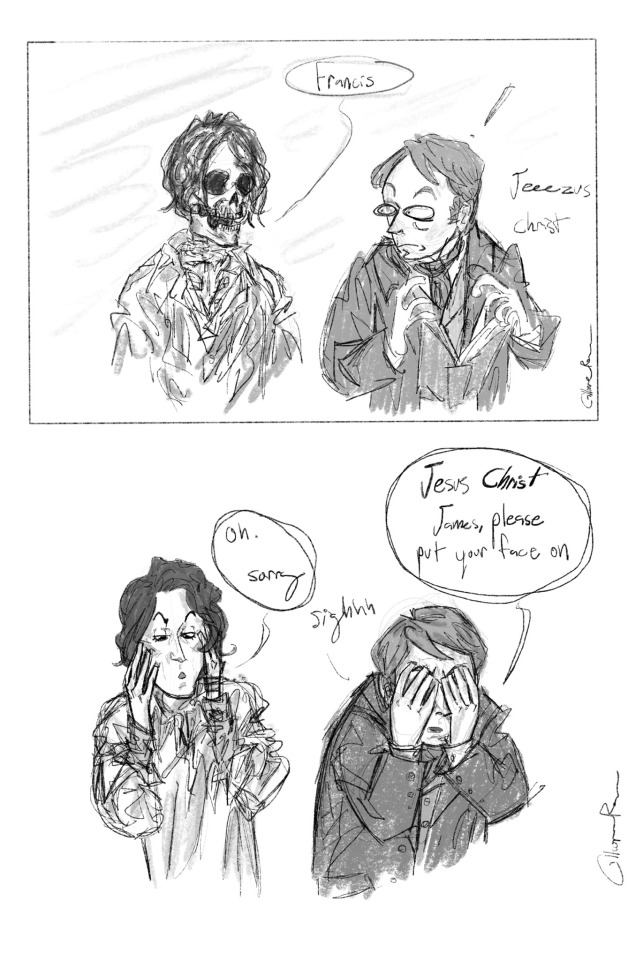

#shifting through different levels of tangibility and decomposition

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

previous , also , next

#ghost fitzjames au#on a somewhat lighter note than my previous installment#james fitzjames#francis crozier#fitzier#amc the terror#the terror fanart#the terror amc#the terror#my drawings#the terror ghosts#haunted terror au#my idea is that he sort of fades in and out#shifting through different levels of tangibility and decomposition#he has a little control of it#but not much#and it often doesn’t occur to him#more on that later though#anyway#happy halloween#🎃#i finished this just in time

354 notes

·

View notes

Text

Originally born in Eine, the now Brussels-based Benjamin Abel Meirhaeghe graduated in Performance Arts at Maastricht’s Theatre Academy. Besides working as a theatre maker, performer and director, Meirhaeghe avidly responds to nicknames such as self-proclaimed narcissist, wannabe countertenor and (medieval) fool. He relativizes and banalizes the socials groups and world he abides in on a very adolescent and self-conscious level, while ironically praising what is not to be praised. As he looks his own devils and those of others straight in the eyes, he channels critique on the thin line between witty humour and seriousness, masterly wielding his enchanting voice as his powerful weapon.

His musical performances are in collaboration with musician/producer Alien Observer. Meirhaeghe is fond of tackling themes such as indifferent free speech and virtual worlds, which divulge his keen sometimes mischievous reflections on deep-rooted concepts. Having previously searched for naturally yet uncomfortably intimate atmospheres in My Inner Songs (2016), he has gone all out in Mea Big Culpa (2017) by centralizing and omni-presenting his persona in music, image and language. With the exalting My Protest (2018) he deliberately causes us to reflect on contemporary tensions and orchestrates an awakening which unleashes a less rose-coloured reality, ultimately freeing us from the bittersweet, transcendent dreamy atmosphere. The precarious tension field between entertaining and criticizing becomes almost tangible in each performance. As he remains an enfant terrible, he mercilessly charms, alleviates and bombards us. The fool becomes king.

Furthermore, he often supports projects and ideas of other performers, positioning him as a metteur en scène. The pieces consistently project a certain, fleeting moment – a lingering echo from his photographic past. Operatesque elements are never hard to find, and explicitly harmonise in his own shows as well. The Dying (Het Sterven) (2017), a collaboration between Kim Karssen and Meirhaeghe, mirrors the process of someone dying in a one-hour long death scene, an outlined drama reciting the foundations of a pathetic theatre. With a nod towards Friedrich Nietzsche’s eponymous, philosophical novel, Also Sprach Zarathustra (2017) gladly flirts with philosophical issues regarding technology and depression instead of honouring the philosophical core of the book. In a prophetic and existential story, Anna Luka Da Silva and Meirhaeghe introduce a robot and human being on stage. The former as an übermensch, equilibrist and semi-fool, the latter as the narrator of Nietzsche’s novel with the infiltrating intention of “We didn’t even read the whole book”. Le Carnaval de Venise (2018), though stripped from its original score, rejuvenates the 17th century libretto by French composer André Campra in a contemporary setting. Using gongs and other atypical sounds, the play develops a special rhythm with references and an accompanying visual language, all conveyed by a five-headed corps de ballet. Every moment alludes to something else. Yet it’s a static physical work, a commedia dell’arte meets the Japanese noh. And despite the stringent score with defined queues, the play embraces avant-gardist and Dadaist influences.

Meirhaeghe allocates himself on the dramatic crossroads between old and contemporary mechanisms of opera. Both are subject to an almost sophisticated decomposition, arranged by yours truly. Shows such as The War (2016), Black Pole (2018) and, as his graduation project, The Ballet (2018) revolt against the classical, archaic opera systems and experiment with diverse forms of artistic autopsy of that conservative world. Meirhaeghe unravels different mechanisms indebted to opera and ballet, and unfolds them, exposing them one by one before creating a new, composed narrative. Movements in the machinery reveal themselves, the suggestive connotation dissolves. The theatrical rigging system is played as if it were a marionet, our range of vision becomes manipulated. The structures, entangled in a hierarchy, answer to his direction. Intense emotions overwhelm us. Oh, the pain, the tragedy, the laughter! His shows bathe in bipolarity, and all the while the fool looks over everyone. He rises on stage and in our souls. Moreover, he sacks the idea of a constant, almost competitive need to prove oneself worthy of something – and with it, stardom and artistic prodigies are suddenly plunged in an ice-cold bath.

The War, a joint effort by Marieke De Zwaan and Daan Couzijn, presents a still image, an extended snapshot of a wounded person who receives first aid by a relief worker. There’s a complete absence of context and background information of the characters. The structure of Le Carnaval de Venise is applied here as well: a stationary, visual language with innuendoes which attentively mirror fixed queues and seek out repetitions in image, sound and wordplay. Armed with extensive timbres and medicinal mantras for the soul, Meirhaeghe elevates the war’s intrinsic ferocity and its aesthetics. Each attempt to revive the heartbeat of the wounded, only ends in the rhythm of the play – whether the heart rate is restored, remains unanswered. A tragedy in a constant, rhythmic spiral.

Another show, again with De Zwaan, thrives on an alternative impetus. Unlike The War, where drama is key, Black Pole utters a non-mesmerising, rather rebellious meta-narrative about tourism. Twenty volunteers, who honestly don’t fake being bored, are followed during their dull flight. When they finally arrive at their destination, multicultural entertainment awaits them and the public. Chinese lions! Indian dance rituals! Turkish music! As fast it came, the excitement disappears, and everyone is back in the same monotonous situation, now homeward bound. Both the audience and the actors endure similar emotions: from disappointment to thrilling ecstasy to severe disappointment. The revolutionary, revolting characteristics of Meirhaeghe’s personality are not only ever-present in his artistic practice, in this play specifically they crave an unusual, alienating experience.

Crowning his four-year study is The Ballet, a humble yet laudable, real feat. Aligned with Kunstencentrum Vooruit’s iconic theatre hall, the play is a benchmark in his ambition of establishing a new artistic discourse. Besides appropriating the structure from an opera-ballet, The Ballet includes operatesque stage props, a historical interior, the sky-high tailored stage curtains, live piano by Maya Dhondt and captivating movements by Emiel Vanderberghe, a professional ballet dancer. The tragedy, soaked in all that splendour, is now and then comically illumed – thus unmasking Meirhaeghe’s bipolarity – and parallels present-day suffering with 18th century, romantic and heart-rending love stories. The Ballet has intensely impersonated emotions in abundance, and as it shifts between melancholy and deep nostalgic desires, the peculiar romance results in an almost adolescent waterloo. While both men eagerly showcase their virtuosity and self-discipline, the play sooths the audience with moving tales and grandeur. Meirhaeghe cunningly addresses two pressing issues: refreshing archaic stories and repertoires in a modern life setting and, as a young artist, taking over a rather rigid institute.

The need to reread, reinterpret and restructure the opera circuit is germinated while studying performance arts. The course encourages experiment and focuses on interdisciplinary approaches, and ultimately helps Meirhaeghe’s evolution from being an autodidact countertenor and solo performer to a director and creator. His then microscopic eye, primarily focused on activating a space, gets a macroscopic upgrade. Or as Peter Missotten describes it: “If you have a problem, make it worse.” On his terms, Meirhaeghe orchestrates a marriage between the traditional opera-ballet genre, experimental and contemporary theatre. The twofold relationship between intense emotions, abstraction, musicality and virtuosity is not to be sacrificed but to be preserved and maintained. And with this calculated disruption of hard-boiled structures, he invites the fool back on stage as the ultimate metaphor.

Also, Vanderberghe’s appearance in The Ballet is not a coincidence. A lot of his works, if not all, are influenced by male muses, Meirhaeghe’s photographic background and the maturing process of his self-conscious, rebellious persona. As a young boy he often captured drama in static snapshots of sudden moments and preferred that momentary feeling as his subject. He evoked his own absent beauty through literally imagining the present, young male nudity, and gradually created several muses, making him experiment with his models. The disentanglement of that emerging balance of power made him appropriate the beauty of others, nearly embodying their charm. Vanderberghe can be perceived as the glorification and idolization of that process: he’s ubiquitous in every work, except The War, and becomes almost a worshipped and praised figure. As a huge influence on Meirhaeghe’s practice, Vanderberghe plays a pivotal and clearly crucial role in his life. The dichotomy becomes once again apparent due to the echoing struggle between uncertainty and self-confidence – a dilemma which also forges a path to focus more on his own shows. And in the wake of previous, great artists and stars that created everlasting masterpieces before him, he immortalizes that nowadays recurring need to prove oneself with the nickname self-proclaimed narcissist. A hyper-personal work with the fool as the catalyst of his art practice and as the personification of that ceaseless ambiguity.

However, in his future repertoire the muses cut back their decisive cameo. The emphasis shifts to a more cross-disciplinary, collaborative and open approach bundled in a more receptive discourse regarding opera and ballet. Considering the involvement of a supportive, engaged group of people as essential, he transcends opera-ballet through an interdependence with contemporary visual art and design without disrespectfully treating the theatrical canon and old repertoire. Think of it as an opera in transition, transformation and (r)evolution. In addition, he concentrates on boundless engagement, exceeding love, in a search for the world’s manifestation and its salvation. For example, Meirhaeghe revamps Ballet de la Nuit, an originally 13-hours long spectacle in which the notorious French king Louis XIV makes his debut as Apollo, and reduces it to an epitome of one hour. He bridges the gap between the French baroque and the now, between classical opera-ballet and 21st century pop. At the same time, he questions the magnificence of that medium because of its immense production without a lot of resources. Other pieces he plans on updating, are Erwartung (1909) by Arnold Schönberg, the proto-opera L’Europe galante (1697) by André Campra, the revolutionizing La muette de Portici (1828) by Daniel Auber and Combattimenti di Tancredi e Clorinda (1624) by Claudio Monteverdi. Every show values the powerful, reciting potential of opera. Whether it is a tableau vivant rendering songs of love and war or stimulates an independence war or drawing a heart-breaking metaphor of Europe: Meirhaeghe calls for change.

Theatre as a time machine with the fool as our guide.

(c) E. Pot

0 notes