#peat is a fucking work of art

Text

A Fortpeat Gifset | 彼岸 Music Video (Part 2)

#fortpeat#fort thitipong#peat wasuthorn#彼岸 MV#the holiday meetcute fantasy#peat is a fucking work of art

56 notes

·

View notes

Note

NOT VIV COMPARING HELLUVA’S “ARTISTRY” TO JOHN WATERS IN HER LIKES

Anon you opened up the fames of fury in me lol, so da tweets 🤌:

╭( ๐_๐)╮ can I just break from the critical side of myself and just be a "hater" and call pure BULLSHIT on these tweets. I aint even going to go into full structured critical analysis on these tweets this post of mine will be long winded rambles. This user is just pulling all these nuanced and highly revered genres in art and film ha even highly renowned filmaker, artist, actor and writer John Waters, JOHN FLIPPING WATERS and saying Brandon Roger *is* his equivalent on the YT front, thats disrespectful thats John Waters have respect tsk. Also none of those genres is the 1st thought in my head when thinking about the hellaverse (gags) and that it draws from.

Cabaret surrealism

Goth comics

Camp genre movies (a lot of examples)

And of course Brandon Rogers *is* home grown John Waters

This John Waters (ಠ_ಠ)

These tweets are nonsense I'm sorry but damn it is. Big hoity-toity words used and using comparisons thats just nonsensical and again lets just throw in queer people. Like how this tweet says the hatedom is teenagers or young 20-somethings or YOUNG QUEER PEOPLE 🙃🙃🙃. Im 26 queer as hell and I dislike helluva boss and it should cater to my age range but besides that can we for the love of peat stop invalidating the opinions of young people like I'm serious fuck off if you think like that.

I have had conversations and interactions with teenagers, young people and young queer people that wow the things I learn from them, its simply amazing.

And just love how Viv liked a tweet of someone invalidating the opinions of young people just because they young and just "haters" on Helluva boss, young people are people too. They have the right to voice their opinions so stop invalidating it and stripping away their agency aswell because this person is dictating on young queer people on their say on what they want to see better in queer media, that is not your decision to make on their behalf, if they criticise Helluva boss and hate it thats their decision to have stop guilt tripping them on their dislike of helluva boss because Viv is some modern maverick in queer media, she aint.

Viv's queer works DOES NOT compete with the true mavericks in queer media through the ages. Viv's work is a shallow and poor at its attempts in showing queer stories, representation and its handling of sensitive and queer themes.

Vivienne's creations are problematic, it is can exist but I like many others across all walks of like, status and age is going to call her work out for the bull is pumping out.

In all just another bootlicking tweet sucking up to Viv on how revolutionary her works are, how youngsters are too immature to see its pioneering effors in modern queer media and how helluva boss is groundbreaking in the themes/genres it draws from and the artists it has involved is comparable to the greats

...

its all BULL TO THE SHIT.

93 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I'm the person that made the rant post about my dislike on the lack of natural dichotomy of the Pyramids and Traveler since the introduction of the Veil that turned into a whole thing. You mentioned a lack of pulp in your reblog and it's stuck with me since then. I wasn't familiar with the term and did some research on it, but I still don't think I get what it is. I tried looking it up but a lot of articles and videos I could find explain the history of pulp and its influences in modern day sci-fi but not necessarily what it is, especially in a way that would give me context to better understand your reblog. If it's not too much trouble, can you explain a little more what the "pulp" is that destiny is lacking?

I’d be happy to try and give you a little more insight into what I feel are important tenets of pulp as a genre/concept! I decided this might be a good opportunity to talk a little about it generally because I am really feeling its absence generally in the past couple years, so I included some historical backing which you’re probably already familiar with – hope that’s OK.

I did a little digging personally, for some good places to familiarize oneself with the basics of pulp as a concept and/or genre. It was nice to re-affirm some info that I’ve felt secure in holding as true without a ton of evidentiary support, and I also learned some cool new stuff as well! I think a good place to start would be to link to the TV Tropes page about pulp magazines, which does a pretty good job of explaining the origins and foundational aspects of the concept in a way that is easy to digest. It also has a lot of examples available to peruse. I also found this cool article on the golden age of pulps, which is an interesting read.

This got long, so below the cut!

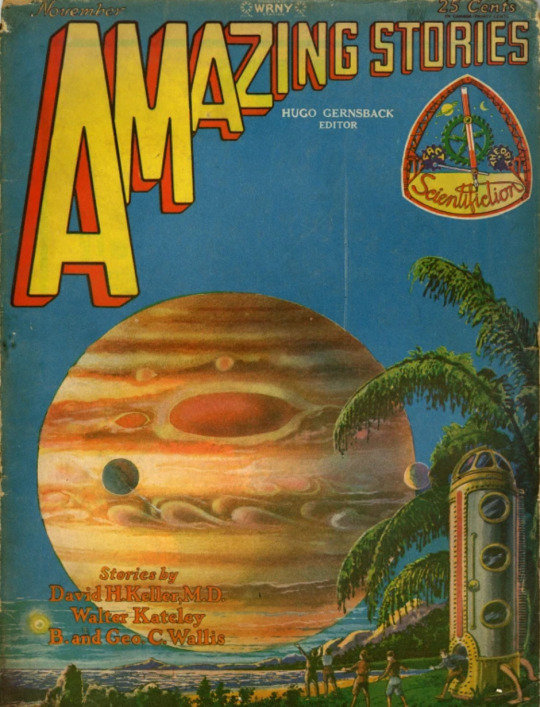

To reiterate, the original ‘pulp’ terminology and vibe comes from early/mid-20th century magazines, which were cheap and easy ways to access genre fiction and action/adventure stories before comics, paperback novels, and TV/movies were really on the scene. Pulp magazines spanned a very wide array of genres, but because of a lack of appreciation for the medium, a majority of pulp magazines and aspects of what I would consider to be pulp as a genre have been allowed to fall into obscurity. There are places where I feel it is particularly obvious, especially the superhero genre (don’t get me started we’ll be here all week) but also in fantasy and science fiction – a term which was, in fact, coined by Hugo Gernsback, an editor for pulp magazine Amazing Stories.

They were cheap to make, cheap to buy, and easy to serialize; they could be really schlocky, crass, and unpolished. They could also be fucking incredible! The Shadow is a good example of an early pulp property with screaming highs and frankly peat-bog lows. Lovecraft published a lot of what is considered to be his ‘best work’ in Weird Tales! Conan the Barbarian, too! They kind of came out of the gate with a somewhat negative connotation associated with ‘low-brow’ forms of literature like dime novels, but where other magazines of the time tended to incorporate non-fiction articles and photography, pulp mags tended to be fiction stories only – short stories, or longer stories split into serialized chapters. Early on, not many of them had art, though with the advent of comic books that changed (you could argue that books like Creepy and Eerie are direct offspring of early pulp mags). Similar to what Weekly Shonen Jump does with manga.

If you think of a genre as a toolbox, pulp is a box full of tools that function fine alone, but excel at assisting the function of other toolboxes. I would almost liken ‘pulp’ to the concept of ‘camp’, which are also two concepts that can and do overlap with a high degree of synergy. Pulp has its own foundational attributes that are distinct from camp – for example, camp is gay relies a lot more on its self-awareness, at being able to wink at the viewer or participant, and telling you ‘yeah, we know it, but isn’t it fun?’ Pulp, on the other hand, is the (no pun intended) straight man counterpart to this aesthetic sensibility; pulp is at its best when it is being completely earnest. The quippy lines and dramatic proclamations are meant to be taken on their face. Nowadays it’s the kind of stuff that memes are made of – ‘That Wizard Came From The Moon’, ‘I don’t have time to explain why I don’t have time to explain’, ‘Whether we wanted it or not, we’ve stepped into a war with the Cabal on Mars’. Saying shit that has no explanation with your whole chest. Trying to be cool on purpose, the ultimate cringe move.

Nowadays I think that this kind of thing has mostly died out of modern media, but the counter-motion is still prevalent in mainstream superhero movies. A good example is the ‘Would you have preferred ~YeLlOw SpAnDeX~’ line from the OG X-Men movie. Hey dickhead! The yellow spandex is cool if you, the guy making the movie, believes its cool! Crucially, while a lot of modern superhero stuff is quippy and irreverent, it often uses these tropes in a self-aware or cynical manner – afraid of being earnest, committing the aforementioned cardinal sin of trying to look cool on purpose.

(God damn it, I’m talking about superheroes again. Sorry. Before I get back on task this is why I loved the recent Moon Knight run so much; Jed MacKay is NOT afraid to have the characters say some absolutely batshit thing but it comes off as so, so cool. And yes, a little cheesy.)

And then, where modern sci-fi typically has an ultra-detailed explanation on-hand, I think a lot of early pulp stuff just… didn’t. Ask a sci-fi property for an explanation on, oh I don’t know, ‘where did these super-humanoid sapient machine warriors come from’ and it will likely have a molecule-deep explanation of how those unnamed machine people were created. Ask a fantasy property for an explanation on the same and it might say, ‘no’. It’s not that a pulp-leaning property won’t give you the answer to that question… it just might not have it. The ‘why is it/how is it’ is not as important as the ‘what is it’ and ‘how is it relevant’; a writer had a limited amount of page real estate, as multiple features were typically crammed into a single magazine. Even if a feature was serialized, much like television episodes (before the binge trend), one had to keep information digestible, and not too reliant on a prior or later edition that a reader might never see.

Explanations tended to be in service of an emotional beat, or to a theme, versus as a grounding agent to immerse a reader in the world. For the record I don’t necessarily think of either method as being better or worse, and heavy worldbuilding can still utilize pulp as a veneer or filter to engage audience expectations in different ways. Pulp stuff relies a lot on suspension of disbelief without utilizing a rigid lore-based framework to – though, you know, your story/setting still has to have its own internal logical consistency.

(I feel that it is important to note, as a partial consequence of the time period in which these magazines were being made, and when pulp fiction was most heavily consumed, xenophobia and racism are also heavily present in pulp works. I think everybody knows at this point about how much Lovecraft sucked but it’s a valuable example of how a lot of ‘fear of the unknown’ in that time was transliterated into ‘fear of the different’, in general but especially relating to genre fiction. If you decide to explore material in this genre, in this time period, be forewarned! Some of it was pretty glaring!)

So, let me tie some of this stuff to my previous statements about Destiny. I think that Destiny is an excellent example of how pulp tropes, aesthetic, and genre conventions can be used to enhance and streamline a setting… and how stripping too much pulp away can have a detrimental impact on the depth of a narrative.

The original narrative and worldbuilding of Destiny drew very heavily on pulp aesthetics to create a foundation, both in its appearance and its lore. The ‘Golden Age of Science Fiction’ was a period of time in the mid-20th century that sort of transitioned sci-fi out of pulp magazines and into its own thing, but the foundational structure of science fiction at this time was still heavily pulp-influenced. I think this is very well-represented by the portrayal of Venus as a ‘garden’ (jungle) world, very lush and with sulfurous and sometimes acidic rains. Before advancements in astronomical technology went and fucked everything up for us writers, Venus’s opaque cloud-covered atmosphere was impenetrable enough that there could be anything under there – and a popular portrayal of Venus was a muggy, humid, rain-heavy world that sometimes also included lush jungles. In Bradbury’s short story The Long Rain (WHICH ran in Planet Stories, a pulp mag, by the way!) this portrayal is a central obstacle to the narrative; it’s also used in Heinlein’s novel Space Cadet.

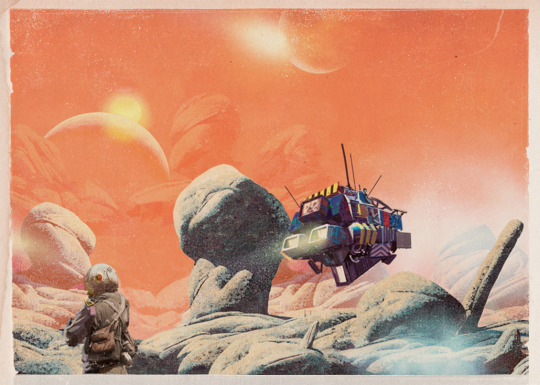

The color scheme that Destiny uses for Venus also matches a common color scheme for Venus in this era – see this cover for Fantastic Adventures. Visually, I think that this comparison between the postcard that went out with the D1 limited/collector’s edition and this Planet Stories cover for The Golden Amazons of Venus demonstrates the influence, at least regarding terrain and biome.

In fact, I think that you can see from this Eververse postcard – which could have been peeled off of any era-appropriate paperback novel – that the influence goes bone-deep. Destiny even refers to humanity’s halcyon age as ‘The Golden Age’.

(Below: Is this image from Destiny dev, or a science fiction paperback from the 60s? Who knows! I know. It’s Destiny.)

In the modern era of Destiny storytelling, though the visual elements of the universe remain largely rigid relative to this early framework, the pulp underpinning of the narrative has been largely left behind. The original game’s story, and the stories of subsequent DLCs, felt very pulp-inspired – this ranged from ‘sort of effective’, like in House of Wolves, to ‘game-savingly effective’, like in The Taken King. Pulp lends itself to straightforward conceptual executions, and brisk narratives, because of its roots as short-form literature. The narrative of D1 was simple and to the point; Light good, Dark bad, humanity is in the shit, think you can kill a god? The surrounding world scaffold was rich but not deep. As I like to say, sometimes a river can be wide but shallow. This is not a commentary on its quality – something can be good but not complex, and IMO, sophistication is not necessarily synonymous with complexity. Destiny managed to pull off a trick that many high-quality pulp stories employ: it made the river look deeper than it was. This is the whole reason that Lovecraft’s oeuvre has the staying power it has: other writers got to play in the space because it felt very deep, even though the stories themselves were fairly straightforward.

I also don’t mean to say or accidentally imply that ‘morally grey storytelling cannot exist within pulp stories’, because that would probably get me torn apart; that’s just not the kind of straightforward foundation that the original Destiny was built on. ‘It is what you see, but what you see could be anything’, you know? The problem that began to muddy the waters in the Destiny narrative is that they started to say, ‘You know, actually, it ISN’T what you see’.

Tentpole narrative additions to the Destiny 2 game employ varying levels of pulp. As I said in the other post, the Hive have a potent pulp influence built into their foundational coding, and so subsequent portrayals of the Hive as a main antagonist have higher degrees of pulp genre naturally present in the narrative – it’s hard to separate the two of them. Shadowkeep and The Dark Below draw strongly on the ‘sword and sorcery’ convention, a subgenre of fantasy that is a heavy (perhaps 1:1) blend of fantasy and pulp; think Conan, or Elric of Melniboné (who, hey! Showed up in a novella feature, in an issue of Science Fantasy magazine, named… THE DREAMING CITY). The Witch Queen leaned away from pure sword and sorcery and more towards noir/detective pulp – though, I think, TWQ is a good example of the pulp slippage in its narrative, resulting in some more bland moments and things that feel ham-fisted in a bad way. Part of it, I think, is the need to make these expansions ‘long’ and complicated without making the player feel like they’re slogging; in a more pulp-forward TWQ narrative, the reveal that Savathûn is actually NOT evil-aligned and is a potential ally would come much earlier in the story, and the central mystery would be MORE about ‘what the fuck is she trying to do/prevent’, leading to the Witness reveal as the centerpiece of the finale and the ‘solution’ to the central mystery.

The decision to start retroactively appending more complex connections between disparate pieces of content naturally leads to a reduction of pulp prominence, in my opinion. If you imagine Destiny as a vessel that is mainly full of three component liquids – Fantasy, Sci-Fi, and Pulp – you can say that adding more of one genre pushes out another to make room. You can always pour more of one genre in to re-balance, but in response to increasing levels of sci-fi the narrative seems reticent to reintroduce pulp back into the mix, instead favoring fantasy. But another problem is that once you take it out, Pulp is really hard to put back; once you solidify and unionize world-lore, every subsequent retcon risks diluting and destabilizing that world-lore until a) nobody cares about it anymore and b) it stops being mutable at all, and becomes sludge.

The lore behind the existence of the Exo was originally very pulp, with no real explanations given for exactly what they were and where they came from, and how they attained sapience. Early hints that Cayde and a few other Exo having once been human didn’t preclude other Exo from having other origins – for example, implications that Exo war-frames eventually achieved sapience as a result of the ‘Deep Stone Crypt’, and that they were originally simple AI-equipped warriors designed and overseen by Rasputin to minimize human casualties. This early mystique around the origins of the Exo is classically pulp: we don’t need to know how the hyper-advanced robots were made, we just need to know what they are, why they are relevant to the story. It allows You, The Player, to engage with it at whatever level you want. In a game where You, The Player, are also being asked to step into the role of You, The Protagonist, this is beneficial to engagement for people (like me!) who like to think too much about the backstory of the your-name-here protagonist on-screen. It is also beneficial to not distracting the player with conflicting information, or accidentally contradicting previously-established lore.

Enter Big-Head Bray. The Beyond Light-era explanation of why Exo were created and how they were made is a retroactive nuclear strike on the Exo lore; it strips away a lot of flexibility and thematic richness from the concept of the Exo, shoehorns them into a single narrow use case, and directly conflicts with early-game Exo lore implying their connections to Rasputin (which they then had to go back and hastily shoehorn back in later) or existence as war machines for the Collapse. If D1 lore is wide but shallow, the D2 lore is narrow but deep. Just because something has a lot of ‘depth’, I.E. many layers to traverse before you reach foundational bedrock, it doesn’t make it good.

Same thing with the Fallen. Season of Plunder felt to me like an attempt to reintroduce pulp genre back into the setting, but it fell flat because of two reasons: it didn’t really want to be pulp, and it was more concerned with its tethers to the science-fantasy exterior world than it was with creating its own cohesive narrative. Why was Mithrax doing evil pirate shit when he was young? Because he comes from a race of fucking evil space pirates! It Does Not Need To Be More Complex Than That! But the exculpation of pulp from the D2 narrative means that if Mithrax doesn’t have a good enough reason, WRT the larger narrative, it would be a glaringly obvious plot hole. By Plunder, Destiny had already undertaken the task of filling out the Eliksni lore with sympathetic science-fantasy excuses for why they were trying to exterminate humankind – the more earnest, pulp-forward explanation would just be that desperate, hurt, suffering people will do desperate things, hurt people, and may perpetuate the cycle of suffering.

Oy. There’s a lot you COULD get into. How the Destiny macro-narrative seems to be decaying the rigidity of good and evil in its original lore vs. how the micro-narrative is obsessed with trying to recapture that good/evil dichotomy in order to give players a reason to like the main characters. How the determination to connect and explain everything has resulted in a general flattening of the background lore, and the subsequent trivialization of many things the game included in earlier iterations of the narrative/lore. How the narrative has basically nothing to do with the Vex because they wrote themselves into a corner by trying to explain them too much while simultaneously not altering the foundational lore of the race, meaning there were too many things they can no longer do without retconning again.

Overall, I guess I will just end by saying that many of the things that Destiny is CURRENTLY doing, feels like the game is straining to rip the part of it out which proudly asks its audience not to think too hard about sweeping, dramatic statements that built a lot of the things people love about the game’s setting and narrative… and in doing so, is just ripping itself to pieces.

#More lore! MORE LORE!#dinklebot sitcom#northbot sitcom#destiny 2#Pulp genre#Genre discussion#Sorry this got so long! I’m not used to writing this kind of big essay#it may not be super coherent but whaddya gonna do

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

2023 Reading Log pt. 4

March was hard for me, both in terms of my personal life and in terms of my reading. I started a whole bunch of books that I haven't finished. Some of them I intend to come back to (two monster books, one for RPGs and one reference book). The ones I intentionally gave up on are listed here, as well as the whys of why I gave up on them.

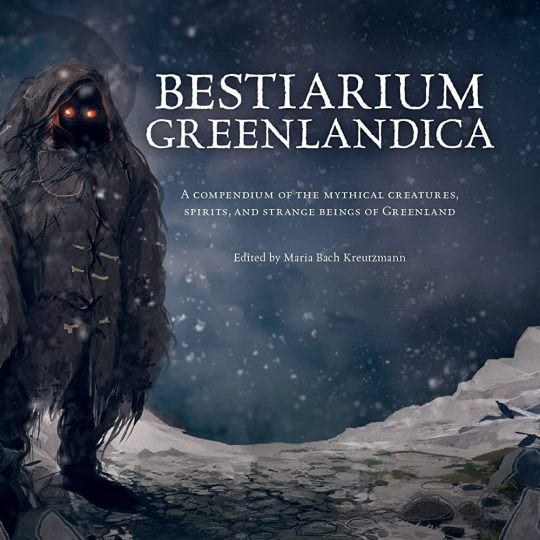

16. Bestiarium Greenlandica, edited by Maria Bach Kreutzmann. Recommended to me a while ago by @abominationimperatrixx, but I have only been able to get a copy recently. This is the second edition, put out by Eye of Newt Press, which seems to specialize in publishing monster books with previously limited print runs (they also have an edition of Welsh Monsters and Mythical Beasts by C G J Ellis, for example). This book is an A-Z look at mythical creatures from Greenland, which entails a peek at traditional Thule culture. Anggakutt (the equivalent of shamans) use various monstrous spirits to guide them through the spiritual realm and work wonders for them, and these have to be negotiated with or even battled in order to recruit them. So there’s plenty of monsters, many of which are very obscure in English language sources, or confused with other creatures from other Inuit cultures. The book has illustrations for most of the monsters, some line drawings and some full color paintings. All of the art is great, and it doesn’t shy away from the sex and violence in the myths. So a trigger warning is at play if dead and decaying fetus monsters, ghouls with giant penises, or all manner of grotesque facial features are not your thing. But if you’re okay with those, this book is highly recommended.

17. Bog Bodies Uncovered by Miranda Aldhouse-Green. This book looks at the various bodies that have been discovered in peat bogs throughout northern Europe, and is primarily concerned with why these people were killed and placed in the bog. After a discussion of the history of finding bog bodies, and about the nature of bogs and how the tannins contribute to preservation, the book is primarily a forensic investigation. Its ultimate thesis is that most of the bog bodies represent intentional human sacrifices by Celtic and Germanic people. The author does a good job of supporting that claim, although her extrapolations and speculations go a little far for my taste (especially when she conjectures that the Lindow Man was sacrificed because of a specific battle written about by the Romans). The book features a mix of black and white photos and illustrations with color plates, which is always appreciated for a book about physical artifacts.

17a. Bad Gays: A Homosexual History by Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller. I gave up on this one around the halfway point—much longer than I typically go into a book I decide not to finish. That’s because I really wanted to like this one, but couldn’t. The subject is how queer history has often been sanitized and gay historical figures made saintly, when in reality there were plenty of unremarkable and some downright evil gay people as well. The book also wants to aim a giant fuck you at respectability politics, arguing for radical queer liberation and that the current state of gay representation is rooted in capitalism and patriarchy. It also also wants to make snarky quips about gay kings and military leaders—this is a very distant priority. I agree with the book’s politics in the broad sense, and there’s just enough quips and history to have kept me interested this long, but the overall feel of the book is very preachy, and not actually that interested in the lives of the individual subjects. There are ways to make a book both stridently anti-capitalist and an entertaining read, and this one fails.

17b. How Far the Light Reaches by Sabrina Imbler. I stopped this one a few pages into the second chapter. I was looking for a book about marine life and fun facts, and this has that, but is interwoven with personal memoir and is much heavier on the memoir. The first chapter is about how goldfish are stunted in fishbowls, but can grow to enormous sizes in the wild and can act as an invasive species. And this is contrasted with the author feeling stifled by small town life and realizing that they’re queer upon growing up. That was fine, but the second chapter draws connections between how mother octopuses starve themselves watching over eggs, and the generational eating disorders that the author and their mother dealt with. My mood couldn’t handle that. Maybe I’ll come back to this book when I’m in a more secure mental place, but I didn’t feel like crying while reading again. Not for a while—I think my allotment is one sad book a year.

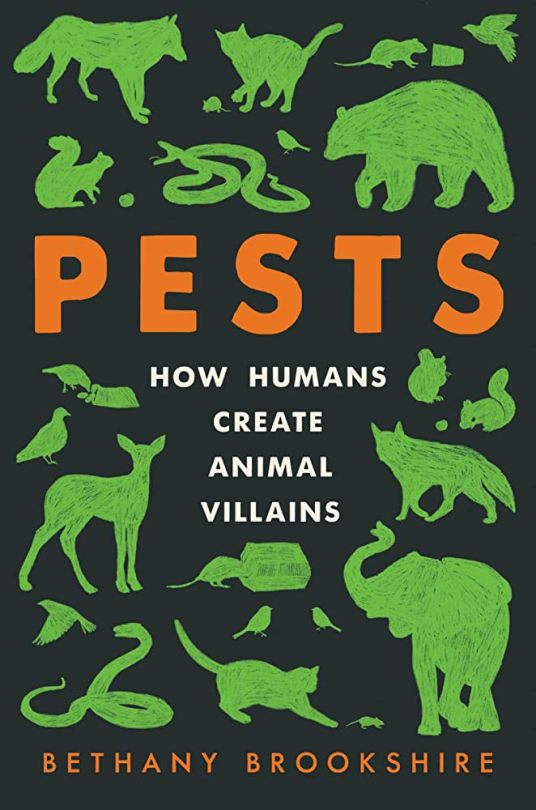

18. Pests: How Humans Create Animal Villains by Bethany Brookshire. This feels like a companion volume to Mary Roach’s Fuzz. Both books are about how humans behave when animals get in their way, but Fuzz deals more with the humans and Pests deals more with the animals. There’s lots of evolution and ecology material here, including very recent research, like the possible link between the evolution of house mice and the contents of their gut flora, and a modern look at how Australia’s ecosystems are reacting to and coping with the introduction of cane toads. This book is much more the balance of science to personal experience that I was looking for right now, and I had a good time with this one.

19. Ancient Sea Reptiles by Darren Naish. I’ve been looking forward to this book since it was first announced, so I’m happy to report that it’s as good as I was hoping. The book discusses Mesozoic marine reptiles (with some guest appearances from Permian taxa, like mesosaurs). First, it goes through the history of their discovery and some overview of their anatomy, physiology and evolutionary relationships. Then, it goes through the clades. Ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, mosasaurs, marine crocodiles and sea turtles get their own chapter, and all the other groups, from weird Triassic one-offs to sea snakes, are compiled into a single chapter. Naish is one of my favorite science writers, as he combines a phylogeny-centric approach for an appreciation of the novelties and weirdness of specific genera. I would love it if he wrote a similar book about another group for which books for educated laypeople are thin on the ground, like stem crocodiles or non-mammalian synapsids.

20. Effin’ Birds by Aaron Reynolds. This is the book form of a Twitter feed, which I appreciate from a historical perspective. The feed, and the book, have two main jokes. One, pictures of birds with profanity as captions. Two, faux descriptions of bird behavior and habitats that are jokes about common types of unpleasant people, or people who avoid unpleasant people. I got a few laughs out of it, but I’m glad that I got this book from a library and would not pay money for it. The funniest thing about this book to me is that that selfsame library put it with the books about bird biology and field guides, when there is zero informational content in this book, combined with the book itself making a joke about how you’d never find this book in a library.

#reading log#what are birds#twitter#marine reptiles#paleontology#cladistics#pests#invasive species#biology#marine biology#memoir#gay history#lgtbq history#european history#bog bodies#monster books#greenland#greenland folklore#inuit folklore

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can I have an MC with really bad anxiety? Like not social but more like she cant even sit in her bed alone in the dark? You're doing really great so far, keep up the good work!

of course! also thank you!!!

i always get motivated for this one in the middle of an anxiety attack lolololol

TOTALLY NOT LISTENING TO HALLOWEEN MUSIC TO MAINTAIN MOTIVATION

zen

it was a quiet night

you had just had the busiest week of a hectic month

so you got a little clingier with zen

he enjoyed it happy to have some relax time

the phone was ringing in the other room making zen have to leave to grab it

this already made you nervous

who was calling in the middle of the night

with zen gone you didn’t feel safe

at any gust of wind you jumped

at any creak in the house you jumped

any noise sent your anxiety off

you couldn’t stop thinking of what could happen

you were so deep in your thoughts you didn’t notice zen in the kitchen

he suddenly dropped a glass and you couldn’t stop you anxiety

you thought unknown was going to get you again and you started to cry and hyperventilate

you just couldn’t control your thoughts

luckily zen noticed and came over to you and pulled you close

“hey babe I’m here! i just dropped a glass I’m sorry it scared you!”

you just hug him tightly thankful it wasn’t who you thought it was

you just cry for a bit shaking

he whispers sweet words to you rubbing your back comforting you

he knows about your anxiety as he probably had to help comfort you

yoosung

you two were playing a horror game of your own request which was surprising to him

it was mainly to do with the fact you were tired of feeling like a burden

you were doing great albeit your anxiety making you stiff as a board

you were really fighting it

you just cant do getting chased or jump scares

after the first game you are feeling confident even though you are shaking badly

yoosung was too

he was allowed to pick the game tho

he happens to love the thrill of jumpscares

its that boost of energy for school lololol

he pick five nights at freddy’s

you falter

you start playing shaking so much

with his help you get to the second night

you try and alternate between him taking over when a jumpscare is near

and this works till like the 4th night

when you all get distracted

theres suddenly a jump scare that makes you scream

you curl in on yourself shaking and crying mind wandering making it worse

doesn’t help you like to look up the theories and then you get freaked out

you then are thinking about how stupid it is that a game is making you freak out but he doesn’t think so

he grabs his favorite blanket and his hoodie that you love

he rushes to get tea going and he quickly puts on cute animal videos while you are at the compute and has you get up so you can both sit there

you on his lap

this helps distract you and you laugh sniffling at the silly kittens

next thing you know you are asleep on him and he doesnt know what to do

jaehee

your school has really been taking a toll on you

you never thought how hard it would be to major in theater

sweats nervously

you have to practice a monologue but you also have all you academic work to do

as you are working on it you check the time and how much is left

its now 3 in the morning and barely finished and you still have that monologue to practice that’s due tomorrow

you start thinking of the worst and begin to shake crying silently

jaehee wouldn’t have noticed if it weren’t for the fact you dropped a glass by accident trying to calm down

that made it worse because now you think thats more work and how it upset jaehee

but she simply cleans up the mess and gives you slippers in case any stray glass got anywhere

she makes some tea for you to calm down and gets you a blanket and plays some recordings of zen singing because that’s what helps her

she gives you a hug and a kiss and makes sure you are ok and decides to help you with the work

jumin

you were in the penthouse playing with Elizabeth while he was at work

you were having an amazing time till the power went out

you completely freeze up

you werent aware that you werent breathing till you needed to breathe again

you were just frozen

you shut your eyes tightly like you were taught when you were younger when scared of the dark

you didnt have a blanket to hide under and you didnt want to move

you were thinking of all the things that could be lurking in the dark and start rocking crying

elizabeth worries about yoy and brushes against you meowing and you sit crisscross applesauce so she can sit on your lap

you peat her and she purrs comforting you

suddenly the door is opened making a loud noise and she runs to greet the familiar face but it just made your anxiety worse

you rock again thinking its someone whos going to kill or kidnapp you for being the heirs wife

“sweetheart? its me jumin? your husband?”

he goes over to her with a flash light and he sits down next to you pulling you into his chest whispering to you to calm you down planting kisses to your temples

you hug him tightly glad to have him right now

the power comes back on and you don’t want to let go

hes fine with this

707

you were on the computer writing things on tumblr

when suddenly its hacked

you cant get all these freaky things of your computer and you are panicking crying

there were quiet a few nsfw things

some of which hit a few triggers

you scream for seven

he had been teaching you computer things but your anxiety wont let you think clearly

you keep telling yourself that if you were calmer you can fix it and not need his help

when he comes rushing in you try to explain and he pushes up his glasses telling you hes serious thankfully

you are still panicking though anxiety running rampant in your head

you feel bad because he deals with his brothers mental illnesses enough he doesnt have to deal with yours but he honestly doesnt mind

he shuts down you computer and takes a part out of the computer it self

“well you couldn’t of fixed this it’s well hacked but has been for a while so we need to fix that but that can wait”

he says this knowing you used many unimportant accounts on that computer under his request

hes gets some tea going and wraps you in his jacket taking his headphones off playing relaxing nature sounds he knows helps you from watching your youtube history

and he just hold you close playing with your hair for a while

you are finally calm and he feels like a hero because he got to help you and saeran today

“im not called god 7 for no reason”

you smack him and just hug him

unknown

you were sitting on the bed with him and bad memories that cause anxiety hit

you normally try to handle it on your own away from him because he needs more help in you mind

but you just cant stop it

you and shaking badly trying to get the thoughts to go away

you hold your head desperate to calm down and rock

at this point he notices and knows whats going on and he pulls you close rocking

“hey you should tell me you go through it too i can help you like you help me…”

you just hug him and he hums slightly playing with your hair

its the most relaxing sound you’ve heard and you quickly calm down

“so what caused it?”

“i remembered what we went through to both be here where we are now”

he just looks sad and understanding now realizing it scarred you too

later he gets you flowers

v

you have one dark thought and you jump straight to the thought that you are becoming rika

this of course freaks you out and anxiety comes to say hi and try to spend the night

not today satan

your mind goes through all the ways you could possibly be rika

you curl up freaking out shaking and crying wanting to stay away from v so he doesnt find out you are “rika v2.o”

its too late

he rushes to you trying to see if you are ok

when you tell him you are worried you are gonna become rike he gives you this long talk about how you are nothing like her

hes just sitting next to you and he tells you to talk about your favorite subject to calm down

you choose art and he and you just chat about it for ages till you realize you are calm

you tell him hes fucking magic

“no haha i just did research”

you give him a smooch and say no you are fucking magic and he just laughs nodding

i hope this is ok? its like 4 in the morning and ive been suffering from con depression all day and plus i havent done an imagine in A G E S sorry for that writers block is a bitch

#mysme#mystic messenger#mystic messenger zen#mystic messenger v#mystic messenger jaehee#mystic messenger jumin#mystic messenger 707#mystic messenger yoosung#mystic messenger saeran#mystic messenger hyun#mystic messenger mc#mystic messenger unknown#mystic messenger luciel#mystic messenger ray#mystic messenger saeyoung

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

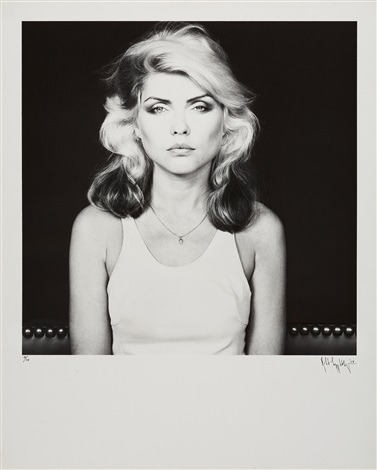

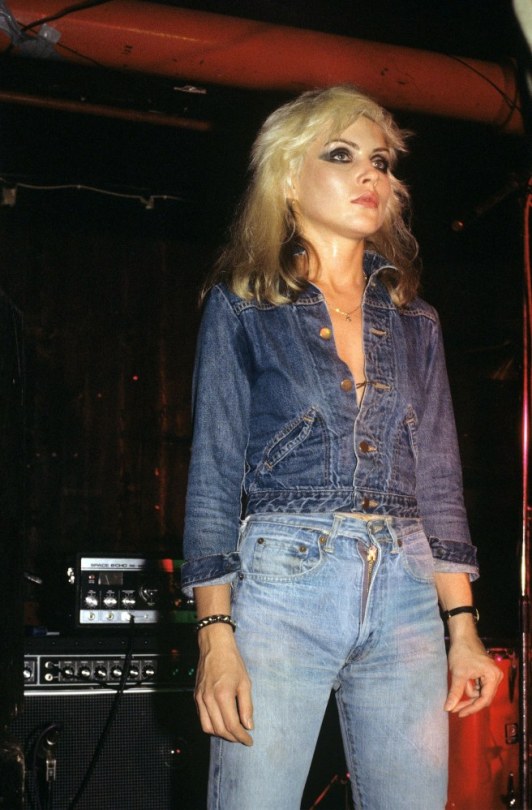

Jane’s World: Blondie – Parallel Lines

Hi. It’s Jane.

I’m locked on a summer track. That’s pretty rare for me because (a) I don’t like hot weather, and (b) I don’t generally like singles. More of a deep cut gal. But Blondie’s “Heart of Glass”? I can’t even stop. It followed me around town for a month. I heard it on the car radio, then at a party, then at another party, then at a club. Then on some curated playlist in the shower. Then at another party. And then at the freaking grocery store. That’s when I just succumbed to the goodness and started dancing and singing along in the produce section. My gf was not amused. When I put it on at home, she coined the term “fleek-peat,” and ok. Good.

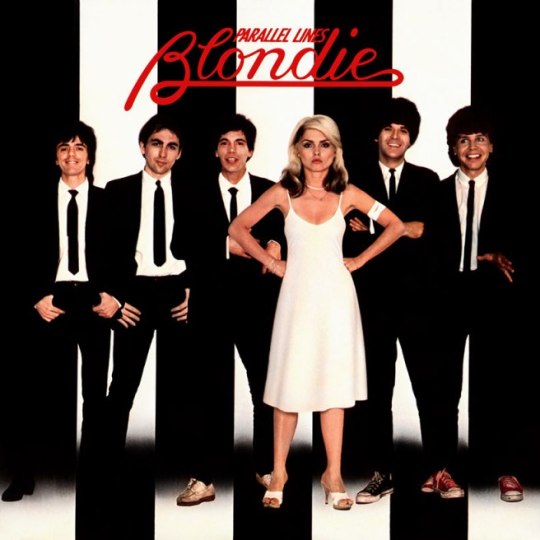

So we all know Deborah Harry and her band. They’re pretty famous, I guess. For “Heart of Glass,” and a handful of other songs. I always thought of them as a greatest-hits package. And that’s mostly true, but their 1978 record Parallel Lines is a masterpiece. It’s post-punk (before that was a thing), it’s new-wave (before that was a thing), it’s garage, it’s camp. It’s both CBGBs and Studio 54, if that makes sense. It’s a canny distillation of pop tropes from the ’50s and ’60s, in the context of ’70s NYC.

Blondie’s first two records struggled to find an audience. (“Rip Her to Shreds” off the self titled debut is wicked; “Denis,” a Randy & The Rainbows cover off the follow-up, Plastic Letters, is cute.) Their third did. Here’s Pitchfork’s Scott Plagenhoef: “The swift move from the fringes to the top of the charts tagged Blondie as a singles group – no shame, and they did have one of the best runs of singles in pop history – but it’s helped Parallel Lines weirdly qualify as an undiscovered gem, a sparkling record half-full of recognized classics that, nevertheless, is hiding in plain sight.”

Amen. And, apparently, it was a pain in the ass for everyone involved. Particularly, Aussie producer Mike Chapman. Debbie disliked him because “they were from New York, and he was LA.” The rest of the band disliked him because, well, they weren’t very good. According to the PL wiki, a primary source here, Chapman called them “the worst band he had ever worked with in terms of musical ability. He continued:

“The Blondies were tough in the studio, real tough. None of them liked each other, except [guitarist] Chris [Stein] and Debbie, and there was so much animosity. They were really, really juvenile in their approach to life – a classic New York underground rock band – and they didn’t give a fuck about anything. They just wanted to have fun and didn’t want to work too hard getting it.”

I mean, dude, who does? Eventually, Chapman’s influence yielded results in only six weeks. (The wiki talks about how he did a neat tape trick called “pencil erasing” to make the bass top the drum kick.) And he coaxed a virtuoso vocal performance out of Debbie by turning her attention to her “phrasing, timing, and attitude.” He didn’t bother with her New Yawk accent, and thank goodness. She’s all there. The lead track, “Hanging on the Telephone,” could’ve kicked off Patti Smith’s Radio Ethiopia from two years earlier. The only difference is the production. PL, as a piece, is shiny. All the edges haven’t been so much sanded smooth, as polished and emphasized.

(That’s a vintage Polaroid from Patti pal Robert Mapplethorpe. Check out her hair, omg.)

It’s such a kick-ass record. The guitar solo on “One Way or Another” is huge, and the incessant organ outro under Debbie’s vocals is the template for so much early ’80s music. “Picture This” seems like an Edith Piaf cover. “Pretty Baby” and “Sunday Girl” would’ve sounded great on the radio in the 1950s. “11:59” and “I’m Gonna Love You Too” would’ve sounded great on the radio in the 1960s. Total girl group pop. “Fade Away and Radiate” is Roxy-level art-rock. And “Will Anything Happen” is pretty happening, especially the jaw-dropping “if you do” slide into the chorus.

Plaggenhoef called PL “one of the most accomplished pop albums of its time.” I’d add of all time. Listen for yourself.

Oh. I can’t do a Spotify widget and a YouTube widget in the same post. Not sure why. The IT team is supposedly “working on it,” which means those jokers can’t figure out a solution. (Speaking of teams and solutions, the Outreach-and-Marketing team should figure out how to get me in touch with Debbie. She’s not getting younger, and I have many Q’s for her A’s.) Anyway, check out the beyond dreamy “Heart of Glass” video HERE.

Next month, I’m going to talk about Joni and grass. And the sooner that I finish, I can vacay. So it might be in a week or so.

Love to my gf and my dogs.

JTB

from WordPress https://ift.tt/2MpXlQ5

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Can We Ever Make It Suntory Time Again?

Aaron Gilbreath | Longreads | October 2019 | 23 minutes (5,939 words)

Bic Camera looked like many of the other loud, brightly colored electronics stores I’d seen in Japan, just bigger. Mostly, it was a respite from the cold. The appliances and electronics that jammed its interior gave no indication of its dizzyingly good liquor selection, nor did the many inexpensive aged Japanese whiskies hint that affordable bottles were about to become a thing of the past, or that I’d nurture a profound remorse once they did. When I found Bic Camera’s wholly unexpected liquor department, I lifted two bottles of high-end Japanese whisky from the shelf, wandered the aisles studying the labels, had a baffling interaction with a clerk, and put the bottles back on the shelf. All I had to do was pay for them. I didn’t.

Commercial Japanese whisky has been around since at least 1929, so during my first trip to Japan (and at home in the U.S.), there was no reason to think that all the aged Japanese whiskies that were readily available in the early 2000s would soon achieve holy grail status. In 2007, there were $100 bottles of Yamazaki 18-year sitting forlornly on a shelf at my local BevMo. One bottle now sells for more than $400 at online auctions; some online stores sell them for $700.

Yoichi 10, Yoichi 12, Hibiki 17 and 21, Taketsuru 12 and 17 — in 2014, rare and discontinued bottles lined store shelves, reasonably priced compared to their current $300 to $600 price tags. Those were great years. I call them BTB — before the boom. Before the boom, a bottle of Yamazaki 12 cost $60. After the boom, a Seattle liquor store priced their last bottle of Yamazaki 12 at $225. Before the boom, Taketsuru 12 cost $20 in Japan and $70 in the States. After the boom, online auctions sell bottles for more than $220.

Before the boom, Karuizawa casks sat, dusty and abandoned, in shuttered distilleries. After the boom, a bottle of Karuizawa 1964 sold for $118,420, the most expensive Japanese whisky ever sold at auction, until a Yamazaki 50 sold for $129,186 the following year, then another went for $343,000 15 months later.

Before the boom, whisky tasted of rich red fruits and cereal grains. After the boom, it tasted of regret.

I’ve spent the past five years wishing I could do things over. I remember my trips to Japan fondly — the new friends, the food and record stores, the Kyoto temples and solitary hikes — except for the whisky, whose absence coats my mouth with the proverbial bitter taste. I replay the time I walked into a grocery store in Tokyo’s Ikebukuro neighborhood and found a shelf lined with Taketsuru 12, four bottles wide and four deep, at $20 apiece; it starts at $170 now. I look at the photos I took of Hibiki 12 for $34, Yoichi 12 for $69, Taketsuru 21 for $89. I tell friends how I’d visited the Isetan Department Store’s liquor department in Shinjuku, where they had a 12-year-old sherried Karuizawa bottled exclusively for Isetan for barely more than $100, alongside a blend of Hanyu and Kawaski grain whisky that famed distiller Ichiro Akuto did exclusively for the store. Staff wouldn’t let me photograph or touch anything, but I could have afforded both bottles. They now sell for $1,140 and $1,290, respectively. I torture myself by revisiting my unfortunate logic, how I squandered my limited funds: buying inexpensive bottles to drink during the trip, instead of a few big-ticket purchases to take home.

Aaron, I’ve thought more times that I could count, you are such a fucking idiot.

To time travel, I look at photos of old Japanese whisky bottles in Facebook groups, like they are some sort of beverage porn, and wonder: Who am I? What have I become? There’s enough incredible scotch available here at home. Why do I — and the others whose interest spiked prices and made the bottles we loved inaccessible — care so much about Japanese whisky?

* * *

After the notorious Commodore Perry landed on Japanese shores in 1853 to open the closed country to trade, he gifted the emperor a barrel and 70 gallons of American whiskey, a spirit not well-known in Japan. As whiskey tends to do, it softened the nations’ encounter; one tipsy samurai felt so good he even hugged Perry. At the time, domestic spirit production was limited to shōchū and an Okinawan drink called awamori, made from sweet potatoes and rice respectively. Japanese companies tried to recreate the brown spirits that American and European companies had started importing, but without a recipe, the imitations were rough. The earliest Japanese attempts were either cheaply made locally or imported from Europe and labeled Japanese. When two boatloads of American soldiers stopped in the port of Hakodate in 1918, en route to fight Bolsheviks in Siberia, they found bars filled with knock-off scotch, including one called Queen George. As Major Samuel L. Johnson wrote in a letter, “If you come across any, don’t touch it. … It must be 86 percent corrosive sublimate proof, because 3,500 enlisted men were stinko fifteen minutes after they got ashore.”

It was in this miasma of bad imitations that Suntory’s founder Shinjiro Torii recognized an opportunity. Winemaker Torii had been importing whiskies and bottling them as early as 1911. He called his brand Torys. As whisky found a toehold in Japan, he realized that slinging rotgut like the other frontier opportunists wasn’t the way to create a market; he needed to learn to distill an authentic, higher-quality whisky. The way Suntory’s marketing materials later presented it, Torii wanted to create a refined whisky that also reflected Japanese natural resources and Japanese tastes, which he perceived as more attuned to delicacy and nuance than the Scottish palate and that paired with Japanese cuisine rather than overpowering it — anything that tasted of corrosive sublimate would overwhelm your food. In 1923, he used his wine profits to build a distillery near Kyoto.

Elsewhere, in Osaka, Masataka Taketsuru, the son of a sake-maker, had been working for shōchū-maker Settsu Shuzo. The company, like Torii, wanted to make whisky, so in 1918 its president sent Taketsuru to study whisky-making in Scotland. Taketsuru was a 24-year-old chemist and took detailed notes when the Scottish distillers finally showed him their facilities and techniques. After two years learning the art of cask maturation, pot stills, and peat-smoking, Taketsuru returned to Japan to find that his employer’s enthusiasm for making real whisky had waned. So Taketsuru took his Scottish knowledge and enthusiasm to Torii, and the two men pooled their skills to build what became the Yamazaki Distillery, the country’s first commercial whisky producer. Sticking with Scottish tradition, they spelled it without the ‘e.’

It must be 86 percent corrosive sublimate proof, because 3,500 enlisted men were stinko fifteen minutes after they got ashore.

Suntory gets all the credit for distilling Japan’s first Scottish-style whisky, but Eigashima Shuzō, the company that now runs the White Oak Distillery, actually got the first license to produce whisky in Japan in 1919, five years before Yamazaki. Founder Kiichiro Iwai, who later founded the Mars Shinshu distillery and designed its equipment, had been Taketsuru’s mentor at Shuzo and is often called “the silent pioneer of Japanese whisky.” But Yamazaki started producing whisky sooner, so the rest, as they say, is history.

Suntory’s Yamazaki distillery launched Japan’s first true commercial whisky in 1929. Ninety years later, around a dozen companies distill whisky in Japan, depending on how you count them: Suntory and Nikka. Chichibu in Saitama Prefecture, White Oak in coastal Akashi. Kirin at the base of Mt. Fuji, Mars Shinshū in the village of Miyada in the Japanese Alps. Upstarts like Akkeshi in Hokkaido and the Shizuoka Distillery near Shizuoka. All produce stellar whisky.

Whisky experienced a huge boom in postwar Japan, coming to represent success, the West, masculinity, worldliness, and Japan’s increasing importance on the world stage. “If you were to choose a drink to symbolize the rapid economic growth in the four decades after the war,” Chris Bunting writes in Drinking Japan, “it would have to be whisky.” In journalist Lawrence Osborne’s words, whisky was “the salaryman’s drink, a symbol of Westernized manliness and sophistication.” Initially, distillers flooded the domestic marketplace with mediocre blended drams and single malts that appealed to hard-working businessmen. Then Suntory relaunched Torys to reach the working-class masses; the stuff was cheap and tasted it, with a cartoon businessman mascot that the target demographic could identify with. Nikka also began producing different lines to offer Japanese drinkers an affordable Western luxury product. During the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, there was Hi Nikka, Nikka Gold & Gold, Suntory Old Whisky, and Suntory Royal. Many of these these brands used the same affectations as Scottish and English products: crests, gold fonts, aged labels, faceted glass decanters with boldly shaped stoppers, the British spelling of flavour. The approach worked. Whisky went from a drink of the well-to-do businessman to a drink of the average citizen, and it became common for working-class Japanese men to keep bottles at home. Production boomed.

In the mid-1980s, consumer drinking habits shifted toward shōchū, whisky lost its allure, and some distillers from the postwar boom years closed. But Keizo Saji, the second son of Suntory founder Shinjiro Torii, saw an opportunity: premium whisky. In 1984, the year domestic whisky consumption dropped 15.6 percent, Saji launched Yamazaki 12, Japan’s first high-end mass-market single malt, transforming a downturn into a chance for the company to outdo itself with top-notch quaffs that would raise whisky’s domestic reputation and compete with scotches in the global marketplace. Nikka followed suit with their own single malt. Historians usually date the true start of Japanese whisky’s global ascendency to 2001, when 62 industry professionals did a blind taste test for British Whisky Magazine and named Nikka’s Yoichi 10 Single Cask the year’s best. “The whiskeys of Japan proved to be a real eye-opener for the majority of tasters,” the magazine wrote. As the Japan Times reported the following year, “Sales of Nikka’s award-winning 10-year-old single-cask whiskey, which has only been sold online at Nikka’s Web site, surged from about 20 bottles a month in 2000 to 1,200 in November after several Japanese newspapers carried an article about the taste-test events.”

For a long time, the majority of Japanese whisky was made following Scottish distilling methods: Japanese single malts were made from 100 percent malted barley (mostly imported from the U.K.) with local mountain and spring water, distilled in pot stills, and matured at least three years in oak. Japanese single malts moved to casks made from American or European oaks and that once held bourbon to age further and take on color and flavor, usually for 10 to 18 years. Like scotch, these single malts were rich, wooded, and highly aromatic. But Japanese innovation also created an astonishing diversity of flavors that tradition would never have allowed. Distillers age their whisky age in casks that once held sherry, bourbon, brandy, ume, and port, and, on a more limited basis, expensive casks made from Japan’s native mizunara oak. Every culture has masters and apprentices, but the Japanese have a particular respect for craftsmanship, and many people, from coffee roasters to cedarwood lunch box makers, dedicate their lives to a single specialty. Whisky writer Brian Ashcraft told Nippon that there’s a word for this: “In the Meiji period [1868–1912] there was a slogan, wakon-yōsai, or Japanese spirit and Western knowhow. So even if a product made in Japan is superficially the same as one made overseas, it’s going to be something Japanese because of differences in culture, language, food, climate. … This applies to anything from blue jeans to cameras, cars and trains. There are elements of the culture manifesting in the finished product.” Sakuma Tadashi, Nikka’s chief blender, told Ashcraft that by liberating themselves from tradition and embracing innovation and experimentation, the company can continue to improve its whisky. “At Nikka,” Tadashi said, “it’s ingrained into everyone that we need to make whisky that is better than scotch. That’s why if we change things, then we can make even more delicious whisky.”

* * *

Like whisky aging in barrels, Japanese whisky producers’ international reputation took years to develop, but gradually medals started weighing down their lapels. In 2001, the International Wine and Spirits Competition awarded Karuizawa Pure Malt 12 a gold medal. In 2003, the International Spirits Challenge gave Yamazaki 12 a gold award. Hibiki 30 won the International Spirits Challenge’s top prize in 2004, Yamazaki 18 won San Francisco World Spirits Competition’s Double Gold Medal in 2005, and Nikka’s Yoichi 20 was named World’s Best Single Malt Whisky in 2008. The World Whiskies Awards named Yamazaki 25 “World’s Best Single Malt” in 2012. Hibiki 21 was named the world’s best blended whisky in 2013. And on and on.

I’ve harbored an interest in Japanese culture and history since fifth grade. When I discovered the anime Robotech — one of the first Japanese animated shows adapted for mainstream American television — I sat for hours in my room, copying images of robots, missiles, and sparkly-eyed warrior women into my sketchbooks. As I moved away from anime and manga, I read more broadly about Japan and fell in love with Japanese literature, food, smart technology, and the Toyotas that never died, like the truck that took me from Arizona to British Columbia and back two times. Naturally, Bill Murray’s now-famous line in Lost in Translation “For relaxing times, make it Suntory time” made me want to taste what he was talking about. So I ordered a glass of 12-year Yamazaki at a bar.

Lively and bright with a medium body, the Yamazaki had layers of orange peel, honey, cinnamon, and brown sugar, along with a surprisingly earthy incense aroma, almost like cedar, which I later learned came from casks made from Japan’s mizunara oak — Mizunara imparts what distillers call “temple flavor.” I kept my nose in the glass, sniffing and smiling and sniffing, no matter what the other patrons thought of me. When Bill Murray raised his glass of Hibiki 17, Suntory’s Hibiki and Yamazaki lines were not widely distributed in the U.S. or Europe, and Western drinkers who knew them often considered them a novelty, or worse, a careful impersonation of the “real” Scottish malts. What I tasted could not be dismissed as a novelty. I knew that the people at Suntory who made this whisky had treated it as a work of art.

I loved it so much that I wondered what else was out there. There was little information in English: a single English-language book, Ulf Buxrud’s hard-to-find Japanese Whisky: Facts, Figures and Taste, which cost too much to order. Instead, I found a community of blogging gaijin who took Japanese spirits as seriously as the distillers did, sharing information, reviews, and whatever information they could find. Some of them lived in Japan. Others visited frequently and had Japanese connections who could translate details and source bottles. Clint A. of Whiskies R Us, Chris Bunting and Stefan Van Eycken at Nonjatta, Michio Hayashi at Japan Whisky Reviews. And Brian Love, aka Dramtastic, who ran the Japanese Whisky Review. They blogged about the domestic drams that you could only buy in Japan. They blogged about obscure drams from the decommissioned Kawasaki grain distillery; about something called owners casks and other limited bottlings made for Japanese department stores; and about what remained from the mothballed Karuizawa distillery, now one of the most fetishized whiskies in the world. They were my education.

At home, I searched for whiskies online and in bars and liquor stores and soon discovered my favorites: I preferred the smoky, rich coal-fired Yoichi to the woody, spicy Yamazaki. I liked the fruity depth of Hibiki a lot, but had an irrational prejudice against blended whisky, so I didn’t buy any bottles of Hibiki when they cost a mere $70. And I preferred the crisp, herbaceous forest flavors of 12-year-old Hakushu to them all; I still do. Even after I became moderately educated and increasingly opinionated, I kept buying $30 bottles of my beloved Elijah Craig 12-year instead of Yoichi or Hibiki. That’s the thing: The bloggers couldn’t teach me that the years when I discovered Japanese whisky turned out to be their best years, and that I needed to take advantage of my timing. They didn’t know. Nobody outside the whisky companies did, and nothing about their posts suggested that this world of abundant, affordable Japanese whiskies would come to an end around 2014.

The fan groups and bloggers praised Yamazaki and Karuizawa malts, driving worldwide interest and prices. By the time the influential Jim Murray’s Whisky Bible named the Yamazaki Single Malt Sherry Cask “World Whisky of the Year” in 2015 and San Francisco World Spirits Competition named Yamazaki 18 their 2015 Best in Class under the category “Other Whiskey,” U.S. and U.K. stores couldn’t keep Japanese whisky in stock. The student had overtaken the master. The $100 bottles of Yamazaki 18 no longer appeared on suburban BevMo shelves, and Hibiki 12 no longer cost $70. Everyone was asking stores for sherry cask, sherry cask, do you have the sherry cask? No, they did not. If you wanted a taste of Miyagikyo 12 in America, it would run you $30 to $50 a glass. The year 2015 was the first time Jim Murray named a Japanese malt the world’s best and the first time in the Whisky Bible’s 12-year history that no Scottish malt made the top five. Every drinker and their grandpa knew Johnnie Walker and Cutty Sark. Now they knew Suntory, too.

Kickstart your weekend reading by getting the week’s best Longreads delivered to your inbox every Friday afternoon.

Sign up

In Japan, television fanned the flames further; a 2014 TV drama called Massan, based on the life of Nikka founder Masataka Taketsuru and his industrious Scottish wife Rita Cowan, helped the Japanese take renewed notice of their own products. Simultaneously, Suntory ran an aggressive ad domestic campaign to encourage younger Japanese to drink cheap highballs — whisky mixed with soda — fueling sales and depleting stock even more.

The buzz caught Suntory and Nikka off guard. After decades of patiently turning out top-notch single malts for a relatively indifferent domestic market, Nikka announced that their aged stock had run low, not just at retailers but inside their facilities. Unable to meet worldwide demand, they did what drinkers found unthinkable: They overhauled their lineup in 2015, replacing beloved aged whiskies with less expensive bottles of “no age statement” or “NAS” whiskies that blended young and old stock. Instead of Miyagikyo aged in barrels for 12 years, Nikka gave us plain Miyagikyo. Instead of Yoichi 10, 12, 15, and 20, there was straight-up Yoichi. Suntory had already added NAS versions of its age-statement Hibiki and Hakushu to conserve shrinking old stock and then went even further, banning company executives from drinking the older single malts to save product for customers. Yamazaki 12 still landed on American shelves, but in smaller quantities that sold out quickly, and Japanese buyers saw them less frequently back home.

Longtime fans greeted Suntory’s answer to the masses, called Toki, with skepticism and hostility. (In the words of one non-word-mincing Reddit poster: “Toki sucks. It’s fucking terrible.”) Time in wood gives whisky complexity. That’s how whisky works, but distillers didn’t have enough old whisky anymore, and they seemed to be rationing what remained in order to blend their core lines while they continued aging what they hoped to bottle again. They were victims of their own success, and they needed time to catch up. Nikka’s official press release put it this way: “With the current depletion, Yoichi and Miyagikyo malt whiskies, which are the base of most of our products, will be exhausted in the future and we will be unable to continue the business.”

On the open market, the news created a frenzy that fueled the resale business. Japanese citizens who previously bought few Nikka malts scavenged whatever bottles they could. Chinese investors flew to Japan to gather stock to mark up. Stores in Tokyo inflated prices to gouge tourists, selling $873 bottles of Hakushu 18 that retailed for $300 in Oregon. Secondhand liquor stores collected and resold unopened bottles, many of which came from the elderly or deceased, who had received them as omiyage gifts but didn’t drink whisky. Auction sites flourished. “We call this the ‘terminal aunt’ syndrome,” Van Eycken wrote, “you know, the aunt you never visit until she’s terminally ill.”

The boom times were over.

After the boom, foreign whisky fans took to the web to post about Japan’s shifting stock. Obsessive types like me — what the Japanese call ‘otaku — shared updates about which bottles they found where and which stores were picked clean. “The Japanese whiskys here are in short supply still, short of the cheap stuff,” said one visitor in Fukuoka. Another foreigner proclaimed “the glory days of $100 ‘zawa’s and easy to find single cask Hanyu’s are over.” Gaijin enthusiasts would search cities in their free time while in Japan on business; others drove out into inaka, the sticks, systematically searching for rare or underpriced bottles at mom-and-pop shops. “On the bright side,” the same commenter reported in 2016, “I went into the boonies and found a small liquor distributor who had 2 Yoichi 10’s and a bunch of dusties (Nikka Super 15, Suntory Royal 15, The Blend of Nikka 17 Maltbase, Once Upon a Time) all pretty cheap, between $18-$35 each. I know some of those dusties are not much more than mixer material, but it’s nice to have a piece of history.” Others found these searches pointless. “Well as a point of fact there is no point for any foreigner to come to Japan in search of Japanese whisky,” Dramtastic wrote in 2015. “You will in many countries almost certainly find a better offering at home and if not, one of the online retailers.” He titled his post “Buying Japanese Whisky In Japan — Nothing But Scorched Earth!”

It was right before the earth got scorched that I obliviously arrived in Japan.

* * *

When I finally got the money to travel overseas, there was only one real choice: Japan. For three weeks, I roamed Tokyo and Kyoto alone, where I shopped for my beloved canned sanma fish and green tea soy milk in grocery stores. I bought jazz CDs and Murakami books in Japanese I couldn’t read. I wrote about capsule hotels and old jazz bars. I photographed my ramen and eel dinners, and I photographed bottles of whisky on store shelves.

It wasn’t that I didn’t want them. I wanted them all: Yoichi 15, Hibiki 21, Miyagikyo 12. But as a traveler, practical considerations prevailed. I didn’t have much money. My luggage already held too much stuff, and anyway, the products would be there next time. I bought a few bottles of common whisky to drink during my trip and went about my business.

I unwittingly found the largest selection of Japanese whisky on my final night in Japan.

I was staying near the busy Ikebukuro train station and went out seeking curry. I wandered around in the cold, shivering and sad about leaving. As I passed ramen shops and busy izakayas, I spotted a cluttered electronics store. Music blared. The interior had a cramped, carnival atmosphere. Blinding white light spilled out the front door. Red lettering on the building’s reflective side said Bic Camera.

I didn’t know it then, but the Bic Camera chain had nearly 40 stores nationwide. The stores often stand seven or eight stories in busy areas near train stations where pedestrians abound. In 2008, the company was valued at $940 million, and its founder, Ryuji Arai, was the 31st richest person in Japan. When Arai opened his original Tokyo camera store in 1978, he sold $3.50 worth of merchandise the first day. Today, Bic Camera is an all-purpose mega-store that sells seemingly everything but cars and fresh produce.

Before the boom, Bic sold highly limited editions of whisky made exclusively for Bic, including an Ichiro 22-year and a Suntory blend. The stock is designed to compete with liquor stores that carry similar selections, though many Japanese shoppers come for the imported scotch and American bourbon. That night I couldn’t tell any of that. I couldn’t even tell if this was an upscale department store or a Japanese version of Walmart. In America, hip stories follow the “less is more” principle, with sparse displays that suggest they’re also selling negative space and apathy. Bic crammed everything in.

I rode the escalator up for no other reason than to see what was there. Cell phones, cameras, TVs — the escalator provided a nice view of each floor. When I spotted booze on 4F, I jumped off. They had an entire corner devoted to liquor and a wall displaying Japanese whisky. They had all the good ones I’d read about online but hadn’t been able to find and others I didn’t know. My luggage already contained so many CDs, clothes, and souvenirs that I’d have to mail some things home, but I grabbed two bottles anyway, I no longer remember which kind. I only remember gripping their cold glass necks like they were the last bottles on earth, desperate to bring just a bit more home, and I held them tightly as I wandered the aisles, studying the unreadable labels of aged whiskies and marveling at the business strategy of this mysterious store as I preemptively mourned my return to the States.

A clerk in a black vest approached me and said something politely that I couldn’t understand. With a smile, the man said something else and bowed, sorry, very sorry. He pointed to his watch. The store was closing, maybe it already had. He stood and stared. I looked at him and nodded. He stood nodding back. In that overwhelming corner, with indecipherable announcements blaring overhead, I considered my options and returned the bottles to the shelf, offering my apologies. Then I rode back down to the frigid street. The dark night felt darker away from Bic’s fluorescence, as did the winter air.

The high-end whiskies in a locked case. Tokyo grocery store 2014. Photo by Aaron Gilbreath

Like a good tourist — and like a dumbass — I photographed everything on that first trip, from tiny cars to bowls of udon to Japanese whisky displays. When I look at the photos of those rare bottles now, I see the last Tasmanian tiger slipping into the woods. The next season, it went extinct, and all I’d done was raise my camera at it. I had unwittingly visited the world’s greatest Japanese whisky city and I had nothing to show for it.

* * *

The trip ended. The regret lived on.

Partly, it was fed by money, or my lack thereof: Because I like having a few different styles of whisky at home, I wanted a range of Japanese styles, but I couldn’t afford $100 bottles of anything, which meant I’d never get to taste many of these whiskies.

Part of it was nostalgia: I wanted to keep the memory of my time in Japan alive, to prolong the trip, by keeping its bottles on display at home.

Mostly, it’s driven by something much more ethereal. When people ask why I like whisky, I tell them it’s the taste and smell. Scotch strikes a chord in me in a way that wine, bourbon, and cocktails do not. I spare them the more confusing truth, which even I struggle to articulate. Part of scotch’s appeal comes from scarcity and craftsmanship. Its spare ingredients include only barley, spring water, wood, and the chemical reactions that occur between them. And time: Aged spirits are old. For half of my 20s and all of my 30s — the time I was busting my ass after college, trying to build a career and learn to write well enough to tell a story like this — 18-year old Yamazaki whisky lay inside a barrel in a warehouse outside Osaka. That liquid and I lived our lives in parallel, steadily maturing, accruing character, until our paths finally crossed at a bar in Oregon.

That liquid and I lived our lives in parallel, steadily maturing, accruing character, until our paths finally crossed at a bar in Oregon.

But it’s more than age. Something magical happens in those barrels, where liquid interacts with wood in the dark, damp warehouses where barrels rest for decades. Aged whisky is a rare example of celebrating life moving at a slow, geological pace that is no longer the norm in our instant world. You can’t speed up this process, and that makes the liquid precious. When you’ve waited 12 years for a whisky to come out the cask, or 20 years — through wars and presidencies, political upheavals and ecological crises — that’s longer than many people have been alive. And in a sense, the whisky itself is alive. That potent life force is preserved in that bottle. The drops are by nature limited, measured in ounces and milliliters, and that limitation puts another value on it. When the cap comes off your 750-milliliter bottle, you count: sip, sip, uh oh, 600 mils left, then 400, then a level low enough that you reserve the bottle for special occasions.

The limited availability of certain whiskies adds another layer of scarcity value; when distilleries close, their whisky becomes irreplaceable. No more of those Hanyus or Karuizawas will ever get made. No more versions of the early 1990s Hibiki, since Suntory changed the formula. For distilleries that still operate, their whisky is irreplaceable, too. The exact combination of wood, temperature, and age will never produce the same flavor twice. Even when made according to a formula, whisky is a distinct expression of time and place. The weather, the blender, the barley, the proximity to the sea, and of course, the barrels — sherry, port, or bourbon? — all impart a particular flavor along with the way blenders mix them. For Yamazaki 18, 80 percent of the liquid gets aged in sherry casks, the remaining 20 percent in American oak and mizunara. That deliberation and precision come from human expertise that takes a lifetime to acquire, and expertise, like the whisky it produces, is singular and therefore valuable.

When you sip whisky, you don’t have to think about of any of this to enjoy it. You don’t even have to name the flavors you taste. You can just silently appreciate it; it doesn’t have to be any more complicated than that.

For me, Japanese whisky became more complicated, because I also wanted it to give me something more than it could: a connection to a trip and a time that had passed.

In Japan, everything looked a certain way. The way stores displayed bottles. The way restaurants displayed food. The way businesses signs hung outside — Matsuya, Shinanoya, CoCo Curry House — and the way all of those images and colors and geometries combined in a raucous clutter of wires and Hiragana and Katakana to create urban Japan’s distinctive look. When I returned home, I kept picturing those streets. They appeared in dreams and projected themselves on shower curtain as I washed in the morning. To stave off my hunger, I frequently ate at local Japanese restaurants, but even the most exacting decorations or grilled yakitori skewers couldn’t fully give me what I wanted. So I fantasized about creating it myself, and then I did: my best replica of an underground Tokyo bar, in the corner of my basement, the bottles lined up just so.

When my wife, Rebekah, and I took our honeymoon to Japan in 2016, I hoped to make up for past errors. Instead, I found the scorched earth. Japanese liquor stores and grocers sold few of the rare bottles they did just two years earlier. The fancy department stores had no Karuizawa or Hanyu. And the aged whiskies I did find had price tags too big to afford. I bought none of them on that trip either. For the cost of a $130 Yoichi 12, I could buy three great bottles of regular hooch at home. After we returned, I kept scheming ways to return to Japan for just a few days. Since I couldn’t, I satisfied myself with my display of empty whisky, sake, and Japanese beer bottles, and I kept scheming ways to get more domestic booze. A friend brought me a bottle of Kakubin while visiting her family in Tokyo. I asked a few friends in Japan to mail me bottles, even though regulations prohibit Japanese citizens from doing that. (They said no.)

There was only one way to get more whisky, and I couldn’t afford the ticket.

Then in January an email about a discount flight to Tokyo landed in my inbox. Flights were crazy cheap. I had to go.

When I proposed this to Rebekah, she said, “Seriously?” She lay in bed, staring at me like I’d asked if she’d hop on a plane to Amsterdam in 10 minutes without packing. “Just hear me out,” I said, and outlined my impractical business plan for recouping expenses by throwing paid, tip-only whisky parties for booze no one could find anywhere else in Portland, where we live. “Think about it as a stock mission,” I said. “I’m buying inventory.” She stared at me unblinking. It’s Japan, I said. It’s right there, next to Oregon after all that water. We were basically neighbors! The quality of the whisky I’d buy would be lower than all the now-collectible bottles I passed up on my first trip, but at least I would do it right.

It’s Japan, I said. It’s right there, next to Oregon after all that water.

I pictured myself flying to Tokyo in spring. The train from Narita Airport to Bic Camera in Kashiwa would wobble along the tracks, its brakes squeaking as it stopped at countless suburban platforms, with their walls of apartments and scent of fried panko. A 6 o’clock, the setting sun would cast the sides of buildings the color of summer peaches, and what little I could see of the sky would glow a blinding radish yellow. My knees would hurt from sitting on that plane for 11 hours, so I’d stand by the train door to stretch them the way I had during my first Tokyo trip, watching the 7-Eleven signs and giant bike racks pass, and posing triumphantly over time and my own pigheadedness. I’d buy as many bottles of domestic Japanese whisky as my one piece of rolling luggage would hold without exceeding the airline’s 50-pound limit. In a life marked by stupid things, this would be one of the stupidest. I’d feel endlessly grateful. The bottles would keep me connected me to Japan, to that trip, date-stamped by its ephemerality, just like the numbers on the bottles of aged whisky: 10, 12, 15, 20 years.

I never bought the plane ticket. There was little there to buy anyway. In 2018, Suntory announced that it would severely limit the availability of Hibiki 17 and Hakushu 12 in most markets. Soon after, Kirin announced it would discontinue its beloved, inexpensive, domestic Fuki-Gotemba 50 blend. Stock had simply run out. I’d bought a few good bottles for low prices before the boom and they stood in our basement bar, where we drank them, not hoarded them for future resale. Drinking is what whisky is for. The bottles stood as reminders that I had done a few things right. And maybe we should think less about what we missed and more about what is yet to come. In 2013 and 2014, Suntory expanded its distilling operations to increase production. It, Nikka, Kirin, and many smaller companies have laid down a lot of whisky, and when all that whisky has sufficiently aged there will be a lot of 10-to-15-year-old whiskies on the market — maybe as early as 2020 or 2021. “I always tell people not to worry about not being able to drink certain older whiskies that are no longer available,” Osaka bar owner Teruhiko Yamamoto told writer Brian Ashcraft. “Scotch whisky has a long tradition, but right now it feels like Japanese whisky is entering a brand new chapter. We’re seeing whisky history right before our eyes.”