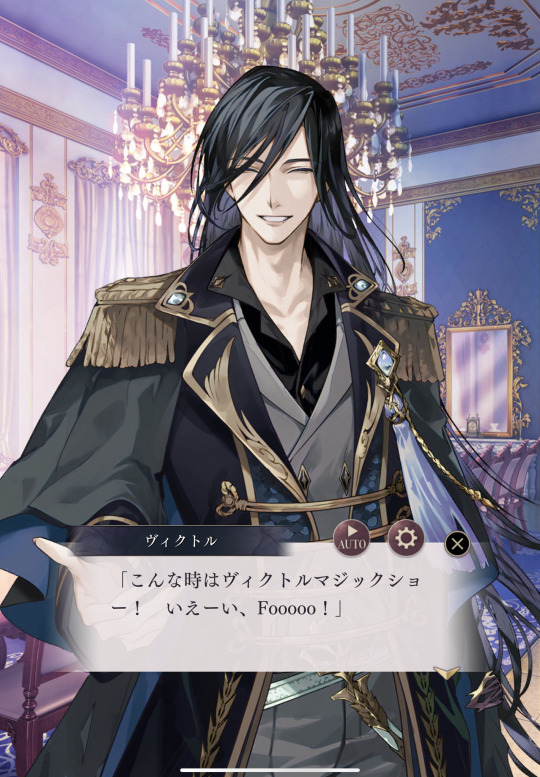

#he wanted to summon flowers but released pigeons instead

Text

Fooooo!!

#he’s doing a ‘magic show’#he wanted to summon flowers but released pigeons instead#wHere is he KEEPING THE PIGEONS WHAT#alt rambles#alt loves victor

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Varieties of Tea

Apprentice Xanthioppe (Xan) has an unpleasant dream involving her feelings about a certain someone’s chronic absentee-ism, and she deals with it. Kind of badly. Well-- very badly.

1850 words, Asra/Apprentice if you squint, teen rating by AO3

-

Pazu carried her. The high sun dug into their back, no doubt setting their black plumage ablaze with a dark beetle’s gleam. A strong headwind trickled through their wings’ plumage and spilled down the rocky outcropping and down, down onto the dry steppe floor. Their eyes were at once up on the mountain where they perched and also down amongst the scree and the scrabble and the holding-their-breath-nonmovements of lesser life. Prey.

But not all prey was equal. Pazu would not consider the mice and the insects, the vermin favored by others. He stalked the other winged things that ate like prey. He would climb to heights they would never dare and plunge through the thick and heavy air upon the lesser-bird and sink his talons into their too-late-aware flesh.

Ground life was trickier. But he liked the big, soft prey that could fight back sometimes and possibly hurt him. He liked the delight Xan expressed every time he dropped a lean rabbit at her feet.

Pazu carried her, and they bent with tensing muscles into the wind. They dropped from the outcropping, plummeting along the mountain’s surface until their wings pushed against the air and set them upright. They flapped, flexing hard down into their chest. They circled up on warm gusts.

The steppe stretched out below them. In one direction, the rocky ground softened to the Endless Sand With Hard Hunting. In the other direction sat the Close Places Where Xan Lived.

They glided up and up, skimming over warmth and dipping a wing slightly to avoid cold spots. Up and up they climbed, into the white sun. Their eyes raked over the faraway ground. They watched the rippling silk of dry grass in the wind. Xan felt Pazu’s instant dismissal and disdain for the desert rats scampering for cover. If pushed, he would eat them, but he was young and skilled and better hunting was plentiful.

A flash of unusual color snared their eyes. A swift shape slipped from shadow to shadow. Brilliant and unlike the dull brown rats and mice scattered in the grasses.

Xan’s chest tightened and her head clouded. Pazu flicked the tip of a wing, tightening the broad circle they’d been coasting on. He, for once, cautioned her. They could not yet dive until they were sure. Still, Xan’s heart-- their heart-- spasmed violently in their chest.

They followed the bright prey, whirling and watching. Their mark met a stretch of bare land several lengths from any cover. And instead of turning back, it slipped onto the grassless scree.

Pazu and Xan dropped. They fell and fell until the wind battered them and the flinty air cut at their eyes. As the ground neared, they leaned back into the drop and unfurled their talons.

The long, smooth-skinned prey made no sound as they plucked it up. Xan felt her head pound like a gong. She wanted to scream and curse and strangle. Instead, Pazu screeched as her emotions swept over him.

Darkness rushed in, or perhaps it had always been there. No sun, no moon or stars with which to see their blue captive. An empty void smothered them. Their prey somehow pushed open their talons’ grip-- but, no, it was thickening.

The snake grew impossibly heavy for them to clutch. But there was no up or down to drop it on. Implacable weight coiled around them, squeezing. Pazu shrieked again and writhed, rending stoneflesh with talon and beak. Xan raged. She screamed soundlessly. She thrust out ghost limbs.

The snake strangled them.

-

Xan woke. She released a shuddery breath and slapped at her sweaty brow.

Damn it all.

The sun peeked up over the earth’s edge, nudging up into a pink and grey sky. The light in her little second story loft coated everything with a soft and dim glow. She kicked away her blanket and pushed damp hair off her neck. Beside her bed, Pazu turned an inquisitive head toward her.

She stood and reached for him. Even hooded, he easily hopped from his perch onto her hand. His talons pushed into her bare skin almost to the point of pain, but she ignored it and smoothed down the speckled plumes on his chest. He cocked his head at her again.

“I’m fine,” Xan said.

He chirped.

“Well, I will be.”

He stared at her, and through the hood she could sense his thoughts. If something displeases you, fly away. Or kill it.

“It was a dream. Not a vision of the future, just a reflection of emotions.”

He chirped again. If a lifegiver is no longer a lifegiver, then they are predator. Or prey. Either way, kill them.

“It’s not that simple,” she said. “And you don’t have to always be so murder-y.”

He chirped. He was hungry.

She crossed the room to the roof ladder, grabbing her leather gauntlet on the way and slipping it on. Pazu transferred to the gloved hand. She climbed up and pushed at the trap door above with her magic. It sprang open. Cool, soothing air enveloped her.

It felt good against her back-stabbing murderer’s flesh.

Pushing that thought away, she padded between the garden boxes to the low wall edging the roof. Pazu radiated anticipation. She pulled the tall horsehair plume of his hood, slipping it off. His bright, yellow-rimmed eyes shone at her and at the world around them. Life was simple. You hunted, and you came home to the lifegiver.

Xan held her arm straight and aloft. Almost instantly, Pazu lifted his wings and leapt into the air. She watched him disappear into the sky for a while until she shivered with the cool air biting at her bare limbs. She hadn’t even grabbed a shawl.

At her wash stand, she poured out water into the basin as usual. But her eyes clung to her hands and the sloshing water, her sight skittering away from the ornate mirror on the wall. Her stomach churned and her pulse raced. The idea of crawling back into bed and burrowing under cover tempted her sorely.

Instead, she climbed down to the ground floor, actually glad that Asra’s room sat empty yet again. She wouldn’t have to face him or Faust-- today at least. Ugh, she couldn’t even imagine.

No, don’t think about that. Definitely don’t think about Faust’s sweet little face or her curious little tongue.

Xan tightened her grip on the shawl around her and went into the kitchen in the back. Maybe a cup of tea would settle her down. Instinctively, she reached for the porcelain container with the blue and emerald pattern, worn at the edges from the constant touch of fingers. She opened it and looked inside. The deep scent of smoke, touched with an herbal bitterness, wafted up into her face.

She could remember almost perfectly the first cup of this that Asra had brewed for her. The way his pretty hands carefully measured out the blackish tea leaves into the infuser. The soft smile he gave her as he tipped the pot over her cup. That infinitely heady and acrid taste and smell as she watched his eyes attend to her.

Xan clapped the lid back onto the container, nearly cracking it. Unbidden magical sparks shot across her skin. She shoved the tea back onto its shelf, whirling away.

No. Dammit, no!

Her feet sliding on the tiles, she grabbed the container again. Stomping, she burst back into the front shop area, ducked behind the counter, and snatched up her bag. She at least had the presence of mind to slap at the front door’s protective ward as she strode out into the street.

Xan wove through the streets and alleys, her hard feet hitting the pavement with increasing speed. A tight covered walkway spat her out into an open palazzo. In the center, a fountain bubbled away with disgusting cheerfulness. Ugh! She sprinted forward, reared back her hand, and hurled the tea container into the fountain with deadly (read: magical) force. Sparkling water geysered up and spilled over into the square.

“You stupid jerk!” she shrilled.

An old man that had been sitting by the fountain, feeding pigeons, stared at her through dripping strands of overlong eyebrows. A collection of pigeons squawked, sad and wet, at his feet.

“What are you looking at?” she snarled at him.

He studiously went back to dropping soggy bread at the soggy birds.

Xan heaved. She could imagine what she looked like: her amber legs and arms naked as she only wore her bodysuit and her shawl, her feet bare and dirty from her march through town, her black hair wild. Chucking tea containers into fountains. Whatever! She was a witch, who gives a shit!

She re-slung her shawl about her in a dignified manner and stalked across the square. She ignored the other gawkers. Maybe Pazu was right. If someone stops being a lifegiver, a source of comfort and care, then what are they? Huh? A stupid jerk, that’s what!

The other part-- the murder-y bit-- he was probably wrong about, though. Probably.

Down a side street and turning left, Xan unceremoniously rapped a sharp summons on the locked door of her usual tea shop. After a moment, the proprietor poked their head out.

“Xan?” they asked, eyeing her. “Are you alright?”

“I need tea. Urgently,” she said.

The shopkeep opened their mouth, closed it. “Well. Okay…”

Xan swept past them as the door wedged open.

“Lapsang souchong, right?” they asked.

She ignored them and stood staring at the wall of large jars full of leaves of varying shades of green. Emerald, chartreuse, jade. And the occasional bloom of yellow and pink and lavender: dried flowers and herbs. Xan turned to the proprietor.

“A few coppers worth of everything,” she said.

They blinked. “Everything?”

“Everything.”

“Are… are you sure you’re alright?”

“Everything!”

Hesitantly, they began pulling down the heavy jars, all the while giving her the side-eye. Xan huffed and heaved out some jars herself. When they got to the lapsang souchong, she pointed imperiously.

“Not that!”

They stared at her, hands hovering over the black twisting leaves. “What?”

“Not that,” she repeated.

The shopkeep sighed and went back to the dozens of other varieties of tea. Leaving a generous tip for future sales when she wasn’t acting like a complete loon (and also wasn’t half-naked), Xan exited the shop with a hefty canvas bag full of little bags of probably every form of tea known to man. At home, she left the lantern by the front door unlit and locked the shop up. After washing her feet, she set out to brew cups of everything. Everything. By the day’s end she had terrible stomach cramps for her troubles.

-

“Xan,” Asra asked from the kitchen, “Have you seen the lapsang souchong?”

“How should I know! I don’t drink that!”

He poked his head around the corner. A gentle raised brow and smile played over his features.

“But it’s your fav--”

“Get out and buy some if it’s that important to you! And don’t use the shop’s petty cash!”

#the arcana#the arcana game#fanfiction#my writing#asra#apprentice#what's a period-appropriate term for a bodysuit?#bc that was the best i could come up with#i mean leotard?? unitard??#they're all awful#excessive exclamation marks!!! how uncouth#yea i dgaf!#i gotta problem w stylistic authority!!!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Outside a Man Yelled Relax

By Joanna C. Valente, Angelo Colavita, Eric A. Ammon, Viannah E. Duncan, & Lisa Henning

This is a collaborative poem written during our Collaborative Poetry Workshop (hosted on April 25th) taught by Joanna C. Valente and Angelo Colavita. Both the hosts and participants in the class worked on this poem.

TWENTY-FIVE

Outside a man yelled relax

didn’t stop but kept moving

still like breath moves through water

through twenty-five years

of age or of

days long passed

long ago (I was just

swimming, yes by a river bank

wrapped, if you will in plastic

me, not

the river

So holy yet so

filthy

to move as one

only

as dirty as the lonely world

allows.

For twenty-five years, the earth surrounds me

fights &

finds me in twenty-five days, a still life) among the watered trees

and a basket of fruit

a flower

a landscape my grandfather

and myself in a chair

an open window to

the outside.

Outside the universe on a planet

like ours but we haven’t

torn it apart yet

to erase it of

what we consider beauty

like reckless children

who say to relax and who even says relax anymore. That’s the last thing

I want to hear

in uncanny valleys, void of

light or sound.

The damp grass

around a loud grave no name written

except relax and the sound of

arguments in line

breaks

and bones cracking and nails scraping

of an aged body of twenty-five years

that I summon

inhale from

the base of

my tired feet

with fire breath

I speak

but it went to the wind

instead and stood shadows in place

inside no place

under shadowless sun.

Eric A. Ammon is a Philadelphia-based poet focused on processing trauma and communal healing through allegory, symbolism, and imagery. He uses his dissociation and anxiety as a technique within his writing style, evident in his sudden shifts in meter and airy subject matter, to empower identity rather than suppress it .

Viannah E. Duncan is a professional editor for academic, corporate, and creative writers. Her creative nonfiction and poetry can be found in Lavender Review, Screen Door Review, Flypaper Magazine, the Same, Eclipse, and other small literary journals. She lives outside of Washington, DC, and holds an MFA in creative writing with a focus on poetry, creative nonfiction, and small press publishing. You can find out more about her and her editing services at Duncan Heights (http://www.duncanheights.com).

Lisa Henning is a poet from cold and snowy central Minnesota. Poetry keeps her warm. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and submits her work for publication occasionally. For the last three years she has been working on a book of poetry that hopes to inspire others.

Joanna C. Valente is a human who lives in Brooklyn, New York. They are the author of several collections, including Marys of the Sea, #Survivor, (forthcoming, The Operating System), Killer Bob: A Love Story (forthcoming, Vegetarian Alcoholic Press), and is the editor of A Shadow Map: Writing by Survivors of Sexual Assault. Joanna is the founder of Yes Poetry and the senior managing editor for Luna Luna Magazine. Some of their work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Rumpus, Them, Brooklyn Magazine, BUST, F(r)iction, Ravishly, and elsewhere. joannavalente.com / Twitter: @joannasaid / IG: joannacvalente / FB: joannacvalente

Angelo Colavita is a writer from Philadelphia, PA, where he serves as Founding Editor of Empty Set Press and Associate Editor at Occulum Journal. He is the author of two collections of poetry — Flowersonnets (ESP 2018), Heroines (ESP 2017) — with work appearing or forthcoming in the Operating System’s ExSpecPo series, Pigeon: A Radical Animal Reader vol. 2, Mookychick, Madcap Review, Prolit Magazine, Metatron, Dream Pop Journal, South Broadway Ghost Society, Luna Luna Magazine, Yes Poetry, Apiary Magazine, and elsewhere online and in print. His forthcoming epic poem, Nazareth, will be released by APEP Publications in 2020. For more information, please visit www.angelocolavita.com or follow him on Twitter @angeloremipsum and on Instagram @angelocolavita.

#Viannah E. Duncan#Eric A. Ammon#joanna c valente#Angelo Colavita#lisa henning#poetry#special feature#collaborative poem

0 notes

Text

A Savannah Site for Emily

She isn’t in the Bonaventure or anywhere nearby the grave of Jim Williams. She wouldn’t have tolerated such positioning. Emily took a stand against the man years ago and wrote it down word for word with a working title of Cannabis and Snowdrops, mainly because her son Danny loved both. Her story is not a sequel to Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, though it tells of the aftermath; nor is it a prequel, though it tells of what happened in the years leading up to that fatal midnight. Rather, it is a kind of circling-and-spiraling, which I think of as Around Midnight. And, her story will likely never see the light of day.

In my most recent visit to her grave, the memories of having her as my student over three years poured out. One thing a creative writing teacher must never do is speak of his or her students’ stories in public, unless of course those writers have made their works public. For me that discretion ranks among the rules of priests, therapists and lawyers. And I would hesitate to speak now except for Emily’s prodding. She is as determined as she sleeps in Greenwich Cemetery as she was wide-eyed in my class.

“It’s fiction,” she had taunted from the back of the room that first day she was in my class and whenever I held up Berent’s book or mentioned the title. The thin sassy voice came with rich Savannah accent, from a pugnacious figure then totally unknown to me, one which I was not about to take on in front of my class of urbane aspiring writers.

“Fiction!” came again as loud as a whisper allows. After several more taunts from her it occurred to me that no matter who she is she might have something to add to my lecture on creative nonfiction or on the works that seem to be settling as the benchmarks of the sometimes wooly genre. Little did I know that over time she would modify my teaching of the topic of creative nonfiction, transform my perspective on issues of notoriety and on loss, and teach me much about voice driven writing styles.

Her writing was well underway when she entered my classes. Not a reaction to Berendt’s book, hers is the story of growing up as a “have not” in a world of powerful “haves” in the thick moss and mist of Savannah. Hers is the battle of growing up in the shadow of father old enough to be her grandfather and who gave her off in marriage at a young age, of raising four children virtually alone, of a dogged resistance to growing up ignorant just because you are poor, and of having a son shot to death in the home of millionaire on Bull Street. Emily’s story, written or unwritten, currently sits in the shadow of Midnight, just as she often had sat in dim corridors of the Savannah courthouse because she was not permitted in the court room while the trials went on. Nevertheless, to those who know it her story stands out in factuality and mesmerizing style.

Emily had written much of her story while she was in Savannah, long before she appeared in my class in 2002. The narrative had poured out of her in a compelling voice that few writers find the freedom to release. She wrote about and told us about her unfortunate experiences with people associated with writing and film making. In fact, some such episodes were in her manuscript. I suggested she be careful to not put herself in the position of describing situations that she might not be able to back up in the event someone decided to sue. My statement felt flimsy as it came out of my mouth, directed at a woman who’d lived through infamous trials of conviction and reversal of conviction of the Jim Williams. Williams had money, she pointed out to me, but she barely had “a pot to pee in.” Who could possibly sue her, and what would they get? But, she did take most of those questionable episodes out of her writing.

At first, Emily’s story was bogged down with the inclusion of the transcripts of the four trials, and that weightiness took away from her own incredible narrative of the struggle between the haves and have nots. Finally, at the urging of other writers in our class, she took out the heavy versions of the trials. Then her perspective on the death of her son came through with more force. She said, “Williams was a fifty year old self-made millionaire with long standing involvement in the community, both socially and as an active member of the restoration goals of Savannah. Nevertheless, I knew this man was the person who killed my son. Danny didn’t have the wealth or power needed to be a part of Savannah’s society. He had nothing.”

Emily’s manner of expression is not simple; it is frank yet complex in its straightforwardness. It is voice for which all writers strive: voice driven by passion. Effective narrative voice must come from the heart, from a direct desire to impart something not only true but consequential. Emily’s story naturally had to involve the murder of her son, summaries of the trials, the eventual death of Williams, and the hype that overtook Savannah due to the Berendt’s book and Eastwood’s movie. Yet, Emily’s story is far more than that. That truth came to me early on as I began reading her drafts and found myself drawn into the grip of her early poverty. The voice made me feel anger and bitterness toward society and any family that doesn’t stand up for its children. But then that same voice forced me to realize that I cannot hold on to such feelings if I plan to leave this life unfettered. Her voice allowed me to be transported to become the woman who once packed a gun to even the score but then replaced it with the pen and written word.

During the time Emily was in my class I gained a deep sense of what it might be like to raise a child and then lose him in such a bizarre manner. The loss of a child is not a statistic or a newspaper headline; it’s a life-shaking trauma that demands support from any direction.

Emily had support from her other three children, employers, and some friends, but not from the legal system or society in general. The media focused on Williams and his dilemma. That fact has become ingrained in the mountain of lore of this country, as it was infamously publicized in print and fictionalized on the big screen. There was hardly mention of an Emily Bannister in the Berendt’s book, and in the movie there was no haunting camera shot of the dead boy’s mother sitting in the dim corridors of that courthouse. Only from the grip of Emily’s voice could a reader experience the depth of such loss and the emptiness that engulfed it. Yet, her story is far more than that tragedy; it includes the beauty and humor of life amid adversity.

When Emily depicted Danny he became real and not the invented Billy the hustler on Bull Street as depicted in the movie. She wrote about his first steps and how he was noticeably pigeon toed. Danny was of medium height and weight, and was muscular, with ash blond hair that wanted to curl when it became too long or damp, thick eyebrows and long dark eyelashes that emphasized big blue eyes. His lips tilted upward at the right corner when he smiled. Yes, I could see the resemblance to Judd Law, who play the role in the movie. Emily told about how as a small child, Danny was attracted to all forms of beauty, and cared little for anything competitive, choosing instead crayons, puzzles, and toys that produced music. He spent countless hours picking flowers in their spacious yard that must’ve appeared boundless to a small boy. He particularly liked the yellow jonquil and tiny white snowdrops, calling them bellflowers because of their shapes. She thought that Danny’s love for cultural beauty is probably one thing that drew him to Williams.

Emily’s story marches through cold reality of the murder and its aftermath, to entanglements with the legal systems and the burial, and then it backs up to weave in the narrative of her family and the old father who questioned her birthright and existence, her mother Snooky, the moves from house to house, Emily’s teenage marriage and babies, and the determination to gain an education despite poverty. It is in that texture that the reader is so thoroughly taken into another time and place and a life of which most people never catch more than a glimpse. The narrative takes on the level of a case study in Southern poverty, and then it rises to the escapades of an independent single mother and the challenges of raising children alone. Inevitably the story journeys back to the trials and the eventual acquittal and the death of Williams. After he final chapter, Emily added a “Finale.” It is entitled “Illegitimi non carborundum. (Don’t Let the Bastards Get You Down!)”

Why is it that some writers are able to capture authenticity through mundane details and how did Emily acquire that skill, or is it a talent that just comes naturally to some? My thought is that such talent is the gift rising out of a special sensitivity to how life is pieced together. Though she certainly spent ample time studying and learning the craft of writing, she, without a doubt, had something else going in her mind, something that allowed her to see and feel events and to capture them in scenes, always in the strong irony-filled narrative voice. She wrote of her father’s catastrophe in WWI and his subsequent misadventures in civilian life as if she were a historian piecing together the facts of times past.

Emily’s mundane details reveal the cobwebs in which she had grown up. She wrote that her father spent the rest of his life in and out of hospitals because of war injuries. Later, she learned that he had been married numerous times. She said, “I don’t think he even knew how many times until a Superior Court judge presented him with an itemized list, along with a summons to court sometime in the early seventies.” A list of no less than three women was read to her father and as to the whereabouts of these women, and her father replied that he’d “misplaced” them. He didn’t know where any of them were or whether they were still living. He said he’d never gotten a divorce from any of them. When he decided to leave them he just left. With her father in his seventies, and the length of time involved, the judge had little alternative but to perform a “mass divorce,” releasing him from the bonds of matrimony and rendering him a single man. Emily’s mother quickly realized that after thirty odd years of marriage, this also included her!

Emily continued to study creative writing in my classes for several years. In that time she made friends with other writers and she moved her story forward. My students respected her for her writing skills and for her story. Her honesty and humility was always peppered with a sharp-tongued edge of wit about society and the haves and have nots. She made us laugh at life.

My feelings toward Emily included affection and a bit of fear of ever crossing her. I was respectful to her as student, but I was aware that she might have inadvertently placed me in the haves box. On the other hand, she treated me with high regard as I mentored her through revisions of the manuscript. I coached her in steps for getting her story published, but she bulked when I told her she absolutely had to write a synopsis as part of the proposal package so that an agent could see the story in short form. She hissed out the “ssss” in synopsis, saying it brought up her deepest fear: that she could not write that story again. I knew that she meant she could not live the experience again. I understood that.

In the time I knew her she was living comfortably. She cherished the memory of her past experiences, but, she wanted to move further from the darkness, on into the light. I knew that and understood that in the deepest part of my heart. She was ill. She knew that at some point she would be free of life. She confided in me that she had “a diagnosis,” but she did not put a time frame to it. It was something that I could not fully comprehend, but it had the feeling of something arcane.

Through Emily’s story I knew I was experiencing one of the finest examples of litmus test creative nonfiction. The manuscript was finally in somewhat publishable form, but regardless all my honed teaching skills I could not force her steps to publishing. It was only up to her and now to her family. She often told me that all she wanted was for W.W. Norton to publish it and to give her two complimentary copies. I explained that she would need to jump through the hoops of the publishing world and that W.W. Norton might not provide any hoops. One of my students, a radio personality, told Emily that she would need to sharpen her skills as an interviewee for television and radio as part of the marketing plan for a book. Emily became incredibly livid at the idea that anything would be demanded of her. She felt that she had lived the story and wasn’t that enough? I knew she wasn’t being practical, but I also knew she was ill. Toward the end she would disappear from class occasionally and then reappear. One day as I was leaving my classroom, I found her in the hallway standing quietly and shyly alone, as thin as a rail. She told me she’d been hospitalized in relation to the illness and that she was now ready to come back to class, and she did for short while.

The compelling power of Emily’s story was a result how that writer had come to be. I could not toy with that. Emily was going to run her course and I could do nothing more than be her teacher, mentor, and try to be a friend as she would allow. She was going to disappear again and I just had to wait until she would reappear. Finally she did.

Emily came back to me with force. She’d slipped away to Savannah and died in November 2005; nevertheless, once I was able to visit the grave I could feel her spirit again. And, there is the manuscript: its words continue to come back to me with vigor. Though it may never see print, Emily’s story is not over. It still has time to penetrate those of us who knew her and anyone with whom we share her story. And, she lies peacefully yet still determined, in a grave beside her son, in a site that suites her well.

Source by Sarah Anne Shope, PhD

#seolinksdiv h3{ color:#000000; } #seolinksdiv ul li a{ color:#000000; }

More Marijuana info :

Marijuana

T.Y.S Lighting Edison Colorful Pendant Light Fixture E27/E26 Silicone Ceiling Light Holder (Red)

Sun Blaze 960345 T5 High Output Supreme Fluorescent Strip Light, 4-Feet, 1 Lamp

from 420 Growing News http://www.growing420.net/2017/07/08/a-savannah-site-for-emily/

0 notes

Text

A Savannah Site for Emily

She isn’t in the Bonaventure or anywhere nearby the grave of Jim Williams. She wouldn’t have tolerated such positioning. Emily took a stand against the man years ago and wrote it down word for word with a working title of Cannabis and Snowdrops, mainly because her son Danny loved both. Her story is not a sequel to Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, though it tells of the aftermath; nor is it a prequel, though it tells of what happened in the years leading up to that fatal midnight. Rather, it is a kind of circling-and-spiraling, which I think of as Around Midnight. And, her story will likely never see the light of day.

In my most recent visit to her grave, the memories of having her as my student over three years poured out. One thing a creative writing teacher must never do is speak of his or her students’ stories in public, unless of course those writers have made their works public. For me that discretion ranks among the rules of priests, therapists and lawyers. And I would hesitate to speak now except for Emily’s prodding. She is as determined as she sleeps in Greenwich Cemetery as she was wide-eyed in my class.

“It’s fiction,” she had taunted from the back of the room that first day she was in my class and whenever I held up Berent’s book or mentioned the title. The thin sassy voice came with rich Savannah accent, from a pugnacious figure then totally unknown to me, one which I was not about to take on in front of my class of urbane aspiring writers.

“Fiction!” came again as loud as a whisper allows. After several more taunts from her it occurred to me that no matter who she is she might have something to add to my lecture on creative nonfiction or on the works that seem to be settling as the benchmarks of the sometimes wooly genre. Little did I know that over time she would modify my teaching of the topic of creative nonfiction, transform my perspective on issues of notoriety and on loss, and teach me much about voice driven writing styles.

Her writing was well underway when she entered my classes. Not a reaction to Berendt’s book, hers is the story of growing up as a “have not” in a world of powerful “haves” in the thick moss and mist of Savannah. Hers is the battle of growing up in the shadow of father old enough to be her grandfather and who gave her off in marriage at a young age, of raising four children virtually alone, of a dogged resistance to growing up ignorant just because you are poor, and of having a son shot to death in the home of millionaire on Bull Street. Emily’s story, written or unwritten, currently sits in the shadow of Midnight, just as she often had sat in dim corridors of the Savannah courthouse because she was not permitted in the court room while the trials went on. Nevertheless, to those who know it her story stands out in factuality and mesmerizing style.

Emily had written much of her story while she was in Savannah, long before she appeared in my class in 2002. The narrative had poured out of her in a compelling voice that few writers find the freedom to release. She wrote about and told us about her unfortunate experiences with people associated with writing and film making. In fact, some such episodes were in her manuscript. I suggested she be careful to not put herself in the position of describing situations that she might not be able to back up in the event someone decided to sue. My statement felt flimsy as it came out of my mouth, directed at a woman who’d lived through infamous trials of conviction and reversal of conviction of the Jim Williams. Williams had money, she pointed out to me, but she barely had “a pot to pee in.” Who could possibly sue her, and what would they get? But, she did take most of those questionable episodes out of her writing.

At first, Emily’s story was bogged down with the inclusion of the transcripts of the four trials, and that weightiness took away from her own incredible narrative of the struggle between the haves and have nots. Finally, at the urging of other writers in our class, she took out the heavy versions of the trials. Then her perspective on the death of her son came through with more force. She said, “Williams was a fifty year old self-made millionaire with long standing involvement in the community, both socially and as an active member of the restoration goals of Savannah. Nevertheless, I knew this man was the person who killed my son. Danny didn’t have the wealth or power needed to be a part of Savannah’s society. He had nothing.”

Emily’s manner of expression is not simple; it is frank yet complex in its straightforwardness. It is voice for which all writers strive: voice driven by passion. Effective narrative voice must come from the heart, from a direct desire to impart something not only true but consequential. Emily’s story naturally had to involve the murder of her son, summaries of the trials, the eventual death of Williams, and the hype that overtook Savannah due to the Berendt’s book and Eastwood’s movie. Yet, Emily’s story is far more than that. That truth came to me early on as I began reading her drafts and found myself drawn into the grip of her early poverty. The voice made me feel anger and bitterness toward society and any family that doesn’t stand up for its children. But then that same voice forced me to realize that I cannot hold on to such feelings if I plan to leave this life unfettered. Her voice allowed me to be transported to become the woman who once packed a gun to even the score but then replaced it with the pen and written word.

During the time Emily was in my class I gained a deep sense of what it might be like to raise a child and then lose him in such a bizarre manner. The loss of a child is not a statistic or a newspaper headline; it’s a life-shaking trauma that demands support from any direction.

Emily had support from her other three children, employers, and some friends, but not from the legal system or society in general. The media focused on Williams and his dilemma. That fact has become ingrained in the mountain of lore of this country, as it was infamously publicized in print and fictionalized on the big screen. There was hardly mention of an Emily Bannister in the Berendt’s book, and in the movie there was no haunting camera shot of the dead boy’s mother sitting in the dim corridors of that courthouse. Only from the grip of Emily’s voice could a reader experience the depth of such loss and the emptiness that engulfed it. Yet, her story is far more than that tragedy; it includes the beauty and humor of life amid adversity.

When Emily depicted Danny he became real and not the invented Billy the hustler on Bull Street as depicted in the movie. She wrote about his first steps and how he was noticeably pigeon toed. Danny was of medium height and weight, and was muscular, with ash blond hair that wanted to curl when it became too long or damp, thick eyebrows and long dark eyelashes that emphasized big blue eyes. His lips tilted upward at the right corner when he smiled. Yes, I could see the resemblance to Judd Law, who play the role in the movie. Emily told about how as a small child, Danny was attracted to all forms of beauty, and cared little for anything competitive, choosing instead crayons, puzzles, and toys that produced music. He spent countless hours picking flowers in their spacious yard that must’ve appeared boundless to a small boy. He particularly liked the yellow jonquil and tiny white snowdrops, calling them bellflowers because of their shapes. She thought that Danny’s love for cultural beauty is probably one thing that drew him to Williams.

Emily’s story marches through cold reality of the murder and its aftermath, to entanglements with the legal systems and the burial, and then it backs up to weave in the narrative of her family and the old father who questioned her birthright and existence, her mother Snooky, the moves from house to house, Emily’s teenage marriage and babies, and the determination to gain an education despite poverty. It is in that texture that the reader is so thoroughly taken into another time and place and a life of which most people never catch more than a glimpse. The narrative takes on the level of a case study in Southern poverty, and then it rises to the escapades of an independent single mother and the challenges of raising children alone. Inevitably the story journeys back to the trials and the eventual acquittal and the death of Williams. After he final chapter, Emily added a “Finale.” It is entitled “Illegitimi non carborundum. (Don’t Let the Bastards Get You Down!)”

Why is it that some writers are able to capture authenticity through mundane details and how did Emily acquire that skill, or is it a talent that just comes naturally to some? My thought is that such talent is the gift rising out of a special sensitivity to how life is pieced together. Though she certainly spent ample time studying and learning the craft of writing, she, without a doubt, had something else going in her mind, something that allowed her to see and feel events and to capture them in scenes, always in the strong irony-filled narrative voice. She wrote of her father’s catastrophe in WWI and his subsequent misadventures in civilian life as if she were a historian piecing together the facts of times past.

Emily’s mundane details reveal the cobwebs in which she had grown up. She wrote that her father spent the rest of his life in and out of hospitals because of war injuries. Later, she learned that he had been married numerous times. She said, “I don’t think he even knew how many times until a Superior Court judge presented him with an itemized list, along with a summons to court sometime in the early seventies.” A list of no less than three women was read to her father and as to the whereabouts of these women, and her father replied that he’d “misplaced” them. He didn’t know where any of them were or whether they were still living. He said he’d never gotten a divorce from any of them. When he decided to leave them he just left. With her father in his seventies, and the length of time involved, the judge had little alternative but to perform a “mass divorce,” releasing him from the bonds of matrimony and rendering him a single man. Emily’s mother quickly realized that after thirty odd years of marriage, this also included her!

Emily continued to study creative writing in my classes for several years. In that time she made friends with other writers and she moved her story forward. My students respected her for her writing skills and for her story. Her honesty and humility was always peppered with a sharp-tongued edge of wit about society and the haves and have nots. She made us laugh at life.

My feelings toward Emily included affection and a bit of fear of ever crossing her. I was respectful to her as student, but I was aware that she might have inadvertently placed me in the haves box. On the other hand, she treated me with high regard as I mentored her through revisions of the manuscript. I coached her in steps for getting her story published, but she bulked when I told her she absolutely had to write a synopsis as part of the proposal package so that an agent could see the story in short form. She hissed out the “ssss” in synopsis, saying it brought up her deepest fear: that she could not write that story again. I knew that she meant she could not live the experience again. I understood that.

In the time I knew her she was living comfortably. She cherished the memory of her past experiences, but, she wanted to move further from the darkness, on into the light. I knew that and understood that in the deepest part of my heart. She was ill. She knew that at some point she would be free of life. She confided in me that she had “a diagnosis,” but she did not put a time frame to it. It was something that I could not fully comprehend, but it had the feeling of something arcane.

Through Emily’s story I knew I was experiencing one of the finest examples of litmus test creative nonfiction. The manuscript was finally in somewhat publishable form, but regardless all my honed teaching skills I could not force her steps to publishing. It was only up to her and now to her family. She often told me that all she wanted was for W.W. Norton to publish it and to give her two complimentary copies. I explained that she would need to jump through the hoops of the publishing world and that W.W. Norton might not provide any hoops. One of my students, a radio personality, told Emily that she would need to sharpen her skills as an interviewee for television and radio as part of the marketing plan for a book. Emily became incredibly livid at the idea that anything would be demanded of her. She felt that she had lived the story and wasn’t that enough? I knew she wasn’t being practical, but I also knew she was ill. Toward the end she would disappear from class occasionally and then reappear. One day as I was leaving my classroom, I found her in the hallway standing quietly and shyly alone, as thin as a rail. She told me she’d been hospitalized in relation to the illness and that she was now ready to come back to class, and she did for short while.

The compelling power of Emily’s story was a result how that writer had come to be. I could not toy with that. Emily was going to run her course and I could do nothing more than be her teacher, mentor, and try to be a friend as she would allow. She was going to disappear again and I just had to wait until she would reappear. Finally she did.

Emily came back to me with force. She’d slipped away to Savannah and died in November 2005; nevertheless, once I was able to visit the grave I could feel her spirit again. And, there is the manuscript: its words continue to come back to me with vigor. Though it may never see print, Emily’s story is not over. It still has time to penetrate those of us who knew her and anyone with whom we share her story. And, she lies peacefully yet still determined, in a grave beside her son, in a site that suites her well.

Source by Sarah Anne Shope, PhD

#seolinksdiv h3{ color:#000000; } #seolinksdiv ul li a{ color:#000000; }

More Marijuana info :

Marijuana

T.Y.S Lighting Edison Colorful Pendant Light Fixture E27/E26 Silicone Ceiling Light Holder (Red)

Sun Blaze 960345 T5 High Output Supreme Fluorescent Strip Light, 4-Feet, 1 Lamp

from 420 Growing News http://www.growing420.net/2017/07/08/a-savannah-site-for-emily/

0 notes