#slingerland drum company

Text

Most top rock n’ roll bands use Slingerland - the foremost in drums.

#vintage advertising#slingerland#drum sets#drum kits#slingerland drum company#paul revere and the raiders#the association#herman’s hermits#the mamas and the papas#the turtles#the yardbirds#musical instruments#rock bands#the 60s#60s music#percussion#drummers

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

GENE KRUPA

(English / Español)

Gene Krupa (January 15, 1909 - October 16, 1973) was a famed and influential American jazz musician and big band drummer, known and recognised for his energetic and brilliant playing style. His parents were Polish immigrants to the USA and he was born in Chicago, Illinois. He began his professional career in the mid-1920s with bands in Wisconsin. He emerged on the Chicago music scene in 1927, when he was selected by the MCA to become a member of the orchestra of Thelma Terry and Her Playboys, then the most notable American jazz band led by a woman.

Krupa made his first recording in 1927, with a band led by banjo player Eddie Condon. Krupa also appeared on six records by Thelma Terry's band in 1928. In 1929 he moved to New York City and worked with the Red Nichols band. In 1934 he joined Benny Goodman's band, where his unique drumming made him a national celebrity.

In 1938, after a public falling out with Goodman at the Earl Theater in Philadelphia, he left Goodman to launch his own band, with which he scored several big hits alongside singer Anita O'Day and trumpeter Roy Eldridge. Krupa made a memorable cameo appearance in the 1941 film Ball of Fire, in which he and his band played different versions of the hit song Drum Boogie.

In 1943, Krupa was arrested for possession of cannabis and briefly imprisoned.

Krupa retired musically in the late 1960s, although he played occasionally in public until his death from leukemia in Yonkers, New York. He was buried in Holy Cross Cemetery in Calumet City, Illinois. He became the face of Slingerland Drums, which later launched a "Radio King" series in Krupa's honour.

Krupa is considered by many to be the most influential drummer of the 20th century, especially for the development of the drum instrument itself. His main influence began in 1935 in the company of Benny Goodman, where he excelled as a true star, but above all for his use of the bass drum pedal. This particular method of playing was published in 1938 and became a standard text for the study of the instrument.

*****

Gene Krupa (15 de enero, 1909 – 16 de octubre, 1973) fue un afamado e influyente músico estadounidense de jazz y un gran baterista de big band, conocido y reconocido por su energético y brillante estilo de tocar. Sus padres eran polacos emigrantes en USA y el nació en Chicago, Illinois. Comenzó su carrera profesional a mediados de la decada de los años 1920s con bandas en Wisconsin. Emergió en la escena musical de Chicago en 1927, cuando fue seleccionado por la MCA para convertirse en miembro de la orquesta de Thelma Terry y Sus Playboys, entonces la más notable banda americana de jazz liderada por una mujer.

Krupa hizo su primera grabación en 1927, con una banda liderada por el banjista Eddie Condon. Krupa también aparece en seis discos de la banda de Thelma Terry en 1928. En 1929 se mudó a New York City y trabajó con la banda de Red Nichols. En 1934 se unió a la banda de Benny Goodman, donde su particular forma de tocar la batería le convirtió en una celebridad nacional.

En 1938, tras una pelea pública con Goodman en el Earl Theater en Filadelfia, dejó a Goodman para lanzar su propia banda, con la que obtuvo diferentes grandes éxitos junto a la cantante Anita O'Day y el trompetista Roy Eldridge. Krupa hizo un memorable cameo apareciendo en la película de 1941 Ball of Fire (Bola de Fuego), donde él y su banda tocaban distintas versiones del éxito musical Drum Boogie.

En 1943, Krupa era arrestado por posesión de cannabis siendo brevemente encarcelado.

Krupa se retiró musicalmente a finales de los años 1960s, aunque tocaba ocasionalmente en público hasta su muerte por leucemia en Yonkers, New York. Fue enterrado en el Holy Cross Cemetery en Calumet City, Illinois. Se convirtió en imagen de las baterías Slingerland, fábrica que posteriormente lanzaría una serie "Radio King" en honor a Krupa.

Muchos consideran a Krupa como el más influyente baterista del siglo 20, especialmente por el desarrollo del propio instrumento de la batería. Su principal influencia comenzó en 1935 en compañía de Benny Goodman, donde sobresalió como una auténtica estrella, pero sobre todo por su uso del pedal del bajo de la batería. Este particular método de tocar se publicó en 1938 y se convirtió en un texto estándar para el estudio del instrumento.

fuente: last.fm

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louie Bellson Interview With Jon Hammond HammondCast

#LISTEN TO THE AUDIO HERE: Louie Bellson Interview With Jon Hammond HammondCast

Jon's archive https://archive.org/details/louie-bellson-interview-with-jon-hammond-hammond-cast

Louie Bellson Interview With Jon Hammond HammondCast

by

Jon Hammond

Usage

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International

Topics

Louie Bellson, Jazz Drummer, Band Leader, Double Bass Drums, Johnny Hodges, Pearl Bailey, Educator, HammondCast, CBS Radio, KYOU, KYCY, Jon Hammond

Language

English

Louie Bellson Interview With Jon Hammond HammondCast on CBS KYOU / KYCY Radio - August 2003, he appeared at Jazz Club Nouveau in San Francisco with tenor saxophonist Don Menza -

Louie Bellson's Wiki:

Birth nameLuigi Paolino Alfredo Francesco Antonio BalassoniBornJuly 6, 1924Rock Falls, IllinoisDiedFebruary 14, 2009 (aged 84)Los Angeles, CaliforniaGenresJazz, big band, swingOccupation(s)Musician, composer, arranger, bandleaderInstrument(s)DrumsYears active1931–2009LabelsRoulette, Concord, Pablo, Musicmasters

Louie Bellson (born Luigi Paolino Alfredo Francesco Antonio Balassoni, July 6, 1924 – February 14, 2009), often seen in sources as Louis Bellson, although he himself preferred the spelling Louie, was an American jazz drummer. He was a composer, arranger, bandleader, and jazz educator, and is credited with pioneering the use of two bass drums.[1]

Bellson performed in most of the major capitals around the world. Bellson and his wife, actress and singer Pearl Bailey[2] (married from 1952 until Bailey's death in 1990), had the second highest number of appearances at the White House (only Bob Hope had more).

Bellson was a vice president at Remo, a drum company.[3] He was inducted into the Modern Drummer Hall of Fame in 1985

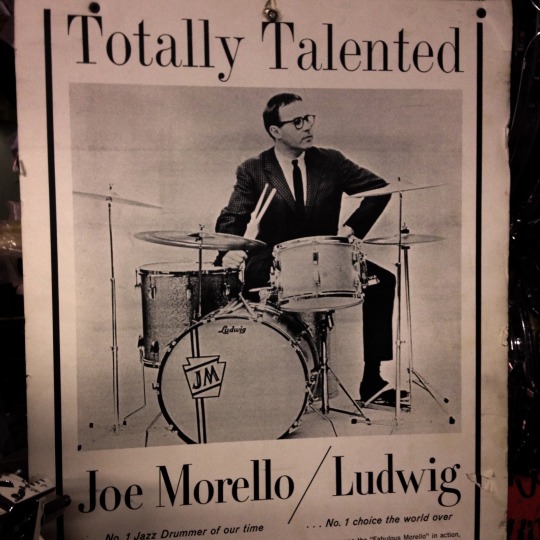

Bellson was born in Rock Falls, Illinois, in 1924, where his father owned a music store. He started playing drums at three years of age. While still a young child, Bellson's father moved the family and music store to Moline, Illinois.[5] At 15, he pioneered using two bass drums at the same time, a technique he invented in his high school art class.[6] At age 17, he triumphed over 40,000 drummers to win the Slingerland National Gene Krupa contest.[7]

After graduating from Moline High School in 1942, he worked with big bands throughout the 1940s, with Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Harry James, and Duke Ellington. In 1952, he married jazz singer Pearl Bailey. During the 1950s, he played with the Dorsey Brothers, Jazz at the Philharmonic, acted as Bailey's music director, and recorded as a leader for Norgran Records and Verve Records.[8]

Over the years, his sidemen included Ray Brown, Pete and Conte Candoli, Chuck Findley, John Heard, Roger Ingram, Don Menza, Blue Mitchell, Larry Novak, Nat Pierce, Frank Rosolino, Bobby Shew, Clark Terry, and Snooky Young.

In an interview in 2005 with Jazz Connection magazine, he cited as influences Jo Jones, Sid Catlett, and Chick Webb. "I have to give just dues to two guys who really got me off on the drums – Big Sid Catlett and Jo Jones. They were my influences. All three of us realized what Jo Jones did and it influenced a lot of us. We all three looked to Jo as the 'Papa' who really did it. Gene helped bring the drums to the foreground as a solo instrument. Buddy was a great natural player. But we also have to look back at Chick Webb's contributions, too."[9]

During the 1960s, he returned to Ellington's orchestra for Emancipation Proclamation Centennial stage production, My People in and for A Concert of Sacred Music, which is sometimes called The First Sacred Concert. Ellington called these concerts "the most important thing I have ever done."[10]

Bellson's album The Sacred Music of Louie Bellson and the Jazz Ballet appeared in 2006. In May 2009, Francine Bellson told The Jazz Joy and Roy syndicated radio show, "I like to call (Sacred) 'how the Master used two maestros,'" adding, "When (Ellington) did his sacred concert back in 1965 with Louie on drums, he told Louie that the sacred concerts were based on 'in-the-beginning,' the first three words of the bible." She recalled how Ellington explained to Louie that "in the beginning there was lightning and thunder and that's you!" Ellington exclaimed, pointing out that Louie's drums were the thunder. Both Ellington and Louie, says Mrs. Bellson, were deeply religious. "Ellington told Louie, 'You ought to do a sacred concert of your own' and so it was," said Bellson, adding, "'The Sacred Music of Louie Bellson' combines symphony, big band and choir, while 'The Jazz Ballet' is based on the vows of Holy Matrimony..."

On December 5, 1971, he took part in a memorial concert at London's Queen Elizabeth Hall for drummer Frank King. This tribute show also featured Buddy Rich and British drummer Kenny Clare. The orchestra was led by Irish trombonist Bobby Lamb and American trombonist Raymond Premru. A few years later, Rich (often called the world's greatest drummer) paid Bellson a compliment by asking him to lead his band on tour while he (Rich) was temporarily disabled by a back injury. Bellson accepted.

As a prolific creator of music, both written and improvised, his compositions and arrangements (in the hundreds) embrace jazz, jazz/rock/fusion, romantic orchestral suites, symphonic works and a ballet. Bellson was also a poet and a lyricist. His only Broadway venture, Portofino (1958), was a resounding flop that closed after three performances.[13]

As an author, he published more than a dozen books on drums and percussion. He was at work with his biographer on a book chronicling his career and bearing the same name as one of his compositions, "Skin Deep". In addition, "The London Suite" (recorded on his album Louie in London) was performed at the Hollywood Pilgrimage Bowl before a record-breaking audience. The three-part work includes a choral section in which a 12-voice choir sings lyrics penned by Bellson. Part One is the band's rousing "Carnaby Street", a collaboration with Jack Hayes.[14]

In 1987, at the Percussive Arts Society convention in Washington, D.C., Bellson and Harold Farberman performed a major orchestral work titled "Concerto for Jazz Drummer and Full Orchestra", the first piece ever written specifically for jazz drummer and full symphony orchestra. This work was recorded by the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra in England, and was released by the Swedish label BIS.

Bellson was known throughout his career to conduct drum and band clinics at high schools, colleges and music stores.[16]

Bellson maintained a tight schedule of clinics and performances of both big bands and small bands in colleges, clubs and concert halls. In between, he continued to record and compose, resulting in more than 100 albums and more than 300 compositions. Bellson's Telarc debut recording, Louie Bellson And His Big Band: Live From New York, was released in June 1994. He also created new drum technology for Remo, of which he was vice-president.[17]

Bellson received an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters in 1985 at Northern Illinois University. As of 2005, among other performing activities, Bellson had visited his home town of Rock Falls, Illinois, every July for Louie Bellson Heritage Days, a weekend in his honor close to his July 6 birthday, with receptions, music clinics and other performances by Bellson.[1] At the 2004 event celebrating his 80th birthday, Bellson said, "I'm not that old; I'm 40 in this leg, and 40 in the other leg."[18] He celebrated his birthday every year at the River Music Experience in Davenport, Iowa.

Bellson was voted into the Halls of Fame for Modern Drummer magazine, in 1985, and the Percussive Arts Society, in 1978. Yale University named him a Duke Ellington Fellow in 1977. He received an honorary Doctorate from Northern Illinois University in 1985. He performed his original concert – Tomus I, II, III – with the Washington Civic Symphony in historic Constitution Hall in 1993. A combination of full symphony orchestra, big-band ensemble and 80-voice choir, "Tomus" was a collaboration of music by Bellson and lyrics by his late wife, Pearl Bailey. Bellson was a nine-time Grammy Award nominee.[19]

In January 1994, Bellson received the NEA Jazz Masters Award from the National Endowment for the Arts.[20] As one of three recipients, he was lauded by NEA chair Jane Alexander, who said, "These colossal talents have helped write the history of jazz in America."

On November 19, 1952, Bellson married American actress and singer, Pearl Bailey, in London. Bellson and Bailey adopted a son, Tony, in the mid-1950s, and a daughter, Dee Dee (born April 20, 1960).[22] Tony Bellson died in 2004, and Dee Dee Bellson died on July 4, 2009, at age 49, within five months of her father. After Bailey's death in 1990, Bellson married Francine Wright in September 1992.[23]

Wright, who had trained as a physicist and engineer at MIT,[24] became his manager. The union lasted until his death in 2009.[25]

On February 14, 2009, Bellson died at age 84 from complications of a broken hip suffered in December 2008 and Parkinson's disease. He is buried next to his father in Riverside Cemetery, Moline, Illinois.

Discography[edit]

As leader[edit]

1952 Just Jazz All Stars (Capitol)

1954 Louis Bellson and His Drums (Norgran)

1955 Skin Deep (Norgran) compiles Belson's 10 inch LPs The Amazing Artistry of Louis Bellson and The Exciting Mr. Bellson

1954 The Exciting Mr. Bellson and His Big Band (Norgran)

1954 Louis Bellson with Wardell Gray (Norgran)

1954 Louis Bellson Quintet (Norgran) also released as Concerto for Drums by Louis Bellson

1954 Journey into Love (Norgan) also released as Two in Love

1955 The Driving Louis Bellson (Norgran)

1956 The Hawk Talks (Norgran)

1957 Drumorama! (Verve)

1959 Let's Call It Swing (Verve)

1959 Music, Romance and Especially Love (Verve)

1957 Louis Bellson at The Flamingo (Verve)

1959 Live in Stereo at the Flamingo Hotel, Vol. 1: June 28, 1959

1961 Drummer's Holiday (Verve)

1960 The Brilliant Bellson Sound (Verve)

1960 Louis Bellson Swings Jule Styne (Verve)

1961 Around the World in Percussion (Roulette)

1962 Big Band Jazz from the Summit (Roulette)

1962 Happy Sounds (Roulette) with Pearl Bailey

1962 The Mighty Two (Roulette) with Gene Krupa

1964 Explorations (Roulette) with Lalo Schifrin

1965 Are You Ready for This? (Roost) with Buddy Rich

1965 Thunderbird (Impulse!)

1967 Repercussion (Studio2Stereo)

1968 Breakthrough! (Project 3)

1970 Louie in London (DRG)

1972 Conversations (Vocalion)

1974 150 MPH (Concord)

1975 The Louis Bellson Explosion (Pablo)

1975 The Drum Session (Philips Records with Shelly Manne, Willie Bobo & Paul Humphrey)

1976 Louie Bellson's 7 (Concord Jazz)

1977 Ecue Ritmos Cubanos (Pablo) with Walfredo de los Reyes

1978 Raincheck (Concord)

1978 Note Smoking

1978 Louis Bellson Jam with Blue Mitchell (Pablo)

1978 Matterhorn: Louie Bellson Drum Explosion

1978 Sunshine Rock (Pablo)

1978 Prime Time (Concord Jazz)

1979 Dynamite (Concord Jazz)

1979 Side Track (Concord Jazz)

1979 Louis Bellson, With Bells On! (Vogue Jazz (UK))[27]

1980 London Scene (Concord Jazz)

1980 Live at Ronnie Scott's (DRG)

1982 Hi Percussion (Accord)

1982 Cool, Cool Blue (Pablo)

1982 The London Gig (Pablo)

1983 Loose Walk

1984 Don't Stop Now! (Capri)

1986 Farberman: Concerto for Jazz Drummer; Shchedrin: Carmen Suite(BIS)

1987 Intensive Care

1988 Hot (Nimbus)

1989 Jazz Giants (Musicmasters)

1989 East Side Suite (Musicmasters)

1990 Airmail Special: A Salute to the Big Band Masters (Musicmasters)

1992 Live at the Jazz Showcase (Concord Jazz)

1992 Peaceful Thunder (Musicmasters)

1994 Live from New York (Telarc)

1994 Black Brown & Beige (Musicmasters)

1994 Cool Cool Blue (Original Jazz Classics)

1994 Salute (Chiaroscuro)

1995 I'm Shooting High (Four Star)

1995 Explosion Band (Exhibit)

1995 Salute (Chiaroscuro)

1995 Live at Concord Summer Festival (Concord Jazz)

1996 Their Time Was the Greatest (Concord Jazz)

1997 Air Bellson (Concord Jazz)

1998 The Art of Chart (Concord Jazz)[28]

As sideman[edit]

With Count Basie

Back with Basie (Roulette, 1962)

Basie in Sweden (Roulette, 1962)

Pop Goes the Basie (Reprise, 1965)

Basie's in the Bag (Brunswick, 1967)

The Happiest Millionaire (Coliseum, 1967)

Count Basie Jam Session at the Montreux Jazz Festival 1975 (Pablo, 1975)

With Benny Carter

Benny Carter Plays Pretty (Norgran, 1954)

New Jazz Sounds (Norgran, 1954)

In the Mood for Swing (MusicMasters, 1988)

With Buddy Collette

Porgy & Bess (Interlude 1957 [1959])

With Duke Ellington

Ellington Uptown (Columbia, 1952)

My People (Contact, 1963)

A Concert of Sacred Music (RCA Victor, 1965)

Ella at Duke's Place (Verve, 1965)

With Dizzy Gillespie

Roy and Diz (Clef, 1954)

With Stephane Grappelli

Classic Sessions: Stephane Grappelli, with Phil Woods and Louie Bellson (1987)

With Johnny Hodges

The Blues (Norgran, 1952–54, [1955])

Used to Be Duke (Norgran, 1954)

Louie Bellson, Jazz Drummer, Band Leader, Double Bass Drums, Johnny Hodges, Pearl Bailey, Educator, HammondCast, CBS Radio, KYOU, KYCY, Jon Hammond

Louie Bellson, Jazz Drummer, Band Leader, Double Bass Drums, Johnny Hodges, Pearl Bailey, Educator, HammondCast, CBS Radio, KYOU, KYCY, Jon Hammond

#Louie Bellson#Jazz Drummer#Band Leader#Double Bass Drums#Johnny Hodges#Pearl Bailey#Educator#HammondCast#CBS Radio#kyouka izumi#KYCY#Jon Hammond

1 note

·

View note

Text

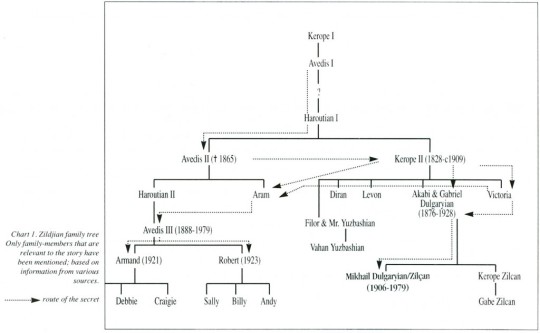

Rethinking the Zildjian Stamp on the 105th Anniversary of the Armenian Genocide

I’ll never forget the day my first “real” set of cymbals were delivered to my house. I was 17 years old and up until that point, I was playing on a beginner set of Sabian B8 cymbals (Sabians entry-level cymbals) and a Tama Swingstar drum kit (Tama’s entry-level kit). I ended up selling those drums and cymbals to a young student as I had acquired a black wrapped late 70′s Niles, IL badge, Slingerland maple drum kit from a family friend, which I still have and play now. To go along with this superb drum kit, my drum instructor, the legendary, Sal LaRocca (Teddy Wilson Quartet, Junior Mance Trio) suggested I look into purchasing a set of used Zildjians.

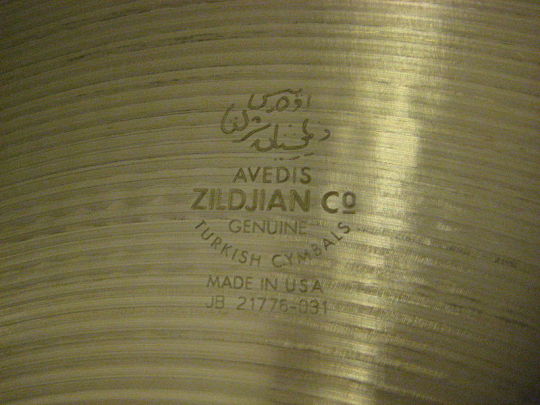

I ended up ordering, I believe it was from Steve Weiss Music in Pennsylvania, a pair of 1950′s Avedis Zildjian Hi-hats (which I still own... fantastic hats), a 16″ A Zildjian Medium-Thin Crash (recently sold), a 1970′s 18″ A Medium Crash (it’s somewhere in a bag around here), and a 20″ A Zildjian Medium Ride (loved that ride, thanks mom and dad). This was sheer excitement for me because all my favorite jazz drummers played Zildjian, and after all the Zildjians, like me were Armenian. Playing on those cymbals (I’ve since traded in the medium ride for a K Ride, but, I’ve recently acquired a 1960′s 20″ Avedis Medium Ride) felt like I was playing on pieces of history. However, the one thing that has bothered me is Zildjian referring to their cymbals as “Turkish”.

Cymbal and bell making goes all the way back to the 2nd millennia B.C. to the Karmir Blur area in Yerevan, Armenia. Bronze and metal work is intrinsically connected to Armenian history. The Armenian plateau, rich in ores, was one of the first places to practice metallurgy and was ahead of neighboring regions in the use of copper and iron. Throughout history Armenians have been master metalworkers and jewelers. Arts of Armenia-Music and the Art of the Book - Fresno State University

Some of my Zildjian cymbals

Zildjian Family History

The history of the Zildjian family and Avedis Zildjian Co. (the oldest family-owned company in North America and the oldest cymbal company in the world) dates back to 1618, when the first Zildjian cymbals were created. Avedis Zildjian was an alchemist exploring for ways to turn metal into gold. During the process of experimentation, he created an alloy (the exact formula is a closely held family secret) combining tin, copper and silver. It was soon discovered that when flattened into a sheet it could make musical sounds while still being durable enough not to shatter.

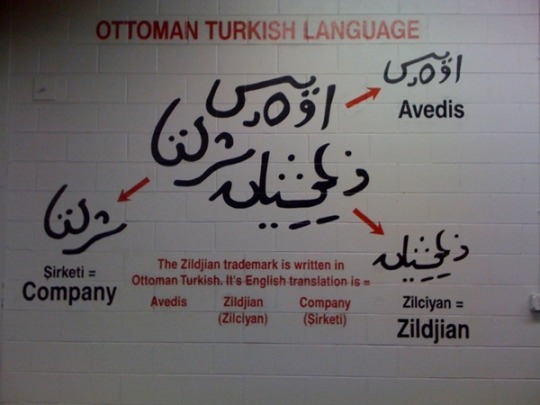

The Sultan Osman II the Young gave Avedis the name Zildjian (Zilciyân) (zil is Turkish for "cymbal," ci means "maker", and ian is the Armenian suffix meaning "son of"), and Avedis Zildjian began to manufacture cymbals for the mehter, Ottoman military bands consisting of wind and percussion instruments, which belonged to the Janissaries. Mehter ensembles performed during battle and performed courtly music for Ottoman rulers. The Zildjians also produced instruments for Greek and Armenian churches, and for Sufi dervishes. Zildjian worked primarily for the Sultan’s court. In 1623, because he was an Armenian, the Sultan had to grant him permission to leave the palace to start his own business. He set up shop in a suburb of Constantinople named Psamatia, and began to produce cymbals commercially.

In 1850, Avedis II built a schooner in order to sail cymbals produced in Constantinople to trade exhibitions such as the Great Exhibition in London, and to supply musicians in Europe, where Zildjian cymbals won many awards. Later in 1865, Avedis II died, and his brother Kerope II took over the company. He introduced a line of cymbals called K Zildjian, used by jazz and classical musicians to this day. Kerope II died in 1909 in Constantinople.

By the late nineteenth century, Aram Zildjian (Avedis’ son), who was then head of the family, was forced by the political conditions in Turkey to flee to Bucharest, Romania. The reality was, Aram had become so enraged by Turkish atrocities against Armenians that he had joined a (failed) plot to assassinate Sultan Abdul-Hamid II. Turkish police were able to track down the conspirators and Aram fled Turkey, settling in Bucharest. There, he set up a second Zildjian factory, while Kerope I's daughter Victoria ran the Constantinople factory. This arrangement continued until about 1927.

By 1910, Avedis III and his family also fled Turkey due to the country's increasingly volatile relationship with Armenia. The Zildjian family eventually settled in Boston, Massachusetts. While the Zildjian family situated themselves there, on the other side of the globe, the Armenian Genocide, also known as the Armenian Holocaust (the systematic mass murder and expulsion of nearly 2 million ethnic Armenians committed by the Young Turks and the Ottoman government) was well under way. As a matter of fact, during WWI, nearly 4 million Armenians, Greeks, Assyrians, and Yezidis were killed at the hands of the Ottoman Turks. Genocides the Turkish government denies to this day.

Around 1928, Avedis III, his brother Puzant, and his uncle Aram Zildjian (who had arrived in Boston the year prior) began manufacturing cymbals in Quincy, Massachusetts, and the Avedis Zildjian Co. was formed the following year in 1929. Avedis III’s father, Haroutiun had altogether left the Cymbal business to focus on his law career. In fact, at some point in the early 1900′s he managed to become Attorney General of Constantinople. If my memory serves me he later ended up in London or Paris. There’s a lot of other details I’m sparing here about the Dulgaryian cousins who took over the K factory in Istanbul against the wishes of the Zildjians, Aram losing interest in cymbal making, and about Avedis initially going into the confectionery business in Boston. Therefore, we’ll jump ahead about 40 years.

In 1968, Avedis split production into two separate operations, opening the Azco factory (at the suggestion of his son, Robert to be able to sell directly to the UK markets) in Meductic, New Brunswick, Canada. And in 1975, Zildjian began making K. Zildjian cymbals (the Zildjian family, some years prior bought back and soon after closed the Istanbul K factory from the Dulgaryians who were exclusively making Ks for Fred Gretsch and his famous Gretsch Drums) at the Azco plant. These were made until 1979. Within four years (1980), all K Cymbals were being made in the Norwell US plant. The A Cymbals line continued to be produced at the Meductic factory.

In early 1977, Armand Zildjian was appointed President of the Avedis Zildjian Company by his father. Soon after, Robert Zildjian split from the company amidst a conflict with his brother, Armand. In 1981, Robert named his new company, Sabian (The name 'Sabian' comes from the first letters of the names of Robert's three children: Sally, Andy, and Billy; and “ian” is the typical modern Armenian surname suffix) and started making Sabian cymbals in the Canadian Azco factory. Robert's son Andy (Robert passed away in 2013) is the most recent president of Sabian. (Most of this history and information is from Wikipedia, and others from an interview with Zildjian’s Director of Cymbal Innovation, Paul Francis... there’s a much more in depth analysis on this, and of cymbals and cymbal making over at Drum Magazine). This is where our modern day understanding of the Zildjians in North America begins.

“My problem is that Zildjian cymbals aren’t made in Turkey anymore. They’re made by an Armenian family here in the US.”

Zildjian family tree

All Zildjian cymbals have a stamp. It’s essentially a seal of authenticity. In fact, all metal products from Victorinox Swiss Army knives to Jean Paul brass musical instruments have a stamp.

A Sabian stamp consisting of their logo and Canada, the country they’re produced in.

The Zildjian Stamp

The stamp on Zildjian cymbals today have the trademark in Ottoman Turkish (Perso-Arabic characters) on top and below it in English. Underneath that it is indicated that it was produced in the USA, and below that might be a serial number. For one reason or another, the Zildjians continued to employ the Ottoman Turkish trademark and referring to their cymbals as “Turkish”. “Turkish” has come to be known as a style and sound of cymbal crafted to this this day by of course, Zildjian, Sabian, Instanbul Agop, Instanbul Mehmet, Bosphorus, Turkish, Smyrna, V-Classic, and other cymbal companies. All cymbal makers (aside from Zildjian and Sabian) who are based in Turkey have had in one form or another direct ties to the old K Zildjian factory. My problem is that Zildjian cymbals aren’t made in Turkey anymore. They’re made by an Armenian family here in the US.

Zildjian stamp of a cymbal that was made in Turkey.

I believe it is time for Zildjians to change their stamp. I believe they should change the top portion of the stamp to Armenian, and start referring to their cymbals as “Genuine Armenian Cymbals”. It just doesn’t make sense anymore to continue to refer to their cymbals as “Turkish” as their company is no longer based in Istanbul. And last I checked, the Zildjian family is still Armenian. I don’t think it reflects well on the company, the family, nor their history to continue to refer to their cymbals as “Turkish”. How can the Zildjians continue to refer to their cymbals as “Turkish” when their family’s DNA is in the cymbals their forefathers and foremothers handcrafted? Cymbals cherished and revered by musicians worldwide.

The Armenian Perspective

From my perspective it is a disservice to Armenians, particularly Armenian drummers and percussionists (many of whom are descendants of Genocide survivors) who proudly use Zildjian cymbals knowing the rich history of the family and company. Who know the history of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, and who also feel like they themselves are contributing to that rich heritage with their musicianship and art. I’ve never hid the fact that Zildjian cymbals are my favorite cymbals. I’ve used Sabian’s before and they’re great, after all they use the same family secret in their cymbal production. However, to me Zildjian cymbals sound the best and also maybe my affinity to them has to do with that fact that they still use their family name.

As I mentioned, I propose ZIldjian replaces the Ottoman Turkish trademark with Armenian text, and replaces the “Genuine Turkish Cymbals” tag with “Genuine Armenian Cymbals”. I think it make more sense. I also think it’s time the Zildjians honor their family heritage and history. At the very least, honor us Armenian drummers and percussionists who are descendants of Genocide survivors. I cannot think of a better time than the 105th Anniversary of the Armenian Genocide to do just that.

#zildjian#cymbals#zildjiancymbals#armenian#april 24#1915#april 24 1915#armenia#armeniangenocide#armenian holocaust#holocaust

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Behind the scenes with Stewart Copeland: Why dumb shit makes me happy (#1) - TRANSCRIPT

"If the only reason humans pro-create is Vivaldi, we would all be fucked…" -- Stewart Copeland

In this inaugural episode of the new ‘Backstage with Robert Emery’ podcast, RDCE talks to Stewart Copeland, the founder and drummer of the British rock band 'The Police'. Stewart talks about why he attributes studying 'Mass Communication & Public Policy' to becoming one of the worlds most famous drummers, why one of his balls is called Ben Hur, and how he grew up not knowing his Father was a spy.

Stewart is an American musician and composer. Apart from his most famous role as a rockstar, over the years he has produced film and video game soundtracks, written music for ballets, operas and orchestras, and in 2003 was inducted into the 'Rock and Roll Hall of Fame'.

This whistle-stop tour of his life takes us through his nine years in The Police with Sting and Andy Summers, his solo projects as a composer, and his predictions of the status of orchestral and rock music in twenty years.

Listen Now

Listen to the episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, Overcast, or on your favourite podcast platform.

Transcript

Hello, lovely people, and welcome to the inaugural episode of The Backstage Blog with me, Robert Emery.

This episode is brought to you with the help of LAT_56. LAT_56 are a sharp, smart and efficient baggage company that help you take off relaxed and arrive ready to take on the world. In 2011, I completed 122 flights and without their NASA-spec material making such a solid travel system, the hours spent with my luggage being thrown from one plane to another would have caused me a big headache. With their bold and strong aesthetics, they make no compromise to achieve the balance between performance and style.

With a lifetime guarantee, you'll be safe in the knowledge that their products will stand the test of time. When I first bought my travel bag from them, they only sold their flagship garment bag, an ingenious suit carrier that’s stylish, compact and crucially for me, going from gig to gig, didn't crease the suits. Since then, they've branched out to carry-on luggage, backpacks, duffel bags, laptop bags, and even wash bags.

Now, you know me, I’d only mention a company if I used and approved of them, and I do. And you know what? The thing I love about them the most is that after seven years of wear and tear, my first bag still looks as new as the backpack I bought just six months ago. So, if you're a busy traveller and want something that is stylish and secure, visit thebackstageblog.com and click on Partners.

Hello, lovely people. Today I'm really excited to be having a chat with my friend, rock god and all-round crazy gentleman, Stewart Copeland. Stewart and I first met at a gig. He was hitting the drums as loud as he could to the soundtrack that he composed for Ben-Hur. Scarily, I was conducting the orchestra who were duelling with him. It was like a baked bean and a baked potato had forgotten which one was little and which one was large. From that moment I picked up the baton, I knew that not only is Stewart one of the world's greatest drummers, and not only does he compose like a modern-day maestro, but after 44 years in the music industry, he still has the passion and energy of an 18-year-old.

I'll be honest, it's my first time recording an interview with me being the one asking the questions, so please forgive me: like any good art, it’ll take a while to perfect. Nevertheless, I hope you enjoy this worldwide whistle-stop tour of Stewart Copeland and his life.

Robert Emery: Okay, so welcome, welcome, welcome. I think the first thing I would like to talk to you about is your slightly crazy childhood because I'm pretty damn sure this has had an effect on what you've done in life later on. I've done a bit of reading and I know you were telling me–we're here somewhere in Europe doing Ben-Hur but we'll talk about that later. I know you were saying the other night about you had a very interesting childhood because, if I've got this right, you were born in the states, you grew up in Lebanon...

Stewart Copeland: You missed out a bit. Egypt.

Robert: Oh did I? Okay, Egypt. But then you went to boarding school in Somerset, then you're in a rock band, and then you ended up back in LA.

Stewart: A couple of steps missing there but fundamentally that’s the story, that's the arc.

Robert: It's a bit of a strange, unusual upbringing. What is the reason for that? How did that happen?

Stewart: My father was a diplomat, otherwise known as a spy. He was, during the war, in the OSS. His job was obviously the Nazis, but as the war was coming to a close, they realised that the Soviets were the real problem. And so even as they were finishing up winning the war together, the Soviets and the Americans, they were getting into the beginning of the Cold War. At that point, the energy from the Middle East was very important and so the CIA... As the OSS was morphing into this new thing called the CIA, my father was down in the Middle East and his job was to make sure that the oil came west to our factories rather than north to the evil empire.

To enact that mission, they imposed dictators upon the people such as when I was born, my daddy was away on business. I was born in Alexandria, Virginia, which is a suburb of the CIA. He was over in Cairo installing Gamal Abdel Nasser who ran Egypt actually pretty well for the Egyptian people. Across the Middle East, in Syria and the other countries, basically, their job was to keep a stable system. They were not interested in social engineering or in democracy; they were interested in stability. All the people of that generation, they were completely comfortable with the concept of dictators otherwise known as monarchs. The idea of absolute power. These people were... My father used to like to describe himself as amoral. He said he would never have anyone assassinated with whom he would mix socially, and I don't think he ever had anyone assassinated either but, you know, he was a storyteller. What did you ask me?

Robert: Just about your childhood. But did you know when you were growing up?

Stewart: That’s why I was there. No, I didn't know any of this growing up. In fact, it didn't seem exotic to me at all. In fact, it seemed to be lacking anything exotic because we didn't have TV and at the American school... I was in Egypt very young, but my memories really begin in Lebanon in Beirut and there was the American Community School. For a while, there was a rumour that in my generation, that's when the Saudis first started sending their young princes to get a Western education: the ACS in Beirut was the western school, the American School in Beirut. From my gen, it was the first time we started to see Arab kids, Gulf state kids, amongst the Westerners who were being educated there and Osama bin Laden was one of those.

Robert: Wow!

Stewart: Many years after me. Of course, if he'd been there when I was there, I would have kicked his ass. But we didn't have TV and the other American kids who had been home more recently would talk about this Xanadu, this fabled place called America. In fact, most people outside of America in my generation heard of America as the shining light on a hill where the streets are clean, and the people are, you know, everything works, and the systems are new and all this stuff, and... Then, gosh, there we were living in dusty old Beirut.

Of course, now looking back on it, I am so glad I grew up in dusty old Beirut. But then my father's best buddy, turned out to be a British double agent, name of Kim Philby, and his whole scene was kind of blown by that blow. My good buddy, Harry Philby, his dad disappeared one night. Two weeks later, he turns up in Moscow. True Blue English, he was recruited in Cambridge and was a mole and rose up in the Mi5 and there was three or four of them, I think. Anyway, my father had to ship his family out just like that. We were there for 10 years and then in a two-week period we are out of there.

I did one term in London, at the American School in London, but ended up in Somerset at Millfield. After that, I went to college in America and then came back to London where I met these other two guys.

Robert: So, it was after you went to the states and then you came back to London and that's where you met the other two guys as you call them. Okay, fine. But when did you start playing the drums?

Stewart: Hard to say. My father was a musician before the war. I’ve still got his trumpet; it's a 1942-con or something, I can't remember the year, I looked up the serial number. The fancy trumpet’s like the SG of its day. He only devotes two or three pages about his jazz life in his book but he played with both Dorsey brothers, Harry James, Glenn Miller–for him that's déclassé.

Robert: You grew up with music around you?

Stewart: When he started a family, he thrust musical instruments into all the kids and I'm the fourth child. By the time I came along, the house was full of abandoned instruments and I picked up all of them and I just was lost on all of them. My father spotted the tell-tale sign of a budding musician, which is “you can't get him to shut up.” Any kid that you have to say, “It's time for your piano practice,” don't waste your time or his time or her time. The tell-tale sign is that kind of autism... that you can't stop the kid, and I was on everything.

Trombone, I think, was the first lessons I had, but I couldn't get to the seventh position. But the buddy of mine had a catalogue, Slingerland drum catalogue, with pictures of drum sets which for me, I was like pictures of power, motors... Really, looking back now, as father of seven, I realise that the drum thing was partly because I was a very late bloomer. All the way through high school, even when I was 12-13, all my mates were growing faster. Their voices dropped, they started growing beards, they started turning into... and I was still that squeaky little kid.

The drums were power. Boom, bam, argh! Suddenly the squeaky little kid, now I'm a big silverback bastard motherfucker coming to eat your children. For a little 12-year-old who was this squeaky little 12-year-old, that was power. Looking back, adding up all the impressions and memories, I remember the first show–actually, the British Embassy Beach Club party at The St George Club. Janet McRoberts was there and I'm playing Don't let me be Misunderstood or an Animals’ or a Kink’s song or whatever, maybe House of the Rising Sun and there's Janet McRoberts on the dance floor with that look. And I thought, “Shit! Whatever this is, this is going to get me somewhere.”

Also, I remember at The American Beach Club, overhearing two of the 15- year-old girls talking. 15-year old girls are just like an impossible dream for a 12-year-old, you know, and they're talking about how Ian Copeland–who was the coolest kid in Beirut, by the way. He was the leader of the motorcycle gang, Ian Copeland was the coolest kid on campus. They’re talking, “Wow, I hear the Black Knights have got a new drummer. Oh, cool,” or hip or whatever. “Yeah, it’s Ian Copeland’s brother. Ian has a brother?” They’re talking about this mythical being, the new drummer in the Black Knights–is he cute? I’m standing there, I’m a little 12-year-old kid standing there with my ice-cream. These 15-year-olds are talking about Stewart Copeland as if it's somebody.

And so, these elemental, deep, crocodile-brain part of the drive, the emotional drive, are very powerful. My theory is that music is basically part of the procreative process of the human being. It's our mating dance. It's our mating ritual. As my mother the archaeologist would say, it's our plumage, and at that young age, particularly at adolescent age, music is so... With my kids, I see that music is so important to them. Here I do it for a living and I still wake up every day and can't wait to make more music but I can get through an hour without hearing music. My kids? It's the young mating dance. So that was a very powerful impulsion to playing drums.

Robert: So, you figured this is a very cool thing to do, you get lots of good attention for this and...

Stewart: Here’s is one more factor. My big brother Ian? Coolest kid on campus? Couldn't do it. Which was very unsettling because one of the American kids... What happened was the Black Knights’ drummer, his dad got shipped back to the states, the drums he was using which are borrowed or something like that were lying... And so they’re, “Well, let's get Ian. Let's get the coolest kid in the school to play the drums.” And he tried to do it and I could hear him in his room, the forbidden sanctuary. I could hear him trying to get it... then he’d roar off on his motorcycle and I’d sneak in on pain of death and I'd get on there, and I can do it. Wait a minute, that's not right, I must be doing it wrong for me to be able to do it what I heard him not able to do, my hero and older brother...

Robert: You didn’t have lessons?

Stewart: Immediately my father spotted, “Ah drums, great! Lessons!” And I had lessons at everything. The minute he spotted anything, “Lessons!” Yeah, right away.

Robert: Something definitely clicked with you with drums.

Stewart: Yeah and they stuck. The guitar kind of stuck, too. I played guitar all my life, never seriously, never took a lesson, never really developed anything beyond my favourite three chords. But those three chords? Ah, you can have a lot of fun on A, E and D. Throw a G in there, F sharp minor even.

Robert: Alright. The interesting thing for me though is that when I was growing up, I played the piano and I played the cello.

Stewart: Cello? Excellent instrument. A great blues instrument, by the way. You put that thing on your lap, play it like this, and it's a fantastic blues instrument.

Robert: But I couldn't do it. It didn't work for me. I just could not...

Stewart: The piano did, though, right?

Robert: The piano, I don't know why. I’d just sit there, play, it was easy, it just happened, you didn't have to think about it, I didn't really do any training to start with. It just happened. But cello, it did not happen. I could not get it to work. So did you try any instruments out when you were young?

Stewart: We’re going to have to work on a theory for that because pianotude you’ve got. That works for you. But two hands interacting to make one note seems to not work for you. I’m the other way around, see? Guitars, no problem. I can work on piano every day and I still can't play Mary Had a Little Lamb so you’ve got that gift.

Robert: Yeah. Yeah, but it's only piano. Piano conducting. But I tried many other things over the years, I tried clarinet for a while, couldn't do it, and it's just so concentrated what I can do with my music–what instruments. You sound like you're the sort of guy who can pick up anything, can give it a good damn go and have a bit...

Stewart: Whether I can or not, I will pick up anything and give it a damn good go.

Robert: And you have lots of instruments at home?

Stewart: I have the world’s largest collection of the cheapest instruments money can buy. I got trombone, I got bassoon. I got timpani. I got clarinet, I got viola, I got violin. I got cello. I got baby cello, I got bass guitar, lead guitar, rhythm guitar, acoustic guitar, banjo. I got all kinds of instruments.

Robert: And you’ve tried them all?

Stewart: Oh, yeah. Well, I get on eBay, then I haven't got a mellophone. So, I get on there and I look for mellophones or euphoniums; I love brass instruments above all. In fact, today I played an Alpine horn which is 15 feet long and guess what? A- Extremely light, made out of bamboo or something. B- really easy to play. Doesn't require a lot of breath at all, it's like playing on a trombone. Very impressed out there... [Makes a trumpeting sound] You know, not that hard.

Robert: Let’s just rewind back in time a little bit. You formed this band called The Police. How long was it from your starting point to all of a sudden something happened where you just went sky high?

Stewart: It was incremental, but every step headlining the marquee felt like a stellar, “That's it. We've made it. That's it, we're done. We're there now!” And then the next step happens and like climbing a mountain you think there's the shoulder there and we just get to there and that's going to be the top of the mountain–you get there and there's more mountain. It was very much like that. But we did star for a good two years, where we were playing the clubs and all of our gigs pretty much were cancellations by the genuine article punk bands of the day. We were a fake punk band. We were using the punk haircut as a flag of convenience because really, it's all about the hairdo. The stance.

Sting and I were both on the cusp, born in the early 50s. We were the tail end of the hippie generation where so by the time we got into our teens and wanted to rock out and be young adolescents or young adults, it was old and stale. Even though we were steeped in it–he was in jazz and I was playing in Curved Air, kind of an art rock band–we were still the tail end of the last generation. It was all stultified and everything, along comes Johnny Rotten and the Punk-O-Rama, and suddenly it’s just “burn it all down, bring it all down.” Musically, I had nothing in common with that except the fact that I like raw aggression in music. I like it. It's comedic actually.

I liked all that and they were like children and so Curved Air was running its course as an art rock band, so no problem. Cut the hair, peroxided blonde, turn my collar up, and let's go punk. And we did but the critics *[18:59] spotted us in a heartbeat as not the real thing. But fortunately, all the real thing, The Clash, The Damned, Eater, The Jam, all these bands, they didn't know how to hire a truck or a PA. They were managed by one of their mates who didn't have a clue, and so most of The Police's early dates were cancellations by other bands. I’d get a call on a Thursday afternoon saying, “Generation X can't make it.” I can. I got a Rolodex, I know three guys with a truck, I know three guys with a PA, I can get that together, I can get out to Islington, pick up that truck, the PA. “Fred, the PA, can you make the date? Sure.” I can pull it together and get that. And so all of our dates were like “not Gen X”...

Robert: I'm going to pressure you on this because I know you say it's incremental and I know you say it's like climbing a mountain, but I still believe that there must be one ... There must be a gem somewhere, a little story, a little something happened which put you on that clear direction.

Stewart: Many.

Robert: What is it? What's the one that comes to mind?

Stewart: If I had to pick out one, it's hard to say the one that was the payoff of all that which would be Shea Stadium where the Beatles played. And when you play at Shea Stadium, that's officially you have conquered America and you're in the footsteps of The Beatles. That was pretty darned exciting and it turned out to be the best show ever. We were a pretty hot band but some nights just really went to another level and we amazed ourselves. Actually, we were pretty full of ourselves most nights, but that was a particularly good night. Our first stadium, too. Then we got sick of stadiums.

Robert: So that was your first stadium, yeah?

Stewart: I think so. It felt like the first anyway but then we got to the top and then stayed there for a couple of albums before we were right at the top. There was no sign of the... The ascent was on a straight line when we threw in the towel because we had that folly of youth. Well, actually it turned out not to be folly. It turned out to be wisdom in a way of, “I don’t need these guys.” Usually when you hear band members say that, you try and advise them against it. But in our case it actually sort of turned out to be a good thing that we threw in when we did. We never saw the other side, the inevitable other side of the parabola. And so when we picked it up 20 years later, our thing was still pristine.

Robert: Crazy. So, you've done many, many things in your life and you've achieved an awful lot and I'll talk about composing in a minute. But first of all, do you have something that you have not yet achieved?

Stewart: Conducting. Watch your back, mate! I've been advised no matter how gifted I think I am, how easy I think it would be, don't, don't, don't, don't, don't. I'm already trying to establish myself as a real conductor.

Robert: Real conductor or...?

Stewart: A real composer. Throw in amateur conductor and the learning curve with that, and there's been a 30-year learning curve with writing for orchestra. I didn't pick this up overnight: I've been working at this and trying to figure this out for decades, and I'm sure conducting would be the same sort of journey. Which I would be really happy to make that journey. I'm in for the long haul on things. I'm good for the long mission. I conduct small-scale all the time–my singers, my soloist when I'm working in the studio, bringing the singers in, and I understand how to breathe for them and so that the indication... There's more than just there it's [breathing loudly] there. Those nuances and I understand the rhythm and I took a conducting seminar and I really enjoyed it. I did a movement of... What the hell was it? It was a big huge Bach movement or something. Not Bach... Anyway, it was fantastic.

Robert: How many players did you have?

Stewart: The musicians union sent about two or three chairs of violins, one of the brass. It was pretty skinny but all the different choirs were represented and it was really, really a lot of fun. The most fun part was that my reading’s much better now than it was then and putting the things in two, three, and... I just love that because the first lesson I’ve learned was the opposite of drumming where you groove and you are the groove and you feel the others... And there, you have to run ahead of the cart and you’re ahead. You’re not grooving with the band; you're pulling them. You're out in front.

Robert: I’ll do you a deal. The next time we do Ben-Hur, and we have time...

Stewart: Ben-Hur is hard.

Robert: Then I get you to conduct that, yeah?

Stewart: Let's do that. I will take you up on that with Tyrant’s Crush.

Robert: Okay.

Stewart: And you can play drums.

Robert: You don't want to see that. You absolutely don't want to see me play drums. I’ve tried before.

Stewart: You threw down the gauntlet.

Robert: Yeah, yeah, yeah, but you said you wanted to conduct. I never said I wanted to play drums. I’m happy playing...

Stewart: What's the quid pro quo here then?

Robert: That I get to laugh at you conduct.

Stewart: Done. Deal. I’d love it. I mean, who's got rehearsal time with 60 highly-paid musicians?

Robert: Okay, so you're a very busy guy and you've achieved a lot, you've conquered a lot, you've had very different aspects of your career, which means that you are a very driven person. You must be a guy who gets...

Stewart: It doesn’t feel like driven.

Robert: No, but you are. You must be.

Stewart: Compared... To me, other people they talk about this thing which is probably just as much as a mystery to you. The strange word, the strange concept called “procrastination.” Can you imagine? I mean, how's it possible to watch TV when you’ve got a mission to do? It's not a matter of being driven, it's just a matter of “there's a mission to do–let's go do that.” TV is for when you haven't got a mission or any... Eating food or sleep is for when you haven't got a mission. It doesn't feel driven or anything, it's just like...

Robert: What are the tips or the tricks or anything that you do to keep yourself energised, to keep yourself going, to get up in the morning to go and do what you need to do? Do you have like a ritual you have every morning for breakfast, or do you...?

Stewart: Well, yes. At my age, I have a ritual for everything because the running repairs on this battered old frame... You just figure out that if I go to bed this time and if I eat that and do this and don't do that, I guess my day is going to be better–and you have all these rituals. But I don't think any of these rituals are connected to motivation. I learned very early in life that daydreaming is a critical activity, that daydreaming isn't just wasting time. In fact watching TV– I'd rather stare out into space and imagine some great fantasy that I get to play my drum for the huge orchestra and I get to write all the music myself! And it goes [triumphant tune] and it's really fantastic. Just imagining this and imagining this...

If you have a daydream that really sticks and you keep going back to it, and you fill in the details of it and to make the daydream work better, you start filling in the details... It has to be realistic so the details that you add need to be substantiated by, “the way I got to being able to play with that big orchestra was that I met this guy. How did I meet a guy? Because I was...” Actually, what you're doing is concocting a scheme as the daydream. If it's a really powerful one that really draws you and you keep chewing on it and going back to it, you're actually working up a plan. Like we get the band with just three guys in it and one of them's got to sing. I have the guitar and the bass player’s... got to be a singer because my singing is terrible. And it'd be great... Before you know it, your daydream is a mission.

Robert: Do you think that has any connection whatsoever with the fact that you're a very talented musician and you've got an amazing gut feeling about music? Do you think the two are interlinked in any way, shape, or form?

Stewart: My oldest brother Miles, he is driven. He's driven, and he has excellent musical ears, but did not get the gift of creating art himself. He is a brilliant receiver of art. He understands the Zeitgeist and he's picked hits and he's had hits after hits after hits that he's had. My other brother Ian as an agent, same thing. Neither of them can play. Ian, the coolest kid in school, tried to play the bass and he can just about, but he did not get that gift. The driven thing...

Robert: So you believe you it is a gift?

Stewart: Yeah, absolutely. It is a gift. I don't know where it comes from, I'm so grateful for it, I'm humbled by the fact that I was granted this. I kiss the ground beneath my feet that I've been granted this gift. I do not feel that I earned it. I do feel an obligation in a way to service it and to... It is such a gift that I feel that it would be a crime for me to let it languish in a way. I don't know where that idea came from. Maybe my daddy taught me that or something.

Robert: Okay. So we’re doing here, in Basel, Ben-Hur...

Stewart: And you are the big orchestra and I get to write the music!

Robert: You’re such a crazy guy.

Stewart: That only took me 64 years to get that.

Robert: You went from being a drummer, a rock star, into a composer. It's a bit of a strange leap. I can't really think of anybody else who has done that...

Stewart: Once again, it wasn’t a leap. It wasn’t A and then a B. It was A– I guess the biggest leap was I got an incoming phone call from Francis Ford Coppola who says, could I come down to Tulsa, Oklahoma, where he's prepping–rehearsing, shooting a movie–and would I come there and just kind of like hang out and talk music and concept and stuff? So I get down there and the cast at that time, they're all kids. Every single one of them has now won an Academy Award. Diane Lane, Matt Dillon, I’m so terrible with names... Laurence Fishburne, Mickey Rourke, all of them. Dennis Hopper, they've all... But they were just kids; that's a diversion.

Anyway, so he just wanted to talk music and I got in there. Okay, I'm a little bit obsessive, and I said great. We talked high concept and he had this idea that... the reason he called me is time ticking, I remember like high noon... I want this teleological, inexorable movement of time with rhythm concept. You know, I love concept. Daydream: the result, the produce, the fruit of daydreams.

Robert: So he called you because he realised that the rhythm was such an important part and...

Stewart: Because his 18-year-old son says, “Dad, you gotta call Stewart Copeland from the Police.”

Robert: Okay, and then...

Stewart: And he did and I got in there, we bonded and his deal is that he finds people that he just senses has something, and he gives them their voice. He doesn't direct them. Oliver Stone told me every single note, “What's that note mean?” But Francis, once he got a connection, you're on the wavelength, he just turns you loose which he did and I had to figure out myself how to score a movie. Which I played that one all myself and I played mallards and weird guitar parts and funny little sounds. For them, since I didn't know how you do it, I had to invent the wheel for myself which is another word for–others applied this term and I was happy to accept it–revolutionary. That's not how you're supposed to do it but it's still...wow, that worked.

But at one point he did turn around and say, “I need some emotion. I need strings,” and immediately alarm bells, he's going to get some schlock artist in here, who’s going to like string... Francis, I got that. Yeah, you're right. We need some strings.

Robert: And that was the first time you'd worked with an orchestra?

Stewart: Yes.

Robert: So, you threw yourself into it at the deep end?

Stewart: Oh no, I’ve played in the school band.

Robert: Okay, yeah, but I mean as a professional... You threw yourself into the deep end as a composer who...

Stewart: I had these chords that I had worked out and I can play them one at a time. Okay that chord, okay stop the tape. Okay, play that chord and when it comes to the next chord it's... Okay roll the tape... Bang! And I can do that kind of thing. So for strings, all I had was footballs. Holders [singing sound]. I didn’t know how to write anything else. So, the first question is I call up a contractor and he says okay how many strings would you like? I go, how many? I don’t know. Strings.

Robert: Just strings.

Stewart: Strings. How many is strings? He says, Well, two guys is strings but it’s going to sound like two guys. If you want like I guess what Francis wants is a big wash of emotion. I don’t know, I think we ended up with maybe a dozen-20 guys, something like that. Somebody else looked at the chords and put it on a chart properly and I'm going, Yeah, I remember that from school. I actually did learn in college–I was at the California School of Performing Arts where I learned figured bass harmony and the fundam...

Robert: Figured bass, the most boring thing in the world ever.

Stewart: That's as far as I got.

Robert: If anybody out there doesn't know what figured bass is, don't even bother trying to Google it.

Stewart: It's critical.

Robert: No, it's not. It used to be critical. It’s now very, very boring and confusing.

Stewart: No. But what it did tell me is to not just do a barre chord up and down the neck like that, like a guitarist would do, and it tells you that you can use inner voices, let everything move in a different direction, and so on and so forth.

I was in a music school with other kids who'd studied the piano since the age of seven and I was the runt of the litter. One day she said, “Okay everybody, here's your homework. Write 16 bars.” Well-voiced chords for 16 bar. I had a million tunes in my head so I figured out something that I already and figured out applying the rules that I’d learned in her class to something I already had and she goes to the class and she plays okay by Johnny and she plays Johnny’s piece. Yeah, very good. Okay, yeah, good. Okay, Stewart... You’ve got a parallel fifth there and you haven't really resolved that but it’s kind of interesting the way that doesn't resolve there and resolves here. Now, you're not supposed to do this here, but there's kind of that note there. This would be what I would teach next year.

Robert: I remember this from being a kid.

Stewart: Yeah, and she finally ends up with, “Stewart, this is an actual piece of music.” And that totally at the bottom of the class, everyone just... They can sight read, they've done their ear training... I was just trying to become... I was starting at college age to learn the fundamental building blocks of music where everyone else in class had started much younger. I might have started playing music very young, but understanding the building blocks, the DNA of it.

So, as long as I was there. When I went to University of California in Berkeley, I didn't get into the music school. They gave me the ear training test and they played eight bars of a tune and transcribe it. They play me an interval, identify it, all this stuff: fail, fail, fail, fail, fail, fail, fail, fail. I studied instead, mass communication and public policy.

Robert: Mass communication and public policy!

Stewart: That's how I conquered the world.

Robert: Holy crap. Okay.

Stewart: Much more useful. If I had actually gotten into that music department at UC Berkeley, I would now be the timpanist in the Ohio Symphony.

Robert: Okay, so I'm going to try and back you into a corner here for something because you told me you've got a kind of philosophy about something. I forget what the phrase is that you use but something to do with being dumb.

Stewart: The dumb shit.

Robert: There you go. It’s the dumb shit. Okay. Can you just explain that?

Stewart: Well, artists, for instance, have very bad taste in whatever their art form is because we're slobs. The popular music, I hear it and I can dance. I don't mind it, I like it I guess. But what I really seek out are the things that are a little challenging that put a gimp on it that are .... I don’t mind pop music, I love it like everybody else. But what I seek out is something a little beyond and so I'll miss a hit.

My brothers... That's a hit! They can identify it and so on. I'm a little bit further out there. So, when I'm writing music or working on something, my manager will come and say, Stewart, that’s great but what's that? That's the best part! You see...Then like, you call it the best part–sounds like a wrong note to me. Oh. And I have to reconsider–it's the dumb shit. Actually that’s dumb ass. Sorry.

Robert: Dumb ass and dumb shit.

Stewart: Totally different things. Sorry, sorry, forgive me. I’m going to finish dumb ass first. So, he comes in with dumb ass in comprehending, unsympathetic to how many hours I've put into that artistic revelation. I need a dumb ass every now and then to come and pop my bubble and say, “I'm sure it's really on some intellectual plane, I hear what you're saying.” You need your bubble popped every now and then. Every artist needs some dumb ass, usually provided by spouses.

Robert: Okay. Yes. My experience...

Stewart: You get some dumb ass at home? Careful, careful, careful. Who’s in the corner now, bitch?

Robert: Yeah, you got me. Yeah, fair enough. She’s going to kill me.

Stewart: Let's talk dumb shit.

Robert: Dumb shit.

Stewart: Let's get into some dumb shit. A good example of dumb shit. I played the Letterman Show, big national American TV show and it's drum solo week. So I go in to play a drum solo and I have a piece of music that I wrote for a ballet, I work up a chart for the Tonight Show band and they're cracking players, those guys. We work up a thing and play, and I play my drum solo and at the end it took a lot of music to build that thing. Format, the piece of music, the writing, there’s the education writing, the charts that I practice. Years, a life in music went into making that thing–serious application, a vocation. And at the end of it... throw the sticks up there [swishing sound].

Well, go on social media, how'd that go down? It's all about the [swishing sound] Did you see how he threw the drumsticks? Yeah, wow, the drumsticks... That Copeland man it’s like he plays with these... the drumsticks!

It’s the dumb shit. No matter how much vocation went into every other aspect of that performance, it was the dumb shit.

Robert: It is the dumb shit that the audience identified.

Stewart: It’s something that stands out. I mean, I’m sure they were very impressed by everything else, they wouldn't have been impressed by the thing unless they were impressed by all the rest of it subliminally, but the thing that caught their eye and that they're talking amongst themselves about is that odd little piece of nothing, that throwaway little something.

Robert: Okay, so here comes the corner. You like the dumb shit, the audience likes the dumb shit, but you don't write music which is dumb shit. You write music which is not always easily accessible. It can be but not always. It's very intelligent music.

Stewart: You're answering your own question.

Robert: No, I'm not because I don't get it. If you know an audience likes dumb shit, why don't you write dumb shit?

Stewart: Here's the two things going on. Remember how here's the main stream of where everyone else and I'm kind of running parallel and not quite bull's eye level? That's me here, see? All the dumb shit’s here, see? Up here, trying to connect with that thing, occasionally I throw in some dumb shit and that's the connection. And I understand that my music is a little astringent for some, perhaps. What I find to be a comfortable easy place in musical atmosphere might be not... Sort of disturbing or not... People gravitate towards feeling good and what makes me feel good sometimes it makes other people feel sad.

Robert: But why are you not...

Stewart: As a professional film composer, I got pretty good at identifying exactly what chord has... You know, this is happy, that’s sad, this is happy sad, and this is sad. There's a big difference, believe it or not. Now, as a technician, I understand perfectly how to go for this emotion or that emotion but my personal taste is you describe it as being slightly off centre and I'm flattered. I take that as a compliment.

But the dumb shit is to drop the barrier, to break the ice, to welcome aboard... I use it as a way to break the ice. Instead of being alienated... Oh, that was weird. Oh, ha-ha-ha, that's kind of funny at least, or whatever. So, I’d be careful that I have first of all, I do my thing, then I get a little dose of dumb ass... Telling me, dude, this is like a little out there, and then reminded by dumb ass, then I go and apply some dumb shit.

Robert: And then it makes everybody happy.

Stewart: Well, it makes me happy. It seems to work. I've played my... I’ve used it in front of really adverse audiences and seemed to get a result.

Robert: You're so good at answering questions, I genuinely can't tell whether I managed to back you into that corner successfully, or whether you wriggled out of it. But I don’t care. You’re very good at it.

Stewart: That's the briar patch. Please don't throw me into the briar patch. No, not the briar patch. Oh, you're throwing me into the briar patch! No, no, no. Okay.

Robert: Tell me. 20 years’ time, what's the business going to be like? What do you think is going to be happening with orchestras, with pop, rock music? 20 years’ time, what would be your prediction?

Stewart: I don't know how orchestras will survive but I would say that they will probably be branded and that because they have a champagne quality that applies sophistication to a product, that they will be useful as... and hopefully government institutions will recognise the value of here's an art form, here's a body of our culture that cannot sustain itself commercially. It cannot. An orchestra, 60 guys or 90 guys or 110 guys, they cannot sustain themselves as a commercial enterprise. They need either private donations or government donations. Where’s the world going to be in 20 years? I would suspect that orchestras will be, as they are now, be vehicles of what they can do, which is impart dignity upon a product.

Robert: Okay, and what about rock, pop?

Stewart: It will always be here. It always has been, always will be. For rhythm... Simple EAD chords, all the revolutions of music. It’s all about the haircut, change the haircut, change the style of music, first you grow it long and then you cut it short. I remember my mom saying, “Stewart, why can't you have long hair like all the other nice boys and girls?” Because mine was like [scraping sound] peroxide. Everything about my outward appearance said, “Fuck you, I'm going to eat your children.” That was the intent. Whereas I was a little soft little...

Robert: Oh, you were a timid soul inside. Bless you. All right, so that's your prediction. Just jumping back a bit.

Stewart: Well, here's the thing. There will always be rock music because if there isn't rock music, there will not be sex, and if there is not sex, there will not be anybody. It’s a part of our natural process.

Robert: It is now, but what...

Stewart: It always has been.

Robert: Well, you say that, but what about when Beethoven was around?

Stewart: When Beethoven was around was not early.

Robert: Beethoven was the kind of rock music of his day. I mean, he was so challenging when he wrote some of his music, and I'm sure that would have been the element of it.

Stewart: I suspect that Beethoven was not the rock music of his day. I suspect that Beethoven was the pampered servant of rich people and their sophisticated sublimated carnal desires. But out there on the streets of his town, the people were dancing into the streets, not to Bach music. That's my suspicion, I just made that up. That’s going to be a guess. Your readers or your listeners will write in and say, No, no, no, not sex. But I'm sure popular music of his day would have been rhythmic and would have been dancing and would have given the male of the species and the female of the species an opportunity, an impulsion and an audio permission to thrust their pure dander at each other, and to display their genetic superiority through body motion inspired by music. That's what music is.

Mozart? Bach? Those are sophistications like many other of our crocodile- brain behaviours. Are sophisticated and turned into a high form; humans do this. We take fire and we turn it into a jet or the internal combustion engine. That's what we do to fundamental building blocks of physics, that's what we do. And the fundamental building blocks of our music, which is part of our libido, which is part of our mating dance, you can develop that and it turns out the combination of physics, the human mind and sex produces high forms of art. But that's not what's really going on. Those are like the caveman drew on the painting because he had... High art painting is not necessarily where it came from, but that throb, rock ‘n’ roll, Bach was not that. Bach was not rock 'n' roll. He's like the rock star of his time. That's his position in society but that's not the function of his music.

Robert: Yeah, but for instance, Paganini who of course...

Stewart: He was popular.

Robert: Yes, he was like the rock star of his time and he went bankrupt...

Stewart: And Mozart too, by the way, was in the streets and inspired by music the people were actually dancing to.

Robert: And Vivaldi Four Seasons, it's incredible music but...

Stewart: I'm surprised that they have any population in Europe at all. I'm surprised that they’re here... In fact, my whole theory, I'm just here begging to throw it all because I just made it up anyway as I was talking. Out the window. You see, Europe would be depopulated now if they were trying to procreate to the sound of Vivaldi. If that's the only reason humans procreate, is Vivaldi, we would have been fucked.

Robert: That's a brilliant quote. That's going to be the headline quote on this podcast. Great, okay, fine... Who knows, who knows? It’s a prediction about what’s happening in 20 years’ time...

Stewart: Get this. Who would have ever (thought) that the most effective music that gets right to the deepest part and releases all social training and everything and gives young males and young females of our species utter permission is a mechanised rhythm that comes from a machine. [EDM sounds] To the extent that it’s human is to the extent that it's less effective in releasing the libido and permitting these behaviours that would be utterly unacceptable without the presence of a strong beat.

In fact, people standing in a room, they’re not interested in procreating. There's music going but they're not even thinking about it. Their body’s moving to it. There's more to it than meets the eye. There's something deeply physiological, something evolved very deeply in our human behaviour.

Robert: Okay. And you yourself, you live quite a simple life, you don’t have a big empire with 100 orchestrators and...

Stewart: No. I don't have an engineer. I used to. All the people of my generation, their work day begins when the engineer shows up and when the engineer “got to go home to see my family,” then the artist, that's the end of his working day.

Robert: And this is kind of a bit of an ethos of yours, is keep it small, keep it to yourself.

Stewart: Absolutely. The Police was three guys and it was designed that way. I wanted this... Let it be three guys. And I have my own record company that I did my gosh darned self... What's the cheapest studio in London? Pathway, an eight-track studio. Well, let's go there, and I call the guy and I chisel him down. Yes, strip it back and strip it back so that you've got manoeuvrability is the main thing.

Robert: But do you not think though, if you have more people working with you, collaborating, working for you, that you can achieve more in life because more people are doing the stuff that you don't necessarily need to do?

Stewart: Actually, that has been someplace that I'm getting to. I am in the process of arriving at that happy place where I can give it up. All during my young Pac Man years and adulthood, I've always been very greedy of artistic “boss hood.” I want to play every instrument myself, and I want to record everything myself, and I want to mix it myself, and I don't want anything to happen with me out of... I got to be in it, I want to be into everything. The video-I want to make the video, and the video should be like this and it should be... Just like the idea of not owning every aspect of it is kind of alien.

But now with the passage of time, I've discovered that like a producer is really cool because all I have to do is do this and then he has to clean up the tapes and figure it out and do all this stuff. I've learned to give it up, to let other people play with the ball, and the results can be really good. In a band, you collaborate. I'm not talking about a band collaboration because there, it's a corporate identity and I feel that I don't have to do everything in the band, but the band has to do everything. The band has to decide on the album cover, the band has to decide what the video is going to be about. We're not going to have anybody tell us what to... And so in a band, it's a corporate identity. The band is me, it's my band, even though there's two other guys who call it their band. For each of us, it's my thing.

The thing that I will never have, even as much as I'm prepared to give it up artistically, I will never acquire an empire. I have no need and no desire for an empire. I look at fellow composers who have built empires, some very effectively. One of my erstwhile competitors, Hans Zimmer who’s a big film composer and he does incredible work...

Robert: He’s Swiss, of course. Swiss.

Stewart: Is he?

Robert: Yes.

Stewart: Of course, is he? I always thought he was German or Austrian but okay, Swiss. He has an empire. He has 10 guys. He learned to give it up. I don't have to write every bar. Or he writes the theme and I don't have to apply it to this unit, apply that theme to... I can have somebody do it for me, then check it. Then when he's done all the donkey work–of here's the start time, there's the art time, this is the BPM that lands on the chord and does all the... The craftsmanship part of it. He’s written a tune and that’s the art. Then the craftsman applies it to the scene and then the artist comes by and says, okay that works but you know what I'm going to do... And so he gets all the fun part.