#first time a rouge was ‘scared strait’ for a good while

Text

Danny has became a patron saint of the homeless community in Gotham.

He didn’t mean to, he just really like certain people he has met during his time in the streets.

Little did he know that meant he has been accidentally blessing a lot of nice homeless people.

The people notice.

They whisper of a blue eyed black haired boy. He is as thin as a dead leaf but stronger than a bridge and seen across the entire city.

He doesn’t carry much on him yet always seemed to be able to pull out needed necessities.

He’s sweet in a way that few people are in the shadows they lived in and cared for the people who were kind back.

His tattered closes dance in an invisible wind and never complains of the cold.

Be kind to the boy, and the world will be kind to you.

He cares for his people and doesn’t care for those who mistreat them.

#writing prompt#dp x dc#danny fenton#danny phantom au#danny phantom#dc x dp#a rogue tried to kidnap some homeless people while Danny was near by#first time a rouge was ‘scared strait’ for a good while#6 months without them terrorizing the city#they never go after the homeless again

4K notes

·

View notes

Photo

He Starved, Suffered and Nearly Died, but Never Lost Hope

Genocide survivor went on to be a Cambodian minister, and seeks now to inspire the young

The Straits Times 22 Mar 2020 Wong Kim Hoh Senior Writer [email protected]

PHOTOS: KELLY HUI, VENG SEREYVUTH

Veng Sereyvuth has a passionate belief.

“You are born with the power to dream, to make choices, to craft your destiny. No one except you can steal that from you,” he says.

Before you dismiss that as a platitude, consider who he is and what he has gone through.

The 61-year-old survived the Cambodian genocide during which more than two million people died under the Khmer Rouge, which was in power between 1975 and 1979, led by Marxist leader Pol Pot.

His life has been both a melodrama and a potboiler: a village boy who became a cyclo driver, a smuggler, a prisoner, a refugee, a political science graduate and, eventually, a politician who served as Cambodia’s minister for tourism and minister for culture.

Along the way, he starved, suffered and stared death in the face on several occasions. But through it all, he never gave up hope.

Today, he is a businessman and educationist; he has built hotels and other properties and is chairman of the board of trustees at the Pannasastra University of Cambodia, a private university in Phnom Penh which provides an English-based education.

Mr Veng does not have the statesman-like gravitas one expects of someone who has spent more than two decades as a senior minister.

Dressed in jeans and a white shirt with a cotton krama (a traditional Cambodian scarf) around his neck, he radiates approachability and joviality.

He was in Singapore recently to put the finishing touches to No One Born Poor: Prisoner, Politician, Pioneer, a book about his life published by Write Editions and available at major bookstores in June.

Calling the book a tribute to the country he loves, he hopes that his story of “challenging life, confronting the unknown and embracing its ups and downs” will give hope to many people, especially the young.

He was born the second of six children in the remote village of Prey Deoum Thieng in the Cambodian province of Prey Veng.

His father was a teacher and his mother ran a provision shop. The couple later separated, and Mr Veng and his siblings were raised by his mother, whom he describes as a “commander-in-chief” and the strongest person he knows.

Life in the village was idyllic. He loved going to school, spurred on by his mother who fervently believes that education is not just the ticket to a better life, but also makes one a better person.

But civil strife soon rocked the country when a military coup overthrew head of state Prince Norodom Sihanouk in 1970.

The Khmer Rouge started becoming more powerful; they were communist revolutionaries who saw religion, education and freedom as dangerous.

Realising that life in their village was getting untenable, Mr Veng’s mother decided to uproot her brood to Phnom Penh in 1972.

She decided to do it first with Mr Veng, who was then just 12, before coming back for her other children.

Because the Khmer Rouge killed villagers who tried to flee for the city, mother and son escaped through rice fields in the dark of the night before taking a boat across the Mekong to get to Phnom Penh.

“It was a real ordeal, a life-anddeath situation. I saw dead bodies, and heads on bamboo poles,” recalls the amiable man whose other siblings arrived in the city several weeks later.

With no income from a provision shop to feed her brood, his mother started selling noodles.

Mr Veng continued his education at a French Catholic school, but sold bread to office workers before classes began and became a cyclo – a three-wheeled taxi – driver after school ended.

Life was tough but as he writes in his book: “I didn’t see myself as a cyclo driver, as it was not my final mission in life. It could not be. It must not be. The cyclo was a tool to meet two needs: to fill my stomach and pay for my education. Nothing more, nothing less.”

In 1975, the Khmer Rouge won the civil war and captured Phnom Penh. They emptied the cities, forcing millions of Cambodians, including Mr Veng’s family, back to the countryside.

Not long after they began their trek to a village in Prey Veng, Mr Veng’s mother told him to go back to their Phnom Penh home to get a 20kg pot of preserved fish because it would provide sustenance for their month-long journey.

But the then 15-year-old was stopped by soldiers who ordered him to turn back. When he moved forward, a soldier pointed a gun at him. Mr Veng begged for permission to get his pot of fish. To his surprise, the soldier let him through.

The episode taught him one thing: You need courage and conviction for everything you do in life.

“For me, it means protecting the preserved fish, at all costs, for my family.”

The Khmer Rouge were brutal in their quest to set up an agrarian utopia, torturing and killing intellectuals and anyone else they considered a threat to communism.

Mr Veng and his brothers escaped death, but, like millions of their countrymen, were sent to slave at labour camps.

The Khmer Rouge lost their grip on power in 1979 when Vietnamese forces took control of Phnom Penh.

It was not just another chapter in the country’s history but also in his life. To help his family survive, he became a smuggler, sneaking to the Thai border to buy cartons of cigarettes – apparently more valuable than money then – which he would trade or sell.

It nearly cost him his life on several occasions. Once, he was denied entry at a checkpoint by soldiers who wanted his cigarettes.

To get across, he made eye contact with people on the other side of the metal barrier and told them in a low voice to leave a gap for him to pass through when the barrier was lifted.

He made a dash for it on his bicycle, pedalling furiously as the sound of bullets reverberated behind him. By the time he stopped, his feet were bloody from the desperate pedalling.

Asked if he has ever thought about death, he says with a laugh: “When you live in a structured and orderly society, you think about things like that. But when you live in hell...”

He continues: “I had no choice. I just did what I needed to do to feed the family. You get out of a situation first and get scared later. You deal with death only when it comes.”

His family cried each time he went away because they were worried he might not come home.

“Every trip was three weeks or a month long. Things could happen: sometimes you could not get the goods, sometimes there were shootings, sometimes you just could not get back i nto Cambodia. I had stayed in forests where I just ate what I had and what I could find.”

Hunger was a constant companion. “You can check with your doctor friends but when you’re really hungry, your stomach feels like it’s being cut into pieces with a knife,” says Mr Veng, who was once so weak from hunger he had to be propped into a sitting position at mealtimes with a rope tied to the ceiling.

The year 1979 also marked one of the lowest periods in his life.

Soldiers stopped him on his bicycle while he was riding home to Prey Veng with a sack of 200 bicycle spokes he hoped to sell. They accused him of sending the spokes to the Khmer Rouge and threw him into a dark prison for a month.

Then, one day, he was taken blindfolded to the Mekong. He felt a gun muzzle on his left cheek, and heard the weapon being cocked as he was asked if he was part of the Khmer Rouge.

He just blurted: “I’m a student.” That split second of telling the truth, he says, spared him from getting his head blown off.

The era of the Khmer Rouge might have been over but fear and uncertainty still blanketed the country.

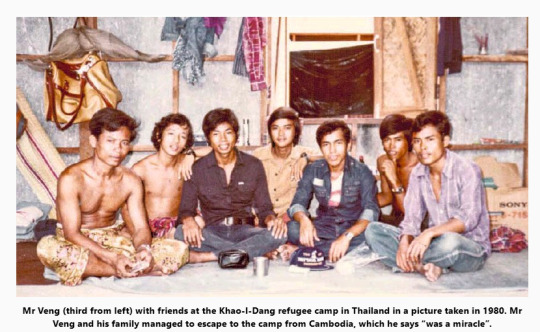

Overwhelmed by the hopelessness, he and his family decided to “turn this game of life around” and take the big risk of escaping to the Khao-I-Dang refugee camp – set up in late 1979 and run by the Thai Interior Ministry and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees – across the Thai border.

They split into two groups. He and two of his sisters set out first. The plan was to reunite with his mother and other siblings at the refugee camp.

Thousands had died undertaking the weeks-long journey which was fraught with many dangers, from landmines to trigger-happy soldiers. Mr Veng and his two sisters moved mostly at night to avoid getting caught.

They made it, and so did the rest of the family.

“It was a miracle. The border stretched for hundreds of kilometres but we managed to find one another,” he says.

They stayed in the camp for one year.

“It was a completely different life. There were no guns and no fear. You mingled with other people and walked about freely in the camp. You could sleep and wake up, a free man.”

Nearly a year later, the family were told that they would be going to New Zealand.

“It was surreal, we were speechless,” recalls Mr Veng, who landed in Auckland with his family in September 1980.

There, he worked at several places including a printing firm and an ice-cream shop while attending English, maths, economics and accounting classes at a polytechnic.

In 1984, he got accepted into the University of Victoria on a special admissions scheme. It was hard because he had not mastered the English language, but his will bulldozed through the obstacles, and he graduated with a degree in political science in 1987.

He never forgot Cambodia though. For a year, he was haunted by nightmares of what he had lived through. To exorcise his demons, he shared his story openly with his lecturers and classmates.

He also joined the secretariat of the Khmer Association in New Zealand to help new refugees adapt to life in the country. The association also built the first Cambodian pagoda in the country.

The urge to return to help rebuild his homeland was “instinctive”.

“It’s my country. It’s where I came from and I wanted to give back. Gratitude is my attitude,” says Mr Veng, who spent more than a year working as a taxi driver – “you can make a lot of money” – before heading for Bangkok in 1989.

He could not enter Cambodia because the country was still in political turmoil. In Bangkok, he volunteered with The National United Front for an Independent Neutral and Cooperative Cambodia and worked with refugees along the Thai border.

In 1993, he took part in Cambodia’s general election and became a member of Parliament as well as minister for tourism, a post he held until 2004.

“It was one of my top achievements,” says Mr Veng, who was also minister to the council of ministers and minister for culture.

Among other things, he chaired an initiative to step up the flow of tourist dollars in the region, resulting in the signing of the Asean Tourism Agreement in Cambodia in 2002.

Except for two of his sisters, Mr Veng’s mother and other siblings have also returned to live in Cambodia. He has a son, 22, who is studying public policy at the University of Victoria; his former wife died in an accident several years ago.

The congenial man, who holds both Cambodian and New Zealand citizenships, went into business after leaving politics in 2013 but focuses a lot of his attention on education for young Cambodians.

Mr Veng, who often gives talks to inspire others, says his philosophy in life is simple.

“I believe that on the canvas of humanity, we are to paint goodness: the able extending goodness to those without hope, the distressed and the needy.”

Chairman of the Board: H.E. Veng Sereyvuth held various ministerial positions in the Royal Government of Cambodia since 1993, including co-minister of Council of Ministers, Senior Minister of Tourism, and Senior Minister of Art and Culture. H.E. Veng Sereyvuth received a Business Administration's degree from Victoria University Wellington, New Zealand;

0 notes