#oleograph

Photo

Radha Krishna

Old Oleograph on Paper (via Alliya Art Gallery, Mumbai)

56 notes

·

View notes

Photo

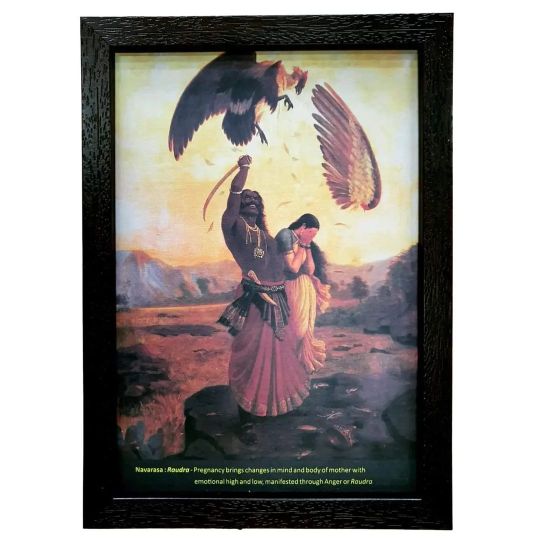

. . Raja Ravi Varma's Jatayu Vatha - Lanka king Raavan killing the divine bird Jatayu who came to intervene kidnapping of Sita Devi, individual original canvas styled Lithograph depicting the emotion, portrait framed over board sandwich framed, Exceptional detailing & colour reproduction comissioned by Sri Jayachamrajendra art gallery trust, Jaganmohan palace, Mysore, very rare subjects, framed in removable clip frame to easily take out the original Lithograph in case if needed to be reframed. . . Provenance: Artist - Raja Ravi Varma, Commissoned & Published with Certification by - Sri Jayachamrajendra art gallery trust, Jaganmohan palace, Mysore. . . Dimensions 13 inches tall 9.5 inches wide . . 🛒Now on Sale🏷 🛃Check📏 Dimensions for size ❌ No Returns-Exchange-Refunds 📮 DM to Buy🛒 🚚Free Shipping in 🇮🇳 ✈Safe Shipping 📦 Worldwide 🌎 . . #indiantiquest #war #king #antiqueart #ramayan #antiquestore #victory #rajaravivarma #srilanka #women #oleograph #kingdom #lithograph #sitadevi #rarefinds #prints #photo #jatayuvadh #artprints #portraitphotography #indiandecor #mythology #storyofindia #epic #story #antiqueprints #raavan #abduction #gods (at Indian Antique Quest) https://www.instagram.com/p/Co7eoc1g7k6/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#indiantiquest#war#king#antiqueart#ramayan#antiquestore#victory#rajaravivarma#srilanka#women#oleograph#kingdom#lithograph#sitadevi#rarefinds#prints#photo#jatayuvadh#artprints#portraitphotography#indiandecor#mythology#storyofindia#epic#story#antiqueprints#raavan#abduction#gods

0 notes

Text

Raja Ravi Varma Oleographs: A Glimpse into Classical Indian Art

Raja Ravi Varma, a celebrated 19th-century Indian artist, revolutionized the art scene by making his exquisite paintings accessible to the masses through oleographs. These vibrant, detailed prints depicted Hindu gods, goddesses, and scenes from epics, blending European techniques with Indian sensibilities. Varma's legacy lives on, not just in galleries but in homes, thanks to the widespread popularity of his oleographs.

For those keen on owning a piece of this rich cultural heritage, Beyond Square stands out as the best place to purchase Raja Ravi Varma's oleographs. Renowned for its dedication to authenticity and quality, Beyond Square offers art enthusiasts and collectors a chance to acquire these timeless pieces. Their carefully curated selection ensures that each oleograph is more than just an art purchase; it's an investment in the beauty and history of Indian art. Whether you're decorating your home or seeking to enrich your collection, Beyond Square provides an unmatched opportunity to connect with India's artistic past through the vibrant legacy of Raja Ravi Varma's oleographs.

0 notes

Text

Abella Danger , Gina Valentina In Two Big Asses Sharing a Big Cock

latina getting hit from the back for snapchat

Riley Reid fucking bed

Teen latina gets fucked

College Man Chewing Gummy Bears

ebony shemale beauty Blac Diamond showcase her round ghetto booty

Morena na siririca escondida

Khusus cewe yg mau (vcs free )

amazing sex adventures of Sombra

Video Seks Amoi Sedap Melayu

#propylaea#Oribelle#pitticite#bright-tinted#oosporangium#seventy-dollar#millenials#pretors#neat-handedness#Linkwood#Turklike#oleographic#Dilliner#wheerikins#mistutors#aggrade#Nikon#ATR#zarf#sarmentiferous

0 notes

Text

Rambha

Oleograph printed at Ravi varma Press, Karla, Lonavla

#rajaravivarma #Lithograph #Oleograph

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

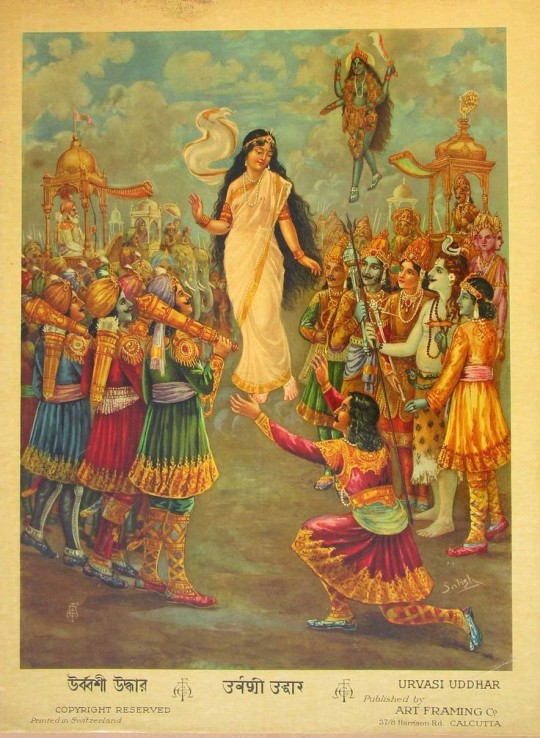

An oleograph depicting Urvashi, the most beautiful apsara, abandoning her husband, Pururavas, a king in Hindi mythology.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

vimeo

All my Eternal Love (Three Lives Three Worlds, Ten Miles of Peach Blossoms) fan art. Started making them for ma inspired from a pocket book on Kalighat Patachitra I had laying around.

Kalighat Pats are fast to create- I imagine since they used to be mass produced even before mechanical reporduction-there is not much background and a lot is dependent on form and colour. They are perfect for making fan art, that is if you want to make something in a short time- and these capture the essence of period- fantasy dramas really well since a lot of the Pats have mythological motifs.

I didn’t realise that Kalighat patachitra has the unique quality of volume added to the shapes- rare in Indian art. This may be because many patus were also sculptors and potters. Or perhaps the cultural influences imported by the British East India Company during the time in the 19th century when they were in high demand. They were replaced by oleographs by the 1930s though Patachitra is still a very popular, modern, and syncretic art form.

Was suprised to see that the Eternal Love fandom is still alive when making these- was a fun exercise.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

She also bought a record of “The Last Rose of Summer” for the Indians and found for Rom, in a dusty shop full of maps and oleographs, a book with pictures of the tapestry of The Lady and the Unicorn—a wonderful stroke of luck, for above the golden-haired virgin and her obedient beast were embroidered the words: Mon seul desir—and these were the words which Rom had whispered to her two nights ago as she lay in his arms.

—A Company of Swans by Eva Ibbotson

#writeblr#bookblr#books#book quotes#quotes#a company of swans#a company of swans by eva ibbotson#a company of swans quotes#eva ibbotson#jamietukpahwriting

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oleographs of paintings by Raja Ravi Varma painted during the 18-19th century.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

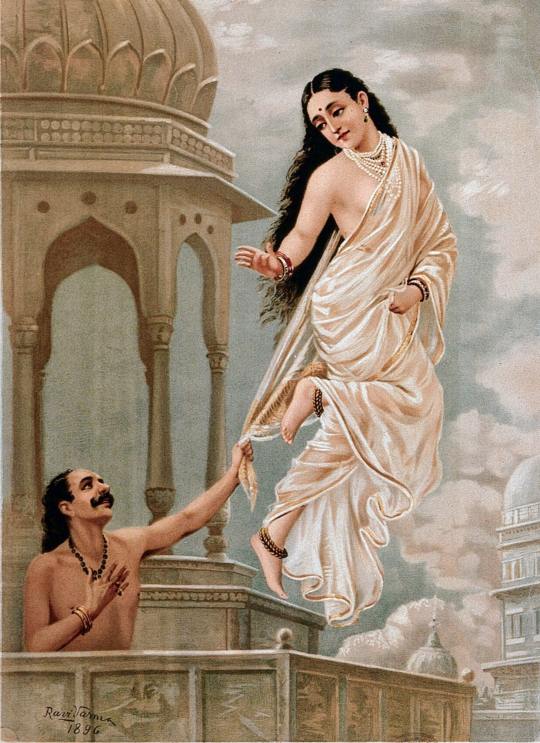

Oleograph by Ravi Varma Press, based on painting by Raja Ravi Varma.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Shree Laxmi

Early 20th century Oleograph (via StoryLTD)

137 notes

·

View notes

Photo

. . Raja Ravi Varma's Victory of Indrajith - Lanka king Raavans Son, individual original canvas styled Lithograph depicting the emotion, portrait framed over board sandwich framed, Exceptional detailing & colour reproduction comissioned by Sri Jayachamrajendra art gallery trust, Jaganmohan palace, Mysore, very rare subjects, framed in removable clip frame to easily take out the original Lithograph in case if needed to be reframed. . . Provenance: Artist - Raja Ravi Varma, Commissoned & Published with Certification by - Sri Jayachamrajendra art gallery trust, Jaganmohan palace, Mysore. . . Dimensions 13 inches tall 9.5 inches wide . . 🛒Now on Sale🏷 🛃Check📏 Dimensions for size ❌ No Returns-Exchange-Refunds 📮 DM to Buy🛒 🚚Free Shipping in 🇮🇳 ✈Safe Shipping 📦 Worldwide 🌎 . . #indiantiquest #war #king #antiqueart #ramayan #antiquestore #victory #rajaravivarma #srilanka #women #oleograph #kingdom #lithograph #marriage #rarefinds #prints #photo #heirloom #artprints #portraitphotography #indiandecor #mythology #storyofindia #epic #story #antiqueprints #raavan #indrajith #gods (at Indian Antique Quest) https://www.instagram.com/p/Co7eTbmgXLo/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#indiantiquest#war#king#antiqueart#ramayan#antiquestore#victory#rajaravivarma#srilanka#women#oleograph#kingdom#lithograph#marriage#rarefinds#prints#photo#heirloom#artprints#portraitphotography#indiandecor#mythology#storyofindia#epic#story#antiqueprints#raavan#indrajith#gods

0 notes

Text

It Can't Happen Here, Sinclair Lewis

Chapter 19-20

CHAPTER XIX

AN honest propagandist for any Cause, that is, one who honestly studies and figures out the most effective way of putting over his Message, will learn fairly early that it is not fair to ordinary folks—it just confuses them—to try to make them swallow all the true facts that would be suitable to a higher class of people. And one seemingly small but almighty important point he learns, if he does much speechifying, is that you can win over folks to your point of view much better in the evening, when they are tired out from work and not so likely to resist you, than at any other time of day.

Zero Hour, Berzelius Windrip.

THE Fort Beulah Informer had its own three-story-and basement building, on President Street between Elm and Maple, opposite the side entrance of the Hotel Wessex. On the top story was the composing room; on the second, the editorial and photographic departments and the bookkeeper; in the basement, the presses; and on the first or street floor, the circulation and advertising departments, and the front office, open to the pavement, where the public came to pay subscriptions and insert want-ads. The private room of the editor, Doremus Jessup, looked out on President Street through one not too dirty window. It was larger but little more showy than Lorinda Pike's office at the Tavern, but on the wall it did have historic treasures in the way of a water-stained surveyor's-map of Fort Beulah Township in 1891, a contemporary oleograph portrait of President McKinley, complete with eagles, flags, cannon, and the Ohio state flower, the scarlet carnation, a group photograph of the New England Editorial Association (in which Doremus was the third blur in a derby hat in the fourth row), and an entirely bogus copy of a newspaper announcing Lincoln's death. It was reasonably tidy—in the patent letter file, otherwise empty, there were only 2 1/2 pairs of winter mittens, and an 18-gauge shotgun shell.

Doremus was, by habit, extremely fond of his office. It was the only place aside from his study at home that was thoroughly his own. He would have hated to leave it or to share it with anyone— possibly excepting Buck and Lorinda—and every morning he came to it expectantly, from the ground floor, up the wide brown stairs, through the good smell of printer's ink.

He stood at the window of this room before eight, the morning when his editorial appeared, looking down at the people going to work in shops and warehouses. A few of them were in Minute Men uniforms. More and more even the part-time M.M.'s wore their uniforms when on civilian duties. There was a bustle among them. He saw them unfold copies of the Informer; he saw them look up, point up, at his window. Heads close, they irritably discussed the front page of the paper. R. C. Crowley went by, early as ever on his way to open the bank, and stopped to speak to a clerk from Ed Howland's grocery, both of them shaking their heads. Old Dr. Olmsted, Fowler's partner, and Louis Rotenstern halted on a corner. Doremus knew they were both friends of his, but they were dubious, perhaps frightened, as they looked at an Informer.

The passing of people became a gathering, the gathering a crowd, the crowd a mob, glaring up at his office, beginning to clamor. There were dozens of people there unknown to him: respectable farmers in town for shopping, unrespectables in town for a drink, laborers from the nearest work camp, and all of them eddying around M.M. uniforms. Probably many of them cared nothing about insults to the Corpo state, but had only the unprejudiced, impersonal pleasure in violence natural to most people.

Their mutter became louder, less human, more like the snap of burning rafters. Their glances joined in one. He was, frankly, scared.

He was half conscious of big Dan Wilgus, the head compositor, beside him, hand on his shoulder, but saying nothing, and of Doc Itchitt cackling, "My—my gracious—hope they don't—God, I hope they don't come up here!"

The mob acted then, swift and together, on no more of an incitement than an unknown M.M.'s shout: "Ought to burn the place, lynch the whole bunch of traitors!" They were running across the street, into the front office. He could hear a sound of smashing, and his fright was gone in protective fury. He galloped down the wide stairs, and from five steps above the front office looked on the mob, equipped with axes and brush hooks grabbed from in front of Pridewell's near-by hardware store, slashing at the counter facing the front door, breaking the glass case of souvenir postcards and stationery samples, and with obscene hands reaching across the counter to rip the blouse of the girl clerk.

Doremus cried, "Get out of this, all you bums!"

They were coming toward him, claws hideously opening and closing, but he did not await that coming. He clumped down the stairs, step by step, trembling not from fear but from insane anger. One large burgher seized his arm, began to bend it. The pain was atrocious. At that moment (Doremus almost smiled, so grotesquely was it like the nick-of-time rescue by the landing party of Marines) into the front office Commissioner Shad Ledue marched, at the head of twenty M.M.'s with unsheathed bayonets, and, lumpishly climbing up on the shattered counter, bellowed:

"That'll do from you guys! Lam out of this, the whole damn bunch of you!"

Doremus's assailant had dropped his arm. Was he actually, wondered Doremus, to be warmly indebted to Commissioner Ledue, to Shad Ledue? Such a powerful, dependable fellow—the dirty swine!

Shad roared on: "We're not going to bust up this place. Jessup sure deserves lynching, but we got orders from Hanover—the Corpos are going to take over this plant and use it. Beat it, you!"

A wild woman from the mountains—in another existence she had knitted at the guillotine—had thrust through to the counter and was howling up at Shad, "They're traitors! Hang 'em! We'll hang you, if you stop us! I want my five thousand dollars!"

Shad casually stooped down from the counter and slapped her. Doremus felt his muscles tense with the effort to get at Shad, to revenge the good lady who, after all, had as much right as Shad to slaughter him, but he relaxed, impatiently gave up all desire for mock heroism. The bayonets of the M.M.'s who were clearing out the crowd were reality, not to be attacked by hysteria.

Shad, from the counter, was blatting in a voice like a sawmill, "Snap into it, Jessup! Take him along, men."

And Doremus, with no volition whatever, was marching through President Street, up Elm Street, and toward the courthouse and county jail, surrounded by four armed Minute Men. The strangest thing about it, he reflected was that a man could go off thus, on an uncharted journey which might take years, without fussing over plans and tickets, without baggage, without even an extra clean handkerchief, without letting Emma know where he was going, without letting Lorinda—oh, Lorinda could take care of herself. But Emma would worry.

He realized that the guard beside him, with the chevrons of a squad leader, or corporal, was Aras Dilley, the slatternly farmer from up on Mount Terror whom he had often helped... or thought he had helped.

"Ah, Aras!" said he.

"Huh!" said Aras.

"Come on! Shut up and keep moving!" said the M.M. behind Doremus, and prodded him with the bayonet.

It did not, actually, hurt much, but Doremus spat with fury. So long now he had unconsciously assumed that his dignity, his body, were sacred. Ribald Death might touch him, but no more vulgar stranger.

Not till they had almost reached the courthouse could he realize that people were looking at him—at Doremus Jessup!—as a prisoner being taken to jail. He tried to be proud of being a political prisoner. He couldn't. Jail was jail.

The county lockup was at the back of the courthouse, now the center of Ledue's headquarters. Doremus had never been in that or any other jail except as a reporter, pityingly interviewing the curious, inferior sort of people who did mysteriously get themselves arrested.

To go into that shameful back door—he who had always stalked into the front entrance of the courthouse, the editor, saluted by clerk and sheriff and judge!

Shad was not in sight. Silently Doremus's four guards conducted him through a steel door, down a corridor, to a small cell reeking of chloride of lime and, still unspeaking, they left him there. The cell had a cot with a damp straw mattress and damper straw pillow, a stool, a wash basin with one tap for cold water, a pot, two hooks for clothes, a small barred window, and nothing else whatever except a jaunty sign ornamented with embossed forget-me-nots and a text from Deuteronomy, "He shall be free at home one year."

"I hope so!" said Doremus, not very cordially.

It was before nine in the morning. He remained in that cell, without speech, without food, with only tap water caught in his doubled palm and with one cigarette an hour, until after midnight, and in the unaccustomed stillness he saw how in prison men could eventually go mad.

"Don't whine, though. You here a few hours, and plenty of poor devils in solitary for years and years, put there by tyrants worse than Windrip... yes, and sometimes put there by nice, good, social-minded judges that I've played bridge with!"

But the reasonableness of the thought didn't particularly cheer him.

He could hear a distant babble from the bull pen, where the drunks and vagrants, and the petty offenders among the M.M.'s, were crowded in enviable comradeship, but the sound was only a background for the corroding stillness.

He sank into a twitching numbness. He felt that he was choking, and gasped desperately. Only now and then did he think clearly— then only of the shame of imprisonment or, even more emphatically, of how hard the wooden stool was on his ill-upholstered rump, and how much pleasanter it was, even so, than the cot, whose mattress had the quality of crushed worms.

Once he felt that he saw the way clearly:

"The tyranny of this dictatorship isn't primarily the fault of Big Business, nor of the demagogues who do their dirty work. It's the fault of Doremus Jessup! Of all the conscientious, respectable, lazy-minded Doremus Jessups who have let the demagogues wriggle in, without fierce enough protest.

"A few months ago I thought the slaughter of the Civil War, and the agitation of the violent Abolitionists who helped bring it on, were evil. But possibly they had to be violent, because easy-going citizens like me couldn't be stirred up otherwise. If our grandfathers had had the alertness and courage to see the evils of slavery and of a government conducted by gentlemen for gentlemen only, there wouldn't have been any need of agitators and war and blood.

"It's my sort, the Responsible Citizens who've felt ourselves superior because we've been well-to-do and what we thought was 'educated,' who brought on the Civil War, the French Revolution, and now the Fascist Dictatorship. It's I who murdered Rabbi de Verez. It's I who persecuted the Jews and the Negroes. I can blame no Aras Dilley, no Shad Ledue, no Buzz Windrip, but only my own timid soul and drowsy mind. Forgive, O Lord!

"Is it too late?"

Once again, as darkness was coming into his cell like the inescapable ooze of a flood, he thought furiously:

"And about Lorinda. Now that I've been kicked into reality—got to be one thing or the other: Emma (who's my bread) or Lorinda (my wine) but I can't have both.

"Oh, damn! What twaddle! Why can't a man have both bread and wine and not prefer one before the other?

"Unless, maybe, we're all coming into a day of battles when the fighting will be too hot to let a man stop for anything save bread... and maybe, even, too hot to let him stop for that!"

The waiting—the waiting in the smothering cell—the relentless waiting while the filthy window glass turned from afternoon to a bleak darkness.

What was happening out there? What had happened to Emma, to Lorinda, to the Informer office, to Dan Wilgus, to Buck and Sissy and Mary and David?

Why, it was today that Lorinda was to answer the action against her by Nipper! Today! (Surely all that must have been done with a year ago!) What had happened? Had Military Judge Effingham Swan treated her as she deserved?

But Doremus slipped again from this living agitation into the trance of waiting—waiting; and, catnapping on the hideously uncomfortable little stool, he was dazed when at some unholily late hour (it was just after midnight) he was aroused by the presence of armed M.M.'s outside his barred cell door, and by the hill-billy drawl of Squad Leader Aras Dilley:

"Well, guess y' better git up now, better git up! Jedge wants to see you—jedge says he wants to see you. Heh! Guess y' didn't ever think I'd be a squad leader, did yuh, Mist' Jessup!"

Doremus was escorted through angling corridors to the familiar side entrance of the courtroom—the entrance where once he had seen Thad Dilley, Aras's degenerate cousin, shamble in to receive sentence for clubbing his wife to death.... He could not keep from feeling that Thad and he were kin, now.

He was kept waiting—waiting!—for a quarter hour outside the closed courtroom door. He had time to consider the three guards commanded by Squad Leader Aras. He happened to know that one of them had served a sentence at Windsor for robbery with assault; and one, a surly young farmer, had been rather doubtfully acquitted on a charge of barn-burning in revenge against a neighbor.

He leaned against the slightly dirty gray plaster wall of the corridor.

"Stand straight there, you! What the hell do you think this is? And keeping us up late like this!" said the rejuvenated, the redeemed Aras, waggling his bayonet and shining with desire to use it on the bourjui.

Doremus stood straight.

He stood very straight, he stood rigid, beneath a portrait of Horace Greeley.

Till now, Doremus had liked to think of that most famous of radical editors, who had been a printer in Vermont from 1825 to 1828, as his colleague and comrade. Now he felt colleague only to the revolutionary Karl Pascals.

His legs, not too young, were trembling; his calves ached. Was he going to faint? What was happening in there, in the courtroom?

To save himself from the disgrace of collapsing, he studied Aras Dilley. Though his uniform was fairly new, Aras had managed to deal with it as his family and he had dealt with their house on Mount Terror—once a sturdy Vermont cottage with shining white clapboards, now mud-smeared and rotting. His cap was crushed in, his breeches spotted, his leggings gaping, and one tunic button hung by a thread.

"I wouldn't particularly want to be dictator over an Aras, but I most particularly do not want him and his like to be dictators over me, whether they call them Fascists or Corpos or Communists or Monarchists or Free Democratic Electors or anything else! If that makes me a reactionary kulak, all right! I don't believe I ever really liked the shiftless brethren, for all my lying hand-shaking. Do you think the Lord calls on us to love the cowbirds as much as the swallows? I don't! Oh, I know; Aras has had a hard time: mortgage and seven kids. But Cousin Henry Veeder and Dan Wilgus— yes, and Pete Vutong, the Canuck, that lives right across the road from Aras and has just exactly the same kind of land—they were all born poor, and they've lived decently enough. They can wash their ears and their door sills, at least. I'm cursed if I'm going to give up the American-Wesleyan doctrine of Free Will and of Will to Accomplishment entirely, even if it does get me read out of the Liberal Communion!"

Aras had peeped into the courtroom, and he stood giggling.

Then Lorinda came out—after midnight!

Her partner, the wart Nipper, was following her, looking sheepishly triumphant.

"Linda! Linda!" called Doremus, his hands out, ignoring the snickers of the curious guards, trying to move toward her. Aras pushed him back and at Lorinda sneered, "Go on—move on, there!" and she moved. She seemed twisted and rusty as Doremus would have thought her bright steeliness could never have been.

Aras cackled, "Haa, haa, haa! Your friend, Sister Pike—"

"My wife's friend!"

"All right, boss. Have it your way! Your wife's friend, Sister Pike, got hers for trying to be fresh with Judge Swan! She's been kicked out of her partnership with Mr. Nipper—he's going to manage that Tavern of theirn, and Sister Pike goes back to pot-walloping in the kitchen, like she'd ought to!—like maybe some of your womenfolks, that think they're so almighty stylish and independent, will be having to, pretty soon!"

Again Doremus had sense enough to regard the bayonets; and a mighty voice from inside the courtroom trumpeted: "Next case! D. Jessup!"

On the judges' bench were Shad Ledue in uniform as an M.M. battalion leader, ex-superintendent Emil Staubmeyer presenting the rôle of ensign, and a third man, tall, rather handsome, rather too face-massaged, with the letters "M.J." on the collar of his uniform as commander, or pseudo-colonel. He was perhaps fifteen years younger than Doremus.

This, Doremus knew, must be Military Judge Effingham Swan, sometime of Boston.

The Minute Men marched him in front of the bench and retired, with only two of them, a milky-faced farm boy and a former gas-station attendant, remaining on guard inside the double doors of the side entrance... the entrance for criminals.

Commander Swan loafed to his feet and, as though he were greeting his oldest friend, cooed at Doremus, "My dear fellow, so sorry to have to trouble you. Just a routine query, you know. Do sit down. Gentlemen, in the case of Mr. Doremus, surely we need not go through the farce of formal inquiry. Let's all sit about that damn big silly table down there—place where they always stick the innocent defendants and the guilty attorneys, y' know—get down from this high altar—little too mystical for the taste of a vulgar bucket-shop gambler like myself. After you, Professor; after you, my dear Captain." And, to the guards, "Just wait outside in the hall, will you? Close the doors."

Staubmeyer and Shad looking, despite Effingham Swan's frivolity, as portentous as their uniforms could make them, clumped down to the table. Swan followed them airily, and to Doremus, still standing, he gave his tortoise-shell cigarette case, caroling, "Do have a smoke, Mr. Doremus. Must we all be so painfully formal?"

Doremus reluctantly took a cigarette, reluctantly sat down as Swan waved him to a chair—with something not quite so airy and affable in the sharpness of the gesture.

"My name is Jessup, Commander. Doremus is my first name."

"Ah, I see. It could be. Quite so. Very New England. Doremus." Swan was leaning back in his wooden armchair, powerful trim hands behind his neck. "I'll tell you, my dear fellow. One's memory is so wretched, you know. I'll just call you 'Doremus,' sans Mister. Then, d' you see, it might apply to either the first (or Christian, as I believe one's wretched people in Back Bay insist on calling it)—either the Christian or the surname. Then we shall feel all friendly and secure. Now, Doremus, my dear fellow, I begged my friends in the M.M.—I do trust they were not too importunate, as these parochial units sometimes do seem to be—but I ordered them to invite you here, really, just to get your advice as a journalist. Does it seem to you that most of the peasants here are coming to their senses and ready to accept the Corpo fait accompli?"

Doremus grumbled, "But I understood I was dragged here—and if you want to know, your squad was all of what you call 'importunate'!— because of an editorial I wrote about President Windrip."

"Oh, was that you, Doremus? You see?—I was right—one does have such a wretched memory! I do seem now to remember some minor incident of the sort—you know—mentioned in the agenda. Do have another cigarette, my dear fellow."

"Swan! I don't care much for this cat-and-mouse game—at least, not while I'm the mouse. What are your charges against me?"

"Charges? Oh, my only aunt! Just trifling things—criminal libel and conveying secret information to alien forces and high treason and homicidal incitement to violence—you know, the usual boresome line. And all so easily got rid of, my Doremus, if you'd just be persuaded—you see how quite pitifully eager I am to be friendly with you, and to have the inestimable aid of your experience here— if you'd just decide that it might be the part of discretion—so suitable, y' know, to your venerable years—"

"Damn it, I'm not venerable, nor anything like it. Only sixty. Sixty-one, I should say."

"Matter of ratio, my dear fellow. I'm forty-seven m'self, and I have no doubt the young pups already call me venerable! But as I was saying, Doremus—"

(Why was it he winced with fury every time Swan called him that?)

"—with your position as one of the Council of Elders, and with your responsibilities to your family—it would be too sick-making if anything happened to them, y' know!—you just can't afford to be too brash! And all we desire is for you to play along with us in your paper—I would adore the chance of explaining some of the Corpos' and the Chief's still unrevealed plans to you. You'd see such a new light!"

Shad grunted, "Him? Jessup couldn't see a new light if it was on the end of his nose!"

"A moment, my dear Captain.... And also, Doremus, of course we shall urge you to help us by giving us a complete list of every person in this vicinity that you know of who is secretly opposed to the Administration."

"Spying? Me?"

"Quite!"

"If I'm accused of—I insist on having my lawyer, Mungo Kitterick, and on being tried, not all this bear-baiting—"

"Quaint name. Mungo Kitterick! Oh, my only aunt! Why does it give me so absurd a picture of an explorer with a Greek grammar in his hand? You don't quite understand, my Doremus. Habeas corpus— due processes of law—too, too bad!—all those ancient sanctities, dating, no doubt, from Magna Charta, been suspended—oh, but just temporarily, y' know—state of crisis—unfortunate necessity martial law—"

"Damn it, Swan—"

"Commander, my dear fellow—ridiculous matter of military discipline, y' know—such rot!"

"You know mighty well and good it isn't temporary! It's permanent— that is, as long as the Corpos last."

"It could be!"

"Swan—Commander—you get that 'it could be' and 'my aunt' from the Reggie Fortune stories, don't you?"

"Now there is a fellow detective-story fanatic! But how too bogus!"

"And that's Evelyn Waugh! You're quite a literary man for so famous a yachtsman and horseman, Commander."

"Horsemun, yachtsmun, lit-er-ary man! Am I, Doremus, even in my sanctum sanctorum, having, as the lesser breeds would say, the pants kidded off me? Oh, my Doremus, that couldn't be! And just when one is so feeble, after having been so, shall I say excoriated, by your so amiable friend, Mrs. Lorinda Pike? No, no! How too unbefitting the majesty of the law!"

Shad interrupted again, "Yeh, we had a swell time with your girl-friend, Jessup. But I already had the dope about you and her before."

Doremus sprang up, his chair crashing backward on the floor. He was reaching for Shad's throat across the table. Effingham Swan was on him, pushing him back into another chair. Doremus hiccuped with fury. Shad had not even troubled to rise, and he was going on contemptuously:

"Yuh, you two'll have quite some trouble if you try to pull any spy stuff on the Corpos. My, my, Doremus, ain't we had fun, Lindy and you, playing footie-footie these last couple years! Didn't nobody know about it, did they! But what you didn't know was Lindy—and don't it beat hell a long-nosed, skinny old maid like her can have so much pep!—and she's been cheating on you right along, sleeping with every doggone man boarder she's had at the Tavern, and of course with her little squirt of a partner, Nipper!"

Swan's great hand—hand of an ape with a manicure—held Doremus in his chair. Shad snickered. Emil Staubmeyer, who had been sitting with fingertips together, laughed amiably. Swan patted Doremus's back.

He was less sunken by the insult to Lorinda than by the feeling of helpless loneliness. It was so late; the night so quiet. He would have been glad if even the M.M. guards had come in from the hall. Their rustic innocence, however barnyardishly brutal, would have been comforting after the easy viciousness of the three judges.

Swan was placidly resuming: "But I suppose we really must get down to business—however agreeable, my dear clever literary detective, it would be to discuss Agatha Christie and Dorothy Sayers and Norman Klein. Perhaps we can some day, when the Chief puts us both in the same prison! There's really, my dear Doremus, no need of your troubling your legal gentleman, Mr. Monkey Kitteridge. I am quite authorized to conduct this trial—for quaintly enough, Doremus, it is a trial, despite the delightful St. Botolph's atmosphere! And as to testimony, I already have all I need, both in the good Miss Lorinda's inadvertent admissions, in the actual text of your editorial criticizing the Chief, and in the quite thorough reports of Captain Ledue and Dr. Staubmeyer. One really ought to take you out and shoot you—and one is quite empowered to do so, oh quite!—but one has one's faults—one is really too merciful. And perhaps we can find a better use for you than as fertilizer—you are, you know, rather too much on the skinny side to make adequate fertilizer.

"You are to be released on parole, to assist and coach Dr. Staubmeyer who, by orders from Commissioner Reek, at Hanover, has just been made editor of the Informer, but who doubtless lacks certain points of technical training. You will help him—oh, gladly, I am sure!—until he learns. Then we'll see what we'll do with you!... You will write editorials, with all your accustomed brilliance—oh, I assure you, people constantly stop on Boston Common to discuss your masterpieces; have done for years! But you'll write only as Dr. Staubmeyer tells you. Understand? Oh. Today—since 'tis already past the witching hour—you will write an abject apology for your diatribe—oh yes, very much on the abject side! You know—you veteran journalists do these things so neatly—just admit you were a cockeyed liar and that sort of thing— bright and bantering—you know! And next Monday you will, like most of the other ditchwater-dull hick papers, begin the serial publication of the Chief's Zero Hour. You'll enjoy that!"

Clatter and shouts at the door. Protests from the unseen guards. Dr. Fowler Greenhill pounding in, stopping with arms akimbo, shouting as he strode down to the table, "What do you three comic judges think you're doing?"

"And who may our impetuous friend be? He annoys me, rather," Swan asked of Shad.

"Doc Fowler—Jessup's son-in-law. And a bad actor! Why, couple days ago I offered him charge of medical inspection for all the M.M.'s in the county, and he said—this red-headed smart aleck here!—he said you and me and Commissioner Reek and Doc Staubmeyer and all of us were a bunch of hoboes that 'd be digging ditches in a labor camp if we hadn't stole some officers' uniforms!"

"Ah, did he indeed?" purred Swan.

Fowler protested: "He's a liar. I never mentioned you. I don't even know who you are."

"My name, good sir, is Commander Effingham Swan, M.J.!"

"Well, M. J., that still doesn't enlighten me. Never heard of you!"

Shad interrupted, "How the hell did you get past the guards, Fowley?" (He who had never dared call that long-reaching, swift-moving redhead anything more familiar than "Doc.")

"Oh, all your Minnie Mouses know me. I've treated most of your brightest gunmen for unmentionable diseases. I just told them at the door that I was wanted in here professionally."

Swan was at his silkiest: "Oh, and how we did want you, my dear fellow—though we didn't know it until this moment. So you are one of these brave rustic Aesculapiuses?"

"I am! And if you were in the war—which I should doubt, from your pansy way of talking—you may be interested to know that I am also a member of the American Legion—quit Harvard and joined up in 1918 and went back afterwards to finish. And I want to warn you three half-baked Hitlers—"

"Ah! But my dear friend! A mil-i-tary man! How too too! Then we shall have to treat you as a responsible person—responsible for your idiocies—not just as the uncouth clodhopper that you appear!"

Fowler was leaning both fists on the table. "Now I've had enough! I'm going to push in your booful face—"

Shad had his fists up, was rounding the table, but Swan snapped, "No! Let him finish! He may enjoy digging his own grave. You know—people do have such quaint variant notions about sports. Some laddies actually like to go fishing—all those slimy scales and the shocking odor! By the way, Doctor, before it's too late, I would like to leave with you the thought for the day that I was also in the war to end wars—a major. But go on. I do so want to listen to you yet a little."

"Cut the cackle, will you, M. J.? I've just come here to tell you that I've had enough—everybody's had enough—of your kidnaping Mr. Jessup—the most honest and useful man in the whole Beulah Valley! Typical low-down sneaking kidnapers! If you think your phony Rhodes-Scholar accent keeps you from being just another cowardly, murdering Public Enemy, in your toy-soldier uniform—"

Swan held up his hand in his most genteel Back Bay manner. "A moment, Doctor, if you will be so good?" And to Shad: "I should think we'd heard enough from the Comrade, wouldn't you, Commissioner? Just take the bastard out and shoot him."

"O.K.! Swell!" Shad chuckled; and, to the guards at the half-open door, "Get the corporal of the guard and a squad—six men—loaded rifles—make it snappy, see?"

The guard were not far down the corridor, and their rifles were already loaded. It was in less than a minute that Aras Dilley was saluting from the door, and Shad was shouting, "Come here! Grab this dirty crook!" He pointed at Fowler. "Take him along outside."

They did, for all of Fowler's struggling. Aras Dilley jabbed Fowler's right wrist with a bayonet. It spilled blood down on his hand, so scrubbed for surgery, and like blood his red hair tumbled over his forehead.

Shad marched out with them, pulling his automatic pistol from its holster and looking at it happily.

Doremus was held, his mouth was clapped shut, by two guards as he tried to reach Fowler. Emil Staubmeyer seemed a little scared, but Effingham Swan, suave and amused, leaned his elbows on the table and tapped his teeth with a pencil.

From the courtyard, the sound of a rifle volley, a terrifying wail, one single emphatic shot, and nothing after.

CHAPTER XX

THE real trouble with the Jews is that they are cruel. Anybody with a knowledge of history knows how they tortured poor debtors in secret catacombs, all through the Middle Ages. Whereas the Nordic is distinguished by his gentleness and his kind-heartedness to friends, children, dogs, and people of inferior races.

Zero Hour, Berzelius Windrip.

THE review in Dewey Haik's provincial court of Judge Swan's sentence on Greenhill was influenced by County Commissioner Ledue's testimony that after the execution he found in Greenhill's house a cache of the most seditious documents: copies of Trowbridge's Lance for Democracy, books by Marx and Trotzky, Communistic pamphlets urging citizens to assassinate the Chief.

Mary, Mrs. Greenhill, insisted that her husband had never read such things; that, if anything, he had been too indifferent to politics. Naturally, her word could not be taken against that of Commissioner Ledue, Assistant Commissioner Staubmeyer (known everywhere as a scholar and man of probity), and Military Judge Effingham Swan. It was necessary to punish Mrs. Greenhill—or, rather, to give a strong warning to other Mrs. Greenhills—by seizing all the property and money Greenhill had left her.

Anyway, Mary did not fight very vigorously. Perhaps she realized her guilt. In two days she turned from the crispest, smartest, most swift-spoken woman in Fort Beulah into a silent hag, dragging about in shabby and unkempt black. Her son and she went to live with her father, Doremus Jessup.

Some said that Jessup should have fought for her and her property. But he was not legally permitted to do so. He was on parole, subject, at the will of the properly constituted authorities, to a penitentiary sentence.

So Mary returned to the house and the overfurnished bedroom she had left as a bride. She could not, she said, endure its memories. She took the attic room that had never been quite "finished off." She sat up there all day, all evening, and her parents never heard a sound. But within a week her David was playing about the yard most joyfully... playing that he was an M.M. officer.

The whole house seemed dead, and all that were in it seemed frightened, nervous, forever waiting for something unknown—all save David and, perhaps, Mrs. Candy, bustling in her kitchen.

Meals had been notoriously cheerful at the Jessups'; Doremus chattered to an audience of Mrs. Candy and Sissy, flustering Emma with the most outrageous assertions—that he was planning to go to Greenland; that President Windrip had taken to riding down Pennsylvania Avenue on an elephant; and Mrs. Candy was as unscrupulous as all good cooks in trying to render them speechlessly drowsy after dinner and to encourage the stealthy expansion of Doremus's already rotund little belly, with her mince pie, her apple pie with enough shortening to make the eyes pop out in sweet anguish, the fat corn fritters and candied potatoes with the broiled chicken, the clam chowder made with cream.

Now, there was little talk among the adults at table and, though Mary was not showily "brave," but colorless as a glass of water, they were nervously watching her. Everything they spoke of seemed to point toward the murder and the Corpos; if you said, "It's quite a warm fall," you felt that the table was thinking, "So the M.M.'s can go on marching for a long time yet before snow flies," and then you choked and asked sharply for the gravy. Always Mary was there, a stone statue chilling the warm and commonplace people packed in beside her.

So it came about that David dominated the table talk, for the first delightful time in his nine years of experiment with life, and David liked that very much indeed, and his grandfather liked it not nearly so well.

He chattered, like an entire palm-ful of monkeys, about Foolish, about his new playmates (children of Medary Cole, the miller), about the apparent fact that crocodiles are rarely found in the Beulah River, and the more moving fact that the Rotenstern young had driven with their father clear to Albany.

Now Doremus was fond of children; approved of them; felt with an earnestness uncommon to parents and grandparents that they were human beings and as likely as the next one to become editors. But he hadn't enough sap of the Christmas holly in his veins to enjoy listening without cessation to the bright prattle of children. Few males have, outside of Louisa May Alcott. He thought (though he wasn't very dogmatic about it) that the talk of a Washington correspondent about politics was likely to be more interesting than Davy's remarks on cornflakes and garter snakes, so he went on loving the boy and wishing he would shut up. And escaped as soon as possible from Mary's gloom and Emma's suffocating thoughtfulness, wherein you felt, every time Emma begged, "Oh, you must take just a little more of the nice chestnut dressing, Mary dearie," that you really ought to burst into tears.

Doremus suspected that Emma was, essentially, more appalled by his having gone to jail than by the murder of her son-in-law. Jessups simply didn't go to jail. People who went to jail were bad, just as barn-burners and men accused of that fascinatingly obscure amusement, a "statutory offense," were bad; and as for bad people, you might try to be forgiving and tender, but you didn't sit down to meals with them. It was all so irregular, and most upsetting to the household routine!

So Emma loved him and worried about him till he wanted to go fishing and actually did go so far as to get out his flies.

But Lorinda had said to him, with eyes brilliant and unworried, "And I thought you were just a cud-chewing Liberal that didn't mind being milked! I am so proud of you! You've encouraged me to fight against—Listen, the minute I heard about your imprisonment I chased Nipper out of my kitchen with a bread knife!... Well, anyway, I thought about doing it!"

The office was deader than his home. The worst of it was that it wasn't so very bad—that, he saw, he could slip into serving the Corpo state with, eventually, no more sense of shame than was felt by old colleagues of his who in pre-Corpo days had written advertisements for fraudulent mouth washes or tasteless cigarettes, or written for supposedly reputable magazines mechanical stories about young love. In a waking nightmare after his imprisonment, Doremus had pictured Staubmeyer and Ledue in the Informer office standing over him with whips, demanding that he turn out sickening praise for the Corpos, yelling at him until he rose and killed and was killed. Actually, Shad stayed away from the office, and Doremus's master, Staubmeyer, was ever so friendly and modest and rather nauseatingly full of praise for his craftsmanship. Staubmeyer seemed satisfied when, instead of the "apology" demanded by Swan, Doremus stated that "Henceforth this paper will cease all criticisms of the present government."

Doremus received from District Commissioner Reek a jolly telegram thanking him for "gallantly deciding turn your great talent service people and correcting errors doubtless made by us in effort set up new more realistic state." Ur! said Doremus and did not chuck the message at the clothes-basket waste-basket, but carefully walked over and rammed it down amid the trash.

He was able, by remaining with the Informer in her prostitute days, to keep Staubmeyer from discharging Dan Wilgus, who was sniffy to the new boss and unnaturally respectful now to Doremus. And he invented what he called the "Yow-yow editorial." This was a dirty device of stating as strongly as he could an indictment of Corpoism, then answering it as feebly as he could, as with a whining "Yow-yow-yow—that's what you say!" Neither Staubmeyer nor Shad caught him at it, but Doremus hoped fearfully that the shrewd Effingham Swan would never see the Yow-yows.

So week on week he got along not too badly—and there was not one minute when he did not hate this filthy slavery, when he did not have to force himself to stay there, when he did not snarl at himself, "Then why do you stay?"

His answers to that challenge came glibly and conventionally enough: "He was too old to start in life again. And he had a wife and family to support"—Emma, Sissy, and now Mary and David.

All these years he had heard responsible men who weren't being quite honest—radio announcers who soft-soaped speakers who were fools and wares that were trash, and who canaryishly chirped "Thank you, Major Blister" when they would rather have kicked Major Blister, preachers who did not believe the decayed doctrines they dealt out, doctors who did not dare tell lady invalids that they were sex-hungry exhibitionists, merchants who peddled brass for gold—heard all of them complacently excuse themselves by explaining that they were too old to change and that they had "a wife and family to support."

Why not let the wife and family die of starvation or get out and hustle for themselves, if by no other means the world could have the chance of being freed from the most boresome, most dull, and foulest disease of having always to be a little dishonest?

So he raged—and went on grinding out a paper dull and a little dishonest—but not forever. Otherwise the history of Doremus Jessup would be too drearily common to be worth recording.

Again and again, figuring it out on rough sheets of copy paper (adorned also with concentric circles, squares, whorls, and the most improbable fish), he estimated that even without selling the Informer or his house, as under Corpo espionage he certainly could not if he fled to Canada, he could cash in about $20,000. Say enough to give him an income of a thousand a year—twenty dollars a week, provided he could smuggle the money out of the country, which the Corpos were daily making more difficult.

Well, Emma and Sissy and Mary and he could live on that, in a four-room cottage, and perhaps Sissy and Mary could find work.

But as for himself—

It was all very well to talk about men like Thomas Mann and Lion Feuchtwanger and Romain Rolland, who in exile remained writers whose every word was in demand, about Professors Einstein or Salvemini, or, under Corpoism, about the recently exiled or self-exiled Americans, Walt Trowbridge, Mike Gold, William Allen White, John Dos Passos, H. L. Mencken, Rexford Tugwell, Oswald Villard. Nowhere in the world, except possibly in Greenland or Germany, would such stars be unable to find work and soothing respect. But what was an ordinary newspaper hack, especially if he was over forty-five, to do in a strange land—and more especially if he had a wife named Emma (or Carolina or Nancy or Griselda or anything else) who didn't at all fancy going and living in a sod hut on behalf of honesty and freedom?

So debated Doremus, like some hundreds of thousands of other craftsmen, teachers, lawyers, what-not, in some dozens of countries under a dictatorship, who were aware enough to resent the tyranny, conscientious enough not to take its bribes cynically, yet not so abnormally courageous as to go willingly to exile or dungeon or chopping-block—particularly when they "had wives and families to support."

Doremus hinted once to Emil Staubmeyer that Emil was "getting onto the ropes so well" that he thought of getting out, of quitting newspaper work for good.

The hitherto friendly Mr. Staubmeyer said sharply, "What'd you do? Sneak off to Canada and join the propagandists against the Chief? Nothing doing! You'll stay right here and help me—help us!" And that afternoon Commissioner Shad Ledue shouldered in and grumbled, "Dr. Staubmeyer tells me you're doing pretty fairly good work, Jessup, but I want to warn you to keep it up. Remember that Judge Swan only let you out on parole... to me! You can do fine if you just set your mind to it!"

"If you just set your mind to it!" The one time when the boy Doremus had hated his father had been when he used that condescending phrase.

He saw that, for all the apparent prosaic calm of day after day on the paper, he was equally in danger of slipping into acceptance of his serfdom and of whips and bars if he didn't slip. And he continued to be just as sick each time he wrote: "The crowd of fifty thousand people who greeted President Windrip in the university stadium at Iowa City was an impressive sign of the constantly growing interest of all Americans in political affairs," and Staubmeyer changed it to: "The vast and enthusiastic crowd of seventy thousand loyal admirers who wildly applauded and listened to the stirring address of the Chief in the handsome university stadium in beautiful Iowa City, Iowa, is an impressive yet quite typical sign of the growing devotion of all true Americans to political study under the inspiration of the Corpo government."

Perhaps his worst irritations were that Staubmeyer had pushed a desk and his sleek, sweaty person into Doremus's private office, once sacred to his solitary grouches, and that Doc Itchitt, hitherto his worshiping disciple, seemed always to be secretly laughing at him.

Under a tyranny, most friends are a liability. One quarter of them turn "reasonable" and become your enemies, one quarter are afraid to stop and speak and one quarter are killed and you die with them. But the blessed final quarter keep you alive.

When he was with Lorinda, gone was all the pleasant toying and sympathetic talk with which they had relieved boredom. She was fierce now, and vibrant. She drew him close enough to her, but instantly she would be thinking of him only as a comrade in plots to kill off the Corpos. (And it was pretty much a real killing-off that she meant; there wasn't left to view any great amount of her plausible pacifism.)

She was busy with good and perilous works. Partner Nipper had not been able to keep her in the Tavern kitchen; she had so systematized the work that she had many days and evenings free, and she had started a cooking-class for farm girls and young farm wives who, caught between the provincial and the industrial generations, had learned neither good rural cooking with a wood fire, nor yet how to deal with canned goods and electric grills—and who most certainly had not learned how to combine so as to compel the tight- fisted little locally owned power-and-light companies to furnish electricity at tolerable rates.

"Heavensake, keep this quiet, but I'm getting acquainted with these country gals—getting ready for the day when we begin to organize against the Corpos. I depend on them, not the well-to-do women that used to want suffrage but that can't endure the thought of revolution," Lorinda whispered to him. "We've got to do something."

"All right, Lorinda B. Anthony," he sighed.

And Karl Pascal stuck.

At Pollikop's garage, when he first saw Doremus after the jailing, he said, "God, I was sorry to hear about their pinching you, Mr. Jessup! But say, aren't you ready to join us Communists now?" (He looked about anxiously as he said it.)

"I thought there weren't any more Bolos."

"Oh, we're supposed to be wiped out. But I guess you'll notice a few mysterious strikes starting now and then, even though there can't be any more strikes! Why aren't you joining us? There's where you belong, c-comrade!"

"Look here, Karl: you've always said the difference between the Socialists and the Communists was that you believed in complete ownership of all means of production, not just utilities; and that you admitted the violent class war and the Socialists didn't. That's poppycock! The real difference is that you Communists serve Russia. It's your Holy Land. Well—Russia has all my prayers, right after the prayers for my family and for the Chief, but what I'm interested in civilizing and protecting against its enemies isn't Russia but America. Is that so banal to say? Well, it wouldn't be banal for a Russian comrade to observe that he was for Russia! And America needs our propaganda more every day. Another thing: I'm a middle-class intellectual. I'd never call myself any such a damn silly thing, but since you Reds coined it, I'll have to accept it. That's my class, and that's what I'm interested in. The proletarians are probably noble fellows, but I certainly do not think that the interests of the middle-class intellectuals and the proletarians are the same. They want bread. We want—well, all right, say it, we want cake! And when you get a proletarian ambitious enough to want cake, too—why, in America, he becomes a middle-class intellectual just as fast as he can—if he can!"

"Look here, when you think of 3 per cent of the people owning 90 per cent of the wealth—"

"I don't think of it! It does not follow that because a good many of the intellectuals belong to the 97 per cent of the broke—that plenty of actors and teachers and nurses and musicians don't get any better paid than stage hands or electricians, therefore their interests are the same. It isn't what you earn but how you spend it that fixes your class—whether you prefer bigger funeral services or more books. I'm tired of apologizing for not having a dirty neck!"

"Honestly, Mr. Jessup, that's damn nonsense, and you know it!"

"Is it? Well, it's my American covered-wagon damn nonsense, and not the propaganda-aeroplane damn nonsense of Marx and Moscow!"

"Oh, you'll join us yet."

"Listen, Comrade Karl, Windrip and Hitler will join Stalin long before the descendants of Dan'l Webster. You see, we don't like murder as a way of argument—that's what really marks the Liberal!"

About his future Father Perefixe was brief: "I'm going back to Canada where I belong—away to the freedom of the King. Hate to give up, Doremus, but I'm no Thomas à Becket, but just a plain, scared, fat little clark!"

The surprise among old acquaintances was Medary Cole, the miller.

A little younger than Francis Tasbrough and R. C. Crowley, less intensely aristocratic than those noblemen, since only one generation separated him from a chin-whiskered Yankee farmer and not two, as with them, he had been their satellite at the Country Club and, as to solid virtue, been president of the Rotary Club. He had always considered Doremus a man who, without such excuse as being a Jew or a Hunky or poor, was yet flippant about the sanctities of Main Street and Wall Street. They were neighbors, as Cole's "Cape Cod cottage" was just below Pleasant Hill, but they had not by habit been droppers-in.

Now, when Cole came bringing David home, or calling for his daughter Angela, David's new mate, toward supper time of a chilly fall evening, he stopped gratefully for a hot rum punch, and asked Doremus whether he really thought inflation was "such a good thing."

He burst out, one evening, "Jessup, there isn't another person in this town I'd dare say this to, not even my wife, but I'm getting awful sick of having these Minnie Mouses dictate where I have to buy my gunnysacks and what I can pay my men. I won't pretend I ever cared much for labor unions. But in those days, at least the union members did get some of the swag. Now it goes to support the M.M.'s. We pay them and pay them big to bully us. It don't look so reasonable as it did in 1936. But, golly, don't tell anybody I said that!"

And Cole went off shaking his head, bewildered—he who had ecstatically voted for Mr. Windrip.

On a day in late October, suddenly striking in every city and village and back-hill hide-out, the Corpos ended all crime in America forever, so titanic a feat that it was mentioned in the London Times. Seventy thousand selected Minute Men, working in combination with town and state police officers, all under the chiefs of the government secret service, arrested every known or faintly suspected criminal in the country. They were tried under court-martial procedure; one in ten was shot immediately, four in ten were given prison sentences, three in ten released as innocent... and two in ten taken into the M.M.'s as inspectors.

There were protests that at least six in ten had been innocent, but this was adequately answered by Windrip's courageous statement: "The way to stop crime is to stop it!"

The next day, Medary Cole crowed at Doremus, "Sometimes I've felt like criticizing certain features of Corpo policy, but did you see what the Chief did to the gangsters and racketeers? Wonderful! I've told you right along what this country's needed is a firm hand like Windrip's. No shilly-shallying about that fellow! He saw that the way to stop crime was to just go out and stop it!"

Then was revealed the New American Education, which, as Sarason so justly said, was to be ever so much newer than the New Educations of Germany, Italy, Poland, or even Turkey.

The authorities abruptly closed some scores of the smaller, more independent colleges such as Williams, Bowdoin, Oberlin, Georgetown, Antioch, Carleton, Lewis Institute, Commonwealth, Princeton, Swarthmore, Kenyon, all vastly different one from another but alike in not yet having entirely become machines. Few of the state universities were closed; they were merely to be absorbed by central Corpo universities, one in each of the eight provinces. But the government began with only two. In the Metropolitan District, Windrip University took over the Rockefeller Center and Empire State buildings, with most of Central Park for playground (excluding the general public from it entirely, for the rest was an M.M. drill ground). The second was Macgoblin University, in Chicago and vicinity, using the buildings of Chicago and Northwestern universities, and Jackson Park. President Hutchins of Chicago was rather unpleasant about the whole thing and declined to stay on as an assistant professor, so the authorities had politely to exile him.

Tattle-mongers suggested that the naming of the Chicago plant after Macgoblin instead of Sarason suggested a beginning coolness between Sarason and Windrip, but the two leaders were able to quash such canards by appearing together at the great reception given to Bishop Cannon by the Woman's Christian Temperance Union and being photographed shaking hands.

Each of the two pioneer universities started with an enrollment of fifty thousand, making ridiculous the pre-Corpo schools, none of which, in 1935, had had more than thirty thousand students. The enrollment was probably helped by the fact that anyone could enter upon presenting a certificate showing that he had completed two years in a high school or business college, and a recommendation from a Corpo commissioner.

Dr. Macgoblin pointed out that this founding of entirely new universities showed the enormous cultural superiority of the Corpo state to the Nazis, Bolsheviks, and Fascists. Where these amateurs in re-civilization had merely kicked out all treacherous so-called "intellectual" teachers who mulishly declined to teach physics, cookery, and geography according to the principles and facts laid down by the political bureaus, and the Nazis had merely added the sound measure of discharging Jews who dared attempt to teach medicine, the Americans were the first to start new and completely orthodox institutions, free from the very first of any taint of "intellectualism."

All Corpo universities were to have the same curriculum, entirely practical and modern, free of all snobbish tradition.

Entirely omitted were Greek, Latin, Sanskrit, Hebrew, Biblical study, archaeology, philology; all history before 1500—except for one course which showed that, through the centuries, the key to civilization had been the defense of Anglo-Saxon purity against barbarians. Philosophy and its history, psychology, economics, anthropology were retained, but, to avoid the superstitious errors in ordinary textbooks, they were to be conned only in new books prepared by able young scholars under the direction of Dr. Macgoblin.

Students were encouraged to read, speak, and try to write modern languages, but they were not to waste their time on the so-called "literature"; reprints from recent newspapers were used instead of antiquated fiction and sentimental poetry. As regards English, some study of literature was permitted, to supply quotations for political speeches, but the chief courses were in advertising, party journalism, and business correspondence, and no authors before 1800 might be mentioned, except Shakespeare and Milton.

In the realm of so-called "pure science," it was realized that only too much and too confusing research had already been done, but no pre-Corpo university had ever shown such a wealth of courses in mining engineering, lakeshore-cottage architecture, modern foremanship and production methods, exhibition gymnastics, the higher accountancy, therapeutics of athlete's foot, canning and fruit dehydration, kindergarten training, organization of chess, checkers, and bridge tournaments, cultivation of will power, band music for mass meetings, schnauzer-breeding, stainless-steel formulæ, cement-road construction, and all other really useful subjects for the formation of the new-world mind and character. And no scholastic institution, even West Point, had ever so richly recognized sport as not a subsidiary but a primary department of scholarship. All the more familiar games were earnestly taught, and to them were added the most absorbing speed contests in infantry drill, aviation, bombing, and operation of tanks, armored cars, and machine guns. All of these carried academic credits, though students were urged not to elect sports for more than one third of their credits.

What really showed the difference from old-fogy inefficiency was that with the educational speed-up of the Corpo universities, any bright lad could graduate in two years.

As he read the prospectuses for these Olympian, these Ringling-Barnum and Bailey universities, Doremus remembered that Victor Loveland, who a year ago had taught Greek in a little college called Isaiah, was now grinding out reading and arithmetic in a Corpo labor camp in Maine. Oh well, Isaiah itself had been closed, and its former president, Dr. Owen J. Peaseley, District Director of Education, was to be right-hand man to Professor Almeric Trout when they founded the University of the Northeastern Province, which was to supplant Harvard, Radcliffe, Boston University, and Brown. He was already working on the university yell, and for that "project" had sent out letters to 167 of the more prominent poets in America, asking for suggestions.

0 notes

Text

Chitra-Lekha, Raja Ravi Varma

Varma, Raja Ravi. 20th Century. Chitra-Lekha. Ink, Oleograph on Paper. Ghatkopar: India.

Accessed from: “Print | British Museum.” n.d. The British Museum. Accessed October 9, 2023. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1990-0707-0-20.

0 notes

0 notes

Photo

These lovely paintings of hindu dietes envisioned in this mesmerising oleographic paints on canvas are available on our website…

.

.

Shop now on www.yellowverandah.in

#oleograph #painting #oilpainting #canvas #fineart #art #artgallery #artistic

0 notes