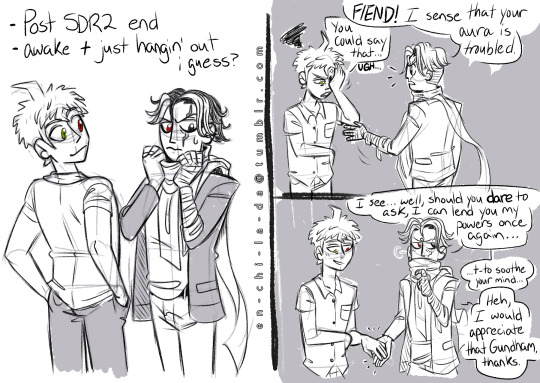

#get their bearings/memories back and attempt to recover from the despair they experienced/caused but they dont leave the island yet

Photo

anon, i like how you said “consider a positive to the last ask” and then still stuck with the night terrors idea lmao. anyways here’s these gay doodles

#took me a while to answer this one lmaO i got carried away i guess :)#danganronpa#i am posting this on my lunch break AS WE SPEAK ill have to come back and tag this more later!#sdr2#hinadam#ari art#ask draw#ok im back UH the first pic was just for the setting i guess like. hajime + the others slowly working together to wake the others up and#get their bearings/memories back and attempt to recover from the despair they experienced/caused but they dont leave the island yet#they all just hang out lol#and like YEAH hajime may be the Ultimate Ultimate but he would still need help and support and his friends adn 🥺#a night terror is still a night terror so its always nice to have another presence there to help you#even if youre a multitalented super genius lab experiment or an animal loving dark lord of ice :)#alright me go back to bed bye#gundhamronpa

320 notes

·

View notes

Text

A slightly-more-lenghty-than-usual thing about Anson’s background, a little more.

Night falls in Drapers Ward, cool and deep, and Anson is closing up shop. The coins are placed in their lockboxes and the books are balanced. All is hushed save for the whisper of the broom and his own tuneless humming as he sweeps away the dirt and stray threads. The space is lit only by the dim glow of the display lights in the window. Pleasantly warm, it glints off the silk ribs and silver clasps of the corsets stationed there. The man straightens up to survey the meticulous front room, ready for the next morning, and then pulls the keys from his pocket. They’re a comforting weight in his hands. They always have been, from the very first time they fell into his palm, when, buoyed by the handsome bills incurred by his first real client, he was finally able to rent the space. He would always regard that client fondly for her initial help.

1842. Emma Lytton, an oil heiress looking incongruously pretty amidst the blood and grease she surveyed at Slaughterhouse Row. Anson had met her on his supply run to the foul district. She seemed just as intrigued by his own contradictory appearance among the marine gore, sharply dressed with a bundle of whalebone tucked beneath his arm.

Anson was happy to talk of his work, and she was happy to listen.

She commissioned three corsets from him over the course of several months. Still working out of his crumbling apartment, without a true space to receive customers, he traveled to her opulent home to fit each one. The third was a ‘conversation piece’—one that would bear the carvings Anson copied from a rune found many years ago. The work would be the first of its kind, Anson’s clandestine idea finally made a reality.

He remembered measuring it for her as she murmured compliments to him about his craftsmanship. He remembered her reaching down as he was laying pins at her waist, spreading her fingers across his own and then guiding his hand up to her breast. A startled but excited lurch thrummed through his viscera, and even after her touch languidly brushed away from his, he didn’t pull his hand away from where she had left it.

With a sigh Anson steps out into the night and locks the door behind him. His fingers linger on the doorknob as he lifts his eyes to the sign above. A. Lydstern Corsetry proudly gleams in a gilded script. The surname was that of a wealthy textile merchant who had emigrated from Karnaca. Gone by the plague, it was printed in the death notices for Anson to deftly steal for himself, to pose as a son living overseas during the tumultuous time. There was no other family around to contradict him. Now, ‘Lydstern’ feels more at home upon his tongue than his birth name ever did. He lets his hand drop from the door.

“We need to get you your own shop, lest I distract you again from your work.” Ms. Lytton said to the ceiling with a slight laugh, once their sweat cooled and their ragged breathing steadied. Anson was pulled from his reverie on whether or not he liked the feeling of silk sheets to look over at her. She continued. “I’m planning on sending more business your way, and it won’t do to have you traipsing all over Dunwall to meet them. You’ll exhaust yourself in no time.”

“I have excellent stamina.” He said.

She laughed loudly and deeply enough to injure his pride before turning back to him.

“You’re experiencing a lot of firsts lately, Mr. Lydstern, and I know it, so I hope you don’t mind my advice. You need to lay your name on some bricks rather than being this…traveling tailor. It doesn’t look respectable, no matter who your father was.”

“I know I need my own shop.” Anson crossed his arms behind his head. “I already have the space picked out.”

He smiles wistfully at the storefront before tucking the keys back in his pocket and turning to the street. He still sees Emma from time to time, in a professional capacity during the annual parties she throws. But those parties are a long way off in the pages of his calendar. The ‘X’ he had drawn through the day that morning marks something else that is leaving him sentimental.

A chill breeze trembles through the leaves overhead, letting pools of moonlight shine through, shift, close, and reappear again across the dappled ground he walks. His path winds away from his usual route of the peaceful, orderly stretches of Drapers Ward that lead to his home. Instead, he traces an older path: one that he hasn’t followed in years. His footsteps move along the edge of the canal, drumming across the metal bridge that extends over it. When he reaches the other side he throws a glance back at the arcade. Upon seeing it from that once-familiar vantage point, he suddenly feels himself standing in shoes a bit more ill fitting, with a sickly hunger twisting in his gut and a few less lines etched on his face.

1840. The two heavily tattooed men had blocked his path for the third time that week. But rather than caving inward as he did before and passively turning out his pockets when their shadows fell upon him, the young man was struck with a shaking rage. Anson roughly set aside the dress form he had been carrying around all morning and marched up to the pair.

“I’m sick of you.” Anson spat. “I’m sick of all of you, standing around like vultures when I’m trying to—” He flung his arms to gesture to the boutique market across the canal, voice breaking in exasperation. “—trying to do something.”

He had been attempting, quite desperately, to sell his work in the street as Drapers Ward slowly rose from its ruin, with little success. Between the store owners calling the City Watch to chase him off for solicitation, and the Dead Eels lingering at his back with the hopes of a shakedown and therefore scaring off any potential customers, Anson was scrabbling.

One of the Eels arched his eyebrows as he looked down at the reed of a man.

“Is that really the tone you wanna take with us?”

Anson aggressively pointed at the man’s face.

“I’m not going to do this anymore. I’m not going to just, just GIVE you everything I work for while you fucking bastards sit th—“

The Eel interrupted Anson by smacking his accusatory finger away with one hand, and delivering a stunning blow to the younger man’s face with the other.

Anson collapsed, feeling the chill of the mud against his back and the sharp taste of copper in his mouth. He didn’t have time to recover before he was doubled up with a barrage of well-timed kicks. He drew his elbows in to protect himself, but not before hearing something crack, feeling something crack in his side. Then the two men pulled away. With a wheezing, agonized moan he rolled onto his back, hands clasped to his bleeding face. Through the painful haze there was the dim sensation of someone rifling through his pockets to take what little he had left. One of the two men delivered a final kick to his sufficiently pummeled midsection before the pair stalked off with their meagre spoils.

It wasn’t so long ago that he was spitting blood and teeth in the alley muck, clutching a fractured rib that still aches in the cold to this day. He regards the view across the canal bitterly before continuing on his way, into the parts of the neighborhood where the shadows seem to fall heavier.

He always thinks it strange how the streets change in such a short distance across the canal. Similar to how the warm shallows of the river so quickly plunge into ice. Though the plague is long since gone, what happened in the city can never be extricated from its foundation, no matter how extravagant the neighborhood grows. The memory of it settles into the brickwork, and swells back to him as he moves down the darkened alleyway.

1837. The hoarse groan trailing from the dark space between the buildings stilled Anson’s usually fast pace. Perhaps it was curiosity, perhaps fear, that caused him to pause and stare at the bowed figure staggering in the alley. She was clothed in rags and her fingers dug between the notches of her ribcage, as though she were trying to hold her shambling body together. A cloud of flies swarmed about the woman’s hanging head, their brood burrowing in her slack, discolored skin. Ropes of black bile hung from her jaw, and she lifted her unfocused eyes to Anson. There was a strange glassy quality about them, encircled with dried blood. Her movements then jerked with an eerie alertness when she seemed to notice him and, realizing the danger he had put himself in, Anson ran.

Now he strolls through the ever narrowing streets. The rats remain, but the plague no longer lingers in their bite. While the same buildings that Anson remembers still stand, and the same ads peel upon their bricks, something about his old part of the neighborhood feels different now. More windows burn brighter, more muffled conversation seems to spill out into the streets, and while each building undoubtedly holds its fair share of sorrow, they don’t seem to sag with the impermeable despair that weighed upon them during the plague years.

“I saw a weeper.” Anson said to his father when he came into the apartment. He was still jittery from the encounter, muscles tense. He violently shut the door behind him and turned every lock. His father glanced up from the sewing machine, which had seen considerably less use the past few years. He looked more ashen than usual. Tired. The city was taking its toll.

“Why are we still here?” Anson asked irritably. Fear had made him snappish. “Everyone else has left.”

“Everyone who can.” His father corrected.

Anson’s pace slows as he approaches the building he grew up in. Five stories high, fire escapes leaning to and fro across the face of it. A single dim lantern burns above the arched doorway. His gaze drifts upwards to the windows of his old apartment and a cold, nauseous sadness runs through him.

The next morning, Anson woke before his father, and he immediately knew something was wrong. Never in his life had he been woken by the sunlight falling in through the window. It had always been by his father’s gruff voice, in the cold early hours, before the rest of the world rose.

He already assumed the worst as he cautiously approached the waxen-looking imitation of his parent, still lying in bed. No breath touched the palm Anson held beneath his nose and no pulse came to his fingertips.

When the City Watch dead counters came, Anson was smoking on the fire escape. He heard the door open, but not the footfalls of their approach and, agitated, Anson looked over his shoulder. It was only a brief glance. He didn’t want to see his father’s corpse again.

The two counters stood anxiously in hallway in their face masks, clearly afraid to step over the threshold. Anson hated them. He hated everyone at his back, dead or alive. He hated the counters’ cowardice. He hated that his father abandoned him, orphaned him. He hated the sun for shining, for waking him that morning.

“It wasn’t the plague.” Anson said shortly, and then turned his head away. He took a long final drag on his cigarette before casting it over the edge and scowling up at the sky. “He had a bad heart.”

When he didn’t hear the men immediately enter the room at that statement, he spoke up again.

“So you can come in now.” The sharpness of his tone seemed to spur them into action and he heard their boots on the floorboards.

Anson closed his eyes and held the fire escape railing in a white-knuckled grip to keep his hands from shaking. He heard the rustle of fabric as the counters unceremoniously rolled the dead man up in his bedsheets. A labored grunt as they hefted the body up. The thud of someone or something clumsily bumping into the doorframe. And then the door shut. The footsteps faded. Anson sagged against the railing and let out the wrenching sob he didn’t know he had been holding in.

The corsetier lingers at the front door of the building, beneath the ghastly flickering lamp that traces every unflattering hollow on his face. He reaches out to open it, and then closes his fingers into a fist and draws his hand away. He is a stranger to this place now. He feels himself pivot from the building, ready to head back to his true home…until he realizes that his ‘true home’ has only been his for eight years. The other twenty five played out behind the door he hesitates in front of now. This is still his home as much as anyone else’s and, setting his jaw, he pushes open the door.

The front has always been unlocked, and as a result the hallway has always been an extension of the street. A wall of suffocating darkness comes out to meet him. Even after all these years, the building still has no lighting in the hallway. There is no candle flickering by the steps, as his father used to leave out for him, and as he used to leave out for himself when his father was no longer around to do so. This almost makes him turn his back on the building for a second time. Instead, he feels the weight of the lighter in his pocket, and he takes it, fumbling until he can get a feeble flame raised. It barely penetrates the dark, but it will do. He takes a breath, and steps over the threshold.

1835. Anson was returning from a delivery from his father when he realized the front door of the tenement was thrown open. All of the city was allowed to spill in, if it wanted to. He stood in the frame of it, cagey and quiet, before stooping to pick up the stub of a lit candle left there for him.

The hallway and its darkness had always scared him, but with the fall of Drapers Ward came a valid reason to be afraid. The plague had torn the heart out of the district, the neighborhood gangs were at open bloody war with each other for what was left of it, and the dark had more horrors to hide than ever.

He stepped into the narrow entryway. The dying candle threatened to burn his hands as it sank lower. Inelegant animal grunts came from the back of the hallway, some pair who had tumbled into the building in search of a sheltered wall to fuck against. Anson felt his face grow hot, his grip on the candle tighten, and he quickly made his way up the stairs.

As he came up on the second landing, the light played across an unconscious form slumped against the wall. His hat brim was pulled low out of his eyes, and an olfactory evil composed of piss, vomit, and sour booze rose from him. Anson carefully sidestepped the man’s outstretched arm, where a bottle still lay between his loosely curled fingers.

At the third landing Anson tripped over something soft but solid. The candle nearly toppled from its holder as he fell forward, and he braced one palm against the wall to catch himself. Once he regained his composure he timidly extended the candle. In his stumbling, he had nearly stepped in the gore that gleamed at his feet. The tangled ribbons of a man’s entrails sagged across the floor, belly split with a flensing knife. The Eels had a way of cutting into men like some of them once cut into whales. The fellow had climbed a long way to die in secret.

Anson finds no such things in the hallway this time. He likely wouldn’t have made it up to the fourth landing, otherwise. On this floor the darkness is cut just slightly by a thread of light spilling from beneath the door of the apartment. He feels a jolt of surprise at seeing it before reeling back and criticizing himself. Of course there is someone else living here. People don’t stop living in this neighborhood just because he does.

Walking carefully to muffle his footsteps, he approaches the door that was once his own. He splays his open palm against it, touches his forehead to the splintering wood, and wonders what he would find there, if he were to open it.

1831. The sewing machine greeted him as he stepped into the room. The view outside the window was reflected in miniature in its gleaming black surface.

“We’re getting more contracts now.” His father explained as Anson slowly approached the machine. “So it’s best you learn too. Sit.”

The chair creaked beneath the boy’s bird-like weight as he sat in front of it. He marveled at it, delicately tracing the curves of the machine as though it were a found treasure and not something that was going to make his work longer, more difficult. He had never been allowed to touch the older one, which still held its desirable senior position by the window.

His father leaned over next to Anson and took hold of the wheel at one end of the machine.

“Take your feet off the treadle.” He instructed. Anson did so. “Now,” His father continued. “The wheel turns towards you, you see?” He gently spun the wheel counter-clockwise with his hand, and Anson, rapt, nodded silently. His father pointed at it. “Always make sure it’s spinning towards you. The thread will break otherwise. Keep an eye on it all the while.” The boy gave his father another serious nod.

His father crouched down to be eye level with the machine and pointed at the treadle.

“Put your right foot on the far corner…left on the opposite end…yes, like so. Pull the wheel towards you with your hand, get it spinning. There. Rock your feet, right forward. Left back.”

The wheel whirred and Anson beamed as his father stood up straight again. The man almost smiled, squeezing the boy’s bony shoulder.

“You’ll be stitching soon enough.”

Anson, overly pleased with himself, broke the rhythm he’d established in his haste to pedal faster, and the wheel jerked and rolled back in the opposite direction.

“Ah, see. You would’ve broken the thread.” His father pointed out before walking away from him. “Keep at it.”

Anson’s memories are broken when he hears voices travel through the door. Startled, he jerks away. Then he calms himself and leans in to listen more carefully. Two children, having some sort of argument over which game to play before the distant voice of their mother intervenes. He slowly takes a step back, holding up his lighter once again. This is a different home now. There is a different life here. He has a different life now. He leaves the children to their argument, the mother to her management, and in his tiny circle of light he makes his way back down the stairs.

Once outside again, Anson meanders to the river’s edge in that bandy loose-jointed way that now characterizes all his movements. Gone is the rigid anxiety of boyhood, and the tensely wound anger of the plague years.

Stars puncture the sky, and the nightly breeze that had been following him all evening chases at his heels and ruffles the reeds and the ropes around him. The river sloshes high against the concrete sides of the piers, and Anson looks down into the depths of it.

He hadn’t been able to afford a proper burial for his father those years ago. Where his bones lie is still a mystery to Anson, so he chooses the river as the place for him. The man sits with his legs dangling over the edge, daring the water to touch the soles of his shoes. For a time there is nothing but the whisper of the current, the chill of the wind sinking into him, the silhouetted blocks of whaling trawlers moving out into open water. Anson simply sits and sighs.

After a time he reaches into his breast pocket to pluck a coin between two fingers. The first coin he’d made that year. He’d felt foolish for hanging on to it for all those months. He’d felt foolish all the way up to this moment. Now he doesnt feel foolish at all.

“I have no idea what you’d think of me…what you’d think of how I earned this.” He muses quietly, walking the coin across his knuckles. “But…I owe something to you, in any case.”

He balances the coin upon his thumb and then flips it as far out across the water as he can. With a bright ringing sound it glints up into the sky and then descends, falling noiselessly into the river. Anson braces his palms on his thighs and stands, head bowed, pulling a hand down his face. When he lifts his eyes again, he looks out to the point in the water where the coin had been lost.

“Happy birthday, dad.” He says to the river.

Then he turns his back on it, to return to the name he built for himself out of his joys and his sorrows.

#noncommittal hand waving#I don't like writing in present tense or bumping my tenses around but ehhhhh VAGUE HANDWAVING#charlatan corsetier#sj writes things

16 notes

·

View notes