#ran early in the morning w a friend then went golf!

Text

how was everyone’s weekend? what’s been on loop lately? anything new you tried recently? tell me all about it!!

#i miss interacting w everyone!!!#i havent dropped by inboxes in a while bc ive been so busy and have mostly been on queue here kansjdn#i kinda miss having sleepovers too!!!#i had such a good day yesterday 🥺#ran early in the morning w a friend then went golf!#we had brunch and coffee too with another friend and just chatted abt life 🥺#we made more coffee after LOL JAKNZKSJ#i talked so much again

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Need the Sun to Break

Here’s part III of the Chaos and the Calm series! I’m absolutely falling in love with Harry and Alex, and I hope you are too. Please come in and talk to me about it, and ideas, predictions, feedback you might have- I don’t bite and I love hearing from you all!

Need the Sun to Break

October 2018

Back of the room/How come my friends already know you?/I feel like a kid/Too shy to speak up so I keep it hid

Harry’s eyes darted across the room, hoping to catch a glimpse of Alex. She had arrived at his house a few hours prior, but they hadn’t been together for a bit. Nobody really knew they were dating yet; things were so early that they had decided to hold off on announcing things for a little while. That being said, Harry wasn’t so confident he wouldn’t let things slip accidentally if someone asked him. He was so proud and excited to finally be able to call her his, but he respected that she wanted to take things slow. He had told her that things were going to move at her pace, and he wasn’t about to break that promise. So naturally, he was thrilled to see Alex engaged in what seemed like a fascinating conversation with Clare. It was the first time they had met— Clare was usually back home in Britain— but the two were already acting like old friends, and for that Harry was eternally grateful. When hearing that she and a few of his friends that worked at the label were in New York for some event or another— he thinks he heard something about a Beyoncé concert— he had jumped at the chance to host them at his house. He had been a bit apprehensive about inviting Alex over, not really for any other reason other than the fact that she wasn’t going to know too many of the attendees. She knew Julia, obviously, and by extension Matt, but other than the two of them, she was kind of at a loss for people to talk to.

Seeing her get along with his friends was endlessly relieving for Harry. Seeing Alex slightly tipsy with his friends, spilling part of her drink on herself then laughing while mopping it up only made him fall for her more. When she got up to go get a napkin to sop up her dress, he followed her into his kitchen. Smirking slightly, Harry leaned against the entryway for a moment while he watched her open and close no less than six drawers in her quest for a napkin, or a paper towel, or what, Harry wasn’t entirely sure.

“Where is that blasted towel…” Alex muttered, turning around and spotting Harry.

He walked over to the oven, where a towel hung on the door handle. “Looking for one of these, love?”

Alex shot him a nasty look, plucking the towel out from his hand, walking over to the sink, and running part of it under some water before blotting her dress. Harry had always loved green on her, said it brought out her eyes. “Y’know, Alex, you were drinking Chardonnay. I don’t think it’ll stain too bad.”

She rolled her eyes. “Yeah. I mean, I figured. Better safe than sorry though, you know? Wouldn’t want to wake up tomorrow and find a massive stain on it.”

Harry nodded. “Yeah, that makes sense. I’m glad to see you’re getting on so well with my friends.” He added, holding one of her hands gently in his.

“Clare’s an angel.” Alex blushed. “It’d practically be a sin to not like her.”

I need the sun to break/You've woken up my heart/I'm shaking, oh/My luck could change

He chuckled. “Yeah, you’re not wrong there.” As Alex leaned up against the bar, picking at a loose thread on her sleeve, Harry realized just how much his life had changed in the past month. He was falling for her even more than he thought possible, and it terrified him. He had never felt the way he felt about Alex with anyone else, and he had never let anyone in the same way he longed to let her in. Seeing her so completely at ease, talking to his friends that were becoming hers, with her hair up in high ponytail and barely a trace of makeup on her face, gave him pause. Made him think of how long he had wanted her to be his. Made him remember the night he realized he had fallen in love with her.

...

The £3 bottle of rosé long since drank and the sun long since set, Harry turned over on the old quilt to look at Alex. She was in that strange liminal stage of sleep; he wasn’t sure she’d hear him if he talked to her, but didn’t want to take chances. They had fallen asleep in the meadow like so many times before, from the time they were kids and their parents would frantically search for their whereabouts to the night before he left for the X-Factor to now, both of them 22 years old with their entire lives ahead of them. What would our 10-year-old selves think, Harry mused, if they could see where we were now? After a few moments of pondering, Harry didn’t think that their younger selves would actually be all that surprised. Him, maybe. But Alex had always had nothing but complete and utter faith in him and his music, and he always knew that her designs would take her as far as she wanted to go, even when they were sixteen and she was photoshopping his face onto Justin Timberlake’s body. She was just about to start a job at a new firm in London, and he was leaving the next afternoon— this afternoon, Harry thought with a grimace — to America to begin writing for his solo album.

The two of them had fallen asleep sometime a little past one o’clock, and Harry noted with a cursory glance at his watch that it was nearing five. Alex looked so peaceful on the blanket, and Harry had to stop himself from tucking a stray piece of hair that had fallen in front of her face behind her ear. It hit him like a ton of bricks right as the sun peeked over the horizon, and Harry knew that he was well and truly fucked. He realized that he was in love with his best friend as the light hit her face just right,. He had never known that her hair looked so red in the sunlight. Then again, he had never known that he was in love with his best friend until a few moments ago. His breath caught in his throat. Shit.

...

Been in the dark for weeks and I've realized you're all I need/I hope that I'm not too late

Ever since Alex had come back into his life, she had turned his world upside-down. He had stopped himself from telling her how he felt countless times, fearing the worst possible reaction. And God, had it been hard. So it was incredibly paradoxical that now that Alex was finally his, his was more terrified than ever about his feelings. Alex knew that he cared about her; he hoped that much was obvious. What she might not have known was just how deeply he fallen in love with her. He hadn’t said it yet, and it was eating him alive. He was committed to what he promised her, however, and wasn’t going to move anything forward until she was ready. As he leaned up against the counter, holding a still-empty tumbler that once upon a time had held a scotch straight, he realized a simple truth. Something had brought them together that May night, in the exact time and place and space where they needed to be. Whether that was God, the universe, whatever, Harry didn’t know. What he did know was that it no longer mattered that he had been pining for her, and that she didn’t know just how deeply his feelings ran. The only thing that mattered, the only thing that held any kind of significance for him as far as Alex or anything else was concerned, was that they were together. They were together, and they were happy, and how fast or slow their relationship went was all for naught as long as that remained true.

Interrupting his thoughts, Clare came over to wish the two good night, leaving Alex with a tight hug, a new contact in her phone, and a promise to meet for coffee later in the week. After she left, the two moved to a slightly more quiet and secluded spot, settling on a pair of plump chaises in an alcove off of the main living room.

“Did you get the chance to talk to anyone else?” Harry asked. Clare was wonderful, but the last thing Harry wanted was for her to be stuck feeling isolated from the group with only one or two friends that she could rely on.

Alex nodded. “Yeah, I had a pretty… animated conversation with Ella and James a few hours ago,” she said carefully, giving a small smile. “Took the mick out of me for being a Liverpool supporter, but they’re alright other than that. Got to talk to Lia before she left, think she said there’s an early meeting she’s got to be at tomorrow.” Taking a peek out of their small refuge, Harry noticed that the number of guests had indeed started to dwindle.

The party was winding down, guests had been tricking out for the last twenty or so minutes, and somewhere in the midst of his conversation with Alex the playlist had been switched from classic rock to nothing but Abba— not that he was complaining.

“I should probably get going,” Alex murmured in his ear, timidly squeezing his hand with a gentle smile. “It’s a Sunday and I have to be at work by eight.”

Harry nodded. “‘F course, love. Stay safe, text me when you get back, okay?” Alex lived nearly an hour’s subway ride away, and Harry had never been too fond of her having to travel so far, particularly so late at night. Her apartment building was fairly safe, but the surrounding area had been subject to a string of muggings in the last few weeks which had caused him a fair bit of worry.

“Of course.” Taking a quick glance to be sure they were free from prying eyes, Alex leaned in to give Harry a quick kiss on the cheek.

Oh, butterflies/You steal my sleep each night

As the clock struck three in the morning, Harry woke with a start. The few hours of sleep he had gotten had been fitful, and no amount of laying in bed or cups of tea seemed to help. With a dissatisfied grunt, Harry swung his legs over the side of his bed, pushed himself up, and padded out to the living room. Clicking on the TV, Harry flipped through channels, rolling his eyes when he was that all that was on was reruns of the Great British Bake Off and golf. Bake Off it is, he thought. Ever since Alex left, she had been on his mind. Not in the worrisome, slightly-crazy ‘I can’t stop thinking about her and I need her to be with me 24/7 way,’ in the ‘I’m so in love with this woman and it scares the shit out of me’ way.

Things were going so well as a couple, Harry couldn’t help but grow worried. Things were going so well that he began to question everything. He had never felt this content in any of his former relationships, never this assured or confident or certain. And that’s what scared him. Things were going so well that Harry thought it was inevitable that something would go wrong, that things would crash and burn before they even had a chance to learn what it meant to be a them. He was so worried about how things would turn out, so worried about their relationship, because he had never felt this way about someone before. Harry had had girlfriends before. Plenty of them, in fact, Harry grumbled, remembering the days when he could scarcely go for a walk with a woman for fear of her being deemed his ‘next conquest.’ He might have even loved one or two of them. That wasn’t the issue. He had never fallen so hard for anyone before, had never felt same way around anyone before, and he had never felt like he had so much to lose. God forbid anything went wrong, Harry stood to lose not only the love of his life, but his best friend. Stop thinking like that, he tried to beat into his head. Don’t make something out of nothing. Rationally, he knew that there were no real reasons to perpetually be stuck in a ‘worst-case-scenario’ mindset, but he was finding it difficult to dig himself out of it.

I'm halfway gone/Sleepless, I'm battle worn/And you're all I want/ So bring me the dawn

Taking a deep breath, Harry looked down at his hands, the same ones that had held hers only hours before. He didn’t need anyone else to tell him how his relationship ‘should’ or ‘shouldn’t’ work. It was only him and Alex. It had always been him and Alex, ever since they met in primary doing the Year 5 musical. Peter Pan had left something to be desired in terms of quality, but what it had accomplished was a friendship that Harry had cherished ever since his days in green tights. Harry didn’t know how their relationship would turn out. That wasn’t up to him. He could continue to love Alex, keeping their happiness at the center of every decision he made. He was weary from overthinking and weary from outside opinions, but he knew that the only thing he could reply on was the love he had for Alex and the hope of everything to come.

#Harry Styles#harry styles fanfic#harry fanfic#harry fanfiction#harry styles imagine#hs#harry#harry styles writing#harry styles smut#harry writing#one direction#fanfiction#writing#imagine#harry imagine#harry imagines#harry styles imagines#one direction fanfiction#one direction fanfic#one direction fluff#harry fluff#harry styles fluff#harry smut#one direction smut#1D#1D fluff#harry styles pref#1d pref#harry pref#harry styles preference

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Making of Reluctant Activists: A Police Shooting in a Hospital Forces One Family to Rethink American Justice

The beer bottle that cracked over Christian Pean’s head unleashed rivulets of blood that ran down his face and seeped into the soil in which Harold and Paloma Pean were growing their three boys. At the time, Christian was a confident high school student, a football player in the suburbs of McAllen, Texas, a border city at the state’s southern tip where teenage boys — Hispanic, Black, white — sung along to rap songs, blaring out the N-word in careless refrain. “If you keep it up, we’re going to fight,” Christian warned a white boy who sang the racial epithet at a party one evening in the waning years of George W. Bush’s presidency. And they did.

Use Our Content

It can be republished for free.

On that fall evening in 2005, Christian pushed and punched, his youthful ego stung to action by the warm blood on his face. A friend ushered Christian into a car and drove through the bedroom community of Mission, passing manicured golf greens, gable roofs and swimming pools, to the well-appointed home of Dr. Harold and Paloma Pean, who received their son with care and grace. At the time, even as he stitched closed the severed black skin on his son’s forehead, Dr. Pean, a Haitian exile and internal medicine physician, believed his family’s success in America was surely inevitable, not a choice to be made and remade by his adopted country’s racist legacy.

Christian’s younger brother, Alan, a popular sophomore linebacker who shunned rap music and dressed in well-heeled, preppy clothes, agitated to find the boy and fight him. “Everybody shut up and sit down,” Paloma ordered. Inside her head, where thoughts roiled in her native Spanish, Paloma recalled her brother’s advice when they were kids growing up in Mexico: No temas nada. Eres una chica valiente. Never be scared. You are a brave girl. She counseled restraint, empathy even. “Christian, we need to forgive. We don’t know how the life of this guy is that he took that reaction.” This is a country that recognizes wisdom, Paloma thought.

The Pean family’s tentative truce with America’s darker forces would not last long. In August 2015, when Alan was 26 and under care at a Houston hospital where he had sought treatment for bipolar delusions, off-duty police officers working as security guards would shoot him through the chest in his hospital room, then handcuff him as he lay bleeding on the floor. Alan would survive, only to be criminally charged by the Houston police.

The shot fired into Alan’s chest would extinguish the Pean family’s belief that diligent high achievers could outwit the racism that shadows the American promise. Equality would not be a choice left up to a trio of ambitious boys.

Nearly six years later, the Peans remain haunted by the ordeal, each of them grappling with what it means to be Black in America and their role in transforming American medicine. Christian and Dominique, the youngest Pean brother, both aspiring doctors, like their father, have joined forces with the legions of families working to expose and eradicate police brutality, even as they navigate more delicate territory cultivating careers in a largely white medical establishment.

Alan has seen his studies derailed. He remains embroiled in a lawsuit with the hospital and wavers over his responsibility to the fraternity of Black men who did not survive their own racist encounters with police.

And Paloma and Harold, torn from their Mexican and Haitian roots, look to buoy and reassure their sons, propel them to the future they have earned — even as they wonder whether the America they once revered doesn’t exist.

“People don’t want to admit we have racism,” Paloma told me. “But Pean and me, we know the pain.”

Harold Pean doesn’t recall being raised Black or white. His native Haiti was fractured by schisms beyond skin color.

Harold was 13 when he, his sister and five brothers woke on a May morning in 1968 to find that their father, a prominent judge, had fled Port-au-Prince on one of the last planes to leave the island before another anti-Duvalier revolt pitched the republic into a season of executions. His father had received papers from President François Duvalier demanding he sign off on amendments to Haiti’s Constitution to allow Duvalier to become president for life. Harold’s father refused. Soldiers arrived at the Pean house days after his father escaped.

The Republic of Haiti was marked by Duvalier’s capricious cruelty during Harold’s youth, but as the son of a judge and grandnephew of a physician, he enjoyed a comfortable life in which the Pean children were expected to excel in school and pursue professional careers: engineering, medicine, science or politics. In school, the children learned of their ancestors’ brave heroics, African slaves who revolted against French colonialists and established a free republic, and they saw Black men and women running fruit stands, banks, schools and the government. “I didn’t experience racism as a kid,” Harold remembers. “When you find racism as a kid, that makes you doubt yourself. But I never doubted myself.”

Two years after Harold’s father fled Haiti, his mother joined her husband in New York, leaving the Pean children in the care of relatives. In 1975, Harold and his siblings left Haiti and immigrated to New York City. New York was cold, like being inside a refrigerator, and the streets were much wider than in Haiti. His father had found a job as an elevator operator at Rockefeller Center.

At the time, Harold’s older brother, Leslie, was attending medical school in Veracruz, Mexico, where tuition was cheaper than in the States, and his father urged Harold to join him. A native French speaker who knew no Spanish, Harold learned anatomy, pathology and biochemistry in a foreign tongue. And he was fluent in Spanish by the time he met María de Lourdes Ramos González, known as Paloma, on Valentine’s Day 1979 at a party in Veracruz. Harold remembers the moment vividly: a vivacious young woman spilling out of a car in the parking lot, shouting her disapproval at the low-energy partygoers. “‘Everybody is sitting here!’”

“They were so quiet,” Paloma remembers. She pointed to the man she would eventually marry, “You! Dance with me!”

Growing up as the only girl in her parents’ modest ranch in Tampico, a port city on the Gulf of Mexico, Paloma was expected to stay inside sewing, cleaning and reading while her three brothers ventured out freely. She felt loved and protected but fumed at her circumscribed life, pleading for a car for her quinceañera and pushing her father, the boss at a petroleum plant, to allow her to become a lawyer. Her father thought she should instead become a secretary, teacher or nurse. “I said, ‘Why are you telling me that?’ He said, ‘Because you are going to get married, you are going to end up in your house. But I want you to have a career in case you don’t have a good husband, you can leave.’” That good husband, Paloma understood, could be Mexican or white. She remembers her father saying, “I don’t want Black or Chinese people in my family.”

After earning a degree to teach elementary school, Paloma moved to Veracruz. When she was 21, her father installed her in a boarding house for women. Watched over by a prying house matron, Paloma and Harold’s courtship unfolded under the guise of Harold teaching Paloma English. The couple dated for several years before Paloma told her father she wanted to get married to the handsome, young medical student. Harold had returned to New York, and Paloma was eager to join him.

Her father was skeptical. He had spent a few months in Chicago and seen America’s racial unrest. “He told me, ‘My daughter, I don’t have any objections. He’s a good man, but I’m scared for you. I’m scared for my grandkids because, let me tell you, your kids are going to be Black. And I don’t know if you are ready to raise Black kids in the U.S.,’” Paloma remembers. “At that moment I didn’t understand what he meant.”

In the early 1980s, as Harold and Paloma started their lives together, the news from America spoke to racial divisions. The country was seized by a presidential campaign, in which the actor and former California Gov. Ronald Reagan courted segregationist Southern voters at a Mississippi fairground a few miles from where civil rights workers had been murdered in 1964. In Miami, Black residents protested after an all-white, all-male jury acquitted four white police officers who had beaten an unarmed Black motorcyclist, Arthur McDuffie, to death with their fists and nightclubs. Beaten him “like a dog” McDuffie’s mother, Eula McDuffie, told reporters. Over three days of violent street protests, 18 people died, hundreds were injured, buildings burned and President Jimmy Carter called in the National Guard.

The couple lived in Queens, where Christian was born in 1987, and Harold found work while pursuing medicine. He inspected day care schools for sanitary violations. As he traveled around the city’s streets, he never felt imperiled by the color of his skin. “People said there was racism, but I didn’t see it.” On the few occasions he noticed a police officer or shop security trailing him, he put it out of his mind, trying not to pursue the logic of what had happened. “We never talked about it in the house,” he said. “We were concentrating on achieving whatever goals we had to do.”

He told me, ‘My daughter, I don’t have any objections. He’s a good man, but I’m scared for you. I’m scared for my grandkids because, let me tell you, your kids are going to be Black. And I don’t know if you are ready to raise Black kids in the U.S.’ At that moment I didn’t understand what he meant.

– Paloma Pean

Moving with common purpose, Harold and Paloma went wherever the young doctor could find work. Caguas, Puerto Rico, where Alan was born in 1989; back to New York for Harold’s residency in internal medicine at the Brooklyn Hospital Center; then Fort Pierce, Florida, where Dominique was born in 1991; and eventually to McAllen, Texas. Harold’s brother, Leslie, had established his practice in Harlingen, 20 miles north of the Mexican border. Harold was comforted to have family nearby and Paloma wanted to reach her family in Mexico more easily. Still, the first hospital that recruited Harold offered an uncharitable contract; he had to cover half the costs of running the medical practice while seeing only a few patients.

Harold remembers few, if any, other Black doctors in the area. Paloma was more certain about the dearth of diversity in the medical ranks: “We were among the only Blacks in the [Rio Grande] Valley and the only [primary care] doctor.” Three months into the contract, Paloma, who managed the office’s finances, could see they were losing money. She pressed her husband to renegotiate. When he refused, she went to the hospital herself. “I love the Valley,” she told the administrator, her optimism unimpeachable. “But I came here to work. My husband is a very good doctor and you are not paying what he deserves. If you don’t pay him, we are going to move.” Stunned, the administrator, who was white, agreed to her demands, and Paloma returned triumphant.

Daily life was a blur. The couple worked assiduously at the medical practice, finding allies at the hospital who applauded their diligence and, by Harold’s account, rooted for their success. But race was never far from the surface. When a medical assistant at the office told Paloma that another doctor had asked her repeatedly if she was still working with “the Black doctor,” Paloma fumed. At the medical center’s Christmas party that year, Paloma approached the doctor. “‘Are you so and so, the doctor?’ I said. ‘Well, I’m Paloma Pean, and I’m here just to let you know the name of my husband. My husband is Harold Pean. P-E-A-N. His last name is not Black.’ And I said, ‘Thank you, and nice to meet you.’ He opened his eyes big, and then I left.”

At home, Paloma insisted on a Catholic upbringing, and the family prayed every evening after dinner in three languages (Paloma in Spanish, Harold in French, the boys in English). Harold pushed his three boys in the ways his own parents had. “I was expecting them to be either a doctor or a professional, like my parents expected us to be professionals.”

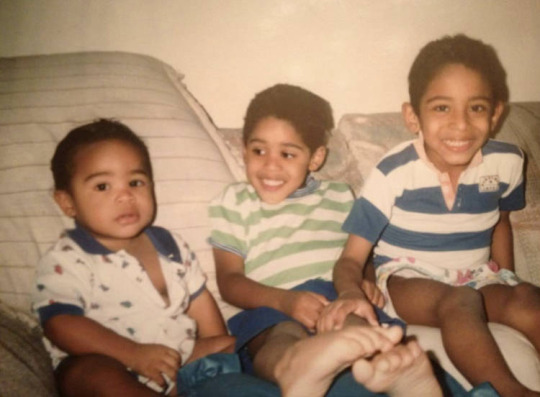

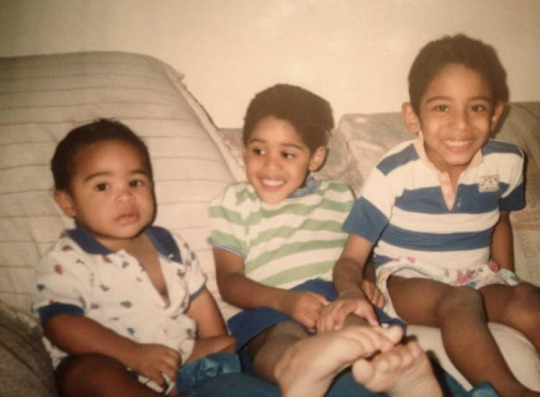

That was the period in which the three Pean boys — Christian, Alan and Dominique — tried to sort out their Blackness in a place that was almost entirely Hispanic and white. Accustomed to being surrounded by Latinos in Florida and later in McAllen, Paloma recalled her father’s warnings. When the boys started nursery school, they were the only Black babies. “That’s when I thought, I need to start to make them very proud of what they are.”

The questions about skin color came early for Dominique, the youngest brother. His fellow kindergartners watched Paloma, a Latina, drop off her son for school in the mornings, and a cousin, who was Chinese, pick him up after the last bell. (Paloma’s brother had married a Chinese woman.) “They asked me if I was adopted,” Dominique remembers clearly. He told his mother, “I don’t look like you.” Would his father, pretty-please, pick him up at school to show the kids, once and for all that, no, he was not adopted? It was a conclusive victory. “The kids stopped bringing it up. ‘OK, you’re Black!’”

The boys steered in different directions, employing sports, fashion and culture to signal their preferences to the perplexed children of McAllen. “I really identified with my Hispanic side, but when people see me, they see a Black kid,” remembers Dominique. He ventured to look “more Black,” braiding his hair into cornrows and wearing FUBU, a line of clothing that telegraphed Black street pride. Meanwhile, Alan forged a collegiate look. He listened to “corny, white boy music” (Christian’s words) and dressed in Abercrombie & Fitch.

The boys were left to their own to make sense of the off-handed remarks at school and on the football field. You’re Black, you’re supposed to jump farther. Do Black kids have extra muscles in their legs? You sound smart for a Black kid. You sound white. Does anyone know if the Pean brothers have big dicks?

“There was open ignorance back then,” Christian remembers. The boys absorbed and repelled the remarks, protesting vigorously only when the N-word exploded in front of them. One of Alan’s friends on the football team asked him, “What’s up, d…igger?” replacing the N and smirking knowingly. Alan responded, “Why would you even do that?”

It never occurred to Dr. Pean to give his teenage boys “the talk,” the dreaded conversation Black parents initiate to prepare their sons for police encounters. The day Christian came home, blood running down his forehead, Harold argued against pressing charges. “The chief of police was my friend, and I had a lot of police patients,” Harold said. “I would meet white people or Black or Hispanic, and I never thought they would see me differently.”

Where Harold was silent, Paloma was explicit. The history of African Americans amazed her. Dominique remembers his mother saying, “Being Black is beautiful. They came to the United States as slaves, and now they are doctors. That blood runs in you, and you are strong.”

Of all the sons, the oldest boy, Christian, seemed the most curious about exactly what his heritage and his skin color had to do with who he was. Why hadn’t his mother married a Mexican man? Why did other kids want to know if his dark skin rubbed off? Could they touch his hair? At age 6, Christian told his mother a Hispanic girl at school had called him the N-word and his mother a “wetback” as he sat in the cafeteria sipping a Capri Sun.

The racist lexicon of American youth befuddled Paloma. She asked Christian, “What does that mean?” “That word is bad,” he responded.

Christian’s doubts about his father’s faith in American meritocracy emerged early. After he endured racist slurs and other offensive remarks at school, Christian told Harold that he felt he was treated differently “because I’m Black.”

“No, Chief,” his father responded, “hard work gets rewarded. It’s not going to help anybody to get down on your race.”

As mixed-race children, the legitimacy of the Pean brothers’ Blackness trailed them into adulthood. At Georgetown University, Christian found an abundance of Black students for the first time — African Americans and immigrants from Nigeria, Ghana and the Caribbean — and unfamiliar fault lines began to emerge.

“When I was in high school, there was never Black immigrants vs. Black Americans,” Christian said. But in college and later in medical school at Mount Sinai in East Harlem, Christian fielded questions from other Black students about whether scholarships for people of color should be set aside for African Americans descended from slaves, not children of Black immigrants like him.

At the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., Dominique was facing similar questions about his racial camp. When he joined the board of the Student Organization of Latinos, he was asked, “Are you Latino enough?”

“When I’m on the street, people see a Black man. But when I’m with my Black friends, they’re like, Dom, you’re not really Black,” he said. The questions followed them into their personal lives: African American women berating Christian and Dominique for dating women who were not Black.

If the Pean brothers’ Haitian and Mexican roots called into question their rightful membership among African Americans, the police discerned no difference. After graduating from high school in the McAllen suburbs, Alan matriculated to the University of Texas-Austin, a sprawling campus filled almost entirely with white, Hispanic and Asian students. Alan, laid-back and affable, made friends easily. It surprised him then when a security officer trailed him at a store in the mall while he shopped for jeans. “That was the moment when I was like, ‘Oh, I’m Black,” he said.

In August 2015, Alan Pean started the fall semester at the University of Houston where he had transferred to finish his degree in biological sciences. Within days, he began to feel agitated, and his mind slipped into a cinematic delusion in which he believed he was a stunt double for President Barack Obama. At other times, armed assassins chased him.

Alarmed by Alan’s irrational Facebook posts and unable to reach him by phone, Christian called his parents, who were sitting in a darkened McAllen movie theater. He urged them to get to Houston. This was not a drill. In 2009, Alan had spent a week at a hospital for what doctors believed was bipolar disorder.

In the lucid moments between the delusions traversing his psyche, Alan knew he needed medical help. Around midnight, on Aug. 26, 2015, he drove to St. Joseph Medical Center in Houston, swerving erratically and crashing his white Lexus into other cars in the hospital parking lot. As he was hustled into the emergency room on a stretcher, Alan screamed, “I’m manic! I’m manic!”

The following morning, Paloma and Harold flew to Houston and arrived at St. Joseph Medical Center expecting to find sympathetic nurses and doctors eager to aid their troubled son. Both Harold and Christian had placed calls to the emergency department, alerting them to Alan’s mental health history. Instead of finding their son being cared for as a man in the midst of a delusion, Harold and Paloma discovered doctors had not ordered a psychiatric evaluation or prescribed psychiatric medication.

Barred from seeing their son and galled by the hospital’s refusal to provide psychiatric care, Harold and Paloma went to their hotel to try to rent a car so they could take Alan for treatment elsewhere. They were gone for half an hour.

In his hospital room, Alan became more agitated. He believed the oxygen tanks next to his bed controlled a spaceship and that he urgently needed to deactivate a nuclear device using the buttons on his bed. He stripped off his hospital gown and wandered into the hallway naked. A nurse called a “crisis code” and two off-duty Houston police officers, one white and one Latino, charged into Alan’s room. They were unaccompanied by any nurses or doctors, and they closed the door behind them.

The officers would say later that Alan hit one of them and caused a laceration. The first officer fired a stun gun. When the electroshock failed to subdue Alan, according to officers’ statements, the second officer said he feared for his safety and fired a bullet into Alan’s chest, narrowly missing his heart.

Paloma and Harold arrived back at the hospital to find themselves plucked from their ordered lives and hurled into a world in which goodwill and compassion had vanished. Alan was in intensive care with a gunshot wound, and police officers were asking questions about his criminal record. (He had none.) Alan would be detained for attacking the security officers, they were told, and it was now a criminal matter.

Christian flew in from New York, Dominique from Fort Worth, and Uncle Leslie from McAllen. Inconclusive conversations with a hospital administrator strained their patience. “That’s when I was told that we had to have a lawyer to see him,” Leslie said, trembling even as he recounted it nearly six years later.

Paloma was bewildered that her appeals for fairness went unanswered. “I was expecting they would allow me to see my son immediately. I said, ‘My son is a good boy. Let me go and see my kid, please! Please!’” She felt like a ghost, wandering the hospital unstuck in time. Suddenly, the complexions and accents of everyone around her mattered: One police officer was surely white, she thought, the other Hispanic, but maybe born in the U.S.? The nurses were Asian, perhaps Filipino?

Days later, the hospital relented, and nurses led her to a glass window. Alan lay sedated, a tube down his throat, handcuffed to the hospital bed. Paloma’s chest tightened and she felt faint. “I pinched myself, and I said, ‘This cannot be true.’ I screamed to my Lord, ‘Please hold me in your hands.’”

“That’s when I really understood what my father was talking about,” Paloma told me. This, she thought, is how America treats Black men.

Over the next few weeks, it became impossible to unravel what exactly had happened to Alan. Sgt. Steve Murdock, a Houston police investigator, told Christian that Alan had been out of control, picking up chairs, acting like a “Tasmanian devil.” When the hospital eventually allowed the Pean family into Alan’s room, Alan was groggy, his wrists and hands swollen. Standing by his bedside, Uncle Leslie asked Paloma, Harold, Dominique and Christian to hold hands and pray. A week later, Alan was transferred to a psychiatric unit, and his delusions began to lift. A few days later, he was released from the hospital.

It was pouring rain the day the Pean family left Houston. Alan insisted on driving — he always drove on family trips — and his parents and brothers, desperate for a return to normalcy, agreed. Paloma prayed on her rosary in the backseat, nestled next to Christian. Alan drove for 20 minutes until someone suggested they stop and eat. At that moment, Alan turned to his father, “Did I really just drive out of Houston with a bullet wound still in my chest? Pop, I probably shouldn’t be driving.” Dominique drove the last five hours home.

Back in McAllen, neighbors passed on their sympathies, dumbfounded that the Pean’s “well-behaved” middle child, the son of a “respected doctor,” had been shot. Just as Harold years before had sewn up the gash in Christian’s head left by a racially charged fistfight, he and Christian now tended to the piercing pain in Alan’s ribs and changed the dressings of his wound.

That Alan survived a gunshot to the chest meant he faced a messy legal thicket. The police charged him with two accounts of aggravated assault of a police officer and, three months after the shooting, added a third charge of reckless driving. The criminal charges shocked his family.

“At the time, I thought the police and the hospital would apologize, or go to jail,” said Dominique. “If a doctor amputated the wrong leg, there would be instant changes.” A lawyer for the family readied a lawsuit against the hospital and demanded the federal government investigate the hospital’s practice of allowing armed security officers into patients’ rooms.

The seed of injustice planted in Alan’s chest took root in the Pean family.

In October 2015, two months after the shooting, Christian summoned the family from Texas to New York City to march in a #RiseUpOctober protest against police brutality. On a brisk fall day, the five Peans held hands in Washington Square Park wearing custom-made T-shirts that read, “Medicine, Not Bullets.” Quentin Tarantino, the film director, had flown in from California for the event, and activist Cornel West addressed the combustive crowd. Families shouted stories of loved ones killed by police.

Harold had never protested before and stood quietly, taking in the crowds and megaphone chants. Paloma embraced the spirit of the march, kissing her sons with hurricane force as the crowd made its way through Lower Manhattan. She found common cause with mothers whose Black sons had not survived their encounters with police. “We were very lucky that my son was alive,” Paloma said.

The Peans’ attorney had advised Alan not to speak publicly, fearing it would torpedo the lawsuit against the Houston hospital. Christian had his own reservations; he was applying for orthopedic residency programs, a notably conservative field in which only 1.5% of orthopedic surgeons are Black. “Everything is Google-able,” he told me. “I wasn’t sure what people would think about me being involved in Black Lives Matter or being outspoken.”

When protesters began to chant “F— the police!” Christian moved into the crowd to change its tenor. He argued briefly with a white family whose daughter had been shot in the head and killed. This isn’t how we move forward, he told them. Christian wanted to summon empathy and unity. Instead, he saw around him boiling vitriol. The protest turned unruly; 11 people were arrested.

Afterward, Alan expressed shock at the crowds, so consumed with anger. Christian wondered, How many of us are out there?

Six months passed, eight months. Expectations of quick justice left the Pean family like a breath. The Houston Police Department declined to discipline the two officers who tased and shot Alan. Mark Bernard, then chief executive officer of St. Joseph hospital, told federal investigators that given the same circumstances, the officers “would not have done anything different.”

A brief reprieve arrived in March 2016, when a Harris County grand jury declined to indict Alan on criminal assault charges, and the district attorney’s office dropped the reckless driving charge. The family’s civil lawsuit against the hospital; its corporate owner, IASIS Healthcare Corp.; Criterion Healthcare Security; the city of Houston; and the police officers dragged on, one lawyer replaced by another, draining the family checkbook.

The Peans, meanwhile, registered each new death of a Black person killed by police as if Alan were shot once more. “It was all I could think about, I had dreams about it,” Dominique said. “I felt powerless.” Memories stored away resurfaced, eliciting doubts about a trail of misunderstood clues and neon warnings. Dominique had been close in age to Trayvon Martin when the Florida teenager was killed in 2012. Dominique remembers thinking, “It’s terrible, it’s wrong, but it would never happen with me. I have nice clothes on. I’m going to get my master’s and become a doctor.”

Even Uncle Leslie, who each year donated generously to the Fraternal Order of Police and had brushed off the numerous times police had stopped his car, caved under the overwhelming evidence. “I never related to the police killings until it happened to us,” he confessed. “Now I doubt about whether they are protecting society as a whole.” He has stopped giving money to the police association.

By 2017, Christian, Alan and Dominique had reunited in New York City. For a time, they shared an apartment in East Harlem. Their industrious lives resumed in haste; young men with advanced degrees to earn, careers to forge, loves to be found, just as their parents had done at that dud of a party in Veracruz.

Primed by his own experiences, the nick on his forehead a reminder of earlier battles, Christian pressed the family to speak out. Appointed the family spokesperson, he expanded the problems that would need fixing to guarantee the safety of Black men on the streets and in hospitals: racial profiling, health care inequities, the dearth of Black medical students. Working at a feverish pace, he aced crushing med school exams and pressed more than 1,000 medical professionals across the country to sign a petition protesting Alan’s shooting and the use of armed security guards in hospitals.

“My perspective was, we should be public about this,” Christian said. “We don’t have anything to hide.”

He embraced activism as part of his career, even if it meant navigating orthopedic residency interviews with white surgeons who eyed his résumé with skepticism. Would he be too distracted to be a good surgeon? He delivered a speech at his medical school graduation, and wrote a textbook chapter and spoke at the Mayo Clinic on health care inequities. Medical school deans asked Christian to help shape their response to the deaths of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, and friends sought out his opinion. “For many people, I’m their only Black friend,” he said. Christian has told the story of Alan’s shooting over and over, at physician conferences and medical schools to shine a bright light on structural racism.

Over the months we spoke, Christian, now 33, juggled long days and nights as chief resident of orthopedic trauma at Jamaica Hospital in Queens with his commitments to Physicians for Criminal Justice Reform, Orthopedic Relief Services International and academic diversity panels. He is the über-polymath, coolly cerebral in the operating room and magnetic and winning in his burgeoning career as a thought leader.

Christian’s family imagines he will run for office someday, a congressman, maybe. “He’s charismatic, he has good ideas,” said Dominique. “He’s got big plans.”

Dominique, too, has tried to spread the gospel, pushing for action where he could. He led an event in 2016 at the University of North Texas in Fort Worth using Alan’s story as a case study in the catastrophic collision of racism, mental health and guns in hospitals.

When he moved to New York for medical school, joining his brothers, Dominique was anxious when he spotted police officers on the street. “I would try to be more peppy or upbeat, like whistling Vivaldi.” But with each death — Stephon Clark, Atatiana Jefferson, Breonna Taylor, Daniel Prude, George Floyd, Rayshard Brooks, Daunte Wright — he has come to view these offerings as pointless. “After Alan, it doesn’t matter how big I smile,” Dominique decided.

Now 29 and a third-year medical student at Touro College of Osteopathic Medicine in Harlem, he said, “You can have all these resources and it doesn’t mean anything because of the color of your skin, because there is a system in place that works against you. It’s been so many years, and we didn’t get justice.”

Dominique has devised a routine for each new shooting: watch the videos of Black men and women killed by police or white vigilantes and read about their cases. Then set them aside and pivot back to his studies and school where there are few other Black doctors in training.

“I can escape by doing that,” he told me. “I still need to do well for myself.”

For Alan, as the years passed, time took on a bendable quality. It snapped straight with purpose — a talk show appearance on “The Dr. Oz Show,” presentations with his brothers at medical schools in Texas, Massachusetts and Connecticut — and then lost its shape to resignation. Survival had bought him an uneasy liberty: He feared squandering the emotional potency of his own story but remained squeamish at the prostrations demanded by daytime TV shows, the tedium of repeating his story in front of strangers, doubting whether his life’s misfortune was fueling social progress or exploiting a private tragedy.

In 2017, Alan enrolled at the City University of New York to study health care management, digging into a blizzard of statistics about police shootings and patients in crisis, and transferred the following year to a similar program at Mount Sinai. But by last fall, Alan had settled into a personal malaise. He dropped out of Mount Sinai’s program, and spent hours in his room, restless and uncertain.

Why is it so hard to register that an unarmed person should not be shot?

– Alan Pean

“I’m still working with coming to terms with who I am, my position in the family,” said Alan, 32. “Christian is an orthopedic surgeon. Dominique is in medical school.” After years of pursuing various degrees (biology, health care management, physician assistant, public health), that might not be who he is after all.

“Inside I didn’t want to do it,” he said. “It translates as a failure.”

“Alan goes back and forth about whether he wants to write about it or go back to his regular life,” Christian said. “I see him all the time, every day, being disappointed in himself for not being more outspoken, not feeling the free will to choose what to do with this thing.”

Isn’t it enough that he survived?

Alan sees a therapist and takes medication for bipolar disorder. He practices yoga. When he breathes deeply, his chest tingles, most likely nerve damage from where the bullet pierced. After a great deal of thinking, he has turned to writing science fiction and posting it online. The writing comes easily, mostly stories of his delusions told with exquisite detail — people, good and bad, with him in a place “that looks like Hell.”

Outside of his apartment in New York, there are few places he can find sanctuary. Even as the coronavirus emptied the streets, he walked around the city, his eyes scanning for police cars, police uniforms, each venture to the store a tactical challenge. He selects his clothes carefully. “Never before 2015 had police officers stood out to me. Now, if they are a block away, I see them. That’s how real the threat is. I have to think, ‘What am I wearing? Do I have my ID? Which direction am I going?’

“If I were a white person, do they ever think those things?”

Reports of new shootings stir up his own trauma, and Alan trembles at the betrayal. “Why is it so hard to register that an unarmed person should not be shot?”

Covid presented new trauma for the Pean family, and underscored the nation’s racial divide. The three brothers largely were confined to their apartment. Dominique attended medical school classes online while Christian volunteered to work at Bellevue, a public hospital struggling to treat a torrent of covid patients who were dying at a terrifying pace. Many patients spoke only Spanish, and Christian served as both physician and interpreter.

The patients coming to Bellevue were nearly all Black or Latino and poor, and Christian grew angrier each day as he saw wealthier private hospitals, including NYU Langone just a few blocks away, showered with resources. The gaping death rates between the two hospitals would prove startling: About 11% of covid patients died at NYU Langone; at Bellevue, about 22% died. “This wasn’t the kind of death I was used to,” Christian said.

At the peak of the epidemic in New York, Christian video-called his dad at home in Mission, Texas, and cried, exhausted and overwhelmed. Harold and Paloma had largely shuttered their clinic after several staff members became infected, but Harold continued to see urgent cases. Knowing the dangers to front-line health care workers, Christian was scared for his parents. “I was worried my dad wasn’t going to protect himself,” he said. “And that I was going to lose one of my parents and I wasn’t going to be able to say goodbye.”

All that was stirring inside Christian when Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin callously murdered George Floyd in May 2020, sparking protests across the globe. Black Lives Matter demonstrators filled New York City’s streets, and Christian and Dominique joined them. Alan did not; the lockdown and blaring ambulance sirens had left him anxious and hypervigilant, and after months indoors, he feared open spaces.

“I’m going to wait this one out,” he told Christian.

On the streets, surrounded by the fury and calls for change, Christian wore his white doctor’s coat, a potent symbol of solidarity. “I wanted to show that people who were on the front lines of the pandemic realized who the pandemic was affecting was reflective of the racism that led to George Floyd’s death.” When they returned home, Christian told Alan that the multiethnic makeup of the protesters surprised him. “I think maybe people’s minds are changing,” Christian said. “It was beautiful to see.”

Nearly a year later, on April 20, 2021, a jury found Chauvin guilty of murder, and Christian felt a wash of relief. But in the days that followed, news coverage erupted about the fatal police shooting of a 13-year-old Latino boy in Chicago, and the death of a 16-year-old Black girl in Columbus, Ohio, also at the hands of police. The Pean family was unusually muted. “We only exchanged a few texts about it as a family,” Christian said. “We said maybe things are changing, maybe not.”

The Pean sons will scatter soon: Christian to Harvard University for a trauma medicine fellowship; Dominique to medical rotations at Nassau University Medical Center; and Alan to McAllen, where he will oversee the financial operations of his parents’ business. It will be Alan’s first time living alone. “The one semester I was almost going to live by myself I was in Houston, and I got shot. I need to do this by myself to know I can.”

Watching violence unravel one of his son’s lives has haunted Dr. Harold Pean — the threats to Black lives in American cities not escaped as easily as a Haitian dictator.

But Harold, 66, is reluctant to allow Alan’s shooting to rewrite his American gospel; the shooting was a personal tragedy, not a transmutation of his identity. He pushes the memories from his mind when they appear and summons generosity. “Whatever the bad stuff, I keep it inside. I try to psych myself to think positively all the time,” he said. “I want to see everyone like a human.”

He has convinced himself that no more violence will befall his sons or, someday, his grandchildren. Still, he can no longer reconcile the tragedy of Alan’s shooting with his Catholic beliefs. “If God was powerful, a lot of bad things would not have happened,” he said.

“It’s difficult for him to acknowledge that he’s struggling,” Christian said of his father. “He’s a resilient person. He’s never talked about the added burden of being a Black man in America.”

“I think Paloma is the one keeping my brother together,” Uncle Leslie told me.

But who is keeping Paloma together? To her sons, her husband, her fellow parishioners, Paloma, 63, brims with purpose. She’s a fighter, an idealist. But at night, she sleeps with the phone beside her bed. When it rings, she jumps. Are you OK? In her dreams, she is often in danger. Many nights, she lies awake and talks aloud to God. “Why? For what? Tell me, Lord.” (She speaks to the Lord in Spanish. “In English, I think he will not understand me!”)

Paloma’s activism is quietly public: her presence in the community of mostly white doctors; her motherly boasts about Christian and Dominique becoming physicians and Alan’s return to McAllen; her insistence that racism is real in a part of the country where “White Lives Matter” signs abound. “I’m on a mission,” she said. “I want to disarm hate.”

But deep within her, that sense of purpose lives beside a fury she can’t quell and a disappointment so profound it can make it hard to breathe. She wonders if God is punishing her for abandoning Mexico, and whether the U.S. soil in which she chose to grow her own family is poisoned. “Sometimes I feel like I want to leave everything,” she told me. “I feel like I don’t understand how people can be so selfish here in America.”

They are dark thoughts that go largely unspoken, secrets kept even from her mother, age 90, who now lives with them in McAllen. Six years have passed since Alan was shot, and Paloma still has not told her mother what happened in that Houston hospital room. Nor will she ever.

“The pain I went through,” Paloma said, “I don’t want to give that pain to my mom.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

The Making of Reluctant Activists: A Police Shooting in a Hospital Forces One Family to Rethink American Justice published first on https://smartdrinkingweb.weebly.com/

0 notes

Text

The Making of Reluctant Activists: A Police Shooting in a Hospital Forces One Family to Rethink American Justice

The beer bottle that cracked over Christian Pean’s head unleashed rivulets of blood that ran down his face and seeped into the soil in which Harold and Paloma Pean were growing their three boys. At the time, Christian was a confident high school student, a football player in the suburbs of McAllen, Texas, a border city at the state’s southern tip where teenage boys — Hispanic, Black, white — sung along to rap songs, blaring out the N-word in careless refrain. “If you keep it up, we’re going to fight,” Christian warned a white boy who sang the racial epithet at a party one evening in the waning years of George W. Bush’s presidency. And they did.

Use Our Content

It can be republished for free.

On that fall evening in 2005, Christian pushed and punched, his youthful ego stung to action by the warm blood on his face. A friend ushered Christian into a car and drove through the bedroom community of Mission, passing manicured golf greens, gable roofs and swimming pools, to the well-appointed home of Dr. Harold and Paloma Pean, who received their son with care and grace. At the time, even as he stitched closed the severed black skin on his son’s forehead, Dr. Pean, a Haitian exile and internal medicine physician, believed his family’s success in America was surely inevitable, not a choice to be made and remade by his adopted country’s racist legacy.

Christian’s younger brother, Alan, a popular sophomore linebacker who shunned rap music and dressed in well-heeled, preppy clothes, agitated to find the boy and fight him. “Everybody shut up and sit down,” Paloma ordered. Inside her head, where thoughts roiled in her native Spanish, Paloma recalled her brother’s advice when they were kids growing up in Mexico: No temas nada. Eres una chica valiente. Never be scared. You are a brave girl. She counseled restraint, empathy even. “Christian, we need to forgive. We don’t know how the life of this guy is that he took that reaction.” This is a country that recognizes wisdom, Paloma thought.

The Pean family’s tentative truce with America’s darker forces would not last long. In August 2015, when Alan was 26 and under care at a Houston hospital where he had sought treatment for bipolar delusions, off-duty police officers working as security guards would shoot him through the chest in his hospital room, then handcuff him as he lay bleeding on the floor. Alan would survive, only to be criminally charged by the Houston police.

The shot fired into Alan’s chest would extinguish the Pean family’s belief that diligent high achievers could outwit the racism that shadows the American promise. Equality would not be a choice left up to a trio of ambitious boys.

Nearly six years later, the Peans remain haunted by the ordeal, each of them grappling with what it means to be Black in America and their role in transforming American medicine. Christian and Dominique, the youngest Pean brother, both aspiring doctors, like their father, have joined forces with the legions of families working to expose and eradicate police brutality, even as they navigate more delicate territory cultivating careers in a largely white medical establishment.

Alan has seen his studies derailed. He remains embroiled in a lawsuit with the hospital and wavers over his responsibility to the fraternity of Black men who did not survive their own racist encounters with police.

And Paloma and Harold, torn from their Mexican and Haitian roots, look to buoy and reassure their sons, propel them to the future they have earned — even as they wonder whether the America they once revered doesn’t exist.

“People don’t want to admit we have racism,” Paloma told me. “But Pean and me, we know the pain.”

Harold Pean doesn’t recall being raised Black or white. His native Haiti was fractured by schisms beyond skin color.

Harold was 13 when he, his sister and five brothers woke on a May morning in 1968 to find that their father, a prominent judge, had fled Port-au-Prince on one of the last planes to leave the island before another anti-Duvalier revolt pitched the republic into a season of executions. His father had received papers from President François Duvalier demanding he sign off on amendments to Haiti’s Constitution to allow Duvalier to become president for life. Harold’s father refused. Soldiers arrived at the Pean house days after his father escaped.

The Republic of Haiti was marked by Duvalier’s capricious cruelty during Harold’s youth, but as the son of a judge and grandnephew of a physician, he enjoyed a comfortable life in which the Pean children were expected to excel in school and pursue professional careers: engineering, medicine, science or politics. In school, the children learned of their ancestors’ brave heroics, African slaves who revolted against French colonialists and established a free republic, and they saw Black men and women running fruit stands, banks, schools and the government. “I didn’t experience racism as a kid,” Harold remembers. “When you find racism as a kid, that makes you doubt yourself. But I never doubted myself.”

Two years after Harold’s father fled Haiti, his mother joined her husband in New York, leaving the Pean children in the care of relatives. In 1975, Harold and his siblings left Haiti and immigrated to New York City. New York was cold, like being inside a refrigerator, and the streets were much wider than in Haiti. His father had found a job as an elevator operator at Rockefeller Center.

At the time, Harold’s older brother, Leslie, was attending medical school in Veracruz, Mexico, where tuition was cheaper than in the States, and his father urged Harold to join him. A native French speaker who knew no Spanish, Harold learned anatomy, pathology and biochemistry in a foreign tongue. And he was fluent in Spanish by the time he met María de Lourdes Ramos González, known as Paloma, on Valentine’s Day 1979 at a party in Veracruz. Harold remembers the moment vividly: a vivacious young woman spilling out of a car in the parking lot, shouting her disapproval at the low-energy partygoers. “‘Everybody is sitting here!’”

“They were so quiet,” Paloma remembers. She pointed to the man she would eventually marry, “You! Dance with me!”

Growing up as the only girl in her parents’ modest ranch in Tampico, a port city on the Gulf of Mexico, Paloma was expected to stay inside sewing, cleaning and reading while her three brothers ventured out freely. She felt loved and protected but fumed at her circumscribed life, pleading for a car for her quinceañera and pushing her father, the boss at a petroleum plant, to allow her to become a lawyer. Her father thought she should instead become a secretary, teacher or nurse. “I said, ‘Why are you telling me that?’ He said, ‘Because you are going to get married, you are going to end up in your house. But I want you to have a career in case you don’t have a good husband, you can leave.’” That good husband, Paloma understood, could be Mexican or white. She remembers her father saying, “I don’t want Black or Chinese people in my family.”

After earning a degree to teach elementary school, Paloma moved to Veracruz. When she was 21, her father installed her in a boarding house for women. Watched over by a prying house matron, Paloma and Harold’s courtship unfolded under the guise of Harold teaching Paloma English. The couple dated for several years before Paloma told her father she wanted to get married to the handsome, young medical student. Harold had returned to New York, and Paloma was eager to join him.

Her father was skeptical. He had spent a few months in Chicago and seen America’s racial unrest. “He told me, ‘My daughter, I don’t have any objections. He’s a good man, but I’m scared for you. I’m scared for my grandkids because, let me tell you, your kids are going to be Black. And I don’t know if you are ready to raise Black kids in the U.S.,’” Paloma remembers. “At that moment I didn’t understand what he meant.”

In the early 1980s, as Harold and Paloma started their lives together, the news from America spoke to racial divisions. The country was seized by a presidential campaign, in which the actor and former California Gov. Ronald Reagan courted segregationist Southern voters at a Mississippi fairground a few miles from where civil rights workers had been murdered in 1964. In Miami, Black residents protested after an all-white, all-male jury acquitted four white police officers who had beaten an unarmed Black motorcyclist, Arthur McDuffie, to death with their fists and nightclubs. Beaten him “like a dog” McDuffie’s mother, Eula McDuffie, told reporters. Over three days of violent street protests, 18 people died, hundreds were injured, buildings burned and President Jimmy Carter called in the National Guard.

The couple lived in Queens, where Christian was born in 1987, and Harold found work while pursuing medicine. He inspected day care schools for sanitary violations. As he traveled around the city’s streets, he never felt imperiled by the color of his skin. “People said there was racism, but I didn’t see it.” On the few occasions he noticed a police officer or shop security trailing him, he put it out of his mind, trying not to pursue the logic of what had happened. “We never talked about it in the house,” he said. “We were concentrating on achieving whatever goals we had to do.”

He told me, ‘My daughter, I don’t have any objections. He’s a good man, but I’m scared for you. I’m scared for my grandkids because, let me tell you, your kids are going to be Black. And I don’t know if you are ready to raise Black kids in the U.S.’ At that moment I didn’t understand what he meant.

– Paloma Pean

Moving with common purpose, Harold and Paloma went wherever the young doctor could find work. Caguas, Puerto Rico, where Alan was born in 1989; back to New York for Harold’s residency in internal medicine at the Brooklyn Hospital Center; then Fort Pierce, Florida, where Dominique was born in 1991; and eventually to McAllen, Texas. Harold’s brother, Leslie, had established his practice in Harlingen, 20 miles north of the Mexican border. Harold was comforted to have family nearby and Paloma wanted to reach her family in Mexico more easily. Still, the first hospital that recruited Harold offered an uncharitable contract; he had to cover half the costs of running the medical practice while seeing only a few patients.

Harold remembers few, if any, other Black doctors in the area. Paloma was more certain about the dearth of diversity in the medical ranks: “We were among the only Blacks in the [Rio Grande] Valley and the only [primary care] doctor.” Three months into the contract, Paloma, who managed the office’s finances, could see they were losing money. She pressed her husband to renegotiate. When he refused, she went to the hospital herself. “I love the Valley,” she told the administrator, her optimism unimpeachable. “But I came here to work. My husband is a very good doctor and you are not paying what he deserves. If you don’t pay him, we are going to move.” Stunned, the administrator, who was white, agreed to her demands, and Paloma returned triumphant.

Daily life was a blur. The couple worked assiduously at the medical practice, finding allies at the hospital who applauded their diligence and, by Harold’s account, rooted for their success. But race was never far from the surface. When a medical assistant at the office told Paloma that another doctor had asked her repeatedly if she was still working with “the Black doctor,” Paloma fumed. At the medical center’s Christmas party that year, Paloma approached the doctor. “‘Are you so and so, the doctor?’ I said. ‘Well, I’m Paloma Pean, and I’m here just to let you know the name of my husband. My husband is Harold Pean. P-E-A-N. His last name is not Black.’ And I said, ‘Thank you, and nice to meet you.’ He opened his eyes big, and then I left.”

At home, Paloma insisted on a Catholic upbringing, and the family prayed every evening after dinner in three languages (Paloma in Spanish, Harold in French, the boys in English). Harold pushed his three boys in the ways his own parents had. “I was expecting them to be either a doctor or a professional, like my parents expected us to be professionals.”

That was the period in which the three Pean boys — Christian, Alan and Dominique — tried to sort out their Blackness in a place that was almost entirely Hispanic and white. Accustomed to being surrounded by Latinos in Florida and later in McAllen, Paloma recalled her father’s warnings. When the boys started nursery school, they were the only Black babies. “That’s when I thought, I need to start to make them very proud of what they are.”

The questions about skin color came early for Dominique, the youngest brother. His fellow kindergartners watched Paloma, a Latina, drop off her son for school in the mornings, and a cousin, who was Chinese, pick him up after the last bell. (Paloma’s brother had married a Chinese woman.) “They asked me if I was adopted,” Dominique remembers clearly. He told his mother, “I don’t look like you.” Would his father, pretty-please, pick him up at school to show the kids, once and for all that, no, he was not adopted? It was a conclusive victory. “The kids stopped bringing it up. ‘OK, you’re Black!’”

The boys steered in different directions, employing sports, fashion and culture to signal their preferences to the perplexed children of McAllen. “I really identified with my Hispanic side, but when people see me, they see a Black kid,” remembers Dominique. He ventured to look “more Black,” braiding his hair into cornrows and wearing FUBU, a line of clothing that telegraphed Black street pride. Meanwhile, Alan forged a collegiate look. He listened to “corny, white boy music” (Christian’s words) and dressed in Abercrombie & Fitch.

The boys were left to their own to make sense of the off-handed remarks at school and on the football field. You’re Black, you’re supposed to jump farther. Do Black kids have extra muscles in their legs? You sound smart for a Black kid. You sound white. Does anyone know if the Pean brothers have big dicks?

“There was open ignorance back then,” Christian remembers. The boys absorbed and repelled the remarks, protesting vigorously only when the N-word exploded in front of them. One of Alan’s friends on the football team asked him, “What’s up, d…igger?” replacing the N and smirking knowingly. Alan responded, “Why would you even do that?”

It never occurred to Dr. Pean to give his teenage boys “the talk,” the dreaded conversation Black parents initiate to prepare their sons for police encounters. The day Christian came home, blood running down his forehead, Harold argued against pressing charges. “The chief of police was my friend, and I had a lot of police patients,” Harold said. “I would meet white people or Black or Hispanic, and I never thought they would see me differently.”

Where Harold was silent, Paloma was explicit. The history of African Americans amazed her. Dominique remembers his mother saying, “Being Black is beautiful. They came to the United States as slaves, and now they are doctors. That blood runs in you, and you are strong.”

Of all the sons, the oldest boy, Christian, seemed the most curious about exactly what his heritage and his skin color had to do with who he was. Why hadn’t his mother married a Mexican man? Why did other kids want to know if his dark skin rubbed off? Could they touch his hair? At age 6, Christian told his mother a Hispanic girl at school had called him the N-word and his mother a “wetback” as he sat in the cafeteria sipping a Capri Sun.

The racist lexicon of American youth befuddled Paloma. She asked Christian, “What does that mean?” “That word is bad,” he responded.

Christian’s doubts about his father’s faith in American meritocracy emerged early. After he endured racist slurs and other offensive remarks at school, Christian told Harold that he felt he was treated differently “because I’m Black.”

“No, Chief,” his father responded, “hard work gets rewarded. It’s not going to help anybody to get down on your race.”

As mixed-race children, the legitimacy of the Pean brothers’ Blackness trailed them into adulthood. At Georgetown University, Christian found an abundance of Black students for the first time — African Americans and immigrants from Nigeria, Ghana and the Caribbean — and unfamiliar fault lines began to emerge.

“When I was in high school, there was never Black immigrants vs. Black Americans,” Christian said. But in college and later in medical school at Mount Sinai in East Harlem, Christian fielded questions from other Black students about whether scholarships for people of color should be set aside for African Americans descended from slaves, not children of Black immigrants like him.

At the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., Dominique was facing similar questions about his racial camp. When he joined the board of the Student Organization of Latinos, he was asked, “Are you Latino enough?”

“When I’m on the street, people see a Black man. But when I’m with my Black friends, they’re like, Dom, you’re not really Black,” he said. The questions followed them into their personal lives: African American women berating Christian and Dominique for dating women who were not Black.

If the Pean brothers’ Haitian and Mexican roots called into question their rightful membership among African Americans, the police discerned no difference. After graduating from high school in the McAllen suburbs, Alan matriculated to the University of Texas-Austin, a sprawling campus filled almost entirely with white, Hispanic and Asian students. Alan, laid-back and affable, made friends easily. It surprised him then when a security officer trailed him at a store in the mall while he shopped for jeans. “That was the moment when I was like, ‘Oh, I’m Black,” he said.

In August 2015, Alan Pean started the fall semester at the University of Houston where he had transferred to finish his degree in biological sciences. Within days, he began to feel agitated, and his mind slipped into a cinematic delusion in which he believed he was a stunt double for President Barack Obama. At other times, armed assassins chased him.

Alarmed by Alan’s irrational Facebook posts and unable to reach him by phone, Christian called his parents, who were sitting in a darkened McAllen movie theater. He urged them to get to Houston. This was not a drill. In 2009, Alan had spent a week at a hospital for what doctors believed was bipolar disorder.

In the lucid moments between the delusions traversing his psyche, Alan knew he needed medical help. Around midnight, on Aug. 26, 2015, he drove to St. Joseph Medical Center in Houston, swerving erratically and crashing his white Lexus into other cars in the hospital parking lot. As he was hustled into the emergency room on a stretcher, Alan screamed, “I’m manic! I’m manic!”

The following morning, Paloma and Harold flew to Houston and arrived at St. Joseph Medical Center expecting to find sympathetic nurses and doctors eager to aid their troubled son. Both Harold and Christian had placed calls to the emergency department, alerting them to Alan’s mental health history. Instead of finding their son being cared for as a man in the midst of a delusion, Harold and Paloma discovered doctors had not ordered a psychiatric evaluation or prescribed psychiatric medication.

Barred from seeing their son and galled by the hospital’s refusal to provide psychiatric care, Harold and Paloma went to their hotel to try to rent a car so they could take Alan for treatment elsewhere. They were gone for half an hour.

In his hospital room, Alan became more agitated. He believed the oxygen tanks next to his bed controlled a spaceship and that he urgently needed to deactivate a nuclear device using the buttons on his bed. He stripped off his hospital gown and wandered into the hallway naked. A nurse called a “crisis code” and two off-duty Houston police officers, one white and one Latino, charged into Alan’s room. They were unaccompanied by any nurses or doctors, and they closed the door behind them.

The officers would say later that Alan hit one of them and caused a laceration. The first officer fired a stun gun. When the electroshock failed to subdue Alan, according to officers’ statements, the second officer said he feared for his safety and fired a bullet into Alan’s chest, narrowly missing his heart.

Paloma and Harold arrived back at the hospital to find themselves plucked from their ordered lives and hurled into a world in which goodwill and compassion had vanished. Alan was in intensive care with a gunshot wound, and police officers were asking questions about his criminal record. (He had none.) Alan would be detained for attacking the security officers, they were told, and it was now a criminal matter.

Christian flew in from New York, Dominique from Fort Worth, and Uncle Leslie from McAllen. Inconclusive conversations with a hospital administrator strained their patience. “That’s when I was told that we had to have a lawyer to see him,” Leslie said, trembling even as he recounted it nearly six years later.

Paloma was bewildered that her appeals for fairness went unanswered. “I was expecting they would allow me to see my son immediately. I said, ‘My son is a good boy. Let me go and see my kid, please! Please!’” She felt like a ghost, wandering the hospital unstuck in time. Suddenly, the complexions and accents of everyone around her mattered: One police officer was surely white, she thought, the other Hispanic, but maybe born in the U.S.? The nurses were Asian, perhaps Filipino?

Days later, the hospital relented, and nurses led her to a glass window. Alan lay sedated, a tube down his throat, handcuffed to the hospital bed. Paloma’s chest tightened and she felt faint. “I pinched myself, and I said, ‘This cannot be true.’ I screamed to my Lord, ‘Please hold me in your hands.’”

“That’s when I really understood what my father was talking about,” Paloma told me. This, she thought, is how America treats Black men.

Over the next few weeks, it became impossible to unravel what exactly had happened to Alan. Sgt. Steve Murdock, a Houston police investigator, told Christian that Alan had been out of control, picking up chairs, acting like a “Tasmanian devil.” When the hospital eventually allowed the Pean family into Alan’s room, Alan was groggy, his wrists and hands swollen. Standing by his bedside, Uncle Leslie asked Paloma, Harold, Dominique and Christian to hold hands and pray. A week later, Alan was transferred to a psychiatric unit, and his delusions began to lift. A few days later, he was released from the hospital.

It was pouring rain the day the Pean family left Houston. Alan insisted on driving — he always drove on family trips — and his parents and brothers, desperate for a return to normalcy, agreed. Paloma prayed on her rosary in the backseat, nestled next to Christian. Alan drove for 20 minutes until someone suggested they stop and eat. At that moment, Alan turned to his father, “Did I really just drive out of Houston with a bullet wound still in my chest? Pop, I probably shouldn’t be driving.” Dominique drove the last five hours home.

Back in McAllen, neighbors passed on their sympathies, dumbfounded that the Pean’s “well-behaved” middle child, the son of a “respected doctor,” had been shot. Just as Harold years before had sewn up the gash in Christian’s head left by a racially charged fistfight, he and Christian now tended to the piercing pain in Alan’s ribs and changed the dressings of his wound.