#labtekwon

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Link

a soundtrack-mix I created to celebrate and acknowledge Black History Month.

#black history month#blm#black lives matter#mary lou williams#angel bat davvid#alvin ailey american dance theater#jlin#billie holiday#pearl bailey#dj /rupture#underground resistance#sun ra#lujadu sisters#mulatu astatke#labtekwon#nicolette#esg#nina simone#fifth dimension

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Progenitor and The Eternal Recurrence/ a portrait of the artist and the father

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

HipHopPhilosophy.com Radio - 06-08-20 - Monday Night Fresh

#a.c.theprogramdirector#acatcalledfritz#acthepd#dirtyartclub#dooleyo#elchoppo#ensilence#fredespi#funk#hiphop#hiphopphilosophy#jazzyhiphop#jessthefacts#labtekwon#meccanizm#oldirtybastard#organizedkonfusion#peoplewithoutshoes#soulhiphop#undergroundhiphop

1 note

·

View note

Text

#music#hip hop#alternative hip hop#comedy#lol#malkovich music#homeboy sandman#ras g#eagle nebula#labtekwon

0 notes

Video

youtube

Labtekwon - Black Skatepunk

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

PEACE

#DMV hip hop#DMV Rappers#washington dc#southeast dc#Labtekwon#black people#afrolatina#afro lady#afro#natural hair#sisterlocks#Black Kids#black children#black history month#rastafarian#moorish science temple#noble drew ali#Father Allah#nation of gods and earths#5% Nation of islam#5% Nation of Gods and Earths#allah's five percent#Philly Hip Hop#Philly Rappers#The Roots

5 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Labtekwon - No Time To Chill

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Manual of Exorcism: ELUCID’s I Told Bessie

I used to watch my grandmother catch the Holy Ghost in church— for her soul she would search.

—Pharaohe Monch, “Black Sunday” (1994)

The weight of the world is heavy on my mind.

—Guru, “Who’s Gonna Take the Weight?” (1990)

I am challenged to speak, to bring my all to that altar of continued black liberation struggle…

—bell hooks, Yearning

Arise! Spirit of the true and living God!

—Labtekwon, “Séance” (1998)

DOCUMENT i 1.

The first voice we hear on I Told Bessie is that of Joy James, and she asks, What’s the exit plan? When Black people sense stability, she explains, white people orchestrate another form of theft. In a special 1976 episode of Bill Moyers Journal titled “Rosedale: The Way It Is,” a Black family, the Spencers, have an exit plan. The Spencers move into a home in the Rosedale neighborhood of Queens. They’re met by the white community with chants of “Nxggxrs go to hell,” an arson attack, and a pipe-bomb explosion on their front porch. In one scene, after activists from South Jamaica arrive to show support for the Spencers, a counter-protest of Rosedale residents materializes. In their fury, a mob of white children shouting “white power” accost and assault a few Black girls on bikes. In an interview with the Black girls immediately following the incident, one tells the camera crew, through tears, “I hate their goddamn guts!” One of the older girls, still straddling her bike, gently says, “I can’t say that I hate them…it’s just the system.”

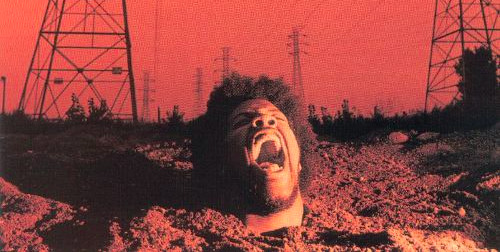

The music video for ELUCID’s “Spellling” (directed by Nelson Bandela) presents a sort of reciprocal to this historic scene. ELUCID rides his bike in circles, in figure-8s—an unknown infinite in an empty city park, unmolested and unfettered. The teal frame of his bike matches the “opal in [his] teeth,” and the wheels spin like two ensōs inkily and egolessly applied to washi paper. On the track intro, ELUCID’s voice is interspliced with Joy James’s. They have made this star unsafe, he says, reciting lines from Amiri Baraka’s “Jitterbugs.” And this age, primitive, though yr mind / is somewhere else, your ass ain’t. Wherever you go, there you are type-shit. “The imperfection of the world / is a burden,” Baraka preached. ELUCID must feel it; he screams as release—not quite a Woo-Hah!!, though he appears to have got himself in check; not exactly the satirical screams De La do at the start of “Ego Trippin’ (Part Two)”; not the scream of ecstasy we hear before Mase delivers the first bars of “Feel So Good.” But a primal scream—followed by a cackle. “To keep from crying / I opens ma mouth an’ laughs,” Langston Hughes explains on “Homesick Blues.”

2.

Those opening hard-r’s: (a)part / heart / arc / park / start / dark / mark / are / starved: meaningful in their harshness, hard-r’s always are. Though I Told Bessie, at turns, soothes like a salve, it can also be harsh art. Like Aesop Rock (who hard-rs just the same), ELUCID utilizes a “jabberwocky superfly,” though with more of a socio-political valence than Bavitz ever musters. ELUCID cleanses the space and “palo scent[s] the heart.” Never mind the long arc of the moral universe bending toward justice—he’s focused on “following [his] arc,” first and foremost. He’s a dancer in the dark—more Björk with her back to birch bark than Fred Astaire. Don’t be disoriented by the steps; he’s “running tangents off the mark.” Don’t follow the leader as Rakim implored: “Follow me into a solo—get in the flow.” What could you say as the earth gets further and further away? (That’s that aforementioned “wet earth,” no doubt.) Watch your footwork, and listen: “If you’re seeking understanding, you should jam this where you are”—not where you were, or where you plan to be, but where you are. Here. Here. Draw plans for today, not tomorrow. Presence. (’Cause on the mic, ELUCID’s got more presence than….)

3.

I’m carrying…

ELUCID carries the weight of the whole world in his hands: hear how he draws out the word (caaaarrryin’) to help us feel its heft. He’s carrying the “needings and wantings,” the “secrets and hauntings,” all the amassed “seasons of harvest.” He which soweth bountifully shall reap also bountifully (2 Corinthians 9:6 KJV). One’s gotta be doomsday-prepped for the “Iscariots [who] litter the valley.” Judases like gutter trash clogging the storm drains on their way to committing Straight Up Sewasides. (Tough not to hear sweet chariots in those Iscariots, swinging low, coming for to carry them home.) ELUCID “fear[s] not the shadow.” He’s comforted by a rod and staff, by “peppermint and aloe poured upon the crown,” those same metallic medicinals mixed with herbs, science, and minerals that Bigg Jus big-upped on the Indelibles’ “Weight” in ’98. ELUCID is plannin’ to be rammin’ what he wrote straight on a plate down your throat—so digest, like Guru said on “Who’s Gonna Take the Weight?” His uzi weighs a ton, too. Words nurture and/or hurt: feast and/or famine. Yeah, boy-eee, that’s how you’re gonna carry that weight.

4.

On “Bazooka Tooth,” Aesop Rock dealt with “bugs in the beard,” while ELUCID, on “Spellling,” competes with bugs “in the bed.” He “crack[s] a couple eggs” (no doubt they’re double-yolked) and finds enchantment in the quotidian. ELUCID’s “waking to sounds of gnawing teeth and ecstatic squeals” (“Colony”), acknowledging “love sucks but [is] ill in other ways.” “Space is to be taken,” not given. Colonize the stars for your family’s sustainable living before some galaxy-brain startup puts down stakes. Breathe easy, but that’s Eazy-er Said Than Dunn, especially when, like Aesop, you’ve got “ebony in the lung-piece.” But, for ELUCID, maybe that ebony is a boon—an ebony chess-piece on the move: “All the places I’ve been,” locations like “South Jamaica, Queens to Strong Island, JFK, Sonic Boom,” each an impetus for ELUCID’s art. In White Man, Listen!, Richard Wright argued “expression springs out of an environment.” Ornette Coleman warned, “You can’t transcribe an environment,” but you can undoubtedly bring it into being.

5.

Just got to heaven and I can’t sit down.

Talking Heads told us since about ’78, ’79 that heaven is a place where nothing ever happens. ELUCID hints at an unsettled feeling—one can’t get too comfortable with the successes earned. The impulse is always onto the next. Child Actor’s panning of the sonics speaks to that ambivalence—the signal shifts channels like the difference between laurel-resting and no rest for the weary.

Heaven’s never really been heaven. On “Sweet Mickey,” ELUCID saw “pearly gates and dystopic visions.” Black liberation theologist James H. Cone explored notions of an “eschatological reality” that promised gold-paved streets and pearly gates, a home to lay down that heavy load. More often than not, though, the load just shifts to the opposite shoulder. Heaven and its requisite pleasures are always postponed. Speaking to the Federal Writers’ Project for the WPA in 1937, ex-slave John Collins pined for his wife Maggie, eager for their reunion in the afterlife: “us’ll see the sunrise, down here, from de far hebben above.” The fantasy vision of heaven is difficult to resist, especially when it’s spoken of as fondly as it is in “Big Rock Candy Mountain,” a land of milk and honey where the cops have wooden legs and the dogs, rubber teeth.

But as far back as 2Pac, Black minds have wondered if heaven’s got a ghetto. If Joy James is to be trusted, it sure as hell does. Quelle Chris reasons that “if heaven’s got a ghetto, hell’s got a resort.” If you hear Harry Belafonte sing the old hymn “O, Won’t You Sit Down?,” God requests the dearly departed to do just what the title invites, but they can’t: “Lord, I can’t sit down. / ’Cause I just got to heaven, gotta look around.” That look around is vigilance. Even heaven offers no reprieve.

6.

“Spellling” is so much, multifarious. The title could be fundamental, a reference to the recognition of patterns in words; it could reflect the act of casting spells, which ELUCID has copped to; or it could be a verb form of dizziness, our inner ears vertigoed. The obvious irony is the title’s [mis-]spelling with the three l’s, but that additional letter also drags the word out (the noise is love��I drag my tongue…), visually mimicking ELUCID’s cadence tendency to elongate sounds. Forces us to stay with certain words longer, cultivating patience. We’re under his spell.

DOCUMENT ii 7.

It’s too loud in here, ELUCID says on “Bunny Chow”—he can’t give full attention; he’s “got rocks in his head, / [he] didn’t listen right.” It’s too loud—too much static like wool fabric. His whole cabbage feels cracked. Rhymes do to his brain what bullets do to flesh, to pinch one from Thirstin Howl III. Ego and conscience refuse to share the same space. Yeah, it’s a Brooklyn hard rock—feeling Ripped Open by Metal Explosions with each horn stab (as arranged by Galt MacDermot). Sebb Bash’s squeaky-screamy voices do the lacerating here. Rocks in ELUCID’s head, like shrapnel “rattlin’ ’round, fuck what they said.” Stars circle our heads when we hear it. ELUCID is hard as hell—I don’t care who you tell. No delayin’ what I’m sayin’—he rocks the bells.

The meanings of these rocks are manifold. So much more than some ridiculoid mineraloid. Ivie Anderson, singing for Duke Ellington’s orchestra in 1941, complained about rocks in her bed—not head: “My heart is heavy as lead / Because the blues has spread / Rocks in my bed.” Her “man’s gone, [and] so instead” of his warm body beside her, she cozies up to stones. Or maybe the rocks aren’t in his head but in place of his heart, like Bessie Smith sings from the floorboards in Dudley Murphy’s 1929 short film St. Louis Blues. “My man’s got a heart that’s a rock cast in the sea,” she moans, singing of the pain caused by a philandering man. ELUCID doesn’t sound love-stricken, though.

In the “Rock Box” music video, Rev. Run and DMC’s heads become digitally dislodged and transplanted in a Frankensteinian experiment. They must be seeing stars. ELUCID is liable to “bang his face on the wall” in frustration, lose his head, too. Instead, he drops Hermetic axioms (“as above, so below”) linking his heady mental to THE ALL, as Swedenborg puts it. He refuses to play “safe and settled” and will instead “stray forever,” a tangential bindlestiff. The rocks in his head will keep rattling. And kids want to know what they mean? Do they spark? Do they gather moss? “They say pick one” answer, but I concur with ELUCID, and “grab three just to lose ’em on purpose.” He opts out of slinging crack rock and must have a wicked jump-shot as he’s “pump fakin’ when they [get] too earnest.” He’s hard-headed as long as he gets his shit[/shot] off.

“Who feelin’ bad for me?” he asks, bewildered at the notion. The promissory note’s been defaulted on, indeed, but ELUCID “didn’t ask to dream.” Hush that fuss, he says while “slumped” in the “back of the bus.” He’s the “last to leave,” outkasted, leaving it up for you to decide whether you wanna bump and slump with him.

“Mastery’s a winding labyrinth,” confusing at times, but ELUCID guides us on a Borgesian journey along forking paths, with hypertext and infinitudes at every turn. You’ve gotta just let the “patterns rearrange.” Disassociate if need be, have yourself asking: What happened yesterday? Likely, you’ve been warpin’.

DOCUMENT iii 8.

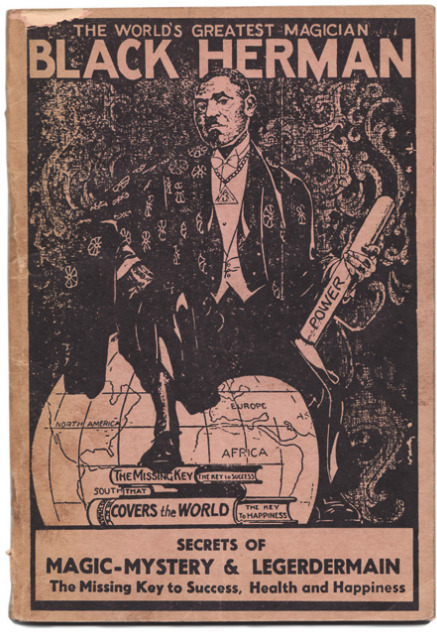

On 2016’s Save Yourself, ELUCID refers to himself as “Black Herman in a fugue state.” In Secrets of Magic-mystery & Legerdemain, Herman (born Benjamin Rucker) details his travels to Cairo as a young man. There, Herman writes, is “where all the secrets of the ages are held.” On “Old Magic,” ELUCID speaks of “cracked teeth gabbin’ in the pyramid,” and they may as well be Black Herman’s, seeing as how he had a proclivity for burying himself alive only to be exhumed three days later. Black Herman’s message to ELUCID: keep it cagey. “They wanna skin me alive,” ELUCID pleads. Don’t forget, the showboating satyr Marsyas was served in a rap battle by Apollo, kids. Got his hide flayed! Nat Turner too, lest we forget, was lynched and flayed by his captors. They sold his skin as souvenirs in storefronts. So, certainly, ELUCID is keenly aware of any and all “predatory denizens.”

9.

He will keep the feet of his saints, and the wicked shall be silent in darkness; for by strength shall no man prevail. —1 Samuel 2:9 KJV

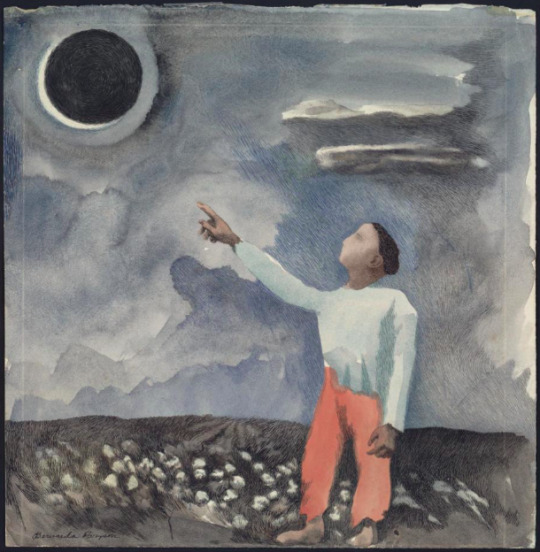

I spoke silent. None shall prevail. ELUCID watches his words: “Hush harbor—who’s asking?” On Small Bills—a project with a title that directly states Don’t Play It Straight—ELUCID’s version of “Hush Harbor” mentions a “silent moon” on a silent night. Quiet as kept. Put ear to earth and hear the quiet storm hissing on the ham radio. Nat Turner read both the skies and the scriptures for answers and stratagems. Witnessing a solar eclipse set his plans in motion. He was too wise to make his route while the sun’s out, like Prodigy, or unload ten in broad daylight. He worked those hush harbors—slave gatherings in the plantation woods. Gather, etymologically, implies both the uniting of rebel slaves and the cache of muskets they compiled. They were prepping for the “riot fire moon,” which was more about zealous insurrection than zodiac.

Despite losing his religion, ELUCID believes in much. He told us so on “Scaffolds”: “Don’t ask me no question, / I believe in Black secrecy.” Professor X of the X Clan knew the value of secrecy. “The FBI’s on me,” he says with his the red, the black, and the green lilt on his 1993 solo track “Confidentiality.” He recognized the need to keep it on the hush, on the down-low. Hush that fuss. Sit tight until you receive the signal. On “Hush Harbor,” ELUCID sensed it: “Finna catch a bad one, / I’m a thunderclap, son.” And that sonic shock wave reverberates, stretching backwards in time to Latyrx’s “Storm Warning” where Lyrics Born whispers: “Crashin’ and clappin’, the master craftsman / Passionately expressing his anger and his angst / With flashes and rains.” Such secrecy necessitates a sotto voce delivery, which—if you’re so so def—will make the dispatch impossible to hear. But ELUCID “be listening mostly,” and he’ll “keep it close.” According to historian Eugene D. Genovese’s research, authorities often believed voodoo priests were “stirring up hatred for whites, although this fear may have arisen more from the secretiveness of the ceremonies.” Peep the power in that. Sometimes a revolution sounds like a whisper—spin some Tracy Chapman for that truth.

10.

ELUCID stays appropriately guarded, understanding that “short fuses” equal “no future.” No future is a safety pin-through-the-skin sentiment, a punk gesture. “God Save the Queen” was originally “No Future.” Johnny Rotten joined forces with Afrika Bambaataa in 1984 to forewarn of World Destruction. Samuel R. Delaney has said that Black people find themselves “impoverished in terms of future images” because they were “systematically forbidden any images of [their] past.” Not so fast, not so bleak: bell hooks saw in Blackfolk a hunger for the promise of the future—what she called “yearning.” She writes of staying future-focused while still keeping an eye on the presence of past oppressions. Time is on my side, ELUCID repeated on “Flavor Flav,” but the Last Poets cautioned otherwise on “Run, Nigger”: “I understand that time is running out…(tick-tock, tick-tock, tick-tock). Running out as hastily as niggas run from the man…Time is running out of talks, marches, tunes, chants, and all kinds of prayers.” That being the case, one��s got to stay protected.

11.

ELUCID offers an incantation: “A double portion of protection for me and my niggas.” The refrain is instantly familiar—it doesn’t have to be repeated but is. Another line xeroxed: You ain’t gotta be here if you don’t wanna. We’ve heard this one before (on “Roaches Don’t Fly”), but what ELUCID says bears repeating. And if you’re opposed to rote learning? If you don’t believe in it? Double-up. The line’s meaning doubles, too. What sounded like the white cry of “go-back-to-Africa!” on the Armand Hammer track sounds like an acceptance of self-death on “Old Magic.” And who could blame a suicidal impulse, what with “Babylon all on us”?

Give me that old time double-consciousness as an example. “One feels his two-ness,” Du Bois wrote, “two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body.” A double portion of protection is needed to keep from being “cursed and spit upon.” Even though she had been “pitched headforemost into the world [and] landed in the crib of negroism,” it was only in college that Zora Neale Hurston began to “see [her]self like somebody else.” ELUCID’s demand for a double portion suggests a double helping—nourishment to feed on. Doubling abounds in Toni Morrison’s literature: twins, split personalities, mirrored reflections. A severing of self-representation. We’re seeing doubles everywhere, feeling dizzied and dope-sick. ELUCID is no one-dimensional man; his texts are heteroglossic (glôssa = “tongue”). He speaks in many.

12.

Child Actor adds the twittering of birds behind the chorus. We’ve heard this chatter of budgies before—think Preemo on “Nas Is Like,” a song rife with dualisms (“Freedom or jail…Heaven or hell…”). Might find yourself tempted to “assassinate two birds with one stone” like Vast Aire on “Pigeon.” On “Old Magic,” the birds are aflutter as ELUCID stands behind the acoustic foam of his isolation shield—his chair of augury—like the blind prophet Tiresias:

I heard A strange note in their jangling, a scream, a Whirring fury; I knew that they were fighting, Tearing each other, dying In a whirlwind of wings clashing. And I was afraid. I began the rites of burnt-offering at the altar…

The altar functions as a site of protection. A fortified live fortification. But ELUCID has told us, repeatedly (twice again), that we don’t really need altars. On I Told Bessie, we hear the claim on “Betamax.” On Small Bills, he said the same. Who needs an altar when you’ve got “hair braid maps, patterns, swamps, and pastures”? Time to be self-sufficient, dig our own ditches, and harmonize with hip-hop [perma-]culture.

ELUCID is protected by his words—words that can gank the noose out the mob’s chalky hands and use it for double-dutch. Stir up some Double Trouble like Rodney Cee and KK Rockwell on the stoop, raise a lot of hell. Get splashed with the “Double Dare green slime,” like ELUCID menaced on “Bitter Cassava.” That green slime no doubt a concoction of Macbeth’s three Weird Sisters, in an alleyway with a 55-gallon steel drum subbing for a cauldron, mere steps from the stoop:

Double, double toil and trouble; Fire burn, and cauldron bubble.

Purchase what you need from Paul’s Boutique and throw all of that shit in: poison’d entrails, fenny snake, wool of bat, owlet’s wing, baboon’s blood, root of hemlock digg'd i’ the dark—that’ll make the hell-broth boil. That’ll make for “a charm of powerful trouble,” a charm that is “firm and good.”

13.

In Look Out, Whitey! Black Power’s Gon’ Get Your Mama!, Julius Lester describes how “language serves to insulate a group and protect it from outsiders.” Words, see, can bulldoze walls or build them. Words are an S1W security force on stage, stalking, walking in their big black boots (like X Clan’s Grand Verbalizer said, like Ice Cube endorsed— ’cause you never know when they’re gonna shoot.) On “Jumanji,” ELUCID claims he has the ability to “will weapons when [he] wants ’em.” He’d already established that fact on Valley of Grace: “No matter what you do, don’t call me an artist. / My bars more like an arms race.”

Protection could be maximized if you worship Rammellzee’s Garbage Gods—Gasholeer, perhaps, whose exoskeleton looks like an electronics wasteland, like a “junkyard Transformer doing samurai cosplay,” in Hua Hsu’s estimation. Rammellzee’s own description of Gasholeer’s armor dazzles:

From both wrists, I can shoot seven flames, nine flames from each sneaker’s heel, and colored flames from the throat…. The sound system consists of a Computator, which is a system of screws with wires. These screws can be depressed when the keyboard gun is locked into it. The sound travels through the Computator, then the belt, and on up to the four mid-range speakers (with tweeters)…. A 100-watt amp and batteries give me power.

When those systems failed, Ramm could resort to his ikonoklastik philosophy, which “abolish[ed] age-old standards of language and meaning.”

14.

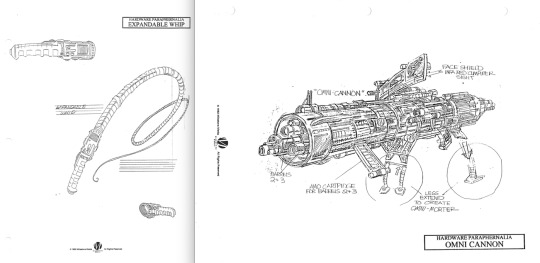

Gasholeer’s protective armor anticipated Hardware’s, a Black superhero created by Dwayne McDuffie and Denys Cowan for Milestone Comics in 1993. Hardware (Curt Metcalf) is a brainiac working in the laboratory of Alva Industries. Disgruntled, Metcalf hides the company’s high-tech gadgets—gadgets of his own creation, mind you—in the bomb shelter of his exploitative employer’s building, like an ungovernable slave burying hoes and pickaxes in the dirt behind the plantation barn, just waiting for the right moment. Metcalf becomes Hardware as he outfits himself in an arsenal formidable enough to take on tanks. He rocks plasticized metal alloy skin, stays layered in nano-robots (“antimatter nano-nigga—shit, I had to hit him”), and comes strapped with an array of weapons. I mean, damn…Hardware might as well author Negroes with Omnicannons. He brandishes an expandable plasma whip, avenging Whipped Peter like Django unleashing on Little Raj.

ELUCID’s “double portion of protection” opens up a new continuity of safety and security, a panoply of revolutionary self-care and nickel-plated pockets in the spirit of Rammellzee and Curt Metcalf. Even still, when the system fails after hackers emerge from the darknets and the language of spells don’t work as desired, make a swift pivot to charms.

DOCUMENT iv 15.

I got a black cat bone, I got a mojo tooth, I got John the Conqueroo, I’m gonna mess with you.

—Willie Dixon, “I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man” (1957)

On Armand Hammer’s “Charms” from Shrines, ELUCID invokes the codices of the Nag Hammadi and mysteries evoked by “smudge stick fragrances.” Sage wonderings. In the second verse of “Old Magic,” we arrive at a sandy and silty inlet “steps from the ocean.” He brings us places. This time to a ritualistic burial at the seaside where maybe, just maybe, he can “raise the dead with the brain-poem,” as Hell Razah might say. Look skyward to the “celestial motion” of the universe where “recorded research [is] often repeated”—a triad of re- prefixes—again and again, doubling and re-doubling. The same can be said for “who holds the one who holds the secret”—a circularity to these processes, knowledge of self within a multiplicity of selves. Gotta keep at it like a tongue touching a cankersore on the “cheek of the godhead.” Understand the high cost of living and dying, how it siphons spirituality from a skull: “5K to put a body in the earth, / Twenty bucks to wear your face on a shirt.” Morgue slabs like conveyor belts as lives are proven cheap and deaths are commodified.

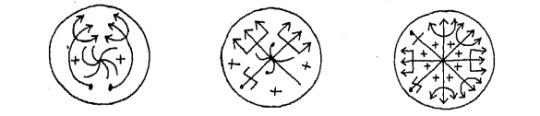

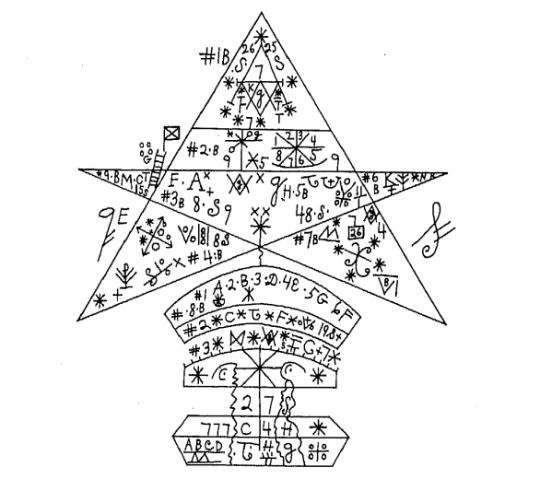

ELUCID fills the role of ritual leader, carving ground-signs with a debarked twig: “spiritual notations, miniature cosmograms, the numbers of certain Psalms, and ciphers received in trance,” according to art historian Robert Farris Thompson in Flash of the Spirit. ELUCID pulls out all the stops to salvage a soul: “Washed you in the surf, burning pyres, / Tossed the gold in purifying fires.”

“Get thee behind us,” he demands, omitting Satan from his sentence, but we know who the devil is, the “hogtied swine.” (Sooey!) The devil’s a master of magic, too—infamous for his disappearing acts, for making Black bodies vanish. Like Danez Smith says, “now he’s breathing, now he don’t. Abra-cadaver.” So ELUCID is incisive with his critique, “harpoon-sharp from out the wave cap,” nautically punning on his accoutrement even as his voice nearly gives out. The formula is simple: spell the words and the words make spells (I’ve been spellling…). On “Old Magic,” ELUCID counters with a “doom gospel spell” and calls himself a “revelator, armed and dangerous.”

Not the only time we hear it. “I’ve been revelatin’,” he informs us on “Smile Lines,” and “there’s information and information only.” Fifty people at a rap show—one’s an informant, but we’re working with better info here. This be the Info Kill. On “Ghoulie,” he lets us know that “since the face got revealed, game got real,” tipping his flap cap at Ghostface. I Told Bessie is equal parts spellling and telling. Credit Son House: Tell me who’s that writin’—John the Revelator—wrote the book of the seven seals. The MC seer has shown and proven his prophesying skills, but the truth of what’s to come is ever-unfolding. “Be advised they’ll come, / From a pure black whirlwind,” Myka 9 sings on “7th Seal.” Myka, like ELUCID, is on the lookout, watching “the entrance [for] when they fled from the living dead, / [With] smoke burning magical, sparkling exuberance.” We’re being told where to look: X mark the spot. Everyday equations. Tally up the x’s—the solution is redacted. The solution is xxxxxxxx.

16.

“When she inspected us once a week, you better not have no charm around your neck, neither.” —Prince Johnson, ex-slave, Yazoo, Mississippi

On “Ghoulie,” ELUCID doesn’t merely lift the veil, he “split[s] the veil”—leaves the temple curtain torn, entryway open: NOTAFLOF. Split the veil and break the boundaries between the living and the dead, the black and the white, the rich and the poor. “If somewhere in this whirl and chaos of things there dwells Eternal Good,” Du Bois wrote in The Souls of Black Folk, “then anon in His good time America shall rend the Veil and the prisoned shall go free.” But what of other forces keeping the Klan hoods stitched and sewn up?

“Black cat is bad luck,” MC Serch rapped on 3rd Bass’s “The Gas Face.” ELUCID fought off such portents, even in the safety of Bessie’s house. “She had cats that attacked me—always black cats,” he told KEXP’s Martin Douglas. (Hear the cry of “Black cat on the landing!” on “Smile Lines.”) He’s previously called himself a Negromancer (“My Blank Verse”), and on “Ghoulie” he navigates “two worlds” but with the “same spirit.”

In his Africadabra sequence of poems, upfromsumdirt writes: “…don’t worry, you sad / sad-sack, this poem is summons, is conjury, is chimurenga.” He goes on:

you’re too young to feel this un-undoing, but I have a country houngan’s perfectly

symmetric hips thrusting high-resolution juju for this brand new era.

ELUCID’s high-res juju is evident as he gets hectic with the syncretic beliefs—heltah skeltah with a welter of gris-gris made easy. “Blood, fat, and sinew congeal,” he recites, his hands no doubt gesturing madly. He’s up against a lot—all tools in the shed sharpened on the grindstone. In “Ere Sleep Comes Down to Soothe the Weary Eyes,” Paul Laurence Dunbar demonstrates just how daunting shit gets:

How all the griefs and heartaches we have known Come up like pois’nous vapors that arise From some base witch’s caldron, when the crone, To work some potent spell, her magic plies.

Sometimes you just gotta Tituba your troubles away.

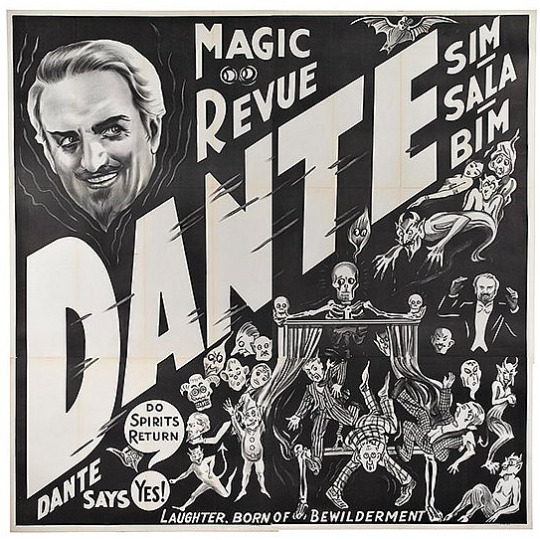

ELUCID recited the magic words of Zim Zala Bim on “Solarium,” a trick based on [supreme] mathematics with no sleight-of-hand required—just words and numbers in a potent mix, like coding. He puts the rhythm in algo-. Builds and destroys with each opening salvo. “I practice many practices, you asking for the secret?” Holy polyptoton!

17.

In a section of Black Herman’s text entitled “To Cross or Hex a Person: Cast a Spell—No Matter Where,” Herman personally recommends Confusion Dust. ELUCID keeps fistfuls of grave dust gathered into a palm and blows goofer in the eyes of his opps. Make something out of nada: “I pulled it out the sky—nothing short of awe, / I willed it out the earth—true grit.” Charles Portis knows such canniness is too legit to quietly ignore.

ELUCID’s words should be interpreted cosmogrammatically—each phoneme a “point” between the living and the dead; each verse a charm in a crimson cloth container; his bars the crisscrossing cords enclosing the spirits. He speaks with “phrases forceful, / old magic spooned by the morsel.”

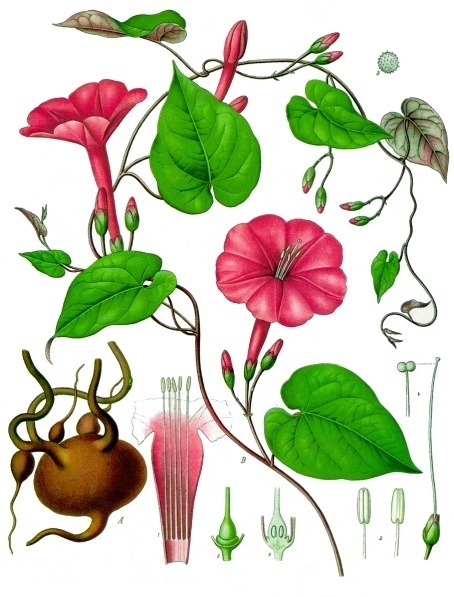

He’s been on the Root Farm, a hex-breaker for hire, with the “gnarled and twisted” High John the Conqueror root (Ipomoea purga) in his pocket. “[T]here are anti-hex roots galore throughout black America today,” Robert Farris Thompson writes, “usually wrapped in red flannel, ‘so that nobody can put evil on you—if they do it will turn on them.’” ELUCID’s got the goods; check the “mud under the nails, / [the] smell of swamp moss and dead things.”

18.

“This is a liberation séance,” ELUCID declared on “Dettol.” The Lasso narrates the séance with noise. His water torture drip on “Ghoulie” manifests what Jeru and DJ Premiere only hinted at on “Come Clean.” Charms are analog, which is well and good since ELUCID’s “magnetic field fuck[s] up electronics.” Be it VHS or Betamax, all it takes is a bipolar horseshoe magnet to erase the tape, delete the evidence in a “scatterbrained, spatter wave” of jagged lines along the grayscale. Outmoded technology can’t compete with these spells. This old magic fails to stale, stagnate, or corrode like battery acid at the terminals. We hear the breakdown:

Go inside. Close your eyes. Close your mind.

The Lasso creates a cousin composition to Radiohead’s “Pulk/Pull Revolving Doors”—apt, because we’re sucked through dimension portals, for certain. Colin Greenwood, speaking to Kodwo Eshun, described how the band collected “found loops” and “disabled the erase heads” on tape recorders to allow the loop to record “over and over on top of itself.” They added some keyboard notes “to create this ghost repetition melody.” The Lasso brews a ghoulie repetition melody, syncing with Rakim’s formula from “My Melody”:

My melody’s in a code, the very next episode has the mic often distorting, ready to explode.

ELUCID’s voice and entire being becomes washed over in reverb and swelling distortion (“rushing power washing over”), drowned in baptismal waveforms (“born-again in the living waters”), smothered in a “static blanket,” but he still feels “more splashy than splashy is.”

19.

All pigs of ill repute. —“Bleachwater”

“One [conjurer] put a spell on the master to keep him from noticing that the slaves were stealing hogs for weekly barbecues,” writes Genovese in Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made. The spell worked until the master, feeling big and bad (in the sardonic words of Quelle Chris), started to count the hogs. (Sooey!) The slaves “got caught with the pork,” as billy woods says on “Chicharrones.” The anecdote shows the limits of spiritualism. Some slaves questioned the power of conjurers, seeing as how they “couldn’t make ole master stop whipping…but they could make Negroes crawl to them.” Where honkies appeared impervious, fellow slaves appeared susceptible, rendered so by unshakeable belief. In a world of such organized konfusion, ELUCID is ordering chaos through rap, he told KEXP. “I don’t get the star talk,” he confesses on “Nostrand” (and “My fist refused to have its palm read” on “Old Magic”), demonstrating a mighty healthy skepticism—vibing with Voltaire in that respect—circumspect of astrology shop owners who hawk amethyst rocks and peddle Obama incense. If the old rumor is Blacks become immune, it’s worth interrogating. (Ghostface whispers, Psst! We never did.) Eating dead birds? Trust the pharmacy over herbs? So what does ELUCID believe in? “I believe in Black people believing,” he chants on “Betamax.” I believe, I believe in Black people believing. Speak it aloud to yourself: you can feel the balm of the bl- consonant blend in the repeated “Black” and “believe,” feel the yearning in the long-e assonance of “believe” and “people.” The epanalepsis of the line proves the hardiest belief is one which bolsters Black people keeping faith—hope begins and ends with them believing in whatever they choose to.

DOCUMENT v

20.

“I have twenty girlfriend, man, you want some?… I will give it to you…. Girl like big dick!” —Animal Cub, “Animal Thug Interlude” (1998)

ELUCID shares his freaky tales in Telex type on “Sardonyx.” Whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa, he says at the outset—a plea to please slow your roll, or feigned shock at what’s about to be said? “He’s from the era of the Animal Thug,” so we should doubt he’d be fazed. Stare into the sardonyx stones and see Jupiter’s chemical clouds swirling—that shit looks sexy. “Sniff pussy,” ELUCID raps, “she suck my thumb before me member.” Too $hort might shudder. Even his “freak” named Betty whose “pussy got wet and it smelled like death” feels mortified.

“Wet enough to enter, / Blue movie gal—no censor.” ELUCID masquerading as the world-renowned Dr. Octagonecologyst? Sniffing all the Blue Flowers in the garden? (He notes “fresh flowers in the lab” on “Split Tongue,” and on “Betamax” he eyes flowers and “chose the blue ones.”) At the very least, he’s Kool Keith stuck on pussy drive from 1997’s Sex Style. The pleasure and death drive mingle blood. The drive-shaft trembles; a vibration is cumming from the chassis. The phallic condenser mic throbs as ELUCID “snap[s] necks like fine bones from the mackerel,” the crack of successive k’s fit for an S&M experience. In 1970, Lloyd Addison described how his lover’s “neck is an umbral stem mooring nude euphoria.” Mercy! [Roy Orbison growl, but with the ecstasy of 2 Live Crew being acquitted of both obscenity and copyright infringement charges.]

Don’t act shocked. On “Spellling,” ELUCID hinted at the rendezvous to come: “When I fucked you, it was worth the wait, the rhyme and reason.” The affair is poetry, the Petrarchan sonnet variety. This is Enter the Poon-Tang (36 Bloody Chambers), and Sebb Bash’s pornocore production on “Sardonyx” includes enough moans and heavy breathing to set the mood.

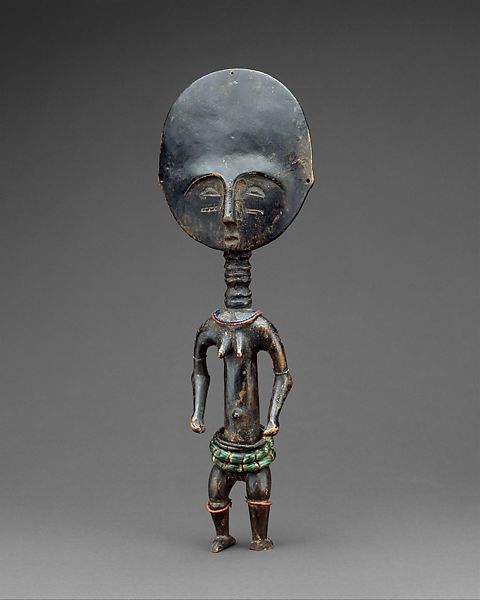

ELUCID humpty humps his way to the front of the stage like a Catholic priest desecrating the church altar with two dominatrices. From the lectern: “Black pussy is the world’s first religion!” We heard it on the scandalous “Fuhrman Tapes,” but on “Ghoulie” we hear ELUCID’s “base desires overflowing.” “Baby, please pop that pussy for breakfast,” he begs, desperate to up jump da boogie-woogie. Jelly Roll Morton at his raunchiest still blushes at the sound of this. ELUCID romps with an Akua’ba fertility figure shaking on the dresser. He’s a hoochie-coochie mannish boy armed with minkisi. He can’t contain himself. Turn me loose; I’m too juiced; …the jazz is free, he said viciously on “Scrapes” with a high viscosity. “The word ‘jazz’ is probably creolized Ki-Kongo,” Robert Farris Thompson wrote, tracing its etymological roots, “it is similar in sound and original meaning to ‘jizz,’ the American vernacular for semen. And ‘jizz,’ suggestive of vitality, appears to derive from the Ki-Kongo verb dinza, ‘to discharge one’s semen, to come.”

On “Sardonyx,” billy woods comes through, too, getting in on the aksion. woods opens his verse with a line of iambic trimeter: “Muff-diving, no snorkel.” Six simple and seductive syllables separated by a caesura (an exhausted exhale in this case). woods frames sex as sport with oodles of encouraging and homoerotic ass-slapping. Sex is sloppy here, a statistical mess. Scorekeeping Wilt Chamberlain’s 20,000 concubines with analytics. Record-setting frolics across the gridiron with Blake Bortles and Gale Sayers. In Robert Coover's 1987 novella What Ever Happened to Gloomy Gus of the Chicago Bears?, Gloomy Gus is a man who makes sport of sex and sex of sport. As he nears his downfall, Gus’s sculpter-friend Meyer describes him so:

“He even turned his meals into practice sessions for testimonial dinners, pickups, biting in pileups, and muff-diving, so as not to lose time. He—” “What diving?” “You know, with the mouth—” “Oh! I thought you said muff-diving…” “I did, Golda. A muff’s, you know, for keeping your hands warm—” “Ah!” she says, blushing, and puts my hand between her legs.

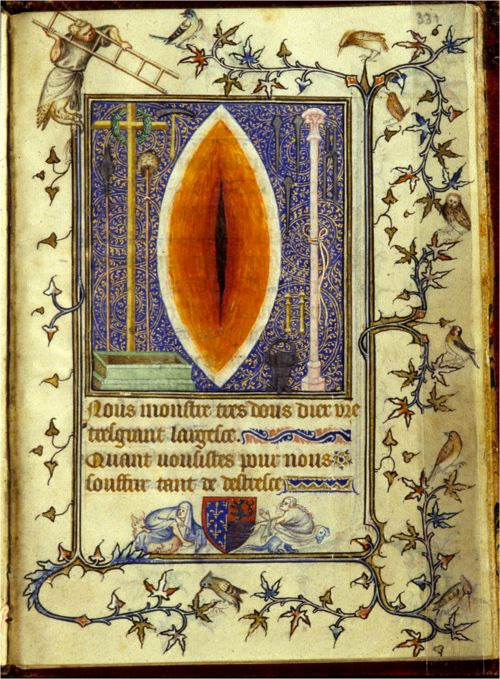

In Caliban and the Witch, Silvia Federici notes the repressive regimes of the mid-16th century, forces that ensured “nakedness was penalized, as were many other ‘unproductive’ forms of sexuality and sociality.” ELUCID’s claim that “ass taste better in the summertime” on “Bitter Cassava” certainly wouldn’t be welcomed. To “split her thigh” would be a risqué and risky act of rebellion. ELUCID doesn’t just spit filth at the Vagina Diner, though; his sex raps express the amor profano and pussy-pedestaling of a Renaissance painting—he puts the tit in Titian. Sex raps like Christ’s mandorla-shaped wound in the pages of Medieval manuscripts—a heavenly-level of Holiness (hole-iness). ELUCID’s sex raps are erotic symphonic. His opening yo’s are yonic as fuck, friends.

DOCUMENT vi 21.

Folks feel at ease when you smile. —“Touch & Agree”

Theologian Thomas Müntzer wrote, All the world must suffer a big jolt. August Fanon’s raucous production on “Smile Lines” achieves that. He summons the blackest Sabbath on record. The fuzz-and-chug electric guitar sample jostles us and causes us suffering (dukkha) in the Buddhist sense—a samsāra cycle that keeps on keeping on like the Winstons’ Amen break: an eternal loop. Grit your teeth and bear it. Grin through the pain. Force the smile. Stand mesmerized by the cry of the sun-burst Stratocaster. Smile lines might be the result of joy, but they only emerge through ages of pain, stages of grief, pages of books read and forgotten. Contrary to what Son House sings and stomps, you definitely should mind people grinnin’ in your face, as they will try to crush you down. Easy A.D. of the Cold Crush Brothers boasted, “All I got to do is smile, and I get screams” on 1984’s “Fresh, Wild, Fly and Bold.” Were they screams of joy or screams of horror? ELUCID smiles big for the camera; he’s also “smiling in a cloud of jerk smoke” on “Jumanji.” I Told Bessie is fulla joy, but it would be misguided to say that’s all there is. Think of Scarface’s “Smile.” “I often wish that I could save everyone,” he growls. Study the guttural gut-check in his pronunciation of smile at the end of his verse, a lower octave blurt.

ELUCID’s got locational awareness—he knows where he’s from, where he’s at. He conceived what he calls these “mutant blues” after reflecting on the bloodshed of his block in Bed-Stuy: do or die. In 1964, fifteen-year-old James Powell got murdered by NYPD, and the subsequent truncheon-to-skull scenario up and down Nostrand Avenue still reverberates. (In the words of Swans’ Michael Gira: “Nothing hurts them like a cop with a club.”) Same historical tremor as how they build it on Indian graves. Omens everywhere: “fear of plague,” “hoof-and-mouth to pox,” “broken bone.” The crime scene’ll have you seeing red. “The deceased requested you all wear red,” ELUCID raps. Whether it’s the dress code of Bloods, or blood, or Redman’s red-saturated Dare Iz A Darkside album cover—ELUCID listens to the “voice from cold earth,” Reggie Noble’s scream of agony buried alive in dirt, pilloried, with transmission towers pillared on either side of him. Those towers transmit volts back in time to Funkadelic’s “Maggot Brain”—another screaming head in the soil. ELUCID appeals to “blank souls from [a] generation not [his] own.” George Clinton comes through the wire; he and Eddie Hazel tripping on acid and pondering the most recent State-sponsored assassinations. I have tasted the maggots in the mind of the universe, Clinton says. Eddie Hazel’s guitar is the “Smile Lines” guitar: echoplexing for the “black motorcade” to hear. On “Nostrand” (that addled avenue in Bed-Stuy), ELUCID gave the instructions: “Exit mothership.” But Funkadelic insisted on the mothership connection—stay in tune. “I told him to play like his mother had died,” is what George Clinton told Hazel. “Smile Lines” and “Maggot Brain” prove the same postulate: there is no life or death.

22.

ELUCID divulges that “she been open since her moon dropped,” hyped and prepped to “turn the bass up, [and] straddle her boombox.” Like some perversion of Black Moon’s “I Got Cha Opin”—I know, kid. May I opine: some mating dance correlation between moon and menses. Recall the “moon blood [that] ran red forwards and backwards” on “We Don’t Really Need Altars.” Recall Hecate, that “mistress of charms” and “contriver of all harms” posted up on the heath in Macbeth:

Upon the corner of the moon There hangs a vaporous drop profound; I'll catch it ere it come to ground: And that distill’d by magic sleights Shall raise such artificial sprites As by the strength of their illusion Shall draw him on to his confusion

That slow drip of a “vaporous drop” from the “corner of the moon” guarantees witchy ways. But ELUCID “came back with [his] word intact” anyway—flashing a “smile line like Valley of Death.”

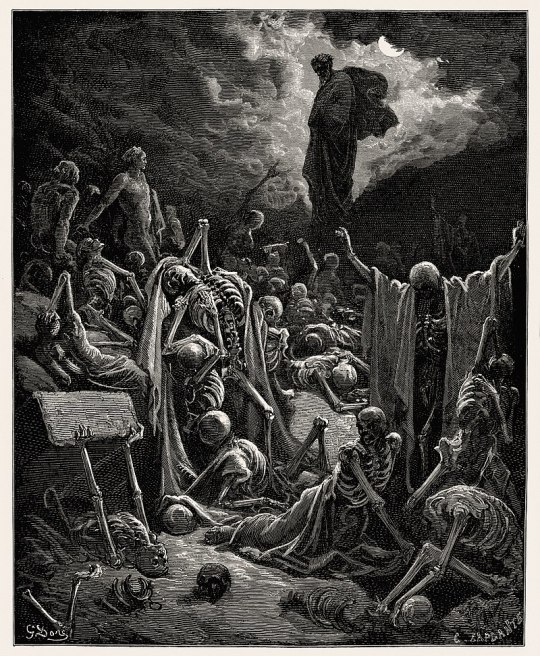

On “Aubergine,” ELUCID pauses “in the valley.” He “take[s] [his] time for a spell being strengthened”—he double-entendres the spell: reprieve and incantation. So necessary. Valleys are depressions, low-points, but ELUCID sounds like he’s peaking when he wanders them. The aforementioned Iscariots who littered the valley are still present. In Ezekiel’s vision, God instructs him to return life to the scattered bones in the valley, a mass zombification:

So I prophesied as I was commanded: and as I prophesied, there was a noise, and behold a shaking, and the bones came together, bone to his bone.

And when I beheld, lo, the sinews and the flesh came up upon them, and the skin covered them above. (Ezekiel 37:7-8 KJV)

Dem bones, dem bones, dem dryyyy bones—the lyrics James Weldon Johnson left us to sing. Give “the liquid to the dry bones,” like Hell Razah says on Sunz of Man’s “Cold.” Hell Razah and Shabazz the Disciple stalking around Red Hook, traversing the valley. ELUCID sees them from his grandmother’s window.

DOCUMENT vii 23.

We reach an impasse. Relationships expire; love lingers like smoke. What was supposed to be everlasting is reduced to last licks. Last good kiss. Last call. Bessie Jones sings, “This may be the last time we sing together”—I don’t know.

ELUCID functions as a living breathing griot most times—god of the uprising. Storyteller, yowler, and yeller. His inner city blues make him wanna holler. But on “Impasse” he feels “a stranger to [him]self”: There’d be no blues if I was blameless. Inner turmoil. He approaches the Park Bench People with cornbread in hand. Maybe they’ll listen. He raps as if he fucked up. He can “feel the certainty slip around [his] neck,” certainly a bad sign—hopefully not a noose; possibly an albatross. He’s going through it. Longing for a “familiar deep groove,” but he lost it in the flood.

In Black Talk: How the Music of Black America Created a Radical Alternative to the Values of Western Literary Tradition, jazz critic Ben Sidran explains how “blue notes” are “areas in the scale where tones [are] smeared together through melisma.” The cries and moans slaves introduced to Western songs, Sidran contends, were dismissed by white listeners as “overemotional.” But what those flat thirds and flat seventh steps actually presented was a new tonality, a fresh matrix of meaning. If you missed it or ignorantly blissed it, your loss. Leadbelly said the blues is “a feeling and when it hits you, it’s the real news.” To paraphrase Saidiya Hartman, Is it real son, is it really real, son? Let me know it’s real, son, if it’s really real.

How does he manage? How is he “pushing out and through”? He cozies up with cultural past—artifacts full of “sound and fury” that presently signify nothing. “I sing a simple song,” he says, but there ain’t no riot going on. Everything is “quieted and calm.” Too quiet. Elsewhere, he wasn’t scared to turn a phrase—make its skull snap like a b-boy headspin in a hazard zone: “Signed, sealed, sympathizing in real time.” But now he’s empty of sympathy and full of regret. Stevie Wonder couldn’t cheer him.

DOCUMENT viii 24.

“Of all the spirit manifestations, the simplest and most frequent are noises and raps…. [S]pirit noises have peculiar characteristics, with variable intensity and tone, and which makes them easy to recognize and not to be confused with creaking wood, crackling fire or the dull tick-tock of a clock. The raps are dry, sometimes muffled, weak and light; sometimes, loud and distinct, even noisy, and they change places and repeat themselves without any mechanical regularity.”

—Allan Kardec, The Book of Mediums (1861) | Chapter 5: Noises, Rackets and Disturbances

Bessie Hall, who passed in 2017, hovers over the album—a benign spirit visiting to see if everything is going according to plan, man. ELUCID’s conversations with his grandmother persist. “I feel her every day with me since she’s left this plane,” he has said. Years earlier, in an intergenerational home in Crown Heights, she heard him through the walls. Tendrils of chocolate thai smoke penetrating the plaster and floorboards. Like a gentle eavesdropper, an aureoled elder guarding his process. “She’s hearing those formulations,” ELUCID told KEXP. “I’m upstairs on the third floor; she’s on the first floor. And she’s hearing me rap, she’s hearing these spells anytime of day or night.” This album is an in memoriam work, a gesture of Tennysonian “immortal Love.” Each song pulsates and flickers like “orbs of light and shade.”

At the time, I frequently met with an excellent writing medium, so the next day I questioned the spirit who normally communicated through him as to what had caused the raps. The spirit answered me: “It was your familiar spirit wanting to speak with you.” “And what did he want to say to me?” “You can ask him yourself because he is right here.” […] He pointed out errors in my work, indicating the exact lines where I could find them. He gave me useful and wise advice and added that he would always be with me and would answer me whenever I wanted to question him. Since then, this spirit has, in fact, never left me. (Kardec, ibid.)

The album, of course, is a testament to the woman whose name graces the title. The work praises her role as educator, [holy] comforter, and radicalizer. Bessie Hall’s presence looms far beyond her individual self though, extending to a multiplicity of shadow Bessies. We can squint and see a semblance of what else is spelled out and told.

25.

Well, dey lef’ po’ Bessie dyin’ wid de blood (Lawd) a-streamin’ down.

—Myron O’Higgins, “Blues for Bessie” (1945)

The Death of Bessie Smith, Edward Albee’s one-act from 1959, tells the apocryphal story of a whites-only hospital’s refusal to treat Bessie Smith when she arrives at the ER after her car wreck. The tone of the play is set by “The Father,” a belligerent southern racist who tells his daughter (one of the ER nurses and a racist herself) how injurious her music choices are: “I said, I got a headache; you play those goddam records all the time; blast my head off; you play those goddam nxggxr records full blast…me with a headache…. Damn noise! That’s all it is; damn noise.”

There’s no shortage of telling in the play—“tell” in the sense of unintentionally revealing one’s truth, and “tell” in the sense of communicating a message. “I got an injured woman outside in my car,” Jack tells a nurse. (Jack is Bessie’s driver who brags of his shrewdness and business acumen in managing Bessie’s affairs: “Look, you don’t have no exclusive rights on Bessie.”) “Yeah? Is that so? Well, you sit down and wait,” the nurse tells Jack. Invoking Bessie Smith’s famous name doesn’t gain Jack any favors: “I DON’T CARE WHO YOU GOT OUT THERE, NXGGXR. YOU COOL YOUR HEELS!”

“I told him to go on into Memphis,” an orderly tells an intern of what he told Jack. “You been told to move on,” the nurse tells Jack. “You don’t have sense enough to do what you’re told.” Jack is insistent: “I told them…I told them it was an emergency…I said…this woman is badly hurt.”

26.

They sat silent, looking at each other, waiting. He saw Bessie’s shoulders jerking in rhythm to the music. Would she help him? —Richard Wright, Native Son (1940)

What nigga don’t got a little Bigger Thomas in his brain-box? —billy woods, “Native Sun”

In Native Son, the notorious Bigger Thomas toys with telling his girlfriend Bessie what he’s done. “Bigger, where you get this money from?” she asks. “Maybe I’ll tell you some day,” he teases. Later, Bessie longs to know what Bigger’s thinking: “Tell me. What is it?” She insists on knowing, seeing their candor as transactional: “I told you what was on my mind, but you won’t tell me what’s on yours. That ain’t fair.” But Bigger sees Bessie as a double: “there were two Bessies: one a body that he had just had and wanted badly again; the other was in Bessie’s face; it asked questions; it bargained and sold the other Bessie to advantage.” Bigger wants to exploit the former Bessie and kill the latter, “sweep[ing] away the Bessie on Bessie’s face.” Eventually, Bigger discloses some of the details of what he’s done, only to browbeat Bessie when she expresses concern. “You wanted me to tell you; well, I told you,” he snaps spitefully. When Bessie ultimately discovers what Bigger’s done, she’s stunned: “You told me you was never going to kill.” Bigger’s rejoinder: “They white folks. They done killed plenty of us.” From that point on, Bigger sees Bessie as nothing more than “a dangerous burden.” He rapes and murders her, disposes of her body down an air-shaft, “down into blackness.” Native Son presents an entirely different form of telling—of snitching, of conspiracy, of subterfuge. Adrienne Rich might say Bigger Thomas destroys Bessie through lies, secrets, and silence.

DOCUMENT ix 27.

“Mangosteen” joins stonefruit, black garlic, cassava, and artichoke in the cornucopia of nourishment that ELUCID and woods offer up to the audience. woods hears like we do: attentively, atmospherically, with pin-drop precision—a bodhisattva of the blaring. “My sleep app is Negroes arguing and wailing sirens,” he raps, noting the cacophony. But it’s followed by “sudden silence.” It’s in this silent space that ELUCID’s sorcery can enter and penetrate our bony labyrinth.

ELUCID’s signifying is slippery—not a step-on-the-banana-peel slapstick slip, but a [CL] smooth transition into satori. “I can’t keep the same style, so you can’t hold it either,” says everything. He shows the verbal versatility of Volume 10 who counseled it’s “too late for slipping.” Each sentence ELUCID spews is a sigil beyond your immediate understanding: so sit with it, goddamnit. Listen to his “voice like ten thousand wind chimes,” as he puts it on “Nostrand.” But don’t be lulled into a false sense; he keeps the pistolgrip-pump on his lap at all times. He will “bust your shit,” and he “don’t mean to sound facetious” (emphasis on sound). “Nostrand” should’ve left you on high-alert. Be “careful where you step” is what he said—because he’s “Flexi with da Tech.” Rest assured (nah, nah—rest absurd): not a TEC-9, but the Artifacts’ tech(nique) you heard about in ’94. Tame One and El Da Sensei in Newark, New Jeruzalem promising to “kick your ass with [their] apparatus.” ELUCID “can’t keep the same style,” and the Artifacts?—“never could you copy ’cause [their] style’s quite odd.” Word weapons and large-caliber linguistics. “I can’t get off unless I warp it,” ELUCID raps on “Betamax,” proving it’s a matter of taste and preference. He “divorced a wildstyle and got a new one,” free to shift affection from PHASE 2 to TRACY 168—he’ll “never force it.” He’s malleable from out the mouth.

28. The exorcist is not only a minister of the Church, but he is also a doctor of souls.

As you check the technique, also scan the parallelism:

You talk out your neck— I curse from my core.

You versus I. The verb talk versus the verb curse: one connotes drivel; the other, datura-like speech-substance extracted from earth. The weak preposition out compared with the girded from. The neck an encasement of sinews, ligaments, and nerves; meanwhile, the core is the churning hearth, the diaphragm, the nucleus. And it’s “ladders stacked from [this] center.” And it’s “turtles all the way down.” And if you don’t know, now you know (you know)…

On Armand Hammer’s “Flavor Flav,” ELUCID asked whether you could find the level of difficulty in this? Difficult, yes, but also joyful. His shockadooming is ludic—he delights in play. That’s why he “pop[s] a wheelie” on his Dyno on “Jumanji.” The chopping is improvisatory; his enunciation, nimble. The timbre and pitch of his voice is always in flux. Sometimes the larynx and lungs are billy goats gruff—rough and stuff, loud puffs. He thrashes the vocal cords and threshes the plain. His cadence, meanwhile, is flagrant—modulating his voice like Linda Blair with a throat ache: exorcizing the rising of red tides and the lowering of caskets. The blues were long considered “devil music,” and Buddy Bolden, a transitional jazz figure and psychotic, off wayward from the parade route, would play in Tin Type Hall, “a room used as a morgue by day and a dance hall by night.” ELUCID channels Bolden’s ghost—his phonal-tonal productions occupy both club and crypt. He confronts Loosifa and also takes cues from Greg Nice and Smooth B: Sometimes he rhymes slow, and sometimes he rhymes quick. Even ELUCID’s introductory yo’s demonstrate the point: they aren’t simply yo’s, they’re artful yaw’s and yuh’s—glasscutter musical greetings.

29.

Harmolodics allows a person to use a multiplicity of elements to express more than one direction. The greatest freedom in Harmolodics is human instinct.

—Ornette Coleman

ELUCID’s been rehearsing with Ornette for what seems like ages, nonstop, and so he harnesses the Harmolodics with his voice like Coleman did on his saxophone. His sound grammar commutes from country to cosmopolitan, from concrete to cosmos. The tonality is intuitive. When he opts for the rasp, he rakes us over the coals only to tend considerately to our raspberry fields. An architect when he writes these poems, writes these poems, writes these poems…. A choked-up Chaucer; there’s no rules to this spellling. (The notion of a single correct spelling is a relatively new idea.) Child Actor’s production pans again—wildly, vertiginously. Years ago, Samuel R. Delaney said “our technology is becoming more and more like magic—with a class of people who know the incredibly complex spells and incantations.” Fair to assume he was foreseeing figures like Willie Green.

DOCUMENT x 30.

O, let no false nor spiteful word Be found upon your tongue; Roll, Jordan, roll!

—“Roll, Jordan, Roll,” Traditional (Roud 6697)

Say less on “Split Tongue,” for we’re in the thick of the séance smoke now: feel privileged. Slowly drowning in piano keys and bass tones; lifted up by a horn, a salpinx without question. The verse opens the doors to conjuration: “Tongues untied…lungs wide…deep in power.” The tongue is a signifier equally equipped to spit venom or spew spells. “Release your spells for a weary tongue,” he advised on “Impasse.” “The split tongue thrills women, kills demons,” he alerted on “Nostrand.” Countee Cullen recounts the venom-spit on “Incident” when a Baltimorean calls his eight-year-old self a “Nigger” after “he poked out / His tongue.” In “Afro-American Fragment,” Langston Hughes detailed the threat posed by “words sad-sung / In strange un-Negro tongue.” The tongue Jordan-wags throughout I Told Bessie—tantalizing and teasing at times, but torturous at others. Take it on “Jumanji,” for example, where ELUCID raps that his “tongue burn hot metallic on the hole where dagger poke.” On “Bunny Chow,” he “bit [his] tongue in spite.” He clarified on “dutch wax”: “I speak in one tongue but like most of y’all I got five.”

Feel the possession, the possession, on “Split Tongue.” Feel “so full up with feeling”—it swells to the size of the sun. ELUCID swears “no dull axes”; he’s the “owner of all heads.” Been at it since when “the sounds were the strangest,” back “before word was formed in the beginning, / Vibrating between flesh and teeth, air escapes.” And thus, in an Adamic-styled Genesis jam, ELUCID creates language. From then on, “talking to [him]self and not listening.” He’ll jibber-jabber until the “worm still fed.” The birth of words and the death of languages.

A split tongue is a forked tongue, fraudulent and fearsome. But ELUCID doubles down on being the true and living. Christ instructed his followers: each one, teach one. “Go ye therefore, and teach all nations,” he said (Matthew 28:19 KJV). Like Biggie on “Victory,” in the commission you ask for permission to hit ’em. On “Sweet Mickey,” ELUCID decreed similarly: “Call my niggas, it’s the great commission. / Forever, for the true and living.”

Can split tongues make meaning or is it godforsaken glossolalia? Words mean things but don’t have to, ELUCID says in a bear-hug embrace of polysemous notions of art. “Sometimes the reason never mattered,” he raps on “Betamax,” unwilling to lie to us. He’ll “show [his] work,” like any assiduous student, provide “a definitive answer”—“there’s only one,” after all, “but many portals.” Why close yourself off? Lloyd Addison queried, “Where Do Words Go From Here?” And Shock G brazenly asserted, “I use a word that don’t mean nothin’, like loopted,” essentially paraphrasing Jesus Christ:

How is it then, brethren? when ye come together, every one of you hath a psalm, hath a doctrine, hath a tongue, hath a revelation, hath an interpretation. Let all things be done unto edifying.

If any man speak in an unknown tongue, let it be by two, or at the most by three, and that by course; and let one interpret. (1 Corinthians 14:26-27 KJV)

ELUCID speaks with arm outstretched and with mighty acts of judgments, and torrents flow. We listeners accept the covenant he offers up. At times, he’ll utilize circumlocution rather than direct statement, as the former is more imaginative—razzle and dazzle in the Clyde Frazier modality.

DOCUMENT xi 31.

There is no law beyond Do what thou wilt. This means that each of us stars is to move on our true orbit, as marked out by the nature of our position, the law of our growth, the impulse of our past experiences…. Each action or motion is an act of love.

—Aleister Crowley, “The Law of Thelema” (1909)

ELUCID and woods complete their triptych of duets on “Jumanji,” the title clawing back to Chris Van Allsburg’s 1981 children’s book. According to Van Allsburg, jumanji was a Zulu word meaning “many effects.” Whether that whitesplanation proves true or not, the essence of it wrecks shop like rhino stampedes (“chased the white rhino”). Kenny Segal’s gulping bass tones and cymbals crashing insistent: many effects, verily. ELUCID flashes, too—not just the “opal and gold in [his] teeth,” but the heat lightning intensity of “holy is as holy does,” the “moss and fuzz,” and the “rolling tension.” ELUCID is an exhorter, and his “words are electric,” cutting through “a babbling hacking connection.” Phone-phreaking the beat as it transforms into dissonant horns (“My connection looking spotty…”).

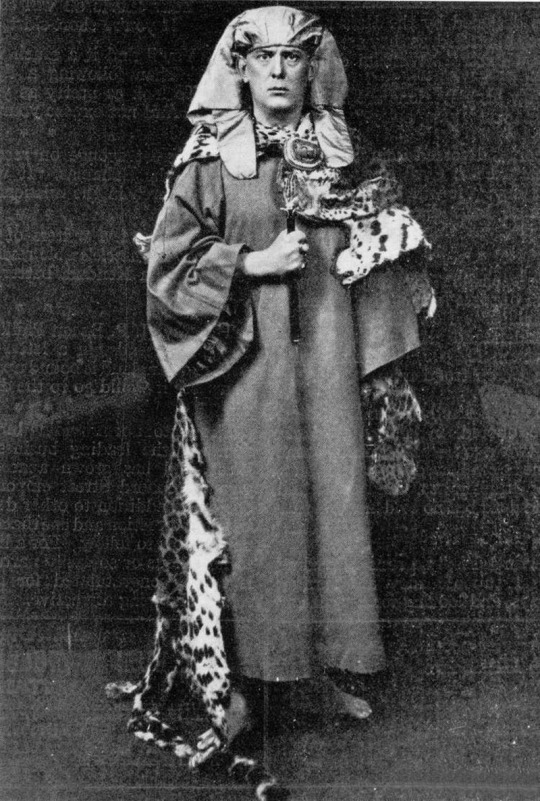

“Do what thou wilt,” ELUCID raps in the magick words of Aleister Crowley. Follow the true path: “What’s the law? I’m self-regulated. / Three-quarters water, halfway to destination.” He’s “losing focus” at the start of the verse, but his incantation regains it. He’s on his nomadic quest, “trying not to crease up [his] sneak”—noble pursuit. Such things matter; hear out woods from “Artichoke”: I used to use a toothbrush to keep my kicks white. Maintain focus: “I prioritize my week.” ELUCID’s planner is a grimoire. He doesn’t need to drape himself in a leopard pelt to prove the occult like Crowley did. While other rappers are trying to test but they’re weak like seven days (thanks, Canibus), ELUCID’s week is set and structured around intention—he’s got seven days and he’s looking to deliver 7 L’s to various devils, and he’s esoteric while doing so.

DOCUMENT xii 32.

P.U.D.G.E. brings the nostalgic noise on “Betamax” for a climactic conjuration. We’re in the spell, “spiraling on [a] square, pushing air” alongside ELUCID, “getting higher” and feeling woozy. “There’s always something to do even when I’m doing nothing,” he raps, sounding like El-P on immolation mode: Even when I say nothing it’s a beautiful use of negative space. Those “mass choirs singing [a] Gospel of Doom” have us thinking DOOM. And with our ears attuned, we get giddy at the mention of “greenbacks.” These details are significant, just as each element of ELUCID’s spells are, and it’s funny how significance make a difference. You’ll start noticing parables of three in every other inference. Armand Hammer did the money math; noted what makes a difference. ELUCID, on “Spellling” at the outset, said he’d “let the dollar circulate,” though he “never vowed allegiance.” Greenbacks? Mean stacks? He seems to be more about small bills and big communal offerings.

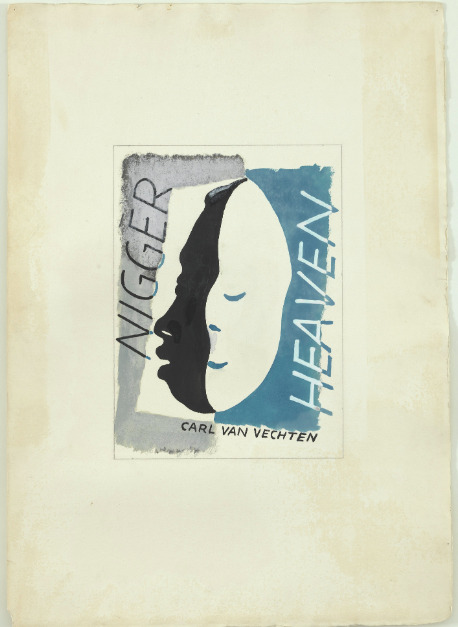

ELUCID’s cadence is full of color as verse one of “Betamax” nearly collapses in on itself only to be rebuilt in an instant. His voice modulates through several registers before the verse’s stunning close—he’s stunting. The colors are “a little more glorious, bleeding through the edges.” And we don’t really need no altars because his voice alone is lifting us higher up, higher up, higher up. He’s “done leveled-up.” Up to “nigger heaven.” He brings us back to the hard-r we heard on “Spellling.” Invoking and taking down Carl Van Vechten in one breath. Friend or foe to Black folk? Harlem wasn’t Mecca, no “nigger heaven”—there’s something beyond. Something beyond the NAACP suit-and-tie men. “Nigger heaven” was the segregated church balconies—something beyond that, too. So burn them to the ground, at least in your mental. ELUCID announces himself as “the blackest metal.” He’s been nasty; he’s been decent. Now he’s declaring: This a dead church. All he believes in is Black people believing, believing. He believes in Black people believing. And he’s “still smiling,” and “Betamax” was spit through grins, and we can hear those smile lines sinking in.

33.

Spontaneous manifestations are not always limited to noises and raps. They sometimes degenerate into veritable racket and disturbances. […] This disorder is quite often very real, though at times it is only apparent. A racket may be heard in an adjoining room… [t]hen, when one runs to investigate, everything is found to be peaceful and in order; however, leave the room and the tumult starts all over again.

—Allan Kardec, ibid.

De debbil am a liah an’ a conjurer too. Ef you doan look out, he’ll conjure you.

—“You Must Be Pure and Holy,” spiritual

…the heaven was black…

—1 Kings 18:45 KJV

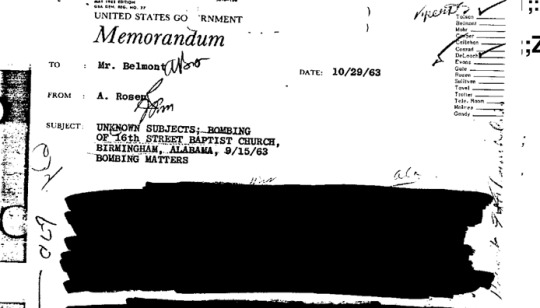

Disturbances everywhere: ELUCID can hear the racket in the adjoining rooms. The “blackest metal” doesn’t merely wink at the Norwegian church burnings of the ’90s, but summons the spirits of the four Black girls killed by the KKK in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in 1963. His references trace rackets from Vindafjord to Birmingham. In 1842, Reverend C.C. Jones wrote that “Negroes of the South” had maintained their African “paganism” and believed in “a kind of irresistible Satanic influence.” Jones was performing his racist fury. ELUCID emphasizes the performativity of any faith or anti-faith practice, terrific shouts or terror attacks: congregants speaking in tongues or spiked-and-studded lungs. Corpse paint is near-blackface. Mayhem can ensue. Even black metal shines under a funeral moon.

A racket in an adjoining room. “Blood in, blood out, / Are we not men?” ELUCID inquiries rhetorically on “Nostrand.” Sure, we’re tempted to answer: WE ARE DEVO! But the phrase also jives with Memphis sanitation strikers sloganeering in sandwich boards in 1968: I AM A MAN. And don’t disremember Sojourner Truth asking, Ain’t I a woman?

A tumult from the study. When we hear ELUCID is “blowing kisses at [his] opps in the metaverse” and listening to “Gorilla Biscuits till [his] head’ll burst” on “Sardonyx,” we can’t help but think of the hardcore band’s “Degradation” from 1989’s Start Today where they bring the motherfucking ruckus to racists: “You know you can kiss my ass before I read your zine, / There’s no good side to this white power scene.” But we should also think of the LAPD car radio transcripts during the Rodney King riots, which read, in part, “It was straight out of Gorillas in the Mist.” We should think of how Ice Cube countered with Da Lench Mob’s “Guerrillas in tha Mist”: “Fuck Grape Ape and Magilla—I’m a killa, / Magilla Gorilla ain’t a killa, / White boys swiped Godzilla from my super-nigga named King Kong.” We should think of Google’s image recognition algorithm classifying Black men as gorillas.

These rackets, these noises, these disturbances are symphonic. All culture is Black culture, ELUCID knows—inseparable, unsevered: all history, Black history—history bouncing back and forth like Schoolly D plate reverb. When you leave the room, the tumult starts all over again.

DOCUMENT xiii 34.

He was coming back into possession of himself; for the past three minutes it seemed he had been under a strange spell, possessed by a force which he hated, but which he had to obey. —Richard Wright, Native Son

ELUCID, like Bigger, is done with playing the idiot. He is of the church but not the church. I Told Bessie is a cathedral—built from the dirt up, the steeple extending from the man’s trachea. He is—as he so often reminds us—the true and living. Have no misgivings. Trust the structure. Stiffen the joists. On “Guy R. Brewer,” I Told Bessie’s denouement, he tells of an occasion where the church nearly got him—nearly merked him by means of a mint.

Bethel Gospel Tabernacle is located on Guy R. Brewer Boulevard in Jamaica Queens, which gives the song its name. The song is more like a nursery rhyme, though—a hypnotic roundelay:

Doublemint and leather. I was choking on a church mint. Starlight, starlight. In a circle outside, in a circle outside. Some hands together, some in the sky.

The circularity of the refrain rings out like the routine of 8am, 11am, and 5:30pm services: Sundays on a loop; a restless Sabbath. “Endless loops induce reflection,” ELUCID once insighted on Furtive Movements.

In Native Son, Bigger Thomas overhears gospel music emanating from a “dim-lit church,” music that “[sings] of surrender, resignation.” He has to resist the urge to give himself over to it—the music could neutralize him, leave him complacent, susceptible to untrustworthy outside influence:

Would it not have been better for him had he lived in that world the music sang of? It would have been easy to have lived in it, for it was his mother’s world, humble, contrite, believing. It had a center, a core, an axis, a heart which he needed but could never have unless he laid his head upon a pillow of humility and gave up his hope of living in the world. And he would never do that.

ELUCID’s narrative of a near-death experience is a similar repudiation of faith. He sees the light (starlight, starlight), and almost goes to it. He smells gum (Doublemint) and his mother’s leather purse. The true believers pull him back from the brink, but one would think they’d encourage his entrance into the heavens above by the grace of God. They stand “in a circle outside,” a phrase that evokes a century-old hymn. The 1927 Carter Family version, “Can the Circle Be Unbroken (By and By),” offers “a bitter home awaiting in the sky.” ELUCID won’t go to the light; he wants to plumb the depths of gritty reality. Are the “hands [that are held] together” and “in the sky” bringing him in or casting him out? Is this a celebration or a lament?

“Let the circle be unbroken,” ELUCID said on Valley of Grace. He channels Buckshot to ostensibly call the believers out on their deceptions: “Don’t front, you know I got you open.” In the moment of choking, ELUCID enters an oxygen-deprived trance. Like Bigger’s dream visions, he might hear “a distant church bell, thin, faint, but clear,” which gradually intensifies until it “clang[s] so loud that he [can] hear the iron tongue clapping against the metal sides.” When ELUCID comes to, he has the refrain in his mind, rattling around with the rocks in his head. He didn’t listen, right? Of that earlier claim, I’m unconvinced.

In his post-choke stupor, ELUCID woke up (that is, awakened and ascendant), disillusioned—free from Eldridge Cleaver’s notion of an “atmosphere of Novocain.” That might’ve been the atmosphere—be it death cult or delusional—in Bethel Gospel Tabernacle that day. Hear it in Messiah Musik’s narcotized and incomplete vocal sample, a yawning gospel leaving words unsaid. ELUCID didn’t give in, though. He saved himself.

35.

A double-minded man is unstable in all his ways.

—James 1:8 KJV

Meet me at the crossroads [Bone Thugs harmonizing voice], so you won’t be lonely. Chart the difference between loneliness and being lonely. While Robert Frost frets about a road not taken, Robert Johnson strikes a deal with the devil at the crossroads near Dockery Plantation. Faust in the Delta. The devil, that trickster, touches down in a cemetery where Johnson gained his fingerstyle. Or perhaps the devil reaches up—Night of the Living Dead style—from a grave plot, and contrives to have the Black heroics of Ben (played by Duane Jones) snuffed out (mistakenly?) by a white mob. These are the grounds on which ELUCID treads. Where things can go this way or that. Where the tongues are all forked. Where the consciousness is double. Where ELUCID lives on the third floor and Bessie lives on the first, listening to each take. With ELUCID on the mic, we’re in constant flux—breezes and rivers evahflowin’—but we’re always present at the crossroads of his conceits and conjurations.

Images:

Ponto Eshu Vira-Mundo, Vira-Mundo, and Tranca-Gira, from Robert Farris Thompson's Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy (1983) | Bill Moyers Journal, “Rosedale: The Way It Is,” 1976 (screenshot) | St. Louis Blues, dir. Dudley Murphy, 1929 (screenshot) | Run-DMC “Rock Box” music video, dir. Steve Kahn, 1984 (screenshot) | Black Herman's Secrets of Magic-mystery & Legerdemain (1925) | ”Nat Turner profesies [sic] the rebellion which will take place with the eclipse of the moon, or, ‘Nat Turner's rebellion,’” Bernarda Bryson (1934-5) | Afrika Bambaataa Presents Time Zone: Thy Will "B" Funk album cover (detail), artwork by Eric Orr (1992) | Rammellzee’s Gash-O-Lear, Mixed-media sculpture with wireless sound system, keyboard gun, pyrotechnic jawbreaker, and missile launcher. The Suzanne Geiss Company, NY (1989-98) | Hardware, Dwayne McDuffie and Denys Cowan, Milestone Media (1993) | Hardware Paraphernalia: Expandable Whip and Omni-cannon, Milestone Media (1992) | Trinidad ground-drawing, appears in Robert Farris Thompson's Flash of the Spirit (1983) | High John the Conqueror, Franz Eugen Köhler, Köhler's Medizinal-Pflanzen (1897) | Dante, Sim Sala Bim poster (date unknown) | Armand Hammer press photograph (detail), Alexander Richter | Obama Incense, Walmart Ad content | 2 Live Crew, As Clean As They Wanna Be album cover, 1989 (detail) | Female Fertility Figure (Akua'ba) 20th century - The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY | Wound of Christ, Psalter and prayer book of Bonne of Luxembourg, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters Collection, MS 69.86, fol. 331r. | 'It really takes guts to stick.' This scene occurred at Fulton St. and Nostrand Ave., in Brooklyn's Bedford-Stuyvesant section today,” World Telegram & The Sun photo by Stanley Wolfson (1964) | Redman, Dare Iz A Darkside album cover, 1994 (detail) | Gustave Doré engraving "The Vision of The Valley of The Dry Bones" (1866) | Francisco Goya, “St. Francis Borgia Helping a Dying Impenitent” (1788) | “Adam naming the animals.” Etching by G. Scotin and J. Cole after H. Gravelot and J.B. Chatelain (1743) | Aleister Crowley, publicity material for The Rites of Eleusis (1910 ) | E. McKnight Kauffer, dust jacket for Nigger Heaven, Illustration from Carl van Vechten's novel (1931) | FBI document excerpt (FOIA), Birmingham, Alabama, Sixteenth Street Baptist Church (BAPBOMB) | Bethel Gospel Tabernacle, historic photograph (source unknown) | Mande-influenced Akan cotton multistrip cloths of the nineteenth century, from Robert Farris Thompson's Flash of the Spirit (1983)

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

blindone- HER 21

sole- Apocalyiptica 8 feat. Gun Dolo

Tachichi & Moves- Lobstermania Intro (prod. Rhek)

Dillon & H2O- Outlaws

fermented reptile- the law

Dope KNife- Inereyes (prod. Paul Abdul)

King Syze- Real Shit (feat. Akrobatik & John Jiggs)

Shyheim- On And On (feat. June Luva & Milk D)

Oscar Goldman- Hurts (feat. Casey Chisholm and Myles Bullen)

Godfather Don- Assuming Dat

Chief and TheDoomsdayDevice- Gangstalking

SPAN PHLY- SpyKidz3D featuring Judgement of TSOI

ambition jay bizzy ghettosocks thesis sahib & ginzuintriplicate- the mackay bridge is over(feat.aquakultre sean one & tachichi)

Parish PMD Smith- Gimme The Mic (feat. Ace Brav & RJ da Realst)

rob crooks and bazooka joe- infinite haymaker (ft.timbuktu)

Tay Da Crown- Over the Edge (feat. Vell & ATM The Professional)

Uncommon Nasa- New York Telephone (w, Yesh)

kool keith & mr. sche- ride & mug

rob sonic- mink

Self Jupiter- Before I Kill the Beat

Masai Bey- Aural Tradition

kno x sadistik- mothlight feat.natti

Awkward- Mega Dolphins with Megabusive

Thorts & Unsung- Molasses feat.Chris Conde

Teddy Faley- An Incomplete List

serengeti- caucs remix ft. mf_grimm and juice

more or les chokeules timbuktu jesse dangerously and wordburglar- all day

Canibus & Phoenix Orion- Sit Yo Hot Ass Down Ft. K-Solo & Michelle Regnier Mezzo Soprano

Nine- tha product (wit u-neek)

2mex feat sully and k bourne- yacht rocking

Ayentee- New Currency

labtekwon- i am here (12 inch version)

Jurassic 5- A Day at the Races (ft. Big Daddy Kane & Percee P)

Tank Gawd (Moka Only & Kutmasta Kurt)- Microphone Deflection

Qwel & Maker- En Garde Feat Qwazaar

Gel Roc- Here I Am Ft. Ceschi

Menes the Pharaoh Sea- Achildrensbookofdemons (feat. Sea_Swordz & 7rinth)

Andrew Mbaruk & Eric Bennett- Bored, Dining With Lord Byron

Witness- Lower Case

Jedi Mind Tricks- In the Coldness of a Dream

Freddie Gibbs - Life Of A G (ft. Z-Ro)

numb- Save A Friend

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Yo you ever heard of labtekwon

No never heard of him. Which album or song should I check out first ?

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

inMASSIVE ROTATION / THE SOUL LIBERATOR : RESOLVE / EVOLVE 6.17.2017 Various Artists | 1. All Africa - #ZaraMcFarlane | 2. Sister Soul ft. #SabrinaMalheiros | 3. Samba Para Florence ft. Heidi Vogel | 4. Don't Let The Sun Go Down (4Hero Dub) - Sean Khan | 5. Le temps est bon (Remastered) - Degiheugi | 6. Mystery Of Love - #BenCenac | 7. Turning Tides Feat. Woolfy - Giving Me Everything | 8. Black Rose - #SpoekMathambo | 9. Brighter Day - Rising Sun | 10. The Creation - #SeanKahn | 11. My Friends, Or Strangers? - #MFDoom, Sade, Seanh | 12. Black On Purpose. #BOP - #Labtekwon | 13. Can Be feat. Tatu Vision - #AmaniJade | 15. Good Morning Amerikkka feat. Cotton - #HOBOThe Great 16. Hail The Prophet (theNorm) - BARRIO | 17. Victim Of Babylon - Admiral Tibet | 18. None Stop Rocking - #SugarMinott [end] CENisbett\ ESH VANTERPOOL -IMR in MASASIVE | THE SOUL LIBERATOR. Thank you for tuning in. (at New York, New York)

#amanijade#sugarminott#bop#sabrinamalheiros#hobothe#labtekwon#mfdoom#seankahn#bencenac#zaramcfarlane#spoekmathambo

0 notes

Photo

MBL FLAVA vol.16!9/22(sun)開催! ㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤ 今回は15:00〜22:00のデイイベスペシャル🎉キッズダンサーも出演します! ㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤ 9/22(日)にMフレが開催となります♬ 今回はゲストダンサーにCoolなFashion Styleで全身からNewjackswingを体現する[TAiSHI] @taishi_newfast と、TAiSHIくん率いる[No Limit]が出演! そして、POP UP STOREには90's HipHopをモチーフにイラストレーターとして活動する[RISA]さん @risaco827 が、Tシャツ等作品を出店してくれます🎉 . また、今回も定番となったSoul Kitchen YAMADAのカレーブースもあります! . ディスカウント入場枠もありますので、ぜひご連絡下さい。 . MBL一同お待ちしてます🙇♂️ . 〔MBL FLAVA vol.16〕 9/22 sun. 15:00-22:00 . <DJ> MBL DJ’s . <DANCER> TAiSHI No Limit . <POP UP STORE> RISA . <FOOD> Soul Kitchen YAMADA . <ENTRANCE> MEN ¥2,000/1D WOWAN ¥1,500/1D . <PLACE> CLUB FLAVA @町田 東京都町田市原町田2-7-3 . #mbl #djlife #local #love #Mフレ #町田 #flava #90s #blackmusic #party #hiphop #rnb #soul #funk #newjackswing #scratch #nightclub #tequilla #alchol #goldenera #dj #vinyl #12inch #djmix #labtekwon https://www.instagram.com/p/B2fk8s6FU_y/?igshid=14wq42rrqiioi

#mbl#djlife#local#love#mフレ#町田#flava#90s#blackmusic#party#hiphop#rnb#soul#funk#newjackswing#scratch#nightclub#tequilla#alchol#goldenera#dj#vinyl#12inch#djmix#labtekwon

0 notes

Audio

https://soundcloud.com/mrdaveyd/hkr-the-epic-labtekwon-intv-pt2-the-gentrification-of-hip-hop

0 notes