#generalized conceptions of psychoanalysis

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

monster theory reading list

this list is going to be some recommended reading when it relates to literary teratology or monster theory. some of these works predate 'monster theory' as a concept (which was coined in 1996 by jeffrey jerome cohen) but are foundational to that work regardless.

i'll try to include links to any readings that are freely available online and links to doi etc but if something isn't and you're really keen, hit me up and y'know we'll see what i can do.

monster theory: reading culture (1996) by jeffrey jerome cohen - the original and defining text on monster theory by the man himself. here is a link to a pdf of the first chapter, which i spoke about at length in another post.

the horror reader (2000) by ken gelder (editor) - an incredibly insightful collected edition about the horror genre as a whole, however gelder's introduction to part three, as well as marie-hélene huet's chapter introduction to monstrous imagination were incredibly helpful to my work personally. very generously, gelder has allowed free access to the entire work in pdf form!

the monster theory reader (2020) by jeffrey andrew weinstock - an amazing collected edition featuring cohen, creed, kristeva and a number of others that provides a really good foundational background knowledge of what contributed to the creation of monster theory as well as some fantastic takes on it post cohen.

classic readings on monster theory (2018) by asa simon mittman & marcus hensel - similar to weinstock, this collected edition features a number of classical foundational essays and some more modern ones surrounding monster theory. a very helpful starting point! here is a link to the introductory chapter by mittman and hensel in pdf form!

the monstrous feminine: film, feminism, psychoanalysis (1993) by barbara creed - creed's idea of the monstrous feminine is one of the foundational underpinnings of monster theory and is key in comprehending the 'other' as monstrous, particularly as it relates to women in a patriarchal society. highly recommend! here is the entire book in pdf form!

powers of horror: an essay on abjection (1982) by julia kristeva - kristeva's idea of abjection is a precursor to a lot of theoretical frameworks regarding the horror genre, in particular as a direct precursor to creed's work, then to cohen's work. here is the entire book in pdf form!

this is definitely not an all encompassing list of sources, but it is a good starting point for anyone interested in this particular niche field of literary theory. these are texts that were crucial for me in understanding the basics when i was starting work on my thesis.

#monsteracademia#monster theory#jeffrey jerome cohen#barbara creed#julia kristeva#ken gelder#jeffrey andrew weinstock#literary theory#literary teratology#monster theory 101

604 notes

·

View notes

Note

what's your take on psychoanalysis

it's extremely unserious when people try to separate out psychoanalysis from other psychiatric practices eg in antipsych critique -- psychoanalysis isn't any 'nicer' or milder than eg medication therapy or ect or anything else, generally and historically these approaches are all used in conjunction. often the goal is specifically to administer medication in order to make the patient receptive (vulnerable) to psychoanalysis, or more rarely vice versa. even if you hypothetically found a practitioner who only used psychoanalysis we're talking about the same profession with the same goal of making you normal, compliant, and economically productive; it's the same system and serves the same function, the only difference is some practitioners are more loyal to one or another specific form of intervention. so when i talk about psychiatry and antipsychiatry i am including talk therapy, 'moral cures,' psychodynamic/psychoanalytic approaches, etc, even tho they usually aren't my main rhetorical focus.

on like a personal recreational level i have other interests in some psychoanalytic theories and i think there are philosophical and epistemological axioms to them that can potentially be much more fruitful than current ruling therapeutic ontologies when we're talking about something like broad-strokes cultural criticism or literary analysis. but this is really its own phenomenon of vaguely similar concepts in very different material contexts & deployed to answer fundamentally different questions.

71 notes

·

View notes

Note

Im doing a project about disinformation (specifically pseudoscience) and I've found a great paper that is trying to define pseudoscience by one common characteristic.

"Boudry and Braeckman (2011) have distinguished between ‘immunizing strategies’ and ‘epistemic defense mechanisms’, documenting how these appear in various guises in practically every pseudoscience (the relationship with Popper’s “conventionalist stratagems” will be discussed in 4.1). Immunizing strategies are defined as generic arguments or tactics that serve to protect a belief system from critical scrutiny and adverse evidence, while defense mechanisms refer to the special cases in which the immunizing tactics form an integral part of the belief system itself. (...) In many pseudoscience, core concepts are either ambiguous and amenable to a range of interpretations, or they are retrospectively redefined whenever threatened with refutation. Such strategic vagueness is characteristic of creationism and Intelligent Design theory, astrology, Freudian psychoanalysis, graphology, homeopathy, and various forms of alternative medicine." - Diagnosing Pseudoscience – by Getting Rid of the Demarcation Problem, Maarten Boudry

I just thought it might be relevant in your fight against astrology/anti-science crowd. Science doesn't try to immunize itself against scrutiny, only pseudo-science does.

I want to be so clear here that I do pretty vigorously disagree with the notion that everyone working in the sciences is a noble intellectual who's always open to new data and loves being proven wrong. anyone can be a shithead and I never made the claim that every psychologist in the world is a beacon of perfect, unbiased research and is above reproach. of COURSE some scientists try to immunize themselves against scrutiny, for any number of reasons including biased ones because people in any field can be real shitheads who 100% let their own bigotries color their work. that of course includes psychologists, given that psychologists are human and therefore fallible.

my stance is not and has never been "psychology is superior to astrology because it's an academically unblemished field of study," it's "psychology is more credible than astrology because it's a.) a field of study that is at least held to some standards and b.) dedicated to studying something that demonstrably has an effect on human behavior, unlike planetary movements."

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

A psychoanalytical reading of Lost Days and Under the Hood, because I hate myself and hate Freud even more

*bracing myself to talk shit* Okay, let's do this. Last warning to back off if you like psychoanalysis or even have a nuanced take on this. This is the graveyard where nuance comes to die.

First thing first, this is not intended to be an attack on Judd Winick: I do not know if he has actually read anything on psychoanalysis, and though it would make so much sense if it were intentional, it could totally be that Winick had passing knowledge of psychoanalysis from a source similar to one my short-form tumblr shitposts and other general pop culture information, thought "huh, neat, I always thought manipulative hot MILF Talia was a cool concept" and ran with it. Or that any other thought process went into it. I am extremely critical of the decisions he has made in his portrayal of mental illness and Talia specifically, but I'm not gonna criticise him on the assumption that it was psychoanalytical. I say this because the rest of this post is gonna sound like I think it was on purpose: I think it could, but I don't think I have enough knowledge about Judd Winick and enough clarity in the text to be crystal clear that this is what directed his writing (unless I missed one Easter egg in the back of an image, that would be very fun.) I'm also not gonna make fun of Winick for writing psychoanalysis fiction if he did do it on purpose, because so did I when I was a misguided highschooler, and many therapists have not gotten past that phase despite dedicating their life to it so there's no judgement on that part. With that being said, I think it's a super valid reading, so let's talk about this. Also, I'll talk a lot about Freud because he's the founding father of this shit, but there are many other psychoanalysts who came after him, all putting their own brick in the wall; all of them are wrong, but many are more moderate and do not have the extraordinary audacity of the first culprit.

#dc#jason todd#jason todd meta#the jason Todd psychological analysis meta#red hood#red hood lost days#under the red hood#dc comics#anti psychoanalysis#anti freud#batman

75 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi!! sorry if this is odd or too much to ask but im trying to engage with more philosophy in general (like outside of an academic context) and i was wondering 1. whether you've found lacan's work to be especially relevant currently 2. if you'd recommend starting with his works. hope youre doing well

sorry ive sat on this for a bit but i am not any kind of authority on lacan! i know nothing! i just like his work and the people that like his work.

but for the record, lacanians have done great work exploring ideas of race, gender, sex, love, hate, propaganda, relationships, religion, communism, fascism, death, desire, the good life, all sorts of things. though i generally think one can basically do anything with theory by way of good interpretation, i think lacanian psychoanalysis is particularly powerful in explaining anything involving subjectivity and the social.

the problem with lacan is not only that he is both building off of and reinterpreting freud--meaning at least a little background knowledge of freudian psychoanalysis is good--lacan also evolves over his career, sometimes contradicting, forgetting, and reappraising his own past ideas. he's often split into "early" and "late" periods because of this, giving his concepts multiple varied-but-related definitions. he's also well-known for introducing incredibly potent one-off concepts and then never returning to them.

basically i recommend (specifically now, but also in general) you listen to ryan engley and todd mcgowan's podcast suggesting where to start with psychoanalytic theorists: https://pod.link/1299863834/episode/7010a7ca97127b644d219534d7c2b59b these two are, as you will hear, much more deep in their knowledge of lacan than whatever tidepool i wade in.

hope that helps. sorry that im basically saying "listen to some experts" but, i mean, that's the best kind of recommendation, isn't it

52 notes

·

View notes

Note

This might be too broad of a question and sorry if it is (also sorry if it's been asked before?), but I wanted to ask if there are any particular books you may recommend to someone learning about psychology?

Also what did Rosmontis do if I may ask

Rosmontis: here.

Psychology: I personally recommend learning about second-order cybernetics, in which the observer is circularly and intimately involved with/connected to the observed. The observer is no longer neutral and detached, and plays an active role in system. This is key to Brofenbrenner’s Ecological Model. Basically, this stands conceptually opposite to the Lacanian take on Freud’s psychoanalysis, as Lacanian purists will insist you exist as an extraneous entity to the focal point being observed. You, as a psychologist, are still human and a mutable, mutation-inflicting aspect of any life you wander into. The psychologist as an outside-above observer is a flawed concept in my opinion.

All this prelude is to say: Read Ludwig von Bertalanffy’s “Organismic Psychology and Systems Theory”, 1966, and get to know the General Systems Theory. One cannot work with one part of a system, micro or macro, if one hopes to truly help someone. What people often call “illness” tends to be symptoms of something else, and each person is a whole world.

Specifically about working with kids, I like Donald Winnicott’s works. “Playing and Reality”. Winnicott puts lots of emphasis on how creativity and play are incredibly good tools in understanding and communicating with babies and children, and this can and should be used alongside other techniques to create a platform of conversation, if needed, with older kids that for one reason or another struggle with conventional communication. Winnicott also proposes the “Good Enough Mother” theory, which is to say, the best parent/caretaker is one who is good enough to healthily provide for the kid in all areas, and still messes up or lacks some skills overall to provide children a safe, controlled space of adversity; it is through this safe adversity that children learn to be self-sufficient by learning to make up for what the caretaker lacks or doesn’t do perfectly. Overprotective parents, then, run counter to healthy development of the child, something that proves right more often than not.

Finally, Humberto Maturana’s “The Tree of Knowledge: The Biological Roots of Human Understanding”. This is also about second-order cybernetics, more focused on how we learn, the science of knowing how we know. You know how someone telling you “two plus two is four” is meaningless, but if you add two and two, you get four, and now that has any meaning to you because you got to that realization through internal processes that organically lead to the answer? Ok, you know how it does jack shit to tell a depressed person to think happy thoughts, but if lived experience and rationale eventually leads you to “life is worth living”, then that a life-changing effect on you? Well, it’s got to do with techniques on understanding this process and being an active agent in doing this with others.

I dislike psychoanalysis but it is worth reading Freud’s stuff, especially to understand where all of this comes from originally, and the technique isn’t necessarily bad as much as it was a technique used in a place and time that is not where and when we currently live. Second-order cybernetics is something I especially like in psychology, because of how closely it relates to actual lived experience. A simple example is, if you throw a basketball to the hoop, you likely will miss, but your second attempt will be closer, and the third attempt, you’ll likely nail it. This is because the previous attempts have given you input and information that you then incorporate to throw more accurately. This is first-order cybernetics as you are the sole, individual variable, but imagine you have a coach, and the coach isn’t teaching you in a way that helps. The coach then changes their approach to suit your way of learning how to handle the element (ball), so the observed system (you, ball, act of throwing, hoop) is now changing, but so is the system observing entity (coach), as observer cannot be separate from observed system if aiming to meaningfully change it.

These should set you out to a good start, in my opinion.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anger is Humanity: An Analysis on Andre Kriegman

Disclaimer: This analysis is limited only to commentary and analysis as a means to reflect and understand the characters and the internal and external factors that affect their decisions and actions, this is true rationality. Just like all of my posts, I am detached from the media I write about and solely focus on the characters to understand their backgrounds and psychology, for others to gain insight. There is no room for me to romanticize anything I write because I am only here to explain in my understanding. Thank you.

Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression, and Acceptance.

There are five stages of grief—yet some find themselves perpetually stuck and fixated on the second. It is a never-ending loop due to the fear of experiencing discomfort once the light is found; it is the fear of change, the bargaining of reality, the depression in the recurrence, and the acceptance that misfortune runs in your veins. One is not born with misfortune but rather handed with it.

THE SUPEREGO. A concept based on the Freudian principles of psychoanalysis, which generally develops through the internalization of values and norms given by primary groups (family and society). If members of these groups are either overly strict and abusive or lacking guidance, poor superego is molded. The superego controls the id's basic desires by using the ego, relying on internalized moral ideals. If the superego is underdeveloped, then there is an impairment in moral reasoning and the ability to distinguish what is morally just and unjust. Furthermore, factors such as abusive environments also play a role in hindering normal superego development. Negative consequences are also brought by exposure to violence or alienation.

With this, we view Andre Kriegman in a new light.

His behavior might be the result of an imbalance where his id's destructive desires aren't properly controlled by a strong superego. Freud has also noted various defense mechanisms the ego uses to handle conflicts between the id, superego, and external reality. If Andre's superego isn't functioning well, he might depend on unhealthy defense mechanisms like projection and blaming others for his indecent thoughts or rationalization by justifying his harmful behavior with logical reasoning.

Anger does not come from evil, but it comes from the mistreatment you receive.

It is the pain inflicted on you, the misfortune that leads you to believe that there is no possibility of ever finding the room to grow and move on. The reason why Andre is so fixated on hatred and anger is that it is a defense mechanism born out of the tragic reality that he has been and is hurt. It is the trauma response that begs to cling on you because you fear that in change, more misfortune will arise.

Anger—that is Andre Kriegman. In a world where you have constantly been alienated, you feel less human. You are not perceived, therefore, you do not exist. You are stripped away from whatever humanity you have, because to be a human, you must exist. You are a mere entity, an omnipresent being that is everywhere yet nowhere, all at once. Forced to watch a crowd interact, fearing and knowing you are so easy to be disregarded. You try to imitate them when interacting to be deemed more human, yet alas, all subside suddenly when you are deemed as a deviant. You are isolated, believed to be nothing, and therefore, gone.

Anger sprouts from injustice. This is the rationality in anger—even how disproportionate it feels, like how Andre feels his anger. It is rooted in the lack of good treatment. The hate you feel is disproportionate as if your body begs to regurgitate all the hate you have and project it to anyone else—your family, your peers, and even yourself. You have this strong want to let others feel the pain you feel and bear, simply because this is the part of you that yearns and begs to be seen. To be understood, to be empathized with, to feel human, to be human.

To be treated as you should've been treated—well.

Anger is human. It is a part of humanity itself. Yet, as true as it can be, you can never heal with the same thing that caused it. Pain does not heal pain and anger does not heal anger, that is reality.

Andre Kriegman is anger, he is a reflection of humanity itself and the humanity he was shown. Humanity is anger.

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

i have to be able to compare things to other things to understand them. if i am faced with something, i have to conceptualise it in terms i can understand.

sometimes it’s as mundane as thinking of desire as a form of hunger. taking a hard to pin down concept that mostly takes place in the mind and turning it into something concrete and physical.

but it often goes further. i like to analyze things and i’m really into literary theory and criticism, so i often view things through those modes.

ex:

there are differences between desire and hunger. the biggest being desire often won’t kill you while hunger will. but the metaphor gets across a basic idea, you want you need you long for your crave you yearn.

once you’ve set up the metaphor, it’s easy to come up with theories about the concept in question.

-hunger is caused by a lack of; it is a vacuum. you need, because you are empty. does desire come from a similar place?

-hunger is a thing that can be satiated. can desire be satiated as well? and if you need to eat to cure hunger, what kind of consumption is required for which kinds of desire?

-hunger evolved as a way to alert animals that they had to eat so that they could keep themselves alive. do desires come from a similar place?

etc

not to say any of these theories are correct, but they could be. honestly, it’s less a matter of truth and more a matter of perspective.

i feel like where a lot of psychoanalysis tends to fail is that they are searching for universal truths about the mind while often not realizing how much their own perspective is tinting their understanding of the mind.

i think trying to understand life is similar to analyzing literature. there are basic concepts you can use as a guide, you can attempt to explain it through existing theories and motifs and comparing one thing to another and all that. but however you end up understanding it will say more about you than it will about life itself.

i don’t personally know if life in general has innate meaning, and honestly i like the existentialist view that we give ourselves meaning. “existence precedes essence” we create ourselves, all that.

but i do think a lot of things have meanings. and it can be difficult when faced with something that has a definite meaning to figure out what the intended meaning is, and what part is my analysis brain looking for connections that aren’t there

it can cause miscommunications, especially when the references and connections between two people can vary so drastically. things can mean completely different things from one person vs the other, and there aren’t even any footnotes. they don’t even give you footnotes.

but for the most part it’s fun. i like to analyze and have theories and compare things. it’s fun extending that past literature and movies and other forms of media and into my life and psyche. but watch out… trying to analyze your mind can lead to analyzing your analysis and it becomes a whole thing.

a big appeal of literature is the connection aspect. and especially connecting paired with understanding. to compare two books to understand the themes better. to compare yourself with a book to understand yourself better. to feel understood by an author. to attempt to make yourself understood by becoming one.

i like things to make sense to me i guess is the biggest thing. and then i want to be able to make sense when trying to share my ideas and thoughts. i’m an analyser i analyse things

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

20. what's something you learned this year

While I thought I had a good grasp on personal identity theory, I was introduced to a lot of new writings on it this year. Parfit's concept of quasi-memories that I talked about here was an especially fun read, I ended up using it both in my essays and in my rpg sessions.

Otherwise some important general lessons I got these year included

An unfortunate amount of art criticism is just psychoanalysis.

While their criticism is piss, psychoanalysts write entertaining biographies.

Every famously "revolutionary" piece of art was much more an iteration of existing works than is typically acknowledged.

A great deal of writing in modern ethics involves the author assuming their audience shares some frankly bizarre intuitions.

Oh yeah that I'm not a dude. That was a pretty big one I guess

#the last one was less an “i learned this year” than “i admitted to myself this year” but yk#mals says

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Philosophy of Guilt

The philosophy of guilt examines the nature, origin, and ethical implications of guilt as a complex emotional and moral phenomenon. Guilt is a feeling of responsibility or remorse for some offense, crime, or wrong, whether real or imagined. Philosophers explore guilt in the context of morality, psychology, and existentialism, seeking to understand its role in human behavior, ethical decision-making, and the development of personal and collective identity.

Key Concepts in the Philosophy of Guilt:

Definition of Guilt:

Moral Emotion: Guilt is typically defined as an emotional response to the belief that one has violated a moral or ethical standard. It is often distinguished from related feelings like shame, which involves a negative evaluation of the self, whereas guilt involves a negative evaluation of a specific action.

Types of Guilt: Philosophers and psychologists often differentiate between different forms of guilt, such as:

Personal Guilt: Feeling responsible for one’s own actions.

Collective Guilt: Feeling guilt for actions committed by a group to which one belongs.

Existential Guilt: A more generalized feeling of guilt tied to one’s existence or perceived failings in living authentically.

Ethical Implications:

Guilt as a Moral Compass: Guilt is often seen as a mechanism that helps individuals adhere to ethical norms. It can act as a motivator for moral behavior, encouraging individuals to make amends and avoid repeating wrongful actions.

Excessive vs. Deficient Guilt: The appropriate amount of guilt is a subject of ethical debate. Excessive guilt can lead to unhealthy psychological states, while too little guilt may indicate a lack of moral sensitivity.

Philosophical Perspectives:

Kantian Ethics: In Immanuel Kant’s moral philosophy, guilt is related to the failure to adhere to one’s duty or the moral law. Kantian guilt arises from recognizing that one’s actions have violated the categorical imperative, the fundamental principle of moral duty.

Existentialism: Existentialist philosophers like Jean-Paul Sartre explore guilt in the context of freedom and responsibility. Sartre argues that guilt (or "bad faith") arises when individuals deny their freedom and responsibility by conforming to societal norms or by failing to live authentically.

Psychoanalysis: Sigmund Freud and other psychoanalytic thinkers view guilt as a product of internal conflicts, particularly between the id, ego, and superego. Freud suggests that guilt arises from the tension between instinctual desires and the internalized moral standards of society.

Guilt and Responsibility:

Moral Responsibility: Guilt is closely tied to the concept of moral responsibility. Philosophers debate whether individuals should feel guilty only for actions they directly control or also for unintended consequences and actions by others (as in collective guilt).

Legal vs. Moral Guilt: Legal systems often distinguish between legal guilt, which is determined by the law, and moral guilt, which is a personal or societal judgment based on ethical standards.

Guilt and Redemption:

Amends and Forgiveness: The philosophy of guilt also explores the processes of atonement and forgiveness. Can guilt be resolved through acts of redemption or making amends, and how do these actions influence personal and social relationships?

Religious Views: Many religions address guilt and its resolution through rituals, confession, and forgiveness. In Christianity, for example, guilt is often linked to sin, and redemption is achieved through repentance and divine forgiveness.

Psychological Aspects:

Healthy vs. Pathological Guilt: Psychologists study the impact of guilt on mental health, distinguishing between guilt that is a healthy response to wrongdoing and guilt that becomes pathological, leading to depression, anxiety, or obsessive behavior.

Guilt and Empathy: Guilt can be seen as an expression of empathy, where an individual feels guilt because they understand and internalize the harm they have caused to others.

Collective and Historical Guilt:

Collective Guilt: This concept involves feeling guilt for actions committed by a group, such as a nation or community. It raises questions about the extent to which individuals are responsible for the actions of others and the moral implications of historical injustices.

Guilt and Memory: Philosophers explore the role of guilt in collective memory and historical consciousness, particularly in the context of war crimes, genocide, and colonization.

Guilt and Identity:

Formative Role of Guilt: Guilt can play a significant role in the formation of personal and collective identity. It can shape one’s moral self-conception and influence how individuals relate to their past actions and to others.

Guilt and Self-Perception: The experience of guilt often leads to self-reflection and can influence how individuals see themselves in relation to their moral values and the expectations of society.

The philosophy of guilt offers a deep exploration of one of the most profound aspects of human emotional and moral life. By examining guilt through ethical, psychological, and existential lenses, philosophers seek to understand how this emotion influences behavior, shapes moral responsibility, and contributes to both individual and collective identity. Guilt is not only a personal experience but also a social and historical phenomenon, with significant implications for ethics, law, and culture.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#education#chatgpt#ethics#psychology#Guilt#Moral Responsibility#Ethical Emotions#Kantian Ethics#Existentialism#Collective Guilt#Psychoanalysis#Redemption#Forgiveness#Legal vs. Moral Guilt#Pathological Guilt#Historical Guilt#Guilt and Identity#Guilt and Empathy#Bad Faith

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi Caden! did you read anti oedipus, and if yes what did you think of it? you mentioned on your post about psychoanalysis being partial to this kind of approach, and i was curious if you had specific takes on deleuze, guattari, schizonalysis as a concept or its limitations?

blast from the past anti-oedipus was the first book i ever read that substantively criticised psych because i saw some people taking facile potshots at it on this very website in like 2017 and thought it sounded interesting lmao

alright so i have to be kind of broad here but essentially my opinion on psychoanalysis is that it's not, in itself, inherently liberatory or radical and certainly not inherently at odds with or even distinct from other modes of psychiatric practice. at the same time i think there are schools and elements of psychoanalytic methodology that can be those things, ie can be used to those ends by people who have those political commitments.

on here you do sometimes see this very ahistorical take à la byung-chul han that tries to understand psychoanalysis as inherently oppositional to psychopharmacology or other forms of therapy like cbt. this is really silly and fails to understand the ways in which psychiatry can and does practice pretty eclectically (because it's a very vibes based profession so it doesn't really matter). then there's the even further offshoot of this where people act like psychoanalysis has their preferred ('leftist') political character intrinsic to it, as though professional psychoanalytic organisations the world over aren't consistently on the front lines of things like medical transphobia (eg, check intellectual affilitions on the early ROGD papers; also, lacanians in france like generally). i would include schizoanalysis in this in the sense that there's nothing about it that prevents it being implemented in biased or hateful or repressive ways. its practitioners will have their own political commitments just like freudians or any other school; you can't just rely on an analysis being rhizomatic or whatever and think that solved what is a much more concrete problem of power relations and psychiatry as a tool of class suppression.

(i would extend that to scientific ideology generally but that's a longer post.)

what i do think is valuable in psychoanalysis (again now speaking very broadly of multiple sub-schools) is, and especially in comparison to other analytic models in psychology, it has a generally better capacity to deal with experiences like 'feeling at odds with yourself' or 'feeling tormented at your own thoughts'. the psychoanalytic unconscious or the process of repression of course aren't 'real' any more than the personality types or pathological entities of biopsychiatry, but the question is, are the concepts useful? i don't really align myself to a school of psychoanalysis or think it's a done endeavour but i do personally think elements of this family of approaches have real value for how we understand ourselves. this is again, though, something that in its barest scientific scaffolding will always admit of multiple & reactionary politics: for example, freud himself (and thus many many subsequent freudians) struggled with a tendency to be circumspect or sometimes openly ahistorical about the actual origins of the mental forms and archetypes he talked about (eg, the Daddy figure & its primacy in the psychological development he discussed). on the other hand, people like wilhelm reich have tried to develop this project to explicitly contextualise these elements socially and historically and materially: Daddy is in my head not because he's some universal form of human mental experience, but because of the primacy of the bourgeois marriage in capitalist social relations. etc.

so, wrt schizoanalysis and D&G particularly, my frustration frequently comes back to their failure to actually follow through on much of this. schizoanalysis is sort of an archetypal attempt to solve psychoanalysis by ideologising around the political character of psychiatry—what i mean is, the fantasy of schizoanalysis is that we can beat capitalist repression by playing what boil down to word games with it. psychoanalysis says the subject is a single 'i' and uses this conception of selfhood to achieve its economic and carceral ends (true), so schizoanalysis will evade the economics and carcerality by conceptualising selfhood as rhizomatic (unserious). i would tentatively level this more heavily at deleuze than guattari & keep meaning to do more historical reading about the latter & his actual clinical practice. but in general i do think both made (or acceded to, bc deleuze did basically all the writing as i understand it) basically silly idealist errors where anti-oedipus/a thousand plateaus shift from an analytic of capitalism to their attempt to actually formulate an alternative.

idk, it's frustrating talking psychoanalysis (on here or irl) because on the one hand you have to contend with people who think that, like, you could just reform the sex/gender discourses of lacanianism or jungianism to be more niceys to the transgenders by giving practitioners a DEI workshop. and then on the other hand you have to deal with hardcore neurobiopsych defenders who think that their fmri scans are somehow magically exempt from being theory-laden or narrativised, and that there's nothing to gain from an analytical mode that is capable of actually applying various dialectical motions rather than the crass positivism of basically all other psychiatry since like pinel. and meanwhile almost nobody in any of these camps is like, thinking clearly or honestly about the relationship between scientific ideology and political character, lmao.

tl;dr i don't think psychoanalysis will, can, or should save us & it may even be the case that no one has ever properly done it. but like yea i do think there are elements of the method that are useful for modelling our psychology, at any rate more useful than what else we've come up with thus far. and i would include schizoanalysis as under the same broad methodological umbrella, where its goal is more explicitly to grapple with politics qua psychology (libidinal investments) but it tries to do this primarily by discursive alternatives to the established form/s of the psyche—which alternatives may indeed be compatible with revolutionary politics but does not in themselves constitute such politics. As Eye Read D&G, anyway—im aware they are not the only people ever to have written about or practiced it, & aren't necessarily entitled to last word on it.

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alasdair MacIntyre

Provocative philosopher who argued that current morality has been cut off from its roots ‘largely thanks to the Enlightenment’

In 1981, the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, who has died aged 96, tore up the work he was then writing on ethics, and produced what became his best known book, After Virtue. In it, he excoriated current moral philosophy and, indeed, current morality itself, complaining that morality has been cut off from its roots in tradition, and, “largely thanks to the Enlightenment project”, has ceased to be coherent.

No longer anchored in the Aristotelian notion that humans have a goal and function, or offering an account of how these are to be fulfilled, it divorces values from facts. Although calling a person, practice or action “good” or “bad” seemingly appeals to “an objective and impersonal standard”, said MacIntyre, there is none available. As he had already lamented in Against the Self-Images of the Age (1971), Christianity, Marxism and psychoanalysis have failed to provide an adequate communal ideology.

Describing himself as “a revolutionary Aristotelian”, he was also an enthusiast for the ethics of Aristotle’s medieval follower, Thomas Aquinas. “Forward to the 13th century,” was the motto jokingly attributed to him.

But by reviving the sort of ethics that identifies “the good” with human flourishing, MacIntyre aimed to lead us out of “the new dark ages”, presumably into a better future. He influenced the resurgence of virtue ethics and communitarianism (he denied espousing either), and the now fashionable distrust of liberalism, individualism and the Enlightenment.

Remarkable for the number of conflicting beliefs that he could, often simultaneously, embrace, he was both Protestant and Marxist in the 1960s, then rejected both creeds, and, in the 80s, became a Catholic; but he always retained his Marxist disgust at capitalism and at the alienation of modernity.

MacIntyre was 52 when he wrote After Virtue. In A Short History of Ethics (1966), he had already berated contemporary analytic philosophy for examining and interpreting moral concepts “apart from their history”, and portrayed how “moral concepts change as social life changes” – from the Homeric era when to be agathos (the ideal for well-born men) was to be kingly, courageous and clever; through Aristotelian and Christian virtues, which also attuned ethics to an (albeit different) notion of essential human nature; through the Enlightenment’s uprooting insistence on autonomous reason; to 20th-century emotivism, which makes ethics merely an expression of personal preference.

In the late 70s, MacIntyre read the physicist Thomas Kuhn, who regarded scientific change as a series of “paradigm shifts” rather than a line of progress, and this gave him, if not a Damascene conversion, then a clinching certainty as to what was so grotesque about 20th-century morality: rather than being settled in a particular ethical paradigm, we operate simultaneously or alternately with several incommensurable moral traditions. “Imagine,” runs the opening of After Virtue, “that the natural sciences were to suffer the effects of a catastrophe”, that science and science teaching have been deliberately abolished, and only charred pages, disconnected scientific terms and meaningless incantations remain.

This, said MacIntyre, is our current moral situation. Like the 18th-century Polynesians who talked of “taboos” to Captain Cook but were unable to say what they meant by that term, all we have are “the fragments of a conceptual scheme, parts which now lack those contexts from which their significance is derived”. This is why we regard moral argument as “necessarily interminable”; we do not even expect to reach consensus. Should we prioritise human rights and/or the general happiness, individual choice and/or the general will, hedonism and will-to-power and/or compassion and self-abnegation?

Aristotle’s ethics in the 4th century BC had assumed that humans have a telos (function) as rational animals, said MacIntyre. Theistic beliefs – Jewish, Christian and Muslim – complicated, without essentially altering, the three-fold ethical scheme: designed to move us from “human-nature-as-it-happens-to be” via moral education and moral principles to “human-nature-as-it-could-be-if-it-realised-its-telos”. Eighteenth-century Enlightenment philosophers, however, in aiming to liberate us from superstition and authority, and to find a purely rational basis for ethics, had stripped the self of social identity and values of any claim to factual status.

Thus morality became a set of inordinate commands and, ultimately, mere “private arbitrariness”. The unembedded self – essentially “nothing” – is now obliged to choose its own values.

Admittedly, Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarianism aimed to ground ethics in the “natural” desire to avoid suffering and maximise pleasure. But “human happiness is not a unitary simple notion”, said MacIntyre, and John Stuart Mill’s distinction between higher and lower pleasures only highlighted utilitarianism’s failure to “provide us with a criterion for making our key choices”.

MacIntyre was advocating a revised Aristotelianism in which morality is, once again, not a set of abstract, autonomously selected principles but a social narrative into which our own personal narrative fits. Bernard Williams, however, called After Virtue “a brilliant nostalgic fantasy”, arguing that the socially distinct moral self, rather than being a product of the Enlightenment, was already present in Plato and Christianity.

MacIntyre’s subsequent books constituted, it was said, An Interminably Long History of Ethics, and he himself quoted this with rueful amusement. Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (1988) and Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry (1990) reiterated that analytic philosophers purport to present “the timeless form of practical reasoning”, while actually just “representing the form of practical reason specific to their own liberal individualist culture”.

It is impossible, argued MacIntyre, to adopt a moral position except from within a particular tradition. This, since he offers no way of arbitrating between them, would seem to oblige him to say that any tradition would be as good as any other, and he has been accused of being a moral relativist.

However, he said that competing traditions share some standards, so that anyone is able to apprehend problems in their own tradition and adopt rationally superior solutions from another, as Aquinas did in integrating Aristotelianism into Augustine’s theology, ultimately becoming a better Aristotelian than Aristotle himself. MacIntyre converted to Thomism and Catholicism, attending mass virtually every day, but refraining from taking communion on account of having been divorced.

Having refused to accept a concept of human nature independent of history, and of particular practices and traditions, MacIntyre ultimately extended his metaphysical grounding to include, in Dependent Rational Animals (1999), a biological one. He pointed out how the ethics of Aristotle, and later of Adam Smith, David Hume and other Enlightenment philosophers, failed to acknowledge the inevitability of suffering and dependence in human life.

Their notion of the human was, at least implicitly, a healthy male; they effectively overlooked women, enslaved people, peasants and non-Europeans. MacIntyre advocated a more inclusive idea of what it is to be human, and an acknowledgment of “our resemblances to and commonality with members of some other intelligent animal species”; dolphins, he insisted, being closely akin.

Neither the modern nation-state nor the modern family, he argued, can provide the right sort of political and social association. What would? MacIntyre sometimes alluded to the cohesive aims of tiny fishing communities and gestured at the desirability of many small utopias. He undertook a three-year research project at London Metropolitan University into whether and in what ways Aquinas’s “conception of the common good of political societies might find application in the politics of modern societies” – the result of which was his last book, Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity (2016).

Born in Glasgow, Alasdair was the son of Eneas MacIntyre and his wife, Margaret (nee Chalmers), both Scottish doctors of Irish descent. Although brought up in London and educated at Epsom college, Surrey, he was proud of his grounding in the Irish-Scottish Gaelic oral tradition. While he was studying classics at Queen Mary College, University of London (1945-49), the surrounding poverty of the East End led him to become a fervent Marxist.

His first book, Marxism: An Interpretation (1953), demanded a Marxist renewal of Christianity. Republished in a revised edition as Marxism and Christianity, it was sympathetic and sceptical about both. Even before the Hungarian uprising of 1956, he had left the Communist party, subsequently joining the Socialist Labour League, a Trotskyist group led by the notorious Gerry Healy. He was in frequent debate with the Marxist historian EP Thompson, who used to stick notes on the windscreen of MacIntyre’s car urging him to publish his thoughts on socialist consciousness.

After gaining an MA at Manchester University (1951), where he then taught the philosophy of religion, MacIntyre lectured in philosophy at Leeds University (1957-61), was a research fellow at Nuffield College, Oxford (1961-62), senior fellow at Princeton (1962-63), fellow of University College, Oxford (1963-66), and professor of sociology at Essex University (1966-70).

As dean of students there he opposed the student unrest over the summary expulsion of three students who had shouted down a speaker from Porton Down (the research site for chemical and biological warfare). “Ironically, [the university’s] mistake was to be so liberal,” he said; and declared that it was because the students had “no real practical injustices to fight against” that they “had to rebel on ideological grounds like germ warfare and Vietnam which we were powerless to alter”.

His attitude was considered disingenuous by some (after all, the university need not have invited the Porton Down speaker); to others, it was part of his characteristically contradictory and fastidiously tailored integrity. Partly due to these ructions, he moved to the US to become professor of history of ideas at Brandeis University (1970-72). He later held professorships at Boston, Vanderbilt and Duke universities, and finally at the University of Notre Dame, Indiana (1988-94 and 2000-10, then emeritus).

MacIntyre disdained the class associations of Oxbridge, and loved his involvement with London Metropolitan, where he held a post from 2010 onwards. Before speaking at a conference there in 2007, he was handed pamphlets about a students’ strike over a lecturer’s contract, and he prefaced his paper with an impromptu diatribe in support of trades unions and workers’ rights. The first to raise his hand after MacIntyre’s paper was the Socialist Worker party leader Alex Callinicos, who accused him of not being a proper revolutionary. MacIntyre replied that he didn’t know how to make a revolution, but it was clear that Callinicos didn’t either.

He leaves his third wife, Lynn Sumida Joy; his daughter Jean, from his first marriage, to Ann Peri, their other daughter, Antonia, having died in 2000; and a son and a daughter from his second marriage, to Susan Willans.

🔔 Alasdair Chalmers MacIntyre, philosopher, born 12 January 1929; died 21 May 2025

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

i would love it if you gave Benny Weir his own individual video giving your thoughts and opinions on him made in a long format because he's my crush

I will definitely do character breakdowns at some point, and I'd really like to do the whole main group (the fang gang? is that what we call them??) but I fear Benny's will not exactly be a glowing review.

He's a great character and the show wouldn't be the same without him, but the show's a little bit dated and a large part of Benny's character writing centers around some pretty misogynistic tropes.

Even so, I haven't started writing my full character analysis notes yet, so I don't know whether I will have a more positive or negative conclusion about the character. His negative personality traits stick out to me as a watcher, but character analysis also includes things like what he adds to the show. His narrative role as a magic user, as well as a support character and occasionally main character are just as important when considering whether he had a positive impact on the structure of the story, while his personality impacts things like entertainment value and his potential impact on the audience. And of course there's also a level of character psychoanalysis to be done, which generally reaches a more middling perspective on the character unless the writing was just completely awful, and that's not something I think I'd say since a lot of my concept for this channel is to assume that continuity and consistency within the show exists and trying to find it and connect the pieces.

If I do end up making videos that are more on the fluffy appreciation side than the type of wordy overanalyzing I tend to prefer, this might be in the form of a silly compilation or something, but if I ever did that I don't see it being solely about Benny, I'd want everyone in there! But who knows, maybe I'l find compilations super fun and end up making Benny special episode XP either way, that's pretty far off time-wise since most of my current plans center around what is essentially info-dumping about whatever details I take notice of.

As always, I love getting these asks, it's super encouraging to see someone excited for my upcoming projects because I'm really excited to make them, it's already been pretty fun and a good chance to develop some of my writing skills. I try not to clog the main tag by answering loads of these at once, but I read all the ones I get from you and will answer them all.

#ilovebennyweir#mbav#about the fangtasticfive#song spouts bullshit#asks <2#also feel free to use the DMs or reply section if u want to have longer dialogues about the show bc I find it really interesting

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Uh oh. I'm giving myself a headache.

For a while now, I've had a passing interest in psychoanalysis, particularly the ideas of Carl Jung.

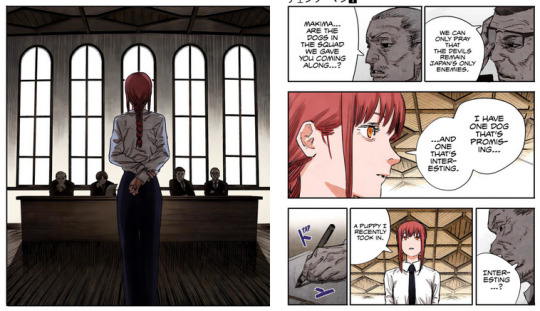

If you like Chainsaw Man, you've probably seen him namedropped here and there. The central concept of the manga, human fears personified and manifested in reality as Devils, is very reminiscent of Jung's work on archetypes, or:

universal, inherited idea, pattern of thought, or image that is present in the collective unconscious of all human beings.

Another set of ideas worked on by Jung were the Anima and Animus. Here's a quick blurb about it from https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/psychology/anima-and-animus:

The anima and animus are psychological archetypes developed by psychiatrist Carl Jung in which men and women unconsciously perceive qualities of the opposite gender in themselves. The anima is the image of the female archetype found in the male mind, while the animus is the male archetype in the female mind. Jung believed that the anima represented a man’s true feminine side and the animus a woman’s true male side. These archetypes were based on representations of the ideal man or woman found in the unconscious mind. Jung believed that the images were formed by a person’s relationship with their father or mother, family, and culture. According to Jung, these opposite elements are common in all humans and stem from the collective unconscious, a type of ancestral memory passed down through the generations.

I'm interested in focusing on the anima as it's portrayed in Part 1 of Chainsaw Man. There's one character in particular that stands out. Fujimoto has been lauded for his compelling female characters, in the likes of Quanxi, Himeno, and Kobeni in particular; but there is one that stands out, and really embodies the concept of the anima.

That's right. Once again i've been thinking hard about the eternal squatter in my mind Ma-Ma-Ma-Muh-Muh-Muh-Ma-Ma...

MAKIMA

Now, the Anima actually has several stages of realization. And our favorite civil servant traverses each of these stages in Part 1, pretty much sequentially.

This isn't a fully formed argument (yet). I'm mostly just thinking aloud; trying to form a hypothesis. So I'm going to be lazy and list and explain them as the Wikipedia article does, along with panels and story beats that show Makima taking these "steps" in the perception of the reader:

(from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anima_and_animus#Stages_of_eroticism)

STAGE 1: EVE

The anima is completely tied up with woman as provider of nourishment, security and love.

The man at this anima level cannot function well without a woman, and is more likely to be controlled by her or, more likely, by his own imaginary construction of her.

STAGE 2: HELEN

In this phase, women are viewed as capable of worldly success and of being self-reliant, intelligent and insightful, even if not altogether virtuous.

STAGE 3: MARY

At this level, women can now seem to possess virtue by the perceiving man (even if in an esoteric and dogmatic way)

STAGE 4: SOPHIA

Complete integration has now occurred, which allows women to be seen and related to as particular individuals who possess both positive and negative qualities. The most important aspect of this final level is that, as the personification "Wisdom" suggests, the anima is now developed enough that no single object can fully and permanently contain the images to which it is related.

BUT WHAT THE HELL DO I DO WITH THIS???

Why is a female character undergoing a process that manifests her as a realized, independent woman with agency in the eyes of the reader the arc of the major antagonist?

(The plot even infantilizes her with the Nayuta thing in the resolution — essentially forcing her to undo those steps of maturation and realization).

Are the accusations true? Is CSM an incel/gooner manga after all???(jk).

But there is something here. My mind wants to connect it how women are perceived in our time. Specifically: female professionals (Japanese Salarywomen, in particular). I am wondering if Makima unintentionally comes to represent the anxiety caused by the rise of non-masculine individuals directly or indirectly challenging male-centric, heteronormative, "traditional" schemas of gender roles across professions, education, and even self-perception.

(Control Devil? More like Women Devil.)

And this is just awful. Because now I have to read Jung. I have to examine Japanese views on the rise of professional women in society. And I'll probably have to look at modern psychoanalysis, because I'm sure there are more recent ideas about gender perceptions as archetypes and collective frameworks.

But it's June. For god's sake, I need to be outside, enjoying the weather with my friends and family. I have fics to catch up on (reading and writing). I have hobbies I need to pursue...

But this lady keeps belly-flopping on my cerebrum. Making me do writeups for a manga i don't even read anymore...

FR tho if anyone has uh "leads" on where to take this just say.

If you disagree and think I'm dumb or coping go ahead and say too.

have a good one and stuff

#makima#chainsaw man#csm spoilers#carl jung#gender#psychoanalysis#collective unconscious#my makima thoughts#my favorite civil servant#character analysis#rant post

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey Marie!

How are you? Are you enjoying Tumblr more?

So I have started revolutionary girl utena (the way i known it could have changed the trajectory of my entire life if i had seen it at eight) and I am in love with the concepts, the themes, the architectures, everything.

Do you have similar books/movies to recommend? Any other media?

Hi!! 🌹🍓

I’m trying! :)

And I’m so, so happy you enjoyed Utena!!! Ever since I first came into contact with the phenomenon that is revolutionary girl Utena, I’ve been trying to find something that evokes a similar emotion. So far, I haven’t found anything that combines elements in a similar way — as you mentioned, there are so many aspects of it, themes, art, music, architecture. I feel like maybe we’ll have to accept that it is a completely unique piece of fiction. However, we can still read!

What I think might be a fun endeavour is to make a list of the references they make and compile a reading list out of that. Astronomy, psychoanalysis, myths, art history, there’s a LOT to dig into and I feel like enriching our own inner lives will prolong our enjoyment of Utena and deepen our enjoyment of the other material it’s referencing (if that makes sense). In the meantime, while I compile that list, here are some other things:

fairy tales (eastern European and German especially) for their interwoven morals and thoughts on death and agency. Reread sleeping beauty and savour every word (bones wrapped in rose vines), dig into Tsarevich Ivan, the Firebird and the Gray Wolf and think about fate and rebirth.

Demian by Herman Hesse. It seems that not many people know that the show (not the film or manga) directly quote Hesse every single episode — or both go back to the same source, I’m not sure which. Either way: Demian comes close in many aspects. Not telling you which ones <3 (I read it without knowing anything about it because I saw that quote and I think it was the best possible way to come into contact with that book, so I’ll let you enjoy it the same way)

The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony by Roberto Calasso analyses and compares Greek myths, weaves them together and summarises them in ways you might not have thought about before.

The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy for thoughts on trauma and beauty, history and sibling relationships.

Nabokov in general for various thoughts on language, isolation, beauty. Invitation to a Beheading for that doomed isolation. Ada or Ardor if you were intrigued by the highly mannerist incest (it’s more carnal in Nabokov, but still extremely gorgeous and soaked with that same old blood elitism and high profile intellectualism)

Apart from that, I feel like SKU is a child of its time. If you look at other manga from the time just before the new millennium, there are a lot of reoccurring themes. Sailor Moon, X (which I never finished, so this is just a first impression), etc all feature themes like the end of the world, other universes, secret societies and glittering architecture in dark voids. I’m always on the lookout for more manga from around that time because the strange future nostalgia is so fascinating to me.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

"We are unique emanations of the same shared Light."

Collective unconscious refers to the unconscious mind and shared mental concepts. It is generally associated with idealism and was coined by Carl Jung. According to Jung, the human collective unconscious is populated by instincts, as well as by archetypes: ancient primal symbols such as

The Great Mother

The Shadow

"Shadows were cast here. History made.”

“Am I to cast a Shadow?”

“Yes. You were bred to be a sorrow-bearer. I seek a Hive commander, but those are not so readily available. So I made you.”

"The shadows, showing the truth by their casting."

The Tower

Water

"...wellsprings and rivers..."

The Tree of Life

Jung considered the collective unconscious to underpin and surround the unconscious mind, distinguishing it from the personal unconscious of Freudian psychoanalysis. He believed that the concept of the collective unconscious helps to explain why similar themes occur in mythologies around the world.

O: [sighs] I do not fully understand what I saw, and for a Human to understand a Hive mind... How many legends of katabasis do we have, Ikora?

I: We currently have dozens of stories about descending to the realms of the dead, though research has indicated many more must have existed, lost in the layers of Human history we will never lay eyes on. Mathematically, there were likely hundreds.

I: [pauses] Inanna and Dumuzid and Geshtinanna, Orpheus and Eurydice, Izanagi and Izanami, to name a few. Gods and goddesses, mortal and immortal lovers, always seeking to descend and return with the lost.

O: And neither the lost nor those who searched for them were ever returned the same.

He argued that the collective unconscious had a profound influence on the lives of individuals, who lived out its symbols and clothed them in meaning through their experiences.

"They evidently live and function in the deeper layers of the unconscious, especially in that phylogenetic substratum which I have called the collective unconscious. This localization explains a good deal of their strangeness: they bring into our ephemeral consciousness an unknown psychic life belonging to a remote past. It is the mind of our unknown ancestors, their way of thinking and feeling, their way of experiencing life and the world, gods, and men. The existence of these archaic strata is presumably the source of man's belief in reincarnations and in memories of 'previous experiences'. Just as the human body is a museum, so to speak, of its phylogenetic history, so too is the psyche."

Ego | Shadow

Sacred Progenitor | Tyrannical Progenitor

Old Wise Man | Trickster

Animus | Anima

Meaning | Absurdity

Centrality | Diffusion

Order | Chaos

Opposition | Conjunction

Time | Eternity

Sacred | Profane

Transformation | Fixity

Light | Darkness

"And the essential thing, psychologically, is that in dreams, fantasies, and other exceptional states of mind the most far-fetched mythological motifs and symbols can appear autochthonously at any time, often, apparently, as the result of particular influences, traditions, and excitations working on the individual, but more often without any sign of them. These "primordial images" or "archetypes," as I have called them, belong to the basic stock of the unconscious psyche and cannot be explained as personal acquisitions. Together they make up that psychic stratum which has been called the collective unconscious. The existence of the collective unconscious means that individual consciousness is anything but a tabula rasa and is not immune to predetermining influences. On the contrary, it is in the highest degree influenced by inherited presuppositions, quite apart from the unavoidable influences exerted upon it by the environment. The collective unconscious comprises in itself the psychic life of our ancestors right back to the earliest beginnings. It is the matrix of all conscious psychic occurrences, and hence it exerts an influence that compromises the freedom of consciousness in the highest degree, since it is continually striving to lead all conscious processes back into the old paths."

Every weapon wielded and scrap of armor worn, every place visited, person met, symbol seen and pondered, every thought formed and lost and formed again... each one has a place in this story. Haven't you ever wondered what it all means? Where the path leads? Many have followed it before, countless numbers. And soon, it will be your turn. To walk. To see.

To understand.

A dream of a metaphor made starkly, an allegory discussed in study of ontology, in Darkness not unkind. It leaves behind a warped, barely-real data fragment to mark its passing. There is a voice that echoes across the Darkness, and it asks this question: what is the purpose of it all? And there is another voice that calls back and says: listen, I will tell you a purpose. I will tell you of a Final Shape. Look: there are a hundred gildings for this story. It comes down to one key matter. Beings in suffering crave purpose to carry them through. The tyrant consumed by ennui or the disenfranchised struggling simply to survive—it is the state of mind, the pain which cries out: give me a reason I should suffer so! Let us speak of power and choices. A man comes to a crossroads and asks of the sky, "Which road shall I take?" There is no answer from the sky, nor the wind, nor the earth beneath his feet. But another wanderer on the road, coming from behind and hearing the question, says, "I know the way. You should take the dexter road." If the man agrees, he puts himself in the wanderer's power, ceding his own choices for the implicit promise that this is the correct road, the safe road. And if he disagrees? Let us say that the wanderer draws a knife. The man may therefore be made to take the dexter road. But now if the knife goes away, the man will certainly flee. And perhaps even if the knife remains, the man may tire of being threatened and decide the risk is worth fleeing. In this way, the wanderer erodes their own power. If the wanderer says, "The wind has said that you should take the road of my choosing," will the man accept the choice made for him? And if the wanderer says, "Behold, I have seen that the meaning of suffering lies along the dexter road," will the man give away his own power for longer? Is it not easier to accept the guidance of a stranger when the path ahead is unknown?

youtube

And day dissolves into gold Night beckons and calls Night turns white with grief I can’t sleep

Whispers of the past Memories of yesteryears The things that did not last I recollect the tears

My love hold me tight There’s a haunted moon tonight Withered flowers never lie In midnight hours and numb goodbyes

Whispers of the past Memories of yesteryears The things they did not last I recollect the tears

Whispers of the past Memories of yesteryears The things they did not last I recollect the tears, the tears

#trace the vermicular path#the final shape#destiny 2#destiny#destiny the game#destiny lore#d2#destiny2#destinythegame#the veil#destiny the witness#Youtube

12 notes

·

View notes