#ira gitler

Text

Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane

Certain combinations of men have been leaving marks on music called jazz since its beginning. Some formed a lifetime association; others were together only for a brief period. Some actively shaped the course of jazz; others affected it more osmotically. All have had one thing in common; they produced music of lasting value.

One historic teaming was that of Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane at New York's Five Spot Cafe, beginning in the summer of 1957. Although the group remained together for only a half-year, those of us who heard it will never forget the experience. There were some weeks when I was at the Five Spot two and three times, staying most of the night even when I intended just to catch a set or two. The music was simultaneously kinetic and hypnotic. J.J. Johnson has compared it to the mid-Forties union of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. "Since Charlie Parker, the most electrifying sound that I've heard in contemporary jazz was Coltrane playing with Monk at the Five Spot... It was incredible, like Diz and Bird," Jay said.

Monk and Coltrane complemented each other perfectly. The results of this successful musical alliance were beneficial to both. In this setting, Monk began to receive the brunt of a long-overdue recognition. On the other hand, Coltrane's talent, set in such fertile environment, bloomed like a hibiscus. 'Trane's comments in a Down Beat article [September 29, 1960] clearly describe how he reveres Monk. "Working with Monk brought me close to a musical architect of the highest order. I felt I learned from him in every way through the senses, theoretically, technically. I would talk to Monk about musical problems and he would sit at the piano and show me the answers by playing them. I could watch him play and find out the things I wanted to know. Also, I could see a lot of things that I didn't know about at all," he stated.

Later in the piece, 'Trane added: "I think Monk is one of the true greats of all time. He's a real musical thinker- -there's not many like him. I feel myself fortunate to have had the opportunity to work with him. If a guy needs a little spark, a boost, he can just be around Monk, and Monk will give it to him." Monk certainly brought 'Trane out beautifully. It was in this period that John began to experiment with what at the time I called "sheets of sound." Actually, he was thinking in groups of notes rather than one note at a time. Monk's practice of "laying out" allowed 'Trane to "stroll" against the pulse of bass and drums and really develop this playing attitude on his own. Pointed examples of this can be heard here in "Trinkle, Tinkle" and "Nutty."

Toward the latter part of '57, Ahmed Abdul-Malik took over Wilbur Ware's bass post. But in the three selections here, the original quartet is intact. Ware and Monk had played together on one of Thelonious's visits to Chicago, and when Wilbur migrated to New York he was Monk's choice for the group. I find no coincidence in Martin William's statement that Ware ... has something of the same basic interest in displacement of accents and rhythmic shiftings and in unusual sequence of harmonics that one hears in Thelonious Monk." Listen to Ware's solo on "Trinkle, Tinkle" for evidence.

Shadow Wilson was about two and a half months short of his 40th birthday when he died on July 11, 1959, and another of jazz's Coltrane (left), Monk tremendous talents had left the scene far too early. A great big-band drummer, Wilson had performed most notably with Count Basie and Woody Herman (the Herman band once voted for him en masse, when a replacement was needed for Dave Tough), but he was equally capable of ministering to the specific needs of a small group. His post. But in the three selections here, the original quartet is intact. Ware and Monk had played together on one of Thelonious's visits to Chicago, and when Wilbur migrated to New York he was Monk's choice for the group. I find no coincidence in Martin William's statement that Ware ... has something of the same basic interest in displacement of accents and rhythmic shiftings and in unusual sequence of harmonics that one hears in Thelonious Monk." Listen to Ware's solo on "Trinkle, Tinkle" for evidence.

Shadow Wilson was about two and a half months short of his 40th birthday when he died on July 11, 1959, and another of jazz's Coltrane (left), Monk tremendous talents had left the scene far too early. A great big-band drummer, Wilson had performed most notably with Count Basie and Woody Herman (the Herman band once voted for him en masse, when a replacement was needed for Dave Tough), but he was equally capable of ministering to the specific needs of a small group. His aware accenting of "Trinkle, Tinkle" shows how well he understood Monk's music and his nourishing beat, here and on "Nutty," is a rare combination of swing and taste. Don Schlittenk and Wilson on the bandstand at the Five Spot.

As we were to regret the passing of Shadow Wilson in 1959, many of us, in a different way, bemoaned the demise of that particular Monk quartet at the end of 1957. The fact that the group had presumably not been recorded was especially distressing. Now we have three gems to hold in our hands and enjoy, facet by facet. All are Monk compositions, and it is interesting to note that they were originally recorded in trio contexts by him: "Ruby, My Dear," which I once described as "sentiment without sentimentality," was first done around 1948, although it was probably written several years before. Coltrane states its tender beauty with a tone that helps transmit the sadness pervading the melody. Monk's half-chorus says more than most pianists do in a whole LP.

"Trinkle, Tinkle" originated in 1952. There is some fascinating interplay between piano and tenor in 'Trane's first improvised chorus. This is followed by some fantastic Coltrane in the "strolling" section. If you close your eyes, it is easy to imagine a cello or viola being bowed by a demonic force of vivid imagination. Thelonious rephrases his own melody in his inimitable manner before Ware's solo.

"Nutty," written in 1954, swings relaxed in an optimistic mood. Coltrane spins out his amazingly long-lined offerings, handing them together with shorter bursts and an overall personal sense of logic. Monk again divides and subdivides his own theme, paraphrasing from one of his earlier speeches, as it were.

To round out the album, three alternate masters from previously released Monk sessions are included. "Off Minor" and "Epistrophy" were heard on Monk's Music (Riverside RLP 242). It is stimulating to compare the different versions and how the solos vary and coincide from take to take. "Off Minor" has solos by Hawkins, Copeland, and Monk, but the bits by Ware and Blakey are not as developed as on the original issue. "Epistrophy," in the original version, featured all the horns of the septet and Monk. Here, only Coltrane and Copeland are heard in solo.

The first "Functional" is on Thelonious Himself (Riverside RLP 235). This version is as different in individual idea and, at the same time, close in spirit to the other, as two takes can be. It almost deserves a title of its own. I only wish I had two turntables. I think the two "Functional’s might make a wild duet for four Monk hands.

But, as intriguing as these alternate masters are, the main attraction here is the unearthing of the quartet tracks. These are milestones in jazz history and important to every serious listener.

Steve Lacy, the soprano saxophonist who worked with Monk for sixteen weeks in 1960, has said of Monk's music: "Monk has got his own poetry and you've got to get the fragrance of it."

It is obvious that in 1957, Coltrane was doing some deep breathing.

Ira Gitler

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

(62 YEARS AGO)

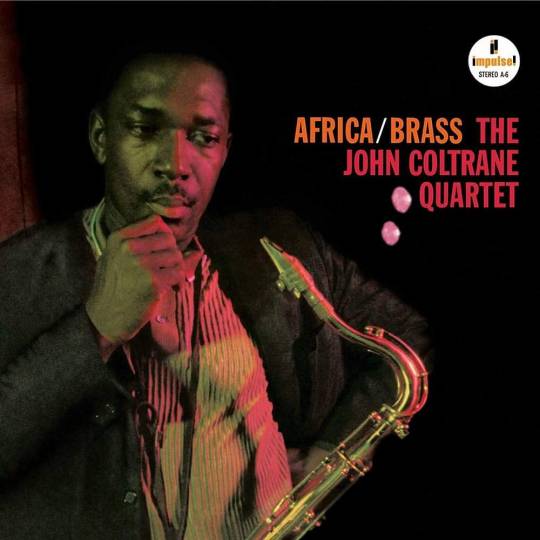

September 1, 1961 - John Coltrane: Africa/Brass is released.

# ALL THINGS MUSIC PLUS+ 4/5

# Allmusic 4.5/5

# Down Beat 2/5

Africa/Brass is the eighth studio album by John Coltrane, released on September 1, 1961.

Recorded:

May 23, 1961 and June 7, 1961, at RVG's Englewood Cliffs studio

Personnel:

John Coltrane – soprano and tenor saxophone

Booker Little – trumpet

Julius Watkins, Bob Northern, Donald Corrado, Robert Swisshelm – french horn

Bill Barber – tuba

Pat Patrick – baritone saxophone

McCoy Tyner – piano

Reggie Workman – bass

Elvin Jones – drums

__________

ORIGINAL LINER NOTES

John Coltrane is a quiet, powerfully-built young man who plays tenor saxophone quite unlike anyone in all of jazz. His style has been described as "sheets of sound" or as "flurries of melody." But, despite the accuracy, or lack of accuracy, of such descriptions, it is a fact that Coltrane's style is wholly original and of growing influence among new tenor players.

Perhaps he himself best described his dazzling style in a recent Down Beat article with writer Don DeMichael. "I started experimenting because I was trying for more individual development. I even tried the long, rapid lines that Ira Gitler termed 'sheets of sound' at the time. But actually, I was beginning to apply the three-to-one chord approach and at this time the tendency was to play the entire scale of each chord. Therefore, they were usually played fast and sometimes sounded like glisses."

Although Coltrane has absorbed this experiment into his present style and moved on, its effect was shocking, and intriguing, in the jazz world.

Most recently, as this album will attest, Coltrane has become absorbed by the rhythms of Africa. During the editing sessions for this album he noted, "There has been an influence of African rhythms in American jazz. It seems there are some things jazz can borrow harmonically, but I've been knocking myself out seeking something rhythmic. But nothing swings like 4/4. These implied rhythms give variety."

For this record, Coltrane composed two of the three selections, then discussed the orchestration thoroughly with Eric Dolphy, a reed player of enormous talent. Pianist McCoy Tyner of Coltrane's group was the third member of the discussion group.

"Actually," Dolphy recalled, "All I did was orchestrate. Basically John and McCoy worked out the whole thing. And it all came from John; he knew exactly what he wanted. And that was, essentially, the feeling of his group."

AFRICA has an unusual form. Its melody had to be stated in the background because Coltrane is not tied down by chords. "I had a sound that I wanted to hear," Coltrane remarked of this composition. "And what resulted was about it. I wanted the band to have a drone. We used two basses. The main line carries all the way through the tune. One bass plays almost all the way through. The other has rhythmic lines around it. Reggie and Art have worked together, and they know how to give and take." This work began with Coltrane's quartet. He listened to many African records for rhythmic inspiration. One had a bass line like a chant, and the group used it, working it into different tunes. In Los Angeles, John hit on using African rhythms instead of 4/4, and the work began to take shape. Tyner began to work chords into the structure, and, in John's own words, "it's been growing ever since."

The instrumentation--trumpet, four French horns, alto sax, baritone sax, two euphoniums, two basses, piano, drums, and tuba--is among the most unusual in jazz. But, Dolphy explained, "John thought of this sound. He wanted brass, he wanted baritone horns, he wanted that mellow sound and power."

Coltrane heard the playbacks and nodded. "It's the first time I've done any tune with that kind of rhythmic background. I've done things in 3/4 and 4/4. On the whole, I'm quite pleased with Africa."

GREEN SLEEVES is an updating of the old, revered folk song. It's included in this set because Coltrane, in recent months, has been studying folk music. "It's one of the most beautiful folk melodies I've heard," he said. "It's written in 6/8, and we do it just about as written. There's a section for improvisation with a vamp to blow on."

The quartet has been playing this theme recently, and the arrangement is based on Tyner's chords. Dolphy notated it. "For me," Coltrane said, "Greensleeves is the most enjoyable to play. Most of the time we get a nice pulse and groove. It was a challenge to add the band to it. I wanted to keep the feeling of the quartet. That's why we took the same voicings and the same rhythm McCoy comps in."

BLUES MINOR is a piece the quartet has been playing of late. It was assembled at the recording session. "It's a head," Dolphy said. "McCoy gave me the notes. I wrote out the parts, and the band did it on one take." It swings loosely with the ease and drive of a head arrangement.

All in all, this album is representative of the state of musical mind of John Coltrane, 34, on his way to something new and exciting, but pausing along the way to sum up the fresh and provocative work he has accomplished this far.

~ Dom Cerulli

TRACKS

Side one

1. Africa (Coltrane) – 16:28

Side two

1. Greensleeves (traditional, arranged by McCoy Tyner) – 10:00

2. Blues Minor (Coltrane) – 7:22

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Coltrane - Giant Steps

Fifth studio album by jazz musician

Release Date: February 1960

12/13

History will undoubtedly enshrine this disc as a watershed the likes of which may never truly be appreciated. Giant Steps bore the double-edged sword of furthering the cause of the music as well as delivering it to an increasingly mainstream audience. Although this was John Coltrane's debut for Atlantic, he was concurrently performing and recording with Miles Davis. Within the space of less than three weeks, Coltrane would complete his work with Davis and company on another genre-defining disc, Kind of Blue, before commencing his efforts on this one. Coltrane (tenor sax) is flanked by essentially two different trios. Recording commenced in early May of 1959 with a pair of sessions that featured Tommy Flanagan (piano) and Art Taylor (drums), as well as Paul Chambers -- who was the only bandmember other than Coltrane to have performed on every date. When recording resumed in December of that year, Wynton Kelly (piano) and Jimmy Cobb (drums) were instated -- replicating the lineup featured on Kind of Blue, sans Miles Davis of course. At the heart of these recordings, however, is the laser-beam focus of Coltrane's tenor solos. All seven pieces issued on the original Giant Steps are likewise Coltrane compositions. He was, in essence, beginning to rewrite the jazz canon with material that would be centered on solos -- the 180-degree antithesis of the art form up to that point. These arrangements would create a place for the solo to become infinitely more compelling. This would culminate in a frenetic performance style that noted jazz journalist Ira Gitler accurately dubbed "sheets of sound." Coltrane's polytonal torrents extricate the amicable and otherwise cordial solos that had begun decaying the very exigency of the genre -- turning it into the equivalent of easy listening. He wastes no time as the disc's title track immediately indicates a progression from which there would be no looking back. Line upon line of highly cerebral improvisation snake between the melody and solos, practically fusing the two. The resolute intensity of "Countdown" does more to modernize jazz in 141 seconds than many artists do in their entire careers. Tellingly, the contrasting and ultimately pastoral "Naima" was the last tune to be recorded, and is the only track on the original long-player to feature the Kind of Blue quartet. What is lost in tempo is more than recouped in intrinsic melodic beauty. Both Giant Steps [Deluxe Edition] and the seven-disc Heavyweight Champion: The Complete Atlantic Recordings offer more comprehensive presentations of these sessions.

youtube

https://www.allmusic.com/album/giant-steps-mw0000604243

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

IKE QUEBEC, LE PARCOURS MÉCONNU D’UN PASSIONNÉ DU JAZZ

’’This incontestably superior musician has been almost totally ignored in the chronicling of the musical form to which he has contributed so much. Quebec was a tenor man of the Hawkins school with a big tone and firm, vigorous style. I hope this new perspective of the contribution Ike Quebec has made to jazz will help to bring a little lightness to his soul and much more recognition to his name.”

- Leonard Feather

Né le 17 août 1918 à Newark, au New Jersey, Ike Abrams Quebec a amorcé sa carrière comme danseur et pianiste avant de passer au saxophone ténor au début des années 1920. Quebec était le cousin du saxophoniste alto Danny Quebec West qui avait enregistré avec Thelonious Monk lors de sa première session pour Blue Note en 1947.

DÉBUTS DE CARRIÈRE

Rapidement reconnu comme un musicien prometteur, Quebec a fait ses débuts sur disque en 1940 avec les Barons of Rhythm. Au cours des années suivantes, Quebec a joué et enregistré avec Frankie Newton, ’’Hot Lips'' Page, Roy Eldridge, Trummy Young, Ella Fitzgerald, le groupe Sunset Royals, Benny Carter et Coleman Hawkins. De 1944 à 1951, Quebec s’est produit sur une base intermittente avec Cab Calloway.

Après avoir commencé à enregistrer pour les disques Blue Note, Quebec avait travaillé comme recruteur de talent et avait aidé Thelonious Monk et Bud Powell à se développer. Une des plus importantes réalisations de Quebec comme recruteur avait été d’attirer dans le giron de Blue Note le saxophoniste Dexter Gordon. Agé de trente-huit ans au moment de son premier enregistrement avec la firme en mai 1961, Gordon était presque sorti de nulle part. Plutôt discret dans les notes de pochette qu’il avait rédigées pour l’album ‘’Doin’ Alright’’, le critique Ira Gitler écrivait: ‘’Veteran listeners will certainly remember him but younger fana probably will not although he was intermittently active during the Fifties.’’ Après avoir fait deux séjours en prison au cours de la décennie précédente, Gordon faisait rarement des apparition dans les studios d’enregistrement. L’album était éventuellement devenu un classique.

De cinq ans plus âgé que Gordon, la carrière de Quebec avait été moins affectée, mais avec moins de réalisations à son crédit, ses albums avaient attiré peu d’attention. Contrairement aux autres chefs de file des disques Blue Note comme Andrew Hill, Wayne Shorter et Larry Young, Quebec avait connu un itinéraire atypique. Quebec faisant partie des musiciens les plus âgés à avoir enregistré avec la firme dans les années 1960, il précédait presque d’une génération ses jeunes collègues. Même si Québec était à sa place aux côtés de membres de l’orchestre de Count Basie comme Eddie ‘’Lockjaw’’ Davis, son style de jeu annonçait déjà le jazz soul des années 1960. Les titres des albums de Quebec - ‘’Heavy Soul’’, ‘’Blue And Sentimental’’, etc. - préfiguraient d’ailleurs la transition entre les anciennes et les nouvelles approches. Peu ambitieux et pour ne pas dire peu innovateurs, les albums de Québec étaient remplis de standards et de blues, et étaient marqués par la prépondérance de tempos plutôt lents, même s’ils comprenaient aussi des pièces beaucoup plus rythmées.

En raison de ses aptitudes remarquables pour lire la musique, Quebec avait aussi été employé comme arrangeur occasionnel (cependant non crédité) dans le cadre de plusieurs sessions pour Blue Note.

Les 45-tours enregistrés par Quebec pour Blue Note n’étaient pas ses premières réalisations avec la compagnie de disques. Dans les années 1940, Quebec avait enregistré une série de 78-tours avec des groupes de swing. Parmi les pièces enregistrées par Quebec à l’époque, on remarquait le standard "She's Funny That Way," "Cup Mute Clayton" (une composition en hommage au trompettiste Buck Clayton) et "Blue Harlem." Les disques Blue Note avaient même publié un album 78-tours comprenant six de ses meilleures pièces, parmi lesquelles on retrouvait des succès comme "If I Had You", "Dolores" et "Topsy." En 1945, Quebec avait participé à quatre sessions pour Blue Note et à une session pour les disques Savoy qui incluaient notamment son grand succès "Blue Harlem’’, dans lequel il était accompagné de Tiny Grimes à la guitare et de Roger Ramirez au piano. Une autre excellente pièce enregistrée par Quebec à l’époque était "Blue turnin' grey over you", même si Blue Note n’avait pas décidé de la mettre en marché immédiatement.

En raison en partie de sa dépendance envers l’héroïne, mais aussi à cause de la baisse de popularité des big bands, Quebec avait enregistré de façon sporadique au cours des années 1950, même s’il avait continué de se produire sur scène sur une base régulière. Se tenant informé des plus récents développements du jazz, Quebec avait plus tard incorporé dans sa musique des éléments de hard bop, de bossa nova et de soul.

En 1959, Quebec avait tenté de revenir sur le devant de la scène en enregistrant huit simples pour Blue Note destinés au marché des juke box. Même si le président de Blue Note, Alfred Lion, adorait la musique de Quebec, il n’était pas certain de la façon dont celle-ci serait accueillie par le public après ses nombreuses années d’absence.

Lion avait vu le retour de Quebec comme une sorte de ballon d’essai. Il précisait: ‘’I was delighed to find not only that many people still remembered Ike, but also that those who didn’t know him were amazed and excited by what they heard. So recently I decides to jump into a full album session with new material to give Ike a complete new start.’’

Il avait fallu plus d’un an à Lion pour inviter Quebec à participer à une autre session. Parmi les pièces enregistrées, on remarquait le standard ‘’Everything Happens to Me’’ qui avait été publié en deux versions, une version longue et une version plus courte. Quebec avait enregistré neuf autres simples en 1962. Il s’agissait d’une combinaison de blues et de standards. Un des principaux intérêts des enregistrements de Quebec à cette époque était qu’ils utilisaient à la fois un organiste (Freddie Roach) et un contrebassiste (Milt Hinton le plus souvent). Le batteur Al Harewood participait également aux enregistrements. La plupart des formations à l’orgue se passaient des services d’un contrebassiste, mais Quebec préférait se servir de l’orgue comme soutien mélodique et non comme seul soutien rythmique, une approche qui avait donné d’excellents résultats ainsi qu’un son plus dense et plus profond.

En guise de répertoire, Quebec avait sélectionné des classiques éprouvés comme ‘’I Want A Little Girl’’, ‘’The Man I Love’’ et même ‘’Brother Can You Spare A Dime.’’ Quelques jours plus tard, le groupe était retourné en studio pour enregistrer le standard ‘’It Might As Well Be Spring.’’ Malheureusement, les pièces ‘’Ol’ Man River’’ et ‘’Willow Weep for Me’’ avaient donné des résultats moins concluans. Une semaine plus tard, Lion avait organisé une autre session avec un alignement composé de Grant Green à la guitare, de Paul Chambers à la contrebasse et de Philly Joe Jones à la batterie. La session avait éventuellement donné lieu à la publication du classique ‘’Blue And Sentimental’’ (1961), une collection de ballades dans lesquelles Quebec accompagnait les solos du guitariste Grant Green à la fois comme saxophoniste et pianiste.

1961 avait été une grande année pour Quebec. Le saxophoniste avait publié trois albums cette année-là: ‘’Heavy Soul’’, ’’It Might As Well Be Spring’’ et ‘’Blue and Sentimental.’’ Les trois albums avaient été enregistrés dans le cadre d’une série de quatre sessions tenues entre la Thanksgiving et Noël. Les deux premières sessions avaient été enregistrées avec une formation composée de Freddie Roach à l’orgue, de Milt Hinton à la contrebasse et d’Al Harewood à la batterie. Quant à la session ‘’Blue and Sentimental’’, elle mettait en vedette Grant Green à la guitare, Paul Chambers à la contrebasse et Philly Joe Jones à la batterie. La version sur CD comprenait également une pièce bonus: “Count Every Star,” avec Sonny Clark au piano, Sam Jones à la contrebasse et Louis Hayes à la batterie.

Sur l’album ‘’Heavy Soul’’, le jeu de Quebec rappelait fortement le son de John Coltrane sur l’album éponyme de Miles Davis publié en 1955. Utilisant un phrasé lent et réfléchi, Quebec s’était démarqué du jeu des jeunes saxophonistes de l’époque qui avaient tendance à rejeter ce style de jeu en raison de son caractère excessivement sentimental. Le saxophoniste Archie Shepp avait plus tard fait revivre ce type de jeu à la fin des années 1960. Loin de se limiter aux ballades, Quebec s’était également livré à des interprétations plus endiablées dans des pièces comme “Acquitted” et “Blues for Ike” qui avaient occupé les deux extrémités de l’album.

L’album ‘’It Might As Well Be Spring’’, qui avait été enregistré moins de deux semaines plus tard avec la même formation, était également excellent. Sur l’album, Quebec avait repris “A Light Reprieve”, une chanson qu’il avait publié sous forme de 45-tours avec un arrangement beaucoup moins orienté vers le swing et le bebop. Très court, l’album ne comptait que six pièces et était d’une durée de seulement trente-cinq minutes comparativement à l’album ‘’Heavy Soul’’ qui comprenait un total de neuf pièces pour une durée de plus de quarante-cinq minutes. Même si l’album ‘’Blue and Sentimental’’ avait fait connaître Quebec à plusieurs amateurs de jazz, il n’était pas nécessairement meilleur que les autres enregistrements qu’il avait réalisés durant cette période. Contrairement à ce que laissait suggérer son titre, ‘’Blue and Sentimental’’ n’était pas qu’un album de ballades et comportait également plusieurs blues et standards très rythmés.

Quebec avait participé à une dernière session en octobre 1962 avec un groupe composé de Kenny Burrell à la guitare, de Wendell Marshall à la contrebasse, de Garvin Masseaux au chekere (un instrument de percussion utilisé en Afrique et en Amérique latine) et de Willie Bobo à la batterie. La session avait éventuellement donné lieu à la publication de l’album ‘’Soul Samba’’, un disque très influencé par la musique brésilienne qui annonçait les enregistrements ultérieurs de Stan Getz. Des deux dernières sessions enregistrées en 1962 par Quebec, c’était la seule qui avait été publiée du vivant du saxophoniste. Cinq des pièces enregistrées au début de l’année avaient été publiées en 1981 sous le titre de ‘’Congo Lament.’’ L’album avait été enregistré avec un groupe composé de Bennie Green à la guitare, de Stanley Turrentine au saxophone ténor, de Sonny Clark au piano, de Milt Hinton à la contrebasse et d’Art Blakey à la batterie. En 1987, les pièces de ‘’Congo Lament’’ ont été rééditées avec trois autres pièces inédites sous le titre de ‘’Easy Living.’’ Même si le jeu de Quebec semblait plutôt anachronique à certains égards, il lui avait permis de démontrer un grand sens du blues. Une session de ballades avec un groupe sensiblement moins relevé avait également été organisée par Lion.

DÉCÈS ET POSTÉRITÉ

Le retour de Quebec n’avait duré qu’un temps. Ike Quebec est mort le 16 janvier 1963 d’un cancer des poumons à l’âge de seulement quarante-quatre ans. Quebec a été inhumé au Woodland Cemetery de Newark, au New Jersey. Quelques jours plus tard, le milieu du jazz avait perdu un autre de ses piliers: le pianiste Sonny Clark, qui était décédé d’une overdose.

Quebec s’était très peu produit comme accompagnateur au cours des dernières années de sa vie. On peut l’entendre notamment sur les albums ‘’Gooden’s Corner’’ et ‘’Born to Be Blue’’ du guitariste Grant Green, ainsi que sur les albums ‘’Open House’’ et ‘’Plain Talk’’ de l’organiste Jimmy Smith, sur le disque ‘’My Hour of Need’’ de la chanteuse Dodo Greene et sur une pièce de l’album ‘’Leapin’ and Lopin’’’ de Sonny Clark.

Malgré tous ses succès, Quebec n’avait jamais fait partie de la fine crème des musiciens produits par les disques Blue Note dans les années 1960. Ce manque de reconnaissance était attribuable en partie au fait que Quebec était mort au début de 1963, avant l’arrivée de nouveaux talents comme Joe Henderson, Sam Rivers, Andrew Hill, Bobby Hutcherson et Grachan Moncur III, qui avaient fait leurs débuts avec Blue Note entre 1963 et 1965. Il faut dire que Quebec était issu d’une autre génération et n’avait rien en commun avec les ‘’jeunes loups’’ qui avaient émergé au début des années 1960. Quebec avait amorcé sa carrière dans les années 1940 avec des vétérans comme Cab Calloway, Tiny Grimes et Roy Eldridge. Même s’il avait enregistré comme leader pour Blue Note de 1944 à 1948, Quebec était tombé dans l’oubli dans les années 1950, principalement en raison de ses problèmes de dépendance. Lorsque Quebec avait fait son retour avec Blue Note en 1959, il était déterminé à rattraper le temps perdu, mais c’était trop peu, trop tard. Les vingt-six simples de Quebec ont été réédités dans un coffret de deux CD intitulé “The Complete Blue Note 45 Sessions.” Même si le coffret est maintenant épuisé, il est possible de le télécharger.

Le critique et historien du jazz Leonard Feather avait écrit au sujet de Quebec:

’’This incontestably superior musician has been almost totally ignored in the chronicling of the musical form to which he has contributed so much. Quebec was a tenor man of the Hawkins school with a big tone and firm, vigorous style. I hope this new perspective of the contribution Ike Quebec has made to jazz will help to bring a little lightness to his soul and much more recognition to his name.”

Pour sa part, le critique français Hughes Panassie avait affirmé: "Ike Quebec is a direct and vigorous musician, playing with great power and swing; he excels in blues." Aujourd’hui complètement tombé dans l’oubli, Quebec était considéré comme un pionnier des ballades. Au niveau du style, Quebec était reconnu comme un excellent saxophoniste ténor qui jouait un peu dans le style de Coleman Hawkins. Quebec avait été particulièrement influencé par Hawkins, Ben Webster et Stan Getz. Même si la carrière de Quebec avait connu des hauts et des bas, il n’avait jamais été forcé de prendre un ‘’travail de jour’’ afin d’assurer sa subsistance et avait continué de se produire dans des contextes jazz jusqu’à sa mort. Même si Quebec n’avait jamais vraiment été un innovateur, son style était très original et facilement identifiable. La plupart des albums de Quebec sont toujours disponibles, que ce soit sur copie physique ou par l’entremise de téléchargements.

©- 2024, tous droits réservés, Les Productions de l’Imaginaire historique

SOURCES:

CERRA, Steven. ‘’Ike Quebec.’’ Steven Cerra, 30 janvier 2018.

‘’Ike Quebec.’’ All About Jazz, 2023.

‘’Ike Quebec.’’ Wikipedia, 2023.

‘’Ike Quebec.’’ Burning Ambulance, 2023.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tadd Dameron With John Coltrane - Mating Call (Japanese Pressing)

Prestige – SMJ-6538(M), Mono Vinyl LP, 1977 Japanese Pressing

Side 1.

1. Mating Call

2. Gnid

3. Soultrane

Side 2.

1. On A Misty Night

2. Romas

3. Super Jet

Credits:

Bass – John Simmons

Cover – Edwards, Hannan

Drums – Philly Joe Jones

Liner Notes – Ira Gitler

Piano, Composed By – Tadd Dameron

Recorded By – Van Gelder

Supervised By – Bob Weinstock

Tenor Saxophone – John Coltrane

Barcode and Other…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

John Coltrane's improvisation style analysis (sheet music incl.)

John Coltrane's improvisation style analysis (sheet music incl.)John Coltrane - I Want To Talk About You (LIVE improvisation)

Best Sheet Music download from our Library.Conclusion

Please, subscribe to our Library. Thank you!

John Coltrane's improvisation style analysis (sheet music incl.)

John Coltrane - I Want To Talk About You (LIVE improvisation)

https://youtu.be/ADPm-3JMbwo

Pattern in melodic improvisation and harmonic progression in the music of John Coltrane.

John Coltrane (1926-1947) was a leading African-American jazz musician, performing mainly on tenor and soprano saxophones. Coltrane's music is renowned for its fiery creativity and the saxophonists visceral approach. This uninhibited style has led some listeners to be dismissive of his style, considering his note choice to be random and meaningless.

This is particularly true of his more unhinged performances,

such as the seminal free jazz album Ascension and the cadenza which follows his performance of "I Want to Talk about You" on the album Live at Birdland.

The words of Associate Editor of prominent jazz publication Downbeat, John Tynan, who stated (Down Beat Magazine,) on listening to a 1961 performance of the saxophonist, "that listened to a horrifying demonstration of what appears to be a growing anti-jazz trend exemplified by those foremost proponents of what is termed avant-garde music" exemplify this trend.

Coltrane's motivation for playing these kinds of free cadenzas is touched upon in The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, where it is stated that in pieces such as Giant Steps, Coltrane, by seeking to escape harmonic clichés

had inadvertently created a one dimensional improvisatory style.

In the late 1950s, he pursued two alternative directions. First, his expanding technique enabled him to play what the critic Ira Gitler called sheets of sound. It is these sheets of sound that can be heard clearly in the cadenza to I Want to Talk About You. Furthermore, Barry Kernfeld comments that such flurries

.... disguised his excessive reiteration of formulae. By revealing Coltrane's techniques, we think we may inspire many modern Jazz improvisers and musicians.

Coltrane's cadences

If we analyze the above section in depth, it is possible to see it as implying a II-V-I cadence typical of the jazz idiom, one that Coltrane would have been very familiar with.

An example of such a cadence would be the Dm7 G7 Cmaj7 that comes in the last 4 bars of a conventional jazz 12 bar blues in C major. This extract is to some degree a pastiche of the clichéd jazz lick shown below, which is often played over a II-V-I cadence.

Particularly from bar 5 in Coltrane's phrase, we see the guide tone of F# (implying the chord of G minor with a major 7th) descend to an F (implying G minor with a lowered 7th) and then to an E (forming the 3rd of C7). Fig. 3 above indicates these common guide-tones with arrows.

A scale that jazz musicians commonly use over dominant seventh chords is the altered scale. This scale is a mode of the melodic minor scale, and is formed by starting on the leading note of that scale.

Over a tonality of G7, this scale emphasizes all the notes that are outside the conventional sound of the chord, and so is typical of harmonically complex jazz.

In How to Comp, Hal Crook describes this effect as altered tensions (Hal Crook, How to Comp, (Advance Music, 1995) p.17). Notably, the 3rd (B) and 7th (F) are not altered, as this would too drastically change the function of the chord.

In addition to playing the scale linearly, one can also derive a number of shapes and patterns from it. Just as we can derive F and G major triads from the C major scale, we can derive C# and D# major triads from the G altered scale.

Below, we see how both Ab and Bb(A#) minor triads are also built into the altered scale.

It is the minor triad that is built on the b2 of the scale that Coltrane uses in this extract.

Here we see, in the context of a C dominant seventh chord, a C# minor triad. This is a clear indication of Coltrane deriving the minor triad shape from the C altered scale.

We can see many examples of Coltrane superimposing harmony over existing chord changes outside this cadenza.

Coltrane will often use triadic or arpeggaic constructions

as these are often the clearest ways to describe harmony. An example might be bars 9-12 of the saxophonists solo on Blue Train from the album of the same name. Blue Train, as its name suggests, is a 12 bar-blues in the key of Eb.

Therefore, the last 4 bars of each 12 bar chorus contain a II-V-I cadence in the key of Eb. In his solo, Coltrane does not stick rigidly to the chords of Fm7 - Bb 7 - Eb 7, but instead implies contrasting harmony over the top.

The key section is shown with the square brackets. In this section, Coltrane is not using the altered scale over the C7 chord, as the F natural used in the line does not fit into that scale.

Instead, it appears that Coltrane is implying a minor plagal cadence over the chord changes. Since a plagal cadence is the resolution from chord IV to chord I, a minor plagal cadence is the resolution from chord IV minor to chord I.

In this case, that resolution is from the clear Bb minor shape indicated by the square brackets to the F natural that is the first note of the next bar. This example demonstrates that Coltrane was not limited to altered scale vocabulary in his harmonic language.

Repeating Motifs

In the cadenza, Coltrane does repeat certain ideas that demonstrate that his improvisation is to some degree based on things that he has assimilated and practiced rather than being completely wild and free. One such motif is heard twice, once at (06:16) and again at (06:24).

If we assume that this pattern is derived from a diatonic scale or mode, there are several possible harmonic interpretations of it. The one I thought of at first was that it

could imply the tonality of G Lydian.

Similarly, it could be descriptive of the church modes of D. On the other hand, the notes of the motif fit into the scale of E melodic minor.

These and other interpretations are possible, and nobody can definitely state what Coltrane was thinking.

However, Mornington Lockett has suggested that the motif could imply several of the altered tensions over the chord of Eb 7. All the notes of the motif fit into the Eb altered scale. Remember that the altered scale is the same as the melodic minor scale a semitone up, and so just as the motif fits into E melodic minor scale, it fits into the Eb altered scale

This is possibly the most practical use of this shape for jazz improvisers, as dominant seventh chords are extremely common in jazz harmony.

If we look at this motif in its historical context, there are several interesting things about it. The first is that we can see the late Michael Brecker, a celebrated saxophonist and devotee of John Coltrane's music, using an identical shape in bar 92 of his solo on the piece Pools by the jazz fusion group Steps Ahead.

The brackets indicate the relevant segment; we can see that it is simply a transposed version of the original Brecker construction. This pattern is well known and attributed

to Brecker. On his website, Mornington Lockett refers to a version of this pattern as a classic Michael Brecker construction.

The relationship between Breckers pattern and the motif by Coltrane is clear. It seems very likely that Brecker, who is known to have transcribed a great deal of Coltrane's music, heard this motif (perhaps subconsciously) and created his version of it.

This is a very exciting discovery, and it surely demonstrates how artists as great as Brecker are very much influenced by their own heroes, just like the novice jazz musician.

Use of Triad Pairs

The use of triad pairs is well documented in jazz. Several books exclusively cover this topic, such as Walt Weiskopfs Intervallic Improvisation: The Modern Sound and

Gary Campbells Triad Pairs for Jazz. The most common technique is to alternate the use of two triads, creating a hexatonic (six note) scale.

However, as Jason Lynn states in his article on the technique, in order for this approach to yield a hexatonic (six note) scale, the two triads must be mutually exclusive they must contain no common tones.

This technique can create some very interesting colors of tonality. Below we see how two major triads (the most common pairing of triads) can produce, on a major

chord, a Lydian or #11 sound.

Similarly, over a dominant 7th chord, two major triads can produce the sound of a suspended 4th, or, as it would be known to jazz musicians, a sus chord.

In Coltrane's cadenza on I Want to Talk About You we can clearly see his use of this technique.

Here we see the alternating of E minor triad and F major triad along with C augmented triad and Bb diminished triad.

Since Coltrane is not playing over a fixed chord sequence at this point, it is harder to decipher what tonality this triad pair implies.

The most obvious would be that of C major with a #11, i.e. the church mode of C Lydian. Because a diatonic scale cannot contain 3 semitones next to one another, the missing seventh note from the hexatonic must be D, as either Db or D# would result in a non-diatonic scale.

This would indicate that the tonality implied must be that of one of the church modes of C.

However, as we will see by Coltrane's use of synthetic scales, there is no need for us to be bound to the conventions of diatonic scales in our analysis of his music.

In this example, the triad pairs are not mutually exclusive, and so together create a pentatonic scale rather than a hexatonic. This pentatonic is very interesting and could

be used to describe several advanced jazz harmonic sounds.

This is perhaps one of the most attractive of its possible manifestations. In the context of a C7 chord, the pentatonic contains two altered tensions that are found in the altered

scale that were covered in the first section of this essay. These are the b2 and #5 (Db and G#).

In addition, the natural 3rd (E) and flattened 7th (Bb) mean that the chord's function is not obscured, the scale only colors it. This is a prime example of how the analysis of Coltrane's cadenza can produce material that is suitable for

improvisers to absorb into their melodic and harmonic vocabulary.

Use of Synthetic Scales

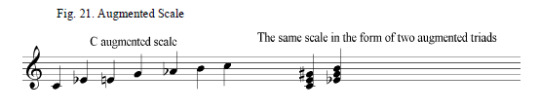

Synthetic scales can be defined as non-diatonic scales, i.e. scales that are not modes of the major, harmonic major, harmonic minor or melodic minor scales. Examples of

these are the whole-tone scale and the diminished scale. Classical musicians may know these same scales as Messiaens 1st and 2nd modes of limited transposition.

Another example of a synthetic scale is the augmented scale. This is constructed of alternating minor thirds and semitones to form a six note scale (hexatonic). It can also

be thought of as two augmented triads a semitone apart and so another example of the technique of triad pairs that has already been noted.

If the order of intervals is reversed so that the scale is now formed by repeating semitone-minor third, this new scale is called the inverted augmented scale.

The following extract can be analyzed and shown to be an example of Coltrane using the inverted augmented scale.

Further analysis can give an indication of the tonalities that Coltrane is implying in this phrase.

This shows how the shape of the augmented scale can be used to outline an augmented tonality, i.e. a chord containing a #5.

One might say that we cannot be sure that Coltrane was thinking of this exact scale when improvising this extract.

However, there is good evidence that the saxophonist

was very familiar with this synthetic scale. In the book, The Augmented Scale in Jazz, Walt Weiskopf and Ramon Ricker admit that in examining improvised solos it appears to the authors that most soloists have used augmented scales and triads in an intuitive manner. It is doubtful that many of the players cited in this book have systematically tried to codify their use of this material.

However, they go on to say that two players that might be an exception to this speculation are John Coltrane and

Michael Brecker.

The clearest indicator of Coltrane's familiarity with the augmented scale is his use of it in his composition One Down, One Up. This piece has a form of AABA and is comparable with Miles Davis composition So What in its use of only two chords each A section is Bb 7#5 throughout and likewise each B section is composed only ofAb 7#5.

As shown below, this extract from One Down, One Up contains all but one notes of the inverted augmented scale, and includes no tones extraneous to that scale.

Given that this melody was pre-composed and thought-out carefully, we can be almost certain that Coltrane was thinking of an augmented scale as the basis for his

melodic material.

Therefore, we can be confident that the examples of augmented scale material in the cadenza were intentional by the saxophonist.

Use of the Three-Tonic Cycle

To jazz musicians, John Coltrane's most infamous composition is surely Giant Steps.

This piece is well-known for being a minefield for improvisers, who are often tested on their ability to successfully navigate the treacherous chord changes. In Giant Steps, instead of following most common jazz standards which modulate generally round the cycle of fourths or in tone and semitone shifts, Coltrane takes the major third as the basic for his harmonic movement.

A number of common standards did contain elements of this kind of modulation, such as Rodgers and Harts Have you Met Miss Jones.

As we can see, the initial tonal center of B moves down a minor third to G by way of a traditional II-V-I cadence, typical of jazz harmony.

Notably, in the 6th bar of this bridge the direction of the major third cycle changes, and the Eb tonal centre rises to

G instead of going down to B.

In Giant Steps, Coltrane took this technique to new extremes by using several patterns of modulation to traverse the chord sequence. He made frequent use of the technique of prefixing each new tonic center with its respective II-V cadence, or at least its dominant.

from Giant Steps

In the extract notated below, we can see evidence of Coltrane using this system of modulation by major third in his improvisation.

At normal speed, this section sounds extremely chaotic, but on closer inspection, there is definite pattern in Coltrane's use of repeating shapes.

In the above analysis of the key passage from the middle of the extract, Mornington Lockett, an expert on Coltrane's work, has identified the tonalities that Coltrane is

implying.

We should keep in mind that Gb major is the relative major of Eb minor, and so for the purposes of this analysis we can treat them as indicative of the same general tonality.

Therefore, we can state that the sequence of key centers inside the square brackets is B minor Eb minor G minor Eb minor G minor.

These three centers (B, Eb and G) form an augmented triad, as they are each a major third away from each other.

Read the full article

0 notes

Photo

Charlie Parker at 100: the Sound and the Myth

This speculative essay by J. D. Considine traces the personal and musical history of Charlie Parker and his various lifestyle and musical influences on future generations. The conclusion, a quote from Vincent Herring, says it all: “The music continues to evolve, and regardless of where it goes, Charlie Parker will always be one of the cornerstones of the music.”

-Michael Cuscuna

Read from DownBeat…

Follow: Mosaic Records Facebook Tumblr Twitter

#Charlie Parker#classic jazz#saxophone#Pannonica#Greg Osby#Steve Coleman#JD Considine#Stanley Crouch#Kansas City#Rudresh Mahanthappa#Grace Kelly#Ira Gitler#Wayne Shorter#Thelonious Monk#Michael Cuscuna

21 notes

·

View notes

Link

via 21st Century Jazz Composers

Dexter Gordon - Where Are You (1962)

From Ira Gitler’s original liners:

This session was not recorded in a nightclub performance, but in its informal symmetry, it matches the relaxed atmosphere that the best of those made in that manner engender. Everyone was really together, in all the most positive meanings of that word. It was so good that Blue Note put these four men in the studio again, two days later. We’ll be hearing that one in the near future.

While my wife is no jazz aficionado, she likes what she likes, and tonight she stopped everything to find out who was playing this ballad.

0 notes

Photo

AllMusic Staff Pick:

Webster Young

For Lady

While trumpeter Webster Young pays tribute to Billie Holiday on this, his only studio date as a leader, the set is equally a tribute to Young's musical role model, Miles Davis. Young has Miles' soft-focus tone from the early to mid-'50s and, according to Ira Gitler's liner notes, he is actually playing Miles' cornet on the date. The similarities between the two players make this 1957 session a satisfying companion to Miles' work circa 1951-1953.

- Jim Todd

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Miles Davis Quintet – Relaxin' With The Miles Davis Quintet #Prestige 1958 🇺🇸 US Mono (2nd) Bass – #PaulChambers Drums – #PhillyJoeJones Liner Notes – Ira Gitler Piano – #RedGarland Recorded By – #RudyVanGelder Supervised By – Bob Weinstock Tenor Saxophone – #JohnColtrane Trumpet – #MilesDavis https://www.instagram.com/p/CEBouoCJ7El/?igshid=3dz8a7ok611m

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chet Baker - My Funny Valentine

My Funny Valentine was a signature tune for Chet Baker. It was composed by Richard Rogers for the musical Babes in Arms in 1937. The Gerry Mulligan Quartet version featuring Chet Baker has been recognised as a culturally significant audio legacy by the US Library of Congress.

Chet was one of the poster boys for west coast cool jazz, even though he hailed from Oklahoma. His early career had huge promise, however heroin addiction derailed that promise and the 60s were turbulent for him. He has been called The James Dean of Jazz

During most of the 1960s, Baker played flügelhorn which has a much mellower sound than trumpet, and works perfectly with cool jazz. Apparently his trumpet was stolen from the Le Chat Qui Pêche, and a friend loaned him a flügelhorn. In an 1964 interview with Ira Gitler of Downbeat magazine he talked about how hard it was to adapt from trumpet to flügelhorn.

“Playing this flügelhorn,” he said and paused, “It’s so hard to play, you wouldn’t believe it. Nobody would, unless it was somebody who plays one. The mouthpiece is deeper and wider, and it takes so much air to fill out this horn. You were there at the date. If I had been playing steadily, right up to the time of the date, I could have gone through that eight or 10 times without getting tired ... . Playing that tune—and it only goes up to high C—if you’re not playing steadily, you can’t make it. After a couple of times, you’re finished.”

He obviously adapted because after 18 months he said he had given up the trumpet.

In ‘66 he was attacked by a group of men, which resulted in him breaking a tooth and ruining his his embouchure, leaving him unable to play trumpet or flügelhorn. He spent years developing a new embouchure and made his way back to jazz, though his later performances were hit and miss.

Today’s track is a live performance of My Funny Valentine from the 1954 album Love Songs. You’ll notice that unlike Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker who would play identical melody lines in unison, Baker and Mulligan complement each other with counterpoint and anticipating what the other will play next.

My Funny Valentine - Live – Chet Baker, Gerry Mulligan

Bozzie – 🎷

1 note

·

View note

Text

Blue Haze by Miles Davis

Up to the time of the Newport Jazz Festival of 1955, Miles Davis was bidding fair to become the forgotten man of 1955 just as he had been in 1954. A chance appearance on the Festival's final night, as part of an all-star group, woke the slumbering critics suddenly. They couldn't say enough in praise of Miles. I thought he had played well but not fantastically enough to awaken the writers who had snored through '54 while he made many excellent records.

Here, in this collection, is proof that it was not Miles who made a comeback at Newport but rather the men of the fourth estate. Why he was so good, he even awakened the talent scavengers.

WHEN LIGHTS ARE LOW is a delicate solo by Miles at medium tempo. John Lewis contributes a thoughtful chorus between Miles opening and close.

TUNE UP is a Davis original with a long string of exhilarating choruses by Miles. After John solos, Miles and Max trade "fours".

MILES AHEAD is another original by Miles. Based on the changes of MILESTONES, it features the same format as TUNE UP with the exchanges between Miles and Max especially interesting. John's comping underlines and punctuates beautifully.

SMOOCH was composed by Charlie Mingus and because John Lewis was forced to leave because of an emergency, the composer had the opportunity to assist in the playing of his piece. Miles solos throughout, conveying the haunting mood perfectly.

FOUR, written by Miles, shows his certain 'something wonder- fully in both its theme and his solo. Horace Silver who would swing even if he was trying not to, has a sparkling solo here.

OLD DEVIL MOON is a tune of a number of years back which Miles seems to have revived. Since his recording, both Sarah Vaughan and Carmen McRae have also done it. The stopping and then swinging is most effective as Miles romps with Art Blakey adding timely comments with his sticks.

BLUE HAZE could be easily subtitled "When Lights Are Out" for that was the situation in the studio when this was made. Only the light from the control room shed slight illumination. The blues mood was aided greatly as everyone relaxed in the haze. Percy sets the pace and then Miles takes an extended set of choruses. Horace has a short but moving solo before Miles closes it out.

I'LL REMEMBER APRIL is rendered at up tempo with two choruses each by a muted Miles, Horace, and Davy Schildkraut. Horace comes back for another and then the rhythm section comes to the fore with Kenny's impeccable brushwork outstanding and Percy's rock of a beat a joy to hear.

notes by IRA GITLER

Notes reproduced from the original album liner.

1 note

·

View note

Quote

I wanted to shine light on that space of reading before the music commenced, when I turned certain albums over and found narratives that were more than historical or documentary but rather poetic and meditative. I don’t mean they flowed lyrically, although many did that, too. What I mean is that they tried to put language to something that did not exist in language, and I wanted to say, as a reader of these notes, you could see the bridgework, the architectures of listening. Writers like Ralph Ellison (in his many essays on jazz) and Nat Hentoff and Ira Gitler (both proliferative liner-notes writers) wrote about jazz as if it were alive, as if it had layers of skin that could be lifted to reach other, more integral parts of the experience. You had to put yourself in a state to try to say something about jazz—what it did to you, where you went—but you were also trying to situate the players and tunes in a particular session. I wanted to write about that writing into the invisible. And to say how it was a kind of trying that never actually brought the music forth but that opened up something in language itself: made language more like music.

Renee Gladman in The Paris Review. Liner Notes: A Way into the Invisible

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

1323 Sonny Rollins legend refreshed in Saxophone Colossus doc! VIDEO INTERVIEW

1323 Sonny Rollins legend refreshed in Saxophone Colossus doc! VIDEO INTERVIEW

Today’s Guest: TODAY’S GUEST: Robert Mugge, filmmaker, Saxophone Colossus, featuring Sonny Rollins

Watch this exclusive Mr. Media interview with ROBERT MUGGE by clicking on the video player above!

Mr. Media is recorded live before a studio audience full of finger snappers and toe tappers who can talk – unconvincingly – for hours about the meaning of jazz … in the NEW new media capital of the…

View On WordPress

#Alfie#Bob Cranshaw#Channel 4 Television#Clifton Andersone#documentaries#Documentary#Duke Ellington#Francis Davis#Gary Giddins#Heikki Sarmanto#Ira Gitler#jazz musicians#Jazz Times#John Coltrane#Lucille Rollins#Mark Soskin#Marvin "Smitty” Smith#Opus 40#Robert Mugge#RUBÉN BLADES#sax players#Saxophone Colossus#saxophonists#Sonny Rollins#Tokyo Koseinenkin Hall#Yomiuri Nippon Symphony Orchestra#Yomiuri Shimbun

0 notes

Photo

Coltrane’s breakout year, when his mature sound first grabbed ears and his own recordings began to sell consistently, was 1958. This release chronicles the exciting story session by session, featuring all 37 tracks Coltrane recorded as a leader or co-leader for the independent Prestige Records label in those twelve months. This collection captures him in creative high gear—developing the signature improvisational style that journalist Ira Gitler famously dubbed “sheets of sound.”

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I’ve just learnt of Ira Gitler’s passing. Although much has been said about his career as a jazz critic and producer, one fact failed to be mentioned because it’s so blatantly obvious— with a few others, he was the creator, the architect and pioneer of a whole writing genre : the jazz liner notes.

Because of his proximity with the musicians and critical flair, every one of his comment was relevant. In this respect, his contribution to the history of jazz is huge and his work is here to stay. He was a funny writer, a major story-teller and a cultural beacon.

I’m glad I got to spend some meaningful time with him in Foix, in the French Pyrénées in 2010, a festival that we were both reviewing for Jazz Hot and DownBeat. Significantly, we were able to listen to music together: Charles McPherson, Kenny Barron, Curtis Fuller, Charles Davis… He was someone who would share his knowledge, delight with his tales, inspire with his insight. Jazz writing at its best.

So long, Ira.

5 notes

·

View notes