#quoting roland barthes from ‘the pleasure of the text’

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Not to go full Kristevan semiotics but intentionally showing the flatline on Daniel’s laptop recording… cut in between the peaks and valleys, red…. one day you’re at a traffic light… green light… horns honking, you don’t move… horns honking, you don’t move… it’s about the boundary of start/stop, it’s about the repetition, it’s about intermittence… an empty space between spikes… one sentence clause, then another, up against each other, up-down, repeating, constructing boundary out of juxtaposition… red, green… it’s about what happens when the symbolic boundaries get broken… and what is a greater transgression of signified boundaries than a corpse. Death in the flesh. The realized abject. Horns honking, you don’t move. He never says, you’re dead. But we know. Green means go. You don’t go. The symbol has no meaning in the face of death. Boundaries broken. Meanings broken. All that careful construction simply crumbles.

Intermittence as a language of boundaries and therefore a language of inferred meaning but also a language of horror and yet, still, a language of the erotic. “It is intermittence, as psychoanalysis has so rightly stated, which is erotic; the intermittence of skin flashing between two articles of clothing (trousers and sweater), between two edges (the open-necked shirt, the glove and the sleeve); it is this flash which seduces, or rather: the staging of an appearance-as-disappearance.” The erotic as a sort of liminal space, the flash between boundaries. The abject, and horror, as things that transgress those boundaries. The sublime, ashamed jouissance where these things overlap. The thrill.

One sentence clause, then another. Boundary by juxtaposition. Two symbols standing next to each other. Peaks and valleys. You, me. Me, you. The boundaries give meaning. I construct myself against you. But what happens when the boundaries between you and me no longer exist? What happens when I am you and you are me and our blood is one body?

Horror. A thrill. Death. Erotic where we overlap. No subjects remain. There is only an undefinable not-thing. An abject. This is monstrousness.

#quoting roland barthes from ‘the pleasure of the text’#and more loosely drawing on both ‘the powers of horror’ and a lot of kristeva’s other writings on semiotics#daniel molloy#armand#iwtv tv#iwtv#devil’s minion#armandaniel#also a general show thesis! 2 me#including when applied to loustat

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

The title of a recent exhibition at Musée des beaux-arts in the Swiss town of Le Locle (MBAL), The Pleasure of Text, is borrowed from Roland Barthes’s famous 1973 essay. A quote from that text stands out in the center of the room displaying paintings from the MBAL collection, depicting women engrossed in the act of reading: “The pleasure of the text is that moment when my body will follow its own ideas—for my body has different ideas than me.” This physical dimension of reading pleasure is exemplified in an installation by the Swiss duo Andres Lutz and Anders Guggisberg, who have created a new space in the museum’s former library, blending sculpture and automatic painting. The installation features a selection of their Bibliothèque Imaginaire (1999–2020), consisting of hundreds of wooden books that viewers are encouraged to explore. While the volumes cannot be read, the tactile experience of reading remains, and the text within them becomes a product of the viewer’s imagination.

0 notes

Text

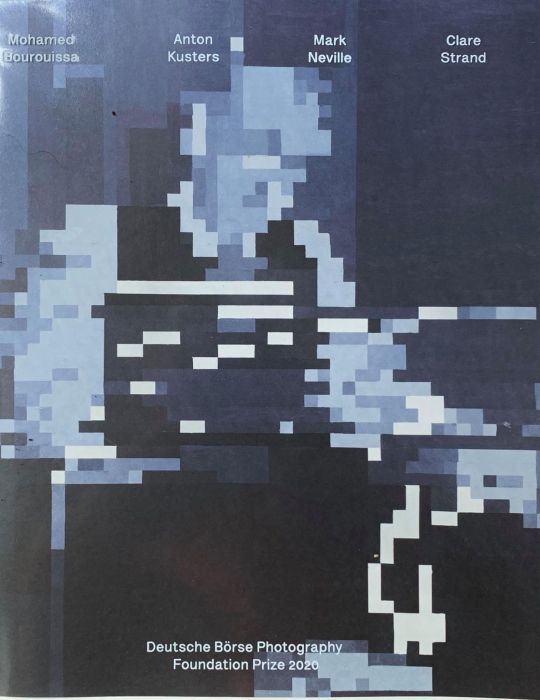

Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation prize Catalogue with text by Orit Gat.

The award will now be announced (virtually) on Sept 14th. For further info on how to join the webcast please consult The Photographers Gallery Website.

Image = Information

Orit Gat

1 A beginning

In Paris, an artist painting in a studio that used to be part of a monastery. She goes out and gets the largest drawing papers she can find. Surrounded by paint pots and brushes, it’s an image that belongs in a tradition of artists painting away in Parisian garrets, only this is not that story. What Clare Strand was painting in her Paris studio during a three-month residency at the Centre Photographique d'Ile-de-France in 2017 was a translation of pre-existing photographs that were ‘read’ to her over the phone by her husband in the UK. From across the English Channel, he would give her directions that would encode an image of his choosing, and she would paint it.

2 Transmission

Strand and her husband were following an existing model. The method they were using to transmit information was described in George H. Eckhardt’s ‘Electronic Television’, from 1936, in which he outlined how a photograph can be transmitted via code over telegraph. In this system, the original image is divided into a grid, with every square being given a value from 1 to 10. 1 is white, 2 has a tinge of grey, 3 is greyer, 4 darker and so on until 10, which is black. The initial source images from which Strand’s husband chose the images he would transmit to her were 10-by-8 inches, which they divided into a grid of forty-nine squares across and sixty down, each about 5 square millimetres. If it’s boring to read, imagine the couple’s phone conversations: he would call and say 24-2; 25-4; 26-5; and so on. Through conversation, with Strand following her husband’s direction, the language would form a representation of the original image. Like a human fax machine.

3 The result

Is a series of ten black-and-white paintings in acrylic on paper. The history of art brings forth associations and relations, from the development of the grid as a foundation for perspective in the Renaissance, to the nineteenth-century illusionism achieved through Pointillism. There are Gerhard Richter’s black-and-white paintings, László Moholy-Nagy’s telephone paintings, Agnes Martin’s feather-light grids. But the connection to the history of art crumbles in front of the actual framed paintings. They’re human, Strand says, as she reasserts that she is not a painter. They’re messy, imperfect. There are hairs that stuck to the paper, dust congealed into the paint. However, in installation shots of the whole series, they look like another kind of work. Photographed, the paintings seem faultless: the black, white and grey hues reminiscent of aestheticized black-and-white photography; the paintings look clean, their edges not frayed, the small mistakes blend into the frame. It’s like they have two lives, as object and as image. When I ask Strand which one matters more, she answers, ‘I don’t know. What I find ironic is that, as much I try to push “photography” into different mediums, I can never escape the camera and how it operates as a tool of representation. With each press or catalogue reproduction, the paintings are represented as photographs, which is somewhat at odds with the concept of the work – photography transposing into painting only then to be represented by photography!’

4 Utility

To talk about the history of art and about installation shots is to ignore how the objecthood of the paintings depends on their creation. This series, titled The Discrete Channel with Noise, is at once the result of and the documentation of communication and its possible failures. Looking at the paintings, I want to say they look pixelated, but that would make them more photo than painting, more final product than process.

5 The first man who saw the first photograph

The relationship between painting and photography always makes me think of Roland Barthes writing in his essay on photography, Camera Lucida, that ‘The first man who saw the first photograph (if we except Niépce, who made it) must have thought it was a painting: same framing, same perspective. Photography has been, and is still, tormented by the ghost of Painting.’ Later in the book, he writes about photography’s relationship to reality, or to the document: ‘No writing can give me this certainty. It is the misfortune (but also perhaps the voluptuous pleasure) of language not to be able to authenticate itself.’ The photo as confirmation of fact. That fact, that reality, is communicated over phone lines in The Discrete Channel with Noise. When we look at a photograph, what we’re looking for, according to Barthes, is knowledge that a thing, an event, happened. He writes about Polish soldiers in a 1915 photo by André Kertész: ‘that they were there; what I see is not a memory, an imagination, a reconstitution, a piece of Maya, such as art lavishes upon us, but reality in a past state: at once the past and the real.’ What we see, in The Discrete Channel with Noise, is a story about reality rather than proof thereof.

6 Whizzing through the air

When I meet Strand, she hands me an assortment of notes. She’s hesitant about it for a minute, as if giving me homework rather than help. Or as if she expects communication can fail, and thinks a list of references may offer a way out of an impasse. The history of Morse code; pigeon post between Paris and England c. 1870–71; Eckhardt; Cybernetics founder Norbert Weiner and American mathematician Claude Shannon’s information theory, which gave The Discrete Channel with Noise its title: Strand’s research does not explain as much as expand the work. And then in the notes is a quote from the 1973 movie Charlie and the Chocolate Factory based on Roald Dahl’s writing, recreating Eckhardt’s transmission of images over radio. Here the character Mike Teavee, the winner of the fourth golden ticket, who loves this technology, explains: “You photograph something then the photograph is split up in to millions of tiny pieces and they go whizzing through the air, then down to your TV set when they are all put together in the right order”

Mike Teavee, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Roald Dahl (1971).

That it is possible to share an image, and the labyrinthine process of it whizzing through the air is in line with Dahl’s 1971 book, in which the candy factory includes an impenetrable room-sized machine that, when operated, makes a lot of noise, takes a lot of time, and then produces a single bit of chewing gum. Unimpressive until someone chews it and realizes it is as nourishing as a three-course dinner: tomato soup, roast beef with baked potatoes, blueberry pie and ice cream for dessert.

Proof: the overcomplicated can sometimes be amazing.

A lesson: also worth exploring.

7 Thirty-six images on a journey

The ten images in The Discrete Channel with Noise were chosen from a collection of thirty-six images Strand has compiled for a previous work, The Entropy Pendulum (2015), in which each of these photographs, which were taken from a tabloid newspaper’s archive, was eroded by the weight of a pendulum over the course of one day in an exhibition, then framed. Strand rephotographed the physical photos from the archive, creating a digital output that becomes a dataset ready for reuse. The subject of those images related to what Strand refers to as the subject of her work in general – magic, illusion, the paranormal, communication, transmission, the way people thought communication technologies were magical when they were first introduced, the way Alexander Graham Bell called the telephone a way to ‘talk with electricity’. How to read the transformation of these images through the process in The Discrete Channel with Noise These images are on a journey of losing and gaining information. The project is a metaphor, if not a realization, for what images do anyway: in flux, they move and shift in meaning.

8 Shifting in meaning

Why pay attention to shifts? Because shifts in context can mean that information is lost, or misused. An art historian friend of mine regularly points out that Alexander Nix, the founder and CEO of Cambridge Analytica, studied art history in university. Art matters, images matter, she wants to say. All channels of misinformation need to be decoded. Is there a present and a real, like Barthes thought there was in an only slightly less technological time than the one we occupy, today? Or is the subject of study now how realities are fractured across channels of communication?

9 An entire history of communication

The diagram used to explain Eckhardt’s ‘Electronic Television’ has a man sitting at a table in front of a large black-and-white image divided into a grid of a woman with short, curly hair who looks a bit like an early Hollywood film star. His sleeves are rolled up, his back a bit hunched, he is clearly concentrating. He holds a long pointer stick and taps information onto a device resting on the desk he is sitting at. The cable running from that device spirals into a growing network of telephone poles that reach a window, and from that window to a box on the wall, and straight from the box to a set of headphones that another man wearing a blazer (or is it a lab coat?) standing in front of a large grid, only partially completed with the recognisable top of the short-haired woman’s head. He holds a paint brush at the same spot the other man’s pointer is. Behind him on a table are 10 boxes of paint numbered from 1 (white) to 10 (black) and some paint brushes. The caption reads, ‘Fig. 26. A Simple Method for Sending Pictures by Wire or Radio.’

Visually, it matters that the example is always a woman and the transmitters and receivers are always men. The message is that even in new technologies, even in a new world, some old signals remain. That is what Eckhardt’s diagram exemplifies. An entire history of communication reinforces the idea of who gets to speak across these lines. It is therefore fitting that The Discrete Channel of Noise is structured and executed by a female artist.

10 A piece of Maya

When Barthes writes that ‘no writing can give me this certainty’, he is asserting photography’s relationship to what he calls ‘the real’. But as a writer, he must have known that it is the rest of the above-cited list – ‘a memory, an imagination, a reconstitution, a piece of Maya’ – that is one of the potentials of art: to reconstitute is a way of reimagining the world. After Cambridge Analytica, or in line with Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, I want to argue that the redefinition or the exploration of that real is the contemporary condition. We come to things with suspicion, some of which is about recognising the failures of the systems around us. But we also come to them with a sense of possibility, a remnant of the Maya or the three-course meal chewing gum: the idea that the world is a story, and it can be shared.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Call Me by Your Name: Is it better to speak or to die?

Original text by Hristiana Hinova

Illustration: elysieeh

A ten-minute ovation follows the film’s screening at Sundance. Director Luca Guadagnino opens Twitter and reads about people jumping and dancing on the streets after having seen his film. It is one of those rarely made films which produce an incredible sense of euphoria that lasts for months to come. Last year that place was held by American Honey. Both films are a spectacle for the senses—gentle monsters whose visuals are electrifying and the feeling they leave behind is truly truer than the truth we witness every day. Call Me by Your Name is a film about Love, the kind that turns life into an event, and emitting such an emotional charge life itself becomes an event.

The 24-year-old American student Oliver is completing an internship at professor Perlman’s (his Jewish-American archeology professor with French and Italian roots; played by Michael Schulber, whose Oscar nomination hopefully becomes a fact soon) villa in the north of Italy. The atmosphere of the house is idyllic. The Perlmans are a dream family—highly educated, beautiful people who speak freely about philosophy, history and linguistics and kiss and hug whenever they pass each other on the corridors of the house. Elio, the professor’s son (an impressive debut starring Timothée Chalamet) is a 17-year-old spiritual and talented boy; he spends his days studying classical music, reading books, cycling and going out to bars in the evenings.

Call Me by Your Name starts straight off with the conflicting event: Oliver's arrival. Oliver is an imposingly handsome and confident guy; the ancient Greeks have a word for it—kalokagathia: a Platonic ideal consisting of the harmonious combination of bodily, moral and spiritual virtues. During the first few minutes of the film, he is the object of adoration by every one of the characters (apart from the Perlmans, there are also minor characters, the most prominent of who is Elio's girlfriend, the French Marcia, played by Esther Garrel).

What happens next is magic: Elio's love for Oliver goes through several recognisable stages, which are translated on screen with a masterful ease of the camera: it glides among the characters effortlessly, like a puff of wind. (Behind the camera was Thai Sayombhu Mukdeeprom, who has also worked with Apichatpong Weerasethakul on the dreamy, mysterious and visually perfect Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, awarded with the Golden Palm at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival.) Director Luca Guadagnino had the following to say in this regard: "We had a Buddhist behind the lens. And you can see it in every frame."

In order to convey my thoughts in a more organised way, I will divide the text into 5 parts. These 5 parts correspond to the 5 states of mind the main character Elio goes through during the 3 weeks in which the love between him and Oliver develops. This is an attempt to decode the power of the film, which I believe is rooted in the absolutely brilliant journey through the universal emotions of love. Call Me by Your Name wonderfully visualises the inner world of a person in love and the most elated, most intense states of mind that his enchanted soul can go through. I will include a few quotes from Roland Barthes’ A Lover's Discourse: Fragments which to me is the most poetic and refined translation of the love emotion into words. Not to show off but to present you the pleasure that is Barthes’ work. This film is the same kind of translation, slightly more accessible—but no less subtle and emotional.

For at least a year I hadn’t seen a love story that could move me so much with its genuineness. One of the best qualities of the film is its script: it lacks an antagonist and a conflict. According to textbooks, this is not how you write a script. It is risky—some might say even wrong. Since it doesn’t have the stereotypical Romeo and Julietesque problem where an external force interferes with the love of the two, nor is there a serious hesitation in some of the characters. Nobody dies. Nobody is less fortunate than the other, no one is whiter or darker than the other. We witness two people fall in love and thus create paradise, and—trust me—this is one of the most exciting stories to tell.

Desire This is the third and final instalment in Luca Guadagnino's thematic "Desire Trilogy”. The previous two being I Am Love (2009) and A Bigger Splash (2015). According to the director, the first one is a tragedy, the second—a farce, and the third one—a dream. While in both previous films there is some tragicomic element which works as a warning following the desire, Call Me by Your Name does not have one. Here, loving does not lead to anything bad. The pain after the loss is not harmful.

The film starts off with a half-naked Elio who must quickly vacate his room for it is to be occupied by the guest Oliver. Elio’s house is a spacious and cozy one (with doors open all the time and delicious meals being prepared in the kitchen); whichever room you enter, it is full with books you can read under the huge windows that let in the generous afternoon sun. Everyday life is a wasteful delight. The viewer sees this and sinks into his seat light-headed, dreaming of a similar life. Call Me by Your Name manages to strike a chord in us that is rarely touched; the melancholy for a paradise not yet lived, one ripen by the caress of the graceful nature, kissed by the sky, hidden from the dusty, sore city eye.

The sexual desire is not stated immediately. The scene in which Elio and Oliver meet for the first time, for example, is filmed in a rather unconventional way for this type of narrative. Typically, love at first sight is alluded at by showing the reaction of the main character, the one who is to fall in love first, in a medium shot or a close-up. Here, however, the scene is as follows: through a half-open door Elio and Oliver shake hands. Elio is showing us his back. On Oliver’s face we can read a polite smile tired from the long ride. BAM! Nothing special. No escalating music, nor an entertaining frame. Simple.

There is a reason for this. The story is based on a novel (written by André Aciman and adapted by James Avery). The novel is told in the first person, from Elio’s perspective. Therefore, by default, this is a story that comes from the inner world of the main character, ie. we would expect less eventful and more reflective storytelling. The director wanted to keep it as is in the book and translate it on screen. Hence, Elio’s ’slow’ falling in love (expressed at a later stage in the film with the regretful words: "We wasted so much time"). The ‘slow’ in question is really nothing more than a developing character, a man who grows before the eyes of the viewer, a man who loves and is loved for the first time.

Elio’s desire for Oliver is shown with his long glances directed at Oliver from the distance: Elio watches from his widow how the object of his desire walks, goes for a bike ride, dances, hugs and kisses a woman. Elio experiences a moment of frustration: on the one hand, he knows what is going on inside him, but his body doesn’t know how to react. The boy seems to be overcome by a fever. This is why when Oliver touches him for the first time to massage his shoulder, Elio pulls himself to the side confused. Desire causes ambivalence: often, instead of pulling us towards the object of our desire, it pushes us away from it; and this reaction is a defence mechanism: “Do not enter the beast’s mouth, because there is no way out.”

Elio falls in love with Oliver also through the eyes of others. He knows that this is a man who his father, the professor, likes and respects. This is also a body that others talk about; watching him play volleyball, the girls whisper to one another that he is “more handsome than the guy from last year.” This is what Roland Barthes has to say on the subject:

The body which will be loved is in advance selected and manipulated by the lens, subjected to a kind of zoom effect which magnifies it, brings it closer, and leads the subject to press his nose to the glass: is it not the scintillating object which a skilful hand causes to shimmer before me and will hypnotise me, capture me? This “affective contagion,” this induction, proceeds from others, from the language, from books, from friends: no love is original. (Mass culture is a machine for showing desire: here is what must interest you, it says, as if it guessed that men are incapable of finding what to desire by themselves.) The difficulty of the amorous project is in this: “Just show me whom to desire, but then get out of the way!”

Anxiety When we cannot own something, we become obsessed with a fragment of it. After Elio becomes aware that he is in love with Oliver, he starts missing him. Oliver grabs his bike and disappears for a whole day. Elio is alone in the house. He goes back to his room and examines the beast’s dwelling. This is his very room, but changed forever—soaked in the presence of the one who is absent now. There are one or two marvellous shots where the camera focuses on Oliver’s swimming shorts hanging from the faucets in the bathroom. Elio grabs a pair of them, lies down on his bed and thrusts his head inside. This is the only thing he can possess. Just a fragment, and it isn’t even from Oliver’s real body. It upsets and scares him, but at the same time brings him incomparable pleasure. When else is pleasure confusing? Love is maddening: it tears you away from your own self and hands you over into the possession of something abstract like a Thought, Scent or Idea. Elio is lost in the labyrinth of the Other. And for the first time we can hear Sufjan Stevens’ amazing music in a moment of culminating anxiety. It is an exceptional scene: Elio’s face is blurred and it seems as though a film reel is passing through it. Elio is not a part of his own life—he is a projection of the collective, centuries old face of the One in Love: the one who has fallen victim to a spell.

The following scene: Elio is together with his parents and the three of them are sitting on a couch. He is resting his head on his mother’s lap. She is reading to them the story of a princess and a knight from some French romance; the knight is so much in love with the princess that he doesn’t know what to do about it. The horror that he experiences in regard to his feelings escalates in the lines: “Is it better to speak or to die?” This startles Elio, who realises that his choice is indeed ultimate. The scene represents a key dramatic situation. The one in love is faced with a moat: on the one side stands he himself, like a boy, bent with a frightened look over the abyss, on the other side stands a tall, noble man. Can he overcome the moat?

Heroism According to Joseph Campbell, in every story with a prominent protagonist there is a moment of initiation, i.e. the moment in which the boy takes on a challenge and thus embarks on a path towards maturity. For Harry Potter, for example, this is his departure to Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. In our Bulgarian folklore, on the other hand, the hero kills the three-headed snake which usually brings him great fame and the love of the greatest beauty.

What does Elio do to become a man?

Elio decides to speak. In spite of all the horror this action brings – putting yourself in a weak position, risking being misunderstood and humiliated, Elio exhibits courage and decides to confess. Courage, because confession is self-assertion and this is one of the manliest things to do: “I am here and this is how I feel. How about you?" As all the readers probably know, telling someone that you love them without knowing how they will respond to your feelings is a hard and painful thing to do. It can cost a lot of nerves, especially if one was brought up in the spirit of high classical values.

And Elio speaks. God, how good this scene is. I may even like it more than the last 10 minutes of the film. The scene is brilliantly conceived and filmed: Elio and Oliver are walking on the opposite sides of a monument commemorating the victims of the First World War. They are talking about history and Oliver is surprised by Elio’s vast knowledge. Then Elio, having gathered up the courage, says that he knows nothing. At least not about the things that matter. “What things that matter?” demands Oliver. “You know what things,” replies Elio after a thoughtful pause. He tells him everything by not telling him anything. Between them lies history – the stone monument, a symbol of suffering and heroism – and inside of them rages an equally important event: the Conversation.

Unity The fourth part of Call Me by Your Name shows the real relationship of the two after love has been established as a fact. It feels the longest. And this is how it is supposed to be, bearing in mind that this is a romantic film that is not specified by the genre restriction of either comedy or drama. The title of the film refers to exactly this part. Call me by your name are the words which Oliver gifts Elio and which actually carry all the charge of their relationship: true merging is when you don't differentiate yourself from the other, being so much in love that you’re sinking into the other. This is the moment of culmination: you are one with your Desire and your Desire is one with you. There is no conflict nor drama. The world is just a prolonged touch. Everything is simple and the pleasure is inexhaustible. A quote from A Lover's Discourse: Fragments:

Definition of the total union: that is “the one and only pleasure” (according to Aristotle), “joy without blemish and without impurity, the perfection of dreams, the limit of all hopes” (Ibn Hazm), “the divine splendor” (Novalis), this is: the inseparable peace. (…)

Dream of total union: everyone says this dream is impossible, and yet it persists. I do not abandon it. "On the Athenian steles, instead of the heroicization of death, scenes of farewell in which one of the spouses takes leave of the other, hand in hand, at the end of a contract which only a third force can break, thus it is mourning which achieves its expression here . . . I am no longer myself without you." It is in represented mourning that we find the proof of my dream; I can believe in it, since it is mortal (the only impossible thing is immortality). SYMPOSIUM: Quotation from the Iliad, Book X.FRANÇOIS WAHL: "Chute.”

Conclusion The fifth and last part, the one when Oliver leaves, has an almost instructive function. The father has the role of a sage, a teacher (figuratively and literally). He is supposed to evaluate the situation and interpret its meaning. He is the one who has studied art and the human nature throughout the centuries, the way in which humanity asserts itself. And yet, he is the man who admits that he has never been so close to the perfection of human relationships as his 17-year-old son has. The father’s revelation is striking: in the absence of love, one wears out. In the absence of courage to love, one withers away. Once again, this brilliant monologue deserves an Oscar nomination.

There are films that are magical. Do not doubt that Call Me by Your Name is one of them. And to put out the swollen pathos, I will tell you that the peach scene has been tested (in real life) both by Luca and by Timothée Chalamet. Seems like one can have fun in the most unexpected places!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

fishnet research

http://www.thistailoredlife.com/blog/2016/2/7/the-alluring-history-of-fishnets

quotes from article

Philosopher Roland Barthes writes in his 1973 essay, The Pleasure of the Text, about the eroticism of the interplay of seen and unseen that fishnets embody. Not to mention the grid afforded by netted clothing like fishnets does a good job at emphasizing curves and musculature on one’s body.

Fishnets continued to be associated with a ‘loose’ type of woman especially as they gained popularity in print-porn and pin-up girls of the 1950s.

Fishnet tights graduated to any netted piece of clothing with, you guessed it, Madonna in the 1980s. This pop goddess and fashion icon was often dressed in fishnets, but she didn't limit herself to just stockings. She also sported fishnet tops, gloves, and body suits.

0 notes

Text

Current-Reads (06/04/2020 - 12/04/2020) 📖🌷

(Disclosure: I don’t know any of the authors (two of them are dead, sadly) nor the publishers from any of the books I’m recommending this week. Three cheers for impartiality, everyone.)

All the blossoms’s out and it’s raging blue skies at the moment. I’ve found some peace in it at times. I really can’t stop thinking about the sacrifices key workers are making, especially those in healthcare, and wishing I could do more. Keep loving the people around you, keep appreciating the springtime blossom, and I hope you’re all keeping safe and well.

So, every Sunday I draw up a list of what I’ve been reading over the week and share them on here, in the hope that maybe some of the suggestions might pique your interest too. I know not everything will be everyone’s cup of tea, and if you think there’s something out there I should read, drop me a line and tell me about it.

I generally gravitate towards a lot of emerging writers or contemporary literature from the 21st century. But as of late I’ve looked at some 19th and 20th century literature, which has been fun to read and write about.

Anyhow, this week I’ve been reading Georges Bataille’s Story of the Eye, Cunt-Ups by Dodie Bellamy, E M Cioran’s The Trouble with Being Born, The New Fuck You: Adventures in Lesbian Reading edited by Eileen Myles & Liz Kotz, and Adam Phillip’s Attention Seeking. It’s been great. So below I’ve got a small-ish breakdown in terms of what they’re all about, what they do. Sometimes I add ‘RECOMMEND’ next to some of the titles, but that’s not to say I don’t recommend all of them, I just love some books more than others. C’est la vie.

***

Okay so, first up:

Georges Bataille, Story of the Eye (RECOMMEND): Bataille spent most of his life being rejected by various writers and thinkers, (the Surrealists, the Existentialists, etc.) He was considered far too extreme, far too transgressive. Look at him now. He’s a Penguin Modern Classic. I have no doubt if he were alive today, he’d hate this. Though I find the idea of the canon a tenuous subject, I don’t necessarily avoid all the books. For the most part I absolutely loved this. I had been meaning to buy it since my old tutor from RCA asked us in class if any of us had read Story of the Eye and when my friend Tom (The Death of a Clown, Tom) said he read it when he was a teenager, and told me what it was about properly, I picked it up as soon as I finished my MA.

Story of the Eye is about a guy looking back on his life and recalling his sexual exploits as a teenager with a girl called Simone. The relationship from the off is just odd, and for that reason well-matched. They take pleasure from the same fetishes that they explore together. They share that weirdness in each other. Some of these perversions get really specific, and I mean really specific. Like in the first sexual encounter (which happens on the book’s second page, Bataille doesn’t fuck about at all, no pun intended), Simone sits butt-naked in a dish of milk and it gets the narrator really hot under his collar. It’s a piece of psychoanalytic eroticism, and it just gets weirder and weirder. I suppose it’s all tied up in misadventure and adventure, and Bataille’s own life, his psyche. If you buy a Penguin Modern Classic edition of this, you’ll get his notes on Story of the Eye (which btw was originally published under Bataille’s pseudonym, Lord Auch, you’ll see this), and an essay from Susan Sontag and Roland Barthes. I do think overall the ending is kind of abrupt... and it’s intentional but I wish Bataille had said more. Overall, I did love it for the beauty in Bataille’s choice of words to describe (what I deem to be) the surreality of sexual conquests and even the macabre at times.

Dodie Bellamy, Cunt-Ups (RECOMMEND): Oh so wonderful. This book introduced me to the joys of the cut-up method and it is a sweaty, relentless fuck of a book. I salute Dodie Bellamy. It is exactly what Sophie Robinson says in the book’s foreword, ‘a kind of erotic Midas touch’. Everything this book touches is sex, queer, wet, shaky, writhing. It is absolutely exhausting. It consists of exchanges, voices, rooted in porn, rooted in love, the unachievable and the real in its gendered body. Won’t say anymore. You may have to look hard to find a copy available to buy in the UK, but when you do, just buy it.

E. M Cioran, The Trouble with Being Born: This was the first time I bought Cioran. I was looking for new philosophy to read and came across this one line in an article, which quoted The Trouble with Being Born.

It said: ‘I have decided not to oppose anyone ever again, since I have noticed that I always end by resembling my latest enemy’.

It has been true of me sometimes in my life, to have fallen prey to imitating the ones who hurt me. It just so happened I read this line at a particularly difficult time, where somebody had failed me. So I bought the book. Did I use this text as a coping mechanism? Maybe a bit. Apparently everything goes to shit when you’re born, not when you’re hurtling towards death. That’s Cioran’s two cents. I like this book when I feel like life is never going to be okay ever again. It indulges my mindset at that point, then it gets so depressing I wake up and never read Cioran again until someday something else makes me feel lifeless. In his inherent nihilism, Cioran revives my optimism, and lust for life.

Ed. by Eileen Myles & Liz Kotz, The New Fuck You: Adventures in Lesbian Reading (RECOMMEND): Incidentally, at the same time I read that line about never opposing your enemy again from Cioran, I was at the time, ill at ease with men. So I went looking for Kathy Acker. Instead I found this, an anthology of 37 writers talking about everything. The book was published in the 90s, at this point ‘queer lit’ isn’t really a term being mobilised, and the work isn’t always for lesbians, or written by lesbians. Some stories do wane, not everything here is my cup of tea, but that’s what you find in anthologies, the diversity of voices. It’s also deeply rooted in the real. It doesn’t sugarcoat at all. There’s sex, cancer, drugs, alcoholism, cake, driving, seasons, pizza, stairs and diabetes. There’s everything.

Ultimately, to be a woman is to be in pain all your life. It’s chronic. This anthology soothes and chafes these difficult wounds.

Adam Phillips, Attention Seeking: Food for thought in the psychology literature of Adam Phillips. I like his hypotheses, and I enjoy his explanations. His writing is engaging and playful. Attention Seeking is about why and what we choose to pay attention to, why we seek attention for ourselves in four essays. He begins saying everything in life depends on what we find interesting. When we’re interested, we pay attention.

This is an argument for attention-seeking in each of its facets. There’s no conclusions or set answers. Our selectivity makes up the very basis for who we are. And to understand this book you need to pay attention to it, and if you don’t, you’re only proving Phillips right. Now isn’t that masterful?

***

That’s all this week. Next Friday I’ll be reviewing Crispin Best’s Hello published very late last year. Hugs and snugs. Stay safe. 💕💁🏽

#books#bookstagram#currentreads#quickbite#reviews#litbitch#writing#contemporaryliterature#and#20thcenturyliterature#adamphillips#eileen myles#lizkotz#emcioran#dodiebellamy#georges bataille#queerlit#psychology#poetry#covid19#reads#feminism#nihilism#philosophy#eroticism

0 notes