#jerome pétion

Text

Some primary sources

I plan to add more whenever I find more.

Historie Parlamentaire de la Révolution Française ou Journal des Assemblées Nationales, depuis 1789 jusqu’en 1815

Volume 1 (May 1789)

Volume 2 (June-September 1789)

Volume 3 (September-December 1789)

Volume 4 (December 1789-March 1790)

Volume 5 (March-May 1790)

Volume 6 (May-August 1790)

Volume 7?

Volume 8 (November 1790-February 1791)

Volume 9 (February-May 1791)

Volume 10 (May-July 1791)

Volume 11 (July-September 1791)

Volume 12 (September-December 1791)

Volume 13 (January-March 1792)

Volume 14 (April-June 1792)

Volume 15 (June-July 1792)

Volume 16 (July-August 1792)

Volume 17 (August-September 1792)

Volume 18 (September 1792)

Volume 19 (September-October 1792)

Volume 20 (October-November 1792)

Volume 21 (November-December 1792)

Volume 22 (December 1792-January 1793)

Volume 23 (January 1793)

Volume 24 (February-March 1793)

Volume 25 (March-April 1793)

Volume 26 (April-May 1793)

Volume 27 (May 1793)

Volume 28 (July-August 1793)

Volume 29 (September-October 1793)

Volume 30 (October-December 1793)

Volume 31 (November 1793-March 1794)

Volume 32 (March-May 1794)

Volume 33 (May-July 1794)

Volume 34 (July-August 1794)

Recueil des actes du comité de salut public

Volume 1 (August 12 1792-January 21 1793)

Volume 2 (January 22-March 31 1793)

Volume 3 (April 1-May 5 1793)

Volume 4 (6 May-18 June 1793)

Volume 5 (19 June-15 August 1793)

Volume 6 (15 August-21 September 1793)

Volume 7 (22 September-24 October 1793)

Volume 8 (25 October-26 November 1793)

Volume 9 (27 November-31 December 1793)

Volume 10 (1 January-8 February 1794)

Volume 11 (9 February-15 March 1794)

Volume 12 (16 March-22 April 1794)

Volume 13 (23 April-28 May 1794)

Volume 14 (29 May-7 July 1794)

Volume 15 (8 July-9 August 1794)

Recueil de documents pour l’histoire du club des Jacobins de Paris

Volume 1 (1789-1790)

Volume 2 (January-July 1791)

Volume 3 (July 1791-June 1792)

Volume 4 (June 1792-January 1793)

Volume 5 (January 1793-March 1794)

Volume 6 (March-November 1794)

Histoire du tribunal révolutionnaire de Paris: avec le journal de ses actes.

Volume 1

Volume 2

Volume 3

Volume 4

Volume 5

Papiers inédits trouvés chez Robespierre, Saint-Just, Payan etc

Volume 1

Volume 2

Volume 3

Oeuvres complètes de Robespierre

Volume 1 (Robespierre à Arras)

Volume 2 (Les œuvres judiciaires)

Volume 3 is the correspondence, listed below

Volume 4 (Le defenseur de la Constitution)

Volume 5 (lettres à ses comettras)

Volume 6 (speeches 1789-1790)

Volume 7 (speeches January-September 1791)

Volume 8 (speeches October 1791-September 1792)

Volume 9 (speeches September 1792-June 27 1793)

Volume 10 (speeches June 27 1793-July 27 1794)

Oeuvres de Maximilien Robespierre (not the same as Oeuvres completés)

Volume 1

Volume 2

Volume 3

Oeuvres de Jerome Pétion

Volume 1

Volume 2

Volume 3

Volume 4

Oeuvres complètes de Saint-Just

Volume 1

Volume 2

Oeuvres littéraires de Hérault de Séchelles (1907)

Oeuvres de Danton (1866)

Discours de Danton (1910) by André Fribourg

Works by Desmoulins

La France Libre (1789)

Discours de la Lanterne aux Parisiens (1789)

Révolutions de France et de Brabant (1789-1791)

Volume 1 (number 1-13)

Volume 2 (number 14-26)

Volume 3 (number 27-39)

Volume 4 (number 40-52)

Volume 5 (number 53-65)

Volume 6 (number 66-79)

Volume 7 (number 80-86)

La Tribune des Patriots (1792) (all numbers)

Le Vieux Cordelier (1793-1794) (all numbers)

Jean Pierre Brissot démasqué (1792)

Histoire des Brissotins (1793)

Correspondences

Correspondance de Maximilien et Augustin Robespierre (1926)

Correspondance de George Couthon (1872)

Correspondance inédit de Camille Desmoulins (1836)

Correspondance inédite de Marie-Antoinette (1864)

Billuad-Varennes — mémoires et correspondance

Correspondance de Brissot

Lettres de Louis XVI: correspondance inédite, discours, maximes, pensées, observations etc (1862)

Lettres de Madame Roland (1900)

Volume 1

Volume 2

Correspondance inédite de Mlle Théophile Fernig (1873)

Journal d’une bourgeoise pendant la Révolution 1791-1793 by Rosalie Jullien (1881)

Memoirs

Memoirs of Bertrand Barère

Volume 1

Volume 2

Volume 3

Volume 4

Memoirs of Élisabeth Lebas

In French

In English

Mémoires de Charlotte Robespierre sur ses deux frères (1835)

In French

In English

Memoirs of Joseph Fouché

Volume 1 (English)

Volume 2 (French)

Mémoires de Brissot (1877)

Mémoires inédits de Pétion et mémoires de Buzot et Barbaroux (1866)

Memoirs of Barras — member of the Directorate (1899)

Mémoires inédits de madame la comtesse de Genlis depuis 1756 jusqu’au nos jours

Volume 1

Volume 2

Volume 3

Volume 4

Volume 5

Volume 6

Volume 7

Volume 8

Volume 9

Volume 10

Mémoires de Madame Roland

Volume 1

Volume 2

Mémoires de Louvet (1862)

Memoirs of the Duchess de Tourzel: Governess to the Children of France During the Years 1789, 1790, 1791, 1792, 1793 and 1795

Volume 1

Volume 2

Révélations puisées dans les cartons des comités de salut public et de sûreté générale, ou Mémoires (inédits) de Sénart, agent du gouvernement révolutionnaire (1824)

Free books

Danton (1978) by Norman Hampson (borrowable for an hour, renewable every hour)

Robespierre (2014) by Hervé Leuwers (borrowable for an hour, renewable every hour)

Collot d’Herbois — légendes noires et Révolution (1995) by Michel Biard

Choosing Terror (2014) by Marisa Linton

The Coming of the Terror in the French Revolution (2015) by Timothy Tackett

Augustin: the younger Robespierre by (2011) by Mary-Young

Journaliste, sans-culotte et thermidorien: le fils de Fréron, 1754-1802, d’après des documents inédits (1909) by Raoul Arnaud

Un Champion de la Royauté au début de la Révolution - François Louis Suleau (1907)

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Camille Desmoulins and his wife — passages from the history of the dantonists (1876) by Jules Claretie

Vadier, président du Comité de sûreté générale sous la Terreur d’après des documents inédits (1896) by Albert Tournier

Mémoires historiques et militaires sur Carnot (1824)

Le Puy-de-Dôme en 1793 et le Proconsulat de Couthon (1877) by Francisque Mège

Le procès des Dantonistes, d'après les documents, précédé d'une introduction historique. Recherches pour servir à l'histoire de la révolution française (1879) edited by Dr. Jean François Eugène Robinet

Robert Lindet, député à l'Assemblée législative et à la Convention, membre du Comité de salut public, ministre des finances : notice biographique (1899) by Amand Montier

Prieur de la Côte-d'Or (1900) by Paul Gaffarel

Un épicurien sous la Terreur; Hérault de Séchelles (1759-1794); d'après des documents inédits (1907) by Emile Dard

Twelve Who Ruled (1941) by R. R. Palmer (borrowable for an hour, renewable every hour)

Bertrand Barère: A Reluctant Terrorist (1963) by Leo Gershoy (borrowable for an hour, renewable every hour)

Saint-Just : sa politique et ses missions (1976) by Jean-Pierre Gross (borrowable for an hour, renewable every hour)

The Glided Youth of Thermidor (1993) by François Gendron

Pauline Léon, une républicaine révolutionnaire by Claude Guillon

Billaud-Varenne: Géant de la Révolution (1989) by Arthur Conte

When the King Took Flight (2003) by Timothy Tackett (borrowable for an hour, renewable every hour)

Joseph Le Bon, 1765-1795; la terreur à la frontière (1932) by Louis Jacob

Volume 1

Volume 2

Resources shared by other tumblr users (thank you all very much!!!)

Resources shared by @iadorepigeons

Resources shared by @georgesdamnton

Resources shared by @rbzpr:

Fabre d’Eglantine resources shared by @edgysaintjust

Saint-Just resources shared by @sieclesetcieux

Saint-Just resources shared by @orpheusmori

Marat resources shared by @orpheusmori

My own translations

Lucile Desmoulins’ diary (1788, 1789, 1790, 1792-1793)

Charlotte Robespierre et ses amis (1961)

Laponneraye on the life of Charlotte Robespierre (1835)

Abbé Proyart on the childhood of Robespierre (1795)

Regulations for the internal exercises of the College of Louis-le-Grand (1769)

Regulations for law students at Louis-le-Grand (1782)

Belongings left by Danton, Fabre and Desmoulins after their arrest

Letters from Robespierre’s father

Robespierre family timeline

#frev resources#frev#french revolution#maximilen robespierre#augustin robespierre#robespierre#george couthon#couthon#camille desmoulins#desmoulins#joseph fouché#fouché#charlotte robespierre#elisabeth lebas#elisabeth duplay#billaud-varennes#jerome Pétion#jacques-pierre brissot#saint-just

450 notes

·

View notes

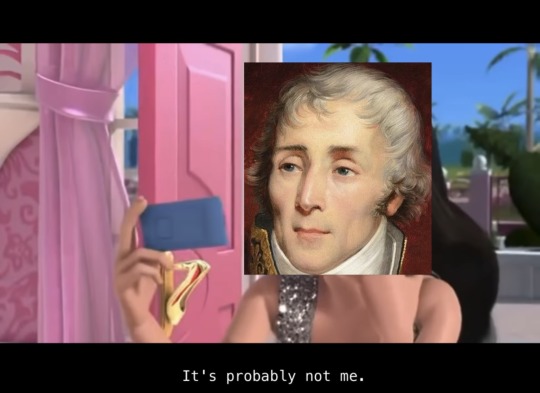

Photo

But who is it really?

#frev#desmoulins#camille desmoulins#maximilen robespierre#robespierre#saint-just#louis antoine de saint just#pétion#jerome pétion#fouché#joseph fouché#being responsible for the death of all your besties is neat#especially when you’re always responsible in different ways…#poor Pétion never gets mentioned as a robespierre BFF#despite robespierre describing him as ”the one of my colleagues to whom i am most closely bound”#”both by works principles common perils as much as by the ties of the most tender of friendships”

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

The suicide of Pétion and Buzot (graphic)

Source: La liberté ou la mort: mourir en député 1792-1795 by Michel Biard (2015) chapter 1.

For Buzot and Pétion, whose bodies are found in the countryside after their suicide, tracking down accessories/accomplices can be difficult, given the very condition of the corpses which offers witnesses a real plunge into horror. [1] Indeed, on 7 Messidor Year II (June 25, 1794), a quarter of an hour before midnight, the justice of the peace of the district of Castillon, "[...] warned by public outcry that two corpses had been discovered in a patch of wheat [...],” went to the scene, taking with him the description of the proscribed representatives which had been given to him by commissioners appointed by Julien, himself sent from the Committee of Public Safety. He notes first of all, without further details, the night not helping with the recognition of the bodies, "[...] that the two corpses have been devoured by the dogs, the top of the body being very infected by it [...]". He also discovered various personal effects and weapons on the spot, including seven pistols and two swords, which he had deposited at the common house of Saint-Magne, then he left the bodies under guard and went back to bed. Does sleep remain accessible to him after such a vision? His night is in any case short, since the next day, at six o'clock in the morning, he goes to the scene a second time and finds there the commissioners sent by Julien. This time in the light of day, he undertakes to describe the two bodies with precision. For the first, he notes: "[...] we found a corpse lying on its back, with a very black face and the teeth on the right side of the lower and upper jaw broken [...] said corpse is being gnawed by worms in the neck and has gut coming out of its lower abdomen and is revolting and unapproachable". Then the justice of the peace observes: “For the second corpse [...] the face, the whole upper body is being devoured, only the bones, hair and greyish hairbreadth remaining there [...].” Under this second body, he discovers yet another pistol, probably the one used for the suicide. Unlike the first corpse, where the black face and the shattered jaw easily attest that the man shot himself in the mouth, the second is reduced to such a state that only the presence of the pistol indicates the suicide. The dreadful report continues as follows: “Having wanted to have the said corpses undressed to be represented to those who gave them asylum, the rotten limbs followed the fabric; the citizen Boulanger Lanauze, health officer, domiciled in Castillon, required to go to the scene, considered that it was not possible without danger for those who would be employed to proceed; consequently, in the opinion of the commissioners, we left the corpses under the supervision of the municipal officers of Saint-Magne for their burial, taking the necessary precautions to avoid unhealthy air. According to the information given to us by the said commissioners and the verification made by them [...] it is indubitable that these two corpses are those of Buzot and Pétion, ex-deputies outlawed as traitors to the fatherland [2]. This same 8 Messidor (June 26), the two bodies did not even obtain a burial in consecrated ground, due to their appalling state: “[...] the two corpses could not without danger be transported to the cemetery of this commune, according to the report of citizen Lanauze, health officer; we had two six foot deep pits made, in one of which Buzot's body was laid; and in the other that of Pétion, which we then had covered with earth [...].”

[1] Recognition report of the bodies of Buzot and Pétion (Châteaudun library, collection of manuscripts, cart. 6/7/17). The date of 30 Prairial Year II (June 18, 1794), proposed by historiography for this double suicide, is incorrect. Similarly, Pierre Bertin-Roulleau claimed that the arrest of Barbaroux and therefore the escape of his two companions dated from that same day, because all three left their hiding place after seeing Guadet and Salle arrested pass in front of them (La Fin des Girondins. Histoire des derniers Girondins, après leur proscription, dans la Gironde. Septembre 1793-juin 1794, Bordeaux, Féret, 1911, p. 163-164). Barbaroux was actually arrested on 6 Messidor and guillotined the next day (June 24), while Buzot and Pétion managed to flee. The two fugitives committed suicide at the end of the afternoon or during the night of the 6th to the 7th. Doctors Gérard Lahon, expert at the Court of Appeal of Rouen, and Jean-Georges Anagnostides, expert approved by the Court of cassation, consulted on this document, affirm that the death can date back to 6 Messidor around six o'clock in the evening, which leaves thirty-six hours between death and the examination carried out on the 8th at six o'clock in the morning (cf. following note for their medico-legal report).

[2] Ibid. Gérard Lahon and Jean-Georges Anagnostides underline that "the putrefaction of a body, which in general begins to be clinically visible twelve hours after death, is all the more rapid as the surrounding atmosphere is hot, even stormy, and the corpse is abandoned on the ground, in the open air, in a context of bleeding wounds". Abandoned in the sun in a field, it fatally very quickly attracts predatory animals, attracted by the smell, which feed first on the areas where the blood stagnates, which explains the state of the upper body. In addition, the corpse "attracts flies which land and lay eggs in the vicinity of it, or even in it, where the blood has flowed, which gives birth to larvae (or worms)". Finally, "the putrefaction of a corpse, especially if it remains exposed in a hot atmosphere, can very well be accompanied, from thirty-six hours after death and a fortiori beyond, by the following physical phenomena: phlyctenular desquamation (bullous appearance of the skin) explaining an epidermis that sticks to clothing; a production of endogenous gas generating a secondary intra-abdominal hyper-pressure, leading to the appearance outside the belly of an intestinal loop exiting through a cutaneous orifice” (orifice which may have been created by a stab, but here more likely by an animal).

16 notes

·

View notes