#he might not be the most articulate poet but his love language is acts of service and physical affection at least

Text

What Jungkook is like in a relationship/ Jungkook as a boyfriend Tarot reading

I was gonna put Jin up first but I finished Jungkook quicker so oops but I’m finally back after 200 years of adulting things

1. How long does it take Jungkook to get into a relationship? 8 of pentacles, 2 of cups, the world Do he prefer long or short term relationships 7 of swords, ace of wands Nelys the alchemist 27 reversed, 5 of swords, 9 of cups reversed

For an actual relationship and not just dating I think he can take a while if not a long ass time because he’s too much of a perfectionist and will work hard at making sure everything is right before getting into a relationship. I don't know why I’m getting like before things would get “steamy” he would never let them see his body until he worked out enough for his own standards like everything has to be perfected and mastered beforehand. There’s also a reoccurring theme of work getting in the way and even in the beginning stages it’s like he meets up with them does whatever then has to hurry and run back to work and is like “hey I gotta go but I’ll text you later” type of shit. Big focus mostly on career though so it’s hard to tell. But I still think he’s not just sleeping around with just anyone I mean they have to be important if the 2 of cups pops up. I don’t think he’ll get into an actual relationship with someone unless there’s a strong connection. Or at least to him it seems like an important connection.

I gotta say too that the 7 of swords usually screams fuckboi to me but in this case I think the lying and trickery aspect of the card can be taken literally to mean of course he has to lie and sneak around when fans would legit doxx and slit his partners throat if they knew they were together. But anyway in a relationship there’s definitely gonna be extremely strong sexual chemistry I don’t know why this keeps popping up but alright. But one annoying thing is that in a relationship jungkook seems to like fighting in a way. He doesn’t like to lose to anything and will want to win an argument even if it’s petty. There’s also a kind of energy of the other person feeling inadequate sometimes with how much praise he gets from the entire world. It makes the other person feel as exposed since they’re not doing as “well” in the grand scheme of things. And will sometimes not want to compliment him on things because he gets compliments from the entire world this is just day to day petty shit. Another thing is getting into a relationship thinking this person is the one but then realizing over time and all the work you put in was useless cause this is emotionally unfulfilling.

2. Past and present love life king of pentacles, wheel of fortune reversed, queen of pentacles

Past: bruh his love life in the past is similar to the present. He was mostly focused on building his own career and wealth and love was on the back burner tbh. I think since he has huge goals for himself there was really no time to even do other things. But his love life right now seems like it’s a external long term problem affecting it. And I think he’s learning how to balance his love life and work life right now and just letting things happen and trying to take care of his body and mind.

3. What is he like in a relationship Tobaira of the waters 37 reversed, The glanconer 62 reversed, mother of dawn, knight of pentacles, flashover 11, 6 of swords reversed, addiction 11, envious gluttony 9, is this me? 4

When Jungkook is in a relationship he doesn’t fully feel like he can be emotionally vulnerable and instead will act mischievous and play around to hide behind vulnerability. It can tend to make the other person mad because they never know when he’ll actually be serious because he plays too much sometimes. There’s also playing up to peoples ideas of him. It’s not outwardly tricking people but allowing them to believe what they want and project their fantasies on him. It’s like a weird energy of wanting to rebel but also you feel stuck and want to please them so you don’t let them down. I think he overthinks legit everything and makes things a bigger deal in his mind than what it really is.

Another thing is he could have a tendency to stay with someone even if it’s toxic because of a mix of remembering the good times and also insecurities. There are big vibes of being emotionally stunted like I feel that he’s mentally a teenager still and even though he’s physically different and projects something different. When he’s in a relationship; he still feels like that insecure kid in his head and he can’t escape it. It’s like a false bravado thing going on. There’s a hole that leads to darkness and from that another one that leads to even more darkness. That's dramatic but that’s what it’s like for him. It’s like this emotionally starved monster in his head but in reality the monster is this scrawny young boy who wants to let go and open up but is blocked by himself and running away from his shadow aspects. I do see him though slowly moving towards becoming more open, honest allowing his vulnerable and passionate side out in a healthier way but it might take a while (unless he’s already been working on this) since the knight of pentacles is the slowest knight but he’s also the most stable and loyal.

4. What is his "type" the sage 19 reversed, knight of cups reversed, Jeanne the maid, golden empress, the lovers reversed, 3 of cups reversed

His ideal type is someone who can come across as aloof, cold, excessively critical. Hey I tried to give him the benefit of the doubt but when I pulled a clarifier I got the knight of cups reversed lolll. Dude likes toxic people apparently. On the surface they might look “normal” but on the inside their inner world is overflowing and they have an abundance of charisma and sexual energy. Honestly that could be a big reason why he likes that. There’s a big dualistic energy in them and appearing the best on surface level but underneath is really unpredictable and has the energy of unrequited love. I think he likes those types of people who don’t fawn over him like he’s the second coming of Jesus tbh. This person doesn’t give 2 fucks and they don’t tell everything up front they’re mysterious and it’s more of a challenge for him. They’re really good at appearing humble and maybe innocent even but that’s just because they know how to woo people really. They’re confident and can convince people of almost anything especially around those in power they know how to present their best self to get what they want.

At first I was confused why your ideal type would be someone that seems manipulative af but it makes sense when Jungkook has a lot of deep dark shit he needs to work on from the other cards. I think it’s a big codependency thing and excitement that someone toxic can bring also the fact that this person is down for anything in the bedroom they’re not ashamed or shy about it. His idea of love is pretty distorted he thinks he needs someone who is as intense as he is but really it would be a bad combination especially with the lovers reversed. I’m getting especially that as long as he keeps going after these types of people, he’s never going to be with his “true love” for a lack of a better term. Basically not be with someone who is actually good for him. There could be third party bs but I’m getting more of an overindulged and addiction energy between both of them. Even if he knows they’re no good it’s just so intoxicating it’s like a damn drug to him and it feeds into his more animalistic side (I have no idea how to articulate this lmao) it’s like possessive nature. This reminds me a lot of the attachment types since there’s a lot of people like this who love a more avoidant person and I feel that Jungkook is probably avoidant himself so this is like home sweet home to him. It puts him in the cat chasing mouse position instead of the other way around. That emotionally unavailable energy is very appealing to a lot of people I guess especially when you’re used to everyone bending over backwards for you.

5. What is his love language: Ta’Om the poet 29 reversed, the bodacious Bodach 59 reversed

He likes when someone actually does helpful things for him that is useful and not like the annoying meddling energy of just doing stuff for him that he doesn’t want you to do. He also does this for others. So acts of service mostly but you already knew that.

#kpop tarot#bts tarot#bts jungkook#bts#kpop readings#kpop#jungkook#jeon jungkook#jeon jeongguk#free tarot#kpop predictions#kpop astrology#bts astrology#bts readings#kpop tarot reading#tarot#bangtan#bts tarot reading#tarot cards#tarot reading#bts boyfriend#free tarot readings#oracle cards

312 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview with Konstantinos Pappis

Konstantinos Pappis is a poet and King’s alumnus who studied Strategic Entrepreneurship and Innovation for his Master’s. He shares his blackout poems on Tumblr @blackout-diary and on Instagram @blackout_diary, and is the Music Editor at Our Culture. The King’s Poet’s Karen Ng talks to Konstantinos about his poetic experiences, process, and inspirations.

What is your earliest memory of poetry?

Like many people, my earliest memories of poetry are associated with school, where I felt pretty alienated by the way we approached poetry. It felt cold and analytical and I struggled to connect with it on a personal level – or perhaps there was less of a need to at that age. Although there were some Greek poets we studied in school whose work I remember liking, including C.P. Cavafy, Kostas Karyotakis, and Odysseas Elitis, it wasn't until later during my adolescence when I started discovering poetry outside of an academic context that I was able to appreciate it more. Things really started to change when I was introduced to English and American poets; for some reason, something about it not being in my native language made it easier to engage with and relate to. And then eventually I was able to approach different kinds of poetry from both an intellectual and an emotional standpoint.

How did you first realise you wanted to write poetry? What do you enjoy the most about writing?

In a word, Tumblr (RIP). But honestly, finding a community of people who used poetry as a form of expression more than anything else inspired me to do the same. I realised it wasn’t this inaccessible, overly sophisticated thing that you had to be especially clever or well-read to really get. Again, if you weren’t doing it to get a good grade, it was considered a bit weird to engage with poetry in any way, so seeing it outside of that context was pretty eye-opening.

It was also something that came with realising I had a passion for the arts in general. Music had always been my primary outlet, but poetry took over when I felt I needed the words to have more space on their own – to jump out on the page and release all the teenage angst I was going through, because listening to Creep every day somehow wasn’t enough. None of that poetry was any good, of course, but it was vital. And when I felt like this really personal thing was something I could share and exchange with friends, writing also became an important part of embracing vulnerability and forming close connections, too. I came to enjoy it more as a medium than an art form, in a way – at first, at least.

In terms of what I enjoy about it now… Well, it’s hard to articulate, but if we’re talking about writing poetry specifically, I guess the appeal hasn’t changed all that much. It’s been a while since I’ve felt inspired to write a poem, but in the past it’s always been when I felt like I need to channel something that I couldn’t through any other form. Some might view the poetic form as being kind of limiting, but I feel like it’s quite the opposite – it’s almost freeing in the endless possibilities that it presents.

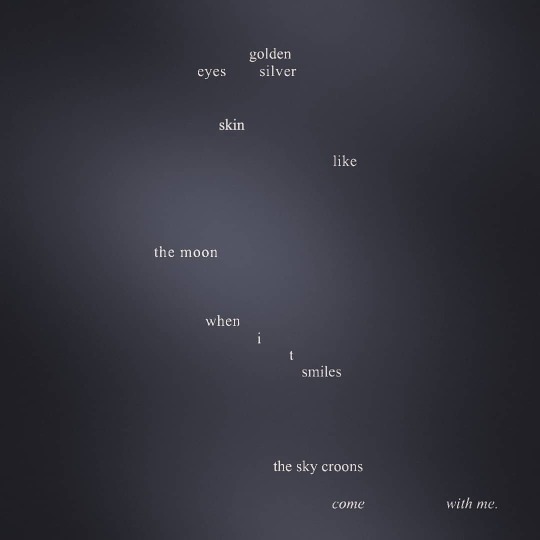

Above: a blackout poem by Konstantinos. The source text is “Moon” by @makingthingswrite on Instagram.

You’ve written a lot of amazing blackout poems! What about this form appeals the most to you?

Blackout poetry appeals to me for almost entirely different reasons. I treat it more like a mental exercise that can be both calming and stimulating; something that operates on a more subconscious level. I like that I don’t have to be particularly inspired to do it, not even by the text that I’m using. I like that it doesn’t necessarily have to make sense, that I don’t have to stress over the final result too much. I like that it can then inspire me to make something else. I like the visual aspect of it, the act of repurposing something and giving it new meaning not just by altering the text but also its surroundings. Of course, people can make blackout poetry in a much more intentional way, but what sets it apart for me is that it’s a creative outlet that can be simple and almost passive yet gratifying at the same time.

How do you select a text for your blackout poems – where do you look? What do you look for?

It really varies: sometimes I’ll take photos from a book – I used to do blackout on old books nobody would ever open, but I switched to doing everything digitally – and sometimes I’ll search for poems or articles randomly online. Reviews often work quite well. There does have to be something about the text that sticks out to me for me to use it as a source, but I tend not to overthink it.

I love that – inspiration is everywhere in our daily lives, even when we aren’t looking for it! Can you tell us a little about your writing process? Is it more emotion-led or methodical?

For blackout it’s entirely intuitive. For poetry in general I would say it’s almost always emotion-led, but the editing part can be more methodical. Normally, a lot of it happens late at night when I can’t sleep, and if I can’t sleep long enough for me to write things down and it doesn’t strike me as absolutely terrible in the morning, then it might turn into a poem.

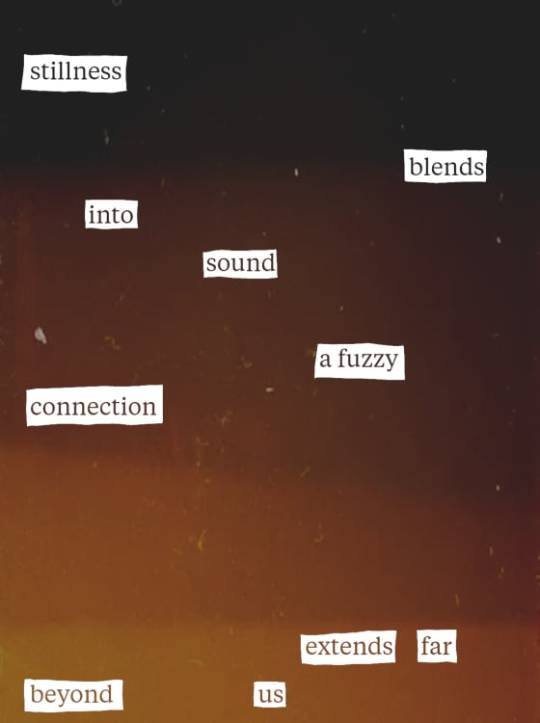

Above: a blackout poem by Konstantinos. The source text is Sam Sodomsky’s review of duendita’s song “Open Eyes”.

Your poem pebble (an ode) was one of the first poems to be published in our magazine. It isn’t a blackout poem, but could you tell us a little about it too – do you remember what it was like writing it?

See above re: late-night thoughts and the utter absurdity of the human condition!

How has your experience of sharing your poetry to Instagram been? Are there any tips you could share with our readers?

I haven’t done it in a year, partly due to a lack of inspiration and partly because I’ve tried to distance myself from Instagram and other social media platforms as much as I can – though maybe I’ll go back to Tumblr? But my experiences with the Instagram writing community have been nothing but great – I participated in Escapril back in April of last year, a yearly event founded by Savannah Brown, that encourages users to write and share a poem a day based on a prompt. It was a really great and fun challenge that helped me write and read more and connect with other poets. I would say participating in these kinds of communities is probably the best way to utilise the platform.

Thank you for that advice! On a similar note, which poets and poems inspire you the most? These could include childhood inspirations… Have your influences changed over the years?

I would not be the person I am nor would I have any interest in poetry if it weren’t for Sylvia Plath. I can’t even pinpoint exactly when I first encountered her work, but I identified with it to an almost unhealthy degree as a teenager, as I’m sure many people have. I still get that feeling whenever I revisit her poetry or read more about her life and art. Also, a lot of spoken word videos from people like Sarah Kay really resonated with me at a young age.

More recently, the closest I’ve gotten to that feeling of being deeply excited and inspired by poetry was when I discovered Savannah Brown’s work a couple of years ago. Her spoken word videos and poetry films really moved me, and her second poetry collection – which came out last year – is absolutely incredible (I wrote about it here). Lately I’ve also been listening to a lot of musicians whose work intersects with poetry, including Cassandra Jenkins and Anika Pyle, whose most recent albums reckon with grief and loss in a really powerful way.

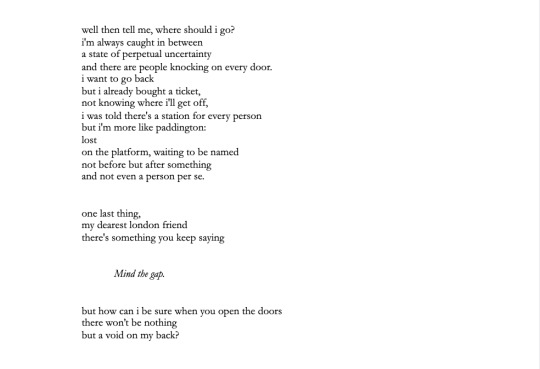

Above: a blackout poem by Konstantinos. The source text is Christopher Gilbert’s poem “Fire Gotten Brighter”.

Are there any styles besides blackout which you particularly love, or themes? Are there any topics you gravitate towards?

I’ve always gravitated towards confessional poetry, both in terms of what I tend to write and what I like to read. Something most of the writers I’ve mentioned have in common is that they use intimate language to evoke a deep yearning for connection, in the face of existential dread and the unfathomable vastness of the cosmos. That usually does the trick!

Have any experiences at King’s Poetry Society or King’s in general – events, classes, readings, people you’ve met, or London itself – been particularly memorable, or inspired you? Can you tell us a little about them?

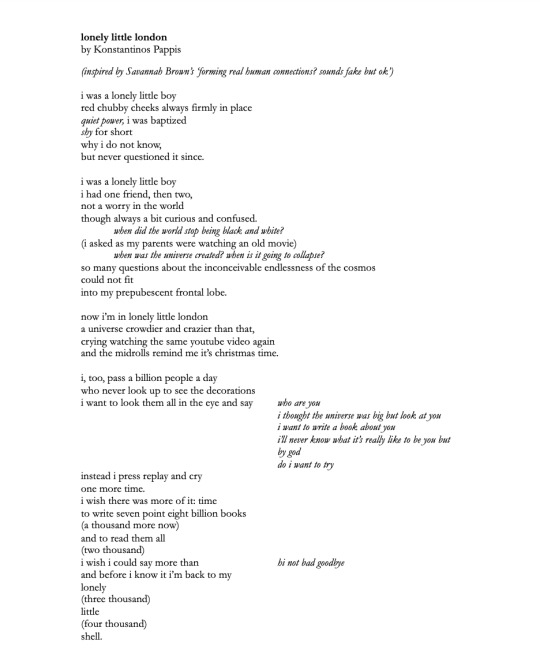

Absolutely. Just being in London, not even necessarily the experiences I had there, made me want to write more poetry than I had in a long time. There’s a Savannah Brown video essay on YouTube where she talks about passing a billion people on the street – obviously in the before times – and being like, “Who are all of you people? Could I care for you? How many of you idiots could I love?” That’s basically the gist of what had been stirring in me for a long time and that I still think about to this day. And then being a part of King’s Poetry Society was an opportunity for me to try and channel that, and engage in an actual physical writing community in a way I never had before. I literally read a poem inspired by that video during one of our poetry reading events – that will certainly stay with me.

Above: Konstantinos’ poem “doors on the underground”. He read this poem at one of the 2019-20 King’s Poetry Society critique sessions.

How important do you think writing communities are, in fostering “better” writing? In your experience, is writing helped by discussion?

I think they’re incredibly important, not just in fostering “better” writing but also fostering a space for vulnerability. Poetry can be an intensely private form of writing, but so much can be gained from discussing it, especially if one is looking to not only hone their craft but also learn from and connect with others. Us writers can be especially introverted people (hi!), and may be discouraged by the long stretches of silence that can pervade a poetry meeting, but there’s power in hearing the words you or someone else has written out loud. Even a single comment can completely change a way you think about a poem.

What do you think the value of reading poetry is? Can a poem profoundly change someone’s life? Conversely, can someone read a poem and be unaffected – and if this happens, has a poet “failed”?

I think Marianne Moore sums it up pretty well in her poem Poetry, where she talks about finding in it “a place for the genuine.” As for the second question, poetry can definitely change someone’s life – not to be corny or anything, but like all art, it can also save someone’s life.

That said, I don’t think a poet has failed if the reader feels emotionally unaffected by their work. Sometimes, a writer may wish to portray an event or theme in a cold and unaffecting manner to get a certain point across. There’s value in that type of poetry, too, and art’s inherent subjectivity means that someone might be moved by a poem that someone else feels indifferent towards. There’s also value in poetry that is private and not meant to be shared, because even if only one person derives something from it, then it is valuable. I do think, however, that the further one strays from that ideal of earnestness, the closer the work hinges on being trivial or pretentious. We’ve moved past the need to be overly cynical or ironic.

I agree, poetry that is never shared is not lesser by any means – I find great personal value in treating a poem like a diary of sorts. Maybe each stanza mimics a different entry... With all that you feel manifesting into this thing that is at once completely attached to your experience but also – if shared – something that becomes detached and open to reinterpretation... That is really powerful. How do you think people who have never written before could be encouraged to start writing for themselves, whether for fun or as catharsis – without the pressures of becoming someone recognised or followed?

I really like that approach! I think the diaristic style of writing is often looked down upon as less legitimate, even though it isn’t. To answer your question, I think normalising the act of writing poetry purely for enjoyment or as a form of catharsis is really important, especially from a young age. Part of that could be achieved by exposing young people to more than what one might call the poetic canon. Being disappointed that a student isn’t engaging with poetry when they’ve only been introduced to Shakespeare is like assuming someone isn’t musically inclined when they’ve only been exposed to a single genre of music. Another way would be to incorporate more writing activities that utilise the poetic form, and allow the freedom to explore it outside the confines of academic study. I’m not saying all teachers should follow the example of Dead Poets Society, but there are so many ways to foster creativity and make poetry more approachable.

Do you think poetry is sometimes perceived as an inaccessible art?

100%. I think that’s the biggest problem with how poetry is perceived. A lot of it comes down to the way poetry has been taught and disseminated for centuries – through a lens that is inherently exclusionary, upheld by systems that are classist, racist, sexist, etc. Hopefully that is starting to change – studies have shown that more and more young people read and write poetry, largely thanks to the rise of social media poetry. Poetry can represent such a wide range of experiences, but for people to view it as an accessible art form, more barriers need to be broken. Amanda Gorman becoming the youngest inaugural poet in American history, and the first Black poet ever to perform at the Super Bowl this year alone is certainly a huge sign of progress.

Do you have a favourite literary journal, or a poetry platform you would like to recommend? What have you been reading lately?

Subscribing to the Poetry Foundation and the Academy of American Poets’ poem-a-day newsletters has been a great way of keeping poetry in my everyday life. Recently, I’ve also been loving a podcast called Poetry Unbound, where each 10-15 minute episode immerses you into a single poem. On YouTube, I love Ours Poetica, a video series curated by poet Paige Lewis in collaboration with the Poetry Foundation that features readings of poems by writers, artists, and actors – including John Green reading Moore’s Poetry and Savannah Brown reading her poem the universe may stop expanding in five billion years. It offers a truly intimate and approachable way of experiencing poetry.

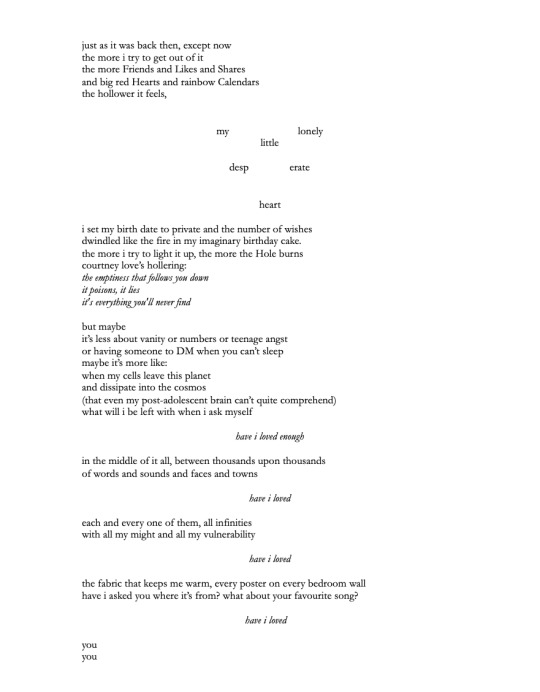

Above: Konstantinos’ poem “lonely little london”.

Is it important to you to read a wide variety of poetry, from different communities and on different subjects? Do you think it’s important for poets to write about things beyond their immediate world?

That’s probably the biggest shift that has happened since I first got into poetry – realising how important it is to read widely. I was mostly drawn to poetry that reflected my own limited experience, but now more than ever I find it vital to immerse myself in different points of view, especially from underrepresented or marginalised groups. I now see poetry less as a means of personal expression than a form of empathy, and because of that I’m able to gain so much more from it. That said, I don’t think it’s necessary for poets to write about things that aren’t part of their immediate world. It depends on one’s goals and ambitions, but there’s already so much that’s unique about a person’s immediate world – things that are reflected in society at large – that being forced to write outside of it can often lead to work that feels hollow and insincere, or even insensitive. That doesn’t mean it has to be limiting – the beauty of poetry is that you can write about your immediate world but not necessarily through it.

Lastly… Do you think a poet is born a poet, or made into one? Which is more important: natural talent, or practice and growth? Can anyone become a poet? If everyone has it in them, do you think anyone who puts their mind to it can produce meaningful work – since, of course, all work is meaningful in one way or another, whether privately or publicly?

This is a slightly tricky question to answer, because either way it could imply that only some are afforded the privilege of becoming poets. If a small percentage of people are born poets, then of course that means everyone else is inherently excluded; if one is made into a poet, then only those who are able to cultivate any artistic inclinations will have the opportunity of fulfilling their potential. Most people will say the truth, as always, is somewhere in the middle, that it’s some complicated combination of the two. But I feel it’s much simpler than that – when you boil it down, really, everyone is born a poet.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Pyaasa (1957, India)

When a print of Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa arrived at the Mumbai offices of Ultra Media & Entertainment (a film distribution and production company), the incomplete negative had almost completely melted. One of the most popular and acclaimed landmarks of Hindi cinema (“Bollywood” to many of you) needed immediate restoration. Several months of clean-up ensued, and the restorationists submitted the newly-cleaned print to the 2015 Venice International Film Festival. Pyaasa now has a second life for cinephiles who want to explore more of Bollywood – although, for the very fact that Pyaasa feels like a socially and thematically subversive work for its time, it is not recommended for beginners. As Guru Dutt’s first film after starring in and directing Mr. & Mrs. ‘55 (1955), Pyaasa is a magnificent feat of artistry and certainly Dutt’s most cinematic movie that he had made by that juncture in his career.

Vijay (Dutt) is a struggling poet uninterested in composing the treacly love poems that publishers and the public are demanding. “You call this gibberish ‘poetry?’” asks one prospective publisher, “You must write poems about love.” Against the wishes of his mother (Leela Mishra), he avoids living at home, lest he subject to the demeaning insults from his brothers. One evening, Vijay is wandering the streets when he hears a prostitute named Gulabo (Waheeda Rehman) singing his poetry. He follows, but she pushes him away when she realizes he has no money. Gulabo will, after reading a paper dropped from Vijay’s pocket, deduce that the person she just banished is the poet whose works she is enamored with. Further bitterness and disappointment follow Vijay when he learns his ex-girlfriend Meena (Mala Sinha) has married a hotshot publisher, Mr. Ghosh (Rehman; no relation to Waheeda Rehman). Vijay will begin work for Ghosh as a servant, leading to a finale flushed with bitter lyricism. The film also stars Johnny Walker as Abdul Sattar, a massage oil salesman who serves as comic relief.

Having gone through two previous Guru Dutt films in chronological order, my initial experiences with the Bollywood superstar included the swashbuckling spectacle of Baaz (1953) and the social satire of Mr. & Mrs. ‘55 (1955). Those two films allowed me to see the trajectory of Dutt’s directorial and developing aesthetic senses. Thematically, there is little in those previous films that could have prepared me – or frequent moviegoers in India in 1957, really – for what Pyaasa brings. The film is primarily capturing the travails of a struggling poet who composes poetry unmarketable to the masses. His words tell not of sweeping romances or witticisms, but commentaries on how cruel and destitute the world can be – heartbreak, injustice. Some of his poetry is social protest; these words seeping into the film’s soundtrack as lyrics (more on this later). For Vijay, his poetry serves to cleanse his soul of cynicism; anyone who purports to enjoy his poetry is celebrated, but he is not focused on numbers and mass popularity (although a decent paycheck might help). Yet there are still moments of the romantic in Vijay, at least from the past. In a flashback from his college days just over twenty minutes in – this scene is poorly edited, and it was not until several minutes afterwards did I realize it was a flashback – he recites this:

When I walk, even my shadow lags behind.

When you walk, the universe keeps pace.

When I stop, clouds of misery gather.

When you stop, spring’s radiance is outshone.

That is the extent we ever hear of Vijay’s romantic poetry. 1950s Bollywood films certainly approached topics of materialism, but none to the extent and serrated cutting edge of Pyaasa. Pyaasa never reaches Satyajit Ray-levels of despondent, soul-crushing resolutions; however, this movie is more willing than most working in Hindi-language cinema at the time to avoid a glossy or compromised ending. Credit to Dutt for overruling screenwriter Abrar Alvi – who lobbied for a compromised ending – for the film’s fearless final twenty minutes. Perhaps Vijay’s decisions in the closing stages are not the most enlightened or practical, but make sense given the character’s tenacity and Dutt’s desire for an unconventional finish.

Most remarkable about Alvi’s screenplay to Pyaasa is how Gulabo is treated. No matter where movies were produced in the 1950s – the United States, Europe, across Asia, and elsewhere – the depiction of prostitutes and sex workers was a lot to be desired. As great as the following two movies both released in 1957 are, Pyaasa treats Gulabo with more dignity than Nights of Cabiria (a film that, upon seeing it six years ago, helped me recognize some personally regressive attitudes towards sex workers and learn more about the topic) does with its titular character. The tendency, even now, is to morally punish a sex worker character in a film, to demean them for their sexual expression, or to portray them as tragic figures suffering through unimaginable conditions of abuse or poverty. None of these apply to Gulabo – always in control of her situation, comprehending almost fully what she wants most in life, and subordinate to no one. Her actions throughout Pyaasa are out of love for Vijay and Vijay’s work, but there is no sense of “belonging” to a man or a romantic ideal of fixing a broken soul. A broken Vijay does not deserve the familial, financial, and mental turmoil that he is struggling through, so Gulabo selflessly helps Vijay from the desperate depths of his own mind.

In a twist, Dutt and Alvi – in a certain way of looking at it without spoiling the film – take the main character out of the film about a half-hour before the conclusion. We see Vijay’s brothers attempting to soothe their pain over their mother’s recent death (unbeknownst to Vijay) with illicit payments from Ghosh. Ghosh – a publishing executive seeking to expunge any inconveniences of his pocketbook or his twisted conscience, has a dastardly plot to help only himself. Vijay, though separated from the narrative for several resolving scenes of Pyaasa, is disgusted with what he has seen and heard from his family, his employer, and probably countless others in the past. In the film’s final musical number, Vijay recites/sings:

This world of palaces, of kingdoms, this world of power,

The enemies of humanity, this world of rituals,

These men who crave wealth as their way of life,

For what will it profit a man if he gains the world?

The returns diminish; a desire to acquire more feeds upon itself, destroying the moral groundings of all. Though Guru Dutt and Abrar Alvi probably did not have Buddhism on their minds, Vijay’s answer – articulated with the light illuminating his figure while facing the camera – to all he has seen is a weary enlightenment. In these final scenes, Vijay appears as if he has ascended to a higher plane of existence, knowledge, and perhaps spirituality.

Cinematographer V.K. Murthy (a Dutt regular, having shot Mr. & Mrs. ‘55 and 1959′s Kaagaz Ke Phool) improves upon his previous collaborations with Dutt here. Murthy is the most important person that makes Pyaasa – by some distance – the most aesthetically enthralling movie that Dutt had directed by this point. Whether dealing with flashbacks, fantasies, or reality (or even surrealistic touches to reality, which is something that is unexpected, but contributes to the feeling Vijay is not entirely present in the corporeal world), Murthy provides gorgeous deeply-staged shots with dollied close-ups that, in less-assured hands, might come off as corny but instead heighten the dramatic stakes. But Murthy is not helped by editor Y.G. Chawhan, who handles scene transitions poorly and bungles the first hour’s flashback by not properly announcing that it is a flashback.

As an actor, this is Dutt’s most trying performance. After playing romantic leads Mr. & Mrs. ‘55 and Baaz, this performance in Pyaasa is worlds apart from his past. By the midpoint, Vijay sees nothing but the corruption of the world and is doing little to improve his situation. Vijay is Dutt’s least dynamic protagonist I have encountered thus far, but that does not devalue his character’s suffering and that inimitable way Dutt broods and listens or observes to other characters. Dutt’s character suffers silently; his performance is never labored, but enriched by his naturalistic acting. Waheeda Rehman, appearing in one of her first films as a leading actress (the role of Gulabo was originally intended for Madhubala), is stunning – her charm prevents Pyaasa’s existential and anti-materialistic themes from landing with a thud that might have excited some European auteurs at the time. Her appearance is undermined by the lengthy flashback that takes her out of the film’s first hour after one hell of an introduction.

Pyaasa includes a spellbinding musical score from composer S.D. Burman and lyricist Sahir Ludhiyanvi. But considering that the songs are built around Vijay’s poetry and the plot concerns his struggles, Burman’s music is secondary to Ludihyanvi’s lyrics – Ludihyanvi himself was primarily a poet who wrote in Hindi and Urdu. There are fewer musically spellbinding back-and-forths like “Udhar Tum Haseen Ho” in Mr. & Mrs. ‘55. For Pyaasa, poetry recital serves as musical performance for the film’s most interesting songs. Waheeda Rehman’s one hell of an introduction in “Jane Kya Tune Kahi” – where Gulabo (Waheeda Rehman was dubbed by Geeta Dutt) recites Vijay’s poetry back to him without knowing the fellow in front of her was the author – sets everything forward. This alluring misunderstanding of a song introduces the romantic tensions early, eliminating any annoying teases that might distract from the film’s larger themes. The climactic “Yeh Duniya Agar Mil Bhi Jaye To” defines the film, with its stunning, poetic lyrics, and is as context-dependent as original songs can be in cinema. Layers of meaning also sung earlier in “Jane Woh Kaise Log The” (behind the aforementioned song, it serves as the second-best poetry recital as performance) are expanded upon.

Less acclaimed from Bollywood fans but appealing to yours truly (I am grounded in Western musicals) is a fantasy sequence within a flashback: “Hum Aapki Aankhon Mein”. Sung by Vijay (Mohammad Rafi dubbing Guru Dutt) and Meena (Geeta Dutt dubbing from Mala Sinha), it is a song of budding love in a setting only possible in dreams. Or a soundstage, I guess. With maybe too many smoke machines concealing their feet, Vijay and Meena dance together with a gracefulness not out of place in any place that values the transporting nature of musicals. Johnny Walker (dubbed by Rafi), who is weirdly adorable in his comic relief roles, is endearing in “Sar Jo Tera Chakraye” while trying to sell his oil massages to passers-by. With the exception of these two, almost the entire Burman-Ludhiyanvi score draws its operatic-like drama from the plot – so make sure to concentrate a bit more on the lyrics than usual for Hindi-language movies.

For some cinephiles who have not yet ventured into Bollywood but have seen Bengali films (probably Satyajit Ray’s movies), Pyaasa might be an ideal point of entry for its combination of Bollywood escapism and Bengali-inspired parallel cinema. For everyone else, Pyaasa will be an anomalous, but memorable entry into the Hindi cinema canon.

Pyaasa translates to “thirsty” in English. That might not be the most appealing title, but it reflects Vijay’s craving for a righteous, altruistic world that just does not exist. How much of Vijay was a reflection of Guru Dutt is a point of speculation – Dutt, an advocate of social justice, seems to have enjoyed more creative freedom in Pyaasa that was not apparent in his previous films. His political voice is more pronounced here than ever before, showcasing an artist displaying a mature understanding of the medium he wields. At thirty-two years of age the year of the film’s release, Guru Dutt shows a confidence that belies his youth. It results perhaps not in a call to action, but to show us a response by a man so completely dedicated to his craft.

My rating: 9.5/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. Half-points are always rounded down. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found here.

#Pyaasa#Guru Dutt#Waheeda Rehman#Mala Sinha#Bollywood#Rehman#Johnny Walker#Leela Mishra#Kumkum#Shyam Kapoor#Abrar Alvi#V.K. Murthy#Y.G. Chawhan#S.D. Burman#Sahir Ludhianvi#My Movie Odyssey

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Death of the Poetical? and why overreaching statements like that are sometimes of use

OK so I’m deliberately going too far with this one in the first half, but in the second I’m going to aim to defend the critical practice of articulating overly large and ‘cool’ ideas which, although they sound good, aren’t very useful in practice.

So poetry isn’t dead, obviously, but there is a lingering sense of obviousness that hangs over a lot of modern poetry. There are loads of good modern poets- but also a lot of crap which seems bad because it’s obvious and predictable. There’s a lot of fuckery to do with line spacing and word spacing, and a lot of annoying use of swearing and proper nouns. There aren’t many very long poems going on at the moment, and there isn’t much exciting use of language anymore. No one has written a national epic in ages.

Of course, no one would blame any modern poets for any of these failings anyway. There are no rules anymore, so how are you ever going to do something interesting? You can’t mess with form if form isn’t even in the game anymore, you can’t mess with words when no one cares if you mess with words anymore, and, particularly if you don’t sit in a more interesting category relative to culture (non-western and non-white), then there’s not much to even write about anymore. Everyone is all about how poetry can be anything now, which is cool, but I don’t think we’ve fully reacted to that yet in general, as a lot of older poetry was interesting to us when it seemed to be most outside of restrictions or typicalities. So Donne’s misogyny would never fly now, but it was commonplace back in the day, so when he had an instance when he seemed to regret his misogyny or respect women more that was very interesting and brilliant. Same thing for when people started to mess with form and informal word choices.

This is hugely oversimplified, but it is of course true that the fewer restrictions there are (and I now believe there are none at all on poetry) the fewer new and exciting things there are that can be readily done. So what about subjects? I guess by the poetical I mean the sort of anti-space that you often have to write out of. Usually you want to hear something a little new, or which does something slightly different or better to something else. This is always difficult amongst the vast amount of poetry that has been written. Poetry goes over the same grounds- e.g. love, death, mountains- a whole lot, and there’s a huge amount of anxiety over finding new space whenever you put out work. This has always been managed, and always will be managed, probably, as there are always new effects to generate and new things to write about, so there’s always something new to share.

But if we go back to the beginning with that idea and say that poetry is the sharing of a personal observation on the world, then one of the other fundamental things we want in that is for it to be new, of course. You wouldn’t want to say something too simple, or too obvious, or write a poem that has been done before. The question of inspiration also depends on writing about something that isn’t fully formed or fully apprehended by the poet yet. The act of writing the poem is very often a way to pin down a big concern, or to attempt to. That is, you have to not have all the facts. You don’t know why the mountain makes you feel like that and you can’t put it into words, you don’t quite know if that girl loves you or why or why not, or you have this very strong feeling about how your Christianity and your body are interlinked and you’re trying to share this very unique and beautiful thing. You can call the empty category which you have to write half out of, or write your way out of, even, the poetical.

Here’s the weird idea: if you need to not have all the facts to be in the poetical, is the poetical not dead in a modern age where we have a huge amount of facts coming at us all the time? Is it really possible to be so late in tradition that everything has basically been done?

I mean, imagine I want to write a poem. Nothing is stopping me at all, I can write whatever I want and keep it to myself. But if I want to write a poem that I want other people to value, and if I want that poem to be ‘good’, and I also have the internet and am literate (99% of modern poets are in this category) then the inevitable weight of the entire canon, and all facts, and all recorded emotion, is immediately available to me. How do I write about the stars when I have no excuse to not know everything about the stars, and what a star is, and that it is to do with hydrogen and elements and energy? How do I write about the stars where I have literally instant access to every good star poem ever written? If I want to record any personal emotion then that’s fine too- but, whether or not I choose to look at it, I have endless poems at my fingertips which are probably there first for any given feeling. This is probably a dumb view of the past, but I guess in the past that you’d have to go to a library or buy hugely expensive books if you wanted to know any shit about anything, and that would be the same for all recorded poetry, and there were maybe 50 or so great poets that could potentially weigh on you. Nowadays a whole lot more people are smart, and a lot of them write things like think pieces, and short pieces of prose, and all other sorts of things that record thoughts and feelings. There’s an embarrassment of riches, even a glut, of shared personal experiences, many of which are seeking to innovate in all sorts of formal ways, in methods of delivery and in linguistics.

Information is the enemy of the poetical, and we live in the tellingly dubbed ‘information age’, and maybe that’s why modern poetry can get so weird, why proper nouns feel so strange, why directness of emotion in modern poetry is so strange to us, as all the poetry before was more obscure and difficult because it was more poetical, sometimes deliberately difficult so as to force its own category of “poetry”, but this has now fallen out of fashion, so for all sorts of reasons modern poetry gets weird, especially to the student who has read lots of old poetry.

So that’s the first part, and it ends with that idea I had. At first it sounds like it makes sense, and it sounds like it makes sense because it basically plays a trick on you. I’ve set up a faux-formula between “information weight” and “poetry” and then I increase the amount of “information”, whatever that means, and likened that to a lot of features of modern poetry which I have begun by calling “weird”, so that for a second, in my mind and the readers, it flashes as a full and powerful thought, and seems correct and elegant.

Now of course it isn’t, not least because of the innumerable oversimplifications, and lack of actual reference to information or to modern poetry or theory. It would be so fucking stupid to apply the idea I’ve articulated to a whole modern age, or to apply it too strictly in any critical sense.

But that moment for which it seems true, or when it seems like there might be a nugget of truth in it, isn’t actually false. Of course its true that there’s some things that you now can’t do in poetry, that you don’t have excuses to not know without seeming quaint, and it’s true that as we move forward you can’t do things that you could do in the past, even though you can only ever read the past and never read the future. So tradition, traditionally poetical poetry, is in fact a weight on the modern author. And in that sense, thinking about information handling in modern poetry is valuable.

This is the angle that must be held in mind when you think about overbearing critical sentences. Let’s look at one from Paul Fussel:

“Lord Derby’s “scheme”- a genteel form of conscription- was promulgated, and at the beginning of 1916, with the passing of the Military Service Act, England began to train her first conscript army, an event which could be said to mark the beginning of the modern world.”

So... no, right? That’s stupid. How does that mark the beginning of the modern world? Whose modern world? A Western centric one? An anglo-centric one? Even then it was just one part of a much bigger picture. There are lots of things wrong with that line. But it’s also godlike, because of course, of course of course, it DOES mark the beginning of the modern world. How could it not? It’s the England which we think of as friendly FORCING people to go to war. It’s so unthinkable that it must be momentous, and must mark a point more than any other point where something absolute crazy, life changing and huge has occured. It’s ponderable. It makes you think about what it means to live when we live now, it drives home the idea that we live in an age which is partially a consequence of the various fallouts from an event in which the government of the country we live in had to force people who lived in it to be soldiers.

Let’s do another, because these sorts of things are very exciting to me.

“Most of our understanding of the will are Will’s, as it were, because Shakespeare invented the domain of those metaphors of willing that Freud named the drives of Love and Death.”

Fuck off. That’s just nonsense. The history of human understanding isn’t the consequence of two guys. Freud read Shakespeare but his reading was more various too. Shakespeare wrote popular plays first and foremost, etc. But of course, this is also very useful, and maybe even true- humans think as a consequence of the huge intertexts they sit in, and a lot of the intertext formation can be formed by two very influential writers. It makes us think about its own terms, the idea that the writer thinks that our spaces of thought are justifiably defined entirely by the authors who did that space of thought best. He does it so assertively we can think about why one might be so certain about that, why we might not be able to disagree if we wanted to.

Like the Fussel, this is something which is hard to apply apart from very sparingly, and very thoughtfully and carefully. Large studies tend to end with these sorts of declarations because they’re pieces of poetry, but the book is longer than one sentence, even if that’s the takeaway sentence, because not all of the value is held in that sentence. Still, it’s ponderable.

Ponderable is a golden world. We use it when we mean something which isn’t write, which oversteps its boundaries, but which leads in to other ideas, and which has some sort of truth near it. Ponderable is a big part of a lot of the best criticism that is really criticism and not just literary science or literary history. It might also be the best part.

Love,

Alex

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Manifesto by Harmony Holiday

https://poetrysociety.org.uk/manifesto-harmony-holiday/

- - -

I am inside somebody who loves me. I can’t help but hear Whitney Houston’s proclamation, I wanna dance with somebody, with somebody who loves me when I announce that, that’s the pitch it accesses, and it’s accurate, I want to take myself dancing and poetic language allows it, although the deliberate confession I launched into the dance with derives from a desire to revise or refuse the truth Amiri Baraka offered in his poem ‘An Agony. As Now’ when he wrote I am inside someone / who hates me. No. Not anymore. Not today. No more patient and methodical self-sabotage or effort to feel my way into brown skin with self-loathing as the neural-transmission. No more shrill militancy to protect us from our private sense of helpless sublimation. I am inside somebody who loves me. She would kill for me. She writes in order to avoid having to murder the ones who are inside somebody who hates them. As an act of love she addresses their pathology with reckless authority and most of all, movement, a way of penetrating space that refuses to close the self to the self, that is no longer complicit with being held hostage behind self-inflicted enemy lines. And she understands that her position is one of luxury, that being in a black body and loving it in the West is either a lie or insane or deranged or anti-social or so electric and full of life it nearly knocks you down as it passes through you as lucid resolve, redemptive and precarious.

From that loving pact, can a poem be choreographed or improvised the way a dance can? Maybe, if it can be inhabited the way a body is, if each word and phoneme indicates a part of a living system moving through space and time with immortal intentions, if the words populate a vision and also dangle that vision over the ledge of the unknown, testing and establishing its boundaries in the same gesture. If the poem is inside of a syntax that loves it, it cannot help but propel with the grace and rigor of a spinning body. But if I am inside somebody who loves me but I articulate that love in a language that denies me, that wants me to bend to its broke-down grammar, acquire the tension of its jittery stops and starts, a showdown is brewing, some kind of revenge for the haunt of false epiphanies and memories wilting in the shade of namelessness is on the horizon.

Somewhere between the somebody who loves me and the language that tries to exploit me for my ineffable vital energy, there’s a crevice for intention/inevitable linguistic disobedience that thus obeys that love we begin with and occupy relentlessly, and there are poems lighting up that crevice and broadening it into sanctuary. The poems I love, and love to write, exact the joy of that space as retribution, reaching out with rage and tenderness for new utterance and ideas as well as for the ancient ones, on both sides casualties of colonialism, so that when we note that everywhere members of the African diaspora live, an unapologetic practice of improvisation and ‘speaking in tongues’ and dancing to go with it and religion to legalize it and jazz music to canonize it into something secular that the colonizer’s mind can openly fetishize, we realize that we are witnessing a poetics of refusal so sophisticated it passes for something verging on the folkloric. The black and brown bodies of the world refuse to follow the drab codes of western language/logic, in thought or in form, and poetry is our most effective weapon and reprove besides our actual bodies. Though I’d rather not label it war. I’d rather say I am inside somebody who loves me and I can prove it by the way she speaks of me, to me, and through me, and by the rules she refuses to follow. In not so much a hierarchy as a system, the way we move through space and time, how we treat and see our bodies, how valuable we believe we are, how free, how eager to know ourselves and reflect that knowing as being, becomes the way we think and those thoughts become the way we live especially when surrendered beyond the stage of vibration into spoken language. The low self-esteem that blackness sometimes garners can be observed in our mimicry of the colonizer’s languages and forms. As we move toward new and hybrid poetic textures that reflect the authentic rhythm of our thoughts and the highest potential of our actions and rituals, we will be moving away from somebody who hates us toward someone who loves us, is in love with us without the deranged blur of inverted rapture that would-be oppressors feel. And this love is our only duty, acting worthy of ourselves in that way is. So we write in our terrible and terrorizing and irresistible latinate or romance or patois languages, how we want to look and feel and sound and be, and that way if it’s ugly everybody’s to blame, and that way if it’s beautiful we’re orphans again, children of the sun again. Our poems are instructions in that way, and every colonized person is a poet as soon as she uses the language trying to break her in to rebuke and dismantle itself instead, to body itself, topple itself, knock that self over in loving disapproval of being muted by anyone. I crave poems like that and a world wherein they are eternally and eagerly welcomed and at last, demanded – mandated. You might be writing about three black laborers running through high grass to catch a rabbit but you also let them grab it by the neck and weep as it squeals and set it free and go hungry. Blackness defies western logic, so must the poems inside black bodies who love us enough to expose and know that ruthless interior. Migos’ ‘Walk It Talk It’ is a good anthem for these methods. Hip-hop is way ahead of literature on the freedom train but we’re busy hoppin’ cars with anti-heroic love poems for cargo, busy barging in, busy being born, busy falling in love with ourselves again and again in the sensual blank of utter alienation, everything is familiar and ripe for our liberated forms. It’s like the first time you catch a glimpse of yourself through eyes that notice and really believe, how beautiful you are, and the way that realization cannot be shut down by doubt or tentativeness ever again, and so must be lived, the poem is that moment of enchantment and its endlessly unruly future.

https://poetrysociety.org.uk/manifesto-harmony-holiday/

0 notes

Text

This summer’s most inspiring design books

Summer is a time for creative renewal, and for many of us, that means new books. 2018’s most exciting new design books have something for everyone, whether you just want to peruse coffee table eye candy or you finally have time to pore over the essays you didn’t have a chance to read during the winter. We’ve compiled some of the most compelling new and forthcoming releases, from significant design research to pure, unadulterated fun. Find the first 10 titles below, and stay tuned for part two.

Architects’ Houses

By Michael Webb

[Cover Image: Princeton Architectural Press]

What happens when an architect becomes his or her own client? That’s the premise of the projects in Architects’ Houses, which looks at the stories behind homes designed by architects for themselves. Take the husband and wife team, Antón Gargía-Abril and Débora Mesa, whose studio spent more than a year on structural calculations for their remarkable balancing act of a home. When the architect is in the driver’s seat, the typical process–and timeline–for finishing a house can easily go out the window. Often, that’s what makes these buildings so worthy of our attention.

$41.82 on Amazon

California Captured

By Marvin Rand, Emily Bills, Sam Lubell, and Pierluigi Serraino

[Cover Image: Phaidon]

Marvin Rand is the most famous architectural photographer you’ve never heard of. Like his better-known peer Julius Shulman, Rand chronicled the aspirational architecture of mid-20th century California, but his work remained largely unknown until 2012, when journalist Sam Lubell discovered an archive of more than 50,000 of the photographer’s negatives and transparencies. California Captured (Phaidon) showcases nearly 250 of these images. Sleek, single-family homes by architects such as Richard Neutra, Craig Ellwood, and John Lautner figure prominently, in addition to Googie landmarks like the Theme Building at LAX and Tiny Naylor’s drive-through–all rendered in Rand’s crisp, unfussy style.

$40.19 on Amazon

California Crazy: American Pop Architecture

By Jim Heimann

[Cover Image: Taschen]

Almost 40 years ago, Jim Heimann published a book called California Crazy. It brought the state’s folly-filled pop architecture to the mainstream, documenting its theme parks, fast-food stands, and roadside buildings. In June, the book is being republished anew. It still features page after page of rich, archival photos of countless SoCal typologies–from buildings shaped like pumpkins, cameras, and ice cream cones, to studio sets and faux castles. But Heimann also reflects on what makes California such fertile ground for architectural experimentation and the “dicey business” of preservation, including how the first edition inspired new research into many of these formerly obscure structures (some of which no longer exist). Here’s hoping that the 40-year-update will become a regular thing.

$60 preorder on Amazon.

Coffee Lids: Peel, Pinch, Pucker, Puncture

By Louise Harpman and Scott Specht

[Cover Image: Princeton Architectural Press]

Did you know the Smithsonian has more than 50 coffee cup lids in its permanent collection? Thanks to the work of architects Louise Harpman and Scott Specht, who have been collecting lids for years, this form of “invisible” design will be preserved forever. The duo’s new book about the typology, titled simply Coffee Lids, is a glimpse into the depthless variation and ingenuity of an object that few people have ever even considered. “Looking something as simple as a humble coffee lid is an entry into that conversation,” Harpman told Co.Design‘s Katharine Schwab, “to slow down, take notice, wonder, ask questions–what is that, how is it made, who designed it?”

$18.08 on Amazon.

How To Make Repeat Patterns: A Guide for Designers, Architects and Artists

By Paul Jackson

[Cover Image: Laurence King Publishing]

Channel your inner M.C. Escher with How To Make Repeat Patterns (Laurence King). The guide, by paper artist Paul Jackson, reveals the rules of symmetry that undergird complex patterns and offers tips for producing your own designs, whether for wallpaper, architectural facades, or digital products.

$24.33 on Amazon

Inside North Korea

By Oliver Wainwright

[Cover Image: Taschen]

The humans in Oliver Wainwright’s photos of North Korean buildings look like scale models: Tiny figures, invariably dressed in drab tones, that serve only to underline the yawning size and shimmering jewel-tones of Pyongyang’s architecture. “It looks as if someone has emptied a packet of candy across the city, sugary pastilles jumbled up with jelly spaceships,” writes Wainwright, the Guardian architecture critic who visited the country on a tour in 2015, when he shot the photos in this Taschen tome that will be released in August. Unlike most accounts of the city, Inside North Korea (Taschen) offers a thoughtful analysis of Pyongyang’s urban history, situating its widely photographed architecture in context with the Kim dynasty and the way it seeks to articulate its goals through building. It’s sobering, and mesmerizing, at the same time.

$60 preorder on Amazon.

Lorna Simpson Collages

By Lorna Simpson

[Cover Image: Chronicle Books]

The collages in this monograph are a revelation. Artist Lorna Simpson takes models from vintage Ebony and Jet ads and gives them elaborate new hairstyles, using ink washes, geological formations, and other mysterious imagery. The book features 160 artworks that, together, form a meditation on the language of hair and black identity. As poet Elizabeth Alexander writes in the introduction: “The repetitions in these images suggest that we are thought of by some as a dime a dozen: undervalued, yes, but also, abundant. Black women are everywhere glorious and unsung.”

$29.95 preorder on Amazon.

Shakespeare Dwelling: Designs for the Theater of Life

By Julia Reinhard Lupton

[Cover Image: University of Chicago Press]

This inventive book by an English and comparative literature professor at UC Irvine examines the spaces that bring Shakespeare’s tales to life. Author Julia Reinhard Lupton analyzes dwellings in five classic works–Romeo and Juliet, Macbeth, Pericles, Cymbeline, and The Winter’s Tale–and draws on theory from the likes of Martin Heidegger and Don Norman to offer insight into everything from “the ethics of habitation and hospitality” to “the literary dimensions of design.”

$27.50 on Amazon.

Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours: Adapted to Zoology, Botany, Chemistry, Mineralogy, Anatomy, and the Arts

By Patrick Syme and Abraham Gottlob Werner

[Cover Image: Smithsonian Books]

Skimmed-milk white. Arterial blood red. Celandine green. In the 19th century, naturalists were struggling to standardize the colors they observed in nature–without the utility of post-Industrial Revolution digital precision of CMYK or RGB. Werner’s Nomenclature Of Colours, published in 1814, gave scientists, artists, and naturalists a common language to talk about color–even Darwin famously used the color dictionary on his travels. This spring, the Smithsonian re-released the book in a small, pocket-sized version, perfect for travelers or anyone who spends time outdoors. It’s an evocative creative document–and a lovely antidote to life lived online.

$13.46 on Amazon.

Women Design

By Libby Sellers

[Cover Image: Frances Lincoln]

Women Design (Frances Lincoln) assumes the Herculean task of highlighting women’s contributions to design–including architecture, industrial design, digital design, and graphics–from the 20th century to the present day. It has no business being just 176 pages, but author Libby Sellers, a prominent British gallerist and curator, manages to pack a wealth of information in profiles of 21 women designers. Historic pioneers such as Denise Scott Brown, Ray Eames, and Lella Vignelli get their due, as well as contemporary stars like Neri Oxman, Patricia Urquiola, and Kazuyo Sejima. “Women have always been, and remain, a significant part of the design profession,” Sellers writes. “…Yet, if asked to name the design world’s greats, most people would produce a list of predominantly male names.” This book attempts to correct the narrative, and it tells some rollicking stories along the way. Be sure to check out the section on the “Damsels of Design,” a group of women industrial designers GM hired to address what a 1957 press release described as “woman driver’s problems” like “anything in cars that might snag their nylons.”

$30 preorder on Amazon.

This summer’s most inspiring design books published first on https://petrotekb.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

George William Russell (AE) - Writer, Painter, Philosopher, Social Activist

by Arthur Russell

George William Russell was born in the rural townland of Drumgor, near the town of Lurgan, Co Armagh, Northern Ireland on April 10th 1867 to Thomas Elias Russell and Mary (nee Armstrong). He was baptized in the nearby Shankill church. He was the youngest of three children; a brother Thomas Samuel who was 3 years older and sister Mary Elizabeth, who was one year older. When he was 11 years old, the family moved to Dublin to allow father Thomas to take up a new job in a brewery. George was sent to the Metropolitan School of Art where he befriended the principal teacher's son, William Butler Yeats, who was destined to become the brightest light of the Irish Literary revival as well as a future Nobel prize winner for literature.

When George was 17, the Russell family was dealt a severe blow with the death of his sister Mary Elizabeth. The poignant poem "A Memory" gives indication of how her death affected him, and was an early indication of his writing talent.

You remember dear together

Two children you and I

Sat once in the Autumn weather

Watching the Autumn sky

There was someone around us straying

The whole of the long day through

Who seemed to say, "I am playing

At hide and seek with you"

And one thing after another

Was whispered out of the air

How God was a great big brother

Whose home is everywhere

His light like a smile comes glancing

Through the cool winds as they pass

From the flowers in heaven dancing

To the stars that shine in the grass

The heart of the wise was beating

Sweet sweet in our hearts that day

And many a thought came fleeting

And fancies solemn and gay

We were grave in our ways divining

How childhood was taking wings

And the wonderful world was shining

With vast eternal things.

His Cooperative Work

After leaving Art School, where he developed his painting skills, but obviously not enough to consider taking up painting as a full time profession capable of giving him an income, he went to work in his father's employer's brewery. Later he became a clerk in Pim's drapery store in Dublin, where he was earning 60 pounds sterling per annum by the time he resigned to join the budding Irish Cooperative and Credit Union movements at the invitation of the Irish Agricultural Organisation Society (IAOS) founder, Sir Horace Plunkett. His first job with IAOS was as Banks Organiser, but his writing ability soon saw him contributing to and then editing the Society's magazine The Irish Homestead which later merged with The Irish Statesman. He had a strong social sense and threw himself wholeheartedly into the development of the Cooperative movement as a means of supporting the economic development and market integration of emergent small holder proprietors that the various Land Purchase Acts were creating all over Ireland at the time. His cooperative work brought him to every part of Ireland, most of which still had searing and recent memories of famine and eviction which were seen as outcomes of the centuries old landlord system of land ownership in Ireland.

He edited the IAOS publication until 1930, which provided him with an outlet to display his writing talents as well as giving him a facility to mix the practical with the visionary (the vision and the dream). His boyhood experience as the son of a small holder farming community in Armagh helped him to provide well grounded technical advice to his farmer readers, at the same time giving him opportunity to outline philosophical thoughts on what the social and political future for his rural readers might be. He was sought after as a speaker lecturer not only in Ireland, but also in the United Kingdom and pre and post Depression era United States of the 1920's and 1930's.

After his death in England in 1935, his body was returned to Dublin and lay in state for a day in Plunkett House, headquarters of IAOS, before it was brought to Mount Jerome cemetery for burial.

His Literary Work

Cover of AE's first publication (1894)

Drawing by the author

His first book of poems, Homeward: Songs by the Way, published in 1894, established George William Russell as one of the leading lights of the Irish Literary Revival. His friend W B Yeats considered this little book as one of the most important literary offerings of the day.

The Origin of His Pseudonym "AE"

As his literary reputation grew he adopted the pseudonym "AE", derived from the word Aeon. This is a gnostic term used to describe the first created being. The story is told that his printer had difficulty deciphering Russell's handwriting and could only discern the first two letters of the 4 letter word in his manuscript. When asked to clarify the remaining two letters of the word, Russell decided not to add to what had already been composited by the printer and thereafter used AE to sign off on all subsequent offerings. His mystic disposition had earlier caused him to join the small Theosophist movement in Dublin for several years, but he left after the death of its founder, Madame Blavatsky. While living there he met his future wife, Violet North and married her in 1897. The couple lived for some time in Coulson Avenue where they were neighbours to Maude Gonne and Count and Countess Markiewicz.

He was an active member and contributor to the Irish Literary Society, which was founded by his friend W B Yeats and others. The early moving force for the literary movement was the writings of Standish O'Grady who looked at Ireland's romantic past for inspiration. On reading O'Grady, Russell was moved to write "one suddenly feels ancient memories rushing at him and knows he was born in a royal house - it was the memory of race which rose up within me."

His Theatrical Work

Yeats and Russell shared a passion for the theatre and together they formed the National Theatre Company, later called the Abbey Theatre in Dublin. Yeats was President, Russell Vice-President and among the Committee members were Maud Gonne and the Gaelic language scholar and later first President of the Republic of Ireland, Douglas Hyde. Russell's play Deirdre is credited to have been the spark that set the Irish dramatic movement alight. Not only did he write the play, he also designed the costumes in its first production. His brilliant but eccentric personality contributed mightily to the evolving Irish literary revival, which is popularly referred to as the "Celtic twilight".

His Paintings:

Bathers - by AE (exhibited in 1904)

Russell had a talent for painting, which he followed during his life, mainly for his own recreation "whenever words failed him". There is a respectable gallery of his works which would lead one to question how good and enduring his painting legacy would be if he had invested more time and effort into that side of his output. We will never know. Suffice it to say, his paintings have a significant market and are well regarded by many.

The Irish Times newspaper, on the occasion of the centenary of the first exhibition of his paintings in 1904 at which he sold an amazing 68 paintings – many to the noted New York art collector, John Tobin; suggested it is high time for another exhibition to create awareness and appreciation of AE's art.

Russell the Social Activist

He was destined to live through troubled times in Ireland and much change. The first two decades of the 20th century were the final years of the British Empire in Ireland and ushered in the formative years of the new Irish Free State that emerged in the aftermath of the Irish War of Independence in 1919-1921. It was never in Russell's nature to be a mere bystander or spectator in the movements of his times, and he engaged fully in trying to formulate what kind of Ireland would face into the last century of the millennium. As a visionary, poet, painter, author, journalist, economist and (finally) an agricultural expert he had views aplenty and was never slow to express them with great articulation and conviction.

He was involved in the general strike of 1913 and took part in a mass meeting in Albert Hall London in support of the Dublin strikers, where he shared the platform with George Bernard Shaw and suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst. He was an Irish Nationalist, but as a committed pacifist he deplored the violence of the Nationalist inspired Dublin Rebellion in Easter 1916. This did not stop him from organising a subscription for the widow of one of the executed leaders, James Connolly, who he had befriended during the 1913 strike; both men having shared views on how to deal with the exploitative attitude of many employers of the time.

The following lines written by Russell indicates something of the dilemma he and many pacifist nationalists of the day felt. He could admire the idealism of those who followed Patrick Pearse in taking up the gun in pursuit of nationalist ideals, but like many others he had serious issues with bloodletting as a means to achieve them.

"And yet my spirit rose in pride

Refashioning in burnished gold

The images of those who died

Or were shut up in penal cell

Here's to you Pearse, your dream, not mine

And yet the thought- for this you fell

Has turned life's water into wine".

(from To the memory of some I knew who are dead and loved Ireland - 1917)

He was conscious his adherence to non main stream views and opinions at a time when the extremes on both sides of the political divide were in clear ascendancy, drew sharp criticism from many, but he remained stoically unapologetic for his pacifism through that most turbulent period of Irish history.

On Behalf of Some Irishmen Not Followers of Tradition

They call us aliens we are told

Because our wayward visions stray

From that dim banner they unfold

The dreams of worn out yesterday.

We hold the Ireland of the heart

More than the land our eyes have seen

And love the goal for which we start

More than the tale of what has been.

No blazoned banner we unfold

One charge alone we give to youth

Against the sceptred myth to hold

The golden heresy of truth.

His Relationship With the Newly Independent Irish State

George William Russell was disappointed that Irish independence was painfully slow in bringing the cultural and social flowering for which he yearned. He was of the opinion that the emerging rather puritanical state with its narrow vision, of which censorship of arts and writing was one of its most potent instruments, effectively blocked intellectual and artistic freedom as it tried to establish the new nation during the 1920s and 30s. He was particularly critical of the excessive influence the Catholic Hierarchy had manage to establish over the emergent body politic. It was his discomfort with this, along with the death of his wife a year earlier that caused him to leave Ireland in the aftermath of the 1932 Eucharistic Congress which was held in Dublin and which he considered a potent demonstration of over pervasive clerical power.

He moved to Bournemouth in England where he died in 1935.

His Support to Young Writers and Artists

During his years in Dublin, his company was much sought after and his home in Rathgar Avenue, Dublin became a meeting place for those interested in the Arts and Economics. He paid special attention to young talent, which he did all in his power to groom and encourage.

He was an endless source of support and advice to emerging writers. He first met James Joyce in 1902 and encouraged him to hone his craft as a writer. He once loaned him money, which Joyce acknowledged pithily with a written "AEIOU".

One of his lesser known acts was to support the American writer Pamela Lyndon Travers, the future author of Mary Poppins (published 1934) at a time when her interest in myths brought her into contact with both Yeats and himself in 1924. AE encouraged her to write and even published some of her writings in The Irish Statesman.

Simone Tery the French writer in L'ile des Bards wrote about him:

"Do you want to know about providence, the origin of the universe, the end of the universe?

Go to AE.

Do you want to know about Gaelic literature?

Go to AE.

Do you want to know about the Celtic soul?

Go to AE.

Do you want to know about Irish History?

Go to AE.

Do you want to know about the export of eggs?

Go to AE.

Do you want to know how to run society?

Go to AE.

If you find life insipid -

Go to AE.

If you need a friend -

Go to AE.

These lines from a contemporary are a fitting accolade for one of Ireland's not so well known writers who played a vital role in what is now known as the Celtic revival.

Author's Note – While I had always been aware of George William Russell, otherwise known as AE, with whom I share a surname: I was not so aware of any family connection with him until very recently, when a distant cousin with interest in genealogy put focus on a lady called Frances Mary McGee, whose mother was a daughter of our common great grandfather. This lady married the brother of George William (AE), and while his surname was also Russell, Thomas Elias was not directly related to "our" Russells. (At least we need to go much further back to find any blood linkage). This information about Frances Mary caused me to remember conversations in my own family about a distant cousin called Fanny (short for Frances) McGee, second cousin to my father who had married into a family associated with artists and poets. Who else could it have been?

It was a personal Eureka moment, as I share some of AE's interests (though not necessarily his unique talent) for reading, writing, (I really know little about painting!) As well I share a strong belief in the positive role of self-help cooperative endeavor for solving problems facing Agriculture in feeding today's World's burgeoning population.

Arthur Russell is the Author of Morgallion, a novel set in medieval Ireland during the Invasion of Ireland in 1314 by the Scottish army led by Edward deBruce, the last crowned King of Ireland. It tells the story of Cormac MacLochlainn, a young man from the Gaelic crannóg community of Moynagh and how he, his family and his dreams endured and survived that turbulent period of history. Morgallion was awarded the indieBRAG Medallion and is available in paperback and e-book form.

Further information from [email protected]

Hat Tip To: English Historical Fiction Authors

0 notes

Conversation

An Interview with Meena Alexander

This interview took place at the Graduate Center, City University of New York on February 25 and 28, 2005.