#internment camp

Text

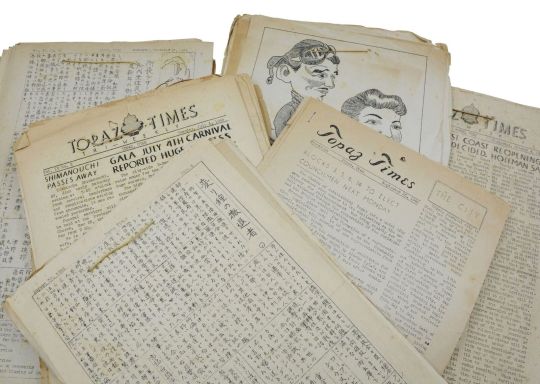

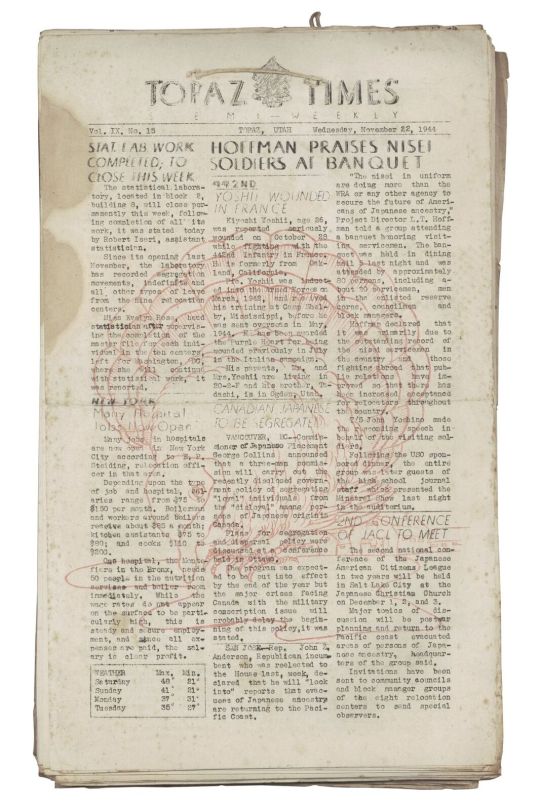

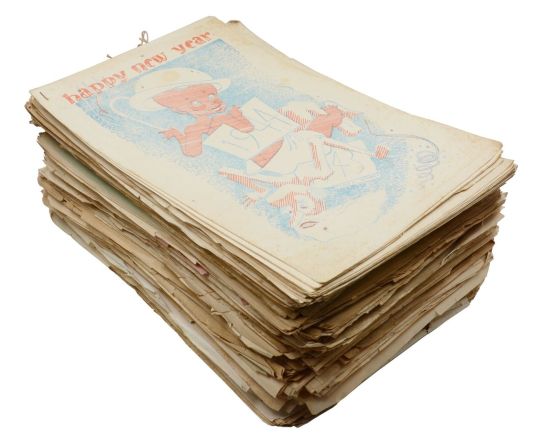

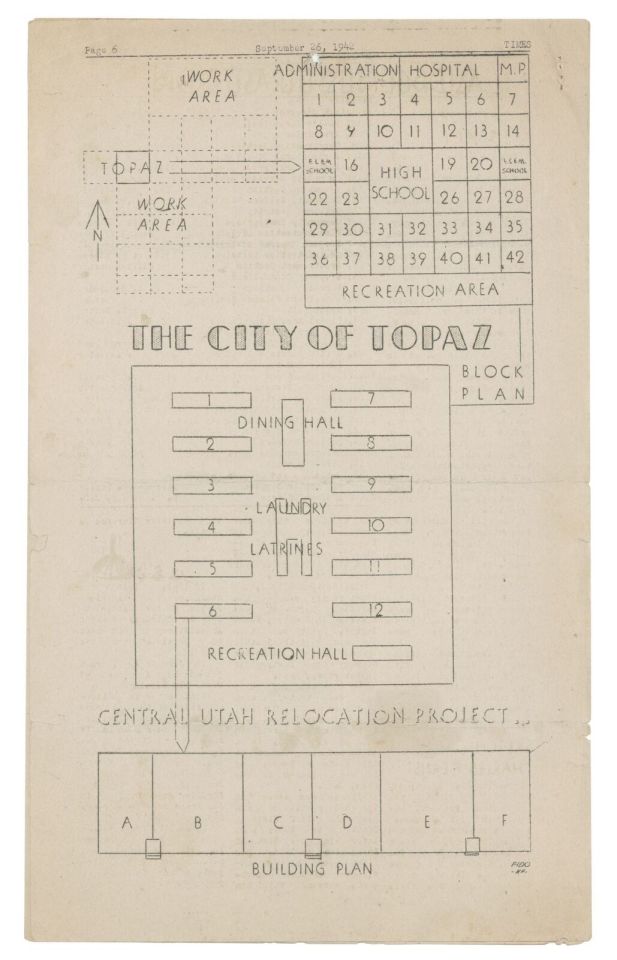

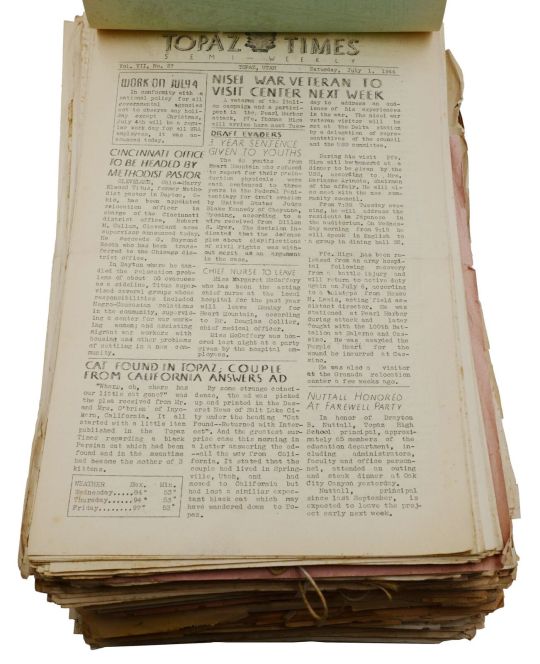

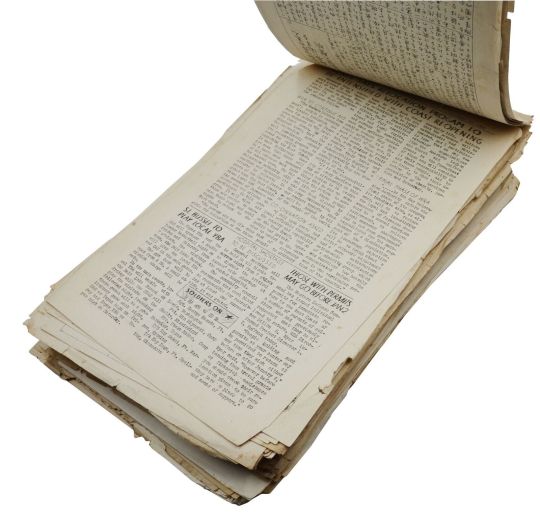

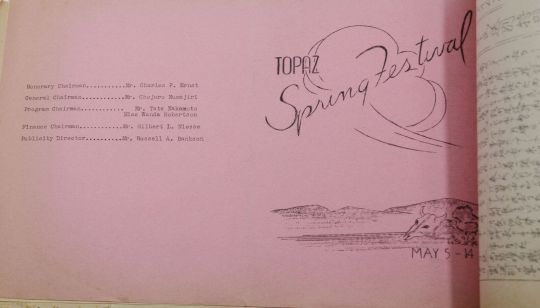

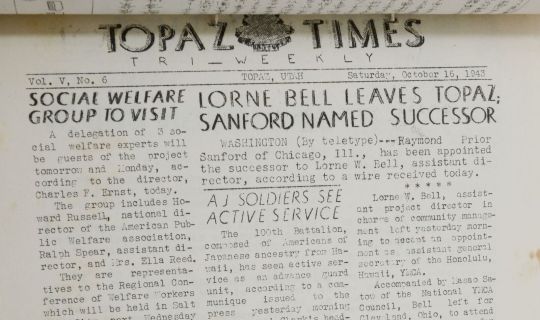

400 Issues of a Japanese Internment Camp Newspaper TOPAZ TIMES ~ War Relocation ebay Burnside Rare Books

0 notes

Text

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

February 19, 2024

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

Today is the anniversary of the day in 1942, during World War II, that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 enabling military authorities to designate military areas from which “any or all persons may be excluded.” That order also permitted the secretary of war to provide transportation, food, and shelter “to accomplish the purpose of this order.”

Four days later a Japanese submarine off the coast of Santa Barbara, California, shelled the Ellwood Oil Field, and the Office of Naval Intelligence warned that the Japanese would attack California in the next ten hours. On February 25 a meteorological balloon near Los Angeles set off a panic, and troops fired 1,400 rounds of antiaircraft ammunition at supposed Japanese attackers.

On March 2, 1942, General John DeWitt put Executive Order 9066 into effect. He signed Public Proclamation No. 1, dividing the country into military zones and, “as a matter of military necessity,” excluding from certain of those zones “[a]ny Japanese, German, or Italian alien, or any person of Japanese Ancestry.” Under DeWitt’s orders, about 125,000 children, women, and men of Japanese ancestry were forced out of their homes and imprisoned in camps around the country. Two thirds of those incarcerated were U.S. citizens.

DeWitt’s order did not come from nowhere. After almost a century of shaping laws to discriminate against Asian newcomers, West Coast inhabitants and lawmakers were primed to see their Japanese and Japanese-American neighbors as dangerous.

Those laws reached back to the 1849 arrival of Chinese miners in California and reached forward into the twentieth century. Indeed, on another February 19—that of 1923—the Supreme Court decided the case of United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind. It said that Thind, an Indian Sikh man who identified himself as Indo-European, could not become a U.S. citizen. Thind claimed the right to United States citizenship under the terms of the Naturalization Act of 1906, which had put the federal government instead of states in charge of who got to be a citizen and had very specific requirements for citizenship that he believed he had met.

But, the court said, Thind was not a “white person” under U.S. law, and only “free white persons” could become citizens.

What were they talking about? In the Thind decision, the Supreme Court reached back to the case of Japan-born Takao Ozawa, decided a year before, in 1922. In that case, the Supreme Court ruled that Ozawa could not become a citizen under the 1906 Naturalization Act because that law had not overridden the 1790 naturalization law limiting citizenship to “free white persons.” The court decided that “white person” meant “persons of the Caucasian Race.” “A Japanese, born in Japan, being clearly not a Caucasian, cannot be made a citizen of the United States,” it said.

As the 1922 case indicated, Asian Americans could not rely on the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1868, to permit them to become citizens, because a law from 1790 knocked a hole in that amendment. The Fourteenth Amendment provided that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.” But as soon as that amendment went into effect, the new states and territories of the West reached back to the 1790 naturalization law to exclude Asian immigrants from citizenship on the basis of the argument that they were not “free, white persons.”

That 1790 restriction, based in early lawmakers’ determination to guarantee that enslaved Africans could not claim citizenship, enabled lawmakers after the Civil War to exclude Asian immigrants from citizenship.

From that exclusion grew laws discriminating against Chinese immigrants, including the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act that prohibited Chinese workers from migrating to the United States. Then, when Chinese immigration slowed and Japanese immigration took its place, the U.S. backed the so-called Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907 under which Japanese officials promised to stop emigration to the United States. The United States, in turn, promised not to restrict the rights of Japanese immigrants already in the United States, although laws prohibiting “aliens” from owning land meant Japanese settlers either lost their land or had to put it in the names of their American-born children, who were citizens under the Fourteenth Amendment.

After the 1923 Thind decision, the United States stripped the citizenship of about 50 South Asian Americans who had already become American citizens. One of them was Vaishno Das Bagai, an immigrant from what is now Pakistan who came from wealth and who settled in San Francisco in 1915 with his wife and three sons to start a business. Less than three weeks after arriving in the United States, Bagai began the process of naturalization. He became a citizen in 1920.

The Thind decision took that citizenship away from Bagai, making him fall under California’s alien land laws that said he could not own land. He lost his home and his business. In 1928, explicitly telling the San Francisco Examiner that he was taking his life in protest of racial discrimination, Bagai committed suicide. His widow, Kala Bagai, became a community activist.

World War II changed U.S. calculations of who could be a citizen as global alliances shifted and Americans of all backgrounds turned out to save democracy. From Japanese-American concentration camps, young men joined the army to fight for the nation. In 1943 the War Department authorized the formation of Japanese-American combat units. One of those units, the 442d Regimental Combat Team, became the most decorated unit for its size in U.S. military history. Their motto was “Go for Broke.”

Congress overturned the Chinese exclusion laws in 1943 and, in 1946, made natives of India eligible for U.S. citizenship. The last Japanese internment camp closed in March 1946, and Japanese immigrants gained the right to become U.S. citizens in 1952.

In 1976, President Gerald R. Ford officially repealed Executive Order 9066 and noted that it was a “setback to fundamental American principles.” “We now know what we should have known then,” he said. “[N]ot only was that evacuation wrong, but Japanese Americans were and are loyal Americans…. I call upon the American people to affirm with me this American Promise—that we have learned from the tragedy of that long-ago experience forever to treasure liberty and justice for each individual American, and resolve that this kind of action shall never again be repeated.”

But now so-called “internment camps” are back in the news.

Trump has promised his supporters that in a second term he would launch “the largest domestic deportation operation in American history.” To deport as many as ten million of what he called “foreign national invaders,” Trump advisor Stephen Miller explained on a November podcast, the administration would federalize National Guard troops from Republican-dominated states and send them around the country to round people up, moving them to “large-scale staging grounds near the border, most likely in Texas,” that would serve as internment camps.

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#Letters from An American#Heather Cox Richardson#history#FDR#internment camp#Japanese Americans#Asian Americans#free white persons

1 note

·

View note

Text

Random thing but I remember the first day of sociology class my prof passed out photos of the Japanese internment camps and the first student that she called on says with full confidence “Those are Chinese people, they’re being discriminated against.” 🤓🤓

Bruh my family didn’t get forcibly interned for your dumbass to say that they were Chinese (it literally said Japanese on one of the photos)

Anyway, it’s very disheartening to know how many people don’t know what happened to Japanese Americans in the internment camps and how it’s affected our culture. I’m here to answer any questions and elaborate further, but it’s unfortunately not well known.

#japaneseamerican#japanese#japanese internment#we were in the japanese internment camps#internment camp#bruh

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mrs. S. Nako and Mrs. William Hosokawa knitting while imprisoned in the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Park County, Wyoming, (an internment camp), January 8, 1943.

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Presidential Proclamation 2537 which required that Americans from Germany, Italy or Japan must register with the Department of Defense, was issued on January 14, 1942. Proclamation No. 2537 permitted the arrest, detention and internment of enemy aliens who violated restricted areas, such as ports, water treatment plants or even areas prone to brush fires, for the duration of the war. Roosevelt reluctantly signed Executive Order 9066, which sent many Japanese-American families into internment camps, on February 19, 1942.

Source

#Presidential Proclamation 2537#14 January 1942#anniversary#US history#internment camp#Japanese-American history#Minidoka National Historic Site#Minidoka War Relocation Center#Minidoka Internment National Monument#Jerome County#Idaho#summer 2017#original photography#travel#vacation#WWII#landscape#high desert#countryside#architecture#World War Two#flora#free admission#tourist attraction#landmark

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Seeks Release Of Internees In Hull Jail,” Ottawa Journal. February 11, 1942. Page 3.

----

The new Hull jail at King's Park; Val Tetreau, built by the Duplessis Government and used for the last few months as an internment camp for internees came into the limelight twice on Tuesday afternoon in the House of Commons.

When the House first assembled, a petition "was read from internees' at Hull jail asking their release from detention on grounds of their steadfast anti-Fascist sympathies and their loyalty to Canadian democracy.

Later in the afternoon Mrs. Dorise Nielsen, United Progressive' (North Battleford, Sask.), said "This morning I visited the spokesman of the men who are interned in Hull Jail.

"The Canadian Seamen's Union is trying to enlist six thousand young men to go into the merchant marine. The union is not having all the success it would like in obtaining these men, and I will tell you why because the president of the union is interned in the Hull Jail."

Mrs. Nielsen also said: "In the camp at Hull there are some young French-speaking Canadians who would be willing to go out and rally their own people, but there they are, making trinkets, doing little odd jobs to keep themselves amused, while the country has to keep them, practically in idleness, and support their wives and children."

[AL: Most of the internees were Communists, union officials from ‘left unions’ (some associated with the Communist Party, but not all, and a number of other dissidents. They would be released several months later.]

#parliament of canada#canadian politics#parliamentary debate#communists#internment camp#hull jail#hull#gatineau#communist party of canada#communism#canadian seamen's union#suppression of political dissidents#political prisoners#canada during world war 2#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada

0 notes

Text

Japanese Internment Camp Yearbook ~ THE MINIDOKA INTERLUDE ~ 1989 Reprint EBAY nataliemzimmerman

0 notes

Link

“Is it surprising that prisons resemble factories, schools, barracks, hospitals, which all resemble prisons?” Michel Foucault (1995)

What first comes to mind when you think of the Greek islands? Carefree holidays on sandy beaches? Chalk-white cliffs melting into crystal-clear waters? Romantic sunsets next to ancient ruins? The Greek islands encompass all that. Greece has over 200 inhabited islands, the economy of which is organised around and largely depends on the influx of summer tourists. Yet, their history is much more complicated and traumatic than their representation in tourist information leaflets allows us to see.

Their insular character, small pieces of land surrounded by the sea and difficult to access, especially during the winter, makes most of them resemble natural prisons. And this is precisely how numerous islands –now popular tourist destinations— have been used by the Greek state during the politically turbulent 20th century.

In the Gulf of Elounda, in north-eastern Crete, a small island, Spinalonga, served as a leper colony between 1903 and 1957. With its famous volcano and breathtaking view, Santorini was an exile for political dissidents during Ioannis Metaxas’s fascist dictatorship in the late 1930s. Around the same period, the cosmopolitan island of Corfu became the place where the Greek Communist Party’s General Secretary Nikos Zachariadis was incarcerated. During the Greek Civil War (1946-1949), those suspected of communist (or at least anti-national) action were sent to exile in Zante, Kythira, Folegandros, Ikaria, Skiathos, Ai Stratis, and several other Greek islands. Makronisos, a small island off the coast of Athens, was transformed into a notorious concentration camp and military prison for the best part of the Civil War and the early post-Civil War period. The military dictatorship established in Greece between 1967 and 1974 made no exception: islands such as Amorgos, Gyaros, and Anafi accommodated exiles because of their political beliefs.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deutsche Seeleute im Langwarrin Internment Camp

Deutsche Seeleute im Langwarrin Internment Camp

Interniert in Australien

Titelbild: Eingang zum Langwarrin Camp, 1914-1915; Museums Victoria Collection, Item MM 140043

Anmerkung: Die in diesem Beitrag gezeigten Aufnahmen vom Lager Langwarrin stammen meist aus dem Jahr 1917. Zu diesem Zeitpunkt war Langwarrin kein Internierungslager mehr, sondern eine Krankenstation des australischen Militärs. 1914/1915 dürfte das Lager weit primitiver und…

View On WordPress

#Erster Weltkrieg#Friedrich Meier#Internierung#Internment Camp#Langwarrin#Lothringen#Melbourne#Norddeutscher Lloyd#Tagebuch#Victoria

0 notes

Photo

Ansel Adams (1902-1984) - Mess line, noon, Manzanar War Relocation Center, California

Vintage gelatin silver photograph. Taken in 1943.

Part of the collection of the Library of Congress.

During the autumn of 1943, Adams photographed at the Manzanar War Relocation Center, which was located in Inyo County, California, at the eastern edge of the Sierra Nevada mountains approximately 200 miles northeast of Los Angeles. Around 10,000 law-abiding Japanese-American men, women, and children were incarcerated out in the desert for the duration of the war. Concentrating on the internees and their activities, Adams photographed family life in the barracks; people at work– internees as welders, farmers, and garment makers; and recreational activities, including baseball and volleyball games.

In 1965, Adams donated his collection of over 250 images to the Library of Congress. He wrote: "The purpose of my work was to show how these people, suffering under a great injustice, and loss of property, businesses and professions, had overcome the sense of defeat and despair by building for themselves a vital community in an arid (but magnificent) environment....All in all, I think this Manzanar Collection is an important historical document, and I trust it can be put to good use."

You can see them here:

https://www.loc.gov/collections/ansel-adams-manzanar/about-this-collection/

#Ansel Adams#Japanese-American internment#Japanese internment#internment#internment camp#Manzanar#Manzanar Relocation Center

31 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I wasn't happy or sad. I couldn't feel anything. It's something I can’t explain. It’s like my feelings died while I was in there.

Nurlan Kokteubai, survivor of Xinjiang internment camp, on his emotional state upon being released ("China Secretly Built A Vast New Infrastructure to Imprison Muslims," via BuzzFeed News)

#uighur#uighur muslims#xinjiang#internment camp#ethnic minority#religious persecution#ethnic persecution#buzzfeed news#megha rajagopalan#alison killing#christo buschek#concentration camp#kazakh#government censorship#to round up everyone who should be rounded up#shufu#shule#qapqal xibe#dabancheng#gaochang#kashgar#urumqi#turpan#satellite imagery

0 notes