#buzot

Text

Frev nicknames compilation

Maximilien Robespierre – the Incorruptible (first used by Fréron, and then Desmoulins, in 1790).

Augustin Robespierre – Bonbon, by Antoine Buissart (1, 2), Régis Deshorties and Élisabeth Lebas. Élisabeth confirmed this nickname came from Augustin’s middlename Bon.

Charlotte Robespierre – Charlotte Carraut (hid under said name at the time of her arrest, also kept it afterwards according to Élisabeth Lebas). Caroline Delaroche (according to Laignelot in 1825, an anonymous doctor in 1849 and Pierre Joigneaux in 1908).

Louis Antoine Saint-Just – Florelle (by himself), Monsieur le Chevalier de Saint-Just (by Salle and Desmoulins)

Jean-Paul Marat – the Friend of the People (l’Ami du Peuple) (self-given since 1789, when he started his journal with the same name)

Georges-Jacques Danton – Marius (by Fréron and Lucile Desmoulins).

Éléonore Duplay – Cornélie (according to the memoirs of Charlotte Robespierre and Paul Barras. Barras also adds that Danton jokingly called Éléonore “Cornelie Copeau, the Cornelie that is not the mother of Gracchus”)

Élisabeth Duplay – Babet (by Robespierre and Philippe Lebas in her memoirs)

Jacques Maurice Duplay – my little friend (by Robespierre), our little patriot (by Robespierre)

Camille Desmoulins – Camille (given by contemporaries since 1790. Most likely a play on the Roman emperor Camillus who saved Rome from Brennus in the 4th century like Camille saved the revolution on July 12, and not a reference to Camille behaving like a manchild to the people around him like is commonly stated.) Loup (wolf) by Fréron and Lucile (1, 2), Loup-loup by Fréron (1, 2), Monsieur Hon by Lucile.

Lucile Desmoulins – Loulou (by Camille 1, 2), Loup by Camille, Lolotte (by Camille (1, 2), Rouleau by Fréron (1, 2) and Camille, the chaste Diana (by Fréron), Bouli-Boula by Fréron (1, 2).

Horace Desmoulins – little lizard (Camille), little wolf (Ricord), baby bunny (Fréron).

Annette Duplessis (Lucile’s mother) — Melpomène (by Fréron), Daronne (by Camille)

Stanislas Fréron – Lapin (bunny) (by himself (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) and Lucile. According to Marcellin Matton, publisher of the Desmoulins correspondence and friend of Lucile’s mother and sister, Fréron obtained this nickname from playing with the bunnies at Lucile’s parents country house everytime he visited there, and Lucile was the one who came up with it). Martin by Camille and himself (likely a reference to the drawing ”Martin Fréron mobbed by Voltaire” which depicts Fréron’s father Élie Fréron as a donkey called ”Martin F”.)

Manon Roland — Sophie (by herself in a letter to Buzot).

Charles Barbaroux — Nysus by Manon Roland

François Buzot — Euryale by Manon Roland

Pierre Jacques Duplain — Saturne (by Fréron)

Guillaume Brune — Patagon (by Fréron)

Antoine Buissart (Robespierre’s pretend dad from Arras) — Baromètre (due to his interest in science)

Comment who had the best/worse nickname!

#french revolution#robespierre#danton#desmoulins#buzot#barbaroux#marat#fréron#maximilien robespierre#charlotte robespierre#augustin robespierre#camille desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#horace desmoulins#stanislas fréron#georges danton#manon roland#saint-just#louis antoine de saint just#élisabeth lebas#élisabeth duplay#éléonore duplay#fréron really likes nicknames…#frev compilation

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

JUST FOUND OUT MADAME ROLAND AND BUZOT FELL IN LOVE WITH EACH OTHER...AND MONSIEUR ROLAND KNEW?!

Y I K E S

this is kind of sad actually

Also, never tell Danton ANYTHING if you don’t want it to get out al;skddsdfas

#the girondins#madame roland#buzot#danton#camille#the dantonist inability to shut the fuck up strikes again#don't tell danton anything because he WILL tell camille and then camille will tell the world

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi,

Boulant mentions that Buzot accused Saint-Just of embezzlement and that Saint-Just was further accused of speculation when he bought national property, especially when he supposedly acquired national property in 1793. Do you happen to know anything about these claims? Because I have read quite a few biographies about Saint-Just and this is the first time I have come across anyone even implying that he was not 100% honest when it came to money.

Thanks a lot in advance.

The moment I read this, I thought about Olivier Blanc, the resident conspiracy theorist. He is big on proving that Montagnards had a lot of money and were all involved in speculations with property to amass a great wealth. His sources are highly dubious - it's not even Thermidorized view in the strict sense of the word; the man simply does not know (or pretends he doesn't know) how to analyze a source. For example, he finds a slander pamphlet that someone wrote randomly about someone and take it at face value. (Like when he took a pamphlet allegedly written by Tallien about being the lover of his father's master at face value.) It doesn't mean that these sources are useless - they can tell us a lot about what people at the time gossiped about and what tensions/slanders existed, AND there could be some truth in some of them, but they need to be approached carefully. (It would be like claiming Marie Antoinette definitely took female lovers just because revolutionary slander pamphlets said so.)

Another Blanc's claim was that the Duplays were super wealthy and had properties all around France. He provides as a "proof" the death certificate of a Duplay boy who died as a baby outside of Paris. It is clear to anyone that the child was given to a wet nurse, which was a common practice at the time. But nah, Blanc claims it's the proof that Duplays had property outside of Paris! (Even though the death certificate gives Paris as the parent's address).

Stuff like that. So nah, Blanc's cannot be trusted on his word. He is good at digging up sources, but he doesn't know how to interpret them. It is very concerning to me that Boulant, the author of the newest study on SJ, not only cites Olivier Blanc (his ramblings from Geneanet, since no reputable historical journal would publish it), but thanks him in the foreword! So, all this stuff is taken directly from Blanc, and is therefore highly unreliable, to say the least.

Is there some truth to it? We know SJ bought some property around 1791 (early 1792?) in order to have enough property to be eligible to be elected. At the time, there was still the requirement that you had to be rich enough to become a deputy. He took a loan to buy this property, but in the end, it was not needed because the wealth requirement was removed from the 1792 elections.

I don't know anything about other stuff. I cannot claim that it's absolutely untrue, because we have no proof. But SJ was more broke than anything, and I guess the idea of buying nationalized property is to amass wealth (which is what Blanc tried to prove all this time). No trace of this wealth is found (same for Robespierre, Le Bas, Couthon, etc.) so I guess Olivier Blanc has to work harder to prove his theories. What he offers so far is not a proof.

#ask#frev#saint-just#i don't want to go 'sj would never'#but what we know does not support blanc's theories#he just doesn't interpret sources properly#i am more concerned that boulant's book relies on blanc#i had no idea until now#that's... not a good sign

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roland de La Platière Manon (Jeanne Marie) (Mme Roland) - Mémoires

Madame Roland est née en 1754. C’est une femme éduquée qui épousa Jean-Marie Roland de la Platière, ministre sous la Révolution, et devint une femme influente politiquement grâce à son intelligence et aux nombreuses personnalités politiques qu’elle reçut dans son salon: Robespierre, Marat, Buzot, Pétion, Danton, etc.

Dans ses Mémoires, elle raconte son emprisonnement en 1793 dans deux prisons différentes (La Conciergerie et Sainte-Pélagie) lors de la proscription des Girondins, pendant que son mari et une partie de ses amis sont en fuite.

Elle a beaucoup collaboré avec son mari et le défend sur tous les points, mais sait être acerbe et virulente quand elle fait le portrait des personnes qui l’ont trahie, Danton et Robespierre: «Ce Robespierre, qu’un temps je crus honnête homme, est un être bien atroce ! comme il ment à sa conscience et comme il aime le sang!»

Résiliente, prête à mourir sous l’échafaud des nouveaux révolutionnaires, elle défend ses droits et reste ferme jusqu’au bout pour décrier l’injustice d’une telle arrestation sans motifs valables et sans jugement. Elle jette un regard acéré et critique sur tous ces hommes de pouvoir.

«Je pressens les hommes par le tact, je les juge par leur conduite comparée dans ses différents temps avec leur langage: mais moi, je me montre tout entière et ne laisse jamais douter qui je suis.»

Grâce à ces Mémoires, on entre dans toutes les intrigues de cette époque révolutionnaire, on côtoie de nombreux personnages plus ou moins connus de cette période agitée, et on apprend aussi à connaître les conditions d’emprisonnement, les abus et la corruption dans ce milieu, mais aussi la gentillesse de certaines gardiennes.

Madame Roland mourra sous la guillotine le 8 novembre 1793, sans avoir revu sa fille de 12 ans.

Téléchargements : ePUB - PDF - PDF (Petits Écrans) - Kindle-MOBI - HTML - DOC/ODT

Read the full article

1 note

·

View note

Text

HERE WE ARE WITH A NEW POST OF THE MBTI #FREV BOYS

ISTJ:

Martial Joseph Armand Herman

Georges Couthon

ISFJ:

Françoise Nicolas Léonard Buzot

Marie-Jean Hérault de Séchelles

ESTJ:

Antoine Quentin Fouquier de Tinville

ESFJ:

Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac

Jean-Sylvain Bailly

#french revolution#montagnards#frev#frev history#revolution francaise#french history#bertrand barere#martial herman#georges couthon#buzot#bailly#jean sylvain bailly#mbti#mbti frev

7 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Le voilà donc enfin achevé CET ACTE CONSTITUTIONNEL, ce chef-d’œuvre de la plus perfide politique, qui, sous le voile de la sagesse, dépouille la nation de sa souveraineté, et le citoyen de tous ses droits, qui a renversé toutes les barrieres opposées au pouvoir absolu des ministres, qui rend légal le despotisme, et la personne du despote sacrée et inviolable, qui remet la liberté individuelle sous la main des fonctionnaires public, et la liberté nationale sous la main des agens royaux, ses mortels ennemis, qui autorise le massacre des amis de la patrie, calomniés comme des factieux, au nom de la tranquillité et de la paix, et qui traîne au supplice ses defenseurs au nom de la justice et de la liberté.

Ce honteux monument de la vénalité de nos chargés de pouvoirs, et de notre asservissement, n’est pas simplement achevé, il vient d’être humblement présenté au despote par une nombreuse députation ; composée de Thouret, Duport, Desmeuniers, Chapelier, Syeyes, Dumetz, Regnaud, Biogle, Target, Lameth, Barnave, d’André, et des autres coquins qui ont eu le plus de part à sa confection, auxquels ils ont accollé MM. Buzot, Prieur et Pethion ; dans l’espoir que le public stupide prendrait les accolites pour des gens de bien.

L’Ami du peuple, n° 548, 3 septembre 1791, p. 3.

#il y a 229 ans#Révolution française#Marat#constitution de 1791#Prieur de la Marne#Buzot#Pétion#l'ami du peuple#Jean Paul Marat#Pierre Louis Prieur#François Buzot#Jérôme Pétion#Thouret#Adrien Duport#Desmeunier#Le Chapelier#Sieyès#Boutteville-Dumetz#Regnaud de Saint-Jean-d'Angély#Target#Lameth#Barnave#d'André#Dandré#1791#3 septembre 1791

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Indictment of the Girondins (3 October 1793)

Acte d'Accusation against several Members of the National Convention, presented in the name of the Committee of General Security, by André Amar, member of this committee, On the 13th day of the first month of Year II of the French Republic, & in the old manner on 3 October. […]

There is a conspiracy against the unity and indivisibility of the Republic, against the liberty & security of the French people. Among the authors & accomplices of this conspiracy, are Brissot, Gensonné, Vergniaud, Guadet, Grangeneuve, Pétion, Gorsas, Biroleau, Louvet, Valazé, Valady, Fauchet, Carra, Isnard, Duchâtel, Barbaroux, Sales, Buzot, Sillery, Ducos, Fonfrède, Le Hardi, Lanjuinais, Fermont, Rouyer, Kersaint, Manuel, Vigier & others. The proof of their crimes results from the following facts. […]

You can find Amar’s full report on the indictment of the Girondins in the Archives Parlementaires, tome 75, p. 522ff.

Source: Indictment of the Girondins

#french revolution#frev#girondins#1793#year ii#gironde#amar#brissot#gensonné#vergniaud#guadet#petion#pétion#gorsas#louvet#valazé#carra#isnard#barbaroux#buzot#ducos#lanjunais

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

여왕과 연하 애인

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok, so I just found out that the National Convention had made a decree against the Girondin Buzot, that “the house occupied by Buzot be demolished, and never to be rebuilt on this plot. [Instead,] a column shall be raised, on which there shall be written: «Here was the sanctuary of the villain Buzot who, while a representative of the people, conspired for the overthrow of the French Republic»”.

Doesn’t it feel really like the “Lyon shall be destroyed” decree?

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Tremendous stage! All types; human, inhuman, and superhuman were there. Epic gathering of antagonism; Guillotine avoiding David, Bagire insulting Chabot, Gaudet jeering at Saint-Just, Vergniaud scorning Danton, Louvet attacking Robespierre, Buzot denouncing Egalité, Chambon branding Pache,—all execrating Marat.

Ninety-three, Victor Hugo.

#ninety three#victor hugo#jean paul marat#jean nicolas pache#nicholas chambon#francois buzot#robespierre#louvet#danton#pierre victurnien vergniaud#saint just#marguerite elie guadet#francois chabot#bagire#jacques louis david#joseph ignace guillotin#the convention#french revolution#historical book#french literature#quote

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you know anything about the supposed affair between Madame Roland and Buzot as well as maybe her relationship with Barbaroux?

Thank you!

The first time Manon mentions Buzot in her conserved correspondence is in a letter to Brissot dated April 28 1791 — ”your good friend Pétion got excited and spoke of it all the better; but why do the vigorous Robespierre and the wise Buzot not give themselves up to the advantage of written speeches, to the kind of reason for which one can then add the magic of declamation?” We do however have to wait until the fall of the same year to find a letter indicating the two were also becoming personal friends, it is dated September 9 1791 and adressed to Jean-Marie Roland:

I had promised myself to write to Madame Buzot; she could not imagine my sensitivity to the testimonials of interest that she has been kind enough to give me; I left her with a sort of haste, because I had to tear myself away, but that moment never leaves my heart. Tell her and her worthy husband how dear they are to us; you can speak for both of us, since you love them as much as I do.

During her interrogation held after her arrest on June 1 1793, Manon admitted her relationship with Buzot had started earlier than what her correspondence reveals, claiming she and her husband ”had been linked since the Constituent Assembly with Brissot, Pétion and Buzot” and ”that she knew them with Roland and through Roland; and that she had for them the degree of esteem and attachment each of them seemed to deserve according to her.” In her memoirs, she also reports the following about her relationship with the Buzots during the period of the Constituent Assembly:

During the Constituent Assembly, at the time of the revision, I was one day with Buzot's wife, when her husband returned from the Assembly very late, bringing Pétion for dinner. It was the time when the court had them treated as factious, and painted them as intriguers, all occupied in stirring up and agitating. After the meal, Pétion, seated on a large ottoman, began to play with a young hunting dog with the abandonment of a child; they both let go and fell asleep together, snuggled on top of each other: four people conversing did not prevent Pétion from snoring. ”So here we have this rebel,” said Buzot, laughing; ”we were looked askance on leaving the room, and those who accuse us, very agitated for their party, imagine that we are to maneuver!”

Buzot did not live very far from us; he had a wife who did not seem on the same level as him, but who was honest, and we saw each other frequently. When the success of Roland's mission, relating to the debts of the commune of Lyons, enabled us to return to Beaujolais, we remained in correspondence with Buzot and Robespierre; it was better followed with the former; there reigned between us more analogy, a greater basis for friendship, and a fund otherwise rich to maintain it. It became intimate, unalterable; I will tell elsewhere how this connection was tightened.

It’s most likely after the two were reunited for the National Convention in September 1792 that the relationship became more than platonic — at least it’s only after this we find signs of this being the case. Throughout the latter months of 1792 we have a series of frosty letters exchanged between Manon and her protégé Lanthenas, which all seem to allude to the affair (check out page 261-262 of Marriage and Revolution: Monsieur and Madame Roland for an analysis of these). On December 25 1792 we also find a note Manon sent to Servan, telling him that ”after my husband, my daughter and one other person, you are the only one to which I make [my portrait] known.” In her memoirs, she further claims to have visited Buzot’s wife only a single time since the beginning of the Convention, a choice we might imagine was influenced by the growing feelings between her and François:

As for the alleged confabulations at the house of Buzot's wife, no charge in the world is as ridiculous. Buzot, whom I had seen a great deal during the Constituent Assembly, with whom I had remained in friendly correspondence; Buzot, whose pure principles, courage, sensitivity, gentle manners, inspired me with infinite esteem and attachment, came frequently to the Hôtel de l'Intérieur: I only went home to his wife's once since their arrival in Paris for the Convention.

Jean-Marie also found out about the relationship. In her memoirs, Manon writes the following about it:

I honored and cherished my husband like a sensitive daughter adores a virtuous father, to whom she would even sacrifice her love. But I found the man who could be that love, and, while I remained faithful to my duties, my ingenuous nature was unable to conceal the feelings that I was suppressing for their sake. My husband, a man of extreme sensitivity, both in affection and self-love, was unable to tolerate the slightest alteration of his rule; his imagination painted things in the darkest colours, his jealousy irritated me; happiness had fles far away from us, and both of us were unhappy.

The affair also didn’t go unnoticed by contemporaries. In his Étude sur Madame Roland, Charles-Aimé Dauban cites the following passage from the Moniteur on June 15 1793:

Duroy: I'm from the same department as Buzot; I have worked with him, and I am convinced that he would sacrifice the whole republic to satisfy his ambition. The marked incivility of Buzot dates from September 13; at that time, he received a letter from the wife of Roland (laughter is heard); he read it to me: the wife of Roland complained that the revolutionary commune had issued a warrant for the arrest of the virtuous Roland.

Dauban suggests the reason people laughed after hearing Manon mentioned is because they knew about the relationship between her and Buzot.

Their relationship also appears to be what Desmoulins is talking about in his Histoire des Brissotins (May 1793) when he writes: ”Jérôme Pétion told Danton in confidence that ”what makes poor Roland saddest is the fact people will discover his domestic sorrows and how bitter being a cuckold is to the old man, troubling the serenity of that great soul.” The girondin Louvet also seems to be alluding to it in his memoirs (1795) when remembering the day he said farewell to Buzot, Pétion and Barbaroux for the very last time:

[Pétion, Buzot and Barbaroux] were going, a few leagues away, towards the sea, to seek an invertan asylum; with what sorrow we bade each other farewell! Poor Buzot, he carried deep in his heart very bitter sorrows, which I alone knew, and which I must never reveal.

And the deputy René Vavasseur reported in his memoirs: ”Salles and Buzot were the most irritable of the party. We know one of the causes of Buzot's excessive irritability.”

Manon was arrested on June 1 1793, while Buzot fled Paris to avoid the same fate. They would never see each other again. We do however know of five letters Manon wrote to Buzot while in captivity (first published in 1864 within Charles-Aimé Dauban’s Étude sur Madame Roland et son temps). These, it would appear, are the only letters exchanged between them that have been conserved, or at least published (the letters Buzot wrote to Manon that the latter mentions, would for example appear to have gone missing). Since all five letters are quite long I’ve decided to only include the parts dealing with their relationship here:

June 22

How I reread them! I press them to my heart, I cover them with my kisses; I no longer hoped to receive any!... I had in vain searched for news of Madame Ch(alot); I had once written to M. Le Tellier, to É(vreux) so that you may have a sign of life from me; but the post is violated; I didn't want to send you anything, convinced that your name would cause the letter to be intercepted and that I would have compromised you. I came here, proud and calm, forming wishes and still harboring some hope for the defenders of liberty, when I learned of the decree of arrest against the twenty-two; I cried: My country is lost! I was in the most cruel anguish until I was assured of your escape; they were renewed by the decree of accusation which concerns you; they deviate well this atrocity to your courage! But, as soon as I found out that you were in Calvados, I regained my peace of mind. Carry on, my friend, with your generous efforts; Brutus despaired too soon of the salute from Rome to the fields of Philippi; as long as a republican breathes that he has his freedom, that he keeps his energy, he must, he can be useful. The midi offers you, in any case, a refuge; it will be the refuge of good people. It is there, if the dangers accumulate around you, that you must turn your eyes and carry your steps; it's there there that you will have to live, because there you will be able to serve your fellow men and exercise virtues. As for me, I will be able to either wait peacefully for the return of the reign of justice, or suffer the last excesses of tyranny, in a way that my example becomes just as useful. If I have feared something, it is that you have made imprudent attempts in my favor; my friend! It is by saving your country that you can bring my salvation, and I would not want my salvation at the expense of the other; but I would die satisfied knowing that you serve your country effectively. Death, torment, pain, they are nothing to me, I can defy it all; go, I will live until my last hour without wasting a single moment in the confusion of unworthy agitations. […] I spent my first days (in prison) writing a few notes which will one day give pleasure; I put them in good hands and I'll let you know, so that, in any case, they do not remain foreign to you. […] I dare not tell you, and you are the only one in the world who can appreciate it, that I was not very sorry to be arrested. ”They will be less furious, less ardent against R(oland), I said to myself; if they attempt a lawsuit, I will know how to support it in a way that will be useful to his glory; it seemed to me that I thus acquitted myself towards him of a indemnity due to his sorrows; but don't you also see that in finding myself alone it is with you that I remain? Thus, through captivity, I sacrifice myself to my husband, I preserve myself to my friend, and I owe to my executioners to reconcile duty and love: don't pity me! The others admire my courage, but they do not know my pleasures; you, who must feel them, keep them and all their charm by the constancy of your courage. This amiable Goussard! How taken I was to see his sweet face, to feel myself being pressed into his arms, being wet with his tears, and see him pull from his bosom two letters from you! May these details bring some calmness to your heart ! Go! we cannot cease to be reciprocally worthy of the sentiments which we have inspired in each other; we are not unhappy with that. Farewell my friend; my beloved, farewell!

July 3

What sweetness unknown to tyrants, whom the vulgar believe happy in the exercise of their power! And if it is true that a sublime intelligence distributes goods and evils among men according to the laws of rigorous compensation, can I complain of my misfortune, when such delights are reserved for me? I received your letter from the 27th; I still hear your courageous voice, I witness your resolutions, I experience the feelings that animate you, I am honored to love you and to be dear to you. Tell me, do you know sweeter moments than those spent in innocence and the charm of an affection that nature avows and that is regulated by delicacy, which pays homage to the duty of the privations it imposes on it, and nurtures the very strength to bear them? Do you know of any greater advantage than that of being superior to adversity, to death, and to find in your heart what to taste and beautify life to its last breath? Have you ever experienced these effects better than through the attachment that binds us, despite the contradictions of society and the horrors of oppression? I told you, I owe it to said attachment to please me in my captivity. Proud to be persecuted in this time when character and probity are proscribed, I would have borne it, even without you, with dignity; but you make it sweet and dear. The midwayers believe they are overwhelming me by putting me behind bars... Fools! what do I care if I live here or there? Don't I bring my heart everywhere I go, and reassure myself in prison, isn't that giving myself up to it without share? My duties, as soon as I am alone, are limited to vows for all that is just and honest, and what I love still occupies the first rank in this order. Go, I feel too well what is imposed on me in the natural course of things to complain about he violence that overthrew it.[…] I found it delightful to unite the means of being useful to [Roland] with a way of living which left me more to you. I would like to sacrifice my life to him in order to acquire the right to give my last breath to you alone. Except for the terrible agitations which the decrees against the exiles caused me, I never enjoyed greater calm than in this strange situation, and I tasted it without mixing once I learned almost all of them were in safety, since I saw you working in freedom to preserve that of your country. […] May this letter reach you soon, and give you a new testimony of my unalterable sentiments, communicate to you the tranquility that I enjoy, and add to all that you can feel and do that is generous and useful, the inexpressible charm of the affections that tyrants never knew, affections which serve both as trials and as rewards to virtue, affections which give value to life and make it superior to all evils! Greetings to our friends, and especially to the sensitive L(ouvet).

July 6

Yesterday I saw for the second time this excellent V(allée). He gave me your letters from the 30th and first. I didn’t dare to open them in his presence. One does not read a friend’s letter in front of a third party, if only he had known what he was carrying. […] I feel all the generosity of your care , the purity of the wishes, and the more I appreciate them, the more I like my present captivity. […] Four days ago I had this dear picture brought to me, that I, through some sort of superstition, didn't want to put in a prison; but why then refuse this sweet image, beautiful and precious as a revelation of the presence of the object? It is on my heart, hidden from all eyes, felt at all times and often bathed in my tears. Go, I am penetrated by your courage, honored by your attachment and by all that they both can inspire in your proud and sensitive soul. I cannot believe that heaven only reserves sorrows for sentiments so pure and so worthy of its favour. This sort of confidence makes me support life and contemplate death with calmness. Let us enjoy with ignorance the goods which are given to us. Whoever knows how to love as we do carries with him the principle of the greatest and best deeds, the prizes of the most painful sacrifices, the compensation for all ills. Farewell, my beloved, farewell!

July 7

[…] How I adore the bars behind which I’m free to love you without limits and where I can think of you without stop. Here, any other duty is forgotten, I no longer owe myself to anything except to the one who loves me and deserves to be cherished so well. Continue your career with generosity, serve your country, save liberty, each and everyone of your actions is a pleasure for me, and your conduct is my triumph. […] I am interrupted; my faithful maid brings me your letter from the 3rd; you are worried about my silence. […] If fate did not allow us to reunite soon, should we therefore abandon all hope of ever being brought together, and see only the tomb where our elements could be confounded? Metaphysicians and vulgar lovers talk a great deal about perseverance, but it is that of conduct which is rarer and more difficult than that of the affections. Surely, you are not made to lack anything that belongs to a strong and superior soul: do not therefore allow yourself to be carried away by the very excess of courage towards the goal where despair would also lead. You have seen my reasons for not accepting, under these circumstances, a dangerous expedient which does not seem necessary to me; but if the circumstances were to worsen decidedly, I would not persist in refusing a measure that their rigour would justify. It is only a question of calculating calmly, so as not to give to the impetuosity of feeling what it is for prudence to determine.

August 31

Know, my friend, the heart and attachment of your Sophie. You can’t yet imagiene her emotion, her delight at receiving your news. But what incertitudes remains with her, what worries devour her! Why don’t you talk a bit more about your business ventures, so perilous under the circumstances? The modesty of your small properties, the successes you can achieve for yourself are the only benefits she is likely to enjoy in the languor to which she is reduced; she breathes only for the fatherland and will die if you must suffer. I have taken it upon myself to speak to you for her and you cannot hide from yourself the need she has for employing a foreign hand. I will tell you better about her condition. Her sickness has, since your departure, taken a fatal character. […] The state of her family and the idea of your prosperity supported her at that time. I saw you, happy in suffering, preserving her serenity, the freedom of her mind, enjoying the goods she thought reserved for you and looking at herself as a propitiatory victim whose fate perhaps wanted the sacrifice for the price of the advantages assured to those who are dear to him. […] In the strange destiny which unites you so closely to disperse you more cruelly still, enjoy at least, oh my friend! the aspiration to be cherished with the tenderest heart that ever was. What tears I saw poor Sophie shed, kissing your letter and your portrait! Save your days for her; it is not impossible that her age resists the attacks which she bears with such courage; and you owe yourself to her love as long as she exists. She asked me to ask you if you neglected to take your speculations to America? She is convinced that, in spite of the embargo which opposes exports, but which cannot last long, it was with the United States that it was convenient for you to deal. She would like your views to turn in that direction; she was so penetrating with the depth of this disposition, that she is tormented by the suspiciousness which she believes to appear in your letter in this regard. […] Be wiser, my friend, don't think of anything from now on except with these brave republicans, there is no trust and security except with people of this species. Sophie awaits announcement of your resolution in this respect as it was the only means to parry your misfortunes. Farewell, man most beloved by the woman most in love! Farewell! Oh, how you are loved!

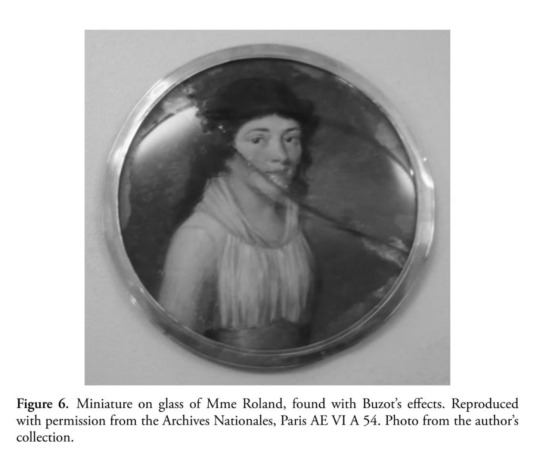

The correspondence appears to end here, despite it being another two months before Manon was executed. Through a letter from October the same year we learn that Manon gave away the portrait of Buzot she talks about in the fourth letter to a friend, telling him to take good care of it — ”it is my dearest property, I could only get rid of it in fear that it would be profaned.”

After the death of Manon we find a letter from Buzot to Jérome le Tellier, where he writes the following:

She is no more, she is no more, my friend! The scroundels have murdered her! Judge if I have anything left to regret on earth! Once you learn of my death, you will burn her letters.

Finally, among Buzot’s effects was found the following portrait depicting Manon (cited on page 260 of Marriage and Revolution: Monsieur and Madame Roland):

As for the relationship between Manon and Barbaroux, I’ve not been able to find any letter between the two. A lot does however point towards such things having existed, but, like in the case of Buzot, been either destroyed or gone missing.

On June 13 1793 Barbaroux wrote to Lauze Duperret: ”Do not forget the estimable citizen Roland, and try to give her some consolation in her prison, by transmitting to her the good news; for that, you could go see Champagneux, head of the offices of the Minister of the Interior.” He followed that up two days later when telling the same person:

You will no doubt still have fulfilled my commission with regard to Madame Roland, by trying to pass on some consolations to her. She must be very unhappy, this estimable wife of the most estimable citizen! Ah! make every effort to see her and tell her that the twenty-two proscribed deputies, all good men, share her pain; may that relieve her! Do you think they have a plan to keep her prisoner? I don’t think so; I believe, on the contrary, that her virtue embarrasses them, and that they would like to see her removed. She should try the proposal to stay only under house arrest. May she soon enjoy her freedom, with our good friends! What a terrible crisis! but also what glory if we save freedom! I give you, enclosed, a letter that we have written to this estimable citizen; I don't need to tell you that you alone can fulfill this important commission: she must, at all costs, try to get out of her prison and find safety.

Duperret did as he was asked, writing to Manon on an unspecified date to tell her that ”I have for several days kept three letters Buzot and Barbaroux had adressed to me to give to you, without it being possible for me to send them to you.”

In another undated letter Manon responded to Duperret:

The news regarding my friends is the only good that affects me; you helped me taste it; tell them that the knowledge of their courage, and of all that they are capable of doing for liberty, consoles me over everything; tell them that my esteem, my attachment and my wishes will follow them everywhere, that the poster (affiche) of B(arbaroux) gave me great pleasure, etc.

All these letters were later used during Manon’s trial to help pass her death sentence.

Manon also shortly mentions Barbaroux in her fourth prison letter to Buzot. Her daughter’s music teacher Anne-Marie-Madeleine Mignot, did in her turn claim during her interrogation ”that [since August 13 1792] she noticed several deputies from the National Convention, such as Brissot, Gensonné, Guadet, Louvet, Barbaroux, Buzot, Pétion, Duperret, Duprat, Chassey, Vergniaux, Condorcet, and others whose names she doesn’t remember, often visited [the Rolands]; that especially Brissot, Buzot, Gorsas, Gensonné and Louvet came there more frequently than the others and had the most direct contact with femme Roland, who often received them in her cabinet.” Barbaroux would in other words have been a frequent visitor to the Rolands, but not the most frequent of them all. This was also confirmed by Manon herself, who during her own interrogation admitted Barbaroux came to visit her and her husband ”from time to time.”

Other than that, we basically only have their memoirs to rely on in regards to their relationship.

Manon’s memoirs:

It was in the course of July that, seeing affairs worsen by the perfidy of the court, the march of the foreign troops and the weakness of the Assembly, we sought a place where the threatened liberty could take refuge. We often talked with Barbaroux and Servan about the excellent spirit of the south, the energy of the departments in this part of France, and the facilities that this place would present for founding a republic there, if the triumphant court were to subjugate the North and Paris. We took maps; we traced the line of demarcation: Servan studied the military positions; they calculated the forces, they examined the nature and the means of transferring the productions: each one recalled the places or the people from whom one could hope for support, and repeated, that after a revolution which had given such great hopes , it was not necessary to fall back into slavery, but to try everything to establish somewhere a free government. “It will be our resource,” said Barbaroux, “if the Marseillais whom I have accompanied here are not sufficiently well supported by the Parisians to reduce the court; I hope, however, that they will come to the end of it and that we will have a Convention which will give the republic for all of France.

Barbaroux, whose features painters would not disdain to take for a head of Antinous, active, industrious, frank and brave, with the vivacity of a young Marseillais, was destined to become a man of merit and a citizen as useful as enlightened . Lover of independence, proud of the revolution, already nourished with knowledge, capable of a long attention span with the habit of applying himself, sensitive to glory; he is one of those subjects which a great politician would like to attach to himself, and which was to flourish with brilliance in a happy republic. But who would dare to foresee to what point premature injustice, proscription, misfortune can compress such a soul and wither its fine qualities! Moderate successes would have sustained Barbaroux in his career, because he loves reputation and has all the faculties necessary to make a very honorable one for himself: but the love of pleasure is next to it; if he once takes the place of glory, through spite of obstacles or disgust at reverses, he will weaken his excellent temper and cause him to betray his noble destination. During Roland's first ministry, I had occasion to see several letters from Barbaroux, addressed rather to the man than to the minister, and whose object was to make him judge the method that should be employed to preserve in the good path of ardent and easily irritated spirits, like those of the Bouches-du-Rhône. Roland, a strict observer of the law, and severe like it, could only speak one language when he was in charge of its execution. The administrators had gone a little astray, the minister had reprimanded them vigorously; they had become embittered: it was then that Barbaroux wrote to Roland to pay homage to the purity of intention of his compatriots, to excuse their errors, and to make Roland feel that a softer mode would bring them back more surely to the necessary subordination. These letters were dictated in the best spirit and with consummate prudence; when I saw their author, I was astonished at his youth. They had the effect which was unmistakable on a just man who wanted the good; Roland relaxed his austerity, took on a more fraternal than administrative tone, brought back the Marseillais and esteemed Barbaroux. We saw him more after leaving the ministry; his open character, his ardent patriotism inspired us with confidence; it was then that, reasoning from the bad state of things and from the fear of despotism for the North, we formed the conditional project of a republic in the South. “It will be our last resort,” said Barbaroux, smiling; but the Marseillais who are here will exempt us from having recourse to it. We judged by this speech and some others like it, that an insurrection was on the horizon; but confidence not extending further, we did not ask more about it. In the last days of July, Barbaroux almost ceased coming to our house, and told us, at the last, that we should not judge his feelings towards us based on the first glimpse of his absence, that his intention with it was to not compromise us. He set out again for Marseilles after the tenth, and returned as a deputy to the Convention. He did his duty there as a man of courage; many of his written speeches show excellent logic and knowledge in the administrative part of commerce; that on subsistence is, after the work of Creuzé-la-Touche, the best of its kind. But he would have to work to become a speaker. Barbaroux, affectionate and lively, became attached to Buzot, sensitive and delicate; I called them Nysus and Euryale: may they have a better fate than these two friends! Louvet, finer than the first, happier than the second, as good as both, became friends with both of them, but more particularly with Buzot, who served as a link to the other, and whose natural gravity made him a bit of a mentor.

Barbaroux’ memoirs:

I went to the interview. Roland lodged in a house in the rue Saint-Jacques, on the third floor; it was a philosopher's retreat. His wife was present at the conversation and participated in it. Elsewhere, I will talk about this amazing woman. Roland asked me what I thought of France and the means of saving her; I opened my heart to him and concealed nothing from him of our first attempts in the South. Precisely, Servan and him had occupied themselves with the same plan. My confidences brought his. He told me that liberty was lost if the plots of the court were not foiled without delay; that La Fayette seemed to meditate on treasons in the North; that the army of the center, completely disorganized , lacking all kinds of ammunition , could not prevent the enemy from making a breakthrough, and that finally everything was arranged for the Austrians to be in Paris in six weeks. Have we then, he added, worked for three years at the finest revolution only to see it overthrown in a day? If liberty dies in France, it is forever lost for the rest of the world: all the hopes of the philosophers are disappointed. The most cruel tyrant will weigh on the earth. Let us prevent this misfortune, let us arm Paris and the departments of the North: or, if they succumb, let us carry to the south the Statue of Liberty, and found somewhere a colony of independent men. He said these words to me, and tears rolled from his eyes. The same feeling made those of his wife and mine flow. Oh! how the outpourings of confidence relieve saddened souls! I quickly gave them an overview of the resources of our departments and our hopes. I saw a sweet joy spread over Roland's brow; he shook my hand, and went to look for a geographical map of France.

Finally, I also found the following footnote in Mémoires inédits de Pétion et mémoires de Buzot et de Barbaroux:

Barbaroux had been the confidant of Madame Roland and of Buzot. I learned this fact from M. Barbaroux, who learned it from his grandmother. We can see, moreover, the confirmation of this tradition in certain passages in the letters from Barbaroux to Madame Roland, which we have published along with the letters to Buzot in our Étude sur madame Roland.

I have no idea regarding the letters from Barbaroux to Manon mentioned here however, I could find none whatsoever inside Étude sur madame Roland.

#girondin drama#Manon care to explain how the hell Euryale is a romantic nickname for your lover???#françois buzot#charles barbaroux#manon roland#ask#frev#buzot#barbaroux#frev friendships

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Francois Boucher (b.1703 - d.1770), ‘La Toilette’, oil on canvas, c.1742, French, currently in the collection of the Museo Nacional Thyssen Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain.

It has been suggested that the model for the principal figure is the artist’s wife Marie-Jeanne Buzot, who posed for some of his paintings. However, portraits of her by the artist, such as the one in the Frick Collection, New York, do not reveal any similarity with the face of the present figure. This, and the fact that the woman is depicted in a rather suggestive form of deshabillé (which would be a somewhat indecorous way for the artist to depict his wife) led Ekserdjian and other authors to reject the idea. Boucher’s scene is a typically voyeuristic one in line with the taste of the time in which the girl reveals her leg in a carefree manner within the context of a normal domestic activity such as getting dressed. - Mar Borobia (x)

#francois boucher#unknown sitter#unknown sitters#known artist#1740s#french#oil on canvas#museo nacional thyssen bornemisza

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

A typical (?) day at the Convention, just in case you wondered what we're dealing with:

Buzot

The order of the day is, I think, to ensure the safety of citizens, the tranquility-... (Interruptions on the left.)

Duhem.

It's not phrases, but bread that the people need! (Applause from the galleries.) -

Buzot

wants to continue. A few members interrupted him again and became agitated.

In fear," he says, "that these troubles will spread elsewhere, I withdraw; but I declare that I do not enjoy my freedom.

Marat

rises to the rostrum. -

Several members: Down with Marat!

Kersaint.

As long as you have such men among you, don't be surprised if the people disrespect you. (Murmurs from the far left. Applause from the center).

Buzot.

I declare, as I come down from the rostrum, that I do not enjoy my freedom and if…

(The clamor of some members interrupts and covers his voice).

The President (Barère)

demands silence and cannot obtain it. The noise continues for over a quarter of an hour.

And it's only November 1792.

(I don't even know what this is about)

Source: https://sul-philologic.stanford.edu/philologic/archparl/navigate/53/3/39/

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Madame Roland and François Buzot :3 Marie-Jeanne 'Manon' Roland de la Platière (1754 –1793), born Marie-Jeanne Phlipon, and best known under the name Madame Roland, was a French revolutionary, salonnière and writer. ‘Manon’ was an intelligent, educated and courageous woman. She supported Girondists. François Buzot was a her good friend.

#french revolution#frev#madame roland#woman in history#french history#la revolution francaise#rococó#pastel art#pastel#girondists#xviii century#history art#history#france

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

More thoughts about Thomas Carlyle…

And his tripped-out take on the French Revolution.

I don’t think any of us here need feel embarrassed about drooling over the dashing young men of the Revolution, given how Carlyle drools over the women. Théroigne, Lamballe, Roland… He goes so far over the top, it’s ridiculous, and some of it patronising as hell. (And he wants to be Thor?!!!)

And as for the rest… This is the root of so much bad historiography and most of the bloody awful fiction about the French Revolution (Dickens, Orczy & c all based their vision of the Revolution on this truly barking book).

Behind the cut, Carlyle being overwrought and over-writing… Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

Maria Teresa Luisa of Savoy-Carignan, Princesse de Lamballe:

Princess de Lamballe has lain down on bed: "Madame, you are to be removed to the Abbaye." "I do not wish to remove; I am well enough here." There is a need-be for removing. She will arrange her dress a little, then; rude voices answer, "You have not far to go." She too is led to the hell-gate; a manifest Queen's-Friend. She shivers back, at the sight of bloody sabres; but there is no return: Onwards! That fair hindhead is cleft with the axe; the neck is severed. That fair body is cut in fragments; with indignities, and obscene horrors of moustachio grands-levres, which human nature would fain find incredible,—which shall be read in the original language only. She was beautiful, she was good, she had known no happiness. Young hearts, generation after generation, will think with themselves: O worthy of worship, thou king-descended, god-descended and poor sister-woman! why was not I there; and some Sword Balmung, or Thor's Hammer in my hand? Her head is fixed on a pike; paraded under the windows of the Temple; that a still more hated, a Marie-Antoinette, may see. One Municipal, in the Temple with the Royal Prisoners at the moment, said, "Look out." Another eagerly whispered, "Do not look." The circuit of the Temple is guarded, in these hours, by a long stretched tricolor riband: terror enters, and the clangour of infinite tumult: hitherto not regicide, though that too may come.

[Except most of this didn’t happen…]

Manon Roland:

Among whom, courting no notice, and yet the notablest of all, what queenlike Figure is this; with her escort of house-friends and Champagneux the Patriot Editor; come abroad with the earliest? Radiant with enthusiasm are those dark eyes, is that strong Minerva-face, looking dignity and earnest joy; joyfullest she where all are joyful. It is Roland de la Platriere's Wife! (Madame Roland, Memoires, i. (Discours Preliminaire, p. 23).) Strict elderly Roland, King's Inspector of Manufactures here; and now likewise, by popular choice, the strictest of our new Lyons Municipals: a man who has gained much, if worth and faculty be gain; but above all things, has gained to wife Phlipon the Paris Engraver's daughter. Reader, mark that queenlike burgher-woman: beautiful, Amazonian-graceful to the eye; more so to the mind. Unconscious of her worth (as all worth is), of her greatness, of her crystal clearness; genuine, the creature of Sincerity and Nature, in an age of Artificiality, Pollution and Cant; there, in her still completeness, in her still invincibility, she, if thou knew it, is the noblest of all living Frenchwomen,—and will be seen, one day. O blessed rather while unseen, even of herself! For the present she gazes, nothing doubting, into this grand theatricality; and thinks her young dreams are to be fulfilled. […]

Noble white Vision, with its high queenly face, its soft proud eyes, long black hair flowing down to the girdle; and as brave a heart as ever beat in woman's bosom! Like a white Grecian Statue, serenely complete, she shines in that black wreck of things;—long memorable. Honour to great Nature who, in Paris City, in the Era of Noble-Sentiment and Pompadourism, can make a Jeanne Phlipon, and nourish her to clear perennial Womanhood, though but on Logics, Encyclopedies, and the Gospel according to Jean-Jacques! Biography will long remember that trait of asking for a pen "to write the strange thoughts that were rising in her." It is as a little light-beam, shedding softness, and a kind of sacredness, over all that preceded: so in her too there was an Unnameable; she too was a Daughter of the Infinite; there were mysteries which Philosophism had not dreamt of!

Anne Théroigne:

But where is the brown-locked, light-behaved, fire-hearted Demoiselle Theroigne? Brown eloquent Beauty; who, with thy winged words and glances, shalt thrill rough bosoms, whole steel battalions, and persuade an Austrian Kaiser,—pike and helm lie provided for thee in due season; and, alas, also strait-waistcoat and long lodging in the Salpetriere! Better hadst thou staid in native Luxemburg, and been the mother of some brave man's children: but it was not thy task, it was not thy lot. […]

One thing we will specify to throw light on many: the aspect under which, seen through the eyes of these Girondin Twelve, or even seen through one's own eyes, the Patriotism of the softer sex presents itself. There are Female Patriots, whom the Girondins call Megaeras, and count to the extent of eight thousand; with serpent-hair, all out of curl; who have changed the distaff for the dagger. They are of 'the Society called Brotherly,' Fraternelle, say Sisterly, which meets under the roof of the Jacobins. 'Two thousand daggers,' or so, have been ordered,—doubtless, for them. They rush to Versailles, to raise more women; but the Versailles women will not rise. (Buzot, Memoires, pp. 69, 84; Meillan, Memoires, pp. 192, 195, 196. See Commission des Douze in Choix des Rapports, xii. 69-131.)

Nay, behold, in National Garden of Tuileries,—Demoiselle Theroigne herself is become as a brownlocked Diana (were that possible) attacked by her own dogs, or she-dogs! The Demoiselle, keeping her carriage, is for Liberty indeed, as she has full well shewn; but then for Liberty with Respectability: whereupon these serpent-haired Extreme She-Patriots now do fasten on her, tatter her, shamefully fustigate her, in their shameful way; almost fling her into the Garden-ponds, had not help intervened. Help, alas, to small purpose. The poor Demoiselle's head and nervous-system, none of the soundest, is so tattered and fluttered that it will never recover; but flutter worse and worse, till it crack; and within year and day we hear of her in madhouse, and straitwaistcoat, which proves permanent!—Such brownlocked Figure did flutter, and inarticulately jabber and gesticulate, little able to speak the obscure meaning it had, through some segment of that Eighteenth Century of Time. She disappears here from the Revolution and Public History, for evermore. (Deux Amis, vii. 77-80; Forster, i. 514; Moore, i. 70. She did not die till 1817; in the Salpetriere, in the most abject state of insanity; see Esquirol, Des Maladies Mentales (Paris, 1838), i. 445-50.)

Max vs Georges:

One conceives easily the deep mutual incompatibility that divided these two: with what terror of feminine hatred the poor seagreen Formula looked at the monstrous colossal Reality, and grew greener to behold him;—the Reality, again, struggling to think no ill of a chief-product of the Revolution; yet feeling at bottom that such chief-product was little other than a chief wind-bag, blown large by Popular air; not a man with the heart of a man, but a poor spasmodic incorruptible pedant, with a logic-formula instead of heart; of Jesuit or Methodist-Parson nature; full of sincere-cant, incorruptibility, of virulence, poltroonery; barren as the east-wind! Two such chief-products are too much for one Revolution.

Supreme Being:

All the world is there, in holydays clothes: (Vilate, Causes Secretes de la Revolution de 9 Thermidor.) foul linen went out with theHebertists; nay Robespierre, for one, would never once countenance that; but went always elegant and frizzled, not without vanity even,—and had his room hung round with seagreen Portraits and Busts. In holyday clothes, we say, are the innumerable Citoyens and Citoyennes: the weather is of the brightest; cheerful expectation lights all countenances. Juryman Vilate gives breakfast to many a Deputy, in his official Apartment, in the Pavillon ci-devant of Flora; rejoices in the bright-looking multitudes, in the brightness of leafy June, in the auspicious Decadi, or New-Sabbath. This day, if it please Heaven, we are to have, on improved Anti-Chaumette principles: a New Religion.

Catholicism being burned out, and Reason-worship guillotined, was there not need of one? Incorruptible Robespierre, not unlike the Ancients, as Legislator of a free people will now also be Priest and Prophet. He has donned his sky-blue coat, made for the occasion; white silk waistcoat broidered with silver, black silk breeches, white stockings, shoe-buckles of gold. He is President of the Convention; he has made the Convention decree, so they name it, decreter the 'Existence of the Supreme Being,' and likewise 'ce principe consolateur of the Immortality of the Soul.' These consolatory principles, the basis of rational Republican Religion, are getting decreed; and here, on this blessed Decadi, by help of Heaven and Painter David, is to be our first act of worship.

See, accordingly, how after Decree passed, and what has been called 'the scraggiest Prophetic Discourse ever uttered by man,'—Mahomet Robespierre, in sky-blue coat and black breeches, frizzled and powdered to perfection, bearing in his hand a bouquet of flowers and wheat-ears, issues proudly from the Convention Hall; Convention following him, yet, as is remarked, with an interval. Amphitheatre has been raised, or at least Monticule or Elevation; hideous Statues of Atheism, Anarchy and such like, thanks to Heaven and Painter David, strike abhorrence into the heart. Unluckily however, our Monticule is too small. On the top of it not half of us can stand; wherefore there arises indecent shoving, nay treasonous irreverent growling. Peace, thou Bourdon de l'Oise; peace, or it may be worse for thee!

The seagreen Pontiff takes a torch, Painter David handing it; mouths some other froth-rant of vocables, which happily one cannot hear; strides resolutely forward, in sight of expectant France; sets his torch to Atheism and Company, which are but made of pasteboard steeped in turpentine. They burn up rapidly; and, from within, there rises 'by machinery' an incombustible Statue of Wisdom, which, by ill hap, getsbesmoked a little; but does stand there visible in as serene attitude as it can.

And then? Why, then, there is other Processioning, scraggy Discoursing, and—this is our Feast of the Etre Supreme; our new Religion, better or worse, is come!—Look at it one moment, O Reader, not two. The Shabbiest page of Human Annals: or is there, that thou wottest of, one shabbier? Mumbo-Jumbo of the African woods to me seems venerable beside this new Deity of Robespierre; for this is a conscious Mumbo-Jumbo, and knows that he is machinery. O seagreen Prophet, unhappiest of windbags blown nigh to bursting, what distracted Chimera among realities are thou growing to! This then, this common pitch-link for artificial fireworks of turpentine and pasteboard; this is the miraculous Aaron's Rod thou wilt stretch over a hag-ridden hell-ridden France, and bid her plagues cease? Vanish, thou and it!—"Avec ton Etre Supreme," said Billaud, "tu commences m'embeter: With thy Etre Supreme thou beginnest to be a bore to me." (See Vilate, Causes Secretes. Vilate's Narrative is very curious; but is not to be taken as true, without sifting; being, at bottom, in spite of its title, not a Narrative but a Pleading.)

Where Assassin’s Creed got some of its idiocy:

One other thing, or rather two other things, we will still mention; and no more: The Blond Perukes; the Tannery at Meudon. Great talk is of these Perruques blondes: O Reader, they are made from the Heads of Guillotined women! The locks of a Duchess, in this way, may come to cover the scalp of a Cordwainer: her blond German Frankism his black Gaelic poll, if it be bald. Or they may be worn affectionately, as relics; rendering one suspect? (Mercier, ii. 134.) Citizens use them, not without mockery; of a rather cannibal sort.

Still deeper into one's heart goes that Tannery at Meudon; not mentioned among the other miracles of tanning! 'At Meudon,' says Montgaillard with considerable calmness, 'there was a Tannery of Human Skins; such of the Guillotined as seemed worth flaying: of which perfectly good wash-leather was made:' for breeches, and other uses. The skin of the men, he remarks, was superior in toughness (consistance) and quality to shamoy; that of women was good for almost nothing, being so soft in texture! (Montgaillard, iv. 290.)—History looking back over Cannibalism, through Purchas's Pilgrims and all early and late Records, will perhaps find no terrestrial Cannibalism of a sort on the whole so detestable. It is a manufactured, soft-feeling, quietly elegant sort; a sort perfide! Alas then, is man's civilisation only a wrappage, through which the savage nature of him can still burst, infernal as ever? Nature still makes him; and has an Infernal in her as well as a Celestial.

#thomas carlyle#french revolution#fanboying#manon roland#princesse de lamballe#georges-jacques danton#maximilien robespierre#wtf?!#historiography#historical mythmaking

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

C’est aujourd’hui que les peres conscrits, qui ont vendu la nation au monarque, et qui ont perdu la France, cessent leurs redoutables fonctions, pour rentrer dans la foule. Ils sont arrivés au sénat couverts de gloire, ils en sortent couverts d’infâmie. Puisse l’indignation publique leur faire enfin subir la peine qu’aurait dû depuis long-tems leur infliger le glaive de la justice.

Au sein de l’opulence, prix de leurs lâches machinations, puissent-ils traîner le reste de leurs jours dans les remords et l’opprobre !

A côté de tant d’hyppocrites, de fourbes et de vils scélérats qui ont trahi la patrie, siégeaient pour l’honneur de l’humanité quelques hommes intègres qui n’ont jamais cessé de la défendre. O Roberspierre, Péthion, Prieur, Grégoire Buzot, puissiez-vous recevoir en ce jour, de la main des amis de la liberté, la couronne de gloire que la nation doit à ses défenseurs incorruptibles !

L’Ami du peuple du 30 septembre 1791, n° 562, p. 8.

#il y a 226 ans#Révolution française#comme d'habitude j'ai respecté l'orthographe originale#je ne sais pas trop pourquoi Marat n'arrive toujours pas à écrire Robespierre mais c'est ainsi#Prieur de la Marne#30 septembre 1791#Robespierre#Marat#Pétion#Grégoire#Buzot#Assemblée constituante#1791#Pierre-Louis Prieur#Maximilien Robespierre#Jean-Paul Marat#L'Ami du peuple

3 notes

·

View notes