#non-pterodactyloid pterosaur

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

☀Rhamphorhynchus | Existed from 163.5 million years ago to 145 million years ago

Rhamphorhynchus was about 50 cm (20 inches) long, with a long skull and large eyes; the nostrils were set back on the beak. The teeth slanted forward and interlocked and were probably used to eat fish. The body was short, and each thin wing membrane stretched from a long fourth finger.

Rhamphorhynchus lived during the Late Jurassic and resided in Africa and Europe. The first Rhamphorhynchus fossil was discovered in 1846.

Rhamphorhynchus muensteri is from the Late Jurassic limestone beds of Southern Germany and is one of the largest non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs. Like all pterosaurs, Rhamphorhynchus was capable of powered flight, though was potentially unusual in that young juveniles were precocial and flew from a very young age

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

On pterosaur footprints

A maker of Rhamphichnus footprints by Mark Witton. Note pronated arms.

There are three main pterosaur ichnotaxa (footprints assigned taxonomically):

Pteraichnus is by far the most common, occuring from the Jurassic to the very end of the Cretaceous, and can be considered a bit of a wastebasket taxon, though it’s well distinguished by lateral three-fingered foreprints and large hindprints.

Haenamichnus are Maastrichtian tracks assigned specifically to azhdarchids. These are very large in size and differ from Pteraichnus by having more compact footprints, with digits barely differentiated.

Rhamphichnus are tracks made by non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs. They differ from the rest in having pronated forelimbs and more square-shaped hindprints with longer toes.

These foot prints offer quite a lot about pterosaur palaeobiology. Haenamichnus validates the notion that azhdarchids had compact feet and were specialised to hunt in terrestrial environments, while Rhamphichnus shows that early pterosaurs could rotate their forelimbs like mammals can. But the ones I find most interesting are the ‘generic’ Pteraichnus. While as mentioned above they might be a bit of a wastebasket, they are typically assumed to be made by ctenochasmatoids or dsungaripteroids (Witton 2013). Since they last until the end of the Cretaceous, this could indicate the presence of these pterosaurs well past the end of their fossils.

This has precedent, as Pteraichnus attributed to dsungaripteroids have been found in Late Cretaceous deposits, tens of millions of years after the closest footprint makers disappear from the fossil reccord. Therefore, they indicate long fossil ghost lineages.

Hopefully, more studies will be conducted on pterosaur footprints.

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monday Musings: What caused the end of the Jurassic Period?

That's a tough question to answer. Scientists has a few hypotheses:

1.) Major Marine Regression

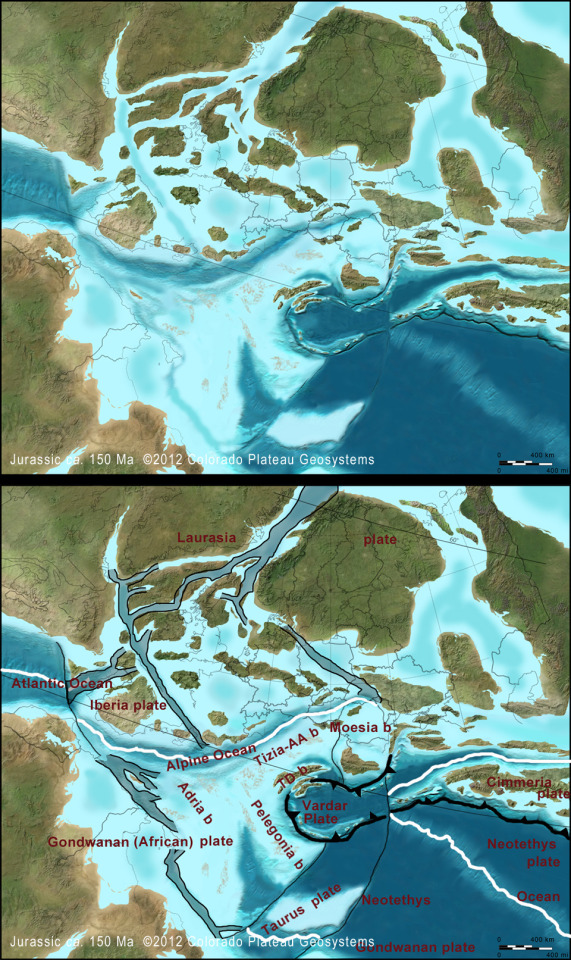

The is evidence in Europe of a major sea level drop which would have caused localized extinctions. I mean, look how low sea level dropped within 25 million years!

2.) Volcanism

The Tithonian stage of the Late Jurassic saw the creation of a large volcanic plateau in the north Pacific and numerous volcanic deposits where Gondwana was beginning to separate. None of these explain the Laurasian extinctions though.

3.) Asteroid Impact

There were three minor asteroid impacts during the Late Jurassic; one in South Africa, one in Australia, and one in Norway. None were large enough to have a global impact.

5.) Sampling Bias

We simply might just be missing part of the picture. In western North America, we are actually missing a chunk of time in our rocks between the end of the Jurassic and the beginning of the Cretaceous. We also see many Jurassic lagerstätten worldwide and a definite lack of such in the early Cretaceous. There also appear to be decreases in sauropod diversity, megalosaurids, and stegosaurids as well as complete extinction of non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs. This could be because they real were going extinct or because they moved to enviorments that don't preserve fossils. We may never know.

6.) There wasn't a mass extinction, just a faunal turnover. This something we can see in the Cedar Mountain Formation. Perhaps there was another one from Jurassic to Cretaceous, we just haven't found it yet.

As of right now, the boundary between the Jurassic and Cretaceous is formally undefined due to the presence of more endemic flora and fauna than cosmopolitan (more species specific to one area than global distribution). What is agreed upon was that the Jurassic ended in a cooling period that continued into the early Cretaceous. Maybe one day we will have more answers but for now it remains a mystery.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love Ramphorynchus! One of my favorite Non-Pterodactyloid Pterosaurs!

recent pixelart-paleoarts I did of Parasaurolophus, Carnotaurus, Pachyrhinosaurus and Rhamphorhynchus

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Caelestiventus hanseni, a pterosaur from the Late Triassic of Utah, USA. Living about 208-210 million years ago, it was very closely related to Dimorphodon -- but unlike its younger coastal-dwelling relative it instead lived in a desert environment made up of a massive sand dune sea with occasional interdunal lakes.

It’s the earliest known example of a desert pterosaur, over 60 million years older than other examples, suggesting that even fairly early in their evolutionary history these flying animals had already adapted to a much wider range of habitats than previously thought.

Although only known from a partial skull and a single wing bone, it was probably one of the largest Triassic pterosaurs with a wingspan of over 1.5m (4′11″). It had a “keel” on its lower jaw that may have supported a soft-tissue crest or a pelican-like throat pouch, and there were several different types of teeth in its mouth -- large pointed fangs at the front, “leaf-shaped” blades further back in its upper jaw, and numerous much smaller teeth along its lower jaw.

The skull roof also preserved the impression of Caelestiventus’ brain shape, showing that it had very well-developed vision but a poor sense of smell.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#caelestiventus#dimorphodontidae#non-pterodactyloid pterosaur#pterosaur#archosaur#desert#art

277 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dinocember p. 2: troodontid, dicynodont, non-pterodactyloid pterosaur, invertebrate (eryonid crustaceans).

868 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Let's meet the Pterosaurs for #Fossilfriday. They were flying reptiles that existed at the same time as the Dinosaurs, but they were in fact not dinosaurs - flying reptiles. Original caption:

"Pterosaurs were flying reptiles of the extinct clade or order Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 to 66 million years ago). Pterosaurs are the earliest vertebrates known to have evolved powered flight. Their wings were formed by a membrane of skin, muscle, and other tissues stretching from the ankles to a dramatically lengthened fourth finger.

There were two major types of pterosaurs. Basal pterosaurs (also called 'non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs' or ‘rhamphorhynchoids’) were smaller animals with fully toothed jaws and, typically, long tails. Their wide wing membranes probably included and connected the hind legs. On the ground, they would have had an awkward sprawling posture, but their joint anatomy and strong claws would have made them effective climbers, and they may have lived in trees. Basal pterosaurs were insectivores or predators on small vertebrates. Later pterosaurs (pterodactyloids) evolved many sizes, shapes, and lifestyles. Pterodactlyoids had narrower wings with free hind limbs, highly reduced tails, and long necks with large heads. On the ground, pterodactyloid walked well on all four limbs with an upright posture, standing plantigrade on the hind feet and folding the wing finger upward to walk on the three-fingered "hand." They could take off from the ground, and fossil trackways show at least some species were able to run and wade or swim. Their jaws had horny beaks, and some groups lacked teeth. Some groups developed elaborate head crests with sexual dimorphism.

Pterosaurs sported coats of hair-like filaments known as pycnofibers, which covered their bodies and parts of their wings. Pycnofibers grew in several forms, from simple filaments to branching down feathers. These are homologous to the down feathers of birds and some dinosaurs, suggesting that early feathers evolved in the common ancestor of pterosaurs and dinosaurs, possibly as insulation. In life, pterosaurs would have had smooth or fluffy coats that did not resemble bird feathers. They were warm-blooded (endothermic) active animals. The respiratory system had efficient unidirectional "flow-through" breathing using air sacs, which hollowed out their bones to an extreme extent. Pterosaurs spanned a wide range of adult sizes, from the very small anurognathids to the largest known flying creatures of all time, including Quetzalcoatlus and Hatzegopteryx, which reached wingspans of at least nine meters. The combination of endothermy, good oxygen supply, and strong muscles allowed pterosaurs to be powerful and capable flyers.

Pterosaurs are often referred to by popular media or the general public as "flying dinosaurs", but dinosaurs are defined as the descendants of the last common ancestor of the Saurischia and Ornithischia, which excludes the pterosaurs. Pterosaurs are nonetheless more closely related to birds and other dinosaurs than to crocodiles or any other living reptile, though they are not bird ancestors. Pterosaurs are also colloquially referred to as pterodactyls, particularly in fiction and by journalists. However, technically, pterodactyl only refers to members of the genus Pterodactylus, and more broadly to members of the suborder Pterodactyloidea of the pterosaurs.

Pterosaurs had a variety of lifestyles. Traditionally seen as fish-eaters, the group is now understood to have included hunters of land animals, insectivores, fruit eaters and even predators of other pterosaurs. They reproduced by means of eggs, some fossils of which have been discovered."

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everything Wrong With Ugh

Just because we’re on a different show despite mean we’re still not having Noddy in to point out of some of the Paleo mistakes. So yeah, enjoy that.

(So nice to have a Non-Bona person helping with SpongeBob, still love him just nice to have a break lol)

1.One hundred million years ago, can’t wait to see this get violated immediately.

2.So how did Patchy even end up here? The ads explained this but not the actual episode.

3. Non-avian dinosaurs living alongside early hum- er, whatever you call the different sapient beings in SpongeBob? I’m still sinning because it perpetuates that trope though.

4.Whatever that theropod is eating Patrick is from the 1920s, honestly. Upright posture, pronation of the hands, missing small claws on the feet, etc.

5. Pirate dude is implying that’s a Brontosaurus… it may have been made valid again, but at the time it was released it wasn’t and just Apatosaurus so sin for being wrong at the time of release.

6.I’m not sure living in the Ice Ages are what we’d call simpler times.

7. Prehistoric club cliché.

8. ‘Pterodactyl’. I haven’t heard that word in ages, and it gives me chills everytime I see it. Unless you’re talking about tiny Pterodactylus or the group of pterosaurs known as Pterodactyloids, ‘Pterodactyl’ was never a thing.

9.That pterosaur costume I’m sure is off, I mean for one the hands look connected the wrong way for sure, and those wings are pointed instead of rounded.

10.”Prehistoric stuff is, what do the kids say, cool” Adult man tries to be hip cliche.

11.‘Ugh.’ Well that’s sure a nice way to sell the episode with such an enthusiastic title.

12.Oh look, another bad pterosaur, this time a Pteranodon. Pointy wings and all that I can notice from this distance, but I’m sure it will be more fugly up close.

13.Wait, what time is this even meant to be? Is 100 MYA just what pirate Tom Kenny is depicting, or is it the episode too?. I guess assuming it’s 100 MYA then uh yeah there shouldn’t be goddamn trilobites.

14. I have the feeling this episode doesn’t understand evolution at all if it’s saying life is beginning now. Unless this is all weirdly figurative for some reason.

15.By the way, they missed the change to do a SpongeGar version of the theme song.

16 Gary is prehistoric so that means he has to be giant and have spikes, typical.

17.If Gary is that huge, we should have seen him in that first shot of the inside of his house.

18.”Wait a minute” Wow, those are 3 random English words for them to just know. It’s funny but still.

19. Oh yay, more clubs, because early whatever the f*ck these people are surely couldn’t have developed a variety of weapons.

20.Oh yeah, prehistoric thingos acting stupid, another cliché.

21. Wait a minute, this sponge, octopus and sea star all have mammalian hair. Weird.

22.”Patar!” Aside from him just yelling his name for no reason, this sin is the random use of “gar” on their names. (At least they were more creative with Squidward)

23.Prehistoric people using smell more often cliché.

24.They greet each other by hurting themselves because…comedy?

25.Where was he keeping that thing of water, and all without spilling any of it too?

26.Prehistoric people discover fire cliché. Except here it implies they haven’t even seen fire, they didn’t even make it. Which means even supposed smart guy Squidward doesn’t notice how freaking hot the fire is and burns himself. I guess this is what happens when you live in the sea.

27.Oh yeah, may as well sin the fire underwater thing because sins. And the raining underwater thing too.

28.SpongGar and Patar are immune to fire for like 30 seconds.

29.Great, Patar’s a cannibal.

30.Overly long gag is SpongeGar staring at the fire.

31.Discount 2001 music.

32.That stick went right through Patrick’s mouth. If this wasn’t animated this would be considered inappropriate for children.

33.What is he even chewing on if the stick is just sticking through him like that?

34.SpongeGar murders Mr. Krabs’s ancestor.

35.Patar sticks his bigger stick into the fire to cook the crab but when he eats it, it’s on the smaller stick.

36.Calling a caveman a troglodyte implies it’s in the genus Pan like the modern chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes. Homo neanderthalensis was so closely related to Homo sapiens that they interbred with our ancestors.

37.I’m not sure a human could survive a block of ice like that.

38.”I call him Cavey” How creative.

39.”Where do you keep getting all this stuff?!” I agree, where does that door over there lead? A time machine?

40.I really doubt every single thing around them is delicious or even edible.

41.Nor can random rocks create popcorn.

42.More Crab murder.

43. They’re full and their bellies are comically big. I have the feeling someone on DeviantArt is probably a fan.

44. Just summon more thunder with your clapping to make more fires instead of fighting. But lol, because they’re prehistoric they have to be idiots.

45.More clubs. Always the damn clubs.

46.Damn, they sure got skinny again real fast

47.Surely the fire would be out by now with the log rolling so many times. Then again this is underwater fire so maybe it’s different because the writers said so.

38.Squag’s house suddenly has a door now.

49. None of them were burnt when the flaming log went over them. Underwater fire is weird.

50.The weather was really sudden and weird back then.

51.Why is he getting mad at them? What did they do?

52.I don’t think you’re going to cook marshmallows over a burnt body.

53.They’re implying cannibalism except not really since SpongeBob and Patrick aren’t octopuses, because early humans were just savages who will eat anything apparently.

54.”Certain events in history are better left untold” So you just wasted 18 minutes of our time, great.

Damn straight I’m removing a sin for When Worlds Colide

54. Bill was doing a fine job as this cavemen until he just straight up became Patrick.

55. Random SB-129 clips are random.

56. Potty did something nice…and then went back to being a jerk for no reason.

57. That Tyrannosaurus, where do I even start? Pronated hands, wrong skull shape, weird bendy feet, way too scaly regardless of whether it was feathered or not, you name it.

(Wish I had a better sin to end but meh)

EPISODE SIN TALLY: 57

SENTENCE: Get Burned

Damn, new sin record. Noddy usually helps us get high tallies, and his were generally better than mine because this episode doesn’t exactly have a lot of plot. It’s not as good as Phineas’s take this concept, but despite how drawn out it is I do enjoy it for what it is.

Thanks again Noddy for the help.

Next time, Old Snails.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Pterosaurs did have a fifth toe. In non Pterodactyloids it supported the uropatagium, and in most Pterodactyloids it was small and likely didn't touch the ground. (In Azdarchids at least it might so reduced as to be invisible externally according to one of Witton's posts).

Ah, but I specified Pteranodon - which entirely lacked a fifth toe. (See Witton’s 2013 book, page 179)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Navajodactylus

Two depictions of Navajodactylus as a non-azhdarchid pterodactyloid, by Spooky and Corvarts respectively.

Navajodactylus boerei is an interesting Late Cretaceous pterosaur from the Campanian of the San Juan Basin (then part of Laramidia). Represented by a single ulna, it was tentatively attributed to Azhdarchidae when first discovered, and indeed specimens attached to the genus found in Canada were transfered to the azhdarchid Cryodrakon boreas. However, the original specimen has no features attributed to Azhdarchidae, and indeed Mark Witton is not convinced it belongs to this clade (Witton 2013).

This means that Navajodactylus is an example of a non-azhdarchid pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous, though further studies will need to be made. Personally, I think it is a ctenochasmatoid based on two criteria:

Coupled with how scarce pterosaur remains are, a ctenochasmatoid ghost lineage enduring to the Late Cretaceous is plausible, if needing more work.

Until then, this goober should be considered quite a remarkable animal

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

More on pterosaur trackways

A recent study has examined the known pterosaur trackways and has found previously unseen diversity and alignment with three major clades: Ctenochasmatoidea, Dsungaripteridae and Neoazhdarchia. This is consistent with these pterosaurs being among the most terrestrial of their kind, and neatly showcases these clades’ evolutionary history across time (though with caveats like the parcity of the fossil reccord across some eras).

A few negative notes:

This study still seems to ignore the non-pterodactyloid trackways, which I addressed previously.

They seem to ignore the Late Cretaceous dsungaripteroid trackways.

It’s a shame, but otherwise the study is sound.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Early pterosaurs were bad on land you say?" nah

A recent study concluded that early pterosaurs were arboreal and incapable of moving efficiently on the ground, with derived pterodactyloids being more efficient walkers. This is a traditional view on pterosaur evolution... which ignores a study that has concluded that early pterosaurs were efficient on the ground as well, as well as flat out ignoring a study showing non-pterodactyloid Rhamphichnus trackways (though granted, one study finds them to be non-pterosaurian).

I will say, this study does offer interesting prospects, including that most non-pteranodontian ornithocheiroids* were arboreal, which is a goldmine for paleoart. But I can't stand seeing so many studies disregarded to arrive at this paper's conclusion.

*as in, actual ornithocheiroids, and not the Kellner definition as Pteranodontia + Dsungaripteroidea + Azhdarchoidea. Feels so good to use it in the proper context again!

In the end? Maybe early pterosaurs were more arboreal than pterodactyloids on average. But they were no slops on the ground.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The most terrestrial pterosaurs

Noripterus complicidens by Ceri Thomas. This was the only known pterosaur to have been digitigrade (on the hindlimbs at least), amplyfing its ability to run.

When it comes to discussions on pterosaur ecologies, azhdarchids are usually touted as “the most terrestrially inclined pterosaurs”, thanks to now numerous studies on their ability to stride, footprints and relatively short wings. However, these claims often ignore that various other groups of pterosaurs were also adapted for terrestrial locomotion.

Terrestrial gaits of early pterosaurs by Witton et al 2015. As you can see, with very few exceptions, most early pterosaurs had long limbs and were likely able to walk and run decently.

Fact of the matter, nearly all pterosaurs were foraging on the ground or in the water (barring a few exceptions like anurognathids, eudimorphodonts, Campylognathoides and some nyctosaurids and anhanguerids, all of which adapted to hunt on the wing), and indeed pterosaurs were terrestrially competent from the start; while historically it had been assumed that non-pterodactyloids were inept on the ground like most bats, Witton et al 2015 shows this was not the case, and that early pterosaurs had always been competent terrestrial striders.

Still, both a crow and an ostrich forage on the ground, so there has to be a gradient.

Azhdarchids are assumed to be near the ostrich level on said gradient, and indeed compared to most pterosaurs they had short wings and long legs. However, various studies (Witton 2008, Habib 2010, Padian 2021, a study on Mark Witton’s patreon not made public) have consistently compared azhdarchids to large continental flyers like storks, swans and condors, so while terrestrially competent they were still highly competent flyers likely capable of enduring long migrations. Further, while their wings were proportionally shorter than most pterosaurs’ they had high bone pneumacy, having thin bone walls and being the only pterosaur group aside from pteranodontians to have pneumatic hindlimbs. So they weren’t on the verge of becoming flightless, rather they were equally at home in the ground and in the air.

There are two pterosaur groups that I would instead consider “most terrestrial”, at least by virtue of lower flight capacities: the dimorphodontids and the dsungaripterids. Both groups were rather heavy boned with thick bone walls and relied on burst flying like modern fowl (Witton 2008, Witton 2013). Both groups had longer wing fingers than azhdarchids, but in the case of dimorphodontids they lacked the long metacarpal of pterodactyloids so proportions might be very similar overall, leaving only dsungaripterids with longer wings overall. And within the latter, at least one species, Noripterus complicidens, had digitigrade hindlimbs, making it the most cursorial pterosaur known yet.

So there you have it. If azhdarchids were the storks of the Cretaceous, dsungaripterids and dimorphodontids were the fowl of their time.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

The pterosaur hindwing

Ornithocheirus by John Conway. Notice legs forming a secondary set of wings, which the author even compares to a biplane in his original description.

A common trend in pterosaur paleoart in the mid-2000’s was depicting them with two sets of wings. In these depictions the legs, usually free from the brachiopatagium, would be elevated in flight and, thanks to their own uropatagia running alongside them, form a secondary set of wings. Essentially, a membranous version of the tail feathers of birds like swallows or kites.

This trend seems to have been popularised by John Conway and quickly took hold, before disappearing roughly in the early 2010’s. Nowadays, it is rare to see this type of depiction, at least among serious artists.

The appeal of the pterosaur hindwing is pretty basic. At the time, it was increasingly common to try to reinvent pterosaurs away from more bat-like depictions of decades prior and to compare them functionally to birds, including giving them a more “dynamic” look. It was thought that pterosaurs rose their legs in flight like modern gliding lizards and the extent of the brachiopatagium at the time was less publicized (though known since Pterodactylus specimens were first described). Add in the discovery of four winged dinosaurs like Microraptor, and the idea that pterosaurs had a similar bauplan just sort of clicked, you know.

So what happened?

Lonchodectes by Ceri Thomas. This represents the modern (and ironically conservative) interpretation of pterodactyloid hindlimbs: attached to the brachiopatagium and with no wing shape.

Seeing as this trend died out around the publication of Mark Witton’s book on pterosaurs, more widespread information on pterosaur anatomy can be considered the killer of the pterosaur hindwings. We’ve already known for a while that the hindlegs of pterosaurs were connected to the brachiopatagium and that the cr/uropatagia of pterodactyloids was vestigial at best while that of their earlier cousins formed a blob-like shape not particularly resembling wings, but a few factoids have since shut down this artistic concept:

The idea that pterosaurs needed tails is not well funded. Modern birds can fly without tails and many extinct bird clades like Enantiornithes and lithornithids lacked tail fans and were still efficient flyers. Likewise, many modern bats like flying foxes are in the same boat as pterodactyloid pterosaurs, with vestigial uropatagia.

The need to functionally compare pterosaurs to birds has reached an all time low. Most notable is the notion that pterosaurs used their forelimbs to launch; this would make the seperation of the legs from the brachiopatagium less urgent.

It is not entirely clear if pterosaurs could raise their hindlimbs like gliding lizards do. A 2018 study suggests pterosaurs had such erect hindlimbs that they were just as incapable as birds of raising their hindlegs, but this study has since been criticised for ignoring soft tissues. It seems most likely pterosaurs could still raise their hindlegs, but this probably only helped reduce drag, rather than form a secondary wing set.

A more recent Rhamphorhynchus depiction by John Conway. Note the cruropatagium; non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs had a single large membrane between their hindlegs, but while this might have added additional lift it doesn’t seem to have formed anything wing-like.

The pterosaur hindwing is an interesting hypothesis, and while it doesn’t seem to have survived the test of time it was an interesting flame while it lasted.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Caviramus schesaplanensis, a pterosaur from the Late Triassic of Switzerland (~205 mya). Known from two fossil specimens -- a partial jaw and a much more complete skull and skeleton -- it was about the size of a modern raven, with a length of around 60cm (2′) and a wingspan of 1.35m (4′5″).

(The more complete fossil is also sometimes considered to be a separate genus and species, Raeticodactylus filisurensis, depending on which pterosaur specialist you ask. If it was a different animal it still would have been very closely related to Caviramus, though, and the two would likely have looked very similar to each other.)

It had some odd anatomy for an early pterosaur, with proportionally long and slender limbs and a fairly heavily-built skull. There were bony crests on both its upper and lower jaws, with the upper crest probably supporting a much larger soft-tissue structure.

Powerful jaw muscles along with a combination of fang-like teeth at the front of its jaws and and serrated slicing-chewing teeth further back suggest it was specialized for eating particularly tough foods such as hard-shelled invertebrates -- and it may even have been omnivorous, capable of eating plant matter as well.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#caviramus#raeticodactylus#non-pterodactyloid pterosaur#'rhamphorhynchoid'#pterosaur#archosaur#art#triassic

387 notes

·

View notes