#jacques-pierre brissot

Text

Some primary sources

I plan to add more whenever I find more.

Historie Parlamentaire de la Révolution Française ou Journal des Assemblées Nationales, depuis 1789 jusqu’en 1815

Volume 1 (May 1789)

Volume 2 (June-September 1789)

Volume 3 (September-December 1789)

Volume 4 (December 1789-March 1790)

Volume 5 (March-May 1790)

Volume 6 (May-August 1790)

Volume 7?

Volume 8 (November 1790-February 1791)

Volume 9 (February-May 1791)

Volume 10 (May-July 1791)

Volume 11 (July-September 1791)

Volume 12 (September-December 1791)

Volume 13 (January-March 1792)

Volume 14 (April-June 1792)

Volume 15 (June-July 1792)

Volume 16 (July-August 1792)

Volume 17 (August-September 1792)

Volume 18 (September 1792)

Volume 19 (September-October 1792)

Volume 20 (October-November 1792)

Volume 21 (November-December 1792)

Volume 22 (December 1792-January 1793)

Volume 23 (January 1793)

Volume 24 (February-March 1793)

Volume 25 (March-April 1793)

Volume 26 (April-May 1793)

Volume 27 (May 1793)

Volume 28 (July-August 1793)

Volume 29 (September-October 1793)

Volume 30 (October-December 1793)

Volume 31 (November 1793-March 1794)

Volume 32 (March-May 1794)

Volume 33 (May-July 1794)

Volume 34 (July-August 1794)

Recueil des actes du comité de salut public

Volume 1 (August 12 1792-January 21 1793)

Volume 2 (January 22-March 31 1793)

Volume 3 (April 1-May 5 1793)

Volume 4 (6 May-18 June 1793)

Volume 5 (19 June-15 August 1793)

Volume 6 (15 August-21 September 1793)

Volume 7 (22 September-24 October 1793)

Volume 8 (25 October-26 November 1793)

Volume 9 (27 November-31 December 1793)

Volume 10 (1 January-8 February 1794)

Volume 11 (9 February-15 March 1794)

Volume 12 (16 March-22 April 1794)

Volume 13 (23 April-28 May 1794)

Volume 14 (29 May-7 July 1794)

Volume 15 (8 July-9 August 1794)

Recueil de documents pour l’histoire du club des Jacobins de Paris

Volume 1 (1789-1790)

Volume 2 (January-July 1791)

Volume 3 (July 1791-June 1792)

Volume 4 (June 1792-January 1793)

Volume 5 (January 1793-March 1794)

Volume 6 (March-November 1794)

Histoire du tribunal révolutionnaire de Paris: avec le journal de ses actes.

Volume 1

Volume 2

Volume 3

Volume 4

Volume 5

Papiers inédits trouvés chez Robespierre, Saint-Just, Payan etc

Volume 1

Volume 2

Volume 3

Oeuvres complètes de Robespierre

Volume 1 (Robespierre à Arras)

Volume 2 (Les œuvres judiciaires)

Volume 3 is the correspondence, listed below

Volume 4 (Le defenseur de la Constitution)

Volume 5 (lettres à ses comettras)

Volume 6 (speeches 1789-1790)

Volume 7 (speeches January-September 1791)

Volume 8 (speeches October 1791-September 1792)

Volume 9 (speeches September 1792-June 27 1793)

Volume 10 (speeches June 27 1793-July 27 1794)

Oeuvres de Maximilien Robespierre (not the same as Oeuvres completés)

Volume 1

Volume 2

Volume 3

Oeuvres de Jerome Pétion

Volume 1

Volume 2

Volume 3

Volume 4

Oeuvres complètes de Saint-Just

Volume 1

Volume 2

Oeuvres littéraires de Hérault de Séchelles (1907)

Oeuvres de Danton (1866)

Discours de Danton (1910) by André Fribourg

Works by Desmoulins

La France Libre (1789)

Discours de la Lanterne aux Parisiens (1789)

Révolutions de France et de Brabant (1789-1791)

Volume 1 (number 1-13)

Volume 2 (number 14-26)

Volume 3 (number 27-39)

Volume 4 (number 40-52)

Volume 5 (number 53-65)

Volume 6 (number 66-79)

Volume 7 (number 80-86)

La Tribune des Patriots (1792) (all numbers)

Le Vieux Cordelier (1793-1794) (all numbers)

Jean Pierre Brissot démasqué (1792)

Histoire des Brissotins (1793)

Correspondences

Correspondance de Maximilien et Augustin Robespierre (1926)

Correspondance de George Couthon (1872)

Correspondance inédit de Camille Desmoulins (1836)

Correspondance inédite de Marie-Antoinette (1864)

Billuad-Varennes — mémoires et correspondance

Correspondance de Brissot

Lettres de Louis XVI: correspondance inédite, discours, maximes, pensées, observations etc (1862)

Lettres de Madame Roland (1900)

Volume 1

Volume 2

Correspondance inédite de Mlle Théophile Fernig (1873)

Journal d’une bourgeoise pendant la Révolution 1791-1793 by Rosalie Jullien (1881)

Memoirs

Memoirs of Bertrand Barère

Volume 1

Volume 2

Volume 3

Volume 4

Memoirs of Élisabeth Lebas

In French

In English

Mémoires de Charlotte Robespierre sur ses deux frères (1835)

In French

In English

Memoirs of Joseph Fouché

Volume 1 (English)

Volume 2 (French)

Mémoires de Brissot (1877)

Mémoires inédits de Pétion et mémoires de Buzot et Barbaroux (1866)

Memoirs of Barras — member of the Directorate (1899)

Mémoires inédits de madame la comtesse de Genlis depuis 1756 jusqu’au nos jours

Volume 1

Volume 2

Volume 3

Volume 4

Volume 5

Volume 6

Volume 7

Volume 8

Volume 9

Volume 10

Mémoires de Madame Roland

Volume 1

Volume 2

Mémoires de Louvet (1862)

Memoirs of the Duchess de Tourzel: Governess to the Children of France During the Years 1789, 1790, 1791, 1792, 1793 and 1795

Volume 1

Volume 2

Révélations puisées dans les cartons des comités de salut public et de sûreté générale, ou Mémoires (inédits) de Sénart, agent du gouvernement révolutionnaire (1824)

Free books

Danton (1978) by Norman Hampson (borrowable for an hour, renewable every hour)

Robespierre (2014) by Hervé Leuwers (borrowable for an hour, renewable every hour)

Collot d’Herbois — légendes noires et Révolution (1995) by Michel Biard

Choosing Terror (2014) by Marisa Linton

The Coming of the Terror in the French Revolution (2015) by Timothy Tackett

Augustin: the younger Robespierre by (2011) by Mary-Young

Journaliste, sans-culotte et thermidorien: le fils de Fréron, 1754-1802, d’après des documents inédits (1909) by Raoul Arnaud

Un Champion de la Royauté au début de la Révolution - François Louis Suleau (1907)

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Camille Desmoulins and his wife — passages from the history of the dantonists (1876) by Jules Claretie

Vadier, président du Comité de sûreté générale sous la Terreur d’après des documents inédits (1896) by Albert Tournier

Mémoires historiques et militaires sur Carnot (1824)

Le Puy-de-Dôme en 1793 et le Proconsulat de Couthon (1877) by Francisque Mège

Le procès des Dantonistes, d'après les documents, précédé d'une introduction historique. Recherches pour servir à l'histoire de la révolution française (1879) edited by Dr. Jean François Eugène Robinet

Robert Lindet, député à l'Assemblée législative et à la Convention, membre du Comité de salut public, ministre des finances : notice biographique (1899) by Amand Montier

Prieur de la Côte-d'Or (1900) by Paul Gaffarel

Un épicurien sous la Terreur; Hérault de Séchelles (1759-1794); d'après des documents inédits (1907) by Emile Dard

Twelve Who Ruled (1941) by R. R. Palmer (borrowable for an hour, renewable every hour)

Bertrand Barère: A Reluctant Terrorist (1963) by Leo Gershoy (borrowable for an hour, renewable every hour)

Saint-Just : sa politique et ses missions (1976) by Jean-Pierre Gross (borrowable for an hour, renewable every hour)

The Glided Youth of Thermidor (1993) by François Gendron

Pauline Léon, une républicaine révolutionnaire by Claude Guillon

Billaud-Varenne: Géant de la Révolution (1989) by Arthur Conte

When the King Took Flight (2003) by Timothy Tackett (borrowable for an hour, renewable every hour)

Joseph Le Bon, 1765-1795; la terreur à la frontière (1932) by Louis Jacob

Volume 1

Volume 2

Resources shared by other tumblr users (thank you all very much!!!)

Resources shared by @iadorepigeons

Resources shared by @georgesdamnton

Resources shared by @rbzpr:

Fabre d’Eglantine resources shared by @edgysaintjust

Saint-Just resources shared by @sieclesetcieux

Saint-Just resources shared by @orpheusmori

Marat resources shared by @orpheusmori

My own translations

Lucile Desmoulins’ diary (1788, 1789, 1790, 1792-1793)

Charlotte Robespierre et ses amis (1961)

Laponneraye on the life of Charlotte Robespierre (1835)

Abbé Proyart on the childhood of Robespierre (1795)

Regulations for the internal exercises of the College of Louis-le-Grand (1769)

Regulations for law students at Louis-le-Grand (1782)

Belongings left by Danton, Fabre and Desmoulins after their arrest

Letters from Robespierre’s father

Robespierre family timeline

#frev resources#frev#french revolution#maximilen robespierre#augustin robespierre#robespierre#george couthon#couthon#camille desmoulins#desmoulins#joseph fouché#fouché#charlotte robespierre#elisabeth lebas#elisabeth duplay#billaud-varennes#jerome Pétion#jacques-pierre brissot#saint-just

456 notes

·

View notes

Text

does anyone know of any trustworthy biographies of Brissot? either French or English is fine.

#personal#i'm still undecided on whether or not I want to include him but. also I've taken a liking to that little bastard (affectionate)#frev#brissot#jacques-pierre brissot#french revolution#what uh. other tags do people use here. um.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

also a brissot head and a robi head

i am confused

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey everyone its kes formerly @/rosenaya ^.^ it's been about a year since i deleted tumblr and i'm back now! hopefully for good but we shall see!

#yes my url is in ref to jacques-pierre brissot no i am not a girondin hashtag montagnards 5ever#just wanted a one-word frev related url :3 and i DO respect some things he did!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brissot posting

#french revolution#frev#frev community#history#jacques pierre brissot#maximilien robespierre#georges danton#george washington#that one time brissot met up with washington and asked him to free his slaves#he was so real for that#lazy art

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

He [Jacques Pierre Brissot de Warville] Will explain to You What Has Been done in this Country Respecting the Negroe trade, and slavery. I don’t Know wether You Had me Enlisted in the Societies at Newyork and Elsewhere; if Not, I Beg You Will do it—I am Making an Experiment at Cayenne on a plantation I Have purchased on purpose.

The Marquis de La Fayette to Alexander Hamilton, May 24, 1788

“To Alexander Hamilton from Marquis de Lafayette, 24 May 1788,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-04-02-0239. [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 4, January 1787 – May 1788, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1962, pp. 652–654.] (01/13/2024)

#quotes#letter#1788#founders online#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#american history#french revolution#alexander hamilton#jacques pierre brissot de warville#slavery

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry to do this but ... Can I has some William Wordsworth trivia next? 👀

He was my favourite poet back when I was a kid and somehow he remains the same now so I'd also love any little rabbit holes you could point me towards to get lost in

Don't apologise I am having the time of my life with all these asks

Wordsworth trivia:

The thing with Brissot. I've talked about it on here before but basically, when Wordsworth was young he went to revolutionary France, originally for a walking tour of the alps, but he eventually ended up in Paris. While there he visited the National Convention, etc etc, and also met *a guy* who he alludes to in The Prelude and who was pretty obviously meant to be Jacques Pierre Brissot, the Girondin leader during the French Revolution. According to Wordsworth they were buddies and he slept in Brissot's house several times. Seems pretty clear cut, however later on, when he had morphed into Older Tory Wordsworth he pretty much... denied that this happened? like he said that he didn't actually meet Brissot, that it was a lie, because of course Older Tory Wordsworth who was the Poet Laureate couldn't be known to have fraternized with the Girondins if he wanted to keep his reputation. Which is a super weird thing to claim, and it means that he lied at some point but it's not really immediately obvious when. Personally I think that he did meet Brissot and that Older Tory Wordsworth told the lie but idk

He loved his children so much and was so absolutely gutted when his daughter Dora died that he planted a huge field of daffodils (of course) for her, and it still exists today!

I have two long posts about two insane stories with him and Coleridge which I'll link for you: the one where he maybe slept with Sara Hutchison, and the one about their epic breakup

Annette Vallon! She was a woman who he met in revolutionary France, who he fell in love with and planned to marry until circumstances of the revolution and Napoleon stopped that from ever happening. He also had a kid by her, a girl named Caroline, who he came over and met as soon as the borders were open again. The sonnet "It is a Beauteous Evening, Calm and Free" is about a seaside walk with her in 1802

I was literally just about to start writing a post about the Spy Nozy incident, but basically what happened was that a combination of being friends with Coleridge + knowing John Thewall (a radical writer and, randomly enough, a pioneer in speech therapy) made the government very very suspicious of Wordsworth, so they tried to spy on him, which kind of just turned into a trainwreck on all sides with the spy being really bad at his job and Coleridge accidentally making him think they were on to him. Also the Home Secretary was personally involved? for some reason? it was just incredibly wild all around but I'll go more into it in a full post about it

#william wordsworth#wordsworth#jacques pierre brissot#brissot#annette vallon#caroline vallon#samuel taylor coleridge#coleridge#romanticism#romantic poets#asks

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

soviet-flavoured jokes, but they are about the frev

i thank @citizen-card for making me very creative this evening, hopefully not too creative as to forget virtue altogether.

i have written 11 jokes. here they are:

at dusk, a working-class couple, being marat's neighbours, offered to arrange for the journalist to stay in their underground room, while national guards, under the command of lafayette, were likely to come to hunt down marat during the night.

upon descending to the basement, marat was saluted by the couple's child, a very young girl, armed with a pike twice her height. the child insisted that she would stay with marat in the underground, and would fight any guard who dared to break in.

"young citoyenne, your zeal is admirable, but your must calculate your moves," said marat, "it would be wiser if your parents were the ones who put up a fight against lafayette; as for you, your main task is to survive, and to grow up under the sun."

"i will certainly grow up under the sun," answered the child, who seemed rather excited, "but how do i prove that i have met the hero of the two worlds, if he dares not fight maman and papa in the world above the ground, and simultaneously, myself in the underworld?"

charette and carrier, two very fierce men, offered to teach the ways to cook eggs to robespierre, who had no experience in cooking.

charette demonstrated how to break many eggs, while promising that he would eventually make an omelette.

carrier threw eggs into deep water wells in the hope that the sun could, with enough time, boil the water in the wells, eventually giving him poached eggs.

the hen who laid the eggs came walking to robespierre, saying that charette had promised to take care of her retirement, and carrier, the education of her children.

chaumette, a very sexist man, criticised brissot for letting his wife translate works by english writers into french.

"but what are you complaining about? you want all women to stay in the kitchen," said brissot in defense, "and my beloved félicité does all her writings in our kitchen, for she produces food for the mind."

"i do not doubt that she does," replied chaumette, "but your félicité may have translated a book written by mary wollstonecraft, who, in turn, may not have been writing in the kitchen exclusively, and this mary wollstonecraft has no husband who would testify on that fact for her."

"what is jean-lambert tallien's greatest achievement?"

"living to be 27."

"and his second greatest achievement?"

"giving the prince of chimay a worthy wife."

brissot, co-founder of the society of the friends of the blacks, came across a haitian man in the street.

"sir, are you currently a violent rebel?" asked brissot.

the haitian, who did not know that he was talking to brissot, replied politely in the negative.

"have you ever been a violent rebel in the past, then, sir?" the deputy continued to ask.

"not that i know of," said the haitian, "but why do you call me 'sir'? i thought the people of the metropole go by the title 'citizen'."

"do you know, then, sir," came yet another question, "or know of, any of your fellow men, who are, or have been at any time in the past, violent rebels?"

"of all my fellow man, one jacques-pierre brissot does stand out, and i have heard that this brissot is not afraid to make enemies with all prussians and austrians, throwing away the livelihoods of many of his own countrymen if need be."

"ah, " concluded brissot, "so you are aware of the concept of violent rebellion after all. well, sir, we in the society of the friends of the blacks will have nothing to do with you; you see, we only befriend the blacks who are willing to make the first step and befriend us back."

danton said to robespierre that virtue was what he (danton) did with his wife when they were alone at night.

"really?" said robespierre, and he was pleasantly surprised, "even saint-just would not co-write my speeches and reports with me, but the citoyenne danton would do so with you? o, that is virtue indeed."

hérault, a well-versed writer before he was a conventionnel, wanted to decree in the 1793 constitution that men should not be accused in court by people using the evidence of any and all texts that they wrote before the age of 40, since younger men were closer to nature, and freedom of press was in the Declaration.

"are you trying to make us all avoid accountability," said couthon, a colleague known for being a polite contrarian, "as i am the eldest of the five people in charge of writing this constitution, and i am only 36?"

"no," answered hérault, "i just wish to see the now 39-year-old brissot tried and brought to justice, for the grave crime of attempting to flee from his patrie while the patrie is at a war that he has started, and for the graver crime of being a boring husband; i shall do all good citizens a favour simply by sparing anyone from paying more attention to brissot's writings."

lazare carnot, a mathematician who sat with the plain, was tasked by jeanbon saint-andré, the naval officer, to calculate the number of teardrops that should drown an average english fleet.

carnot took on this calculation himself, secluded himself in his study, ignored signs of affection from his close colleague claude-antoine prieur, avoided meetings for days on end, nonchalantly signed several decrees whose objectives he made no records of in writing or in mind, for a mist would not clear before his eyes, and concluded finally that he had enough teardrops in him alone, to drown not just a few fleets, but the entirety of england.

an illiterate man asked a man who could read about the difference between desmoulins and marat, both prominent journalists.

"that is not a difficult task," answered the literate man, "one is a friend of robespierre the elder, and therefore constantly defended by him; the other has barely talked to robespierre, but would often risk himself in defending him."

the robespierre siblings all announced to each other that they were getting married, and all their spouses-to-be wished to live with them. unfortunately, a revolutionary and a counter-revolutionary and a military dictator were not considered perfect in-laws of each other, so the weddings were all called off.

during the empire, philippe buonarroti, who was a jacobin and then one of the égaux, went into exile in geneva, and sustained his own livelihood by teaching music.

one day, one of buonarroti's youngest tutees came up to him, asking him about the difference between the roles of the left hand and of the right hand in playing the piano.

"my child, the left is indispensable, and does much work to set the pace and the progression," answered his tutor, "and the right is louder and more memorable to most laymen, and therefore easily parroted."

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jacques-Pierre Brissot

Jacques-Pierre Brissot de Warville (1754-1793) was a French journalist, abolitionist, and politician who played a prominent role in the French Revolution (1789-1799). A leader of the Girondins, a moderate political faction, Brissot was instrumental in embroiling France in the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802). He was also known for founding the Amis des Noirs, a French abolitionist society.

The son of an innkeeper, Brissot rose to prominence during the Revolution with his newspaper Le Patriote Français and won election to the Legislative Assembly in 1791. At a time when the Revolution appeared to be over, he did more than any other single individual in leading France into war with the rest of Europe, believing that France could solidify its revolutionary gains only through military conquest. He became the figurehead of the moderate Girondins, working with them to spare the life of King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) and to decentralize power from Paris; both projects ultimately failed. After the insurrection of 2 June 1793 led to the fall of the Girondins, Brissot was arrested. He was executed alongside 20 of his colleagues on 31 October 1793, victims of the Reign of Terror.

Continue reading...

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

12 notes

·

View notes

Quote

You are right, I see Brissot, however rarely; but you don't know him, and I know him from childhood.

Discours de Jérôme Pétion sur l’accusation intentée contre Maximilien Robespierre (1793)

Just me who missed Pétion and Brissot were childhood friends too?

#childhood friends from chartres vs childhood friends from louis-le-grand#who will win?#spoilers it’s desmoulins and robrespierre#but they also get minus points for splitting the team before pétion was entirely finished off#pétion#jérôme pétion#jacques-pierre brissot#brissot#robespierre#desmoulins

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

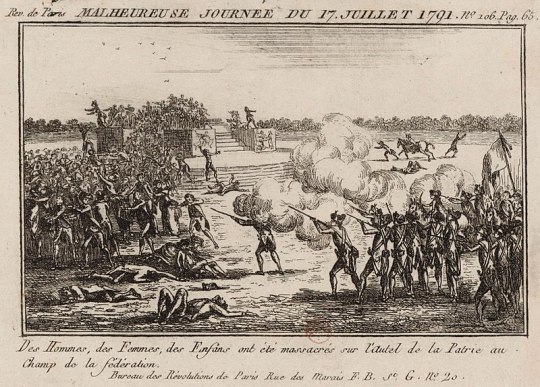

1791-Champ de Mars massacre

Members of the French National Guard under the command of General Lafayette open fire on a crowd of radical Jacobins at the Champ de Mars, Paris, during the French Revolution, killing scores of people.

The Champ de Mars massacre took place on 17 July 1791 in Paris at the Champ de Mars against a crowd of republican protesters amid the French Revolution. Two days before, the National Constituent Assembly issued a decree that King Louis XVI would retain his throne under a constitutional monarchy. This decision came after Louis and his family had unsuccessfully tried to flee France in the Flight to Varennes the month before. Later that day, leaders of the republicans in France rallied against this decision.

Jacques Pierre Brissot was the editor and main writer of Le Patriote français and president of the Comité des Recherches of Paris, and he drew up a petition demanding the removal of the king. A crowd of 50,000 people gathered at the Champ de Mars on 17 July to sign the petition,[1] and about 6,000 signed it. However, two suspicious people had been found hiding at the Champ de Mars earlier that day, "possibly with the intention of getting a better view of the ladies' ankles"; they were hanged by those who found them, and Paris Mayor Jean Sylvain Bailly used this incident to declare martial law.[2][page needed] Lafayette and the National Guard under his command were able to disperse that crowd.

Georges Danton and Camille Desmoulins had led the crowd, and they returned in even higher numbers that afternoon. The larger crowd was also more determined than the first, and Lafayette again tried to disperse it. In retaliation, they threw stones at the National Guard. After firing unsuccessful warning shots, the National Guard opened fire directly on the crowd. The exact numbers of dead and wounded are unknown; estimates range from a dozen to 50 dead.

Lafayette, the commander of the National Guard, was previously long revered as the hero of the American Revolutionary War. Many French looked up to Lafayette with hope, expecting him also to lead the French Revolution in the right direction. One year before, on the very same Champ de Mars, he played a prominent ceremonial role during the first Fête de la Fédération (14 July 1790), in memory of the 1789 Storming of the Bastille. However, Lafayette's reputation among the French never recovered from this bloody episode. The people no longer looked towards him as an ally or supported him after he and his men fired deadly shots into the crowd. His influence in Paris diminished accordingly.[4][page needed] He would still command French armies from April to August 1792, but then fled to the Austrian Netherlands where he was taken prisoner.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

My guilty pleasure is drawing pissed off Robespierre.

Also a clueless Brissot

Fight! Fight! Fight! Baiser

#Maximilien Robespierre#brissot#robespierre#Jacques Pierre brissot#french revolution#frev#art#my art

223 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jacques-Pierre Brissot

Jacques-Pierre Brissot de Warville (1754-1793) était un journaliste, abolitionniste et homme politique français qui joua un rôle de premier plan dans la Révolution française (1789-1799). Chef de file des Girondins, une faction politique modérée, Brissot contribua à impliquer la France dans les guerres révolutionnaires françaises (1792-1802). Il est également connu pour avoir fondé les Amis des Noirs, une société abolitionniste française.

Lire la suite...

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pierre Fresnay in La Main du Diable (Maurice Tourneur, 1943)

Cast: Pierre Fresnay, Josseline Gaël, Noël Roquevert, Guillaume de Sax, Palau, Pierre Larquey, André Gabriello, Antoine Balpêtré, Marcelle Rexiane, André Varennes, Georges Chamarat, Jean Davy, Jean Despreaux, André Bacqué, Gabrielle Fontan. Screenplay: Jean-Paul Le Chanois, based on a novel by Gérard de Nerval. Cinematography: Armand Thirard. Production design: Andrej Andrejew, Film editing: Christian Gaudin. Music: Roger Dumas

Maurice Tourneur's son, Jacques Tourneur, is better-known in the United States today because of his work for producer Val Lewton on arty horror films like Cat People (1942) and I Walked With a Zombie (1943), as well as the quintessential film noir Out of the Past (1947). Maurice had been a mainstay Hollywood director in the silent era -- director Clarence Brown named him as one of his mentors -- but grew impatient with studio interference and returned to France just as sound was coming in. As a result, La Main du Diable (released in the States as Carnival of Sinners) is probably his best-known film on this side of the Atlantic. It shares with his son's films a stylish approach to horror filmmaking, in which creating a mood takes precedence over shocking the audience. Based on a story by Gérard de Nerval, La Main du Diable is about a struggling artist, Roland Brissot (Pierre Fresnay), who buys a talisman, a severed hand in a casket, from a chef, paying only a penny for it. The chef claims that it has made him a success, but that it must be sold again, at less than the price Brissot paid him for it, before the artist dies. Otherwise his soul will be lost forever. Brissot's career takes off, making him rich, and he marries his model, Irène (Josseline Gaël), who had hitherto spurned him. But he soon finds that he's being stalked by a little man in black (Palau), the devil himself, who makes it clear that the talisman is the real thing and offers to buy it back from Brissot, who is unable to sell it because there's no coin smaller than the penny he had paid. The artist, enjoying his celebrity and wealth, turns him down, but is then informed that since the buyback offer has been made, the price will double each day. Soon the price has mounted into the millions and Brissot begins to panic, looking for a way to get rid of the hand. He then learns the lineage of the hand, which began several centuries ago with a deal made by a monk named Maximus Léo (André Bacqué) -- which is also the name Brissot, under the spell of the hand, has been signing to his paintings. If Brissot can reunite the hand with the monk's body, then the deal can be broken. All of this is told in flashback to a crowd at the inn in the French Alps to which Brissot has traveled, the little man in black pursuing him, trying to find the tomb of Maximus Léo. There's not really much horror on display in La Main du Diable, but the film is full of striking visuals, the work of production designer Andrej Andrejew and cinematographer Armand Thirard, and Tourneur directs a capable and colorful cast headed by Pierre Fresnay as Brissot. Since the film was made in occupied France, there are those who think it's a subversive allegory about the price exacted from the French in capitulating to the Nazis.

3 notes

·

View notes