#colonel thomas lawrence

Text

Poedit Cut/Unused Content: The Salty Dog, A Dead Man's Best Friend, and Old Soldiers

I am playing through We Happy Few again for monstroso and a thought occurs to me.

Another point in the direction of the Salty Dog being Something: when Sally visits Colonel Lawrence, he calls out for his third daughter, Hope. The Salty Dog contains the Hope Diamond. Colonel Lawrence's house contains the Salty Dog in Ollie's act.

Sooo off to Poedit I went to see what there was to see.

In "The Salty Dog", there's a missing cutscene where Sally meets the Ploughboys in their alley and, interestingly, the person speaking opposite her is appended with WellF, indicating this was a female Wellie role.

026 Sally Bloody Boyle. We've got no quarrel with you. Well, to be fair, we've got a quarrel with you, but it's not urgent.

028 You stole Cap'n Strawbeard's little buddy.

030 This ugly dead dog! Hah! He robbed it from Colonel Lawrence's house!

032 Yes, well, I'm taking it back to him. The Captain, I mean.

034 Do you have any idea how valuable this stupid dead dog is? No thank you, let's fight.

036 How valuable is it?

038 Not the faintest fucking clue, except someone wants it very badly.

040 What's so valuable about a dead dog? Maybe I should see if it's got something in it.

042 Nothing. Ugh. I can't believe I opened this thing up.

046 Well, in Wellington Wells, Everything already sparkles.

Mild intrigue at that at a point the dog was supposed to have already been opened before Sally got to it. A female Ploughboy though? Could also just be in the same sort of way as the Wastrellette in "Jericho" where she's merely an accomplice, but that she's apparently in charge of this endeavor? Hmmity hmm hmm hmm.

I await your Ploughgirl OC's.

Moving on, I also checked "A Dead Man's Best Friend" because that also involves the Salty Dog.

110 I think that's the stuffed dog! Do dogs really sit like that? I can't remember.

112 Och, Colonel, ye have come a very long way from the honours o' Ramsgate, have ye not?

114 Ye dinna deserve bairns such as these.

116 As one soldier to another, I'll bury ye myself if that's what it takes.

118 Why do you think he's so anxious to get this ridiculous dog?

120 I dinna ken. D'ye think there's something inside of it?

XXX What's in it? What's in it?

124 Anywhere but here, any time but this, it would be a king's ransom. Here, it's a bloody great rock.

126 The stuffing that dreams are made of.

128 Magnificent. Won't he be pleased. Oh, this is an ugly thing, is it not.

130 What's in it?

132 Nothing! Nothing at all. Well, even if there was something in it. My client is a man you want in your corner. And not in the other.

134 Ohhhh... that is a shame. It's been opened already. My client won't be interested in this any more. Well. It was a bit much to expect that neither the Plough Boys nor the Captain would have ... well never mind about that.

I already knew that in a previous build of the game, you had the option of burying Col. Lawrence so that line wasn't a surprise. It seems Ollie also had the option of ripping open the Salty Dog and finding the Hope Diamond himself. Lionel Castershire's line at the end would imply that Strawbeard stole the Salty Dog from Col. Lawrence and the Ploughboys stole it from him.

Lastly, I checked "Old Soldiers" to see if there was anything further. I didn't find anything in relation to the Salty Dog, but there was tons of cut dialogue.

001 DID YOU CHANGE THE DOOR CODES?

002 NO.

003 NEVER MIND. YOU PROBABLY DON'T KNOW HOW.

004 ARE YOU GETTING HIM HIS PORRIDGE?

005 NO I'M TURNING THE ALARM SYSTEM BACK ON WHICH SOMEONE LEFT OFF. YOU WANT SOME DOWNER TO WALK IN AND TAKE ALL OUR RESERVES?

006 WHY DON'T YOU TELL THE WHOLE BLOODY NEIGHBORHOOD WE'VE GOT RESERVES?

007 Oh, yes, you must tell me all about your wonderful reserves.

008 DON'T WORRY, I TURNED THE ALARM BACK ON.

009 WERE YOU EXPECTING A GUEST?

010 YOU'VE GOT THAT TONE IN YOUR VOICE AGAIN. WHY DON'T YOU POP A JOY.

011 OR DID YOU ALREADY HAVE YOUR GUEST?

012 WHILE YOU'RE UP THERE, WHY DON'T YOU GET HIM HIS PORRIDGE.

Tail end of this conversation was cut off.

013 It's your turn, you know.

014 He's your dad.

015 That's hardly my fault, is it?

016 I made the porridge. The least you can do is bring it up to him.

017 It wasn't my idea for him to live with us.

018 As I recall, you wanted him to move out.

019 It was the decent thing for him to do. Make way for the new generation.

021 It's his house.

022 He doesn't need a whole house. He barely even gets up from his chair. All he needs is a bed, a bathroom, and someone to bring him porridge. And clean him.

023 This again! If we'd paid for some stranger to do all that—

024 —he'd've paid for it—

025 —it's money we'd never see again. Look, it won't be long now. But in the mean time...

026 And about that. Are you sure that was the cheapest coffin?

026a They don't offer them "used."

026b They should. They're no use to the "resident."

027 ... the porridge?

028 In a bit. I'll take it up in a bit.

028a I better see if he's all right.

As was this one. That last line, 028a, is Arthur's. And it continues...

029 ... It's just that I hate the way he stares at me.

030 He's blind!

031 So why does he have to stare at me at all, then?

032 What lovely people. Remind me never to have kids. Well, it's not terribly likely, anyway, is it?

032a I dunno, he seems alive to me, or who's ringing his bell? 032b Might have been a bit premature, planning a wake.

032c They live here! They're supposed to look after him!

032d I wish he'd stop that. Now I'm getting hungry.

032e That's not his change-me ring, is it? Sounds more like his hungry ring.

032f I wish they'd take that stupid bell away.

Most interesting though is that apparently the apprentice undertaker and his superior were supposed to be present in the house for this quest. As is, there's merely directions left on the dining room table for the apprentice.

063 Awfully forward-thinking.

064 Planning the sendoff in advance?

065 Usually we're in such a rush.

066 Used to be you could hire a priest to say a mass for someone who hadn't already ... passed. It was supposed to ... encourage them to go to a better place.

067 You don't think they'd ... directly encourage him to take his holiday early?

068 You laugh, but I've had clients I've had suspicions about.

069 At the pub they seem to have suspicions about us.

070 We're not fookin' tour guides. We don't actually take the client on his holiday. We only make the arrangements. We're travel agents, like.

071 No, it's, uh, supposedly Reg the butcher is looking for new sources of meat.

072 Oh, for fuck's sake, you cannot be serious!

073 Supposedly he pays well.

074 If you think you're being funny, you're bloody well not.

075 Not much meat on this one's bones, I guess.

076 Will you shut the fuck up?

This is also actually kind of funny because I made a short twine game a couple years back that was inspired by "The Slaughterer's Apprentice" so it's quite amusing to see the undertakers were originally supposed to have a role in that part of the lore too.

Anyway, last but by no means least! Captain Edward Lawrence was supposed to still be alive when Arthur arrives at his house and he would shout at Arthur on the assumption that he was an enforcer for whoever he owed money to.

000a Go hang yourself!

000b You go tell him I'm not scared of him one bit!

000c I'm not paying him another penny!

000d Hah! You can't get in, can you?

000e Get lost, or I'll call the authorities!

001 "And what did you do in the War?"

002 Not an easy man to see.

003 HULLO? HULLO? CAPTAIN LAWRENCE? I'VE GOT A MESSAGE FOR YOU, SIR. CAPTAIN LAWRENCE SIR?

004 They're going to shut down his power.

006 The power's out. Which means the house is basically unsecured.

007 That's not a good sign.

008 The thanks of a grateful nation.

009 Blimey.

011 A dog? They were fighting over a dog?

In conclusion, what I could do is a story in which Col. Lawrence heard or assumed his brother had Bonny Prince Charlie stuffed and paid someone to steal him, but he received the Salty Dog instead, which is clearly the wrong dog as its a French bulldog, not a Cocker Spaniel. Could play with the idea of this dog being a great personal treasure, what with them having no idea that Salty Dog was hiding the diamond but Charlie being sentimental to both of them.

#we happy few#cut/unused content#sally boyle#ploughboys#cap'n strawbeard#colonel thomas lawrence#captain edward lawrence#ollie starkey#margaret worthing#lionel castershire#arthur hastings#poedit

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

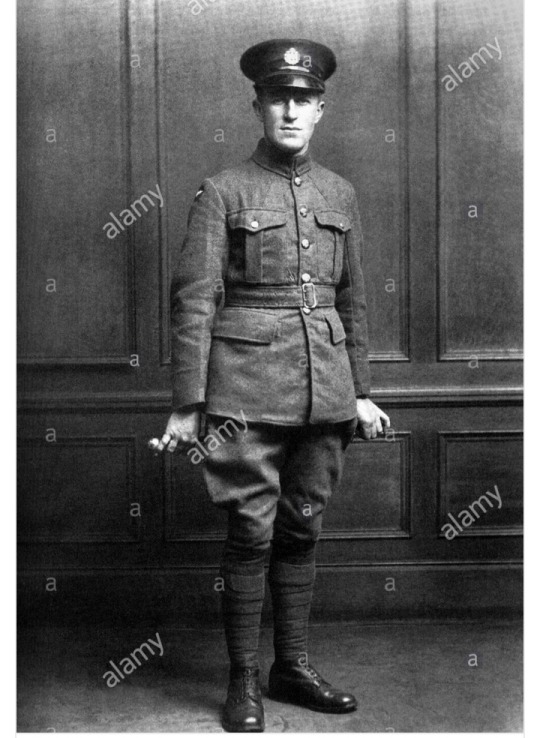

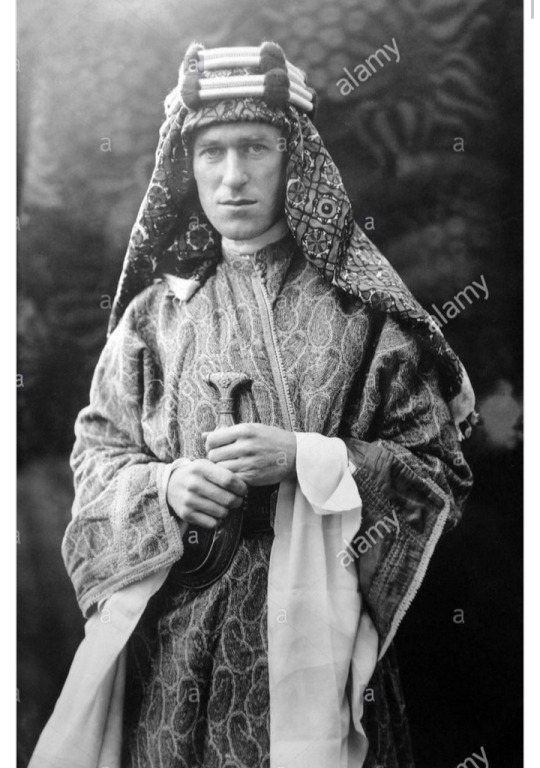

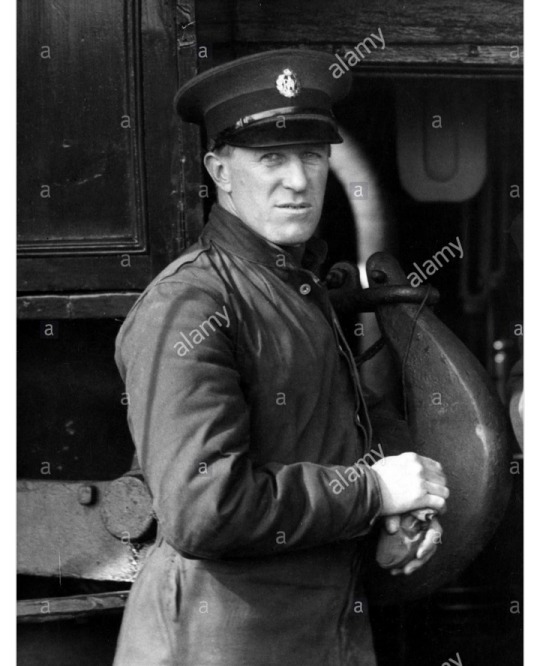

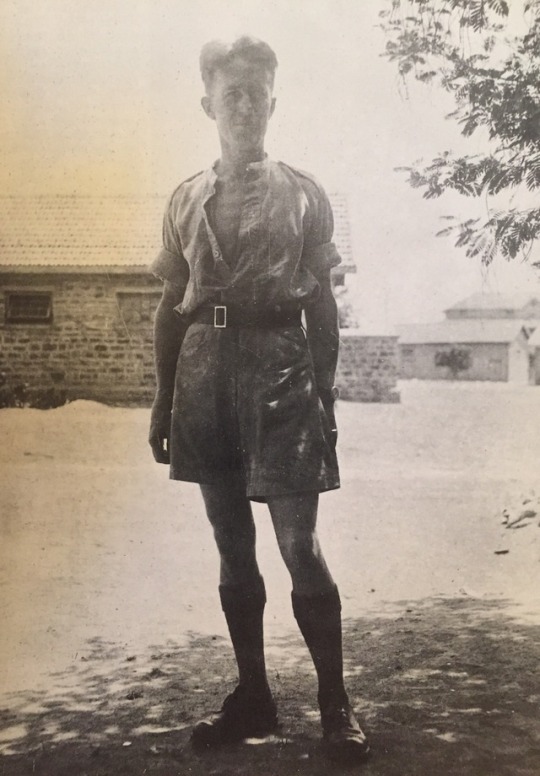

Thomas Edward Lawrence and Peter O'Toole

Left: Lieutenant Colonel T. E. Lawrence in Cairo, 1918.

Right: According to costume designer Dalton, O'Toole's Jerusalem uniform is typical of all his intentionally ill-fitting British officer's garb throughout the film.

***

Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

directed by David Lean

Peter O'Toole

as T. E. Lawrence

#peter o'toole#thomas edward lawrence#lawrence of arabia#on the set of lawrence of arabia#on the set of#costume reference#1918#cairo#egypt#my collection

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caroline Mary Luard

February 29, 2024

Caroline Mary Luard was born in 1850. On July 1, 1875 she married a man named Charles Edward Luard. On August 24, 1908, around 2:30 pm, Caroline and her husband left home and took their dog for a walk.

According to Charles, he wanted to go get his golf clubs from the clubhouse at Godden Green Golf Club, but his wife wanted to go get some exercise before returning home as she was expecting a Mrs. Stewart for afternoon tea.

At 3 pm, the pair separated, at a wicket gate by St. Lawrence's Church. The gate led down a path to a house called "La Casa" owned by neighbours of Caroline and Charles. It was considered a summer house. Past that, through the woods, would get Caroline home.

Charles was seen many times between 3-4 pm. At 3:20 pm, Charles was seen by Thomas Durrand at Hall Farm. Between 3:25-3:30 pm, he was seen by a labourer, around the golf links, and again seen by the same man about 5-10 minutes later. At 3:35 pm, he was seen by the Golf Club Steward on the links.

At 4:05 p, Charles met Rev. A. B. Cotton. Charles was carrying his golf clubs and the Reverend offered to take the clubs in his car. Around 4:25 pm, Charles was dropped off at Ightham Knoll.

When Charles got home, Mrs. Stewart was at the house waiting for Caroline. Charles, knowing Caroline should've made it home by now went to search for his wife. He found her at 5:15 pm, on the verandah of the summer home. The home was locked and empty. Caroline had been shot in the head, and 3 of her rings and purse were missing. The only thing found at the scene were some "disappearing footprints."

The estimated time of the murder was around 3:15 pm, when Charles would have been walking towards the golf clubhouse. Three shots were heard by two witnesses at that time. Annie Wickham and Daniel Kettel, both heard them.

Wickham said she heard the shots come from the direction of the summer house, she was only about 500 yards away from the location.

The inquest was held on August 26, 1908. Caroline had been initially hit on the head, which knocked her to the ground, and she vomited. Her killer shot her behind the right ear, with the second shot into her left cheek.

Charles did claim to have owned 3 guns, but he was unable to remember where he kept the ammunition for them. It was concluded that the bullets came from a .320 revolver, which was fired a few inches from Caroline's head at close range. A gun expert claimed none of Charles' guns would have been able to fire those bullets, since they were smaller.

One of Caroline's pockets had been ripped off her dress, and police were hoping that would lead them to her killer. The pocket was found by a maid on the day before the funeral, at Ightham Knoll. The maid had been shaking out the sheet in which Caroline's body had been carried back to the house. Caroline's 3 rings were never seen again, despite police hoping someone would pawn them.

Many people believed Charles had murdered his wife, and Charles received anonymous letters accusing him of such. Charles decided to leave the area, and was staying with Colonel Charles Edward Warde.

On September 18, Charles wrote a letter to his son, who was supposedly on his way back from South Africa, after learning his mother had died, as well as a letter to Colonel Warde. He then walked the railway line at Teston, hid in bushes, and then jumped in front of the train.

He pinned a note to his coat that read, "Whoever finds me take me to Colonel Warde."

Caroline's murder police believed was committed by someone she knew, and that it had been planned. They did not think the real motive was robbery. Charles death was ruled a suicide due to him being "temporarily insane."

Some people think John Dickman was Caroline's killer, in 1910 he was sentenced to death for murdering a man on a train.

#true crime#crime#unsolved mysteries#unsolved#murder#homicide#unsolved murder#unsolved case#solved#mystery

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who's Who of Seven Pillars of Wisdom and the Arab Revolt

TE Lawrence - British archaeologist, later spy, soldier, and diplomat. Lawrence was the illegitimate son of an Anglo-Irish lord and a governess in his household. Lawrence completed a 1,000 mile walking tour of crusade castles in Syria for his Oxford history thesis and later did field work under the famous archaeologist David Hogarth. His fluency in Arabic, as well as knowledge of local history, customs, and geography, suited him to assignment to advise the Arab Revolt.

Lawrence argued vehemently for Britain and France to uphold their promise of a united, self-ruling, pan-Arabic state after the war, and against the Sykes-Picot Agreement that divided the region into European mandate states. How much Lawrence knew of the planned betrayal of the Arab allies during the Revolt is open to debate, but he continued to advocate for Arab voices and self-rule. At the Paris Peace Conference, Lawrence made a point to dress in Arab clothing, associate primarily with the Arab delegation, and demonstrate his support.

After the war, Lawrence suffered mentally and emotionally. In addition to the general horrors of war, he had possibly been captured, tortured, and sexually assaulted. (Historicity of this is debated.) His personal guarantees had been broken by his government.

He re-enlisted in the Royal Air Force as an aircraftman (the lowest rank), after having retired from the army as a colonel (a high ranking officer), under a fake name - John Hume Ross. When his true identity was discovered, he left, despite an offer to allow him to remain. He changed his name more officially to TE Shaw (from his friendship with playwright George Bernard Shaw), and enlisted in the Royal Tank Corps, again as a private, the lowest rank. Unhappy, he returned to the RAF again, under the name Shaw and fully above-board, where he remained for five years.

Lawrence finally left the RAF in 1935 and died in a motorcycle accident about two months later, swerving to avoid some bicyclists.

5'5" (166 cm) tall and wiry. Tiny!

Spoke Arabic, French, Greek, and Latin. Published his own translation of The Odyssey, his dissertation study of crusader castles, several memoirs, and many poems. Lots of poems.

Carried a copy of Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur in his pocket everywhere during the war.

Likely homoromantic asexual. Did not like being touched by anyone. Showed no sexual or romantic desire toward women, but strong admiration for male bodies and intimacy. This is all further complicated by the possible sexual assault, his possible kinkiness, and the post-war whippings that he paid an army buddy to regularly administer. (Don't worry, we'll get into all this eventually.)

Really loved motorcycles and bicycles.

A real wells-for-boys kind of guy.

Sherif Hussein bin Ali al-Hashimi - Sherif and Emir of Mecca, 37th generation direct descendent of Mohammed, credited with officially forming and declaring the Arab Revolt, later King of Hejaz (western Arabian Peninsula). His communication with Henry McMahon (below), the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence, established the alliance between Britain and the Revolt. Sherif Ali attempted to establish a pan-Arabic state after the war. His three sons led the efforts of the revolt and the diplomatic endeavors. His descendants, the Hashemite family, rule Jordan to this day.

Prince Faisal (Feisal) bin Hussein- A guy to watch! Our man! Third son of Sherif Hussein, head of the main northern force of the Revolt, and later king of Syria and Iraq. Became a friend of Lawrence's and requested his permanent assignment with the Revolt. Critics of Lawrence say that some actions and ideas Lawrence took credit for may have been Faisal's instead. Leader of the Arab delegation to the Paris Peace Conference.

(Mod Whit note: A biography of Faisal recently came out by Ali Allawi, Iraq's current Deputy Prime Minister. Very excited to read and include points here!)

Prince Ali bin Hussein - First son of Sherif Hussein. Later King of Hejaz after his father.

Prince Abdullah bin Hussein - Second son of Sherif Hussein. Later King of Transjordan. Commanded the next-largest, eastern portion of the Arab army.

Prince Zeid bin Hussein - Fourth son of Sherif Hussein. Led the forces that cut off Ottoman reinforcements from Medina to Rabigh. Later, served in the government under his brother Faisal's rule in Iraq, until the overthrow of the royal family.

Henry McMahon - British High Commissioner in Egypt when the Arab Revolt started. His initial promise lie to Sherif Hussein of supporting an Arab state led to the cooperation.

SF Newcombe - The British officer originally assigned to be liaison with the Revolt. He was late arriving and Lawrence was sent to fill in. When Newcombe finally arrived, Faisal had become close to Lawrence and asked for Lawrence to remain in his position. Newcombe remained involved and a friend of Lawrence's for life.

Lord Kitchener - British High Commander during World War I. Famous for the 'stache. A full-on war criminal of the lowest order. Put Boer civilians in concentration camps during the Second Boer War in Africa years earlier, among other atrocities.

Mark Sykes - Co-authored the Sykes-Picot Agreement, a semi-secret arrangement between Britain and France to divide up the Middle East into colonial mandate states after the war. Lawrence thinks he's an ass-hat and takes the opportunity to call him incompetent and bad. (Very hard to overstate how bad this was. This agreement is a factor in virtually all of the conflicts and difficulties in the Middle East for the next 100 years and counting.)

Sherif Abd el Kerim - Lawrence's assigned guide for an early portion of his assignment.

Sherif Sharraf bin Rajeh - Emir of Taif, early Arab fighter against the Ottomans, commander under Faisal.

General Fakhri Pashi (Pasha) - Ottoman commander of the forces in Medina.

Colonel Bremond - Chief of the French Military Mission in Arabia.

Sheikh Auda Abu Tayi - Close companion of Lawrence's throughout the campaign, one of the main leaders of the Battle of Aqaba.

Auda ibn Zaal - Abu Tayi's cousin. A formidable fighter and raider in the Revolt.

Prince Sherif Jamil bin Nasir - Nephew of Sherif Hussein and another close companion of Lawrence's.

Emir Nuri Shaalan - Emir of the Ruwalla tribe of the Beduins. Lawrence calls him the fourth most import leader of peoples in the desert.

(FYI, Lawrence's name spellings are often his transliteration from Arabic, not the agreed English spelling. I will probably bounce back and forth, sorry. This post to be updated, added to, and reblogged as the book progresses. Subscribe here to follow along on the substack!)

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books Read 2022

The Kitchen God’s Wife, Amy Tan

The Antiquarian, Sir Walter Scott

Loving, Henry Green

The Cossacks, Leo Tolstoy

Acte, Alexandre Dumas

Jacob’s Room, Virginia Woolf

The Old Devils, Kingsley Amis

Fear, Gabriel Chevallier

Flappers and Philosophers, F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Encantadas, Herman Melville

The Eternal Husband, Fyodor Dostoevsky

The Marriage Contract, Honore de Balzac

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Philip K. Dick

Therese Raquin, Emile Zola

Far from the Madding Crowd, Thomas Hardy

The House of the Dead, Fyodor Dostoevsky

Clear Light of Day, Anita Desai

Benito Cereno, Herman Melville

The Assistant, Bernard Malamud

The Charterhouse of Parma, Stendhal

The Voyage Out, Virginia Woolf

Commission in Lunacy, Honore de Balzac

Family Happiness, Leo Tolstoy

Youth, Leo Tolstoy

Les Miserables, Victor Hugo

Taras Bulba, Nicolai Gogol

Sons, Pearl S. Buck

The Atheist’s Mass, Honore de Balzac

Boyhood, Leo Tolstoy

Colonel Chabert, Honore de Balzac

The Insulted and Humiliated, Fyodor Dostoevsky

The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Grass is Singing, Doris Lessing

The Purse, Honore de Balzac

The Counterlife, Philip Roth

The Emperor’s Candlesticks, Baroness Orczy

A Rogue’s Life, Wilkie Collins

A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Dickens

Mosquitoes, William Faulkner

Childhood, Leo Tolstoy

The Mysteries of Marseille, Emile Zola

The Lost Girl, DH Lawrence

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Ken Kesey

Prospero’s Cell, Lawrence Durrell

Fathers and Sons, Ivan Turgenev

As I Lay Dying, William Faulkner

Waiting for the Barbarians, JM Coetzee

The Grass Harp, Truman Capote

Father Goriot, Honore de Balzac

This Side of Paradise, F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Sun Also Rises, Ernest Hemingway

The Corsican Brothers, Alexandre Dumas

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

©source: Marina Maral

Colonel Thomas Edward Lawrence, also known as Lawrence of Arabia

Known as Lawrence of Arabia, Colonel Thomas Edward Lawrence became a hero during World War I after spearheading a series of raids in the Middle East. Lawrence is said to have destroyed at least 79 bridges belonging to the Ottoman Empire. He was so adept at destruction that he knew how to leave the structures "scientifically shattered" so they could stand but be unusable.

As strange and impossible as it sounds that an English soldier could so endear himself to soldiers that he knew nothing about, it's all true. His life played out like a film which is likely why Lawrence of Arabia continues to work so well. He was one person who changed the tide of history, something that we all have the ability to do.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In light of the recent interview with George Lucas regarding Star Wars as a metaphor for the Vietnam war, I feel like using something similar at the end of The Book of Boba Fett could have helped with the mess that was episode six, leading up to a rushed finale ... and not just as a visual aid for Episode 2 as stated in the Disney Gallery Special ...

Namely by combining the story of Tatooines struggles with the history of Lawrence of Arabia.

Quick overview:

Colonel Thomas Edward Lawrence was a British soldier sent to Arabia to gain favor and assistance from the local people in order to defeat the Ottoman Empire in exchange for their independence. Only to find out that Britain and France changed the terms in order to split the land between them.

What would that mean for a BOBF narrative?

Well, you have the locals with the Tusken and the settlers, you have the Hutts and the Pykes as those making a grab at the planet/land and of course Boba in the middle of it all. And the spice trade as the thing to be defeated.

The intrigues and betrayals, the cooperation and friendship, it all would fit quite nicely into the world that has been build within the first four episodes. Combine that with actually using the established plot points (e.g. the dreams as warning regarding the Pykes so that Boba comes to the correct conclusion himself instead of it being spelled out in a throw-away line), give it some more air to breath by pushing the finale into The Mandalorian 3x02 (3x01 using the Jedi-parts from episode 6).

That way Boba truly would have been Lawrence and it would have made for one hell of a season ... alas ...

#The Book of Boba Fett#TBOF#book of boba fett#the mandalorian#star wars#boba fett#lawrence of arabia#analysis

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lawrence of Arabia. The man, the myth and the facts

Few British soldiers have a greater legend attached to them than Colonel TE Lawrence - better known as Lawrence of Arabia. His military and diplomatic efforts have drawn some distinction.

But it is Lawrence’s immense cultural impact in the century since his First World War exploits that has attracted the most attention.

Thomas Edward Lawrence was born in Tremadog, Wales on 16th August 1888. From a young age he exhibited an active interest in architecture, monuments and antiquities.

Between 1907 and 1910, Lawrence studied History at Jesus College, Oxford. During this time, he toured France by bicycle, collecting photographs, drawings and measurements of medieval castles.

This would form the basis of his dissertation. In 1909, he completed a remarkable solo 1,000-mile trek through Ottoman Syria visiting Crusader castles.

Following his studies, Lawrence became an archaeologist. He worked in Egypt, Palestine and Syria, at that time all part of the Ottoman Empire.

This first-hand knowledge and experience earned him a posting to Cairo after he enlisted in the British Army in October 1914. He served in the intelligence staff of the British Middle East Command in the First World War campaign against the Turks.

Seven Pillars of Wisdom is a biographical account of T.E. Lawrence's experiences during the Arab Revolt of 1916–18, when he was based in Wadi Rum (now a part of Jordan) as a member of the British Forces.

With the support of Emir Faisal and his tribesmen, he helped organize and carry out attacks on the Ottoman forces from Aqaba in the south to Damascus in the north. You can also listen to Seven Pillars of Wisdom on Audible.

#manchester#iraq#iraqi#london#uk#baghdad#liverpool#scotland#hussein al-alak#usa#lawrence of arabia#t e lawrence#syria#palestine#british army#british history#ww1 history#ww1#military history#world war one

1 note

·

View note

Text

The story of Ireland's other famines

This cartoon, appearing April 18, 1846, was drawn by John Leech. It depicts the Irish peasantry as children and Sir Robert Peel as the old woman who lived in a shoe, with so many children, she didn’t know what to do. Under the title is written, “She gave them some Broth without any Bread, Then whipp’d them all Round, and sent them to Bed.” She is thrashing them with the recently enacted Coercion Bill.

Building off what was written about in yesterday's post, I noted that "considering the famines in 1830-1834, 1836, and 1839," this may have been a factor in Margaret Bibby, John Mills, and may I add Thomas Mills, in coming over the U.S. when they did. I also noted that "famine was nothing new to Ireland, mentioning the famines in 1740–41, 1756–7, 1800, 1807, 1821–2, 1830–34, 1836, and 1839, but providing no further detail. This post aims to provide that detail.

The Irish Potato Famine of 1845 to 1852, at most, connects to a deeper history of Ireland. [1] Due to a harsh military policy begun in 1579, in 1582 and 1583 there was a Munster which killed people by the tens of thousands. This was not an isolated incident, as another occurred in Ulster from 1602 to 1603. Many years later, in 1651 and 1652, an even harsher famine "swept away whole counties" as Colonel Richard Lawrence reported in 1653, killing possibly 200,000 people! This was again, a result of war, with this famine killing up to 20-25% of the population, sometimes called "Cromwell's Famine." In the 1720s, famines again wrecked the continent of Ireland. In 1726, a famine led to the "first large scale Irish migration to Newfoundland." In 1727, famine again struck, with devastation continuing until 1730, leading to widespread devastation, with thousands killed, with the potato, some say, making little difference, as harvest failures in oats went on. Later on, in the 18th century, was an even more severe famine, lasting from late 1739 into 1740 and 1741, which some say was caused by a cold winter and a frost. It killed hundreds of thousands of people, which some say was worse than the famed Irish Potato famine, leading 1741 to be called the "Year of Slaughter" (Bliain an Áirin Irish) as it was accompanied by dysentery and fever! This would foreshadow later famines as the population was becoming even more dependent on potatoes.

This post was originally published on WordPress in July 2018.

As the 18th century went on, there would be further famines. [2] Some recorded famines in 1756-1757 in County Kildare of Ireland, or in 1766 when there was food rioting. However, it is undeniably clear that there were famines later on in the 18th century, as the years between 1782 and 1784, 1795-1796, 1799-1801, there were hardships, but they were short-lived and localised. As one undergraduate honors thesis on Irish famine by a student of the College of William and Mary pointed out:

What we remember as the Great Famine was by no means the first Irish experience with endemic hunger: “crop failures had occurred periodically in Ireland in 1740, 1766, 1782-4, 1795-6, 1800-1, 1816-17 and 1822” (Kinealy 32). Hunger was so common in Ireland that when “Bishop Doyle was asked, in 1832, what was the condition of the population in the west of Ireland, he replied ‘that which it has always been – they are famishing as usual’” (Van de Kamp 2). The Great Famine, however, was unprecedented in both its scope and duration.

David Wootton writes that in the Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith declared that "in a free market economy famines will never occur" and famines that happen are "the result of misconceived government interventions to prevent famine," claiming that "grain harvests never completely fail" but that "famines occur when governments artificially lower prices and thus cause supplies to run out." This actually relates directly to Ireland, as his policies led to issues in years to come:

Smith was quite right to think that England, where there was a relatively free market in grain, had not seen anything resembling a famine in his lifetime. But he completely failed to consider Ireland, where severe famines happened frequently. Worst of all was the famine of 1740-42, which killed 10% of the population, or 300,000 people. Smith had every reason to be familiar with Irish famine, for Jonathan Swift was one of his favourite authors and he had surely read Swift’s Modest Proposal...suggesting that the Irish poor should breed children as livestock, to be consumed by the wealthy. Swift’s solution to the problem of starvation in Ireland was (in appearance) a perfect example of free market economics in practice...Why did the Irish starve? For reasons that would have been familiar to Sen: because neither the government nor landlords intervened effectively to prevent the famine taking hold. In England, on the other hand, there were elaborate interventions, not only to feed the feeble and the unemployed, but also to subsidise bread for the poor and to distribute it free..Smith was also fundamentally wrong: the working poor could not afford to feed themselves in bad years, and were dependent on charity to survive. Why was Smith unwilling to acknowledge the role of charity in preventing famine? I am afraid the answer has to be that his commitment to free market arguments was so dogmatic that he was unwilling to look with an impartial eye at the evidence. Smith was wrong, and his mistake had extremely serious consequences as it influenced policy towards famine through the nineteenth century.

This brings us to how Lyman A. Baker describes Ireland in the 18th century. She writes that it was a place wrought by religious division as "the overwhelming majority of the population was Roman Catholic, but the immigrant Protestant minorities had united with the English to force through Parliament a series of discriminatory inheritance laws which effectively broke up large Catholic estates and put them at the mercy of rapidly consolidating Protestant landowners," leading Catholics to loose their land rights. She adds that the Irish Parliament was impotent, with anger at English efforts to destroy the Irish economy for the benefit of those in England.

In the 18th century, famine spread across Ireland once more. [3] In 1807, there was famine, concentrated in Galaway, Ireland. From 1816 to 1817, there was famine across Ireland, first started by a late growing season and excessive rain which killed the tens of thousands, accompanied by a typhus epidemic. Famine struck again in 1821 to 1822, due to the failure of the potato crop, with fever and other diseases following, with the same happening in 1825. This led many to immigrate out of Ireland, some to the U.S. and others to Canada, while population of Ireland would continue to rise until 1845. For our purposes, it is worth noting that famine appeared in Ireland again, beginning in 1830, ending in 1834, spurting up again in 1836 and 1839, continuing a trend of "sporadic potato crop failures." There were food riots in Limerick in 1830, a cholera epidemic beginning in 1832, with increased immigration to the U.S. in 1833 due to the failure of the potato crop, with later failures from 1835-1837 in the counties of Mayo and Galaway most harshly. As one website pt it, "by the early 19th century everyone ate potatoes, from rich to poor, and no meal was complete without them. For some this was almost all they ever ate." Then in 1839 there was "hurricane winds...after a period of unusual weather and which saw heavy snow falling across Ireland," with the wind extinguishing "cabin lanterns, rush lights and candles," with the destruction of housing leaving many homeless,and many losing their life savings as the roof of their cabins blew away!

It is worth remembering what Alexis de Tocqueville wrote his father on July 16, 1835 about the condition of the Irish people, just like what a Hungarian would write two years later:

You cannot imagine what a complexity of miseries five centuries of oppression, civil disorder, and religious hostility have piled on this poor people. It is a ghastly labyrinth, in which it will be difficult to find one's way, and of which we shall only catch a glimpse of the entrance. [4]

This relates to an account by an individual in County Mayo, talking about the limited diet of many Irish before the Potato Famine began in 1845, saying "most families owned a cow and a calf only and those near the mountain owned a few sheep each," adding that they lived on potatoes, having "oatmeal cakes and butter and milk" from time to time, with corn sold to pay taxes and rent. They also note that flax was sown, with which they made their linens, wool provided heavier clothing, bed clothes were used as clothing, with men wearing "short knee breeches, long tailed coats, high hats, white linen shirts, long stockings and nailed boots" while women wore a "cloak with a white lined head cloth." Adding to this, a good number of Irish were Catholic, including those in County Tipperary, likely including the Mills and Bibby families, although that cannot be fully confirmed.

Even with all these famines throughout Ireland's history, the one beginning in 1845, the Potato Famine, is different. As a well-known social theorist wrote in the 1860s, earlier in Ireland there had been "repeated cases of partial famine" but "now famine was general."

All of this relates to the stories of the Mills, and interrelated Bibby families, because such famines and disruptions, especially in the 1830s, may have been one of the push factors which led them to leave Ireland and arrive in Warren County, New York. It might also be possible that the Mills and Bibby families knew each other before coming together in the U.S., which is the reason they ended up in the same county. This isn't saying that John Mills and Margaret Bibby knew each other well before their marriage, but rather that there could have been some familiar connections. They may still be descendants in Ireland, perhaps including Simon Mills, whom died in March 2017 and had previously lived in County Tipperary.

Until next time!

© 2018-2023 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

Notes

[1] All sources in this paragraph from this footnote if not otherwise noted. Don Lehane, "History of Kinsalebeg: The Great Famine," 2014; "The Siege of Galway 1651 – 1652," yourirish.com, accessed May 12, 2018; John Dorney, "War and Famine in Ireland, 1580-1700," The Irish Story, Jan 3, 2012; Maggie Land Blanck, "The Great Famine - 1845-1849," Jul 2016; Jim Lee, "Cromwell's Victory and Irish Famine," May 2017; Tim Lambert, "A TIMELINE OF IRISH HISTORY," localhistories.org, accessed May 12, 2018; "Newfoundland History – 18th Century part 1," Dec 9, 2015; "Irish Famines, Charlestown in Co. Mayo," Mayo Ireland Ltd, Excerpts from “Ireland 1845-1850: The Perfect Holocaust, and Who Kept it ‘Perfect'” by Christopher Fogarty; "Potatoes in Ireland in the 1700s," suttonelms.org.uk, accessed May 12, 2018; "Scots-Irish," accessed May 12, 2018; L. A. Clarkson, "A Non-Famine History of Ireland?," History Ireland, Issue 2 (Summer 2002), Vol. 10; Elroy Christenson, "Elroy's History of Ireland of 17th and 18th centuries," Jan 26, 2016; SilentOwl, "1739-40 Arctic Ireland. Our little ice age and The Forgotten Famine," Mar 22, 2011; "History of 18th Century Ireland," yourirish.com, accessed May 12, 2018; "The Great Frost Or Forgotten Famine Of 1740," Thurles Information, Dec 31, 2010; "1741 The Year of the Slaughter," yourirish.com, accessed May 12, 2018; Brendan McWilliams, "The Great Frost and forgotten famine," Irish Times, Feb 19, 2001; "Bliain an Áir (Year of Slaughter) – Irish Famine of 1740-1741," Stair na hÉireann, Nov 2, 2017; Paul Homewood, "The Irish Famine Of 1741," Not A Lot of People Know That, Mar 12, 2013; AJ, "Are You Irish?," HubPages, Sept 25, 2016; "The Irish Famines of ’40s," Musings from the Chiefio, Mar 16, 2012; "Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa," Maher Matters, Jan 13, 2014; Sarah Zielinski, "A New “Drought Atlas” Tracks Europe’s Extreme Weather Through History," Smithsonian, Nov 6, 2015; "People," Cecil Township Historical Society, accessed May 12, 2018; "New drought atlas maps 2,000 years of climate in Europe," phys.org, Nov 6, 2015; "What were the social and economic effects of the Famine?," History Zone, Apr 4, 2018;"The Irish Famine of 1739," from An Illustrated History of Ireland by Margaret Anne Cusack. There are also reports that there were famines in Ireland in 670, 698, 772, 773, 965, 1065, 1098, 1116, 1271, 1316-1317, and 1497. Some claimed that there were famines in 1646, 1690, but no evidence was found to prove these claims.

[2] James Durney, "THE EFFECTS OF THE GREAT FAMINE IN KILDARE 1845-50," Oct 2007; James Kelly, "Food rioting, an overlooked Irish tradition," Irish Times, Nov 27, 2017; L. A. Clarkson, "A Non-Famine History of Ireland?," History Ireland, Issue 2 (Summer 2002), Vol. 10; John Herson, "Escaping poverty and oppression in the pre-Famine Roscommon," Divergent Paths, Aug 26, 2015.

[3] Tim Lambert, "A TIMELINE OF IRISH HISTORY," localhistories.org, accessed May 12, 2018; L. A. Clarkson, "A Non-Famine History of Ireland?," History Ireland, Issue 2 (Summer 2002), Vol. 10; "Timeline of Ireland," Tipperary Genealogy, 2011; Marjie Bloy, "Famine and emigration hit Ireland: 1817," A Web of English History, Jan 12, 2016; Patrick Webb, "Emergency Relief during Europe's Famine of 1817 Anticipated Crisis-Response Mechanisms of Today," The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 132, Issue 7, 1 July 2002, Pages 2092S–2095S; Patrick O'Brien, "Top ten worst times to have lived in Ireland," Irish Central, Jun 27, 2016; Lawrence M. Geary, "William Carleton: famine, disease and Irish society," History Ireland, Issue 5 (September/October 2013), Vol. 21; "Ireland 1800’s – Outbreaks and Epidemics," The Swain Page, Sept 26, 2015; Hugh Fenning, "Typhus Epidemic in Ireland, 1817-1819: Priests, Ministers, Doctors," Collectanea Hibernica, No. 41 (1999), pp. 117-152; Chuck H., "Weather, Famine, Disease, Migration and Monsters: 1816-1819," The Historic Interpreter, May 11, 2015; "What were the social and economic effects of the Famine?," History Zone, Apr 4, 2018; "The Irish Famine of 1739," from An Illustrated History of Ireland by Margaret Anne Cusack; Summary of James S. Donnelly, Jr's book, Captain Rock: The Irish Agrarian Rebellion of 1821-1824; Noise Cleary, "The Irish Famine," O'Brien – Ireland to Van Diemen's Land, accessed May 12, 2018; "Irish Poverty Relief Loan records available online," The National Archives (UK), Jan 23, 2015; Rebecca Preston, "Was there a Political Dimension to the Irish Rockite Movement of 1821 to 1824?," accessed May 12, 2018; "Irish Famine Years- McGinnis and Donahue’s….. What Might They Have Endured," Heritage and More, Mar 8, 2013; James Durney, "THE EFFECTS OF THE GREAT FAMINE IN KILDARE 1845-50," Oct 2007; Cormac O Grada, "The population of Ireland 1700-1900 : a survey," 1979; John Greham, "The Irish Potato Famine," Your Family Tree, May 2005; Michael Byrne, "The families and streets of Birr in 1821," offalyhistoryblog, Jun 23, 2017; "Scots-Irish," accessed May 12, 2018; Noise Cleary, "Emigration," irish-roots.ie, accessed May 12, 2018; Robert McNamara, "The Great Irish Famine: Turning Point for Ireland and America," Thought.Co, Mar 6, 2017; "Food in Ireland 1600 – 1835," dochara, accessed May 12, 2018;Niall O’Ciosain, "Poverty Before the Famine, County Clare 1835," Clare County Library, accessed May 12, 2018; "The Irish Potato Famine," The History Place, 2000; Wicklow Genealogy Tours, "About Emigration and the Famine," 2017; "Life Before the Famine," accessed May 12, 2018; Richard McMahon, "Homicide in Pre-Famine and Famine Ireland," Dublin Review of Books, 2016; Thomas Cahill, "Why Famine came to Ireland," Irish Central, May 10, 2010; "Timeline of the Irish Famine," irishhistorian.com, accessed May 12, 2018; W.L. Lowe, "The Irish Constabulary in the Great Famine," Issue 4 (Winter 1997), Vol. 5; Niall Whelehan, "Labour and agrarian violence in the Irish midlands, 1850-1870," accessed May 12, 2018; Robert McNamara, "Ireland's Big Wind," Thought.Co, Oct 16, 2017; Oana Frawley, "Photography and the Visual Legacy of Famine," accessed May 12, 2018. Also see James S. Donnelly's book, Landlord and tenant in nineteenth-century Ireland, Beatrice Coogan's book, The Big Wind: A Novel of Great Famine, Michael D. Nie's The Eternal Paddy: Irish Identity and the British Press, 1798–1882, Samuel Clark's Irish Peasants: Violence and Political Unrest, 1780–1914, and Ian N. Gregory, Niall A. Cunningham, C. D. Lloyd, Ian G. Shuttleworth, and Paul S. Ell's Troubled Geographies: A Spatial History of Religion and Society in Ireland.

[4] Emmit Larkin, "Introduction" within Alexis de Tocqueville, Journey in Ireland, July-August, 1835 (USA: Catholic University Press, 1990), p 3. Other parts of the quote are within John F Quinn's Father Mathew's Crusade, Peter Quinn's Looking for Jimmy: A Search for Irish America, and Kevin Kenny's The American Irish: A History.

#potato famine#irish history#irish heritage#irish genealogy#wordpress#19th century#genealogy#ancestry#famines

1 note

·

View note

Text

THE BATTLE OF BENNETT’S ISLAND: THE NEW JERSEY SITE REDISCOVERED

It is not often the site of a Revolutionary War battle is rediscovered. It is even more unusual that the probable site is in between New Jersey’s largest trash dump and the loud rushing traffic of its most crowded highway. New research indicates that the site of the Battle of Bennett’s Island is either just inside, or on a rise of land just west of, the Edgeboro Landfill and immediately east of the New Jersey Turnpike (Exit 9 on Route 95) in East Brunswick Township in Middlesex County.

On February 18, 1777, New Jersey militia colonel John Neilson led about 150 militiamen and 50 Pennsylvania riflemen on a surprise pre-dawn raid of Bennett’s Island, located on the Raritan River to the southeast of then British-held New Brunswick. The raid resulted in the capture of Major Richard Stockton, renowned as the “land pilot” for guiding British forces across New Jersey, as well as three other officers and sixty soldiers of the New Jersey Volunteers, a Loyalist regiment. Four of Stockton’s soldiers were killed in the raid, while Neilson lost only one man. The raid also permitted Colonel Neilson and his Middlesex County militia to impede British vessels attempting to supply New Brunswick.

I had become aware of this interesting military engagement as a result of covering Richard W. Stockton in one of my prior books on kidnapping attempts, but researcher extraordinaire Chris Hay of Maple Ridge, British Columbia, Canada, had studied the Battle of Bennett’s Island in great detail and was gracious enough to share his research discoveries with me. Chris is a descendent of Stockton (a fifth great grandson).

The hero of the raid was an enterprising militia officer, Col. John Neilson of the 2nd Regiment of Middlesex County militia. Born March 11, 1745 at Raritan Landing, his family had emigrated from Belfast, Ireland. He was raised by an uncle, James Neilson, a successful New Brunswick merchant. Neilson graduated from what is now the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and then joined his

uncle’s mercantile business. Commissioned a colonel of a regiment of Middlesex County minutemen in August 1775, a year later he became colonel of the county’s 2nd Regiment of militia.[1] On July 9, 1776, Neilson gave one of the earliest readings of the Declaration of Independence, standing on a table before a crowd in front of a New Brunswick tavern on Albany Street.[2]

Where is the location of the Battle of Bennett’s Island? The most likely site is the location of the former main house at the Island Farm within the triangle created by the confluence of the Raritan River, South River and Lawrence Brook. Today this triangle is called Clancy Island and is part of East Brunswick Township. A map created by John Dalley in 1762 and in the possession of Princeton University shows the main house formerly owned by Thomas Lawrence (the great-grandson of the early settler on Bennett’s Island) in the northwest quadrant of what is now Clancy Island.[50] The Edgeboro Landfill currently takes up most, but not all, of Clancy Island.

0 notes

Text

Bonny Prince Charlie

A thing I forgot to mention about the Salty Dog saga is that, Hope the daughter and Hope the diamond aside, what I was actually looking to find out was if the Salty Dog and Bonny Prince Charlie (the dog that Col. Thomas Lawrence and his brother Captain Edward Lawrence were feuding over) were one and the same. They are different breeds of dog - Salty is a French bullbog and Charlie is a cocker spaniel - but that doesn't meant they couldn't have been meant to be the same dog at some point in development.

I didn't find anything conclusive in that area (the letter from Edward says that they brought Charlie back from France despite the cocker spaniel being an English breed which is hmm), but I might have solved another minor mystery of the game instead.

Per Wikipedia's article on the Cocker Spaniel:

Cocker Spaniels were originally bred as hunting dogs in the UK, with the term "cocker" deriving from their use to hunt the Eurasian woodcock.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

"...the new Regiment now raising": Continuing the story of the Extra Regiment [Part 2]

Continued from part 1.

Reprinted from my History Hermann WordPress blog.

© 2016-2023 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

Notes

[1] Beverly W. Bond, Jr., "Chapter III: Military Aid" within "State Government in Maryland 1777-1781," Johns Hopkins University Studies, Series 23, Nos. 3-4 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, March-April 1905), p. 38-39.

[2] While Mr. Alexander Smith resigned from the position of Lieutenant Colonel on September 1st, 1780, he was re-promoted by the Council of Maryland the following day to the same position!

[3] Journals of Congress, From January 1st, 1780 to January 1st, 1781 (Philadelphia: David C. Claypoole, 1781), 341-342.

[4] Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1780-1781, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 45, 56, 241, 367, 370, 444; Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1779-1780, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 43, 233, 234, 338; Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1781-1784, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 48, 54, 60; "Autograph Letters," American Historical Record Vol. I, No. 4, April 1872, p. 175. As Thomas Johnson notes in this July 16, 1780 letter, Mr. Cock requested to a captain in the regiment in July. Also see the pensions of Robert Green, Solomon Turner, Aquilla Smith, Wilson Moore, William Nick, John Ferguson, and Patrick Connolly for other mentions of Mr. Bayley, who has a service card on Fold3, but apparently no pension. He would later be listed as living in Frederick County, just like the rest of the Bayley/Bailey family in Maryland, and lived a total of 81 years.

[5] Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1779-1780, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 43, 335; Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1780-1781, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 45, 250, 253, 371; Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1781-1784, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 48, 54, 94.

[6] Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1779-1780, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 43, 233, 234, 262; Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1780-1781, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 45, 325, 367, 370, 415; Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1781-1784, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 48, 58, 60. A man named Edward Hood was "awarded a pension as a 'maimed' soldier in the 1st Regt. of the Maryland line" and says he "served under Captains Samuel Griffin, Samuel Jones and Nicholas Gassaway."

[7] Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1780-1781, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 45, 294, 334, 367; Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1781-1784, Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 48, 60, 94, 129; Congressional serial set (Washington: G.P.O, date not known), 133. Page 25 of Lawrence E. Babits's A Devil of a Whipping: The Battle of Cowpens, notes that Edward Giles is part of the Extra Regiment.

[8] Rolls of Extraordinary Regiment, 1780, Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, National Archives, NARA M246, Record Group 93, folder 28, roll 0034. Courtesy of Fold3.com. Here are the 29 listed on the first and second pages of the record: Jonathan Deare, Jacob Hofselton, John Burk, William Devine, Jacob Guttinger, Jacob Hofselton (different from above), Christopher Hambert, Thomas Ball, John Smith, Thomas Burk, George Hamilton, Michael McGowery, Michael Redmond, William Gillisby, John Desmond, Michael Moon, ? Graydy, John Flowson, John Barker, Isam Coleman, Thomas Glifson?, James Hopkins, Isiah Mason, John Clark, Lenard Smith (close, but not his pension), John Jackson, Josias Miller, John Anderson, and ? Gibson (crossed out). Here are the 18 soldiers listed on pages 3 and 4 (and 5?) of the document: Michael Garner, Henry Savage, Christopher Miller, Michael Longisfetter?[full name cannot be read], Michael Redman, John Barker, Thomas Burke, William Devine, John Butler, John McCarty, John Burk, Morris Leary, Gary Hamilton, Chris? Lamford, Michael McGowan, John Morris, William Falton, and Philip Fitzpatrick.

[9] The following are those listed in the full return: William Ewing, Patrick Pharple? [unreadable], Theophilus Cumford, Joseph McLain, Michael Cofner, Laughlin Fannen, Michael Longisfetter [unreadable], Henry Savage, John Butler, John Morris, William Patton, William Preft, Joseph Wright, James Thomson/Thompson who was recommended for captain of the regiment by William Hemsley, Roger Swanson, Michael Mann, John Derr who is pardoned by the governor later on (there is a John Derr with a pension who served in the Maryland Line, number S. 12762, but it is not known if this is him although some indications seem to indicate it could be; he is described as a deserter at one point), Jacob Hartman, John Burk, William Devine (some indications that pension number R.2906 is him but this cannot be confirmed), Jacob Citleringer, Jacob Hofselton, Christopher Flamb, Thomas Ball, John Smith (there are eight John Smiths who have MD pensions as an ancestry search shows, but none of them seem to be him), Thomas Burk, George Hammilton, Michael McGowan, Michael Redmond, William Gibson, John Desmond, John McCarty, Philip Fitzpatrick, William Siggs [unreadable], John Enerson [unreadable], Michael Stoelker, Peter Pomish?, John Reyler, William Deyler, John Ellison, Jonathan Parker, James Woodward, James Neel, Jacob Meyers, Morris Leary, Henry Creger, William Diach, David Crady, John Flower, John Barker, Thomas Gibson, John Colman, John C[?]Millan, James Hopkins, and John Clare.

[10] John Allison Service Card; Rolls of Extraordinary Regiment, 1780, Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, National Archives, NARA M246, Record Group 93, see pages 4-5. Courtesy of Fold3.com; John Burke Service Card; Rolls of Extraordinary Regiment, 1780, Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, National Archives, NARA M246, Record Group 93, see page 5. Courtesy of Fold3.com; William Divine Service Card; Rolls of Extraordinary Regiment, 1780, Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, National Archives, NARA M246, Record Group 93, see page 2. Courtesy of Fold3.com; John Clare Service Card; Rolls of Extraordinary Regiment, 1780, Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, National Archives, NARA M246, Record Group 93, see page 2. Courtesy of Fold3.com; William Gilasby Service Card; Rolls of Extraordinary Regiment, 1780, Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, National Archives, NARA M246, Record Group 93, see page 2. Courtesy of Fold3.com; Leonard Smith Service Card; Rolls of Extraordinary Regiment, 1780, Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, National Archives, NARA M246, Record Group 93, see pages 2-4. Courtesy of Fold3.com; William Ewing Service Card; Rolls of Extraordinary Regiment, 1780, Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, National Archives, NARA M246, Record Group 93, see page 2. Courtesy of Fold3.com; John Smith Service Card; Rolls of Extraordinary Regiment, 1780, Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, National Archives, NARA M246, Record Group 93, see page 2. Courtesy of Fold3.com; Michael Steeker Service Card; Rolls of Extraordinary Regiment, 1780, Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, National Archives, NARA M246, Record Group 93, see page 2. Courtesy of Fold3.com; Roger Sullivan Service Card; Rolls of Extraordinary Regiment, 1780, Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, National Archives, NARA M246, Record Group 93, see page 2. Courtesy of Fold3.com; Joseph White Service Card; Rolls of Extraordinary Regiment, 1780, Revolutionary War Rolls, 1775-1783, National Archives, NARA M246, Record Group 93, see page 2. Courtesy of Fold3.com. Specifically, the Fold3 muster rolls, not the serve cards, show that John Clare "deserted from Annapolis" three were sick in an Annapolis Hospital, six deserted at Head of Elk on Sept. 3 (William Ewing, Joseph White, Roger Sullivan, John Smith, Michael [last name cannot be made out], and James Hopkins), six hadn't joined (John Jackson, Josias Miller, John Anderson, Morris Leary, Thomas Gibson, John Neale), three were sick in Philly Hospital (William Gillaspie, Christopher Lambert, and Patrick Charro?), and four were on command (Josiah Mason, Thomas Burke, ? Woodward, and Michael Redman), leaving a company which is supposed to be 60, of actually only 37. Service Cards confirm this, showing that John Burke and William Devine were sick in an Annapolis hospital, that John Clare deserted from Annapolis, that William Gillaspie/Gilasby was sick in Philly hospital and Leonard Smith was sick on furlough, and having records of five who deserted at "Head of Elk": William Ewing, John Smith, Michael Streeker, Roger Sullivan, and Joseph White. Also, a man named John Allison is mentioned on a return of Sept. 29, 1780 as present, but noting else is known.

[11] These men were Thomas Pendoor, James Bigwood, George Clarke, John Higgins, John Pickering, William Stewart (close, but not his pension), Daniel Bulger, John McGuire, Edward Daw, William Cox, John Maginnis, James Barrow, Joseph Floyd, John Harvey, Jesse McCarty, Henry Crane, William Curtin (related to Thomas Certain?), John Whealand, Thomas McBride, John McCoune in place of William Quinton, Thomas Maddin, John Buller, Patrick Smith, Richard Downes, John Smith, Patrick Cavenough, Thomas Shears, Thomas Ahair, Thomas Pennifield, and Richard Kisby.

[12] These seventeen others, not including dead James North or deserter John Tucker, are: Richard Whiley, Patrick Riley, John Butcher, John Robbins, Robert Ferrell, John Jones, Elijah Clarke, John Freeman, Anthony Wedge, William Groves, Thomas Elliss, Thomas Matthews, Stephen Fennell, Thomas Burch, Charles Reynolds (possibly mentioned in this pension), Timothy McLamar, and John Clayton.

[13] The list of "recruits and deserters," were acquired by Queen Ann's County officers, including William Hemsley, for the regiment, raised in July shows 2 people who deserted before joining (Thomas Fox and Valentine Saint Tee), three former deserters who never joined (Thomas Trew, Joseph Crouch, and James Chittendon), while three former deserters did join (David Willon, Thomas Terrett, and Benjamin Loftsman). Then there are the 25 regular people recruited who are not deserters: Thomas Yewell, George Duncan, Edward Legg, Charles White, Job Sylvester, Robert Legg, Thomas Gadd, William Aller, Daniel Dulany, John West Tate, Benjamin Lee, Richard Gemmeson, Edward Vickers, Elijah Barn, John Oliver (possibly him but cannot be confirmed), William Carter, John Moore, John West, Joseph Paggat, James Baver, Lambert Phillips, John Hickins, Richard Murphy, Timothy Connor, and Edward Dominie.

[14] The other 22 men are William Clements, James Bartclay, William Jeffries, Francis Rogers, Dennis Larey, John Cooper, Elisa Huff, George Plumbley, Bauer Wibb, Frederick James, Jesse Power (close but not his pension) William Hickin, Joseph Points, William Simmons (close but not his pension), Benjamin Smith (related to the other Smiths?), John Bryan, William Campbell, John Muir, William Holt, John Lewin, John Moore, and John Newton ("wounded in two instances" as a result of his fighting in the war).

[15] Pension of Alexander Lawson Smith, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, National Archives, NARA M804, Record Group 15, Roll 2208, pension number W. 4247. Courtesy of Fold3.com.

[16] Pension of Charles Smith, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, National Archives, W 25,002, from Fold3.com.

[17] Pension of Mountjoy Bayly, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, National Archives, NARA M804, S-12094, BLWt 685-300. Courtesy of Ancestry.com and HeritageQuest.

[18] Pension of Sarah and Archibald Golder, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, National Archives, NARA M804, W.943. Courtesy of Ancestry.com and HeritageQuest.

[19] Pension of Samuel Luckett, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, National Archives, S 36,015. From Fold3.com.

[20] Pension of John Plant, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, National Archives, NARA M804, Record Group 15, Roll 1942, pension number W. 26908. Courtesy of Fold3.com.

[21] Pension of Josias Miller, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, National Archives, NARA M804, Record Group 15, Roll 1728, pension number S. 40,160. Courtesy of Fold3.com.

[22] Pension of Theodore Middleton, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, National Archives, NARA M804, Record Group 15, Roll 1720, pension number S. 11,075. Courtesy of Fold3.com.

[23] Pension of John Newton, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, National Archives, NARA M804, S.35009. Courtesy of Ancestry.com and HeritageQuest.

#notes#maryland history#maryland#extra regiment#regiment extra#american revolution#revolutionary war#us history#military history

0 notes

Text

July 6, 1917: Arab rebel force of 5,000 assisted by Colonel T.E. Lawrence & Royal Navy captured Red Sea port of Aqaba from Ottoman Empire with little resistance. This opened pathway for further military operations into Syria & Jordan.

Colonel Thomas Edward Lawrence,British Army

August 16, 1888 – May 19, 1935

Colonel T.E. Lawrence was a British archaeologist, army officer, diplomat, and writer, who became renowned for his role in the Arab Revolt (1916–1918) and the Sinai and Palestine Campaign (1915–1918) against the Ottoman Empire during the Great War. The breadth and variety of his activities and associations, and his ability to describe them vividly in writing, earned him international fame as Lawrence of Arabia, a title used for the 1962 film based on his wartime activities.

0 notes

Photo

L'EMPIRE EN PIRE... "Vieux grenadiers de l'Empereur" https://youtu.be/2GP2OnZXgcQ Charles William Stewart, 3e marquis de Londonderry, également connu sous le nom de Charles Vane - né à Dublin le 18 mai 1778 - était un éminent diplomate pendant les années des guerres napoléoniennes. Pendant la guerre d'indépendance espagnole, il se distingue dans les batailles de Buçaco et de Talavera, à tel point que le 20 novembre 1813, il est nommé colonel du 25th Light Dragoons. Le voici représenté dans l'uniforme des Hussards par Thomas Lawrence, dans cette huile sur toile conservée à la National Gallery de Londres. #leslumièresdeversailles https://www.instagram.com/p/CdtRsvQt5XZ/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

1. Born out of wedlock, Lawrence only learned his true identity after his father’s death.

In 1879, 18-year-old Sarah Lawrence arrived at the opulent Irish estate of Sir Thomas Chapman to begin work as a governess for his four daughters.

The Victorian aristocrat and his domestic servant began an affair, and she secretly gave birth to their illegitimate son in 1885.

When the scandal was discovered, Chapman left his wife and moved to Britain with his new love.

Although the couple never wed, they adopted the last name Lawrence and pretended to be man and wife.

T.E., who was the second of the couple’s five children, only learned the true identities of his parents after his father’s 1919 death.

2. The real “Lawrence of Arabia” was a man of short stature.

While six-foot, three-inch Peter O’Toole cut a towering figure as the lead in the 1962 epic biopic “Lawrence of Arabia,” the real Lawrence was only five feet, five inches tall.

Lawrence remained self-conscious about his height, which may have been caused by a childhood case of the mumps.

3. He first traveled to the Middle East as an Oxford archaeology student.

Lawrence spent the summer of 1909 traveling solo through Syria and Palestine to survey the castles of the Crusaders for his thesis.

He walked nearly 1,000 miles and was shot at, robbed and badly beaten.

In spite of the arduous journey, the new graduate returned to Syria the following year as part of an archaeological expedition sponsored by the British Museum.

His years in the region deepened his knowledge of Arabic and affinity for the Arabs.

4. He never had a single day of battlefield training.

In 1914, the British military employed Lawrence on an archaeological expedition of the Sinai Peninsula and Negev Desert, a research trip that was actually a cover for a secret military survey of territory possessed by the Ottoman Turks.

Once World War I began, Lawrence joined the British military as an intelligence officer in Cairo.

He worked a desk job for nearly two years before being sent to Arabia in 1916 where, in spite of his nonexistent military training, he helped to lead battlefield expeditions and dangerous missions behind enemy lines during the two-year Arab Revolt against the Turks.

5. Lawrence lost two brothers who also served in World War I.

Within months of each other in 1915, two of Lawrence’s younger brothers, Frank and Will, were killed fighting on the Western Front.

The guilt Lawrence felt about his safe desk job in Cairo as millions died on the front lines spurred him to the field at the outbreak of the Arab Revolt in 1916.

6. Lawrence’s fame did not come until after the war.

Overshadowed by the millions of lives lost on the Western Front, Lawrence’s exploits were largely unheralded by the end of World War I in 1918.

He was such an unknown figure that even the Turks, who had a bounty on his head, did not know what he looked like.

However, when the American war correspondent Lowell Thomas launched a 1919 lecture tour recounting his assignment in the Middle East, his photographs and films of “Lawrence of Arabia” transfixed the public and transformed the British colonel into both a war hero and an international celebrity.

7. He refused a knighthood.

King George V summoned Lawrence to Buckingham Palace on 30 October 1918.

Lawrence hoped that the private audience was to discuss borders for an independent Arabia but instead, the King wished to bestow a knighthood on his 30-year-old subject.

Believing that the British government had betrayed the Arabs by reneging on a promise of independence, Lawrence quietly told the befuddled monarch that he was refusing the honor before turning and walking out of the palace.

8. Lawrence worked for Winston Churchill.

In 1921, the future Prime Minister became Colonial Secretary and employed Lawrence as an advisor on Arab affairs.

The two men grew to admire each other and became lifelong friends.

9. After World War I, he re-enlisted under assumed names.

After completing his diplomatic service under Churchill, Lawrence returned to the military in 1922 by enlisting in the Royal Air Force.

But in an attempt to avoid the glare of celebrity, he did so under a pseudonym: John Hume Ross.

Months later, the press revealed his secret, and he was discharged.

Lawrence subsequently enlisted as a private in the Royal Tank Corps, but under the assumed name Thomas Edward Shaw, a nod to his friend, the famed Irish writer George Bernard Shaw.

Lawrence subsequently published an English translation of Homer’s Odyssey under the pen name of T.E. Shaw and maintained the assumed name until his death.

10. Lawrence died in a motorcycle crash.

Lawrence was an avid motorcyclist; he owned seven different Brough Superiors, dubbed the “Rolls-Royces of Motorcycles.”

On the morning of 13 May 1935, Lawrence sped through the English countryside on his Brough Superior SS100 motorbike.

He suddenly saw two boys on bicycles on the narrow country road and swerved to avoid them.

However, he clipped one of the bikes and was thrown forward over the handlebars.

Lawrence never recovered from his massive brain injuries and died at the age of 46 on May 19.

--------------

Colonel Thomas Edward Lawrence, CB, DSO (16 August 1888 – 19 May 1935), a British archaeologist, army-officer, diplomat and writer, became renowned for his role in the Arab Revolt (1916–1918) and the Sinai and Palestine Campaign (1915–1918) against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War.

#Colonel Thomas Edward Lawrence#Sarah Lawrence#Sir Thomas Chapman#Lowell Thomas#“Lawrence of Arabia”#T.E Shaw#Arab Revolt#Sinai and Palestine Campaign#World War I

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

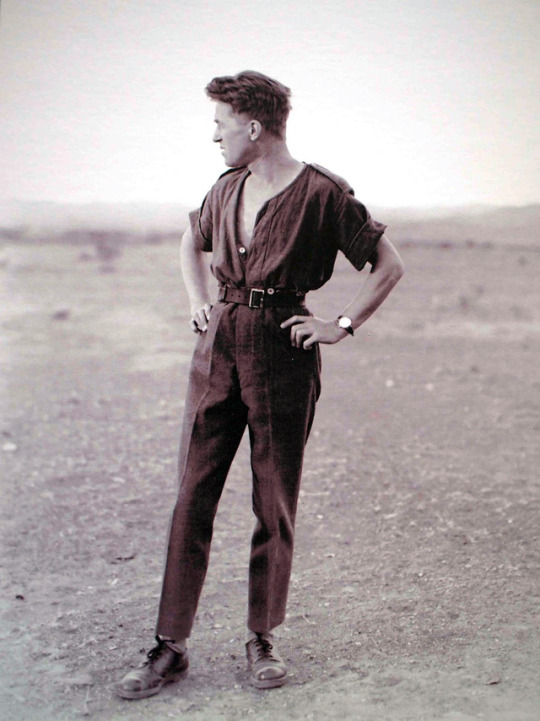

happy birthday T.E.! (16 August 1888 - 19 May 1935)

#t.e. lawrence#lawrence of arabia#thomas edward lawrence#lawrence#t.e. shaw#john hume ross#ned#edward chapman#what other names do we have#yes i refuse to post a photo of him from the war#Colonel Lawrence (he died Nov. 11. 1918)#we stan post-war t.e.#i like to see the Aesthetic Man pose and the slutty-outfit-version side by side

140 notes

·

View notes