#italian campaign of wwi

Text

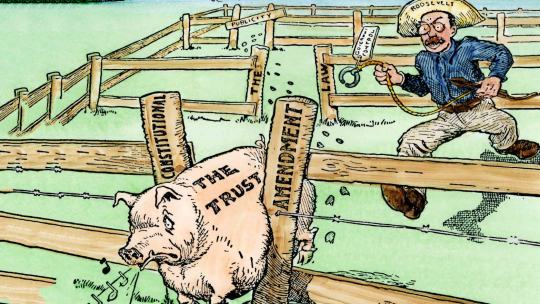

There are few wars marked so heavily by horror and with so little break from the horrors as this one:

One of my relative quirks as a military historian is believing that the stalemates and failures, which are much more typical of real warfare than the decisive Gaugamelas, offer much more realistic views of what war and the waging of war is than the Gaugamela-Cannae obsession (and indeed where Gaugamela remade the world Cannae was a victory that did less damage to Rome than the Arausio against the Cimbri and Teutoni did).

In the annals of the various theaters of WWI this is why I find the Eastern Front to be more of a set of lessons learned from the war than the Western, because all the combatants failed and were consumed by the war they started, even the ones that looked like they won. More broadly Salonika and the Italian campaign, the subject of this one, embody the 'Blackadder Thesis' of WWI in the closest it ever came to reality.

From 1915-8 the Italians were plunged into twelve Battles of the Isonzo, an Austrian drive on the Trentino, the Battle of the Piave, and the Battle of Vittorio-Venetto in conditions of freezing horror at high altitude where the war's two worst generals, Cadorna and Conrad, had unfettered power over the campaign. Austria owed its successes equally ironically to a general that modern ethnic ideas would consider Croatian who considered himself a subject of the House of Habsburg and beyond nationality like a good Habsburg subject would.

The soldiers of Italy displayed an uncommon valor through eleven Battles of the Isonzo where only the sixth, which saw the capture of the town of Gorizia, marked a major advance and most of them fit solidly into the pictures of the worst WWI generalship in troops being sent into headlong charges into the teeth of prepared positions by generals detached from the reality of the front and utterly unsympathetic to it. The price for the eleven battles, plus the technical victory in the Trentino Offensive, was the twelfth, usually known as Caporetto, or in the German name for it, Karfreit.

Eleven futile battles produced a near-collapse of the Kingdom of Italy that was redeemed not least by allied aid the Italians proved distinctly ungrateful for, and the ultimate price of the combination of vainglorious incompetence personified by the duel of Cadorna and Conrad was the disintegration of Austria-Hungary and the transformation of the rotting fabric of the Kingdom of Italy by Mussolini's March on Rome into the world's first fascist state.

In many ways the scars of the First World War linger even more thoroughly in Italy than in the UK, affecting both the resonance of fascism and the poor performance of the Italians of the Second World War, much less willing to die for Il Duce than they were for Cadorna and Diaz in the previous war. Such is the price Italy paid for what was one of history's most ill-starred concepts and the most grimly wretched in execution.

I believe that people who want to understand the nature, too, of what humanity can endure and the realities of how utterly sordid real wars are could stand to read this from cover to cover and to see that oftentimes authority does not deserve respect because it exists, and the dangers of creating echo chambers detached from any remote contact with reality.

10/10.

#lightdancer comments on history#book reviews#world war i#italian history#italian campaign of wwi#cadorna vs conrad: battle of the dumbfucks

0 notes

Text

fun fact about the rouge one shot

commander douhet is named after giulio douhet, an italian general during WWI who was arrested for criticizing his superiors because he believed they weren't using their air force to its full potential. he advocated strongly for using bombers on enemy cities to break stalemates as well as the will of their populations. at the time period, he was one of the first to advocate for strategic bombing campaigns on cities.

it is worth noting that the difference between "civilian" and "military" casualties only came into existence in the post-WWII era. until that period, european military leaders did not distinguish between the two groups since civilians were often just as involved in the war effort (they farmed the food that was sent in soldiers' rations kits, manufactured their weapons and munitions, etc) and also because they didn't really care lol. i have actually read excerpts from douhet's power of the air wherein he literally advocates for bombing civilian centres. his theory correctly predicted many of the bombing campaigns seen in WWII, such as the bombing of dresden (in which the british dropped so much artillery on the city of dresden that its river literally dried up from the heat) and the us fire bombing of tokyo. ironically enough, the us army actually expressed a bit of moral outrage over britain's campaign in dresden, since the us army's modus operandi at the time was to conduct daytime strikes on industrial targets rather than urban ones, but this attitude clearly did not hold out by the time they were focused on defeating japan lmao.

anyways, douhet was ahead of his time military-strategy wise and died before WWII began, which i can honestly only compare to van gogh dying before any of his works became famous. i would call this a tragedy (jokingly) but the last thing anyone needed was for this guy to be in charge of the italian air force during WWII so its probably good that he checked out early

#what if i rambled about the history of strategic bombing on my sonic blog...#did you know that when zeppelins were first invented that the major european powers immediately banned using them for military purposes#this only lasted for around five years though#the idea of using zeppelins in war was so terrifying because for the first time ever#cities could be attacked without first defeating the country's army#truly mind blowing at the time#redposts

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The 92nd Infantry Division, a military unit of approximately fifteen thousand officers and men, was one of only two all-black divisions to fight in the Army in WWI and WWII. The 92nd was organized on October 1, 1917, at Camp Funston and included African American soldiers. Before leaving for France in 1918, it received the name “Buffalo Soldier Division” as a tribute to the four Buffalo soldier regiments that fought in the regular Army in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The soldiers were deployed to the front lines in August 1918. The 92nd saw action in one of the last Allied operations of the war—the Meuse-Argonne Offensive September-November 1918. The 92nd, unlike the 93rd, the other all-black division in WWI, fought under American command. When WWI ended, the 92nd returned and was deactivated in February 1919. After the US entered WWII, the 92nd was reactivated on October 15, 1942, and trained at Fort Huachuca with the 93rd Infantry, the other all-black division. After that training was completed, the 92nd was deployed to Italy while its counterpart was sent to the South Pacific. On July 30, 1944, the first units of the 92nd arrived in Naples, and by September 22, the entire division was stationed in the Po Valley. Assigned to the Fifth Army, the 92nd included the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, both suffered some of the heaviest casualties of the war and became one of the most decorated military units. The division first saw significant action against German troops and Italian troops in September, and by October, they were engaged in offensive campaigns in the Serchio River Valley and along the coast near the city of Massa. On April 29, 1945, elements of the 92nd liberated the Italian cities of La Spezia and Genoa. They participated in other battles in Northern Italy until May 2, 1945. First Lt. John R. Fox won the Medal of Honor for his action in the Serchio Valley on December 26, 1944, and First Lt. Vernon J. Baker won the medal for his action near Viareggio on April 5–6, 1945. Both medals were not awarded until 1997. The 92nd returned on November 26, 1945, and was deactivated on November 28. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence https://www.instagram.com/p/CjLGrHhrOkZ/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

Killed Piave - July 8th - 1918

Ernest Hemingway

Desire and

All the sweet pulsing aches

And gentle hurtings

That were you,

Are gone into the sullen dark.

Now in the night you come unsmiling

To lie with me

A dull, cold, rigid bayonet

On my hot-swollen, throbbing soul.

1 note

·

View note

Text

About Lewis Nixon’s father Stanhope Nixon

Source: mostly from old newspapers and digitized documents (I can’t guarantee the accuracy because they are fragmented information. I will just put it out there for someone may find some interesting useful backstories).

He was born on 1 April 1894, the only child of Lewis Nixon the shipbuilder.

In the 1910 census, the Nixons household included Lewis Nixon the head of the house, Sally the wife, Stanhope the son (16 yr old) and 7 servants.

His parents really doted on him. When he was a littler child, Mr and Mrs Lewis Nixon took him to travel around the world, France, UK, Havana, Germany. Around 1904-1906, Lewis Nixon was living in Russia, supervising the manufacture of torpedo ships for the Czar. He took Stanhope with him so Stanhope lived in Russia for one or two years when he was around 11 yr old.

On their way to Russia, they stopped in Rome. Lewis Nixon took Stanhope to visit Pope Pius X. Someone said to Lewis Nixon: “When his Holiness sees your boy he will have no eyes whatever for you.” and when the pope saw Stanhope, he ceased speaking, and hugged the boy to his breast and gave the boy a large silver medal as a gift. (I can only assume that Stanhope was indeed very good-looking, otherwise I really don’t know what Doris saw in him. From Stanhope’s draft card, he had blue eyes, brown hair and height of 6'1.5" ft).

He was in Yale (Sheffield Scientific School 1912-1914, studying engineering).

His study in Yale ended prematurely because he nearly beat a man to death in 1914.

The assault case: “The young Nixon admitted having struck Everit over the head with the bolt three times because the latter resented the fact that Nixon had knocked his hat off with the iron bolt”. On the night of the attack, Stanhope attended a performance given by Gertrude Hoffmann at a local theatre with his Yale friends. After the party the group of students returned to the Hotel Taft with the actress. But Stanhope didn’t go with his friends to the Hotel Taft, he went to a chop suey restaurant instead. On his way, he picked up a 12 inch iron bolt left by the construction workers. He met Everit on his way to the restaurant, and knocked Everit’s hat off with the bolt. After that Everit was vexed and chased after him. But he didn’t catch Stanhope. Stanhope came back and followed after Everit, assaulted him 3 times with the bolt and ran away. Everit suffered concussion of the brain and lay dangerously ill for weeks. At first the police had no clue to the identity of the assailant, but they were aware that a group of Yale students were boisterous on that night (apparently they slapped another passenger in the face and hurled iron bolts through windows of houses). The police placed an under-cover detective in the club near Sheffield Scientific School, and Stanhope foolishly bragged what he did to the under-cover detective.

After the trial, Lewis Nixon Sr. took Stanhope to the theatre (he was so spoiled). He was bailed out with $ 25,000 and withdrawn from Yale.

He registered at the draft office in both 1917 and 1942, but didn’t actually serve.

After the assault case, Stanhope was still a spoiled brat living under the protection of his influential father. Here is a piece of news on 22 Apr 1918 titled “Sons of Men of Influence assigned to bullet-proof jobs”: “One of the young officers among the 778 men of draft age holding commissions in the ordnance offices here is First Lieutenant Stanhope W. Nixon, son of Lewis Nixon, the millionaire ship builder.”

In 1936, he was involved in a drunk driving charge (although it’s said his sales manager was driving and Stanhope was in the passenger seat). They crashed into a truck but only hurt themselves. At first they denied being drunk, then admitted that they were drinking at the Nixon inn (but only 4 beers). After leaving the Nixon Inn, the sales manager drove Stanhope to the city to Hotel Woodrow Wilson to cash a check. Stanhope Nixon was to identify him. (The weird thing is, the car crash happend at midnight 12:40. Who on earth would drive to a hotel to "cash a check” at midnight?!)

Here is another piece of news in 1944, not explicit done by Stanhope, but very likely by him (because this news got Doris’ name wrong, so it’s not her who called the newspaper to publish this article, and both grandparents have passed away in March 1944 so can’t be them. The tone was so vain it’s almost certainly Stanhope’s deed. The title was “Lewis Nixon traces Military Forebears Back to Revolution”, it reads “ Lt Nixon, now in foreign service in Italy with the paratroopers, is a direct descendant of General Andrew Lewis, George Washington’s Chief of Staff…..bla bla bla ….. , Lt Nixon’s father, Stanhope Wood Nixon, chairman of the board of directors of the Nixon Nitration Works, was a lieutenant in WWI; his grandfather, Lewis Nixon, famous shipbuilder and outstanding naval architect, fought in the Spanish-American War …..bla bla bla ….. Lt Nixon received awards for gunnery, and proficiency with the rifle, pistol, and has taken an active part in the Italian campaign. (But in fact at the time of the article, Lew was still in Aldbourne, hasn’t received any awards and has never been in Italy campaign).

He divorced Doris in Aug 1945 and married Elisabeth Muchany (the Blond) in September, who was 15 years younger than him. He and the Blond separated in 1951 (because he was cheating with other mistresses). But somehow they patched things up and went to Bahamas together in 1956 and remained married until his death.

He died in 1958 and his will dictated to sell Nixon Nitration Works within 2 years.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Working on a WWI D&D Setting

Every country is primarily populated by a different race (with minorities in each of them of course). But, I can’t help but snicker at myself over the fact that I made the Belgians Firbolg, because there’s something hilarious to me about the thought of a Firbolg Hercule Poirot finely grooming himself, getting his mustache just right, walking with his little gait, carrying a telescope cane, and being the most dignified looking hairy butterball in the world.

Gosh I want to DM that campaign so bad.

For reference, here are the other races/county combinations and a brief rationale:

German – High Elves/Wood Elves, the black forest of central Europe, source of most elfin mythology.

Russia – Skinchangers, Werewolves and Werebears (Werewolves are the Aristocracy, Werebears are the up and coming Communists).

France – Tieflings, because the French are fashionable little devils.

England – Hobbits, half elves, and humans. Part of me wants to exclude humans from the campaign entirely though. But maybe I’ll make the Welsh humans for fun.

Switzerland – Dwarves. Neutral, mountain-dwelling, want to be left alone.

Poland - Goliaths (peaceful, salt of the earth folk, caught between two global superpowers)

Ottomans – Genasi (Turkey - Wind & Water), Arabia (fire), Egypt (earth).

Greece – Satyr, there are a lot of fantasy races that could be Greeks, but I think Satyr fit best.

Australia – Drow (for the meme)

Serbia – Kenku (Bird heraldry on flag, but brought low by the stronger Austria-Hungary)

Romani – Kobalds (an oft looked down upon race) or Elan (Psionic humanoids who don’t quite fit in).

Romania – Dragonborn (strong dragon mythology in Romania, obvious choice)

Austria-Hungary - Aarakocra (The stronger bird folk in central Europe)

Bulgaria – Centaur (Centaur lived in the northern hills of Greece in Greek Mythology, Bulgaria was well-known for cavalry during the middle ages. These things just fit).

Belgium – Firbolg (because of Poirot)

Albania – Damphir (I forget my rationale for this one to be honest)

Italy – Aasimar (If the French are devils, the Italians are angels, pfft)

Netherlands – Tritons (Way too obvious)

Africa – Loxodon and Lizardfolk and Leonids (Because of course Africa gets the cool races)

Norse – Bugbears (not overly sold on this one, but the thought of the Nordic countries all being vaguely Grendel shaped seems fitting)

USA – Orcs - not sure if I want the USA in the historical setting - maybe just make it an extension of the Iroquois Confederation.

South American - Tabaxi (If there were Llama Folk, I would so go for those)

Canada – Treants (admit it, you laughed at this one).

India – Yuan-ti (Because Naga are big in Indian mythology)

China – Gith (Not sold on this one either, but there’s something compelling about the Githyanki and Githzerai being a split/divided race that seems to fit with historical China’s internal divisions).

Mongolia – Hobgoblins (Counterparts to the Orcs of North America).

Japan – Oni and Spirit Folk (either/or - I love the thought of civilized Oni though, hate when “evil races” are diminished to savage brutes. Give them art and culture and technology and philosophy of their own, make them unique and interesting).

Anyways, I think this would be a fun setting, maybe make two parallel campaigns where the players have PCs fighting on both the Central Powers and the Allied Powers.

If you have suggestions or thoughts, please leave a comment. Please?

#dungeons and dragons#world war one#hercule poirot#fantasy races#I think the wood elves are probably the bavarian germans#because they were the most chill#high elves are definitely prussian though#I know I'm missing a lot of countries but I didn't want to make this a comprehensive list#also this was meant as a fun thought experiment and not meant to be offensive or racist or anything#I honestly love all of these races so it's not that

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

So what’s the proper nomenclature for each front in WWI? There’s obviously the Western Front and Eastern Front, but what about the Balkans, Pacific, the Middle East and Italy? Are those referred to as “campaigns,” “theaters” or “fronts”?

I don’t think it’s ever been really standardised, but this is the way I most often see it written/spoken about.

Theatres - Europe, Africa, Asia, Middle East, Pacific

Fronts, which are more or less static - Western, Eastern, Balkan, Italian

Campaigns - Everything else basically. So Palestine, East Africa, Mesopotamia, Caucuses.

But none of that is really consistent. Gallipoli for example is called a campaign, although it was essentially static. But to be honest, as long as you’re clear and consistent with what you say it doesn’t really matter

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zuck calls Apple a monopolist

The copyright scholar James Boyle has a transformative way to think about political change. He tells a story about how the word "ecology" welded together a bunch of disparate issues into a movement.

Prior to "ecology," there were people who cared about owls, or air pollution, or acid rain, or whales, and while none of these people thought the others were misguided, they also didn't see them as being as part of the same cause.

Whales aren't anything like owls and acid rain isn't anything like ozone depletion. But the rise of the term "ecology," turned issues into a movement. Instead of being 1,000 causes, it was a single movement with 1,000 on-ramps.

Movements can strike at the root, look to the underlying economic and philosophical problems that underpin all the different causes that brought the movement's adherents together. Movements get shit done.

Which brings me to monopolies. This week, Mark Zuckerberg, one of the world's most egregious, flagrant, wicked monopolists, made a bunch of public denunciations of Apple for...monopolistic conduct.

Or, at least, he tried to. Apple stopped him. Because they actually do have a monopoly (and a monoposony) (in legal-economic parlance, these terms don't refer to a single buyer or seller, they refer to a firm with "market power" - the power to dictate pricing).

Facebook is launching a ticket-sales app and the Ios version was rejected because it included a notice to users that included in their price was a 30% vig that Apple was creaming off of Facebook's take.

https://www.theverge.com/2020/8/28/21405140/apple-rejects-facebook-update-30-percent-cut

Apple blocked the app because this was "irrelevant" information, and their Terms of Service bans "showing irrelevant" information.

This so enraged Zuck that he gave a companywide address - of the sort that routinely leaks - calling Apple a monopolist (they are), accused them of extracting monopoly rents (they do), and of blocking "innovation" and "competition" (also true).

https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/pranavdixit/zuckerberg-apple-monopoly

Now, there are a bunch of Apple customers who consider themselves members of an oppressed religious minority who'll probably stop here (perhaps after an angry reply), and that's OK. You do you. But I have more to say.

Apple is a monopolist, sure, but more importantly, they are monoposonists - these are firms with "excessive buying power," gatekeepers who control access to purchasers. Monoposony power is MUCH easier to accumulate than monopoly power.

In the econ literature, we see how control over as little as 10% of the market can cement a firm's position, giving it pricing power over suppliers. Monopsony is the source of "chickenization," named for the practices of America's chicken-processing giants.

Chickenized poultry farmers have to buy all their chicks from Big Chicken; the packers tell them what to feed their birds, which vets to use, and spec out their chicken coops. They set the timing on the lights in the coops, and dictate feeding schedules.

The chickens can only be sold to the packer that does all this control-freaky specifying, and the farmer doesn't find out how much they'll get paid until the day they sell their birds.

Big Chicken has data on all the farmers they've entrapped and they tune the payments so that the farmers can just barely scratch out a living, teetering on the edge of bankruptcy and dependent on the packer for next year's debt payments.

Farmers who complain in public are cut off and blackballed - like the farmer who lost his contract and switched to maintaining chicken coops, until the packer he'd angered informed all their farmers that if they hired him, they would also get cancelled.

Monopsony chickenizes whose groups of workers, even whole industries. Amazon has chickenized publishers. Uber has chickenized drivers. Facebook and Google have chickenized advertisers. Apple has chickenized app creators.

Apple is a monopsony. So is Facebook.

Market concentration is like the Age of Colonization: at first, the Great Powers could steer clear of one another's claims. If your rival conquered a land you had your eye on, you could pillage the one next door.

Why squander your energies fighting each other when you could focus on extracting wealth from immiserated people no one else had yet ground underfoot?

But eventually, you run out of new lands to conquer, and your growth imperative turns into direct competition.

We called that "World War One." During WWI, there were plenty of people who rooted for their countries and cast the fighting as a just war of good vs evil. But there was also a sizable anti-war movement.

This movement saw the fight as a proxy war between aristocrats, feuding cousins who were so rich that they didn't fight over who got grandma's china hutch - they fought over who got China itself.

The elites who started the Great War had to walk a fine line. If they told their side that Kaiser Bill is only in the fight to enrich undeserving German aristos, they risked their audience making the leap to asking whether their aristos were any more deserving.

GAFAM had divided up cyberspace like the Pope dividing the New World: ads were Goog, social is FB, phones are Apple, enterprise is Msft, ecommerce belongs to Amazon. There was blurriness at the edges, but they mostly steered clear of one another's turf.

But once they'd chickenized all the suppliers and corralled all the customers, they started to challenge one another's territorial claims, and to demand that we all take a side, to fight for Google's right to challege FB's social dominance, or to side with FB over Apple.

And they run a risk when they ask us to take a side, the risk that we'll start to ask ourselves whether ANY of these (tax-dodging, DRM-locking, privacy invading, dictator-abetting, workforce abusing) companies deserve our loyalty.

And that risk is heightened because the energy to reject monopolies (and monoposonies) needn't start with tech - the contagion may incubate in an entirely different sector and make the leap to tech.

Like, maybe you're a wrestling fan, devastated to see your heroes begging on Gofundme to pay their medical bills and die with dignity in their 50s from their work injuries, now there's only one major league whose owner has chickenized his workers.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m8UQ4O7UiDs&list=FLM6hLIAIO-KfsNFn8ENnftw&index=767

Maybe you wear glasses and just realized that a single Italian company, Luxottica, owns every major brand, retailer, lab and insurer and has jacked up prices 1,000%.

https://www.latimes.com/business/lazarus/la-fi-lazarus-glasses-lenscrafters-luxottica-monopoly-20190305-story.html

Or maybe the market concentration you care about it in healthcare, cable, finance, pharma, ed-tech, publishing, film, music, news, oil, mining, aviation, hotels, automotive, rail, ag-tech, biotech, lumber, telcoms, or a hundred other sectors.

That is, maybe you just figured out that the people who care about owls are on the same side as the people who care about the ozone layer.

All our markets have become hourglass shaped, with monop(olists/sonists) sitting at the pinch-point, collecting rents from both sides, and they've run out of peons to shake down, so they're turning on each other.

They won't go gently. Every Big Tech company is convinced that they have the right to be the pinchpoint in the hour-glass, and is absolutely, 100% certain that they don't want to be trapped in the bulbs on either side of the pinch.

They know how miserable life is for people in the bulbs, because they are the beneficiaries of other peoples' misery. Misery is for other people.

But they're in a trap. Monopolies and monopsonies are obviously unjust, and the more they point out the injustices they are EXPERIENCING, the greater the likelihood that we'll start paying attention to the injusticies they are INFLICTING.

Much of the energy to break up Big Tech is undoubtedly coming from the cable and phone industry. This is a darkly hilarious fact that many tech lobbyists have pointed out, squawking in affront: "How can you side with COMCAST and AT&T to fight MONOPOLIES?!"

They have a point. Telcoms is indescribably, horrifically dirty and terrible and every major company in the sector should be shattered, their execs pilloried and their logomarks cast into a pit for 1,000 years.

Their names should be curses upon our lips: "Dude, what are you, some kind of TIME WARNER?"

But this just shows how lazy and stupid and arrogant monopolies are. Telcoms think that if they give us an appetite for trustbusting Big Tech, that breaking up GAFAM will satiate us.

They could not be more wrong. There is no difference in the moral case for trustbusting Big Tech and busting up Big Telco. If Big Tech goes first, it'll be the amuse-bouche. There's a 37-course Vegas buffet of trustbustable industries we'll fill our plates with afterward.

Likewise, if you needed proof that Zuck is no supergenius - that he is merely a mediocre sociopath who has waxed powerful because he was given a license to cheat by regulators who looked the other way while he violated antitrust law - just look at his Apple complaints.

Everything he says about Apple is 100% true.

Everything he says about Apple is also 100% true OF FACEBOOK.

Can Zuck really not understand this? If not, there are plenty of people in the bulbs to either side of his pinch who'd be glad to explain it to him.

The monopolized world is all around us. That's the bad news.

The good news is that means that everyone who lives in the bulbs - everyone except the tiny minority who operate the pinch - is on the same side.

There are 1,000 reasons to hate monopolies, which means that there are 1,000 on-ramps to a movement aimed at destroying them. A movement for pluralism, fairness and solidarity, rather than extraction and oligarchy.

And just like you can express your support for "ecology" by campaigning for the ozone layer while your comrade campaigns for owls, you can fight oligarchy by fighting against Apple, or Facebook, or Google, or Comcast, or Purdue Poultry...or Purdue Pharma.

You are on the same side as the wrestling fan who just gofundemed a beloved wrestler, and the optician who's been chickenized by Luxottica, and the Uber driver whose just had their wages cut by an app.

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

Severino Di Giovanni (1901-1931).

Italian anarchist.

.

Di Giovanni became quickly radicalised against authority, having grown up in poor post-WWI rural Italy. He married his cousin Teresa and the pair decided to head for Argentina in the 1920s. They immediately fell in with anarchist and anti-fascist groups that pervaded pre-WWII Buenos Aires.

.

Di Giovanni was quick to fly the flag for Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, Italy’s most famous anarchists who were on trial in the US. Di Giovanni, having taught himself the art of typography earlier on in life, produced his own anarchist publication called Culmine. The death sentencing of Sacco and Vanzetti prompted Di Giovanni to conduct the first of many bombings that he would carry out against perpetrators of fascism all over the world.

.

He bombed the US embassy in Buenos Aires in May 1926 and was captured by the authorities. They tortured him for five days but he would not admit his guilt. A year later, Di Giovanni blew up a statue of George Washington in Buenos Aires to protest the execution of the two anarchists in Massachusetts. A few hours later, he detonated a bomb in the Ford Motor Company in the Argentine capital. A month later, he set off a bomb in the house of the police officer in charge of investigating the explosions, who had left the house momentarily.

.

Several other bombings followed in late 1927 and early 1928. CitiBank, the Bank of Boston, the Italian consulate and a pharmacy were all targeted by Di Giovanni, with varying success on his part. However, this bombing campaign and Di Giovanni’s tactics did not sit well with other prominent anti-fascist leaders, who were critical of his methods. He conducted one of Argentina’s most infamous robberies, before being arrested in 1931. He was executed in 1931 at the age of 29.

[Submission]

#Severino di Giovanni#italian history#Italy#early 20th century#Ww1#1920s#anarchy#anarchist#politics#argentine history#argentina#history lesson#history#historical#historic#history buff#history lover#history crush#history hottie#history nerd#history geek#historical crush#historical babes#historical hottie#historical figure#história#histoire

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

10 Facts about Rome’s Piazza Venezia and the Vittoriano

There’s no way to miss the hustle and bustle of Rome’s largest round-a-bout: the Piazza Venezia. On one side you can look down Rome’s longest street, the Via del Corso to the ancient northern gates of the city. From another angle, the ruins of the Imperial Forums lead the way to the Colosseum. Take a different road and you’ll end up in the Jewish Ghetto, on your way to Rome’s Trastevere neighborhood and last but not least, towering over the piazza, is the un-missable marble monument: Il Vittoriano. The four major roads of Rome meet in the piazza, so take one and explore the city but before you go, here are 10 facts about piazza Venezia!

1 The Vittoriano (i.e. The Wedding Cake) The most notable monument in the piazza derives from the name of Italy’s first king, Victorio Emanuele II of Savoy to whom it is dedicated. Construction started in 1885, 4 years after his death and it was fully completed in 1925 under Mussolini. Another name is “l’Altare della Patria” or “Altar of the Fatherland” as the monument was built to celebrate Italian unification and the birth of Italy as a nation at the end of the 19th century. It also has two less prestigious nicknames: “The wedding cake” and also “The typewriter.” Most Romans aren’t a fan of the monument which they say doesn’t blend in with the rest of the city skyline.

2 The Horse. Who’s hungry? The centerpiece of the Vittoriano is the enormous bronze equestrian statue of the first king himself. From your view at ground level, the horse might not look that big but at 10 meters long and 12 meters tall, it’s actually gigantic – big enough to comfortably host a dinner inside! Which is exactly what the workers enjoyed after the statue was completed. Twenty people comfortably posed for a photo around long table set up for pastries and vermouth inside the horses belly.

3 The eternal fire and the tomb of the unknown soldier The monument itself is constructed to celebrate the unification of Italy and to demonstrate the power of Rome as a capital. Every piece of art you can see is an important symbol of the fatherland. Over the steps in the center stand the actual “Altar of the fatherland”, containing the tomb of “The unknown soldier”, a symbolic reminder of all the unidentified deaths of WWI. In front of the altar’s relief, visitors can see the statue of the goddess Roma with the secret eternal flame, always guarded by soldiers.

4 Palazzo Venezia This building is one of the oldest Renaissance buildings in Rome, constructed between 1455 and 1464. The Palace, built by a Venetian cardinal (why Piazza Venezia takes its name) who later became Pope Paul II was used as a papal residence, embassy of the Republic of Venice and later headquarters for the Italian government. Benito Mussolini, “Il duce,” had his office inside and from the palace’s balcony overlooking the square he shouted his speeches to the crowds below. Be sure to peek inside where you could enjoy the garden courtyard for a relaxing break from the hustle and bustle of the piazza.

5 Michelangelo’s House Opposite the Palazzo Venezia is an insurance building, the Palazzo delle Assicurazioni Generali, finished in 1906 to mirror the older Palazzo Venezia. Unifying the squares “look” was more important than preserving its history. One of the buildings that was torn down was the house where Michelangelo Buonarroti lived and died, commemorated by a plaque on the side facing the Vittoriano.

6 Palazzo Bonaparte On the north end where Piazza Venezia meets Via del Corso is a 17th century palace, once the property of Napoleon’s family. Napoleon’s mother Letizia Bonaparte lived the last 18 years of her life here and the palace is named after her. She spent most of her time on the first-floor loggia, (note the famous balcony on the corner) watching the busy streets of Rome.

7 The Via del Corso The street was named for the 15th century “corsa dei barberi” or “race of the barbarians” – a tradition at Carnival of racing horses down the 1.5 kilometer street but it’s origins date back to ancient Rome. Today, Rome’s longest, straightest street is best known for shopping.

8 Trajan’s Column Built by Emperor Trajan in 113AD this triumphal column commemorated Trajan’s victory over the Dacians and its spiral bas relief tells the story of the entire campaign Rome held against the country that would ultimately take its name: Romania. But don’t expect to see a statue of the emperor himself atop his own monument. In 1587 Pope Sixtus V set one of Rome’s patron saints there instead: St. Peter.

9 What lies beneath The Ancient Romans certainly weren’t the oldest thing inhabiting the Capitoline Hill. During the excavations to create the Vittorio Emanuele monument an entire skeleton of a straight tusked elephant from the ice age was unearthed!

10 And the view from above Rome boasts a number of impressive views but few match the ones from the top of Il Vittoriano. An elevator was built onto the back of the monument in 2007 and now visitors can access the rooftop of the 135 meter monument for one of the finest 360 degree views of the city.

https://rollingrome.com/10-facts-romes-piazza-venezia-vittoriano/

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Arthur keeps a collection of medals in his office at the University, neatly arranged in a display case they date from engagements of active combat from both WWI and WWII.

ᴡᴏʀʟᴅ ᴡᴀʀ 1

28th July 1914 » World War One Begins.

Arthur was conscripted to the War effort at the age of 20 in the middle of his studies in mathematics at Oxford as a second lieutenant. Drafted and moved by British Intelligence he worked for the geographical section of the War Office until his posting abroad in several theatres of war (France and Cairo) as a civilian aid; initially a cryptographer, cartographer and code breaker. While stationed at this posting he became quite familiar with the local landscapes, working with local commanders to organise and oversee missions alongside keeping maps updated regarding regions in which active campaigns were ongoing.

11th November 1918 » World War One Ends.

ᴍᴇᴅᴀʟꜱ

1914 Star

Croix De Guerre

ᴡᴏʀʟᴅ ᴡᴀʀ 2

1st September 1939 » World War Two Begins.

Arthur applied and during WWII trained as operational aircrew. Across the entirety of the war he flew over 300 operational sorties, twice taking to his parachute - once when wounded - and tallied at least eleven enemy aircraft destroyed.

10th July – 31st October 1940 » Battle of Britain

10th June 1940 – 13th May 1943 » North African Campaign

10th Jul 1943 – 8th May 1945 » Italian Campaign

2nd September 1945 » World War Two Ends.

ᴍᴇᴅᴀʟꜱ

France and Germany Star

1939-1945 Star

Distinguished Flying Cross - For intercepting and shooting down enemy aircraft at dusk whilst on patrol over the sea off the North-East coast of Scotland.

DFC Bar - While leading a section of Squadron 42 to protect a convoy, intercepted about twenty or thirty enemy aircraft, destroying one and severely damaging two others forcing the enemy formation to withdraw.

Distinguished Service Order - For flying over 300 operational flights including 95 at night. During the Battle of Britain led every patrol against the enemy except one due to injury.

Royal Victorian Order - For services to His Majesty King George VI.

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

World History

World War I

#World War I#World War 1#WW1#WWI#World History#World#History#Italy#Italian Army#Italian Campaign#Southern Front#World War

1 note

·

View note

Text

This week in Micronations:

I was looking up Monaco history to learn more about their foundation as a pirate nation and instead I found out something else wonderful. So we all know about Grace Kelly and how she was married in to the monarchy in the ‘50s. But before that, there was a succession crisis!

(And yes, this post has something to do with Lupin III. Read on...)

Apparently Prince Albert I (1880s Arctic Explorer) had a son, Prince Louis II (reigned during WWII and retired a Brigadier General in France's army), but Louis was an only child himself and didn't have any children by the time he was almost 50 and was unmarried as well.

It's amazing that he managed to pull off being unmarried that long at all but I'm sure he and his father sailing around the world for years at a time helped. Still, after a while, people pressured him, and he ended up having a kid with the Parisian-nightclub-hostess-daughter of his ship's laundry lady. That child, Charlotte, then became the 'adopted princess', adopted pretty close after WWI, and is the matriarch from which the modern rulers hail.

As the heir-apparent princess, she had two children, one boy and one girl, but then divorced her husband for "his homosexuality". The day her son, Prince Ranier III, came of age, she renounced her claim to the throne, passing it to him, and then later left Monaco entirely with an "Italian doctor" lover. Her dad, Prince Louis II, officiated over the marriage and divorce and the title passing, because he was the sovereign still. AWKWARD. He'd also picked her husband, so I have to wonder if his gaydar was going off and he liked the guy or something.

But then, it gets even better: she moves to Paris, and eventually ends up running a rehibilitation home for ex-cons out of her mansion, despite the wishes of her family, and lives with her lover, "a noted French former jewel thief.*"

(*Named Rene the Cane of all goddamned things.)

Meanwhile, Prince Louis's cousin, a Duke from Germany, was first in line to Monaco before all this, and also Lithuania and Alsace-Lorraine, wherever the hell that is/was. He was a prince of Wuttenberg (some place in Germany) but couldn't inherit that because of the left-hand marriage of his parents. So after WWI, dude didn't get ANY of those titles because of political drama and restructuring and ever since his heirs (not him) have been suing Monaco and France for damages. And the only reason Charlotte ever came into being at all, presumably, was because France threw a fit about "a German" coming to rule Monaco and switching its allegiance.

This place and its family drama just keep getting better. It's like a freaking tellanovella and I love it. Also of note: Rainier had three children who had three children who had three children (and are still going), more or less, so the gayness got bred out of the family I’m thinking. They learned their lesson, it seems, or at the very least are making up for lost time.

So how does this fit into our tiny fandom? Well in the end I came to this conclusion: Campaign for Rene the Cane to be Grandpa Lupin and for Albert d’ Andressy to be related somehow to Duke Wutta-Dick of Germany. Please. It would make Lupin’s French-Italian flare make soooooo much sense, Albert Andressy would be a much more interesting and dangerous character IMO, Great-Great Grandpa Prince Albert I + Rene is basically everything Lupin is, and suddenly everyone would be a Disney prince(ss). The end.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

While commemorating WWI, Macron auditions to be the leader of Europe

By James McAuley, Washington Post, November 9, 2018

French President Emmanuel Macron will be trying out for the role of leader of Europe this weekend.

As he hosts more than 60 heads of state for a ceremony and peace summit tied to the centennial of World War I’s bloody end, Macron will have an opportunity to show he can bring great powers together and give voice to the values that bind them.

France’s young president, just 40 years old, has long advocated a stronger, reinvigorated European Union and regularly condemns the nationalism spreading across the continent. He stands ready to continue the fight now that German Chancellor Angela Merkel has signaled she will exit the stage.

But Europe may be too divided to accept a grand vision pronounced by a single leader, and Merkel’s departure may do more to isolate Macron than to boost his standing.

“Europeans are too deeply divided among themselves--and on the fundamentals,” said Dominique Moïsi, a foreign policy analyst at the Institut Montaigne in Paris and former Macron campaign adviser.

“What you have is a Europe that is segmenting into different tribes,” said Mark Leonard, director of the London-based European Council on Foreign Relations. These segments are multiplying along an increasing number of fractures, he said.

“There is a clear north-south division over the euro crisis and an east-west division over migration and Russia,” he said. “You also have highly polarized societies in most member states, and that does mean that having a single leader of Europe is kind of utopian at the moment.”

On the world stage, Macron has already had many disappointments. Despite his efforts to woo President Trump, he watched helplessly as the United States withdrew from the Paris climate accord and the Iran nuclear deal. Trump will further slight the French president by attending the ceremony but skipping the peace summit this weekend.

Within France, Macron has successfully pushed through a host of revisions designed to liberalize a famously regulated labor market and to stimulate economic growth. But he has paid a heavy price in popularity. According to a September poll from Ifop, a leading French polling agency, his approval rating is at 29 percent, less than half of what it was when he was elected in May 2017.

By contrast, Europe’s leading nationalist voices, whom Macron has publicly challenged on any number of occasions, remain quite popular. Matteo Salvini, Italy’s interior minister and de facto leader, enjoys an approval rating of 59 percent, according to a poll released this week by the Italian newspaper La Repubblica--making Salvini roughly twice as popular among Italians as Macron is with the French.

A separate Ifop poll, published Sunday, shows that Macron’s party, La République En Marche, or Republic on the Move, has less support than France’s far-right Rassemblement National, or National Rally, in advance of the 2019 European parliamentary elections.

Macron, nonetheless, has focused his pitch this week on his concern about the resurgence of populist tribalism in Europe and the importance of political integration, which he credits with guaranteeing European prosperity and peace.

In interviews, he has invoked the darkest chapters of Europe’s recent history to underscore his anxieties about its present.

“I’m struck to see two things that resemble terribly the 1930s,” Macron told France’s Europe 1 radio. “The fact that our Europe was rocked by a profound economic and financial crisis ... and the rise of nationalisms that play on fears.”

The point, he said, is to recognize the fragility of the European enterprise launched after the two world wars.

“We need a strong Europe, one that protects,” he said.

The question is how many of his guests agree.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the midst of the Great Depression in 1931, nine Black teenage boys were falsely convicted of allegedly raping two white women on a train in Scottsboro, Alabama. The Scottsboro Case quickly became one of the most infamous international spectacles that would eventually define the interwar period. The Scottsboro defense campaign, led by the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) and the International Labor Defense (ILD), emphasized that the defendants’ case should be understood in the larger context of international workers’ struggles occurring throughout the imperial world. The Party’s campaign relied on several strategies to gain international significance, however, its decision to recruit Ada Wright—the mother of Scottsboro defendants, Andy and Roy Wright— to embark on a European speaking tour, was perhaps one of the most significant strategies it utilized.

Wright’s experiences on this tour point to the evolving international landscape that characterize the interwar period. Wright’s lived experience as a Black Southern domestic worker and mother informed her unique perspective of the international labor struggle that persisted during the Great Depression. Her analyses of Black workers’ and mothers’ struggles throughout the Jim Crow South made a considerable impression on British anti-imperial activists and workers alike. Her speeches not only galvanized European workers, but also empowered Black working class women and mothers in the United States to join the communist struggle for workers’ rights, women’s rights, and Black liberation. Her tour ultimately contributed to the formation of an interracial anti-imperialist Popular Front that circulated throughout Britain. When Wright initially embarked upon her European tour in 1933, scholar Susan Pennybacker explains that “London sat uncomfortably poised between Jim Crow and the Third Reich.” The Scottsboro case seemed to be the bridge between the condemnation of the growing fascist movement in Germany and the racialized organization of labor throughout the British Empire.

Ada Wright was in her mid-30s when the ILD asked her to participate in the European speaking tour. In March 1932, the courts confirmed the guilty verdicts and set the defendants’ execution date for May 13th. In response, the ILD commissioned Wright’s European speaking tour, hoping that she could help galvanize more international support for the case. London based West Indian communist Arnold Ward, a colleague and friend of George Padmore wrote to Padmore upon Wright’s arrival in Britain, stating that “Since Mrs. Wright has been here the International Solidarity has taken on a deeper and greater hold on the workers. Here more than I have ever seen before and I think it is for the best.” In sharing her lived realities under Jim Crow, she gave many working class women language with which to protest their own oppression.

At the time, Wright had never traveled outside of the South. She was a mother of three, a widow, and a domestic worker from rural Chattanooga, Tennessee. When the CPUSA initially gained control of the case, Wright was not familiar with the COMINTERN agenda. As a Black domestic worker living under Jim Crow segregation, however, Wright was all too familiar with the exploitation that Black workers faced regularly. She spoke on the evils of racism in the United States and the necessity of mobilizing “the masses against the imperialist war.” She understood the Scottsboro case as a “struggle against the imperialist war, because the Scottsboro persecution grows out of the war preparations of the American boss class.” This profound analysis of racial capitalism inspired audiences of European workers to connect their exploitation to that of colonized workers revolting against their working conditions throughout the British empire.

Throughout the tour, Wright reconciled with both her own lived reality in Chattanooga and the new experiences and activists that she encountered. Wright claimed to have met white people throughout her travels who “treated her better than some of her own kind ever had at home.” Most of the warm receptions she recounted were from European intellectuals, laborers, and mothers who identified with parts of Wright’s story. Her international tour was a key component to the defense campaign because as the mother of two of the boys, she was considered the best suited to attest to their innocence. Her tour was also critical to the Party’s agenda because of the way she described her hardships as a Black woman surviving Jim Crow segregation in rural East Tennessee. Her compelling narrative painted an authentic picture of the harsh realities of Black Southern life that chilled European audiences to their core.

As the case and Wright’s tour gained more international notoriety, Black Southern workers also recognized the direct link between the exploitation of their labor and the Southern racial order. In his 1933 article “The Scottsboro Struggle”, James Allen, one of the Party’s leading theoreticians and the leader of the Chattanooga Communist Party, publicized the demands that Black workers made on behalf of the Scottsboro defendants and all exploited workers. Beginning with the first trial, many Black workers amplified the international call for the courts to appoint Black jurors. Although this demand was ultimately ignored, Allen explained that it inspired Black Southerners working on public work projects to demand more equitable working conditions. This demand was a manifestation of Black, Southern political mobilization against the racialized plantation economy. Such mobilizations were born out of a distinct political ideology that emerged throughout the Black South during the interwar period as a response to the local, national, and global exploitation of Black poor and working class Southerners.

While Wright’s tour was primarily concerned with asserting the defendants’ innocence, it also succeeded in redefining the reputation of the ILD. Black women and mothers back in the U.S. resonated with the Scottsboro mothers’ analyses of the intersection between labor struggles and the realities of Black womanhood and motherhood under Jim Crow. Among the numerous black women and mothers that publicly supported the ILD throughout the Scottsboro Campaign was Claudia Jones. Jones, who pledged her support to the Communist Party and Young Communist League in New York in 1936, would go on to become one of the most influential architects of the Popular Front in London throughout the 1940s.

Throughout her political career, Jones centered the lived experiences of oppressed Black people around the world. She would eventually publish “On the Right to Self-Determination for the Negro People in the Black Belt” in 1946, in which she likened the post-WWII political attacks against Black American people to those of the post WWI era, most notably the Scottsboro case. Throughout her analysis of the condition of Black life in the U.S., Jones highlighted the “…double oppression of the Negro people—as wage slaves and as Negros.” This rhetoric reflects Wright’s conceptualization of the Scottsboro case as a legal lynching of “class war prisoners” informed by the oppressive Southern racial caste.

Perhaps one of the most influential accomplishments of Wright’s tour was the way she and the Scottsboro mothers who affiliated with the Communist Party contributed to the galvanization of a European popular front of activists, intellectuals, and workers—including Jones—-who would later launch the movement against the Italian invasion of Abyssinia in 1935. The Scottsboro defense campaign served as one of the catalysts for the organization of the International Friends of Abyssinia movement, mainly headquartered in London. The defense campaign, including Wright’s tour, influenced the Popular Front’s political ideology through its multifaceted, global approach, that acknowledged the lived experiences of Black women and mothers as distinct components of workers’ struggles. In the years following the Scottsboro case, Popular Front activists utilized their myriad of experiences acquired throughout the global liberation struggles of the 1930s in order to substantively confront empire and the growing power of European fascist regimes. This coalition ultimately went on to serve among the leaders of the Post World War II liberation movement throughout African and Caribbean nations in the 1950s and 60s.

The interwar period was pivotal for the formation of this Pan-African liberation movement because it introduced new possibilities for international anti-imperial organizing. The Communist Party’s calculated framing of this case would eventually become the logics with which the Popular Front would sustain a movement for self-determination throughout the Diaspora. While Wright’s sons were both pardoned and released by 1944, the “last of the Scottsboro Boys” was not released from custody until 1976. She insisted until her passing that “it was the Russians who had saved her sons.” However, she was being much too modest. It was in fact Mrs. Wright who helped galvanize an international Popular Front that would eventually go on to challenge the imperial world order of domination.

0 notes

Text

Imperfect Unions: Sakai on Labor in the Early 1900s

In describing the turn by which immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe were ostracized within Euro-American concepts of identity, how the structure of the factory mirrored earlier structures of continual toil largely endured by immigrants, and how this was an attempt (openly and explicitly) at an effective preclusion of these workers from access to proletarian consciousness, Sakai makes a convincing case for both accepting the relatively uncontroversial notion that the means by which Whiteness is structured in America as going far beyond skin color, and developing that such that one begins adopting a paradigm of race that does not demarcate itself based on a superficial, liberal understanding that itself uses postmodern demarcations of identity to enforce white supremacy. Instead, in discussing the means by which understandings of labor and unionization were formed in relief of bourgeoisie control, how unions operated based on a sort of demarcation of rightful labor aristocracy, and how this eventually lead to the use of the “Red Scare” as a means of offering entry into whiteness, one can begin to discuss the demarcations necessary for Sakai’s account, and more generally the means by which the subaltern has been constructed throughout American history and into postmodern American ideology.

When Sakai talks about the Irish, the Italian, the Polish, Hungarian, Slovak, and mentions that among the many particular nationally-identified Catholicisms there were of course Jewish immigrants, he points towards one of the important means of reckoning with structures of Anglo-Saxon identity, as well as the coloniality necessary to mark whiteness. It is not simply enough to have a certain color of skin, although then again many of the new wave of immigrants did not possess even that, if examined closely. Rather, the processes of identification at hand was specifically based off of national character, and used immutable signs that went even more particular than most postmodern demarcations of whiteness, to the point of accusing immigrants of secretly being another race, or creating a sort of science of racial descent, a false archaeology of racial background that allowed for the preservation of the singularity described within Anglo-Saxon identity. This was retained in American support for the British Empire in their campaign against Boer settlers, as well as the further dispossession necessary to create the Afrikaner population, even in the opposition of imperial control seen in support of the Boers by “Irish Brigades” who joined the fight: the entire process of articulation of both an imperial power and the resistance to it was defined by the process of arbitrating which group of settlers was most appropriate for this territory. Unanimously, there was an effective acceptance of who could claim to be deserving of the land, and on what terms they could claim it, terms that specifically relied upon the expansion of empire to do such. In effect, the ideology of an expanding imperial structure needed the continual support of ideology, as well as the formation of proletarian classes that could serve as the laborers of the newly established settlement. With attempts at divesting from the instability of “Reconstruction” unable to entirely dispossess Afrikan workers, there was a recognition that new immigrants could fill roles akin to the ones filled already by Irish and Italian immigrants. Thus, even in spite of the general unease around the character of these immigrants, they were allowed in.

Even in calling these immigrants the “most proletarian...most militant European workers” in American history, Sakai claims that for all of that potential, the process of raising consciousness played out all the same as it has before, such that they “flirted with socialism – but in the end they preferred settlerism.” This turns toward the structure of labor aristocracy that Sakai discusses, the means by which a structural defense of empire is necessary for imperial structures of power, that one cannot realize an empire without imperialism as a process, and in fact that it was through a continual process of creating, accepting, and appropriating proletarian consciousness that America was able to create itself. The conditions under which workers were employed were reminiscent of postmodern structures of pay and the many ways in which bosses avoid already-existing minimum wage laws: by avoiding crossing a threshold into “full time” employment, by specifically structuring labor such that it was disposed of and rehired according to demand, more “acceptable” immigrants acting as foremen and otherwise retaining the stability of the laboring population at hand while immigrants were forced to work daily, for wages that could not support oneself (let alone a family) even if one assumed 365 straight days of labor, there was an effective tethering of these immigrants to their industrial lives that defined both the labor itself as that of-an-immigrant, and made the employment of a meaningfully “white” man in such a position unthinkable. That these positions involved dangerous, strenuous work and had enormously high mortality rates was acknowledged even at the time, but justified much in the same way that modern neoliberal justifications for sweatshop labor are offered, in that a sort of racialized fiction of social darwinism came to represent the notion of these new immigrants as animalistic, as defeated and thus rightfully bearing the burdens of the white man. These conditions, combined with the way in which intentional sequestering of workers lead to them living largely amongst their “own” and in close quarters, and the relatively large number of workers who came to America in order to avoid persecution for anarchist or socialist activities, lead to a genuine process of potential radicalization structurally contained within these workers, one seen at some moments of their attempts at unionization, especially in those of the IWW.

A lengthy discussion of the IWW’s victories is part of Sakai deconstructing part of the mythology of the IWW: as a legal and openly-operating union, one that was home to a number of class-conscious workers and immigrants but largely dependent upon the membership and support of settler workers, either in themselves or ideologically, there was a process of gain-and-defeat that characterized the IWW’s most prosperous days which is unmistakable as part of a larger process of growth and contraction. However, this does not stop Sakai from praising at least the early spirit and some of the actions of the IWW, specifically because they represented such a dramatic break from the processes of contingency seen in unions like the AFL and CIO. They operated openly, of course, but had a far more meaningful program of affinity, one that recognized commonality across industries and contingencies of a given industry as part of a larger means by which precarity was in fact preserved within factory and industrial labor as a whole. The IWW expanded far beyond industry, of course: one of its major constituent populations lay in hotel workers, a quickly expanding business given the means by which the railroad and the development of a “modern” culture of America as heir to European power lead to the development of American travel, the massive numbers of workers needed to provide sufficient luxury for these travellers in many ways still striated and informed by the previous ideology of slavery as part of settler culture, and its repetition through the creation of segregation and Jim Crow laws. The IWW was open about its critique of processes of capitalist appropriation, and of commonality that was not limited by the lines that traditionally demarcated unions. This proved to be an incredibly promising means of moving forward, one that would ultimately be abandoned.

During World War I, the IWW is sharply contrasted by the Bolsheviks, and the insistence upon seizing imperial unrest in order to unseat imperial power. Using the unrest of an empire straining itself to protect its holdings and expand all at once, the Bolsheviks seized power specifically due to the means by which Russian imperialism had weakened the overall structure of the Russian empire. That so many soldiers, workers, Russians themselves took part in this revolution is an incredible historical moment, perpendicular to the ideological settlerism that was urged by the IWW. The war was imperialist, of course! That much was accepted. But in response to government pressure, the IWW urged those in war-related industries to keep strikes quiet, short, to ultimately look towards the war as an eventually ending entity, as something that will be passed by and to use it as an opportunity to line their pockets with the overflow of bourgeoisie excess necessary to sustain the war itself. War profiteering was made into an individual choice for prosperity, a means of retaliating against the bosses that was no retaliation at all. Even then, the IWW’s role in striking during the war was minimal, accounting for only a handful of strikes considered impediments to the war effort, compared to those by the AFL.

Sakai goes on to talk about how, during and after WWI, antiblackness was a foundational structure of unionization and more generally union ideology, that the creation of an ideological vision of a race of strike-breakers was in fact part of creating the mythological figuration of Afrikan workers and understanding the means by which one could reckon with this continual antiblackness. It was in Afrikan veterans, those who had been treated worst in Europe and worst at home, that one found forces willing to oppose both workers and police inciting race riots, those who were using a spectre of Afrikan existence as a means of effectively breaking a strike while not offering any meaningful action toward it other than simply declaring it over. Sakai recounts one infamous incident where black workers were effectively tricked into breaking a strike: promised work, they (along with numerous white workers) were locked in train cars and shipped up to factories north of them, where they were told to begin laboring in the mills currently facing strikes. Upon realizing this, many were horrified, even though the strike explicitly was formed in favor of white workers, through the effort of white workers toward excluding Afrikan workers and thus creating a new, white industry. However, those who refused would be executed by company police. Thus, they worked until they found chances to escape, and when the strike failed it was in turn blamed upon them. Nevermind that Afrikan workers totaled at most 30,000 and were replacing a strike that numbered in the hundreds of thousands, not only were the moves effective, they created a new population to blame the strike on, strengthened the notion of the Union as a necessary means of controlling a race who lacked the decorum of their white counterparts. Similarly, in the West, agricultural organizers asked Japanese workers to strike along with them, but knowing that this would threaten the willingness of white workers to continue striking, asked that the workers effectively act in solidarity, despite being active participants in the exact same strike, accepting the exact same terms. Even in doing this, they were only acknowledged in an ancillary fashion, as if their contribution was lesser when in fact it came without the same recognition, same protection, as their union counterparts.

Even the Red Scare of the early 20th Century was, in large part, due to an act of purgatorial fire directed at this new settler population, according to Sakai. It was through this, through creating a means for new workers to enter into the consideration of whiteness, that the solidification of class against socialism could be codified. It was not a singular process of expulsion, but rather a process of privileging, a necessary means of cutting and then developing the population of workers. By creating this process of showing allegiance, by giving the opportunity to undergo a reterritorialization of identity, a transition into an American immigrant rather than mere immigrant, there was an effective act of codifying whiteness beyond the bounds normally found in nations such as England and other centers of imperialism. Thus, one can mark differently the American concept of whiteness and white supremacy from other ones on a global scale, while still accepting white supremacy as a force of hegemony. Commonly, discussions of the structure of race as expressed through xenophobic violence in the UK against Polish, Hungarian, and other Eastern European workers and immigrants relies upon Balkanization, processes of othering based in both a more traditional Orientalism, its restructuring through processes of anticommunist ideology, and the means by which this in turn creates a process of naturalization which may be wielded against a different colonial subaltern, such as Pakistani immigrants to the UK. The way in which “white” is defined within European parlance is worth differentiating because the specific arbitration involved in American global hegemony underscores its definition: it is only through whiteness that this further development may be made. It was made previously, and still can be relayed with those terms, but to say that it is different than racism in regard to the structural development of white supremacy is important specifically because of what it implies about the structure of white supremacy.

American hegemony and American concepts of whiteness, as well as the means by which white supremacy as developed within other White identities such as white supremacist ideas found in nations like Poland or Hungary or Russia, the means by which a certain national character is articulated through a reversal of Balkanization and a claimancy of a rightful whiteness is thus part of spreading fascist ideology, is part of creating what fascism can be once the settler has driven out the communist and reclaimed a supposed national identity. That this is paradigmatically coupled with antisemitism is no accident: the structure of antisemitism relies upon the creation of a sort of mythic Jewish population that is eternally nomadic, nomadic not due to the continual persecution they face, but because of a sort of internal turn, a turn toward themselves that is itself only marked by antisemitic understandings of antisemitic violence. It contains a cyclic, infinite reminder of itself structured by aesthetics of Catholic guilt, and absolutely foundational to the European and Euro-American concept of the self. While anti-Catholic ideology was a major component of American whiteness and its arbitration, the way in which that has become secondary in structuring white supremacy and moreover the way in which Catholicism has been used as part of finding commonality between fascist tendencies in different ideological structures is absolutely based both in the ideology of theological debt as structured by hegemonic articulations of Catholic ideas of justice, and a realization of antisemitic violence. Discussing these differences, knowing the archaeological descent of postmodern fascism from the structures of American consideration of the immigrant is vital to understanding fascism after neoliberalism, fascism after globalization.

4 notes

·

View notes