#in her artistic pursuits but he gave her all the credit and praise for everything.

Text

It seems hard to me when I look at her sometimes, and think how many without one tithe of her genius or greatness of spirit have granted them abundant health and opportunity to labour through the little they can do or will do, while perhaps her soul is never to bloom nor her bright hair to fade, but after hardly escaping from degradation and corruption, all she might have been must sink out again unprofitably in that dark house where she was born. How truly she may say, 'No man may care for my soul.' I do not mean to make myself an exception, for how long I have known her, and not thought of this till so late—perhaps too late. But it is no use writing more about this subject; and I fear, too, my writing at all about it must prevent your easily believing it to be, as it is, by far the nearest thing to my own heart.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti writing of Lizzie Siddal's health in a letter dated 23 July, 1854

#european date orientation even tho it feels unnatural to my american brain#quotes#pre raphaelite#dante gabriel rossetti#rossetti#lizzie siddal#elizabeth siddal#elizabeth eleanor siddall#he really did admire her. not just the vague and vain concept of 'love' but he truly respected and appreciated her.#as much as a young victorian man could anyway......#this book by jan marsh is so insightful. it's truly flipping a lot of my expectations and previous assumptions#i didn't realize how deeply he cared for her in all the years they were just courting. ppl made it sound like he encouraged her only a bit#in her artistic pursuits but he gave her all the credit and praise for everything.#lizzie could make one stroke on a canvas and he'd start crying#i think ppl confuse his later lurid affairs as a widower w him being a playboy in his 20s. which doesn't appear to be the case.#i remember reading somewhere years ago that there was no evidence he committed adultery in their (albeit short) marriage but ppl assume#based on what they know about him. but he and lizzie were still very young when she died and he was much more bright-eyed and bushytailed#it seems in her very early adulthood.#didn't yeats also lose his virginity when he was like 40??? and he of course got around w a lot of women once he did.#ppl always make assumptions of what historical figures must've been like based on their modern assumptions of how ppl behave#jan marsh is smashing my entire schema of dgr as a young man and im kinda here for it#the girlies are gagging for guggums

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

On first encounters with adult Moomins

Part IV: The Snork

Snork Maiden was the first to tell her brother about Moomintroll and Snufkin leaving for the South together the previous Fall. She told Snork everything that Moominmama had said to her and asked if she could hibernate at his home instead of Moominhouse. She explained that it would be too painful for her to be that close to Moomintroll's family until she had a chance to ask for his and Snufkin's forgiveness in the Spring. Snork was completely floored by the implications of what she told him.

Snork had spent his life in pursuit of scientific knowledge. That he had missed all of the signs of how Moomintroll and Snufkin felt for each other for years bothered him. He prided himself on being impartial, rational and observant, but when it came to other's emotions he had to admit that he had a huge blind spot. Perhaps it was his upbringing. His parents were cold, unfeeling, and only interested in practical results from their children. They were also nobility and determined to protect their image and standing in society from any hint of scandal, so they had tried to pass all of their prejudices on to him. Had they been more successful than Snork wanted to admit?

No; that wasn't it. He had risen up through academic circles like a meteor through his staggering intellect not just because it suited his nature, but because he wanted to rescue Snork Maiden from their parents. She was their opposite in every way; imaginative, open-minded, artistic, sensitive, sentimental, and caring. She would have withered under their direct attention, so he bore the burden of tolerating all of their intolerance instead of her until he could make his own way in the world and find a place where both him and his sister could live out their dreams in peace and happiness.

Winning his first patent for his Personal Amphibious Vehicle gave Snork the money he needed to move himself and Snork Maiden to Moominvalley for good. His family had always thought of the tiny village as a vacation spot, but Snork knew it would be the perfect refuge for the two of them. He claimed his family's vacation home as their own and vowed never to see his parents again. He had wanted nothing to do with their twisted views.

When Snork Maiden and Moomintroll had fallen in love at first sight, Snork had pinned all of his hopes for her future on the two of them marrying when they were old enough. The thought that Moomintroll could also love someone else just as much, especially Snufkin, was one that he hadn't allowed to enter his head. He thought Snork Maiden might lose her chance at happiness. He thought that Moomintroll should only choose his sister. Admitting he was wrong wasn't going to be easy.

When Snork Maiden left their house on the first day of Spring, she had told him all about her intention to build a new kind of family with Moomintroll and Snufkin. He hadn't had the courage to say anything, even to wish her well. It was all too much to take in. As lunchtime approached, Snork decided he had to face everything head on and give his blessing to the three of them, so he headed for Moominhouse, filled with determination. The last person he expected to meet on the way and to change his plans was Sniff.

Sniff ran into Snork right in front of Moomintroll and Snufkin's tents. Sniff started raving about how everyone in the Moomin family had been changed somehow and that no one in the world really wanted him around anymore. Sniff was completely incoherent with fear and sadness and was weeping uncontrollably. What was worse, he was literally fading right before Snork's eyes! Sniff's fur went from brown to dull gray, then his whole body slowly became more and more transparent!

"Stop it, Sniff!", said Snork, "You're turning yourself invisible! Hold on to my paws, and I'll take you back to my house! I'll find a way to help you, I swear! Just don't let go of me, whatever you do!"

Snork's show of compassion kept Sniff just visible enough for Snork to get him to the spare room in his home safely. Snork ran to his laboratory and got his spare lab coat for Sniff. By the time he returned to Sniff, Sniff had become totally invisible! Snork quickly put the lab coat on Sniff. It was most alarming to see a lab coat seemingly floating in midair on its own, but it was all Snork could think to do at the moment to be able to keep from losing track of Sniff. Snork couldn't think of a single test he could try, a single chemical formula he could use to help Sniff. There was only one person he could think of who could possibly help Sniff now; Moominmama.

Snork headed back to Moominhouse at top speed after strictly instructing Sniff to stay in the guest room and promising him that he was going to find a cure no matter what. As Snork approached Moominhouse's front door, he quickly collected himself and tried to appear as calm as possible. He entered the parlor to find Snufkin, Moomintroll, and his sister holding paws on the love seat and Moominpapa and Moominmama seated at the parlor table, beaming happily at the three of them. Moominmama immediately turned to Snork.

"Oh! Snork!", she said, "You wouldn't have happened to run into Sniff on your way here, would you? He left very suddenly earlier, and we're just a little worried about him."

Snork knew that he was a terrible liar, so the best that he could manage was to leave the worst of the details out of his explanation so that he could spare everyone's feelings and prevent them from making Sniff's condition worse: "Actually, I did. He was in a panic and wasn't making any sense, so I took him back to my house to look after him. I came here to tell you that he's alright. However, it would be better if he didn't have any visitors for a while. He's worked himself into quite a state and he needs a lot of time before he'll be able to see everything the right way. This isn't anyone's fault, so there's no reason for anyone to feel guilty or blame themselves. I just need all of you to be patient and trust me to look after Sniff on my own for the time being. With any luck, he'll be completely better before the Summer is over."

Snork's response was so reasonable and calm that it reassured everyone for the most part, but it did put an end to the party. Snork congratulated his sister and Moomintroll and Snufkin on their new family and gave Snork Maiden his blessing to move into Moominhouse permanently. Snufkin and Moomintroll headed back to their tents and Snork Maiden went up to Moomintroll's old room a little reluctantly, but they were all exhausted after a very exciting day, so it wasn't all that hard for Snork and Moominmama to talk them into going to bed. Snork was then left alone with Moominmama and Moominpapa.

As Snork helped the two of them clean up the dining room and do the dishes, he explained about Sniff having turned himself invisible and he asked Moominmama for her invisibility cure recipe and thanked her for helping to keep the new family calm.

"The potion does help, but not in the way that you think.", explained Moominmama, "It gives the patient the sense that they're doing something concrete to help themselves and reassures them that the person who made it for them really does care. That's the really important part; that you keep showing Sniff how much you care. That's the real cure. You don't give yourself nearly enough credit for how compassionate and caring you are. I have complete faith in you. You will bring Sniff back to us, I know it!"

Snork took Moominmama's words to heart, and as he returned home, he thought carefully about all the things that he knew brought out the best in Sniff. Sniff liked tangible rewards and the hope of riches. Like his father, The Muddler, he liked shiny buttons and any other kind of small, collectible junk. Snork had always been astonished at the good results Sniff would happily deliver if he was promised a little reward that he could hold in his paws and admire. He had always enjoyed the games he had learned as a child and had never stopped playing them. Snork was going to have to appeal to all of these things that brought Sniff happiness every day in order to help him become visible again.

When he returned home, Snork made Sniff a simple offer; a place to stay, a warm bed, good food, play times together, and a piece of eight each week plus all the random small parts he could pick up from Snork's workshop floor in exchange for doing all of the housework and cooking and helping out in the workshop every day. Sniff responded more enthusiastically and effectively than Snork had hoped. Getting used to playing games and remembering to constantly praise and comfort Sniff also came more quickly to Snork than he had expected. Within a month, Sniff was completely visible again and Snork had gained a real sense of affection for and commitment to Sniff. Snork was pleasantly surprised to learn that Sniff had come to feel the same way about him. Both of them decided that they were willing to find out what these feelings meant together and at their own pace. They just knew that their new life felt really good and that they both wanted this new way of living.

The End

#moomin fanfiction#moomin#moomintroll#moominmama#moominpapa#moominvalley#snufkin#snufmin#snork maiden#sniff#the snork

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Once Upon A Time In... Hollywood review

(Contains spoilers !!!)

Once Upon A Time In Hollywood proves Tarantino is the ultimate artist.

When a film can be successfully marketed merely as a sequential product of a certain director, that’s when you know it has to be something. The ninth edition to the Tarantino’s repertoire reinforces his status as a one-of-a-kind, visionary filmmaker whose work exudes style, taste and true passion. This period piece combines history, dreams and, in a familiar Tarantino fashion, bursts of violence, to present a tale that intrigues and surprises, and ultimately lands with a bang!

Films that Tarantino brings to life seem to carry a certain energy, each unique and alive with heart. Now, me saying this while not having seen every single picture in his body of works might seem silly and diminishing of the power of this statement, yet no one can deny that Tarantino is all about the vision. A writer/director credit affirms that with this film, as Once Upon A Time In Hollywood arrives from a long time in the making, and from careful crafting that appears to have been approached with the utmost thought and dedication. It’s fitting, knowing that Hollywood for him hits close to home, as, well, it is exactly that. The vibrant locations and the scenery of 1969’s Los Angeles are visually as appealing and enticing as it gets, and I especially loved the use of rich and saturated colours, almost as if mirroring the culture of the ‘Golden Age of Hollywood’, to which this film heavily reverts to. Indeed, the western-style action, the old-school culture of the film landscape of the time is entrenched in the way characters act and behave, as well as the environments they appear in. And while many keep saying that this is how Tarantino creates his stories and builds his films’ worlds - by taking from already existing material, trialed elements and using them to serve his story, well, not everyone can even do that successfully. Besides, clichés are often over-exaggerated yet accurate representations. And if anything, referencing something in your own creative pursuits is a way to recognise and give credit. At least he definitely puts his own stamp on. It’s evident in this new instalment too. The film does rely on the ideas already laid out by the Old Hollywood format but Tarantino ultimately shines a new light on how narrative and characters can come together.

With that in mind, this story is a refreshing account of fiction-meets-reality. The general premise envisions two friends working in the entertainment business during the 60’s, a struggling actor Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio) and his stunt double Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt), as they figure out how to stay relevant and keep themselves afloat. These are fleshed out characters, and their buddy relationship radiates an energy that instantly draws you in to root for them, which is all due to the stellar performances by both DiCaprio and Pitt. Tarantino has hit the nail on the head with this casting, that’s for sure. However, these characters serve more as storytelling devices, than fully realised people. Here, they are being used as models to set the scene, move the story forward. As a result, a good chunk of the movie, about two thirds of the almost three hour long film, is of expositional purpose mainly to build tension for the grand finale. And while it’s understandable why Tarantino felt the need to lay out the ground work so meticulously, some scenes just fell flat or felt unnecessary. (I caught myself fixating on anything other than the screen, like how uncomfortable the chair was, quite a few times.) Throughout and in between those slow sequences, flashes of another character - Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie), a real life person in actuality - reignite that eagerness to see how it all plays out. And by it, I mean, of course, the infamous murders of Tate and 4 other individuals inflicted on them by the Manson family in 1969. It all crashes down in the absurdly violent way by which Rick and Cliff become heroes of an alternate reality by mercilessly slaying the known accomplices. Tarantino really doesn’t hold off in showing them no remorse, and by this time the audience is fascinated and amused by this turn of events. Rightfully so, many have praised the way fantasy and imagination is used here to attempt to mediate the harsh reality it takes from and also to subvert expectations in such a daring way. A flamethrower, or a tin-can to the face to counteract the aggressors did have quite an uproar from the crowd. However, there might be some truth to others saying that the boastful need for violence for the sake of humour or satisfaction is an inconsiderate approach of such a sensitive topic. But Tarantino deliberately accentuating the violence, knowing that the audience, the ones dreadfully awaiting for what’s to come, might be shocked and relieved at the reversal, is an ability to really understand what works on a screen and what doesn’t. And all those small, almost forgotten glimpses of Tate being excited about her growing family and rising career, unaware of her terrible fate, still full of life and joy inside of her (which was the baby she was carrying) felt both sad and mournful of what should have been, and honouring and respectful enough by not being sensationalised.

In full, the film tries to balance a longing memory of the glorified haze of Hollywood attraction, depicting history and faces in a secure and safe perspective, and a shockingly horrifying reality replaced by a fairytale resolution. The scenes revolving around Rick and Cliff are about everything and anything comedy-drama style, and actually feel profound yet, unfortunately, sometimes short-lived. Margot Robbie, for what we see of her, plays Tate with a genuine, heartfelt and warm regard. Intertwining an imagined storyline with a familiar truth gave the film a unique duality which Tarantino’s vibrancy and sharp taste made into a riveting portrayal. Whatever backlash this movie received is a testament to how a bold and unwavering creative vision should be used. Once Upon A Time In Hollywood proves Tarantino is the ultimate artist because without vision, inspiration and complete belief in this project, it probably wouldn’t have even happened. Oh and also, Al Pacino is in this movie. What do you know!

#once upon a time in hollywood#quentin tarantino#leonardo dicaprio#brad pitt#margot robbie#al pacino#film review#film critique#cinema#movies#august 2019 release

1 note

·

View note

Photo

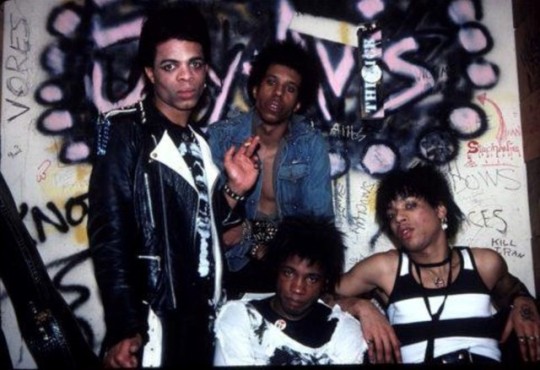

The forgotten story of Pure Hell, America’s first black punk band

The four-piece lived with the New York Dolls and played with Sid Vicious, but they’ve been largely written out of cultural history

An essential part of learning history is questioning it, asking what has become part of our cultural memory and what might have been left out. When it comes to the history of punk music, there are few bands who have been as overlooked as Pure Hell.

The band’s story began in West Philadelphia in 1974, when four teenagers – lead vocalist Kenny ‘Stinker’ Gordon, bassist Lenny ‘Steel’ Boles, guitarist Preston ‘Chip Wreck’ Morris and drummer Michael ‘Spider’ Sanders, set out to follow in the footsteps of their musical idols. A shared obsession with the sounds of Iggy, Bowie, Cooper, and Hendrix inspired them to create music that was louder, faster and more provocative than even those artists’ most experimental records. Pure Hell’s unique sound led them to New York, where they became characters in a seminal subculture recognised today as punk. As musicians of colour, their contribution to a predominately white underground scene is all the more significant. “We were the first black punk band in the world,” says Boles. “We were the ones who paid the dues for it, we broke the doors down. We were genuinely the first. And we still get no credit for it.”

The title of the ‘first black punk band’ has, in recent years, been informally given to Detroit-based Death, whose music was mostly unheralded at the time but has since been rediscovered and praised for its progressive ideas. But while Death were creating proto-punk music in isolation in the early 1970s, Pure Hell was completely entrenched in the New York City underground scene, living and performing alongside the legends of American punk. Arriving the same month that Patti Smith and Television began their two-month residencies at CBGB and leaving just after Nancy Spungen’s murder, Pure Hell’s active years in the city aligned perfectly with the birth and death of a dynamic chapter of music history. “I don’t want to be remembered just because we were black,” says Kenny Gordon. “I want to be remembered for being a part of the first tier of punk in the 70s.”

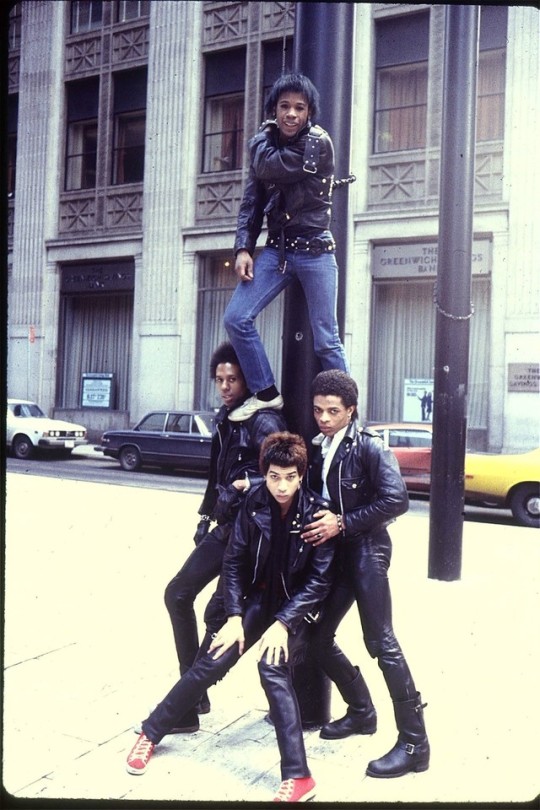

Being just 155km from Greenwich Village, Philadelphia was somewhat of a pipeline of New York subculture – Gordon remembers his teenage years at the movie theatre watching John Waters films like Polyester and Pink Flamingos, and hanging out at Artemis, a spot frequented by Philly scenesters like Nancy Spungen and Neon Leon. “I heard (The Rolling Stones’) ‘Satisfaction’ and knew it was the kind of music I wanted to play,” recalls bassist Lenny Boles. “I was too poor to afford instruments, so if someone had one, I would befriend them.”

The quad quickly gained notoriety on their home turf. “Growing up in West Philadelphia, which was all black, we were some of the craziest guys you could have possibly seen walking the streets back then,” says Gordon. “We dressed in drag and wore wigs, basically daring people to bother us. People in the neighbourhood would say, ‘Don’t go into houses with those guys, you may not come out!’”

Pure Hell swan dove into the New York underground scene in 1975, in pursuit of the people, places, and sounds they’d read about for years in the pages of Rock Scene and Cream magazine. The band moved into the Chelsea Hotel, the temporary home of a long list of influential characters, including Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Edie Sedgwick, Patti Smith, and Robert Mapplethorpe. Their first gig in the city was hosted at Frenzy’s thrift, a storefront on St. Marks place, where guitarist Preston Morris “rather memorably caught the amplifier on fire due to a combination of maximum volume and faulty wires”, says Gordon. Drummer Michael Sanders’ friendship with Neon Leon led the band to the New York Dolls, who were acting as mentors for younger artists like Debbie Harry and Richard Hell at the time. Pure Hell was soon invited to perform for the Dolls in their loft.

“Honestly, we were scared to death of them,” Boles says. “When we walked in, they were all dressed up, smoking joints and watching The Untouchables on TV. Fortunately, we played and blew them away.” Gordon adds: “Underneath their outer appearance, they were just a bunch of guys from Queens. We had the same lingo. We were both really street and really genuine. It’s like, they were white but playing black, and we were just the opposite. We were innovative and they definitely appreciated us for it.”

After being kicked out of the Chelsea for not paying rent, Pure Hell moved into the Dolls’ loft. “Everybody hated us at first. We had a bad reputation because of our association with the New York Dolls, who were doing a lot of dope at the time,” says Boles. “The way we looked, everybody thought we were in a gang. Actually, we used to live in gang territory in West Philly, and people were always trying to get us to join. We never did. And with a name like Pure Hell, people thought we were devil worshippers.”

Gordon adds: “This was New York City, this was punk. People don’t realise it was ruthlessly competitive. It was dog eat dog.” Although they felt that few people were on their side, their kinship with Johnny Thunders led to numerous gigs at Andy Warhol’s haunt, Max’s Kansas City, and Mother’s, a Chelsea gay bar turned punk club, where Blondie first performed. The band was featured in a number of publications, namely Warhol’s own Interview magazine, marking their ‘place’ in a scene cultural influencers.

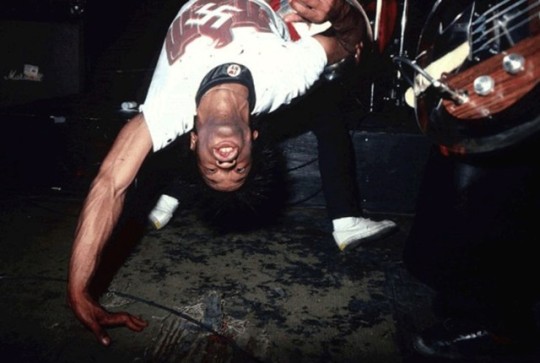

Despite their growing presence in the underground, Pure Hell still didn’t have a manager. After reading a biography of Jimi Hendrix by Curtis Knight, the singer and frontman of Hendrix’s first band The Squires, Lenny Boles chased down the author’s address and arrived on his doorstep. Boles’ bold act of promotion earned them management from the man credited with Hendrix’s discovery. Kathy Knight, Curtis’s then-partner in life and business, recalls her ex-husband’s first impressions of Pure Hell. “He loved them immediately,” she says. “After Lenny knocked on the door, Curtis brought me to one of the clubs where they were performing on Bleecker Street. Stinker (Kenny Gordon) almost landed in my lap when he did a backflip off the stage. We were so blown away that we put everything we had into them at the time.”

Those who saw Pure Hell in action describe their shows similarly. Gordon’s background in gymnastics gave them an unparalleled stage presence, with choreography that he says he performed “crash dummy style”. Pure Hell’s sound was harsher than their peers and predecessors and is today recognised as proto-hardcore. “We were like four Jimi Hendrixes, and Curtis knew it,” Gordon says. “We aimed for impact, just because we could. A lot of people at the time couldn’t play like Chip, doing Hennessy licks and everything. Not everyone could copy that.”

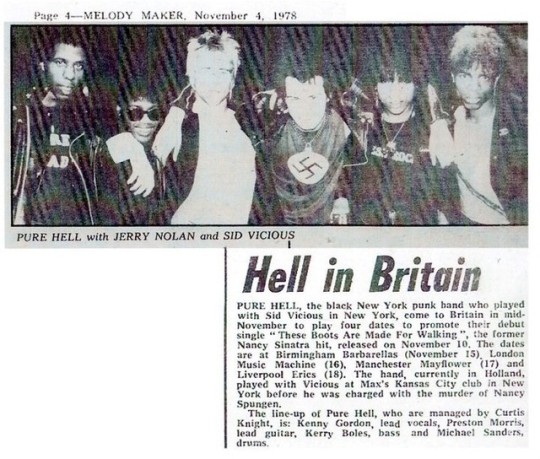

Curtis and Kathy Knight were so enthusiastic about Pure Hell that they sacrificed three months of rent money for studio sessions. Knight organised Pure Hell’s first European tour in 1978, which resulted in their single “These Boots are Made for Walking” reaching number four in the UK alternative charts. Later, they opened for Sid Vicious at Max’s during his New York residency. It would end up being his last public appearance, and Pure Hell found themselves looped into the media circus surrounding Nancy Spungen’s death. “We were on the second page of the majority of the tabloids, like New Musical Express, Sounds,and Melody Maker,” says Gordon.

But beyond their association with Vicious, Pure Hell’s European tour was a major success in part due to Curtis Knight’s strategic marketing campaign, which sensationalised their race. After arriving, Knight created a big poster with an image of the band taken by legendary rock photographer Bob Gruen in front of Buckingham Palace with the slogan: “From the United States of America, the world’s only black punk band”. Boles was angry at the time. “I said to Curtis, ‘Why do you have to call us a black band?’ Of course, that’s what we were, but we really didn’t think in those terms at the time. People in Europe were curious about the band before we even arrived. They were looking at it like a novelty. They didn’t believe we really existed.”

Boles says the band was “plastered by this campaign”, but were able to reap its fruits while touring Holland and the UK. Landing smack dab in the middle of the London punk scene, Pure Hell were welcomed by a parallel movement that had clearer political convictions and more dynamic cross-cultural discourse. “All the punks listened to reggae,” says Boles. “It was about all rebel music.” Gordon adds that “people, incorrectly, view punk as this angry, white, urban, male genre. Black culture is really the source of punk, and a lot of people don’t recognise it – or don’t want to recognise it.”

Although they eventually felt accepted in New York, and even celebrated in Europe, the legacy of Jim Crow still haunted the industry, where genres remained segregated. “We experienced racism, but didn’t know it at the time,” says Lenny Boles. “We were watching all of these bands around us, with far less talent, get signed. It had us second guessing ourselves, thinking we weren’t good enough. Obviously we were. It was a while before we realised we were getting snubbed.” While their white peers were being cut cheques, Pure Hell found themselves courted by a number of record labels, all of whom insisted they change their music in order to align with racial stereotypes. “Everybody was trying to make us do this Motown thing, saying like, ‘You guys are black so you’ve gotta do something that’s danceable,’” Boles adds. “They kept trying to make us more ‘funky’. Everything we liked had nothing to do with dance music. We were not having it. So we opted not to get signed.”

Integrity and profitability don’t often go hand-in-hand, and Pure Hell’s refusal to comply with the industry’s limitations meant they sacrificed career opportunities. After a second European tour in 1979, the band suffered a fall-out with Knight. A messy legal conflict resulted in Knight flying back to the US alone, with the band’s master tapes in tow. Pure Hell remained in Europe without any of the rights, or access, to their recordings, which Kathy Knight salvaged after her husband attempted to destroy them.

Pure Hell eventually finagled their way back to the US, where they settled in Los Angeles. Although they played historic bills at the Masque (LA’s equivalent to CBGB) with iconic groups like the Germs, the Cramps, and the Dead Boys, Pure Hell lost their momentum. With no management, no record deal, and no access to their recorded output, the band felt the flames of Pure Hell die out. “It was all totally over by 1980,” says Kenny Gordon. “Really, punk died with Nancy’s murder. Everyone was burning the candle from both ends. You had to be extreme to be in those kinds of circles.” Bad Brains’ explosion onto the music scene in the early 80s also left Pure Hell feeling robbed of their title of ‘the first black punk band’. “You know, we took the blow for being black, so why didn’t they give it to us in the end?” Boles asks.

As decades passed and history books were written, Pure Hell’s memory faded to legend. But in the early 2000s, Kathy Knight fatefully decided to auction off Pure Hell’s master tapes on eBay. Their unreleased album Noise Addiction was purchased by an enthusiastic Mike Schneider of Welfare Records. “Mike wanted them so badly he came himself to pick them up,” Knight recalls. Pure Hell’s legacy has also been promoted and protected by hardcore legend Henry Rollins of Black Flag, who tracked down the original acetate of the band’s first single and reissued it on his label 2.13.61, in collaboration with In the Red Records, last year. Rollins first learned of the band’s existence in 1979, after seeing their single at Yesterday & Today Records in Rockville, Maryland, with his friend Ian MacKaye of Minor Threat and Fugazi. He remained on the lookout for traces of the band for over 30 years.

“At auction time, I was able to secure the record,” Rollins says. “I listened to it and was amazed at how good it sounded. I checked in with Kenny (Gordon) and he confirmed it was the only source for the two songs.” Beyond simply highlighting and celebrating the rare black punk bands of the time, Pure Hell held particular significance to Rollins because their urban myth was real. “The rumour was that they had made an album and that it was sitting in a closet,” he says. “Noise Addiction, released in 2006, decades after it had been recorded, is really great. If the album had come out when they made it, that would have been a game changer. I believe (it) would have had a tremendous impact. It’s one of those missed opportunity stories.”

In addition to Rollins, indie talent rep Gina Parker-Lawton ranks as one of Pure Hell’s greatest advocates. Parker-Lawton met drummer Michael Sanders on Sunset Boulevard in the 80s, and counted him as a friend during their overlapping years in LA. It was after she learned of Sanders’ death in 2003 that Parker-Lawton made contact with the other band members and became their publicist. “They were just kind of overlooked in all of the punk history books,” she says. “After learning their story and what they had actually accomplished, by being the first truly all-black punk band, I wanted to ensure they were remembered.” Parker-Lawton has since been advocating for their deserved place in music history, and recently helped secure their induction into the Smithsonian African American Museum of History and Culture. Their induction will be marked by the donation of Sanders’ leather jacket, which he wore on tour in Europe and around LA.

Pure Hell’s story beckons essential questions about the integrity of our cultural memory, reminding us that “history” is written within the constructs of unjust society. “It’s just so important to me that history be correct,” says Parker-Lawton. “Taking the risks that they took, daring to be so different, they were outlaws and true pioneers. When people are that true to their art and that brave, it has to be recognised.” Although their musical careers didn’t necessarily bring wealth or fame, Boles and Gordon describe their years in Pure Hell as paramount. “I had so much fun, it doesn’t matter that I never saw a penny for it,” he says. “For us, it wasn’t about making money. It was about following our hearts and doing exactly what we wanted to do.”

Images:

Pure Hell courtesy of Pure Hell

Pure Hell courtesy of Pure Hell

Pure Hell with Sid Vicious in Melody Maker magazine. Early punk artists often flirted with Nazi symbolism for shock value.

Pure Hell live at Max’s Kansas City

Pure Hell courtesy of Pure Hell

#pure hell#black punk band#black punk bands#punk band#punk bands#rock music#black rock music#music#black music#dazed magazine#interview#Interviews#punk rock#black punk rock

4 notes

·

View notes