#neurotype-based psychoanalysis

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

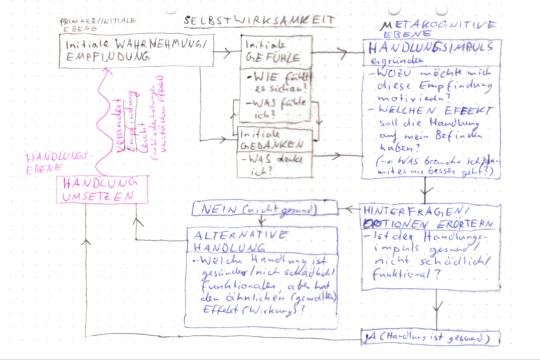

Emergence of personality - this is my attempt to depict 'personality' as a sort of dynamical system, offering emergent properties...

What is a personality?

Personality is the 'form of self' - it is a collection of character attributes, to summarize it simply. Furtherly, the form of self is characterized by patterns in perception, thought and feeling.

The form of self goes hand-in-hand with the 'function of self': behavior.

[I think this perspective is similar to Jung's ideas on Triebe/drive. ]

Starting from here I try to translate these concepts into some sort of algorithms.

[Theoretical stuff: ]

[Practical stuff: ]

#psychoanalysis#generalized conceptions of psychoanalysis#neurotype-based psychoanalysis#neurodivergent trauma#trauma-altered brain#psychology#psych#personality#personality development#structural dissociation#ego states#adverse childhood experiences#trauma healing#trauma research#psych and math#math#mathematics#emergence#emergent personality#dynamical systems

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think Light and L are a decent illustration of why the "high functioning" label doesn't work as a way to categorize autistic people* (with the important caveat that they are fictional characters, neither of which are canonically autistic). Spoilers for Death Note.

Light (operating under the theory that he is autistic) would definitely be labeled as high functioning: he does well in school, could hold down a job, date, live on his own, and most importantly he can Act Normal (aka he masks really well). But the second important reason that he'd fit the label is that he wants to. He tries hard to blend in and be successful and function well according to neurotypical standards. The ability to do this is one thing and willingness to do it is another.**

Enter L. He is highly intelligent, skilled at deception and psychoanalysis, and has an interest in observing other people's behavior. I think that if he wanted to, he could very well pass as neurotypical and therefore earn the label high-functioning (because let's be honest, that's what it really means). But he simply doesn't give a shit. People would call him "noticeably autistic" or "socially impaired" instead. Not because he is necessarily impacted by his autistic traits more, but because he doesn't actively work to hide his autism from others.

This means that Light doesn't get the support he clearly needs for his mental health, is unable to form genuine close relationships, and is bored and unfulfilled by the neurotypical success he chases. It also means that L is underestimated, not taken seriously by co-workers, and babied by his guardian. Making assumptions about people's support needs based on how thoroughly they are masking is harmful. In the case of Death Note, it leads indirectly to mass murder and the untimely death of everyone involved haha.

---

* If this is the first you've heard of it, I recommend doing some research on the problems with high/low functioning labels elsewhere before worrying about this post, it's kinda a bad first-time explanation haha.

** Important note that inability to mask effectively isn't an indicator of worth, and people who can't pass as neurotypical and/or get labeled as "low functioning" shouldn't be belittled either.

#i guess this is a slightly more serious post#i hope it offends no one#but if so someone please correct me#death note#l lawilet#light yagami#autism headcanon#autism

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Objects Without Objectivity

When posing notions of “objectivity” in regard to a divide between sorts of knowledge, the “subjective” often ascribed to experience, to the private and moreover in collapsing such knowledges as unable to expand beyond the private, while expanding objectivity to a point of the absolute, to a point wherein objective knowledge effectively constitutes a system of uncovering an already known object, one finds that the structural apparatuses by which subjectivity and objectivity are marked, are made into categories of knowledges, that there is an effectively reactionary notion of what each can and moreover must as a result constitute, that the two are opposed and that one can in fact overinscribe upon the other. In questioning and moreover doubting the turn toward subjectivity that is implied by postmodernism, by phenomenology, by existentialism, one finds a devaluation of the subjective in favor of a turn that mirrors the codification of psychoanalysis into psychiatry and psychology, only begrudgingly appropriating the phenomenological through the apparatus of neuroscience, quite literally an attempt at creating an object of subjectivity through conceptual and largely functionalist accounts of what experience must constitute and how it is constituted. That these notions of objectivity are so often transferred onto fictions-of-fact, fictions that rely upon the structure of the scientific, the violent acts of collapsing seen in creating a politics of objectivity, should be worrying to any leftist, no matter how much one rejects the apparent disparities between postmodern politics and postmodern thought.

Largely, the notion of the “scientific” is used in order to reckon objectivity: a closed system is created with known and controlled variables, and the result is an objective result that constitutes a scientific knowledge, or at the very least an objective result given the circumstances of what is knowable and known, or what is not known and known not to be known. The specific limitations and structural deficiencies of the apparatuses (both in the sense of objects and the sense of apparatuses of interpretation) given to a certain experiment are indeed largely accounted for by any decent scientific experiment, and while I will not be one to defend scientists from critiques they should be more than willing to hear, I will at the least acknowledge their ability to reckon these limitations is itself based upon assemblages of knowledge about their craft, and that correcting for these arbitrations within their results is part of how they come to what they would recognize as a meaningful result in the first place. In an experiment where, given friction that is necessarily created within the working of the device that they are using to measure a finding, given the use of “significant figures” as part of determining the scale at which one can meaningfully assign a value to a given variable (with that beyond the significant figure effectively considered as a sort of waste data, an unquantifiable quantity) that there is a plain display of subjectivity even during the process of reckoning with the creation of “objective” thought. Moreover, that any given variable is merely a sort of small, localized hyperobject, requiring the interpretation of an assemblage of structures (both of inclusion and preclusion) is necessary to the very epistemic structure of the experiment, as it were.

This is not simply confined to the means by which “scientific” is used to describe certain epistemologies of objects and certain fields of knowledge within divisions of coming toward a theoretical framework of experience: the very means by which a “scientific” Marxism is understood must be one with a strong affirmation of the subjective specifically because objectivity, the structures of supposed objectivity in place, are so largely overdetermined by hegemonic influence that, in order to find the “history of class struggle” that is described by Marxist thought, one must effectively accept the subjective not merely as its own sort of knowledge, but rather must understand subjectivity as a means of relating knowledges outside of the hegemonic structures that allow for their preservation. The way in which a supposed “objective” is in fact a subjective relationship to an object of bourgeoisie control, to the arrangement of bourgeoisie structures of encounter and experience, is absolutely vital to the understanding of larger structures of experience through which one may argue for a historical understanding. Texts such as Settlers, ones that are certainly of a different sort than most postmodernist texts, rely upon this subjectivity specifically because the truth, the historical, is what Badiou describes in Philosophy for Militants as a sort of fiction, as a process of understanding that the demarcations of truth are themselves fictive in quality not as a means of disposing of that which is arbitrated by “truth” but rather as part of arguing for a certain understanding of what truth may constitute, how truth is supposedly formed, the generative aspect of knowledges when understood in community, outside of the individualized and instantly communicable totality imposed by concepts of objectivity.

The ironic turn of objective demarcations is that they retain a privileging of the individual observer without actually critically examining the nature of such observation. Instead, they rely upon a totality of the individual as having a special access to the world as objective, to an account of placing objects into objectively verified structures of understanding, of sorting them based upon natural laws rather than structures of convention. This is used in order to create the psychiatric as a series of structures, and moreover repeated in the conflation of anti-psychiatry with movements that are mere substitute psychiatry, that attempt to illustrate a vitally psychiatric structure of conscious experience, but in doing so completely ignore any meaningful arbitration of phenomenological experience. Anti-psychiatry, as understood through the work of Foucault, of Deleuze and Guattari, through the predominant critics in any meaningful understanding of the anti-psychiatry movement, does not seek to simply rename experience or reappropriate it into structural evidence of demons, whether these demons be a term illustrative of the ills of modernism or an entry into eschatological inquiries through a sort of demonology of the subject. Rather, anti-psychiatry involves the creation of theory of rhizomal assemblages of experience that go far beyond the psychiatric labels at hand.

When these labels are misapplied, are used in a pathologizing fashion, those looking to at least use the structure of these labels as a means of asserting a certain necessary ground for survival, for comfort of experience, are often given the reassurance that their experience is in fact normal, that it is what an illusory “everyone” experiences. While this is a frustrating means by which experience is sanitized, the creation of “neurotypical” experiences is codified, it can be reversed, turned in a Derridean fashion into supporting the claim that everyone in some way exhibits symptoms of ADHD, of Autism, of depression or anxiety or schizophrenia. The very specific means by which schizophrenic affinities are used to describe postmodernism by Deleuze and Guattari do not demean those who are diagnosed with schizophrenia, but rather use the structural presence of this label in order to unite experiences differentiated by arboreal, hierarchical models of understanding (ones of objectivity) across a sort of hyperobject of experience, a collection of understandings connected rhizomally. The means by which communities of those diagnosed with ADHD/ADD and Autistic people have been finding community, discussing the commonality of their experiences and developing from the supposed-objective of psychiatric labels and their apparent commonality into a larger means of discussing the structure of experience as similar, as specifically exacerbated and made-violent by structures of capitalist productivity, the figuration of the multitasker as a sort of shamanistic channeler of a productive ADHD, or the continual appropriation of notions of Autism as producing a savant-like figure continually seen in popular culture is not based in the same restructuring of subjectivity that attempts to reclaim pathological experiences as seen in the use of schizophrenia as a concept in opposition to colonized traditions and colonial demarcations of potential-subjectivity. Even with the “objective” presence of schizophrenia, rightfully there are discussions which argue that it can be interpreted as a specifically insightful, a specifically differentiated means of experience and that the structures of “treatment” imposed by psychiatric violence are in fact ignorant of the very subjectivities they claim to treat.

That these responses anticipate and are anticipated by Deleuze and Guattari’s employment of schizophrenia, the sort of specific reversal required to take the Orientalist figuration of the shaman or fortune-teller and reject its structure while instead arguing for a new subjective structure of describing schizophrenic experience is part of a decolonization of the neuroscape, of the topology of the mind, that is mirrored in conversations around the overlap between anticapitalism and meaningful development of lives not marked by the violence of pathological psychiatry, psychiatry that only enters into an encounter through that violent demarcation. The presence of the behaviors indicated by these labels is not to be doubted, but also not to be understood as a collection of objective structures. Rather, subjectivity, the relating of these “objects” of behavior and of experience, is part of arbitrating the realization that a hyperobject of capitalist construction is determining the means by which one may realize pathology and brilliance at once, how one can create standards of acceptability through these inquiries. The notion that these are common behaviors, common experiences is important specifically because it works opposite the means by which these behaviors are so often reckoned. Instead of creating them as unique, as specifically indicative of a pathological condition, one can instead mark the pathological as an assemblage of particularly developed experiences, can mark it as the way in which creating pathology requires an exit from the subjective that is so muddily reckoned that the very separation of “objectivity” from it soon becomes irreconcilably unclear. Rather than creating a sort of apparent-positive in the notion that these pathological experiences are common, and thus not excuses for an inability to acquiesce to structures of productivity in experience under the arbitration of capitalist violence, they can be used to not only elaborate upon the means by which capitalism enacts violence according to these structures, but moreover to develop how the arbitration of these structures relies specifically on referencing a constructed paradigm rather than any meaningful apparent-objectivity. That “everyone” exhibits these symptoms but only some are pathologized implies not that there is an actual pathological structure, but rather a structure of pathologization, that it is in specifically using violence to deny commonality that one finds the creation of these apparently “objective” conditions.

The appropriation of concepts of topology and topography as linked to experience, concepts of the Virtual as a phenomenological structure, and phenomenology more generally require a means of arbitrating these structures seen in the supposed objectivity of neuroscience. This is not to say that meaningful knowledges cannot be generated by neuroscientific inquiry, but rather that they so often adopt a functionalist explanation for the phenomenological that it effectively acts as a wholesale misreading of the phenomenological structures they claim to develop, a misunderstanding of phenomenology as a whole. The roots of modern phenomenological thought in Husserl, and their development by Levinas, by Heidegger, and most importantly by Merleau-Ponty (who, tellingly, has been at the center of neruoscientific inquiries) whose role in existentialist thought is effectively erased by a misappropriated understanding of his thoughts upon the phenomenological body, the materialism from which Merleau-Ponty draws his conclusion. A cursory understanding of Merleau-Ponty’s work will show that his materialism is based in Marxist dialectical materialism as developed from Hegelian thought, but it is from a firmly analtyic and ametaphysical rather than anti-metaphyisical standpoint that these writings are interpreted. Rather than developing rhizomal potentialities from the structures of case studies found in Deleuze and Guattari’s readings of Freud, one finds a reversal, where Merleau-Ponty’s work is ascribed to a supposed objectivity of the body. The specific concentration on subjectivity within Merleau-Ponty is rejected, is taken as a mere artifact of his work. To defend this position is effectively to accept Merleau-Ponty on terms he would not recognize, the only ones on which capitalist valuations can meaningfully accept his work as implying a certain quality of experience.

When one, in these senses, attempts to quantify an “objective” understanding of structural accounts, when one acts as if there is an objectivity to be discovered rather than describing an approximated “objective” assembled from hyperobjects of thought and inquiry, one accepts a certain hegemonic, capitalist understanding of the Real that effectively denies the hyperreality of late capitalist experience, that denies the colonial nature of inquiries understood as “objective” (anthropology, psychiatry, sociology, so on) and upon all of these denies any dialectical understanding of postmodern reckoning. Even if one prefers to understand these experiences as contemporary rather than postmodern, their structural origin cannot and must not be denied, and to hold to the notion of an objective scientific process is to deny the very means by which such processes may be realized.

1 note

·

View note

Text

How being a companion has changed me

As I mentioned a post or two ago, I’m about a month away from my one year anniversary of becoming a spirit companion. I’m still not entirely sure of what I’m going to do to commemorate that, but I decided a post on how I’ve grown would be a good start.

Disclaimer: I got into companionship for the chance to make friends on the Other Side and to learn (in general). None of them were sought out to “serve” me or anything of that sort. Once in a while I’ll request things, but more often than not, when they do something for me it’s of their own accord. Also, I’m going to be very personal in this post. This is intended to be a positive look back on my growth, and therefore really not intended for criticism or psychoanalysis. If you act like a dick I will block you.

Peace. I don’t feel quite so nervous when I venture out alone. 4 hour roadtrip by myself? Chat with the companions the whole way there. Lost on the other side of town at night? Ask the companions to watch over me. Whenever I am really, truly frightened, I can sense them quite well and that helps a lot.

Confidence. So one of their vessels is a bead and another’s is a ring. The bead is bright yellow and attracted a lot of attention when I began wearing it. A lot of people asked me point blank what was up with the bead since I never took it off. I didn’t like the attention, but I refused to hide the vessel. I told everyone who asked it was a ‘blessed bead’ (as if a monk had blessed it) and left it at that. The ring was slightly trickier. Since the day it arrived, I’ve worn it on my left hand ring finger. I wear other rings, but I switch them out, and this ring is the only constant. People noticed. Here I simply told people it was my favorite ring. I stopped caring if people judged me for wearing flats with something that looked better with heels. I stopped pretending not to notice when someone condescends to me, stopped acting like I didn’t know things I knew just because my supervisor didn’t expect me to know. 2016 was the year of giving precisely -10 fucks.

Motivation. Having a job that stomps on any attempt at creativity in an environment with unhealthy expectations, my dreams have more or less died. For three years now my only goal has been to snag a better job so I can get out of this hellhole. Until that happens, my everyday life won’t improve much, but now that I’m delving into spiritwork, I’d presume that the harder I work at it, the better I’ll become. I anticipate fully awakening my third eye at the very least, and hopefully being able to travel one day. Making connections with beings in other realms has given me goals again -- not obligatory survival/work goals, but things that will actually bring some sense of accomplishment and enrichment.

Emotional stability. This has changed significantly in the past year both thanks to their efforts and my own. I am neurotypical and I'm not a spoonie but I have some very Bad Days* where I work. 8 or 9 months ago I was literally screaming internally for hours every day (work stuff, not companions‘ fault) but I had the decency to feel bad about it as far as my companions hearing it. Through the combination of taking as many days off as I could and training myself to be courteous of those now sharing headspace with me, I was gradually able to reach a point where I was no longer on the verge of a nervous breakdown. So that part I worked on myself, the part I believe my companions have helped me with is my anger. My base personality is very blunt / very “spitfire” and under stress I can be...unwelcoming. I’ve noticed over the past year that while I still have Bad Days, I don’t reach that level of shaking-with-rage quite so often.

I can honestly say I think I’m a healthier person than I was last year and I’m optimistic that this good momentum will continue. I think I’m doing hella good for an Adult™ with invisible friends.

*Bad Day: A day in which I am irrevocably pissed off to the point of being physically affected. Sometimes I get so angry that my blood pressure gets high and I get dizzy. On one particular occasion, I clenched my jaw so tightly I broke a tooth.

4 notes

·

View notes