#flockaveli

Text

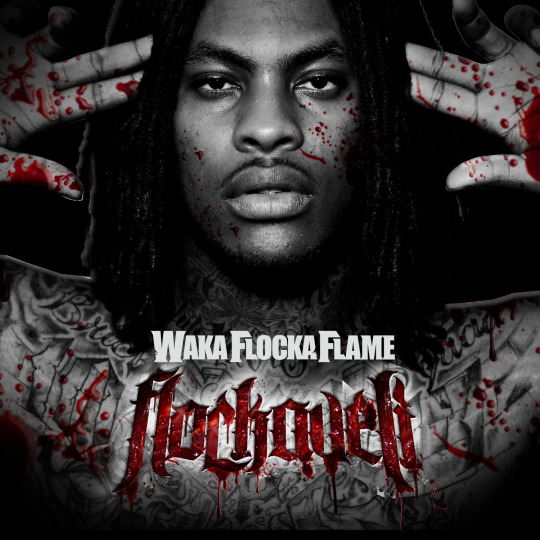

Waka Flocka Flame – Flockaveli (2010)

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Rap & Hip-Hop#Rap#Hip-Hop#Hip Hop#hiphop#music#2010s#10s#waka flocka flame#no hands#roscoe dash#wale#flockaveli#gif

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Waka Flocka Flame - " For My Dawgs "

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#flockaveli#waka flocka flame#for my dawgs#1millennia#onemillennia#millenniamag#millenniasongoftheday#millenniamagazine#one millennia#millennia#song of the day

0 notes

Text

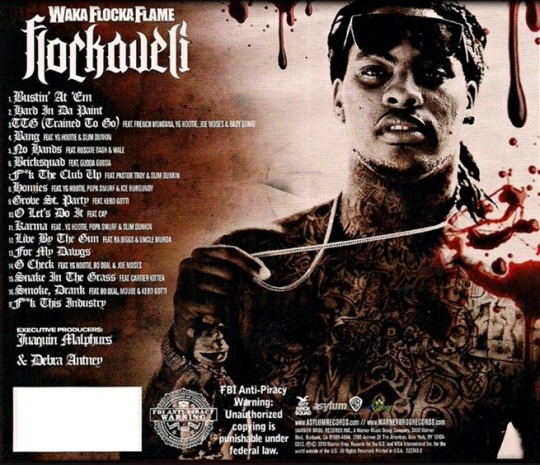

Tracklist:

Bustin' At 'Em • Hard In Da Paint • TTG (Trained To Go) • Bang • No Hands • Bricksquad • F**k The Club Up • Homies • Grove St. Party • O Let's Do It • Karma • Live By The Gun • For My Dawgs • G Check • Snake In The Grass • Smoke, Drank • F**k This Industry

Spotify ♪ YouTube

#hyltta-polls#polls#artist: waka flocka flame#language: english#decade: 2010s#Trap#Dirty South#Gangsta Rap#Southern Hip Hop#Crunk#Chicago Drill

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

flockaveli is so good. when Karma is followed up by Live by the Gun i feel so alive

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Album of the decade: Kendrick Lamar’s ‘good kid, m.A.A.d city’

Like ‘The Autobiography of Malcolm X,’ the 2012 opus overflows with black rage, fear of abandonment, and a sobering understanding of death and rebirth

Like ‘The Autobiography of Malcolm X,’ the 2012 opus overflows with black rage, fear of abandonment, and a sobering understanding of death and rebirth

True, Kendrick Lamar’s 2012 opus good kid, m.A.A.d city is the longest charting hip-hop studio album in history. Yes, it was the 13-time Grammy winner’s major label debut. But good kid is the album of the decade because it is The Autobiography of Malcolm Xfor our time, overflowing with black rage, hopelessness, fear of abandonment, and a sobering understanding (and sometimes reckless disregard) of death and rebirth.

Aftermath Entertainment/Interscope Records

And as with Malcolm X, a name change is an important signifier. “I learned, when I look in the mirror and tell my story, that I should be myself and not peep whatever everybody is doing … If I’m gonna tell a real story, I’m gonna start with my name,” Lamar, who had previously performed as K-Dot, told Vultureon the eve of the album’s release.

good kid’s cover art shows baby Kendrick sitting on a family member’s lap. The album itself begins with a teenage Lamar chasing after a girl named Sherane and ends with him witnessing the death of a friend and undergoing a spiritual awakening. He rockets through a galaxy of themes: love, lust, loyalty, fear, anger, divinity, spirituality, toxic masculinity, gang politics, gun violence, racial profiling, teenage innocence, police brutality, survivor’s remorse, hope, self-awareness and mortality.

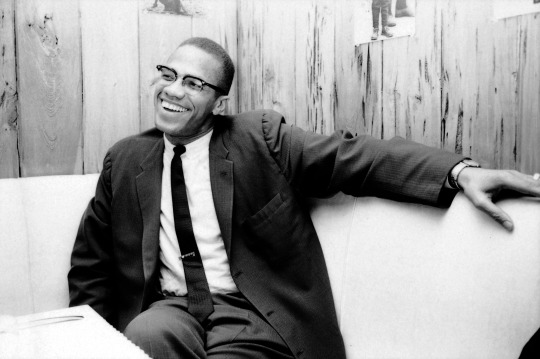

American civil rights leader Malcolm X relaxes on a couch on March 1964.

Photo by Truman Moore/The LIFE Images Collection via Getty Images/Getty Images

Still, there is plenty of competition for the mythical title of album of the decade. Beyoncé’s Lemonade or her 2013 industry-shifting, self-titled album, Rihanna’s ANTI,Kanye West’s My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, Frank Ocean’s Channel Orange or Blonde, Adele’s 21, Solange’s A Seat at the Table, Freddie Gibbs and Madlib’s Bandana, Anderson .Paak’s Malibu, Jay-Z’s 4:44, David Bowie’s Blackstar, Killer Mike’s R.A.P. Music, Cardi B’s Invasion of Privacy, Noname’s Room 25, Jamie xx’s In Colour, Tame Impala’s Lonerism, SZA’s Ctrl, D’Angelo and The Vanguard’s Black Messiah, Travis Scott’s Astroworld, Miguel’s Kaleidoscope Dream,Vince Staples’ Summertime ’06, Waka Flocka’s Flockaveli, and a host of others, have stated their cases.

While good kid’s importance is widely recognized, its place in end-of-the-decade rankings varies widely. Rolling Stone puts it at No. 66! Vice settled at No. 28. Pitchfork gave it No. 18, claiming every autobiographical rap album in its wake “walks in part in its footsteps.” XXL didn’t rank its top 50 projects but noted good kid was “about as instant a classic as you can get.” Billboard ranked it as the decade’s 15th best project and NME and the Associated Press bestowed it No. 5 honors.

For many, including Lamar himself, his third album, 2015’s To Pimp a Butterfly, takes precedence. It boasts what many believe is the most important song of the decade in “Alright.” Esquire and Independent both made this testament to the anger and isolation black America felt in the wake of the deaths of people such as Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland, Mike Brown, Eric Garner and Jordan Davis, as their top album of the decade. Lamar himself told Billboard in 2016 that good kid was great work, but not his best. “To Pimp a Butterfly is great,” he said. And that he would’ve been upset by 2014’s notorious zero-for-seven Grammy’s snub “if I knew that was my best work, if I had nothing new to offer.”

youtube

The truth is multidimensional. Starting with 2011’s Section.80 and most recently with 2018’s Black Panther soundtrack, for which he served as executive producer, Lamar delivered a catalog of albums over the last 10 years that makes him one of music’s most important figures. His Pulitzer Prize for 2017’s DAMN. made him the first non-classical or jazz artist to earn the prestigious distinction. Every project he’s put his name on in this decade has shifted the culture.

So does Butterfly or even DAMN. check off more of the best-of-the-decade criteria than its predecessor?

“good kid, m.A.A.d city definitely set the table [for Kendrick’s decade]. And I’m a jazz guy so I’m always going to ride for To Pimp a Butterfly,” said Marcus Moore whose biography, The Butterfly Effect: How Kendrick Lamar Ignited the Soul of Black America, is aiming for a 2020 release. “But without [good kid], there’s no way he could have made To Pimp a Butterfly or DAMN.”

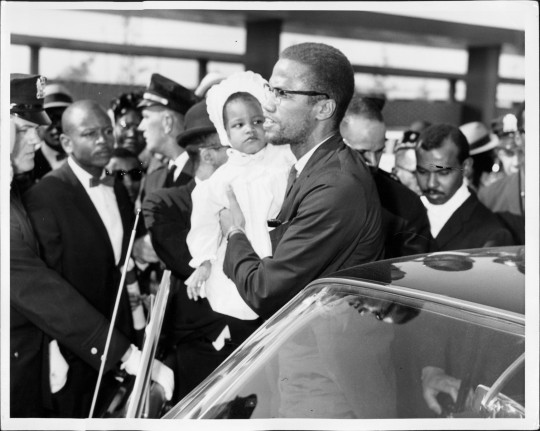

Malcolm X and his daughter Ilyasah leave John F. Kennedy International Airport for the Hotel Theresa in Harlem on Jan. 1, 1964.

Photo by William N. Jacobellis/New York Post Archives /(c) NYP Holdings, Inc. via Getty Images

By contrast, Lamar’s parents, both of whom are featured on good kid, are vital figures in his life story. They sought to both teach their son about street life in Compton, California, and also protect him from it. “They wanted to keep me innocent,” he told Rolling Stone. “I love them for that.”

Lamar read Malcolm X’s autobiography as a teenager, and in a 2017 interview with Vice, he spoke of the late civil rights icon in a near religious manner.

“His ideas rooted my approach to music,” Lamar said. “That was the first idea that inspired how I was going to approach my music. From the simple idea of wanting to better myself by being in this mindstate, [the] same way Malcolm was.”

X bounced around Michigan, Boston and Harlem before his incarceration. Lamar and turn-of-the-century Compton were joined at the hip, as evidenced by the bevy of local landmarks he name-drops: the intersection of El Segundo Boulevard and Central Avenue, Alameda Street, Gonzales Park, Lueders Park, Bullis Street, Food 4 Less and Church’s Chicken. Growing up in poverty for Lamar, and moving from the streets to foster homes for Malcolm X, meant resources were scarce. Hopelessness and helplessness were inevitable realities. Whether it was the Midwest and Northeast before the civil rights movement or Compton after the L.A. riots, both were conditioned to being repeatedly degraded for merely existing. The trauma was constant, as were the coping mechanisms.

“I had gotten to the point where I was walking on my own coffin,” Malcolm X wrote, reflecting on his hustling days when he was known on the street as Detroit Red. “Drugs helped push the thought [of getting caught] to the back of my mind. They were the center of my life.” “For the record, I recognize that I’m easily prey/ I got ate alive yesterday,” Lamar wrote on the title track “Good Kid.” “I got animosity building, it’s probably big as a building/ Me jumping off of the roof is me just playing it safe.”

youtube

Malcolm X and Lamar both understood that the way society is set up, success was never meant for them. Two flawed protagonists in their own stories, they felt backed into corners and responded with desperation and anger. Malcolm X talked of cocaine making decisions for him, constantly carrying a gun and fantasizing about committing violence on a black cop who loathed him.

By high school, when good kid takes place, Lamar was already running with a crowd that committed home invasions and eluded the police. They got him drunk, after being beat up by local gangbangers, and high, after breaking and entering (“flocking”). “Cocaine laced in marijuana/ And they wonder why I rarely smoke now,” he recounts on “m.A.A.d city.” “Imagine if your first blunt had you foaming at the mouth.” Like Malcolm X before his conversion to the Nation of Islam, death stayed just out of arm’s reach for Lamar. His mom would find bloody hospital gowns of friends who got shot at their house — or Lamar would cry in the front yard after surviving a shooting.

good kid’s “The Art of Peer Pressure” shares a demonic soul with Malcolm X’s recounting of his days in Boston. Malcolm X wrote about feeling unrecognizable as Detroit Red. Yet, there he was, running the streets of Boston with his best friend, Shorty.

In “Peer Pressure,” Lamar and his friends L-Boog, Yan Yan and YG Lucky had just finished playing basketball. Now they were chain-smoking blunts in a Toyota, hollering at girls and pressing guys they saw wearing the wrong gang-affiliated covers. Red and blue had, from a ‘hood politics perspective and the police, become colors that signaled colors long representing factions counterintuitive to Kendrick’s survival. “I never was a gangbanger, I mean/ I was never stranger to the fonk neither,” Lamar raps. The group of teenagers commit a home robbery only barely escape police. Lamar knows he barely escaped. The song’s most important bar, though, is “One day it’s gon’ burn you out, but I’m with the homies right now.” In that moment, breaking the law doesn’t matter. Nor does the possibility of getting killed by gangbangers.

Kendrick Lamar performs during the third day of Lollapalooza Buenos Aires 2019 at Hipodromo de San Isidro on March 31 in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Photo by Santiago Bluguermann/Getty Images

“The really interesting thing is how K-Dot and Detroit Red [wrestle] with black rage. Rage about feelings of nothingness in their present or future. Rage about feeling their lives are meaningless. And having to fight to matter and fight to survive,” said Justin S. Hopkins, a clinical psychologist in Washington. “They both turn to drugs to deal with this unbearable pain. And muster a sense of agency and control over what feels impossible. By so doing, [both] cope with constant fear and annihilation.”

Both good kid and The Autobiography of Malcolm X highlight experiences with pain. And how exhausting it is when one feels that pain doesn’t seem to matter to society at large. “Am I worth it? Did I put enough work in?” Lamar asks on “Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst.” The record is an epic multidimensional confessional that finds him rapping from the perspective a slain friend’s brother (who eventually gets murdered himself), the sister of a young woman condemning Lamar for telling her sister’s story through song (she, too, dies after years of working the streets as a prostitute) and finally himself dealing with the burden of survivor’s remorse. You learn not to care about yourself when the world doesn’t.

Turning points define both works and the lives they chronicle. For Malcolm X, it took being sentenced to 10 years in prison before a spiritual awakening set the course of his life on a completely different trajectory. By the time he reemerged into society in 1952, Detroit Red was long dead, and the world would soon come to know, loathe, love and fear Malcolm X, who would help propel America into a decade of racial reckoning.

Growing up, Lamar, had seen a “light skin n—- with his brains blown out,” as he noted on “m.A.A.d city,” and his Uncle Tony was shot twice in the head outside of Louis Burgers in Compton, which he depicted on “Money Trees.” The true pain of which could never be resolved any sort of monetary success or commercial acceptance. But watching his friend Dave die after a shootout with guys who had jumped Lamar earlier in the day set in motion his own reality check. While he is walking around in a haze of anger and grief and carrying a gun, a neighbor, voiced by none other than Maya Angelou, persuaded him and his surviving friends to let God into their lives and leads them in reciting the Sinner’s Prayer. The conversation is poignantly similar to one she had with Tupac Shakur on the set of Poetic Justice 20 years earlier. “Now everybody serenade the new faith of Kendrick Lamar/ This is King Kendrick Lamar,” he booms on the album’s victory lap, the appropriately titled “Compton” featuring Dr. Dre.

Rapper Kendrick Lamar attends a ceremony honoring him with the Keys to the City of Compton, in Compton, California, on Feb. 13, 2016.

VALERIE MACON/AFP via Getty Images

“Both of them go to the depths of their trauma and learn how to acknowledge the deep sense of loss and vulnerability that they feel,” said Hopkins. “They start building a foundation for their own self-worth despite all the things that were attacking it all along. It’s a beautiful and triumphant story.”

Their stories spoke of resilience, acceptance and bravery from the perspectives of young black men who had seen hell and found some peace before they got to heaven. Even if, in Malcolm X’s case, he was — as he predicted in the final pages of his book — assassinated before he could hold a copy of his life’s journey in his own hands. The results resonated deeply in the generations they spoke for. For Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, who first read The Autobiography of Malcolm Xin 1968, the book became gospel for him.

“His story couldn’t have been more different than mine — street hustler and pimp who goes to prison, converts to Islam, emerges as an enlightened political leader — but I felt as if every insult he suffered and every insight he discovered were mine,” the NBA’s all-time leading scorer wrote in his 2017 memoirCoach Wooden and Me. “He put into words what was in my heart; he clearly articulated what I had only vaguely expressed.”

Four-time NBA All Star and Compton native DeMar DeRozan expresses the same sentiments when discussing the impact of good kid, m.A.A.d city. “A lot of people who come from a lot of trials and tribulations can’t vocalize the traumas they’ve been through,” he said. “Listening to that album, it’s therapeutic. You’re hearing things you went through. Things you seen, things you may feel but you don’t know how to express in words. But Kendrick did.”

Civil rights activist Malcolm X poses for a portrait on Feb. 16, 1965, in Rochester, New York.

Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Malcolm X’s life story was one of transition. From Malcolm Little to Detroit Red to “Satan” (as fellow inmates dubbed him when he’d curse God and the Bible) to Malcolm X to El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. And though his ideology and the targets of his rhetoric changed over the last 13 years of his life, Malcolm X had come to know who he was. He was a black man his family could be proud of, who articulated a philosophy of how the black man should act and what he should demand of America. In the final chapter of his autobiography, titled 1965, he said, “I have given … so much of whatever time I have because I feel, and I hope, that if I honestly and fully tell my life’s account, read objectively it might prove to be a testimony of some social value.”

Lamar, now 32, engaged and the father of a baby girl, is nearly a lifetime removed from the 17-year-old who lived, bled and cried the story that eventually became good kid, m.A.A.d city — it, too, a testimony of social value. And near the end of good kid, it’s Kendrick’s mother, Paula Duckworth, who delivers the underlying message behind the album on “Real,” and one Malcolm’s legacy would carry longer than his physical ever would. “Come back a man. Tell your story to these black and brown kids in Compton. Let them know you was just like them, but you still rose from that dark place of violence, becoming a positive person,” she said. “But when you do make it, give back with your words of encouragement, and that’s the best way to give back.”

Unlike Malcolm X, Lamar is far less outwardly fierce — away from a microphone, at least. He rarely conducts interviews and therefore the evolution of his philosophy must be read through his art. At the root of both To Pimp a Butterfly and DAMN. was the value of black existence — the hope, the despair, the odiousness, the fury, the pride and everything in between. And both albums build from the process of self-enlightenment introduced on its 2012 sibling.

“good kid, m.A.A.d city represents that first level of self-awareness where you’re just starting to reparent yourself, revisit your inner child and have that first access point of self-discovery and self-awareness,” said wellness advocate and author Devi Brown, who has interviewed the Grammy-winning MC multiple times throughout his career. Malcolm and Kendrick represent, in her words, the archetype of a platform that converted pain, confusion and violence beyond their emotional and moral jurisdictions. Yet, both used that not only for radical change in themselves, but what they shared with the world. “You realize how much you have to unlearn. How much of life is dictated by things out of your control.”

“[Kendrick] puts his life in his music. Everything. The good, the bad and the questionable. That’s why it resonates with so many people, because he’s giving listeners something positive to aspire to. Yet, he doesn’t shy away from the negativity that almost took him under,” said Moore, the biographer. “Malcolm earned that trust by speaking truth to power, and by doing so in searing fashion. Though he masks certain things in poetic fashion, Kendrick’s work is remarkably honest and hits the same way. No matter when you play it.”

Lamar’s death is not required for good kid to be the modern-day version of The Autobiography. The album, like the book, is an evolving piece of art. Birthed in the same struggle for purpose and cultivated through a series of environmental roadblocks and self-induced insecurities. Both produce different experiences as they age, but more so as we age. Certain lessons are only unlocked through putting one foot in front of the other.

Like Malcolm X, only the mistakes have been Kendrick’s. Thankfully he’s still here to tell his story.

Justin Tinsley is a senior culture writer for Andscape. He firmly believes “Cash Money Records takin’ ova for da ’99 and da 2000” is the single most impactful statement of his generation.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

i dont really have a title i just wanna talk ab this album

this album and flockaveli are both albums that people who are into trap know are influential, however do not generally get the recognition they deserve. not only that, but the album is just really good. this recently get a spot in my rotation and I dont see it leaving any time soon.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Juaquin James Malphurs (born May 31, 1986) known as Waka Flocka Flame, is a rapper. Signing to 1017 Brick Squad and Warner Bros. Records, he became a mainstream artist with the release of his singles “O Let’s Do It”, “Hard in da Paint”, and “No Hands”, with the latter peaking at #13 on the US Billboard Hot 100. His debut studio album Flockaveli was released. His second studio album Triple F Life: Friends, Fans & Family was released and was preceded by the lead single “Round of Applause”.

He came to fame with his breakthrough single “O Let’s Do It”, which peaked at #62 on the US Billboard Hot 100. He is a member of 1017 Brick Squad with Gucci Mane, OJ Da Juiceman, Frenchie, and Wooh Da Kid. His debut album, Flockaveli, was released. The album debuted at number six on the US Billboard 200. The album was inspired by Tupac Shakur, whose final stage name and pseudonym before his death was Makaveli. He was named the eighth hottest MC by MTV. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes

Text

Every time i wake up i have 2 play flockaveli 2 get ready for the day or else im in a bad mood

#but i CANNOT listen 2 music to sleep#i been waiting 2 get thru this week since it STARTED!!!!!!!#i wanna see him.....i cant wait til we get 2 sleep in together.......mornin head dont play with me please#999

0 notes

Text

Waka Flaka Net Worth

Waka Flaka Net Worth

American rapper Juaquin James Malphurs, well known by his stage name Waka Flocka Flame, comes from the region of South Jamaica. After the release of his songs “O Let’s Do It,” “Hard in da Paint,” and “No Hands,” he established himself as a prominent artist in the industry.

2010 saw the release of his first full-length studio album, titled “Flockaveli.” The year 2012 saw the release of his second…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Jay z 444 album zip hiphopstoner

In early 2013, he signed with Gucci Mane’s 1017 Records, where later that year he released his label debut mixtape, 1017 Thug, to critical praise. Known for his eccentric vocal style and fashion, Thugger initially released a series of independent mixtapes beginning in 2011 with I Came from Nothing.

Young Thug is one of the most influential figures of his generation, with his music impacting the modern sound of trap music. Of course, this is not really a trap album, but we daresay it helped form the genre (no Young Thug without Lil Wayne) and therefore merits inclusion on this list. Tha Carter II is Lil Wayne’s best and most consistent album, but Tha Carter III is not far behind. Carter”, and “Let The Beat Build” make up for the weaknesses. The album is frontloaded, with a much weaker back half – but classic Lil Wayne bangers such as “A Milli”, “Dr. Tha Carter III is one of the major albums of the aughts, one we didn’t much care for when it dropped but which has undeniably grown on us. Especially among his early Cash Money work (either solo or as part of the Hot Boys) and his 2000s mixtapes plenty of solid music can be found, not to mention Tha Carter II, which is his absolute best album. For this reason, and because he released a lot of terrible music himself (in the 2010s, mostly), we have often dismissed Lil Wayne. Even if he is not exactly a trap-rapper himself, it’s not a stretch to say he helped father the mumble trap genre, spawning an army of face-tatted Lil Clones who have been flooding the mainstream with an endless stream of generic braindead music. Lil Wayne is an icon, one of the most influential rappers of the last two decades. Tha Carter III is Lil Wayne’s sixth studio album, it follows Tha Carter II as well as a long string of mixtape releases and guest appearances on other Hip Hop and R&B artists’ records, helping to maximize Lil Wayne’s exposure in the mainstream, which was further aided by features appearances on this album from high-profile artists such as Jay-Z, T-Pain, Busta Rhymes, and Kanye West, among others. What do YOU think of this selection? Is this list missing essential trap albums? Some albums that shouldn’t be on this list? Drop your opinions in the comments! So, let’s get into it – this is our list with what we consider to be 25 of the best trap albums ever released – not ranked, but presented in order of the years they were released. So even if some of the pre-2010 albums on this list are not really categorizable as trap albums, we included them anyway – either because they are Southern classics that influenced the direction trap would go, or simply because we feel these are the best albums of artists who often get categorized as trap-artists (even if their best albums arguably are not strictly trap-music). Some people argue the modern trap sound really broke into the mainstream with Waka Flocka Flame’s influential Flockaveli album in 2010, and everything released before 2010 influenced that sound but is not necessarily trap as we would define it now. But making an effort to enjoy trap for what it is and trying not to condemn it for what it is not, we opened our minds and revisited a bunch of albums roughly categorizable as trap-music, albums we DID actually enjoy to an extent or even a lot.

We get called out a lot lately for having an anti-trap bias because our well-read The Best 250 Hip Hop Albums Of All Time list includes no trap albums – and we stand by our choices made there. And although often catchy enough, in our opinion meaningful content is not something to turn to trap for. For us lyricism counts, and we feel lyricism is more than simply a series of enjoyable flows and cadences – content matters too. Regular visitors of the HHGA site will know we are NOT the biggest fans of the trap subgenre of Hip Hop.

0 notes

Text

#waka flocka flame#roscoe dash#wale#no hands#no hands (feat. roscoe dash & wale)#flockaveli#waka flocka flame no hands#waka flocka flame flockaveli#waka flocka flame lyrics#no hands lyrics#flockaveli lyrics#waka flocka#quotes#handwriting#songs#lyrics#music#hip hop#hip hop music

1 note

·

View note