#ieltsacademicreading

Text

IELTS Practice Cambridge Book 8 Academic Reading Test 1 C8T1

IELTS Practice Cambridge Book 8 Academic Reading Test 1 C8T1. Practice IELTS Reading practice online our website to score higher bands in your reading exam.

A Chronicle of Timekeeping

A According to archaeological evidence, at least 5,000 years ago, and long before the advent of the Roman Empire, the Babylonians began to measure time, introducing calendars to co-ordinate communal activities, to plan the shipment of goods and, in particular, to regulate planting and harvesting. They based their calendars on three natural cycles: the solar day, marked by the successive periods of light and darkness as the earth rotates on its axis; the lunar month, following the phases of the moon as it orbits the earth; and the solar year, defined by the changing seasons that accompany our planet’s revolution around the sun.

B Before the invention of artificial light, the moon had greater social impact. And, for those living near the equator in particular, its waxing and waning was more conspicuous than the passing of the seasons. Hence, the calendars that were developed at the lower latitudes were influenced more by the lunar cycle than by the solar year. In more northern climes, however, where seasonal agriculture was practised, the solar year became more crucial. As the Roman Empire expanded northward, it organised its activity chart for the most part around the solar year.

C Centuries before the Roman Empire, the Egyptians had formulated a municipal calendar having 12 months of 30 days, with five days added to approximate the solar year. Each period of ten days was marked by the appearance of special groups of stars called decans. At the rise of the star Sirius just before sunrise, which occurred around the all-important annual flooding of the Nile, 12 decans could be seen spanning the heavens. The cosmic significance the Egyptians placed in the 12 decans led them to develop a system in which each interval of darkness (and later, each interval of daylight) was divided into a dozen equal parts. These periods became known as temporal hours because their duration varied according to the changing length of days and nights with the passing of the seasons. Summer hours were long, winter ones short; only at the spring and autumn equinoxes were the hours of daylight and darkness equal. Temporal hours, which were first adopted by the Greeks and then the Romans, who disseminated them through Europe, remained in use for more than 2,500 years.

D In order to track temporal hours during the day, inventors created sundials, which indicate time by the length or direction of the sun’s shadow. The sundial’s counterpart, the water clock, was designed to measure temporal hours at night. One of the first water clocks was a basin with a small hole near the bottom through which the water dripped out. The falling water level denoted the passing hour as it dipped below hour lines inscribed on the inner surface. Although these devices performed satisfactorily around the Mediterranean, they could not always be depended on in the cloudy and often freezing weather of northern Europe.

E The advent of the mechanical clock meant that although it could be adjusted to maintain temporal hours, it was naturally suited to keeping equal ones. With these, however, arose the question of when to begin counting, and so, in the early 14th century, a number of systems evolved. The schemes that divided the day into 24 equal parts varied according to the start of the count: Italian hours began at sunset, Babylonian hours at sunrise, astronomical hours at midday and ‘great clock’ hours, used for some large public clocks in Germany, at midnight. Eventually these were superseded by ‘small clock’, or French, hours, which split the day into two 12-hour periods commencing at midnight.

F The earliest recorded weight-driven mechanical clock was built in 1283 in Bedfordshire in England. The revolutionary aspect of this new timekeeper was neither the descending weight that provided its motive force nor the gear wheels (which had been around for at least 1,300 years) that transferred the power; it was the part called the escapement. In the early 1400s came the invention of the coiled spring or fusee which maintained constant force to the gear wheels of the timekeeper despite the changing tension of its mainspring. By the 16th century, a pendulum clock had been devised, but the pendulum swung in a large arc and thus was not very efficient.

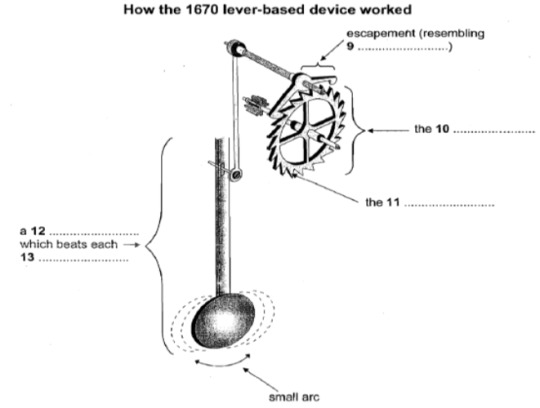

G To address this, a variation on the original escapement was invented in 1670, in England. It was called the anchor escapement, which was a lever-based device shaped like a ship’s anchor. The motion of a pendulum rocks this device so that it catches and then releases each tooth of the escape wheel, in turn allowing it to turn a precise amount. Unlike the original form used in early pendulum clocks, the anchor escapement permitted the pendulum to travel in a very small arc. Moreover, this invention allowed the use of a long pendulum which could beat once a second and thus led to the development of a new floor standing case design, which became known as the grandfather clock.

H Today, highly accurate timekeeping instruments set the beat for most electronic devices. Nearly all computers contain a quartz-crystal clock to regulate their operation. Moreover, not only do time signals beamed down from Global Positioning System satellites calibrate the functions of precision navigation equipment, they do so as well for mobile phones, instant stock-trading systems and nationwide power-distribution grids. So integral have these time-based technologies become to day-to-day existence that our dependency on them is recognised only when they fail to work.

Questions 1-4

Reading Passage 1 has eight paragraphs, A-H. Which paragraph contains the following information? Write the correct letter, A-H, in boxes 1- 4 on your answer sheet.

1 a description of an early timekeeping invention affected by cold temperatures

2 an explanation of the importance of geography in the development of the calendar in farming communities

3 a description of the origins of the pendulum clock

4 details of the simultaneous efforts of different societies to calculate time using uniform hours

Questions 5-8

Look at the following events (Questions 5-8) and the list of nationalities below. Match each event with the correct nationality, A-F. Write the correct letter, A-F, in boxes 5-8 on your answer sheet.

5 They devised a civil calendar in which the months were equal in length.

6 They divided the day into two equal halves.

7 They developed a new cabinet shape for a type of timekeeper.

8 They created a calendar to organise public events and work schedules.

A Babylonians

B Egyptians

C Greeks

D English

E Germans

F French

Questions 9-13

Label the diagram below. Write NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage.

Download All Cambridge IELTS Books Pdf + Audio For Free Cambridge 1-14 (Free Download)

AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL IN THE USA

A An accident that occurred in the skies over the Grand Canyon in 1956 resulted in the establishment of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to regulate and oversee the operation of aircraft in the skies over the United States, which were becoming quite congested. The resulting structure of air traffic control has greatly increased the safety of flight in the United States, and similar air traffic control procedures are also in place over much of the rest of the world.

B Rudimentary air traffic control (АТС) existed well before the Grand Canyon disaster. As early as the 1920s, the earliest air traffic controllers manually guided aircraft in the vicinity of the airports, using lights and flags, while beacons and flashing lights were placed along cross-country routes to establish the earliest airways. However, this purely visual system was useless in bad weather, and, by the 1930s, radio communication was coming into use for АТС. The first region to have something approximating today’s АТС was New York City, with other major metropolitan areas following soon after.

C In the 1940s, АТС centres could and did take advantage of the newly developed radar and improved radio communication brought about by the Second World War, but the system remained rudimentary. It was only after the creation of the FAA that full-scale regulation of America’s airspace took place, and this was fortuitous, for the advent of the jet engine suddenly resulted in a large number of very fast planes, reducing pilots’ margin of error and practically demanding some set of rules to keep everyone well separated and operating safely in the air.

D Many people think that АТС consists of a row of controllers sitting in front of their radar screens at the nation’s airports, telling arriving and departing traffic what to do. This is a very incomplete part of the picture. The FAA realised that the airspace over the United States would at any time have many different kinds of planes, flying for many different purposes, in a variety of weather conditions, and the same kind of structure was needed to accommodate all of them.

E To meet this challenge, the following elements were put into effect. First, АТС extends over virtually the entire United States. In general, from 365m above the ground and higher, the entire country is blanketed by controlled airspace. In certain areas, mainly near airports, controlled airspace extends down to 215m above the ground, and, in the immediate vicinity of an airport, all the way down to the surface. Controlled airspace is that airspace in which FAA regulations apply. Elsewhere, in uncontrolled airspace, pilots are bound by fewer regulations. In this way, the recreational pilot who simply wishes to go flying for a while without all the restrictions imposed by the FAA has only to stay in uncontrolled airspace, below 365m, while the pilot who does want the protection afforded by АТС can easily enter the controlled airspace.

F The FAA then recognised two types of operating environments. In good meteorological conditions, flying would be permitted under Visual Flight Rules (VFR), which suggests a strong reliance on visual cues to maintain an acceptable level of safety. Poor visibility necessitated a set of Instrumental Flight Rules (IFR), under which the pilot relied on altitude and navigational information provided by the plane’s instrument panel to fly safely. On a clear day, a pilot in controlled airspace can choose a VFR or IFR flight plan, and the FAA regulations were devised in a way which accommodates both VFR and IFR operations in the same airspace. However, a pilot can only choose to fly IFR if they possess an instrument rating which is above and beyond the basic pilot’s license that must also be held.

G Controlled airspace is divided into several different types, designated by letters of the alphabet. Uncontrolled airspace is designated Class F, while controlled airspace below 5,490m above sea level and not in the vicinity of an airport is Class E. All airspace above 5,490m is designated Class A. The reason for the division of Class E and Class A airspace stems from the type of planes operating in them. Generally, Class E airspace is where one finds general aviation aircraft (few of which can climb above 5,490m anyway), and commercial turboprop aircraft. Above 5,490m is the realm of the heavy jets, since jet engines operate more efficiently at higher altitudes. The difference between Class E and A airspace is that in Class A, all operations are IFR, and pilots must be instrument-rated, that is, skilled and licensed in aircraft instrumentation. This is because АТС control of the entire space is essential. Three other types of airspace, Classes D, С and B, govern the vicinity of airports. These correspond roughly to small municipal, medium-sized metropolitan and major metropolitan airports respectively, and encompass an increasingly rigorous set of regulations. For example, all a VFR pilot has to do to enter Class С airspace is establish two-way radio contact with АТС. No explicit permission from АТС to enter is needed, although the pilot must continue to obey all regulations governing VFR flight. To enter Class В airspace, such as on approach to a major metropolitan airport, an explicit АТС clearance is required. The private pilot who cruises without permission into this airspace risks losing their license.

Questions 14-19

Reading passage 2 has seven paragraphs A-G. Choose the correct heading for paragraphs A and C-G from the list below. Write the correct number i-x in boxes 14-19 on your answer sheet.

List of Headings

i Disobeying FAA Regulations

ii Aviation disaster prompts action

iii Two coincidental developments

iv Setting Altitude Zones

v An oversimplified view

vi Controlling pilots’ licence

vii Defining airspace categories

viii Setting rules to weather conditions

ix Taking of Safety

x First step towards ATC

Example – Paragraph B x

14 Paragraph A

15 Paragraph C

16 Paragraph D

17 Paragraph E

18 Paragraph F

19 Paragraph G

Questions 20-26

Do the following statements agree with the given information of the reading passage? In boxes 20-26 on your answer sheet, write:

TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

20 The FAA was created as a result of the introduction of the jet engine.

21 Air traffic control started after the Grand Canyon crash in 1956.

22 Beacons and flashing lights are still used by the ATC today.

23 Some improvements were made in radio communication during World War II.

24 Class F airspace is airspace which is below 365m and not near airports.

25 All aircraft in class E airspace must use IFR.

26 A pilot entering class C airspace is flying over an average-sized city.

Telepathy

Since the 1970s, parapsychologists at leading universities and research institutes around the world have risked the derision of sceptical colleagues by putting the various claims for telepathy to the test in dozens of rigorous scientific studies. The results and their implications are dividing even the researchers who uncovered them.

Some researchers say the results constitute compelling evidence that telepathy is genuine. Other parapsychologists believe the field is on the brink of collapse, having tried to produce definitive scientific proof and failed. Sceptics and advocates alike do concur on one issue, however: that the most impressive evidence so far has come from the so-called ‘ganzfeld’ experiments, a German term that means ‘whole field’. Reports of telepathic experiences had by people during meditation led parapsychologists to suspect that telepathy might involve ‘signals’ passing between people that were so faint that they were usually swamped by normal brain activity. In this case, such signals might be more easily detected by those experiencing meditation-like tranquility in a relaxing ‘whole field’ of light, sound and warmth.

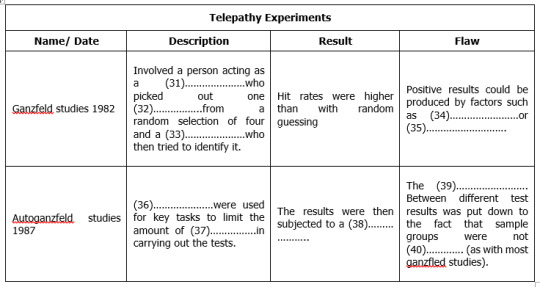

The ganzfeld experiment tries to recreate these conditions with participants sitting in soft reclining chairs in a sealed room, listening to relaxing sounds while their eyes are covered with special filters letting in only soft pink light. In early ganzfeld experiments, the telepathy test involved identification of a picture chosen from a random selection of four taken from a large image bank. The idea was that a person acting as a ‘sender’ would attempt to beam the image over to the ‘receiver’ relaxing in the sealed room. Once the session was over, this person was asked to identify which of the four images had been used. Random guessing would give a hit-rate of 25 per cent; if telepathy is real, however, the hit-rate would be higher. In 1982, the results from the first ganzfeld studies were analysed by one of its pioneers, the American parapsychologist Charles Honorton. They pointed to typical hit-rates of better than 30 per cent – a small effect, but one which statistical tests suggested could not be put down to chance.

The implication was that the ganzfeld method had revealed real evidence for telepathy. But there was a crucial flaw in this argument – one routinely overlooked in more conventional areas of science. Just because chance had been ruled out as an explanation did not prove telepathy must exist; there were many other ways of getting positive results. These ranged from ‘sensory leakage’ – where clues about the pictures accidentally reach the receiver – to outright fraud. In response, the researchers issued a review of all the ganzfeld studies done up to 1985 to show that 80 per cent had found statistically significant evidence. However, they also agreed that there were still too many problems in the experiments which could lead to positive results, and they drew up a list demanding new standards for future research.

After this, many researchers switched to autoganzfeld tests – an automated variant of the technique which used computers to perform many of the key tasks such as the random selection of images. By minimising human involvement, the idea was to minimise the risk of flawed results. In 1987, results from hundreds of autoganzfeld tests were studied by Honorton in a ‘meta-analysis’, a statistical technique for finding the overall results from a set of studies. Though less compelling than before, the outcome was still impressive.

Yet some parapsychologists remain disturbed by the lack of consistency between individual ganzfeld studies. Defenders of telepathy point out that demanding impressive evidence from every study ignores one basic statistical fact: it takes large samples to detect small effects. If, as current results suggest, telepathy produces hit-rates only marginally above the 25 per cent expected by chance, it’s unlikely to be detected by a typical ganzfeld study involving around 40 people: the group is just not big enough. Only when many studies are combined in a meta-analysis will the faint signal of telepathy really become apparent. And that is what researchers do seem to be finding.

What they are certainly not finding, however, is any change in attitude of mainstream scientists: most still totally reject the very idea of telepathy. The problem stems at least in part from the lack of any plausible mechanism for telepathy.

Various theories have been put forward, many focusing on esoteric ideas from theoretical physics. They include ‘quantum entanglement’, in which events affecting one group of atoms instantly affect another group, no matter how far apart they may be. While physicists have demonstrated entanglement with specially prepared atoms, no-one knows if it also exists between atoms making up human minds. Answering such questions would transform parapsychology. This has prompted some researchers to argue that the future lies not in collecting more evidence for telepathy, but in probing possible mechanisms. Some work has begun already, with researchers trying to identify people who are particularly successful in autoganzfeld trials. Early results show that creative and artistic people do much better than average: in one study at the University of Edinburgh, musicians achieved a hit-rate of 56 per cent. Perhaps more tests like these will eventually give the researchers the evidence they are seeking and strengthen the case for the existence of telepathy.

Questions 27-30

Complete each sentence with the correct ending, A —G, below. Write the correct letter, A—G, in boxes 27-30 on your answer sheet.

27 Researchers with differing attitudes towards telepathy agree on

28 Reports of experiences during meditation indicated

29 Attitudes to parapsychology would alter drastically with

30 Recent autoganzfeld trials suggest that success rates will improve with

A the discovery of a mechanism for telepathy.

B the need to create a suitable environment for telepathy.

C their claims of a high success rate.

D a solution to the problem posed by random guessing.

E the significance of the ganzfeld experiments.

F a more careful selection of subjects.

G a need to keep altering conditions.

Questions 31-40

Complete the table below. Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 31-40 on your answer sheet.

Show Answers

1. D

2. B

3. F

4. E

5. B

6. F

7. D

8. A

9. (ships’s) anchor

10. (escape) wheel

11. tooth

12. (long) pendulum

13. second

14. ii

15. iii

16. v

17. iv

18. viii

19. vii

20. false

21. false

22. not given

23. true

24. true

25. false

26. true

27. E

28. B

29. A

30. F

31. sender

32. picture/ image

33. receiver

34. sensory leakage

35. fraud

36. computers

37. human involvement

38. meta-analysis

39. lack of consistency

40. big/ large enough

Read the full article

#academicreading#c8t1#cambridge8#cambridgeacademicreading8#ielts8#ielts8reading1#ieltsacademicreading#reading

0 notes

Text

IELTS Practice Cambridge Book 7 Academic Reading Test 3 C7T3

Attitudes to Language

It is not easy to be systematic and objective about language study. Popular linguistic debate regularly deteriorates into invective and polemic. Language belongs to everyone, so most people feel they have a right to hold an opinion about it. And when opinions differ, emotions can run high. Arguments can start as easily over minor points of usage as over major policies of linguistic education.

Language, moreover, is a very public behaviour, so it is easy for different usages to be noted and criticised. No part of society or social behaviour is exempt: linguistic factors influence how we judge personality, intelligence, social status, educational standards, job aptitude, and many other areas of identity and social survival. As a result, it is easy to hurt, and to be hurt, when language use is unfeelingly attacked.

In its most general sense, prescriptivism is the view that one variety of language has an inherently higher value than others, and that this ought to be imposed on the whole of the speech community. The view is propounded especially in relation to grammar and vocabulary, and frequently with reference to pronunciation. The variety which is favoured, in this account, is usually a version of the ‘standard’ written language, especially as encountered in literature, or in the formal spoken language which most closely reflects this style. Adherents to this variety are said to speak or write ‘correctly’; deviations from it are said to be ‘incorrect!

All the main languages have been studied prescriptively, especially in the 18th century approach to the writing of grammars and dictionaries. The aims of these early grammarians were threefold: (a) they wanted to codify the principles of their languages, to show that there was a system beneath the apparent chaos of usage, (b) they wanted a means of settling disputes over usage, and (c) they wanted to point out what they felt to be common errors, in order to ‘improve’ the language. The authoritarian nature of the approach is best characterised by its reliance on ‘rules’ of grammar. Some usages are ‘prescribed,’ to be learnt and followed accurately; others are ‘proscribed,’ to be avoided. In this early period, there were no half-measures: usage was either right or wrong, and it was the task of the grammarian not simply to record alternatives, but to pronounce judgement upon them.

These attitudes are still with us, and they motivate a widespread concern that linguistic standards should be maintained. Nevertheless, there is an alternative point of view that is concerned less with standards than with the facts of linguistic usage. This approach is summarised in the statement that it is the task of the grammarian to describe, not prescribe to record the facts of linguistic diversity, and not to attempt the impossible tasks of evaluating language variation or halting language change. In the second half of the 18th century, we already find advocates of this view, such as Joseph Priestley, whose Rudiments of English Grammar (1761) insists that ‘the custom of speaking is the original and only just standard of any language! Linguistic issues, it is argued, cannot be solved by logic and legislation. And this view has become the tenet of the modern linguistic approach to grammatical analysis.

In our own time, the opposition between ‘descriptivists’ and ‘prescriptivists’ has often become extreme, with both sides painting unreal pictures of the other. Descriptive grammarians have been presented as people who do not care about standards, because of the way they see all forms of usage as equally valid. Prescriptive grammarians have been presented as blind adherents to a historical tradition. The opposition has even been presented in quasi-political terms – of radical liberalism vs elitist conservatism.

Questions 1-8

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Reading Passage 1?

In boxes 1-8 in your answer sheet, write:

YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

1 There are understandable reasons why arguments occur about language.

2 People feel more strongly about language education than about small differences in language usage.

3 Our assessment of a person’s intelligence is affected by the way he or she uses language.

4 Prescriptive grammar books cost a lot of money to buy in the 18th century.

5 Prescriptivism still exists today.

6 According to descriptivists it is pointless to try to stop language change.

7 Descriptivism only appeared after the 18th century.

8 Both descriptivists and prescriptivists have been misrepresented.

Questions 9-12

Complete the summary using the list of words, A-l, below.

The language debate

According to (9) …………. there is only one correct form of language. Linguists who take this approach to language place great importance on grammatical (10) ……………………. Conversely, the view of (11) ………….., such as Joseph Priestley, is that grammar should be based on (12) ………………….

A descriptivists

B language expert

C popular speech

D formal language

E evaluation

F rules

G modern linguists

H prescriptivists

I change

Question 13

Choose the correct letter A. B, C or D.

What is the writer’s purpose in Reading Passage?

A to argue in favour of a particular approach to writing dictionaries and grammar books

B to present a historical account of differing views of language

C to describe the differences between spoken and written language

D to show how a certain view of language has been discredited

Tidal Power

A Operating on the same principle as wind turbines, the power in sea turbines comes from tidal currents which turn blades similar to ships’ propellers, but, unlike wind, the tides are predictable and the power input is constant. The technology raises the prospect of Britain becoming self-sufficient in renewable energy and drastically reducing its carbon dioxide emissions. If tide, wind and wave power are all developed, Britain would be able to close gas, coal and nuclear power plants and export renewable power to other parts of Europe. Unlike wind power, which Britain originally developed and then abandoned for 20 years allowing the Dutch to make it a major industry, undersea turbines could become a big export earner to island nations such as Japan and New Zealand.

B Tidal sites have already been identified that will produce one sixth or more of the UK’s power – and at prices competitive with modern gas turbines and undercutting those of the already ailing nuclear industry. One site alone, the Pentland Firth, between Orkney and mainland Scotland, could produce 10% of the country’s electricity with banks of turbines under the sea, and another at Alderney in the Channel Islands three times the 1,200 megawatts of Britain’s largest and newest nuclear plant, Sizewell B, in Suffolk. Other sites identified include the Bristol Channel and the west coast of Scotland, particularly the channel between Campbeltown and Northern Ireland.

C Work on designs for the new turbine blades and sites are well advanced at the University of Southampton’s sustainable energy research group. The first station is expected to be installed off Lynmouth in Devon shortly to test the technology in a venture jointly funded by the department of Trade and Industry and the European Union. AbuBakr Bahaj, in charge of the Southampton research, said: The prospects for energy from tidal currents are far better than from wind because the flows of water are predictable and constant. The technology for dealing with the hostile saline environment under the sea has been developed in the North Sea oil industry and much is already known about turbine blade design, because of wind power and ship propellers. There are a few technical difficulties, but I believe in the next five to ten years we will be installing commercial marine turbine farms.’ Southampton has been awarded £215,000 over three years to develop the turbines and is working with Marine Current Turbines, a subsidiary of IT power, on the Lynmouth project. EU research has now identified 106 potential sites for tidal power, 80% round the coasts of Britain. The best sites are between islands or around heavily indented coasts where there are strong tidal currents.

D A marine turbine blade needs to be only one third of the size of a wind generator to produce three times as much power. The blades will be about 20 metres in diameter, so around 30 metres of water is required. Unlike wind power, there are unlikely to be environmental objections. Fish and other creatures are thought unlikely to be at risk from the relatively slow-turning blades. Each turbine will be mounted on a tower which will connect to the national power supply grid via underwater cables. The towers will stick out of the water and be lit, to warn shipping, and also be designed to be lifted out of the water for maintenance and to clean seaweed from the blades.

E Dr Bahaj has done most work on the Alderney site, where there are powerful currents. The single undersea turbine farm would produce far more power than needed for the Channel Islands and most would be fed into the French Grid and be re-imported into Britain via the cable under the Channel.

F One technical difficulty is cavitation, where low pressure behind a turning blade causes air bubbles. These can cause vibration and damage the blades of the turbines. Dr Bahaj said: ‘We have to test a number of blade types to avoid this happening or at least make sure it does not damage the turbines or reduce performance. Another slight concern is submerged debris floating into the blades. So far we do not know how much of a problem it might be. We will have to make the turbines robust because the sea is a hostile environment, but all the signs that we can do it are good.’

Questions 14-17

Reading Passage 2 has six paragraphs, A-F. Which paragraph contains the following information?

NB You may use any letter more than once.

14 the location of the first test site

15 a way of bringing the power produced on one site back into Britain

16 a reference to a previous attempt by Britain to find an alternative source of energy

17 mention of the possibility of applying technology from another industry

Questions 18-22

Choose FIVE Letters A-J

Which FIVE of the following claims about tidal power are made by the writer?

A It is a more reliable source of energy than wind power.

B It would replace all other forms of energy in Britain.

C Its introduction has come as a result of public pressure.

D It would cut down on air pollution.

E It could contribute to the closure of many existing power stations ln Britain.

F It could be a means of increasing national income.

G It could face a lot of resistance from other fuel industries.

H It could be sold more cheaply than any other type of fuel.

I It could compensate for the shortage of inland sites for energy production.

J It is best produced in the vicinity of coastlines with particular features.

Questions 23-26

Label the diagram below. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

An Undersea Turbine

Download All Cambridge IELTS Books Pdf + Audio For Free Cambridge 1-14 (Free Download)

Information Theory – The Big Idea

A In April 2002 an event took place which demonstrated one of the many applications of information theory. The space probe, Voyager I, launched in 1977, had sent back spectacular images of Jupiter and Saturn and then soared out of the Solar System on a one-way mission to the stars. After 25 years of exposure to the freezing temperatures of deep space, the probe was beginning to show its age. Sensors and circuits were on the brink of failing and NASA experts realised that they had to do something or lose contact with their probe forever. The solution was to get a message to Voyager I to instruct it to use spares to change the failing parts. With the probe 12 billion kilometres from Earth, this was not an easy task. By means of a radio dish belonging to NASA’s Deep Space Network, the message was sent out into the depths of space. Even travelling at the speed of light, it took over 11 hours to reach its target, far beyond the orbit of Pluto. Yet, incredibly, the little probe managed to hear the faint call from its home planet, and successfully made the switchover.

B It was the longest-distance repair job in history, and a triumph for the NASA engineers. But it also highlighted the astonishing power of the techniques developed by American communications engineer Claude Shannon, who had died just a year earlier. Born in 1916 in Petoskey, Michigan, Shannon showed an early talent for maths and for building gadgets, and made breakthroughs in the foundations of computer technology when still a student. While at Bell Laboratories, Shannon developed information theory, but shunned the resulting acclaim. In the 1940s, he single-handedly created an entire science of communication which has since inveigled its way into a host of applications, from DVDs to satellite communications to bar codes – any area, in short, where data has to be conveyed rapidly yet accurately.

C This all seems light years away from the down-to-earth uses Shannon originally had for his work, which began when he was a 22-year-old graduate engineering student at the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1939. He set out with an apparently simple aim: to pin down the precise meaning of the concept of ‘information’. The most basic form of information, Shannon argued, is whether something is true or false – which can be captured in the binary unit, or ‘bit’, of the form 1 or 0. Having identified this fundamental unit, Shannon set about defining otherwise vague ideas about information and how to transmit it from place to place. In the process he discovered something surprising: it is always possible to guarantee information will get through random interference – ‘noise’ – intact.

D Noise usually means unwanted sounds which interfere with genuine information. Information theory generalises this idea via theorems that capture the effects of noise with mathematical precision. In particular, Shannon showed that noise sets a limit on the rate at which information can pass along communication channels while remaining error-free. This rate depends on the relative strengths of the signal and noise travelling down the communication channel, and on its capacity (its ‘bandwidth’). The resulting limit, given in units of bits per second, is the absolute maximum rate of error-free communication given signal strength and noise level. The trick, Shannon showed, is to find ways of packaging up – ‘coding’ – information to cope with the ravages of noise, while staying within the information-carrying capacity – ‘bandwidth’ – of the communication system being used.

E Over the years scientists have devised many such coding methods, and they have proved crucial in many technological feats. The Voyager spacecraft transmitted data using codes which added one extra bit for every single bit of information; the result was an error rate of just one bit in 10,000 – and stunningly clear pictures of the planets. Other codes have become part of everyday life – such as the Universal Product Code, or bar code, which uses a simple error-detecting system that ensures supermarket check-out lasers can read the price even on, say, a crumpled bag of crisps. As recently as 1993, engineers made a major breakthrough by discovering so-called turbo codes – which come very close to Shannon’s ultimate limit for the maximum rate that data can be transmitted reliably, and now play a key role in the mobile videophone revolution.

F Shannon also laid the foundations of more efficient ways of storing information, by stripping out superfluous (‘redundant’) bits from data which contributed little real information. As mobile phone text messages like ‘I CN C U’ show, it is often possible to leave out a lot of data without losing much meaning. As with error correction, however, there’s a limit beyond which messages become too ambiguous. Shannon showed how to calculate this limit, opening the way to the design of compression methods that cram maximum information into the minimum space.

Questions 27-32

Reading Passage 3 has six paragraphs, A-F. Which paragraph contains the following information?

27 an explanation of the factors affecting the transmission of information

28 an example of how unnecessary information can be omitted

29 a reference to Shannon`s attitude to fame

30 details of a machine capable of interpreting incomplete information

31 a detailed account of an incident involving information theory

32 a reference to what Shannon initially intended to achieve in his research

Questions 33-37

Complete the notes below. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer

The Voyager l Space Probe

The probe transmitted pictures of both (33) ……………….,and ……………. , then left the (34) ……………. The freezing temperatures were found to have a negative effect on parts of the space probe. Scientists feared that both the (35)……………….. and ………………… were about to stop working. The only hope was to tell the probe to replace them with (36)…………………….. – but distance made communication with the probe difficult. A (37)………………….. was used to transmit the message at the speed of light. The message was picked up by the probe and the switchover took place.

Questions 38-40

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 3? In boxes 38-40 on your answer sheet write

TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

38. The concept of describing something as true or false was the starting point for Shannon in his attempts to send messages over distances.

39. The amount of information that can be sent in a given time period is determined with reference to the signal strength and noise level.

40. Products have now been developed which can convey more information than Shannon had anticipated as possible.

Show Answers

1. yes

2. no

3. yes

4. not given

5. yes

6. yes

7. no

8. yes

9. H

10. F

11. A

12. C

13. B

14. C

15. E

16. A

17. C

18. A

19. D

20. E

21. F

22. J

23. maintenance

24. slow (turning)

25. low pressure

26. cavitation

27. D

28. F

29. B

30. E

31. A

32. C

33. jupiter and saturn

34. solar system

35. sensors and circuits

36. spares

37. radio dish

38. true

39. true

40. false

Read the full article

#academicreading#c7t3#cambridge7#cambridgeacademicreading7#ielts7#ielts7reading3#ieltsacademicreading#reading

0 notes

Text

IELTS Practice Cambridge Book 7 Academic Reading Test 1 C7T1

Let’s Go Bats

A Bats have a problem: how to find their way around in the dark. They hunt at night, and cannot use light to help them find prey and avoid obstacles. You might say that this is a problem of their own making, one that they could avoid simply by changing their habits and hunting by day. But the daytime economy is already heavily exploited by other creatures such as birds. Given that there is a living to be made at night, and given that alternative daytime trades are thoroughly occupied, natural selection has favoured bats that make a go of the night-hunting trade. It is probable that the nocturnal trades go way back in the ancestry of all mammals. In the time when the dinosaurs dominated the daytime economy, our mammalian ancestors probably only managed to survive at all because they found ways of scraping a living at night. Only after the mysterious mass extinction of the dinosaurs about 65 million years ago were our ancestors able to emerge into the daylight in any substantial numbers.

B Bats have an engineering problem: how to find their way and find their prey in the absence of light. Bats are not the only creatures to face this difficulty today. Obviously the night-flying insects that they prey on must find their way about somehow. Deep-sea fish and whales have little or no light by day or by night. Fish and dolphins that live in extremely muddy water cannot see because, although there is light, it is obstructed and scattered by the dirt in the water. Plenty of other modern animals make their living in conditions where seeing is difficult or impossible.

C Given the questions of how to manoeuvre in the dark, what solutions might an engineer consider? The first one that might occur to him is to manufacture light, to use a lantern or a searchlight. Fireflies and some fish (usually with the help of bacteria) have the power to manufacture their own light, but the process seems to consume a large amount of energy. Fireflies use their light for attracting mates. This doesn’t require a prohibitive amount of energy: a male’s tiny pinprick of light can be seen by a female from some distance on a dark night, since her eyes are exposed directly to the light source itself. However using light to find one’s own way around requires vastly more energy, since the eyes have to detect the tiny fraction of the light that bounces off each part of the scene.

The light source must therefore be immensely brighter if it is to be used as a headlight to illuminate the path, than if it is to be used as a signal to others. In any event, whether or not the reason is the energy expense, it seems to be the case that, with the possible exception of some weird deep-sea fish, no animal apart from man uses manufactured light to find its way about.

D What else might the engineer think of? Well, blind humans sometimes seem to have an uncanny sense of obstacles in their path. It has been given the name ‘facial vision’, because blind people have reported that it feels a bit like the sense of touch, on the face. One report tells of a totally blind boy who could ride his tricycle at good speed round the block near his home, using facial vision. Experiments showed that, in fact, facial vision is nothing to do with touch or the front of the face, although the sensation may be referred to the front of the face, like the referred pain in a phantom limb. The sensation of facial vision, it turns out, really goes in through the ears. Blind people, without even being aware of the fact, are actually using echoes of their own footsteps and of other sounds, to sense the presence of obstacles. Before this was discovered, engineers had already built instruments to exploit the principle, for example to measure the depth of the sea under a ship. After this technique had been invented, it was only a matter of time before weapons designers adapted it for the detection of submarines. Both sides in the Second World War relied heavily on these devices, under such codenames as Asdic (British) and Sonar (American), as well as Radar (American) or RDF (British), which uses radio echoes rather than sound echoes.

E The Sonar and Radar pioneers didn’t know it then, but all the world now knows that bats, or rather natural selection working on bats, had perfected the system tens of millions of years earlier, and their radar achieves feats of detection and navigation that would strike an engineer dumb with admiration. It is technically incorrect to talk about bat ‘radar’, since they do not use radio waves. It is sonar but the underlying mathematical theories of radar and sonar are very similar and much of our scientific understanding of the details of what bats are doing has come from applying radar theory to them. The American zoologist Donald Griffin, who was largely responsible for the discovery of sonar in bats, coined the term ‘echolocation’ to cover both sonar and radar, whether used by animals or by human instruments.

Questions 1-5

Reading Passage 1 has five paragraphs, A-E. Which paragraph contains the following information?

Write the correct letter. A-E, in boxes 1-5 on your answer sheet. NB You may use any letter more than once.

1. Examples of wildlife other than bats which do not rely on vision to navigate by

2. How early mammals avoided dying out

3. Why bats hunt in the dark

4. How a particular discovery has helped our understanding of bats

5. Early military uses of echolocation

Questions 6-9

Complete the summary below. Choose ONE WORD ONLY from the passage for each answer.

Facial Vision

Blind people report that so-called ‘facial vision’ is comparable to the sensation of touch on the face. In fact, the sensation is more similar to the way in which pain from a (6)……………………arm or leg might be felt. The ability actually comes from perceiving (7)………..…………..through the ears. However, even before this was understood, the principle had been applied in the design of instruments which calculated the (8)……….…………..of the seabed. This was followed by a wartime application in devices for finding (9)………………

Questions 10-13

Complete the sentences below. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

10 Long before the invention of radar,…………… had resulted in a sophisticated radar-like system in bats.

11 Radar is an inaccurate term when referring to bats because………………are not used in their navigation system.

12 Radar and sonar are based on similar…………………….

13 The word ‘echolocation’ was first used by someone working as a………………….

Download All Cambridge IELTS Books Pdf + Audio For Free Cambridge 1-14 (Free Download)

Making Every Drop Count

A The history of human civilisation is entwined with the history of the ways we have learned to manipulate water resources. As towns gradually expanded, water was brought from increasingly remote sources, leading to sophisticated engineering efforts such as dams and aqueducts. At the height of the Roman Empire, nine major systems, with an innovative layout of pipes and well-built sewers, supplied the occupants of Rome with as much water per person as is provided in many parts of the industrial world today.

B During the industrial revolution and population explosion of the 19th and 20th centuries, the demand for water rose dramatically. Unprecedented construction of tens of thousands of monumental engineering projects designed to control floods, protect clean water supplies, and provide water for irrigation and hydropower brought great benefits to hundreds of millions of people. Food production has kept pace with soaring populations mainly because of the expansion of artificial irrigation systems that make possible the growth of 40 % of the world’s food. Nearly one fifth of all the electricity generated worldwide is produced by turbines spun by the power of falling water.

C Yet there is a dark side to this picture: despite our progress, half of the world’s population still suffers, with water services inferior to those available to the ancient Greeks and Romans. As the United Nations report on access to water reiterated in November 2001, more than one billion people lack access to clean drinking water; some two and a half billion do not have adequate sanitation services. Preventable water-related diseases kill an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 children every day, and the latest evidence suggests that we are falling behind in efforts to solve these problems.

D The consequences of our water policies extend beyond jeopardising human health. Tens of millions of people have been forced to move from their homes – often with little warning or compensation – to make way for the reservoirs behind dams. More than 20 % of all freshwater fish species are now threatened or endangered because dams and water withdrawals have destroyed the free-flowing river ecosystems where they thrive. Certain irrigation practices degrade soil quality and reduce agricultural productivity. Groundwater aquifers are being pumped down faster than they are naturally replenished in parts of India, China, the USA and elsewhere. And disputes over shared water resources have led to violence and continue to raise local, national and even international tensions.

E At the outset of the new millennium, however, the way resource planners think about water is beginning to change. The focus is slowly shifting back to the provision of basic human and environmental needs as top priority – ensuring ‘some for all,’ instead of ‘more for some’. Some water experts are now demanding that existing infrastructure be used in smarter ways rather than building new facilities, which is increasingly considered the option of last, not first, resort. This shift in philosophy has not been universally accepted, and it comes with strong opposition from some established water organisations. Nevertheless, it may be the only way to address successfully the pressing problems of providing everyone with clean water to drink, adequate water to grow food and a life free from preventable water-related illness.

F Fortunately – and unexpectedly – the demand for water is not rising as rapidly as some predicted. As a result, the pressure to build new water infrastructures has diminished over the past two decades. Although population, industrial output and economic productivity have continued to soar in developed nations, the rate at which people withdraw water from aquifers, rivers and lakes has slowed. And in a few parts of the world, demand has actually fallen.

G What explains this remarkable turn of events? Two factors: people have figured out how to use water more efficiently, and communities are rethinking their priorities for water use. Throughout the first three-quarters of the 20th century, the quantity of freshwater consumed per person doubled on average; in the USA, water withdrawals increased tenfold while the population quadrupled. But since 1980, the amount of water consumed per person has actually decreased, thanks to a range of new technologies that help to conserve water in homes and industry. In 1965, for instance, Japan used approximately 13 million gallons of water to produce $1 million of commercial output; by 1989 this had dropped to 3.5 million gallons (even accounting for inflation) – almost a quadrupling of water productivity. In the USA, water withdrawals have fallen by more than 20 % from their peak in 1980.

H On the other hand, dams, aqueducts and other kinds of infrastructure will still have to be built, particularly in developing countries where basic human needs have not been met. But such projects must be built to higher specifications and with more accountability to local people and their environment than in the past. And even in regions where new projects seem warranted, we must find ways to meet demands with fewer resources, respecting ecological criteria and to a smaller budget.

Questions 14-20

Reading Passage 2 has seven paragraphs, A-H. Choose the correct heading for paragraphs A and C-H from the list of headings below. Write the correct number, i-xi, in boxes 14-20 on your answer sheet.

List of Headings

i Scientists’ call for revision of policy

ii An explanation for reduced water use

iii How a global challenge was met

iv Irrigation systems fall into disuse

v Environmental effects

vi The financial cost of recent technological improvements

vii The relevance to health

viii Addressing the concern over increasing populations

ix A surprising downward trend in demand for water

x The need to raise standards

xi A description of ancient water supplies

14 Paragraph A

15 Paragraph C

16 Paragraph D

17 Paragraph E

18 Paragraph F

19 Paragraph G

20 Paragraph H

Questions 21-26

Do the following statements agree with information given in Reading Passage 2. In boxes 21-26 on your answer sheet, write

YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

21 Water use per person is higher in the industrial world than it was in Ancient Rome.

22 Feeding increasing populations is possible due primarily to improved irrigation systems.

23 Modern water systems imitate those of the ancient Greeks and Romans.

24 Industrial growth is increasing the overall demand for water.

25 Modern technologies have led to reduction in the domestic water consumption.

26 In the future, governments should maintain ownership of water infrastructures.

EDUCATING PSYCHE

Educating Psyche by Bernie Neville is a book which looks at radical new approaches to learning, describing the effects of emotion, imagination and the unconscious on learning. One theory discussed in the book is that proposed by George Lozanov, which focuses on the power of suggestion.

Lozanov’s instructional technique is based on the evidence that the connections made in the brain through unconscious processing (which he calls non-specific mental reactivity) are more durable than those made through conscious processing. Besides the laboratory evidence for this, we know from our experience that we often remember what we have perceived peripherally, long after we have forgotten what we set out to learn. If we think of a book we studied months or years ago, we will find it easier to recall peripheral details – the colour, the binding, the typeface, the table at the library where we sat while studying it – than the content on which we were concentrating. If we think of a lecture we listened to with great concentration, we will recall the lecturer’s appearance and mannerisms, our place in the auditorium, the failure of the air-conditioning, much more easily than the ideas we went to learn. Even if these peripheral details are a bit elusive, they come back readily in hypnosis or when we relive the event imaginatively, as in psychodrama. The details of the content of the lecture, on the other hand, seem to have gone forever.

This phenomenon can be partly attributed to the common counterproductive approach to study (making extreme efforts to memorise, tensing muscles, inducing fatigue), but it also simply reflects the way the brain functions. Lozanov therefore made indirect instruction (suggestion) central to his teaching system. In suggestopedia, as he called his method, consciousness is shifted away from the curriculum to focus on something peripheral. The curriculum then becomes peripheral and is dealt with by the reserve capacity of the brain.

The suggestopedic approach to foreign language learning provides a good illustration. In its most recent variant (1980), it consists of the reading of vocabulary and text while the class is listening to music. The first session is in two parts. In the first part, the music is classical (Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms) and the teacher reads the text slowly and solemnly, with attention to the dynamics of the music. The students follow the text in their books. This is followed by several minutes of silence. In the second part, they listen to baroque music (Bach, Corelli, Handel) while the teacher reads the text in a normal speaking voice. During this time they have their books closed. During the whole of this session, their attention is passive; they listen to the music but make no attempt to learn the material.

Beforehand, the students have been carefully prepared for the language learning experience. Through meeting with the staff and satisfied students they develop the expectation that learning will be easy and pleasant and that they will successfully learn several hundred words of the foreign language during the class. In a preliminary talk, the teacher introduces them to the material to be covered, but does not ‘teach’ it. Likewise, the students are instructed not to try to learn it during this introduction.

Some hours after the two-part session, there is a follow-up class at which the students are stimulated to recall the material presented. Once again the approach is indirect. The students do not focus their attention on trying to remember the vocabulary, but focus on using the language to communicate (e.g. through games or improvised dramatisations). Such methods are not unusual in language teaching. What is distinctive in the suggestopedic method is that they are devoted entirely to assist recall. The ‘learning’ of the material is assumed to be automatic and effortless, accomplished while listening to music. The teacher’s task is to assist the students to apply what they have learned paraconsciously, and in doing so to make it easily accessible to consciousness. Another difference from conventional teaching is the evidence that students can regularly learn 1000 new words of a foreign language during a suggestopedic session, as well as grammar and idiom.

Lozanov experimented with teaching by direct suggestion during sleep, hypnosis and trance states, but found such procedures unnecessary. Hypnosis, yoga, Silva mind-control, religious ceremonies and faith healing are all associated with successful suggestion, but none of their techniques seem to be essential to it. Such rituals may be seen as placebos. Lozanov acknowledges that the ritual surrounding suggestion in his own system is also a placebo, but maintains that without such a placebo people are unable or afraid to tap the reserve capacity of their brains. Like any placebo, it must be dispensed with authority to be effective. Just as a doctor calls on the full power of autocratic suggestion by insisting that the patient take precisely this white capsule precisely three times a day before meals, Lozanov is categoric in insisting that the suggestopedic session be conducted exactly in the manner designated, by trained and accredited suggestopedic teachers.

While suggestopedia has gained some notoriety through success in the teaching of modern languages, few teachers are able to emulate the spectacular results of Lozanov and his associates. We can, perhaps, attribute mediocre results to an inadequate placebo effect. The students have not developed the appropriate mind set. They are often not motivated to learn through this method. They do not have enough ‘faith’. They do not see it as ‘real teaching’, especially as it does not seem to involve the ‘work’ they have learned to believe is essential to learning.

Questions 27-30

Choose the correct letter A, B, C or D. Write the correct letter in boxes 27-30 on your answer sheet.

27 The book Educating Psyche is mainly concerned with

A the power of suggestion in learning

B a particular technique for leaning based on emotions

C the effects of emotion on the imagination and the unconscious

D ways of learning which are not traditional

28 Lozanov’s theory claims that, when we try to remember things,

A unimportant details are the easiest to recall

B concentrating hard produces the best results

C the most significant facts are most easily recalled

D peripheral vision is not important

29 In this passage, the author uses the examples of a book and a lecture to illustrate that

A both these are important for developing concentration

B his theory about methods of learning is valid

C reading is a better technique for learning than listening

D we can remember things more easily under hypnosis

30 Lozanov claims that teachers should train students to

A memorise details of the curriculum

B develop their own sets of indirect instructions

C think about something other than the curriculum content

D avoid overloading the capacity of the brain

Questions 31-36

Do the following statement agree with the information given in Reading Passage 3? In boxes 31-36 on your answer sheet, write:

TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

31 In the example of suggestopedic teaching in the fourth paragraph, the only variable that changes is the music.

32 Prior to the suggestopedia class, students are made aware that the language experience will be demanding.

33 In the follow-up class, the teaching activities are similar to those used in conventional classes.

34 As an indirect benefit, students notice improvements in their memory.

35 Teachers say they prefer suggestopedia to traditional approaches to language teaching.

36 Students in a suggestopedia class retain more new vocabulary than those in ordinary classes.

Questions 37-40

Complete the summary using the list of words, A-K, below. Write the correct letter A-K in boxes 37-40 on your answer sheet.

Sugestopedia uses a less direct method of suggestion than other techniques such as hypnosis. However, Lozanov admits that a certain amount of (37)……………… is necessary in order to convince students, even if this is just a (38)……………………. Furthermore, if the method is to succeed, teachers must follow a set procedure. Although Lozanov’s method has become quite (39)………………., the result of most other teachers using this method have been (40)……………………

Show Answers

1. B

2. A

3. A

4. E

5. D

6. phantom

7. echoes

8. depth

9. submarines

10. natural selection

11. radio waves

12. mathematical theories

13. zoologist

14. xi

15. vii

16. v

17. i

18. ix

19. ii

20. x

21. no

22. yes

23. not given

24. no

25. yes

26. not given

27. D

28. A

29. B

30. C

31. false

32. false

33. true

34. not given

35. not given

36. true

37. F

38. H

39. K

40. G

Read the full article

#academicreading#c7t1#cambridge7#cambridgeacademicreading7#ielts7#ielts7reading1#ieltsacademicreading#reading

0 notes

Text

IELTS Practice Cambridge 8 Academic Reading Test 1 C8T1

IELTS Practice Cambridge Book 8 Academic Reading Test 1 C8T1. Practice IELTS Reading practice online our website to score higher bands in your reading exam.

A Chronicle of Timekeeping

A According to archaeological evidence, at least 5,000 years ago, and long before the advent of the Roman Empire, the Babylonians began to measure time, introducing calendars to co-ordinate communal

https://www.ieltsxpress.com/ielts-practice-cambridge-book-8-academic-reading-test-1-c8t1/

Read the full article

#academicreading#c8t1#cambridge8#cambridgeacademicreading8#ielts8#ielts8reading1#ieltsacademicreading#reading

0 notes

Text

IELTS Practice Cambridge Book 7 Academic Reading Test 2 C7T2

IELTS Practice Cambridge Book 7 Academic Reading Test 2 C7T2

Why Pagodas Don’t Fall Down https://www.ieltsxpress.com/ielts-practice-cambridge-book-7-academic-reading-test-2-c7t2/

In a land swept by typhoons and shaken by earthquakes, how have Japan’s tallest and seemingly flimsiest old buildings – 500 or so wooden pagodas – remained standing for centuries? Records show that only two have collapsed during the past 1400 years. Those that have disappeared were destroyed by fire as a result of lightning or civil war. The disastrous Hanshin earthquake in 1995 killed 6,400 people, toppled elevated highways, flattened office blocks and devastated the port area of Kobe. Yet it left the magnificent five-storey pagoda at the Toji temple in nearby Kyoto unscathed, though it levelled a number of buildings in the neighbourhood.

Japanese scholars have been mystified for ages about why these tall, slender buildings are so stable. It was only thirty years ago that the building industry felt confident enough to erect office blocks of steel and reinforced concrete that had more than a dozen floors. With its special shock absorbers to dampen the effect of sudden sideways movements from an earthquake, the thirty-six-storey Kasumigaseki building in central Tokyo – Japan’s first skyscraper – was considered a masterpiece of modern engineering when it was built in 1968.

Yet in 826, with only pegs and wedges to keep his wooden structure upright, the master builder Kobodaishi had no hesitation in sending his majestic Toji pagoda soaring fifty-five metres into the sky – nearly half as high as the Kasumigaseki skyscraper built some eleven centuries later. Clearly, Japanese carpenters of the day knew a few tricks about allowing a building to sway and settle itself rather than fight nature’s forces. But what sort of tricks?

The multi-storey pagoda came to Japan from China in the sixth century. As in China, they were first introduced with Buddhism and were attached to important temples. The Chinese built their pagodas in brick or stone, with inner staircases, and used them in later centuries mainly as watchtowers. When the pagoda reached Japan, however, its architecture was freely adapted to local conditions – they were built less high, typically five rather than nine storeys, made mainly of wood and the staircase was dispensed with because the Japanese pagoda did not have any practical use but became more of an art object. Because of the typhoons that batter Japan in the summer, Japanese builders learned to extend the eaves of buildings further beyond the walls. This prevents rainwater gushing down the walls. Pagodas in China and Korea have nothing like the overhang that is found on pagodas in Japan. https://www.ieltsxpress.com/ielts-practice-cambridge-book-7-academic-reading-test-2-c7t2/

The roof of a Japanese temple building can be made to overhang the sides of the structure by fifty per cent or more of the building’s overall width. For the same reason, the builders of Japanese pagodas seem to have further increased their weight by choosing to cover these extended eaves not with the porcelain tiles of many Chinese pagodas but with much heavier earthenware tiles.

But this does not totally explain the great resilience of Japanese pagodas. Is the answer that, like a tall pine tree, the Japanese pagoda – with its massive trunk-like central pillar known as shinbashira – simply flexes and sways during a typhoon or earthquake? For centuries, many thought so. But the answer is not so simple because the startling thing is that the shinbashira actually carries no load at all. In fact, in some pagoda designs, it does not even rest on the ground, but is suspended from the top of the pagoda – hanging loosely down through the middle of the building. The weight of the building is supported entirely by twelve outer and four inner columns.

And what is the role of the shinbashira, the central pillar? The best way to understand the shinbashira’s role is to watch a video made by Shuzo Ishida, a structural engineer at Kyoto Institute of Technology. Mr Ishida, known to his students as ‘Professor Pagoda’ because of his passion to understand the pagoda, has built a series of models and tested them on a ‘shake- table’ in his laboratory. In short, the shinbashira was acting like an enormous stationary pendulum. The ancient craftsmen, apparently without the assistance of very advanced mathematics, seemed to grasp the principles that were, more than a thousand years later, applied in the construction of Japan’s first skyscraper. What those early craftsmen had found by trial and error was that under pressure a pagoda’s loose stack of floors could be made to slither to and fro independent of one another. Viewed from the side, the pagoda seemed to be doing a snake dance – with each consecutive floor moving in the opposite direction to its neighbours above and below. The shinbashira, running up through a hole in the centre of the building, constrained individual storeys from moving too far because, after moving a certain distance, they banged into it, transmitting energy away along the column.

Another strange feature of the Japanese pagoda is that, because the building tapers, with each successive floor plan being smaller than the one below, none of the vertical pillars that carry the weight of the building is connected to its corresponding pillar above. In other words, a five- storey pagoda contains not even one pillar that travels right up through the building to carry the structural loads from the top to the bottom. More surprising is the fact that the individual storeys of a Japanese pagoda, unlike their counterparts elsewhere, are not actually connected to each other. They are simply stacked one on top of another like a pile of hats. Interestingly, such a design would not be permitted under current Japanese building regulations.

And the extra-wide eaves? Think of them as a tightrope walker’s balancing pole. The bigger the mass at each end of the pole, the easier it is for the tightrope walker to maintain his or her balance. The same holds true for a pagoda. ‘With the eaves extending out on all sides like balancing poles,’ says Mr Ishida, ‘the building responds to even the most powerful jolt of an earthquake with a graceful swaying, never an abrupt shaking.’ Here again, Japanese master builders of a thousand years ago anticipated concepts of modern structural engineering.

Questions 1-4

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Reading Passage 1? In boxes 1-4 on your answer sheet, write

YES if the statement agrees with the claims of the writer

NO if the statement contradicts the claims of the writer

NOT GIVEN if there it impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

1 Only two Japanese pagodas have collapsed in 1400 years.

2 The Hanshin earthquake of 1995 destroyed the pagoda at the Toji temple.

3 The other buildings near the Toji pagoda had been built in the last 30 years.

4 The builders of pagodas knew how to absorb some of the power produced by severe weather conditions.

Questions 5-10

Classify the following as typical of

A both Chinese and Japanese pagodas

B only Chinese pagodas

C only Japanese pagodas

Write the correct letter, A, B or C, in boxes 5-10 on your answer sheet.

5 easy interior access to top

6 tiles on eaves

7 use as observation post

8 size of eaves up to half the width of the building

9 original religious purpose

10 floors fitting loosely over each other

Questions 11-13

Choose the correct letter, A, B or C. Write the correct letter in boxes11-13 on your answer sheet.

11 In a Japanese pagoda, the shinbashira

A bears the full weight of the building

B bends under pressure like a tree

C connects the floors with the foundations

D stops the floors moving too far

12 Shuzo Ishida performs experiments in order to

A improve skyscraper design

B be able to build new pagodas

C learn about the dynamics of pagodas

D understand ancient mathematics

13 The storeys of a Japanese pagoda are

A linked only by wood

B fastened only to the central pillar

C fitted loosely on top of each other

D joined by special weights

Cambridge IELTS Test 1 to 13

True Cost of Food

A For more than forty years the cost of food has been rising. It has now reached a point where a growing number of people believe that it is far too high, and that bringing it down will be one of the great challenges of the twenty first century. That cost, however, is not in immediate cash. In the West at least, most food is now far cheaper to buy in relative terms than it was in 1960.

The cost is in the collateral damage of the very methods of food production that have made the food cheaper: in the pollution of water, the enervation of soil, the destruction of wildlife, the harm to animal welfare and the threat to human health caused by modern industrial agriculture.

B First mechanisation, then mass use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides, then monocultures, then battery rearing of livestock, and now genetic engineering – the onward march of intensive farming has seemed unstoppable in the last half-century, as the yields of produce have soared. But the damage it has caused has been colossal. In Britain, for example, many of our best-loved farmland birds, such as the skylark, the grey partridge, the lapwing and the corn bunting, have vanished from huge stretches of countryside, as have even more wild flowers and insects. This is a direct result of the way we have produced our food in the last four decades. Thousands of miles of hedgerows, thousands of ponds, have disappeared from the landscape. The faecal filth of salmon farming has driven wild salmon from many of the sea lochs and rivers of Scotland. Natural soil fertility is dropping in many areas because of continuous industrial fertiliser and pesticide use, while the growth of algae is increasing in lakes because of the fertiliser run-off.

C Put it all together and it looks like a battlefield, but consumers rarely make the connection at the dinner table. That is mainly because the costs of all this damage are what economists refer to as externalities: they are outside the main transaction, which is for example producing and selling a field of wheat, and are borne directly by neither producers nor consumers. To many, the costs may not even appear to be financial at all, but merely aesthetic – a terrible shame, but nothing to do with money. And anyway they, as consumers of food, certainly aren’t paying for it, are they?

D But the costs to society can actually be quantified and, when added up, can amount to staggering sums. A remarkable exercise in doing this has been carried out by one of the world’s leading thinkers on the future of agriculture, Professor Jules Pretty, Director of the Centre for Environment and Society at the University of Essex. Professor Pretty and his colleagues calculated the externalities of British agriculture for one particular year. They added up the costs of repairing the damage it caused, and came up with a total figure of £2,343m. This is equivalent to £208 for every hectare of arable land and permanent pasture, almost as much again as the total government and EU spend on British farming in that year. And according to Professor Pretty, it was a conservative estimate.

E The costs included: £120m for removal of pesticides; £16m for removal of nitrates; £55m for removal of phosphates and soil; £23m for the removal of the bug Cryptosporidium from drinking water by water companies; £125m for damage to wildlife habitats, hedgerows and dry stone walls; £1,113m from emissions of gases likely to contribute to climate change; £106m from soil erosion and organic carbon losses; £169m from food poisoning; and £607m from cattle disease. Professor Pretty draws a simple but memorable conclusion from all this: our food bills are actually threefold. We are paying for our supposedly cheaper food in three separate ways: once over the counter, secondly through our taxes, which provide the enormous subsidies propping up modern intensive farming, and thirdly to clean up the mess that modern farming leaves behind.

F So can the true cost of food be brought down? Breaking away from industrial agriculture as the solution to hunger may be very hard for some countries, but in Britain, where the immediate need to supply food is less urgent, and the costs and the damage of intensive farming have been clearly seen, it may be more feasible. The government needs to create sustainable, competitive and diverse farming and food sectors, which will contribute to a thriving and sustainable rural economy, and advance environmental, economic, health, and animal welfare goals.

G But if industrial agriculture is to be replaced, what is a viable alternative? Professor Pretty feels that organic farming would be too big a jump in thinking and in practices for many farmers. Furthermore, the price premium would put the produce out of reach of many poorer consumers. He is recommending the immediate introduction of a ‘Greener Food Standard’, which would push the market towards more sustainable environmental practices than the current norm, while not requiring the full commitment to organic production. Such a standard would comprise agreed practices for different kinds of farming, covering agrochemical use, soil health, land management, water and energy use, food safety and animal health. It could go a long way, he says, to shifting consumers as well as farmers towards a more sustainable system of agriculture.

Questions 14-17

Reading Passage 2 has seven paragraphs, A-G. Which paragraph contains the following information?

Write the correct letter, A-G, in boxes 14-17 on your answer sheet. NB You may use any letter more than once.

14 a cost involved in purifying domestic water

15 the stages in the development of the farming industry

16 the term used to describe hidden costs

17 one effect of chemicals on water sources

Questions 18-21

Do the following statements agree with the claims of the writer in Reading Passage 2? In boxes 18-21 on your answer sheet, write