chevalière and the public declaration of her female sex, the language of the mother and the sister changes absolutely. It is a daughter and a sister to whom these ladies address without hesitation, and it seems that for them no dispute is possible in this regard. Thus, on January 19, 1778, Mme d'Eon had Mme O'Gorman write for her, and signed a long letter addressed to "Mademoiselle la chevalière d'Eon", in which she constantly referred to her as "ma chère fille".

Finally, the chevalier O'Gorman, who seems to have been very actively involved in the affairs and occupations of his sister-in-law, the chevalière, and to have maintained a very close correspondence with her, never calls her anything other than "ma chère sœur", even in the most confidential communications."

~ La Chevalière d'Éon a Versailles by Paul Fromageot published in Le Carnet Historique & Littéraire, 1 Jan 1901, (translated with google translate)

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every time someone uses he/him pronouns for d’Eon or just flat out calls her a man, I lose about 5 years off my life smh

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

When you're looking into LGBTQ+ history, one essential stop is the Chevalière D'Éon (5 October 1728 – 21 May 1810)

This isn't exactly a rousing and triumphant narrative, but it has a few small wins. It's proof, in my mind, that the transgender experience is far from a modern invention.

In 1762, a 33-year-old French cavalry officer, diplomat, and spy arrived in London to draft the treaty that would end the Seven Years' War between England and France. They had spied in the Imperial court of Russia as a woman, and commanded dragoons in combat as a man.

London was an uneasy home, since part of their work was to gather intelligence for a potential French invasion of England (among other matters) but it became a familiar one. For years this aristocrat, presenting as male, socialized with the English nobility, gambled, and politicked in the shadows. For a period, they were both showered money and honours from the French crown, and considered in possession of too many incriminating secrets to be permitted to return to France.

Then in 1777, at the age of 49, they made an explosive announcement: Although assigned male at birth, the Chevalière declared that she was a woman, and began presenting and living as such. The French monarchy never allowed her to return to Court in Versailles, but they did fund a new aristocratic wardrobe of feminine clothes. In 1785, she returned to England, and lived as a woman for the rest of her life—albeit a woman who participated in fencing exhibitions until she was injured at the age of 68 and had to stop. She died in London in 1810.

Like I said, there are sad parts to the story. She never got to go home; she ended up horribly in debt, old, and disabled, living with a poor widow. Some people saw her transition as an insincere and cowardly attempt to dodge the issues of politics and personal honour that bedeviled her back in France. She was subjected to all the mockery and social opprobrium that came with failing to be fully masculine before her transition, and failing to be fully feminine after it.

Whenever I come across the Chevalière, I love her as one fencer loves to see another excel. I love her for her daring and versatility, her willingness to be seen in the face of opposition. I ache inside for all the things she never got to do or see—the community she didn't get to have. She's such a vibrant figure, and so poorly-served by her environment.

I wish we had her with us now. I hope we'll at least have her heirs.

123 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you think Laurens was asexual?

I have no reason to think so, and there isn’t really any evidence besides.

People in the 18th century didn’t record their sexual activity all that often - and consider that most of Laurens’ existing correspondence is addressed to family or related to the war effort, it’s not where you would expect him to express or hint at sexual activity. The only “verifiable” evidence that sex had happened was the conception of children, so we can say with some certainty that Laurens had sex at least once in his life (for all the good that does us - or him).

If you’re basing your question on Henry’s 1767 observation that John was too focused on his studies to show any interest in girls, that could be read in several different ways that don’t suggest a general disinterest in sex - perhaps he was just a late bloomer (he was only 13, after all), didn’t show any specifically heterosexual attraction, or was simply good enough at hiding his interest (in boys or girls) from his very busy father.

By 1773, Henry is moralising to John about the dangers of sexual transgression - referring to the cases of John’s cousin Molsy Bremar (a victim of rape and abuse by her brother in law Egerton Leigh) and Henry Bartholomew Himeli (one of John’s Charleston tutors, who started an indiscreet affair with “little Freckled Face ordinary Wench” and thereby damaged his reputation and social standing). So Henry must have had at least some cause to share these warnings.

Another consideration is that Laurens would simply not have had many opportunities early in life to engage in sexual relationships. Casual sex is risky in this context, and ‘dating’ is not really a concept that exists at the time. If you are courting someone, you are indicating a serious intention to marry them - and if that is not your intention, then you typically do your best to avoid getting them pregnant.

Before 1771, Laurens lived with his family in Charleston, often out at Mepkin, and then was taken to London for his schooling. It’s only when he moved to Geneva in 1772 that he would have been under a bit less parental supervision, though still living with a watchful family, and busy with his studies and supervising Harry. We only have snapshots of the two years he spent here, and if he did have romantic attachments, it’s likely this would have been confined to his circle of male friends (again, not something you’d write home about).

Back in London in late 1774, Laurens is thrown into his legal studies, family drama and rising political tensions, which consume him. Still, Laurens gets to know Martha Manning during this time, and by early-to-mid 1776 they are engaging in a sexual relationship (One-night stand? Ongoing tryst? We just don’t know.). Then, of course, he leaves for America and almost immediately joins the war effort, leaving little time for romantic or sexual encounters beyond the immediate sphere of Washington’s staff.

Given the lack of any meaningful observations suggesting disinterest to sex, the less-than-favourable conditions for finding a sexual partner, and the fact that Laurens did engage in a sexual relationship with Martha Manning at the first reasonable opportunity, I don’t see any reason to think he was asexual.

If, however, you are looking for an asexual icon from the time period, look no further than the Chevalière d'Eon - @thelittlelionofvalleyforge has you covered there.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

mfw there's zero ac: unity fics on the archive including the chevalière d'eon despite the fact that she is cool as hell

#len speaks#guess i gotta write everything myself!#i just want a fic of her bonding with arno over gender expression okay!#ALSO bonding over cloak and dagger stuff would be cool bc she was a legit spy and he's an assassin so they're p similar!!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

We need to change the angle from which we approach queer historical figures.

Considering d'Eon's Amazonian gender presentation would she identify as nonbinary if she was alive today?

Bad question! Focuses on the unknowable and teaches us nothing about queer history.

What is the cultural significance of the social role of the Amazon and what does it tell us about how gender was understood in 18th century France and England? Does it suggest that gender wasn't seen as a strict binary and was in fact a spectrum? If so how did d'Eon fit into this gender spectrum and what do her writings on gender reveal about 18th century gender?

Good questions! Actually asks us to think about queer history!

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

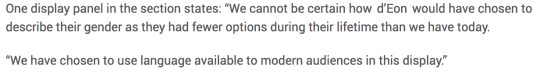

National Portrait Gallery this is bad history. We know how d'Eon chose to describe her gender during her lifetime. Understanding queer history involves understanding how queer people lived historically and understood themselves historically. It doesn't matter what pronouns d'Eon may have chosen had she lived today it matters what pronouns she used in her lifetime. You are placing modern language on a historical figure when we know what language she used historically.

#chevalière d'eon#queer history#this is from the Telegraph article 'National Portrait Gallery using gender-neutral pronouns to refer to 18th-century 'trans' spy'#if anyone wants to read it

235 notes

·

View notes

Text

The thing that gets me about people saying that we don't know what d'Eon's pronouns were is that we actually have much better information on her pronouns than we do for most historical figures.

Take Princess Seraphina for example. Most of what we know about Seraphina comes from the trial of Thomas Gordon (5 July 1732). In the trial some witnesses who knew Seraphina use she/her pronouns. For example this is how Mary Poplet talks about the Princess:

I have known her Highness a pretty while, she us’d to come to my House from Mr. Tull, to enquire after some Gentlemen of no very good Character; I have seen her several times in Women’s Cloaths, she commonly us’d to wear a white Gown, and a scarlet Cloak, with her Hair frizzled and curl’d all round her Forehead; and then she would so flutter her Fan, and make such fine Curties, that you would not have known her from a Woman: She takes great Delight in Balls and Masquerades, and always chuses to appear at them in a Female Dress, that she may have the Satisfaction of dancing with fine Gentlemen. Her Highness lives with Mr. Tull in Eagle-Court in the Strand, and calls him her Master, because she was Nurse to him and his Wife when they were both in a Salivation; but the Princess is rather Mr. Tull’s Friend, than his domestick Servant. I never heard that she had any other Name than the Princess Sraphina.

However others use he/him pronouns, this is how Mary Robinson talks about Seraphina:

I was trying on a Suit of Red Damask at my Mantua-maker’s in the Strand, when the Princess Seraphina came up, and told me the Suit look’d mighty pretty. I wish, says he, you would lend ‘em me for a Night, to go to Mrs. Green’s in Nottingham-Court, by the Seven Dials, for I am to meet some fine Gentlemen there. Why, says I, can’t Mrs. Green furnish you? Yes, says he, she lends me a Velvet Scarf and a Gold Watch sometimes. He used to be but meanly dress’d, as to Men’s Cloaths, but he came lately to my Mantua-maker’s, in a handsome Black Suit, to invite a Gentlewoman to drink Tea with Mrs. Tull. I ask’d him how he came to be so well Rigg’d? And he told me his Mother had lately sold the Reversion of a House; And now, says he, I’ll go and take a Walk in the Park, and shew my self.

So what do we make of this? Did Seraphina use both he/him and she/her pronouns or is Robinson misgendering Seraphina? This is an issue we unfortunately have when talking about queer people we have very little information on. We can guess at the answer but we can't know for sure.

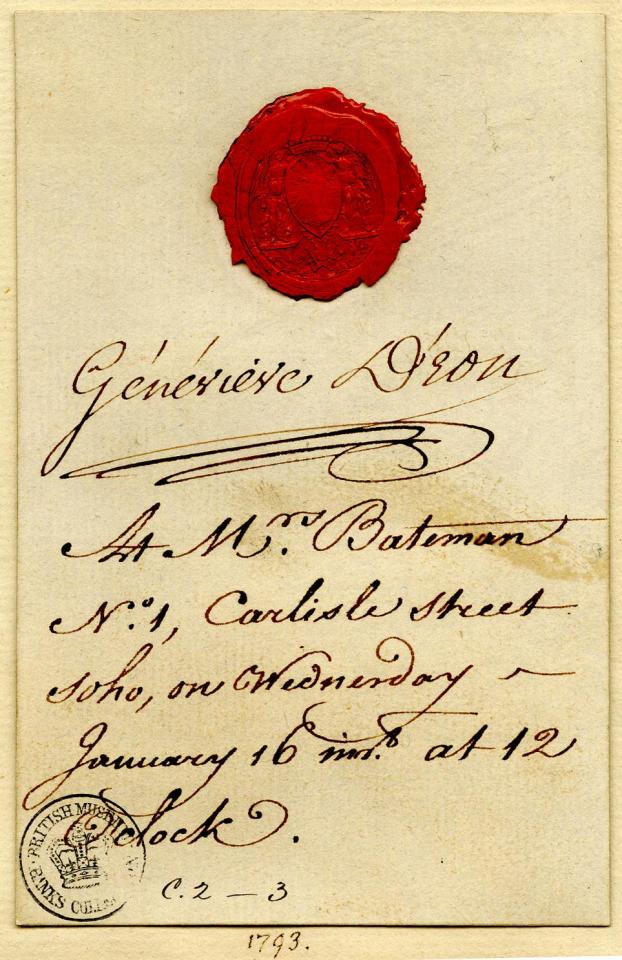

But with d'Eon not only do we know that her friends, family and most of the English public used she/her pronouns for her but we even have examples of d'Eon using she/her pronouns for herself when writing in third person. This is probably the best evidence we are ever going to get for someone of this period. It's an amazingly clear source for the pronoun question. Like wow there's the answer right there in ink on paper.

[Invitation from the Chevalière d’Eon to Lord Besborough c.1791, via The British Museum (D,1.268-272)]

244 notes

·

View notes

Text

The way people talk about d'Eon is a really good example of how trans people are held to more restrictive expectations of gender conformity. Whether it's d'Eon talked like a grenadier and thus must have been a cis man forced to live as a woman or d'Eon's gender presentation was amazonian thus we must use they/them pronouns and masculine language in French and also deadname her it's all making assumptions about d'Eon's gender identity based on her gender presentation. It's all making the assumption that d'Eon can't have been a woman because she doesn't fit their expectations of how a woman should behave. The fact that d'Eon said she was a woman and used feminine names, titles, pronouns, &c are all ignored because d'Eon did not act how an 18th century Frenchwoman was supposed to act. And this often comes from people who do not consider themselves transphobic (and even some people who are trans themselves). It's well I'd never misgender a modern trans person but we don't know how d'Eon would identify today but we do know how she identified in her lifetime! Why are d'Eon's own words about her own gender dismissed while we hold up the opinions of people like Henriette Campan who seems to be, by d'Eon's own account, a judgmental mean girl who harassed and belittled d'Eon for not preforming femininity to her standards.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Geneviève d’Eon & Marie-Jeanne Bertin: Clothing and Gender in 18th Century France

"After being fully dressed by famous designer Rose Bertin for the first time, they ran to their room and cried for hours." ~ Kaz Rowe, The Chevalier d'Eon: the Trans 18th Century Spy

Kaz Rowe throws this story out there in their video on d'Eon as a part of their justification in using they/them pronouns for d'Eon who used she/her pronouns. Rowe never really explains the context for this story. It sounds dramatic on the surface, d'Eon spent hours crying over being forced into women's clothes. But did this really happen?

This story comes from d'Eon's own autobiographical writings that she never finished. Segments of her drafts were translated and published by Roland A. Champagne, Nina Ekstein, and Gary Kates in The Maiden of Tonnerre. The title comes from d'Eon who styled herself la pucelle de Tonnerre after Joan of Arc who was known as la pucelle d'Orléans.

Some things to consider before we start:

D'Eon's autobiographical writings operate under the pretence that she was afab and raised as a boy for inherence reasons. We have to remember that these writings are heavily fictionalised, a necessity in upholding the lie that allowed d'Eon to live as a woman. However that doesn't mean that there is no historical value in these writings. Instead of simply taking these stories as fact we must consider: Why is d'Eon presenting this story in this way? How does this story serve the narrative d'Eon is constructing for herself?

D'Eon in this story claims she had never worn women's clothing before. This is contradicted by d'Eon's own claim of infiltrating the court of Empress Elizabeth of Russia as a woman. While its hard to pinpoint the exact moment d'Eon first wore women's clothes I personally suspect it was much earlier than this.

D'Eon also includes a scene where she is bathed by Bertin's assistants. This scene is almost certainly fictional as if it happened in reality this would reveal that d'Eon had a penis, a fact she wanted to keep secret. This scene is almost certainly included to add to the 'evidence' that d'Eon was afab.

Considering these points we must consider that this story did not take place literally as d'Eon depicts it. Instead of taking this story as an accurate recollection of events I consider it a fictionalised story (based on true events). The goal in my analysis is to ask what is d'Eon trying to communicate though this story.

Some background information to add context:

D'Eon had prior to this incident signed a transaction with Louis XVI in which she was legally acknowledged as a woman and ordered by Louis XVI to wear woman's clothes. D'Eon agreed to "declaring publicly my sex, to my condition being established beyond a doubt, to resume and wear female attire until death," but then adds "unless, taking into consideration my being so long accustomed to appear in uniform, his Majesty will consent, on sufferance only, to my resuming male attire should it become impossible for me to endure the embarrassment of adopting the other". (see D'Eon de Beaumont, his life and times by Alfred Rieu, p174-182 for an English translation of the transaction)

We also must consider that d'Eon did not dispute the fact that she was a woman when signing the transaction, nor does she dispute this in her autobiographical writings. D'Eon was very much arguing that she, as a woman, should be allowed to continue to wear men's clothing (specifically her dragoon uniform) as that is what she was used to wearing and comfortable wearing.

Also mentioned in the following excerpt is the English trial over d'Eon's sex in which it was found that d'Eon was a woman. I'm not going to get too into the topic here as it's a whole other can of worms. However I think it's important to understand that while d'Eon had issues with aspects of the trial she would use the ruling to support her claim that she was afab.

The Maiden of Tonnerre: Chapter VII

Selections from the great interview between Mademoiselle Bertin and Mademoiselle d'Eon in Paris on October 21, 1777

Mademoiselle Bertin. I have come vary early in the morning to spare you trouble and embarrassment. But what else can I do? You must either go through this or through the gates of a convent.

Mademoiselle d'Eon. It is easy to do otherwise. Just leave me as I am. I have lived for forty-eight years this way. I cannot live all that much longer. I am impatiently awaiting the great change that will transform us all making all of us eternally equal.

Mademoiselle Bertin. The Court in its patience will never have the endurance to wait that long. Remember that it was a deliberate error on the part of your father, your mother, and yourself that resulted in Mademoiselle d'Eon's wearing men's clothing and a military uniform. But since that time things have changed considerably, and today by order of King and the law, the bad boy must become a good girl.

It's interesting that here d'Eon has Bertin distinguish between "men's clothing" and "military uniform". As women were not allowed in the French military at this time all French military uniforms were as such men's clothing. But d'Eon did not simply want to wear men's clothing she wanted to wear her military uniform.

Mademoiselle d'Eon. If I was a boy by mistake, one could inadvertently allow me to continue to be one. While you are correct about the substance of the matter, I am not wrong about the form.

Mademoiselle Bertin. That is not possible now. Your trial created too much of a stir.

Mademoiselle d'Eon. I am a reliable bugler in my squadron. I am not frightened by noise. The Court's behaviour, by its very decency, has wound up being indecent. I would have thought that the King would have been willing to allow me to wear the uniform of a former dragoon captain, Knight of Saint Louis, and plenipotentiary minister, since he was kind enough to allow me to wear the cross of the royal and military order of Saint Louis on my dress. Do you see how everything at court is so arbitrary? There one could say every day: Contraria contrariis opponuntur [A contrary opposes other contraries].

Again we see the focus is that d'Eon wanted to wear her dragoon uniform. She likens this directly to her cross of Saint Louis which Louis XVI did permit her to wear on her women's clothes. As the cross of Saint Louis was only awarded to men it is arguably also menswear. D'Eon is pointing out the arbitrary nature of this distinction. Why is she permitted to wear an idem of menswear, the cross of Saint Louis, but not another, her dragoon uniform. To d'Eon these both represent her achievements rather than manhood, she is arguing that she, a woman, should be allowed to wear them.

Mademoiselle Bertin. I concede that every day we see in the streets of Paris a tall young woman in the uniform of a dragoon publicly giving lessons on the use if arms. But remember that this girl was a mere dragoon and that she had no other way to earn a living. To do so, she had written permission to dress as a dragoon form the lieutenant general of the Paris police. But the Court would never grant such permission for a young woman from a good family who had been in France and in foreign courts as Mademoiselle d'Eon has been.

Mademoiselle d'Eon. In a well-regulated country, the law must not allow preferential treatment to anyone.

Mademoiselle Bertin. You can go to Versailles to argue with the Chancellor of France, your former schoolmate. But with Mademoiselle Bertin, it can serve no purpose to argue. Do not take this matter so far as to have a falling out with the King's ministers or the royal Treasury. Remember, Mademoiselle, that in France a maiden who obeys the law and the King must wear her dress and petticoat, whether to remain in this world or to spend her time in the convent.

Mademoiselle d'Eon. Your advice is wise and prudent. I would rather follow you into the royal Treasury than into a convent.

Mademoiselle Bertin. My honorable captain, don't think that you are dishonored by having been found to be a woman. The discomfiture is temporary, and the glory will be with you forever. But let us not wast uselessly the precious time needed to begin and end your outfitting before the return of Major Varville.

Mademoiselle d'Eon. I see that Mademoiselle Bertin is correct about all that she says and does and that a lady-in-waiting to the Queen is thus wiser in her comportment and in her begetting than all the children of the Enlightenment and all the captains of the army.

Without delaying further and having followed the instructions of Mademoiselle Bertin, the Dragoon was, in a short period of time, divested of his serpent's skin and transformed into an angel of light. Her head became as lustrous as the sun. Her whole outlook on things changed as much as did her face. No trace of the dragoon remained in her.

Mademoiselle Bertin thought she was consoling me by saying: "The Queen doesn't despise bravery in a well-born maiden. But out of duty she prefers to find in her decency, honor, and virtue. If Louis XV armed you as a Knight of French soldiers, Louis XVI arms you as a chevalière of French women. And the Queen crowns your wisdom by commanding me to bring to you this new armor, which must accompany your coiffure and your demeanor so that you may become the leading general of all the honorable women of France. The time has come for us to be edified and not scandalized by Mademoiselle d'Eon's conduct. Why don't you offer up your uniform as a sacrifice at Notre Dame de Paris or in your holy anger throw it out the window in order to stand witness before the people of Israel, the Parisians, the Scribes, and the Pharisees that you are now following the letter of the law that Moses gave us in his commandments."

While Mademoiselle Bertin had me get into the bath to be washed, soaped and scrubbed down by her companions, I told her: "Proceed as quickly as possible; do not waste time with the preparations so that I too may keep part of my own dignity as it is joined with yours and that of your seamstresses. Virtuous Bertin, honest messenger form the chamber of the Queen, I fully realize that the hour is at hand for me to follow the directive of the law and the King. As a victim, I am offered up in sacrifice since you do me harm in order to do me good. All women are going to point at me, and all the maidens are going to thumb their noses at me when they see me dressed in style and done up like a doll or at the very least like a Vestal Virgin who is led to the marriage altar."

We see in this excerpt Bertin acts as an authority ushering d'Eon into womanhood, the transformation is painful but ultimately positive for d'Eon; "you do me harm in order to do me good". But there is this real fear of being mocked by other women. At least part of d'Eon's trepidation to don women's clothes comes form the fear of humiliation. We see this fear also reflected in the transaction when she begs King Louis to "consent, on sufferance only, to my resuming male attire should it become impossible for me to endure the embarrassment of adopting the other".

Mademoiselle Bertin. Put aside your concerns about what other will say. Must what the mad say prevent us from being wise?

Mademoiselle d'Eon. Alas, at court everything is beautiful. To please the court, does a former captain have to become a pretty boy [demoiseau]?

Mademoiselle Bertin. Yes, absolutely, when the so-called "boy" is discovered to be in fact a girl by the systems of justice both in England and in France.

Mademoiselle d'Eon. Speaking of justice, is Mademoiselle Bertin, the Queen's servant, also the enforcer of justice?

Mademoiselle Bertin was stung. "Don't be angry," I told her, "I simply wanted you to acknowledge, for you are just in all matters, that I cannot fit into the dress you brought me."

Mademoiselle Bertin remained disconcerted for a moment. But she soon regained her composure and said to me: "If you are a patient girl, the dress that I made for you in the name of Justice will soon be taken out to fit you. And I predict for you that the certainty of happiness will come form the alleged abyss of your unhappiness."

Then, looking pleased with herself, she said to me: "I am glad about having stripped you of your armor and your dragoon skin in order to arm you from head to toe with your dress and finery. In you I have found the power to possess the benefit of simple tonsure without a papal dispensation. Give thanks to God. You can assuredly double your chances of attaining eternal life, for which all of us search amidst this life's sorrows, troubles and suffering. Tomorrow you will suffer less, and the following day you will not suffer at all. In a little while, you will enjoy the relaxation and the joy that are the natural prerogatives of a Catholic girl who loyally follows the breviary of Rome and Paris, which was annotated, revised, and made available to the Daughters of Holy Mary and the Queen's women. You are not yet canonized, but soon you will be beatified when your upcoming marriage is canonically approved. Better this for you than a cannon shot."

D'Eon at this time was considering joining a convent. Bertin is referring to d'Eon's marriage to Christ.

Mademoiselle d'Eon. You can even say that regarding a hail of cannon shots. ... But when I reflect on my past and present states, I will never have the courage to go out in public dressed as you have me. You have illuminated and brightened me up so much that I dare not look at myself in the mirror that you brought me.

Mademoiselle Bertin. A room is not lit up in order to hide it or to keep it in the dark, but rather it is placed beneath a chandelier so that those who enter can see the light and be edified by your conversion.

Mademoiselle d'Eon. I know that there is nothing hidden that should not be revealed or anything secret that cannot be known. Therefore, I will not seek my own willpower but that of the King who sent you here to Mademoiselle d'Eon to change what is bad into something good. Since he obliges me to choose the best way, it will not be taken away from me. What is worth choosing is worth maintaining. When you came to me, I thought you were bringing me death. Now I go to you in order to be alive, because I am no longer chasing after the false vainglory of the dragoons, but after the solid glory of maidens of pease. I am no longer looking for my own glory. There is another who is seeking it for me and is judging it. This order is the most Christian King following the opinion of his Council and his apostolic Sanhedrin, who grants me glory so that I myself might experience that God's will is perfect, that will of the law is just, the King's will is good, and that of the Queen pleasant, decent, and proper, because the Son of Man came to save what was lost.

After this conversation, I quickly left the room and hurried to my bedroom, where I wept bitterly. Mademoiselle Bertin closely followed me and uselessly proposed both a drink and smelling salts in order to console me. I stopped crying only when my tears naturally dried up. Mademoiselle Bertin, as a crafty member of the Court, took advantage of my weekness by saying: "You are certainly not unaware of the joy experienced by the public in Paris when they heard sung the verses about the Heroine from Tonnerre, which were recently printed and are being sung throughout France."

That was the only thing that calmed me in my distress, for when a heart is not entirely dedicated to God it is partly attached to this world. Only vanity can console such an individual because this world prefers human glory to the divine.

And so that it. Thats the moment that d'Eon "cried for hours" after being dressed by Mademoiselle Bertin. So what is d'Eon trying to communicate to the reader in this excerpt?

"When you came to me, I thought you were bringing me death. Now I go to you in order to be alive" is a key part of d'Eon's speech to Bertin, it mirrors an earlier moment in chapter VI where d'Eon says to Bertin "You have killed my brother the dragoon. That leaves me with a heavy heart." In order for d'Eon to become a woman the man or more precisely the dragoon must be killed. D'Eon tries to hang onto both womanhood and her identity as a dragoon but she isn't allowed to.

She cries in morning for the loss of the dragoon she once was and is only cheered by Bertin reminding her that she is now a Heroine. However the d'Eon who is narrating this story criticises her past self for vanity. We see this thought continued in the next chapter:

There is no doubt that it would have been preferable, for my happiness in this world and my salvation in the one to come, had my investiture taken place forty years earlier, because the dragoon disease is so deeply rooted in me that I greatly fear that our saintly Madame Louise will unite with our holy Archbishop, the good Marquis de l'Hôpital, and his pious spouse to have me put away in a hospital for the incurable.

D'Eon presents her transformation into womanhood at the hands of Mademoiselle Bertin as a painful experience but ultimately a necessary and good one that brought her happiness in the long term. I'll leave off with d'Eon's words:

That was all I could respond to Mademoiselle Bertin's questions, whether they were hers alone or form on high. I answered them in a satisfactory manner according to my system of moderation, so appropriate to my position and to the disposition that heaven has inspired in me, and not that of the dragoon, which I drove out of my clothes and away from the wardrobe that the honorable messenger of the Queen had brought me. Thus I can say without flattery that Mademoiselle Bertin is the best of the women who can be found at the Court, in the city, in Picardy, in France, and in the world. My dear Mademoiselle Bertin, it will soon be midnight return to rejoin your forty Virtues as if it were midday.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philippa Gregory and Lazy Research: the Issue With Pop History as Exemplified by the Misinformation Surrounding Geneviève d'Eon in the Book Normal Women

If you frequent bookstores or libraries you might have seen Philippa Gregory's new book Normal Women in the best sellers or most wanted displays. The fact that Geneviève d'Eon, a trans woman, is included in a woman's history book is marvelous. D'Eon has been denied her place in woman's history for far too long. So what's the problem? Well Philippa Gregory's lazy research is the problem.

For full transparency I have to admit I didn't read the whole book. And honestly based on what I did read I probably wont read it because the short section I did read left a lot to be desired. While the section on d'Eon is short Gregory sure can pack a fair bit of misinformation into 7 paragraphs.

The most glaring error is d'Eon's name. Gregory claims her name was Lia however this is simply not true. D'Eon's full name was Charlotte-Geneviève-Louise-Auguste-André-Timothée d’Eon de Beaumont, or Geneviève d'Eon for short. When d'Eon transitioned she changed her first name to Charlotte, but she actually went by her middle name Geneviève, which was one of her baptismal names. The name Geneviève had both personal and religious significance for d'Eon having been given to her by her godmother. She talks about this in the draft of her autobiography:

I did undertake to make a novena to my patron saint, Geneviève, in the hope of gaining insight, since the name Geneviève was given to me at baptism by my godmother, the sister of my father and of my uncle.

(The Maiden of Tonnerre, p9)

She also mentions her name when writing about the joy of being able to live openly as a woman:

At present I am living in profound peace; and my joy is so great that I praise God in three languages so that a greater number of people may partake of the happiness of the angels in this life while awaiting the crown of ordinary martyrs, Nunc Genofeva d'Eon est nomen meum; quam suave et dulce est laetitia mea! [My name is now Geneviève d’Eon; how delightful and how sweet is my joy!]

(The Maiden of Tonnerre, p87)

[Ticket for Geneviève d'Eon's fencing display at Mrs. Bateman's house in Soho, c. 1793, via The British Museum]

The only evidence that suggests d'Eon may have used the name Lia is from a flirtatious letter written by her then boss the Marquis de l'Hôpital during her mission in Russia. L'Hôpital, who was 30 years her senior, calls d'Eon "ma chère Lia" and "ma belle de Beaumont". In other letters l'Hôpital often complains about d'Eon's lack of sexual activity, often making comments about her penis. It's unclear how d'Eon felt about the name Lia or the multiple sexual remarks made by her boss. (see Mémoires sur la Chevalière d'Éon by Frédéric Gaillardet, p16, 77, 80, 94, 99 & 110 for the l'Hôpital letters)

Gregory isn't just confused about d'Eon's name, she also mixes up details of d'Eon's life claiming that d'Eon dressed as a woman during her mission to spy on England in preparation for an French invasion, stating that d'Eon "moved in London society as Lia de Beaumont." I've never seen any strong evidence that d'Eon was dressing in woman's clothes for this mission and Gregory doesn't provide any evidence of this either. Certainly d'Eon claimed to have dressed in women's clothes during her mission in Russia but not England. (see The Maiden of Tonnerre for d'Eon's claims that she adopted a female alias in Russia)

Gregory also claims:

In August 1777, Lia de Beaumont chose a male identity and wore a grenadier's uniform to volunteer for military service in the American War of Independence, but was prevented from joining the conflict

While d'Eon did attempt to rejoin the French army in 1778 & 1779 she did not "chose a male identity". D'Eon asked to be able to rejoin the army as a woman. In February 1779 d'Eon published an open letter to "several Great Ladies at Court" hoping for support in rejoining the army:

Foreseeing that there will be less fighting on land this year than last, I earnestly entreat you to use your influence with the ministers, in favour of my petition (as stated in the enclosed copy of my letter to the Comte de Maurepas) to serve as a volunteer in the fleet of the Comte d'Orvilliers. Your name, Madame, is one to which military glory is familiar, and, as a woman, you must love the glory of our sex. I have striven to sustain that throughout the late war with Germany, and in negotiating at European courts during the last twenty-five years. There is nothing left for me to do but to fight at sea in the Royal Navy. I hope to acquit myself in such a way that you will not regret having fostered the good intention of one who has the honour to be, with profoundest respect, faithfully yours.

La Chevalière d'Eon.

(Originally published in Correspondance Littéraire, Philosophique et Critique, translation by Alfred Rieu in D'Eon de Beaumont, His Life and Times, p233)

Nowhere in this letter does d'Eon claim to be a man. In fact she writes "as a woman, you must love the glory of our sex" (emphasis mine) and signs it in the feminine "La Chevalière d'Eon."

Gregory also includes the following quote from Madame Campan's book Memoirs Of The Court Of Marie Antoinette:

He was made to resume the costume of that sex to which in France everything is pardoned. The desire to see his native land once more determined him to submit to the condition, but he revenged himself by combining the long train of his gown and the three deep ruffles on his sleeves with the attitude and conversation of a grenadier, which made him very disagreeable company.

I have to ask why Gregory felt this needed to be included? Why is Campan's speculation on d'Eon's gender given more weight than any of d'Eon's own writings on gender? Shouldn't we prioritise what d'Eon said about herself over the speculation of an acquaintance of hers?

Why not include this quote:

I would prefer to keep my male clothes, because they open all the doors to fortune, glory, and courage. Dresses close all those doors for me. Dresses only give me room to cry about the misery and servitude of women, and you know that I am crazy about liberty. But nature has come to oppose me, and to make me feel the need for women’s clothes, so that I can sleep, eat, and study in peace. I am constantly in fear of some sickness or accident that will, despite myself, allow my sex to be discovered …. Nature makes a good friend but a bad enemy. If you chase it through the door, it just blows back in through the window.

(Monsieur D'Eon Is a Woman by Gary Kates p71)

Or this one:

If certain modern philosophers do not approve of my conversion, it is because they do not believe in God, the law, or the King. God forgave me, the living law vindicated me, and the legal systems in England and France awarded me full rights to wear a dress. Louis XV and Louis XVI were my patrons, the Queen who is the daughter of the Caesars had me dressed in her court by Mademoiselle Bertin; the very woman who dresses the Queen did not turn up her nose at dressing Mademoiselle d'Eon grandly.

(The Maiden of Tonnerre, p134)

Or maybe this one:

Having been a decent man, a zealous citizen and a brave soldier all my life, I triumph in being a woman and in being able to be cited for ever amongst those many woman who have proved that the qualities and virtues of which men are so proud have not been denied to those of my sex.

(La Vie militaire, politique et privée de Melle d’Eon (1779): Biography and the Art of Manipulation by Anne-Marie Mercier-Faivre)

Gregory isn't alone in the choice to highlight Campan's speculation over d'Eon's own words, Wikipedia also does this, which makes me wonder if she originally got this quote from d'Eon's Wikipedia page. Perhaps Gregory doesn't know what d'Eon wrote about gender because she hasn't read anything d'Eon wrote about gender.

It's clear that Philippa Gregory's research on d'Eon was frankly lazy and nothing exemplifies this as much as her thinking d'Eon's name was Lia. But why does Philippa Gregory think d'Eon's name is Lia when primary source evidence clearly shows otherwise? Well it's certainly a common myth that d'Eon used the name Lia de Beaumont as a alias while working as a spy in Russia. The assumption was originally made by Frédéric Gaillardet in his largely fictitious book Memoires du Chevalier d'Eon. Gaillardet assumes that d'Eon used the name Lia de Beaumont because of the letter from the Marquis de l'Hôpital in which he calls her "ma chère Lia" and "ma belle de Beaumont". Whether or not d'Eon even did have a female alias while working as a spy in Russia is a controversial point amongst historians. However even if we assume she did use the name Lia as an alias its still not really her name.

I don't think I've seen a single historian claim d'Eon's name was actually Lia but I have seen many people on social media claim this was her name. The logic seems to be that if d'Eon used Lia de Beaumont as an alias that it was probably her preferred name. With most secondary sources on d'Eon using her deadname and never identifying d'Eon by either her first name Charlotte or preferred name Geneviève the issue gets confused. Lia seems like the preferable choice of name to people who don't want to deadname d'Eon but also aren't aware of any other feminine name she went by.

But why does Philippa Gregory think d'Eon's name is Lia? Surely Gregory isn't getting her information from social media? Right? But none of her cited sources identify Lia as d'Eon's name. In fact one of her cited sources, D'Eon Returns to France: Gender and Power in 1777 by Gary Kates, is one of the few secondary sources that does mention that d'Eon's name was Charlotte. Is Gregory even reading her own sources?

This issue isn't unique to Philippa Gregory it's a common issue in pop history. If you want to cover a broad topic that will appeal to a wide audience, like 900 years of women's history, you almost certainly are not going to study every aspect in significant detail. Can we really expect Philippa Gregory to do in-depth research into one individual she only talks about for 7 paragraphs? Of course not. So the research gets lazy.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

thats not what that says

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dumbest d'Eon theory is that Louis XVI forced her to live as a woman (for god knows what reason) and that she got back at him by acting like a man anyway. Because we all know that all women speak softly, are always polite, love fashion and makeup and don't do gross mannish things like drink, swear or have an attitude 🙄

#some dumbass: d'Eon wore a dress but had an attitude does this sound like a trans woman to you#like yes???#chevalière d'eon

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

the whole d’Eon was trying to signal to everyone that’s she was actually a man being forced to live as a woman theory really breaks down when you remember that gender nonconformity exists and that women can get out of carriages on their own or whatever

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

do we really think that Geneviève 'the pronoun on is stupid' d'Eon would be super stoked about people using they/them pronouns for her

#tbh I think this comment is in part d'Eon overcompensating#however#and this is pure speculation#I wonder if people would use 'on' for her instead of feminine pronouns which could explain the dislike#I could be completely wrong tho and I'm the wrong person to talk about this because I don't speak french#queer french speakers your insight is welcome#chevalière d'eon

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

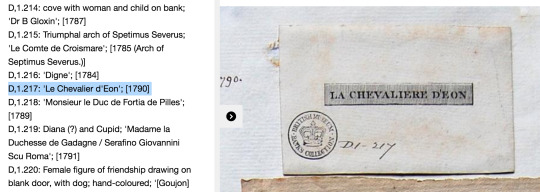

*Museum voice* in order to be respectful we have chosen to use they/them pronouns for d'Eon even though d'Eon used she/her pronouns (just be happy we aren't using he/him pronouns anymore). We also will continue to use "Chevalier" rather than "Chevalière" in complete disregard to her preference. Oh and we're going to dead name her. #transrights

72 notes

·

View notes