Text

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

edwad what are some books you would recommend to someone who hasn’t read a book about communism besides state & revolution

i made this thing several years ago and i guess i would still stand by most of it, but it's probably a bit demanding for a newer reader of this stuff and very much oriented around marxs capital rather than communism generally etc. the links are still handy (if they still work, idk lmfao) and regardless id probably recommend heinrich's intro along with chambers' no such thing as the economy book. i think that gives you a pretty good baseline as far as marx-interpretation goes, and maybe it could be dialed up another notch by tacking on WCR's marxs inferno (although i don't love the case he makes for republicanism even if it's probably fine as a marxological claim).

depending on how recently you've read s&r, i think following it up with pashukanis' general theory can be really productive (esp when read alongside foucault's discipline & punish) because it is largely in dialogue with lenin and leninist conceptions via the development of marxs categories in capital. if you're feeling capital-averse (understandable, but id encourage you to join my reading group this fall!) then the heinrich can come in handy as a crutch for some of this, perhaps alongside rubin's essays (pashukanis' soviet contemporary).

if you're looking for something else more specific or general or whatever let me know and i can try to help

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

I do feel a lot of tension around like, wanting to do more critical legal studies/critique of political economy writing and reading, but the bulk of my background has been in the history of political thought and so I do feel like I sometimes lapse a bit too much into analyzing what specific guys thought. Which is interesting but not really useful - part of my broader uncertainty about the ultimate utility of political theory

This was a tension I felt really strongly writing my Master's thesis, where I wanted to kind of analyze Marx's political theory in order to ground what a communist ethics could look like - and I had fun writing and researching for it, I think a lot of the arguments are good, but I don't know how successful that particular object was. like, I don't want to be doing Marxology. but sometimes it feels necessary in order to like dispel prevailing biases or presuppositions, or to establish that like these ideas are emerging as part of a specific intellectual history? I dunno, it's a weird tension

At the same time I feel like I was doing a lot of my strongest/most interesting thinking in that period from like 2017-2019 even if it wasn't as robust as I wanted, and then law school happened and that's a place where thought goes to die. Definitely wrote some things I found interesting on occasion, but it often felt kneecapped by the constraints of legal writing expectations and legalist priorities

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Enrique Dussel, The Theological Metaphors of Marx - trans. Camilo Pérez-Bustillo, foreword Eduardo Mendieta, Duke University Press, April 2024

Enrique Dussel, The Theological Metaphors of Marx – trans. Camilo Pérez-Bustillo, foreword Eduardo Mendieta, Duke University Press, April 2024 the introduction is open access here In The Theological Metaphors of Marx, Enrique Dussel provides a groundbreaking combination of Marxology, theology, and ethical theory. Dussel shows that Marx unveils the theology of capitalism in his critique of…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Chapter 24 of Volume I

and the first chapter of Volume II are clearly linked to each other thematically or chronologically, in the manuscripts.

1 note

·

View note

Text

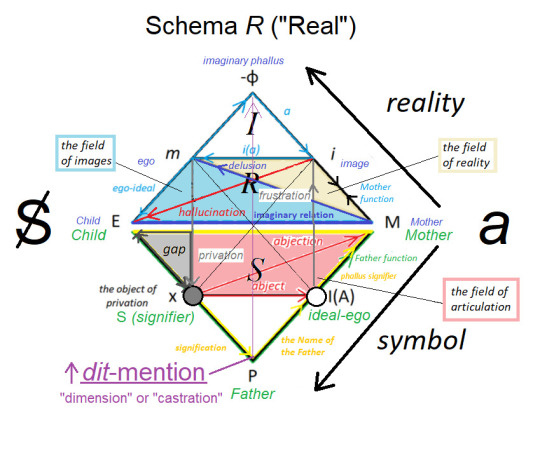

On the Interpretation of an Annotated Version of Lacan's Schema R

The Lozenge of the Mathème for Fantasy (1):

The Vel in the Lozenge

The diamond-shaped lozenge character/symbol found in Lacan's mathème for fantasy is clearly not the same thing as schema R or a semiosic square. This is partially because the lozenge's characteristic ability is to elide participating in either a symbolization or a semiosic square, because these are structures that intrinsically incorporate an arrangement of four given terms into two distinct contraries. The lozenge, on the other hand, while it does possess for itself two contraries, just like a semiosic square has, it also only (apparently) supports two terms, not four. So, while the ultimate agenda is to integrate the Oedipal+preOedipal+Real (S+I+R) quadrangle (schema R) into what Lacan refers to as the vel in his eleventh seminar, they are not genuinely the same structure. The annotations would have the vel moving from E to M on schema R by way of the object of privation x, the symbolic father P, and the ideal-ego I(A). This is not what is going on with a lozenge at all. So, there is either a dialectical progression required to reach the point where a lozenge-structure can modify the schema R so that a direct vel movement is possible whenever signification may occur, or these speculations and suspicions turn out to be incorrect, and the lozenge-structure should be kept separate from any quadrangular semiosic schemas for the rest of human history.

In any case, here is the (my) annotated version:

The Lozenge of the Mathème for Fantasy (2):

The Hegelian Lure, and the “Master-Servant Dialectic” in the Oedipal Square/Schema R

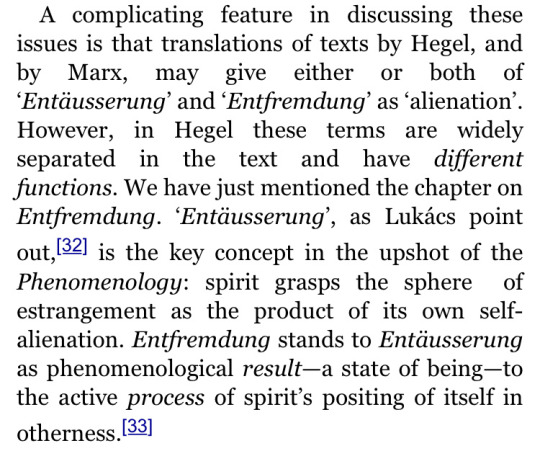

In an article titled “Hegel’s Master-Slave Dialectic and a Myth of Marxology”, written by Chris Arthur, and published in the New Left Review for their November-December 1983 issue (this is an article that I read online a few years ago that profoundly influenced me), there was a discussion on the appropriation of Hegel's philosophy by both Karl Marx himself versus the French Marxists of the 20th century, the latter citing Alexandre Kojève as their primary influence: figures such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Jean Hyppolite, and Hérbert Marcuse.

At stake was the definition and use of the French word aliénation in French Marxist philosophy, since it could be translated for two different words in German, words which were used by the philosophers Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Karl Marx. These two words were, namely, Entäußerung (“en-toy-sare-oong”, alienation) and Entfremdung (“ent-frem-doong”; estrangement, or alienation), respectively.

Hegel's Entäusserung was used more in reference to a spiritual (pertaining to Spirit) or essential (pertaining to essence) connotation of the meaning of the word "alienation", whereas the word Entfremdung connoted through "estrangement”, for Marx more specifically, something maybe closer to the English word "separation", i.e., the proletariat's alienation from the product of his/her/their labor, indicating that the worker has the product of his labor taken away from him once he is finished making it. This is because it is intended, by the capitalist who owns the business, to be sold to someone else (obviously). Marx's point in developing this idea of alienation wasn't exactly that the finished product ought to belong to the worker instead (as I once foolishly misunderstood to a large degree), but rather that the financial math involved in capitalist business operations ends up cheating the worker of a full compensation for what he/she/they did to produce wealth for their employer that day. Alienation, in Marxian economics, thereby implemented a more spiritual or abstract register of Hegel's philosophy in this manner, which it always only ever was; mostly, this was in the context of Marx's polemic against a sort of poetic injustice at the societal level, and not a serious call for any violent destruction of the established order.

But wait… Is Marx ever really talking about political economy itself when he writes about the workers who are forced to participate in it, (that is, if they want food to eat and a place to sleep)? Was his writing just an example of literary self-stylization through polemic? Or is labor itself not truly productive, but rather something fundamentally cognitive and philosophical by means of the historical mechanisms internal to thought itself? And why is it important that French intellectuals of the 20th century were claiming that these connections now established between Marx and Hegel ought to be attributed to the teachings of Alexandre Kojève, instead of getting de-bunked altogether?

This tendency in French Marxism, broadly speaking, and according to Chris Arthur, is significant because Alexandre Kojève is practically the father of French existentialism, French psychoanalysis, French political philosophy, and 20th century French Marxism; the study of any philosophy of history or Heidegger's ontology in France, as well, could never do without his influence either. As a result, even French president Emmanuel Macron can be presumed to have a familiarity with the prestige of the French Hegelian tradition. Alexandre Kojève was a profound influence on Jacques Lacan as well, serving as Lacan's "master-signifier". He really is the most influential thinker, teacher, and politician of all time, even though he is not by any means the most essential one.

However, this confusion about so-called "alienation" persisted in Western European philosophy for quite a long time as a result of his teaching. But… what if Kojève had anticipated, prior to the consequences of this confusion about "alienation", what he was doing with the eventual historical effects of his teaching? His calculated dissemination of Hegel’s and Marx’s philosophical wisdom is rather Christ-like for that reason. (But I'll discuss this way further down in the post.)

Back to main topic: The vel in Jacques Lacan's diamond-shaped lozenge is located at the bottom-half of the lozenge. This part of it, a V-shaped movement from left to right, is also referred to by Lacan as "the Hegelian lure". Why?

So, the Hegelian lure is… what?

“Spirit grasps the sphere of estrangement as the product of its own self-alienation.” This is the essential thrust of fantasy in general, even though it is an activity that remains largely unconscious. And that very fact is because of its interactions with what is non-conscious.

This interplay which constitutes the thrust of fantasy is between:

[1] the formations of the unconscious,

[2] unconscious mechanisms (e.g. natural metaphor), and

[3] non-conscious, or undiscovered, scientific/factual knowledge.

This thrust of fantasy, then, is a conglomerate formation facing towards Hegel's idea of Absolute Knowing. There is a gap between the present-day, or present-moment, and the final end of knowledge itself, which marks the location of a present-moment's abstract finish-line. This situation bears stark similarities to Kant's antinomies of Pure Reason, but as Hegel famously criticizes, Kant's idea of the concept is too flimsy, because a concept is something which ought to be grasped properly if it is to be the attainment of the thing itself. In this vein, what I personally like to think of as the noumenal justice of imaginational (visual) logic relies too heavily on the metaphysical escapability of the Kantian thing-in-itself. This innate slipperiness, which generally characterizes Kant's understanding of objects, avoids Hegel's notion of Absolute Knowing for the most part, deferring instead to its respectively absent uncaused cause, rather than making itself graspable by way of self-knowing.

The relationship to knowledge on the part of the Lacanian (or psychoanalytic) subject is one which must necessarily pass through the dialectics of need, demand, and desire in order to be capable of "producing" a signifying chain. This is distinctly marked by the appearance of a', which shows up on the Schema L. (You can find a pretty good explanation of that here, although I would like to take a closer look at it and emphasize the emergence of this a' as the very condition to which desire itself is subjected.)

In any case, this conception of "desire itself" as something subjected to the a' is analogous to a thematic element of the mathème for fantasy found in Chris Arthur's exposition of the philosophical relationship between Marx and Hegel. So, what does Marx say, potentially pertaining to fantasy, and alluding to Hegel, according to Chris Arthur?

(“Bildungsroman”, according to Oxford Languages/Google Search Engine, is “a novel dealing with one person's formative years or spiritual education.”)

“Abstract mental labor” as the “labor of spirit” is the final objective of fantasy in general, and this is what Lacan's mathème expresses. On the annotated version of Schema R, however, there is a part of the vel (if this schema is indeed mimicking the lozenge) which is a gap in both figurative and literal space, there to denote how the dialectic of desire must play out before a linear process of signification may ever occur in the first place. To get to this abstract mental labor, then, reality must become an object, one which is both ordered and organized by the trapezoid-symbolizations which are the projective surfaces of psychoses: poiesis/delusion, genesis/hallucination, and sinthome/elision. This is what the convoluted-looking annotation basically signifies.

The Lozenge of the Mathème for Fantasy (3):

The Gap between the Split-Subject and the Object of Privation

The split-subject is produced by a variable stimulus Δ interacting with the variables S and S’, illustrated above on Graph I of the graph of desire, which is also known as the “button-tie” or “quilting-point” (point de capiton). This interaction between the variables is called metonymic sliding (glissement), or slippage. Two vertices of the pre-Oedipal triangle (i and m) may then interact with this metonymic slippage in tandem with its already-produced product, the split-subject, $. To re-iterate the basics, the Other, A, is a destination at which the subject never arrives, however (it is a place that exists, but not a space where one may be). Rather, the approach is one of anticipation for what Lacan repeatedly called “the treasure trove of signifiers”, the Other, which I mistook (for a long time) for a lexicon. Looking at the schema for poiesis will show, however, that there is also the sonic resonance of the imaginary phallus, -φ, which vibrates all around the image of the object i(a), objet petit a.

Poiesis here is the failure of frustration to relate to castration in a way that germinates the very possibility of fantasy. The subject’s approach to a relationship with demand is knocked off course by a metonymic slippage which flees from the Other in the form of the Voice, and this consequent alienation causes the subject to “fall under” the phallic function of the mother's beyond (Jouissance → Castration) and land at the locus of the signified of the Other. It does not reach the upper level of the complete graph of desire because it was not launched up by desire, d, with enough thrust. This is Hegel and Marx’s Entfremdung, which was described above. The estrangement of spirit finds its home in self-alienation, and picks up the Signifier as the substitution for its lost relationship to desire. This is a properly-constituted instance of cognition, which in addition to the signified also picks up more of -φ’s sonic resonances on the way down to I(A), and arms itself with the ego (m, “le moi”). The ideal-ego, I(A), is a space where one may arrive at occasionally, but the resonances of the imaginary phallus which are functionally reflected (reflection here functions as a metaphor for re-semiotization, since the vectors $→A and s(A)→I(A) are not moving in the same direction) in i(a) continuously interfere with the apperception of any final tension. This is to say that the graph of desire is best understood as a structure that is constantly pulsing with the colorful, multiplicitous vibrations of plucked strings.

Poiesis corresponds to the elementary cell, Graph II of the graph of desire, as a projective surface of psychosis, the one which fosters the (psychotic) structure of delusion. It is something that you peel off of it, like a sticker, or an article of clothing, a cloak for a desire-device whose existence would have otherwise gone undetected. But what it also uncovered for us above was the falling-under of the subject to a place below the phallic function at the signified of the Other s(A), which is a place both added to and subtracted from by the sonic resonances of the imaginary phallus in an Icarus-like enactment of Entfremdung.

What emerges for the subject from this falling-under, in conjunction with both poietic uncovering and Entfremdung, is the object of privation, which I denote as x. This kind of object is of a symbolic lack. But this observation of the poietic uncovering of a desire-device (Graph II of the graph of desire) as the foundation for the approach to phenomenological method is both schematically and architectonically deceptive. However, The relationship between the subject and the object of privation is certainly an exceptional one, and poiesis may approach this object from the greatest distance possible, as a trapezoidal-symbolization, and as a projective surface without a symbolic object. The aforementioned deception of this approach lies in how the other two trapezoidal-symbolizations have identical capacities to uncover similar dimensional objects for the subject (i.e., objects of frustration and castration), therefore, they are neither objectively nor metaphysically outranked by the primal cloak of poiesis.

Beginning with poiesis makes the exposition of the gap between $ and x less difficult to explain, though. This is because for the cloak, or projective surface, of sinthome, the object of privation moves right into the place of the signified of the Other once the dialectic of demand has recapitulated, whereat the subject may readily collect it (x) upon the occurrence of its Entfremdung after having fallen under the phallic function; the subject then may bring it (x) back to where it formerly just was, to the space of the ideal-ego.

This process of re-linking the signified of the Other to the ideal-ego without interference from the resonances of the imaginary phallus by means of the object of privation is called the abject. Counter-resonances from the symbolic father at P on the Oedipal square vibrate in tandem with the momentum of the ego (m), causing elisions of the resonances of the imaginary phallus by de-longitudinalizing its sound waves, sending them off in a transverse direction. If sound waves are always physically longitudinal, and this fact is in tandem with the imaginary phallus because these waves may only follow the law, then the sound waves which resonate from P are longitudinal as well, because they may only stop the law from being followed. The relationship between P and m is an odd one that can therefore only be uncovered by putting on the cloak of sinthome. The unconscious mechanism at work in this cloak of sinthome placed over Graph II is reification. The subject may get sucked over to the left side of the graph by the resonances of P in tandem with m, and identify directly with x in such a way that the ideal-ego and the subject take on a relationship to one another similar to that of the abject. This close-knit triangulation leaves the Other in a state of being held at the greatest possible distance, however; this is to the extent that the real father must have some rugged object for its substitute within the treasure-trove of signifiers (A). In this way, as a distracting ploy to the subject, it is also the key to the lock, which allows for the object of privation to invade the subject’s rightful place.

The final cloak, then, is the cloak of genesis, whereby the subject substitutes itself for the object of privation directly in order to displace itself, and pre-configures the left side of Graph II as wholly imaginary. Thereby, the subject may be returned to the Father most purely at I(A), and the signified may also be returned rightfully to the treasure-trove of the Other at A, both of these functions occurring mutually without disturbing one another. This is also the foundation for the projective surface of hallucination, however, a sort of antagonistic undoing of the phenomenology that the cloaks, up until now, gave a semblance of.

In conclusion, the gap (béance) between the split-subject and the object of privation is a three-sided relationship between two terms: E-x, E’-x, and $-x. This is illustrated by the button-tie, Graph I, and results in the formation of a lozenge-structure. You can also find it on the symbolic (lower) triangle of the annotated schema R, adjacent to E. Thus, the lozenge is derived from a semiosic square, that of schema R, after all, rather than the synchrony and diachrony at odds with one another which merely form a semblance of the real through their empty resonance. (Whether or not this is ontological or metaphysical is decidedly beyond the scope of the topic.)

Alexandre Kojève and Jacques Lacan's Christ-Like Riddle for Human History

So: back to the speculation about Alexandre Kojève, and his Christ-like plan for the fate of our species’ philosophical institutions: did he intentionally plant seeds which might give the answer to the Lacanian problematic of the “Hegelian lure”, and furthermore in advance of the completion of the psychoanalytic sphere (in 20th century France)? The labor which is grasped as the “essence of man” that Marx alluded to, and which Kojève emphasized in his lecture, is clearly a philosophical labor, and not a materially productive labor. This kind of labor is ultimately far more time-consuming, and the relation of the mathème for fantasy to schema R is one of philosophical (maybe Kantian?) transcendence. The mathème itself represents what our human species may finally aspire to, if it finds the capacity, the excellence, and the strength to do so. And this process is fundamentally historical, by a (Kantian) form of necessity.

The Christ-like riddle for human history mentioned earlier, then, is about the ambiguity and the eternal struggle happening between [a.] the master-signifier, S1 and [b.] the Name(s) of the Father, S(A), both of which serve a master's discourse, and function to prohibit the mother as a fundamental consequence of language-acquisition (schema L). What is so Christ-like about it is that this dual antagonism appears to have been left behind by the two men, Kojève and Lacan, very intentionally. Even though Chris Arthur seemingly criticizes the French intellectuals in his article, those who make false claims because they are too broad about the link between Marx and Hegel according to Kojève, Arthur doesn't seem completely indignant about it if he is also undoubtedly aware of Lacanian psychoanalysis. He expertly enacts the cyclical process of the rotations of the four discourses in a way that doesn't escape one's attention. He is a very cerebral and witty guy, in this regard.

— (5/10/2022)

#lacanian psychoanalysis#drawings#philosophy#philosphy of history#politics#french hegelianism#Emmanuel Macron#French philosophy#Karl Marx#Hegel#Jacques Lacan#alexandre kojeve

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The existence of Marxology, where people attempt to divine out the exact meaning of Capital and others based on interpretation of every sentence of the text and differing interpretations of the same sentences can lead to splits and infighting is, frankly, fucking pathetic. Marx was just A Guy. He was not divinely inspired to find out absolut historical truth, and we don't have to treat him like we do the words of a prophet. It's just weird.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Annoyed that MLs ignore Lenin's marxology and attempt at parsing hegel like in general everything interesting Lenin wrote is confined to drafts and manuscripts

1 note

·

View note

Text

Translating "Aufhebung" to "Abolish" was the worst of anglo marxology's many mistakes

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

if i used my time learning abt art to get into marxology instead i couldve been a succesful podcaster already

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

(copied over from a twitter thread)

I read The Housing Monster by “prole.info” There's a lot good in it: it's the clearest and most directly grounded explanations of value-form theory I've read (which it does by skipping the pedantic Marxology and avoiding unnecessary jargon). The later sections, which move away from production and look at land and rent, are really great as well.

It's got some sections that deal with gender in various ways, but they feel a little limited (not just because of some occasionally outdated language re: trans & gay stuff). Like, it presents the broad strokes of a materialist-feminist analysis of housework, and the harm of 'macho bullshit' at work, and correctly situates sex work with other kinds of work, but doesn't trace how gender itself emerges and how it's enforced.

It's a shame because it goes so far to clarify other fetishised relationships like wage labour, capital, rent etc.! Like it's not that it says anything wrong, but it'd be easy to go away thinking that 'men' and 'women' are natural categories, even if the relationships between were changed by capitalism.

It's also got a solid description of the Soviet Union as a developing capitalist state (similar to Aufheben's very very long series, which isn't surprising since they cite Aufheben elsewhere), and the limitations of unions and the many ways that class struggle can be co-opted.

I think it falls down pretty hard on race - it acknowledges that capitalism is racialised but mostly sees race as a division between workers created by atomisation, the status given to different kinds of work, the image of community etc. which isn't wrong but neglects how like, antiblackness, antisemitism etc. have their own particular logic and independent functioning, which can't just be reduced to a consequence of the division between un/skilled labour etc. Other writing in the same tradition does better but like only nerds read Endnotes (alas).

It's esp. uncomfortable in the last chapter, which brushes over anti-racist movements as part of a marketplace of philosophies and movements which fail to correctly grasp the core class struggle. It's frustratingly dismissive and seems at odds with the care taken elsewhere.

(The final chapter is the weakest in general - it's on a much stronger foot in its critical analysis of the existing world than its pretty vague call to arms. Which is a common problem and one I certainly haven't solved.)

I still think it's worth reading, especially if a lot of this Marxian stuff seems obtuse, but I wish I could give a less qualified recommendation.

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

This movie was brought to my attention by fellow Marx animation maven Ira Dolnick. With just the title and the name of the filmmaker, I could find out very little about it and the cartoon was not available online. I contacted Mikael Uhlin, Swedish national and founder of the website Marxology, who was able to email Lillieborg and as of last week, the film is available on Youtube! This was a short subject made for Swedish television Channel 2 in 1978, based on a book of poetry. Other comedians caricatured include Ben Turpin, Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, and Laurel & Hardy.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

i can't tell to what extent you're joking in your reply to compulsory labor question (because of what you say after the "yes"). i was asking a serious marxological question, did he actually? did he want communist means-testing?

part of the reason i gave you a short joke answer is because i was asked a similar series of questions last month and it turned into a multi-day thing where my ask box was flooded with the most annoying people that marxism has ever generated. i don't really feel like doing that again, but if you filter my posts by messages and look thru december you'll probably find something like what you're looking for. the tl;dr is that marx was never consistent on anything at all in his entire stupid life so trying to pose a "yes or no" question about him is basically self-defeating

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Nature of Marx’s Things is a major rethinking of the Marxian tradition, one based not on fixed things but on the inextricable interrelation between the material world and our language for it. Lezra traces to Marx’s earliest writings a subterranean, Lucretian practice that he calls necrophilological translation that continues to haunt Marx’s inheritors. This Lucretian strain, requiring that we think materiality in non-self-evident ways, as dynamic, aleatory, and always marked by its relation to language, raises central questions about ontology, political economy, and reading. “Lezra,” writes Vittorio Morfino in his preface, “transfers all of the power of the Althusserian encounter into his conception of translation.” Lezra’s expansive understanding of translation covers practices that put different natural and national languages into relation, often across periods, but also practices or mechanisms internal to each language. Obscured by later critical attention to the contradictory lexicons—of fetishism and of chrematistics—that Capital uses to describe how value accrues to commodities, and by the dialectical approach that’s framed Marx’s work since Engels sought to marry it to the natural philosophy of his time, necrophilological translation has a troubling, definitive influence in Marx’s thought and in his wake. It entails a radical revision of what counts as translation, and wholly new ways of imagining what an object is, of what counts as matter, value, sovereignty, mediation, and even number. In On the Nature of Marx’s Things a materialism “of the encounter,” as recent criticism in the vein of the late Althusser calls it, encounters Marxological value-form theory, post-Schmittian divisible sovereignty, object-oriented-ontologies and the critique of correlationism, and philosophies of translation and untranslatability in debt to Quine, Cassin, and Derrida. The inheritors of the problems with which Marx grapples range from Spinoza’s marranismo, through Melville’s Bartleby, through the development of a previously unexplored Freudian political theology shaped by the revolutionary traditions of Schiller and Verdi, through Adorno’s exilic antihumanism against Said’s cosmopolitan humanism, through today’s new materialisms. Ultimately, necrophilology draws the story of capital’s capture of difference away from the story of capital’s production of subjectivity. It affords concepts and procedures for dismantling the system of objects on which neoliberal capitalism stands: concrete, this-wordly things like commodities, but also such “objects” as debt traps, austerity programs, the marketization of risk; ideologies; the pedagogical, professional, legal, even familial institutions that produce and reproduce inequities today.

0 notes

Link

The Marx/Schickler Family first lived in an apartment at 4649 Calumet Avenue where the city directories find them ensconed in 1910 and 1911 but in late 1912 the family moved to a three-storey brownstone house at 4512 Grand Boulevard (now 4521 King Dr). In The Marx Bros. Scrapbook by Groucho and Richard Anobile, Groucho says: "We lived in Chicago for twelve years. I saw Ty Cobb play baseball many a day at White Sox Park. We lived right near there. We bought a house for $ 25,000.00. We paid a thousand down and owed the rest."

Photos by Xaviar Quintana

#marx brothers#Groucho Marx#harpo marx#Zeppo Marx#Gummo Marx#Chicago#chicago his#Chicago white sox#Ty Cobb#chicago southside#comedy#comedy history

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

tumblr marxology is the most brutal circle of hell

6 notes

·

View notes