#raulsalinas

Photo

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“On 16 September 1971, Mexican Independence Day, Chicano, Puerto Rican, Black, American Indian, and white prisoners fashioned black armbands and declared a strike in the prison factories at Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary. Their action was in protest of the murder of George Jackson, the revolutionary prison intellectual and Field Marshall in the Black Panther Party who was shot in the back on 21 August at Soledad State Prison in California. It was also in active solidarity with the rebellion at Attica state penitentiary in New York that three days prior had come to a violent end when ten guards and 29 inmates were killed at the hands of state police authorized to shoot by the then governor Nelson Rockefeller. Yet the numerous protests across the United States sparked by these incidents were not simply a spontaneous response; many were led by multiracial and multiethnic cadres of inmates – both women and men – who had already been organizing against the prison machine.

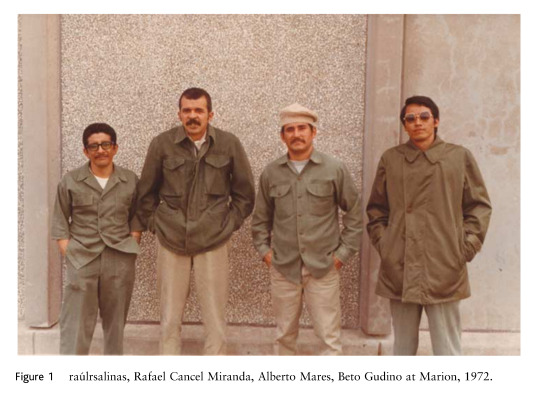

The Leavenworth strike was organized by C.O.R.A (Chicanos Organizados Rebeldes de Aztlán), a political formation of ‘‘all ‘Latinos’ in the Western Hemisphere (in general) and the ‘Chicano’ inhabitants and civilizers of the Northern Land of Aztlán (specifically)’’. Latinos incarcerated at Leavenworth created C.O.R.A. to work through political ideas that were inspiring prison rebellions across the country, as well as social movements across the globe during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Although the members were primarily Chicanos and Mexicanos, C.O.R.A. included Puerto Riquenos, specifically the Puerto Rican Independentistas fighters (Rafael Cancel Miranda, Oscar Collazo, Irving Flores, and Andres Figueroa Cordero). They worked closely with Black Muslims, American Indians, and working-class white inmates, some of whom had been politicized by their involvement in social movements prior to their incarceration or in state jails (Figure 1).

The rebellions at Leavenworth were directed against the violent and racist brutality of guards, inadequate health care, arbitrary punishments and administrative transfers, and the disproportionate numbers of non-whites behind bars. Prisoner organizing created the political culture of an organized social movement around a tradition of writ-writers or jailhouse lawyers and political education strategies that included cultural studies classes, art, poetry, both clandestine and ‘‘sanctioned’’ newspapers that were the medium for critiques of the history of US foreign policy and the role of the criminal justice system in US society.

Grounded in experiences from before and during incarceration, and drawing on the diverse political histories and ideas that were inspiring people across the globe, prison activists organized to change the terms of their incarceration and developed an analysis and critique of the prison system as part of a national/ international matrix of organized violence and white supremacy.‘‘As a logic of social organization’’, and in tandem with foreign military and economic policies, state technologies of racialized colonial violence included the police, courts, prosecutors, jury selection, guards, and the (in)carceral apparatuses of the state. Raulsalinas, poet, activist, and editor of the Leavenworth prison newspaper Aztlán, described the conditions of incarceration for US minorities as a ‘‘backyard form of colonialism.’’

As activist-scholar Dylan Rodriquez writes, the repression against ‘‘US-based Third World liberation movements during and beyond the 1960s and 1970s forged a peculiar intersection between official and illicit forms of state and state-sanctioned violence. Policing, carceral, and punitive technologies were invented, developed, and refined at scales from the local to the national, encompassing a wide variety of organizing and deployment strategies.’’ Legal battles waged in the state and federal court systems by radical lawyers were buttressed by strikes, riots, petition demands, and the creation and transformation of educational spaces, as well as the support of family members and active citizens. Prison activists across the country deployed the political language of civil and human rights, developed an international political consciousness grounded in ideas of multiracial solidarities and human dignity, and explicitly linked their own struggles inside the ‘‘prisons of empire’’ to progressive and national liberation movements in the United States, the hemisphere, and across the globe. On a national level, these combined movements questioned the legality and legitimacy of the prison system as part of the larger coercive apparatuses of ‘‘law and order’’ politics. Perhaps most significantly, these struggles were part of a longer history of self-defense against the violation of civil and human rights by police departments, racist jury systems, prison administrators, and guards, as well as by citizens defending white supremacy in the United States.

The rebellions were part of the larger circulation of progressive struggles in the post-WWII period. In the context of open repression against activists in the United States, particularly the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Counter Intelligence Programs (COINTELPRO), and Cold War geopolitics in Latin America, Africa, and Asia, social movements in the United States expanded their international connections during the 1960s. Inspired by anti-colonial and national liberation efforts in Algeria, Cuba, and Vietnam, as well as American Indian struggles for the sovereignty of the ‘‘First Nations,’’ many political and cultural organizations in the United States articulated a politics situated in what they defined as a shared experience of US colonialism. By the late 1960s as antiVietnam War demonstrations escalated and the passage of civil rights laws did not necessarily translate into a change in material conditions, the anti-war, women’s, gay liberation, and Black, Brown, Yellow, and Red Power movements overlapped at the local, national, and international level. What I offer in looking behind prison walls is one element of a ‘‘history of histories’’ made up of global progressive, ‘‘experimental civil rights’’ and anti-colonial struggles.”

- Alan Eladio Gómez, ‘‘‘Neustras Vidas Corren Casi Paralelas’: Chicanos, Independentistas, and the Prison Rebellions in Leavenworth, 1969–1972,” Latino Studies 6 (2008), pp. 65-67.

#leavenworth penitentiary#united states penitentiary marion#prison strike#prisoner revolt#independentistas#chicanos organizados rebeldes de aztlán#chicano#chicano movement#american prison system#american politics#u.s. history#mass incarceration#white supremacy#anti-colonialism#puerto riquenos#third worldism#prison riot#prison riots#causes of prison riots#crime and punishment#history of crime and punishment#academic research#academic quote#prisoners' movement

29 notes

·

View notes