#fuadudemans; c-institute; thegoldenthread; universality; Economics; Socio-economics; Poverty&Wealth; self development; cyberiagroup;

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Growing to death: A punctuated extinction (part 3 of 3)

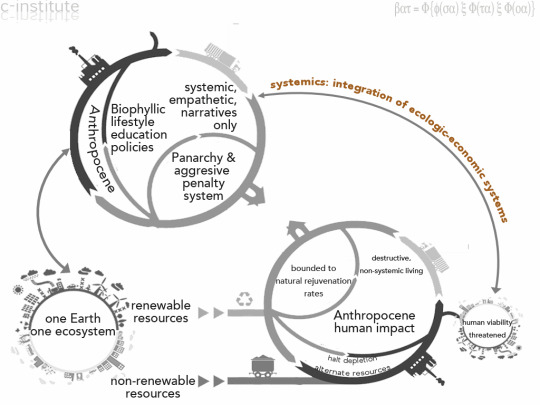

Fortunately, we have an increasing number of systemic-oriented movements challenging the mechanical minded, offering counter hegemonic options for a new social ecology4. The essence of such new social networks must reinforce as its primary function, the vitality of true systemic integration underlying a “one-earth lifestyle”1, 5. Should we remain unwilling to make needed variations to our excessive consumption, then we must be reminded that we are dealing with natural complex adaptive systems, and that adjustments will eventually and finally be thrust upon us, via nature’s own regulatory response1, should we not adopt a managed process by design5. The rapidity of our ecosystem changes5, should have alerted us into immediate action. Instead, all countries and nations are still instructed to pursue goals of constant growth, as opposed to seeking well-being5 (a key tenet of a new social ecology)1. Astute critics decries our selfishness, individualism and greed that drive consumption and acquisitiveness6. Others warn of problems arising from the expansion of the machine civilization, urging we end wars and human misery7. These holistic insights recognise our classic economic and development as flawed7, warning of the unopposed movement toward the “robotisation of the individual”7.

Today, this view of humanity is a reality, where we are seen and treated as consuming machines6 constantly having to pay taxes to governments, and profits to corporations. Mechanical leadership across both public and private sector fear a re-awakening in valuing how powerful we are as individuals who form collectives. As individuals we form the backbone of societies and thus expect to be governed by accountable and responsible persons, since it is the condition of basic freedom that we be ruled by an authority that we control6. In modern day acquisitive societies, both governments and corporations have a fixed interest in constantly promoting the accumulation of things – the one require citizens to pay taxes; the other demand profits. The chief mechanism of the acquisitive society promises “unfettered freedom” to the successful or strong, whilst the rest of us must strive toward this elusive goal6. This absorbing vision of infinite expansion, vaporise our moral fabric6, since we do not become religious or wise or artistic as these domains imply knowing and accepting limits. Instead, we wish to dominate and change the face of nature6. These warnings uttered almost 100 years ago has become our reality, and serve as a powerful exemplar of our negligence. Our destructive development models have taken us to the precipice of a self-induced extinction (Anthropocene). Institutional leaders continue to turn a blind eye and a deaf ear to our greatly flawed development path1. It speaks to the alluring power of consumption cartels, distracting us with our own vanity, and numbing our intellect by occupying us with irrelevant gadgets1, 6, 8.

Ironically, capital owners and industrialists retain models that plunder our GPG’s, whist indigenous peoples are trying to preserve it8. A power dynamic, evident between Rich-Poor or North-South that underlie exploitative themes that resist adoption of systemic lifestyles1, 6, and instead opt for congruence of self-interest8. It is fortuitous that we have so many movements speaking up, and who are committed to free us from the mechanistic leadership punting the fraud of “compete-or-die” logic9.

References:

1. Udemans, F., 2008, The golden thread: escaping socio-economic subjugation, an experiment in applied complexity science, Authorhouse UK;

2. Smith, J.W., 1989, The World’s Wasted Wealth: the political economy of waste, New World’s Press, 1989, pp.44,45;

3. Turner, G., and Alexander, C., 2014, The Guardian: Limits to growth was right. New research shows we’re nearing collapse;

4. Tokar, B., 2008, On Bookchin’s Social Ecology and its Contributions to Social Movements; Capitalism Nature Socialism Volume 19, Number 1;

5. Randers, J., 2012, The Real Message of The Limits to Growth, A Plea for Forward-Looking Global Policy, GAIA, 21/2, 2012: 102;

6. Tawney, R.H., 1920, The Acquisitive Society, Quotes taken from the 1920 edition (http://gutenberg.org/ebooks/33741), published by Harcourt, Brace and Company; and, Tawney, R.H., 1960, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R._H._Tawney;

7. Brown, H., 1954, The challenge of man’s future, Engineering and Science Vil.17 (6), pp.22-32, Caltech office of Relations; http://resolver.caltech.edu/CaltechES:17.6.brown; Available: Folinsbee, R. E., and Leech, A.P., 1974, Energy – Challenge of man’s future (Part I), Journal of the Geological Association of Canada, Vol. 1 (1);

8. Quinn, S., 2018, Global Species Extinction: Humans Are Now the Asteroid Hitting the Earth, Indigenous populations are taking the lead in protecting the environment, Global Research, July 31, 2018;

9. Dawson, J., Jackson, R., Norberg-Hodge. H., 2010, Economic Key: Gaian Economics – living well within planetary limits, Permanent Publications, First edition, © 2010, Gaia Education, ISBN 978185623056 8;

10. Grossi , G., Goglio, P., Vitali, A., Williams, A.G., 2018, Livestock and climate change: impact of livestock on climate and mitigation strategies, Animal Frontiers: Volume 9, Issue 1, January 2019, Pages 69–76, https://doi.org/10.1093/af/vfy034;

11. Mottet, A., and Steinfeld, H., 2018, Cars or livestock: which contribute more to climate change? FAO Tuesday, 18 September 2018 08:36 GMT;

12. Cornes, R. and Sandler T., 1996, The Theory of Externalities, Public Goods, and Club Goods, 2nd Edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press;

13. Kocks, A., 2005, The Financing of UN Peace Operations – An Analysis from a Global Public Good Perspective, INEF Report, Institut für Entwicklung und Frieden der UniversitätDuisburg-Essen / Campus Duisburg, Heft 77;

14. Chen, L ; Evans, T. & Cash, R., 1999, Health as a Global Public Good, In: Global Public Goods: International Co-operation in the 21st Century, Kaul, I; Grunberg, I & Stern, M (Ed.), New York: Oxford University Press; Cornes, R. and Sandler T., 1996, The Theory of Externalities, Public Goods, and Club Goods, 2nd Edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Sandler, T., 1997, Global Challenges: An Approach to Environmental, Political and Economic Problems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: chapter 5;

15. Global footprint network, 2019, (https://www.footprintnetwork.org);

#fuadudemans; c-institute; thegoldenthread; universality; Economics; Socio-economics; Poverty&Wealth; self development; cyberiagroup;#complexity science#ecology

0 notes

Text

Growing to death: A punctuated extinction (part 2 of 3)

The extravagant lifestyles that consumers are “required” to pursue, are allied to constant growth models. A model that demand compulsive consumption to be supremely pervasive, despite it being scientifically impossible (since it breaches both first and second laws of thermodynamics). It is must therefore be anti-leadership that continue to direct us to chase impossible lifestyles?

We are bombarded across media platforms, to pursue the unattainable – a misdirection that keep us occupied, whilst surreptitiously ensuring we remain unthinking gluttonous consuming machines. This elaborate ruse covers factory-styled value chains that are end-to-end, from: manufacturers, retailers, advertisers, financiers, advisors, and consumers - all being equally blind and daft to believe in continuous growth? The global focus upon constant growth (e.g. GDP of nations), are relentlessly pursued by destroying Global Public Goods (GPG’s). A global public good (GPG) is a good that can be used, but not be destroyed for future generations – more exactly, a GPG has 2 key properties: (1) non-rival and (2) non-excludable12. Non-rival imply consuming the good by one person, does not diminish obtainability of the good for consumption by another. Non-excludable imply none can be excluded from using the good. If both requirements are completely satisfied, a public good is said to be pure13. Typical examples of GPG’s include the earth’s air, water, oceans, forests, animals, space, GPS, etc. Importantly, GPG’s are known to be a poorly managed global problem14.

All of these “free” vitally, inter-locked life-sustaining resources continue to be abused by inward and selfish leadership, unwilling to grasp the true cost of “big-is-better” developmental premise. To put it bluntly, even if each human on earth, theoretically had sufficient financial capital to afford a “1%-lifestyle”, the direct impact upon GPG’s would result in ecological collapse. In other words, our physical and finite planet, does not have the resource capacity to sustain it. Sadly, very few leaders are willing to admit this since all of humanity, from City to Village, are still sold a lifestyle that can only end in devouring the planet4. The opulent, hi-tech lifestyles we are “required” to pursue under continuous consumption models, have inherent threats, like: defying earths limits; increase inequality; increase poverty and oppression; and most vitally - destroying the planet’s ability to sustain complex life4. So, our mechanistic leadership across public and private sphere’s endorse corrosive development models that murder living systems (ecosystem). As an example, if everyone in the world today could enjoy a lavish lifestyle, then we would need 5 planets (5 earths)14, to support it. Planetary viability (earth’s survival) requires us to change the thinking from the dominant mechanical stupidity, to systemic enlightenment1, for this is the only way to fundamentally change our relationship with one another and the ecosystem.

References:

1. Udemans, F., 2008, The golden thread: escaping socio-economic subjugation, an experiment in applied complexity science, Authorhouse UK;

2. Smith, J.W., 1989, The World’s Wasted Wealth: the political economy of waste, New World’s Press, 1989, pp.44,45;

3. Turner, G., and Alexander, C., 2014, The Guardian: Limits to growth was right. New research shows we’re nearing collapse;

4. Tokar, B., 2008, On Bookchin’s Social Ecology and its Contributions to Social Movements; Capitalism Nature Socialism Volume 19, Number 1;

5. Randers, J., 2012, The Real Message of The Limits to Growth, A Plea for Forward-Looking Global Policy, GAIA, 21/2, 2012: 102;

6. Tawney, R.H., 1920, The Acquisitive Society, Quotes taken from the 1920 edition (http://gutenberg.org/ebooks/33741), published by Harcourt, Brace and Company; and, Tawney, R.H., 1960, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R._H._Tawney;

7. Brown, H., 1954, The challenge of man’s future, Engineering and Science Vil.17 (6), pp.22-32, Caltech office of Relations; http://resolver.caltech.edu/CaltechES:17.6.brown; Available: Folinsbee, R. E., and Leech, A.P., 1974, Energy – Challenge of man’s future (Part I), Journal of the Geological Association of Canada, Vol. 1 (1);

8. Quinn, S., 2018, Global Species Extinction: Humans Are Now the Asteroid Hitting the Earth, Indigenous populations are taking the lead in protecting the environment, Global Research, July 31, 2018;

9. Dawson, J., Jackson, R., Norberg-Hodge. H., 2010, Economic Key: Gaian Economics – living well within planetary limits, Permanent Publications, First edition, © 2010, Gaia Education, ISBN 978185623056 8;

10. Grossi , G., Goglio, P., Vitali, A., Williams, A.G., 2018, Livestock and climate change: impact of livestock on climate and mitigation strategies, Animal Frontiers: Volume 9, Issue 1, January 2019, Pages 69–76, https://doi.org/10.1093/af/vfy034;

11. Mottet, A., and Steinfeld, H., 2018, Cars or livestock: which contribute more to climate change? FAO Tuesday, 18 September 2018 08:36 GMT;

12. Cornes, R. and Sandler T., 1996, The Theory of Externalities, Public Goods, and Club Goods, 2nd Edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press;

13. Kocks, A., 2005, The Financing of UN Peace Operations – An Analysis from a Global Public Good Perspective, INEF Report, Institut für Entwicklung und Frieden der UniversitätDuisburg-Essen / Campus Duisburg, Heft 77;

14. Chen, L ; Evans, T. & Cash, R., 1999, Health as a Global Public Good, In: Global Public Goods: International Co-operation in the 21st Century, Kaul, I; Grunberg, I & Stern, M (Ed.), New York: Oxford University Press; Cornes, R. and Sandler T., 1996, The Theory of Externalities, Public Goods, and Club Goods, 2nd Edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Sandler, T., 1997, Global Challenges: An Approach to Environmental, Political and Economic Problems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: chapter 5;

15. Global footprint network, 2019, (https://www.footprintnetwork.org);

#fuadudemans; c-institute; thegoldenthread; universality; Economics; Socio-economics; Poverty&Wealth; self development; cyberiagroup;#appliedcomplexityscience; ecosystem; systemscience

0 notes

Text

Growing to death: A punctuated extinction (part 1 of 3)

Most of our discussion papers have a purposeful focus upon our embedded thinking patterns that cause vast ruin to our societies and our ecosystem1. Today weakness in thought leadership are reflected in the aversion of both impotent governments and voracious corporations to adopt real empathetic change. The advanced warnings from wide research areas, like for example, “limits to growth” - published more than 30 years ago, expose our unspoken approval to overshoot the carrying capacity of earth. A destructive pattern of human development and exploitation, called the Anthropocene. It represents our greatest embarrassment yet – a human induced extinction event?

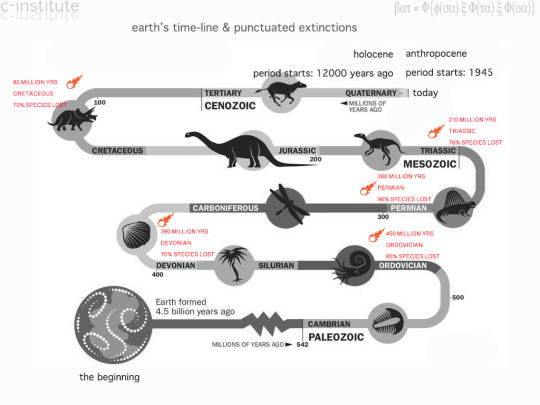

To put this into perspective, earth’s geological records contain evidence of 5 major extinction events1, each time killing off most life forms when they occur. An extinction event that struck in the Cretaceous period, was popularised for wiping out the dinosaurs. Indeed, earth’s fossil records contain punctuated equilibria (evidence of massive and rapid evolutionary change), as part of its geological storyline1. The Anthropocene is now considered to equal these events in terms of the scale of destruction – meaning humans have over-exploited earths capacities to a point where it equals an extinction event.

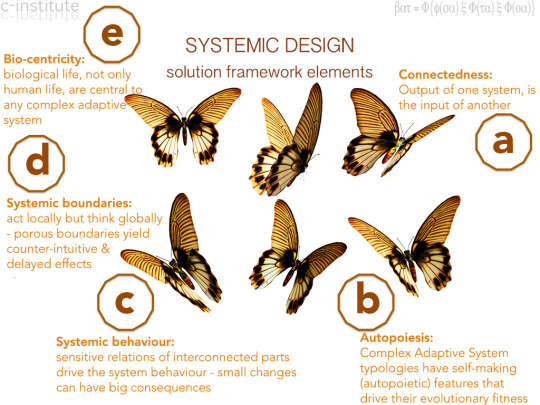

Unsurprisingly, much research warns about selfish, mercenary development themes causing ruin and collapse of ecosystems1, 3. A central message being we immediately cease and desist with lies and deceptions of constant growth models and theories, since it purposefully ignores the natural limitations of our ecosystem2. Today still, prevailing development models remain mechanistic, inward and selfish replicas of high consumption. Concerns have been raised as far back as WW1, called the rise of the synthetic world4, offering detailed analysis of pollution, urban migration, and chemical agriculture4. It argued for holism and systemic integrative thought and action4. Most essentially, it described the drive to dominate the natural world as a destructive byproduct of social grading and elitism4. Insight from this research promote practices of systemic principles of non-hierarchical, organic societies, having features like: interdependence; usufruct; unity-in-diversity; complementarity; irreducible minimum (principle where communities are responsible for meeting their members most basic needs)9. This directly opposes modern industrialisation themes that only promote large, grand, scaled, factory type solutions, be it in sectors of education, infrastructure, health, farming, etc. Critically, our business and economic thinking remain the driver of this flawed mentality of “big is better” – which automatically embed solutions that remove localised jobs, causing ecological ruin via concentration and value chain domination1.

A case in point is today’s factory-type cattle farming that generate carbon emissions, comparable to the transport sector10. Mega-production livestock has become a major contributor to global warming (14.5% of total emissions)10. Although emission comparisons between livestock and transport may suffer from various biases (lobby groups, corporate research, etc.); whilst comparison methods are often flawed (e.g. comparing direct emissions from one sector to both direct and indirect emissions of another)11 - the point however is that both sectors (transport and livestock) are serious contributors to global warming. This is because of “big-is-better” type central economic planning, where mechanistic leadership advance faulty development models having weakly constructed solutions like technology and green capitalism? Ideas that remain rooted in continuous growth and consumption, requiring us to consume excessively, without thought. The crucial affair is excessive consumption, so fanatically promoted by both corporations and governments. We see it in stock markets whereby listed companies opt to use false data and fake news to prop up their share prices; we see it in product design where we are compelled to continuously consume by replacing and upgrading gadgets, cars, clothes, etc.; we see it in the grand, extravagant lifestyles promoted to us all?

References:

1. Udemans, F., 2008, The golden thread: escaping socio-economic subjugation, an experiment in applied complexity science, Authorhouse UK;

2. Smith, J.W., 1989, The World’s Wasted Wealth: the political economy of waste, New World’s Press, 1989, pp.44,45;

3. Turner, G., and Alexander, C., 2014, The Guardian: Limits to growth was right. New research shows we’re nearing collapse;

4. Tokar, B., 2008, On Bookchin’s Social Ecology and its Contributions to Social Movements; Capitalism Nature Socialism Volume 19, Number 1;

5. Randers, J., 2012, The Real Message of The Limits to Growth, A Plea for Forward-Looking Global Policy, GAIA, 21/2, 2012: 102;

6. Tawney, R.H., 1920, The Acquisitive Society, Quotes taken from the 1920 edition (http://gutenberg.org/ebooks/33741), published by Harcourt, Brace and Company; and, Tawney, R.H., 1960, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R._H._Tawney;

7. Brown, H., 1954, The challenge of man’s future, Engineering and Science Vil.17 (6), pp.22-32, Caltech office of Relations; http://resolver.caltech.edu/CaltechES:17.6.brown; Available: Folinsbee, R. E., and Leech, A.P., 1974, Energy – Challenge of man’s future (Part I), Journal of the Geological Association of Canada, Vol. 1 (1);

8. Quinn, S., 2018, Global Species Extinction: Humans Are Now the Asteroid Hitting the Earth, Indigenous populations are taking the lead in protecting the environment, Global Research, July 31, 2018;

9. Dawson, J., Jackson, R., Norberg-Hodge. H., 2010, Economic Key: Gaian Economics – living well within planetary limits, Permanent Publications, First edition, © 2010, Gaia Education, ISBN 978185623056 8;

10. Grossi , G., Goglio, P., Vitali, A., Williams, A.G., 2018, Livestock and climate change: impact of livestock on climate and mitigation strategies, Animal Frontiers: Volume 9, Issue 1, January 2019, Pages 69–76, https://doi.org/10.1093/af/vfy034;

11. Mottet, A., and Steinfeld, H., 2018, Cars or livestock: which contribute more to climate change? FAO Tuesday, 18 September 2018 08:36 GMT;

12. Cornes, R. and Sandler T., 1996, The Theory of Externalities, Public Goods, and Club Goods, 2nd Edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press;

13. Kocks, A., 2005, The Financing of UN Peace Operations – An Analysis from a Global Public Good Perspective, INEF Report, Institut für Entwicklung und Frieden der UniversitätDuisburg-Essen / Campus Duisburg, Heft 77;

14. Chen, L ; Evans, T. & Cash, R., 1999, Health as a Global Public Good, In: Global Public Goods: International Co-operation in the 21st Century, Kaul, I; Grunberg, I & Stern, M (Ed.), New York: Oxford University Press; Cornes, R. and Sandler T., 1996, The Theory of Externalities, Public Goods, and Club Goods, 2nd Edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Sandler, T., 1997, Global Challenges: An Approach to Environmental, Political and Economic Problems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: chapter 5;

15. Global footprint network, 2019, (https://www.footprintnetwork.org);

#appliedcomplexityscience; ecosystem; systemscience#fuadudemans; c-institute; thegoldenthread; universality; Economics; Socio-economics; Poverty&Wealth; self development; cyberiagroup;

0 notes

Text

Ecological entanglement (part 3 of 3)

Therapeutic effects of contact with nature are supported by research showing 90% of people suffering from depression, experience increased self-esteem after a walk in a park12. It also reveals 44% of people visiting shopping centre’s feel a decrease in self-esteem, whilst 22% feel more depressed12. Also important is that localised economic thrusts represent a powerful solution multiplier, spending more time as communities; more time with each other; more time in nature12.

This suggests marked improvements over the current and pervasive selfish economic development models. As such, the increasing call the embrace holistic or systemic models of thinking and doing1, are being echoed by many and creatively explained by Korten et al, in terms of Empire (referring to mechanistic models) versus Earth community (referring to systemic models)13. This research reveal that Empire seek control by domination at all system levels, be it nation or family. It brings fortune to a minority, at the expense of the majority who remain bound in poverty and servitude1, 13. The team further juxtaposes our classic inward-selfish development model against the more inclusive-sharing model engendered by the Earth community: localising control; organising via empathetic partnerships; relying upon sharing and cooperation between all members. The underlying scientific data for Earth community (systemic models), stem from a range of research areas: quantum physics; cosmology; mysticism; biology; psychology; anthropology; sociology; archaeology, etc.1,13. Important to remember is that natural systemic orientation existed well before Empire, which we must now re-discovered and embrace, since the current global recession and implosion of morally bankrupt institution have reached its limits in exploiting people and the environment1, 13. These are results that stem from the loss of respect for the generative powers of life, and our systemic connection to the living earth1, 13. We cannot expect the mechanical minded to lead the way, we need systemic leadership to direct and manage amelioration efforts1, 13. These are the narratives that must become mainstream; these are the stories that must be told and shared. Current stories remain dominated by Empire13, perpetuating models that are flawed and dated1. Agents and agencies of Empire continue to cultivate, reward, and amplify the storytellers who support their mechanistic model, whilst limiting systemic one’s13. The stories repeated most, are the ones most believed13, but with slow progress by the systemic minded, whose stories are reaching wider audiences, breaking down the myths of Empire, by driving empathetic and sharing orientations.

References:

Udemans, F., 2008, The golden thread: escaping socio-economic subjugation, an experiment in applied complexity science, Authorhouse UK;

2. Vanbergen, G., 2017, The crises of trust in Democracy & Globalisation, The European Financial Review, July 26, 2017, http://www.europeanfinancialreview.com/?p=1726; Smith, J.W., 1989, The World’s Wasted Wealth: the political economy of waste, New World’s Press, 1989, pp.44,45;

3. de Puydt, P.E., 1860, Panarchy (http://www.panarchy.org/depuydt/1860.eng.html), first published in French in the Revue Trimestrielle, Bruxelles, July 1860; Etymology of Panarchy, http://www.p2pfoundation.net/Panarchy_Etymology, from James P. Sewell and Mark B. Salter, "Panarchy and Other Norms for Global Governance: Boutros-Ghali, Rosenau, and Beyond", Global Governance, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 373-382, 1995;

4. Folke, C., 2016, Framing Concepts in Environmental Science Online Publication Date: Sep 2016, 10.1093/acrefore/9780199389414.013.8, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science; (Folke, C., 2018, The Beijer Institute of Ecological Economics, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences; Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University);

5. Berkes, F., Colding, J., Folke, C., 2003, Navigating social-ecological systems: Building resilience for complexity and change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK;

6. Holing, C.S., 2001, Understanding the complexity of economic, ecological and social systems, Ecosystems, Spinger-Verlag;

7. Biggs, R., Schlüter, M., Schoon, M.L., 2015. Principles for building resilience: sustaining ecosystem services in social-ecological systems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781316014240

8. Vitousek, M.P., Ehrlich, R.P., Ehrlich, H.A., Matson, A.P., 1986, Human Appropriation of the Products of Photosynthesis, BioScience, Vol. 36, No. 6, June, 1986, page 368-373, University of California Press, American Institute of Biological Sciences Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1310258;

9. Wahl, C.D., 2018, Building Capacity for the Re-design of our Economic Systems, Gaia Education, 16 March, 2018;

10. Daly. E.H., 2017, Sustainable Growth: An Impossibility Theorem, Gaian Economics: Living Well within Planetary Limits, Second volume, Gaia Education, Four Keys to Sustainable Communities series; https://medium.com/@gaiaeducation/sustainable-growth-an-impossibility-theorem-d78178dcac9c;

11. Brundtland et al, 1987, Brundtland Commission, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=BrundtlandCommission&oldid=847324915;

12. Norberg-Hodge. H, 2007, The Economics of Happiness, Gaian Economics: Living Well within Planetary Limits, Volume 2, Gaia Education’s Four Keys to Sustainable Communities series; The Economics of Happiness By Helena Norberg-Hodge Printed in Resurgence magazine 2007; http://www.skalaecovillage.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Gaian_Economics.pdf#page=162;

13. Korten, D., 2006, The Great Turning: From Empire to Earth Community, Berrett-Koehler Publishers,2006; Gaian Economics, Volume 2, Gaia Education, Four Keys to Sustainable Communities series; Korten, D., 2006, The Great Turning: From Empire to Earth Community, Ready for a Change?, The Case for Earth Community, YES! A Journal of Positive Futures Summer 2006 17, 206/842-0216, www.yesmagazine.org;

14. Lumber R, Richardson M, Sheffield D, 2017, Beyond knowing nature: Contact, emotion, compassion, meaning, and beauty are pathways to nature connection, PLoS ONE 12(5): e0177186. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177186;

#appliedcomplexityscience; ecosystem; systemscience#gigamaps#fuadudemans; c-institute; thegoldenthread; universality; Economics; Socio-economics; Poverty&Wealth; self development; cyberiagroup;

0 notes

Text

Ecological entanglement (part 1 of 3)

Most people will agree that current levels of mistrust, are due to the many gross violations and corrupt practices across private and public sectors2. Most will also agree that we require robust, resilient, and empathetic, leadership and management, across institutions 1, 5. Building this kind of social systems require high degrees of robustness (e.g. Panarchy – globally resilient institutional protocols and governance3).

Social systems (organisations; Towns; Cities; Countries) can be better understood as complex adaptive systems – i.e. systems containing many sub-systems like production systems, energy systems, transport systems, suburbs, people, ecosystems, etc. These sub-systems function together to give each organisation; Town; City; Country, its unique features, which include resilience. Resilience describes the period it takes for a system to return to equilibrium, after being disturbed6, and has been applied across areas like policy, poverty alleviation, political frameworks, and business strategies4. Attempts to integrate socio-ecological system needs have yielded four principles to build adaptive capacities5:

· Accept change (entropy) & uncertainty (Quantum mech.) as inherent to life;

· Embrace diversity (Variety) for regenerative functions;

· Combine different types of knowledge for enhanced learning;

· Promote social-ecological integration;

Our actual systemic inter-connectedness (intimate linkages), added to our pervasive technologically driven societies, generate complex dynamics across domains4, which often produce various counter-intuitive outcomes. These effects are managed using linear thought and practice, which in turn co-creates the structural wickedness of our socio-economic systems. This mechanistic management produce rigid and unseeing institutions, unable to halt skewed developmental outcomes1 whilst increasing ecological vulnerabilities6. As a means of curbing environmental damage, researchers propose systemic principles like7: Maintain diversity and redundancy; Understand interfaces of social-ecological systems; Manage slow variables and feedback loops; Encourage learning and experimentation; Empathetic participation; Promote polycentric governance systems. These ideals ensure economic systems actually consider and integrate into ecological systems, providing options for systemic development; It underlines the importance of multi-stakeholder governance; multiple metrics; and multiple knowledge systems. Importantly, it recognises Requisite Variety as vital to systemic integration. This is important when we reflect upon global problems or challenges that do not obey the linearity we were educated in; nor the predictability we were taught to purse and desire. In other words, problems or challenges do not obey the neat boundaries we created (e.g. HR; Finance, Tech, etc.), but rather crosses them, and often include all or most specialist areas. Similarly, protecting our natural resources transcend and cross different disciplines, boundaries, and scales1, 5 (e.g. engineering; finance; political; business; etc.). The systemic sciences represent our only robust platform to deal with such entanglement1, providing better toolsets to cope with divergent outcomes from the wickedness that stem from socio-ecological entanglement5,1.

References:

Udemans, F., 2008, The golden thread: escaping socio-economic subjugation, an experiment in applied complexity science, Authorhouse UK;

2. Vanbergen, G., 2017, The crises of trust in Democracy & Globalisation, The European Financial Review, July 26, 2017, http://www.europeanfinancialreview.com/?p=1726; Smith, J.W., 1989, The World’s Wasted Wealth: the political economy of waste, New World’s Press, 1989, pp.44,45;

3. de Puydt, P.E., 1860, Panarchy (http://www.panarchy.org/depuydt/1860.eng.html), first published in French in the Revue Trimestrielle, Bruxelles, July 1860; Etymology of Panarchy, http://www.p2pfoundation.net/Panarchy_Etymology, from James P. Sewell and Mark B. Salter, "Panarchy and Other Norms for Global Governance: Boutros-Ghali, Rosenau, and Beyond", Global Governance, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 373-382, 1995;

4. Folke, C., 2016, Framing Concepts in Environmental Science Online Publication Date: Sep 2016, 10.1093/acrefore/9780199389414.013.8, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science; (Folke, C., 2018, The Beijer Institute of Ecological Economics, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences; Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University);

5. Berkes, F., Colding, J., Folke, C., 2003, Navigating social-ecological systems: Building resilience for complexity and change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK;

6. Holing, C.S., 2001, Understanding the complexity of economic, ecological and social systems, Ecosystems, Spinger-Verlag;

7. Biggs, R., Schlüter, M., Schoon, M.L., 2015. Principles for building resilience: sustaining ecosystem services in social-ecological systems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781316014240

8. Vitousek, M.P., Ehrlich, R.P., Ehrlich, H.A., Matson, A.P., 1986, Human Appropriation of the Products of Photosynthesis, BioScience, Vol. 36, No. 6, June, 1986, page 368-373, University of California Press, American Institute of Biological Sciences Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1310258;

9. Wahl, C.D., 2018, Building Capacity for the Re-design of our Economic Systems, Gaia Education, 16 March, 2018;

10. Daly. E.H., 2017, Sustainable Growth: An Impossibility Theorem, Gaian Economics: Living Well within Planetary Limits, Second volume, Gaia Education, Four Keys to Sustainable Communities series; https://medium.com/@gaiaeducation/sustainable-growth-an-impossibility-theorem-d78178dcac9c;

11. Brundtland et al, 1987, Brundtland Commission, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=BrundtlandCommission&oldid=847324915;

12. Norberg-Hodge. H, 2007, The Economics of Happiness, Gaian Economics: Living Well within Planetary Limits, Volume 2, Gaia Education’s Four Keys to Sustainable Communities series; The Economics of Happiness By Helena Norberg-Hodge Printed in Resurgence magazine 2007; http://www.skalaecovillage.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Gaian_Economics.pdf#page=162;

13. Korten, D., 2006, The Great Turning: From Empire to Earth Community, Berrett-Koehler Publishers,2006; Gaian Economics, Volume 2, Gaia Education, Four Keys to Sustainable Communities series; Korten, D., 2006, The Great Turning: From Empire to Earth Community, Ready for a Change?, The Case for Earth Community, YES! A Journal of Positive Futures Summer 2006 17, 206/842-0216, www.yesmagazine.org;

14. Lumber R, Richardson M, Sheffield D, 2017, Beyond knowing nature: Contact, emotion, compassion, meaning, and beauty are pathways to nature connection, PLoS ONE 12(5): e0177186. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177186;

#appliedcomplexityscience; ecosystem; systemscience#fuadudemans; c-institute; thegoldenthread; universality; Economics; Socio-economics; Poverty&Wealth; self development; cyberiagroup;

0 notes

Text

Cartographic clout (part 2 of 3)

The basis of critique or critical theory, is an effort to emancipate society from various forms of repression1, 4 (e.g. paradigms like capitalism versus communism; or by techno-centricity; or consumerism, etc.). Critical theory can be said to battle ruinous and flawed strategies, by emancipating society from repressive power structures1. Similarly, Kant and Foucault also see critique as being an attitude or philosophical behaviour that recognise how all knowledge, including scientific rationality are founded and enabled by power relations. Cartographic critique thus put the same emphasis upon mapping or cartography1, requiring us to be reflective in our practice of using maps. Some propose that map design be seen as a reflective conversation between the designer (map maker) and situation (context)3. This view sees the map as a device that lends insight to a reflective dialogue protocol (map-maker and map-user bias)3. There are a variety of transdisciplinary mapping models that contain systemic influences, like: Process blueprints, Journey maps, Synthesis maps, and gigamaps often used when dealing with complex problems4. Systemic type maps surpass traditional linear, static-type models or infographics as they are designed to reveal the wickedness and entanglement of complex systems. It provides options to stakeholders, allowing them to consider the future evolution of systems. In other words, systemic maps are heuristic and developmental in nature4, as they reveal the emergent dynamics of intervening in complex systems1. As an example, synthesis mapping follows a clear method to develop processes and relations, that

are vital to stakeholders, enabling them to make educated systemic choices. It also helps to define challenges and thus solution architecture options, be it for natural, social, or technological systems. Synthesis maps integrate research evidence, systems expertise, and design into visual stories that support communication and decision making4.

Systemic approaches connect the complexity across perspectives and knowledge domains, facilitating integration via shared understanding. It allows for the exploration of alternative solutions, which are useful in aiding multidisciplinary requirements associated with complexity science and socio-technical systems thinking1, 4. Project interveners or designers are often required to frame and communicate on behalf of collectives, a range of issues that stem from complex challenges. Today, such collaboration across specialist areas and domain knowledge are more common than ever before, making such skills an increasingly important element in solving complex challenges. Besides, developing products, services, and technologies for complex and increasingly instrumented society, require us to understand how technological advancements impact systemic integration. Importantly, Governments require such expertise to resolve their complex challenges3, and to introduce systemic efficiencies across service delivery in the public sector1 (e.g. education, health, urbanisation, and a host of socio-technical areas).

References

1. Udemans, F., 2008, The golden thread: escaping socio-economic subjugation: an experiment in applied complexity science, Authorhouse UK;

2. Barness, J., & Papaelias, A., 2015, Critical making: Design and the digital humanities, Visible Language 49.3, the journal of visual communication research, special issue, December 2015;

3. Schon, D., A., 1984, The reflective practitioner, New York, NY: Basic Books Inc.;

4. Jones, P., and Jeremy Bowes, J., 2017, Rendering Systems Visible for Design: Synthesis Maps as Constructivist Design Narratives, Journal of design economics and innovation, Tongji University and Tongji University Press,

Elsevier B.V., http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/;

5. Kanarinka, 2006, Art-machines, Body-ovens, and map-recipes: Entries for a psychogeographic dictionary, Cartographic perspectives, Number 53, Winter, 2006;

6. Wikipedia, 2018, Mercator projection, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Mercator_projection&oldid=862917060;

7. Firth, R., 2015, Critical Cartography, https://theoccupiedtimes.org/?p=13771, The Occupied Times of London (27), Retrieved 16 February 2018;

8. Sevaldson, B., 2011, Giga-mapping: Visualisation for Complexity and systems thinking in design, Conference Paper, June 2011, ResearchGate;

#critical theory#fuadudemans; c-institute; thegoldenthread; universality; Economics; Socio-economics; Poverty&Wealth; self development; cyberiagroup;#appliedcomplexityscience; ecosystem; systemscience

0 notes

Text

Cartographic clout (part 1 of 3)

The importance of visualisation as a decision support and educational tool is obvious having been employed across knowledge domains like illustrations in biology, GANT charts in engineering, GIS applications, etc. It is reflected in education and practice in different contexts, be it a place; culture; a situation, or an artefact. We have all been enriched through visualisations, mapping method advances across fields, allowing the contexts to be clarified in new and inspired ways.

Critical cartography or mapping theory suggest the map to reflect more than reality, since it shapes our view of the physical, political and social worlds2. Cartography is a powerful instrument, affecting all who encounter the map2, be it layperson; researcher; analyst; technologist; capitalist; politician; historian; etc. The economic and political potency of maps are well illustrated in an early world map, the Mercator projection, consciously and subconsciously affecting our view of the world and its peoples. The map (by Gerardus Mercator, 1569), become the standard map projection for nautical navigation. Even today most electronic maps (Yahoo, Quest, Google, etc.) use variations of Mercator projection (Web Mercator)6. The challenge is Mercator projections distort the size of objects as it moves away from the equator. This causes certain land masses to appear much larger than others (e.g. Europe appears larger than Africa, despite Africa being 3 times larger; Brazil is 5 times bigger than Alaska, yet it appears bigger)6.

Despite these misrepresentations, Mercator

remained the

most common projection used as world map, consequently reinforcing falsehoods that influence people's view of the world. For example, seeing Europe and North America, as larger and more important than other regions. These map types (cylindrical projections), were denounced in 1989, as general purpose world maps6. This is an example of critical cartography (a set of mapping practices ground in critical theory), that sees maps as reflecting and perpetuating relations of power, usually in favour of a dominant group7. Maps and visualisations are then seen as cognitive artefacts, since they reinforce, complement

and strengthen our understanding. It is a critical tool in the creation and communication of knowledge2, being usefulness in complex contexts1, allowing for abstracting and visualisations that support abductive reasoning2 (hypotheses based upon incomplete information). From a systemic perspective mapping practices touch upon both theory and practice, allowing us to illustrate complex subjects, whilst also diffusing knowledge. However, like most practices, cartography must also include reflexivity1 or reflection in action3. This refers to the importance of reflecting upon what are offered, and to exercise critical reflection. This is vital in cartography, due to its potency as a tool - i.e. a map’s power, able to affect cultures, economics, and politics, whilst conceding the human propensity of bias (non-neutrality)1. The potency of maps as social and cultural constructions affects us all, which require both map-maker and map-user to appreciate these affects across society at a multiplicity of scales and a diversity of contexts. Since maps make the complex accessible and knowable, it is appealing to a range of disciplines outside of geography, thereby demanding that we strive toward a middle-ground between the positivist perspective of mapping (as truth-seeking tool), and an interpretivist paradigm (construct only)2. An indispensable quality of maps are their value in organising and blending vast amounts of data by depicting systemics of patterns and connections. Despite such value, we must always be cognisant that maps are abstractions of reality; a synthetic image that can never contain the richness of real-life (the map is not the territory). We must remember that when we process, organise or translate data into images, we invariably edit data via selection and omission strategies. This selection and removal of specific data, must always be reflected upon as map-makers and map-users. It refers to the implicit assumptions or judgements (bias) contained in the acts of omissions and deletions. In other words, the process of inclusion and exclusion reveals: the who, the what, and the why in any rendering2. As an example, using a search engine to search a topic yields a variety of results. When we use such results, we often forget that it has already been affected by the search engine’s criteria for sorting, grouping, and framing, i.e. shaping which data are included or excluded in our search results. The growing popularity of mapping practices demand a greater literacy of its underlying systemics, i.e. the non-neutral processes of map-making and the vitality of reflective practice1, 2. This forms a vital aspect of critical cartography, which challenges mechanistic cartography by linking geographic knowledge with power5.

Critical cartography sees maps as tools of oppression and power, having been historically produced by and for the ruling class7. To counter this, critical cartography introduced new mapping practices that challenge formal maps of the State7, adding alternate insights (e.g. indigenous cartographers) to Western versions. As example, there were no maps of the Americas, and versions developed by occupiers thereby defined the political, economic, and cultural trajectories. These maps made Western conquest and empires legitimate, exporting their beliefs, customs and practices, which continue until today.

References

1. Udemans, F., 2008, The golden thread: escaping socio-economic subjugation: an experiment in applied complexity science, Authorhouse UK;

2. Barness, J., & Papaelias, A., 2015, Critical making: Design and the digital humanities, Visible Language 49.3, the journal of visual communication research, special issue, December 2015;

3. Schon, D., A., 1984, The reflective practitioner, New York, NY: Basic Books Inc.;

4. Jones, P., and Jeremy Bowes, J., 2017, Rendering Systems Visible for Design: Synthesis Maps as Constructivist Design Narratives, Journal of design economics and innovation, Tongji University and Tongji University Press,

Elsevier B.V., http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/;

5. Kanarinka, 2006, Art-machines, Body-ovens, and map-recipes: Entries for a psychogeographic dictionary, Cartographic perspectives, Number 53, Winter, 2006;

6. Wikipedia, 2018, Mercator projection, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Mercator_projection&oldid=862917060;

7. Firth, R., 2015, Critical Cartography, https://theoccupiedtimes.org/?p=13771, The Occupied Times of London (27), Retrieved 16 February 2018;

8. Sevaldson, B., 2011, Giga-mapping: Visualisation for Complexity and systems thinking in design, Conference Paper, June 2011, ResearchGate;

#fuadudemans; c-institute; thegoldenthread; universality; Economics; Socio-economics; Poverty&Wealth; self development; cyberiagroup;#systemic maps; systemic tools

0 notes

Text

Mechanical megalomania (part 2 of 3)

Last we noted that, systemic developmental principles require robust and resilient solution frameworks having greater transparency, governance, equality and empathy, built-in1. In other words, a more aggressive Panarchy - which is a form of governance that encompass all others3 - universal or global governance4. It is suited for governance of trans-disciplinary, networked cultures, with intersecting concepts of ecology, technology and politics being accommodated. It draws from information theory, network theory, economics, sociology and complex systems5. Systems theory in turn, is an interdisciplinary field of science that studies the patterns or nature of complex systems of the physical world1. Researchers from this domain use the term as an antithesis to the word hierarchy6, suggesting it to be a superior framework based upon nature's rules6. This too is therefore seen as cross-disciplinary since it cuts across many types of systems and specialist areas1.The rural-urban migration challenge uses the notion of urban resilience, suggesting Cities in themselves are complex adaptive systems, containing many sub-systems like production systems, energy systems, road systems, suburbs, people, trees, etc. These sub-systems function together to give each City its unique features, which include resilience. Resilience thinking adopts an integrated systemic view of humans and ecosystems7. It has been used to describe the period it takes for a system to return to equilibrium, after being disturbed9. Integrating socio-ecological system needs have yielded four principles to build adaptive capacities8:

· Accept change and uncertainty as inherent to life;

· Embrace diversity or Variety for regenerative functions;

· Combine different types of knowledge for enhanced learning;

· Promote social-ecological sustainability;

Today’s pervasiveness and scale of connectivity create greater complex dynamics across domains7, which in turn influences counter-intuitive outcomes. The inability to observe these systemics, are directly related to our linearity in thought and practice that produce rigid, blind institutions, unable to halt skewed developmental outcomes1 whilst increasing vulnerabilities of our global socio-ecological system9. It is clear that our limitations regarding predictability are ill-understood and even ignored1. It may be linked to advances and widespread availability of information, giving false comfort in our actual scientific capacities to deal with unpredictability and change, thus making people more vulnerable to it1, 14. This can be seen in the current abuse of AI whereby unsuspecting consumers are rallied and marshalled into something they don’t truly understand. In truth we have been warned for centuries12-14, about fads and consumption that disallow genuine efforts of sustainable living7, 8. These fads feed our excessive leisure lifestyles at the expense of the ecosystem we rely upon for our very survival7,8. Only a mechanically driven, linear disposed minds can produce such great negative effects, and continue on its destructive trajectory – i.e. a mechanical megalomaniac?

References:

1. Udemans, F., 2008, The golden thread: escaping socio-economic subjugation, an experiment in applied complexity science, Authorhouse UK;

2. Vanbergen, G., 2017, The crises of trust in Democracy & Globalisation, The European Financial Review, July 26, 2017, http://www.europeanfinancialreview.com/?p=1726; Smith, J.W., 1989, The World’s Wasted Wealth: the political economy of waste, New World’s Press, 1989, pp.44,45;

3. de Puydt, P.E., 1860, Panarchy (http://www.panarchy.org/depuydt/1860.eng.html), first published in French in the Revue Trimestrielle, Bruxelles, July 1860;

4. Etymology of Panarchy on P2pFoundation.Net (http://www.p2pfoundation.net/Panarchy_Etymology) quoting from James P. Sewell and Mark B. Salter, "Panarchy and Other Norms for Global Governance: Boutros-Ghali, Rosenau, and Beyond", Global Governance, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 373-382, 1995;

5. Hartzog, P.B, 2008, "Panarchy: Governance in the Network Age" (http://panarchy.com/Members/PaulBHartzog/Papers/Panarchy%20%20Governance%20in%20the%20Network%20Age.pdf)Archived(https://web.archive.org/web/20070928104543/http://panarchy.com/Members/PaulBHartzog/Papers/Panarchy%20%20Governance%20in%20 the%20Network%20Age.pdf) 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, Master's Essay, University of Utah at Panarchy.com.

6. Island Press Bookstore description of Gunderson and Holling's Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Systems of Humans and Nature, (http://www.islandpress.com/books/detail.html?SKU=1-55963-857-5&cart=%5B cart%5D); and Gunderson and Holling, Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Systems of Humans and Nature (http://ww w.resalliance.org/593.php), Chapter 1, p.5, reproduced at Resalliance.org;

7. Folke, C, 2016, Framing Concepts in Environmental Science Online Publication Date: Sep 2016, 10.1093/acrefore/9780199389414.013.8, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science; (Folke, C., 2018, The Beijer Institute of Ecological Economics, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences; Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University);

8. Berkes, F., Colding, J., Folke, C., 2003, Navigating social-ecological systems: Building resilience for complexity and change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK;

9. Holing, C.S., 2001, Understanding the complexity of economic, ecological and social systems, Ecosystems, Spinger-Verlag;

10. Kates, R.W., and Clark, W.C., 2010, Environmental Surprise: Expecting the Unexpected? Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, Volume 38, 1996 - Issue 2, Pages 6-34 | Published online: 08 Jul 2010

Pages 6-34 | Published online: 08 Jul 2010, Download citation # https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.1996.9933458;

11. Annan, K.A, We, the Peoples: The Role of the United Nations in the 21st Century (United Nations, New York, 2000), www.un.org/millennium/sg/report/full.htm; National Research Council, Board on Sustainable Development, Our Common Journey: A Transition Toward Sustainability (National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 1999), www.nap.edu/catalog/9690.html; R. Watson, J. A. Dixon, S. P. Hamburg, A. C. Janetos, R. H. Moss, Protecting Our Planet, Securing Our Future (United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, 1998), www-esd.worldbank.org/planet/;

12. Tokar, B., 2008, On Bookchin’s Social Ecology and its Contributions to Social Movements; Capitalism Nature Socialism Volume 19, Number 1;

13. Tawney, R.H., 1920, The Acquisitive Society, Quotes taken from the 1920 edition (http://gutenberg.org/ebooks/33741), published by Harcourt, Brace and Company; and, Tawney, R.H., 1960, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R._H._Tawney;

14. Brown, H. (1954). The challenge of man’s future, Engineering and Science Vil.17 (6), pp.22-32, Caltech office of Relations; http://resolver.caltech.edu/CaltechES:17.6.brown; Available: Folinsbee, R. E., and Leech, A.P., 1974, Energy – Challenge of man’s future (Part I). Journal of the Geological Association of Canada, Vol. 1 (1);

0 notes

Text

The thrust of trust (part 2 of 3)

Western nations have experienced massive losses in trust4, 6, with public confidence crashing to 13% of Greek, 30% of Spanish and 28% of French citizens having trust in their respective governments4. The OECD has called upon governments to win back citizen trust, which is essential if the State is to have people pay taxes, obey rules, comply to regulations and the law. The more people trust the State, the more they are likely to invest and spend in economic activity. Most importantly, trust is essential in times of sacrifice, like say austerity measures and ultimately, war.

High levels of trust are considered beneficial to society in general, which include a critical and questioning disposition forming a healthy layer of critique and protection. This mistrust is really a questioning temperament that motivates people to engage in politics5 - a counter-weight ensuring equality and fairness. Loss of trust stem from corrupt practices as it opposes the four aspects that underlie trust5: Corruption undermine efficiency and effectiveness of parliamentary rule; Corruption infers a lack of moral code without care for citizens; Corruption thrives off institutional limits; Corrupt societies are deemed unreliable (uncertainty in outcomes due to lack of assurance and standards)5. Corruption is thus the antithesis of trust – indeed research recognise a negative reinforcing cycle whereby corruption breeds distrust, which in turn feeds corruption5, 1.

As noted, the 2017 Trust barometer revealed the alarming level of distrust people have toward business, government, media, and NGO’s6. This should not come as a surprise since we have been highlighting the systemic subjugation of global citizens through these very structures. The trust barometer is simply another indication of citizens being and expressing their resentment toward institutional and structural corruption across key agencies as well as the leadership that occupy them. The need for empathetic and especially systemic orientation is well overdue as continued institutional failure can only result in collapse. Rebuilding trust is not an option, but a needed act in order to restore systemic confidence and faith. Agencies and institutions can only become relevant again, if they genuinely serve the people as a priority. Trust is vital for reasons like: Public policies that depend on behavioral compliance (e.g. paying tax); Investment; Consumer confidence; Economic and financial activities (e.g. banking services). Importantly, if people believe that elected officials are not playing by the same rules, they too will “game the system”, degenerating into an “every-man-for-himself” system. It is the negative feedback loop noted earlier when citizen’s view their government as corrupt they too, will start to cut corners. It would seem the crimes of those having power, have eventually resulted in a steady decline in global trust7. Citizens from various societies believe the overall system to be broken and unable to function effectively7, they mostly have contempt and require no further evidence of corrupt and inept leadership. The result is desperate reactions expressed in: extreme politics, like Brexit, the US election choices; institutional corruption with fake news and corporate deceptions. It reveals backward and selfish positions being adopted as last resort attempts to bolster trust7.

References:

Udemans, F., 2008, The golden thread: escaping socio-economic subjugation, an experiment in applied complexity science, Authorhouse UK;

2. Dalton, R.J., 2005, The social transformation of trust in government, International Review of Sociology, Volume 15, No. 1, March 2005, pp. 133 /154;

3. Mahmoud, Y., 2014, Pervasive disconnect between state and citizen offers two paths: Promise or Peril, International Peace Institute Global Observatory, June 16, 2014;

4. Alex Gray, A., 2017, A question of confidence: the countries with the most trusted government, World Economic Forum, Formative Content, 15 November 2017;

5. Van der Meer, T. and Dekker, P., 2011, Trustworthy states, trusting citizens? A multi-level study into objective and subjective determinants of political trust, In: Zmerli, S., & Marc, H., Political trust: Why context matters. Colchester: ECPR Press (995116);

6. Edelman Trust Barometer, 2017, http://edelman.com/research/edelman- trust-barometer-archive;

7. Vanbergen, G., 2017, The crises of trust in Democracy & Globalisation, The European Financial Review, July 26, 2017, http://www.europeanfinancialreview.com/?p=1726;

8. Vavreck., L., 2015, The Long Decline of Trust in Government, and Why that can be patriotic, NY Times, The Upshot, July 3, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/04/upshot/the-long-decline-of-trust-in-government-and-why-that-can-be-patriotic.html;

9. Stannard, M., 2016, From Wall street schemes to Debtor’s prisons: cities confront regressive debt collection, Public Banking Institute, March 26, 2016;

10. Smith, J.W., 1989, The World’s Wasted Wealth: the political economy of waste, New World’s Press, 1989, pp.44,45;

#fuadudemans; c-institute; thegoldenthread; universality; Economics; Socio-economics; Poverty&Wealth; self development; cyberiagroup;#design thinking#systemsscience#complexityscience

0 notes

Text

Your governance needs you (Part 3 of 3)

We ended last week by noting that sound democracies require empathetic insights and systemic leadership in order to create equitable social systems1. Without these, societies will remain unable to adequately understand, interpret and design empathetic solutions. Keeping this in mind, and looking at how governance and compliance are clandestinely abused at even the highest levels, where developed nations dominate developing nations are now common features.

Today, when empathetic public participation and accountability are known to be foremost, we still have a minority of countries, exerting greater control than all the others combined, regarding the governance of global affairs3. Like the G5/G7 group of nations having far greater powers than all of the G24 and/or G773. Imagine, in today’s inter-connected world, that only 5 countries have the arbitrary privilege of permanent membership and veto power in the UN Security Council3. This is almost comical, were it not for the fact that we rely upon these institutions for creating global equality, fairness and safety3, 4. This same oppressive dominance is evident in both the WTO and IMF1, 3, who both punt preferred structural and procedural processes that benefit a minority. It is then clear that the agents and agencies already enjoying advantage, (e.g. the financiers, the industrialists, the professionals) shape both the agenda and governance of global developmental themes1, 3. It is a highly mechanistic management class with closed networks and no empathy nor aspiration to counter negative outcomes of current models1, 3, 4. Current institutional models have superficial attempts at inclusivity, and continue on a path of destructive development by smartly limiting the possibility for pluralism3. This mechanistic globalisation does not permit environmental nor democratic expansion, as it has no systemic governance & accountability, as reflected in key areas of: climate change, financialisation and militarisation3. As it stands today, global governance still reflect a minority dictatorship without rights to the majority. There is no real consent, no consultation, no empathy, no inclusivity - current global affairs are more conducted on the basis of ignorance, neglect, exploitation, and coercion – a stock feature that Noam Chomsky refer to as “engineering consent”. As such, the need to have empathetic structural features embedded in modern society, are vital if we are to create an improved egalitarian global community1, 7.

References:

1. Udemans, F., 2008, The golden thread: escaping socio-economic subjugation, an experiment in applied complexity science, Authorhouse UK;

2. Crook, C., 2001, The economist, Special report: Globalisation is a great force for good, but neither governments nor businesses, can be trusted to make the case, September 27th, 2001;

3. Pooja A., 2013, Inequality between countries due to globalisation, Political science notes, Creative Commons License, Copyright, 2013;

4. Claessens, S., & Kodres. L., 2014, The regulatory responses to the global financial crisis: Some uncomfortable questions: IMF working paper; Research department and institute for capacity development;

5. Stacey, R.D., 1995, The science of complexity: an alternative perspective for strategic change processes, Strategic Management Journal, 16: 477-495; Stacey, R.D., 1996, Complexity and creativity in organizations, San Francisco: Berret-Koehler publishers; Sherman, H. and Schultz, R., 1998, Open Boundaries, New York: Perseus Books;

6. Sanderatne, N., 2012, Imperatives for economic development, Economic summit bares the truth: Good governance key to economic development, The Sunday Times, Sunday, 22nd July, 2012;

7. Hudson, A., 2018, What we did, what difference it made, and what we learned, Blog, February 2018, Global integrity, http://www.globalintegrity.org.uk;

0 notes