#have dumplings in china evolved to this extent now???

Video

undefined

tumblr

crystal floral chinese dumplings jiaozi🥟

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Xi’an, China

Day 56 - Beijing to X’ian

We boarded our sleeper train at Beijing West Station in the evening - beginning our 16 hour journey to Xi’an, over a thousand kilometres Southwest of Beijing. The language barrier made for quite a challenge - with Christie and I running all over the massive station, trying to figure out how to collect our tickets. I later found out that Beijing West Station is the largest train station in all of Asia, typically serving over 150,000 passengers per day.

Finally found our platform!!

Fortunately, after a few days of being in China, we had quickly learned to give ourselves lots of extra time with any form of transportation! Having collected our tickets, we joined the throngs of people in the waiting area. Packed into every available chair and inch of floor space, many passengers were travelling with big cardboard boxes and stuffed rice bags. Loud announcements in Mandarin blared from overhead speakers, updating travellers on the constant stream of trains coming and going from the station.

Our sleeper compartment was shared with two other friendly Chinese women. Although we were unable to directly communicate with each other - between Google translate and a similar Chinese app, we were able to exchange a few simple pleasantries and smiles. The small bunks were quite basic, but comfortable enough for our long overnight journey. We secured our passports and valuables in our bags with a bicycle lock, settling down for the night as our train chugged South out of Beijing.

Day 57 - Xi’an

Arriving in Xi’an station mid morning, we walked to our hostel in the middle of the walled city centre. The city of Xi’an is one of the most ancient in China, steeped with thousands of years of Chinese history. Many early royal dynasties called Xi’an home, along with the first Emperor Qin Shi Hueng, who unified China over 2000 years ago by conquering states throughout the region.

In addition to being a capital of ancient civilization, Xi’an was also the terminus of the Silk Road trade route. Because of this important location in ancient trade, Xi’an has evolved over time as a city with an incredible mix of people, religion and culture. These influences continue to be reflected to this day in everything from the vibrant Muslim minority, to the fusion of Chinese and Western architecture seen throughout the city.

As we made our way through the historic city centre, we immediately noticed the poor air quality. Although warmer than Beijing, the winter season in Xi’an is known for the heavy blanket of smog that hangs over the city. Looking through the window of our hostel room, the city skyline was scarcely visible beyond a few blocks, hidden in the thick haze. I have never before experienced smog to the extent we saw in Xi’an, and throughout our entire stay in the city, we barely saw the sun.

Thick Smog over Xi’an

Dropping off our bags, we set out to explore the city. Our hostel was located in a wholesale/market neighbourhood of the city, with delicious coffee shops scattered throughout wholesale stores. (For the record, the coffee throughout China was consistently fantastic!) Walking along the narrow sidewalks crammed with scooters and bicycles, we passed wholesale vendors selling everything from engine parts, cookware and beauty products. At the end of our block, we were immediately greeted by the strong, unmistakeable smell of a fresh fish market, with every type of seafood imaginable on display in the open air.

In the centre of historic Xi’an, we traversed a chaotic, multi-lane roundabout to visit the ancient Bell Tower. Over 600 years old and built in the Ming Dynasty, the tower was named for the 6.5 ton bell within, which historically was rung to tell time or to raise an alarm in the ancient city. The classical Ming architecture in the tower was reminiscent of the Forbidden City, with green-tiled eaves and red decorative lanterns.

After a few failed attempts to find lunch (complete with one instance of being ignored at a restaurant!), we tucked into a steaming basket of dumplings and bowl of spicy noodles. Continuing our exploration in the afternoon, we wandered towards the Muslim Quarter. Turning a corner, we were met with an immediate assault on the senses - scooters whizzing through crowds of people on Bienyuanmen Muslim Street, with hundreds of handmade food stalls lining the bustling sidewalks.

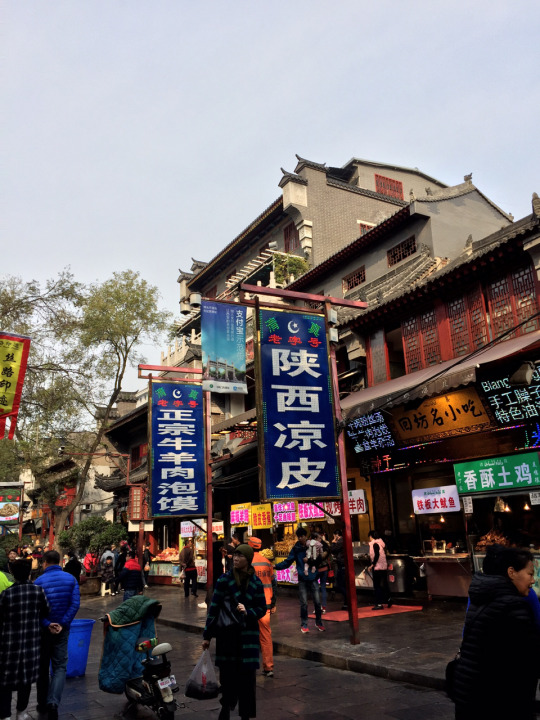

Market in Xi’an’s Muslim Quarter

The food market in the Muslim Quarter was unlike any I had ever seen before. Carcasses of various animals were hung along the street, with the meat stripped down to the bone. In China, almost every part of an animal can be used in cooking - which we saw throughout the market, with lungs, liver and heart displayed for sale. The smell of roasting walnuts, scooter exhaust and pungent jackfruit filled the cold air. Walking amongst the stalls, every imaginable food could be purchased, from deep fried potato spirals, blocks of spiced tofu, freshly squeezed pomegranate juice, and persimmon donuts. Chinese Muslim men behind stalls wore white caps, with women covering their head with beaded headscarves.

We continue along a series of side streets to find hundreds of other products on sale, from spices to pearls. We were quickly on the receiving end of some fairly intense sales pitches and bartering, in one case a vendor grabbing at our clothes as we tried to quickly walk away. Needing a break from the chaos of the Muslim Quarter, Christie and I retreated to the nearby Great Mosque of Xi’an. A complete juxtaposition to the commotion of the nearby streets, the peaceful grounds of the walled complex provided us with a welcome quiet moment. Built in the Ming Dynasty, the Mosque mixes traditional Chinese architecture with Islamic designs seen in the Middle East. Lush gardens were framed by ornate wooden archways, separating a series of beautifully manicured courtyards.

Christie wandering through the grounds of Xi’an’s Mosque

Gathering our energy over another coffee (the fatigue from riding the overnight train kicking in around now!), we headed to the South Gate of the city to walk around the Xi’an City Wall. Running alongside a moat, this impressive wall circles the historic city centre, running for 13.7 kilometres. At 12 metres tall and 18 metres wide, the wall was built to protect Xi’an from invasion, and is among the largest defensive military systems of the ancient world. As the daylight fell, Christie and I wandered along the top of the South wall as the red lanterns were lit. From our vantage point, we could see both the ancient and modern sides of the city as we walked back to our hostel for the night.

Lanterns along the city wall surrounding Xi’an’s historic centre

Day 58 - Xi’an and Terracotta Army

Christie and I woke early and headed out to visit the Terracotta Warriors, located about 40 kilometres East of Xi’an. The Terracotta Warriors (or “Army”) were only discovered in 1974 when farmers were digging a well, and is considered to be one of the most famous archeological discoveries in modern history. The Terracotta Army is estimated to have been constructed around 200 BC, and is made up of thousands of life-sized clay warriors. This Army was built to provide protection and military power for the first Emperor Qin Shi Hueng in the afterlife, and represents the soldiers he commanded during the wars that unified China. The Terracotta Warriors, which include an infantry, and cavalry, were buried near the tomb of the Emperor.

Terracotta Warriors in Pit 1 - the largest excavation site

It was freezing cold outside as we began our visit to the Terracotta Warriors. The site has three separate excavation pits, with several ongoing digs in progress. The largest pit is the size of an airport hanger, with row upon row of life-sized terracotta models. These warriors would have once been brightly painted, but after thousands of years in the ground, all colour has worn away. As I took in the impressive rows of ancient warriors, I gradually began to notice variations in their uniform, hairstyle, and posture. These small differences indicate the rank of the soldiers: from generals, to archers and charioteers. In another pit, there were also life-sized terracotta horses.

The main excavation site is the size of an airplane hanger, and growing.

After visiting the excavation site, we continued onwards to see the mausoleum of the first Emperor. This tomb has not yet been excavated, and there is little more to see than a massive pyramid of earth in the distance. Archeologists suspect that within this mausoleum there may be further life-sized models to protect the emperor, along with a replica of the ancient city of Xi’an. It is also believed that in addition to the clay figures, thousands of real people were buried alongside the emperor - from concubines to craftsman who built the mausoleum. All of these people were intended to follow the emperor into the afterlife. There are many stories and ancient texts describing the wealth and riches buried within the tomb, as well as descriptions of booby traps to guard against robbers.

Unfortunately, Christie became very sick enroute to the site, so our visit to the Terracotta Warriors ended up being quite brief. (Christie jokingly asked me to call this post “Christie learns what Immodium does and has hallucinations about going on a spirit quest”). It was a pretty rough day for her, and she ended up going to sleep immediately after our return to Xi’an.

Traditional Chinese Hot Pot

After making sure that Christie was resting and had everything she needed, I joined our British roommates for homemade Chinese hot pot. This delicious dish is made by cooking a variety of vegetables, tofu, noodles and spices in a boiling broth on the table in front of us. I had a few beers with a jovial group of Brits, including one very impressive guy who had cycled all the way from England to China!

Hotspot dinner with the Brits!

After dinner, we decided to take out Mobi-bikes (one of the countless bike-share programs in the city), to cycle across Xi’an to a bar tucked away near the South Wall. Biking through Chinese traffic, including through massive roundabouts, was equally exhilarating and terrifying - an experience in and of itself, given that so many Xi’an residents get around town this way.

The hidden underground bar, though not visible from the street, was packed with a combination of Chinese locals and a few foreigners, listening to live music, dancing and playing table games. I had a great time, and really enjoyed seeing what a night out in China was like!

Xi’an’s Bell tower at night

1 note

·

View note

Text

All Out of Luck

Last week, many felt that a line was crossed when the Instagram account of a new restaurant in New York City’s West Village, called Lucky Lee’s, purported to serve a “clean” version of American Chinese food, sans MSG and the supposed “oily,” “salty,” and “icky” feeling with which American Chinese food leaves you. Owner Arielle Haspel argued to Eater NY that the concept “celebrated” Chinese food, but positioned Lee’s version of it in contrast to the Chinese-American food developed over decades to cater to, well, American palates: “I made some tweaks so I would be able to eat it and my friends and other people would be able to eat it,” Haspel said. “There are very few American-Chinese places as mindful about the quality of ingredients as we are.” She has since apologized. But the controversy has made clear a divide over the co-option of the term “lucky” by modern restaurateurs, and brings into question its relevance in Chinese food culture.

Perhaps Haspel could have been more mindful of her restaurant’s name, too. Lee is the first name of owner Haspel’s husband, and they are both Jewish American. As Esther Tseng pointed out in an Eater NY op-ed, “It does not signal respect when Haspel uses her non-Asian husband’s first name in her alliterative branding in a manner that suggests Chinese ownership.”

“Lucky” is a common word used in Chinese restaurant names in the U.S., likely coming into prominence in the early 20th century, as restaurant owners tried to grow beyond their all-Chinese clientele and chose names that were Western equivalents, instead of transliterated versions, of their business names. It’s now ubiquitous enough that its use is an almost-immediate signal to diners that it’s a Chinese restaurant. That shorthand is so pervasive that it’s increasingly common among white owners of Chinese restaurants, some of them controversial: Andrew Zimmern’s Lucky Cricket, Gordon Ramsay’s upcoming Lucky Cat, and Jacob Hadjigeorgis’s Lucky Pickle Dumpling Company, in addition to Lucky Lee’s.

For many Asian Americans, a white business owner cherry-picking parts of Chinese culture for their own version of Chinese food can feel like it’s poking fun at longstanding traditions: In an interview that started the appropriation conversation surrounding Zimmern’s Chinese concept, the celebrity chef responded to questions about appropriation by noting the restaurant sold shirts printed with “Get Lucky” on the back. “It is interesting that all these people think it’s clever and funny to refer back to these classic tropes, and no, it’s not, it’s stupid and it’s not even that clever,” said Diane Chang, a Brooklyn-based personal chef and caterer of Po-Po’s. “When I read about [Lucky Lee’s] I was like, ‘Why is she trying to convey that feeling that you’re going to an old takeout place, but then you’re getting this other experience that is purporting to be better for you?’”

Chinese restaurateurs, especially in earlier generations, often give their businesses auspicious names based on beliefs dating back to antiquity. The word “lucky” holds deep meaning and significance in traditional Chinese belief systems. The Chinese character 福, or “fu” in Mandarin, can be translated as “luck,” “prosperity,” or “fortune”; anyone who might want to bless their restaurant with success might use the word luck, or something symbolic of it. In a 2016 Washington Post survey of Chinese restaurant names in America, “lucky” and “fortune” appear prominently in the word cloud, as does “fu,” albeit less frequently. (When transliterated from Cantonese, “fu” is actually spelled “fuk,” which is probably why it’s not in too many names stateside.) These words figure into many Chinese restaurant names, as do other traditional Chinese auspices of good luck, such as bamboo (symbolic of strength and resilience), jade (which represents 11 Confucian values of virtue), and the number eight (which sounds similar to a word meaning wealth or fortune).

“I just think good fortune and auspiciousness is essential to every aspect of Asian culture,” said Danielle Chang, founder of Lucky Rice, a lifestyle brand that hosts the Lucky Chow dining event series. She explained that luck is intertwined with everyday living in China, and has a strong connection to food. “Back in the days when China was primarily an agricultural society, praying for a good harvest — much of that has to do with good luck, like the amount of rainfall you get, and so on. So it’s tied to the harvest,” she said.

Chang doesn’t think that the full meaning of “fu” is very well understood in the United States. There is often hidden meaning and wordplay in Chinese restaurant names, she notes, even in how they’re written. Traditional Chinese characters can be written with an intricate combination of strokes that are considered beautiful to the eye, including those for “luck” and “happiness.” “That’s part of the beauty of Chinese language,” she said. “Everything is a pictograph and has all these different connotations.”

There is also a trio of deities known as the “three stars,” which are fu, lu, and shou (roughly “luck,” “status,” and “longevity”); combined, they represent cultural values about success. In fact, “fu lu shou” was the Chinese name of Cecilia Chiang’s pioneering San Francisco Chinese restaurant, the Mandarin. It isn’t so unusual for restaurants to have different English and Chinese names — “the Mandarin” was perhaps much more salient for a non-Chinese American audience because it called out the fact that the restaurant specialized in Northern Chinese cuisine at a time and place where that wasn’t the norm. (Place-specific names have always been common for American Chinese restaurants, too — Nom Wah refers to Southern China, which its cuisine is based on, says its owner, Wilson Tang.)

Restaurant owners would also find that use of words like “Lucky” drew in non-Asian customers, growing restaurants’ consumer base. As John Jung, a professor emeritus in psychology and a historian of Chinese-American history, writes in Sweet and Sour: Life in Chinese Family Restaurants, Chinese restaurant owners courted tourists “with remodeled restaurants designed with a stereotypical Oriental motif both inside and outside” as early as 1900. In addition to decor, they’d attract non-Chinese customers, who would struggle to remember transliterated Chinese names, by selecting restaurant names “that evoked images of the exotic Orient to appeal to Westerners’ romantic images of China.”

However, by the mid-20th century, changing conditions in both countries saw a shift. When Mao Zedong and his People’s Republic of China party took power in 1949, the country was declared an atheist state; as part of the Cultural Revolution he led, social values were upended, ancient religions were banned, and traditional Chinese pictographic characters were simplified to fewer strokes. Meanwhile, in the U.S., Jung writes that “as non-Chinese customers became better acquainted with Chinese names and more tolerant toward Chinese culture, it became fashionable after 1950 to return to Chinese names.”

That leaves the “lucky” name with a smack of old-timeyness, but there are still plenty of them — American-Chinese restaurants often don’t change names when a new owner takes over, for consistency’s sake. In other cases, restaurant owners might lean in on the “lucky” name to intentionally create a sense of nostalgia; many of the new restaurants from non-Chinese owners employ it alongside a cheeky, retro feel to their decor and branding. Think old-fashioned poster art or cigarette labels with women in Mandarin dresses, old Chinese newspapers, or Tiki bar aesthetics. Nostalgia is a big ticket in U.S. restaurants today: It’s the secret sauce in everything from dishes to decor to cocktails at such esteemed restaurants as the Grill and Rocco Dispirito’s new Standard Grill, both in New York.

For Chinese restaurant owners, many might look to the example of Nom Wah Tea Parlor, a restaurant in its 99th year of existence in New York City’s Chinatown; it hasn’t modernized its look. Perhaps for many non-Chinese restaurant owners, “lucky” evokes an era of Chinese restaurants that they grew up in. But Chinese restaurants stateside are evolving and expanding, and these nostalgic sensibilities can feel like an inaccurate representation of where the cuisine stands today. Coming from high-profile restauranteurs like Gordon Ramsay and Andrew Zimmern, who are already immensely popular — and powerful — it can look like the spotlight is in all the wrong places.

And when the food at a pricey restaurant from non-Chinese owners isn’t even very good — even the rice isn’t cooked properly, as Soleil Ho noted of Lucky Cricket, and as Gothamist observed of Lucky Lee’s — yet the restaurant proclaims that it’s “saving” people from “horseshit” Chinese food (as in Zimmern’s case) or from “icky” and “bloated” feelings afterward (as in Haspel’s case), well, that can zap any intended fun out of the experience. In other words, it can leave you with an “icky” feeling.

Danielle Chang says she’s noticed the word really cross over to non-Asian restaurant owners in recent years, citing Lucky Bee, a now-shuttered New York City Thai restaurant. She thinks that David Chang’s Momofuku, which from Japanese translates to “Lucky Peach” (also the name of its former magazine) and its mainstream success may have something to do with it. For her, using the word “lucky” in her company name was a way to bridge cultures. She thinks of it as fun and universal — something that everyone can grasp to some extent.

This all goes to say that the associations of “lucky” may be generational, and have everything to do with where you’re coming from. Today, there are plenty of young people who want to shake up that sense of old-fashioned branding when it comes to Chinese food. Diane Chang named her business Po-Po’s, which translates to “grandma’s” in Mandarin. “I couldn’t think of a better name because that’s why I started cooking, it’s a tribute to my grandma and her recipes,” she said. She was well aware of the confusion and unfortunate connotations that the name might cause for an American audience — the results when you Google “eating po-po’s” are unsavory — but she felt it best represented her.

“To this day I still have to explain whenever I call in orders, but for me, it was like, why should I bend with a quirky, cute name, because that’s just not me,” she said. She’s come to embrace the confusion, owning it with a smile when people mistakenly call her “po-po” thinking it’s her name. And on the flip side, she describes the warm feeling of familiarity as a “secret handshake” when people understand the meaning.

Rich Ho, chef-owner of the Taiwanese noodle soup restaurant Ho Foods, can relate to the confusion with vendors, because his restaurant sounds similar to “Whole Foods” — then, there’s the other, slang usage of “ho.” But he thinks his restaurant’s name is evocative of its clean, pared-down aesthetic, and it’s a sort of “dad joke” that it sounds like Whole Foods.

Growing up, Ho says he was made fun of a lot for his last name, even, he thinks, by his fourth grade teacher. But he’s come to embrace the name with pride. “At the end of the day it’s my name, and it’s just an Asian name and I’m proud of it, so I’m not gonna change it.”

Whereas earlier Chinese restaurants tended to stick with contrived Chinese restaurant names for mass branding’s sake, these relatively young, American-born business owners are picking names that are personal to them, despite the confusion or so-called negative connotations they may provoke for a Western audience. As Jung wrote, “Changes in the characteristics of Chinese restaurant names occurred over time provide a barometer of the acceptance of the restaurants in the larger society.”

In the end, it’s not so much the nomenclature as the superior marketing positioning that’s problematic for these white-owned Chinese restaurants today. One need not understand all the nuances to enjoy something. But there are layers of complexity in the “lucky” terminology, and meanings and generational attitudes evolve. And as a young group of Chinese Americans fights an uphill battle to be seen amid the stereotypes associated with their culture, they may be more inclined to leave “lucky” behind.

• How Lucky Lee’s Could Have Gotten an ‘American Chinese’ Restaurant Right [ENY]

• Gordon Ramsay Hit Back at Criticism of His ‘Vibrant Asian Eating House’ [ELON]

Cathy Erway is the author of The Food of Taiwan: Recipes From the Beautiful Island, The Art of Eating In: How I Learned to Stop Spending and Love the Stove, and the host of the Heritage Radio Network podcast Eat Your Words and the upcoming podcast Self Evident.

Emily Chu is an illustrator and visual artist from Edmonton, AB, Canada.

Editor: Erin DeJesus

Eater.com

The freshest news from the food world every day

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Policy and European users agree to the data transfer policy.

Source: https://www.eater.com/2019/4/16/18311375/lucky-lees-cricket-cat-chinese-restaurant-controversy

0 notes