#reintervention

Text

Good morning Skippy-

Thank you all who are praying for Lilly. The words below are from Lilly’s mom❤️:

They just took Lilly back to the OR. The hardest thing I’ve ever done. She was strong but we both cried. My heart is breaking for her but I know she will be okay. I probably won’t hear anything for a couple hours...

Hi Skippy this update is from 9:30 CDT from Lilly’s mom:

Full of hope and encouragement. Thanks for the prayers, praising God!!

Just talked to the doctor . The amputation is complete & everything went well. Dr. now will do the Targeted Nerve Reintervention which will last til about 11am. She said Lilly is totally stable & all went well. I rested a bit & think I’ll go find a cup of coffee.

Dr. said Lilly made the right decision & will be able to do anything. ❤️🙏🏼❤️🙏🏼

Lilly has got this! Continued prayers for her healing. We pray God heals her quickly and completely. May angels surround her and her mom.🙏🏻❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pro-Healing Cardiac Stents with Stem Cell Capture Technology

Sarah Hindle

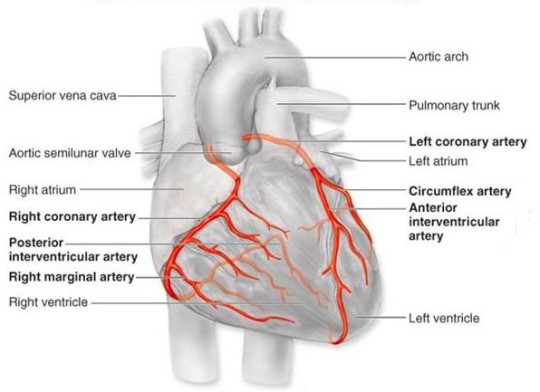

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide. The World Health Organisation reported in 2015 that 17.7 million people died from CVD - 42% of these deaths were attributed to coronary heart disease (CHD). The coronary arteries supply blood to the heart muscle and CHD is the narrowing or blockage of these arteries due to the gradual formation of plaque within the artery walls.

Source: http://tube.medchrome.com/2011/04/coronary-circulation-anatomy.html

Surgical intervention is often required and one approach uses short wire mesh tubes, called stents. These stents are placed in to the narrowed or blocked section permanently and act as a scaffold to keep the artery open.

Source: https://www.quora.com/Can-a-artery-stent-be-blocked-again-And-can-another-stent-be-put-in-the-same-place

Although the use of these stents has been a significant breakthrough in the treatment of CHD there are various limitations including impaired healing of the endothelium. The endothelium describes the monolayer of endothelial cells that line the interior surface of the blood vessels. This impaired healing can lead to in-stent restenosis (a re-narrowing of a blood vessel leading to restricted blood flow), thrombogenicity (clotting) and inflammation. Ultimately, this results in a recurrence of symptoms and surgical reintervention.

Source: http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/S/stent.html

The ability of the endothelium to repair itself depends on both the migration of surrounding mature endothelial cells, and the attraction and adhesion of circulating stem cells (endothelial progenitor cells, EPCs) from the blood to the injured region.

A novel ‘pro healing’ approach, using biomaterial surfaces with tuneable surface topography and chemistry, has been proposed to facilitate endothelial repair after stent implantation. Immobilised biomolecules, including antibodies and peptides, on these surfaces are capable of targeting specific surface molecules of EPCs. This would result in the attraction, adhesion, proliferation and differentiation of the EPCs at the site of the stent implantation and ultimately promote the regeneration of a healthy and functional endothelium.

#Cardiovascular disease#coronary heart disease#stent#biomaterials#regenerative medicine#stem cell research#stem cell treatment

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bleeding Post Thyroidectomy

The incidence of symptomatic hemorrhage:Requiring reintervention amounts to 0.1% to 1.5%Post-operative bleeding will characteristically be prefaced by:Respiratory distressPainCervical pressureDysphagiaIncreased blood drainageNo specific perioperative risk factors:That would allow identification of the high-risk patient population for this potentially lethal…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Biomed Grid | Cost Comparison of Peri-Strips Dry®/Peri-Strips Dry with Veritas® (PSD/PSD-V) Versus Seamguard® in Gastric Staple Line Reinforcement (SLR)

IntroductionIncreasing need for primary bariatric/metabolic surgery in Latin America

The prevalence of morbid obesity (body mass index (BMI) >=40 kg/m²) is highest among men and women in high-income western countries (men=3.3%; women=5.7%) [1]. Low- and middle-income countries such as those in Latin America have lower prevalence, but the rate of morbid obesity among adults is increasing rapidly [1]. In the last decade (2007-2016), prevalence of morbid obesity among adult men and women in Latin America has approximately doubled (2.1 and 1.5 times) to 1.2% and 3.2%, respectively [1].

Bariatric surgery is indicated to manage morbid obesity, severe obesity (BMI=35-39.9 kg/m2) with obesity-related comorbidities, and obesity (30-34.9 kg/m2) with difficult to control comorbidities [2]. The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) has favorably compared the most common bariatric surgery procedures – Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (gold standard) and sleeve gastrectomy – for management of weight and comorbidities [3]. Sleeve gastrectomy has overtaken Roux-en-Y gastric bypass as the most common primary bariatric/metabolic procedure worldwide [4]. However, the most common surgery type in many Latin American countries continues to be Roux-en-Y gastric bypass by a wide margin [5].

High cost of staple line complications (SLC)

According to the annual report on outcomes after bariatric surgery published by the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO), most primary bariatric/metabolic procedures are conducted laparoscopically worldwide (99.3%) with a good safety profile [5]. However, staple line complications (SLC), such as hemorrhage (weighted average across procedures=2.76%) and leak (weighted average across procedures=2.46%) may be severe [6]. Multiple studies have examined the healthcare resource utilization and expenditures associated with the correction of hemorrhages and leaks after primary bariatric surgery with an average cost of leaks after sleeve gastrectomy between US$22,014-$93,451[7-10]. The largest contributors of expense included room and board on the ward and intensive care unit (ICU) (The Netherlands: 82%; US: 44%), therapeutic measures such as reintervention (The Netherlands: 11%; US: 24%), and diagnostic measures such as imaging (The Netherlands: 8%; US: 14%) [7, 8].

Reduce SLC using Peri-Strips Dry with Veritas (PSD-V) for staple line reinforcement (SLR)

Staple line reinforcement (SLR) is the reinforcing or buttressing of the gastric staple line with the goal of reducing SLC following primary bariatric/metabolic surgery. There is no standard of care (SOC) for gastric SLR [11]. In fact, during many primary bariatric/ metabolic surgeries no SLR is administered, likely due to perceived cost [6]. To fill this gap in care, multiple products and methods have been deployed for SLR. Peri-Strips Dry® with Veritas® Collagen Matrix (PSD-V; Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL) is prepared from dehydrated bovine pericardium procured from cattle under 30 months of age in the United States [12]. PSD-V was preceded by Peri-Strips Dry® Bovine Pericardium Strips (PSD; Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL) [13]. Seamguard (W.L. Gore & Associates, Inc, Flagstaff, AZ) is another commonly used buttressing option made from synthetic biocompatible glycolide copolymer [14]. Another method of gastric SLR is oversewing of the suture line; however, this is associated with increased OR time.

The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) database of bariatric surgeries shows low rates (<1%) of leaks and bleeds for both sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in the US [3]. A recent meta-analysis by Shikora et al. (2015) based on 253 studies covering 66,727 unique patients favorably compared PSD/PSD-V to Seamguard, oversewing, and no SLR for primary gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy surgeries [6]. Overall, the use of PSD/PSD-V for gastric SLR was associated with a significant reduction in SLC including both leaks and bleeds after both gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy [6]. The aim of this study is to apply costs to those results and assess the impact of SLR choice on costs and outcomes of primary gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy from the hospital administrator perspective in the US, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico.

Materials-and-Methods

A cost-consequence model was developed to compare the cost impact associated with using PSD/PSD-V for SLR in primary bariatric/metabolic surgery as compared to other SLR methods including Seamguard, oversewing, and no reinforcement. Costs from the hospital administrator perspective include the difference in the distribution of surgeries, rates of SLC including leaks and bleeds, surgery time, and product costs. Four countries were selected based on geographic region (Americas) and availability of country-specific data: the US, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico. Epidemiologic, clinical, and cost inputs are shown in Table 1 (by SLR method) and Table 2 (by country).

Table 1:Model inputs by SLR method

Abbreviations: PSD/PSD-V: Peri-Strips Dry/Peri-Strips Dry with Veritas; SLR: Suture Line Reinforcement

Table 2:Model inputs by country.

Abbreviations: COL$, Colombian Pesos; Mex$, Mexican Pesos; PSD/PSD-V, Peri-Strips Dry/Peri-Strips Dry with Veritas; R$, Brazilian Reals; US$, United States dollars.

Epidemiologic Inputs

Country-specific rates of gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy are from the international survey of primary bariatric/metabolic performed annually by IFSO [15]. The rates of gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy data for Brazil were supplemented with a report by the Brazilian Ministry of Health [16]. The rates of gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy data for the US were supplemented with data from US databases [17,18]. The proportions of procedures using each type of SLR – PSD/PSD-V, Seamguard, oversewing, and no SLR – are from the meta-analysis by Shikora et al. (2015) [6] for Latin American countries with supplemental information from US databases for the US [17-19]. As bariatric surgical centers are often specialized, annual outcomes are reported based on a high-volume hospital performing 100 surgeries per year [20,21].

Clinical Inputs

The rate of SLC including leaks & bleed following gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy by SLR method are from the meta-analysis by Shikora et al. (2015) [6] for Latin American countries with supplemental information from US databases for the US [17-19]. The number of firings per procedure for PSD-V and Seamguard were calculated from the Premier US Data Base 2017 [22]. The supplies for oversewing are based on supplies for the diagnosis related groups (DRG) for sleeve gastrectomy with complications (DRG=619) and gastric bypass with complications (DRG=620) from the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) 2018 [23,24]. Operating room time for gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy by SLR method were taken from the literature [25-27]. Because the length of surgery for gastric bypass with oversewing SLR could not be identified, the same percentage increase (24%) in the length of surgery for sleeve gastrectomy with oversewing versus with no SLR was applied [26].

Cost Inputs

Product Costs: Given lack of visibility to product costs in each country, costs for PSD-V and Seamguard are based on the US average sales price (ASP) in 2018 [28]. Product and all other costs were exchanged and inflated to 2018 currency using the exchange rates and country-specific consumer price index (CPI) published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) [29,30].

Cost of Complications: The associated cost of a SLC (leak or bleed) was applied to the specific surgery type. For bleed complications, the additional cost of a blood bank event (6 units) was added [31]. Costs of complications following sleeve gastrectomy for Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and the US were calculated based on DRG 619 from the Mexican Social Security Institute Inpatient Hospital DRG’s Book (IMSS) 2016 including sutures (34 units), hospital length of stay (LOS; 12 days), and ICU LOS (4 days) [23]. Costs of complications following gastric bypass for Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and the US were calculated based on DRG 620 from the IMSS 2016 including sutures (24 units), hospital LOS (24.5 days), and ICU LOS (8 days) [24]. Costs of hospital and ICU room and board are all country specific.

Cost of Operating Room Time: Cost of operating room (OR) time per hour for Brazil, Colombia and Mexico is based on IMSS 2017 [32]. Whereas, cost of US OR time was calculated based on national average of OR cost per minute across five surgical procedures (laparoscopic prostatectomy, myringotomy with insertion of tube, laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair, bilateral reduction mammoplasty, and knee arthroscopy) and surgical specialties from a university hospital perspective [33].

Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analyses were conducted for both annual net cost impact results and net cost impact results per procedure. Oneway sensitivity analyses used the 95% confidence intervals or +/- 20% when the confidence interval was not available. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses (PSA) using Monte Carlo simulation for 5000 iterations evaluated key drivers of costs. The distribution of SLR use by procedure type was varied jointly. Distributions of variables for the PSA are included in the Appendix. The 95% confidence interval (CI) is reported for net annual cost impact and cost impact per procedure from the PSA results.

ResultsResults

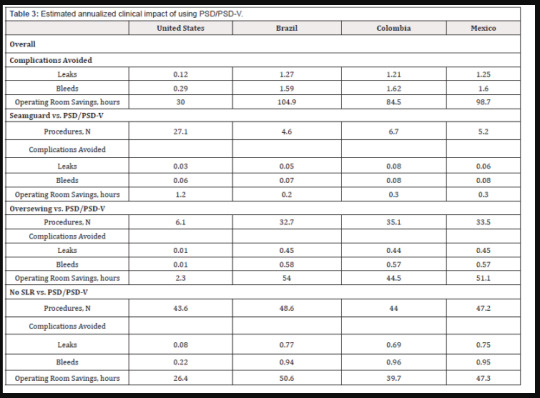

Overall: For hospitals conducting 100 primary bariatric/ metabolic procedures annually, the model estimated avoidance of approximately 3 complications and a reduction in hours of surgical time (71 US; 105 Brazil; 84 Colombia, 99 Mexico) (Table 3) by using PSD/PSD-V in all surgeries. Net annual cost savings from hospital resource utilization would be US$27,537 (95% CI=US$6,572- US$51,509), R$152,399 (95% CI=R$66,764-R$253,925), COL$139.81 million (95% CI=COL$72.48 million-COL$220.95 million), and Mex$1,854,032 (95% CI=Mex$1,256,153- Mex$2,560,758) (Figure 1).

Table 3: Estimated annualized clinical impact of using PSD/PSD-V.

Abbreviations: PSD/PSD-V: Peri-Strips Dry/Peri-Strips Dry with Veritas

(Figure 2) shows the influence of cost drivers on the overall annual net cost savings. The top five cost drivers across countries (listed by aggregate rank) included the cost per firing of PSD/ PSD-V (US: 1; Brazil: 2; Colombia: 1; Mexico: 2), the proportion of gastric bypass procedures (US: rank=2; Brazil: rank=1; Colombia: 4; Mexico: 6), the annual number of bariatric/metabolic procedures (US: 7; Brazil: 4; Colombia: 2; Mexico: 1), the number of firings of PSD/PSD-V during gastric bypass (US: 8; Brazil: 3; Colombia: 3; Mexico: 3), and the OR time difference in gastric bypass surgery with no SLR (US: 3; Brazil: 6; Colombia: 6; Mexico: 5).

Figure 1: Estimated annualized impact of using PSD/PSD-V

Figure 2: Estimated annualized impact of using PSD/PSD-V - One Way Sensitivity Analysis - Tornado Diagram

Seamguard vs. PSD/PSD-V: Based on the distributions of primary bariatric/metabolic procedures and SLR choice for those procedures, the estimated number of annual primary bariatric/ metabolic procedures performed using Seamguard for SLR would be 27, 5, 7, and 5 per 100 bariatric/metabolic surgeries in the US, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico, respectively. Switching from Seamguard to PSD/PSD-V only represents 1-9% of the overall annual net cost impact.

Per procedure, switching to PSD/PSD-V from Seamguard could provide net savings of US$95 (95% CI=-US$186-US$376) and Mex$8,382 (95% CI=Mex$3,762-Mex$12,913). In Brazil and Colombia, the net impact of switching to PSD/PSD-V from Seamguard is not significantly different than zero (-R$207, 95% CI=-R$985-R$567; COL$0.51 million, 95% CI=-COL$0.27 million- COL$1.29 million). Although the use of Seamguard is associated with fewer firings per procedure, the costs savings from using PSD/ PSD-V vs. Seamguard from reduced complications and OR time are greater than or approximately equivalent to the increase in product acquisition costs (Figure 1).

Influence of cost drivers per procedure savings from PSD/ PSD-V vs Seamguard were identified across countries (Figure 3). Top five cost drivers across countries (listed by aggregate rank) included the following: cost per firing of PSD/PSD-V (US: rank=1; Brazil: 2; Colombia: 1; Mexico: 2), the cost per firing of Seamguard (US: 2; Brazil: 3; Colombia: 2; Mexico: 3), the number of firings of PSD/PSD-V during gastric bypass (US: 5; Brazil: 4; Colombia: 5; Mexico: 4), the number of firings of Seamguard during sleeve gastrectomy (US: 3; Brazil: 7; Colombia: 3; Mexico: 5), and the number of firings of PSD/PSD-V during sleeve gastrectomy (US: 4; Brazil: 8; Colombia: 4; Mexico: 6).

Figure 3: Estimated impact of using Seamguard vs. PSD/PSD-V per procedure - One Way Sensitivity Analysis - Tornado Diagram

Oversewing vs. PSD/PSD-V: Based on the distributions of primary bariatric/metabolic procedures and SLR choice for those procedures, the estimated number of annual primary bariatric/ metabolic procedures performed using oversewing for SLR would be 6, 33, 35, and 33 per 100 bariatric/metabolic surgeries in the US, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico, respectively. Switching from oversewing to PSD/PSD-V represents over half (52-76%) of the overall annual net cost impact in Latin American countries.

Higher product acquisition costs associated with PSD/PSD-V vs. oversewing are less than the cost savings associated with reduced complications and OR time (Figure 1). Per procedure, switching to PSD/PSD-V from oversewing could provide net savings of US$98 (95% CI=-US$188-US$391), R$3,558 (95% CI=R$2,199-R$5,047), COL$2.42 million (95% CI=COL$1.47 million-COL$3.51 million), Mex$28,700 (95% CI=Mex$21,592 -Mex$37,049).

The top five cost drivers of the per procedure savings from PSD/PSD-V vs. oversewing (listed by aggregate rank) included the cost per firing of PSD/PSD-V (US: rank=3; Brazil: 3; Colombia: 2; Mexico: 2), the OR time difference in gastric bypass surgery for oversewing (US: 7; Brazil: 2; Colombia: 1; Mexico: 1), the proportion of gastric bypass procedures (US: 5; Brazil: 1; Colombia: 3; Mexico: 3), the number of firings of PSD/PSD-V during gastric bypass (US: 9; Brazil: 4; Colombia: 4; Mexico: 4), and the number of firings of PSD/PSD-V during sleeve gastrectomy (US: 4; Brazil: 6; Colombia: 5; Mexico: 8) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Estimated impact of using Oversewing vs. PSD/PSD-V per procedure - One Way Sensitivity Analysis - Tornado Diagram

No SLR vs. PSD/PSD-V: No utilization of SLR in primary bariatric/ metabolic procedures performed is estimated to be 44, 49, 44, and 47 per 100 annual procedures in the US, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico, respectively. Switching to PSD/PSD-V from no SLR is associated with the highest reductions in annual complications (US: 0.3, 73%; Brazil: 1.7, 60%; Colombia: 1.7, 59%; Mexico: 1.7, 60%;). Implementation of PSD/PSD-V vs. no SLR represents cost savings of approximately 24%-89% of the overall annual net cost impact.

While there is a higher product acquisition cost associated with PSD/PSDV vs no SLR, it is less than or approximately equivalent to the cost savings associated with reduction in complications and OR time (Figure 1).

Implementation of PSD/PSDV vs no SLR could provide net savings per procedure of US$559 (95% CI=US$212-US$949), COL$1.17 million (95% CI=COL$0.42 million-COL$1.98 million), and Mex$18,009 (95% CI=Mex$12,145 -Mex$24,311). In Brazil, the net impact of switching to PSD/PSD-V from no SLR is not significantly different than zero (R$758, 95% CI=-R$197-R$1,775).

Figure 5 shows the influence of cost drivers on the per procedure savings from PSD/PSD-V vs. no SLR. The top five drivers of cost (listed by aggregate rank) included the OR time difference in gastric bypass surgery for no SLR (US: rank=1; Brazil: 1; Colombia: 2; Mexico: 1), the cost per firing of PSD/PSD-V (US: 4; Brazil: 2; Colombia: 1; Mexico: 2), the number of firings of PSD/PSD-V during gastric bypass (US: 7; Brazil: 3; Colombia: 3; Mexico: 3), the distribution of SLR choice in sleeve gastrectomy surgery (US: 2; Brazil: 5; Colombia: 4; Mexico: 6), and the proportion of gastric bypass procedures (US: 3; Brazil: 4; Colombia: 5; Mexico: 7).

Figure 5:Estimated impact of using No SLR vs. PSD/PSD-V per procedure - One Way Sensitivity Analysis - Tornado Diagram.

Discussion

Per Procedure Cost Impact of Choosing PSD/PSD-V for Gastric SLR: Per procedure, the largest cost savings in Latin American countries come from switching to PSD/PSD-V from oversewing due primarily to the long OR time associated with the oversewing method of SLR (US$98, 95% CI= -US$188-US$391; R$3,558, 95% CI=R$2,199-R$5,047; COL$2.42 million, 95% CI=COL$1.47 million- COL$3.51 million; Mex$28,700, 95% CI=Mex$21,592-Mex$37,049) (Table 4).

Table 4:Estimated annualized economic impact of using PSD/PSD-V.

Abbreviations: COL$, Colombian Pesos; Mex$, Mexican Pesos; PSD/PSD-V, Peri-Strips Dry/Peri-Strips Dry with Veritas; R$, Brazilian Reals; US$, United States dollars.

Using no SLR during gastric surgery leads to the highest rates of SLC and potential per procedure cost savings of PSD/ PSD-V in the US, Colombia, and Mexico despite higher product acquisition costs (US$559, 95% CI=US$212-US$949; R$758, 95% CI=-R$197-R$1,775; COL$1.17 million, 95% CI=COL$0.42 million- COL$1.98 million; Mex$18,009, 95% CI=Mex$12,145-Mex$24,311)

PSD/PSD-V provides cost savings over Seamguard in the US and Mexico despite similar product costs and OR time due to a significant reduction in SLC (US$95, 95% CI=-US$186-US$376; -R$207, 95% CI=-R$985-R$567; COL$0.51 million, 95% CI=-COL$0.27 million- COL$1.29 million; Mex$8,382, 95% CI=Mex$3,762-Mex$12,913).

Clinical Impact of Choosing PSD/PSD-V for Gastric SLR: In addition to a cost impact by utilizing PSD/PSD-V across all primary bariatric procedures, the number of complications would decrease by approximately 0.4, 2.9, 2.8, and 2.8 complications per 100 procedures in the US, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico, respectively.

Therefore, the use of PSD/PSD-V across all primary bariatric procedures is a dominant strategy (fewer complications, lower cost). Although the cost impact per procedure is not always significantly greater than zero (not favoring PSD/PSD-V), there is a cost effectiveness argument that could be developed based on the net cost impact and number of complications avoided.

Annual Cost Impact of Choosing PSD/PSD-V for Gastric SLR: The net annual cost savings of switching to PSD/PSD-V from other gastric SLR methods for a hospital performing 100 primary bariatric/metabolic procedures annually would be US$27,537 (95% CI=US$6,572-US$51,509), R$152,399 (95% CI=R$66,764-R$253,925), COL$139.81 million (95% CI=COL$72.48 million-COL$220.95 million), and Mex$1,854,032 (95% CI=Mex$1,256,153-Mex$2,560,758). These results are robust given that the lower bound of the 95% confidence interval in each country still shows cost savings across 5000 iterations.

Limitations: In the case of the distribution of SLR methods across procedures, country-specific inputs were not available. Variability in this input was allowed in both the one-way sensitivity analysis and PSA, but the relative influence of annual net cost savings from primary bariatric/metabolic procedures was not large. Only the US distribution of SLR use for gastric bypass was a top-5 influencer of annual net cost savings for primary metabolic procedures. Based on our modelled results, more gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy procedures being performed without SLR or using the Seamguard and oversewing methods would lead to greater benefit of PSD/PSD-V in terms of patient outcomes and a low to positive cost impact in favor of PSD/PSD-V.

Additionally, given lack of data, US product costs for PSD/PSD-V, Seamguard and oversewing were converted to local currencies and used as a proxy for Brazil, Colombia and Mexico. The costs of PSD/ PSD-V and Seamguard were both influential in sensitivity analysis. In the US, these costs per firing for these products are roughly equivalent. Therefore, a hospital administrator is acquiring both products for different prices, the results of this research may not hold ( Appendix 1-3.).

Conclusion

A high volume hospital preforming 100 primary bariatric/ metabolic procedures per year could potentially realize cost savings of US$27,537 (95% CI=US$6,572-US$51,509), R$152,399 (95% CI=R$66,764-R$253,925), COL$139.81 million (95% CI=COL$72.48 million-COL$220.95 million), and Mex$1,854,032 (95% CI=Mex$1,256,153-Mex$2,560,758) and in the US, Brazil, Colombia, and, Mexico, respectively, by using PSD/PSD-V rather than other SLR choices. Despite the acquisition cost of PSD/PSD-V, SLR using PSD/PSD-V demonstrates cost savings associated with reductions in complications (i.e., leaks and bleeds) and OR time.

Read More About this Article: https://biomedgrid.com/fulltext/volume6/cost-comparison-of-peri-strips-dry%C2%AE-peri-strips-dry-with-veritas.000998.php

For more about: Journals on Biomedical Science :Biomed Grid | Current Issue

#biomedgrid#american journal of biomedical science & research#journals on medical microbiology#journals on cancer medicine

0 notes

Text

Dear Lilly update

Hi Skippy this update is from 9:30 CDT from Lilly’s mom:

Full of hope and encouragement. Thanks for the prayers, praising God!!

Just talked to the doctor . The amputation is complete & everything went well. Dr. now will do the Targeted Nerve Reintervention which will last til about 11am. She said Lilly is totally stable & all went well. I rested a bit & think I’ll go find a cup of coffee.

Dr. said Lilly made the right decision & will be able to do anything. ❤️🙏🏼❤️🙏🏼

Thank you so much for letting us know....prayers ongoing for her healing, for strength for the family, and of course sending them all love, hugs and prayers...🙏🏻❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Juniper Publishers- Open Access Journal of Case Studies

Reoperative Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting: Review of Changing Pattern and Outcomes

Authored by Kamal S Ayyat

Abstract

Reoperative coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) prevalence had markedly changed over the last decades. This change had been also noticed in patients’ risk profile and outcomes. The aim of this review is to highlight large multi- and single-center studies investigating the change in pattern, techniques, and outcomes of reoperative CABG globally. It is meant to be a reference that can help cardiac surgeons for a better understanding of our current situation with this challenging operation.

Keywords: Reoperation; Redo; Coronary artery bypass grafting; CABG; Coronary artery diseases

Abbreviations: CABG: Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting; IABP: Intra-Aortic Balloon Pump; PTCA: Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty; STS: Society of Thoracic Surgeons; ITA: Internal Thoracic Artery; LAD: Left Anterior Descending Artery; ASCTS: Australasian Society of Cardiac and Thoracic Surgeons

Introduction

Since coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery was introduced for clinical practice in the 1960s, it has demonstrated its efficiency to improve symptoms and prognosis in patients with the advanced coronary atherosclerotic disease [1]. As CABG patients are getting older and living longer, reoperative CABG surgery has become an integrative part of the cardio-surgical daily practice presenting significant challenges in technical and decision-making aspects [2].

A number of improvements have been made in the pre-, intra-, and postoperative management of reoperative CABG patients over the last decades. These improvements have included technological developments as well as the increased experience of the teams treating these patients (cardiology, anesthesia, intensive care, and surgical teams). Preoperative imaging with computed tomography is one of the most important preoperative improvements that has helped much with operative planning [3]. Also, the use of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography has facilitated placement of retrograde cardioplegia, peripheral cannulation and intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) [4]. However, the effect of all these improvements on the outcomes of reoperative CABG is masked by the change in the risk profile of the patients. Although the prevalence of reoperative CABG has decreased, the risk profiles of the patients have increased [5-7].

Materials and Methods

Search strategy and study selection

A systematic literature search was performed through PubMed for studies published on outcomes of reoperative CABG. Keywords used in the search included MeSH terms: reoperative coronary artery bypass grafting, incidence, patient characteristics, trend, pattern, and outcome.

The “related articles” function was used to broaden the search and all abstracts, studies, and citations scanned were reviewed. The reference lists of articles found through these searches were also reviewed for relevant articles.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were: addressing reoperative CABG incidence, patient characteristics, and outcomes. Only the studies with a number of reoperative CABG patients more than 100 patients were included. However, studies comparing deferent techniques of reoperative CABG like: off-pump versus on-pump, or thoracotomy versus resternotomy were excluded. In this review, we present both multi- and single-center studies on trends and outcomes of reoperative CABG (Table 1).

Results

Incidence

Coronary reintervention after CABG has been common over the last decades. Sabik et al. [8] actively followed up 26 927 primary CABG patients at Cleveland Clinic. They found that patients’ freedom from reintervention was 73%, 60%, and 46% at 15, 20, and 25 years after the first operation respectively. This means that more than half of primary CABG patients will have coronary reintervention if they lived for 25 years after the operation [8]. In order to adjust potential long-term benefits of CABG for attrition by death, Blackstone and Lytle examined the outcome of primary CABG patients at Cleveland Clinic also in light of three competing time-related events: death, reoperation, and percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA). Their 12 years follow-up showed 58.6% of the patients were alive and without reintervention, while 26.6% were dead, 8.1% had PTCA, and 6.8% had reoperative CABG [9]. In van Domburg et al. [10] 30-year follow-up study of 1041 primary venous CABG, coronary reinterventions were performed in 36% of the patients. 29.6% had reoperative CABG and 14.2% had PTCA. However, reintervention after 20 years was only PTCA [10].

Older studies showed increase in prevalence of reoperative CABG like Lytle et al. [11] study that mentioned marked increase in incidence of reopertaive CABG compared with previous cohorts (436 patients from 1967 to 1978, 439 patients from 1979 to 1981, 625 patients from 1982 to 1984, 1009 patients from 1985 to 1987, and 1663 patients from 1988 to 1991) [11]. The largest single-center study on reoperative CABG was done by Sabik et al. [12] at Cleveland Clinic from 1990 to 2003 including 4,518 reoperations. Although the change in incidence of reoperative CABG was not mentioned in the study, one can notice from their presented tables that the number of reoperative CABG had decreased from around 500 in 1990 to around 200 in 2002 [12].

In contemporary studies; Ghanta et al. [5] used the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) Adult Cardiac Surgery Database from 2000 to 2009 to analyze characteristics and postoperative outcomes of 72,322 isolated reoperative CABG patients from 1035 institutions. The percentage of reoperative to overall CABG volume decreased from 6.0% in 2000 to 3.4% in 2009 [5]. Also, Spiliotopoulos et al. [7] in Toronto General Hospital institution had done the most recent largest single-center study of changing pattern of reoperative CABG, including 1204 reoperative CABG patients from 1990 to 2009. The results showed that the prevalence of reoperative CABG had drastically decreased from 7.2% (1990 to 1994) to 2.2% (2005 to 2009) [7].

The decrease in the prevalence of reoperative CABG even with the large number of patients who had previous CABG can be attributed to multiple factors. The marked increase in the prevalence of previously performed PCTA on the native arteries or the grafts of reoperated on patients provides an obvious explanation for this downward trend of reoperative CABG [7]. Other factors that might have led to higher patients’ freedom from reintervention include: improved surgical technique during primary operation using internal thoracic artery (ITA) to the left anterior descending artery (LAD) as a standard strategy, more effective risk factor control, and optimal medical therapy with statins and antiplatelet medications [13,14].

Patient characteristics

The characteristics of reoperative CABG patients usually show older age, more comorbidities, and worse presentation compared to primary CABG patients, that was shown in Ghanta’s study of STS database. On the other hand, comparing the characteristics of reoperative CABG patients in 2009 with 2000 showed no significant change in age or gender. However, comorbidities like diabetes, hypertension, renal failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypercholesterolemia, and cerebrovascular disease were more prevalent in 2009 than in 2000. Also, patients in 2009 had a worse presentation like congestive heart failure, left main disease, and myocardial infarction [5]. Spiliotopoulos et al. [7] showed in their study the deterioration in the preoperative risk profile of reoperative CABG patients over the years from 1990 to 2009. As the patients during the second decade had been significantly older, with larger body surface area, and with a higher incidence of diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. Moreover, preoperative atrial fibrillation, cerebrovascular accidents, left main stenosis, and peripheral vascular disease had been significantly more frequent. On the other hand, the mean interval between the first operation and the redo one had significantly increased in the second decade [7].

Another multicenter study of reoperative CABG was done by Yap et al. [15] using the Australasian Society of Cardiac and Thoracic Surgeons (ASCTS) Cardiac Surgery Database. The study included isolated CABG patients from 2001 to 2008. 458 patients underwent reoperative CABG. The risk profile of reoperative patients was significantly worse than primary patients due to a higher prevalence of elderly patients, patients with unstable angina, peripheral vascular disease, higher New York Heart Association class, worse left ventricular function, previous myocardial infarction, complete heart block, and more emergency operations. Similar results were shown in Sabik’s et al. [12] study at the Cleveland Clinic [12,15].

Van Eck et al. [16] studied the change in profiles of 582 reoperative CABG patients from 1987 to 2000 in Netherlands. They divided the patients into three groups according to the date of the operation. Patients of the latest group showed a significant increase in mean age, kidney disease, and previous PTCA. Also, the time period between both operations had increased significantly, as well as, the number of patients with patent IMA graft [16].

Outcomes

Comparing outcomes in Ghanta’s [5] study, postoperative observed mortality for reoperative CABG decreased from 6.1% in 2000 to 4.6% in 2009. But, it remained almost 2.5 times the mortality for primary CABG. This study was limited to STS Adult Cardiac Surgery Database information which captured neither the conduits used in the previous operation nor the interval between it and the current operation. STS database represents 1035 participating institutions with different protocols, teams, and experience. Also, using observed, predicted, and adjusted mortality in comparing the outcomes of reoperative and primary CABG in 2000 and in 2009 might not be enough to avoid the problem of comparing apples and oranges as those patients had different risk profiles. Using propensity scoring and comparing matched pairs instead might have been a more valid comparison [5,17]. In Yap’s study, operative mortality for reoperative CABG was 4.8%. While, operative mortality for primary CABG was 1.8%. Using logistic regression model and after adjustment for differences in patient variables, reoperative CABG status remained a predictor of operative mortality [15].

In single-center studies, Spiliotopoulos et al. [7] showed in their study that comparing propensity-matched reoperative patients from 1990 to 1999 and from 2000 to 2009 did not show a significant change in operative mortality. However, the mean hospital length of stay had been significantly reduced. Also, their multivariate analysis of risk factors revealed preoperative shock, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, and age as independent predictors of operative mortality [7]. Another study was done by Colkesen et al. [18] in Adana, Turkey. They compared redo cardiac surgery procedures in general with primary ones including CABG and valve surgeries. They had 109 redo cardiac surgery patients between 2010 and 2014. Hospital mortality of redo patients was 4.6%, while it was 2.2% for primary cardiac surgery patients [18]. Also, Di Mauro et al. [19] analyzed early and late outcomes of reoperative CABG between 1994 and 2001. Applying the propensity score, they matched 239 redo patients with 239 primary CABG patients. Early mortality was 4.2% for the redo group and 2.1% for the primary CABG group, without any significant difference. However, off-pump surgery in redo group had a positive impact on lower mortality than on-pump surgery (1.5% versus 5.3%) [19]. Ngaage et al. [20] studied the impact of preoperative symptom severity on the outcomes of reoperative cardiac surgery in Castle Hill Hospital, United Kingdom. Between 1998 and 2006, they had 154 reoperative CABG patients. Patients were divided into two groups, the first one from 1998 to 2002 and the second group from 2002 to 2006. The operative mortality was 4.8% for the first group versus 2.8% for the second group with no significant difference. Reoperation was not a determining predictor of major adverse postoperative event unlike age, pre-existing atrial fibrillation, duration of extracorporeal circulation, and concomitant valve procedure [20]. In older studies, hospital mortality was higher like in Weintraub and colleagues study of 2030 reoperative CABG patient at Emory University Hospitals, Atlanta, USA between 1975 and 1993. They had hospital mortality of 7%. Also, in Noyez’s study in Netherland between 1987 and 1998 hospital mortality of reoperative CABG was 6.7%. In Christenson’s study at Geneva, Switzerland 594 patients had reoperative CABG between 1984 and 1994 with hospital mortality of 9.6% [21- 23]. In van Eck study, hospital mortality rate after reoperative CABG decreased significantly from 11% in the period from 1987 to 1991, to 4.2% at the period from 1996 to 2000 [16].

As for Cleveland Clinic, it has been one of the largest cardiac centers all over the world, having the highest rates of reoperative CABG they provided the largest single-center studies for the literature over time. Between 1983 and 1993, Yamamuro et al. [24] studied the risk factors and outcomes after reoperative CABG in 739 elderly patients (age ≥ 70). At this era, the incidence of reoperative CABG was increasing (26 cases in 1983, 123 cases in 1992). Hospital mortality rates were 7.6% [24]. Lytle et al. [11] analyzed the in-hospital mortality of 1663 reoperative CABG patients from 1988 through 1991 to study the influence of arterial grafts on the mortality. In this study, hospital mortality was 3.7% [11]. In Sabik’s [12] study for reoperative CABG from 1990 to 2003, hospital mortality for patients having reoperative CABG was 4.4%. However, this rate decreased from 6% in 1990 to around 2.2% in 2000. Also, when the patients were stratified by date of operation, multivariable analysis demonstrated that after January 1, 1997, the risk of hospital death was the same in reoperative and primary CABG patients. For the propensitymatched patients, hospital mortality was still higher after reoperations (4.7%) than after primary operations (2.2%). However, when the propensity-matched patients were stratified by date of operation, multivariable analysis demonstrated that, after 1997 reoperation was not associated with increased risk of death. Then they concluded that surgical experience had neutralized the risk of reoperation attributable to its technical difficulty, while patient characteristics had a greater influence on hospital mortality [12].

Conclusion

The incidence of reoperative CABG has been decreasing over the last decade after reaching its peak in the 1990s. On the other hand, hospital mortality rates after reoperative CABG have been improving overtime despite the fact that the patients’ risk profiles have been deteriorating.

For more articles in Open Access Journal of Case Studies please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/jojcs/index.php

#juniper publishers journals#Juniper Publishers Contact#Surgical case reports#Gastrointestinal Surgery#Medicine Neurosurgery#Obstetrics and Gynaecology

0 notes

Text

Altius Offices, Mexico City

Altius Offices, Mexico City, Commercial Development, Mexican Interior Architecture Images, Architect

Altius Offices in Mexico City

23 Mar 2021

Altius Offices

Design: RIMA Arquitectura / Ricardo Urías

Location: México, North America

This corporate architecture project is a reintervention to the Altius Offices, which house a marketing company. The first phase of this project was also done by RIMA Arquitectura back in 2013. Due to the growth in numbers of staff members, a plan that reinterprets the past few years’ organizational changes –without losing the brand’s creative personality– was requested.

In order to achieve optimum results, the work flow relationship between all of the company’s different areas was analyzed, without losing touch of the natural lighting these spaces already receive and the specific ways in which this company –and its collaborators– work. This analysis was the foundation and the guiding principle behind every trace, shape, color and design finishes chosen to create a wholesome and functional work environment.

The former program’s configuration was composed of private offices and a few open areas. This fragmentation between the public and private spheres did not allow its users to fully take advantage of the space’s operative capacities. Hence, the new intention was to generate an open environment with as much natural lighting as possible, as well as open areas that allow for different ways of working: be it a classic individual work space –from your own desk–, or a collaborative work space that can remain open or closed.

The project’s entrance is through a main lobby, wrapped by a rustic wooden wall that unfolds itself to become the hallway that leads to the main common area. Here, the principal element is a pine plywood stand, covered with pillows to make its seating comfortable; it´s a dynamic space for working, taking meetings and holding conferences.

The rest of the space houses the central common work area with long lacquered OSB tables. In front, you’ll find three private rooms with drywall partitions and crystal fronts. The use of rustic wood and OSB, besides being recycled materials that heighten the project’s sustainability, bring a distinctive personality to the Altius offices, along with the use of blue asymetric ceilings and a continuous line of LED luminaries that cover just one side of the exposed boxed ceiling slab.

Having the chance to reimagine and doing some necessary changes to a project designed by us seven years ago provided an opportunity to understand the ways in which the corporate world, and its relationship to space, have changed.

Due to the rise of collaborative efforts in the workplace, private spaces are being left behind. The big challenge here was to create transparent, well disposed and functional spaces that speak to the company’s contemporary identity.

Altius Offices, Mexico City – Building Information

Design: RIMA Arquitectura

Location: Mexico City, Mexico, North America

Area: 139 sqm

Year: 2020

Photography: Frank Lynen

Altius Offices in Mexico City images / information received 230321

Location: México, North America

Mexican Houses

New Residential Buildings Mexico

New Mexican Properties

image courtesy of architects studio

Casa Huizache, San Miguel de Allende

Architect: Paul Cremoux W.

image Courtesy architecture office

Casa Huizache

Casa Cozumel, Quintana Roo

Architects: Sordo Madaleno Arquitectos

photograph : Rafael Gamo

Casa Cozumel in Quintana Roo

Casa Ithualli, Monterrey, Ciudad de México

Design: Miró Rivera Architects (MRA)

photograph : Adrián Llaguno | Documentación Arquitectónica

Casa Ithualli, Monterrey

Mexican Architecture

Contemporary Mexican Buildings

Mexican Architectural Designs – chronological list

Mexico City Architecture Tours – city walks by e-architect

Mexican Architecture Offices

Mexican Architecture Buildings

Bolerama Coyoacan Mexico City

Design: Arroyo Soliz Agraz

image from architect

Bolerama Coyoacan Mexico City

Mexico City Buildings

Buildings / photos for the Altius Offices in Mexico City page welcome

The post Altius Offices, Mexico City appeared first on e-architect.

0 notes

Text

Juniper Publishers| Relaparotomy : Analysis of 50 Cases And Review of Literature

Journal of Surgery

-

JuniperPublishers

Abstract

Introduction: Reoperative Abdominal Surgery (Relaparotomy) means an unplanned reintervention carried out during the immediate postoperative period after laparotomy and causally related to first operation.

Method: The study had been carried out in upgraded department of General Surgery in SMS Medical College and Hospital. The cases comprises of operated in SMS Hospital and those referred from other surgical centers.

Results: Maximum patients 70% needs relaparotomy only one time which had minimum mortality (11.4%). Four patients (8%) were needed relaparotomy 3 times in which 2 patient were expired. Mean while mortality rate of 3rd relaparotomy was 50%. Relaparotomy were done mainly for adhesion obstruction and anastomotic leakage. Adhesion obstruction superwanes anastomotic leakage (40% v/s 28%). 4% patients in which foreign body (sponge in peritoneal cavity at the time of previous surgery) were found both cases operated for caesarian section. 68% patients were refered from some other institution

Conclusion: Decision to perform relaparotomy as per patients condition, if taken in time it can improv overall survival and have a positive impact on decrease length of hospital stay, overall cost of treatment and morbidity as well as mortality.

Go to

Introduction

Reoperative Abdominal Surgery (Relaparotomy) means an unplanned reintervention carried out during the immediate postoperative period after laparotomy and causally related to first operation. In practice laparotomy and relaparotomy as thus defined are performed with few exceptions during the same stay in hospital [1-13]. Relaparotomy is carried out for wide range of indications. The highest incidence is seen in gastrointestinal surgery and the lowest in vascular surgery. Main Indications are:

Haemorrhage

Ileus

Paritonitis

Disruption of anastomoses and infection.

Residual intra peritoneal abscess

Fistulae

Acute postoperative adhesion obstruction

Multiple system failure

Miscellaneous Indications

Relaparotomy carries very high morbidity and mortality. Mortality range varies from 40 to 45 % as mentioned in various studies [4,11]. Relaparotomy for dehiscence and obstruction carried minimal risk; for bleeding and infection entailed moderate risks; and for anastomotic leak have highest mortality rate. The mortality rate increased in older age groups, multiple system and organ failure and multiple relaparotomies. Timely relaparotomy is valuable in the identification and treatment of complications following abdominal surgery.

The literature on relaparotomy is confusing. The incidence and mortality rates are greately affected by the type of surgery reported. There also a difference between recent and older studies with regard to definitions and indications for relaparotomy, rendering comparisions of these studies rather useless [11]. With the advent of newer antibiotics, better management of fluid and electrolyte imbalance and latest investigations particularly contrast CT Scan abdomen and MRI, surgeons are able to diagnose the problem after first laparotomy in most cases which helps to better management of these cases. Whether these antibiotic, investigations and other things have improved the morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing relaparotomy will also be studied.

Go to

Aims and Objectives

Analysis of cases of relaparotomy regarding indications, the organ of primary operations, age of patients to analyse incidence, morbidity and mortality and other factors.

To study the importance of technique and other error at primary operation and benefits gain from relaparotomy.

To know whether timing of relaparotomy has effect on morbidity and mortality.

Go to

Materials and Methods

The study had been carried out in upgraded department of General Surgery in SMS Medical College and Hospital. The cases comprise of operated in SMS Hospital and those referred from other surgical centers. Detailed history and examination were recorded in performs with special note on original operation or procedure attempted previously. Presentation of patient in immediate postoperative period or delayed postoperative period were noted. A battery of investigations including various routine and special blood investigation, USG and other radiological investigations were done. CT Scan, MRI were undertaken as per requirement. The detailed finding of relaparotomy was noted. Patient were monitored postoperatively and progress of patient were assessed and any immediate or delayed postoperative complications were recorded.

Inclusion Criteria

Patients more than 12 years of age who underwent laparotomy for various indications and needed reexploration for dealing the complications.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients below 12 years of age.

Patients operated for Hernia.

Patients who required minor surgical procedures and operations on abdominal wall.

Cases of abdominal wound dehiscence.

Stoma closure i.e. Ileostomy and Colostomy

Go to

Results

As given in Table 1, In our study most of cases (52%) were in the age group 31-50yrs. 16 cases (32%) were adults in forth decade.

Age range

lowest-12yrs

highest-75yrs

Mean age - 41

Mean deviation = 2.02

Maximum cases (52%) were re-explored within 2-7 days.

Most of the patient in this category were anastomotic leakage, heamorrhage, perforation repair in which anastomotic leakage was outnumbered.

Mean time gap= 11.27

Maximum patients 70% needs relaparotomy only one time which had minimum mortality (11.4%). Four patients (8%) were needed relaparotomy 3 times in which 2 patient were expired. Mean while mortality rate of 3rd relaparotomy was 50%.

Relaparotomy were done mainly for adhesion obstruction and anastomotic leakage. Adhesion obstruction superwanes anastomotic leakage (40% v/s 28%). 4% patients in which foreign body (sponge in peritoneal cavity at the time of previous surgery) were found both cases operated for caesarian section. 68% patients were refered from some other institution.

A. Referred case :

Mean - 4.8

Mean deviation - 3.55

Standard deviation - 4.22

B. Our Institution case :

Mean - 2.29

Mean deviation - 2.12

Standard deviation - 2.49

Mean - 10.7

Mean deviation - 4.81

Standard deviation - 5.33

Go to

Discussion and Conclusion

In our study most of cases (52%) were in the age group 31-50yrs. 16 cases (32%) were adults in forth decade. Maximum cases (52%) were re-explored within 2-7 days. Most of the patient in this category were anastomotic leakage, heamorrhage, perforation repair in which anastomotic leakage was outnumbered. Mean time gap was 11.27 days. Maximum patients 70% needs relaparotomy only one time which had minimum mortality (11.4%). Four patients (8%) were needed relaparotomy 3 times in which 2 patient were expired. Mean while mortality rate of 3rd relaparotomy was 50%. Relaparotomy were done mainly for adhesion obstruction and anastomotic leakage. Adhesion obstruction superwanes anastomotic leakage (40% v/s 28%). 4% patients in which foreign body (sponge in peritoneal cavity at the time of previous surgery) were found both cases operated for caesarian section. 68% patients were refered from some other institution.

In 40% cases adhesionolysis were done with or without associated ileostomy or feeding jejunostomy. 10% patients need exteriorization of loop in such circumstances where resection anastomosis was not possible. Multiple adhesions were outnumbered as compared to single band adhesion. The ratio of multiple verses single band adhesion was 4 : 1 (16/4 cases). In 54% cases there was no apparent error found that was responsible for cause of relaparotomy (Tables 2-8). We found technical error in approx 12% cases and in 34% cases presumptive error was found. As a complication of relaparotomy maximum case having wound infection was observed (44%) approximately half of them proceeds into wound dehiscence or burst abdomen. 10 patients or relaparotomies were expired, thus morality rate observed in our studies was 20%.4 cases (40%) were expired due to sepsis and septicaemic shock.

Go to

Review of Literature

Harry Tera Curt Aberg, Sweden [14]. Relaparotomy is a serious reality for every abdominal surgeon. Elderly patients are at greater risk and have a grave prognosis. Complications that carried out high mortality are namely wound rupture after colon surgery and suture breakdown with peritonitis following gastric surgery. These facts should be kept in mind throughout every routine laparotomy and at every stage of operation surgeon should remain wide awake to the risk of complication that may require relaparotomy [12]. Michael Zer, Shlomo Dux [15]. did a study regarding timing of laparotomy and its influence on prognosis. Lorenc and Driver favour early reoperation and state that such patients have far more to gain than to lose by reexploration [13]. Lorenc admitted that fear of an unfavourable outcome led to undue postponement of reintervention in many cases of postoperative complications and he recommended that early re intervention be adopted as a policy of choice.

James GH Bernard MJ, New York (1983), did a study and concluded that most common finding during relaparotomy was intra-abdominal abscess, other finding included anastomotic leak, necrotic bowel, evidence of technical errors and acalculous cholecystitis. The most common clinical finding were localised tenderness, fever and absent bowel sound. CT Scan and contrast radiography were most accurate. Harbrecht PJ, Garrison RN Fry DE [4]. Intervals from laparotomy to relaparotomy varied widely with the indications. These were relatively brief intervals from laparotomy to relaparotomy for bleeding and long intervals to relaparotomy for obstructions. Relaparotomy for infections with intact organs caused the most complex problems.

Rudolph Krause [12]. Factors that appear to correlate with mortality are age over more than 50 years peritonisis at initial procedures and multiple system failure. Criteria leading to relaparotomy are usually clinical (tenderness, fever, and absence of bowel sounds) and to a minor extent depending onn radiological procedures of which computed tomographics scanning has the highest accuracy (97%), multiple system failure carries the highest mortality rate (80%, if treated) and presents the greatest number of negative laparotomies [11]. RM Kirk [10]. Royal Free Hospital, London (1988) The decision to reoperate was based on clinical findings in 97.8% although investigations were often helpful in localizing the site of the complicating lesion. Leaks and bleeding were most frequent and carried a high mertality.

Makela J and Kairaluoma M I [14]. Relaparotomy for postoperative intra-abdominal sepsis in jaundiced patients.. Postoperative sepsis was caused by intra-abdominal abscess in 16 cases (53 per cent), by suture line leakage in 9 cases (30 per cent) and by technical error in 5 cases (17 per cent). Abscesses occurred most commonly in the subphrenic space (6 cases), in the subhepatic space (6 cases) and in the lesser sac (5 cases). Sepsis was associated with single organ failure in 20 cases and with multiple organ failure in 10 cases. The overall mortality rate was 50 per cent (15/30).

Pickleman J, Lee RM [8]. Non operative management should be tried in every patients with suspected early postoperative small bowel obstruction unless clear signs of bowel ischemia are present. A nasogastric tube will provide adequate decompression and total parenteral nutrition should be instituted. If the patient remain stable, this treatment should be continued for 2 weeks [14-39]. After this time further improvement is unlikely and reexploration should be performed unless there are clinical or radiological signs of relenting obstruction. D I KrivitskiÄV A ShuliarenkoI A Babin [9]. 10,446 patients were operated on. There were the following indications for relaparotomy: diffuse and circumscribed peritonitis (78 patients), ileus (46), eventration (11), hemorrhage (12), others (5). Diagnosis of postoperative complications requiring relaparotomy is difficult. The postoperative was 26%.

AR Mossa, David M, Bruce S [1]. They did a study regarding iatrogenic bile duct injuries and mention factors contributing it namely. Dangerous disease (convalescence from acute cholecystitis or with portal hypertension) Dangerous anatomy (anomalies in 10-15% cases). Dangerous surgery (Most common cause) [1]. Zavernyi LG, Poida, Me AI VM, Bondarenko ND, Tarasov AA, et al. [13]. The analysis and processing with the use of a special method of 54 direct observations and 342 case records of the patients with early postoperative intraabdominal complications were carried out. A method for syndrome prediction of the outcomes of relaparotomy has been developed [40-43]. The syndromes of the most significant predictive value have been revealed: those of intoxication, respiratory and hepatorenal failure, impaired hemodynamics and electrolytic metabolism, hemocoagulation. Use in clinical practice of the method mentioned as well as the methods promoting timely detection of the intraabdominal complications permitted to reduce lethality after relaparotomy from 21.4 to 15.3%.

Haut Ohmann, Wolmeshauser, Wacha, Qun yang wittmann, H Dellinger e, et al. [43]. Planned relaparotomy was defined as at least one relaparotomy decided on at the time of the first surgical intervention ; RD, relaparotomy indicated by clinical findings. There was no significant difference in mortality between patients treated with PR (21%) or RD (13%). Postoperative multiple organ failure as defined by a Goris score of more than 5 was more frequent in the group of patients undergoing PR (50%), compared with the group undergoing RD (24%) (P=.01), as were infectious complications (68% vs 39% [P=.01]). Infectious complications were due to more frequent suture leaks (16% vs 0% [P=.05]), recurrent intra-abdominal sepsis (16% vs 0% [P=.05]), and septecemia (45% vs 18% [P=.05]) in the PR vs the RD groups. They Concluded that until larger prospective studies are available, the indication for PR should be evaluated with caution (Tables 9 & 10).

Koerna T, Schulz F [18]. Relaparotomy in peritonitis,prognosis and treatment of patients with persisting intraabdominal infection.some patients are prone to persisting intraabdominal infection regardless of initial eradication of the source of infection. There was no significant difference in the postoperative mortality rate between “planned relaparotomy” and “relaparotomy on demand”(54.5% versus 50.6%).Timely relaparotomy provides the only surgical option that significantly improves outcome. To improve overall survival the decision to perform a relaparotomy on demand after an initially successful eradication of the source of ,infection must be made within 48hr,at least before MODS emerges.

Lamme B, Boermeester MA, Reitsma J B, Mahler CW, Obertop H, Gouma DJ [32]. The combined results of observational studies showed a statistically non-significant reduction in mortality for the on-demand relaparotomy strategy compared with the planned relaparotomy strategy. However, owing to the nonrandomised nature of the studies, the limited number of patients per study and the heterogeneity between studies, the overall results were inconclusive. VJ verwaal, Academisch Ziekenhuis, St Radboud, Nijmegen, The Netherlands [33]. 46 patients with abdominal sepsis were treated. The diagnosis of abdominal sepsis was defined as meeting the Bone criteria for sepsis before operation, in combination with infection of the abdomen proven by laparotomy. After the first laparotomy there were 41 relaparotomies in these 46 patients. From 2 days before to 3 days after the relaparotomy, data were collected to compile the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) III and Multiple Organ Failure (MOF) scores. The scores were compared before and after relaparotomy, and were also compared between patients who had a recurrent infection in the abdomen and those who did not.

During 41 relaparotomies, 16 patients were found to have a pus collection. Of these clinical infections only 11 had a positive culture. In patients with clinical infection there was also no difference pre and post operative. The same applied for patients with and without positive intraabdominal cultures. Relaparotomy in patients with abdominal sepsis did not have a negative effect on prognosis within a few days after reoperation.

The authors did not find any reason to use APACHE III or MOF scoring as an indication for relaparotomy (Table 11).

Exposito EM, Argon PF, Curbelo PR, Perez AJ [34]. The group of AA remained constituted of 25 patients with an average age of 46 years and with an APACHE II score of 20.63 ± 3.24. The group of the programmed relaparotomies (RP) was conformed of 35 patients whose average age was 52 years and APACHE II score, 22.85 ± 5.68. Intestinal fistula was observed in three patients (12%) of the AA group and the abdominal compartment syndrome in two patient (5.7%) of the RP group. Five (20%) abdominal wall hernias were found in patients of the AA group, while only one patient in the RP group (2.8%) had a hernia [44- 50]. They found significant differences between both groups utilizing mortality as variable of grouping. We think that early diagnosis of intraabdominal sepsis continues as the fundamental beginning to diminish mortality of the patients with acute peritonitis independent of the surgical technique utilized, the capacity of the administered antibiotics, and the solvency of support care.

Hilzheimer RG, Gathof B [17]. Relaparotomy for complicated secondary peritonitis-how to identify patients at risk for persistent sepsis. N Hiki, Y Takeshita, K Kubota, E Tsuji, H Yamaguchi, et al. [38]. Postoperative small bowel obstruction following abdominal procedures is more common in patients who have undergone laparotomy The typical winter weather in Tokyo is characterised by low temperatures, low humidity and moderate air pressure. These winter climate conditions could be correlated with an increased incidence of postoperative small bowel obstruction in during our observation period.

Jonas Dauderys,Donatas Venskutonis [45]. Relaparotomy must be motivated, timely, and must certainly remove cause of the complication. Formalion of feeding microjejunostomy should be a component of the relaparotomy. In case of diffuse peritonitis a repeated programmed relaparotomies nowdays are not advisable. Hutchins RR,Gunning MP,Lucas DN [19]. Relaparotomy may be beneficial in patients developing intraperitoneal sepsis after abdominal procedures.They also assessed the effect of patient age &sex, disease presentation and severity, interval to relaparotomy, and the number of relaparotomies on survival after relaparotomy. Patient age and multiorgan failure prior to relaparotomy-but not urgency of initial laparotomy or the acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE ll) score prior to relaparotomy, interval to relaparotomy,or number of relaparotomies-affected the outcome. The identification of intraperitoneal sepsis and performance of relaparotomy earlier after the initial abdominal surgery might reduce the high rrate (60%) of multiorgan failure prior to relaparotomy and improve survival after it.

Elie oussltouzoglou, pillippe bacheliar, Jean marc bigourden, Hiroshi nakano [39]. The overall relaparotomy rate was significantly lower in the PG group (4.7%) than in the PJ group(18%; P = .001). The rate of relaparotomy required to treat complications of PF after PD was 52.9% (9/17) in the PJ group. In the PG group, none of the 4 patients who developed PF required relaparotomy. Martínez-Ordaz JL, Suárez-Moreno RM, Felipez- Aguilar OJ, Blanco-Benavides R [27]. To assess the mortality related factors of patients after relaparotomy on demand. In some patients, a relaparotomy after a primary laparotomy is necessary, most due to acute complications. The relaparotomy can be planned or on demand based on the evolution of the patient.Of 51 relaparotomies, 98% were positive. Nineteen of the 33 patients died, resulting in a mortality rate of 58%. The factors associated with mortality were development of an intestinal fistula (p <0.02), wound infection (p <0.03), generalized peritonitis in the primary surgery (p <<0.001), urgent primary laparotomy (p <0.003), development of multiple organ failure (p<0.005), and respiratory insufficiency (p <0.01). Conclusions: Laparotomy on demand is useful in the treatment of patients with abdominal sepsis; however, the mortality is still very high.

Unalp HR, Kamer E, Kar H, Bal A,Peskersoy M [22]. Treatment of a number of complications that occur after abdominal surgeries may require that urgent abdominal Re-explorations (UAR) ,the life saving and obligatory operations are performed. UARs that are perfomed following complicated abdominal have high mortality rates. In particular, UARs have higher mortality rates following GIS surgeries or when infectious complications occur.The possibility of efficiently lowering these high rates depends on the success of the first operations that the patient had received. Neil Hyman, Thomas LM, Turner O [7]. More than half of leaks can be managed without fecal diversion. Anastomotic disruption is perhaps the most dreaded complication after intestinal surgery.

Ruler, van o,Lamme B, Gouma DJ, Reitsma JB, Boermeester [26]. The decision whether and when to perform a relaparotomy in secondary peritonitis is largely subjective and based on professional experience. No exiting scoring system aids in this decisional process.One preoperative predictor and five postoperative predictors significantly increased the need of relaparotomy.

Younger age

Decreased hemoglobin levels,

Temperature>39 degrees C

Lower Pao(2)/Fio2 ratio,

Increased heart rate

Increased sodium levels.

Causes of secondary peritonitis and finding at emergency laparotomy for peritonitis are poor indicators for whether patients will need a relaparotomy. Factors indicative of progressive or persistent organ failure during arly postoperative follow-up are the best indicators for ongoing infection and associated positive findings at relaparotomy.

Jean-Jacques Duron, Nathalie Jourdan-Da Silva, Sophie Tezenas du Montcel, Anne Berger, Fabrice Muscari, et al. [35]. Postoperative intraperitoneal adhesions, or bands, resulting from any type of abdominal surgery, are the main cause of adhesive postoperative small bowel obstructions, which represent a life-long issue. Recurrences after operated adhesive postoperative SBO are a threatening potentiality for patients and a difficult problem facing any surgeon. Operated adhesive postoperative SBO is a clinical entity with a high recurrence rate and specific risk factors of recurrences. Thus, the patients operated on for adhesive postoperative SBO may be candidates for the preventive use of anti-adhesion agents, particularly when a risk factor of recurrence is present.

Opening the peritoneal cavity, in whatever type of surgery, leads to the formation of potentially obstructive structures (adhesions or bands) in almost 95% of patients. Today, with the increased incidence of abdominal surgery, these structures are the most frequent cause of small bowel obstruction (SBO). Since 1990, it has been reported that adhesive SBO occurs in 3% of all laparotomies, 1% during the first postoperative year. After operated adhesive postoperative SBO, a risk of recurrence remains and the literature reported a wide ranging rate of overall recurrence (range, 8.7%-53%) at 3 years and more. These variations may be due to the retrospective type of the studies.

Today, operated adhesive postoperative SBO proves to be a clinical entity with high incidence and specific risk factors of recurrence: age <40 years, presence of adhesion or matted adhesion, and postoperative surgical complications. These results render patients undergoing operated adhesive postoperative SBO candidates for the preventive use of antiadhesion agents, particularly when a risk factor of recurrence is present. JBC Vander wal, J Jeekel [6]. Postoperative adhesion formation is the most frequent complication of surgery. With the incidence of 55 to 100% in all abdominal operations adhesions are responsible for and increased risk of small bowel obstraction, chronic abdominal pain and infertility. Statins may play a role in postoperative adhesion prevention.

Acute adhesive obstruction of the small intestine is a surgical Emergency In which there is risk of intestinal strangulation. By delaying diagnosis and institution of appropriate treatment for strangulated obstruction, morbidity and mortality from sepsis are greatly increased in comparison to simple obstruction. Postoperatively most common cause of SBO is peritoneal adhesions.In particular colorectal, surgery is noted of the largest offeders, especially after proctocolectomy and ileal pouch anal aastomosis. Pelvic or lower abdominal procedures are blamed for adhesion formation more commonly than upper abdominal proceduresare, although any abdominal operation can be responsible. They result in an inflammatory cascade involving the activation of complement and coagulation. Fibrinogen is produced during this response and converted to fibrin by thrombin. If fibrin persists,it adheres to injured surfaces and initiates the formation of a matrix of collagen and fibroblasts,thereby forming fibrous adhesions from fibrinous adhesions.

Go to

Prevention

Technical efforts much as gentle tissue handling ,minimal use of foreign materials, careful haemostatic measures, and prevention of infection,ischemia, and desication.

Substences including amniotic fluid, bovine cecum, shark peritoneum, fish bladder, vitreous of calfs eye, lubricants ,gels,polymers, and various physical barriers.

Sodium hyaluronate-based bioresorbable membrane,seprafilm, which persists in the abdomen for 5 to 7days [6].

Doeksen A, Tanis PJ, Vrouenraets BC, Lanschot van JJ, Tets van WF [25]. An intervening weekend and negative diagnostic imaging reports may contribute to a delay in diagnosis and relaparotomy for anastomotic leakage. That delay was more than two days in two-thirds of the patients. Oddeke vR,cecilia WM, Kimberly RB [20]. In patients with severe secondary peritonitis, there are 2 surgical treatment strategies following an initial emergency laparotomy; planned relaparotomy and relaparotomy only when the patients condition demands it.The on demand strategy may reduce mortality, morbidity,health care utilization, and costs.But not have a significantly lower rate of death or major peritonitis -related morbidity.

Seal SL,Kamilya G,Bhattacharyya SK,Mukherji J,Bhattacharyya AR [31]. Repeat laparotomy within 6 weeks of cesarean delivery was required following 1 in 300 cases done in an Indian teaching hospital. The majority of these were preventable and could have been avoided if adequate attention had been paid at the time of the primary surgery. Christian Nordqvist [48]. Rather than carrying out repeat surgery for patients with severe intraabdominal inflammation or infection (peritonitis) routinely, it might be better to just have the repeat surgery when clinical improvement is lacking. Secondary peritonitis has a death rate of between 20%-60%, patients stay in hospital for a long time and also are much more likely to experience illness due to the development of sepsis with multiple organ failure.

About 12%-16% of patients who choose to undergo abdominal surgery develop post-operative peritonitis. Health care utilization due to secondary peritonitis is extensive, with operations to eliminate the source of infection (laparotomy [surgery involving the intra-abdominal contents]) and multidisciplinary care in the intensive care unit setting.” The writers also point out that after the initial laparotomy, relaparotomy may be needed to eliminate persistent peritonitis or new infections. “There are 2 widely used relaparotomy strategies: relaparotomy when the patient’s condition demands it (‘on-demand’) and planned relaparotomy. In the planned strategy, a relaparotomy is performed every 36 to 48 hours for inspection, drainage, and peritoneal lavage [flushing out] of the abdominal cavity until findings are negative for ongoing peritonitis. Judith Groch, Robert Jasmer [41]. In severe peritonitis, repeat laparotomy done only when the patient’s condition demands it cuts down on the number of procedures and on medical costs, researchers found.

Go to

Action Points

Explain to interested patients that doing a repeat laparotomy after emergency surgery for severe peritonitis is common.

Explain that sometimes it’s done on a preplanned schedule - every 36 to 48 hours - and sometimes it’s done only when the patient’s condition demands it.

Note that both strategies have about the same morbidity and mortality, but that the “on demand” tactic may reduce the number of repeat procedures and the medical costs.

On-demand relaparotomy did not reduce mortality or morbidity. Patients had severe secondary peritonitis and an Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHEII) score of 11 or greater. A key challenge for an on-demand strategy is to adequately select patients for relaparotomy and to prevent potential harmful delay in reintervention by adequate and frequent patient monitoring, the researchers suggested. One of the difficulties in research on secondary peritonitis is the heterogeneity of the study population, regarding severity of disease, etiology, and localization of the infectious focus. These factors make it difficult to extrapolate study results to individual patients in clinical practice. For this reason, the researchers said, they excluded disease entities, such as pancreatitis, with a substantially different prognosis and requiring different treatment strategies, they wrote [41,42].

Lombardovaillant,TomásAriel; FernandezExposito,Wilfredo Y Casamayor Jaime, Zuleika [49]. Relaparotomy on demand is a proper procedure for peritonitis of moderate intensity, whereas the scheduled procedure is adequate for patients with severe peritonitis and uncertain intestinal viability. The first postoperative week had the highest incidence on adverse events and required more surveillance. Alexander R Novotny, Klaus Emmanuel, Norbert Hueser, Carolin Knebel, Monika Kriner, et al. [46]. On-demand relaparotomy has been associated with a slightly decreased mortality compared to planned relaparotomy in the surgical treatment of secondary peritonitis. On-demand relaparotomy must be performed without delay to detect progressing sepsis early, before the onset of multiorgan failure. The PCT ratio appears to be a valuable aid in deciding if further relaparotomies are necessary after initial operative treatment of an intraabdominal septic focus.

Brain A Nobie [36]. A small-bowel obstruction (SBO) is caused by a variety of pathologic processes. The leading causeof SBO in developed countries is postoperative adhesions (60%) followed by malignancy, Crohn’s disease, and hernias, although some studies have reported Crohn disease as a greater etiologic factor than neoplasia. Surgeries most closely associated with SBO are appendectomy, colorectal surgery, and gynecologic and upper gastrointestinal (GI) procedures. One study from Canada reported a higher frequency of SBO after colorectal surgery, followed by gynecologic surgery, hernia repair, and appendectomy. Lower abdominal and pelvic surgeries lead to obstruction more often than upper GI surgeries.

Go to

Causes

The most common cause of SBO is postsurgical adhesions.

Postoperative adhesions can be the cause of acute obstruction within 4 weeks of surgery or of chronic obstruction decades later.

The incidence of SBO parallels the increasing number of laparotomies performed in developing countries.

The second most common identified cause of SBO is an incarcerated groin hernia.

Other etiologies of SBO include malignant tumor (20%), hernia (10%), inflammatory bowel disease (5%), volvulus (3%), and miscellaneous causes (2%).

The causes of SBO in pediatric patients include congenital atresia, pyloric stenosis, and intussusception [36].