#south american native ungulates

Text

Neolicaphrium recens here might look like some sort of early horse, but this little mammal was actually something else entirely.

Known from southern South America during the late Pleistocene to early Holocene, between about 1 million and 11,000 years ago, Neolicaphrium was the last known member of the proterotheriids, a group of South American native ungulates that were only very distantly related to horses, tapirs, and rhinos. Instead these animals evolved their remarkably horse-like body plan completely independently, adapting for high-speed running with a single weight-bearing hoof on each foot.

Neolicaphrium was a mid-sized proterotheriid, standing around 45cm tall at the shoulder (~1'6"), and unlike some of its more specialized relatives it still had two small vestigial toes on each foot along with its main hoof. Tooth microwear studies suggest it had a browsing diet, mainly feeding on soft leaves, stems, and buds in its savannah woodland habitat.

It was one of the few South American native ungulates to survive through the Great American Biotic Interchange, when the formation of the Isthmus of Panama allowed North and South American animals to disperse into each other's native ranges. While many of its relatives had already gone extinct in the wake of the massive ecological changes this caused, Neolicaphrium seems to have been enough of a generalist to hold on, living alongside a fairly modern-looking selection of northern immigrant mammals such as deer, peccaries, tapirs, foxes, jaguars… and also actual horses.

Some of the earliest human inhabitants of South America would have seen Neolicaphirum alive before its extinction. We don't know whether they had any direct impact on its disappearance – but since the horses it lived alongside were hunted by humans and also went extinct, it's possible that a combination of shifting climate and hunting pressure pushed the last of the little not-horses over the edge, too.

———

NixIllustration.com | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#neolicaphrium#proterotheriidae#litopterna#meridiungulata#south american native ungulates#panperissodactyla#ungulate#mammal#art#convergent evolution#not-horse#a phony pony#quaternary extinction

482 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh look who finally finished the National Fossils map for South America.

By popular vote Argentinosaurus, Prionosuchus and Perucetus have been selected for their countries. And since you guys decided on giant dinosaur, giant amphibian and giant whale respectively, I thought I‘d stick with the theme. So I picked a giant croc, giant snake, giant bird, and giant rodent.

Then there is Macrauchenia, because I wanted to include some of South America‘s native ungulates, a group of mammals that was endemic to the continent and is now completely extinct. Also they just look like big llamas to me which feels very South American. I was considering some sloths or glyptodons but I already included some of those for Central America and I didn‘t want to repeat them.

Smilodon because it seems too iconic of a creature to not be featured anywhere.

And last but not least: Lovely, stupid-looking, early jawless fish Sacabambaspis.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

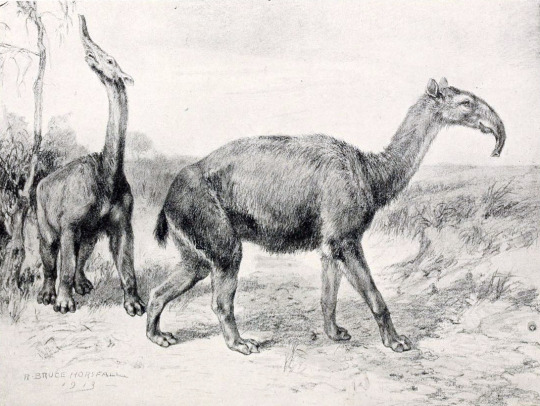

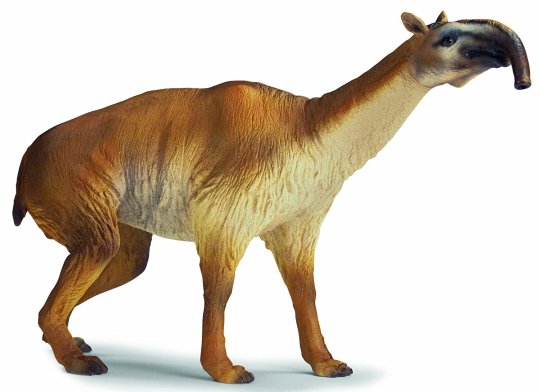

Macrauchenia

(temporal range: 7-0.01 mio. years ago)

[text from the Wikipedia article, see also link above]

Macrauchenia ("long llama", based on the now-invalid llama genus, Auchenia, from Greek "big neck") was a large, long-necked and long-limbed, three-toed native South American ungulate in the order Litopterna.[1] The genus gives its name to its family, the Macraucheniidae or "robust litopterns". Like other litopterns, it is most closely related to the odd-toed ungulates (Perissodactyla), from which litopterns diverged approximately 66 million years ago. The oldest fossils in the genus date to the late Miocene, around seven million years ago, and M. patachonica disappears from the fossil record during the late Pleistocene, around 20,000-10,000 years ago. M. patachonica is one of the last and best known member of the family and is known primarily from the Luján Formation in Argentina, but is known from localities across southern South America. Another genus of macraucheniid Xenorhinotherium was present in northeast Brazil and Venezuela during the Late Pleistocene. The type specimen was discovered by Charles Darwin during the voyage of the Beagle. In life, Macrauchenia may have resembled a humpless camel, though the two taxa are not closely related.[2] It fed on plants in a variety of environments across what is now South America. Among the species described, M. patachonica and M. ullomensis are considered valid; M. boliviensis is considered a nomen dubium; and M. antiqua (or M. antiquus) has been moved to the genus Promacrauchenia.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ungulates of iNaturalist

Welcome! This blog is dedicated to sharing, in a picture(s)-of-the-day type format, the amazing and beautiful mammals broadly grouped as “ungulates” observed around the world via the citizen science platform iNaturalist.

About Ungulates

Ungulates, or hoofed mammals, are members of a few different taxonomic groups, principally the orders Artiodactyla (even-toed ungulates) and Perissodactyla (odd-toed ungulates) in modern times. How these major two groups are related to each other is not entirely settled: historically they have been classified together in a larger group Ungulata (an arrangement which has been revived by some recent phylogenetic research as the “Euungulata Hypothesis”), while other phylogenies find them to be not-especially-close relatives in a group that also includes bats, pangolins, and carnivorans. One notable change to the relationships of the classic ungulate orders is the revelation that the old “order” Cetacea (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) is deeply nested within Artiodactyla, thus is included as part of the remit of this blog.

Several extinct lineages could also be considered ungulates, perhaps most notably the numerous lineages of “South American native ungulates” that lived almost exclusively on South America from about 66 million until about 12,000 years ago; their relationships to other mammals, and to each other, remain contentious. There is also another living mammal group, Paenungulata, that is included in this blog. In modern times, Paenungulata consists of hyraxes, sirenians (manatees and the dugong), and elephants. These strange animals have historically been difficult to place in the mammals’ evolutionary tree, though up through the late 20th century, hyraxes were often allied with perissodactyls. Thus, despite the fact they are not exactly “typical” ungulates especially in a modern parlance, in reflection of historical hypotheses in which they have been united with artiodactyl and perissodactyl groups and some general similarities to these other ungulates, paenungulates are also featured as part of this blog.

About the Blog (and me)

All images featured on this blog are in the public domain or under a Creative Commons license, which will be linked to in each post. The original iNaturalist observation will also be credited and linked. At present, my plan is that all images will be reasonably clear, reasonably hi-res, featuring a live ungulate (though I may eventually start adding good photos of bones), without any watermarks etc. on the image (though, again, I may eventually break down and start making an exception for trail cam images).

The taxonomy used on the blog is not derived from any one source, and does not always follow the rather overlumped and sometimes-slow-to-change iNaturalist taxonomy. I am a taxonomic splitter, so often recognize subspecies as full species, or populations as subspecies, when there is reasonable behavioral, biogeographical, morphological, and/or especially genetic basis for doing so and some precedent for it in the literature. Since this is blog is dedicated to showcasing the beauty and diversity of the world’s ungulates and is not meant to be a taxonomic treatise on them, I don’t expect the taxonomy I employ here to be thought of as the “right” one, but I do base my splits (and my rarer lumps) on proposals in the scientific literature that I feel to be reasonably sound.

I may eventually write more about taxonomy, and about identifying ungulates and their natural history, as things progress here, but again, this is meant to be a blog full of pretty pictures. I will keep this blog queued up with a few pictures a day, so there’ll be plenty of content in a steady stream even if I’m not around to manage things actively.

For a bit about me, I am a vertebrate palaeontologist with a research focus on proboscideans, especially mastodons. Though my heart belongs to megafauna, I have an avid interest in natural history in general and my professional background is in museum collections management. Though I am a keen user of iNaturalist (IDing other people’s beautiful observations more so than uploading my own more-modest ones), I want to emphasize here that this blog is in no way affiliated with iNaturalist, it is just my personal endeavor to show off some cool creatures in line with the Creative Commons licensing on the images.

I hope you’ll join in on this journey through the world’s ungulates, and enjoy the beauty of these diverse and fascinating animals!

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

COUGAR The cougar is a large cat native to the Americas. Its range spans from the Canadian Yukon to the southern Andes in South America and is the most widespread of any large wild terrestrial mammal in the Western Hemisphere. https://bcfirearmsacademy.ca/cougar/ BOOK YOUR CORE EXAM HERE The head of the cougar is round and the ears are erect. Its powerful forequarters, neck, and jaw serve to grasp and hold large prey. It has four retractile claws on its hind paws and five on its forepaws, of which one is a dewclaw. The larger front feet and claws are adaptations for clutching prey BOOK YOUR CORE EXAM HERE The cougar is an ambush predator that pursues a wide variety of prey. Primary food sources are ungulates, particularly deer, but it also hunts smaller prey such as rodents. It prefers habitats with dense underbrush and rocky areas for stalking but also lives in open areas. Cougars are territorial and live at low population densities. Individual home ranges depend on terrain, vegetation and abundance of prey. While large, it is not always the apex predator in its range, yielding prey it has killed to American black bears, grizzly bears and packs of wolves. It is reclusive and mostly avoids people. Fatal attacks on humans are rare but increased in North America as more people entered cougar habitats and built farms. (at BC Firearms Academy - Surrey) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cmaj5rarAd6/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Note

For the ask (I guess this is not anonymous, but w/e), who is an obscure figure in your field you're legit upset not more people know about and what did they research?

I have a bit of a soft spot for Frederic Brewster Loomis, Amherst College Class of 1896 and professor in biology, comparative anatomy, and geology there from 1904-1937. Obviously a lot of my affection for the guy comes from having spent my undergrad years as a geology student at Amherst, working in a museum that owes a lot to Loomis’s prolific field collection, and even after I graduated from Amherst I wasn’t through; my master’s thesis was based around the mastodon skeleton at Amherst which Loomis saw mounted in 1918 and my title was a direct sequel to his original short paper on the Amherst mastodons. So I guess I’ve a bit of a personal connection that’s biasing me, but still…

Fred Loomis did his work in an interesting, important period in American palaeontology. He was getting started post-Bone Wars once the dust had had a decade or two to settle and as the Second Great Dinosaur Rush ran its course and contributed to an emerging understanding of the palaeontological history of North America that could only come with more fossils. Almost every summer, Loomis would take a couple of Amherst students bumping across the prairies and badlands of the western interior, collecting fossils — mostly Cenozoic mammals — from across time and space including from localities that did or would eventually have big-name recognition in mammal palaeontology: Pawnee Buttes, Agate, Melbourne. He made an eight-month expedition to Patagonia in 1911-1912 that resulted in one the largest North American collections of Cenozoic fossils from Patagonia, including what remains the only complete skull of the bizarre South American native ungulate Pyrotherium. His work at Melbourne, Florida, led to the collection of heaps of Pleistocene mammals including a giant Columbian mammoth, Amherst’s official mascot since 2016. He found just about every type of North American mammal you care to name including every one on this wall (and ESPECIALLY including oreodons), mosasaurs, tortoises, sauropods, alligators… Several of his finds were holotypes of new species, he had a shovel tusker named after him by Erwin Hinckley Barbour (who continued the proud tradition of getting Amherst geologists’ middle initials wrong in print)…. and nobody seems to remember him much these days. Osborn, Simpson, Barbour, Matthew, Frick, Sternberg(s), Andrews, Gidley… these are the names you’d get if you asked for prominent American palaeontologists of the early-mid 20th century, not Loomis, despite the wealth of collecting he did, roughing it in the field for months with students along for the ride. Amherst College has the third-largest palaeontological collection in New England in no small part because of Loomis’s efforts in the field.

In the grand scheme of things, no, Loomis wasn’t an Osborn or a Simpson in terms of scientific stature. He wasn’t the director of the AMNH and he wasn’t even a full-time researcher, what with teaching classes and such. George Gaylord Simpson, whose real day in the sun came a bit after Loomis’s death, didn’t much care for him and was dismissive of his skill and accomplishments. Even Loomis’s papers are tricky to find online (though his popular book Hunting Extinct Animals In the Patagonian Pampas isn’t!), and regrettably if Amherst’s archives have digitized much of his materials I haven’t found where. But… I don’t know, I like the guy. He was an instructor at a tiny New England liberal arts college who was in correspondence with lots of the big names of the field in his day; organizing expeditions between the AMNH, the Smithsonian, and… wee little Amherst College; giving students the opportunity for adventure and practical scientific experience at once… the guy was by all accounts outgoing and personable, and he was a bit of a cowboy in the last window where you could really be that — he started one of his papers lamenting that camping in the Fort Pierre around Mule Creek, Wyoming, was a “dubious pleasure” — but he was operating in what was, really, a frontier and often did careful, thoughtful work by the standards of palaeontology at the time. I suspect Simpson had a low opinion of Loomis’s work because a lot of it turned out to be incorrect or incomplete, but that work being done set the standards for what was to come. Often, Loomis and his students didn’t even know where they were out in the field; they were blazing new trails into the continent’s ancient past.

My undergrad sort-of-advisor, the great Margery Coombs, once said something to the tune of “Loomis earned a place of honor in vertebrate palaeontology. It might not be a huge place, but it is there.” He was someone who clearly loved the work and did what he could to advance it at an important period in its history, and my own career, such as it is, really owes a huge debt to his efforts. I just kinda wish Loomis was a name that came up more in people’s minds as they reflect on that phase of early-mid 1900s American palaeontology where a lot of the important groundwork for our current understanding was laid.

(For the record, me having a personal and professional soft spot for a scientist who lived a century ago does NOT mean I necessarily endorse all his actions or views, etc. For example, a whole lot of Loomis’s collecting took place on traditional Indigenous homelands that were taken by US Congressional acts ~30-50 years prior, and sometimes included the collection of cultural artifacts as well as fossils, and I highly doubt this was a fact that would’ve even registered as an issue for him — though of course I could be wrong. I guess it’s a matter of finding him interesting, and seeing and appreciating what work he did that was good or sparks curiosity, while the context in which that work was done might not be so good or inspiring. But that’s interacting with history at all, isn’t it?)

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Horse evolution

Fifty five million years ago during the Eocene epoch period, the Eohippus, a fast, small half meter tall with padded ties with hoofs, exists in the Paleocene Eocene Thermomaximum (Damp rainforests in North America).

Perissodactyls - hoofed mammal w/ an odd number of toes/odd toed ungulate

• Rhinos

• Tapirs

• Horses

Hyracotherium was the first perissodactyl that is know to man.

⁃ Fossils discovered in England

⁃ Small ungulate

⁃ Named after the resemblance to the rock hyrax

Full Eohippus fossil was discovered by O.C. Marsh in 1876.

⁃ Size of a dog

⁃ About 35 cm tall at the shoulder

⁃ Short crowned teeth

⁃ 4 front toes 3 back toes capped with hoofs

Equus

⁃ Modern day horse

⁃ Part of Equidae

When climate became dryer and cooler, dry grasslands appeared in North America.

Mesohippus and Misohippus

⁃ Roamed at same time during the Oligocene Epoch e33.9 to 23 MYA

⁃ Adapted to the climate change

⁃ Mesohippus was about 23 KG

⁃ Misohippus was about 46 KG

⁃ Both lost their 4th front toe and middle toe grew

⁃ Mesohippus disappeared at end of Oligocene epoch

Parahippus

⁃ Misohippus ancestor adapted to large plains

⁃ Parahippus leonensis was even better adapted (first true hypsodont)

Merychippus

⁃ Descendants of Parahippus

⁃ First true equine (subfamily of equid)

⁃ Taller

⁃ Stood on tip toes

⁃ Could grow to be 450 KG

Monodactyls

• Stand on one toe

• Reduces stress on legs

Equus

⁃ Pliocene Epoch

⁃ Modern horse genus

⁃ Dinohippus is the most closely related to modern horses

⁃ Oldest equus is equus simplicidens

Great American Biotic Interchange

⁃ Equus Simplicidens migrated to South America and over the Bering land bridge to Russia.

Most large animals in North America went extinct in the Pleistocene epoch which went from 2.5 million to 11,700 years ago.

1. Caused by ice age

2. Populations of bison were competition

3. Humans began hunting horses

4. Horses that migrated survived

Botai Culture of ancient Kazakhstan began using horses 6,000 years ago.

Humans bred horses and brought them back to America.

Horses fled and became feral around 1550 and wild horses became a thing in NA again. Natives used them for transport.

Wrote some notes on the evolution of horses because I was bored.... 🐴

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The barred owl (Strix varia), also known as northern barred owl or hoot owl, is a true owl native to eastern North America. Adults are large, and are brown to grey with barring on the chest. Barred owls have expanded their range to the west coast of the United States and Canada, where they are considered invasive. Mature forests are their preferred habitat, but they are also found in open woodland areas. Their diet consists mainly of small mammals, but they are also known to prey upon other small animals such as birds, reptiles, and amphibians.

The adult is 16–25 inches long with a 38–49 inch wingspan. Weight in this species is 500 to 1,050 g (1.10 to 2.31 lb). It has a pale face with dark rings around the eyes, a yellow beak and brown eyes. It is the only true owl of the eastern United States which has brown eyes; all others have yellow eyes. The upper parts are mottled gray-brown. The underparts are light with markings; the chest is barred horizontally while the belly is streaked vertically (hence its name "barred owl"). The legs and feet are covered in feathers up to the talons. The head is round and lacks ear tufts.

The historical lack of trees in the Great Plains acted as a barrier to the range expansion and recent increases in forests broke down this barrier. Increases in forest distribution along the Missouri River and its tributaries provided barred owls with sufficient foraging habitat, protection from the weather, and concealment from avian predators to allow barred owls to move westward. Decades later, increases in forests in the northern Great Plains allowed them to connect their eastern and western distributions across southern Canada. These increases in forests were caused by European-American settlers via their exclusion of fires historically set by Native Americans, by their suppression of accidental fires and by increased tree-planting; to a lesser degree this regional net forest increase was also caused by these settlers' overhunting bison and elk and, in some areas, by extirpating beaver and replacing native ungulates with livestock.

Breeding habitats are dense woods across Canada, the United States, and south to Mexico. The barred owl is particularly numerous in a variety of wooded habitats in the southeastern United States. Recent studies show suburban neighborhoods can be ideal habitat for barred owls. Using transmitters, scientists found that some regional populations increased faster in the suburban settings than in old growth forest. A factor of this suburban success may be easily accessible rodent prey in such settings. However, for breeding and roosting needs, this species needs at least some large trees and can be locally absent in some urban areas for this reason. On the other hand, studies from the Northeastern United States, such as in New Jersey, found barred owls breeding mainly in plots of old-growth woodlands, and rarely successfully breeding in peri-urban areas, in part because of competitive and predatory displacement by great horned owls.

The barred owl's nest is often in a tree cavity, often ones created by pileated woodpeckers; it may also take over an old nesting site made previously by a red-shouldered hawk, Cooper's hawk, crow, or squirrel. It is a permanent resident, but may wander after the nesting season. If a nest site has proved suitable in the past they will often reuse it as the birds are non-migratory. In the United States, eggs are laid from early-January in southern Florida to mid-April in northern Maine, and consist of 2 to 4 eggs per clutch. Eggs are brooded by the female with hatching taking place approximately 4 weeks later. Young owls fledge four to five weeks after hatching. These owls have few predators, but young, unwary owls may be taken by cats. The most significant predator of barred owls is the great horned owl. The barred owl has been known to live up to 24 years in the wild and 23 years in captivity.

The barred owl hunts by waiting on a high perch at night, or flying through the woods and swooping down on prey. A barred owl can sometimes be seen hunting before dark. This typically occurs during the nesting season or on dark and cloudy days. Daytime activity is often most prevalent when barred owls are raising chicks. However, this species still generally hunts near dawn or dusk. The barred owl is a generalist predator. Prey is usually devoured on the spot. Larger prey is carried to a feeding perch and torn apart before eating. Barred owls have been known to be attracted to campfires and lights where they forage for large insects.

The usual call is a series of eight accented hoots ending in oo-aw, with a downward pitch at the end. The most common mnemonic device for remembering the call is "Who cooks for you, who cooks for you all." It is noisy in most seasons. When agitated, this species will make a buzzy, rasping hiss and click its beak together forcefully. While calls are most common at night, the birds do call during the day as well.

226 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hunting Coyotes at Night Tips

youtube

INTRODUCTION

The coyote, whose name comes from the Nahuatl (Aztec language) word coyote, belongs to the family of canines, including dogs, wolves, jackals, foxes, wild dogs.

Canids are believed to be native to North America's great plains where, 40 to 50 million years ago, in the Eocene, their common ancestor lived. Very quickly, the fox branch, Vulpes, broke away from this common trunk. A little later, in the Pliocene, the other components of canines are differentiated, notably wolves and coyotes, which, despite their close kinship, evolve separately. At the end of this period, about 2.5 million years ago, Canis esophagus appears, the ancestor of the coyotes, which must have been a little larger than the present species' animals. According to more recent Pleistocene fossils found in the United States in Maryland and the Cita Cañon in Texas, his descendants closely resemble him. They then rub shoulders with the saber-toothed tiger on the American continent, which still roams the plains.

Since this distant time, coyotes have changed little in their morphology and have slightly differentiated from their ancestors. However, the comparative study of the skulls shows that their cranium has developed, but that the frontal bone is narrower in modern animals than it was in their ancestors. Their non-specialization over the ages has allowed coyotes to colonize new spaces and to adapt to all kinds of habitats and new situations. Thus, they are hunters, but they can survive by feeding on carrion, insects, or fruit. By ridding wild herds of weaker animals and eliminating already doomed individuals, they play their part in the natural balance.

Originally probably inhabiting the Great Plains, the southwestern United States, and Mexico, coyotes have greatly expanded their habitat, which, although uniquely American, also includes deserts, mountains, and forests. And the outskirts of large cities. Thanks to man, who changed the environment and hunted wolves until their almost total extinction, their current territory is immense because they have taken over the vast areas formerly occupied.

THE LIFE OF THE COYOTE

A SILENT AND INTELLIGENT HUNT

The coyote is a solitary hunter that feeds on anything it can catch. In the central plains, where the climatic conditions are relatively stable, it has the same essential diet all year round, made up for more than 75% of hares. Rabbits, mice, pheasants are also among his favorite prey. Occasionally it does not disdain muskrats, raccoons, polecats, opossums, and beavers, as well as snakes and large insects.

In late summer and fall, the coyote will eat fruit that has fallen to the ground. Blackberries, blueberries, pears, apples, peanuts then represent 50% of his diet. He knows how to choose a fully ripe watermelon and cut it in half to taste its juicy pulp. Neither does he disdain the soybean meal or cottonseed meal distributed to cattle.

In more arid environments, such as Mexico, the coyote mainly hunts small rodents. It also attacks marmots and ground squirrels in Canada, ground squirrels that look like large guinea pigs. But these two species hibernate, and in winter, in these northern regions, it is forced, to survive, to become a scavenger.

In suburban or urban areas, the coyote feeds on human waste, products manufactured by him, such as dog food, or even his pets.

ALONE OR IN COOPERATION

When it hears prey or spots it from afar thanks to its keen eyesight, the coyote approaches it silently, facing the wind, tail low, with slow steps interspersed with pauses. Arrived at 2 meters from his victim, he leaps on her and bites her neck. To finish her off, he keeps her in his mouth and shakes her violently. Death is quick. It usually devours the animal on the spot, even eating the bones of small prey.

When coyotes live together, they choose larger prey such as deer, elk, and other ungulates. They run around the herd. In a panic, an individual is isolated, then surrounded and attacked.

When the coyotes hunt in pairs, they force the isolated to run in a circle, taking turns to tire them out. This technique is used with caribou. The killed prey is disemboweled with claws and teeth and divided.

TWILIGHT AND MORNING HUNTERS

Twilight and morning hunters

Essentially nocturnal, the adults move around a lot, hunting more readily at dawn or dusk. On the other hand, young people between 4 months and a year old move more during the day and less at night. Their often unsuccessful hunting attempts force them to devote a lot of time to it, but they still have no territory or offspring to watch over.

SCAVENGER TO SURVIVE IN WINTER

In Alaska and in several Canadian provinces, where they arrived following the gold miners in the mid-nineteenth th century, coyotes have learned to face the bitter cold of winter. In these regions, animals must live and feed when the temperature is -10 ° C. The thick fur of the Far North's coyotes covers their whole body and has the same insulating power as that of the gray wolf. The guard hairs reach 11 cm long compared to 5 cm in animals living in a warmer climate. Thick and tight, the undercoat can measure 5 cm in thickness.

But the coyote does not run well in thick snow. However, hares and rabbits do not come out of their burrows when the outside temperature is too low, and groundhogs hibernate. The coyote would not survive the winter if it did not fall back on dead animals. Feeding on all the carrion he finds, he shares them with his fellows.

However, if the wolves arrive, he must give way. He sometimes buries or hides to return to them later. Its best ally is the cold, which finishes off sick or weakened animals, often at the tail of herds of large herbivores. Thus, in winter, it therefore, moves after the latter, devouring dead ungulates. Watching for the slightest failure, he does not hesitate to give the "coup de grace" to elk or caribou, exhausted and unable to defend themselves. If the snow is not too thick and the carrion is insufficient, the coyotes will join forces to attack.

OFTEN SOLITARY, THE COYOTE PREFERS TO LIVE AS A COUPLE

Halfway between the fox, solitary, and the wolf, which lives in organized packs, the coyote is a relatively pleasant animal. The male-female pair is the basic unit of this society, where one also meets many solitary animals and herds.

The couple is formed in the middle of winter, at the beginning of the mating season, and sometimes remain united for several years, sharing den and territory.

HIERARCHICAL FAMILY GROUPS

In areas where the density of coyotes is relatively low, some animals live solitary. Usually, they are the ones who howl at nightfall from the top of the steep rocks.

In regions where coyotes are numerous and food abundant, small groups are formed, comprising 5 or 6 individuals, that is to say, the parents accompanied by the young of the previous year. These family groups are hierarchical, with the oldest animals dominating and leading the rest of the herd. This type of association also appears when small rodents become scarce. Only substantial cooperation then allows the coyotes to catch animals the size of an elk or a caribou, often faster than them.

Real clashes between coyotes are rare. Grunts and stern expressions are often enough for animals to give up the fight and submit. He must then leave the winner's territory or abandon him the carcass on which he is feasting.

Gambling is frequent. Fake fights, chases, and nibbling are expected in a family. This is part of the education of young people: parents teach them to communicate and to hunt.

THE CRY OF THE COYOTE

The repertoire of coyotes is immense: barks like a dog, howl like a wolf, barks like a small puppy, growls ... They use combinations of all these sounds to call the members of their group signal their presence or immediate danger. They also seem to enjoy listening to each other bark or howl in the dark. This is how the solitary animals gathering for a hunting party at nightfall bring about a discordant concert famous throughout the American West and audible for miles around.

A VARIABLE AREA

Each coyote, each couple or family group has its territory, centered on the lodge or den. The limits of this territory are marked by all the occupants, who mark it out very regularly by urinating. But few coyotes fight to deny the entry of their domain to a congener. The dominated animal is content to move away to seek asylum elsewhere. However, it seems that groups defend their territory more actively than pairs or solitary animals. Loud crashes, but not very violent, sometimes take place at the borders. The coyotes seem to recognize each other from a distance, up to 200 m. When two individuals meet, if they already know each other, they go their way.

The territory (from a few kilometers to over 50 km) depends on coyotes' density in the region, the season, and the abundance of prey. A study conducted in the Yukon Territory, in northwestern Canada, showed that the thickness of coyotes varies from 1 to 9 individuals per 100 km 2 in winter to 2.3 individuals per km 2 in summer. Instead of traveling at night - on average, a coyote crosses, during a night's hunt, 4 km - coyotes can make long journeys to find territory or for food.

BODY LANGUAGE

The whole body of the coyote is used to make itself understood. Rolling up the lips, lowering or raising the tail, flattening or raising the ears, making the hair stand up are all signals. The coat's black patches further reinforce the facial expressions: lips edged with white hairs around the ears' eyes and lips. A dominant coyote opens its eyes wide. An angry coyote flattens its ears. Aggression is indicated by the erect ears, the raised shoulders, the hair on the back bristling, the lips rolled up, the tail slightly raised. A submissive male shows his genitals to the opponent.

AT NINE MONTHS, THE YOUNG ARE ADULTS

The mating season lasts from January to March but begins earlier in the North than in the South. More than 90% of females at least 20 months old go into heat. About 60% of 10-month-old females wait until the end of February if weather conditions are favorable. If the winter is too harsh, they will wait another year to mate.

Males are attracted early on by the smell of hormones in the urine of females in heat. Their courtship is assiduous for several weeks because before fertilization (pre-estrus) lasts from 2 to 3 months. Often, several males are interested in the same female and follow her without a fight. At the time of estrus, which lasts ten days, the female chooses her future partner and comes to give him a few blows of the muzzle. Like other canids, coyotes can stay mated for more than 25 minutes. The other males present do not try to intervene and leave to try their luck with a still available female.

A DEVOTED FATHER

The couple demarcates a new territory, choose and clean an old badger, marmot, or fox burrow, or decide to dig a new den. During gestation, which lasts about two months (on average 63 days), both mates hunt together and sleep side by side. When the birth approaches, the male manages alone to ensure the daily pittance, and he brings food to his companion. This one arranges the burrow by depositing there leaves, grasses, or hairs torn from its belly. Some females give birth to their young on the bare ground.

A litter includes between 2 and 12 young (on average, 4). Both parents take care of them. Thus, the father helps with the toilet and feeding of the young after they have been weaned. He guards the entrance to the burrow. In case of danger, he transports the young people, one by one, to a safe refuge, sometimes several kilometers away.

For the first ten days, the little ones suck about every 2 hours. Their eyes open around the tenth day. The first teeth appear around the twelfth day. They walk around three weeks and then begin to come out of the den, watched by the parents, to explore their environment. They run before they are six weeks old. They are generally weaned at the age of 1 month but receive in relay regurgitated meat by both parents. They begin to prey on dead prey, mice, then rabbits.

Generally, young males emancipate themselves and leave their family group between 6 and 9 months. Young females tend to stay with their parents.

THE COYOTE'S DEN

When the coyote does not build an ancient badger or fox den to give birth to its litter, it digs one, very characteristic. The entrance, unique, 30 to 60 cm in diameter, is often hidden by bushes. About 3 m long and 40 to 50 cm wide, a tunnel connects it to a central room, or nursery, where the little ones will be installed. About 1.50 m in diameter, it is well ventilated, as the air enters it through a ventilation chim

TO KNOW EVERYTHING ABOUT THE COYOTE

LAROUSSE

Search the encyclopedia ...

Home > encyclopedia [wild-life] > coyote

coyote

Coyote

Coyote

Coyote

CoyoteCoyoteCoyote cry

Unlike the wolf, the North American coyote's numbers and its range are expanding, although they are trapped and poisoned by humans. It is one of the few wild animal species capable of surviving in urbanized regions. Its extraordinary ecological plasticity has enabled it to conquer two-thirds of the American continent.

INTRODUCTION

The coyote, whose name comes from the Nahuatl (Aztec language) word coyote, belongs to the family of canines, including dogs, wolves, jackals, foxes, wild dogs.

Canids are believed to be native to North America's great plains where, 40 to 50 million years ago, in the Eocene, their common ancestor lived. Very quickly, the fox branch, Vulpes, broke away from this common trunk. A little later, in the Pliocene, the other components of canines are differentiated, notably, wolves and coyotes, which evolve separately despite their close kinship. At the end of this period, about 2.5 million years ago, Canis esophagus appears, the ancestor of the coyotes, which must have been a little larger than the present species' animals. According to more recent Pleistocene fossils found in the United States in Maryland and the Cita Cañon in Texas, his descendants closely resemble him. They then rub shoulders with the saber-toothed tiger on the American continent, which still roams the plains.

Since this distant time, coyotes have changed little in their morphology and have slightly differentiated from their ancestors. However, the comparative study of the skulls shows that their cranium has developed, but that the frontal bone is narrower in modern animals than it was in their ancestors. Their non-specialization over the ages has allowed coyotes to colonize new spaces and to adapt to all kinds of habitats and new situations. Thus, they are hunters, but they can survive by feeding on carrion, insects, or fruit. By ridding wild herds of weaker animals and eliminating already doomed individuals, they play their part in the natural balance.

Originally probably inhabiting the Great Plains, the southwestern United States, and Mexico, coyotes have greatly expanded their habitat, although uniquely American, today also includes deserts, mountains, and forests. And the outskirts of large cities. Thanks to man, who changed the environment and hunted wolves until their almost total extinction, their current territory is immense because they have taken over the vast areas formerly occupied.

THE LIFE OF THE COYOTE

A SILENT AND INTELLIGENT HUNT

The coyote is a solitary hunter that feeds on anything it can catch. In the central plains, where the climatic conditions are relatively stable, it has the same essential diet all year round, made up for more than 75% of hares. Rabbits, mice, pheasants are also among his favorite prey. Occasionally it does not disdain muskrats, raccoons, polecats, opossums, and beavers, as well as snakes and large insects.

In late summer and fall, the coyote will eat fruit that has fallen to the ground. Blackberries, blueberries, pears, apples, peanuts then represent 50% of his diet. He knows how to choose a fully ripe watermelon and cut it in half to taste its juicy pulp. Neither does he disdain the soybean meal or cottonseed meal distributed to cattle.

In more arid environments, such as Mexico, the coyote mainly hunts small rodents. It also attacks marmots and ground squirrels in Canada, ground squirrels that look like large guinea pigs. But these two species hibernate, and in winter, in these northern regions, it is forced, to survive, to become a scavenger.

In suburban or urban areas, the coyote feeds on human waste, products manufactured by him, such as dog food, or even his pets.

ALONE OR IN COOPERATION

When it hears prey or spots it from afar thanks to its keen eyesight, the coyote approaches it silently, facing the wind, tail low, with slow steps interspersed with pauses. Arrived at 2 meters from his victim, he leaps on her and bites her neck. To finish her off, he keeps her in his mouth and shakes her violently. Death is quick. It usually devours the animal on the spot, even eating the bones of small prey.

When coyotes live together, they choose larger prey such as deer, elk, and other ungulates. They run around the herd. In a panic, an individual is isolated, then surrounded and attacked.

When the coyotes hunt in pairs, they force the isolated to run in a circle, taking turns to tire them out. This technique is used with caribou. The killed prey is disemboweled with claws and teeth and divided.

TWILIGHT AND MORNING HUNTERS

Twilight and morning hunters

Essentially nocturnal, the adults move around a lot, hunting more readily at dawn or dusk. On the other hand, young people between 4 months and a year old move more during the day and less at night. Their often unsuccessful hunting attempts force them to devote a lot of time to it, but they still have no territory or offspring to watch over.

SCAVENGER TO SURVIVE IN WINTER

In Alaska and in several Canadian provinces, where they arrived following the gold miners in the mid-nineteenth th century, coyotes have learned to face the bitter cold of winter. In these regions, animals must live and feed when the temperature is -10 ° C. The thick fur of the Far North's coyotes covers their whole body and has the same insulating power as that of the gray wolf. The guard hairs reach 11 cm long compared to 5 cm in animals living in a warmer climate. Thick and tight, the undercoat can measure 5 cm in thickness.

But the coyote does not run well in thick snow. However, hares and rabbits do not come out of their burrows when the outside temperature is too low, and groundhogs hibernate. The coyote would not survive the winter if it did not fall back on dead animals. Feeding on all the carrion he finds, he shares them with his fellows.

However, if the wolves arrive, he must give way. He sometimes buries or hides to return to them later. Its best ally is the cold, which finishes off sick or weakened animals, often at the tail of herds of large herbivores. Thus, in winter, it therefore, moves after the latter, devouring dead ungulates. Watching for the slightest failure, he does not hesitate to give the "coup de grace" to elk or caribou, exhausted and unable to defend themselves. If the snow is not too thick and the carrion is insufficient, the coyotes will join forces to attack.

OFTEN SOLITARY, THE COYOTE PREFERS TO LIVE AS A COUPLE

Halfway between the fox, solitary, and the wolf, which lives in organized packs, the coyote is a relatively pleasant animal. The male-female pair is the basic unit of this society, where one also meets many solitary animals and herds.

The couple is formed in the middle of winter, at the beginning of the mating season, and sometimes remain united for several years, sharing den and territory.

HIERARCHICAL FAMILY GROUPS

In areas where the density of coyotes is relatively low, some animals live solitary. Usually, they are the ones who howl at nightfall from the top of the steep rocks.

In regions where coyotes are numerous and food abundant, small groups are formed, comprising 5 or 6 individuals, that is to say, the parents accompanied by the young of the previous year. These family groups are hierarchical, with the oldest animals dominating and leading the rest of the herd. This type of association also appears when small rodents become scarce. Only substantial cooperation then allows the coyotes to catch animals the size of an elk or a caribou, often faster than them.

Real clashes between coyotes are rare. Grunts and stern expressions are often enough for animals to give up the fight and submit. He must then leave the winner's territory or abandon him the carcass on which he is feasting.

Gambling is frequent. Fake fights, chases, and nibbling are expected in a family. This is part of the education of young people: parents teach them to communicate and to hunt.

THE CRY OF THE COYOTE

The repertoire of coyotes is immense: barks like a dog, howl like a wolf, barks like a small puppy, growls ... They use combinations of all these sounds to call the members of their group signal their presence or immediate danger. They also seem to enjoy listening to each other bark or howl in the dark. This is how the solitary animals gathering for a hunting party at nightfall bring about a discordant concert famous throughout the American West and audible for miles around.

A VARIABLE AREA

Each coyote, each couple or family group has its territory, centered on the lodge or den. The limits of this territory are marked by all the occupants, who mark it out very regularly by urinating. But few coyotes fight to deny the entry of their domain to a congener. The dominated animal is content to move away to seek asylum elsewhere. However, it seems that groups defend their territory more actively than pairs or solitary animals. Loud crashes, but not very violent, sometimes take place at the borders. The coyotes seem to recognize each other from a distance, up to 200 m. When two individuals meet, if they already know each other, they go their way.

The territory (from a few kilometers to over 50 km) depends on coyotes' density in the region, the season, and the abundance of prey. A study conducted in the Yukon Territory, in northwestern Canada, showed that the thickness of coyotes varies from 1 to 9 individuals per 100 km 2 in winter to 2.3 individuals per km 2 in summer. Instead of traveling at night - on average, a coyote crosses, during a night's hunt, 4 km - coyotes can make long journeys to find territory or for food.

BODY LANGUAGE

Body language

The whole body of the coyote is used to make itself understood. Rolling up the lips, lowering or raising the tail, flattening or raising the ears, making the hair stand up are all signals. The coat's black patches further reinforce the facial expressions: lips edged with white hairs around the ears' eyes and lips. A dominant coyote opens its eyes wide. An angry coyote flattens its ears. Aggression is indicated by the erect ears, the raised shoulders, the hair on the back bristling, the lips rolled up, the tail slightly raised. A submissive male shows his genitals to the opponent.

AT NINE MONTHS, THE YOUNG ARE ADULTS

The mating season lasts from January to March but begins earlier in the North than in the South. More than 90% of females at least 20 months old go into heat. About 60% of 10-month-old females wait until the end of February if weather conditions are favorable. If the winter is too harsh, they will wait another year to mate.

Males are attracted early on by the smell of hormones in the urine of females in heat. Their courtship is assiduous for several weeks because before fertilization (pre-estrus) lasts from 2 to 3 months. Often, several males are interested in the same female and follow her without a fight. At the time of estrus, which lasts ten days, the female chooses her future partner and comes to give him a few blows of the muzzle. Like other canids, coyotes can stay mated for more than 25 minutes. The other males present do not try to intervene and leave to try their luck with a still available female.

A DEVOTED FATHER

The couple demarcates a new territory, choose and clean an old badger, marmot, or fox burrow, or decide to dig a new den. During gestation, which lasts about two months (on average 63 days), both mates hunt together and sleep side by side. When the birth approaches, the male manages alone to ensure the daily pittance, and he brings food to his companion. This one arranges the burrow by depositing there leaves, grasses, or hairs torn from its belly. Some females give birth to their young on the bare ground.

A litter includes between 2 and 12 young (on average, 4). Both parents take care of them. Thus, the father helps with the toilet and feeding of the young after they have been weaned. He guards the entrance to the burrow. In case of danger, he transports the young people, one by one, to a safe refuge, sometimes several kilometers away.

For the first ten days, the little ones suck about every 2 hours. Their eyes open around the tenth day. The first teeth appear around the twelfth day. They walk around three weeks and then begin to come out of the den, watched by the parents, to explore their environment. They run before they are six weeks old. They are generally weaned at the age of 1 month but receive in relay regurgitated meat by both parents. They begin to prey on dead prey, mice, then rabbits.

Generally, young males emancipate themselves and leave their family group between 6 and 9 months. Young females tend to stay with their parents.

THE COYOTE'S DEN

The coyote's den

When the coyote does not build an ancient badger or fox den to give birth to its litter, it digs one, very characteristic. The entrance, unique, 30 to 60 cm in diameter, is often hidden by bushes. About 3 m long and 40 to 50 cm wide, a tunnel connects it to a central room, or nursery, where the little ones will be installed. About 1.50 m in diameter, it is well ventilated, as the air enters it through a ventilation chimney.

TO KNOW EVERYTHING ABOUT THE COYOTE

COYOTE (CANIS LATRANS)

The coyote is much smaller than the wolf. However, its size varies depending on the region, between 75 cm and 1 m (tail included), as well as its weight, between 7 and 21 kg. The female is always smaller than the male.

The coat is shorter in Mexican coyotes than in the Great Plains and the Far North prairies. It consists of a down (5 cm maximum) and guard hairs (11 cm top). The molt takes place once a year, in summer in the North, the new shorter hair gradually replacing the old one. The color of the back and sides ranges from gray to dull yellow. The back coat and tail hairs are fringed with black. The throat is white, while the chest and belly are instead a pale gray. The back of the ears are reddish, and the muzzle greyish. The coloring varies, with southern animals often being lighter in color than northern ones, sometimes almost entirely black.

The coyote's nose is smaller than that of the wolf, its skull is more massive, its footpads narrower, and its ears longer.

The coyote can leap 2 m and maintain a cruising speed of 40 to 50 km / h; on short trips, its peaks can reach 65 km / h. Coyotes can travel great distances. Some animals, equipped with a radio collar, were followed for more than 650 km.

An excellent swimmer, the coyote in pursuit of prey, does not hesitate to jump into the water. In addition to its usual game, mustelids, frogs, newts, snakes, fish, crayfish can appear on its menu. It is also one of the few predators to attack the beaver.

He is undoubtedly the canine with the most developed senses. Able to see 200 m in open terrain, it can see both day and night.

His vocal repertoire is varied, but his most characteristic calls are heard at nightfall, daybreak, or during the night. They consist of a series of yapping followed by a long howl.

Also Read: https://outsideneed.com/hunting-coyotes-at-night-tips/

0 notes

Text

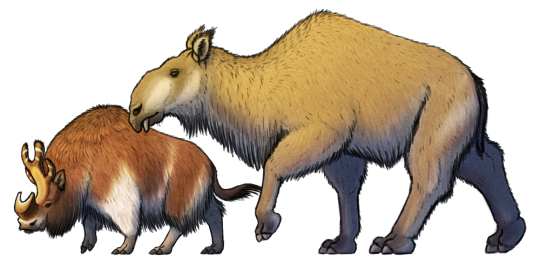

Today's #Spectember concept is a combination of a couple of anonymous submissions:

These two animals are the descendants of brontotheres and paraceratheres, almost the last living representatives of their kinds, hanging on in the equivalent of modern-day times in a world similar to our own.

But in this timeline some of the North American brontotheres managed to cope with the cooling drying climate of the Oligocene, adapting their teeth and their diet to grazing the spreading scrublands and grasslands. They became smaller and somewhat less bulky, built more like tapirs or wild boars than their previous rhino-like forms, and although they were now able to move faster in the more open environments their main defense was actually their highly social herding behavior – relying on strength in numbers and collectively mobbing predators.

Males also developed increasingly elaborate head ornamentation, like mammalian versions of ceratopsids, with ossicone-like projections on the back of their skulls as well as on their noses.

But they never regained their kind's previous success or diversity, instead remaining as a fairly minor element of the North American plains fauna. They began to decline against the rise of more specialized ungulates and smarter pack-hunting carnivorans, but one lineage did manage to disperse into South America during the Great American Biotic Interchange before the remaining North American brontotheres died out entirely.

Now the crowned brontothere (Brontochlos coronatus) is one of the last remnants of the whole group*, living in the Patagonian Steppe of southern South America. A relict species from the last ice age, under its thick coat of hair it's only about the size of a sheep – around 1m tall (3'3").

(*There is one other still-extant lineage of brontotheres in this world, but that's a subject for another time.)

———

Meanwhile the Asian paraceratheres survived and went through a similar shift towards tougher diets and smaller body size. No longer the titans they once were, they never again exceeded the size of the largest horses and instead converged on camelids and macraucheniids.

They reached North America via Beringia in the late Miocene, but struggled to establish themselves alongside the native camelids at the time – and the later camel dispersal into Asia would eventually push the remaining paraceratheres there towards extinction, too. But, much like the brontotheres, a few paraceratheres did make it all the way down into South America and persisted for longer, taking advantage of the ecological vacancies left by the already-dwindling native ungulates.

The woolly paracerathere (Ebursonora glacialis) is one of the last paraceratheres, sharing the same Patagonian Steppe habitat as the crowned brontotheres. Just under 2m tall (6'6"), it has a highly prehensile upper lip and a large bulbous nasal cavity that acts as both a saiga-like air filter and as a resonating chamber.

———

Despite sometimes competing with each other for the same food resources, these two species have developed something of a mutualistic relationship with each other. The social crowned brontotheres will often incorporate one or two woolly paraceratheres into their herds – often young "solitary" males of the species – due to the paraceratheres' larger size and better ability to spot threats at a distance. In exchange for acting as an early warning system, the paraceratheres gain the protection of the whole brontothere mob, increasing their own survival odds in a harsh environment still stalked by sabertoothed cats and the occasional terror bird.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#spectember#spectember 2022#speculative evolution#brontothere#paracerathere#perissodactyla#ungulate#mammal#art#science illustration

359 notes

·

View notes

Text

ASK MEME

Tagged by @selenomancer

Gender: Female

Star Sign: Sun in Libra, Moon in Aquarius, Gemini Rising

Height: 5'5"

Sexual Orientation: Asexual

Hogwarts House: Ravenclaw

Favorite color: Cerulean, Leaf Green, Emerald Green, Amethyst.. jewel tones, basically. Pastels and rainbows ok too.

Favorite animal: This is difficult. Imaginary? Dragons, but unicorns vomiting rainbows ok too. Local wildlife? Owls, coyotes, corvids, orcas, wolves, native ungulates. Non local wildlife? All the geckos, badgers, equines, lammergeier, terrestrial isopods, freshwater aussie and south american fish.. I love a lot of critters very much.

Average hours of sleep: Optimally 9 hours, less functionally 6-8, non functionality at 2-5, and weirdly totally functional on 1 hour of sleep. Naps are wonderful, 2 hours are my "I don't need much" naps and 4 hours are my "oh god I am sleep deprived and mostly dead" recovery naps.

Cat or dog person: Cats without a doubt, I've been speaking cat all my life. I've learned dog but they're not generally my favorite(*exceptions are working breeds, which are generally far and above in intelligence, good behavior, and purposed - I get along with them like I do cats).

Favorite fictional characters: Mowgli, Calvin (& Hobbes), Alexia Tarabotti, Bean (Ender's Game/Shadow), Arlian of the Smoking Mountains, Darian Firkin, Darkwind K'Sheyna, Alberich of Karse(& Kantor), Captain William Laurence (& Temeraire), Kohaku River, Sophie Hatter, Ashitaka, Korben Dallas, Chris Nielsen, Mr. Darcy, Belle, Randy Maclean(& Dee), Tsume, Edward Elric, Caim (& Angela), Sora, Toan (& Xiao).. literally could go on forever.

Number of blankets I sleep with: One raggedy brown comforter reminiscent of a childhood quilt long gone to tatters, a faux fawn throw(only on the really cold nights, I prefer sleeping cool), a couple of microfiber blankets stuffed in the cracks between the bed and wall(anti-spider barrier).. I like blankets. ouo;;;;

Favorite singer/band: Rob Thomas/Matchbox 20, Imogen Heap, Amethystium, Lindsey Stirling, Ulrich Schnauss, Enya, Seal, Enigma, Two Steps From Hell, E. S. Posthumus, Scatman, One Republic, Maroon 5, Assemblage 23, Magna Canta, OceanLab, Ryan Farish...

Dream trip: Tinley Park NARBC, New Caledonia, road tripping in general.. maybe the world renowned Hamm show in Germany.

Dream job: librarian, research assistant, wildlife conservation, reptile and wildlife educator..

When was this blog made: February 6th, 2012.

# of followers: 176, but only 120-ish are organic/real humans. Hi humans! <3

What made you decide to create this blog: Friends on the tumblrs, and the allure of a visually oriented, relaxed blog. I've made new friends, connected with old, enjoy news and art and photography from all over. I'm very thankful for the enrichment tumblr has to offer(selectively, lol..).

Tags? Whoever wants to do this, by all means. I love getting to know friends and followers better, there's nobody better at being you than you!

1 note

·

View note

Text

National Fossil: Panama

The columbian mammoths have won in Mexico!

The fossil record for many Central American countries is a bit scarce, so I‘m gonna skip over to Panama, while I think about what to do with the other countries.

Once again, you get to vote on which fossil should represent the nation. As always, it could be a fossil that is just exceptionally well preserved and beautiful, had a huge impact on paleontology and our knowledge of the past, is very common/representative of the area, is beloved and famous in the public eye, is just a very unique and interesting find, or has any other justification.

Here are your options:

Panamacebus: Our first (and very fittingly named) candidate is only known from a couple of teeth, but they are very important teeth, as they mark the oldest known instance of South American animals making it over to North America (the two continents used to be divided by sea). The capuchin like monkey lived 20 million years ago, more than 10 million years before the next known case of this migration happened

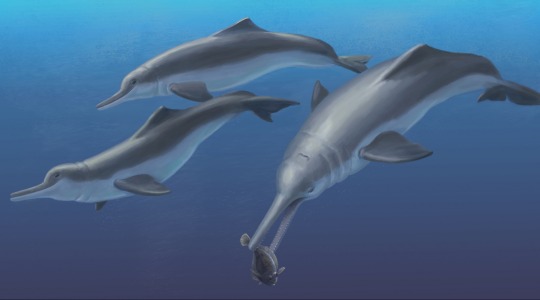

Isthminia: Named after the Isthmus of Panama the river dolphin was a relative to modern Amazon river dolphins (Art by Julia Molnar)

Purussaurus: It is a giant crocodile with size estimates upwards of 10 m, what else do I need to say? They lived during the Miocene in South America, but were also found in Panama

Mixotoxodon: Only known from fragmentary remains, but this is the only one of the South American Native Ungulates (a weird brand of ungulates not related to any of the other ones we have today) that made it into Central America once the two landmasses connected (Art by Bran-Artworks)

Scelidotherium: I have to give some ground sloth representation! This one looks almost like an ant-eater and was found in South America and also Panama (Art by Martina Chernelli)

Cuvieronius: This one is from an originally North American animal group, the gomphotheres (related to elephants). Cuvieronius was among the last of its kind only becoming extinct at the end of the Pleistocene. Their range extended all the way from the southern US through Central America and into South America

#paleontology#paleoblr#fossils#panamacebus#isthminia#purussaurus#mixotoxodon#scelidotherium#cuvieronius

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Darwin´s ´strangest animal ever´ finds a family | Amazing

Darwin´s ´strangest animal ever´ finds a family | Amazing

[ad_1]

An artist’s rendering shows the South American native ungulate Macrauchenia patachonica which had a number of remarkable adaptations, including the positioning of its nostrils high on its head in this illustration released on March 17, 2015. Photo: Reuters

PARIS: Charles Darwin, Mr. Evolution himself, didn´t know what to make of the fossils he saw in Patagonia so he sent them to his…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Who are the real pests?

Since Charles Darwin sailed around South America less than 200 years ago – a blip in the Earth’s history – the human population has mushroomed exponentially, from less than 1.2 to around 3.5 billion in 1968 and now approaching eight billion people.

This uncontrolled population growth is the inconvenient truth we can no longer skirt around, as David Attenborough recently warned. Now, two papers have highlighted its impact on wildlife through disrupted ecosystems.

People and livestock comprise a whopping 97% of the global mammal biomass, notes one group of scientists in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, and our tentacles have infiltrated the natural balance on every continent.

“We have affected most life forms through climate modification, harvest, erasure and fragmentation of habitat, disease, and the casting of alien species,” the international team of field scientists writes.

Led by Joel Berger from Colorado State University, US, they each drew from their own work on different continents, merged with other research, to document changes among and between species that impact native ungulates.

These are hoofed mammals ranging from the tiny Javan mouse deer (Tragulus javanicus) to the seven tonne African elephant (Loxodonta Africana), that are embedded in complex predator-prey and broader ecological dynamics.

The impacts the team identified ricochet throughout the biosphere.

Changing climates have caused toxic algal blooms in the Patagonian Pacific, in turn decreasing fish available for harvest. In search of other food sources, fishermen use dogs to hunt huemul (Hippocamelus bisculcus), a beautiful and now rare species of deer that has dwindled to 1% of its former range.

A Patagonian huemul deer (Hippocamelus bisulcus ). Credit: Joel Berger/ Colorado State University

Receding ice in once-pristine areas of the Himalayas has attracted human colonisation, along with stray and feral dogs that hunt rare, endangered ungulates including kiang (Equus kiang), chiru (Pantholops hodgsonii), saiga (Saiga tatarica) and takin (Budorcas taxicolor). They’ve also spread diseases and driven away snow leopards (Panthera uncia).

The multi-billion-dollar fashion industry’s appetite for cashmere has accelerated breeding of domestic goats – mostly in Mongolia, China and India – which compete with native ungulates for food and are in turn at risk from feral dogs.

Feral pigs have spread to every continent except Antarctica, and in 70% of US states, disrupting fish, reptiles, birds and other small mammals, plants and soils.

In the US, a century of intensive livestock grazing in the Great Basin Desert has disrupted plant communities, encouraging mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) populations which attracted pumas (Panthera concolor) and have thus permanently changed predator-prey dynamics.

The impacts the team identified ricochet throughout the biosphere.

Colombia is now home to wild hippos, Australia has banteng, and New Mexico has gemsbok (Oryx gazelle) and Barbary sheep, while Burmese pythons contributed to the downfall of white-tailed deer and reconfigured the Everglades food web.

It’s a mess, they say, and future repercussions are unpredictable. What we do know is that things can never go back to the way they were.

“For many assemblages of animals, we are nearing a moment in time, when, like Humpty Dumpty, we will not be able to put things back together again,” says Berger.

In an effort to conserve biodiversity, protected areas have been implemented worldwide; however, alien species threaten to infiltrate them, according to the second paper published in the journal Nature Communications.

Along with habitat destruction, pollution and CO2 emissions, alien species are one of the top five major threats to global biodiversity loss, says co-author Tim Blackburn from University College London, UK – and they are becoming more pervasive.

He and a team of Chinese researchers, including lead author Xuan Liu from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, investigated nearly 900 terrestrial animal species, including mammals, birds, reptiles and invertebrates, known to have become established in new environments around the world.

They then determined if these species live within or near the boundaries of nearly 200,000 protected areas, defined by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, including wilderness, national parks and natural monuments or features.

The American mink ( Neovison vison) was found in 1251 protected areas. Credit: Professor Tim Blackburn, UCL

Encouragingly, less than 10% of the protected areas, which cover about 15% of the Earth’s land surface, currently contain alien species, suggesting they are doing their job. However, nearly all are at risk of invasion – 99% of protected areas had alien species within 100 kilometres of their boundaries, and 89% within a mere 10 kilometres.

This is a problem, because the team determined that more than 95% of protected areas have environments within which at least some of the alien species could flourish once they get in.

Tellingly, areas that already contained alien species were those with a larger human footprint due to transport links and high human population density nearby.

“At the moment, most protected areas are still free of most animal invaders, but this might not last,” says senior author Li Yiming. “Areas readily accessible to large numbers of people are the most vulnerable.”

Alien species that have infiltrated include the cane toad (Rhinella marina) in 265 protected areas including Australia’s Kakadu National Park, and the Harlequin ladybird (Harmonia axyridis) and wild rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) in 2686 and 1673 protected areas, respectively.

The most invaded parks were found in Hawaii’s Volcanoes National Park, Hakalau Forest National Wildlife Refuge and Kipuka Ainahou.

“Human activities are putting lots of different pressures on the natural world,” Blackburn says. “The so-called developed nations are the worst offenders, as the richest 10% of humanity uses 50% of current resources.

“We urgently need to move to a way of living that is not destroying the life support systems that we depend on.”

Berger’s team says although food webs and ecosystems are changing, with concerted efforts all is not yet lost.

“Basically, the world is changing, it has changed, and it will continue to change,” he says. “From a more positive side, though, there are so many places worth protecting that even with change, they still reflect processes, species and hope.”

The post Who are the real pests? appeared first on Cosmos Magazine.

Who are the real pests? published first on https://triviaqaweb.weebly.com/

0 notes

Text

A history of Scotland.

Scotland was invented quite a while ago (I'll check later, I've got a calendar through in my kitchen which tells you the date it happened but I can't be arsed getting up at the moment. I'm pretty sure it was a Wednesday though) when mildly cretinous inventor Billy Agesago wanted somewhere to store the wee bit hill n' glen that his granny had given him for Christmas (he wanted a bike from the poor old pensioner; the greedy cunt). After cleverly pasting it together from a couple of spare parts taken from old Airfix models and bits and pieces from an old Meccanno set, he decided to staple it onto the top of England, for a laugh. For centuries after it sat there doing nowt, but eventually some folk moved in, after getting kicked out of their old country for farting in church. Soon these early primitive people began to spread all over the place (they even went to Glasgow!), and even began to form their own rudimentary language. Just like that scene in Planet of the Apes it was a massive moment when, upon being offered another Tunnock's teacake by Jessie McTroglodyte, Hamish McAlpine first uttered a word: "aye". This was a massive step in the evolution of these early settlers, and soon they had formed enough language to be able to ask the driver of the Stagecoach bus for a ticket to Scara Brae to build some holiday villas.

Over time tribes began to form, or clans, such as the MacLeans (motto: Whit the fuck you lookin' at? family tartan: like a granny's picnic tablecloth), the Camerons (family motto: Square go cunt! family tartan: doesn't go with the curtains), the Dunbars (family motto: Hope yir next shite's a hedgehog, family tartan: looks garish in wedding photos), the MacDonalds (family motto: C'mon 'en! family tartan: Even Jonathon Ross widna be seen deid wearin' it), The Campbells (motto: Wid ye like some soup? Tartan: Migraine-inducing), the MacDonalds (motto: Tak a lang, hard, lick o’ ma shite; tartan: so last season), the Gordons (motto: Aye it’s perfectly legal, just touch it; tartan: tartany) and the Chans (motto: I told you we should have turned LEFT at the border; tartan: silky). These clans often fought with each other, usually over the remote, and when they weren’t fighting they were playing games together (the confusing twats), which over time became known as the Highland games. Events in the Highland games included tossing the caber (caber is an old Scots word for headmaster, and this controversial event was finally outlawed in 1901; leading to an 87% drop in applications for headmaster jobs in Scotland, and a coincidental rise of 87% in applications to the priesthood), hammer-throwing, shot-putting, Scrabble, Kerplunk, speed Heelan’-coo shaving, embroidery, anvil-headbutting, angry-facing, Call of Duty, ferret-bothering, and Celebrity cross-fit. When not fighting with each other they enjoyed fighting with their neighbours down south in England, mainly because each country thought that the other one “talked funny”. A bloke called Mel Gibson had a scrap with Englishman Stirling Moss and his pals after they took the piss out of his mullet on a night out, and he gave them a right kicking. They got their own back eventually though, when they got local heavy Eddie Longshanks and his crew to kill poor Mel by hanging, drawing, and quartering him. The Jewish bastards.

Over time though the Scots got a bit bored with fighting and playing games, so they decided to invent some stuff. Famous Scots inventions and discoveries include pizza; Belgium; the burp; flip-flops; the name Hamish; African-Americans; haggis; the decimal point; the number 17; this face I’m pulling just now; the Krankies; Oor Wullie; slap-bass; the KKK; Kim Yong Un; the Beatles; ironic moustaches; sombreros, and many, many more. With the royalties from these inventions they invested in something called the Darius scheme, in which they used up all the money sending the singer Darius to the X Factor and promoting him. Despite initial success Darius soon faded from the public eye, leaving Scotland heavily in debt, and they had no choice but to form a partnership with their neighbours down south. Ever since this union they two have gotten on famously, meeting up most weekends for a pint and to discuss Corrie, and in fact it went so swimmingly that they decided to go into business together, and called this new venture: The British Empire.

The British Empire (not to be confused with the Brittas Empire) came into being when the main men looked around at the world and realised that those silly foreigners were making a right arse of running their countries, and that the British could help them sort everything out; for a small fee. Soon we were sending ships out all over the world to educate and civilise, and Scots were right at the heart of this new venture, with exports of Krankies DVDs and shortbread to places such as India keeping the money flowing into the vaults. Soon they were squandering this new found wealth, and Edinburgh at the time became famously known as "Okapi-toon", due to the fashion for wealthy people to import okapis and walk the streets with them on leads. To own an okapi became a status of wealth, and many poorer people took to crudely painting pigs and trying to pass them off as okapis to pull the chicks. Over time sanitary conditions began to become a real problem due to all the okapi shit on the streets, and a virulent new disease caused by this exotic new ungulate faeces being everywhere took hold: "the hairy-hell". People who contracted the hairy-hell would at first show little symptoms apart from a sudden interest in acid-jazz and a fondness for corduroy slacks, but over time other, nastier symptoms would begin to manifest. After about week three the left nipple would begin to resemble a mildly irate Frenchman, and it was rumoured that in some particularly severe cases some family members even heard muttered Gallic threats coming from the nipple during the night. Around week five the unfortunate victim's hair would become matted and greasy, and profuse sweating became the norm. At week six hormonal changes kicked in, causing the victim to emit a powerful musk that was sexually alluring to moths, dogs, and people named Kevin. Many killed themselves in despair at the constant leg-humping from dogs and Kevins, and the annoying buzzing of moths flying around their heads carrying tiny bottles of wine. Week eight a leg would fall off, and around week ten was usually when the hairy hell itself kicked in: hair would begin sprouting all over the body, growing at a rate that no decent hairdresser could possibly keep up with, despite their best efforts. A victim could be Matt Lucas in the morning, Chewbacca in the afternoon, and look like the edges of Susan Boyle's underpants by the evening. The hairy freaks would eventually either kill themselves in despair, or boil to death in their beds due to the insulation the hair provided. Eventually the people of Edinburgh had enough of Okapi shit everywhere and boiling to death, so sold all the okapi to a passing Flemish butcher. Meanwhile, with their profits, the people of Glasgow bought a nice hat.

Eventually Britain got bored with the Empire and handed all the vastly-improved countries back to the natives, because we're nice like that. This left Scotland at a bit of a loose end, and after a couple of unsuccessful years spent trying to export alcoholics to disinterested countries for money, Wee Dodie Johnston hit upon the idea of selling all that oil we had lying around doing fuck all on the sea bed, and so he sold his old Ford Escort and built a couple of oil rigs with the profits ( minus the £47 he owed Archie the Hump for "services rendered" the previous Saturday).

0 notes

Text

New Post has been published on Top 10 of Anything and Everything!!!

New Post has been published on http://theverybesttop10.com/heaviest-terrestrial-mammals/

The Top 10 Heaviest Terrestrial Mammals Who Walk the Earth

The Top 10 Heaviest Terrestrial Mammals Who Walk the Earth

While we have seen the largest creatures on Earth many of them were water based. Today we take a look at the land mammals. The largest creatures to walk on Earth and while there aren’t many surprises who is on this list, their order might just surprise you…

The Top 10 Heaviest Terrestrial Mammals Who Walk the Earth

Cape buffalo

10 – Cape buffalo – Average weight: 1,000 kg/2,200 Ib

The African buffalo or Cape buffalo is a large African bovine. It is not closely related to the slightly larger wild water buffalo of Asia and its ancestry remains unclear.

Water buffalo

9 – Water buffalo – Average weight: 1,000 kg/2,200 Ib

The water buffalo or domestic Asian water buffalo is a large bovid originating in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and China. Today, it is also found in Europe, Australia, North America, South America and some African countries.

American bison

8 – American bison – Average weight: 1,000 kg/2,200 Ib

The American bison or simply bison, also commonly known as the American buffalo or simply buffalo, is a North American species of bison that once roamed the grasslands of North America in massive herds.

Gaur

7 – Gaur – Average weight: 1,360 kg/2,940 Ib

The gaur, also called the Indian bison, is the largest extant bovine. This species is native to the Indian Subcontinent and Southeast Asia. It has been listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List since 1986.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push();