#foundSF

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The plastic knives are out.

📍 The Mission District, San Francisco, CA

~ Objects are never touched, rearranged, or otherwise tampered with in any manner whatsoever, ever.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

45 years ago today

A photo that is almost exclusively associated with an album

The image was taken by Judith Carlson and created for the San Francisco Examiner. It was recorded during the so-called "White Night Riots" on May 21, 1979

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

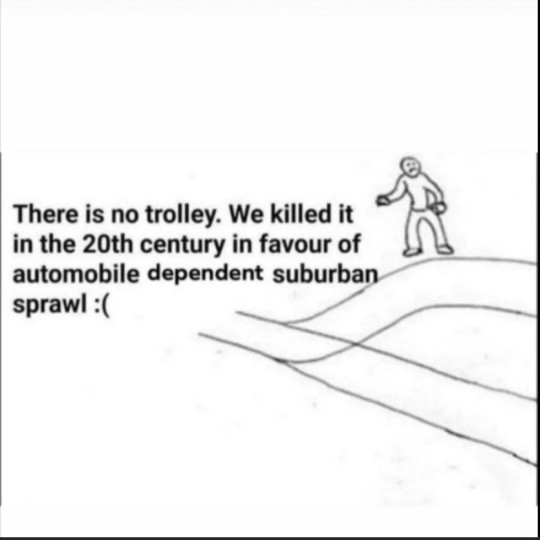

Thinking of the Key Route streetcar system in Berkeley and Oakland California, which started transbay commuter trains to San Francisco in 1938. And then a company that turned out to be a holding company for General Motors bought out the system and decommissioned it, as it did to most of the rail systems in California. Just in case anyone's tempted to think there was anything about US American Individualism that inevitably led to dependence on cars: it's at least partly because rail infrastructure was systematically destroyed by an industry that found it threatening.

#there is no trolley#we are all playing frogger#and trying to navigate on foot across an interstate#good luck to us#public transit#car culture

149K notes

·

View notes

Photo

(via Donaldina Cameron House - FoundSF) Donaldina Cameron House - a Christian mission established by Donaldina Cameron (b. NZ, 1869) for the emancipation of trafficked Chinese women. The goal was to liberate them from miserable lives of forced prostitution, but it came with a pricetag. Women were expected to conform to Western ways and to convert to Christianity. While some women converted, and called Donaldina ‘Lo Ma’ (mother in Cantonese), others ran away. It still exists today as a centre for social welfare projects in the SF Chinese community. The building is said to be haunted!

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

A fantastic article on the architectural legacy of San Francisco’s 1915 Pan-Pacific International Exposition.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

embarcadero freeway park under construction, san francisco, 1975.

also see: the san francisco freeway revolts, on foundsf.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Modern San Francisco is very much a legacy of Feinstein's misrule as Mayor.

"...In addition to increasing homelessness, Mayor Feinstein’s agenda permanently raised rents not just in San Francisco but across California.

San Francisco’s process of extreme gentrification and displacement began in the late 1970’s. Feinstein’s ascension to the mayor’s office brought a landlord and strong ally of Big Real Estate into power at the worst possible time. Feinstein used her power to protect big and small landlords alike; protecting tenants was not part of her world view."

Senate Republicans and Sen. Joe Manchin voted to roll back an EPA regulation on truck pollution.

The legislation, which Biden has vowed to veto, passed 50-49.

Democratic Rep. Ro Khanna argued it wouldn't have passed had Sen. Dianne Feinstein been present.

In a 51-49 split Senate, every vote matters.

Senate Republicans and Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin took advantage of Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein's ongoing medical leave to roll back a significant environmental regulation on Wednesday.

819 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(via Black Panthers - FoundSF) A little research on the Black Panther Party for a Documenraty on the Filmore district in San Francisco and how it’s changed over decades.

0 notes

Text

The Golden Dragon Massacre

San Francisco Chinatown is a fun place to be - with its an annual Chinese new year parade, delicious dim sum, and a rich cultural history. It’s the oldest Chinatown in the US! In its many years of existence, SF Chinatown has inevitably had some dark moments in its history.

According to Bob Calhoun of SF Weekly, two main gangs were involved with the massacre in 1970s Chinatown: The Wah Ching and The Joe Boys. There was another gang, the Hop Sing Tong, that involved themselves with the Wah Ching.

At 2:40am, the Joe Boys arrived at a restaurant called The Golden Dragon, a restaurant which Calhoun describes as a popular late-night destination for people to eat after a night of drinking. (According to Kevin J. Mullen, The Hop Sing Tong actually owned The Golden Dragon restaurant.) Calhoun says that when the Joe Boys got there, they found who they they were looking for: Wah Ching chief Michael “Hot Dog” Louie and Frankie Lee of the Hop Sing Boys.

According to Mullen, the Wah Ching and Hop Sing Tong members saw the shooters coming and immediately hit the floor. But many other people were not so lucky:

The shooters sprayed the restaurant with fire from shotguns and semi-automatic weapons, killing five innocent bystanders and wounding 11 more in the fusillade.

According to Eve Batey of SFist, the Golden Dragon massacre led the SFPD to create the “Chinatown Squad” to get rid of gang activity in the area, which led to the disbanding of the Joe Boys.

Above: A picture of the Golden Dragon Restaurant, from Kevin Mullen’s historical essay on FoundSF, photograph by Chris Carlsson

0 notes

Text

Alternative Loyalty and the American Council for Judaism

By Steven Trebach, Research Intern

I am a Research Intern at the Center for Jewish History (CJH) and a recent graduate of Haverford College. My original goal was to research dual loyalty, which led me to documents concerning the American Council for Judaism (ACJ) within the Center’s Partner’s collections, particularly the American Jewish Historical Society. In the mid-20th century, the ACJ accused Zionist Jews of not being loyal to America.

This blog post intends to explore the nature of the ACJ’s claims using archival and supplementary materials. In this piece, I will introduce the ideas of dual and alternative loyalty, the ACJ, illustrate the nature of ACJ’s alternative loyalty charges, and try to understand how these charges fit into larger patterns of alternative loyalty. The specific AJHS archival materials in question are a series of correspondences from and about the ACJ.

First, my research revealed several kinds of alternative loyalty charges that have developed with regard to Jews throughout the world. The most relevant to the ACJ’s accusations is what can be referred to as polity conflict. Jewish polity conflict is the accusation that Jews are loyal to another geopolitical entity, especially one whose interests can interfere with those of the polity in which said Jews live. When the charge acknowledges a Jew’s loyalty to their place of residence alongside the conflicting foreign body, the allegation is dual loyalty. For example, the Iraqi fear that Iraqi Jews supported British consolidation of power in Iraqi, leading to a pogrom, Al-Farhud. (Moreh & Yehuda, 2011, p.12). The second major kind of alternative loyalty is ideological disloyalty, based on the idea that Jews hold allegiance to a foreign philosophical movement conflicting with society’s values and safety. An American example of this is the disproportionate targeting of Jews for anti-communist loyalty tests by the Postal service during the late 1940s (Spiegler, November 4, 1948).

These kinds of allegations have precursors in anti-Semitic conspiracies, such as blood libel, and events, such as the Dreyfus affair. The modern phenomenon, into which the ACJ’s allegations fit, arose with the establishment of revolutionary resistance politics within Jewish communities, such as Zionism, Bundism, and multiple forms of socialism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Though these movements were largely concentrated in Eastern European Jewry and their American progeny, alternative loyalty claims related to these revolutionary resistance movements occurred from Argentina to Hashemite Iraq. That these indictments were leveled against diverse, loosely related communities might suggest they arise not from a community’s behavior but rather from a source within the accusing society.

Image: Judah Magnus Museum via FoundSF

The ACJ is a Jewish organization that was founded in opposition to Zionism. The group has many of its organizational and ideological roots in the 1942 Atlantic City conference, a meeting of 36 rabbis concerning the growth of Zionism, which revealed a schism between supporters of “nationalism versus religion” and vice versa, in which the ACJ took a firm stance against Jewish nationalism (Kolsky, 1990, pp.49, 54).[1] The ACJ’s position, according to correspondences by one of its leading figures Elmer Burger, was that Jews were not “not a minority group of Americans identified by a separate ‘Jewish’ nationality” but rather a religion; the ACJ’s ultimate desire was secular integration for Jews in America (Berger, April 21, 1950, pp. 2,8) Thus, the ACJ rejected any Zionism or nationalism that contradicted that sentiment. As such, the ACJ was “the only American Jewish organization ever formed for the specific purpose of fighting Zionism” (Kolsky, 1990, p.ix). This distinction placed the ACJ outside of mainstream Jewish life.

It is in this context that the ACJ seems to make two kinds of common alternative loyalty charges. The charges are framed as concern for the wellbeing of the Jewish community rather than fear of Israeli desires contradicting American ones. Their dual loyalty claim, the charge that one had divided one’s loyalties between two polities, is well illustrated in Norman Thomas’ “Letter to Maurice Spector.” Thomas argues that the American Council puts forward “the charge that certain statements by Zionist leaders here and in Israel opened the way to the development of dual loyalty, and to exaggerated charges of dual loyalty by actual or potential anti-Semites” (Thomas, February 3 1950). Just as Iraqis during Al-Farhud may have seen hypothetical Jewish allegiance to the British as a potential danger to Iraq’s sovereignty, the ACJ saw Zionist loyalty to Israel as a potentially dangerous conflict with their American citizenship.

The ACJ’s criticisms also seem to contain an element of ideological treason, the accusation that one is committed to ideas deleterious to one’s polity. Elmer Burger, a rabbi and ACJ leader, “considered Zionism the last attempt to maintain any traces of ghetto control over the lives of individual Jews” (Kolsky, 1990, p.109). This critique of Zionist Jews does not posit Zionism as an allegiance to another polity but rather as an ideology that acts negatively upon Jews. I believe this is comparable to the Argentine fears of Jewish communism and the Soviet fears of Jewish anti-communism.

There are two key differences between most alternative loyalty charges and those of the ACJ that must be addressed. All of the other rhetoric originated in a source external to the Jewish community and arguably entailed hostility towards it. The ACJ’s ideas arose within the Jewish community and suggest concern for it. Even the direct accusation of dual loyalty is meant to mitigate potential anti-Semitism.

The clearer of the two is the internal-external division. Though on the surface, this may seem major, it is easily resolvable with regards to the dual loyalty case. The ACJ followed the premise that “we are Americans”; therefore, they charged dual loyalty not as Jews but as Americans (Berger, April 21, 1950, p.1). Thus, they saw themselves as holding no special communal attachment to the Zionists on the plane of nationalism outside of an Americanism they shared with gentiles. Therefore, from the ACJ’s perspective, the accusation was against a different community.

Demographic concerns bolster the above claims. “Council members were differentiated from the rest of American Jewry on religious, social and economic as well as ideological grounds” being primarily upper-class, Reform, German Jews as opposed to poorer, more religious Eastern European Jews (Halperin, 1961, p.454). These two populations inherited two very different relationships with Judaism and nationalism. “German Jews… were barely distinguishable from other German immigrants” and “were proud of their German heritage…and retained their German nationalism even after becoming American citizens,” a mentality that likely informed their “the opinion that Judaism is primarily a religion” (Kolsky, 1990, p.18) (Thomas, February 3 1950). Accepting Jewish nationalism would intrude upon this treasured German heritage. Conversely, Eastern European Jews “had lived in Jewish enclaves in Eastern Europe and … considered themselves an ethnic group” (Kolsky, 1990, p.22). Thus, strains of Zionism positing Jews as a separate people would be more attractive to them than to members of the ACJ. Thus, as they had strong social and cultural differences, the ACJ may have felt themselves part of a completely different community than these other Jews.

The above explanation does not account for the ACJ’s intended benevolence. Why would an organization attempting to protect the Jewish community use rhetoric reminiscent of more hostile groups? One hypothesis is that ACJ members such as Norman Thomas can be taken at face value: they fear anti-Semitism being visited upon Jews for their dual loyalty. By providing the same rhetoric devoid of violence, perhaps they could extinguish alternative loyalties before they draw the ire of more hostile groups. Zionist counterpropaganda, however, had a different explanation. They argued via the ideas of Kurt Lewin that “the person seeking to enter a higher status group has to be especially careful to disown any connection with the ideas of the group to which he once belonged” (Halperin, 1961, pp. 456-457). As ACJ members mostly of or striving for higher social status than Zionist Jews, Lewin’s idea seems applicable. One could therefore argue that although the ACJ claimed benevolence, their true motivations were an internalized hostility towards association with Jews of lower social and economic status.

Ultimately, the case of the ACJ provides a clear but complicated example of alternative loyalty charges that demonstrates the intellectual complexities surrounding the topic. The libraries and AJHS archives within the CJH contain sufficient archival and supplementary data for the future in-depth evaluation this topic deserves.

Works Cited:

Archival Materials:

American Council for Judaism. (1947). American Council for Judaism Collection, undated, 1943-1991 . American Jewish Historical Society. Call Number: I-344.

Berger, April 21, 1950

Thomas, February 3, 1950

NJCRAC I-172: Committees- Committee on Overt Anti-Semitism- Loyalty Test – Postal Employees- 1948-1951-1&2. American Jewish Historical Society.

Spiegler, November 4, 1948

Published Books:

Halperin, S. (1985). The Political World of American Zionism. Silver Spring, MD: Information Dynamics Inc.

Kolsky, T. A. (1990). Jews Against Zionism: The American Council for Judaism. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

[1] It should be noted that the Atlantic City conference took place after the aforementioned Farhud in Iraq, but it is not clear whether or not the participants were influenced or aware of said events, given the overwhelming cacophony of the contemporaneous World War II.

#American Judaism#Reform Judaism#Research Intern#Steven Trebach#American Council for Judaism#Dual Loyalty#Alternative Loyalty

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

History of SF’s sewer system dating back to the first box sewer installed in 1860.

“ From 1908 to 1935, sewers were gradually organized into zones, with each area dumping to the bay or ocean in one of the 35 outfalls. Citizen groups demanded usable beaches, and particularly faulted cities like San Francisco that had mismanaged their coast. Under this pressure, and with federal public works money flowing easily under the New Deal, the second wastewater master plan was released in 1935. It called for treatment plants to capture sewage and treat it to what is called a primary level-removal of gross debris and grit. In 1938, the first treatment plant, at the end of Golden Gate Park, went into operation. In 1951, two more plants were built. One plant, at North Point, filtered effluent and pumped it into the bay near Pier 39, while sending the leftover sludge south for further treatment. “

“ In dry weather, all of these plants dumped primary-treated effluent directly into the bay or ocean. However, in wet weather, they, along with all the old outfalls at Mission Creek, Mile Rock, Marina Green, Fort Funston, Griffith Street, and elsewhere spewed unprocessed sewage. Big pools of discolored, toxic water were often visible, and many residents were bothered by the continued lack of swimming and fishing opportunities along the waterfront. Even in the 1960s, with growing environmental awareness all around, people pointed out that there were often over 100 days per year when Ocean Beach was too poisoned for swimming. “

0 notes

Photo

Photograph of Chinese American artist, Yun Gee (image 1), and Gee with other members of the Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club in San Francisco (image 2) in 1926. In the group photograph, Gee is modelling a bust of an Asian man while the other painters are at work on their canvases.

The Artists’ club form in 1926 in San Francisco’s Chinatown and was composed of immigrants from Guangdong in their late teens and early 20s. Its headquarters, which also served as a studio, teaching centre, exhibition space, and possibly shared bedroom, was located in an upper room at 150 Wetmore Place. Its membership fluctuated during its 15 or so years of existence but probably had a dozen members at any given time. Its most famous members were co-founder and leader Yun Gee, and Eva Fong Chan (1897-1991) who became a member in the early 1930s and was the only woman known to be part of the Club. Unlike Fong, who was a former beauty queen turned piano teacher and received an education, the young men of the Club were working-class and probably held menial jobs such as servants, cooks, dishwashers, and launderers. The Club was devoted to learning, experimenting, and teaching the techniques of modernist oil painting and the latest Parisian styles, while taking the street scenes, peoples, and objects of Chinatown as subject matter. Little of the painters’ works survives.

Sources: FoundSF-1, 2, Oxford Art Online

#Asian Americans#Chinese Americans#artists#1920s#San Francisco#Chinatown#Guandong#Chinese Revolutionary Artists' Club#Yun Gee#bust#paintings#Eva Fong Chan#oil painting

10 notes

·

View notes