#my favourite of these is queer temporality

Text

sometimes you’ll think about queer existence as it pertains to storytelling and mythologies and you just have to sit down for a bit because it’s so cool and so endlessly deep and you’ll never hit an end to where queerness is embedded into the core of who we are

#queer stuff#queer mythology#queer culture#my favourite of these is queer temporality#whenever i think about queer temporality my whole damn body tingles#also today: genderqueer-klinger pointed out how queer euphemisms are in several languages connected to flight (faires#fairies* birds etc)#here we are a bunch of animals and we build stories and we call one part of these stories queerness#and it's so so so good and Cool

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

top 5 books you've ever read (no genre distinction)

LOVE this question. spent a whole day stewing over it. i'm afraid i'm experiencing heavy recency bias here and there will also have to be some honourable mentions. but let's go (in no particular order)

brokeback mountain by annie proulx. now. when i tell you i could talk about this story (later published as its own book, originally published in the new yorker sans prologue (which was deliberate, thank you, wikipedia, i have Been to the Archives and i Know) and then published in the collection close range) for literal hours, i mean it. i wrote a prize-winning essay on it during my masters, examining its drafting process and what that process itself implies about queer temporality and the value of the unsaid against the great big american myths of rural frontier masculinity that don't match up to a modern world (or any world at all). if anyone wants a more detailed post on this i would Love to talk about it more. but for now, please go read this book. it's utterly transformative and maybe the best queer work of fiction i've ever read.

house of leaves by mark z. danielewski. EXTREMELY different vibe from proulx, oh boy. this is where i out myself as a postmodernist with a great enthusiasm for the big 'bros' of the scene - pynchon, delillo, later franzen and foster wallace. house of leaves is really a post-postmodern work, which is my favourite sort (i suppose a recent example would be no one is talking about this by patricia lockwood) in that its examination of literary artifice and the unreality of the world leads not towards ironic futility but to something even approaching optimism, ie. the new sincerity. this is not to say that house of leaves is a feel good work, oh no. oh boy. it's absolutely bonkers and utterly compelling, and you get a lot of weird looks when you have to use your phone camera as a mirror to understand bits of it on a packed flight into jfk. it combines two of my favourite things: postmodernism and horror. it's perfect.

in the dream house by carmen maria machado. i wrote my master's dissertation on this and it's utterly beautiful. it interacts with fiction and genre in a transformative way — and i use that in the OTW sense, the henry jenkins participatory culture sense, yes i did essentially write my masters dissertation about fanfic. machado's memoir is so interesting as a work of resistance to and celebration of genre — the media that has erased her as a queer woman suffering domestic violence, the media that she loves.

slaughterhouse five by kurt vonnegut. yes, there had to be another postmodernist on this list. i've read a lot of his work now and it's always brilliant, but this is his most famous for a reason. engages with war, temporality, and nihilism in such a moving and memorable way. there's a reason a vonnegut reference (so it goes) creeps into everything i write

lolita by vladimir nabokov. yeah, i'm including the Discourse Book. please feel free to unfollow me. a lot of eloquent writing already exists out there on why this novel is genius, so i'll settle on saying as a technical achievement it's utterly insurmountable, as an indictment of american consumer culture it's unparalleled, and as a moral object it makes a lot of people very uncomfortable, which means it's working.

you have no idea how close i was to putting infinite jest on this list. but you asked for the best books i've ever read, not my favourites... and infinite jest is ridiculously flawed. so.

honourable mentions go to: the grapes of wrath (john steinbeck), nevada (imogen binnie), the silmarillion (tolkien), and catch 22 (joseph heller).

thank you for the ask!

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

A selection of topics from papers I wrote

As inspired by the brilliant @dove-da-birb, I thought I might share some of the topics of a few papers and projects I wrote over the course of my degree. That is, my first degree, since there's a high chance I'll get a masters or other certification in the future and write more. Or I may just write research papers for fun! Who knows? Below are the titles and small abstracts of some of my favourites, most of which centre around a couple common themes (as you'll see).

ACTUALLY, let's make this a little game. One of these papers I have NOT actually written... yet. :) Which do you think it is?

Linguistics

Lesbian Gender Presentation

A sociolinguistic analysis of how lesbian genders (specifically butch and femme) are formed through physical, social, and linguistic means in a primarily North American context. (Yes, this was a linguistics project, not a gender studies project! I actually made a Tumblr as the final presentation, but I'm, uh, not going to share that publically...)

The Sociolinguistic Power of Names and Naming Practices

A consideration of the social, cultural, linguistic, and political power of names. What - and how - people are named reveals various aspects of one's identity, relationships, and place in society. Using an intercultural and diachronic perspective across various in-person and online communities, the significance of naming practices is explored.

Gender Studies

Madness and Transness : Medicalization and Stigma of Non-Normative Gender in Psychiatry

A discussion of the past and current gendered power imbalances within the field of psychiatry, focussing on the unique position of trans- identifying people. Along with the historical and current medicalization of trans identities, the treatment of trans people is explored in the context of transphobia within the medical community.

Transphobia in the Lesbian Community

An analysis of the roots of transphobic sentiments found within the lesbian community, centring around Elliot Page's coming out post in December 2020. The reactions to his post are discussed alongside the history of uniquely lesbian transphobia from the late 1980s to the present day, with a special focus on feminist and activist lesbian spaces.

Erotic Truths: Queer Temporality in Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home

An analysis of how Alison Bechdel's graphic novel Fun Home combines the past with the present, queering and playing with time throughout the narrative. Through various elements including literary allusions, recursive storytelling, and the comic format itself, the fluidity of time and the lives of non-normative people are explored and deconstructed.

Human Anatomy

Pathway of a Red Blood Cell: From the Heart and Back to the Heart

A multimedia presentation of the basics of the circulatory system, including the anatomical structures and their functions. Information included ranges from hematopoeisis, to the structure of the heart, to the various forms of circulation in the human body (systemic, pulmonary, and coronary).

Film

Cultural Histories as Reflected in French Impressionism and German Expressionism

French Impressionism and German Expressionism are two different, yet similar, film movements, each reflecting a distinct cultural and historical worldview. Through comparisons of the Mise-en-Scène, characterization, and major themes of films such as Jean Epstein's The Fall of the House of Usher (1928) and Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), the sociocultural beliefs and current social anxieties of the filmmakers and general populations are revealed.

Friends on the Other Side: Queer Villainy in Disney Animation

Though Disney animated villains are often queered or Othered in an attempt to impart mainstream norms on the viewing audience, the same process of "Othering" may instead result in the empowerment of a marginalized viewer through a process José Muñoz calls disidentification. Drawing on the normative expectations of gendered social roles, as well as the increased commercialization of villainy by the Disney corporation in the last three decades, the social power - and acceptance - of queerness in Disney's animated villains is explored.

P.S. I HIGHLY recommend Fun Home; it's a wonderful book. At times, a bit harrowing, but incredibly poignant and beautiful. There's also a Broadway musical version of the story!

#I'll reveal the answer in a day or so :>#krenenbaker's :)#I used the words ''discussion'' ''exploration'' and ''analysis'' WAY too many times in those little descriptions#it doesn't really matter but that and the amount of passive voice here is... yeeesh. I'm apparently very out of practice writing abstracts#the abstracts aren't great... my actual writing is much better... I promise!#and it's funny... I wrote a LOT of Gender Studies papers considering it wasn't my major (it was my minor though so that kind of makes sense

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tagged by: @mokureen welcome back!

Favourite colour? Purple is my best friend 💜

Currently reading? Fun Home by Alison Bechdel. I’m not used to graphic novels, but it’s well-written and the level of detail on the art is impressive.

Last song? Ta fête by Stromae. His music gets played a lot while I’m studying.

Last movie? I’ve been so busy that it’s been a while since I’ve seen any! My most recent was probably Everything Everywhere All at Once a few months back, which I’d be willing to watch again.

Sweet/savoury/spicy? Sweet. In any given debate about whether X dessert/ice cream flavour/lolly etc. is good or not, I am arguing in favour of it. Liquorice is good. Turkish delight is good. Chocolate mint is good. Accept the sugar, cowards.

Currently working on? My essay on queer temporality due in two weeks (scary). When that’s done, I am working to turn a messy document of characters and plot points into a coherent coming-of-age story.

Tagging: @leftist-taser @evilcatgirlwizard @fatalwamod NO pressure my wonderful mutuals this is just for fun

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apparently it’s international podcast day. Here are some of my favourites.

Temporal Discussion: The Knightmare Podcast (my absolute favourite)

Professional Contestants

The Infinite Escape Room

Escape This Podcast

Verity!

Hey Riddle Riddle

Queers Gone By

Two Geeks, Two Beers

Meddling Adults

OverTheHills

#I listened to the Professional Contestants Raven episode the other day#It’s so inaccurate and yet so funny#Plus they get bonus points for being so right about Where in the world is Carmen Sandiego#International podcast day

0 notes

Text

Reparative Reading

I would love, and indeed have been meaning for a long time, to talk about a piece of academic writing from one of my favourite theorists that I think has an ongoing relevance. This is Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading,” first published in the mid-to-late 1990’s and compiled in her 2003 monograph, Touching Feeling. There’s a some free PDFs of it floating around (such as here) for those who want to read it in full – and I would recommend doing so, despite its density in places, because Sedgwick has a marvelous critical voice.

Sedgwick’s topic of contention in this essay is the overwhelming tendency in queer criticism to employ what she thinks of as a paranoid methodology – that is, criticism based around the revelation of oppressive attitudes, and that sees that revelation not only as always and inherently a radical project, but the only possible anti-oppressive project. This methodology is closely related to what Paul Ricoeur termed the “hermeneutics of suspicion” and identified as central to the works of Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud, which were all progenitors of queer criticism. Sedgwick objects to the fact that the hermeneutics of suspicion had, at her time of writing, become “synonymous with criticism itself,” rather than merely one possible critical approach. She questions the universal utility of the dramatic unveiling of the presence of oppressive forces, pointing to the function of visibility itself in perpetuating systemic violence, and identifying the work of anti-oppression as one based in a competition for a certain type of visibility. She also rejects the knowledge of the presence of oppression alone as conferring a particular critical imperative, instead posing the question, “what does knowledge do?”

As an example, Sedgwick critiques Judith Butler’s commentary on drag in Gender Trouble, one of the works that she uses as an example of a reading based in a paranoid approach. She identifies Butler’s argument that drag foregrounds the constructed aspect of gender as a paranoid approach, due to its focus on revelation of structures of power and oppression, and she finds Butler’s argument lacking in its neglect in acknowledging the role that joy and community formation play in the phenomenon of drag. Near the end of the essay, she also does an example of a reparative reading of the ending of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, claiming that the narrator’s remove from the traditional familial structure and its temporality is precisely what confers his particular moment joy and insight upon discovering that his friends have aged. Broadly, Sedgwick rejects the implication that readings based in joy, hope, or optimism are naïve, uncritical, or functionally a denial of the reality of oppression.

Now, it’s important to note that the message of this essay is not that paranoid readings are bad, and reparative readings are good. Sedgwick is drawing on a body of affect theories (most prominently Melanie Klein’s) that posit the reparative impulse as dependent on and resulting from the paranoid impulse – reparation by definition is something that can only occur after some kind of shattering, and Kleinian trauma theories generally posit that process as something that produces a new object or perspective than pre-trauma. (Something I love about Sedgwick is that she often sets up these binaries that seem at odds with each other, but end up being mutually dependent.) Furthermore, the critical tradition in queer studies that Sedgwick is critiquing in this essay is one that was itself, in many ways, a manifestation of communal trauma, particularly with the impact of the AIDS crisis. Sedgwick herself acknowledged this last point in a later essay, “Melanie Klein and the Difference Affect Makes,” claiming that she didn’t feel she did a good enough job of identifying the AIDS crisis as a driving force behind this trend. So Sedgwick is not discounting the utility of paranoid readings, but rather rejecting the notion that they ought to encompass all of criticism. (In fact, a running theme in Touching Feeling is her representation of various perspectives and methods as sitting beside one another, rather than hierarchically.) And reparative reading, as Sedgwick portrays it, is not the denial of trauma or violence, but a possibility for moving forward in its wake.

Why am I taking the time to outline all of this? Because, while the original essay was written almost 25 years ago, with the academic community in mind, it reflects a similar pattern that I see now in online fandom.

Queer fandom (as that’s what I feel the most qualified to talk about) has a considerable paranoia problem. Queer fandom is brimming with traumatized people who carry varying degrees of personal baggage and are afflicted by the general neuroses that come from existing in a heterosexist, cissexist society. And many people in fandom have been repeatedly burned by the treatment of queer people in media – Bury Your Gays, queerbaiting, queercoded villains, etc. And in such a media landscape, and within such a communal sphere, much of fandom has developed the kind of “anticipatory and reactive” method of media criticism that Sedgwick identifies in this essay.

Fandom gets very excited for new media, certainly, and is prone to adulation of media that seems to fit its ideological beliefs. But it is also very quick to hone in on any potential representative flaw, and use that as a vehicle for condemnation. (This cycling between idealization and extreme, bitter jadedness has been widely commented on). Not only is there a widespread moralistic approach in fan criticism that is very invested in deeming whether or not a piece of media is harmful or not, “problematic” or not, within a simplistic binary framing, but that conclusion is so frequently the end of the conversation. “This is problematic,” “this is bad representation,” “this falls into this tired and harmful trope,” etc, is treated as the endpoint of criticism, rather than a starting point. This is the spectacle of exposure that Sedgwick critiques as central to the paranoid approach – simply identifying the presence of oppressive attitudes in a text is not only treated as an analytic in and of itself, but as the only valid analytic. So often I have seen people jump to take the most pessimistic possible approach to a piece of media, and then proceed to treat any disagreement with that reading as in and of itself a denial of structural homophobia, as naïve, and as not being a critical enough reader/viewer. “Being critical” itself has been taken on as a shorthand for this particular process, which many others have commented on as well.

Now, again, I want to stress that taking issue with this totalizing impulse is not discounting the legitimate uses of identification and exposure, or even of reactivity and condemnation. There are particular contexts in which these responses have their uses – in Sedgwick’s words, “paranoia knows some things well and others poorly.” But that approach has a finite scope. And rejecting the universal application of this particular analytic does not itself constitute a denial of the existence of oppression, or its manifestation in media and narratives. Nor is it about letting particular works “off the hook” for whatever aspects they may have that are worthy of critique. Rather, it’s a call to acknowledge that other critical approaches exist, and that the employment of a more optimistic approach is not necessarily a result of ignorance or apathy about the existence of oppression. It is one that invites us not to lay aside paranoia as an approach, but recognize that it has limited applicability, and question when and how our motives might be better served by another approach.

I think that “is this homophobic, yes or no?” or “is this good representation, yes or no?” are reductive critical approaches in and of themselves. But I think there’s also room for acknowledgment that not everything needs to be read through a revelatory lens regarding societal oppression at all. Rather than “what societal attitudes does this reflect back?” being the approach, I think there could be a good bit more “What does this do for us? What avenues of possibility does this have?” I think there’s already been leanings in this direction with, for example, the reclaiming of queercoded villains, with dialogues that treat those characters not as reflections of societal anxiety and prejudice, but rather as representative of joy and freedom and possibility in their rejection of norms and constraints. I’d like to see that approach applied more broadly and more often.

Let’s try to read more reparatively.

#alpha speaks#alpha's literary opinions#eve sedgwick#literary criticism#queer studies#help me sedgwick#also apparently 'reparatively' isn't actually a word but sedgwick invented words in a similar way all the time so#lord i hope this is all coherent...#these concepts are always more complicated and harder to convey than they seem#my meta#big sigh.#queue#for pillowfort#(when it comes back online)

226 notes

·

View notes

Note

I just finished Ronin and it's now my favourite ever Star Wars book. Your writing is so beautiful and the plot!! It's so layered, like when you think understand it there's another level to it! The characers and story are the most original I've ever seen. I can't praise this enough, I'd rate your book 100 out of 10 if I could. (1/2)

Ahhhh <333 thank you, it is always a boon to hear when the book gives people a good time. I didn't intentionally write it with reread value in mind, but it seems to have a good deal! Which I suppose makes sense given my tendency to saturate stories with SECRETS. I am glad it paid off for you <3

Also...thank you for loving the Traveler in specifically the way you do. I wanted someone like them to be in Star Wars because I wanted to have had someone like them to imprint on as a kid, you know? Somewhat adjacently, I think of this book as being pretty firmly rooted in both my mixed and diasporic experience because, well, that's the only perspective I can write from. I'd be powerfully interested in reading a Japanese iteration on Star Wars from someone with closer temporal ties to Japan -- though the Visions project as a whole is this in a lot of ways. (Which is to say: I recognize this anxiety. I encourage embracing it. We are who we are. We have the relationships with our history that we have. There's a beauty in that as well.)

FINALLY: I have not yet read Gearbreakers, though the second I saw the pitch I was like "aha, a book FOR ME." But then I am also writing in the queer mech genre and was fated to be a giant nerd about it :P (The Archive Undying's ABMs have gone out into the world and i am low-key dying about this all the time. "read my book! BUT DON'T LOOK AT ME, SO HELP ME GOD." etc.)

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Em)Urgency Performance Symposium Program for Day 2

(EM)URGENCY - DAY 2

BA Performance Arts – A First year showcase

1pm-5:30pm

On Listening

All the works presented today are a response to Text as Performance, a first-year unit that this term explored the theme of On Listening. Performance Arts is a course which brings together a range disciplines – and all the artists have responded in their own way to what has been presented during the term. No piece is the same, no artist is the same, and we present to you an eclectic mix of short and early work that may influence our later practice – this is our first public sharing as a cohort, so please speak to the artists and enjoy.

With thanks to: Third Year students on BA Performance Arts, Platform Southwark and Diana Damian Martin.

Durational works – in the studio

Untitled

Billy Buttars

An exhibition of paintings, sketches, and other works that are reinterpretations of texts into visual forms. Exploring text in the language of art objects, and concepts of inspiration and influence.

Billy’s work surrounds concepts of personal influence and representation, as well as what radical really means in a temporal context and the impermanence of it all.

Gaze

Joy Kincaid

Whose body is this

As she looks at her

With your eyes at her

As she sees herself

She sees what you see

And then doesn’t see

So, she looks at herself

And doesn’t look at herself

This is not meant for you to watch?

If watching was the only way

Then I ask you not to watch

I ask you to engage more then

Your eyes and your hands

And your mind

I ask you to see more then

Her. I ask you to see yourself

And in her yourself is buried

And in myself your eyes are burned

So, I ask you not to watch

But be born

As she is born

Joy Kincaid is a multidisciplinary artist whose work is centred on deconstructing monolithic narratives on black and queer bodies within the interrelations of white spaces through radical acts of embodied contradictions, witnessing and shape shifting.

Family Jukebox

Tom Dodd

In the foyer and someone will wait, pick a mixtape? Choose your favourite song? that I will then play for them. Songs chosen by the performer’s family members – take your pick and hear the soundtrack of someone’s life?

Tom is a performer who hopes to work with sound and how sound affects people. The company Darkfield are one of his biggest inspirations and he looks forward to creating similar work. For tonight’s performance Tom will be looking at how sounds in the forms of songs affect different members of his family.

Performances – on the stage

What is the C word?

Alicia Bridges

‘What is the C word?’ explores ideas of Consent in an abrupt, disassociated, inhumane way. From my own experience, I feel I have always been trying to connect the pieces together.

Content warning: references to sexual assault.

Alicia enjoys and is interested by multimedia performance, verbatim and immersive theatre. Throughout her degree she expects this will change and develop. She is excited by the prospect the next three years will give her to challenge her own artistic practice. She has previously worked with physical theatre and directing.

Instagram: @alixiabridge

Voicemail

Jody Davies and Chloe Knowles

‘Voicemail’ is a physical theatre piece that reflects upon real-life experiences both artists have endured. These two different stories surround listening and lack there-of, where both artists reflect on unsent voicemails they wish they had sent.

Content warning: references to sexual and domestic abuse, emotional manipulation, explicit language.

Jody Davies is a Welsh performance artist with a background across musical theatre, physical theatre and experience in vocal coaching. Her interests include live art and photography but her works mainly consists and explores physical theatre and immersive projects.

Chloe Knowles is a performance artist from England.

She has experience in acting, writing as well as directing theatre for younger children between the ages 7-16 at Sonnets Theatre Club Newbury, John Rankin Junior School, and Cheam Private School.

Her Interests mostly include writing and directing.

When I was 5?

Jaydon Merrick

An exploration of celebrity idolisation, jealousy and discarded dreams through a casual, reflective and participatory dance experience. Suitable for all skill levels, the less talented the better.

Jaydon is an Australian actor, writer and director. He has been living in the UK for 2.5 years now; in Australia, Jaydon’s work was heavily musical, and stage based, since moving to the UK his practice has become more film and screen orientated.

Nostalgia for a Time Gone Nowhere

Evie Stopforth

I feel like I am constantly leaving a home behind. I know you inside out and they have no idea who you are. I’m three different people, and a stranger.

Evie Stopforth is a young performance artist investigating the relationship between audio and visual entertainment. She focuses in this piece on loneliness, homesickness and the feeling of being stuck in limbo.

It’s Your Birthday!

Miel Celeste Nadam

‘It’s Your Birthday!’ is derived from a personal hatred of my own birthday. I regress into a somewhat younger and pinker version of myself, as the cracks of the present seep through.

Miel is interested in the idea of nostalgia and objects behaving badly. For her, art is the most potent when humour is sprinkled into pain. Laughing can slip into crying.

Candidate 14

Grace Oskiera-Vooght

An examination for a job role that requires you to not react, talk or feel. You must detach yourself from human instincts: feelings. Will you pass or fail?

Content warnings: references to death and suicide.

Grace has a background in straight acting and is interested in the arts sector. She is interested in writing, creating, directing and performing. She has a cross-arts practice taking inspiration from across many art forms, particularly performance. She is currently interested in exploring intimacy and relationships and the way it is performed as part of her arts practice.

The Trestle at Pope Lick Creek (Cancelled)

Reena Black

This adaptation of 'The Trestle at Pope Lick Creek' explores the underlying, darker themes of the play. This piece will delve into the character's mind and bring the audience with her on her journey of confession.

Content warnings: references to death and mental illness.

Reena Black is a British actress, dancer and writer; she has been trained in classical and contemporary acting techniques for many years. Experimenting with different techniques has always been a passion of hers and she is continuing to do this through her degree in Performance Arts.

Dès l’aube

Irène Pawin

Look around. What can you hear? Smile. This experience is only for you. Put on the headphones. Only you will hear this story. You are truly special. Enjoy.

Content Warnings: mentions of death, suicide, and explicit content in some pieces.

Irène is exploring her potentiality as an artist, and has been exploring writing her own work. Irène is particularly interested in oddness and queerness, the feeling of being out of place, of being foreign. Irène is an impulsive creator that never knows what her next obsession will be.

Dinner Time

Cerys Salkeld Green

A piece focussing on the idea of intrusive thoughts and dealing with grief in opposition to modern life.

Content warning: references to sex and sexual content

Cerys is interested in the boundaries between fact and fantasy.

Alexa

Owen Whiteside-Ward

Alexa: With technology always advancing, what happens when technology makes certain advances?

Owen is a writer, director and performer from Norwich. He has a long history of musical theatre work as a performer and in the last few years has written directed and produced his own musical: this is something he is currently still doing, working on numerous other musicals. In addition to this Owen has taken a strong interest in writing plays and films and likes to create pieces that often leave the audience questioning. This is Owen’s first work outside of Norwich, which he is looking forward to.

Email: [email protected]

Can you hear it?

Esme Mai Davies

Can you hear it? Is an immersive piece that combines film, sound and live elements. What happens when you lose safety in your spaces?

Content warnings: mental health and panic

Esme as an artist is primarily interested in performance; her background is in traditional theatre. She is now exploring a mixture of performance, visual art and drag as well as working to incorporate technology and new mediums into her work.

A train running on a jointed track

Ben Church

When we listen schematically, do we listen for the relation between sounds? Or is it something more? This piece aims to answer none of these questions.

Ben Church is a performance artist with a multitude of different interests and fields of study. These range from more traditional acting at Stratford upon Avon’s RSC, to writing and co directing pieces of immersive theatre and teaching drama. More recently he has been looking into composition and how sounds gain meaning.

Why Are You Wearing That Stupid Man Suit?

Anja Hendrichova

Dates first dates no dates first sex holding hands broken hearts brave knights crushed buses Czech girl singing jumping in the rhythm of love or no love the end.

Rather than viewing this piece as a criticism of any kind, feel free to laugh at me and / or with me. Anja has the superpower to watch the same film or series 50 times. The more people to embarrass in front of, the less shy.

Find your Bite

Jack Gallagher

Find your bite tonight. I know you have it in you. Please.

Content warnings: references to sexual violence.

Breathe

Tsen Day-Beaver

During this piece I focus heavily on the subject of panic within the body, documenting its reactions and tendencies, situating this subject in the event of a panic attack.

Tsen is an artist/performer from Scotland interested in performance within film and text-based work. She is currently focusing on composition of the body within performance and its relation to the mind.

displacement

Jasmine Wright

Ripped away. It’s not homesickness, it’s yearning for a place that doesn’t exist anymore. Is home a place or a feeling, and how can I find it again?

Jasmine is currently exploring ideas of unfamiliarity, strangeness, the body, and Asian heritage. She is really enjoying writing as/for performance. She is also interested in creating multimedia experiences and experimenting with artificial, anthropogenic, and naturogenic sounds and visuals.

See with Sound

Juan Salazar

A quick informational guide on maternity, nuclear fallout and social conventions. The piece explores themes of listening through imagination, primal instinct and tribalism in a post-war, ever-growing technological society.

Juan is an audio-visual artist. He is interested in space, time, dreams, memory, metaphysics, meta-metaphysics, regular physics, and irregular physics.

Can you hear my silence?

Molly Denbigh

When silence becomes too loud.

Feelings of anxiety and fear are felt by many but speaking up honestly about them is done by few. It’s difficult. Emotional. I ask myself the questions that we need to answer for ourselves. Do I truly belong? Am I me?

Molly Denbigh is a performance artist with interests in immersive and physical theatre. She is also interested in fine art and musical theatre and would love to combine these different styles in future work.

The School Pen

Mia Lulham

A short immersive/interactive piece commenting on the learning difficulties neurodiverse children face when first entering the education system. The piece shows the struggles involved with “basic” tasks such as learning to read and write.

Mia is heavily interested in and influenced by dance, choreography and physical theatre as well immersive theatre, and aims to continue to use these influences in her developing practice.

The Voice

James Brewer

A man must overcome his anxiety about how he sounds and goes through many different types of voices in order to pick the right voice that suits him most.

James is an actor and performance artist from East London who has worked with London Bubble Theatre and National Youth Theatre.

Can I be loud?

Beth Timson

Can I be loud? Who Can be loud in spaces and why? Where can we be loud? An exploration of loudness in institutional, normative space and where queer and non-normative identities fit in to this.

Beth’s work centres on community, feminism and queerness. Beth is a writer, theatre maker, spoken word artist and facilitator from East London, and an early career artist who has presented solo work at Shoreditch Town Hall and Battersea Arts Centre. Alongside studying for her degree at RCSSD, Beth is working, freelance in various capacities, ushering at The Yard Theatre, and as a Young Creative for All Change Arts. Beth started out in community arts and her work centres on using performance to bring people together and spark conversations. Her work is deeply political and seeks to challenge normativity.

www.bethtpeform.wordpress.com

twitter: @BethBRT

(Em)Urgency Festival Digital Feed

Noa Taylor in collaboration with the EFDF Collective

The (Em)Urgency festival digital feed considers the performativity of multimedia performance documentation performatively. We document the work of the (Em)Urgency Performance Symposium and publish the material on social media platforms during the event.

Follow us on twitter: @em_urgency

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sources - Moche Sex Pots

Here is a list of sources that I used for our episode on the erotic ceramics of the Moche people of 2nd to 8th century Peru, as well as links to images of the pots we discussed. You can listen to the episode here.

It’s worth noting that if you speak Spanish, you’ll no doubt be able to find a lot more sources - I did quote from many more sources than these in the episode, but those quotes were limited to the translations which can be found in these texts. This list should at least provide a start for English speakers, and the bibliographies of these articles will include further Spanish and other language sources

Janusz Z. Wołoszyn and Katarzyna Piwowar’s “Sodomites, Siamese Twins, and Scholars: Same‐Sex Relationships in Moche Art“, in American Anthropologist, Vol. 117, No. 2 (2015), p.285-301

This is a good introduction to scholarship on the Moche sex pots over the past 100 or so years. It also has better and clearer images of the pots we discussed than I was able to find anywhere else. You can also find these on our blog under the Moche tag.

Somebody did comment on one of our posts that they were offended by the word “sodomite” in the title, so I’ll just note that Wołoszyn and Piwowar are using this word as a reference to how these pots have been interpreted by homophobic scholars, and not because they consider it appropriate in a modern context.

Michael J. Horswell’s "Toward an Andean Theory of Ritual Same‐Sex Sexuality and Third‐Gender Subjectivity” in Infamous Desire: Male Homosexuality in Colonial Latin America (2003), p.25–69.

This includes a very useful summary of Manuel Arboleda’s work on queer Moche pots, for those of us who don’t speak Spanish. Horswell also explores the possibilities of what the role of third-gender people in their pottery may have symbolised to the Moche people.

Mary Weismantel's “Moche Sex Pots: Reproduction and Temporality in Ancient South America” in American Anthropologist, Vol. 106, No. 3 (2004), p.495–505.

This article talks about the Moche erotic pots generally. Weismantel doesn’t focus in particular on queer themes, but does provide some interesting thoughts on why the Moche chose to depict the types of sex that they did.

Edit (2022): since we posted this, Weismantel has now written a whole book on the sex pots: Playing with this: Engaging the Moche Sex Pots. Well worth a read - check out our review if you want to know more.

Richard C. Trexler’s Sex and Conquest: Gendered Violence, Political Order, and the European Conquest of the Americas (1995).

Richard Trexler is probably my least favourite scholar when it comes to discussions of Indigenous American gender, but I include him here for the sake of completeness - for a full explanation of why I disagree with so many of Trexler’s ideas, you’ll have to listen to our podcast. If you do want to read his own words, most of his writing about the Moche can be found in his chapter “The Religious Berdache”.

Peter Mason's "Sex and Conquest: A Redundant Copula?” in Anthropos Vol. 92, No.4–6 (1997), p.577–582.

This review of Trexler’s work started a feud of several years between the two scholars. I didn’t get much new information from it, but if you want to read Trexler get dragged then here is a good place to do it.

Ramón A. Gutiérrez’s “Warfare, Homosexuality, and Gender Status among American Indian Men in the Southwest” in Long Before Stonewall: Histories of Same‐Sex Sexuality in Early America (2007), p.19–31.

Gutiérrez doesn’t write specifically about the Moche in any detail, and where he does his opinions are obviously very informed by the work of Trexler. I’m including this source only for the sake of completeness.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hawksmoor, BBC Sherlock and historiographic metafiction

First:

This piece is not of academic quality or rigour. I left university eight years ago; I studied literature in two languages and did well at it. Nevertheless I am no longer in academia and have not written an essay since then. My sources are partial, dependent on what I can get access to through my local library, through academic friends, or what I choose to pay for on JSTOR. I work full-time and have put no time into e.g. referencing (always my least favourite part of essays).

Although I personally hold out hope for unambiguous Johnlock still, I would not class this as a ‘meta’ arguing that it will certainly happen. This is a reading, undertaken for my own satisfaction and interest, jumping off from the inclusion of ‘Hawksmoor’ as a password in one scene of The Six Thatchers. I do not particularly mean to suggest that Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat are deliberately playing with/off literary criticism. They may well be holding two (or more) time periods in tension, however, in a way that I choose to explore through the lens of the literary tools described here. I do not seek to challenge or disprove other fan theories.

I am no television/film studies scholar. There are probably layers and layers of nuance and meaning that I’m missing because I simply have no frame of theoretical reference in that field (and one of the primary ‘texts’ we are talking about here is, after all, a television show). The abundance of television and film references discovered by Sherlock fans have made it clear that the show’s creators deliberately allude to other visual media within modern Sherlock all the time. I believe my approach here is valid because Hawksmoor, a literary text, is pointed to in the show, and because ACD canon itself was a literary text. But I want to flag up this important way in which my analysis is deficient.

I tagged a few people in this but I’m aware this is more of a musing/essay than a traditional ‘meta’ so don’t worry about reading/responding if it’s not your thing!

The Six Thatchers

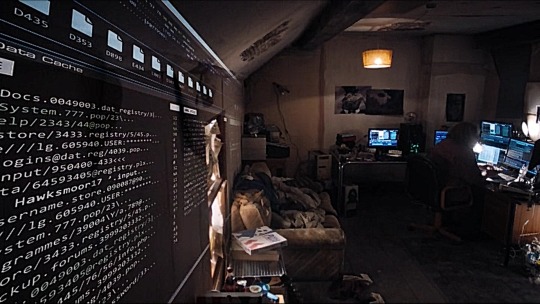

In The Six Thatchers, Sherlock visits Craig the hacker, to borrow his dog Toby. On the left of our screen (taking up an entire wall of Craig’s house, realistically enough…) are lines of code, in the centre of which is written ‘Hawksmoor17’.

I was interested in finding out more about this. I decided my first port of call would be the ‘detective novel’ Hawksmoor, by Peter Ackroyd.

Peter Ackroyd

Peter Ackroyd is a historian and author, who has written a huge array of fiction and non-fiction, including:

London: The Biography (non-fiction)

Queer City: Gay London from the Romans to the Present Day (non-fiction)

The Last Testament of Oscar Wilde (an imagining of the diary Oscar Wilde might have written in exile in Paris)

Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem (novel, presenting the diary of a murderer)

Hawksmoor (novel)

In his work London is present, constantly, a character in itself, woven into the very fabric of the story as irrevocably as it is into the mythos of Sherlock Holmes.

Hawksmoor

In brief, Hawksmoor is a postmodern detective story, running in two timelines. Each timeline focuses on a main character: in 1711, the London architect Nicholas Dyer; two hundred and fifty years later, in the 1980s, Nicholas Hawksmoor, a detective, responsible for investigating a series of murders carried out near the churches built by Dyer.

Ackroyd plays with the ‘real history’ of London throughout, muddling and confusing the past with fictional events, with conspiracy and rumour.

There was a real London architect named Nicholas Hawksmoor who worked alongside Christopher Wren in eighteenth-century London to design some of its most famous buildings. He also designed six churches. Ackroyd chooses to change the eighteenth-century architect’s name to Nicholas Dyer, and to make Nicholas Hawksmoor the twentieth-century fictional detective instead – a deliberate muddling together of timelines and of ‘facts’.

Ackroyd had drawn inspiration for Hawksmoor from Iain Sinclair’s poem, ‘Nicholas Hawksmoor: His Churches’ (Lud Heat, 1975). This poem suggests that the architectural design of Hawksmoor’s churches is consistent with him having been a Satanist.

As well as changing the historical figure Hawksmoor’s last name to Dyer, Ackroyd adds a church, ‘Little St Hugh’. Seven, in total.

The architect Dyer writes his own story, in the first person and in eighteenth-century style.

Only in Part Two of the novel does Nicholas Hawksmoor – a fictional detective with a real man’s name – appear, to investigate the three murders that have so far happened in 1980s London. Written in the third person, the reader is nonetheless invited into Hawksmoor’s thoughts, his point of view.

As the novel proceeds, Ackroyd employs literary devices so that the stories – separated, apparently, by so much time – begin to blur. In particular, the architect Dyer and the detective Hawksmoor are linked. For instance, both men experience a kind of loss of self, a “dislocation of identity”, upon staring into a convex mirror (Ahearn, 2000, DOI: 10.1215/0041462X-2000-1001).

The cumulative effect of all the parallels is that the reader starts to lose any sense of temporal separation between the time periods; starts to see Dyer and Hawksmoor as almost the same person; to suspect each of them of being the murderer and the detective at the same time. The parallels between the time periods “escape any effort at organization and create a mental fusion between past and present” so that “fiction and history fuse so thoroughly that an abolition of time, space, and person is […] inflicted on the reader” (Ahearn, 2000).

Importantly, I believe, Hawksmoor again and again “tries to reconstruct the timing of the crimes, but this is from the start impossible” (Ahearn, 2000). This is a rather familiar feeling to Sherlock Holmes fans.

At the end of the book, Dyer and Hawksmoor come together in the church, take hands across time, or perhaps out of time. They become aware of one another. Their perspectives dissolve and seem to merge into one person, into a new style of narration not like either of them: “when he put out his hand and touched him he shuddered. But do not say that he touched him, say that they touched him. And when they looked at the space between them, they wept” (Ackroyd, 1985).

Historiographic metafiction

Hawksmoor is a postmodern detective story. It has been classified by critics as a work of ‘historiographic metafiction’. As a detective story, it lacks the most familiar feature – a detective who is able to sort and order the events and facts, before finally drawing together all the threads to present a coherent, satisfying and plot-hole-free conclusion. In other words, a solution to the mystery.

So what is ‘metafiction’? Waugh defines it as “a term given to fictional writing which self-consciously and systematically draws attention to its status as an artefact in order to pose questions about the relationship between fiction and reality” (1984).

In Hawksmoor, Ackroyd uses a popular literary form (the detective story) to unsettle our understanding of fiction, reality and history. An Agatha Christie detective novel (for example) relies on an accepted, understood structure, where the reader has definite expectations of what the outcome will be; as such, Christie’s novels “provide collective pleasure and release of tension through the comforting total affirmation of accepted stereotypes” (Waugh, 1984). In metafiction, however, there is often no traditionally predictable, neat, satisfying ending: accepted stereotypes are disturbed rather than affirmed. The application of rationality and logic to the clues gets the detective no closer to solving the crime. Readerly expectation (“the triumph of justice and the restoration of order” [Waugh, 1984]) is thwarted.

Hutcheon coined the term ‘historiographic metafiction’, fiction where “narrative representation – fictive and historical – comes under […] subversive scrutiny […] by having its historical and socio-political grounding sit uneasily alongside its self-reflexivity” (Hutcheon, 2002). It is a kind of fiction that explicitly points out the text-dependent nature of what we know as ‘history’: “How do we know the past today? Through its discourses, through its texts – that is, through the traces of its historical events: the archival materials, the documents, the narratives of witnesses…and historians” (Hutcheon, 2002).

Whereas a ‘historical novel’ will present an account of the past which purports to be true, a ‘historiographic metafiction’ has a combination of:

deliberate, self-reflexive foregrounding of the difficulty of telling ‘the whole story’ or ‘the whole truth’ especially due to the limitations of the narrative voice;

internal metadiscourse about language revealing the fictional nature of the text;

an attempt to explain the present by way of the past, simultaneously giving a (partial) account of both;

disturbed chronology in the narrative structure, representing the determining presence of the past in the present;

‘connection’ of the historical period structurally to the novel’s present;

a self-consciously incomplete and provisional account of ‘what really happened’ e.g. via ‘holes’ in the [hi]story which cannot be resolved by either narrator or reader (Widdowson, 2006, DOI: 10.1080/09502360600828984).

The above points are certainly true of Hawksmoor. The reader of Sherlock Holmes will find some of them very familiar – for example, Watson’s self-conscious in-world changing of dates, names and places; and the impossible-to-resolve timeline. The audience of BBC Sherlock will also find these features very recognisable, especially from Series 4 of the programme.

I’d like to examine BBC Sherlock itself as a ‘historiographic metafiction’: a ‘text’ which self-consciously holds the past and present fictional events of Sherlock Holmes’ life in tension, not merely as another adaptation of the source text, but as a way of destabilising the accepted ‘[hi]story’ and mythos of Sherlock Holmes.

The Great Game

The Sherlockian fandom is well-known for its practice of ‘The Great Game’:

“Holmesian Speculation (also known as The Sherlockian game, the Holmesian game, the Great Game or simply the Game) is the practice of expanding upon the original Sherlock Holmes stories by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle by imagining a backstory, history, family or other information for Holmes and Watson, often attempting to resolve anomalies and clarify implied details about Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson. It treats Holmes and Watson as real people and uses aspects of the canonical stories combined with the history of the era of the tales' composition to construct fanciful biographies of the pair.” [x]

There are a number of interesting features about the Great Game. It:

pretends that Sherlock Holmes and John Watson were real people;

ignores or explains away the real author Arthur Conan Doyle’s existence;

attempts to use ‘real’ historical facts (texts…) to resolve gaps in a fictional text;

in turn, produces additional (meta)fictional texts, often presented as ‘fact’ in journals set up for the purpose;

in so doing, adds constantly to the (meta)fictional destabilisation of chronology and holes in the story, as different, competing ‘versions’ are added by a multitude of authors.

The Sherlock Holmes fandom, as it attempts to elucidate ‘what really happened’, only destabilises the original (hi)story further – drawing attention, over and over again, to the gaps and inconsistencies in the original canon tales.

I would argue that the Sherlock fandom has been engaged, for over a century, in an act of collective historiographic metafiction.

The writers of BBC Sherlock are aware of themselves as fans, and of the wider Sherlockian fandom. They paid tribute to Holmesian Speculation in the episode title of Series 1 Episode 3. The title – ‘The Great Game’ – is a signal, an early marker of postmodernity in BBC Sherlock, a sign that the Sherlockian fandom will not be absent from this metafiction.

Implicating the reader/audience

There is an interesting moment in Hawksmoor where Detective Chief Superintendent Nicholas Hawksmoor goes to investigate the murder of a young boy near the church of St-George’s-in-the-East. The body is beside “a partly ruined building which had the words M SE M OF still visible above its entrance” (Ackroyd, 1985).

As Lee says, the “missing letter is "U," ("you") the reader” (1990).

Elsewhere in the book, Hawksmoor receives a note instructing him “DON’T FORGET … THE UNIVERSAL ARCHITECT” alongside a “sketch of a man kneeling with a white disc placed against his right eye” (Ackroyd, 1985).

Lee suggests that this drawing refers to “detective fiction’s transcendental signifier” Sherlock Holmes, and that the “Universal Architect, here, can only be the reader, since it is he or she who is in possession of all the histories: the historically verifiable past, the eighteenth-century text and the text accumulated through reading”. Thus, the reader is “doubly implicated not only as a repository of the past, but also as a co-creator of artifact and artifice” (Lee, 1990). In the Sherlock Holmes fandom, this is more true than in almost any other; co-creators indeed.

The missing ‘U’ in Hawksmoor can be clearly linked to the daubed ‘YOU’ in ‘The Abominable Bride’, a sign that, from that point on, BBC Sherlock will be clearly and mercilessly implicating its audience; putting the Sherlockian fandom back in the story, where it has always belonged. This includes the writers and creators of BBC Sherlock.

I also think there is reason to link the ‘YOU’ daubed on the wall to another piece of graffiti in BBC Sherlock – the yellow smiley face in 221b. An all-seeing, ever-present audience within Sherlock and John’s very home.

It is often repeated that Arthur Conan Doyle only continued to write Sherlock Holmes stories out of financial necessity and due to public demand; that he was bored and exasperated by his creation. The Sherlock Holmes fandom is (possibly apocryphally) known as having worn black armbands in the street in mourning for the fictional detective when Conan Doyle attempted to kill him off in The Final Problem.

The Sherlock Holmes fandom has long been considered importunate and unruly. As Stephen Fry puts it in his foreword to The Case Book of Sherlock Holmes: “Holmes has been bent and twisted into every genre imaginable and unimaginable: graphic novels, manga, science fiction, time travel, erotica, literary novels, animation, horror stories, comic books, gaming and more. Junior Sherlocks, animal Sherlocks, spoofs called Sheer Luck and Schlock; you think it up, and you’ll find it’s been done before. There is no indignity that has not been heaped upon the sage and super-sleuth of Baker Street” (2017).

And yet, with every new adaptation, there is a tendency to regard it as a blank slate, in direct conversation with the canon of Arthur Conan Doyle. There is a tendency to forget the changes that fandom itself has wrought on the figure of Sherlock Holmes – a weight of stereotype and expectation which warps the character to a pre-fit mould in every incarnation. As Fry says, Holmes:

“rises up, higher and higher with each passing decade, untarnished and unequalled. Because, I suppose, we need him, more and more, a figure of authority that is benign, rational, soothing, omniscient, capable and insightful. In a world, and in daily lives, so patently devoid of almost all those marvellous qualities, how welcome that is, and how grateful we are, for its presence in our lives. So grateful, that we won’t really accept that Sherlock Holmes could ever be classed as ‘make believe’. Between fact and fiction is a space where legend dwells. It is where Holmes and Watson will always live” (2017).

This is the traditional understanding of Sherlock Holmes and its fandom, and is highly reminiscent of the voiceover by Mary Morstan in Series 4 Episode 3, ‘The Final Problem’: “I know who you really are. A junkie who solves crimes to get high, and the doctor who never came home from the war. Well, you listen to me: who you really are, it doesn’t matter. It’s all about the legend, the stories, the adventures. There is a last refuge for the desperate, the unloved, the persecuted. There is a final court of appeal for everyone. When life gets too strange, too impossible, too frightening, there is always one last hope. When all else fails, there are two men sitting arguing in a scruffy flat like they’ve always been there, and they always will. The best and wisest men I have ever known – Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson.” [transcript by Ariane Devere]

The conception of Sherlock Holmes as “a figure of authority that is benign, rational, soothing, omniscient, capable and insightful” shows what we, the reader, want: a traditional detective story, with an all-knowing detective, who uses rationality and logic to assess the clues and brings us smoothly, at last, to a solution which reasserts the order of things; where justice is done and society is made safe once again.

BBC Sherlock, however, resists these comforting fictions. The detective unravels, becoming more emotional, more human as the story progresses. Mysteries go unsolved. The narrator gets more unreliable with every episode. Characters inhabit strange states, seemingly alive or dead as the story demands. The ‘rules’ of traditional detective fiction are flouted left, right and centre.

Viewed as a historiographic metafiction, BBC Sherlock aims to hold up the historical text (ACD canon) against the modern one (BBC Sherlock) in such a way as to slough away a century of extra-canonical fan speculation and addition, and give a new reading to canon.

‘Writing back’: re-visionary fiction

I would now like to look at Peter Widdowson’s journal article, ‘Writing back’: Contemporary re-visionary fiction’ (DOI: 10.1080/09502360600828984). He argues that there is a “radically subversive sub-set of contemporary ‘historiographic metafiction’” which, while being “acutely self-conscious about their metafictional intertextuality and dialectical connection with the past”, ‘write back’ to “formative narratives that have been central to the textual construction of dominant historical worldviews”.

Widdowson explains that his term ‘re-visionary’: “deploys a tactical slippage between the verb to revise (from the Latin ‘revisere’: ‘to look at again’) – ‘to examine and correct; to make a new, improved version of; to study anew’; and the verb to re-vision – to see in another light; to re-envision or perceive differently; and thus potentially to recast and re-evaluate (‘the original’)” (2006). He points out that this is closest to Rich’s approach to feminist criticism: “We need to know the writing of the past, and know it differently than we have ever known it; not to pass on a tradition but to break its hold over us” (Rich, 1975).

This act of ‘knowing it differently’ can also be achieved by “the creative act of ‘re-writing’ past fictional texts in order to defamiliarize them and the ways in which they have been conventionally read within the cultural structures of patriarchal and imperial/colonial dominance” (Widdowson, 2006).

Widdowson lays out what he regards as the defining characteristics of re-visionary fiction, first negatively by what it is not:

Re-visionary fiction does not simply take an earlier work as its source for writing;

It is not simply modern adaptation – instead it challenges the source text;

It is not parody – whereas parody takes a pre-existing work and reveals its particular stylistic traits and ideological premises by exaggerating them in order to render it absurd or to satirise the ‘follies of its time’, a re-visionary work seeks to bring into view “those discourses in [the source text] suppressed or obscured by historically naturalising readings. The contemporary version attempts, as it were, to replace the pre-text with itself, at once to negate the pre-text’s cultural power and to ‘correct’ the way we read it in the present” (Widdowson, 2006).

As to what re-visionary fiction is:

First, it challenges the accepted authority of the original. “[S]uch novels invariably ‘write back’ to canonic texts of the English tradition – those classics that retain a high profile of admiration and popularity in our literary heritage – and re-write them ‘against the grain’ (that is, in defamiliarising, and hence unsettling, ways)”. This means that “a hitherto one-way form of written exchange, where the reader could only passively receive the message handed down by a classic text, has now become a two-way correspondence in which the recipient answers or replies to – even answers back to – the version of things as originally delineated. In other words, it represents a challenge to any writing that purports to be ‘telling things as they really are’, and which has been believed and admired over time for doing exactly that.”

Second, it keeps a constant tension between the source and the new text. A re-visionary fiction will “keep the pre-text in clear view, so that the original is not just the invisible ‘source’ of a new modern version but is a constantly invoked intertext for it and is constantly in dialogue with it: the reader, in other words, is forced at all points to recall how the pre-text had it and how the re-vision reinflects this.”

Third, it enables us to read the source text with new eyes, free of established preconceptions. Re-visionary fictions “not only produce a different, autonomous new work by rewriting the original, but also denaturalise that original by exposing the discourses in it which we no longer see because we have perhaps learnt to read it in restricted and conventional ways. That is, they recast the pre-text as itself a ‘new’ text to be read newly – enabling us to ‘see’ a different one to the one we thought we knew as [Sherlock Holmes] – thus arguably releasing them from one type of reading and repossessing them in another.” The new text ‘speaks’ “the unspeakable of the pre-text by very exactly invoking the original and hinting at its silences or fabrications.”

Fourth, it forces the reader to consider the two texts together at all times: “our very consciousness of reading a contemporary version of a past work ensures that such an oscillation takes place, with the reader, as it were, holding the two texts simultaneously in mind. This may cause us to see parallels and contrasts, continuities and discontinuities, between the period of the original text’s production and that of the modern work.”

Fifth, they “alert the reader to the ways past fiction writes its view of things into history, and how unstable such apparently truthful accounts from the past may be”, making clear that the original text, though canon, was also just a text and should not necessarily govern our perceptions and understanding forever.

Sixth, “re-visionary novels almost invariably have a clear cultural-political thrust. That is why the majority of them align themselves with feminist and/or postcolonialist criticism in demanding that past texts’ complicity in oppression – either as subliminally inscribed within them or as an effect of their place and function as canonic icons in cultural politics – be revised and re-visioned as part of the process of restoring a voice, a history and an identity to those hitherto exploited, marginalized and silenced by dominant interests and ideologies.”

That last point, I think, should also apply to queer re-visionings of source texts (and indeed, Widdowson uses the example of Will Self’s Dorian: An Imitation re-visioning Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray in his article).

We can view BBC Sherlock as a re-visionary fiction which aims to ‘speak’ “the unspeakable of the pre-text by […] hinting at its silences or fabrications.”

BBC Sherlock as re-visionary fiction

Not only does BBC Sherlock have to hold itself up against the original canon of Arthur Conan Doyle; there is also a century of accumulated speculation and creation by an extremely active and resourceful fandom to contend with.

I think that BBC Sherlock asks us to re-vision ACD canon, but has a few sly jabs at the Sherlock Holmes fandom (including the writers themselves) along the way. Let’s look at some concrete examples:

John Watson’s wife:

In BBC Sherlock, the woman we know as Mary Morstan has no fixed identity. Her name is taken from a dead baby; she is not originally British; she is an ex-mercenary and killer; she is variously motherly, friendly and threatening; she shoots Sherlock in the heart – or does she save his life? In Series 4, her characterisation is more unstable than ever. She is a romantic heroine, a ruthless killer, a selfless mother, a consummate actress, a wronged woman, a martyr, an ever-present ghost, and the embodiment of John’s conscience. She is also the manifestation of the Sherlock Holmes fandom’s speculation about John Watson’s wife: did he have one wife, or six? Was she an orphan, or was she at her mother’s? When did she die? How did she die?

Ultimately, however, if you hold BBC Sherlock up against ACD canon, it highlights the fact that so many Sherlockians have tried to compensate for: in order to reconcile the irregularities in Mrs Watson’s story as narrated by Watson, she would need to be a secret agent actively hiding her identity. Examining BBC Sherlock against ACD canon makes us apply Occam’s Razor – the idea that the simplest explanation will always be best. John Watson’s wife was only written into the story because homophobia was so pervasive at the time that ACD was writing that his characters – and by extension he himself – would have been suspected of ‘deviance’ if there had not been a layer of plausible deniability in the shape of a wife.

And there you have it: the central problem of Mary Morstan/Watson, in both ACD canon and BBC Sherlock – she shoots Sherlock in the heart – or does she save his life? Look at ACD canon again. Does Mary Morstan’s engagement to John Watson hurt Sherlock Holmes, to the point that he replies, at the end of SIGN, “For me, …there still remains the cocaine-bottle”? Or does Mary Watson save his life? In the nineteenth century, suspicion of a romance between Sherlock Holmes and John Watson could have meant imprisonment or even hanging; many men suspected or accused of same-sex relationships chose suicide rather than total disgrace. Mary Watson’s presence provides Holmes and Watson with a lifesaving alibi.

Let’s have a look at this against the criteria for a ‘re-visionary fiction’:

Challenges the idea that Watson ‘told things as they really were’ – instead, it introduces the idea that Watson deliberately obscured the facts of his and Holmes’ partnership

Keeps the pre-text Mary Morstan constantly in view – a startling contrast, which rather effectively comments on the position of both women and queer people in the nineteenth and twenty-first centuries

Enables us to abandon our “restricted and conventional ways” of reading the original – if it makes no sense for Mrs Watson to have existed in ACD canon, then the reader must radically reconsider Holmes and Watson’s relationship; no longer ‘just’ a friendship, but a lifetime’s commitment, as close and loving as a marriage. BBC Sherlock encourages this re-visioning by setting Mary up as a rival to Sherlock; by having her attempt to get rid of him; by highlighting that she both kills and saves him. It re-casts Sherlock Holmes as the dominant romance of John Watson’s life, in every version.

It causes us to see parallels and contrasts between the two time periods: the societal homophobia that made Mrs Watson a necessity in ACD canon has largely gone in modern Britain. But BBC Sherlock hints at a profoundly closeted bisexual John Watson who strives after a ‘normal’ wife who “wasn’t meant to be like that”. The continued presence of a Mrs Watson very effectively shows us that societal attitudes are not as profoundly different as we may think.

BBC Sherlock shows us how the existence of a Mrs Watson has been written not only into the [hi]story of Sherlock Holmes and John Watson, but into the fabric of society: Sherlock Holmes is a great man, but God forbid he should also be a happy, human man, in a loving relationship with another man. The cultural script has been written: the great figures are either straight, or they are nothing. There is always a wife.

As discussed above, the presence of Mrs Watson is also important politically and culturally. It draws attention to the total lack of agency for nineteenth-century women, and to the restrictive narratives imposed on female characters in today’s culture. It makes terribly clear the extent and dangerousness of the homophobia in nineteenth-century Britain. It highlights the fact that there are still countries today where people are forced to hide their sexualities for fear of being imprisoned or killed.

The Watson baby:

In BBC Sherlock, the woman we know as Mary Morstan is revealed to be pregnant on the Watsons’ wedding day. In ACD canon, Watson never mentions a child from his marriage. In Holmesian speculation, plenty of children have been suggested for Watson, especially since it is often posited that he must have had more than one marriage (that Watson might be infertile is not something the proponents of the ‘Three Continents Watson’ school of thought often like to suggest).

As a re-visionary fiction, then, BBC Sherlock forces us to examine the source text: in a time when reliable contraceptive methods were virtually non-existent, why did John Watson and his wife never have a child?

The options, broadly, are:

Mrs Watson was infertile (if Watson only had one wife)

Watson was infertile (if he had more than one wife)

They didn’t have sex, either due to ignorance (but Watson was a doctor…) or reluctance

Mrs Watson only ‘existed’ because societal homophobia made her a necessity (see above).

John Watson:

In Series 4 of BBC Sherlock, John behaves in an unrecognisable manner: he beats Sherlock bloody, so that his eye is still bloodshot some little time later. This is said to be due to the pain of losing his wife, and the fact that her death is Sherlock’s ‘fault’.

Viewed as re-visionary fiction, as metafiction, BBC Sherlock here satirises the idea of the ‘deutero-Watson’ which has existed since Ronald Knox wrote his Studies in the Literature of Sherlock Holmes. It also, however, critically examines the fact that, in ACD canon, there are (at least) ‘two Watsons’: one, the narrator, seemingly the most reliable and loyal of fellows, straight (in all senses) and true, good in a fight; and a second, the ‘true’ John Watson behind the narration, the man we discern when we look beyond the surface of the tales. A man who is devoted, above all, to Holmes; prepared to adopt Holmes’ habit of ‘compounding a felony’ to follow the idea of justice as opposed to law; prepared, in fact, to break the law if Holmes thinks it right; prepared to abandon his wife at a moment’s notice, when Holmes calls; prepared to alter all kinds of details in his stories to protect their participants. (Also, presumably, a bit of a joke about the accidental ‘dual personality’ that ACD gave his Watson by naming him James and John on different occasions.)

Looking at ACD canon through the lens of BBC Sherlock, the entirely unreliable nature of Watson as a narrator comes to light, but the enduring feature of his stories – his love for, and loyalty to Holmes – provides the obvious answer to why he should be so unreliable. Watson may be ‘two people’, but he lies, he breaks the law, he abandons his wife and his patients for only one person: Holmes.

Ultimately, the reader understands that they have been lied to, because the truth would have been impossible to tell at the time ACD was writing. Famously, the final story in the Sherlock Holmes canon, The Adventure of the Retired Colourman, ends with the words, “some day the true story may be told.”

If BBC Sherlock is seen as re-visionary fiction, Series 4 of the programme becomes a representation of the artificiality of the construct that we think of as BBC Sherlock and – viewed through its lens – ACD canon becomes visible as an equally artificial construct, filtered through the writings of an unreliable narrator and governed by the societal and cultural imperatives and prejudices of its time.

Every trick has been employed in Series 4 to highlight its artificiality: lack of coherent structure, temporal uncertainty, incoherent character arcs, introduction of a deus ex machina character, fluctuations of genre, and members of the crew actually appearing on screen. Just as in Hawksmoor, the ‘case’ of Series 4 defies solution. BBC Sherlock and Hawksmoor are both postmodern detective fictions. We have been told that this is ‘a show about a detective, not a detective show’. The form of the show, like the form of the traditional detective novel, leads us to expect a neat, tidy ending, explained carefully by an all-knowing figure of authority. The makers of BBC Sherlock, however, have done everything they can to pantomime a lack of care for, or understanding of, their own show. They have simultaneously inserted themselves into the story (Mark/Mycroft; giving varying accounts of when/how Series 4 was written; lying and saying that they lie) and withdrawn the ‘grand narrative’, the fiction of the omniscient narrator.

Why?

For over a century, ACD canon has been read in the same way: as the most archetypally logical detective story available to us. The fact that the canon is a huge mess of inconsistencies, requiring the collective effort of thousands of people to pick away at, is typically explained by the idea of an omniscient but uncaring storyteller: Arthur Conan Doyle.

This is particularly ironic for a fandom which supposedly wishes to disavow the existence of an author at all.

And yet, the problem is, if you don’t slip into extra-universe speculations on ACD’s attitude to Sherlock Holmes, you have to face head-on the conclusion that Watson is a very, very unreliable narrator indeed.

And you have to face why.

@devoursjohnlock @garkgatiss @221bloodnun @tjlcisthenewsexy @may-shepard

#sherlock meta#hawksmoor#bbc sherlock#acd canon#historiographic metafiction#postmodern detective fiction#hawksmoor17

409 notes

·

View notes

Text

Research Proposal Final Draft

Title

Evil Kweens: A Queer Look at the History of Villains and Monsters in Animation and Film.

Report Type

Extended essay.

Proposed Table of Contents

Historical context and background

the Hays Code and its influence on the content of almost every American film made between 1930 and 1966

How were things back then?

Queer-coding and Queer-baiting with Focus on Modern Media

both are issues for the LGBTQIA+ community as they seek to capitalize on these marginalized groups.

Queer-baiting: portraying an obviously queer relationships with the use of cues and subtext without acknowledging it or perhaps even gas lighting it.

Queer-coding: writing a character with queer stereotypes as a form of representation without explicitly acknowledging that the character is queer.

Intent matters but a piece of queer media made with bad intentions could actullay end up having a good effect or be good for the community whilst the reverse could also happen.

Disney villains

Lycanthropy and Other Monstrous Subtext/ Parallels. Allegory or Myth?

talk about werewolves (Teen Wolf, Harry Potter, Buffy)

Frankenstein (Mary Shelly, Rocky Horror Picture Show)

Question

Is representation of LGBT individuals in animation and other forms of entertaining media good for the community or just a way for corporate big wigs to swindle money from hopeful queer people who would pay to see at least one shred of a character who is like them?

Limitations

it may be hard for me to stay objective given that I’m in the LGBT community myself.

Risk of outdated sources and temporal context problems. A project of its time will certainly play a part but more importantly the LGBT community is quite fickle it changes a lot as new identities and constructs get introduced so it may be hard to find a viable source.

I could possibly run the risk of getting distracted or going off on tangents which lack focus but I think this is partly because there is a lot about this subject so there is a lot to go on.

Background

The Hays code was published in 1930 and was based on three general principles:

No picture shall be produced that will lower the moral standards of those who see it. Hence the sympathy of the audience should never be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil or sin.

Correct standards of life, subject only to the requirements of drama entertainment, shall be presented.

Law, natural or human, shall not be included, nor shall sympathy be created for its violation.

These were developed in a series of rules grouped under the self-explanatory headings Crimes Against The Law, Sex, Vulgarity, Obscenity, Profanity, Costume Dances (I.e. suggestive movements), Religion, Locations (I.e. the bedroom) National Feelings, Titles and Repellent Subjects'' (extremely graphic violence).

Typical Features of Queer- Coded Characters

high cheekbones

thin bodies

feminine beauty

dramatic of voice and actions

male characters may talk or sing in falsetto or have a camp voice and a female character will most likely have a deeper voice (Maleficent, Evil Queen, Ursula- who is actually based on the drag queen Divine)

these characters may also drag out their words and walk about as though slinking (Scar, the Lion King)

Examples or queer-baiting

Myka Bering and H.G. Wells (Warehouse13, SYFY)

Sherlock and John Watson ( Sherlock, BBC)

Captain America and Bucky Barnes (MCU)

Spock and Kirk ( Star Trek, NBC)

Stiles and Derek ‘Sterek’ (Teen Wolf, MTV)

Merlin and Arthur ‘Merthur’ (Merlin, BBC)

Dean and Castiel (Supernatural, ABC)

Lycanthropy

seems to be synonymous with the homosexuality- parallels between teen Wolf and Buffy the vampire slayer’s respective coming out scenes

The Queer-ness of Professor Lupin from the Harry Potter Franchise- J.K Rowling has admitted that Lupins Lycanthropy is a metaphor for AIDS/ HIV but has further dismissed fans’ theories that Lupin is Queer.