#he's (again) A CONFEDERATE CAVALRY OFFICER

Text

jasper moodboards are the funniest fucking thing on twilight tumblr i'm sorry

#...is it petty if i make this post?#too late i'm doing it anyway#oh my god#it's SO RIDICULOUS TO ME#i saw this one moodboard. the middle quote was a quote abt how hard it is to be an empath#and still take care of yourself#HE'S A CONFEDERATE SOLDIER LMAOOO#also even in canon he's not. like. particularly empathetic#he's just manipulative! he gets his power from being manipulative & 'charismatic'!#if anything the empathy is a curse that he EARNED#& is doing his best to ignore#like. he canonically wishes he wasn't an empath bc it makes it harder for him to EAT PEOPLE#so the pinterest mental health inspo quote really killed me#also there were a bunch of grainy aesthetic cowboy photos and like.#the cowboy aesthetic is. first of all. very funny to me#AND he's not a cowboy#he's (again) A CONFEDERATE CAVALRY OFFICER#THERE'S NO CANON EVIDENCE HE WAS EVER A FUCKING COWBOY#also. come talk to me about the actual fucking history of cowboying in texas#and get your fucking aesthetic photos out of here#did you know that most texas ranches pre-war (62%!) enslaved their cowhands?#ONCE AGAIN. HE'S A CONFEDERATEEEEEEEEE#(& the time when he was human would've been. not really the time for him to even feasibly be a cowboy? spanish fever & cattle quarantine <3#so. anyways.#fanon jasper remains the funniest thing ever to me

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Battle of Gettysburg - Day 3

July 3

1:30 PM

The Largest Artillery Bombardment in the American Continent

All around them shot tore through the ground and shells exploded, sending shrapel flying. But the General did not flinch and instead calmly made their way through the line, encouraging the troops and ordering the artillery to return fire against the enemy guns.

Early on July 3, General Robert E. Lee, commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, wanted to renew the attacks on the Union left and right flanks. The fighting during the previous day was close and Confederate forces were on the verge of victory. One more push on those flanks might make the Union line crack.

However, earlry in the morning, the Union XII Corps, at the Union right flank, bombarded Confederate positions near their front. Then, in an intense attack, they managed to drive back the brigades of Confederate Second Corps from the hard fought bridgehead they captured. This prevented Lee from exploiting any gains they had made yesterday.

Because of this early setback on the Union right, and because of the bad terrain at the Union left, Lee decided to aim for a different portion of the enemy's line.

Eventually, Lee had decided to strike the Union center at Cemetery Ridge. There was no other choice and he believed that it was the most vulnerable part of the Union line. Yesterday's fighting had concentrated on the Union's left and right flank. Although Confederate forces were unsuccessful at dislodging their enemy, they did managed to force the Union to divert crucial reserves to those vulnerable areas. This mean that the center was deprived of such reserves.

Studying the Union positions at Cemetery Ridge, Lee must have remembered an incident he saw the previous day. As his First Corps was attacking the Union positions on the left flank, a stray brigade from his Third Corps, which was attempting to distract Union forces away from the fighting on the left, managed to advance towards the crest of the ridge and temporarily capture some Union guns, before being forced to withdraw due to lack of support. If one brigade could reach that ridge without problems, then surely a corps sized attack could do the same?

With that in mind, he planned out his assault. In overall command of the attack would by First Corps commander, and trusted officer, Lieutenant General James Longstreet. Under his command would be Pickett's Division, which was a part of First Corps, but had arrived late at Gettysburg and was thus still fresh. Also to be under Longstreet's command were brigades from Heth's Division, temporarily under the command of Brigadier General Pettigrew, and two briages under Major General Trimble. from Pender's Division. All in all, the assaulting force would number around 10,500 troops.

However, Longstreet was not happy with the plan. In fact, he was no happy at the very idea of assaulting the enemy center.

Since the first day of the battle, Longstreet opposed the idea of the Confederates attacking the enemy. He wanted it to be the other way around. He had initially suggested that the army should retire to a position where it would be the Union attacking them. But Lee could not a agree to that. At the time, the Confederate cavalry was still missing and so a retreat before the enemy would be dangerous without the cavalry to cover them. When the cavalry did return, it was far too late to withdraw, as they were alraedy heavily engaged. Because of that, Lee continued to be on the offensive, while Longstreet, ever the good soldier, obeyed orders, despite his protests.

Now, Longstreet protested again. He pointed out that there was a mile long piece of open ground that separated the Confederate line and the Union center at Cemetery Ridge. He feared that any attacking force marching across that field would be vulnerable from Union artillery fire not only from Cemetery Ridge, but also from Union positions elsewheere, such as Little Round Top, where Union rifled canons could bombard them. They would endure heavy casualties crossing that field and the troops that do make it would then have to fight against prepared Union positions on the high ground and behind a stone wall. It would be disasterous.

In his own words, Longstreet told Lee: "General Lee, I have been a soldier all my life. I have been with soldiers engaged in fights by couples, by squads, companies, regiments, divisions, and armies, and should know as well as anyone what soldiers can do. It is my opinion that no fifteen thousand men ever arrayed for battle can take that position.” (Longstreet mentions 15,000, because at the time he said that the units designated for the attack had not been chosen yet. Under the belief that it would be a 3 Division attack, and not 2 Divisions as it would be, he thus said 15,000)

Desspite Longstreet's insistance, Lee went though with the plan. Longstreet had always been a worrier and Lee understood his officer's concerns. But Lee aws sure that a strike on the Union's weak center would break the enemy. Thus, he made the same mistake as Napoleon at Waterloo.

In order to support the innfantry assault, Lee and Longstreet planned a massive artillery bombardment to take out both the Union infantry and guns on Cemetery Ridge. The task of positioning the guns and executing the bombardment was placed on Lieutenant Colonel Edward Alexander, the First Corps Artillery Chief. At his disposal would be between 143 to 163 artillery pieces, of various types and sizes, from smoothhbores and even a couple of rifled guns.

Once the artillery was in postition, and once the infantry was deployed behind them, laying down in order to conceal their presence to enemy observers, the order was given to begin the bombardment.

All batteries were told that two cannon shots would mark the start of the bombardment. One gun fired, attracting the attention of Union troops resting on Cemetery Ridge, while also alerting the Confederate artillery troops to get read. The second canon was ordered to fire, but nothing happened. It was a misfire. Quickly, a third gun was orderd to fire and once it erupted, all hell broke loose.

One by one, Confederate artillery batteries came to life, firing shot and shell against one target, the Union center at Cemetery Ridge. Soon the gunners got into tempo, as they worked their pieces and fired. Eventually, the smoke of gunpoweder filled the air. The artillery fire was so intense that one gunner said that the earth shook from the constant fire.

Meanwhile, on the Union line, troops that had initially been resting quickly moved back towards their positions. Most of the regiments on Cemetery Ridge were placed behind a low stone wall. Although it wasn't high enough to cover someone who stood, it did provide good cover for those who laid down. Because of that the troops bunched up behind the wall, doing their best to protect themselvse from the on coming bombardment. All around them, shot landed and shells exploded, but those who remained behind the wall were spared from the worse effects of the artillery fire.

As shot and shell landed all over Cemetery Ridge, one commander stood tall and rode along the line in hopes of keeping his troops morale in check.

Major General Winfield Hancock, commander of the Union II Corps that defended the center, moved around, his corps-flag right behind him. He presented a tall target during the bombardment, but he continued to encourage his troops under the bombardment.

At one point an aide approached Hancock, begging him to get down and take cover. In reponse, Hancock said: "There are times when a corps commander’s life does not count."

However, it wasn't only Hancock that was calm and cool during that moment. Brigadier General John Gibbon, commander of II Corps' 2nd Division, was calmly walking along the line, while an unnamed soldier, who was bringing canteens to the front, was calmly walking up to the line and, after some shrapnel struck the strap of his knapsack, merely gave a beif puzzled look as to what happened, before calmly continuing on his way.

However, if the position at Cemetery Ridge was somewhat tolerable, the positions at the rear, east of the ridge, was pure chaos. Many Confederate shells overshot and fell on the rear lines, hitting the headquarters of the Army of the Potomac and the rear troops. Some shells even struck Culp's Hill. The bombardment at the rear turned out to be worse than the one the front was recieving. It got so bad that General Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac, had to vacate the house he was using as his headquarters, while the infantry and artillery reserve had to pull back and away from Cemetery Ridge.

In reponse to the Confederate artillery fire, around 30 Union guns, from Cemetery Hill and the distant Little Round Top, opened fire. However, around 60 guns from Cemetery Ridge remained silent. Brigadier General Henry Hunt, Chief of Artillery of the Army of the Potomac, had ordered the guns at Cemetery Ridge to hold fire. Hunt did not want to get involve in an artillery duel and instead wanted to save ammunition to counter an infantry assault he felt was coming.

However, as Confederate artillery fire intensified, and as some shells blew up the artillery chest of Union batteries, Hancock decided to countermand Hunt's orders and ordered his corps artillery to open fire. He believed that the guns were being wasted if they remained silent. He also thought that it would help encourage the Union troops, who were wondering why their own artillery were remainig silent. Soon the guns on Cemetery Ridge began to conduct counter-battery fire. Their shot and shells soon struck the Confederate batteries, taking out a few guns.

The Union artillery fire was concerning for Alexander, as it meant that he was failing in eliminating the guns. With his own ammunition supply running low, and with Union guns still active, this could mean that the infantry assault may have to be cancelled.

However, after a while, the Union fire from Cemetery Ridge began to slacken and eventually cease. At that moment, Confederate commanders believed that he Union guns were finally eliminated and that the assault should now begin. Because of that, preparations were being made to launch the attack.

Little did the Confederates know, the Union guns were still active. Hunt, realizing that Meade wanted to encourage the enemy to attack, ordered the Union batteries on Cemetery Ridge to cease fire. That way, the enemy would think that the guns were out and, once they have fully committed to their attack, the guns would once again open fire and bobmard the enemy's attacking force.

Hunt had just lured the Confederates into a trap.

----------------------------------------

Featuring @hoofclid @nox-lunarwing and @ama-artistic as members of the Union III Corps. Hoofclid has a white clover corps patch, with a smaller brighter white clover in it, indicating he is a part of the 2nd Division of the II Corps. Nox is portraying General Winfield Hancock, commander of II Corps. Meanwhile, Cyprus is holding the II Corps Headquarters flag.

#hoofclid#nox-lunarwing#ama-artistic#MLP#My Little Pony#Unicorn#Dragon#Earth Pony#History#Gettysburg#Battle of Gettysburg#Gettysburg 160#Gettysburg 160th Anniversary

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

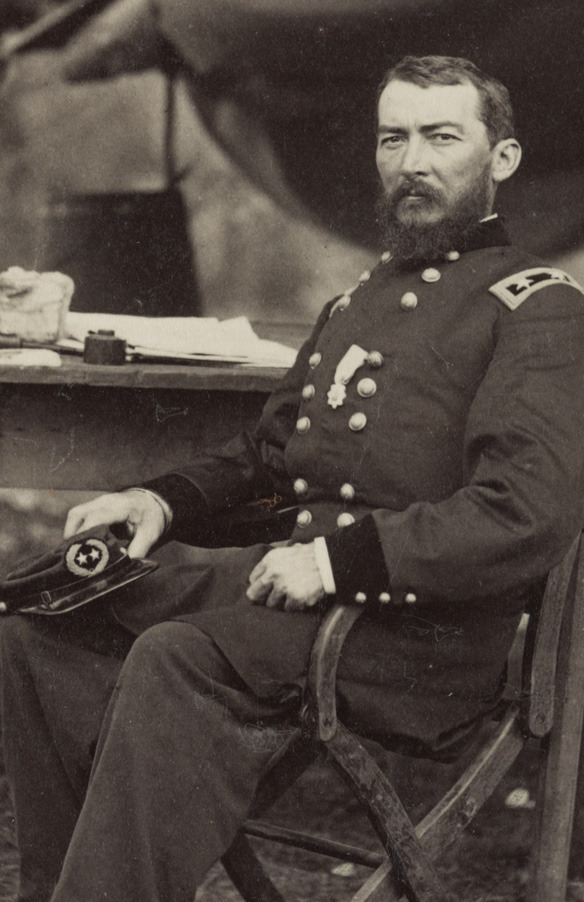

Philip Henry Sheridan, born March 6th, 1831, was once described by Abraham Lincoln as “A brown, chunky little chap, with a long body, short legs, not enough neck to hang him, and such long arms that if his ankles itch he can scratch them without stooping.” Still, “Little Phil” rose to tremendous power and fame before his untimely death of a heart attack at age 57.

He is most famous for his destruction of the Shenandoah Valley in 1864, called “The Burning” by its residents. He was also the subject of an extremely popular poem entitled “Sheridan’s Ride”, in which he (and his famous horse, Rienzi) save the day by arriving just in time for the Battle of Cedar Creek.

Like Patrick Cleburne, Sheridan rose very quickly in rank. In the fall of 1861, Sheridan was a staff officer for Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck. He later became quartermaster general in the Army of Southwest Missouri. With the help of influential friends he was appointed Colonel of the 2nd Michigan Cavalry in May, 1862. His first battle, Booneville, MS, impressed Brig. Gen. William S. Rosecrans so much that he himself was promoted to Brigadier General. After Stones River he was promoted to Major General.

Sheridan’s men were part of the forces which captured Missionary Ridge (near Chattanooga) in 1863. When Ulysses S. Grant was promoted to General-in-Chief of the Union armies, he made Sheridan the commander of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps. This moved him from the Western Theater to the Eastern Theater of operations. At first, Sheridan’s Corps was used for reconnaissance. His men were sent on a strategic raiding mission toward Richmond in May 1864. Then he fought with mixed success in Grant’s 1864 Overland Campaign.

During the Civil War, Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley was a vital resource to the Confederacy. Not only did it serve as the Confederate “breadbasket”, it was an important transportation route. The region had witnessed two large-scale campaigns already when Gen. Ulysses S. Grant decided to visit the Valley once again in 1864. He sent Philip Sheridan on a mission to make the Shenandoah Valley a “barren waste”.

In September, Sheridan defeated Jubal Early’s smaller force at Third Winchester, and again at Fisher’s Hill. Then he began “The Burning” – destroying barns, mills, railroads, factories – destroying resources for which the Confederacy had a dire need. He made over 400 square miles of the Valley uninhabitable. The Burning” foreshadowed William Tecumseh Sherman’s “March to the Sea”: another campaign to deny resources to the Confederacy as well as bring the war home to its civilians.

In October, however, Jubal Early caught Sheridan off guard. Early launched a surprise attack at Cedar Creek on the 19th. Sheridan, however, was ten miles away in Winchester, Virginia. Upon hearing the sound of artillery fire, Sheridan raced to rejoin his forces. He arrived just in time to rally his troops. Early’s men, however, were suffering from hunger and began to loot the abandoned Union camps. The actions of Sheridan (and Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright) stopped the Union retreat and dealt a severe blow to Early’s army.

For his actions at Cedar Creek, Sheridan was promoted to Major General in the regular army. He also received a letter of gratitude from President Abraham Lincoln. The general took great pleasure in Thomas Buchanan Read’s poem, “Sheridan’s Ride” – so much so that he renamed his horse “Winchester”. The Union victories in the Shenandoah Valley came just in time for Abraham Lincoln and helped the Republicans defeat Democratic candidate George B. McClellan in the election of 1864.

During the spring of 1865, Sheridan pursued Lee’s army with dogged determination. He trapped Early’s army in March. In April, Gen. Lee was forced to evacuate Petersburg when Sheridan cut off his lines of support at Five Forks. And, at Sayler’s Creek, he captured almost one quarter of Lee’s army. Finally at Appomattox, Lee was forced to surrender the Army of Northern Virginia when Sheridan’s forces blocked Lee’s escape route.

At war’s end, Phil Sheridan was a hero to many Northerners. Gen. Grant held him in the highest esteem. Still, Sheridan was not without his faults. He had pushed Grant’s orders to the limit. He also removed Gettysburg hero Gouverneur Warren from command. It was later ruled that Warren’s removal was unwarranted and unjustified.

During Reconstruction, Sheridan was appointed to be the military governor of Texas and Louisiana (the Fifth Military District). Because of the severity of his administration there, President Andrew Johnson declared that Sheridan was a tyrant and had him removed. In 1867, Ulysses S. Grant charged Sheridan with pacifying the Great Plains, where warfare with Native Americans was wreaking havoc. In an effort to force the Plains people onto reservations, Sheridan used the same tactics he used in the Shenandoah Valley: he attacked several tribes in their winter quarters, and he promoted the widespread slaughter of American bison, their primary source of food.

In 1871, the general oversaw military relief efforts during the Great Chicago Fire. He became the Commanding General of the United States Army on November 1, 1883, and on June 1, 1888, he was promoted to General of the Army of the United States – the same rank achieved by Ulysses S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman.

Sheridan is also largely responsible for the establishment of Yellowstone National Park – saving it from being sold to developers.

On August 5th, 1888, Sheridan died after a series of massive heart attacks. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

#philip sheridan#philip h sheridan#american civil war#history#i discovered in my reading on thing with the civil war...that i like to read about loud assholes lol#and sheridan isssss for sure one of them#but hey...i can join him in the 'don't like gov. warren club'#that's a whole other topic#but i will also say! that sheridan has a lot of good photos#and i always forget that when he went east he had a beard for a bit lol

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Okay, it’s finally time for it: Zhujiu, baby, what is you wearing? Like we did for Mr. Sandman, let’s take this inside out.

His innermost visible layer is a long-sleeved brown t-shirt and brown pants, though they’re not the same brown. The shirt has sleeves that are long enough to be visible around his wrists even when he’s got his coat on, but loose enough that he can push them up over his elbows. The pants have pockets on the thighs that button shut.

Over this, he’s put on, for some damn reason, a double-breasted sleeveless purple tunic that closes asymmetrically over his right side, like an old-school Starfleet uniform. It’s hard to see, but the main fabric is actually a lighter purple that has darker purple plaid stripes over it, and then the edging is a fabric in that same darker purple color with the same lighter purple plaid. For a strange-ass garment, it’s actually constructed pretty well.

Over that he has a green cowl scarf and a belt. I think the cowl is separate from the tunic, since it makes more sense for it to be separate, but it’s not clear. The belt is studded and yet another shade of brown introduced into this mess.

And over all that, he’s got his weird beige duster with the darker brown shoulders and even darker brown trim. I’ve lost track of how many shades of brown we’re talking here. I refuse to do that much math for Zhujiu.

He’s wearing yet another kind of brown riding boots with zippers up the sides. ...Look, I love the boots, the boots are legitimately my favorite part of the outfit. But between them and the double-breasted tunic, he’s got a real Confederate Cavalry Officer look going on here, and it’s not not working for him? But at the same time, it’s a lot.

And as though that weren’t enough, he’s hit up the Dragon City Hot Topic with a vengeance and gotten a chunky silver ring for his left hand, and a cuff-and-ring combo that he only wishes turned into a sparky purple whip. (Then again, I suppose Jiang Cheng would trade it for the ability to suddenly excuse himself from any of the many situations that torment him.)

I wish his wig were better, because I love that we finally have a boy with the Rebellious Asian Colorful Hair Streak. But no, he plugged “emo beach waves” into Amazon and got the twenty-dollar-est wig he could find. That’s our Zhujiu!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nightmares;

"I am Captain Desmond Hayden, of the Fifth regiment of Vermont!"

The booming voice of a young man cuts through the cracks and pops, overflowing with zealousness and righteous anger. A wide eye'd young man steps from behind a stone house, he feels his body shake and quake as a rush of emotion overtakes him. Within his heart he feels fear, a shiver escapes his body as he stands wide legged Infront of barricaded confederate forces, he himself barely a man of nineteen. He earned his officer strips on the field of battles and with it a duty most befitting to a hotblooded young man leading men his age and older.

And that was to find, uproot, and raze all confederate troops and property. It was a campaign of total destruction, burning of infrastructure, and if they found resistance or battle to lick them hard and retreat. Today, he had the great fortune of finding a slave holding plantation within Georgia. Having been raised a firm abolitionist he held nothing but contempt for the southern rebels who not only betrayed their flag, but also practiced the morally corrupt and bankrupt institution that was systematic slavery.

"I come before you now demanding the COMPLETE and IMMEDIATE surrender and emancipation of all enslaved peoples!" His voice breaks as he shrieks these words, his feet tap against the ground slightly bucking forward as if ready to launch himselves at the entrenched men. With nothing but silence for his reply, he sucked in a deep breath as he thumbed back the hammer of his cavalry revolver. "Come on you heathens! If the good Lord wanted you to have slaves, he would've never made ME!"

He ends the sentence with a yell, to which his words are answered finally. A narrow miss of a bullet hitting next to him which caused the gunfight to erupt again. Hayden scurrying to the side as he pointed the revolver letting loose a charge towards the gunfire, while still spewing insults.

"Come die then! DIE LIKE THE DOGS YOU ARE! THE TIME OF ENSLAVEMENT ENDS HERE YOU GODLESS HEATHENS!"

...

Hayden's wakes with a startle, he sits up in a cold sweat. He brings to his eyes, staring at the shaking appendage. The memories, the nightmares, the dreams of a distant life.

Once long ago he was a soldier within a foreign army, fighting for the salvation of his nation. Fighting against something evil, that escapes his tongue. He remembers seeing men in bondage. He remembers the rage, the calling. He doesn't recall the men he killed. Only that they had to die.

He turns his head and stares out the window, and he sees the mountains.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

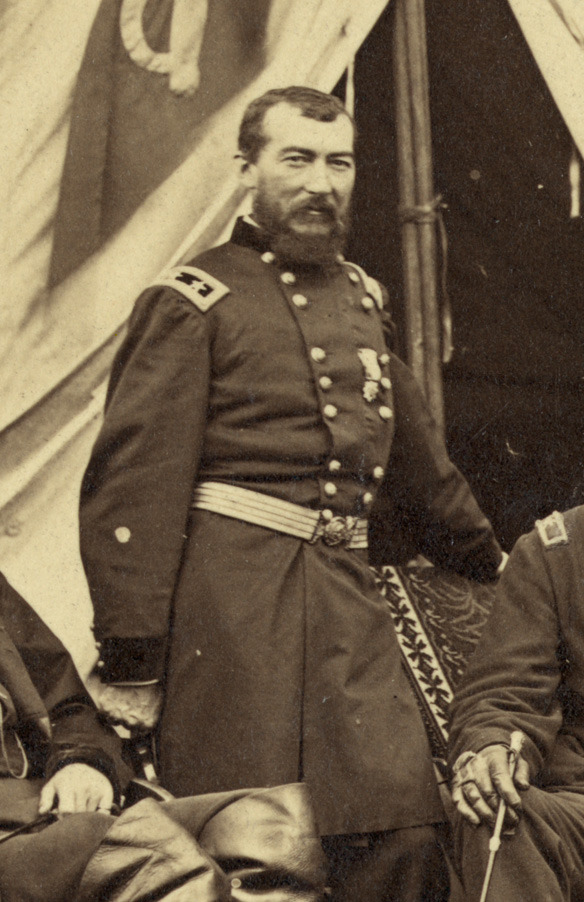

Map of the Battles of Bull Run, 7/21/1861

File Unit: Virginia and the Chesapeake Bay, 1784 - 1890

Series: Civil Works Map File, 1818 - 1947

Record Group 77: Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, 1789 - 1999

Image description: Map of the area of Bull Run, showing roads, terrain, troops, structures. There are many notes describing different areas.

Image description: Zoomed-in portion of the map showing the “Battle Field in the Afternoon” area.

Transcription:

MAP

OF

BATTLES

ON

BULL RUN

NEAR

MANASSAS,

on the line of Fairfax & Prince William Coes.

in VIRGINIA,

FOUGHT BETWEEN THE FORCES OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES

AND OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.

GENLS BEAUREGARD and JOHNSTON, COMMANDING the CONFEDERATE

and

GENL. McDOWELL, THE UNITED STATES FORCES

on the 21st of July 1861, from 7 A.M. - 9 P.M.

MADE FROM OBSERVATION

BY SOLOMON BAMBERGER.

Published by WEST & JOHNSTON, 145 Main Street

RICHMOND, Va.

SCALES

4 INCHES TO THE MILE

Two companies of cavalry of enemy here

as reserve during the day. In the afternoon cavalry

charged towards Geo. 7th and were repulsed with canister.

Enemy's Cavalry

WARRENTON TURNPIKE

SUDLEYS FORD

OLD STONE CHURCH METHOD. No guard at Sudley's in the morning and the country people would not give information to the southern army of the approach of the columne

SPRING This road was used by the enemy in the morning

KNIGHT'S The larger number returned by this road in the evening.

DOGAN'S JULY 21ST, 1861. MAJOR SCOTT 4th Alab. wounded in retreat

MAYHEWS STONE GENL. BEE & BARTOW'S command were in advance here in the morning

Lt. Davison 2d position

Van Pelt

Genl. Evans H.Q.

STONEBRIDGE

Enemy's battery opeed fire in the morning

When the retreating column reached this point and saw our cavalry onthe turnpike the panic seized the entire columne.

Here, wagons sotes, the siege gun or 30 pounder, arms, baggage and every thing was abandoned to facilitate their retreat.

This is the flat side of the creek and back to the road does not usually rise more than 15 or 20 feet above the creek bottoms. All enclosed is in cultivation. Opposite or west wide of the creek is bluff.

BULL RUNN

N.H. VT. R.I. N.Y. 69th Ice House CARTER POPLAR or RED HILL FORD

BOAT HOWITZER 4th ALA. COL. JONES BATTLE FIELD in the morning BARTON'S horse shot

N. YORK 7TH wounded GEO. 8th

N.O. Tigers

The enemy made a stand her about 4 P.M., on the retreat our batteries into their columne and here the rout began.

DUMFRIES (ON POTOMAC) ROAD

First colors planted over Sherman's battery were regiment colors of the 7th Georgia. captured battery

RICKET'S or SHERMAN'S captured here

captured battery Geo 7 Regt.

Jim. Robinson free Negro

Washington

N.O. Battery Capt. Inboden's battery

BATTLE FIELD IN THE AFTERNOON

Old woman killed in this house

BARTOW killed

Washington Artillery

Cummings Allen Preston Echols Harper Gl. Jackson's brigade

PENDLETON'S BATTERY came into action at 12 1/12 P.M. This Battery dismounted Rickett's called Sherman's battery and killed 45 horses. General Bee and Col. Bartow, after their retreat from the turnpike formed under Genl. Jackson's command.

When Genl. KIRBY SMITHS reinforcement (Elzy's brigade) came up about 3 1/12 P.M. Beauregard remarked, Elzy you are the Blucher of the day.

GEN. Bee killed Cumming' Regt. charged and took this battery when Col. Thomas of Mard was killed

Battery twice capture

caisson blew up

Enemy advanced thus far and retreated by Sudley's Ford

WARRENTON TURNPIKE AT ALEXANDRIA BY CENTREVILLE AND FAIRFAX COURTHOUSE

SUSPENSION BRIDGE

CUB RUN

The enemy opened fire below Mitchell's Ford in the morning to deceive our officers as to the crossing above at Sudley's Ford. In the afternoon, about 4 o'clock heavy firing was resumed here and was effectual in diverting our troops from the pursuit to this point.

HIGH HILLS

The largest group of the enemy was on the turnpike two miles east of Centreville. The prisoners state they left camp at one A.M. the morning of the 21st July 1861. They turned out at Widow Spindle's about 7 A.M. crossed at Sudley's Ford at 10 A.M., east dinner in the woods and were ready for fight at 12 M. July 21st 1861.

United States reserved forces

High point overlooking the battlefield July 21st 1861.

United States reserved forces

OLD FIELD OF THICK PINE UNDERGROWTH

LEWIS House

Where Capt. Ricketts and Wilcox were carried after being wounded.

Good skirmishing was done all day by many regiments and stragglers, but Genl. Jackson' brigade held their position during the fight; After they were assigned a place, Seibel's regiment marched 22 in the afternoon.

PENDLETON'S BATTERY

here at 12 M. marched 4 miles in 30 minutes

Our army was distributed along Bull Run on the 21st of July 1861 from the Stone Bride to Union Mllls. The entire plan of the Battle was changed by the enemy crossing at Sudley's Ford, and taking position about the Carter House.

WARE's HOUSE ROAD TO CENTREVILLE MITCHELL'S FORD

GEN. BEAUREGARD's Head Quart. after the Battle of July 21st.

McLANE'S

GENl. JOHNSTON'S Head Quarter

Major Harrison and Lieut. Miles killed in the battle July 18th, 1861

Washington Light Artillery in the bottom

BLACKFORDS FORD

Enemy's Battery

McLEAN'S FORD

July the 18th 1861

Many on the retreat after crossing Sudley's Ford did not turn down the run but went across towards the Potomac

ENEMY's Camp Timber felled around about 60 feet wide as abbatis, and the enhancements in front supposed to have been done under the flag of truce for burying their dead, July the 19th of 1861

This Battery kept up firing in the morning of the 21st to deceive Beauregard and Johnston. It fired again in the afternoon at 4 o'clock and cause troops to be sent here that should have been used the the Stone Bridge. It is said a Courier was killed who had orders for Gen. Ewell's Brigade on our right wing to flank the enemy. Ewell's Brigade marched across the run in the afternoon, but returned back on account of false alarm.

ROAD TO UNION MILLS

GENl. BEAUREGARD'S Head Qrs before the Battle

MANASSAS GAP R.R.

MANASSAS

UNION MILLS

FOUR MILE CREEK

ORANGE AND ALEXANDRIA R.R.

Miles reserve made a stand on these hills on the evening of the 21st. but as the routed army approached the wing broke and pushed on to Alexandria.

VERY HIGH HILLS

Spring

CENTREVILLE

The left wing of the enemy retreated from the Mitchells Farm at 6 P.M. July 21st and held this position in the line of battle until 11 1/2 P.M. when he retreated toward Alexandria

Copy from a lithograph Bureau of Topl. Engrs. October 1st, 1861

LITH. OF HUGER & LUDWIG, RICHMOND

59 notes

·

View notes

Photo

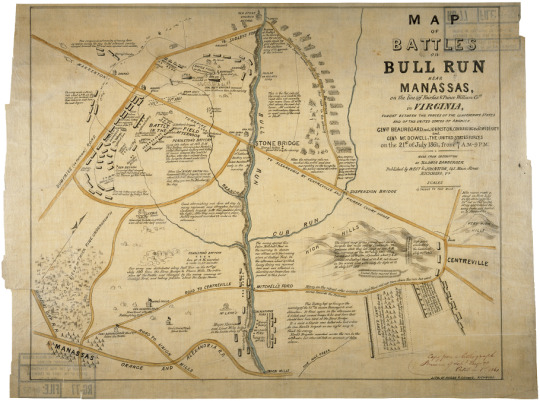

The second Battle of Inverlochy was fought on February 2nd 1645 - the first had been in 1431 when the MacDonald Lords of the Isles had been victorious over the armies of James I.

This was one of a series of stunning victories for the Royalist army led by James Graham, 5th Earl and 1st Marquis of Montrose, this battle saw him rout the Earl of Argyll's Covenating forces.

In August 1643 the Scottish Government and English Parliament signed the Solemn League and Covenant resulting in Scotland entering the war against King Charles I. In response the King appointed James Graham, Marquis of Montrose as Captain General of Royalist forces in Scotland. Although he had fought as a Covenanter commander during the Bishops War, he had opposed the subsequent power of the Presbyterian leadership under Archibald Campbell, Marquis of Argyll. Montrose effectively mobilised the Highland forces, many of whom were opposed to Campbell, and achieved a number of rapid successes including victory at the Battle of Tippermuir the previous September and an assault on Aberdeen in October.

The Covenanter forces consisted of men drawn from Campbell's territories within Argyll and also veteran troops drawn from the Scottish army fighting in England most of whom were lowlanders. The Royalists had a core of Highlanders but their numbers were being depleted as many returned home laden with the loot they had acquired from the raided Campbell territories. However Montrose also had a large contingent of Irish, headed by General Alasdair MacColla, who had joined with the Royalist force in November 1644.

At Glencoe the army crossed the high passes into Glen Nevis, moved around the north slopes of Ben Nevis, going round Inverlochy Castle, and then continued up the Great Glen, arriving at Kilcummin to re-supply. Montroses´ army was dwindling as his highlanders continued to head home leaving him with about 1500 men. He was aware that a Covenanter army under the command of the Earl of Seaforth was waiting to confront him at Inverness. Montrose was also aware that Argyll, with a force of 3000 men, was pursuing him and was only thirty miles behind at Inverlochy. What followed was one of the greatest flanking marches in British history across some of the toughest and wildest terrain in the British Isles. Instead of marching back down the glen, Montrose decided to surprise Argyll and marched south through the mountains around Ben Nevis to mount a surprise attack.

The Montrose army spent a cold night in the open on the side of Ben Nevis. Argyll was aware that a small force was operating in the area, he did not know however that it was the entire royal army. Just before dawn on 2 February 1645, Argyll and his covenanters were dismayed at the sight that lay before them, as far as they were aware Montrose should have been 30 miles north.

Argyll did not stay for the battle, but instead he left the command of his army to his general, Duncan Campbell of Auchinbreck, and retired to his galley anchored on Loch Linnhe. As seen in the pic. Auchinbreck lined up the covenanters in front of Inverlochy castle, which he reinforced with 200 musketeers to protect his left flank. In the centre he placed the Campbells of Argyll and put the lowland militias on the flanks. Unlike at Tippermuir and Aberdeen, where Montrose had defeated easily hastily conscripted and poorly trained militias, the troops he faced at Inverlochy were veterans of the war in England. Montrose lined his army up in only two lines deep to avoid being out flanked, placing his 600 highlanders in the centre with the Irish on the flanks, the right being commanded by MacColla.

The fight did not start straight away and instead skirmishes broke out along the line. This is probably because Auchinbreck and his officers thought that they were only fighting one of Montrose´s lieutenants and not the man himself, believing he was still far up the glen. Just before first light, the Royalists launched their attack.

The Irish clashed with the lowlanders on both flanks and routed them while the highlanders closed with the Campbells in the centre. The Campbells broke, but their retreat to the castle was blocked by the Royalist reserve cavalry under the command of Sir Thomas Ogilvie. Auchinbreck was shot in the thigh while trying to rally his men and died shortly afterwards.

The remaining Covenanters briefly rallied around their standard, then broke and ran, trying to reach Lochaber. The small garrison in Inverlochy castle surrendered without a fight. Over 1500 Covenanter troops died, while Montrose may have only lost 250 men, the most notable being Sir Thomas Ogilvie who was killed by a stray bullet.

Montrose, through his lieutenant, MacColla, who commanded the 2000 Irish troops sent by the Irish Confederate), was able to use this conflict to rally Clan Donald against Clan Campbell. In many respects, the Battle of Inverlochy can be seen as part of the clan war between these two.

Before the Battle of Inverlochy took place, the bard Iain Lom MacDonald of Keppoch left the main body of MacColla’s men and sat to get a good view of the battlefield. Tradition states that MacColla came up to him and asked, ‘Iain Lom wilt thou leave us?’ to which Iain Lom replied, “If I go with thee today and fall in battle, who will sing thy praises and prowess tomorrow?” Iain Lom MacDonald was a staunch Royalist and was feared by Clan Campbell because of his wit and poetic skill. When the Campbells placed a bounty on his head, Iain Lom appeared at Inveraray to personally collect the money for himself. The Campbells rewarded his audacity by entertaining him as their guest for a week. Iain Lom remained true to his word and wrote a poem about MacColla at Inverlochy that included the following stanzas-

Alasdair Mhic Cholla ghasda,

Làmh dheas a sgoltadh nan caisteal ;

Chuir thu ‘n ruaig air Ghallaibh glasa,

‘S ma dh’òl iad càil, gun chuir thu asd’ e.

‘M b’ aithne dhuibhse ‘n Goirtean Odhar?

‘S math a bha e air a thodhar,

Chan innear chaorach no ghobhar

Ach fuil Dhuibhneach an dèidh reothadh.

–

Alasdair, son of handsome Colla,

skilled hand at cleaving castles,

you put to flight the Lowland pale-face

what kale they had taken came out of them again.

Do you remember the place called the Tawny Field?

It got a fine dose of manure,

not the dung of sheeps or goats,

but Campbell blood well congealed.

The illustration is from 'Loyal Lochaber. Historical Genealogical and Traditionary' by W Drummond Norie, Glasgow, 1898

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Chatti

The Chatti were a Germanic tribe located in modern day Hesse and southern Saxony, Germany. They were one of the largest and most powerful tribes of Germania, only the Cherusci were as large as the Chatti tribe. I have written a post about this tribe last year but I wanted to add more information and of course this group has gained so many new members since last year, that most probably missed my previous post on this tribe. Also thanks to Netflix’ new show ‘the Barbarians’ the Chatti has gained more attention. Somewhere around 100BC, there was a huge internal conflict in the Chatti tribe, this conflict resulted in the split of the tribe. Two groups of Chatti tribesmen/women migrated towards the lower Rhine area in modern day Netherlands, this is how the Batavi and Cananefates were born.

The meaning of the tribe’s name isn’t 100% certain but most theories lead to the following meaning: ‘the angry’ or ‘the haters’ from the Proto-Germanic word Hataz. If this is the correct meaning of their name, it is quite a curious one. Why would a tribe call themselves like that? It might have something to do with a conflict that they experienced with another tribe or the conflict that caused the tribe to split back in 100BC. Perhaps the tribe’s name isn’t Germanic in origin at all. Another theory suggests that the word Chatti comes from the Proto-Celtic word Cat which means ‘battle’ or ‘fight’. If this is the case, the pronunciation is also different ‘Khatti’. Yet again these are just theories and nothing is 100% certain. The modern day region of Hesse, where the Chatti once lived, has most likely been named after the tribe.

The first written records about this tribe came from Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus, the stepson of emperor Augustus. After Germanicus was appointed as the governour of Gaul, he launched a series of campaigns into Germania in an attempt to conquer Germania just like how Gaul was conquered and added to the Roman empire. The first of his campaigns started in 12BC and was very succesful for Germanicus. He crossed the Rhine with his army and subjugated the Sicambri tribe. Germanicus was also the first Roman to reach the Weser river in northern Germany, close to modern day Denmark.

During a later campaign in the same year, he also subjugated the Batavi and the Frisii and defeated the Chauci at the river Weser. In the following year, 11BC, Germanicus defeated the Marsii, Bructeri and the Usipetes. From 10-9BC Germanicus also defeated the Chatti, Cherusci and Marcomanni. It seems as though nothing could stop him from conquering all of Germania, he almost succeeded at this until a fall from his horse during his fourth campaign killed him. It is likely that Germania would have become a Roman province if Germanicus didn’t fell off his horse.

It was during Drusus Germanicus’ campaigns that the famous Arminius of the Cherusci was sent to Rome as tribute by his father, together with his brother Flavus. Relationships between the Cherusci and the Romans continued to sour in the following years after their defeat by the Romans during Germanicus’ campaigns. This eventually led to Arminius revolting against the Romans in 9AD. The king of the Chatti, Adgandestrius, was quick to join Arminius. The Chatti also haven’t forgotten Germanicus’ campaigns in Germania. The revolt led to the famous Teutoburgerwald battle during which three Roman legions were completely destroyed

This battle would be the biggest military defeat for Rome. While Germanicus almost succeeded at conquering Germania, this battle led to the abandonment of all plans to expand the Roman empire into Germania. Permanent borders were established along the Rhine river which kept Germania free. Interestingly enough, Adgandestrius turned against Arminius in 19AD. He even went as far as to ask Rome for help in assassinating Arminius with poison. This request was denied by the Romans as they saw this as a dishonourable way to defeat Arminius, the Romans prefered to meet him in battle. Arminius died two years later, betrayed and murdered by his own people who thought that Arminius was getting way too powerful. (Hope I didn’t just spoil the show for you guys, I still haven’t watched it)

Almost half a century later, another conflict broke out, this time between the Chatti and the Hermunduri in 58AD. Both tribes fought for control over a river that was rich in salt that flowed between the two tribes. This whole conflict has been recorded by Tacitus who described that this river was also very religiously important to the Germanic people. It is not certain which river is mentioned by Tacitus, it is either the Rhine or Main (a river connected to the Rhine). The Germanic people believed that this river was closely connected to the realm of the Gods. If you would make a prayer at the banks of the river Rhine, it would be directly received by the Gods. Both tribes also vowed their enemies to Tyr and Wodan before the battle started. This vow meant that the defeated party was sacrificed to Tyr and Wodan, unfortunately for the Chatti, they lost this battle.

Another revolt broke out in 69AD, this time the Batavi revolted against the Roman empire. The Chatti also joined this rebellion, even though the Batavi were once part of the Chatti and left due to a conflict. The Batavi were able to destroy two Roman legions and several Roman fortifications before the revolt was put down. The Chatti laid siege to Mogontiacum, modern day city of Mainz. Even though the Romans lost their trust in the Batavi, they recognized their strong fighting power and are named the strongest of all the Germanic tribes, not in number but in skills.

20 years later in 89AD, the Chatti joined another revolt. This time two Roman legions under Antoninus Saturninus revolted against emperor Dominitan. Unfortunately all documents describing this event are lost or destroyed so we can sadly never know what event led to two Roman legions revolting against their emperor. There is a theory that the revolt was caused by Dominitan’s strict moral policies for the officers of the army. The revolt however failed before it could really begin. It would have been interesting to observe this revolt if it had succeeded, a curious sight Romans and Chatti warriors fighting side by side.

In 98AD Tacitus published his famous work the Germania, in this work he describes the Chatti as following:

“Beyond these dwell the Chatti, whose settlements, beginning from the Hercynian forest, are in a tract of country less open and marshy than those which overspread the other states of Germany, for it consists of a continued range of hills, which gradually become more scattered and the Hercynian forest both accompanies and leaves behind, its Chatti.

This nation is distinguished by hardier frames, compactness of limb, fierceness of countenance, and superior vigor of mind. For Germanics, they have a considerable share of understanding and sagacity, they choose able persons to command, and obey them when chosen, keep their ranks, seize opportunities, restrain impetuous motions, distribute properly the business of the day, intrench themselves against the night, account fortune dubious, and valor only certain, and, what is extremely rare, and only a consequence of discipline, depend more upon the general than the army.

Their force consists entirely in infantry who, besides their arms, are obliged to carry tools and provisions. Other nations appear to go to a battle, the Chatti, to war. Excursions and casual encounters are rare amongst them. It is, indeed, peculiar to cavalry soon to obtain, and soon to yield, the victory. Speed borders upon timidity slow movements are more akin to steady valor.

A custom followed among the other Germanic nations only by a few individuals, of more daring spirit than the rest, is adopted by general consent among the Chatti. From the time they arrive at years of maturity they let their hair and beard grow and do not divest themselves of this votive badge, the promise of valor, till they have slain an enemy. Over blood and spoils they unveil the countenance, and proclaim that they have at length paid the debt of existence, and have proved themselves worthy of their country and parents. The cowardly and effeminate continue in their squalid disguise.

The bravest among them wear also an iron ring (a mark of ignominy in that nation) as a kind of chain, till they have released themselves by the slaughter of a foe. Many of the Chatti assume this distinction, and grow hoary under the mark, conspicuous both to foes and friends. By these, in every engagement, the attack is begun: they compose the front line, presenting a new spectacle of terror. Even in peace they do not relax the sternness of their aspect. They have no house, land, or domestic cares, they are maintained by whomsoever they visit, lavish of another's property, regardless of their own till the debility of age renders them unequal to such a rigid course of military virtue.” – Tacitus

Not much is further known about the Chatti besides the fact that they raided Roman territory between 160-170AD. Eventually elements of the Chatti, together with the Batavi, Cherusci, Tencteri, Tubantes, Chamavi, Bructeri, Sicambri and the Ampsivarii formed together in a confederation called the Franks. They settled in modern day southern Netherlands and Belgium around 300AD and were first of the Franks who eventually founded modern day France. The remaining Chatti remained in their original location and continued raiding the Romans wherever they could, by 300AD the Roman western borders were severely weakened by internal conflicts.

Eventually the remaining Chatti became the Hessi during the early medieval ages, this was first recorded in 782AD. Hesse itself has a long and rich history but that is not a topic for this group, feel free to explore this topic further if you are interested in Hesse’s history.

Here is a map which shows the location of the Chatti, a map showing Roman campaigns into Germania before the Teutoburgerwald battle and a depiction of Germanic warriors from the game Rome 2 total war.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay. Okay. Okay.

Let me just call out the elephant in the room here.

This is Alexander, our ‘American Imperialism’ as it were. He is the final boss as it were of HetaCulpa. He is white. He is not mixed. He isn’t a POC. He is 100% Caucasian.

Neither of us are making a POC person, or someone of mixed race, the villain in this game, or a villain at all. That was never even on the table, and never crossed our minds in the first place. He’s essentially wearing the CSA’s skin, after discussion with multiple other hetalia historians (Thank you Mae). This man is American Imperialism in the flesh. He is wearing a cavalry officer’s uniform in the confederate army, because I cannot think of a better uniform to juxtipose Alfred’s regular ol’ enlisted union infantryman than this, nor a better cause to back for a scumlord like Alexander. You can’t get more American-brand imperialism than ‘I’m going to go to war because my super top-heavy agricultural economy literally depends on owning and exploiting people I think are subhuman for free labor and I’m gonna play the victim for the next 150 years when I lose. Fuck you, Washington can’t tell me what to do. Eat my taint, centralized government-that-I-don’t-agree-with. I’m going to make my own centralized government-that-I-agree-with. Come at me and I’ll cane your statesmen again’.

...other than literally making him Satan.

...which, I mean, close enough.

#Technically Hetaculpa spoilers#But I want to nip this shit in the bud#This has come up again and again and again#I keep saying it on-stream#but here's physical proof

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

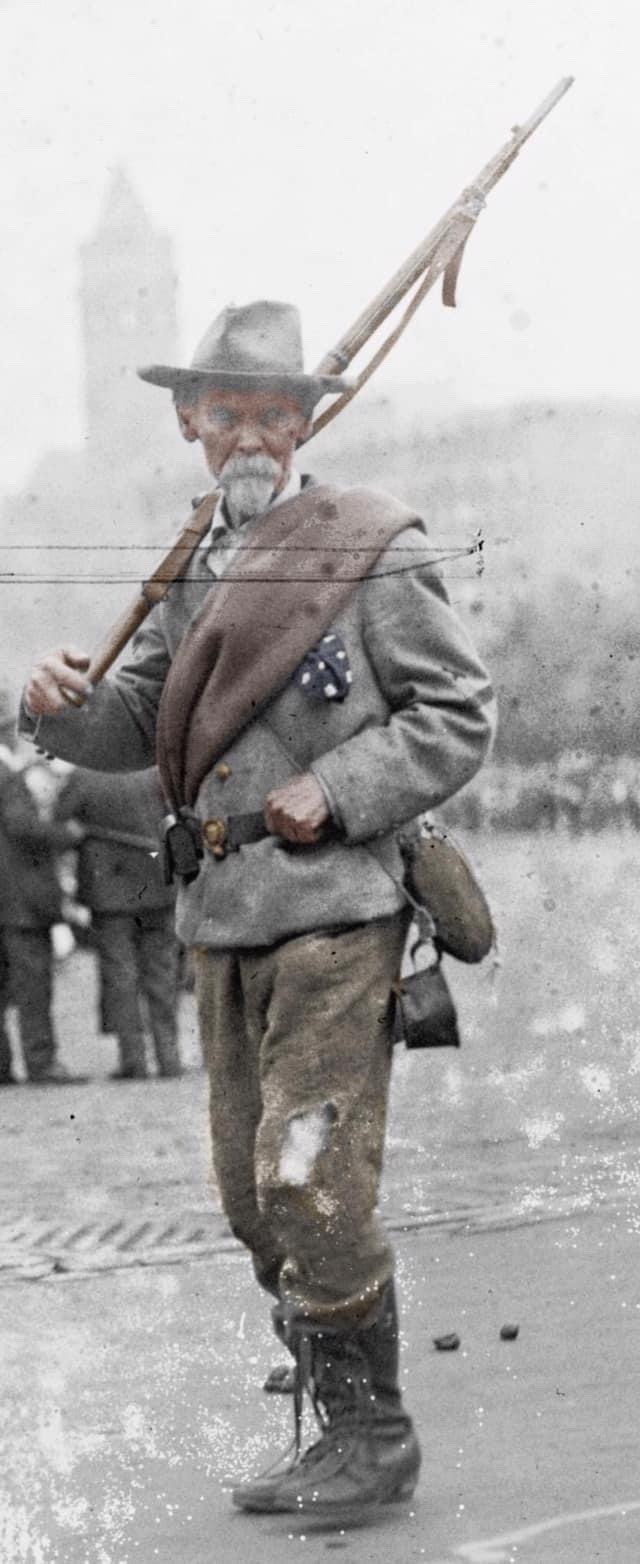

Confedetate Veteran Sergeant Berry Greenwood Benson.

Washington D.C. Confedetate Veterans Reunion And Parade 1917.

He wears the uniform he wore the day he walked home in 1865 carrying his rifle he carried that day as well.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Berry Benson was born on Feburary 9th 1843 in Hamburg, South Carolina, just across the Savannah river from Augusta, Georgia. In 1860 Berry Benson enlisted with his brother in a local militia unit aged 17 and 15 respectively. The next spring they witnessed the bombardment of Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina.

After the surrender of Fort Sumter the 1st South Carolina Regiment was sent to Virginia where the Benson brothers served under A.P. Hill and Thomas Jackson. The unit fought in battles such as Second Manassas, Fredericksburg, Antietam, and served in Jackson's valley campaign as Jackson's foot cavalry. Berry Benson was wounded at Chancellorsville and thus missed the battle of Gettysburg.

But he had recuperated by winter 1863 and returned to his unit where he was appointed as a scout.

The spring of 1864 brought another Union offensive into The Wilderness.

After a confusing, bloody battle in dense woods, the Union commander, General Ulysses S. Grant, attempted to get around the Confederate army and march on Richmond, Virginia, but was checked at Spotsylvania, Virginia. There followed one of the most terrible battles of the Civil War, in which the severest action occurred at the "Bloody Angle," where Benson fought.

By then the young soldier had won a reputation for scouting enemy positions.

At Spotsylvania he reconnoitered the Union camp and on an impulse stole a Yankee colonel's horse, leading it back to Confederate lines. Sent out a second time on Lee's orders, he was captured and imprisoned at the military prison in Point Lookout, Maryland.

On the second day of his captivity, Benson slipped unseen into the waters of Chesapeake Bay and swam two miles to escape but unfortunately for him he was recaptured in Union-occupied Virginia, and then was sent first to the Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D.C., then to the new prison camp at Elmira, New York.

What happened next is the Civil War's version of "The Great Escape."

Once there he joined a group attempting to tunnel out but the effort was discovered and broken up.

Soon thereafter on October 7, 1864 at four o'clock in the morning he and nine

companions entered a tunnel sixty-six feet long which they had been digging for about two

months.

The earth extracted had been carried away in their haversacks and disposed of.

On reaching the outside of the stockade the prisoners scattered in parties of two and three, Sergeant Benson going alone, since the companion he had intended to take with him failed to escape.

He headed south and miraculously reached Confedetate lines.

Sergeant Benson, half a century later, still preserved the passes given him from Newmarket, Virginia, where he first reached Early's army, to Richmond.

He wrote in 1911 that the men who made their escape were:

Washington B. Trawiek,

of the Jeff. Davis Artillery, Alabama, then living at Cold Springs, Texas; John Fox Maull, of

the Jeff. Davis Artillery, deceased; J. P. Putegnat, deceased; G. G. Jackson of Wetumpka, Alabama;

William Templin, of Paunsdale, Alabama; J.P.Scruggs, of Limestone Springs, South Carolina;

Cecrops Malone, of Company F. Ninth Alabama Infantry, then living at Waldron, Ark.; Crawford

of the Sixth Virginia Cavalry, and Glenn.

Most of them were present at Appomattox.

Upon learning of the surrender of General Johnson in North Carolina Benson and his brother walked home.

In 1868 Sargent Benson married his wife Jeannie Oliver with whom he had six children with and, while working as an accountant, developed a complex book-keeping method that he called the “Zero System” and sold it to companies all over the country.

He and his wife wrote poetry for publication, and his wife and daughters were all fine pianists.

One of his daughters studied violin in New York and became a concert performer.

Berry Benson became an advocate for striking mill workers and worked on developing high-protein food crops for poor black sharecroppers.

Benson also became a nationally known puzzle solver, breaking a secret French code known as the"Undecipherable Cipher," in 1896 (On a challenge) and informed the U.S. War Department that he had done so.

During the Spanish-American War Benson offered his services to the United States Government but unfortunately the war ended before he could be of use.

He was perhaps best known, however, for his private investigation into the case of Leo Frank, an Atlanta factory manager accused of raping and murdering 13-year-old Mary Phagan in 1913. Perceiving discrepancies in prosecution testimony, Benson concluded Frank was innocent. His logical arguments persuaded the Georgia governor that there was enough uncertainty in the case to commute Frank’s sentence from death to life imprisonment, but that did not prevent the accused’s subsequent lynching.

He also headed a campaign to support French war orphans in World War I and convinced his friends and neighbors to adopt some of them.

He later advised the U.S. attorney general of the possibility of fraud involving European and American fiscal exchange rates and, when he became aware of the activities of Carlo Ponzi, specifically warned the Massachusetts attorney general of the original “Ponzi Scheme.”

In the midst of this productive life, Benson became an officer in the Confederate Survivors Association and was chosen to model for the statue of the infantryman atop the Augusta monument, which was dedicated in 1878.

Even in advanced age Berry Benson remained fit and active leading boy scouts on fifteen mile hikes and attending veteran reunions and parades until his death on January 1st 1923 he was 79.

"In time, even death itself might be abolished; who knows but it may be given to us after this life to meet again in the old quarters, to play chess and draughts, to get up soon to answer the morning role call, to fall in at the tap of the drum for drill and dress parade, and again to hastily don our war gear while the monotonous patter of the long roll summons to battle.

Who knows but again the old flags, ragged and torn, snapping in the wind, may face each other and flutter, pursuing and pursued, while the cries of victory fill a summer day? And after the battle, then the slain and wounded will arise, and all will meet together under the two flags, all sound and well, and there will be talking and laughter and cheers, and all will say, Did it not seem real? Was it not as in the old days?”

~ 1st Seargent Berry Greenwood Benson 1st South Carolina Infantry Regiment Company H.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

CIVIL WAR | BIOGRAPHY Philip Sheridan

CIVIL WAR | BIOGRAPHY

Philip Sheridan

Philip Henry Sheridan was once depicted by Abraham Lincoln as "An earthy colored, thick little chap, with a long body, short legs, insufficient neck to hang him, and such long arms that if his lower legs tingle he can scratch them without stooping." Still, "Little Phil" rose to enormous force and acclaim before his inconvenient demise of a respiratory failure at age 57.

He is generally acclaimed for his annihilation of the Shenandoah Valley in 1864, called "The Burning" by its inhabitants. He was additionally the subject of an incredibly well known sonnet named "Sheridan's Ride", where he (and his acclaimed horse, Rienzi) make all the difference by showing up without a moment to spare for the Battle of Cedar Creek.

Like Patrick Cleburne, Sheridan rose rapidly in position. In the fall of 1861, Sheridan was a staff official for Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck. He later became officer general in the Army of Southwest Missouri. With the assistance of persuasive companions he was selected Colonel of the second Michigan Cavalry in May, 1862. His first fight, Booneville, MS, intrigued Brig. Gen. William S. Rosecrans such a lot of that he, when all is said and done, was elevated to Brigadier General. After Stones River he was elevated to Major General.

Sheridan's men were essential for the powers which caught Missionary Ridge (close to Chattanooga) in 1863. At the point when Ulysses S. Award was elevated to General-in-Chief of the Union armed forces, he made Sheridan the authority of the Army of the Potomac's Cavalry Corps. This moved him from the Western Theater toward the Eastern Theater of activities. From the start, Sheridan's Corps was utilized for observation. His men were sent on a key striking mission toward Richmond in May 1864. At that point he battled with blended achievement in Grant's 1864 Overland Campaign.

During the Civil War, Virginia's Shenandoah Valley was an essential asset to the Confederacy. In addition to the fact that it served as the Confederate "breadbasket", it was a significant transportation course. The locale had seen two enormous scope crusades as of now when Gen. Ulysses S. Award chose to visit the Valley indeed in 1864. He sent Philip Sheridan set for make the Shenandoah Valley a "desolate waste".

In September, Sheridan crushed Jubal Early's more modest power at Third Winchester, and again at Fisher's Hill. At that point he started "The Burning" – annihilating stables, plants, rail lines, production lines – obliterating assets for which the Confederacy had a desperate need. He made more than 400 square miles of the Valley dreadful. "The Burning" foreshadowed William Tecumseh Sherman's "Walk to the Sea": another mission to deny assets to the Confederacy just as bring the conflict home to its regular citizens.

In October, be that as it may, Jubal Early found Sheridan napping. Early dispatched an unexpected assault at Cedar Creek on the nineteenth. Sheridan, nonetheless, was ten miles away in Winchester, Virginia. After hearing the sound of mounted guns shoot, Sheridan hustled to rejoin his powers. He showed up without a moment to spare to get everyone excited. Early's men, nonetheless, were experiencing appetite and started to plunder the unwanted Union camps. The activities of Sheridan (and Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright) halted the Union retreat and managed a serious hit to Early's military.

For his activities at Cedar Creek, Sheridan was elevated to Major General in the customary armed force. He likewise got a letter of appreciation from President Abraham Lincoln. The general enjoyed extraordinary Thomas Buchanan Read's sonnet, "Sheridan's Ride" – to such an extent that he renamed his pony "Winchester". The Union triumphs in the Shenandoah Valley came in the nick of time for Abraham Lincoln and aided the Republicans rout Democratic applicant George B. McClellan in the appointment of 1864.

Throughout the spring of 1865, Sheridan sought after Lee's military with hounded assurance. He caught Early's military in March. In April, Gen. Lee had to empty Petersburg when Sheridan remove his lines of help at Five Forks. Furthermore, at Sayler's Creek, he caught very nearly one fourth of Lee's military. At long last at Appomattox, Lee had to give up the Army of Northern Virginia when Sheridan's powers obstructed Lee's break course.

At war's end, Phil Sheridan was a legend to numerous Northerners. Gen. Award held him in the most elevated regard. In any case, Sheridan was not without his issues. He had stretched Grant's requests to the edge. He likewise eliminated Gettysburg legend Gouverneur Warren from order. It was subsequently decided that Warren's evacuation was ridiculous and inappropriate.

During Reconstruction, Sheridan was named to be the military legislative head of Texas and Louisiana (the Fifth Military District). Due to the seriousness of his organization there, President Andrew Johnson pronounced that Sheridan was a dictator and had him eliminated.

In 1867, Ulysses S. Award accused Sheridan of mollifying the Great Plains, where fighting with Native Americans was unleashing devastation. With an end goal to constrain the Plains individuals onto reservations, Sheridan utilized similar strategies he utilized in the Shenandoah Valley: he assaulted a few clans in their colder time of year quarters, and he advanced the far and wide butcher of American buffalo, their essential wellspring of food.

In 1871, the overall regulated military aid ventures during the Great Chicago Fire. He turned into the Commanding General of the United States Army on November 1, 1883, and on June 1, 1888, he was elevated to General of the Army of the United States – a similar position accomplished by Ulysses S. Award and William Tecumseh Sherman.

Sheridan is additionally generally answerable for the foundation of Yellowstone National Park – saving it from being offered to engineers.

In August 1888, Sheridan passed on after a progression of monstrous coronary failures. He was covered at Arlington National Cemetery.

Read more about Philip Sheridan

1 note

·

View note

Text

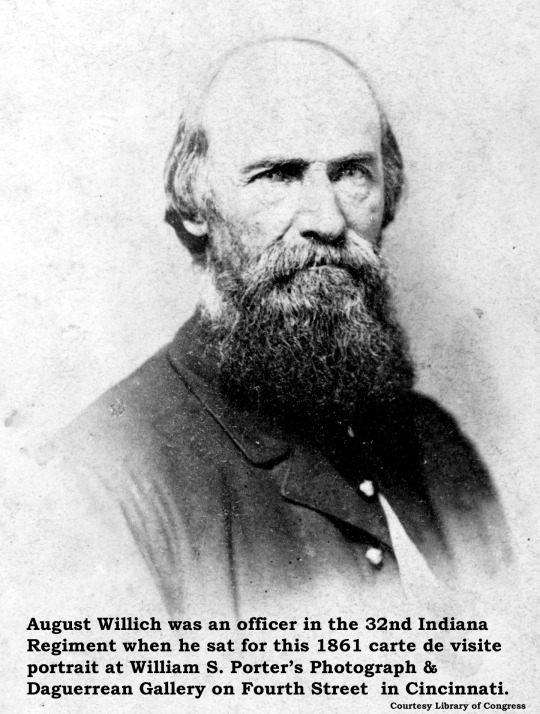

The Baddest Of All Cincinnati Badasses: Major General August Willich

He was born into German nobility as Johann August Ernst von Willich. Rumor had it that he was the illegitimate son of the Prussian crown prince. Before he died in obscure poverty, Willich:

Gave up his noble name,

Led two revolutionary armies,

Challenged Karl Marx to a duel,

Raised two regiments during the Civil War,

Defeated the Texas Rangers in battle,

Conducted rifle drills – on the battlefield,

Endured months in a Confederate prison,

Defied exile by returning to Germany, and

Volunteered at age 60 to fight in the Franco-Prussian War.

August Willich was the proletarian name he adopted to show solidarity with the working classes. He amazed everyone who met him. His family, as indicated by that “von,” was noble and Willich lived up to their expectations for 38 years. He was born in 1810 in East Prussia, now part of Poland, in a town on the Baltic coast. By the age of three, he was an orphan, and was adopted by Friedrich Schleiermacher, an acclaimed theologian and philosopher, who provided Willich with an excellent classical education. As a teenager, Willich was sent off to Potsdam and Berlin for a military education and he served 19 years in the Prussian army, rising to the rank of captain.

By 1846, Willich’s study of philosophy had convinced him that the oppression of workingmen was unbearable, so he resigned his military commission. His letter of resignation was so strongly worded that, rather than accept it, the Prussian army had him arrested and court-martialed.

Willich was eventually allowed to leave military service and he took up the tools of a carpenter, marching past his old battalion with an axe, rather than a rifle over his shoulder. In 1848, revolution broke out in many places throughout Europe, and Willich volunteered to lead a democratic army in a failed attempt to expunge royalty from the Baden-Palatinate region. Throughout these ultimately unsuccessful campaigns, Willich’s aide de camp was Friedrich Engels, later co-author of the Communist Manifesto.

Imperial forces suppressed the revolution and Willich, like many “Forty-Eighters,” found himself exiled, first to Switzerland and then to England. Introduced to Karl Marx by his former aide, Willich quickly assumed a leadership role in the socialist organization taking root among the German exiles. Willich found Marx way too conservative.

Mary Gabriel, in her 2011 book, “Love and Capital: Karl and Jenny Marx and the Birth of a Revolution,” describes the friction between the two revolutionaries:

“At the same time Willich was turning to extremists for support, he also made overtures to the petit bourgeois democrats Marx and Engels had thrown off their refugee committee the previous year. Willich lobbied the committee to once again join with the democrats, arguing that a unified position would strengthen their efforts. When his idea was rejected, he resigned in a huff from the Communist League’s Central Authority. Several days later, however, apparently looking for a fight, Willich attended a league meeting, where he proceeded to insult Marx and finally challenge him to a duel.”

Marx and Willich never met on the field of honor, but Willich wounded a young Marxist in a proxy gunfight fought in Belgium. With his welcome in London worn out, Willich sailed for America where, after a few years as a carpenter in the Brooklyn shipyards and as a mathematician with the U.S. coastal survey, he accepted an invitation to edit a German-language Republican newspaper in Cincinnati.

When the Civil War erupted, Cincinnati Germans responded so quickly that, within a week, 1,500 men had enlisted in what became the legendary Ninth Ohio Infantry Regiment, known as “Die Neuner.” Although Willich was among the more experienced recruits, another man, the only non-German in the regiment, was selected as commander – a political decision made in hopes of speeding up delivery of supplies and weaponry. Although he drilled the Ninth and marched with them into Virginia, Willich resigned to assume command of another German regiment, Indiana’s Thirty-Second.

At Chickamauga, Perrysville and Missionary Ridge, Willich’s troops earned a reputation as hard-fighting, disciplined soldiers. In the Battle of Green River, three companies of Willich’s men routed 8,000 Confederate troops led by the Texas Rangers cavalry.

At Shiloh, Willich performed a feat of leadership that astounded General Lew Wallace, who witnessed it first-hand. Plunging into the fiercest fighting, Willich’s troops began to falter and give way. A rout was imminent but, as Wallace wrote in his autobiography:

“Then an officer rode swiftly round their left flank and stopped when in front of them, his back to the enemy. What he said I could not hear, but from the motions of the men he was putting them through the manual of arms – this notwithstanding some of them were dropping in the ranks. Taken all in all, that I think was the most audacious thing that came under my observation during the war. The effect was magical.”

In the Battle of Stones River, Willich’s horse was shot out from beneath him and he was captured. He spent months in prison but used the time to design a new method of rapid-fire attack he implemented as soon as he was freed in a prisoner exchange. Willich also pioneered the use of bugle calls to direct troops in battle. When he was mustered out, he held the rank of brevet major general. His right arm, wounded in battle in Georgia, was mostly paralyzed for the rest of his life.

After the war, Willich served briefly as Hamilton County Auditor, neglecting the many opportunities to get rich from that position. According to the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune [24 January 1878]:

“Impracticable – like a child in matters of finance – he squandered the generous proceeds of his office in visionary business schemes and on his friends, and retired with very little. His intimate friends say of him that he would throw away a hundred thousand a year if he had it, and that he could live on a hundred a year if he had to.”

When France and Germany went to war in 1870, Willich was at the University of Berlin, defying his banishment to study philosophy. He approached the emperor to volunteer his services, but his age, infirmity and – no doubt – his Communist past led to rejection.

Willich returned to Cincinnati and later moved to St. Mary’s, Ohio, where he boarded with his former adjutant, Charles Hipp, and studied philosophy and music. On his death, the New York Times [24 January 1878] stated:

“Gen. Willich was undoubtedly the ablest and bravest officer of German descent engaged in the war of the rebellion, and owed his preferment wholly to his untiring energy, bravery in the field, and marked abilities.”

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One of several “Boy Generals” during the Civil War, Francis Channing Barlow’s looks were deceiving. Slightly built, clean shaven, with a high-pitched voice, he was nevertheless a demanding officer who would tolerate no dereliction of duty on the part of his men. Col. Theodore Lyman, an aide to Maj. Gen. George G. Meade described Barlow this way: “He looked like a highly independent newsboy; he was attired in a flannel checked shirt; a threadbare pair of trousers; from his waist hung a big cavalry saber; his features wore a familiar sarcastic smile…{yet} it would be hard to find a general officer equal to him.”

Born on October 19, 1834, Barlow’s rise through the ranks was not the result of any military training prior to the Civil War. Graduating from Harvard Law School at the top of his class in 1855, Barlow was working at the New York Tribune at the outset of the war. One day after his marriage top Arabella Griffith, Barlow enlisted in the 12 NY Militia as a private. Barlow rose to become a highly successful general officer solely on the basis of his abilities as a soldier.

On September 17, 1862 Col. Barlow found himself and his regiment in front of the infamous “Bloody Lane” at Antietam. Severely wounded while leading his troops in pursuit of the retreating Confederates, Barlow was eventually nursed back to health by his wife, a nurse with the U.S. Sanitary Commission. A promotion to Brevet Brigadier General preceded his next combat experience at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May, 1863. Since his brigade (part of the XI Corps) was off supporting the III Corps during “Stonewall” Jackson’s famous flank attack, it escaped the ridicule directed at the XI Corps after Chancellorsville. Again severely wounded on July 1, 1863 at Gettysburg, both Union and Confederate surgeons deemed the wounds mortal. But again Arabella, his wife, was able to nurse him back to health. Following a lengthy convalescence, Barlow returned to duty in spring, 1864 at the beginning of the Overland Campaign. Now commanding a division in the II Corps, Barlow and his troops would be at the forefront of the fighting at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House and Cold Harbor. On May 12, in particular, Barlow’s division would spearhead a massive assault against the “Mule Shoe Salient” at Spotsylvania. Along with the rest of the II Corps, Barlow’s troops captured 3,000 Confederate soldiers (including 2 generals), 20 cannon and 30 stands of colors. During the Siege of Petersburg in July, 1864 Barlow’s wife died of typhus and his own health deteriorated. Following a medical leave of absence he returned to duty in time for Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House in April, 1865.

After the war Barlow served as a U.S. Marshal, New York Secretary of State and New York Attorney General. He was also one of the founders of the American Bar Association. In 1866 he married Ellen Shaw, sister of Robert Gould Shaw who had died while leading the 54th MA regiment against Battery Wagner near Charleston, SC. The couple had 3 children. Francis C. Barlow died in New York City on January 11, 1896.

#francis c barlow#francis channing barlow#civil war#history#you'd think barlow would have more photos...but he doesn't!#ol angry francis and his sword that he would hit people with...very rude lol

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

nother Civil War obelisk erected by Confederate Veterans in 1910. This one is Summit Point West Virginia.

http://jeffersoncountyhlc.org/index.php/about-us-3/heritage-tourism/military-options-in-jefferson-county-virginia-now-west-virginia-1861-1865/