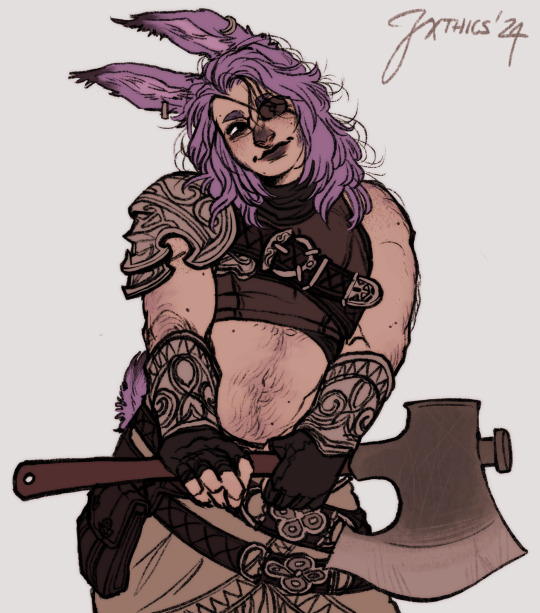

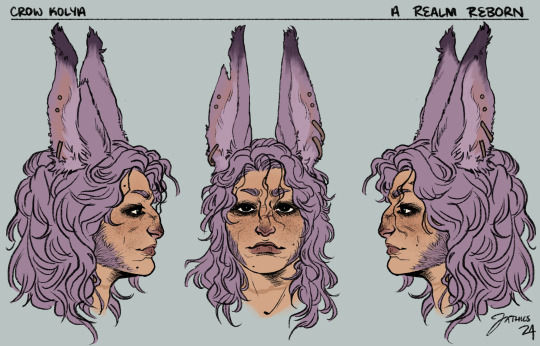

#crow kolya

Text

after many weeks of watching over my friends' shoulders, ffxiv went on sale so..... introducing my viera wol! his names crow :)

prints // comm info // patreon

88 notes

·

View notes

Note

It seems that they've given Alina more agency and made her less passive than her book version but in doing that they're messing up with other characters like Nikolai. In that one clip Alina is the one trying to convince Nikolai/sturmhond to help her when it was the other way round in the books. Also, blaming Alina & Aleks for first army keeping grisha in cages just.....are they giving him mal's personality? This show is utter garbage.

👆👆👆

I've read a post about this, but perhaps it's just skilfully cut trailer...

Maybeee...

But then again with so many changes it would be even harder to ignore annoying questions like:

Why Kolya and Sasha never meet and discuss their visions of future Ravka? Which is dangerously close to "Two revolutionaries with different believes unite to fight against the corrupt system" kind of story and we can't have "our" badass POC girlboss sidelined in her own show, can we?

That's what the Crows are for...

Nikolai is newly introduced character, easier to butcher. Less people to piss off. ¯_(ツ)_/¯

#reply#Shadow and Bone#grishanalyticritical#Nikolai Lantsov#anti S&B writers#Alina Starkov#The Darkling#General Kirigan#Darkolai#Grisha oppression doesn't matter#they told us previous season already.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unexpected

Pairing: Nina Zenik x sister!reader (Nikolai x reader)

Requested by @mrs-brekker15

Summary: Your trip to Ketterdam leads to an unexpected surprise...

You loved these trips; when your boyfriend donned his teal frock coat and left Prince Nikolai in Ravka, letting himself enjoy himself, and with you by his side, he only enjoyed himself more. Nikolai took your hand as you disembarked the Volkvolny, his beloved schooner, and wrapped his arm around your shoulder as you entered the hectic city of Ketterdam. This was one of Sturmhond’s favorite places; not only for business, but for pleasure as well.

Of course, Nikolai would never dream of setting foot in the pleasure houses of West Stave, but he’d spent a pretty penny in the gambling dens and clubs of the Barrel; the best place for the Ravkan prince to forget his responsibilities and have a little fun. That’s where you were headed now, arm in arm with your boyfriend, making your way through the winding, twisting streets of Ketterdam.

“You’ll love this place,” Nikolai told you in Ravkan. Your Kerch was horrible, the conversations of the passerby sounding like gibberish to you, but you knew that Nikolai understood every word. “The Crow Club, the drinks are insanely cheap.” You laughed and let Nikolai lead you. After a while, the facade of a building came into view: a crow perched on a nearly empty cup, and you knew this was your destination.

The bouncer knew Nikolai, rather, he knew Sturmhond on sight, and let you in without question. “Do they know we’re coming?” you asked, and Nikolai shook his head. “No, but Mr. Brekker and I have done business in the past, I’m considered a valued patron.” You nodded, seating yourself at a table, where a waitress brought you both drinks seconds later. “Kaz will want to see you,” she told Nikolai, who nodded. “I’m happy to see him.”

Nikolai translated for you, and you nodded, sipping your drink. Moments later, a man with a crow-headed can approached, removing his fedora and sidling up next to your boyfriend. “Sturmhond, a pleasure,” he greeted, and Nikolai nodded. “Mr. Brekker, may I introduce my girlfriend, Y/N Zenik.” Kaz looked at you, examining you, and you felt uncomfortable under his scrutiny.

When Kaz next spoke, it was in Ravkan. “Zenik? Your last name is Zenik?” “Yes?” you replied, completely unsure of where this was going. “Excuse me,” Kaz said, rising and limping away. “Kolya, what’s-” “I have no idea,” he said, with equal confusion on his face. “He won’t do anything to hurt you, Y/N, I can promise you that.” Before you could respond, an oh-so familiar voice met your ears.

“Y/N?” You turned and looked at who had spoken, and your eyes went wide. “Nina?” There was your sister, the sister you hadn’t seen in years, who you thought for dead, standing before you. “Oh Saints, Nina!” You were on your feet and running to embrace her in seconds, and your sister held you close, laughing and crying. “Neens, I thought… when you went to the Wandering Isle, we never heard from you, Zoya said you never… what the hell!?”

“I promise I’ll explain everything,” she said, keeping her arms around you. “It’s a long story, but I swear, I’ll tell you everything. But first, when did you hook up with Sturmhond?” “You know Sturmhond?” you asked, and Nina scoffed. “Y/N, he’s the famous Ravkan pirate,” she said, and Nikolai murmured “privateer”. “Of course I know who he is. Besides, we’ve done a few jobs with him.”

You took your sister’s hand and led her to the table, gesturing for Nikolai to stand. “I want to tell her,” you said, and Nikolai knew what you meant. “Y/N, I don’t-” “She’s my sister, love. She wouldn’t tell a soul, and she’s apparently in Ketterdam now, far away from us.” “Tell me what?” You turned to Nina, taking her hands in yours again. “Nina, there’s something I’d like to show you. Mr. Brekker, is there a private room we could make use of?”

Kaz knew what you were about to reveal, and he nodded smugly. “First door on the right,” he said, pointing down the hall. As much as he’d like to see the face of Nikolai Lantsov for himself, this was a family moment, and he wasn’t going to intrude. You, Nina, and Nikolai entered the private room, locking the door behind you. “Nina, what I’m about to show you, you can’t tell anyone. I’m serious, you can’t tell anyone what you’re about to see.”

Nina laughed nervously. “Y/N, you’re freaking me out a little,” she said, and you nodded. “I get it, but please. Promise me this stays between the three of us.” “I promise,” she said, and you knew your sister meant her words. You stood before Nikolai raising your hands to his face. You also had your sister’s gift; you were a Corporalnik. And while your focus was a Healer, you were a fairly skilled Tailor as well.

When Nikolai’s true features were restored, you pressed a kiss to his nose, a habit you weren’t willing to break. “Alright,” you said. “Are you ready?” “I guess?” your sister said, and you stepped aside. Nina gasped, her hands flying to her mouth before she dipped into a deep curtsey. “Moi tsarevich,” she addressed. “I’m honored.” She may have not been home in years, but her training from the Little Palace was still there. You must always greet the royal family with respect and veneration, she was taught.

“Please,” Nikolai said. “Don’t. There’s no need for such formality.” Nina rose, though she kept her hands folded demurely before her. “So, I suppose an introduction is in order. I’m Nikolai Lantsov, and I’m madly in love with your sister.” “And Sturmhond?” Nina asked, and your boyfriend explained his alias to your sister, who nodded in understanding. “So,” she said when he’d finished. “You’re dating a prince?”

“I am,” you responded, taking Nikolai’s hand. “And you’re going to be the princess?” You flushed, and Nikolai laughed. “Well, we haven’t gotten that far, but hopefully, yes.” Nina was beaming, and she pulled you into her arms. “Oh Y/N, I’m so happy for you! Promise you’ll invite me to the wedding, when it happens.” “Of course, Neens, now that I know you’re alive.” She smiled, hugging you again.

“And...would I be able to bring a date?” “To my hypothetical wedding that’s nowhere near being planned? Sure.” “And what if this hypothetical date to a hypothetical wedding was a Fjerdan?” “Nina,” you said, suspicion in your voice. “What did you do?” “Nothing! Nothing, I swear!” she laughed, and while you didn’t believe her, you let it go. For now, you were happy to have your sister and your boyfriend together; your heart had never been so full. “Well, this was an unexpected surprise,” Nikolai said, and you nodded. “That it was, love. That it was.”

#platonic ship#nina zenik x you#nina zenik x reader#shadow and bone fanfiction#nikolai lanstov x reader#nikolai lantsov x you#shadow and bone reader insert

191 notes

·

View notes

Text

kolya purposefully getting kidnapped by the crows to avoid everyone trying to get him married off

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

i was tagged by the super awesome @cptspeirss rules: tag 9 people you want to get to know better Relationship status: single Lipstick or chapstick: lipstick! Last song I listened to: Oceans by Seafret (I love this song so much you should totally check it out) Top 3 shows: HANNIBAL is my favourite show of all time. I guess Supernatural too but I'm super nostalgic over the early seasons, the show just feels like it's lost something. And of course, Band Of Brothers. I've really gotten into Skam recently though. Top 3 characters: hahaaha there is no way I can write down only three names. It's not possible. So, Montparnasse, Will Graham, Bucky Barnes, Steve Rogers, Jessica Jones, Gambit, Laura Kinney, Eugene Roe, Bill Guarnere, Joe Liebgott, Snafu Shelton, Sansa Stark, the whole Rogue One squad, Peggy Carter, Combeferre, Bahorel, Kate Bishop and Jesper (Six Of Crows) Top ships: Please don't judge me, I have a lot of ships. Steve/Bucky, Snafu/Sledge, Webster/Liebgott, Nixon/Winters, Joly/Bahorel, Montparnasse/Jehan, Enjolras/Grantaire, Combeferre/Eponine, Vision/Wanda, Achilles/Patroclus, Lev/Kolya, Dean/Castiel, Will/Hannibal, Jyn/Cassian, Steve/Nancy/Jonathan, Baze/Chirrut and Sansa/Margaery oh and I ship Charlie from Supernatural with me ;) i tag: @wardenhawke @amywritesxo @hannibalmorelikecannibal @webgottrash @cptlewnixon @theoutsiderstrash @toccoaairborne @snefushelton @cassianandohr and anyone else who is interested in doing this!

#Mikaela every time you tag me#in one of these I gain 10 yrs of life#you guys don't have to do this#if you don't want to#also I'm super nervous that#people are going to judge my ships#I'm just very bi#I get very excited about potential#lqbtq#stuff#also I want everyone to be happy#sort of#mostly

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

“OÙ SONT les neiges d’antan?” Throughout my childhood, at odd moments, I heard my stepfather Vasily Yanovsky — a noted Russian émigré author who provides one of the bookends to this brilliant, poignant anthology — burst out with that melancholic line from François Villon. Even as a child, I could hear its wounded beauty. Now, as an ageing translator from the Portuguese, I can see it as a manifestation of saudades, the famously untranslatable Portuguese term best glossed as a yearning, a longing, both for what is now in the past and for what perhaps never existed. One might speculate that saudades and les neiges d’antan represent a universal response to our expulsion from the Garden of Eden. We are all exiles from a vague paradise that, by its nature, is forever blocked to us, creatures fallen from grace. Bryan Karetnyk, the expert editor of Russian Émigré Short Stories from Bunin to Yanovsky, suggests this poignant connection to the expulsion of our mythic ancestors with the epigraph to his introduction, taken from John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667): “Some natural tears they dropped, but wiped them soon; / The world was all before them, where to choose / Their place of rest.”

Strange as it may seem, though born in New York and speaking at best an embarrassingly rudimentary Russian, I found myself quite at home in this anthology — at home in a world where loss was the starting point, death the never-forgotten conclusion, and love a desperately desired antidote or anodyne. Again I remember the expulsion, the rude thrusting of man and woman into a world of suffering and death, but also with the possibility of salvation: “They hand in hand with wand’ring steps and slow, / Through Eden took their solitary way.”

Memory

Along with their clear, familiar tones of joy and despair, these tales also include minor details that remind me of my Russian-American childhood in New York in the 1940s. For example, Georgy Ivanov, in his tale “Giselle,” describes a billiard player’s apartment back in St. Petersburg, where the “windows […] had not yet been sealed with extra putty against the coming cold.” And suddenly I remember, for the first time in almost 70 years, my fascination with the gray strips of putty that my grandfather, a survivor of Siberian prisons, always clean-shaven and redolent of Eau de Cologne 4711, meticulously pressed into the gaps between window and windowsill in our ordinary apartment in ordinary Rego Park, Queens, allowing me the pleasure of pushing my fingers against the softly receptive substance. This unprofessional aside leads me back to the collection, and the title of a lengthy Parisian tale by Yury Felsen, “The Recurrence of Things Past,” with its obvious Proustian echo. Like Proust’s masterpiece, this anthology is, in fact, a book of memory. And suddenly I remember that Yanovsky’s last published book was Elysian Fields: A Book of Memory (1983, translated by my mother, Isabella Levitin Yanovsky, in 1987), in which he recounts the Russian émigré experience in Paris between the wars, with firsthand sketches of many of the writers included in the present anthology. And then I notice that Bryan Karetnyk initiates this very anthology with a salient quote from Vladimir Nabokov, in response to the question: “What is your most memorable dream?” His answer is: “Russia.”

As I step back for a wider view, I see a kind of double nexus permeating this collection of stories, a nexus of the remembered, seemingly distant past in Russia (Moscow, St. Petersburg, Sebastopol) — a kind of ghost that cannot be escaped — jostling against the more recent past of eternal displacement in Berlin, Paris, Nice, or Montpellier. And this doubleness, I now realize, explains why Yanovsky gave the fictional protagonist of his best-known novel No Man’s Time (1967, translated by my mother and Roger Nyle Parris, and introduced by W. H. Auden) two names: Cornelius Yamb and Conrad Jamb. As the protagonist says of himself: “It is not at all clear who I really am. For instance, one person will say: I, and the other also says: I … Do these two feel something different or is it exactly the same?” A dilemma indeed — the dilemma of the exile.

It’s appropriate, then, to begin my survey of the themes and symbols that recur throughout this collection by looking at memory’s dream, incarnated as les neiges d’antan.

Snow

Ivan Shmelyov’s “Shadows of Days” is a lengthy, disjunctive nightmare of the past. But in the chaos of the narrator’s dreaming, religion and nature provide some solace: “I recall the lovely icons, my icons. They exist only in one’s childhood.” And then he encounters snow:

The night street shows blue. The snowdrifts are swept in mounds — you could drown in them. It has been snowing heavily all day. Great bales in snow-capped rows. It’s so quiet on our little street […] Atop the posts, atop the fences — little mounds of snow. Soft, powdery. Lanterns covered in snow shine drowsily; dogs dig up the snow with their snouts. Beyond the fence, among the birches, a crow croaks hoarsely, foretelling more snow.

For the American reader, this gentle, endless snow reminds us of Robert Frost’s ambiguous vision of stopping by woods on a snowy evening, where “the only other sound’s the sweep / of easy wind and downy flake” and where seduction is not easy to resist, for “the woods are lovely, dark, and deep.” In any case, as the dream flickers on, Shmelyov’s narrator is left with “joy, loss — all in a flash.” And when he awakes, it is in alien Paris, to the calls of a rag-and-bone man passing in the street.

In another nightmare vision, Nabokov’s “The Visit to the Museum,” the narrator leaves the titular building and finds himself, unexpectedly, in a snowy landscape:

The stone beneath my feet was real sidewalk, powdered with wonderfully fragrant, newly fallen snow, in which the infrequent pedestrians had already left fresh black tracks. At first the quiet and the snowy coolness of the night, somehow strikingly familiar, gave me a pleasant feeling after my feverish wanderings. Trustfully, I started to conjecture just where I had come out, and why the snow, and what were those lights exaggeratedly but indistinctly beaming here and there in the brown darkness.

Soon he realizes that the “strikingly familiar” snow-covered streets are those of Russia, which is now in Soviet hands. The story ends: “But enough. I shall not recount how I was arrested, nor tell of my subsequent ordeals. Suffice it to say that it cost me incredible patience and effort to get back abroad.”

Love

A possible salvation from the long shadow of displacement is love. For example, in Nobel laureate Ivan Bunin’s “In Paris,” the narrator finds love in a Russian restaurant in the guise of Olga Alexandrovna, a waitress. We assume that solace has come to the uprooted protagonists in the form of a convenient alliance, and only at the end do we understand that the younger waitress had not only found support and comfort in the well-to-do older Russian gentleman, but had actually fallen in love with him. By that point the elderly gentleman is dead and the former waitress, turned rich by his death, is “convulsed by sobs, crying out, pleading with someone for mercy.” What touched me in this tale was the understated and simple drift from a casual pickup to a true love between two Russians, making their lonely way in the alien West.

Another story that turns with an unexpected rush toward love is Irina Odoevtseva’s “The Life of Madame Duclos,” in which, after a lifetime of compromises, the Russian protagonist, having bought comfort and success by marriage to an elderly Parisian, suddenly senses salvation in the offing with a younger Russian. This time, however, the heroine can only declare herself to her mirror:

“Hello,” she will say, in Russian. She can see her lips moving in the mirror, struggling to remember the long-forgotten Russian word.

“Hello.”

She leans closer to the mirror.

“Kolya …”

And, so close now that she’s touching the cool glass, she whispers:

“I love you. I love you!”

Alas, the yearned-for lover, unaware of her feelings, has slipped aboard a ship returning him to Russia: “And then there is nothing. No ship, no happiness, no life.”

Finally, Irina Guadanini’s “The Tunnel” is a sad retelling of the author’s doomed love for Vladimir Nabokov, who was then already married to Véra. The intensity of her love is sustained through the 13 sections of the tale, but in the end the unfortunate woman, grown frantic, falls from her perch high above the Italian coast — where she was seeking distance and perspective, while also trying to spy on her lover — and tumbles downhill to the railroad tracks. There she lies, perhaps dead, perhaps only dying, but clearly reminiscent of Anna Karenina, her literary progenitor. The glory and obsession of love give way to despair. The exile does not find salvation.

Gambling

Though gambling is a universal human pursuit, Russian literature has given it a particular focus. In his notes, Karetnyk traces the literary portrayal of this obsession to Alexander Pushkin’s story “The Queen of Spades” (1834) and Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novel The Gambler (1867), which was based on the author’s own experience with the deadly fascination of roulette. In fact, Dostoyevsky used proceeds from the novel to pay off large debts he had accumulated in the casino. In this collection, we encounter, in Georgy Adamovich’s “Ramón Ortiz,” an Argentine version of Dostoyevsky’s obsessed youth. With no restraint, no realistic self-appraisal, the young man, fond of being considered a baron, gambles his way from early success to utter destitution and resolves his situation by committing suicide. The narrator approves of this final act, seeing it as a proper response to the universe’s indifference toward the individual’s sufferings. Adamovich himself was the chief arbiter of the Paris Note, a Russian-Parisian literary movement that sought, in Karetnyk’s words, “to combine the despair of exile with the modern age of anxiety.” Certainly Ortiz’s suicide can be seen as indicative of both the despair of exile and the age of anxiety pressing on these displaced people. And I recall that shortly before Adamovich died, Yanovsky invited him to his home in New York to meet W. H. Auden, the man who coined the very phrase “Age of Anxiety.” It was a great satisfaction to Yanovsky to bring together the two intellectuals he admired most, one from his youthful years of exile in Paris, the other from his mature exile in the United States. Within one year of that meeting, both Adamovich and Auden were dead.

One of those who gambled over the bridge table with Yanovsky and Adamovich in Paris was Vladislav Khodasevich, whose story “Atlantis” depicts a circle of obsessed Russians immersed in games of bridge in a basement below the cafe Murat. (Interestingly, the lost land of Atlantis is also the setting for Yanovsky’s unpublished short story “The Adventures of Oscar Quinn.”) And in Dovid Knut’s “The Lady from Monte Carlo,” we again encounter an obsessed gambler, who can see the truth in others, if not himself: “these indifferent people [are] eternally — tragically — lost and disassociated from one another.” He is tempted by an older woman with a secret for winning (borrowed from Pushkin’s tale a century earlier), but in this version we have a seemingly happy ending: the ancient temptress resists her own urge to pass along her secret and insists that he leave her. Still, indifference reigns: “She kissed my forehead. The evening was cold, majestic, and indifferent.”

Chaos

Entropy is, of course, our common foe — the one to whom, in the end, we must succumb. But for the exile, the onslaught of chaos can come early and in a heightened, phantasmagoric form. Here are snippets of chaos from Shmelyov’s “Shadows of Days”:

Night. Snow. I’m in the alleyways. […] Dead houses, closed gates. I’m lost, I don’t know where mine is. […] Dark, blind buildings. They’ve all gone. Now there’s just one road — […] I run in trepidation. The Champs-Élysées, my final road. […] The Elysian Fields! […] The end!

And “It’s them, they’ve come for me … I know it. […] The trees and the wind are whispering. Footsteps below the windows. I listen — a scratching at the window sill, they’re climbing up. […] I scream, I scream.”

In the anthology’s final text, Yanovsky’s “They Called Her Russia,” we encounter a vortex of entropy in a circular vision of hell: a trainful of soldiers going round and round through jumbled fields, never engaging “the enemy,” slowly spiraling through the repetitive brutality and madness of the Russian Civil War toward utter dissolution. In fact, it is never clear who the enemy is. Their own “engine-driver offered to find a way through to the Reds; the stoker tried to persuade them to join the partisans.” Eventually, “[t]hey decide to break through up ahead: if not Whites, then Reds — whomever they meet.” In this nightmare — where the commandant’s refrain is “Dream or real?” — the enemy they engage is themselves.

Two Horses

It seems appropriate to conclude with the most painful, touching image I found in this anthology, an image that occurred twice: a horse without a rider, striking out into the sea — one in Gallipoli, the other in the Crimea. Both horses are valiant, yet have nowhere to go, no function to fulfill; nothing awaits them but death in an alien sea. They are abandoned by history. The narrator of Ivan Lukash’s “A Scattering of Stars,” a poetic evocation of the retreat to Gallipoli, tells of his beloved horse and its shameful end:

I spot my Leda […] craning her neck towards the water, whinnying, nostrils flaring. […] I see her suddenly, with all four legs, leap into the water. She couldn’t bear the thirst. She went crashing down, placed her lips to the sea salt and began jerking her head about. She jerked her head, Leda did, but she was soon swept away by the current.

And in Galina Kuznetsova’s “Kunak,” the denouement is even more poignant: “Above the grey misty water, a horse’s head could be seen craning. It was swimming apparently without knowing where it was going, borne by the current out towards the middle of the bay.” A rowboat comes to the rescue, but in fact only offers the hopeful horse three sudden bullets in the head, and then “the current was freely, and with terrible speed, bearing it away. It disappeared again, then reappeared … until finally it vanished for ever in the quick-flowing water.” The onlookers “all gasped in horror and compassion.”

And there we stand, observers of an entire culture carried out to sea, but with nowhere to go. There is much grimness, much pain, much despair in this collection, but it is also struck through with deep emotion and a pulsing sense of life. We contemplate the struggle of the exiles with horror and compassion, for we know that, at some level, we all share their plight.

¤

Alexis Levitin, a professor of English at the State University of New York at Plattsburgh, translates works from Portugal, Brazil, and Ecuador. His 40 books of translation include Clarice Lispector’s Soulstorm and Eugénio de Andrade’s Forbidden Words, both from New Directions Publishing.

The post “Où sont les neiges d’antan?”: On “Russian Émigré Short Stories from Bunin to Yanovsky” appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books http://ift.tt/2C2EoLW

0 notes

Text

WARRIOR - OF - LIGHT

#veena viera#viera wol#ffxiv#ff14#final fantasy xiv#final fantasy 14#johnnydraws#wol#myocs#crow kolya#ffxiv arr#a realm reborn

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

the warrior of light, from ARR to HVW

#ffxiv#ff14#final fantasy xiv#final fantasy 14#veena viera#viera wol#wol#warrior of light#johnnydraws#myocs#flats#crow kolya

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

so give me something to believe

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

Does your WOL Crow have any posts about their backstory? 🥺

i have not posted about him much but i can now! crow's a 76 y/o veena viera, adventurer and scion. he's originally a wood-warder from the skatay range, but left to travel eorzea after curiosity and strange dreams got the better of him. this drawing is a wip but here he is (left) with his mentor nikolai (right) back when he was a wood-warder!

#jacasser#myocs#crow kolya#ffxiv#ff14#final fantasy xiv#final fantasy 14#thank you for asking!!! i love talking about him!

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

antibiotics are kicking my ass but i wanted to scribble my wol before i laid back down. i miss you crow

#ffxiv#final fantasy xiv#wol#viera wol#johnnydraws#sketches#myocs#crow kolya#when i can sit upright for long and not be so gd nauseous ill be back for him.....

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

i love looking at your art even if i have no idea who the characters are

thank you sm!!! yeah i've taken a hard turn to final fantasy rn so expect a lot of my wol/character/oc crow soonish haha

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

Did any moments in heavensward bit hardest?

all of it. consistently. hvw has just been a nonstop kick in the teeth and it was NOT on purpose. he got hit with "oh im not actually that hot shit" and then everything Happened And Kept Happening. hvw spoilers

like. he keeps getting connected to people and then they keep Dying. i think the worst of it has been losing the echo, though. ):

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Emotionally, what were Crow's Highest and Lowest moments of ARR? Was there a side quest that's stayed with him somewhere in the middle?

highest point: end of post-ARR, where they're gearing up to move from the waking sands -- collecting shells with tataru was very important to him :')

lowest point: um. probably when minfilia Was Missing. that messed him up a lot! he's very close with her.

i can't think of sidequests because i haven't Done a lot of them. i'm very msq oriented

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

preface that the most ffxiv ive played is the character creator because everythnig after that crashed. anyways how does your guy change over the course of the game? does he undergo any big like.. perspective/worldview/philosophical changes? if so, are they gradual or lightbulb moments or both or...? also. what's a core thing he believes in at the "end" of the game and what would it take for him to do a 180 on that belief?

oh ABSOLUTELY. he's currently struggling with the concept of light/dark and his like... Purpose. (& i've been told this will only get worse as i continue the msq into shadowbringers.) he's nowhere near the end of it right now but we shall see!

post-heavensward spoilers below

crow has an ability called the echo that he very, very heavily relies on -- it's how he can understand the local language, intuit emotions of the people around him, and without it, he kinda... spirals, and gets distant/cut off from other people. because of the events of the main story he lost his gift and became a dark knight to have something else to rely on, but when tapping into dark powers turns out to be hard to control. Yeah. he eventually got his gift back, but now hes shaky about using it because he's seen what can happen if it's out of his control.

crow started out as a very cocky/confident type and the deeper he goes the longer his imposter syndrome is getting the better of him because ^ of all of that. he doesn't view himself as extremely competent, or even all that Good by himself - he does heroic things because the echo + the people around him demand a hero, not because he himself is heroic. so. things are rough right now! he's very slowly figuring it out.

as it stands right now he's also very broken up about losing his partner minfilia so. :')

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can he and my wol be friends (/j) And who of his companions that he's met thus-far do you think he gets along the best with? Who do you think he clashes with the most?

yes (/hj i love hanging out with people!)

he's gotten along the best with minfilia honestly, i ship them and they're very dear to me. nero is not a companion (yet, for now, etc) but he clashes the most with him. he's also very close with cid!

1 note

·

View note