#fin de siecle fairytales

Text

An example of the book's fascinating studies: as I said before, the chapter about Sleeping Beauty notices how fin-de-siècle authors, when "perverting" the tale, focused on the fairies around the baby's cradle - and Jean de Palacio notices that the names chosen for these fairies are very revealing of this "perversion".

Indeed, some authors in their twist-take on Sleeping Beauty, decided to name the group of fairies around the cradle. Anatole France, in his take on the Sleeping Beauty story in 1909, listed eight fairies: Titania, Mab, Viviane, Mélusine, Urgèle, Anna de Bretagne, Mourgue. Catulle Mendès, in 1888, had evoked in his work a total of 12 fairies - Oriane, Urgande, Urgèle, Alcine, Viviane, Holda, Mélusine, Mélandre, Arie, Mab, Titania, Habonde. Jean Lorrain did this list twice - once in 1883 including Habonde, Viviane, Tiphaine, Oriane, Mélusine, Urgèle, Morgane ; and another in 1897, simply removing Urgèle. As for Joséphin Péladan, he also did a double list: one in 1893, Mélusine, Morgane, Viviane, Mourgue, Alcine ; and another in 1895 to which he removed Mourgue to add Urgèle, Nicneven and Abonde.

These names can be taken as just random famous fairy names - but Jean de Palacio highlights that... They are not just chosen randomly, and all denote a way to discredit the fairies or to highlight their ambiguous if not negative nature. Of the recurring names four are taken from the matter of Britain, Arthurian and medieval legends: Viviane, Melusine, Anna de Bretagne (a variation of Anne of Britanny, an actual queen of France) and Mourgue/Morgane. Famous characters, right... But who is present here, around this baby's cradle to deliver gifts? Morgan le Fay, half-main villain of the Arthuriana half-healer of Avalon. Viviane, the good lady of the lake, oh yes... but also a shameless seductress who used Merlin's lust and love to steal his secrets and get rid of him. And Melusine - a national treasure, one of France's beloved legends... And a snake-woman with a strong demonic aura and devilish reputation. Viviane, Melusine and Morgan are all manifestations of the "femme fatale", of the deadly though seductive woman.

There is also a British influence at work here, since we have Titania and Mab, the two famous Shakespearian fairy queens. But Titania's reputation had already been soiled in Shakespeare's play by her mad love for a donkey - sorry, an ass ; as for Mab, in the minds of fin-de-siècle century, she is still strongly associated with the "materialistic atheism" of Percy Bysshe Shelley's poem "Queen Mab". Not perfect example of "godmothers"...

But let's return to Mourgue/Morgue briefly. Yes, she is the Franco-British Arthurian character of Morgan le Fay... But she is also part of the Italian literary tradition thanks to the Orlando Furioso, where she is Morgana, the incest-born sister of the enchantress Alcina who... Oh look! She is there too! Alcina in French is "Alcine" and in the lists you find... Alcuine. Once again, a new discredit over the fairies, as you have two wicked enchantresses dedicated to the dark art - including a lustful old hag so vain she hides her true appearance under a glamour of youth and beauty.

Of the various fairies presented in this list, only Urgèle seems to be free of any same, flaw or negative side - but that's because she is the most "recent" of them all, and not an old literary heritage or cultural figure, but rather a fresh creation. Urgèle was created by Voltaire in 1764 for a short tale/fairytale of his, "Ce qui plait aux dames", "What pleases the ladies", and immediately taken back for an "opéra-comique" adaptation by Favart in 1764, "La Fée Urgèle, ou Ce qui plaît aux dames". And while Théodore de Banville made her a good fairy victim of a wicked enchanter in his comedy "Le Baiser", "The Kiss" ; it didn't refrain Michel Carré and Paul Collin to make her the wicked fairy of Sleeping Beauty in their theatrical-opera adaptation of the fairytale in 1904...

[As a personal note, if you are interest in the other fairy names, Habonde is a variation of Abonde - la fée Abonde was a figure of popular folklore and superstitious beliefs in medieval France, an embodiment of abundance and prosperity fought off by the Church and who was tied to the rite of leaving "meals for the fairies" on special nights such as Christmas or the Epiphany. Holda is of course the same as Frau Holda/Frau Holle of Germanic mythology ; Arie is a reference to "Tante Arie", a Christmas gift-giver of eastern France, and Nicneven is a variation of Nicnevin/Nicnevan of Scottish folklore. I have to admit I do not know about the origins of Mélandre or Tiphaine.]

#sleeping beauty#fin de siecle fairytales#jean de palacio#fairy godmothers#fairies#famous fairies#fairytales with a twist

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Fairy tales from folk lore’ by Hershel Williams; illustrated by M.H. Squire. Published 1908 by Moffat, Yard & Company, New York.

via

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

transgression, the other, and the evolving shape of the gothic: a comparison of the bloody chamber and dracula

transgressive behaviours are at the forefront of gothic literature, a device used to impart messages surrounding temporally relevant cultural fascinations and anxieties. this theme runs throughout the reactionary genre’s timeline, including through bram stoker’s contribution to establishing the progression of gothic tropes in the victorian era, and angela carter’s 1970s prose. stoker’s fin de siecle novel explores the threats that transgressive behaviours pose to social norms and british values through binary oppositions, drawing upon victorian fears of reverse colonisation, sexual liberation and disease. conversely, carter’s modern subversion of the gothic explores these threats via stories of transformation and metamorphosis; both authors utilise the supernatural to personify these menaces to the norm, as is a vital characteristic of the genre. by having non-human characters commit explicit acts rather than humans, gothic authors can characterise the acts as monstrous and convey messages surrounding what these threatening acts mean for the characterisation of humanity. as put by kelley hurley, ‘through depicting the abhuman, the gothic reaffirms and reconstructs human identity.’

stoker’s traditional prose utilises the gothic concept of binary opposition in order to depict and villainise the threats posed upon his idealised christain characters by dracula. dracula himself, as an abhuman entity, is representative of sexual fluidity and the risk of sexually transmitted diseases, ideas which are consistent with vampirism but are at odds with victorian english values. lucy’s brutal punishment, however, is contrasted with the anticlimactic demise of dracula himself, where his ‘whole body crumbled into dust and passed from our sight.’ stoker could be using this opposition to suggest that those who give in to threats against typical societal conventions and fail to uphold british values are more deserving of punishment than those who actually pose the threat. the contrast provides an implication of moral inferiority: while villains are transgressive by nature, their victims who fail to resist their ideologies betray the moral code they originally conducted themselves upon. this initial betrayal is what allows the threatening character to infiltrate the population and continue to corrupt the ‘good’ characters. buzzwell supports this, suggesting that ‘lucy’s moral weakness allows dracula to repeatedly prey upon her.’ stoker arguably serves as an other himself, writing as an irish protestant in london. the opposition he constructs here between lucy and dracula’s respective manifestations of vampirism not only examines cultural variations but exemplifies and exaggerates the differences in the reactions of other characters towards them. given the author’s own ‘otheredness’, we could consider the novel a criticism of victorian xenophobia, where o’kelly argues that stoker ‘[pokes] fun at some of the victorian era’s most cherished beliefs.’ however, this view of the novel’s depiction of threats to the norm is highly disputed, with gibson highlighting stoker’s own russophobia as ‘a hatred that determines dracula’s negative portrayal as a condemnation of the orthodox eastern and slavic peoples historically allied to russia.’

contrastingly, carter’s presentation of characters succumbing to villains who jeopardise established values centres around ideas of solidarity, which she demonstrates through the ‘victims’ experience of metamorphosis. her techniques differ from stoker’s in that his use of binary oppositions is undoubtedly traditional of both the gothic and of the manichean mentality of victorian england. the usage of metamorphosis, on the other hand, allows carter to force audiences to grapple with liminality and she suggests to them that ‘othered’ groups or individuals are not entirely evil. this is a view which reflects carter’s modern, second-wave feminist perspective. jaques derrida’s ‘theory of the other’ posits that ‘otherness often provokes a paradoxical response in the viewer: fascination and repulsion.’ often the fascination is morbid, working in conjunction with repulsion: audiences are curious to understand what disgusts them. the tiger’s bride and the courtship of mr lyon, two stories within the bloody chamber collection, are subverted retellings of the traditional ‘beauty and the beast’ fairytale. while maintaining the general events of the original ending, where beauty stays with the beast of her own volition, carter offers up two dynamics between the human and abhuman that serve to recharacterise ‘othered’ creatures as less threatening and more sympathetic and innocent.

the courtship of mr lyon characterises mr lyon as a ‘leonine apparition’ and an ‘angry lion’ throughout, emphasising his predatory nature and resulting in negative connotations surrounding his ‘otherness.’ his initial threatening aura is quickly negated soon after beauty’s introduction to him, as they warm up to one another, and the story concludes with mr lyon’s transformation into a human man: ‘her tears fell on his face like snow and, under their soft transformation, the bones showed through the pelt, the flesh through the wide, tawny brow. and then it was no longer a lion in her arms but a man…’ carter’s use of metamorphosis here humanises a character that would otherwise be considered a threat to traditional norms, suggesting to readers that he may have been ‘just like us all along.’ his change in physical nature is triggered by beauty’s display of affection for him; implicit in this is the notion that we can undo our villainisation of marginalised people, and emphasises the significance of understanding between privileged and unprivileged groups. carter draws the line between what is a threat and what is simply unconventional, stripping marginalised identities of their ‘dangerous’ qualities that are attributed to them by those who abide by social norms. similarly, the tiger’s bride uses metamorphosis to suggest that those who challenge established identities are not inherently menacing, and that typical and atypical creatures can coexist. rather than have a character transform from beast to man as in the previous story, carter’s ending depicts a woman-to-beast transformation. this serves to suggest that people’s desire to understand what disgusts them can manifest as identifying with the ‘other’ and unlearning their own prejudices against them. beauty’s transformation is detailed in the closing sentences of the story: ‘and each stroke of his tongue ripped off skin after successive skin, all the skins of a life in the world, and left behind a nascent patina of shining hairs. my earrings turned back to water and trickled down my shoulders; i shrugged the drops off my beautiful fur.’ beauty’s metamorphosis can be read as a sign of solidarity towards the beast, or an understanding of his nature. roberts posits that ‘to be beast-like is virtuous. to be manly is vicious.’ carter takes this concept and uses it to criticise conventional reactions to unconventional behaviours. she deconstructs the binary that stoker relies upon, and uses a far more modern gothic convention to negate his black-and-white depiction that presents anything challenging the norm as a threat that can infiltrate civilised society, and instead presents these ‘threats’ as liberating.

perhaps an incredibly modern reading of carter’s metamorphosed characters is as an allegory for transgenderism. discussions around gender identity during the 1970s in britain, even in second-wave feminist circles, were more concerned with rejecting and redefining traditional gender roles than they were with the personal identity of individuals, so we can assume this was not carter’s intention when writing these stories. however, ideas of physical transformation, and how proximity to the ‘other’ can ‘radicalise’ one’s own identity are very fitting with treatment of transgender people both historically and presently. genres that stem from the late gothic, namely sci-fi, have been known for using metamorphosis as an allegory for marginalised identities, using physical transformation as an allegory for ideological or emotional transformation. a prime example of this is lana and lilly wachowski’s series the matrix. written as a trans allegory, the movie series criticises the social pressure for conformity the way carter does and attempts to explicitly recharacterise trans people as an innocent non-conforming identity rather than a threat. carter’s exploration and reproval of established values similarly tends to centre around ideas of gender, making this reading not entirely unreasonable. carter and stoker’s gothic texts are equally reflective of cultural anxieties in their respective temporal contexts, but where stoker reinforces racist ideologies that are at the heart of british imperialism and victorian politics, carter suggests that societal fears surrounding gender identity and liberation are unfounded.

both carter and stoker identify the victimisation of women as an established norm that is essential to the functioning of a patriarchal, capitalist society, but once again carter criticises this and stoker instead reinforces it. the notion of female vampirism is a vehicle for this discussion in both gothic texts, particularly in terms of how these supernatural women contain sexual traits that simultaneously fascinate and repel other characters. this duality is vital to what characterises them as a threat: jullian identifies ‘the gothic…’ as a genre ‘where danger is so near to pleasure’. the sexualised traits of vampire women is what allures other characters to them and allows them to infiltrate civilised society. stoker’s ‘hostility to female sexuality’ as described by roth, bookends the events of the novel with the early introduction and later reappearance of the eastern vampire women of dracula’s. their overt sexuality is repeatedly described as purposeful, with explicit juxtaposition between their attractiveness and the threat that they pose: 'there was a deliberate voluptuousness which was both thrilling and repulsive.’ these women are an extension of dracula that serve to specifically explore the threat of sexual fluidity, and the crew of light’s destruction of dracula ultimately eliminates that threat. van helsing’s justification of killing these women, 'then the beautiful eyes of the fair woman open and look love ... and man is weak', demonstrates that it is men’s inability to resist sexualised creatures that will result in this threat infiltrating england, but the responsibility is placed upon the women. while this echoes stoker’s suggestion that those who succumb to villains are at fault, it inevitably criticises women regardless. kaplan argues that ‘the sexualisation and objectification of women is not simply for the purpose of eroticism; for a psychoanalytical point of view, it’s designed to annihilate the threat of women.’ the threat that kaplan refers to here is that of the new woman, an early feminist concept arising in the late 19th century. the new woman is entirely threatening to established victorian values as she ‘was often a professional woman who chose financial independence and personal fulfilment as alternatives to marriage and motherhood.’ (carol senf) by acting opposite to the ideal victorian wife, the new woman challenges normal behaviours and expectations. this is another example of stoker exploring threats to the norm via binary opposition: mina is contrasted with the vampire women, including lucy, a contrast pitting an ‘angel in the house’ character against new women. mina’s pious, devoted and submissive wifely characteristics fit the victorian ideal known as the ‘angel in the house’, a title that originates from coventry patmore’s poem in which he depicts his wife as a model for all women. this stark contrast illustrates how female sexuality threatens the value women are attributed as it prevents them from performing their expected duties for men. having a threatening or taboo act committed by a supernatural figure is a hallmark of the gothic and serves to convey to readers that the act or concept is monstrous. female sexuality is a common victim of this trope during the early and fin de siecle gothic periods, but has since been commonly subverted and empowered in more modern gothic literature.

for instance, the lady of the house of love is the most conventionally gothic text in the collection, using traditional purple prose and exaggerated, decadent settings to frame discussions about heredity, sex and death. it features a countess, whom carter depicts as simultaneously being a victim and a villain. the duality of her character is a result of carter’s signature liminality, wherein the lines between what is threatening and what is innocent are blurred to explore female sexuality as a complex trait rather than fitting the ‘good vs evil’ binary that stoker attempts to attribute it to. much of her characterisation mimics that of stoker’s vampire women, but is subverted to present the countess as a sympathetic villain: ‘her beauty is an abnormality, a deformity... a symptom of her disorder.’ the girl’s attractive traits are made synonymous with a deficiency or sickness, as is the fact that men are inevitably attracted to her. carter suggests here that the girl’s reliance on seducing men for her survival is a hereditary curse, implicitly commenting on the generational trauma women face as a result of having to rely on their relationships with sexually threatening men in order to live financially comfortable lives. this mimics the way in which society relies upon established values and social norms even though they restrict and stifle us. the countess weaponises her sexuality, and while her motivation is survival, this act is conventionally taboo and is therefore committed by a supernatural entity, to traditionally characterise it as monstrous. while carter does draw on this typical gothic trope, she uses sympathetic language to paint the countess as ‘helplessly perpetuating her ancestral crimes.’ the ending of the story, however, mentions the first world war and carter hints at the notion that humanity itself is more dangerous, more of a threat, than the threat of the perceived supernatural ‘beasts’ that people project their fears onto. once again, carter feeds into kelley hurley’s idea that ‘through depicting the abhuman, the gothic reaffirms and reconstructs human identity.’ liminal characters, such as vampires or characters like frankenstien’s monster in mary shelley’s ‘frankenstien’ that exist between life and death, exist as vehicles to discuss the complexities of human nature.

ultimately, carter paints various traits and identities that are widely considered ‘threatening’ to be multifaceted and liberating instead, as she views the established values that they ‘threaten’ to be restrictive and in need of changing. in the preface to the bloody chamber collection, helen simpson writes that 'human nature is not immutable, human beings are capable of change', arguing this point as the core of carter’s work. she suggests through her writing that what is perceived as a social threat is often based upon what is uncomfortable rather than what is actually dangerous. her work is partially ambivalent in that it does not instruct what is right or wrong the way stoker does, but instead depicts societal relationships and allows the audience to interpret it. stoker’s use of transformations that involve protagonists always has them revert back to their original state, a reinforcement of the status quo. those who do not revert to the norms are killed or punished, eradicating the threat and putting readers at ease. the exploration of threats is central to the gothic as a genre that depicts and discusses transgressive behaviours and the implications they have for wider society. as put by punter, ‘the gothic is associated with ‘the barbaric and uncivilised in order to define that which is other to the values of the civilised present.’

i.k.b

#essay#literature essay#mine#copyright ikb#gothic#gothic literature#dracula#bram stoker#bram stokers dracula#mina harker#jonathan harker#angela carter#the bloody chamber#the bloody chamber collection#books and literature#early gothic#late gothic#feminism#trans literature#female villains#vampires#nosferatu#victorian literature#female vampire#transgression#feminist literature#1970s art#reverse colonisation#colonisation#british empire

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 4 lecture review

The Contextual review

This mornings lecture was really insightful and helped me to understand how to break down my topic into smaller sections that help to frame my overall idea. He talked about a few things in terms of the technicalities of the contextual review section of the exegesis. Paraphrasing is typically used instead of quoting, chronological order of case studies and practitioners mentioned helps give structure and flow to your writing and including recent studies or research helps to show you are knowledgable about the current developments and findings within your chosen field or topic.

Creating a contextual neighbourhood that surrounds your own work and ideas helps to frame the importance and relevance of what you are creating. I Liked what he said about a Literature review not being as relevant to design because there are so many projects or case studies out there that help you to shape and position your knowledge on a topic. Visual research and looking into the way that people have made things is just as relevant.

I also liked what he said about Designers having the job of ‘Shaping knowledge to make it accessible to people’. Something about the way that he phrased this re iterated the idea of what communication design is and its importance to the wider community.

New words or ideas picked up from the lecture

Disjecta Membra: This was a new phrase that I picked up from this lecture that refers to a few fragments you can put together to get an idea of the whole picture.

Intertextual reference: This is the idea of relating an idea to something else that is already in existence. Sometimes this can be a parody or paying homage to the exisiting work while other times a vague reference is enough information. I liked this example in the Three little pigs Ad that was created for the guardian. referencing a fairytale story but using it in a modern context to make it both interesting and relatable was a clever way of engaging an audience.

Fin de Siecle: This was a word that I picked up that refers to characteristics or nature of the turn of the century (specifically the 19th century). I thought since i am looking into art Nouveau as an illustration style for my work that this could be a good key word to have in my back pocket.

Explicit research: Physical in the world knowledge. Collecting research from things and places that exist physically. (Example used was getting of the computer and going to the library to research: Physicality of the place and books.)

Tacit Knowing: The collection of knowledge through experience and practice, not always consciously. You might not realise that you are collecting this knowledge but the idea is that this unconscious collection of knowledge can be used to inform decision making and intuitive process later on.

0 notes

Text

The Greatest Gardens Of 2020

The Greatest Gardens Of 2020

Gardens

Sasha Gattermayr

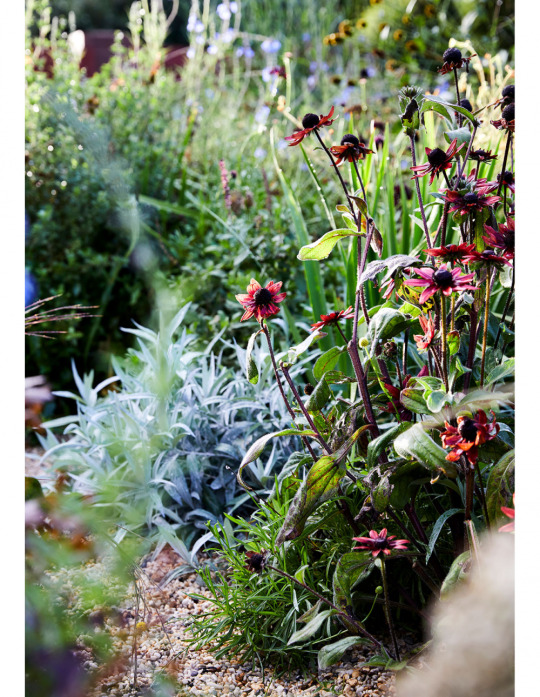

The gardens at Picardy by Bruce and Marian Somes. Photo – Sue Stubbs.

The gardens at Picardy by Bruce and Marian Somes. Photo – Sue Stubbs.

The gardens at Picardy by Bruce and Marian Somes. Photo – Sue Stubbs.

A French Provincial Dreamland In West Gippsland, Inspired By Monet’s Giverny Garden!

You’d be forgiven for thinking this house was in Normandy, because that’s exactly where owners Bryce and Marian Somes want to transport you. Inspired by Monet’s Giverny, the Somes have been tending to this 26-acre plot in West Gippsland as an homage to the great European gardens of the fin-de-siecle. Named Picardy, the gardens are in constant bloom throughout the year, with different sections designed to flower in different seasons – and the pair of francophiles are constantly adding new parts!

Revisit the original story here.

The Mollymook garden by Dangar Barin Smith. Photo – Prue Ruscoe.

The Mollymook garden by Dangar Barin Smith. Photo – Prue Ruscoe.

A Dreamy, Generous Coastal Garden

The Mollymook garden by Dangar Barin Smith is so incredible, it’s become a tourist destination! Townsfolk and visitors alike come to marvel at the landscape, which wraps around the home (designed by MCK Architects) and contains a mix of tropical and native plantings. The best part? The absence of a fence-line – which means the lush vegetation rolls out into the ocean via a garden path that leads visitors straight down to the beach. Dreams!

Revisit the original story here.

The studio garden by Kathleen Murphy Landscape Design. Photo – Marnie Hawson.

The studio garden by Kathleen Murphy Landscape Design. Photo – Marnie Hawson.

The studio garden by Kathleen Murphy Landscape Design. Photo – Marnie Hawson.

A Landscape Designer’s Own Ever-Changing Garden

Of course, we would be remiss not to include the winner of the Landscape Design category of our very own TDF + Laminex Design Awards 2020 – Kathleen Murphy!

The landscape designer’s own studio garden in the Macedon Ranges is as much a place for family relaxation as it is for experimenting with new plants. Designed to frame the mountain views as well as create a verdant green vista when viewed from the house, layers of robust, textured plantings are complemented by pockets of delicate flowerings. Practically perfect in every way.

Revisit the original story here.

‘At the end of the day my greatest satisfaction is looking out over what has been created and the feeling of calmness it evokes,’ says Sam. Photo – Kim Selby.

Being her own space, the garden is a constant work in progress! Photo – Simon Griffiths.

A Landscape Designer’s Own Sumptuous Green Wonderland

Sam Crawford has been working on her garden in Clarkefield for the last eight years. A trained horticulturalist and landscape designer (under Kathleen Murphy!), when her husband inherited his family property Sam scored the enormous garden. She set about transforming it into a highly original landscape, incorporating native plantings and her own ideas into a traditional country garden model. It’s a bona-fide paradise!

Revisit the original story here.

The Deepdene Garden by Ian Barker Gardens. Photo – Claire Takacs.

The Deepdene Garden by Ian Barker Gardens. Photo – Claire Takacs.

A Majestic Restoration For A Legendary Heritage Garden

Allegedly designed by William Guilfoyle in the 1860s (the creator of the Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria himself!), this one-acre property in the Melbourne suburb of Deepdene required the perfect landscapers to undertake the historic restoration project. Ian Barker Gardens were up for the job, taking care to preserve the original plantings (some of which were over a century and a half old!) and rework a sympathetic layout with painstaking faithfulness to the original design. It’s even listed on the National Heritage Trust!

Revisit the original story here.

It’s never lonely in Lily’s garden! Photo – Amelia Stanwix for The Design Files.

Lily Langham’s garden in Daylesford. Photo – Amelia Stanwix for The Design Files.

Lily is fascinated by the relationships between plants and insects. ‘I go down to the garden at night to see what moths are pollinating what plant!’ Photo – Amelia Stanwix for The Design Files.

An Artist’s Blissful Garden Wonderland In Daylesford

Artist and garden designer Lily Langham has been tending to her 100 acres of sprawling bushland for the last 13 years. Her artistic sensibilities inform her garden design – resulting in a meandering, intuitive and utterly delightful dreamscape. Expect the unexpected in this place: a rogue pumpkin rolled across the path, a ramshackle caravan, sheds patched together from mismatched sheets of corrugated iron. Our columnist Georgina Reid of The Planthunter sums it up better than we can:

‘It’s rare to see a garden that sits so gently on the landscape. It’s like it’s having a conversation with the soil; it couldn’t be anywhere else but here. It feels true to exactly where it is.’

Revisit the original story here.

The West End garden by Dan Young Landscape Architect. Photo – Christopher F. Jones.

The West End garden by Dan Young Landscape Architect. Photo – Christopher F. Jones.

The West End garden by Dan Young Landscape Architect. Photo – Christopher F. Jones.

A Miraculous Floating Garden + Pool in Brisbane

Now THIS is a pool with a view! A collaboration between Kieron Gait Architects and Dan Young Landscape Design, the renovation to this suburban Brisbane terrace flipped the ‘family home’ stereotype on its head and delivered a pool and garden masterfully integrated with the mountainous landscape beyond. Rough rock, native grasses and even the hint of a tropical canopy make it a standout. The artfully masqueraded car-port draped with a curtain of creepers reminds us of a Bond villain’s lair… in the most sophisticated way possible!

Revisit the original story here.

Jac Semmler’s Frankston garden. Photo – Caitlin Mills for The Design Files.

Jac Semmler’s Frankston garden. Photo – Caitlin Mills for The Design Files.

Jac Semmler’s Frankston garden. Photo – Caitlin Mills for The Design Files.

A Self-Confessed Crazy Plant Lady’s Suburban Garden

Unusually located at the front of her home rather than the rear, this botanical laboratory in Frankston is the place Jac Semmler of The Diggers Club lets her freak flag fly. The self-confessed ‘crazy plant lady’ tests out all her ideas here in her own literal backyard, cultivating a terrain filled with whimsy, texture and randomness. It’s a beloved neighbourhood garden – one tended with emotion, love and sheer curiosity. Just like Jac, this place has SO much personality!

Revisit the original story here.

The Northcote Garden by Sam Cox Landscape Design. Photo – Claire Takacs.

The Northcote Garden by Sam Cox Landscape Design. Photo – Claire Takacs.

TheThe Northcote Garden by Sam Cox Landscape Design. Photo – Claire Takacs.

A Luscious Inner Suburban Garden With An Enormous Ethereal Lagoon (In Northcote!)

The fairytale-style garden by Sam Cox looks like it could be in regional Victoria, not buried in suburban Melbourne! The centrepiece is the swimming hole: a boulder-lined, natural water lagoon that consumes the back half of the garden. Beyond the boundary line, towering natural gums conjure the illusion of bushland which, in the middle of a city, is the best of both worlds!

Revisit the original story here.

0 notes

Text

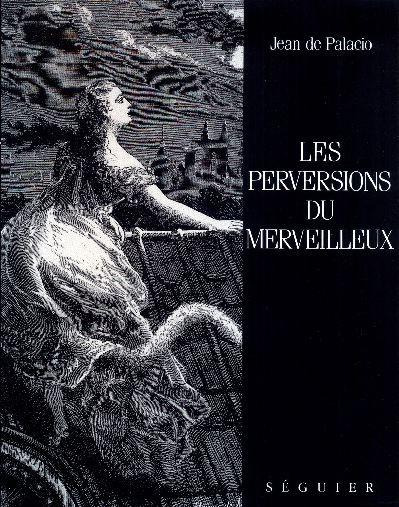

I am so glad I happen to have access to one particular book - it isn't mine but it happens to be part of my mother's collection. "Les perversions du merveilleux", The perversions of the marvelous, by Jean de Palacio.

It's not a book you find in your usual libraries, as it isn't printed anymore and now you get it usually in rare bookshops, or quality second-hand bookstores. Just on the Internet a second hand copy - not even of good quality - is worth at least 30 euros. It is a study, based on roughly five hundred literary fairytales published between 1862 and 1922, on how the "marvelous genre", the "genre merveilleux" - aka the fairytale - mutated and evolved in literature during the second half of the 19th century and the fin-de-siècle.

I often talk of the "great century of fairytales", the "golden age of fairy literature" in France, going from Perrault and madame d'Aulnoy's texts in the early 1690s to the publication of Le Cabinet des Fées in the late 1780s. But it doesn't mean fairytales as a literary genre stopped existing in France. It went on throughout the 19th century - but simply as a minor, overlooked, undignified genre, crushed by the dual tendency towards realism-naturalism (rejecting anything magic and fantasy-like as childish) and towards the fantastical (the "fantastique", opposing itself to the "merveilleux" - fantastique was the "right" way to do supernatural). If the late 17th and full 18th century was the "golden age" of literary fairytales, the 19th century and early 20th was more of a "dark age" - but there was a new boom and resurgence of the literary fairytale, a "Renaissance" by the fin-de-siècle, the two last decades of the 19th century and the pre-World-War 20th century. Of course Palacio here goes a bit further and expands his study all the way to the 1860s and 1920s, but it is still a focus on the "fin-de-siècle fairytale" and its "perversion" of the "marvels" of the genre.

Because what was the fin-de-siècle all about? Finding back a magic, an occultism and an onirism lost by the wave of realistic, social and scientific works ; reconstructing magic and marvels in a modern world while also brutally deconstructing it in front of the recent changes in humanity. Digging up the lost past and confronting it to the present - in comparison, rejection, or embrace. But it was also taking the innocent, the beautiful, the good, the fabulous and wonderful, and making it cynical, bored, depressed, cruel, sadistic - and what better choice of material than these childhood tales and "naive fables" of good fairies and happy princes? Twisting fairytales, but also exacerbating them - because the fin-de-siècle was also focused on the beautiful, the richness, the poetry, and it found a kindly echo and friendly cousin within the abundance, the preciosity and the extravagant luxury of these old fairytales. As such it is no wonder that almost all the artistic movements around the turn of the century - symbolism, decadence, all the way up to surrealism - took a great interest in traditional fairytales.

Anyway - this book talks about what the fin-de-siècle did to fairytales, and it is deeply fascinating. The first chapter is "For a fin-de-siècle merveilleux" and establishes both the "marvelous genre" of this era, and the process of "perverting" said marvelous in three specific ways: sequel-tales (continuing the story after the canonic ending), expanded tales (focusing and expanding on a specific detail of the original tale) and "counterfeit tale" (changing the setting, the gender, the iconic item, the social class, the time era of the original story).

There are two chapters dedicated to iconic character-types of the fairytale. One is the Fairy - "La mort des fées", "The death of fairies" - it explores the whole wave of depicting the fairies as a dying race or an extinct species, as the last remnants and survivors of a long-gone world ; but also the presentation of the fairy reinvented as the "femme fatale", the deadly woman, the lethal seductress ; and the symbolism of the fairy as a "woman of letter" - either a muse for the artist, or a storyteller making fairytales, when she isn't the center of a set of "dangerous wordplays" using language itself against reality. The other chapter is about the Ogre - "L'ogrerie décadente", "The decadent ogrery". It explores how the fin-de-siècle uses the ogre as an allegory or a metaphor rather than an actual character, when the ogre doesn't rather become a good and benevolent character, or helpless victim - it also talks of the focus the era had on Little Thumbling, Petit Poucet, and the transformations of the seven-league boots in light of an era of "speed and progress". But most interestingly, it also focuses highly on the "ogress", who was much more explored than the male ogre, thanks to the era's obsession with monstrous women - it talks of the sexual ogresses more like succubuses, of the greedy ogress-like women focused on eating money rather than flesh, and there is an entire section about the short story by Paul Arène "Les Ogresses".

As for the other chapters, they are all centered around onf of Perrault's fairytales. "La belle au lit dormant", "The beauty in a sleeping bed" - how the identity and nature of the fairies was changed to make them dubious and unclear entities ; how the metaphor of the sleep of a hundred years explored the passing of time or the return to the long-gone past ; as well as how there was a tradition of fin-de-siècle authors openly contestating, criticizing or rejecting Perrault's words and affirmations to tell the "real" story of the Sleeping Beauty.

"Miss Blue-Beard, or from the rehabiliation to the decadence" - the way the authors tried to redeem the character of Bluebeard, while also making alternate versions of the tale with a "rise of the feminine power" - from a greater focus and importance on sister Anne to an exploration of Bluebeard's previous wives and his intimate problems with women, passing by the angle of how power goes from Bluebeard to his surviving wife that takes everything from him.

"The metamorphosis of Cinderella": the great focus and fascination the authors had for the famous glass slipper of Cinderella ; coupled with how it became recurrent to depict the "after-marriage" life of Cinderella, turned into a "house-wife".

And finally "The absence of Griselidis" - dealing with the most often ignored and forgotten part of Perrault's three "verse tales".

#fin de siecle#fin de siecle fairytales#decadent fairytales#fairytale analysis#history of fairytales#literary fairytales#jean de palacio#french fairytales#perrault fairytales

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

H.J. Ford- Slagfid Pursues the Wraith

via

#henry justice ford#h.j.ford#illustration#fairytale illustration#wraith#ghost#fae#naiad#fin de siecle

17 notes

·

View notes