#sad news… i’m a missourian

Text

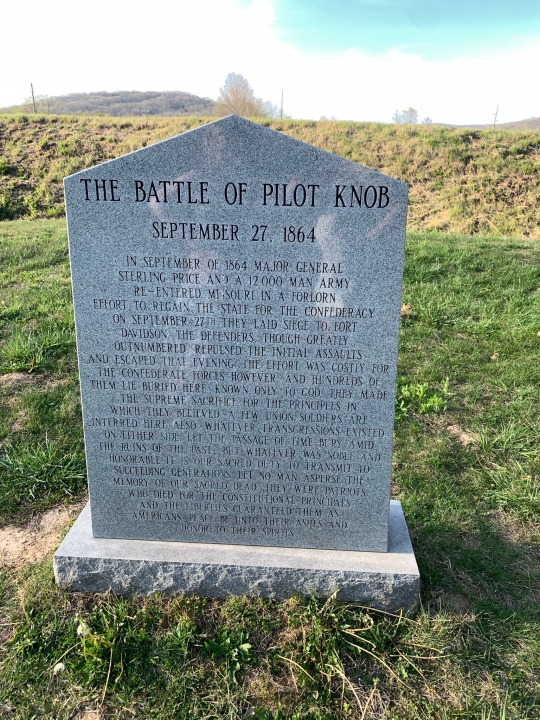

saw an eclipse and forced my friend to come drive through traffic with me to see some dead mfs on a battlefield

#sad news… i’m a missourian#this is all we got#genuinely have never seen more people in the vicinity of pilot knob/ironton in my life#american civil war#acw#pilot knob

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The summer wasn’t meant to be like this. By April, Greene County, in southwestern Missouri, seemed to be past the worst of the pandemic. Intensive-care units that once overflowed had emptied. Vaccinations were rising. Health-care workers who had been fighting the coronavirus for months felt relieved—perhaps even hopeful. Then, in late May, cases started ticking up again. By July, the surge was so pronounced that “it took the wind out of everyone,” Erik Frederick, the chief administrative officer of Mercy Hospital Springfield, told me. “How did we end up back here again?”

The hospital is now busier than at any previous point during the pandemic. In just five weeks, it took in as many COVID-19 patients as it did over five months last year. Ten minutes away, another big hospital, Cox Medical Center South, has been inundated just as quickly. “We only get beds available when someone dies, which happens several times a day,” Terrence Coulter, the critical-care medical director at CoxHealth, told me.

Last week, Katie Towns, the acting director of the Springfield–Greene County Health Department, was concerned that the county’s daily cases were topping 250. On Wednesday, the daily count hit 405. This dramatic surge is the work of the super-contagious Delta variant, which now accounts for 95 percent of Greene County’s new cases, according to Towns. It is spreading easily because people have ditched their masks, crowded into indoor spaces, resumed travel, and resisted vaccinations. Just 40 percent of people in Greene County are fully vaccinated. In some nearby counties, less than 20 percent of people are.

Many experts have argued that, even with Delta, the United States is unlikely to revisit the horrors of last winter. Even now, the country’s hospitalizations are one-seventh as high as they were in mid-January. But national optimism glosses over local reality. For many communities, this year will be worse than last. Springfield’s health-care workers and public-health specialists are experiencing the same ordeals they thought they had left behind. “But it feels worse this time because we’ve seen it before,” Amelia Montgomery, a nurse at CoxHealth, told me. “Walking back into the COVID ICU was demoralizing.”

Those ICUs are also filling with younger patients, in their 20s, 30s, and 40s, including many with no underlying health problems. In part, that’s because elderly people have been more likely to get vaccinated, leaving Delta with a younger pool of vulnerable hosts. While experts are still uncertain if Delta is deadlier than the original coronavirus, every physician and nurse in Missouri whom I spoke with told me that the 30- and 40-something COVID-19 patients they’re now seeing are much sicker than those they saw last year. “That age group did get COVID before, but they didn’t usually end up in the ICU like they are now,” Jonathan Brown, a respiratory therapist at Mercy, told me. Nurses are watching families navigate end-of-life decisions for young people who have no advance directives or other legal documents in place.

Almost every COVID-19 patient in Springfield’s hospitals is unvaccinated, and the dozen or so exceptions are all either elderly or immunocompromised people. The vaccines are working as intended, but the number of people who have refused to get their shots is crushing morale. Vaccines were meant to be the end of the pandemic. If people don’t get them, the actual end will look more like Springfield’s present: a succession of COVID-19 waves that will break unevenly across the country until everyone has either been vaccinated or infected. “You hear post-pandemic a lot,” Frederick said. “We’re clearly not post-pandemic. New York threw a ticker-tape parade for its health-care heroes, and ours are knee-deep in COVID.”

That they are in this position despite the wide availability of vaccines turns difficult days into unbearable ones. As bad as the winter surge was, Springfield’s health-care workers shared a common purpose of serving their community, Steve Edwards, the president and CEO of CoxHealth, told me. But now they’re “putting themselves in harm’s way for people who’ve chosen not to protect themselves,” he said. While there were always ways of preventing COVID-19 infections, Missourians could have almost entirely prevented this surge through vaccination—but didn’t. “My sense of hope is dwindling,” Tracy Hill, a nurse at Mercy, told me. “I’m losing a little bit of faith in mankind. But you can’t just not go to work.”

When Springfield’s hospitals saw the first pandemic wave hitting the coasts, they could steel themselves. This time, with Delta thrashing Missouri fast and first, they haven’t had time to summon sufficient reinforcements. Between them, Mercy and Cox South have recruited about 300 traveling nurses, respiratory therapists, and other specialists, which is still less than they need. The hospitals’ health-care workers have adequate PPE and most are vaccinated. But in the ICUs and in COVID-19 wards, respiratory therapists still must constantly adjust ventilators, entire teams must regularly flip patients onto their belly and back again, and nurses spend long shifts drenched in sweat as they repeatedly don and doff protective gear. In previous phases of the pandemic, both hospitals took in patients from other counties and states. “Now we’re blasting outward,” Coulter said. “We’re already saturating the surrounding hospitals.”

Meanwhile, the hospitals’ own staff members are exhausted beyond telling. After the winter surge, they spent months catching up on record numbers of postponed surgeries and other procedures. Now they’re facing their sharpest COVID-19 surge yet on top of those backlogged patients, many of whom are sicker than usual because their health care had to be deferred. Even with hundreds of new patients with lung cancer, asthma, and other respiratory diseases waiting for care in outpatient settings, Coulter still has to cancel his clinics because “I have to be in the hospital all the time,” he said.

Many health-care workers have had enough. Some who took on extra shifts during past surges can’t bring themselves to do so again. Some have moved to less stressful positions that don’t involve treating COVID-19. Others are holding the line, but only just. “You can’t pour from an empty cup, but with every shift it feels like my co-workers and I are empty,” Montgomery said. “We are still trying to fill each other up and keep going.”

The grueling slog is harder now because it feels so needless, and because many patients don’t realize their mistake until it’s too late. On Tuesday, Hill spoke with an elderly man who had just been admitted and was very sick. “He said, ‘I’m embarrassed that I’m here,’” she told me. “He wanted to talk about the vaccine, and in the back of my mind I’m thinking, You have a very high likelihood of not leaving the hospital.” Other patients remain defiant. “We had someone spit in a nurse’s eye because she told him he had COVID and he didn’t believe her,” Edwards said.

Some health-care workers are starting to resent their patients—an emotion that feels taboo. “You’re just angry,” Coulter said, “and you feel guilty for getting angry, because they’re sick and dying.” Others are indignant on behalf of loved ones who don’t already have access to the vaccines. “I’m a mom of a 1-year-old and a 4-year-old, and the daughter of family members in Zimbabwe and South Africa who can’t get vaccinated yet,” says Matifadza Hlatshwayo Davis, who works at a Veterans Affairs hospital in St. Louis. “I’m frustrated, angry, and sad.”

“I don’t think people get that once you become sick enough to be hospitalized with COVID, the medications and treatments that we have are, quite frankly, not very good,” says Howard Jarvis, the medical director of Cox South’s emergency department. Drugs such as dexamethasone offer only incremental benefits. Monoclonal antibodies are effective only during the disease’s earliest stages. Doctors can give every recommended medication, and patients still have a high chance of dying. The goal should be to stop people from getting sick in the first place.

But Missouri Governor Mike Parson never issued a statewide mask mandate, and the state’s biggest cities—Kansas City, St. Louis, Springfield, and Columbia—ended their local orders in May, after the CDC said that vaccinated people no longer needed to wear masks indoors. In June, Parson signed a law that limits local governments’ ability to enact public-health restrictions. And even before the pandemic, Missouri ranked 41st out of all the states in terms of public-health funding. “We started in a hole and we’re trying to catch up,” Towns, the director of the Springfield–Greene County Health Department, told me.

Her team flattened last year’s curve through testing, contact tracing, and quarantining, but “Delta has just decimated our ability to respond,” Kendra Findley, the department’s administrator for community health and epidemiology, told me. The variant is spreading too quickly for the department to keep up with every new case, and more people are refusing to cooperate with contact tracers than at this time last year. The CDC has sent a “surge team” to help, but it’s just two people: an epidemiologist, who is helping analyze data on Delta’s spread, and a communications person. And like Springfield’s hospitals, the health department was already overwhelmed with work that had been put off for a year. “Suddenly, I feel like there aren’t enough hours in the day,” Findley said.

Early last year, Findley stuck a note on her whiteboard with the number of people who died in the 1918 flu pandemic: 50 million worldwide and 675,000 in the U.S. “It was for perspective: We will not get here. You can manage this,” she told me. “I looked at it the other day and I think we’re going to get there. And I feel like a large segment of the population doesn’t care.”

The 1918 flu pandemic took Missouri by surprise too, says Carolyn Orbann, an anthropologist at the University of Missouri who studies that disaster. While much of the world felt the brunt of the pandemic in October 1918, Missouri had irregular waves with a bigger peak in February 1920. So when COVID-19 hit, Orbann predicted that the state might have a similarly drawn-out experience. Missouri has a widely dispersed population, divided starkly between urban and rural places, and few highways—a recipe for distinct and geographically disparate microcultures. That perhaps explains why new pathogens move erratically through the state, creating unpredictable surges and, in some pockets, a false sense of security. Last year, “many communities may have gone through their lockdown period without registering a single case and wondered, What did we do that for?” Orbann told me.

She also suspects that Missourians in 1918 might have had a “better overhead view of the course of the pandemic in their communities than the average citizen has now.” Back then, the state’s local papers published lists of people who were sick, so even those who didn’t know anyone with the flu could see that folks around them were dying. “It made the pandemic seem more local,” Orbann said. “Now, with fewer hometown newspapers and restrictions on sharing patient information, that kind of knowledge is restricted to people working in health care.”

Montgomery, the CoxHealth nurse, feels that disparity whenever she leaves the hospital. “I work in the ICU, where it’s like a war zone, and I go out in public and everything’s normal,” she said. “You see death and suffering, and then you walk into the grocery store and get resistance. It feels like we’re being ostracized by our community.”

If anything, people in the state have become more entrenched in their beliefs and disbeliefs than they were last year, Davis, the St. Louis–based doctor, told me. They might believe that COVID-19 has been overblown, that young people won’t be harmed, or that the vaccines were developed too quickly to be safe. But above all else, “what I predominantly get is, ‘I don’t want to talk to you about that; let’s move on,’” Davis said.

People take the pandemic seriously when they can see it around them. During past surges in other parts of the U.S., curves flattened once people saw their loved ones falling ill, or once their community became the unwanted focus of national media coverage. The same feedback loop might be starting to occur in Missouri. The major Route 66 Festival has been canceled. More people are making vaccine appointments at both Cox South and Mercy.

In Springfield, the public-health professionals I talked with felt that they had made successful efforts to address barriers to vaccine access, and that vaccine hesitancy was the driving force of low vaccination rates. Improving those rates is now a matter of engendering trust as quickly as possible. Springfield’s firefighters are highly trusted, so the city set up vaccine clinics in local fire stations. Community-health advocates are going door-to-door to talk with their neighbors about vaccines. The Springfield News-Leader is set to publish a full page of photos of well-known Springfieldians who are advocating for vaccination. Several local pastors have agreed to preach about vaccines from their pulpits and set up vaccination events in their churches. One such event, held at James River Church on Monday, vaccinated 156 people. “Once we got down to the group of hesitant people, we’d be happy if we had 20 people show up to a clinic,” says Cora Scott, Springfield’s director of public information and civic engagement. “To have 156 people show up in one church in one day is phenomenal.”

But building trust is slow, and Delta is moving fast. Even if the still-unvaccinated 55 percent of Missourians all got their first shots tomorrow, it would still take a month to administer the second ones, and two weeks more for full immunity to develop. As current trends show, Delta can do a lot in six weeks. Still, “if we can get our vaccination levels to where some of the East Coast states have got to, I’ll feel a lot better going into the fall,” Frederick, Mercy’s chief administrative officer, said. “If we plateau again, my fear is that we will see the twindemic of flu and COVID.”

In the meantime, southwest Missouri is now a cautionary tale of what Delta can do to a largely unvaccinated community that has lowered its guard. None of Missouri’s 114 counties has vaccinated more than 50 percent of its population, and 75 haven’t yet managed more than 30 percent. Many such communities exist around the U.S. “There’s very few secrets about this disease, because the answer is always somewhere else,” Edwards said. “I think we’re a harbinger of what other states can expect.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

quaranmemes for quarantines

I was tagged by @sparksearcher, thanks, this is a good one. It’s also a long one, so apologies to mobile users and for the rest of you:

when was the last time you left your home?

We took a drive yesterday but only got out of the car once, at a local farm stand. The pig smell was ripe and there were eight other people milling around so we got back in the car immediately. My last time inside a place of business was on the 13th, a stock-up trip to Aldi. Everyone was wearing a mask and they were controlling the number of shoppers with a “one in, one out” method. I don’t anticipate another grocery run for a few weeks.

what was the last thing you bought?

It was an onlline order of a 10-pack of washable cotton masks just this morning. I’ve crocheted some nifty washable masks using dishcloth yarn but without filter material they’re useless because of the holes in the work. But I think a combo of a crocheted mask with a filter and a cotton cloth mask would be effective.

is quarantine driving you insane or are you finally relaxed?

My brain is a jerk. I’m an introvert plus I’m agoraphobic so I’ve never minded staying home. It’s cozy and safe. Now that I can’t go anywhere, I literally want to go ALL OF THE PLACES ALL OF THE TIME. I’ve been having a tough time emotionally because everything feels dangerous now and I worry constantly...about my older high-risk husband, about my elderly parents, about my teenager’s future and on and on.

who are you spending quarantine with?

Russ, when he’s not scheduled to work, and Zack.

do you have pets to keep you company?

I don’t and honestly? I’m happy to not have a pet right now. I’m sure they provide welcome comfort but It’s stressful enough trying to make sure there are enough food and supplies in the house for the three of us plus making sure my elderly parents are provided for without having to plan bulk-buying trips for pet food and other things. I get to see Buddy and Bonnie next door and Paco and Lucky across the street plus it’s baby squirrel and baby bunny season in the garden.

what are your current responsibilities?

Planning meals, planning shopping trips, bulk cooking so we have freezer meals available just in case, keeping an eye on Zack with his online classes since he’s not feeling particularly motivated atm, lots of laundry when Russ is working, cleaning and sanitizing the house, planting and maintaining our flower, vegetable and herb gardens, keeping on top of the budget, making sure bills are paid, trying to keep in touch with friends and family and trying to keep my sanity. I am succeeding at only a few of these.

do you have a room to yourself?

Guest bedroom sometimes when Zack isn’t using it for online class. I’ve mainly been escaping to our unfinished basement because I love it down there. We have bookcases and chairs and lamps and an area rug and a super old TV/VHS combo and it’s always cool and quiet. I do my workouts or listen to podcasts and crochet or put in some ridiculous old movie from our VHS collection and just escape for a while.

are you exercising?

Some? Whatever viral thing I had in March caused a major POTS flare so my heart rate dictates how much I can exercise each day. Right now my O2 sat is hanging in around 94% and my resting pulse rate is in the 90s, sometimes the low 100s, so I have to pace myself. Just walking around can spike it to the 130s. I can’t do my favorite 90s workout MTV: THE GRIND, sad face. So it’s yoga or recumbent bike for now.

town, country, city?

We’re a city, population around 14,000, but in reality we’re a suburb of St. Louis.

how’s your toilet paper supply?

We’re wealthy. I started getting nervous about coronavirus back in the middle of February so every time I went shopping I picked up another pack. I didn’t hoard, just made sure I bought extra so we have about 45 rolls in the house right now.

what’s the worst thing that you had to cancel?

Two in-state college visits and one out-of-state visit. We’ve been planning and saving money for almost a year and had to cancel them all. Zack isn’t sure he wants to reschedule because he doesn’t know what the college experience will realistically look like for him in 2021. Which is logical but I’m still sad.

what’s the best thing you’ve had to cancel?

Dental work. It’s necessary but not emergent so it’s not being rescheduled until later this summer.

who do you miss the most?

This will sound perverse, because they’re the two people who drive me the absolute bat-shit craziest, but I miss visiting my parents. They won’t call me, refuse to let me shop for them, do not come to the door when I drop off whatever supplies I’m assuming they need and wouldn’t think of driving by our house even though we live less than a mile apart. I’ve not actually seen them since the end of February so I have no idea how they’re doing. They could be dead or hospitalized for all I know.

do you have any new hobbies?

Hell, no. I’m neglecting the few hobbies I have, I’m not thinking of new ones. What would I do? Learn a language, learn to play an instrument? I’m lucky if I remember to take a shower every day.

what are you watching the most?

I can’t watch scripted TV or movies right now because I sit there and think “I'm watching celebrities who make more money than I will ever have in my life and they’re safe from the pandemic so FUCK THEM” which kind of gets in the way of my enjoyment. I signed up for Ovid TV because I love documentaries but I can’t watch those, either. The pandemic is an emotional overlay of everything I try to consume right now, visual or written, so I’ve been going back and re-watching everything on LGR’s YouTube channel, especially the Sims Let’s Play videos. His Duke Nukem voice and the stupid shit he does like creating Fartwhistle Dingleprop and his Hat of Shame or putting the Sims’ toilet in the middle of a hedge maze hits the right spot for me now.

are you still going to work?

I’ve been out of work a long time. Russ is still working since he works for a public utility, at an evil, evil coal-burning power plant but hey, the electricity has to be generated somehow. The other options are nuclear, but Callaway scares the shit out of most Missourians and no one wants to pay the increased rates for green energy, so here we are. His team has been divided in three and they rotate three 12-hour days in a row and then seven or eight days off in between. He’s getting his full pay and I am enormously grateful.

what are you out of?

We’re honestly okay on everything. I started stocking up in mid-February, bought a chest freezer and filled it up and made sure we had plenty of everyone’s shelf-stable favorites. Plus I stocked up on paper towels and disinfecting wipes and hand soap and toiletries. I’m starting to get a little low on eggs but a local restaurant is selling grocery items during the shutdown so I can get a flat when I need them.

have you made any changes to your hair during quarantine?

Nope. I’m allergic to hair dye and my stylist hasn’t found a formulation yet that works for me and I’m not messing with henna. So it’s the same old gray + mousy brown. It’s lovely. I’m letting my hair grow because my emotional state is precarious enough. If I do a hack job with kitchen scissors and cringe every time I look in the mirror, that’s not helping. It’s about an inch past my shoulders now and my fringe is long enough to be swept to the side but I have to hold it in place with barrettes because it’s heavy so I look like a sad old scene girl.

tagging: @this-lioness, @englishsongbird, @veradune, @maresdotes, @impreciselanguage, @stackcats, @resting-meme-face, @buddhish and seriously, all my mutuals because I want to read your answers but I’m having trouble remembering usernames or I remember them but I can’t spell the damn things and I just don’t have the energy to look anyone up, please forgive me.

#personal#meme#ask game#not a game really#but nice and distracting for about an hour#thanks#tag me if you do this please

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Planes, Trains, and Automobiles

Since I know y’all are dying to hear what I was up to in the brief period of time Taylor and I were apart -

I started my illogical series of journeys back and forth across the country with an Amtrak ride to Missouri on the Southwest Chief. Luckily, the checked baggage is not a myth and I was able to give them my heavy suitcases and not worry about them again til Kansas City.

The train was almost full (we had a herd of tween Boy Scouts join us somewhere in New Mexico), so I had an older lady in the seat next to me the whole time. She came in with pretty chaotic energy, playing videos on her phone with no headphones (something that I quickly realized drives me insane lol) and ended by taking her pills with a Red Bull and telling me way too much about her family history at about 6:30 in the morning.

During the daylight part of the trip I took over a table in the observation car and just looked out the window and did a bunch of watercoloring. Very chill.

We still had to wear masks for the whole ride which made it a little difficult to sleep, but got used to it after a awhile.

After two full days on the train, I got to KC and hung out with my family for a few days. So nice to see everyone again, but it makes me sad that my grandparents once again don’t feel safe going to very many of places because of covid. Even though they regularly disagree with the beliefs and policies of their conservative neighbors and the governor, I’ve never seen them or my mom so frustrated and angry with their fellow Missourians. People in my hometown continue not to wear masks in public spaces and the vaccination rate for adults is hovering at around 40%. One of my grandparents’ friends was hospitalized for 18 days after going on a trip with one of his so-called friends who lied about being vaccinated. The unvaccinated man later died of covid.

But anyway, nothing new to say on that front, I know I’m generally preaching to the choir. Just can’t really leave that part of the picture out when it’s so ever present (especially since my grandma keeps the TV local news on all day lol).

Luckily, we were still able to do most of our usual activities - going on walks where the air feels thick enough to cut and listening to the buzz of the cicadas (or locusts, are they the same thing?), eating zucchini muffins, talking about traffic and new businesses in town, and watching Law and Order SVU.

After only a few days with promises to return soon, I headed out on a bus (Jefferson Lines aka midwestern Greyhound I guess?), to Minneapolis to meet up with Taylor. Looking back, choosing the 10 hour bus ride instead of an hour and a half long flight to save a little money didn’t make the most sense. However, I just entered the TikTok time warp and the hours flew by.

On one of our short breaks, almost everyone got off to get food from Burger King. I stayed on since I was supplied with muffins and planning on eating dinner with Taylor. The girl sitting behind me noticed I didn’t get off and offered me some of her food, which I declined but thought was really sweet of her. Inspires me to be a bit more generous and perceptive of people’s needs.

0 notes

Photo

Special education students find extra challenges in home learning

May 4, 2020 for the Columbia Missourian

Before the pandemic, Tara Arnett’s two children, Logan, 10, and Reagan, 8, went to public school like most kids in Columbia.

Logan, who has autism, was in his special education class, and Reagan, who received speech therapy, attended four sessions a week. After school, they rode the bus to day care and got picked up about 5 p.m., when Arnett was done with work.

Now, like many parents, Arnett, 37, juggles taking care of her kids while she and her husband work full time amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

She works from home, allowing her more time with her children, but Logan needs more than just worksheets and Reagan misses out on practicing speech.

As Columbia Public Schools fine-tunes remote learning, some students in special education and their families feel lost in the reshuffle.

Nearly 2,000 of the district’s more than 19,000 students have learning disabilities. Depending on the severity of the disability, these students may face challenges more acutely.

Difficulties include moving their learning environments home, losing access to therapy and classroom materials, and regressing in what they know and how they behave.

When the district first announced that school buildings would close, elementary school students were sent home with a two-week packet of activities. Students in sixth through 12th grades were also offered activities through online platforms such as Schoology.

McKenzie Skoog, a special education teacher at Parkade Elementary School, had two days to put her packets together because she learned about the district’s closures when everyone else did.

She said she did her best to prepare worksheets that would exercise students’ skills but that she knew they would be closer to review or busy work.

“My goal was to give something that would be helpful to try to not lose skills over the break,” Skoog said.

‘School is school, home is home’

The classroom environment seems vital for many students with special needs.

Erica Lembke, department chair of special education in MU’s College of Education, said the classroom is more than just a classroom for students with special needs: There’s relationship building, communication and socialization training, behavioral modeling and other aspects teachers embed into daily learning.

“For our kids who have more significant needs, it’s even things like mobility and toilet training,” Lembke said. “It can’t be addressed just through packets of worksheets.”

Arnett’s son, fifth-grader Logan, has autism and needs one-on-one attention when it comes to schoolwork. He also struggles with discerning environments.

“School is school, home is home, and crossing those over is not something that he necessarily is ready to do,” Arnett said.

When Skoog was still in the classroom, she found that when her students struggled with learning difficult subjects, it sometimes elicited negative behavior. She said while she’s trained in how to navigate that, some parents aren’t.

“A lot of times kids act differently at school than at home,” she said. “It’s like, ‘My parent is now my teacher, so how do I sit down and do work that’s hard for me with my mom or dad?’”

Another challenge is that critical resource providers like speech, occupational or physical therapists are no longer able to work in person with their students. Their particular lessons are harder to replicate online, since so much of their work is hands-on.

Arnett said Logan’s specialists help him maximize his efficiency, and while she does her best to work with him, she isn’t the perfect replacement for a trained educator. Reagan’s speech therapists provided exercises, but she hasn’t had a meeting since school closed.

“I’m a mom and not a teacher,” she said.

Alyse Monsees, director of special services in the district, said special education teachers have been working with families to figure out how to continue building on what students already know.

“We’re making sure we’re not asking parents to work on new skills,” she said. “We’re encouraging our teachers to figure out what the parents want or what they’re ready for.”

She said educators have been working with parents on how to adapt lessons learned in class, with the resources and materials teachers have, to what can be learned at home. For example, if students are learning how to sort, they can do so by separating laundry or even kitchen utensils, Monsees said.

Monsees said teachers have been providing families with supplemental activities like scavenger hunts for shapes around the house, links to story time and songs online and even sending home activity bags.

‘A pandemic-induced slump’

Zoom, an online video conference app, has been a mainstay for educators and families to keep in touch and hold classes. The needs of special education students vary, making it difficult for classes to organize.

For example, Skoog said her students can Zoom with their regular classes, but she’s unable to bring them all together in a Zoom session of her own due to confidentiality policies in special education.

Instead, she keeps in touch through emails, postcards and phone calls.

“Individually and selfishly, I’m sad I don’t get to see (my students),” she said. “I miss them.”

Jessica Bock, a student teacher at Battle High School, said her special education class meets via Zoom twice a week for 30 minutes. She said some students are excited to get on Zoom, while others miss school and don’t understand the change.

“Nothing beats being at school, where it’s a social outlet for kids,” Bock said.

Individual Education Program meetings, which keep special needs students on track toward their goals for the year, are still happening via Zoom or phone call, Monsees said.

Because in-person classes are canceled for the rest of the academic year as well as summer school, the summer slump — the regression of skills students experience over a long break away from school — seems inevitable. It might impact students with special needs harder.

“This is a pandemic-induced slump,” Lembke said. “Teachers in the fall will have to work even harder to get back those skills.”

Students in transitional IEPs (from middle to high school, for example) may be feeling a little lost, Lembke said. “These are critical months for them,” she said.

Monsees said IEP teams and the district were waiting to hear from the state on what compensatory learning for students with special needs will look like.

“We’re still looking for guidance as we navigate these waters,” she said. “This is more than just one student who may need compensatory services; it’s the nation.”

To persevere against the difficulties of learning from home, Arnett said she and her family set aside time for fun. When it’s warm enough outside, they’ll go for a swim. They take long walks. Inside, they play video games together.

Second-grader Reagan took up learning how to ride a bike, even though Arnett said she was reluctant to try before.

“There are other things to learn and to concentrate on,” Arnett said. “There are other things we can get out of this situation that don’t necessarily have to do with homework.”

In making decisions, the district’s No. 1 priority is the health, safety and well-being of everyone, Monsees said.

“Academics are important, but that’s at the forefront,” she said.

“Are my families safe, are they healthy, do they have food to eat?” Skoog said. “On top of that, if you get work done, that’s a bonus.”

0 notes