#scythian chieftain

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

With my latest acquisitions from @pangur-and-grim my messenger bag pin collection grows ever stronger

#i think fully half of these pins are from greer stothers' shop actually#and then there's some mcelroys and isabelle and eevee and the bee pin that duck got for me#pins#pin collection#mod post#scythian chieftain#siberian ice maiden

336 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm doing research on Drago Bludvist's origin right now.

And I just realized he could very well be interpreted to be from the Balkans. Ergo my country (I'm Bulgarian).

Allow me to explain.

Not only am I an absolute idiot for forgetting that Drago is such a common name in my country, but according to the Art of How to Train Your Dragon 2 his clothing and general features were based on Slavic and Asian origin. Both of which are heavily present in Bulgarian culture, the nation was created by both Slavic and Proto-Bulgarian tribes in 681 AD and the Proto-Bulgarians can be traced back to Central Asia.

Their tribes were called by early medieval chroniclers with different names such as: Bulgarians, Kutrigurs, Utigurs, Scythians, Mizis, Huns, etc. And their main choice of arms, as attested by both early artworks and chronicles, was the spear (which we can see is also reminiscent of Drago's weapon which doubles as a spear and a bullhook).

I know Drago was designed to be as racially ambiguous as possible to further the idea that he is well traveled and from a far-away land in comparison to the Vikings of Berk but even the Mediterranean and Northern African influences in his design put him like... Right in that sweet spot that is the Balkans.

The Balkan Peninsula homes multiple Mediterranean countries and is precisely ONE sea away from Northern Africa.

The name is something I'm particularly frustrated about, because I have had so many friends called Drago in my life, or Dragan, Draga, Dragomir, Dragoslav 😭

Here you got one Drago Bludvist:

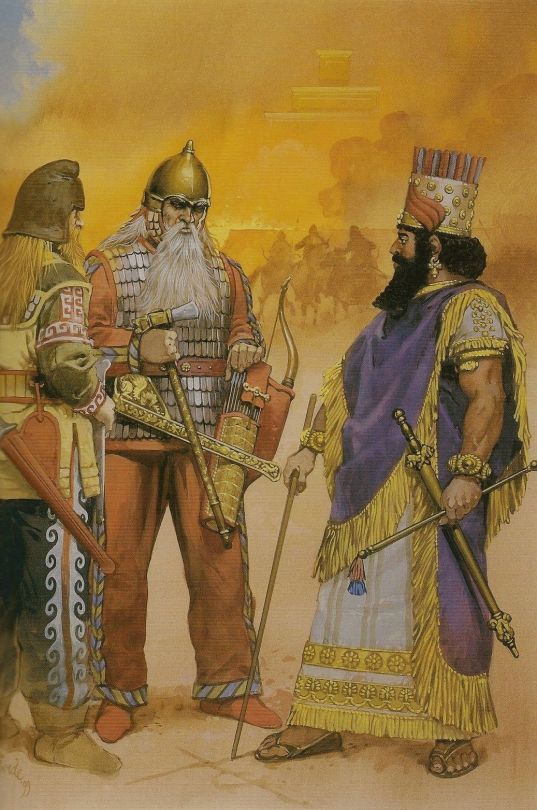

And here you got Proto-Bulgarians:

This is a depiction of a victorious warrior with Turanid features, depicted on a vessel from the Golden Hoard of Nad St. Miklos of presumed Proto-Bulgarian origin:

My history teachers would be so disappointed in me.

Even his complexion can be attributed to the fact that Proto-Bulgarians had significantly darker skin tones. Historical accounts from the 7th century delineate that Proto-Bulgarians integrated with the Slavs (which were predominantly fair, blue-eyed and blonde), and through the unification of those two demographics, the Bulgarian nation as it is today was created.

I'm legit excited to be able to incorporate some of my culture into my interpretation of Drago Bludvist. And I'm saying 'my interpretation' because I fully recognize people are free to analyse and present his origin as they see fit, considering that DreamWorks never specified that part of his backstory.

But with how many similarities I have discovered today with my culture I am very excited to see how I can weave it into my work.

Bonus fact: Between the 8th and the 9th century (a couple hundred years after the merging of Slavs and Proto-Bulgarians) in Medieval Bulgaria reigned a Chieftain, Khan Krum a.k.a. Krum the Horrible, who made a fucking chalice out of the Byzantine Emperor Nicephoros's skull after defeating him in the battle of Pliska. Which is very Drago Bludvist if you ask me.

Mind you, this is actually referenced by Johann in RTTE. So technically Bulgaria's canon in HTTYD😂 Which would even further reinforce the Drago being Proto-Bulgarian/Bulgarian theory.

"There hasn't been destruction like this since Emperor Nicephorus and the Byzantines were mercilessly annihilated in the Battle of Pliska. They say that Khan Krum had Nicephorus' skull encased in silver and drank mead from it." JOHANN SEEING THE STATE OF DRAGON’S EDGE SINCE THE ERUPTION.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

#卍TENGRÎkutUluğBaşBuğAttilahun

5th-century ruler of the Hunnic Empire

"#Atilla" and "Attila the #Hun" redirect here. For other uses, see Attila (disambiguation), Atilla (disambiguation), and Attila the Hun (disambiguation).

#Attila (/əˈtɪlə/, /ˈætələ/;fl. c. 406–453), frequently called Attila the Hun, was the ruler of the Huns from 434 until his death in March 453. He was also the leader of a tribal empire consisting of Huns, Ostrogoths, Alans and Bulgars, among others, in Central and Eastern Europe.

Quick Facts King and chieftain of the Hunnic Empire, Reign ...

During his reign, he was one of the most feared enemies of the Western and Eastern Roman Empires. He crossed the Danubetwice and plundered the Balkans, but was unable to take Constantinople. His unsuccessful campaign in Persia was followed in 441 by an invasion of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, the success of which emboldened Attila to invade the West. He also attempted to conquer Roman Gaul (modern France), crossing the Rhine in 451 and marching as far as Aurelianum (Orléans) before being stopped in the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains.

He subsequently invaded Italy, devastating the northern provinces, but was unable to take Rome. He planned for further campaigns against the Romans, but died in 453. After Attila's death, his close adviser, Ardaricof the Gepids, led a Germanic revolt against Hunnic rule, after which the Hunnic Empire quickly collapsed. Attila would live on as a character in Germanic heroic legend.

Appearance and character

BildMór Than's 19th century painting of The Feast of Attila, based on a fragment of Priscus

There is no surviving first-hand account of Attila's appearance, but there is a possible second-hand source provided by Jordanes, who cites a description given by Priscus.

He was a man born into the world to shake the nations, the scourge of all lands, who in some way terrified all mankind by the dreadful rumors noised abroad concerning him. He was haughty in his walk, rolling his eyes hither and thither, so that the power of his proud spirit appeared in the movement of his body. He was indeed a lover of war, yet restrained in action, mighty in counsel, gracious to suppliants and lenient to those who were once received into his protection. Short of stature, with a broad chest and a large head; his eyes were small, his beard thin and sprinkled with grey; and he had a flat nose and swarthy skin, showing evidence of his origin.:182–183

Some scholars have suggested that this description is typically East Asian, because it has all the combined features that fit the physical type of people from Eastern Asia, and Attila's ancestors may have come from there.:202 Other historians also believed that the same descriptions were also evident on some Scythian people.

Etymology

BildA painting of Attila riding a pale horse, by French Romantic artist Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863)

Many scholars have argued that the name Attila derives from East Germanic origin; Attila is formed from the Gothic or Gepidic noun atta, "father", by means of the diminutive suffix -ila, meaning "little father", compare Wulfilafrom wulfs "wolf" and -ila, i.e. "little wolf".:386:29:46The Gothic etymology was first proposed by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm in the early 19th century.:211 Maenchen-Helfen notes that this derivation of the name "offers neither phonetic nor semantic difficulties",:386 and Gerhard Doerfer notes that the name is simply correct Gothic.:29 Alexander Savelyev and Choongwon Jeong (2020) similarly state that Attila's name "must have been Gothic in origin." The name has sometimes been interpreted as a Germanization of a name of Hunnic origin.:29–32

Other scholars have argued for a Turkic origin of the name. Omeljan Pritsak considered Ἀττίλα (Attíla) a composite title-name which derived from Turkic *es (great, old), and *til (sea, ocean), and the suffix /a/.:444The stressed back syllabic tilassimilated the front member es, so it became *as.:444 It is a nominative, in form of attíl- (< *etsíl < *es tíl) with the meaning "the oceanic, universal ruler".:444 J. J. Mikkola connected it with Turkic āt (name, fame).:216 As another Turkic possibility, H. Althof (1902) considered it was related to Turkish atli (horseman, cavalier), or Turkish at (horse) and dil(tongue).:216 Maenchen-Helfen argues that Pritsak's derivation is "ingenious but for many reasons unacceptable",:387 while dismissing Mikkola's as "too farfetched to be taken seriously".:390 M. Snædal similarly notes that none of these proposals has achieved wide acceptance.:215–216Criticizing the proposals of finding Turkic or other etymologies for Attila, Doerfer notes that King George VI of the United Kingdom had a name of Greek origin, and Süleyman the Magnificent had a name of Arabic origin, yet that does not make them Greeks or Arabs: it is therefore plausible that Attila would have a name not of Hunnic origin.:31-32 Historian Hyun Jin Kim, however, has argued that the Turkic etymology is "more probable".:30

M. Snædal, in a paper that rejects the Germanic derivation but notes the problems with the existing proposed Turkic etymologies, argues that Attila's name could have originated from Turkic-Mongolian at, adyy/agta(gelding, warhorse) and Turkish atli (horseman, cavalier), meaning "possessor of geldings, provider of warhorses".:216–217

Historiography and source

BildFigure of Attila in a museum in Hungary

The historiography of Attila is faced with a major challenge, in that the only complete sources are written in Greek and Latin by the enemies of the Huns. Attila's contemporaries left many testimonials of his life, but only fragments of these remain.:25Priscus was a Byzantine diplomat and historian who wrote in Greek, and he was both a witness to and an actor in the story of Attila, as a member of the embassy of Theodosius II at the Hunnic court in 449. He was obviously biased by his political position, but his writing is a major source for information on the life of Attila, and he is the only person known to have recorded a physical description of him. He wrote a history of the late Roman Empire in eight books covering the period from 430 to 476.

Only fragments of Priscus' work remain. It was cited extensively by 6th-century historians Procopius and Jordanes,:413especially in Jordanes' The Origin and Deeds of the Goths, which contains numerous references to Priscus's history, and it is also an important source of information about the Hunnic empire and its neighbors. He describes the legacy of Attila and the Hunnic people for a century after Attila's death. Marcellinus Comes, a chancellor of Justinianduring the same era, also describes the relations between the Huns and the Eastern Roman Empire.:30

Numerous ecclesiastical writings contain useful but scattered information, sometimes difficult to authenticate or distorted by years of hand-copying between the 6th and 17th centuries. The Hungarian writers of the 12th century wished to portray the Huns in a positive light as their glorious ancestors, and so repressed certain historical elements and added their own legends.:32

The literature and knowledge of the Huns themselves was transmitted orally, by means of epics and chanted poems that were handed down from generation to generation.:354Indirectly, fragments of this oral history have reached us via the literature of the Scandinavians and Germans, neighbors of the Huns who wrote between the 9th and 13th centuries. Attila is a major character in many Medieval epics, such as the Nibelungenlied, as well as various Eddas and sagas.:32:354

Archaeological investigation has uncovered some details about the lifestyle, art, and warfare of the Huns. There are a few traces of battles and sieges, but the tomb of Attila and the location of his capital have not yet been found.:33–37

Early life and background

Main article: Huns

BildHuns in battle with the Alans. An 1870s engraving after a drawing by Johann Nepomuk Geiger (1805–1880 ).

The Huns were a group of Eurasian nomads, appearing from east of the Volga, who migrated further into Western Europec. 370 and built up an enormous empire there. Their main military techniques were mounted archery and javelinthrowing. They were in the process of developing settlements before their arrival in Western Europe, yet the Huns were a society of pastoral warriors:259 whose primary form of nourishment was meat and milk, products of their herds.

The origin and language of the Huns has been the subject of debate for centuries. According to some theories, their leaders at least may have spoken a Turkic language, perhaps closest to the modern Chuvash language.:444 One scholar suggests a relationship to Yeniseian.According to the Encyclopedia of European Peoples, "the Huns, especially those who migrated to the west, may have been a combination of central Asian Turkic, Mongolic, and Ugricstocks".

Attila's father Mundzuk was the brother of kings Octar and Ruga, who reigned jointly over the Hunnic empire in the early fifth century. This form of diarchy was recurrent with the Huns, but historians are unsure whether it was institutionalized, merely customary, or an occasional occurrence.:80 His family was from a noble lineage, but it is uncertain whether they constituted a royal dynasty. Attila's birthdate is debated; journalist Éric Deschodt and writer Herman Schreiber have proposed a date of 395.However, historian Iaroslav Lebedynsky and archaeologist Katalin Escher prefer an estimate between the 390s and the first decade of the fifth century.:40Several historians have proposed 406 as the date.:92:202

Attila grew up in a rapidly changing world. His people were nomads who had only recently arrived in Europe. They crossed the Volga river during the 370s and annexed the territory of the Alans, then attacked the Gothic kingdom between the Carpathian mountains and the Danube. They were a very mobile people, whose mounted archers had acquired a reputation for invincibility, and the Germanic tribes seemed unable to withstand them.:133–151 Vast populations fleeing the Huns moved from Germania into the Roman Empire in the west and south, and along the banks of the Rhine and Danube. In 376, the Goths crossed the Danube, initially submitting to the Romans but soon rebelling against Emperor Valens, whom they killed in the Battle of Adrianople in 378.:100 Large numbers of Vandals, Alans, Suebi, and Burgundians crossed the Rhineand invaded Roman Gaul on December 31, 406 to escape the Huns.:233 The Roman Empire had been split in half since 395 and was ruled by two distinct governments, one based in Ravenna in the West, and the other in Constantinople in the East. The Roman Emperors, both East and West, were generally from the Theodosian family in Attila's lifetime (despite several power struggles).:13

The Huns dominated a vast territory with nebulous borders determined by the will of a constellation of ethnically varied peoples. Some were assimilated to Hunnic nationality, whereas many retained their own identities and rulers but acknowledged the suzerainty of the king of the Huns.:11 The Huns were also the indirect source of many of the Romans' problems, driving various Germanic tribes into Roman territory, yet relations between the two empires were cordial: the Romans used the Huns as mercenaries against the Germans and even in their civil wars. Thus, the usurper Joanneswas able to recruit thousands of Huns for his army against Valentinian III in 424. It was Aëtius, later Patrician of the West, who managed this operation. They exchanged ambassadors and hostages, the alliance lasting from 401 to 450 and permitting the Romans numerous military victories.:111 The Huns considered the Romans to be paying them tribute, whereas the Romans preferred to view this as payment for services rendered. The Huns had become a great power by the time that Attila came of age during the reign of his uncle Ruga, to the point that Nestorius, the Patriarch of Constantinople, deplored the situation with these words: "They have become both masters and slaves of the Romans".:128

Campaigns against the Eastern Roman Empire

BildThe Empire of the Huns and subject tribes at the time of Attila

The death of Rugila (also known as Rua or Ruga) in 434 left the sons of his brother Mundzuk, Attila and Bleda, in control of the united Hun tribes. At the time of the two brothers' accession, the Hun tribes were bargaining with Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II's envoys for the return of several renegades who had taken refuge within the Eastern Roman Empire, possibly Hunnic nobles who disagreed with the brothers' assumption of leadership.

The following year, Attila and Bleda met with the imperial legation at Margus (Požarevac), all seated on horseback in the Hunnic manner, and negotiated an advantageous treaty. The Romans agreed to return the fugitives, to double their previous tribute of 350 Roman pounds (c. 115 kg) of gold, to open their markets to Hunnish traders, and to pay a ransom of eight solidi for each Roman taken prisoner by the Huns. The Huns, satisfied with the treaty, decamped from the Roman Empire and returned to their home in the Great Hungarian Plain, perhaps to consolidate and strengthen their empire. Theodosius used this opportunity to strengthen the walls of Constantinople, building the city's first sea wall, and to build up his border defenses along the Danube.

The Huns remained out of Roman sight for the next few years while they invaded the Sassanid Empire. They were defeated in Armenia by the Sassanids, abandoned their invasion, and turned their attentions back to Europe. In 440, they reappeared in force on the borders of the Roman Empire, attacking the merchants at the market on the north bank of the Danube that had been established by the treaty of 435.

Crossing the Danube, they laid waste to the cities of Illyricumand forts on the river, including (according to Priscus) Viminacium, a city of Moesia. Their advance began at Margus, where they demanded that the Romans turn over a bishop who had retained property that Attila regarded as his. While the Romans discussed the bishop's fate, he slipped away secretly to the Huns and betrayed the city to them.

While the Huns attacked city-states along the Danube, the Vandals (led by Geiseric) captured the Western Roman province of Africa and its capital of Carthage. Carthage was the richest province of the Western Empire and a main source of food for Rome. The Sassanid ShahYazdegerd II invaded Armenia in 441.[citation needed]

The Romans stripped the Balkan area of forces, sending them to Sicily in order to mount an expedition against the Vandals in Africa. This left Attila and Bleda a clear path through Illyricum into the Balkans, which they invaded in 441. The Hunnish army sacked Margus and Viminacium, and then took Singidunum (Belgrade) and Sirmium. During 442, Theodosius recalled his troops from Sicily and ordered a large issue of new coins to finance operations against the Huns. He believed that he could defeat the Huns and refused the Hunnish kings' demands.

Attila responded with a campaign in 443. For the first time (as far as the Romans knew) his forces were equipped with battering rams and rolling siege towers, with which they successfully assaulted the military centers of Ratiara and Naissus (Niš) and massacred the inhabitants. Priscus said "When we arrived at Naissus we found the city deserted, as though it had been sacked; only a few sick persons lay in the churches. We halted at a short distance from the river, in an open space, for all the ground adjacent to the bank was full of the bones of men slain in war."

Advancing along the Nišava River, the Huns next took Serdica (Sofia), Philippopolis (Plovdiv), and Arcadiopolis (Lüleburgaz). They encountered and destroyed a Roman army outside Constantinople but were stopped by the double walls of the Eastern capital. They defeated a second army near Callipolis (Gelibolu).

Theodosius, unable to make effective armed resistance, admitted defeat, sending the Magister militum per OrientemAnatolius to negotiate peace terms. The terms were harsher than the previous treaty: the Emperor agreed to hand over 6,000 Roman pounds (c. 2000 kg) of gold as punishment for having disobeyed the terms of the treaty during the invasion; the yearly tribute was tripled, rising to 2,100 Roman pounds (c. 700 kg) in gold; and the ransom for each Roman prisoner rose to 12 solidi.

Their demands were met for a time, and the Hun kings withdrew into the interior of their empire. Bleda died following the Huns' withdrawal from Byzantium (probably around 445). Attila then took the throne for himself, becoming the sole ruler of the Huns.

Solitary kingship

In 447, Attila again rode south into the Eastern Roman Empirethrough Moesia. The Roman army, under Gothic magister militum Arnegisclus, met him in the Battle of the Utus and was defeated, though not without inflicting heavy losses. The Huns were left unopposed and rampaged through the Balkans as far as Thermopylae.

Constantinople itself was saved by the Isaurian troops of magister militum per Orientem Zeno and protected by the intervention of prefect Constantinus, who organized the reconstruction of the walls that had been previously damaged by earthquakes and, in some places, to construct a new line of fortification in front of the old. Callinicus, in his Life of Saint Hypatius, wrote:

The barbarian nation of the Huns, which was in Thrace, became so great that more than a hundred cities were captured and Constantinople almost came into danger and most men fled from it. ... And there were so many murders and blood-lettings that the dead could not be numbered. Ay, for they took captive the churches and monasteries and slew the monks and maidens in great numbers.

In the west

BildThe general path of the Hun forces in the invasion of Gaul

In 450, Attila proclaimed his intent to attack the Visigothkingdom of Toulouse by making an alliance with Emperor Valentinian III. He had previously been on good terms with the Western Roman Empire and its influential general Flavius Aëtius. Aëtius had spent a brief exileamong the Huns in 433, and the troops that Attila provided against the Goths and Bagaudaehad helped earn him the largely honorary title of magister militumin the west. The gifts and diplomatic efforts of Geiseric, who opposed and feared the Visigoths, may also have influenced Attila's plans.

However, Valentinian's sister was Honoria, who had sent the Hunnish king a plea for help—and her engagement ring—in order to escape her forced betrothal to a Roman senator in the spring of 450. Honoria may not have intended a proposal of marriage, but Attila chose to interpret her message as such. He accepted, asking for half of the western Empire as dowry.

When Valentinian discovered the plan, only the influence of his mother Galla Placidia convinced him to exile Honoria, rather than killing her. He also wrote to Attila, strenuously denying the legitimacy of the supposed marriage proposal. Attila sent an emissary to Ravenna to proclaim that Honoria was innocent, that the proposal had been legitimate, and that he would come to claim what was rightfully his.

Attila interfered in a succession struggle after the death of a Frankish ruler. Attila supported the elder son, while Aëtius supported the younger. (The location and identity of these kings is not known and subject to conjecture.) Attila gathered his vassals—Gepids, Ostrogoths, Rugians, Scirians, Heruls, Thuringians, Alans, Burgundians, among others–and began his march west. In 451, he arrived in Belgica with an army exaggerated by Jordanes to half a million strong.

On April 7, he captured Metz. Other cities attacked can be determined by the hagiographicvitae written to commemorate their bishops: Nicasius was slaughtered before the altar of his church in Rheims; Servatus is alleged to have saved Tongerenwith his prayers, as Saint Genevieve is said to have saved Paris. Lupus, bishop of Troyes, is also credited with saving his city by meeting Attila in person.

Aëtius moved to oppose Attila, gathering troops from among the Franks, the Burgundians, and the Celts. A mission by Avitus and Attila's continued westward advance convinced the Visigoth king Theodoric I (Theodorid) to ally with the Romans. The combined armies reached Orléans ahead of Attila, thus checking and turning back the Hunnish advance. Aëtius gave chase and caught the Huns at a place usually assumed to be near Catalaunum (modern Châlons-en-Champagne). Attila decided to fight the Romans on plains where he could use his cavalry.

The two armies clashed in the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains, the outcome of which is commonly considered to be a strategic victory for the Visigothic-Roman alliance. Theodoric was killed in the fighting, and Aëtius failed to press his advantage, according to Edward Gibbon and Edward Creasy, because he feared the consequences of an overwhelming Visigothic triumph as much as he did a defeat. From Aëtius' point of view, the best outcome was what occurred: Theodoric died, Attila was in retreat and disarray, and the Romans had the benefit of appearing victorious.

Invasion of Italy and death

BildRaphael's The Meeting between Leo the Great and Attila depicts Leo, escorted by Saint Peter and Saint Paul, meeting with the Hun emperor outside Rome.

Attila returned in 452 to renew his marriage claim with Honoria, invading and ravaging Italy along the way. Communities became established in what would later become Venice as a result of these attacks when the residents fled to small islands in the Venetian Lagoon. His army sacked numerous cities and razed Aquileia so completely that it was afterwards hard to recognize its original site.:159Aëtius lacked the strength to offer battle, but managed to harass and slow Attila's advance with only a shadow force. Attila finally halted at the River Po. By this point, disease and starvation may have taken hold in Attila's camp, thus hindering his war efforts and potentially contributing to the cessation of invasion.[citation needed]

Emperor Valentinian III sent three envoys, the high civilian officers Gennadius Avienus and Trigetius, as well as the Bishop of Rome Leo I, who met Attila at Mincio in the vicinity of Mantua and obtained from him the promise that he would withdraw from Italy and negotiate peace with the Emperor. Prosper of Aquitainegives a short description of the historic meeting, but gives all the credit to Leo for the successful negotiation. Priscus reports that superstitious fear of the fate of Alaric gave him pause—as Alaric died shortly after sacking Rome in 410.

Italy had suffered from a terrible famine in 451 and her crops were faring little better in 452. Attila's devastating invasion of the plains of northern Italy this year did not improve the harvest.:161 To advance on Rome would have required supplies which were not available in Italy, and taking the city would not have improved Attila's supply situation. Therefore, it was more profitable for Attila to conclude peace and retreat to his homeland.:160–161

Furthermore, an East Roman force had crossed the Danube under the command of another officer also named Aetius—who had participated in the Council of Chalcedon the previous year—and proceeded to defeat the Huns who had been left behind by Attila to safeguard their home territories. Attila, hence, faced heavy human and natural pressures to retire "from Italy without ever setting foot south of the Po".:163 As Hydatiuswrites in his Chronica Minora:

The Huns, who had been plundering Italy and who had also stormed a number of cities, were victims of divine punishment, being visited with heaven-sent disasters: famine and some kind of disease. In addition, they were slaughtered by auxiliaries sent by the Emperor Marcianand led by Aetius, and at the same time, they were crushed in their [home] settlements ... Thus crushed, they made peace with the Romans and all returned to their homes.

Death

BildThe Huns, led by Attila, invade Italy (Attila, the Scourge of God, by Ulpiano Checa, 1887)

Marcian was the successor of Theodosius, and he had ceased paying tribute to the Huns in late 450 while Attila was occupied in the west. Multiple invasions by the Huns and others had left the Balkans with little to plunder.[citation needed]

After Attila left Italy and returned to his palace across the Danube, he planned to strike at Constantinople again and reclaim the tribute which Marcian had stopped. However, he died in the early months of 453.

The conventional account from Priscus says that Attila was at a feast celebrating his latest marriage, this time to the beautiful young Ildico (the name suggests Gothic or Ostrogothorigins).:164 In the midst of the revels, however, he suffered severe bleeding and died. He may have had a nosebleed and choked to death in a stupor. Or he may have succumbed to internal bleeding, possibly due to ruptured esophageal varices. Esophageal varices are dilated veins that form in the lower part of the esophagus, often caused by years of excessive alcohol consumption; they are fragile and can easily rupture, leading to death by hemorrhage.

Another account of his death was first recorded 80 years after the events by Roman chronicler Marcellinus Comes. It reports that "Attila, King of the Huns and ravager of the provinces of Europe, was pierced by the hand and blade of his wife". One modern analyst suggests that he was assassinated, but most reject these accounts as no more than hearsay, preferring instead the account given by Attila's contemporary Priscus, recounted in the 6th century by Jordanes:

On the following day, when a great part of the morning was spent, the royal attendants suspected some ill and, after a great uproar, broke in the doors. There they found the death of Attila accomplished by an effusion of blood, without any wound, and the girl with downcast face weeping beneath her veil. Then, as is the custom of that race, they plucked out the hair of their heads and made their faces hideous with deep wounds, that the renowned warrior might be mourned, not by effeminate wailings and tears, but by the blood of men. Moreover a wondrous thing took place in connection with Attila's death. For in a dream some god stood at the side of Marcian, Emperor of the East, while he was disquieted about his fierce foe, and showed him the bow of Attila broken in that same night, as if to intimate that the race of Huns owed much to that weapon. This account the historian Priscus says he accepts upon truthful evidence. For so terrible was Attila thought to be to great empires that the gods announced his death to rulers as a special boon.

His body was placed in the midst of a plain and lay in state in a silken tent as a sight for men's admiration. The best horsemen of the entire tribe of the Huns rode around in circles, after the manner of circus games, in the place to which he had been brought and told of his deeds in a funeral dirge in the following manner: "The chief of the Huns, King Attila, born of his sire Mundiuch, lord of bravest tribes, sole possessor of the Scythian and German realms—powers unknown before—captured cities and terrified both empires of the Roman world and, appeased by their prayers, took annual tribute to save the rest from plunder. And when he had accomplished all this by the favor of fortune, he fell, not by wound of the foe, nor by treachery of friends, but in the midst of his nation at peace, happy in his joy and without sense of pain. Who can rate this as death, when none believes it calls for vengeance?"

When they had mourned him with such lamentations, a strava, as they call it, was celebrated over his tomb with great reveling. They gave way in turn to the extremes of feeling and displayed funereal grief alternating with joy. Then in the secrecy of night they buried his body in the earth. They bound his coffins, the first with gold, the second with silver and the third with the strength of iron, showing by such means that these three things suited the mightiest of kings; iron because he subdued the nations, gold and silver because he received the honors of both empires. They also added the arms of foemen won in the fight, trappings of rare worth, sparkling with various gems, and ornaments of all sorts whereby princely state is maintained. And that so great riches might be kept from human curiosity, they slew those appointed to the work—a dreadful pay for their labor; and thus sudden death was the lot of those who buried him as well as of him who was buried.:254–259

Attila's sons Ellac, Dengizich and Ernak, "in their rash eagerness to rule they all alike destroyed his empire".:259 They "were clamoring that the nations should be divided among them equally and that warlike kings with their peoples should be apportioned to them by lot like a family estate".:259 Against the treatment as "slaves of the basest condition" a Germanic alliance led by the Gepid ruler Ardaric (who was noted for great loyalty to Attila:199) revolted and fought with the Huns in Pannonia in the Battle of Nedao 454 AD.:260–262 Attila's eldest son Ellac was killed in that battle.:262 Attila's sons "regarding the Goths as deserters from their rule, came against them as though they were seeking fugitive slaves", attacked Ostrogothic co-ruler Valamir(who also fought alongside Ardaric and Attila at the Catalaunian Plains:199), but were repelled, and some group of Huns moved to Scythia (probably those of Ernak).:268–269 His brother Dengizich attempted a renewed invasion across the Danube in 468 AD, but was defeated at the Battle of Bassianae by the Ostrogoths.:272–273 Dengizich was killed by Roman-Gothic general Anagast the following year, after which the Hunnic dominion ended.:168

Attila's many children and relatives are known by name and some even by deeds, but soon valid genealogical sources all but dried up, and there seems to be no verifiable way to trace Attila's descendants. This has not stopped many genealogists from attempting to reconstruct a valid line of descent for various medieval rulers. One of the most credible claims has been that of the Nominalia of the Bulgarian khans for mythological Avitoholand Irnik from the Dulo clan of the Bulgars.:103:59, 142

Later folklore and iconography

Further information: Attila in popular culture

BildIllustration of the meeting between Attila and Pope Leo from the Chronicon Pictum, c. 1360

Jordanes embellished the report of Priscus, reporting that Attila had possessed the "Holy War Sword of the Scythians", which was given to him by Mars and made him a "prince of the entire world".

By the end of the 12th century the royal court of Hungaryproclaimed their descent from Attila. Lampert of Hersfeld's contemporary chronicles report that shortly before the year 1071, the Sword of Attila had been presented to Otto of Nordheim by the exiled queen of Hungary, Anastasia of Kiev. This sword, a cavalry sabre now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, appears to be the work of Hungarian goldsmiths of the ninth or tenth century.

An anonymous chronicler of the medieval period represented the meeting of Pope Leo and Atilla as attended also by Saint Peter and Saint Paul, "a miraculous tale calculated to meet the taste of the time" This apotheosis was later portrayed artistically by the Renaissance artist Raphael and sculptor Algardi, whom eighteenth-century historian Edward Gibbon praised for establishing "one of the noblest legends of ecclesiastical tradition".

According to a version of this narrative related in the Chronicon Pictum, a mediaeval Hungarian chronicle, the Pope promised Attila that if he left Rome in peace, one of his successors would receive a holy crown (which has been understood as referring to the Holy Crown of Hungary).

Some histories and chronicles describe him as a great and noble king, and he plays major roles in three Norse sagas: Atlakviða,Volsunga saga, and Atlamál. The Polish Chroniclerepresents Attila's name as Aquila.

Frutolf of Michelsberg and Otto of Freising pointed out that some songs as "vulgar fables" made Theoderic the Great, Attila and Ermanaric contemporaries, when any reader of Jordanes knew that this was not the case. This refers to the so-called historical poems about Dietrich von Bern(Theoderic), in which Etzel (Attila) is Dietrich's refuge in exile from his wicked uncle Ermenrich (Ermanaric). Etzel is most prominent in the poems Dietrichs Flucht and the Rabenschlacht. Etzel also appears as Kriemhild's second noble husband in the Nibelungenlied, in which Kriemhild causes the destruction of both the Hunnish kingdom and that of her Burgundian relatives.

In 1812, Ludwig van Beethovenconceived the idea of writing an opera about Attila and approached August von Kotzebue to write the libretto. It was, however, never written.In 1846, Giuseppe Verdi wrote the opera, loosely based on episodes in Attila's invasion of Italy.

In World War I, Allied propaganda referred to Germans as the "Huns", based on a 1900 speech by Emperor Wilhelm II praising Attila the Hun's military prowess, according to Jawaharlal Nehru's Glimpses of World History.Der Spiegel commented on 6 November 1948, that the Sword of Attila was hanging menacingly over Austria.

American writer Cecelia Hollandwrote The Death of Attila (1973), a historical novel in which Attila appears as a powerful background figure whose life and death deeply affect the protagonists, a young Hunnic warrior and a Germanic one.

The name has many variants in several languages: Atli and Atle in Old Norse; Etzel in Middle High German (Nibelungenlied); Ætla in Old English; Attila, Atilla, and Etele in Hungarian (Attila is the most popular); Attila, Atilla, Atilay, or Atila in Turkish; and Adil and Edil in Kazakh or Adil ("same/similar") or Edil ("to use") in Mongolian.

In modern Hungary and in Turkey, "Attila" and its Turkish variation "Atilla" are commonly used as a male first name. In Hungary, several public places are named after Attila; for instance, in Budapest there are 10 Attila Streets, one of which is an important street behind the Buda Castle. When the Turkish Armed Forces invaded Cyprus in 1974, the operations were named after Attila ("The Attila Plan").

The 1954 Universal Internationalfilm Sign of the Pagan starred Jack Palance as Attila.

Depictions of Attila

Bild

Attila the Hun

Bild

Attila the Hun in an illustration in the Poetic Edda

Bild

A nineteenth-century depiction of Attila. Certosa di Pavia - Medallion at the base of the facade. The Latin inscription tells that this is Attila, the scourge of God.

Bild

Image of Attila

Bild

The Meeting of Leo I

and Attila

by Alessandro Algardi

(1646–1653 )

#FulinASTKHCLulinPiyi.🐺🌲🐉

0 notes

Text

Got some @greer-art / @pangur-and-grim enamel pins in today! Added most onto my pin wall, and one over to the Gay Witchcraft And Candle Area (WIP). Isopod making me hanker to get an isopod vivarium again oh no

#enamel pins#pin board#pin collection#isopod#chicken#cow#the kitten#the two headed calf#wild geese#poetry#mary oliver#laura gilpin#scythian chieftain#tattoo#cw: insects#cw: medical#not sure what to tag the cyclops cat one#just chu things

152 notes

·

View notes

Photo

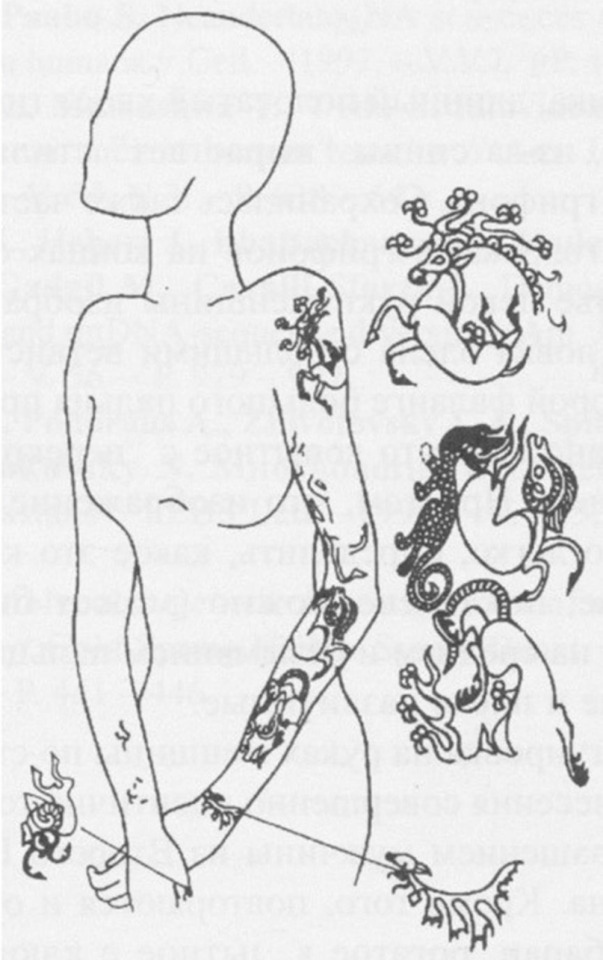

currently working on the backing cards for the ancient tattoo enamel pins!

(also there’s only 4 of the Scythian Chieftain stags left in the shop, so if you want one definitely grab it in the next couple hours)

#for the background texture I didn't want to use......mummified flesh 😳#crinkly old paper seemed like a good substitute#EDIT: down to 3 of the Scythian Chieftain stags left!

514 notes

·

View notes

Text

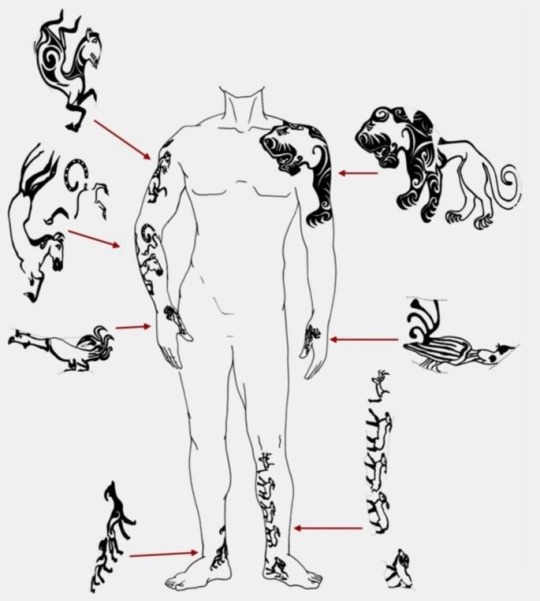

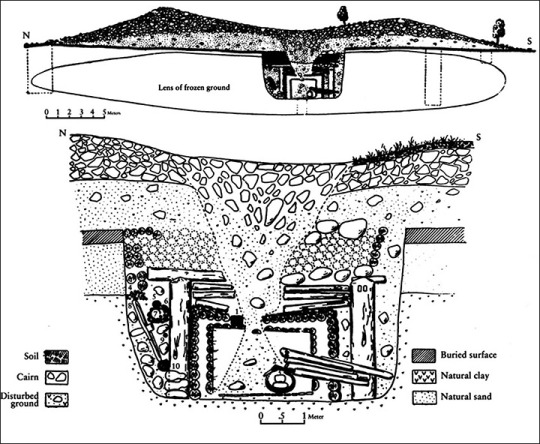

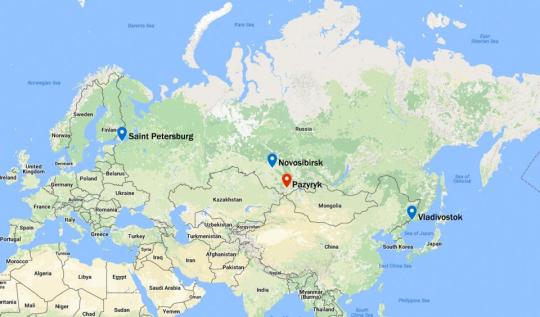

Scythian mummy tomb (Fifth Pazyryk Kurgan), Pazyryk culture 3rd C. BCE. More pictures on my blog, link at bottom.

"The pair were buried alongside nine horses, a huge cache of cannabis and a stash of priceless treasures - including the world's oldest carpet and an ornate carriage.

The man had curly hair and was aged between 55 and 60 when he died, whilst the woman was about ten years younger.

It is believed he was a chieftain or king of the Pazyryk civilisation, which lived in Kazakhstan, Siberia and Mongolia from the 6th to 3rd centuries BC."

...

"The attractive log cabin was a prefabricated construction by the prehistoric Pazyryk culture to house an elite tomb - in which was buried a mummified curly-haired potentate and his younger wife or concubine.

The mound in the Altai Mountains was originally 42 metres in diameter, and this tattooed couple went to the next life alongside nine geldings, saddled and harnessed.

The house itself, recently reconstructed, was not built as a dwelling but nevertheless is seen by archeologists as showing the style of domestic architecture more than two millennia ago.

This structure was the outer of two wooden houses in the large burial mound in the valley of the River Bolshoy Ulagan at an altitude of around 1,600 metres above sea level.

The core of the mound including the ice-preserved bodies of the elite couple had been excavated by Soviet archeologists in 1949, and many of the finds are on on display in the world famous State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg.

As we have previously written, the pair - who owned perhaps the world’s oldest carpets - are currently undergoing an ultra modern medical scan to establish the cause of death, and reconstruct the appearance of the ancient pair, and to study the techniques of mummification in more detail.

Yet in 1949 this fascinating house was left in the permafrost ground - and only retrieved now from the so-called Fifth Pazyryk Barrow, to the excitement of archeologists.

Head of the excavation Dr Nikita Konstantinov from Gorno-Altaisk State University, was full of admiration about the skills of the ancient craftsmen.

‘We took out the log house and reassembled it right next to the mound,’ he said.

‘We made kind of express reconstruction, which made it possible to study the log house in detail.

‘Notches were made on each of its logs - building marks…’.

This was like IKEA instructions today for building their products, telling modern day excavation volunteers how to correctly construct the prehistoric building kit.

The result is seen in the pictures shown here.

‘This log house was first built somewhere away from the mound, then it was dismantled, brought and reassembled in the pit,’ said Dr Konstantinov.

‘Today we build in similar way, using Roman numerals, as a rule.

‘In those times they simply made different numbers of notches.’

The archeological team followed the code left by the ancient craftsmen and reassembled the house without problems.

‘The Pazyryks knitted the corners of the building in a masterly way and chopped the attachment points of these logs.

‘They fitted very cleanly….

‘When we built the log house and began to measure the height, it turned out that the height difference in the angles is only one centimetre.’

In modern constructions, a difference of 7 cm is allowed which showed how skilful were the ancient craftsmen.

He said: ‘This is a funerary structure, but we can say with a high degree of probability that the log cabin was created in the image and likeness of the houses in which the Pazyryks lived."

-taken from siberiantimes and thesun

#scythian#pazyryk#saka#pagan#archaeology#anthropology#architecture#history#ancient history#museums#mummies#artifacts#antiquities#ancient art#tattoos#4th century bce

427 notes

·

View notes

Link

The Great Kurultáj, an event held annually outside the town of Bugac, Hungary, is billed as both the “Tribal Assembly of the Hun-Turkic Nations” and “Europe’s Largest Equestrian Event.” When I arrived last August, I was fittingly greeted by a variety of riders on horseback: some dressed as Huns, others as Parthian cavalrymen, Scythian archers, Magyar warriors, csikós cowboys, and betyár bandits. In total there were representatives from twenty-seven “tribes,” all members of the “Hun-Turkic” fraternity. The festival’s entrance was marked by a sixty-foot-tall portrait of Attila himself, wielding an immense broadsword and standing in front of what was either a bonfire or a sky illuminated by the baleful glow of war. He sported a goatee in the style of Steven Seagal and, shorn of his war braids and helmet, might have been someone you could find in a Budapest cellar bar. A slight smirk suggested that great mirth and great violence together mingled in his soul.

The Arrival of the Hungarians (Feszty Panorama), by Árpád Feszty, which depicts the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin in the late ninth century. Created by Feszty and approximately twenty assistants between 1892 and 1894, the cyclorama measures approximately 15 by 140 meters. Courtesy TiborK and the Ópusztaszer National Heritage Park, Hungary

Inside, I watched a procession of riders—Azeris, Avars, Bashkirs, Chuvashes, Karakalpaks—take turns galloping around the amphitheater, a vast oval of trampled earth. Then, after each brother nation had been announced, the Battle of Pozsony began. Four hundred and fifty-four years after Attila’s death, in 907, a Frankish army came charging out of Bavaria into the heart of the nascent Hungarian kingdom. The Hungarians beat them with an old nomad trick: they fooled the Franks into thinking they were on the retreat, wheeled around at the last second to spring a trap on their unsuspecting foes, and showered them with arrows when they were too close to escape. The original bloodbath took place over the course of three days, but that day at the festival the Hungarian troops needed to wrap things up in thirty-five minutes.

From the start, the Franks, on foot and few in number, looked uneasy. Their swords and shields were distressingly flimsy, like toys. Prince Luitpold, their ostensible commander, didn’t seem to be around. When the Hungarians entered the field of battle on fleet-looking steeds, wearing far shinier helmets and brandishing what appeared to be actual swords, they made short work of the badly overmatched invaders. The crowd cheered—and with good reason. According to the Kurultáj’s website, the Battle of Pozsony is the subject of a generations-long cover-up, the battle “they” don’t want you to know about. Why, the site asks, is this most important military engagement not taught in schools? Why do students dwell instead on the routs at Merseburg and Lechfeld, which finally put an end to the Magyar menace hanging over Europe? (“Magyar” is the historical name by which Hungarians still refer to themselves.) Surely, it is all part of a socialist plot to make Hungarians feel like a guilty people, plagued by defeat, the post goes on, asked again and again by everyone from the Austrians to the Soviets to the European Union to “dare to be small.”

This is the key to the political message behind the Kurultáj: that the truth of the Hungarian past has been suppressed, obscuring the Hungarian people’s origins as a nomadic race of pagan warriors, born for conquest but forced into submission by treacherous neighbors, liberal ideologues, even Christianity itself. Given its nationalist orientation, it’s no surprise that the Kurultáj was established in close association with Jobbik, Hungary’s onetime ultra-nationalist political party. (It has since slightly tempered its message.) Today, the festival’s patron is Fidesz, the party of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, which now occupies the rightmost spot on the political spectrum. Fidesz gives the event around a million euros a year, which is the reason admission is free and why, in the absolute middle of nowhere, it takes an hour of waiting in traffic to get in.

Fidesz’s sponsorship is also why László Kövér, the speaker of Parliament, was addressing festival attendees in the conference tent shortly after I arrived. He began by welcoming the “heirs and worshippers of Attila and Árpád’s people,” the latter name invoking the chieftain who formed Hungary’s first royal dynasty, and in a few short minutes laid out his own version of the conspiracy preventing Hungarians from knowing their true past. Once upon a time, he explained, the Huns broke their enemies with their ferocious mounted archers. Today, the enemies of the homeland employ a more insidious strategy: they attack the mind. They falsify history and sow confusion about people’s “gender, family, religious, and national identities” until they don’t know who they are or where they are from. But Kövér knows. Hungarians are “the westernmost Eastern people.” Their real roots are on the battlefield, on the steppes, with the nomads. With Attila the Hun

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Greeks and Thracians

The Iliad and the Odyssey reflect the first clashes of Greeks and Thracians along the Aegean coast, when the Greeks were trying to colonize the Thracian shores, perhaps as early as the 8th or 7th century B. C. We are acquainted with Thracian pottery of that period, which is distinguished by its comparatively beautiful forms and the black brilliance of its surfaces. But it is the wonderful gold treasure found at Vulchi Trun, Pleven district, and now in the Sofia Museum, consisting of 13 vessels weighing 12.425 kg. and made of pure massive gold, which is particularly eloquent of the great changes that took place in the social relations of the Thracians at that time. The technique used in making these vessels is amazing, and so are the perfect skill with which the incrustations are made, and the strange forms of certain of the vessels. This treasure was undoubtedly the property of an eminent Thracian chieftain of the 8th century B. C.

The well known four bronze axes, found at different places in North and South Bulgaria, ornamented with rather schematically presented heads or whole bodies of animals, horned cattle or sheep, are also considered as belonging to this same early period. In style, they are closely linked with the culture of the Caucasian peoples. A small bronze amulet, representing a stag, and found at the village of Mihailovo (Dolna Gnoynitsa), near Oryahovo, also strongly recalls the well known amulets of Koban. Finally, one more bronze figurine of a stag, found in the region or Sevlievo tours bulgaria, should also be mentioned, as it is distinguished by the strongly conventionalized and geometrically shaped forms of the body. All these finds, as well as certain bronze fibulae, bracelets and so on, show the close cultural links of these lands with the culture of the tribes of the Lower Danu- bian lands and the Caucasus in the early iron age.

From the 6th century on, both the written data on and the archaeological monuments of the Thracians grow more and more plentiful. The Greek historians Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon and others, give us detailed information on the Thracian tribes. The most important of these, the Moesians and the Triballi, were settled north of the Balkan Range, the Getae in North-Eastern Bulgaria, the Odrysae to the South in the valley of the Hebrus (Maritsa), while the Bessi inhabited the Rhodope region, along the upper reaches of this river.

Edoni and Odomanti

The tribes of Edoni and Odomanti, and beyond them the Satrae are frequently mentioned in South-East Macedonia. The lands of the basins of the Central and the Upper Strouma were inhabited by the Sintae and Dentheletae. To the West of them was the big tribe of the Paeonians, of which it cannot yet be said with any degree of certainty whether they belonged to the Thracian ethnical circle or to that of the Illyrians. The south-eastern lands of the peninsula were inhabited by a whole series of tribes, among which the Astae occupied an important place.

To the west, the Thracians bordered on the Illyrian tribes. The question of the reciprocal cultural influences of Thracians and Illyrians, who are considered the bearers of the Hallstatt culture in the Balkans, has not been studied as yet at all thoroughly. No systematic research work has been done in the border regions of these tribes. To the south-west, the Macedonians appeared very early and in the second half of the millenium they gradually laid hands on extensive Thracian regions to the east of the valley of the Vardar River, the ancient Axius, as far as the valley of the Strouma. Their rulers Philip II (359-336 B. C.) and Alexander III (336-323 B. C.) tried to conquer the remaining Thracian lands as well.

Nor was the picture to the north-east any different. Here, since time immemorial, the Thracians had had the Scythians as their neighbours who, after Darius’s unsuccessful campaign against them (513 B. C.) systematically began to cross the Danube into Thracian lands, and in the 4th century B. C. all Dobroudja of today fell into their hands. The campaigns of Darius (492 B. C.) and of Xerxes (in 480 B. C.) against the European Greeks also passed through the lands of the southernmost Thracians. Classical authors have left us detailed descriptions ol the struggles of the Greek colonists against the Thracian tribes of the coast and the interior. The Thracians did not yield their land to the conquerors so easily; it was rich in gold and silver and other similar wealth.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Greeks and Thracians

The Iliad and the Odyssey reflect the first clashes of Greeks and Thracians along the Aegean coast, when the Greeks were trying to colonize the Thracian shores, perhaps as early as the 8th or 7th century B. C. We are acquainted with Thracian pottery of that period, which is distinguished by its comparatively beautiful forms and the black brilliance of its surfaces. But it is the wonderful gold treasure found at Vulchi Trun, Pleven district, and now in the Sofia Museum, consisting of 13 vessels weighing 12.425 kg. and made of pure massive gold, which is particularly eloquent of the great changes that took place in the social relations of the Thracians at that time. The technique used in making these vessels is amazing, and so are the perfect skill with which the incrustations are made, and the strange forms of certain of the vessels. This treasure was undoubtedly the property of an eminent Thracian chieftain of the 8th century B. C.

The well known four bronze axes, found at different places in North and South Bulgaria, ornamented with rather schematically presented heads or whole bodies of animals, horned cattle or sheep, are also considered as belonging to this same early period. In style, they are closely linked with the culture of the Caucasian peoples. A small bronze amulet, representing a stag, and found at the village of Mihailovo (Dolna Gnoynitsa), near Oryahovo, also strongly recalls the well known amulets of Koban. Finally, one more bronze figurine of a stag, found in the region or Sevlievo tours bulgaria, should also be mentioned, as it is distinguished by the strongly conventionalized and geometrically shaped forms of the body. All these finds, as well as certain bronze fibulae, bracelets and so on, show the close cultural links of these lands with the culture of the tribes of the Lower Danu- bian lands and the Caucasus in the early iron age.

From the 6th century on, both the written data on and the archaeological monuments of the Thracians grow more and more plentiful. The Greek historians Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon and others, give us detailed information on the Thracian tribes. The most important of these, the Moesians and the Triballi, were settled north of the Balkan Range, the Getae in North-Eastern Bulgaria, the Odrysae to the South in the valley of the Hebrus (Maritsa), while the Bessi inhabited the Rhodope region, along the upper reaches of this river.

Edoni and Odomanti

The tribes of Edoni and Odomanti, and beyond them the Satrae are frequently mentioned in South-East Macedonia. The lands of the basins of the Central and the Upper Strouma were inhabited by the Sintae and Dentheletae. To the West of them was the big tribe of the Paeonians, of which it cannot yet be said with any degree of certainty whether they belonged to the Thracian ethnical circle or to that of the Illyrians. The south-eastern lands of the peninsula were inhabited by a whole series of tribes, among which the Astae occupied an important place.

To the west, the Thracians bordered on the Illyrian tribes. The question of the reciprocal cultural influences of Thracians and Illyrians, who are considered the bearers of the Hallstatt culture in the Balkans, has not been studied as yet at all thoroughly. No systematic research work has been done in the border regions of these tribes. To the south-west, the Macedonians appeared very early and in the second half of the millenium they gradually laid hands on extensive Thracian regions to the east of the valley of the Vardar River, the ancient Axius, as far as the valley of the Strouma. Their rulers Philip II (359-336 B. C.) and Alexander III (336-323 B. C.) tried to conquer the remaining Thracian lands as well.

Nor was the picture to the north-east any different. Here, since time immemorial, the Thracians had had the Scythians as their neighbours who, after Darius’s unsuccessful campaign against them (513 B. C.) systematically began to cross the Danube into Thracian lands, and in the 4th century B. C. all Dobroudja of today fell into their hands. The campaigns of Darius (492 B. C.) and of Xerxes (in 480 B. C.) against the European Greeks also passed through the lands of the southernmost Thracians. Classical authors have left us detailed descriptions ol the struggles of the Greek colonists against the Thracian tribes of the coast and the interior. The Thracians did not yield their land to the conquerors so easily; it was rich in gold and silver and other similar wealth.

0 notes

Photo

Greeks and Thracians

The Iliad and the Odyssey reflect the first clashes of Greeks and Thracians along the Aegean coast, when the Greeks were trying to colonize the Thracian shores, perhaps as early as the 8th or 7th century B. C. We are acquainted with Thracian pottery of that period, which is distinguished by its comparatively beautiful forms and the black brilliance of its surfaces. But it is the wonderful gold treasure found at Vulchi Trun, Pleven district, and now in the Sofia Museum, consisting of 13 vessels weighing 12.425 kg. and made of pure massive gold, which is particularly eloquent of the great changes that took place in the social relations of the Thracians at that time. The technique used in making these vessels is amazing, and so are the perfect skill with which the incrustations are made, and the strange forms of certain of the vessels. This treasure was undoubtedly the property of an eminent Thracian chieftain of the 8th century B. C.

The well known four bronze axes, found at different places in North and South Bulgaria, ornamented with rather schematically presented heads or whole bodies of animals, horned cattle or sheep, are also considered as belonging to this same early period. In style, they are closely linked with the culture of the Caucasian peoples. A small bronze amulet, representing a stag, and found at the village of Mihailovo (Dolna Gnoynitsa), near Oryahovo, also strongly recalls the well known amulets of Koban. Finally, one more bronze figurine of a stag, found in the region or Sevlievo tours bulgaria, should also be mentioned, as it is distinguished by the strongly conventionalized and geometrically shaped forms of the body. All these finds, as well as certain bronze fibulae, bracelets and so on, show the close cultural links of these lands with the culture of the tribes of the Lower Danu- bian lands and the Caucasus in the early iron age.

From the 6th century on, both the written data on and the archaeological monuments of the Thracians grow more and more plentiful. The Greek historians Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon and others, give us detailed information on the Thracian tribes. The most important of these, the Moesians and the Triballi, were settled north of the Balkan Range, the Getae in North-Eastern Bulgaria, the Odrysae to the South in the valley of the Hebrus (Maritsa), while the Bessi inhabited the Rhodope region, along the upper reaches of this river.

Edoni and Odomanti

The tribes of Edoni and Odomanti, and beyond them the Satrae are frequently mentioned in South-East Macedonia. The lands of the basins of the Central and the Upper Strouma were inhabited by the Sintae and Dentheletae. To the West of them was the big tribe of the Paeonians, of which it cannot yet be said with any degree of certainty whether they belonged to the Thracian ethnical circle or to that of the Illyrians. The south-eastern lands of the peninsula were inhabited by a whole series of tribes, among which the Astae occupied an important place.

To the west, the Thracians bordered on the Illyrian tribes. The question of the reciprocal cultural influences of Thracians and Illyrians, who are considered the bearers of the Hallstatt culture in the Balkans, has not been studied as yet at all thoroughly. No systematic research work has been done in the border regions of these tribes. To the south-west, the Macedonians appeared very early and in the second half of the millenium they gradually laid hands on extensive Thracian regions to the east of the valley of the Vardar River, the ancient Axius, as far as the valley of the Strouma. Their rulers Philip II (359-336 B. C.) and Alexander III (336-323 B. C.) tried to conquer the remaining Thracian lands as well.

Nor was the picture to the north-east any different. Here, since time immemorial, the Thracians had had the Scythians as their neighbours who, after Darius’s unsuccessful campaign against them (513 B. C.) systematically began to cross the Danube into Thracian lands, and in the 4th century B. C. all Dobroudja of today fell into their hands. The campaigns of Darius (492 B. C.) and of Xerxes (in 480 B. C.) against the European Greeks also passed through the lands of the southernmost Thracians. Classical authors have left us detailed descriptions ol the struggles of the Greek colonists against the Thracian tribes of the coast and the interior. The Thracians did not yield their land to the conquerors so easily; it was rich in gold and silver and other similar wealth.

0 notes

Photo

Greeks and Thracians

The Iliad and the Odyssey reflect the first clashes of Greeks and Thracians along the Aegean coast, when the Greeks were trying to colonize the Thracian shores, perhaps as early as the 8th or 7th century B. C. We are acquainted with Thracian pottery of that period, which is distinguished by its comparatively beautiful forms and the black brilliance of its surfaces. But it is the wonderful gold treasure found at Vulchi Trun, Pleven district, and now in the Sofia Museum, consisting of 13 vessels weighing 12.425 kg. and made of pure massive gold, which is particularly eloquent of the great changes that took place in the social relations of the Thracians at that time. The technique used in making these vessels is amazing, and so are the perfect skill with which the incrustations are made, and the strange forms of certain of the vessels. This treasure was undoubtedly the property of an eminent Thracian chieftain of the 8th century B. C.

The well known four bronze axes, found at different places in North and South Bulgaria, ornamented with rather schematically presented heads or whole bodies of animals, horned cattle or sheep, are also considered as belonging to this same early period. In style, they are closely linked with the culture of the Caucasian peoples. A small bronze amulet, representing a stag, and found at the village of Mihailovo (Dolna Gnoynitsa), near Oryahovo, also strongly recalls the well known amulets of Koban. Finally, one more bronze figurine of a stag, found in the region or Sevlievo tours bulgaria, should also be mentioned, as it is distinguished by the strongly conventionalized and geometrically shaped forms of the body. All these finds, as well as certain bronze fibulae, bracelets and so on, show the close cultural links of these lands with the culture of the tribes of the Lower Danu- bian lands and the Caucasus in the early iron age.

From the 6th century on, both the written data on and the archaeological monuments of the Thracians grow more and more plentiful. The Greek historians Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon and others, give us detailed information on the Thracian tribes. The most important of these, the Moesians and the Triballi, were settled north of the Balkan Range, the Getae in North-Eastern Bulgaria, the Odrysae to the South in the valley of the Hebrus (Maritsa), while the Bessi inhabited the Rhodope region, along the upper reaches of this river.

Edoni and Odomanti

The tribes of Edoni and Odomanti, and beyond them the Satrae are frequently mentioned in South-East Macedonia. The lands of the basins of the Central and the Upper Strouma were inhabited by the Sintae and Dentheletae. To the West of them was the big tribe of the Paeonians, of which it cannot yet be said with any degree of certainty whether they belonged to the Thracian ethnical circle or to that of the Illyrians. The south-eastern lands of the peninsula were inhabited by a whole series of tribes, among which the Astae occupied an important place.

To the west, the Thracians bordered on the Illyrian tribes. The question of the reciprocal cultural influences of Thracians and Illyrians, who are considered the bearers of the Hallstatt culture in the Balkans, has not been studied as yet at all thoroughly. No systematic research work has been done in the border regions of these tribes. To the south-west, the Macedonians appeared very early and in the second half of the millenium they gradually laid hands on extensive Thracian regions to the east of the valley of the Vardar River, the ancient Axius, as far as the valley of the Strouma. Their rulers Philip II (359-336 B. C.) and Alexander III (336-323 B. C.) tried to conquer the remaining Thracian lands as well.

Nor was the picture to the north-east any different. Here, since time immemorial, the Thracians had had the Scythians as their neighbours who, after Darius’s unsuccessful campaign against them (513 B. C.) systematically began to cross the Danube into Thracian lands, and in the 4th century B. C. all Dobroudja of today fell into their hands. The campaigns of Darius (492 B. C.) and of Xerxes (in 480 B. C.) against the European Greeks also passed through the lands of the southernmost Thracians. Classical authors have left us detailed descriptions ol the struggles of the Greek colonists against the Thracian tribes of the coast and the interior. The Thracians did not yield their land to the conquerors so easily; it was rich in gold and silver and other similar wealth.

0 notes

Photo

Greeks and Thracians

The Iliad and the Odyssey reflect the first clashes of Greeks and Thracians along the Aegean coast, when the Greeks were trying to colonize the Thracian shores, perhaps as early as the 8th or 7th century B. C. We are acquainted with Thracian pottery of that period, which is distinguished by its comparatively beautiful forms and the black brilliance of its surfaces. But it is the wonderful gold treasure found at Vulchi Trun, Pleven district, and now in the Sofia Museum, consisting of 13 vessels weighing 12.425 kg. and made of pure massive gold, which is particularly eloquent of the great changes that took place in the social relations of the Thracians at that time. The technique used in making these vessels is amazing, and so are the perfect skill with which the incrustations are made, and the strange forms of certain of the vessels. This treasure was undoubtedly the property of an eminent Thracian chieftain of the 8th century B. C.

The well known four bronze axes, found at different places in North and South Bulgaria, ornamented with rather schematically presented heads or whole bodies of animals, horned cattle or sheep, are also considered as belonging to this same early period. In style, they are closely linked with the culture of the Caucasian peoples. A small bronze amulet, representing a stag, and found at the village of Mihailovo (Dolna Gnoynitsa), near Oryahovo, also strongly recalls the well known amulets of Koban. Finally, one more bronze figurine of a stag, found in the region or Sevlievo tours bulgaria, should also be mentioned, as it is distinguished by the strongly conventionalized and geometrically shaped forms of the body. All these finds, as well as certain bronze fibulae, bracelets and so on, show the close cultural links of these lands with the culture of the tribes of the Lower Danu- bian lands and the Caucasus in the early iron age.

From the 6th century on, both the written data on and the archaeological monuments of the Thracians grow more and more plentiful. The Greek historians Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon and others, give us detailed information on the Thracian tribes. The most important of these, the Moesians and the Triballi, were settled north of the Balkan Range, the Getae in North-Eastern Bulgaria, the Odrysae to the South in the valley of the Hebrus (Maritsa), while the Bessi inhabited the Rhodope region, along the upper reaches of this river.

Edoni and Odomanti

The tribes of Edoni and Odomanti, and beyond them the Satrae are frequently mentioned in South-East Macedonia. The lands of the basins of the Central and the Upper Strouma were inhabited by the Sintae and Dentheletae. To the West of them was the big tribe of the Paeonians, of which it cannot yet be said with any degree of certainty whether they belonged to the Thracian ethnical circle or to that of the Illyrians. The south-eastern lands of the peninsula were inhabited by a whole series of tribes, among which the Astae occupied an important place.

To the west, the Thracians bordered on the Illyrian tribes. The question of the reciprocal cultural influences of Thracians and Illyrians, who are considered the bearers of the Hallstatt culture in the Balkans, has not been studied as yet at all thoroughly. No systematic research work has been done in the border regions of these tribes. To the south-west, the Macedonians appeared very early and in the second half of the millenium they gradually laid hands on extensive Thracian regions to the east of the valley of the Vardar River, the ancient Axius, as far as the valley of the Strouma. Their rulers Philip II (359-336 B. C.) and Alexander III (336-323 B. C.) tried to conquer the remaining Thracian lands as well.

Nor was the picture to the north-east any different. Here, since time immemorial, the Thracians had had the Scythians as their neighbours who, after Darius’s unsuccessful campaign against them (513 B. C.) systematically began to cross the Danube into Thracian lands, and in the 4th century B. C. all Dobroudja of today fell into their hands. The campaigns of Darius (492 B. C.) and of Xerxes (in 480 B. C.) against the European Greeks also passed through the lands of the southernmost Thracians. Classical authors have left us detailed descriptions ol the struggles of the Greek colonists against the Thracian tribes of the coast and the interior. The Thracians did not yield their land to the conquerors so easily; it was rich in gold and silver and other similar wealth.

0 notes

Photo

today's obsession is ancient tattoos, in particular the s-curved floral-antlered deer of the Siberian Ice Maiden and Scythian Chieftain.

it’s such a heavily used trope in modern media (off the top of my head I can think of Pokemon, Annihilation, Bambi, Snow White and the Huntsman, etc) and why wouldn’t it be! antlers look like branches, branches look like antlers, it’s only natural to pair them

but it makes me strangely emotional that our brains have always worked this way, and been drawn to the same imagery over and over again.

I’m also going to resist the urge to make paired enamel pins of these ancient deer, even though I deeply desire little wearable tributes of the past

62K notes

·

View notes

Text

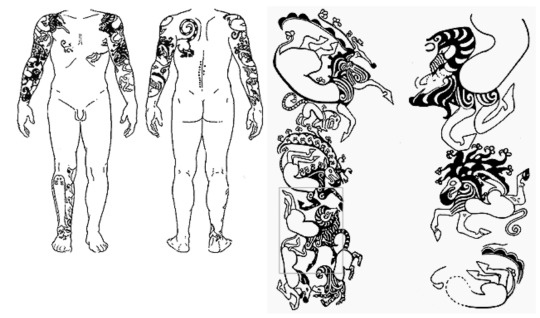

Nabopolassar, king of Babylon, and the king of Scythia at the fall of Nineveh, 612 BCE by Angus McBride

"The Scythians make their first major appearance in the fertile crescent during the 7th and 6th centuries BCE. It is during this time that the nomadic horse archers engage the region’s strongest power up to that date, the Neo Assyrian Empire under Esarhaddon. Presumably, after the Scythians engaged and defeated the Assyrians in a skirmish, Esarhaddon agreed to marry his daughter to the Scythian Chieftain Partatua (whose name meant "with far-reaching strength.") Bartatua was the successor of the previous Scythian king, Išpakaia, and might have been his son. After Išpakaia had attacked the Neo-Assyrian Empire and died in battle against the Assyrian king Esarhaddon around 676 BCE, Bartatua succeeded him. After this event, the Scythians continued to engage in continuous raids throughout the Near East, from Palestine to Egypt. Eventually, the Scythians took part in the biblical event that was the end of the Neo Assyrian Empire, contributing to the sack of Nineveh.

Both in terms of culture and military, the Scythians would have been a shock to the major powers of the time, the Babylonians and Assyrians. Being a series of tribal confederations rather than a concrete nation with cities, any form of retaliation against the Scythians would be nearly impossible (as Cyrus the Great would later find out). The Scythians, being nomads, would attack swiftly with their infamous horse archers, using well-crafted composite bows. The Scythians would then finish the job with heavy cavalry covered in metal scales, which would no doubt be a shock to the Semitic peoples of the Middle East, used to encountering heavy infantry, archers and chariots of Assyria and Egypt.

The presence of women within Scythian society would have been even more of a shock to the states of the Middle East. The Scythians, and particularly their relatives, Sarmatians were famous for their fierce warrior women. In Scythian armies, women were expected to fight alongside their men on horseback. This gave rise to the mythological “Amazons” who indeed had a basis in historical reality. Archaeology confirms this, as many Scythian women are buried with weapons.

The Scythians also took part in the greater economic cultural exchange of the Middle East. Besides trading their prestigious bows, Scythian art appears to be found in Middle Eastern cities such as Urartu and Middle Eastern bowls and jewelry appear in Scythian graves as well. It is even theorized that after seeing Middle Eastern art, the Scythians blended it with their own art style, resulting in the Scythian “animal style” of art, for which the Scythians are famous. The Middle Eastern art adopted by the Scythians would then be spread all over the Middle East and Europe as well. Imagery depicting animals and the hunting of various beasts is thought to have been a product of this cultural exchange, adding to the brilliant craftsmanship of the Scythians."

-taken from arabamerica and wikipedia

#scythian#nabopolassar#art#babylonian#nineveh#assyrian#ancient history#history#pagan#paganism#angus mcbride#7th century bce

294 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Greeks and Thracians

The Iliad and the Odyssey reflect the first clashes of Greeks and Thracians along the Aegean coast, when the Greeks were trying to colonize the Thracian shores, perhaps as early as the 8th or 7th century B. C. We are acquainted with Thracian pottery of that period, which is distinguished by its comparatively beautiful forms and the black brilliance of its surfaces. But it is the wonderful gold treasure found at Vulchi Trun, Pleven district, and now in the Sofia Museum, consisting of 13 vessels weighing 12.425 kg. and made of pure massive gold, which is particularly eloquent of the great changes that took place in the social relations of the Thracians at that time. The technique used in making these vessels is amazing, and so are the perfect skill with which the incrustations are made, and the strange forms of certain of the vessels. This treasure was undoubtedly the property of an eminent Thracian chieftain of the 8th century B. C.

The well known four bronze axes, found at different places in North and South Bulgaria, ornamented with rather schematically presented heads or whole bodies of animals, horned cattle or sheep, are also considered as belonging to this same early period. In style, they are closely linked with the culture of the Caucasian peoples. A small bronze amulet, representing a stag, and found at the village of Mihailovo (Dolna Gnoynitsa), near Oryahovo, also strongly recalls the well known amulets of Koban. Finally, one more bronze figurine of a stag, found in the region or Sevlievo tours bulgaria, should also be mentioned, as it is distinguished by the strongly conventionalized and geometrically shaped forms of the body. All these finds, as well as certain bronze fibulae, bracelets and so on, show the close cultural links of these lands with the culture of the tribes of the Lower Danu- bian lands and the Caucasus in the early iron age.

From the 6th century on, both the written data on and the archaeological monuments of the Thracians grow more and more plentiful. The Greek historians Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon and others, give us detailed information on the Thracian tribes. The most important of these, the Moesians and the Triballi, were settled north of the Balkan Range, the Getae in North-Eastern Bulgaria, the Odrysae to the South in the valley of the Hebrus (Maritsa), while the Bessi inhabited the Rhodope region, along the upper reaches of this river.

Edoni and Odomanti

The tribes of Edoni and Odomanti, and beyond them the Satrae are frequently mentioned in South-East Macedonia. The lands of the basins of the Central and the Upper Strouma were inhabited by the Sintae and Dentheletae. To the West of them was the big tribe of the Paeonians, of which it cannot yet be said with any degree of certainty whether they belonged to the Thracian ethnical circle or to that of the Illyrians. The south-eastern lands of the peninsula were inhabited by a whole series of tribes, among which the Astae occupied an important place.