#it’s an ingrained part of her antisocial past

Text

the progression of heeseung’s contact name in y/n’s phone:

heeseung (old friend) -> heeseung (friend) -> heeseung (best friend)

their development👏👏👏

#y/n is so dry with contact names#but it’s a detail I love about her character lol#it’s an ingrained part of her antisocial past#ri rambles🕊#fun facts & spoilers🔎

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

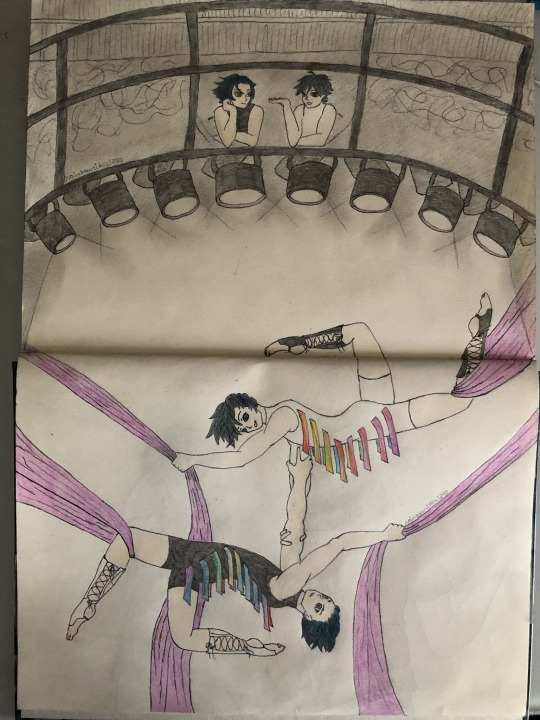

Expanded for my circus AU! Xiao and Venti backstory below the cut!

I think Xiao would've started as part of a rhythmic gymnastics team with the other yakshas. Things Go Down and the yakshas split up. Xiao's always been a part of this whole that they had, so Zhongli encourages him to go solo, which he does. His performances are technically flawless. He'll pull off moves no one else dares to attempt as a gymnast. But like. He doesn't care about it. Doesn't care for much of anything anymore.

On the other end, Venti retired early from performing. His nameless bard friend died and never really coped with it properly, so there was one performance he wasn't really focused on due to this weighing on him and Things Go Wrong. Thus, Venti is injured and retires. He recovers from the injury but fell into this hole where he feels like he doesn't deserve to get back up there and be happy and successful while his friend is dead and he (to himself) messed up so terribly.

Enter Aether and Lumine.

Aether sees how Xiao's face immediately drops when he finishes a performance, how his injuries are... not untended but he definitely rests for less time than he's supposed to and the strain on his muscles and joints is now chronic pain. He communicates this to Lumine.

Lumine knows of Venti from the time she and Aether spent apart and one of the circuses she was at did a couple clinics with him. She's witnessed his performances and knows about why he retired. She finds him with a bottle in his hand and despair on his face outside of the theatre they're performing at one night. He'd come to see a show bc he missed the whole scene and couldn't stay away.

They end up having a talk and Lumine gets an idea. She tells him that they have a performer who's lost the passion and maybe he can say something to inspire them. As a mentor.

Venti's hesitant about it but ends up agreeing after telling her that he has no intention of coming out of retirement. Maybe it'll make him feel useful.

So she takes Venti backstage, Aether whispers an "is that who I think it is" and so they find Xiao.

The conversation is... a trainwreck to say the least. Venti's all fake smiles and empty words about flowery passion and Xiao sees straight through it so he shows no sign of interest in the conversation, which ends with Xiao leaving with a half-assed comment on having to go stretch and cool down.

Lumine had a feeling it'd go down like this, but wanted to try anyway. Aether subtly slips into their farewell conversation that the twins work late today so the rehearsal space will be open until super duper late.

So Venti leaves with plans to go to a bar and wander until someone kicks him out, but before he leaves, curiosity gets the better of him. He goes to the rehearsal space just to see what he's been missing out on and maybe breathe in the worn ropes again. He gets there and What A Coincidence! Some aerial silks are set up. Warm-ups for other gymnast-type performers or the like.

Even through the blur of the tears he finds himself in front of the silks, sobered up a little by now.

With one quick peek around and probs zero regard for his safety, he gets on and performs one of his routines. The movements are still ingrained into his muscles and carved into his bones. He feels his heart start to beat again. Like this is the first time he's breathed in years.

He finishes the performance and the colours around him start to dim again. He breaks down crying and What A Day For Coincidences This Is!! Xiao caught the back half of his performance, and for a moment he forgot about everything weighing him down. For those few minutes, the pain in his muscles became a dull ache, his joints felt good as new, and he felt like he'd soar were his feet to leave the ground in that instant. Like someone injected purpose into his veins again. At the breakdown he understood that this was someone like him. Someone who was being cut apart by the jagged pieces of an identity in disarray.

So Xiao comes out once Venti's calmed down and they have a heart to heart along the lines of "it hurts doesn't it?" And they talk about feeling like something that was once like breathing feels unreachable now and lost purposes.

Venti ends up suggesting that Xiao try aerial performance, thinking that he may be past his prime but that maybe he can help someone fly again.

Xiao agrees but only after a lot of pushing, and still dazed from feeling that sense of purpose again.

They end up spending all night in that rehearsal space and by the time the sun's coming up, Aether and Lumine are in there watching them cooperate and exchange a little high-five.

Venti joins the circus exclusively as Xiao's coach. He makes Xiao stretch more and forces him to take care of himself (insert team bonding shenanigans here to get him away from the workplace) but there's still something missing in his performances. His technique in anything Venti choreographs for him is as flawless as it can be at his level, and the transitions are smooth and tasteful, but there's still something lacklustre.

It's that trust in someone else. As antisocial as he may be, Xiao was cultivated in a team setting, so Venti suggests that he keep training with the silks (which he's picking up surprisingly fast bc it's Xiao) as he gets back into shape. Xiao notices this and helps him without knowing what Venti has planned. By "help" I mean throw a bucket of water on him at 6am like "rise and shine we're going on a run".

After a while of this, Venti has a team exercise in mind. They choreograph a routine and perform it together. Something about strengthening your own skills in trusting someone else. By then Xiao's proficient, and Venti is back in shape.

When they perform their routine, it's rusty, uncoordinated, and needs a lot of polishing, but Xiao's smiling and Venti can't hold the giggle that escapes him.

Venti calls Aether and Lumine over to see Xiao's progress with his other solo routine (which is now a lot better than before), Venti offhandedly mentions that they've been doing practice pair routines and it's really helped his energy and why are you two looking at me like that.

The twins are curious about the training exercise, obviously only to make sure they're safe and they aren't straining the silks too much (Venti assures them they aren't bc he would know) and to see if they can apply this method to some of their other solo performers.

Before Xiao and Venti know it, they're being told to polish the routine bc next show they're opening with that.

They're terrified and convince them to at least hold off bc there's so much to polish (and to emotionally prepare themselves), but overall they come to the agreement that they don't mind the arrangement.

At which point the two realize that Aether and Lumine's names may as well have been Coincidence 1 and Coincidence 2 from the very first night.

They help each other process their respective traumas. Xiao helps Venti on those days he feels like he can't process the day without alcohol, and Venti drags Xiao out of the rehearsal space on the days he feels cripplingly alone, and slowly, they become part of something amazing.

#genshin impact#genshin impact au#genshin impact circus au#genshin circus au#circus au#genshin impact xiao#genshin impact venti#genshin impact aether#genshin impact lumine#genshin headcanons#genshin au#genshin impact headcanons#xiaoven can be seen as platonic or romantic#I am an avid xiaoven shipper but I also like them as platonic teammates with a super deep bond#my art#genshin impact fanart#genshin impact fan art#fan art#fanart#xiaoven#not me realizing reading this back that this is basically the plot of yoi if Victor and Yuuri switched roles

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part of the thing with oppression olympics is that I feel like it's part of a middle class white female social dynamic that I experienced that's practically ingrained from early on.

We're not supposed to own our own achievements and yet at the same time when we do achieve we are under tremendous pressure to prove that our achievement was made by ourselves with no help from anyone else whatsoever, but end up caught in a no win scenario because we're not supposed to do that either. (I feel like this is disproportionately asked of people who aren't white cis het middle class men, to some degree or another.)

If we feel good about ourselves, and own our skills and abilities, we're hated by other women - and especially by the couple of women who we're invariably pitted against in the career space. The behaviors for "getting ahead" (self promotion) are actually forbidden social behaviors for women in most social contexts.

We're often taught to play shit down from day one so that other people don't resent us.

We get examples from day one that rich, successful, or powerful women are evil and antisocial in special ways that the equivalent men are not. A woman born with lots of specific advantages is under even more pressure to prove that she started from square one as if she had none, and things end up framed as special privileges that are never framed as privileges for men. The man who joins a family trade often invokes "awwww" images of father and young son working on cars and spending time together. If a woman gets mentored into a field by her family it becomes "daddy got her the job."

But the thing is, you will never, EVER debase yourself enough. You will NEVER be small enough or deserving enough!! Not until you're ground down into paste! I wish someone had told me that early on but even my own mother believed this shit!!!

Any woman who had that help in any way, who had local support women don't commonly get, and didn't jump through a bunch of arbitrary hoops that should never have been there in the first place, is seen as more privileged and there is a thing of "fairness" expected of women that isn't put on men to the same degree. Men are allowed to win as individuals.

And beneath all of this, a very successful man is often framed as a greater social good by both the left and the right, though the specifics of this framing will vary. But successful women - unless the woman has some kind of "against the odds" inspiration porn success story - are framed as basically stealing food from needier people's mouths and attention away from children and elders, even if none of these people exist in the woman's life except as an ideological construct. And the woman is expected to frame her success story so often in terms of "I found out the corporate life wasn't all it's made out to be teehee and now I'm fulfilled." (Left and right make the same demands, they just frame them differently.)

The successful man is expected or assumed to be feeding a family - or to be eventually feeding a family. But a successful woman is often assumed to be keeping her money to herself. (For what it's worth, I feel like successful childless, single men are judged worse than family men as well, and my ex husband after years and years at the same job wasn't offered bonuses or promotions before he got married. But it's also assumed that a young male professional's success will *eventually* benefit other people.)

The right says that successful women take jobs away from men and attention away from the family, the left says that successful women take opportunities away from other women and their own attention away from their broader community, and both sides say that successful women are a net loss to society as a whole in ways that are less true of successful men. And the left also conflates trying to survive "late capitalism" with being a perpetrator of it.

If we get ahead it has to be the specific narrow way that's also used on women as an obedience proxy (in many cases, where the same job requires much more education for women than it does for men, so it doesn't in fact require that level of education at all for the performance of the job.) And feminist women, and *especially* lots of professional women. They worked harder to get where they are than a man has to work, and they resent any women who appear to have more advantages at the starting gate.

(this is a dynamic that happens with lots of marginalized people when navigating a world where some other group has power over, so maybe it's not specifically a white female middle class dynamic).

But the thing is, we have to be heroic stories of self-sufficiency that men don't have to be, then we're hated for doing it.

There was lots of discourse around my not deserving to work in tech because I had the skills via family business and got started really really young, WHICH IS A NORMAL WAY THAT MEN ENTER WORK FIELDS (and is even romanticized), and like I was a more privileged person taking space from supposedly less privileged women who'd worked harder.

(Because there is a mind-twisting way that an upper middle class/rich reared woman with a degree from Stanford can be framed as less privileged than a lower middle class woman whose parents came from poor backgrounds and were still clawing their way out, who started working as a teenager.)

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you think of 'The Psychology of Azula' video that came out recently?

Sorry this response took so long but like I had to watch the video and really wanted to put thought into it. More under the cut because this ended up being five google doc pages long.

I definitely agree with the first part where the narrator says that Azula’s psychology is the result of a broken family and poor parental upbringing.

But I do disagree with the sadism bit. I’ve typed about this many, many times. I feel like there was really only one time that sadism could be argued and that was when she smiled at the burning of Zuko’s face. But beyond that, I feel like sadism is not a part of her character. As I’ve typed prior, she has done many, many things (including the coup and stopping a senseless torture at the boiling rock) to dispute this.

I also disagree with the Azula always lies bit. I do think that she lies and deceives a fair bit, but I also think that she has a tendency to be very brutally honest.

But I do like his assessment that she is a machiavellian rather than a psychopath. I never really saw her as a psychopath per-say. I always thought that she has trouble functioning in social situations. But I also always felt as though psychopath wasn’t quite the right term though I couldn’t put my finger on it. And as the narrator said, she doesn’t display impulsiveness and such.

I also thought that it was interesting when he started talking about how she has trouble interpreting people genuinely reaching out. The way I took that was that Azula is so used to showing false sympathy and displaying certain feelings to suit a purpose that she assumes others do the same thing and so it’s harder for her to be compassionate and understanding.

Moving on to part two. I agree with him saying that she has antisocial personality disorder. It is kind of similar (imo) to psychopathy, but it isn’t the same. But I still highly disagree with saying that she has a high level of sadism. However when he moves on to say that she’s a narcissist, I can agree with that. I can see that being as she is her father’s favorite and a princess. In some sense, she has almost be raised and predisposed to this disorder. And as he mentioned, it’s reinforced by the friends she has chosen and by her father and by her own need to believe it. That last facet is particularly interesting to me because it highlights some insecurity on her end. Which the narrator ends up touching on.

On that note, I also highly agree with the paradoxal, ‘significant impairment in self-functioning’. I’ve discussed this in the past as well; she has very high standards for herself, higher than those she has for others. And along with it, she longs for the approval of others. Like, she has this bizzare sort of sense of self worth. On one hand she does kind of display narcissistic traits but she also has so much insecurity that she needs the approval of others, her father in particular. I like that the narrator points out that it stems from a natural human desire for intimacy AS WELL AS her “detached need for superficial status.” I agree with him when he begins discussing how the fact that she is not on equal footing with her father, that he is one of the few people she sees as above her, contributes to why she so yearns for his approval and love.

In general I like how he has linked power dynamics into how she forms her desire for love and approval. Though I, myself, would like to say that, by the end of the series, I think that she starts to develop a desire for love with people like her mother and Mai and TyLee like the kind she has for her father. Possibly because, at that point she is so broken that she might see herself as inferior. Which is something that would really destroy her. But it would make sense considering how entrenched perfectionism is ingrained within her. By the end of the show, she is so very far from perfection, I can see her almost craving approval wherever she can get it since she can no longer get it from herself.

As he goes on to say, she uses manipulation and undermining to try to make herself become “the most beautiful and smartest girl in the room”. I think that this is a means of protecting her ego and helping herself to feel the sense of security and perfection she craves. Which brings me back to my headcanon that Azula is very highly insecure, hence why she craves perfection and has to be better than everyone else. Which is why she takes it so hard when people are better than her at some things.

Come part three. Right off the bat I agree with the narrator in that she views even the most simplicit social interactions as combative; I have typed about this elsewhere as well. “To lose something is a moral failure of shame and humiliation.” To me this stands out and and once again highlights a deeper insecurity. That even losing a game in good fun makes her feel awful and shamed. It roots back to her perfectionism.

“Though played as a joke, Azula has never had to moderate her behavior in this way before.” Is another interesting point. One of the reasons she struggles to interact socially on the beach goes back to the power-dynamic thing that he mentioned prior. She is more or less on equal(ish) footing with everyone else so she longs for a different type of approval again. Plus that kind of moderation is foreign to her, she has never really had to put on a different persona for anyone before. And as he says, her usual manipulative tactics can’t earn her the genuine affection she desires in those scenes.

Despite what I said above about her possibly having narcissism or displaying traits of it. I love that this narrator poses that she might not have that disorder at all. That it could be the product of simply being isolated and brought up in a royal environment where she never had to seek that kind of approval. It would simply be because she hasn’t learned how to socialize correctly.

I was also very happy that he tackled the scene where she is talking to Zuko at their old beach house. Like he said, that scene was so important for showcasing that Azula isn’t devoid and bankrupt of empathy. It just, as he put it, doesn’t come naturally to her. As he points out, “there doesn’t seem to be much of a reason for her to purposefully search out her brother.” She has been shown to help him out before, but this is the one true time where there really isn’t anything for her to gain from approaching him. He goes on to mention the “this place is depressing quote.” Which is profound because it is a true moment of empathy. The implication being that Azula harbors some hurt over the past. And for, perhaps, the first time in the series she sees the same hurt on Zuko and empathizes. As he points out, they are completely alone too, so there really is nothing for her to gain from it, even in a social means. I absolutely adore the interpretation, “this is what Azula may be like if they had taken away the pressures of the outside world, of their father.”

I like how he interpreted her suggestion to trash Chan’s party as well. He brought her insecurity to the surface and made her feel inferior so she had to remind everyone and…especially…herself that she was still on top. As well as she needed to get back into her comfort zone both internally and externally.

Part four was very interesting to me as I have dived into talking about her darker psychology before; http://www.fanpop.com/clubs/avatar-the-last-airbender/articles/241344/title/diagnosis-azula

I really like how he pointed out that she was raised to use fear to form relationships. The call to her father’s relationship with Ursa and how it was fear based stood out to me because, though I knew her upbring has so much to do with how she forms relationships, it didn’t quite click that her father and mother literally modeled using fear in place of love right in front of her. Like he said, she has only known love and relationships through fear so it really rattled her to see love overpowering that fear.

Once again going back to her insecurity, Mai choosing love over fear and Zuko over her left her feeling foreginly weak and venerable. It pretty much rocked her entier feeling of security and self-image. Which, to me explains her lashing out in a way that I hadn’t considered prior to the video.

That was the perfect segway into her losing her grip. Like the narrator says, “if Mai and TyLee can betray her, anyone can.” And so we get into the interpretive delusions. I found it particularly interesting when he noted that she even accused her own body of conspiring against her instead of admitting that fear and control weren’t the way to go.

I also absolutely loved how he highlighted the, “you always had such beautiful hair line.” Now that he mentioned it, I pay more attention to it. At first I just thought that it was a segway into the next thing hallucination Ursa was going to say, an icebreaker so to speak. But it is so much more, as the narrator says, her perfection was always tied into and alluded to with her perfectly styled hair. Furthermore that the hallucination was brought about by and opened up with that line because it was the first time she really saw herself as physically less than perfect.

I am also so, so happy that he notes that “almost every interaction we see with them (Azula and Ursa) is a critical one.” We see almost nothing in canon where Ursa is being affectionate with Azula. But we see a lot of Ursa scolding her and displaying signs that she doesn’t like Azula’s ambition and power. I like how after this part he draws a parallel between the hallucination scene and the betrayal scene, with love vs fear at the root. How pretty much everything Azula thought to be true is falling apart around her. It really tears her apart because as he said; accepting this would be to accept weakness in herself and there for imperfection. Which circles back into insecurity.

I think that the narrator’s take on diagnosing her with schizophrenia is interesting as well. Though I do stick to my guns in thinking that she has it, I do agree that diagnosing it so early on would be the wrong thing to do. However by the time the comics, that take place years later, roll around the hallucinations are still present, which is well over the 6 months hs of persistence that was mentioned.

The whole bit about the systamisted beliefs is something agree with as well as the delusions of grandeur and control. I’m not going to get to into that because it is something I have already analyzed in that link that I posted above.

I will talk about how I think that his interpretation of S&S is interesting. She claims that she is getting better and that the voices are gone (which is a step in the right direction). But the narrator has a point, the delusion is still very much there in that she is talking about how she was never meant to be fire lord. That the delusion simply evolved and twisted into something even more complex. And I think that it is interesting to note that she is getting her manipulative streak back and losing some of that impulsivity.

I love how he noted the contradictory delusions too. That her mom is both trying to get her on the throne and away from it. This was an eye-opener for me in a way. I always interpreted that scene as Azula just deciding that she wasn’t meant to be Fire Lord. He seems to interpret it as her maintaining the delusion and her mother helping her draw that conclusion. I am not sure if I agree with this yet, and will have to think on it. But I do like the theory.

I do like him bringing up schizoaffective disorder. I believe that I mentioned that one in that link above as well. I also like how he mentions that she displays signs of anxiety and depression.

Part six was great too, because again, I enjoy how he notes that every interaction we have see between Azula and Ursa is negative (particularly, I like how he notes that she overheard her mom asking what was wrong with her). I’ve been saying time and time again that, “this kind of dynamic can be very damaging for a child.” Regardless of how you feel about Azula, it is never good to say something like that in front of your child. I won’t get too much into this one either because I will definitely sound like a broken record. In general I agree with pretty much everything he says in light of her relationship with her parents and how it has shaped Azula into who she is. I like the mentioning of the conflicting parenting style as well and how she gravitated towards Ozai because it was easier to gain affection from him as Ursa’s affection is more rooted in emotion and Ozai’s was more rooted in power. Azula’s strong suit is power not emotion and so she drifted to Ozai because that’s the parenting style that coincided better with her. And again I really like the mention of the conflicting parental styles; that Ursa punishes Azula for things that her father praises her for. So she kind of just stuck to the parental style that was easiest for her to achieve.

Where it gets really interesting to me is when he mentions that Ursa may have been depressed when raising Azula. It makes me sympathize with her, where I hadn’t before. It doesn’t justify or make her neglect of Azula any better but I understand it more and I feel more sympathy should it be true.

Furthermore I like how he mentioned that her attachment to Ozai created a cycle between she and her mother.

I like that he mentions how Azula would lash out for attention as a child as well. To me that, perhaps she acted out not out of sadism but to receive her mother’s attention by any means necessary and the best way to do that was to act out and do something mean.

I absolutely love that he mentions the importance of an intervening parental figure and how Azula was forced to confide in her abuser while Zuko had Iroh. Again I won’t talk too much about this because I mentioned over and over how much of a difference Iroh made in Zuko being able to achieve redemption. I’m just happy to see such an articulate narrator agreeing.

I agree that her story was a tragedy too. And above all else I am so, so thrilled and satisfied that he closes that, “while it is easy to read Azula as an adult she is just 14.” And that Ozai didn’t give her much time to really be a teen girl. Thank you!!! This is what I have been trying to say for ages. Moreover I like how he says that, “Azula’s actions can’t be pegged on anyone but it is important to recognize the impact of abuse.” So, so, so important, and exactly what I’ve been trying to say.

As far as the narration itself goes I was really impressed by the lack of bias. It was a clear cut analysis that seemed to be more rooted in fact-based speculation than emotional attachment (either positive or negative) to Azula’s character. The fandom really needs this imo. It is so split that there is seldom middle ground. And I love how this narrator takes that middle ground. I didn’t feel like he was trying to demonize nor make her out to be a saint. He was just telling things for what they were. I liked that a lot. He has a soothing voice too lol.

Basically this guys is saying everything I’ve been trying to say but he’s managed to explain it in a much more organized way.

I’m not going to lie I almost didn’t answer this ask because I didn’t feel like watching such a long video. But I’m glad I did. Thanks so much for the ask and recommending the video!

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Podcast: What is Schadenfreude?

We’ve all experienced it – that feeling of smug happiness at another person’s misfortune. From someone slipping on a banana peel to a jerk receiving a dose of instant karma, there’s something satisfying about this strange emotion. Why is that? Are we living in an “Age of Schadenfreude”? Should we feel guilty about feeling it? And for crying out loud, how do we say it in English? Listen in to find out!

Subscribe to Our Show! And Remember to Review Us!

About Our Guest

Dr. Tiffany Watt Smith is a cultural historian and author of The Book of Human Emotions. In 2014, she was named a BBC New Generation Thinker, and her TED talk The History of Emotions has over 1.5 million views. She is currently a Wellcome Trust research fellow at the Centre for the History of the Emotions at Queen Mary University of London. In her previous career, she was a theater director. Her latest book, SCHADENFREUDE: The Joy of Another’s Misfortunes is available for purchase.

TOXIC RELATIONSHIPS SHOW TRANSCRIPT

Editor’s Note: Please be mindful that this transcript has been computer generated and therefore may contain inaccuracies and grammar errors. Thank you.

Narrator 1: Welcome to the Psych Central show, where each episode presents an in-depth look at issues from the field of psychology and mental health – with host Gabe Howard and co-host Vincent M. Wales.

Gabe Howard: Hello everyone and welcome to this week’s episode of the Psych Central Show podcast. My name is Gabe Howard and with me as always is Vincent M. Wales. And today we have a great guest all the way from the U.K. We’re fairly certain that this is our first guest who actually lives in… is it England? Can we say England or do we have to say U.K.? It shows you how well travelled I am.

Tiffany Watt Smith: You can say… I’m in London, you can say England or U.K.

Gabe Howard: Wonderful. I have heard of London, so I feel very good… but before we move much smurther… Ugh. Let me start that over… But before we go much smur… [Laughter from guest and co-host.]

Vincent M. Wales: Am I experiencing schadenfreude?

Gabe Howard: Oh, man… Yes! We did that on purpose, everyone, so that I could introduce Dr. Tiffany Watt Smith. She’s a senior research fellow at the Queen Mary University of London Centre for History of Emotions and she’s the author of a couple of books, one of which is the Book of Human Emotions and a new book that’s out, Schadenfreude: The Joy of Another’s Misfortune. Right out of the gate, Tiffany, welcome. Thank you so much for being here and…

Tiffany Watt Smith: Thank you for having me.

Gabe Howard: Thanks for mocking my mispronunciation of everything. I want everybody to know that I did that intentionally for illustrator purposes.

Vincent M. Wales: Uh huh. Uh huh. Great. All right, I have to ask this right up front: what exactly is the Centre for the History of Emotions?

Tiffany Watt Smith: Well, we are a group of researchers in London – there’s a few different research groups around the world who look at the history of emotions. But what we look at is how ideas about emotions have changed over time, how different some emotions come into fashion, like boredom in the 19th Century and others sort of drop away so that there are some emotions which used to exist that no longer do. But the main thing we’re really interested in is trying to understand the origins of some of the emotions that we care most about today. So a lot of us look at the histories for example of happiness and the whole wellbeing agenda and we look at the history of anxiety and shame and things like that. I mean look at all kinds of sources whether we’re looking at literature and art or philosophy and medicine to try and understand the way thinking about emotions has changed across time.

Gabe Howard: That is very cool and of course one of the things that you are looking into is the emotion where somebody gains joy when something bad happens to another personm which is referred to as – and I’m going to butcher the wordm I always do – Shroydenfrada.

Vincent M. Wales: You sure did!

Tiffany Watt Smith: Schadenfreude, yeah, again on purpose. Good mispronunciation.

Vincent M. Wales: Yes.

Tiffany Watt Smith: So schadenfreude. Yeah. Literally, “schaden” from harm or damage, and “freude” meaning joy, so “damaged joy.” And it means the glee or quiet smug self-satisfaction that we might feel when witnessing someone else’s accidental misfortune or minor mishap.

Vincent M. Wales: Yeah, we’ve all experienced that and I think a lot of us, immediately following that, experience guilt for feeling that way.

Tiffany Watt Smith: Absolutely. I mean I think that this is one of the reasons why I was so drawn to this topic. I mean not many people write about schadenfreude. Although certainly over the centuries, people have wondered about this emotion. Why do we feel it? What kind of situations do we feel it in? Is it ever morally okay to feel like this? And certainly I think what I found was that schadenfreude is a hugely interesting and often quite paradoxical feeling/emotion because, on the one hand, it seems to be rather possibly spiteful or malicious even, you know sort of enjoying seeing someone who is more successful than you not getting that promotion, enjoying seeing that effortlessly attractive friend getting dumped, you know whatever whatever that thing is. But at the same time, schadenfreude does link in to some of those things that we value most in our human societies. The thing that stands out most to me is justice. One of the reasons why we feel schadenfreude, often, is because we feel that someone’s getting a kind of deserved comeuppance. It’s only fair that they should suffer in some way. So you know someone shoves past you in the queue at the supermarket and then their credit card is declined, or they steal your parking spot and then bang the front of their car. You know, these little things that kind of give us a little jolt of pleasure in our day. I think we think, well, it’s karma. You know, they deserved it. Maybe next time they won’t be so you know… try to get one over on us and so on. So I think the schadenfreude might seem quite antisocial, but actually often when we think about it more, we can understand that is really connected to you know very cherished ideas about justice and fairness, as well.

Gabe Howard: You brought up the word karma. Is this just karma? Is it something more? And is there an English word for this or is it really just schadenfreude. I’m gonna get it right before the end of the show.

Tiffany Watt Smith: There is no English word for this particular pleasure, although over the centuries people have had a go at trying to invent one. So around the 16th Century, someone tried to introduce “epicaricacy,” but that is a real mouthful and that definitely did not catch on because about a hundred years later, you’ve got people saying oh why don’t we did we have a word for this in English?

Gabe Howard: And I can’t pronounce that word either so I’m glad that one didn’t work.

Tiffany Watt Smith: Yeah, that was a terrible ugly word. It comes from the ancient Greeks for this particular feeling. But certainly many other cultures and languages have a word for this, but you better to ask me to pronounce it, because I definitely can’t. But they are in Danish and in French, the Japanese have a saying, a really wonderful saying, that the misfortunes of others taste like honey. So this idea is around in many different languages, but in English I can only assume that over the centuries we’ve found the idea so distasteful and believe that it’s not us that feel like this but any other people, that we’ve just never quite given this a name.

Gabe Howard: It’s interesting that you said only other people feel this way when we’ve all felt this way. I personally felt this way and I consider myself to be a good person. I know that Vin has felt this way and and I will personally vouch that Vin is a good person. But it is sort of a… like you said, people feel guilt about it. What is up with that? Is it just part of our makeup? Is there a biological need to feel this way? Why… you study emotions; why do we have this?

Tiffany Watt Smith: So there’s lots of different questions there, and just to say upfront I absolutely recognize the guilt and the discomfort around it. And even after having spent a long time writing a book about it, in which I was in the situation where I have to confess my terrible schadenfreude crimes, I still feel a certain amount of awkwardness talking about it. So maybe the question about why we might feel guilty about it we can come back to, but there’s certainly lots of reasons why we might feel this emotion and yes, why we might be primed to feel like this. You know I’ve already mentioned about justice and how important it is actually that we enjoy seeing transgressors get some kind of comeuppance and it’s fairly obvious, I think, to assume that you know those pleasures are have been ingrained in us from a very early stage in our social evolution, because human society depends on justice to run smoothly. So it makes sense that we would enjoy seeing transgressors exposed or embarrassed or punished in some way. Again, I think that makes sense in forms of fairness you know when we sense that someone has perhaps got a bigger slice of the cake than we have, you know someone who’s very wealthy or seems to have all the talent or all the lark or you know… and then we see that person sort of not quite get what they want. You know, perhaps get tripped up in some way, that the enviably good looking person in your school gets a huge spot on the day of the dance, something stupid like that. It gives us a little a feeling of you know that the playing field has been leveled again. Things feel a bit fairer. Again, very important for our society to survive, but also important because you know we find ourselves as humans living in groups constantly comparing ourselves to one another, trying to make sure that we are not falling too far behind, and making sure that we can get a good share of the resources and so on. And so in these kind of small, competitive ways, which are completely normal and natural, even if they don’t always feel very pleasant, then schadenfreude does play an important part, because it’s sort of a little moment of recognition that oh yes this person that we were competing with, you know, slightly fallen behind and that makes us feel a little boost that we might be just about getting ahead. I think that kind of completely normal.

Gabe Howard: So it’s like a boost of confidence that maybe pushes us a little further and allows the gap to shorten a little you know from the “we can’t overcome” to “wait, I see a possibility.”

Tiffany Watt Smith: So the pleasure isn’t simply you know ha ha you’ve fallen flat on your face, it’s also a sense of optimism and potential for us, for our thing that we’re trying to get going. One of the areas I think this is really fascinating with actually is in relation to work, in the workplace, there’s so much schadenfreude in the workplace. Particularly, I think, in relation to those who are our superiors you know, our bosses and so on, and there’s nothing sort of more delightful really than seeing that person who wields power over you. you know. experience some minor embarrassments. because it allows us to kind of feel that you know that that sort of possibly not very nice boss. you know. when they have or experience some sort of mishap, it allows us to kind of see a little chink, little glimpse of possibility where we might sort of steal back a tiny bit of power of our own. Psychologically I think that’s very important.

Vincent M. Wales: So basically what you’re saying is that despite this sounding like a rather spiteful and awful emotion to suffer, we might actually get something positive out of it.

Tiffany Watt Smith: I think of course we do get something positive out of it because it is gives us pleasure and that is hugely important. But yes that positivity may actually sort of extend to thinking about ways in which we form more coherent and stable societies, which I think is the unexpected thing about schadenfreude. I think schadenfreude works in all kinds of other ways too. One of the things that found again and again in the research on this emotion is that it really does help bond groups together, and this isn’t unexpected. I think we’ve all seen this example with rival sports teams. You know schadenfreude is you know taking pleasure in you know the own goal of the other side. That’s one way in which a team can really bond together, it’s not just that you put the other side down, it’s also that you laugh together, you feel pleasure together, laughing together is a very bonding and important experience. Now of course that can go too far and it can have quite unpleasant effects, so we can talk about that perhaps in a bit. But we do see schaudenfreude playing this really important role in cohering groups together. Actually, there’s been some research on laughter that suggests that this may have really been a very important mechanism far far back in the evolutionary past. There was a study done at the University of Oxford by Robin Dunbar who’s an evolutionary psychologist. And he was looking all kinds of laughter, but fell on looking at… a sort of belly laughing, you know when you’re laughing so hard that it actually hurts. And it’s only humans that have this kind of laughter. And he found that people only ever laughed like that in response to slapstick. So people falling over, you know, hitting themselves on the head with buckets and so on. And he found that when people laughed like that, then shortly after they were able to withstand much greater pain than they were beforehand or if they laughed in some other way.

Gabe Howard: So The Three Stooges were saving lives. [laughter]

Tiffany Watt Smith: Well this is what he’s suggesting, he’s saying that perhaps this kind of slapstick entertainment has been part of our you know our cultural heritage for a really really long time. And when our distant ancestors were all laughing together around a fire at someone, you know, pretending to get hit on the toe with a hammer, that actually that laughter was important not just because it bonded people into those groups that were crucial for survival, but also because it allowed people to cope in very hostile and dangerous environments where there was a lot of pain. I thought it was really intriguing.

Gabe Howard: We’ll see you in about 30 seconds after these messages from our sponsor.

Narrator 2: This episode is sponsored by BetterHelp.com, secure, convenient and affordable online counselling. All counselors are licensed, accredited professionals. Anything you share is confidential. Schedule secure video or phone sessions, plus chat and text with your therapist whenever you feel it’s needed. A month of online therapy often costs less than a single traditional face-to-face session. Go to BetterHelp.com/PsychCentral and experience seven days of free therapy to see if online counselling is right for you. BetterHelp.com/PsychCentral.

Vincent M. Wales: Welcome back, everyone. We’re here with Dr. Tiffany Watt Smith discussing schadenfreude.

Gabe Howard: I think that comedians for a long time, and even myself, I’m not a comedian, but I do public speaking, and I know that if I make fun of myself, then the audience is more likely to laugh and there’s comedians that have made their whole careers about talking about how they’re bad friends bad, you know, they’re ugly or they’re fat or they’re worthless or they’re pointless or, you know, this self-deprecating humor is just very common in our society. Is that an example of schadenfreuden? Nope… still got it wrong.

Tiffany Watt Smith: I think that that is really one of the most neglected forms of schadenfreude in that when people write about schaudenfreude, they really don’t often talk about this particular phenomenon. And I think this is an example of how we use schadenfreude all the time. I mean, if you start a new job, you know you’ll go into that office or that new group of people and you will tell a self-deprecating story of some terrible disaster that happened to you on the way to work. You know, you do it not just to entertain people, but so that you are seen as less of a threat. You know, that the kind of person who is coming into a new group or is the outsider always seems like a threatening person. So those kind of stories allow people to laugh at you and laugh with you, laugh at your expense, I suppose. And that’s, you know is a way of being accepted into the group as much as it is a way of giving everyone else pleasure. And as you say, you know it’s an absolute staple of standup comedy. Standup comics know that people enjoy hearing about the suffering of other people. And standup gives them a license to enjoy it, I think.

Gabe Howard: And schadenfreude is also an example of the millionaire with the tax problem or the very tall person who bangs his head on the doorway and things like that. These are all little examples of where they have something very desirable, but that desirable thing also has a negative. So maybe it’s like every silver lining has a cloud? Or am I oversimplifying or undersimplifying?

Tiffany Watt Smith: I think one of the things that I found when I was trying to tackle writing this book was that you know this is a very complex emotion. You know there are some emotions which feel like quite simple to think about because it’s a trigger and a response. And it’s kind of one thing you know, scary bear you know your heart rate races and you and you run away. Schadenfreude isn’t quite like that kind of emotion. It’s what psychologists call the cognitive emotion. So a cognitive emotion means that it is involved with appraising and judging a situation and doing all kinds of sort of very fast mental calculations to work out whether someone really deserves it whether it’s really funny or whether in fact this person needs our help, whether they really injured themselves or whether they’ve just sort of suffered some minor embarrassment. Yes, all of these complicated things are going on when we experience schadenfreude. And we experience it in relation to a kind of vast range of different sorts of phenomena or in a vast range of different kind of situations. So sometimes it can be as simple as someone slipping on a banana skin or the Three Stooges. And sometimes it’s to do with you know that seeing someone who we think has behaved really unfairly being called out or lambasted in the media. And yeah and sometimes it is these situations where we feel, you know we almost tell ourselves that, you know there’s a highly desirable trait, you know being very tall, being very glamorous. I don’t know, being very clever or being able to speak twelve languages, you know has in fact got its downside. And this is part of a little trick we will play on ourselves and I’m sure we all do it. You know, a way of just making life’s inevitable unfairnesses that little bit more palatable. It’s not just us that experience difficulty, failure, embarrassment. You know everyone does. And I think that’s what we want to remind ourselves of that, continually.

Vincent M. Wales: I don’t think it should be any surprise to anyone that the schadenfreude is a complex emotion because most emotions are. You think about all the different forms of love that we have. The Greeks had several different names for the different types. So it stands to reason that that this would be in the same category, right?

Tiffany Watt Smith: My last book, The Book of Human Emotions, and I did a TED talk about this as well, makes exactly this argument that it doesn’t really make sense to distinguish between very simple emotions and complex or cognitive emotions because actually all emotions have this very powerful cognitive element and in fact you know even something as simple as apparently simple as fear has a hugely rich history and changes so much across different cultures that actually fear emerges as a very complicated emotion that seems to have very different kind of physical and experiential responses when we feel it. So, yeah, thanks for pulling me up on that because actually, you know I want to make the point that schadenfreude is perhaps more of an appraisal or a judgment-based emotion than some others. But as you say, you know all emotions have this richness and complexity.

Gabe Howard: Now Vince and I are based here in America and I know you live in London, so this might be somewhat of a difficult question to answer just because, you know the different cultures, but we both have the Internet. And when somebody falls down or gets hurt or something bad happens, that video or message will will go viral pretty easily, whereas when somebody does something well or something good, it doesn’t get seen as much and you know, in America we have a lot of unrest as far as you know political parties and race and even you know gender and sexuality. Are we living in the age of schadenfreude? Are we just excited when bad things happen to people that we have dubbed our enemies? And I know that’s a big big question. But it seems like we’re almost searching out for bad things to happen to people. And you know with with Facebook and the Internet it’s easier and easier to find.

Tiffany Watt Smith: Yeah, I mean this phrase “an age of schadenfreude” was again was one of the reasons why I became interested in this topic, because you know when you’re a historian of emotions, you know this kind of phrase you know we’re living in an age of blah blah blah emotion is very tantalizing, you know, what is it about this emotion that makes people feel like it really defines the spirit of their time? And you certainly get over the centuries people saying well you know how in the 18th Century you were living in an age of sympathy. The 19th Century living in an age of boredom. In the early 20th Century, we’re living in an age of anxiety. Anyway now we are living in an age of schadenfreude. I think I do absolutely recognize what you’re describing, which is that sort of apparently insatiable hunger for the spectacle of failure. You know, whether that is or particularly, I think, if that is a politician. But certainly anyone in our sort of disliked you know enemy camp, as it were, and we see that person mess up in some way, there’s a kind of celebration. And celebration seems to be more public than it ever has been. I think there’s two important things to think about. I mean one is obviously that schadenfreude has always been with us. But it is a lot more visible now than it used to be because of the Internet, because of the ways in which we can demonstrate and register our pleasure in likes and shares you know thumbs up and so on. And you know that that would never have been that would just wouldn’t have been possible in the same way, you know even 30 years ago. So in a sense schadenfreude is much more visible than it used to be. But there’s also something about the way in which the Internet works that I think possibly exacerbates our schadenfreude. As I said we’ve spent a lot of schadenfreude when we feel or perceive that someone’s misfortune or mishap is deserved in some way. Now if you spent 10 minutes wandering around your local streets, you’re probably not going to encounter many situations that outrage you. And many examples of terrible injustice being carried out. But if you spend 10 minutes wandering around the internet, you are going to see lots of injustice coming at you. Whether that’s looking at the news, whether that’s looking at even at your local Facebook group with everyone complaining about that slighting or the person who doesn’t pick up their dog poo or whatever it is. You know, so there’s all sorts of unfairnesses and outrage being prompted online. But also it’s much easier for us to register our disapproval, to tell someone off, and to enjoy the spectacle of someone being told off when they’re online than it is in our face to face interactions. Because of course you know if you see someone on the street doing something wrong, you’re unlikely to march up to that person and tell them off and you’re certainly not going to stand there and point and laugh at them if someone else tells them off, because you know you might get punched or, you know you might risk some other kind of social embarrassment. But you know when we’re online, you know we’re completely protected from that. And there’s very little risk in calling someone out and enjoying it. So I think that the Internet I think makes schadenfreude a much more visible. But it also I think creates an environment where we can really let our schadenfreude rip and that is something that I think is really important for us to be aware of. And that’s why I think this emotion is very interesting for us to think about now, and because as you say schadenfreude becomes hugely powerful when we are divided into enemy camps and, you know when we’re we’re in rivalries and these rival groups are set against each other. You know, study after study shows that schadenfreude is very powerful when we’re in groups and very powerful when we’re rivals. And so it’s a very you know it’s a powerful combination of things you know very strong divisions, for example politically as there are here in the UK at the moment certainly. And then also this platform, online platforms, that make it very easy to share and enjoy our glee at the other side’s misfortune. So that was a very long answer to that question. I mean there is another reason why I think that the age of schadenfreude might have caught our attention at moments, and it might be that we’re feeling… I think we are feeling more schadenfreude than before. And I think it’s definitely more visible. But we’re also more anxious about schadenfreude, I think, for the last hundred years there’s really no articles published with the word schadenfreude in the title. But since about the year 2000, there’ve been hundreds published. So there’s a sudden influx of interest amongst psychologists and philosophers and social scientists and so on about schadenfreude. And this real interest comes off the back of you know the surge of interest from the 1990s onwards in empathy. So schadenfreude in this context is presented as the opposite of empathy or the failure of empathy, empathy’s shadow… And so this is a sense why people got quite anxious and worried about schadenfreude. But since empathy is so desirable, what does schadenfreude tell us about ourselves? Now I personally think this opposition between schadenfreude and empathy is problematic and doesn’t quite work. But nonetheless this is one of the reasons why we’ve got so interested in schadenfreude today.

Vincent M. Wales: Well I had a question that you already answered…

Gabe Howard: That’s how good you are!

Vincent M. Wales: Yeah I was going to bring up compassion and empathy and you’ve already touched on that, so great.

Gabe Howard: We really appreciate it.

Vincent M. Wales: And we are probably about out of time, too.

Tiffany Watt Smith: Okay. Oh sorry I just rattled on.

Gabe Howard: No please don’t apologize, it’s fantastic. Thank you so much. We learned so much. I saw a Broadway musical, Avenue Q, where they had a song that had schadenfreude in it and it was you know funny, obviously they explain it for the purpose of humor, not for education. So we’re very excited to have you on this to lend to it because it’s a very popular musical here in the States so I imagine a lot of people have some little bit of information about schadenfreude but not as much as you just gave us. So we really appreciate it. How do we find you? What’s your website, book?

Tiffany Watt Smith: I have a university website so if you just Google my name that will come up. I’m on Twitter.

Gabe Howard: What’s your Twitter handle?

Tiffany Watt Smith: DoctorTiffWattSmith.

Gabe Howard: Beautiful beautiful. And of course your book, is it available on Amazon, where fine books are sold?

Tiffany Watt Smith: I’m sure it’s available anywhere where fine books are sold.

Gabe Howard: Excellent. And you have the two books, what are the name of the two books?

Tiffany Watt Smith: So there The Book of Human Emotions and this one is called Schadenfreude: The Joy of Another’s Misfortune.

Gabe Howard: Wonderful, thank you so much for being here, we really enjoyed having you.

Vincent M. Wales: Yes we did.

Tiffany Watt Smith: Thanks for having me. It’s great to talk to you.

Gabe Howard: You’re very welcome and thank you everybody else for tuning in and remember, you can get one week of free, convenient, affordable, private, online counselling anytime, anywhere by visiting betterhelp.com/PsychCentral. We’ll see everybody next week.

Narrator 1: Thank you for listening to the Psych Central Show. Please rate, review, and subscribe on iTunes or wherever you found this podcast. We encourage you to share our show on social media and with friends and family. Previous episodes can be found at PsychCentral.com/show. PsychCentral.com is the internet’s oldest and largest independent mental health website. Psych Central is overseen by Dr. John Grohol, a mental health expert and one of the pioneering leaders in online mental health. Our host, Gabe Howard, is an award-winning writer and speaker who travels nationally. You can find more information on Gabe at GabeHoward.com. Our co-host, Vincent M. Wales, is a trained suicide prevention crisis counselor and author of several award-winning speculative fiction novels. You can learn more about Vincent at VincentMWales.com. If you have feedback about the show, please email [email protected].

About The Psych Central Show Podcast Hosts

Gabe Howard is an award-winning writer and speaker who lives with bipolar and anxiety disorders. He is also one of the co-hosts of the popular show, A Bipolar, a Schizophrenic, and a Podcast. As a speaker, he travels nationally and is available to make your event stand out. To work with Gabe, please visit his website, gabehoward.com.

Vincent M. Wales is a former suicide prevention counselor who lives with persistent depressive disorder. He is also the author of several award-winning novels and creator of the costumed hero, Dynamistress. Visit his websites at www.vincentmwales.com and www.dynamistress.com.

from World of Psychology https://ift.tt/2T69gGl

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Podcast: What is Schadenfreude?

We’ve all experienced it – that feeling of smug happiness at another person’s misfortune. From someone slipping on a banana peel to a jerk receiving a dose of instant karma, there’s something satisfying about this strange emotion. Why is that? Are we living in an “Age of Schadenfreude”? Should we feel guilty about feeling it? And for crying out loud, how do we say it in English? Listen in to find out!

Subscribe to Our Show! And Remember to Review Us!

About Our Guest

Dr. Tiffany Watt Smith is a cultural historian and author of The Book of Human Emotions. In 2014, she was named a BBC New Generation Thinker, and her TED talk The History of Emotions has over 1.5 million views. She is currently a Wellcome Trust research fellow at the Centre for the History of the Emotions at Queen Mary University of London. In her previous career, she was a theater director. Her latest book, SCHADENFREUDE: The Joy of Another’s Misfortunes is available for purchase.

TOXIC RELATIONSHIPS SHOW TRANSCRIPT

Editor’s Note: Please be mindful that this transcript has been computer generated and therefore may contain inaccuracies and grammar errors. Thank you.

Narrator 1: Welcome to the Psych Central show, where each episode presents an in-depth look at issues from the field of psychology and mental health – with host Gabe Howard and co-host Vincent M. Wales.

Gabe Howard: Hello everyone and welcome to this week’s episode of the Psych Central Show podcast. My name is Gabe Howard and with me as always is Vincent M. Wales. And today we have a great guest all the way from the U.K. We’re fairly certain that this is our first guest who actually lives in… is it England? Can we say England or do we have to say U.K.? It shows you how well travelled I am.

Tiffany Watt Smith: You can say… I’m in London, you can say England or U.K.

Gabe Howard: Wonderful. I have heard of London, so I feel very good… but before we move much smurther… Ugh. Let me start that over… But before we go much smur… [Laughter from guest and co-host.]

Vincent M. Wales: Am I experiencing schadenfreude?

Gabe Howard: Oh, man… Yes! We did that on purpose, everyone, so that I could introduce Dr. Tiffany Watt Smith. She’s a senior research fellow at the Queen Mary University of London Centre for History of Emotions and she’s the author of a couple of books, one of which is the Book of Human Emotions and a new book that’s out, Schadenfreude: The Joy of Another’s Misfortune. Right out of the gate, Tiffany, welcome. Thank you so much for being here and…

Tiffany Watt Smith: Thank you for having me.

Gabe Howard: Thanks for mocking my mispronunciation of everything. I want everybody to know that I did that intentionally for illustrator purposes.

Vincent M. Wales: Uh huh. Uh huh. Great. All right, I have to ask this right up front: what exactly is the Centre for the History of Emotions?

Tiffany Watt Smith: Well, we are a group of researchers in London – there’s a few different research groups around the world who look at the history of emotions. But what we look at is how ideas about emotions have changed over time, how different some emotions come into fashion, like boredom in the 19th Century and others sort of drop away so that there are some emotions which used to exist that no longer do. But the main thing we’re really interested in is trying to understand the origins of some of the emotions that we care most about today. So a lot of us look at the histories for example of happiness and the whole wellbeing agenda and we look at the history of anxiety and shame and things like that. I mean look at all kinds of sources whether we’re looking at literature and art or philosophy and medicine to try and understand the way thinking about emotions has changed across time.

Gabe Howard: That is very cool and of course one of the things that you are looking into is the emotion where somebody gains joy when something bad happens to another personm which is referred to as – and I’m going to butcher the wordm I always do – Shroydenfrada.

Vincent M. Wales: You sure did!

Tiffany Watt Smith: Schadenfreude, yeah, again on purpose. Good mispronunciation.

Vincent M. Wales: Yes.

Tiffany Watt Smith: So schadenfreude. Yeah. Literally, “schaden” from harm or damage, and “freude” meaning joy, so “damaged joy.” And it means the glee or quiet smug self-satisfaction that we might feel when witnessing someone else’s accidental misfortune or minor mishap.

Vincent M. Wales: Yeah, we’ve all experienced that and I think a lot of us, immediately following that, experience guilt for feeling that way.

Tiffany Watt Smith: Absolutely. I mean I think that this is one of the reasons why I was so drawn to this topic. I mean not many people write about schadenfreude. Although certainly over the centuries, people have wondered about this emotion. Why do we feel it? What kind of situations do we feel it in? Is it ever morally okay to feel like this? And certainly I think what I found was that schadenfreude is a hugely interesting and often quite paradoxical feeling/emotion because, on the one hand, it seems to be rather possibly spiteful or malicious even, you know sort of enjoying seeing someone who is more successful than you not getting that promotion, enjoying seeing that effortlessly attractive friend getting dumped, you know whatever whatever that thing is. But at the same time, schadenfreude does link in to some of those things that we value most in our human societies. The thing that stands out most to me is justice. One of the reasons why we feel schadenfreude, often, is because we feel that someone’s getting a kind of deserved comeuppance. It’s only fair that they should suffer in some way. So you know someone shoves past you in the queue at the supermarket and then their credit card is declined, or they steal your parking spot and then bang the front of their car. You know, these little things that kind of give us a little jolt of pleasure in our day. I think we think, well, it’s karma. You know, they deserved it. Maybe next time they won’t be so you know… try to get one over on us and so on. So I think the schadenfreude might seem quite antisocial, but actually often when we think about it more, we can understand that is really connected to you know very cherished ideas about justice and fairness, as well.

Gabe Howard: You brought up the word karma. Is this just karma? Is it something more? And is there an English word for this or is it really just schadenfreude. I’m gonna get it right before the end of the show.

Tiffany Watt Smith: There is no English word for this particular pleasure, although over the centuries people have had a go at trying to invent one. So around the 16th Century, someone tried to introduce “epicaricacy,” but that is a real mouthful and that definitely did not catch on because about a hundred years later, you’ve got people saying oh why don’t we did we have a word for this in English?

Gabe Howard: And I can’t pronounce that word either so I’m glad that one didn’t work.

Tiffany Watt Smith: Yeah, that was a terrible ugly word. It comes from the ancient Greeks for this particular feeling. But certainly many other cultures and languages have a word for this, but you better to ask me to pronounce it, because I definitely can’t. But they are in Danish and in French, the Japanese have a saying, a really wonderful saying, that the misfortunes of others taste like honey. So this idea is around in many different languages, but in English I can only assume that over the centuries we’ve found the idea so distasteful and believe that it’s not us that feel like this but any other people, that we’ve just never quite given this a name.

Gabe Howard: It’s interesting that you said only other people feel this way when we’ve all felt this way. I personally felt this way and I consider myself to be a good person. I know that Vin has felt this way and and I will personally vouch that Vin is a good person. But it is sort of a… like you said, people feel guilt about it. What is up with that? Is it just part of our makeup? Is there a biological need to feel this way? Why… you study emotions; why do we have this?

Tiffany Watt Smith: So there’s lots of different questions there, and just to say upfront I absolutely recognize the guilt and the discomfort around it. And even after having spent a long time writing a book about it, in which I was in the situation where I have to confess my terrible schadenfreude crimes, I still feel a certain amount of awkwardness talking about it. So maybe the question about why we might feel guilty about it we can come back to, but there’s certainly lots of reasons why we might feel this emotion and yes, why we might be primed to feel like this. You know I’ve already mentioned about justice and how important it is actually that we enjoy seeing transgressors get some kind of comeuppance and it’s fairly obvious, I think, to assume that you know those pleasures are have been ingrained in us from a very early stage in our social evolution, because human society depends on justice to run smoothly. So it makes sense that we would enjoy seeing transgressors exposed or embarrassed or punished in some way. Again, I think that makes sense in forms of fairness you know when we sense that someone has perhaps got a bigger slice of the cake than we have, you know someone who’s very wealthy or seems to have all the talent or all the lark or you know… and then we see that person sort of not quite get what they want. You know, perhaps get tripped up in some way, that the enviably good looking person in your school gets a huge spot on the day of the dance, something stupid like that. It gives us a little a feeling of you know that the playing field has been leveled again. Things feel a bit fairer. Again, very important for our society to survive, but also important because you know we find ourselves as humans living in groups constantly comparing ourselves to one another, trying to make sure that we are not falling too far behind, and making sure that we can get a good share of the resources and so on. And so in these kind of small, competitive ways, which are completely normal and natural, even if they don’t always feel very pleasant, then schadenfreude does play an important part, because it’s sort of a little moment of recognition that oh yes this person that we were competing with, you know, slightly fallen behind and that makes us feel a little boost that we might be just about getting ahead. I think that kind of completely normal.

Gabe Howard: So it’s like a boost of confidence that maybe pushes us a little further and allows the gap to shorten a little you know from the “we can’t overcome” to “wait, I see a possibility.”

Tiffany Watt Smith: So the pleasure isn’t simply you know ha ha you’ve fallen flat on your face, it’s also a sense of optimism and potential for us, for our thing that we’re trying to get going. One of the areas I think this is really fascinating with actually is in relation to work, in the workplace, there’s so much schadenfreude in the workplace. Particularly, I think, in relation to those who are our superiors you know, our bosses and so on, and there’s nothing sort of more delightful really than seeing that person who wields power over you. you know. experience some minor embarrassments. because it allows us to kind of feel that you know that that sort of possibly not very nice boss. you know. when they have or experience some sort of mishap, it allows us to kind of see a little chink, little glimpse of possibility where we might sort of steal back a tiny bit of power of our own. Psychologically I think that’s very important.

Vincent M. Wales: So basically what you’re saying is that despite this sounding like a rather spiteful and awful emotion to suffer, we might actually get something positive out of it.

Tiffany Watt Smith: I think of course we do get something positive out of it because it is gives us pleasure and that is hugely important. But yes that positivity may actually sort of extend to thinking about ways in which we form more coherent and stable societies, which I think is the unexpected thing about schadenfreude. I think schadenfreude works in all kinds of other ways too. One of the things that found again and again in the research on this emotion is that it really does help bond groups together, and this isn’t unexpected. I think we’ve all seen this example with rival sports teams. You know schadenfreude is you know taking pleasure in you know the own goal of the other side. That’s one way in which a team can really bond together, it’s not just that you put the other side down, it’s also that you laugh together, you feel pleasure together, laughing together is a very bonding and important experience. Now of course that can go too far and it can have quite unpleasant effects, so we can talk about that perhaps in a bit. But we do see schaudenfreude playing this really important role in cohering groups together. Actually, there’s been some research on laughter that suggests that this may have really been a very important mechanism far far back in the evolutionary past. There was a study done at the University of Oxford by Robin Dunbar who’s an evolutionary psychologist. And he was looking all kinds of laughter, but fell on looking at… a sort of belly laughing, you know when you’re laughing so hard that it actually hurts. And it’s only humans that have this kind of laughter. And he found that people only ever laughed like that in response to slapstick. So people falling over, you know, hitting themselves on the head with buckets and so on. And he found that when people laughed like that, then shortly after they were able to withstand much greater pain than they were beforehand or if they laughed in some other way.

Gabe Howard: So The Three Stooges were saving lives. [laughter]

Tiffany Watt Smith: Well this is what he’s suggesting, he’s saying that perhaps this kind of slapstick entertainment has been part of our you know our cultural heritage for a really really long time. And when our distant ancestors were all laughing together around a fire at someone, you know, pretending to get hit on the toe with a hammer, that actually that laughter was important not just because it bonded people into those groups that were crucial for survival, but also because it allowed people to cope in very hostile and dangerous environments where there was a lot of pain. I thought it was really intriguing.

Gabe Howard: We’ll see you in about 30 seconds after these messages from our sponsor.

Narrator 2: This episode is sponsored by BetterHelp.com, secure, convenient and affordable online counselling. All counselors are licensed, accredited professionals. Anything you share is confidential. Schedule secure video or phone sessions, plus chat and text with your therapist whenever you feel it’s needed. A month of online therapy often costs less than a single traditional face-to-face session. Go to BetterHelp.com/PsychCentral and experience seven days of free therapy to see if online counselling is right for you. BetterHelp.com/PsychCentral.

Vincent M. Wales: Welcome back, everyone. We’re here with Dr. Tiffany Watt Smith discussing schadenfreude.

Gabe Howard: I think that comedians for a long time, and even myself, I’m not a comedian, but I do public speaking, and I know that if I make fun of myself, then the audience is more likely to laugh and there’s comedians that have made their whole careers about talking about how they’re bad friends bad, you know, they’re ugly or they’re fat or they’re worthless or they’re pointless or, you know, this self-deprecating humor is just very common in our society. Is that an example of schadenfreuden? Nope… still got it wrong.

Tiffany Watt Smith: I think that that is really one of the most neglected forms of schadenfreude in that when people write about schaudenfreude, they really don’t often talk about this particular phenomenon. And I think this is an example of how we use schadenfreude all the time. I mean, if you start a new job, you know you’ll go into that office or that new group of people and you will tell a self-deprecating story of some terrible disaster that happened to you on the way to work. You know, you do it not just to entertain people, but so that you are seen as less of a threat. You know, that the kind of person who is coming into a new group or is the outsider always seems like a threatening person. So those kind of stories allow people to laugh at you and laugh with you, laugh at your expense, I suppose. And that’s, you know is a way of being accepted into the group as much as it is a way of giving everyone else pleasure. And as you say, you know it’s an absolute staple of standup comedy. Standup comics know that people enjoy hearing about the suffering of other people. And standup gives them a license to enjoy it, I think.

Gabe Howard: And schadenfreude is also an example of the millionaire with the tax problem or the very tall person who bangs his head on the doorway and things like that. These are all little examples of where they have something very desirable, but that desirable thing also has a negative. So maybe it’s like every silver lining has a cloud? Or am I oversimplifying or undersimplifying?

Tiffany Watt Smith: I think one of the things that I found when I was trying to tackle writing this book was that you know this is a very complex emotion. You know there are some emotions which feel like quite simple to think about because it’s a trigger and a response. And it’s kind of one thing you know, scary bear you know your heart rate races and you and you run away. Schadenfreude isn’t quite like that kind of emotion. It’s what psychologists call the cognitive emotion. So a cognitive emotion means that it is involved with appraising and judging a situation and doing all kinds of sort of very fast mental calculations to work out whether someone really deserves it whether it’s really funny or whether in fact this person needs our help, whether they really injured themselves or whether they’ve just sort of suffered some minor embarrassment. Yes, all of these complicated things are going on when we experience schadenfreude. And we experience it in relation to a kind of vast range of different sorts of phenomena or in a vast range of different kind of situations. So sometimes it can be as simple as someone slipping on a banana skin or the Three Stooges. And sometimes it’s to do with you know that seeing someone who we think has behaved really unfairly being called out or lambasted in the media. And yeah and sometimes it is these situations where we feel, you know we almost tell ourselves that, you know there’s a highly desirable trait, you know being very tall, being very glamorous. I don’t know, being very clever or being able to speak twelve languages, you know has in fact got its downside. And this is part of a little trick we will play on ourselves and I’m sure we all do it. You know, a way of just making life’s inevitable unfairnesses that little bit more palatable. It’s not just us that experience difficulty, failure, embarrassment. You know everyone does. And I think that’s what we want to remind ourselves of that, continually.