#source: james kerwin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

SOCA THERAPY - FEBRUARY 2, 2025

Soca Therapy Playlist

Sunday February 2nd 2025

Making You Wine from 6-9pm on Flow 98.7fm Toronto

Saddle (Dr. Jay Plate) - Anika Berry

Bet Meh (Muv Short Edit) - Machel Montano

Kettle Pot - Yung Bredda

Dotish - Lyrikal

Retro (Muv Short Edit) - Voice

Retro (Dr. Jay Plate) - Voice

Forever Young (Muv Short Edit) - Olatunji

More Gyal For Me - Juby

Bless Me - GBM Nutron

Raise Up The Vibe - Adam O x Choppi

PARDY - Machel Montano

The Great Escape - Patrice Roberts

Forever - Nailah Blackman x Skinny Fabulous

Road Meeting - Fay-Ann Lyons x Syri Lyons x Travis World

Touch D Road - Bunji Garlin x Travis World

Explore (Remix) (Clean) - V'ghn x Nailah Blackman x Travis World

Together - Nadia Batson

Higher Power - Mical Teja

Flatten - Voice x Bunji Garlin

Ultimate Party - Krosfyah

TOP 7 COUNTDOWN - Powered By The Soca Source

Top Songs By Edwin Yearwood Streamed on Spotify

7. Feels Like Home Again - Edwin Yearwood

6. Dushi - Krosfyah feat. Edwin Yearwood

5. Road Jam - Krosfyah feat. Edwin Yearwood

4. Sak Pase - Edwin Yearwood

3. Wet Me - Krosfyah feat. Edwin Yearwood

2. Sweating - Krosfyah feat. Edwin Yearwood

1. Pump Me Up - Krosfyah feat. Edwin Yearwood

Talk To Me - Kes

Tack Back - Kes x Tano

Junction - Coutain x Tano

Aye Gyal - Hey Choppi x Chalmer John

When Last (Remix) - GBM Nutron x Jus Jay King x Grateful Co

Runaway (Radio Edit) - Mical Teja

Never Leave Ya - Kerwin Du Bois

Flirt - Farmer Nappy

One Piece - GBM Nutron x Tano

Cocoa Tea - Kes

Cocoa Tea (Vintage Remix) - Artificial Intelligence

Party With You - H2O Phlo

Take Me Home - Freetown Collective

PAN MOMENTS

Iron Park 2025 Medley - Trinidad All Stars Steel Orchestra

TANTY TUNE

(1992) The Phung Uh Nung Sweet - The Mighty Duke

Wine - Burning Flames feat. Onika Bostic

Own It (Muv Short Edit) - Imani Ray

Is Mas - Patrice Roberts

In A Mess - Problem Child

Feting Family - Shal Marshall

Best Friend - Shal Marshall

Hot Gyal Performance - GBM Nutron

Down Dey - Melick

Good Medicine - Jaiga

Medicine (D Ninja Edit) - Kes

Jamtown - Coutain x Tano

Hero (DJ Ste Intro) - GBM Nutron

Welcome To Soca - Kerwin Du Bois

Bumpa - Machel Montano

No Way - Kris Kennedy

Music Is Life - Nessa Preppy x M1 x Dj Spider

Riddim - Mical Teja x Coutain

The Greatest Bend Over (Mr Vik Band Edit) - Yung Bredda

The Greatest Bend Over - Yung Bredda

The Truth - Machel Montano

No Sweetness - Kes

Good Spirits - Full Blown

NORTHERN PRESCRIPTION

Crabs In Ah Barrel - Elsworth James feat. Devon Metro

What A Feeling - Krosfyah feat. Edwin Yearwood

Follow Dr. Jay @socaprince and @socatherapy

“Like” Dr. Jay on http://facebook.com/DrJayOnline

0 notes

Text

Development Project 1: Part 1

This is my first development project for this semester. I chose to develop the "Nostalgia and Memories" assignment and push it further. In the initial project, I had created an old TV that we used to have in our family's mountain house. The TV symbolises more than just an object to me, which is why I had chosen it as a living representation of my past and memories. For this project, I wanted to represent my sense of nostalgia as well by creating an environment that could embody the TV asset I had made earlier. For this reason, I decided I wanted to create a version of home away from home inside of Unreal Engine 5 that could potentially be a game environment. I really wished to represent my country and heritage in some way through my art, so I chose to put my TV asset in the environment of a typical Lebanese house similar the the one my family used to spend the summer in.

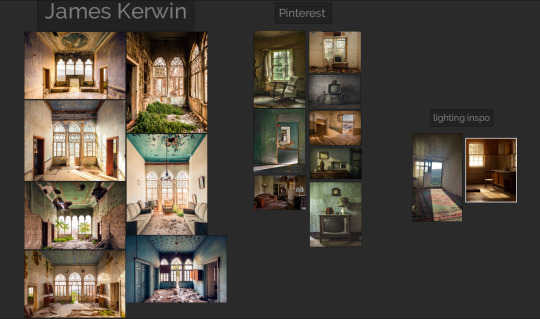

I first began by searching for reference images online that would help me materialise my concept. I came across the work of James Kerwin, a photographer who has a project called Lebanon; A Paradise Lost, which is dedicated to capturing the beauty of abandoned places of heritage in Lebanon (https://jameskerwinphotographic.com/portfolio-series/lebanon-a-paradise-lost/). I chose photographs that I felt reflect Lebanese architecture the best, notably the ones that show the triple arch, a typical architectural staple in Lebanon.

As for the other references that I ended up using, I found them on Pinterest. These images helped me visualise things like wall and floor textures as well as arbitrary object composition that is present in abandoned places.

For the lighting, I found two pictures on Pinterest as well, which I thought were very appropriate for the mood I was going for: I wanted the ray of sunshine to enter windows and hit the interior of my scene in that same manner. I kept them open while lighting the scene to use them as guides.

Sources:

jameskerwinphotographic.com. (2020). LEBANON; A PARADISE LOST - James Kerwin Photographic. [online] Available at: https://jameskerwinphotographic.com/portfolio-series/lebanon-a-paradise-lost/.

0 notes

Text

Poveglia Island, Italy

Welcome to the Island of Poveglia. This abandoned island is where thousands of diseased, murderous, and insane people were laid to rest. A place so creepy and disturbed that most locals dear not travel to it. The Romans decided this secluded island located between Venice and Lido would be perfect to dump off people infected with the bubonic plague. With the history of this island associated with death and plague after these events, the island was later used for future epidemics. Bodies were taken to the island, tossed into mass graves, and then burned. The island was essentially made of human bones and ash.

Years later a mental hospital was built on Poveglia to house anybody showing symptoms of physical or mental illness. Just like any mental hospital in history, the doctor that ran the place wasn’t exactly ethical. He would conduct cruel experiments on his patients, including lobotomies. The doctor met his end when he “fell” off the bell tower. According to stories, the doctor actually survived the fall but was surrounded by a mysterious mist that dealt the final blow to end the doctor once and for all.

Source: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/off-track-planet/poveglia-island-like-hell_b_4188986.html

Photo credit: James Kerwin Photographic

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Morehead Planetarium

Morehead Planetarium and Science Center is located on the campus of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It is one of the oldest and largest planetariums in the United States having welcomed more than 7 million visitors by its 60th anniversary in 2009.[1] As a unit of the university, Morehead receives about one-third of its funding through state sources, one-third through ticket and gift sales, and one-third through gifts and grants.

First opened in 1949, the planetarium was used to train Gemini and Apollo program astronauts in celestial navigation.[2] Until the late 1990s, it contained one of the largest working Copernican orreries in the world. The facility was donated to the university by alumnus John Motley Morehead III who invested more than $3 million in the facility.[1]

Morehead Planetarium opened on May 10, 1949 after seventeen months of construction. The first planetarium in the South, it was the sixth to be built in the United States.[3] Designed by the same architects who planned the Jefferson Memorial, the cost of its construction, more than $23,000,000 in today’s dollars, made it the most expensive building ever built in North Carolina at the time. Morehead Planetarium was officially dedicated during a ceremony held on May 10, 1949.[1]

https://goo.gl/maps/G9D1MmcxBMoNAzoZ7

The sundial in front of Morehead Planetarium.

Since Zeiss, the German firm that produced planetarium projectors, had lost most of its factories during World War II, there were very few projectors available at the time. Morehead had to travel to Sweden, where he had previously served as American ambassador, to purchase a Zeiss Model II to serve as the heart of North Carolina’s new planetarium.

Let There Be Light was the planetarium’s first show.

NASA[edit]

From 1959 through 1975 every astronaut in the Mercury, Gemini, Apollo, Skylab, and Apollo–Soyuz Test Project programs spent hours in celestial navigation training at the planetarium. Morehead technicians developed simplified replicas of flight modules and tools for use in the training, often from plywood or cardboard. A mockup simulating key parts of the Gemini capsule was constructed from plywood and mounted on a barber chair to enable changes in pitch and yaw.[4] Several of these items are on display at the planetarium. That training may have helped save astronauts’ lives on occasion. Astronauts aboard Apollo 12 called upon that training after their Saturn Vrocket was hit by lightning twice during ascent, knocking spacecraft systems offline and requiring them to configure navigation systems based on fixes taken manually. Gordon Cooper used his training to make the most accurate landing of Project Mercury after a power failure affected navigational systems.[5] Astronauts enjoyed soft drinks, cookies and other snacks during their intense hours-long training session, leading planetarium employees to create the code name “cookie time” to refer to the training sessions. Occasionally, word of the sessions leaked out and noted clothing designer and Chapel Hill native Alexander Julian recalls meeting Mercury Astronauts during a visit to the planetarium while in junior high.[1]

The first astronaut to train at Morehead, in March 1964, was Neil Armstrong. Armstrong visited again only months before the 1969 launch of Apollo 11, spending a total of 20 days at Morehead over 11 training sessions, more than any other astronaut. Astronauts commented that the “large dome” was “highly realistic”, calling the facility “superb”.[4]

In all, the astronauts who trained at the planetarium were Buzz Aldrin, Joseph P. Allen, William Anders, Neil Armstrong, Charles Bassett, Alan Bean, Frank Borman, Vance D. Brand, John S. Bull, Scott Carpenter, Gerald P. Carr, Eugene Cernan, Roger B. Chaffee, Philip K. Chapman, Michael Collins, Pete Conrad, Gordon Cooper, Walter Cunningham, Charles Duke, Donn F. Eisele, Anthony W. England, Joe Engle, Ronald E. Evans, Theodore Freeman, Edward Givens, John Glenn, Richard F. Gordon Jr., Gus Grissom, Fred Haise, Karl Gordon Henize, James Irwin, Joseph P. Kerwin, William B. Lenoir, Don L. Lind, Anthony Llewellyn, Jack R. Lousma, Jim Lovell, Ken Mattingly, Bruce McCandless II, James McDivitt, Curt Michel, Edgar Mitchell, Story Musgrave, Brian O’Leary, Robert A. Parker, William R. Pogue, Stuart Roosa, Wally Schirra, Rusty Schweickart, David Scott, Elliot See, Alan Shepard, Deke Slayton, Thomas P. Stafford, Jack Swigert, William E. Thornton, Paul J. Weitz, Ed White, Clifton Williams, Alfred M. Worden, and John Young.[5][6]

source https://plumbinggiant.com/morehead-planetarium/ source https://osmianannya.tumblr.com/post/189168997964

0 notes

Text

Morehead Planetarium

Morehead Planetarium and Science Center is located on the campus of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It is one of the oldest and largest planetariums in the United States having welcomed more than 7 million visitors by its 60th anniversary in 2009.[1] As a unit of the university, Morehead receives about one-third of its funding through state sources, one-third through ticket and gift sales, and one-third through gifts and grants.

First opened in 1949, the planetarium was used to train Gemini and Apollo program astronauts in celestial navigation.[2] Until the late 1990s, it contained one of the largest working Copernican orreries in the world. The facility was donated to the university by alumnus John Motley Morehead III who invested more than $3 million in the facility.[1]

Morehead Planetarium opened on May 10, 1949 after seventeen months of construction. The first planetarium in the South, it was the sixth to be built in the United States.[3] Designed by the same architects who planned the Jefferson Memorial, the cost of its construction, more than $23,000,000 in today’s dollars, made it the most expensive building ever built in North Carolina at the time. Morehead Planetarium was officially dedicated during a ceremony held on May 10, 1949.[1]

https://goo.gl/maps/G9D1MmcxBMoNAzoZ7

The sundial in front of Morehead Planetarium.

Since Zeiss, the German firm that produced planetarium projectors, had lost most of its factories during World War II, there were very few projectors available at the time. Morehead had to travel to Sweden, where he had previously served as American ambassador, to purchase a Zeiss Model II to serve as the heart of North Carolina’s new planetarium.

Let There Be Light was the planetarium’s first show.

NASA[edit]

From 1959 through 1975 every astronaut in the Mercury, Gemini, Apollo, Skylab, and Apollo–Soyuz Test Project programs spent hours in celestial navigation training at the planetarium. Morehead technicians developed simplified replicas of flight modules and tools for use in the training, often from plywood or cardboard. A mockup simulating key parts of the Gemini capsule was constructed from plywood and mounted on a barber chair to enable changes in pitch and yaw.[4] Several of these items are on display at the planetarium. That training may have helped save astronauts’ lives on occasion. Astronauts aboard Apollo 12 called upon that training after their Saturn Vrocket was hit by lightning twice during ascent, knocking spacecraft systems offline and requiring them to configure navigation systems based on fixes taken manually. Gordon Cooper used his training to make the most accurate landing of Project Mercury after a power failure affected navigational systems.[5] Astronauts enjoyed soft drinks, cookies and other snacks during their intense hours-long training session, leading planetarium employees to create the code name “cookie time” to refer to the training sessions. Occasionally, word of the sessions leaked out and noted clothing designer and Chapel Hill native Alexander Julian recalls meeting Mercury Astronauts during a visit to the planetarium while in junior high.[1]

The first astronaut to train at Morehead, in March 1964, was Neil Armstrong. Armstrong visited again only months before the 1969 launch of Apollo 11, spending a total of 20 days at Morehead over 11 training sessions, more than any other astronaut. Astronauts commented that the “large dome” was “highly realistic”, calling the facility “superb”.[4]

In all, the astronauts who trained at the planetarium were Buzz Aldrin, Joseph P. Allen, William Anders, Neil Armstrong, Charles Bassett, Alan Bean, Frank Borman, Vance D. Brand, John S. Bull, Scott Carpenter, Gerald P. Carr, Eugene Cernan, Roger B. Chaffee, Philip K. Chapman, Michael Collins, Pete Conrad, Gordon Cooper, Walter Cunningham, Charles Duke, Donn F. Eisele, Anthony W. England, Joe Engle, Ronald E. Evans, Theodore Freeman, Edward Givens, John Glenn, Richard F. Gordon Jr., Gus Grissom, Fred Haise, Karl Gordon Henize, James Irwin, Joseph P. Kerwin, William B. Lenoir, Don L. Lind, Anthony Llewellyn, Jack R. Lousma, Jim Lovell, Ken Mattingly, Bruce McCandless II, James McDivitt, Curt Michel, Edgar Mitchell, Story Musgrave, Brian O’Leary, Robert A. Parker, William R. Pogue, Stuart Roosa, Wally Schirra, Rusty Schweickart, David Scott, Elliot See, Alan Shepard, Deke Slayton, Thomas P. Stafford, Jack Swigert, William E. Thornton, Paul J. Weitz, Ed White, Clifton Williams, Alfred M. Worden, and John Young.[5][6]

source https://plumbinggiant.com/morehead-planetarium/

0 notes

Text

Morehead Planetarium

Morehead Planetarium and Science Center is located on the campus of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It is one of the oldest and largest planetariums in the United States having welcomed more than 7 million visitors by its 60th anniversary in 2009.[1] As a unit of the university, Morehead receives about one-third of its funding through state sources, one-third through ticket and gift sales, and one-third through gifts and grants.

First opened in 1949, the planetarium was used to train Gemini and Apollo program astronauts in celestial navigation.[2] Until the late 1990s, it contained one of the largest working Copernican orreries in the world. The facility was donated to the university by alumnus John Motley Morehead III who invested more than $3 million in the facility.[1]

Morehead Planetarium opened on May 10, 1949 after seventeen months of construction. The first planetarium in the South, it was the sixth to be built in the United States.[3] Designed by the same architects who planned the Jefferson Memorial, the cost of its construction, more than $23,000,000 in today’s dollars, made it the most expensive building ever built in North Carolina at the time. Morehead Planetarium was officially dedicated during a ceremony held on May 10, 1949.[1]

https://goo.gl/maps/G9D1MmcxBMoNAzoZ7

The sundial in front of Morehead Planetarium.

Since Zeiss, the German firm that produced planetarium projectors, had lost most of its factories during World War II, there were very few projectors available at the time. Morehead had to travel to Sweden, where he had previously served as American ambassador, to purchase a Zeiss Model II to serve as the heart of North Carolina’s new planetarium.

Let There Be Light was the planetarium’s first show.

NASA[edit]

From 1959 through 1975 every astronaut in the Mercury, Gemini, Apollo, Skylab, and Apollo–Soyuz Test Project programs spent hours in celestial navigation training at the planetarium. Morehead technicians developed simplified replicas of flight modules and tools for use in the training, often from plywood or cardboard. A mockup simulating key parts of the Gemini capsule was constructed from plywood and mounted on a barber chair to enable changes in pitch and yaw.[4] Several of these items are on display at the planetarium. That training may have helped save astronauts’ lives on occasion. Astronauts aboard Apollo 12 called upon that training after their Saturn Vrocket was hit by lightning twice during ascent, knocking spacecraft systems offline and requiring them to configure navigation systems based on fixes taken manually. Gordon Cooper used his training to make the most accurate landing of Project Mercury after a power failure affected navigational systems.[5] Astronauts enjoyed soft drinks, cookies and other snacks during their intense hours-long training session, leading planetarium employees to create the code name “cookie time” to refer to the training sessions. Occasionally, word of the sessions leaked out and noted clothing designer and Chapel Hill native Alexander Julian recalls meeting Mercury Astronauts during a visit to the planetarium while in junior high.[1]

The first astronaut to train at Morehead, in March 1964, was Neil Armstrong. Armstrong visited again only months before the 1969 launch of Apollo 11, spending a total of 20 days at Morehead over 11 training sessions, more than any other astronaut. Astronauts commented that the “large dome” was “highly realistic”, calling the facility “superb”.[4]

In all, the astronauts who trained at the planetarium were Buzz Aldrin, Joseph P. Allen, William Anders, Neil Armstrong, Charles Bassett, Alan Bean, Frank Borman, Vance D. Brand, John S. Bull, Scott Carpenter, Gerald P. Carr, Eugene Cernan, Roger B. Chaffee, Philip K. Chapman, Michael Collins, Pete Conrad, Gordon Cooper, Walter Cunningham, Charles Duke, Donn F. Eisele, Anthony W. England, Joe Engle, Ronald E. Evans, Theodore Freeman, Edward Givens, John Glenn, Richard F. Gordon Jr., Gus Grissom, Fred Haise, Karl Gordon Henize, James Irwin, Joseph P. Kerwin, William B. Lenoir, Don L. Lind, Anthony Llewellyn, Jack R. Lousma, Jim Lovell, Ken Mattingly, Bruce McCandless II, James McDivitt, Curt Michel, Edgar Mitchell, Story Musgrave, Brian O’Leary, Robert A. Parker, William R. Pogue, Stuart Roosa, Wally Schirra, Rusty Schweickart, David Scott, Elliot See, Alan Shepard, Deke Slayton, Thomas P. Stafford, Jack Swigert, William E. Thornton, Paul J. Weitz, Ed White, Clifton Williams, Alfred M. Worden, and John Young.[5][6]

source https://plumbinggiant.com/morehead-planetarium/ source https://plumbinggiant.blogspot.com/2019/11/morehead-planetarium.html

0 notes

Text

Did NASA Really Send Astronauts 1000 Times Further Than They Can Today – 50 Years Ago?

I grew up as the biggest fan of the “moon missions”, idolizing them since I was a child. As a four year old in 1969, my Air Force Major father gave me a VIP publicity packet of “Apollo 11” pictures. It contained a dozen 9×12 color photographs of the mission, which I thereafter hung on my cherished bedroom wall shrine to immortalize the occasion.

I saw these pictures of “men on the moon” every day for ten years, or some 3650 times, from the age of four to fourteen, before I even considered the possibility of their falsification. Fortunately, as a fourteen year old, I was still open-minded enough at the time to consider, at least the possibility of, a grand government deception about the technologically unrepeatable moon landings, done on the first attempt with 1960’s equipment, yet impossible today, even with 50 years of improved rocketry and computers.

If I went into all the proof of the moon landing fraud, it would take a book, which I am presently writing with the hope of an early 2020 release. Just ask yourself if there has ever been a technological advancement in the entire history of the world, such as the first airplane, the first automobile, or nuclear power, that was not far surpassed 50 years later, much less no one on earth was able to even repeat it 50 years later? Just ask yourself if there has ever been an occasion in the entire history of the world in which precious 175 billion dollar technology, and all of the original records and videos of it, were intentionally destroyed afterwards? (Only done so to hide the evidence of the fraud.)

I am a big fan of Mike Adams and Natural News. He is one of the ultimate “Truthers” on the planet. At the same time, I am fearful that this moon-landing-fraud subject is too controversial even for him. Yes, I believe that the earth is a sphere and that manned space travel into earth orbit is possible, and that unmanned probes beyond that are possible as well. This is about arrogant government corruption and their falsification of scientific data, not geography. The shape of the earth could be a triangle, and our federal government is still corrupt beyond imagination. If they are corrupt enough to kill millions of innocent people in repeated needless wars, then I think they are capable of counterfeiting one accomplishment in a television studio.

We have to take a stand for the Truth, even if it is unpopular or sounds “crazy”. Mike, if you publish this article on Natural News, I will give you a chance to have the exclusive first release of the following information, which I was previously reserving for my 2020 book’s release.

One of my high-ranking military sources observed the filming of the first “moon mission” himself. He did not want his testimony published until ten years after his death, which has now passed, for fear that his family could be murdered as retaliation. He was even warned of this specific penalty, face to face by threatening superiors, 50 years ago when he first eyewitnessed the “moon landing” being filmed inside of two airplane hangers at Cannon Air Force Base in Clovis New Mexico.

It was June 1-3 in 1968, about a year before the first official “moon landing” supposedly took place. President Johnson said that the United States federal government was going to achieve martyred Kennedy’s goal to put a man on the moon by the end of 1969, “Come hell or high water!” The only way for the President to assure its success, and not risking killing three national heroes on live international television, was to stage it, like a bluff in poker.

President Johnson personally authorized the faking of the moon landing in order to guarantee its success. Therefore, the military code name for the deception was called “Slam Dunk”, in that by faking the moon mission, thus guaranteeing it, made it a “Slam Dunk”, or an easy victory.

President Johnson gave my military source, who was the security chief for Cannon Air Force Base, his personal list of names whom he permitted to enter the facility in order to observe the unusual event. President Johnson himself was there for the first of three days of filming on the elaborate “moon” set, which was supervised by the United States Air Force’s “Special Operations Unit” and the Central Intelligence Agency’s “Slam Dunk” task force.

These are the names, in the order in which they appear, on President Johnson’s list of permitted visitors into the secure airplane hanger inside of Cannon Air Force Base . . .

Lyndon Johnson – President

Neil Armstrong – NASA Astronaut

Edwin Aldrin – NASA Astronaut

Wernher von Braun – Rocket Designer

Robert Emenegger – Image Consultant

Eugene Kranz – NASA Flight Director

James Webb – NASA Administrator

Joseph Kerwin – NASA Astronaut

Thomas Paine – NASA Administrator

Glynn Lunney – NASA Flight Director

Christopher Kraft – NASA Founder

James Van Allen – Radiation Expert

Arthur Trudeau – Army Intelligence

Donald Simon – Unknown (Navy)?

Grant Noory – Unknown (CIA)?

Even though President Johnson was eligible for reelection the following year, as he only served a quarter-term after President Kennedy’s assassination, he smartly decided not to run. Historian’s assumed that this was because of the controversial Vietnam War, yet Nixon was elected twice by landslides regardless of the same. The real reason for Johnson staying out of the Oval Office in 1969 was that the faking of the moon landing was about to occur, and who knew if that would work? If Johnson got caught doing it, that would be one heck of a legacy to leave for all time, so he adamantly avoided that potentiality.

Democrat Johnson instead meticulously laid the groundwork for the moon landing fraud, which Republican Nixon obviously approved, yet was still too fearful of it to even show up for the historic launch, literally distancing himself from it, should the deception unravel. This should show us clearly that the battleground before all Americans is not “Democrat vs. Republican”, as that is just as much of a distracting ruse as the moon landings are. The dragon for all Americans to slay is the United States federal government, who’s CIA murdered Kennedy, attacked their own soldiers to enter the Vietnam War that killed a million souls, and who had the arrogant audacity to siphon 175 billion dollars from the people under their care to stage the moon landings, thereafter spending the money on all of these illegal murderous activities.

If we do not put a stop to all of this, then American’s hard earned money will be used to buy the very bullets to kill their own honest countrymen, who are in the process of exposing this corruption for the benefit of all. Exposing the moon landing fraud is just the right medicine that the sick American nation needs, as the disclosure of this outrageous deception would finally bring about a much needed overhaul of the corrupt United States federal government and its many rogue “intelligence agencies”.

I recently confirmed the details of this foregoing information with my military source’s son, who house was then burglarized a few days later. The only things stolen were the documents relating to this event. A few days after this, he received two more visitors, this time face to face, who threatened the lives of his children if he spoke of his father’s participation in the moon landing fraud to a journalist ever again. I have notified the Tampa FBI to provide whistleblower protection for him.

My sources name, who was the head of security at Cannon Air Force Base in 1968, who personally eyewitnessed the faking of the first “moon landing” there inside of two airplane hangers converted into a large television studio, was Cyrus Eugene Akers.

I produced a half million dollar documentary on this subject (linked below), which was entirely financed by a prestigious board member of an aerospace company that builds rockets for NASA. He knows from an engineering point of view that the supposed moon rocket did not have enough fuel to leave earth orbit, that the lunar module batteries did not have the capacity to run air conditioning nonstop for three days against an outside temperature of 250 degrees F, and that antique NASA computers, which were one-millionth as fast as a cell phone, did not have the ability to calculate thousands of mile per hour trajectories in real time without inadvertently killing the crews. This is precisely why all of the moon landing equipment, the specifications, the flight data, and the original videotapes, were intentionally destroyed afterwards. This itself is proof of the fraud, because if you spent 175 billion dollars to develop a real technology, the last thing you would do is destroy all of the costly hardware and data afterwards.

Here we are, fifty years later, and instead of space travelers being in another solar system by now, having been to Mars ten years after the moon landing, four decades ago, and with several established moon bases there today, none of which ever happened, NASA can now only send astronauts one-thousandth the distance to the moon, even with five decades of better rockets and computers. If I told you that Toyota, 50 years ago, made a car that could go 50,000 miles on one gallon of gasoline, yet today, with five decades of better technology, their best car can only get 50 miles per gallon, or one-thousandth the distance, you would easily recognize the first claim as the forgery that it was.

If it were not for people’s pride and emotional attachment to this grandiose boast, they too would equally recognize the unrepeatable claim, also with only one-thousandth the capability fifty years later, as the corrupt government fraud that it sadly is. Seeing how it is impossible for technology to go backwards, which it seemingly has, though only in this one instance in the entire history of the world, it can only mean that the 1969 claim was a scientific forgery. It is that simple, and that corrupt.

youtube

The post Did NASA Really Send Astronauts 1000 Times Further Than They Can Today – 50 Years Ago? appeared first on NaturalNewsBlogs.

The post Did NASA Really Send Astronauts 1000 Times Further Than They Can Today – 50 Years Ago? appeared first on Clean Energy Health.

from WordPress https://cleanenergyhealth.com/did-nasa-really-send-astronauts-1000-times-further-than-they-can-today-50-years-ago/

0 notes

Text

Development

The man producer Richard Kobritz called upon to get him his vampire in SALEM’S LOT is Tobe Hooper, the director of THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE and the last person one might expect to find directing a glossy production for a major studio much less one intended as a television miniseries. Yet the hiring of Tobe Hooper is only one incident in a production chronicle almost as complex as the story of SALEM’S LOT itself, which comes to TV November 17th and 24th on CBS. Stephen King’s 400-page novel of vampirism in contemporary New England was acquired four years ago by Warner Brothers, who intended to produce it as a theatrical feature. At the outset, King and the studio agreed that he would not write the screenplay. He was busy with his own projects as a novelist (in less than a year, King’s career would begin to soar). So Warners was left with the task of finding someone to adapt King’s brilliant but complicated plot into something manageable as a normal movie and without sacrificing the elements that made the book so powerful. But over the course of the next two years, the studio was unable to come up with a satisfactory screenplay. Stirling Silliphant (who had adapted IN THE HEAT 0F THE NIGHT and more recently THE SWARM, and was also producing for Warners), Robert Getchell (ALICE DOESN’T LIVE HERE ANYMORE) and writer/director Larry Cohen (whose independent feature IT’S ALIVE was a surprise sleeper for Warners in 1974) all contributed screenplays all of them rejected by studio brass. SALEM’S LOT was becoming not only an impossible project, but a source of frustration: CARRIE, a King novel filmed by Brian DePalma, was released in late 1976 and began racking up enormous profits. Warners was sitting on a potential goldmine, but could do nothing with it.

“It was a mess,” King recalls. “Every director in Hollywood who’s ever been involved with horror wanted to do it, but nobody could come up with a script. I finally gave up trying to keep a scorecard.” At one point, if only because Warners was running out of writers and directors to consider, Tobe Hooper’s name was mentioned in connection with the SALEM’S LOT movie. But by then, interest in the project at the theatrical division was beginning to flag. Finally, it was turned over to Warner Brothers Television, in the hope that a fresh approach and the possibility of financial interest by a network would revitalize it.

Enter Richard Kobritz. Kobritz was the 38-year-old vice-president and executive production manager at Warner Brothers Television who had hired John Carpenter to direct a striking 1978 suspense telefilm, SOMEONE IS WATCHING ME, starring Lauren Hutton. As a genre buff with an eye for new talent (Carpenter went on to direct HALLOWEEN three weeks after finishing SOMEONE. . .), Kobritz at least stood a fighting chance of making some sense out of SALEM’S LOT. Kobritz began by reading the already completed screenplays. “They were terrible,” he says. “I mean, it isn’t fair to put down anyone’s hard work, but the screenplays just did not have it and I think some of the writers would probably admit that. Besides, the book is admittedly difficult to translate, so much is going on. And because of that, I think it stands a better chance as a television miniseries than a normal feature film.” So the decision was made to turn SALEM’S LOT into a miniseries and thereby lick the problem of its unwieldy length. Actually, though the production is technically labeled a miniseries, it is basically a four hour movie (31/2 hours, figuring commercial time) scheduled for successive nights. Emmy winning television writer Paul Monash was contracted to write a new, first-draft teleplay. Monash had created the landmark dramatic series, JUDD FOR THE DEFENSE (about a flamboyant lawyer in the F. Lee Bailey mold) during the late ’60’s, and as a producer was responsible for the features BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID, THE FRIENDS OF EDDIE COYLE, SLAUGHTERHOUSE FIVE and Brian De Palma’s CARRIE. Monash had also been producer of the mid-60’s TV series PEYTON PLACE, a credit that Kobritz, who has referred to SALEM’S LOT as “Peyton Place turning into vampires” was aware of. Clearly, one key factor in a viable teleplay would be an intelligent combination of the huge number of characters in SALEM’S LOT. Monash pulled it off.

“His screenplay I like quite a lot,” King offers enthusiastically. “Monash has succeeded in combining the characters a lot, and it works. He did try a few things that weren’t successful the first time. In one draft he combined the priest, Father Callahan, and the teacher, Jason Burke, as a priest who teaches classes and it just didn’t work, so he split them up.

“Some things were left out because of time, some because it’s television,” says King. “My favorite scene in the book is with Sandy McDougall, the young mother, where she tries to feed her dead baby, and keeps spooning the food into its mouth. That won’t be on TV, obviously.”

Other changes were made by Kobritz, who takes a strong creative interest in the films he produces. His three major alterations to Monash’s first script were: To characterize the vampire, Barlow, as a hideous, speechless fiend, not the cultured villain carried over from the novel, to have the interior of Marsten House, which looms over the town of ‘Salem’s Lot, visually resemble the vampire’s festering soul and to keep Barlow in the cellar of his lair, Marsten House, for the final confrontation with the hero (in the book he is billeted in the cellar of a boarding house once his mansion is invaded) a concept Kobritz would later say, “works in the book but wouldn’t in the film.” Kobritz also pushed the killing of an important female vampire to the climax, to give her death more impact and provide the film with a snap ending.

With the example of such turgid, dramatically impotent “evil in a small town” miniseries as HARVEST HOME before them, Kobritz and Monash were determined to make SALEM’S LOT work despite the television restrictions against frightening violence. The project would be designed as a relentless mood piece where the threat of violence, rather than a killing every few minutes sustained terror. And it would be cast with an eye toward good actors first, and TV names second.

But still, there was the matter of all those stakings, and a relentless murderer with no redeeming virtues. “CBS worried about a few things in the screenplay,” King explains. “They worried about using a kid as young as Mark Petrie is in the book, because you’re not supposed to put a kid that young in mortal jeopardy, although they do it every day in the soap operas. “Paul Monash finally sent them a memo that I think covered it. He pointed out, for one thing, that CARRIE which was a CBS network movie was the only movie that ever cracked the top five in the weekly ratings.”

Casting

Next came casting. From the instant Barlow was designed to symbolize “the essence of evil,” Kobritz had in mind Reggie Nalder whom he remembered from Hitchcock’s THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH, and genre buffs recall from that film, Michael Armstrong’s MARK OF THE DEVIL and Curtis Harrington’s THE DEAD DON’T DIE. Kobritz’s idea was to recreate the Max Schreck vampire from Murnau’s 1922 NOSFERATU.

In a quirky touch, Kobritz also hired genre veteran Elisha Cook, Jr. (HOUSE ON HAUNTED HILL THE HAUNTED PALACE) and former B movie queen Marie Windsor to play Weasel, the town drunk, and Eva Miller, the landlady with whom he’d had an affair years before.

“That was an inside joke we threw in right from the start,” Kobritz concedes. “I’m a Stanley Kubrick buff, and on purpose we’ve reunited them 23 years later after THE KILLING. In the script, it says Eva and Weasel were at one time married and then got divorced, so it was funny to think of that same couple from THE KILLING, 23 years later, now divorced, but still living together. It was also the first time since then, I think, that they’d worked in a movie and had scenes together.”

The rest of the casting was less frivolous, and reflected the seriousness with which Kobritz wanted the whole enterprise to be regarded. Kobritz sent James Mason a copy of the Monash teleplay, offering him the role of Straker, the European antique dealer who has Barlow smuggled into Marsten House and whose character had been expanded in the absence of a speaking Barlow. Mason loved the part and agreed to make his first appearance in a television drama since the medium’s early days (several years earlier, he had not been told that 1974’s FRANKENSTEIN: THE TRUE STORY was not intended for theatrical release).

Key supporting roles went to Emmy nominee Ed Flanders (Bill Norton, a composite character who became both the heroine’s father and the town doctor), Lew Ares (Jason Burke, the local teacher) and Geoffrey Lewis (Mike Ryerson, the gravedigger). Bonnie Bedelia, an Oscar nominee 10 years ago for THEY SHOOT HORSES, DON’T THEY?, was cast as Susan Norton, who is on the verge of leaving ‘Salem’s Lot before she meets Ben Mears, played by David Soul.

David Soul? Though the hiring of Soul may shock or disappoint readers of the book who know him only through STARSKY AND HUTCH, it marks a shrewd move by Kobritz (which is discussed at length in his interview). Soul’s acting ability may sometimes have been concealed in STARSKY AND HUTCH, but it wasn’t in the telefilm LITTLE LADIES OF THE NIGHT, which happens to be the highest rated TV movie ever made. His presence therefore guarantees an audience. “I think the casting of David Soul is fine,” says King. “I have no problem with that at all.”

Soul also offers a strong counterpoint to Lance Kerwin (who starred in the well reviewed, but poorly rated-1978 NBC series, JAMES AT 16), selected to play Mark Petrie. Kerwin has a brooding presence that undercuts his superficial physical resemblance to Soul, and the two actors, who join forces to destroy the vampires at the end of the film, project a strange chemistry when seen together.

Production & Direction

SALEM’S LOT was budgeted at $4 million, about norm for a prestige miniseries, with financing split between CBS and Warner Brothers and a European theatrical release was planned from the start. It would, naturally, be shorter than miniseries length, but it would also contain violence not included in the TV version for example, the staking of vampires would not occur below the camera frame, and one death in particular Bill Norton’s impalement on a wall of antlers would be seen in graphic detail, while shot in a markedly restrained fashion for television. Because of his oft stated goal of having SALEM’S LOT like a feature, not a TV special (whether it was to be released theatrically or not), Kobritz and his staff handpicked production personnel capable of providing the right texture and depth under deadline pressure. Jules Brenner, who had shot the impressive NBC miniseries HELTER SKELTER, signed on as cinematographer; Mort Rabinowitz, a 23-year veteran of the film industry who was art director for Sydney Pollack’s CASTLE KEEP for which he and his staff built a castle in Yugoslavia) and THEY SHOOT HORSES, DON’T THEY?, was hired as production designer; and Harry Sukrnan, an Oscar winning composer (SONG WITHOUT END), who wrote the excellent music for SOMEONE IS WATCHING ME and whom Kobritz describes as “a former cohort and protégé of Victor Young,” was contracted to score SALEM’S LOT. And Tobe Hooper was enlisted as director. Following a chain of events Kobritz describes at length in his interview, Hooper was deemed the only appropriate person to direct SALEM’S LOT. Kobritz had screened for himself one recent horror film after another usually films by highly praised neophyte directors. Some of the features Kobritz found intriguing. Others, like PHANTASM, he remembers with a shudder of disbelief. None impressed him like THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE. Hooper was called in for a meeting with Kobritz, and was signed.

It is important to note that the selection of Hooper did not signify an attempt to mimic the intensity of TEXAS CHAINSAW in a television show, which would be frankly impossible. Kobritz was searching for a filmmaker with a confident visual style, a mastery of camera movement, and an ability to follow a script and adhere to a tight schedule. There was, apparently, never any concern that Hooper would not be able to direct a film that did not contain a large quota of violence. “I think it goes without saying that if a man has a strong visual style and is also able to meet those other qualifications, his skills encompass more than the making of violent movies,” says Kobritz. “I knew Tobe was our man from the day I met him. And he’s come through like a champ.”

Hooper was signed in late spring of this year, and one of his first tasks was a field trip to the location that would be used for most of the exteriors of ‘Salem’s Lot. In 1977, Tony Richardson had directed a Warner telefilm, A DEATH IN CANAAN, which was supposed to be set in a small, contemporary Connecticut town. Ferndale, a northern California town 16 miles south of Eureka, and 75 miles south of the Oregon border, doubled perfectly as a bogus Connecticut location. Anna Cottle, associate producer for SALEM’S LOT, had been Richardson’s assistant. She remembered Ferndale and particularly the cooperation of the local inhabitants. After a brief scouting trip, Ferndale was chosen for SALEM’S LOT.

But in all of Ferndale, there was no house which could be used as a double for Marsten House, so Rabinowitz and his staff were dispatched to Ferndale to build one. They found a cottage on a hillside overlooking Ferndale and the Salt River Valley; it was decided to build a full-scale mock up of Marsten House around the existing cottage complex, complete with a stone retaining wall and several misted, dead trees. The family residing in the cottage was paid $20,000 and guaranteed all of the lumber from Marsten House once shooting was completed. The filming of SALEM’S LOT began on July 10 in Ferndale. “It took 20 working days to build Marsten House from scratch,” Rabinowitz recalls. “We put the last touches on it very late at night before shooting was to begin. I remember, my assistants and I were up there painting, and someone drove on by the road just below us. All of a sudden, he slammed on his brakes and backed up, got out of his car and just stood there staring at the house. ‘My God, I’ve lived here 25 years,’ he said, `and I never noticed that house before!’ I played along and just said, ‘Gee, I don’t know we’re just tourists.'”

Rabinowitz estimates the cost of the exterior Marsten House mock up as $100,000. Another $70,000 was spent constructing the interior of the house Kobritz’s rotting embodiment of the vampire’s soul back at the Burbank Studios. The interior rooms and passages of Marsten House posed the more difficult challenge for Rabinowitz and his staff. For one thing, there was the problem of creating atmosphere without going overboard.

“It’s a very difficult line,” admits Rabinowitz. “By the nature of the writing, you’re going into a theatrical abstraction, and you must take it further than normal, but not too much further. It’s trial and error. When I designed the interior, the first shots were way over, which I knew they would be, and I had to be careful in bringing them down not to lose all the gory description and so forth. When it’s that fine a line, I’ll intentionally go overboard and then gradually shave it back and back. I’d say it was two weeks from the first still photos and testing of the color lighting to the final result.

“I used a lot of plaster, no I could make huge craters all over the entire set and furniture so that it looked as though it was pock-marked, and from some of these larger openings in the walls I put a kind of epoxy or resin, and let it drip as if it were oozing from the interior, as if it were an open wound. We wanted a rotting, sick appearance, almost as if in discussions with the director and producer, we were looking into the body, the heart of the vampire. It reflects his whole being more so than just a decayed house. So we decided to go for an abstract image.

“Then,” Rabinowitz continues, “in front of the camera, we took the same material in medium shots and close ups and just loaded it up so it would ooze and pour right in front of you. Sometimes it’s very clear and at other times it’s not too obvious, just a little glistening in the background. “There’s a dark, greenish tint to the interior. We put down glaze after glaze after glaze, for the proper amount of sheen, and then various shades of green, mixing it up with other colors to that it wasn’t solid green.”

Two other important duties for Rabinowitz were the building of the antique shop (Strakers business front) and the small South American village where the beginning and end of the film are set.

“The Latin town was shot on the Burbank back lot and the San Fernando Valley Mission,” says Rabinowitz. “We used the interior of the mission church, and I built an adobe style native but on stage.

“My decorator, Jerry Adams, who is fantastic was responsible for most of what you see inside the antique shop. Ninety percent of what you see is his taste initially directed by me. But the individual pieces all Jerry Adams. I also have an assistant, Peter Samish, who is only 28 but is brilliant. He’s the son of Adrian Samish, the producer and former head of CBS who was not popular among many people. So Peter has not gotten where he is because of papa, he had a very rough time. But he was just to creative and inventive on this picture.”

Rabinowitz, a stickler for accuracy, found that one of his most perplexing assignments was to come up with a coffin for Barlow. “It was designed special,” he notes, “because there was no way to find anything like that. The research was difficult to come by, it’s a 400 year-old coffin but once I did find it, our cabinet shop and our antique shop here is so superb that they gave me exactly what I drew up, right on the nose. If I’d had to work at another studio, I don’t think it would have come out as well, because they are superb—just the finest in our business.”

Rabinowitz tries to be a perfectionist. A professional painter and sculptor, he has taught at UCLA and USC, and spends six months of each year at his Santa Fe, New Mexico studio, painting and sculpting for galleries. At 53, he is still excited by what he terms “that marvelous madness that is Hollywood,” and he still finds his work there a challenge. For SALEM’S LOT, in the rush of production for television, there are things he would do over if time allowed.

“There is one interior of the Glick boy’s bedroom,” Rabinowitz confesses “where I overdid the color and blew the gag. I absolutely telegraphed it by making the room a somber brown, so when the scene opens you’re in that mood already. Then, when the vampire arrives, it’s not as big a surprise. It’s still a very effective scene, but I’d have toned down my part of it more.”

In his interview, Hooper speaks of Rabinowitz with genuine awe. Rabinowitz worked closely with Hooper, and feels he developed an understanding of his personality. “He’s very good natured, extremely so,” says Rabinowitz, “very warm, but very laid back. He’s quite shy. But once he gains your confidence and you gain his, that stops. Was he articulate? With me, yes. He was very articulate. With others, not so much. It took time. It’s a personality kind of thing. But he knows exactly what he wants.”

But getting what he wants was another matter entirely for Hooper, particularly in the case of David Soul, who was also under pressure to perform. According to Soul, Hooper was articulate in relating to him what he wanted.

“I believe he is a good actor’s director and I believe he will be even more so,” observes Soul. “I think the problems of this film, which were primarily the special effects, the vampire obviously, and the fact that we were shooting out of continuity, made it difficult for him to spend the kind of time with the actors he’d have liked to.

“Many, many times we’d pull each other aside to talk and he’d say, `Goddammit, David, I’m sorry we can’t spend more time working out these relationships, but this just isn’t the time to do it so just hang in there.’ He was concerned that everybody on the set was happy. He’s a very gentle, very, very bright man. This picture, if nothing else, will seal his future, as an important director along with the Steven Spielberg’s, the John Carpenters, the John Badhams people like that.” Soul, who was cast two months before the start of production, was able to make suggestions that helped define his character a little better, but he feels some inconsistencies remain.

“Yes, there are a lot of inconsistencies, built into the script because the producers felt that since it’s television, there needs to be this reiteration of the fears on Ben Mears’ part so the audience is constantly aware. That for me is not giving the picture everything it could have. There are only so many times Ben Mears can say, ‘Did you ever have the feeling something is inherently evil?’, you know? There are a million other ways to say that same thing. I much prefer the scenes such as the entrance of Straker with his cane, which comes far closer to creating true terror than dialogue can.”

The scene with the cane the first meeting of Mears and Straker, helps illuminate Soul’s working relationship with Mason.

“There was a certain kind of awe to my working with Mason,” Soul explains, “and I used that for the relationship between the two characters: Mears is intimidated by Straker. It sounds simplistic, but it works. I did not try to get to know Mason better, so it was as if, in my early scenes with him, this imposing stranger could be the evil coming from the house. And only as we got further into the picture did my curiosity as David Soul—and certainly as Ben Mears—manifest itself in a kind of relationship with the character. So I kept away from him in the beginning. Also, the may Tobe staged our scenes heightened the element of surprise. The scene where I meet him as he’s walking with the cane is very well staged by Tobe, because I’m staring at the house and feeling all those disturbing sensations and memories and I back out almost out of the shot and then” Soul gasps “there he is behind me. These kinds of cinematic devices helped a lot, and that’s Tobe.

“I was impressed by both Tobe and Mason. There were a lot of impressive people on this film, actors especially. Lew Ayres was the same as Mason in a way, though he was a little difficult to crack. He’s a very orthodox and tough actor. He was a matinee idol, and he considers himself still to be a star. But once that was broken down, it became a very warm relationship.

“Mason is fascinating. He’s better than most TV actors and he’s also a personality. He’s got a mystique that he’s built up forty years and that’s what you’re watching also, and what you’re playing opposite. I was surprised to find out how organically he works, he had a whole history for Straker. His conversations about the character were very intelligent.

“How did I change my own TV personality and still play a hero? It’s a good question. I don’t have a pat answer. Obviously, they’re different characters. I think the accouterments changed me somewhat the glasses, the clothes. Also, I cleaned up my speech pattern a little bit. I sound like a writer, a man who’s at home with words. In STARSKY AND HUTCH, it was always dip-dip-dip, sort of half-finished sentences, a street jargon and repartee. This time, I stuck with the lines and the discipline of a well written script. There’s also a mysterious quality to Ben Mears and I tried to work with that. I didn’t socialize a lot. It was a rough part, and in a sense, I let the neuroses that were building up in David Soul because of the pressure work for the character.

“That’s one area in which Tobe was very helpful and understanding. He listened. “Have I seen THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE? No, but I do want to, very much, after working with Tobe.”

Hooper, who’s career literally reached a standstill a year after his arrival in Hollywood, is a living testament to the difficulty of maintaining a career in the horror genre. Shortly before he was approached by Kobritz for SALEM’S LOT, Hooper had even met with Italian producers over the possibility of directing THE GUYANA MASSACRE, before his agent blew the whistle on the project (“God bless him,” Hooper now says). Hooper openly admits that SALEM’S LOT pulled him from obscurity.

“Look,” says Hooper, “this is a quantum leap for me. SALEM’S LOT is my best picture, and there’s no question about it. It’s a major studio production, I’m working with a fantastic cast and crew. And Kobritz is wonderful. This is a first for me.” But is it the same Tobe Hooper in SALEM’S LOT that we saw in THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE or even EATEN ALIVE? Can the same audacious spirit run through something created for television? “Oh, I think so,” Hooper replies. “For one thing, my style is ingrained in me. It does not change. It improves, perhaps, but it does not change. Also, SALEM’S LOT does not rely on the same kind of dynamics as CHAINSAW. It is scary, it is atmospheric, but in a different way. I do not have to cheat the audience to bring it to television.

“The style of my films is not their violence. Violence has sometimes been an ingredient in them, but because I shoot it a certain way, people may have thought that is the style all by itself. You know, I made a number of short and feature films before I entered the genre with TEXAS CHAINSAW, and they didn’t contain violence, but my style was developing nonetheless in each of those films. “Part of the idea of SALEM’S LOT is to bring the audience into the movement, in a way the camera moves almost constantly. I am leading the audience on, but I’m satisfying them too, I’m not cheating them. They’re not going to expect a dollar’s worth of scare and get 75 cents worth of talk. And you can do that without slicing someone up with a chainsaw.”

In fact, there is relatively little dialogue in SALEM’S LOT. The narrative is advanced primarily in cinematic terms through camera movement and editing, and through scenes that establish perspective in a strictly visual way. Kobritz’s desire for this effect, and his need for a director who could add to his and Monash’s ideas, not just catty them out was the main impetus behind the hiring of Tobe Hooper.

One of Hooper’s most striking scenes of barely glimpsed violence is the murder of Dr. Bill Norton by Straker, who picks him up and heaves him across a room into a wall embedded with antlers. Hooper’s camera carries the audience right along with Norton, holding on a dose shot of Norton’s horror struck face up to and including the moment of impact. Because the actual impalement is not seen in a wide shot, the scene is technically acceptable for network TV, and Hooper’s surprise trick of dragging the audience along on the victim’s death ride assures both shock and terror.

In another sequence, Hooper and his special effects team employ a coffin’s eye view of the inside of a grave, to involve the audience in the resurrection of one of the Glick brothers. In his interview, Kobritz explains the mechanics of two of SALEM’S LOTS most elaborate effects: the vampires’ contact lenses and the shot in reverse levitation scenes. Hooper discusses their emotional quality. “I invented those,” Hooper says, “working with the makeup and special effects people. The one with the eyes has to do with hypnotism. I was going for an effect that would implicate the audience again, I guess it’s my interest in psychology rather than have them walk out of the room for a drink when the vampire turns to hypnotize someone. Those are generally very boring, predicable scenes.

“I studied what I had been exposed to as a film student and moviegoer, from the old Universals all the way up to the Hammer Films. No matter how you try to explain those away or make allowances, it’s always just Chris Lee with those damned bloodshot eyes. I knew our hypnotism would have to be something that is not easy for an audience to comprehend. Well, we’ve all had bloodshot eyes. So what we came up with was a kind of contact lens that just glows and glows and follows you, and is obviously not an optical done in the lab, and is therefore strange and fascinating to look at. The result is that it makes you look in his eyes, too, and you just wonder and look and look and look.”

And the levitation scene, in which the vampires float through the window to prospective victims?

“Well, I’m sorry they told you so much about that. Damn! That’s the kind of thing that should also make you guess, no you’re riveted to your seat. It’s one of those devices that ought to be revealed after you’ve seen the picture. But since they’ve told you. “The business of bringing the kid into the room on a boom crane eliminates the use of wires, and if you keep the camera in a certain position, keep the kid moving so you’re distracted from guessing or trying to guess how the effect was done, which is unlikely anyway and you cut properly, it’s very disturbing. It’s just obvious there are no wires. I also had an ectoplasmic mist surrounding him, and issuing in a kind of vacuum from him to his victim and back again.” The levitation effect was also enriched by shooting in reverse, which made the ectoplasmic fog swirl in an eerie way.

Jack Young – The Vampire Look

“We wanted something like the Nosferatu Of Murnau’s 1922 film where the vampire was walking death, ugliness incarnate, a skull that moved and was alive. “

– producer Richard Kubritz

‘Creating the image Of the vampire was a little like a fishing expedition, ” admits makeup man Jack Young, who in his 30 years as a makeup artist has worked on films from The Wizard of Oz to Apocalypse NOW changed the at least six time,” he says displaying a small card with Polaroid shots of each of the six renditions in his lab on the Warner lot. “We tried him with light pink on his face but he looked phony, burlesque. We finally came up with the light gray which is dead and bloodless. “Reggie Nalder (who plays Barlow) has such a wonderful face; he always plays some pretty grim so We just put ears on him, made him bald, put gray horrible makeup on him and used his own lips. For the teeth I made impressions of his, created a false set and then aged them by airbrushing shadows on them. They yellow and like they have cavities.” The eerie look of the vampire Barlow’s eyes are created by contact lenses almost like half a ping-pong ball—light green in color with red veins—that fit over the eye and can only be worn for 15 minutes at a time. The pupils reflect as do the eyes of the other vampire characters in the film, an effect created by yellow screen-like contact lenses. “They spark when the light hits them,” says Young with a devious look in his eye. “It looks awful, like they have searchlights coming out Of their eyes.”

In the scene near the end of the movie when Mears is driving the stake through Barlow’s heart, Barlow’s claw-like hand flies up and grabs Ben’s wrist. “For the claws, ” says Young, “I made a composite you can form with your hands. Ifs like a clay you can hake but it has flex. It wasn’t originally made for nails but that’s what I used it for. It’s all part of the attempt to get away from the stereotype Dracula. ”

As Ben continues to drive the stake in, Barlow’s head starts to rise from the coffin to meet Ben’s. Then suddenly the flesh seems to fall from the head, revealing a ghost-like skull. “I had to make the head about four or five times to get it to come out right, ” admits Young. The final one is hand-carved out of plaster then covered with a composition of wax that would sag , not drip. “I got the skin to appear to fall away by turning a heat gun on the completed portrait head,” adds Young.

But how will all of this look on a big screen? With everyone involved with the production stressing that SALEM’S LOT is a feature, not just a television special, it seems a logical question.

“This piece was not made with a lot of concessions to TV, beyond the obvious limiting of the use of violence,” Hooper replies. “There has been some second unit shooting, about five days I think, for some of the special effects. These are physical effects, as you called them before, not opticals there are no cheap opticals designed for the TV screen. The photography is very good, Mort Rabinowitz’s art direction is just remarkable, SALEM’S LOT will look like a feature.”

SALEM’S LOT wrapped shooting on August 29. Hooper assembled his rough cut within a couple of weeks after. CBS has already begun to promote the miniseries, and will air it on too successive nights during either the November ratings “sweep” (when network ratings are closely monitored to determine future advertising rates and the best specials are consequently televised) or a date soon after.

And way up in Center Lovell, Maine, the author of SALEM’S LOT is awaiting the production’s telecast like the rest of us.

“I thought THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE was a great movie, and I like the screenplay they’ve come up with for this, so I’m looking forward to it,” says Stephen King.

“What I’d really like them to do is send me a videotape of the European version. I’d be very into that.”

– Bill Kelley Cinefantastique – Volume 9, Number 2 (Winter 1979)

From “On the Set of ‘SALEM’S LOT By SUSAN CASEY” (FANGORIA Issue 4)

(Available at Amazon) Salem’s Lot 1979 Blu-ray

SALEM’S LOT (1979) RETROSPECTIVE – Filming Horror for Television (Part 1) Development The man producer Richard Kobritz called upon to get him his vampire in SALEM'S LOT is Tobe Hooper, the director of THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE and the last person one might expect to find directing a glossy production for a major studio much less one intended as a television miniseries.

1 note

·

View note

Text

SOCA THERAPY - JUNE 23, 2024

Soca Therapy Playlist

Sunday June 23rd 2024

Making You Wine From 6-9p on Flow 98.7fm Toronto

Carnival Jumbie (Dr. Jay Plate) - Problem Child

Soca Therapy - Lil Rick x King Bubba

Dose - Nicki Pierre x Fryktion

Whipped - Jamesy P x Fryktion

Rell Mash Up - King James x Fryktion

Safe Space - Rae x Fryktion

Starta Pack - Tionne Hernandez

Pampalam - Faith Callender

Road Friends - Nessa Preppy x Skinny Fabulous

Magnificent - Sackie

Fully Bad - Skinny Fabulous

Carnival Contract - Bunji Garlin

Good Medicine - Jaiga

Inventor (Izaman) - Olatunji

Jouvert Morning - J Fiyre

In The Center (BD Did It) - GBM Nutron x Farmer Nappy

Everytime - Nadia Batson

Life After Fete - Kerwin Du Bois

Soca Therapy - Patrice Roberts

Outside Nice - Kernal Roberts

Can't Take My Joy - Terri Lyons x DJ Private Ryan

New Day - Kerwin Du Bois x Teddyson John

Human - Machel Montano

Mon Bon Ami - Angela Hunte

Family - Destra

Where I Am - Freetown Collective

Welcome To Spice Mas - V'ghn

Tombstone - Mandella Linkz

Greater - Dash

TOP 7 COUNTDOWN - Powered By The Soca Source

From Apple Music's Top 100 Chart In Grenada

7. Horny (Riddim X) - Muddy

6. Addicted - Jab King x Travis World

5. Runaway - Mical Teja

4. Tack Back - Kes x Tano

3. Slip In - Geo

2. Pray - Voice

1. DNA - Mical Teja

Night & Day - Th3rd x JMTB

Magic - Kes x Jimmy October x Etienne Charles

Build Ah Fence - Patrice Roberts x Busy Signal

Rock So - Blaxx

Going Under - Adam O

Just Dance - Machel Montano x Problem Child

Juantana Mera - Burning Flames

Talk - Barbados Troubadours

Aye Aye Aye - Square One

Oil Pumping - Krosfyah

For All Of Those - Statement

Rock Yuh Body - Denise Belfon x Ghetto Flex

Soca Daddy - Ghetto Flex

All Star Show - Ghetto Flex x KMC x Bunji Garlin x Ataklan

PAN MOMENTS

Ribbon In The Sky - Ken Professor Philmore

TANTY TUNE

(1991) - Golo - Second Imij

Wine And Bend Over - Ghetto Flex x Denise Belfon

Best Jam Ever - Patrice Roberts

Sample - Problem Child

Bare Good Vibes - Shal Marshall

Mind Off (DM Edit Clean) - Lil Rick x Jus-Jay

Not Alone - Skinny Fabulous x Leadpipe x Jus Jay King

Runway - Jagwa de Champ x Jus Jay King

Clock Een - Pumpa x Jus Jay King

Out & Bad - Voice

How Ah Living - Farmer Nappy

Rental - Farmer Nappy

Collateral - Shaquille

Savannah Grass - Kes The Band

Memory - Machel Montano x Tarrus Riley

Hulk - Blaxx

Thief A Wine - Kirton aka Alma Boy

Thiefin - Machel Montano

Jook In The Party - Gillo

Dr. Cassandra - Gabby

Carnival Is Bacchanal - Ghetto Flex x Rocky

Splash - Jany

Stranger - The Mighty Shadow

NORTHERN PRESCRIPTION

Whinin' Alone (Remix) - Juswata x Sticky Wow

My All - Nadia Batson

Round & Rosie - Nailah Blackman

Follow Dr. Jay @socaprince and @socatherapy

“Like” Dr. Jay on http://facebook.com/DrJayOnline

0 notes

Text

SOCA THERAPY - JUNE 16, 2024

Soca Therapy Playlist

Sunday June 16th 2024

Making You Wine From 6-9pm on Flow 98.7fm Toronto

Pump Me Up (Dr. Jay Plate) - Edwin Yearwood

Carry On - Patrice Roberts

Feel It - Problem Child

Play Harder - Machel Montano

Forget About It - Kerwin Du Bois

DAP (Drink And Party) - Viking Ding Dong

Night & Day - Th3rd x JMTB

Vent (Jester VIP Edit) - Teddyson John

Live Yuh Life - College Boy Jesse x Dj Private Ryan

Keep Talking - Turner x Dj Private Ryan

Keep Jammin On - Kes x Dj Private Ryan

Whole Day - Rae x Dj Private Ryan

Jouvert Morning - J Fiyre

Buss Head - Machel Montano x Bunji Garlin

Talk Yuh Talk - 3 Canal

J'ouvert Morning - Flava

In The Center (Innocent Crew Break Down Mash Up Ultra Simmo) - GBM Nutron x Farmer Nappy

In The Center - GBM Nutron x Farmer Nappy

Inventor (Izaman) - Olatunji

Let's Pretend - Patrice Roberts

Ah Love It Here - Ricardo Drue

Good Medicine - Jaiga

Stress Bout Dat - Adam O

Soca Therapy - Lil Rick x King Bubba

Sound Check - Mad Skull x Wetty Beatz

TOP 7 COUNTDOWN - Powered By The Soca Source

Most Streamed in St. Vincent & The Grenadines on Apple Music (All Genres Saturday June 15th)

7. Slip In (Clean) - Geo

6. Blessed - Kennie Montana

5. Like Never Before - Problem Child

4. Next # In Line (Clean) - Added Rankin

3. BOTS (Battle Of The Sexes) - Problem Child

2. Start - Dat-C DQ x Skinny Fabulous

1. Carnival Jumbie - Problem Child

Cyah Contain - Tian Winter

Whistle While You Work - Triple Kay

Stagga Dance - Lil Natty & Thunda x Muddy - Stagga Dance

Out The Way (Vincy Version) - Lyrikal

Weh Yuh From - Keith Currency

Doh Bother Meh - Problem Child x Lavaman

Fling It - Patrice Roberts

Whoop Waps - Skinny Fabulous x Jab King

Hard Fete - Bunji Garlin

Ah Doh Have - Temptress x Deno Outta Range Mason

The Ambush - Lyrikal x Lil Natty & Thunda

Miracle - Kes x Tano

Come Home - Nailah Blackman x Skinny Fabulous

Beatin Road - Preedy

Beatin' Road (Remix) - Preedy x Patrice Roberts

Rell Mash Up - King James x Fryktion

Whipped - Jamesy P x Fryktion

Dose - Nicki Pierre x Fryktion

Safe Space - Rae x Fryktion

Play Mas - Teddyson John x Lyrikal

PAN MOMENTS

Rebecca - WITCO Desperadoes

TANTY TUNE

(1980) Disco Daddy - Nelson

Birthday Song - Nailah Blackman x Ding Dong

Dutty Flex - Kes

Bad Gyal - Erphaan Alves

Runaway - Mical Teja

Curry Tabanca - De Mighty Trini

Formula - Kes

BYE x2 - Saddis x Jus Jay King

Life After Fete - Kerwin Du Bois

Everytime - Nadia Batson

Penthouse (D Ninja Edit) - Voice

Penthouse (Dr. Jay Plate) - Voice

Zoom Zoom - Full Blown

Embrace - Mical Teja

Fun Police - Viking Ding Dong

Night Shift - Machel Montano

Slow Wine - Patrice Roberts

NORTHERN PRESCRIPTION

Always - Miguel Maestre x Skorch Bun It x Dr. Jay De Soca Prince

Speechless - Kerwin Du Bois x Lyrikal x Voice x Teddyson John

Big Bad Soca - Bunji Garlin

Follow Dr. Jay @socaprince and @socatherapy

“Like” Dr. Jay on http://facebook.com/DrJayOnline

0 notes