#straus center for conservation and technical studies

Text

Harvard University has a library that protects the rarest colors in the world.

The Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies houses the Forbes Pigment Collection, which contains more than 2,500 samples of pigments, some incredibly rare and harvested from things like mummies, heavy metals, poisons, and precious minerals.

The collection was amassed by Edward Waldo Forbes (1873-1969), who directed Harvard's Fogg Museum, between 1910 and 1944.

Forbes is considered the Father of Art Conservation in the United States and spent most of his life traveling the world to collect various pigments that he used to authenticate classical Italian paintings.

The pigments are still used by art experts to authenticate and understand paintings.

#Harvard University#Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies#Forbes Pigment Collection#colors#pigments#Edward Forbes#Fogg Museum#Father of Art Conservation#art conservation#art#art experts#paintings#library

113 notes

·

View notes

Video

Pagan gods (Moloch) par Boston Public Library

Via Flickr :

File name: A1-Pagan_Gods-Moloch Title: Pagan gods (Moloch) Creator/Contributor: Sargent, John Singer, 1856-1925 (artist); Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies (sponsor) Date created: 2003 Physical description: 1 transparency : color ; 4 x 5 in. Summary: Mural depicting the Pagan God Moloch, who was known as the God of materialism and child sacrifice. Genre: Film transparencies; Paintings Subject: Murals; Religion; Gods; Moloch (Semitic deity) Notes: Title and other information from: John Singer Sargent's Triumph of religion at the Boston Public Library : creation and restoration / edited by Narayan Khandekar, Gianfranco Pocobene, Kate Smith. Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard Art Museum, 2009.; This mural was installed in the Boston Public Library in 1895. It is located on the west side of the north ceiling vault.; Photograph by William Kipp for the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies. Location: Sargent Gallery, Boston Public Library Rights: Rights status not evaluated

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

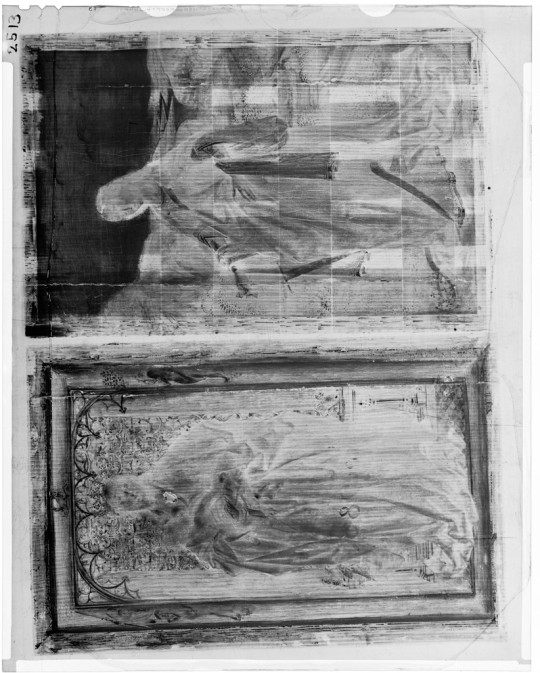

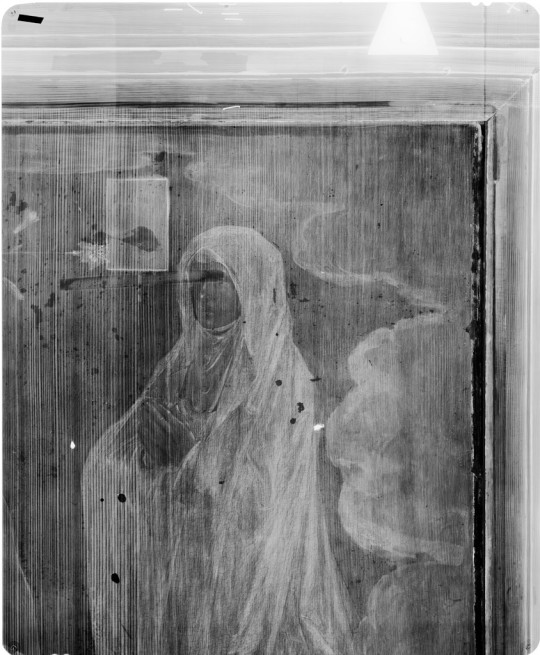

X-radiograph(s) of "Madonna and Child" and "St. Catherine" (diptych), Harvard Art Museums: Photographs

X-Radiograph Description: Overall Burroughs Number: 2513 X-Radiograph(s) of: Artist: Weyden, Rogier van der, Flemish, ca. 1399-1464 Title: Madonna and Child" and "St. Catherine" (diptych) Date: ca. 1440 Description: Oil on oak panel (cradle)... Harvard Art Museums/Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Alan Burroughs Collection of X-Radiographs

Size: film size: 14 x 17

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/346211

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Left Side Study of an Elegant Tern, Its Shadow and Reflection, Timothy David Mayhew, 2015, Harvard Art Museums: Drawings

Harvard Art Museums/Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Gift of the artist © Timothy David Mayhew 2015

Size: 28.1 × 11 cm (11 1/16 × 4 5/16 in.)

Medium: Natural black chalk, natural white chalk, and natural yellow chalk on handmade, blue laid paper

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/352940

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

YinMn Blue

Nautical, mystical and the de facto shade of several social networks, blue is a color that has deep cultural cachet, while being nearly impossible to find in nature. The blues that abound in nature — a butterfly, a navy beetle, even blue eyes — are not natively blue, according to scientists, but instead are reflections of light, the impression of blue.

Since antiquity, blue has been associated with rarity and expense; ultramarine — a pigment originally made from grinding lapis lazuli, a semiprecious gemstone found in Afghan mines — was once worth as much as gold.

Today, our blues are created by chemists in labs. But that doesn’t mean creating new shades is easy or common.

Before 2009, when a team of chemists at Oregon State University developed a color now known as YInMn Blue (quite unexpectedly), it had been 200 years since the last inorganic blue pigment was created. (That one was cobalt, discovered by French chemist Thénard in 1802.)

Now, YInMn Blue is available to artists as a paint and for commercial use. (The Environmental Protection Agency approved it for industrial coatings and plastics in 2017.) It has a home in the archive of the Forbes Pigment Collection at Harvard University, and has even inspired an addition to the spectrum of Crayola crayons — a striking shade called “Bluetiful.”

A Star Is Born

The shade was invented by Mas Subramanian, a professor of materials science at Oregon State University, who was working with a team of graduate students to develop an inorganic material that could be used for electronic devices. When a sample he had put in the furnace came out a vivid, vibrant hue of ultramarine, Subramanian said he immediately realized “the brilliant, very intense blues” were like nothing he had seen before, and would be better suited to use in paint than on pieces of technology.

“I was very curious why manganese did this because manganese is not known in pigments. So I was kind of surprised and thought maybe we made a mistake,” he said in an interview. “Then we decided to repeat the experiment.”

The blue proved stable, but it could also be slightly altered to get variations in hue. “We decided ‘OK, this is interesting for the pigment industry,’” Subramanian said.

The name for the new blue is derived from its chemical components’ symbols on the periodic table of elements: yttrium, indium and manganese.

The beauty of YInMn Blue is that it is not only able to be widely duplicated via Subramanian’s formula, but is also nontoxic, making it safer to use — and perhaps more eco-friendly too. “People think nearly everything related to the periodic table has some toxicity attached to it,” Subramanian said. “But this material so far is very stable, it doesn’t leach out in the rain or any acid conditions.”

“I know from experience that blue is a difficult color to make,” Subramanian said. “Most of the blues in nature are not real blues because they are all mostly made from the way light reflects from objects.”

Yet, together, at an extremely high temperature of 2,300 degrees Fahrenheit, the chemical compounds yttrium, indium and manganese combined to create an actual blue. And unlike organic plant-based hues that are less durable over time, this chemically derived color will not change.

Previous Pigments

The Forbes Pigment Collection at the Harvard Art Museums houses more than 2,500 pigments; YInMn Blue has recently been added and was prominently featured in a small display case on the fourth floor. Narayan Khandekar, a senior conservation scientist and director of the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies at the Harvard Art Museums, has been following the development of this pigment for years, and requested some of the earliest YInMn samples to add to the collection.

When pigments hit the market, Khandekar said, he and his team immediately get to work tracking down samples “because we believe that these are things that are going to be used in artist materials in the future.” Even when YInMn was fairly new, before it was commercially available, a prototype of a tube of artists paint in the color was made by the paint company Derivan and given to the Forbes Collection.

Subramanian’s blue also made it into the collection because it is a rare example of a wholly modern pigment, in contrast to the many pigments from the Middle Ages that are housed in the collection.

“It’s kind of an amazing thing that he was able to just look at something that was an accident. And then recognize how it could be applied to something that he had no experience with whatsoever,” Khandekar said of Subramanian. “You’ve got synthetic ultramarine, which came along in 1826, but that was synthesizing an already known pigment.”

There will be naysayers — those who say they can’t see much of a difference between ultramarine and YInMn Blue. But, Subramanian said: “This is a very special discovery because this is the first time my discovery has reached to the society with so much diversity — artists, architects, the fashion industry, even the cosmetics industry. I never would have imagined my discovery would go this far.” He added: “This changed my life.”

Khandekar agreed. “It’s not often that you come along with a synthetic inorganic pigment,” he said.

By Evan Nicole Brown.

#yinmn blue#blue#blueiscoool#blueiskewl#bluetiful#beautiful#beauty#the forbes pigment collection#mas subramanian#oregon state university

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

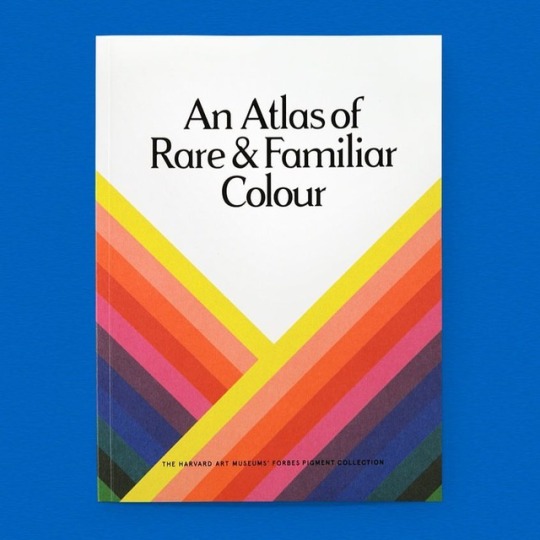

An Atlas of Rare & Familiar Colour / Available at www.draw-down.com / The Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies at the Harvard Art Museums encompasses over 2,500 of the world’s rarest pigments. #Museum director #EdwardForbes started the collection at the turn of the 20th century, in order to preserve the early Italian paintings he had begun to collect. Over the years, the collection grew into a huge apothecary of bottles and beakers, as other art lovers and color experts donated their own pigments. Today the collection continues to grow, and regularly helps experts across the world to research and authenticate paintings. Visually excavating the museums’ extraordinary collection, An Atlas of Rare & Familiar #Colour examines the contained pigments and artefacts—their provenance, composition, symbology, and application. It also explores the larger related fields of #chromatics, the historical #narratives of art and chemistry, and the innovations with which we have sought to better illustrate our aesthetic and expressive compulsions. Designed by #CapucineLabarth / Published by #AtelierÉditions 2019 https://www.instagram.com/p/BuljTRAHRvi/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1cjbtdrzxocmu

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brief on Features and Applications of Solvent Dyes, and The Chemistry of Pigments

The selection of solvent for preparing a working electrode (and to act as the electrolyte) is known to influence the efficiency of dye-sensitized solar cells. In this topical review, results taken from a systematic study are presented from the authors’ own lab examining how protic and aprotic solvents, as well as solvent polarity, affect adsorption of carboxylic dyes on the titanium dioxide nanoparticle surface and electron injection from the dye to the semiconductor. Adsorption of dye molecules on nanoparticle surfaces is measured through second harmonic light scattering and electron injection through ultrafast transient mid-infrared absorption. It is revealed that protic solvents do not allow direct adsorption of the dye onto the semiconductor surface, due to hydrogen bonding with the dye and competitive binding to the semiconductor surface. Aprotic solvents, on the other hand, support solvation of the dye molecules but also facilitate dye adsorption on the semiconductor nanoparticle. Among aprotic solvents, it is found that solvents with higher polarity result in larger adsorption free energy for the dye and faster electron injection. Overall, these studies reveal that aprotic solvents with high solvent polarity (such as acetonitrile) yield more efficient solar cell devices.

The world of dyes and pigments is vast and there are innumerable varieties of these colorants to fulfill the requirements of varied industrial and commercial sectors. Acid dyes, basic dyes, solvent dyes, lake colors, pigment colors are just to name a few from the vast ocean of colors. This article will talk in brief about the solvent dye.

Solvent dye is a dye that is soluble in plastics or organic solvents. When it goes with an organic solvent the dyeing process occurs in a solution. As the molecules of solvent dyes have a very small polarity or none at all there is no ionization involved in the dyeing process as it does, say, with acid dyes. Solvent dyes are normally water insoluble. One commonly used organic solvent with solvent dyes that is non-polar is petrol.

As for the naming of solvent dyes a standardized pattern is followed. In the pattern, the first word is always ‘solvent’ which is followed by the dye color and then a distinguishing number. For example, the varied shades of red are segregated by the distinct number that comes after the shade name like ‘Solvent Red 49’, ‘Solvent Red 1’, and ‘Solvent Red 24’ and so on. Another example of the shade red occurring in another type of dye is Pigment Red 48 which is an azo derivative from naphthalene.

Solvent dyes are pretty versatile and have found their way into a number of applications. One of their common uses is in the automotive sector to impart color to petrol fuel and other lubricants. Varied hydrocarbon based non-polar materials such as waxes and candles, coatings and wood stains are colored with the aid of solvent dyes. In the printing industry they go towards marking inkjet inks, inks and glass coloration. Textile printing is followed by the media industry where the solvent dyes are used for magazines and newspapers.

Dyeing of plastics is another application which uses solvent dyes because of its chemical compatibility. In the plastics industry these dyes lend color to a number of solid materials like nylon, acetates, polyester, PVC, acrylics, PETP, PMMA, styrene monomers, polystyrene and other fiber. They are also increasingly being used for smoke signaling in the pyrotechnics industry. A mention has to be made of its application in scientific research and medical diagnostics. Here, the solvent dye is used as an important component to produce stains that help in identification of varied components in a cell structure.

There are several advantages offered by solvent dyes that have led to its wide use in varied applications. Color shade consistency, superior light fastness, resistance to migration, good thermal stability, extremely dissolvable in plastics and lack of precipitation even after extensive storage are just to name some of its superior attributes.

However, sourcing solvent dyes from reputed solvent dyes manufacturers is highly important. This guarantees you the quality of the product and its effectiveness in the application it shall be used for. There are several reputed manufactures of these dyes and the names can be easily obtained from the online yellow pages.

At the heart of every drop of paint, every thread of cloth, every bit of your brightly colored phone case is a pigment. Pigments are the compounds added to materials to give them color. This deceptively simple application has shaped our perception of the world via art, fashion, and even computer displays and medicine. Pigments are used in paints, inks, plastic applications, fabrics, cosmetics, and food.

Some of the earliest chemistry was to make and isolate pigments for paints, and pigment conservation is a focus for many modern researchers who identify and preserve artwork.

Get to know pigments

But what is a organic pigment, exactly? Pigments are brightly colored, insoluble powders (brightly colored liquids are called dyes). In most cases, the bright color is a result of the material absorbing light in the visible spectrum. In inorganic pigments, this absorption is the result of charge transfer between a metal (transition metals are really good at this); organic pigments tend to have conjugated double bonds that absorb visible wavelengths.

Pigments are mixed with binders to attach them to a substrate. The resulting suspension—a paint—is used to coat materials and impart color onto them. In industry, there are three pigment classes: absorption pigments (used in watercolor paints), metal effect pigments (used to create surface luster), and pearlescent pigments.

Pigments are found in nature, such as ochre (a blend of iron oxides and hydroxides) and indigo (C16H10N2O2). They can also be synthetic pigments such as mauve (an aniline derivative) or white lead. White lead, one of the earliest synthetic pigments, is made by treating sheets of lead with vinegar. They are often more robust than dyes, which dissolve in the material they are coloring. Pigments can keep their color for many centuries and withstand high heat, intense light, and exposure to weather or chemical agents.

Cataloging colors

Because of their prominence in art, pigments have an important place in history. The Forbes Pigment Collection, housed in the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies at the Harvard Art Museums, catalogs and preserves more than 2,500 pigments. Its founder, Edward Forbes, started the collection by gathering pigment samples from his travels all over the world, including colors like mummy brown, made from ground-up mummies, and carmine red (C22H15AlCaO13), obtained from cochineal insects.

The Forbes Pigment Collection is often used as a reference library to standardize colors and identify pigment samples from artworks, which can confirm or disprove the piece’s origins. For instance, in 2007, a painting supposedly by Jackson Pollock was discovered to be a forgery when chemical analysis revealed the presence of pigments that weren’t available until decades after his death (Custer, 2007).

Furthermore, many artists had personal preferences and favored certain pigments over others. Thus, knowing which pigments were used, and whether they were in character for the artist or not, can help art historians determine an art piece’s authenticity.

The Forbes Pigment Collection, which boasts more than 60 natural samples, also highlights one of the challenges with natural pigments. Natural pigments were gathered from nature, for example, ore deposits, minerals, and flowers. But tiny shifts in chemical composition or particle growth cause specific shades to vary significantly due to impurities present in the sample.

Analyzing and understanding the high performance pigment used in paintings is also vital to artwork restoration and preservation. Many pigments chemically, like coating and paints, react with ambient light and humidity, as well as harsher substances like soot and smoke from cigars or fireplaces. Pigments may oxidize, dissolve in acid or water, undergo phase transitions, react with the binders in the paint, or degrade.

For example, eosin Y was a pigment historically favored by many artists, most notably Vincent van Gogh. Initially a vibrant red, exposure to light gradually turns eosin white as UV radiation excites the pigment molecules and leads to the production of OH radicals. This breaks down the structure of the pigment, and eventually turns it white. Knowing such information allows art historians to better conserve art.

0 notes

Text

Tiny Little Jars Contain Big, Bold Colors In The Forbes Pigment Collection

— NPR | October 29, 2020 | By Susan Stamberg at NPR Headquarters in Washington, D.C., May 21, 2019.

Looks like your spice rack on steroids? Nope. Although the colors are a feast for the eyes. Caitlin Cunningham Photography/Forbes Pigment Collection at the Harvard Art Museums (Photo by Allison Shelley)

Do you have a shrine? Religious, maybe, but not necessarily. A place where you are filled with awe?

I have several. One (you won't believe this) was the former Liberace Museum. Liberace, who died in 1987, was a fabulous musician with a collection of pianos, including one that once belonged to George Gershwin. (You must take a moment to watch this video of the understated, dignified Wladziu Valentino Liberace playing Gershwin on another piano in his collection.)

George Gershwin is my favorite composer. Seeing his piano at the Liberace Museum was such a thrill I simply could not resist touching the keys. Lightly. But verboten. Awed and still guilty, years later I confessed my transgression on the air to a curator there. "Don't feel badly," she said. "Every visitor does that."

Shrine No. 2 is the library at Princeton University. There for a story on F. Scott Fitzgerald, I asked the librarian to see some of the great author's papers. From a carton, he pulled out the manuscript of The Great Gatsby.

"Would you like a look at it?" Oh, old sport!

I actually held the page in my hands. No curator's gloves. The paper so brittle that edges flaked off at my touch (he was writing it in 1924). Guilty again, I reluctantly handed it back. But the thrill, the awe, remains.

All of which brings me to Ann Hoenigswald, retired conservator of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Asked about the Forbes Pigment Collection at the Harvard Art Museums, Hoenigswald said, "to a conservator, to see the display in Cambridge, it's really awe-inspiring .... almost like a shrine."

The Forbes Pigment Collection at the Harvard Art Museums.

Caitlin Cunningham Photography/Forbes Pigment Collection at the Harvard Art Museums

Those glass vials contain some of the more than 2,700 samples of pigments — colored particles mixed with material that binds them together — linseed or walnut or safflower oil, or eggs. Tada! Colored paint.

The Forbes Pigment Collection gives conservators, preservationists, artists, art historians and serious art fans a chance to see, analyze, imitate the precise colors used by various painters. Collection curator Narayan Khandekar says it's a chance to "have a conversation with the artist" even though he or she has been dead for centuries.

Van Gogh's 1888 Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin (left) and Emerald Green in the Forbes Pigment Collection. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum; Harvard Art Museums/Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies

Van Gogh used emerald green for this self-portrait. Bright, great to look at. "The trouble is that it's toxic," says conservation scientist Khandekar. "It's made from arsenic." Mixed with copper, it produces this gorgeous color.

Khandekar says there's speculation that when the British exiled Napoleon to Saint Helena, they covered the walls with emerald green wallpaper, perhaps to slowly poison him when humidity released particles into the island air. Nobody knows for sure. But as we say in journalism, never let facts get in the way of a good story.

It's remarkable how many nasty ingredients go into making some of the most beautiful colors: bugs, urine, manure.

Bugs first. The cochineal insect. Lives on cacti in Mexico and South America. Ground up, its shell makes an incredible bright red color. Your lipstick, your makeup, your Ferrari has cochineal dye in it.

The deep red color carmine is derived from an acid that cochineal insects produce to fend off predators. Desiree Martin/AFP via Getty Images

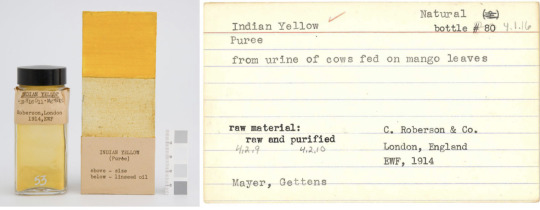

According to Khandekar, "it was the second largest source of wealth (after silver) for the Spanish empire." Urine from Indian cows (yes, you read it right) was pay dirt for painters like J.M.W. Turner, Thomas Gainsborough and Georges Seurat.

They and so many others used Indian Yellow — thanks to Asian cows that were only given mango leaves to eat. The color's not made this way these days. Mercifully.

Which brings us to manure. Again from cows. "They do pigments a great service, don't they?" observes Khandekar. There wouldn't be Lead White without them. Again, toxic. Again, used in cosmetics. Again, not made this way now. You'll have to listen to this link on the Forbes' new audio tour, to hear where the manure comes in.

Look (as Joe Biden would say), we can't just end with unpleasantries. So here's a perfectly proper blue in a Botticelli from the Harvard Art Museums' collection.

Botticelli's The Virgin and Child (left) and Ultramarine #4 (Lapis Lazuli; Genuine) in the Forbes Pigment Collection. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum; Harvard Art Museums/Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies

That Ultramarine Blue was made with crushed lapis lazuli, probably mined in Afghanistan. Botticelli used it six centuries ago. Old, but not that ancient as pigments go. The cavemen used charcoal and ochre pigments. Which shows how important creating art has always been to who we are as humans.

"These guys were out there hunting, gathering, trying to stay alive," Khandekar says. "And yet they still found time to make art."

Art Where You're At is an informal series showcasing lively online offerings at museums closed due to COVID-19, or at re-opening museums you may not be able to visit.

0 notes

Text

Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, United States

New Post has been published on https://hisour.com/place/america/harvard-art-museums-cambridge-united-states/

Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, United States

The Harvard Art Museums are part of Harvard University and comprise three museums: the Fogg Museum, the Busch-Reisinger Museum, and the Arthur M. Sackler Museum and four research centers: the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis, the Center for the Technical Study of Modern Art, the Harvard Art Museums Archives, and the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies. The Harvard Art Museums are newly united in a state-of-the-art facility designed by Renzo Piano Building Workshop. The renovation and expansion of the museums’ landmark building at 32 Quincy Street in Cambridge brings the three museums and their collections together under one roof for the first time, inviting students, faculty, scholars, and the public into one of the world’s great institutions for arts scholarship and research. The Harvard Art Museums have internationally renowned collections, which are among the largest art museum collections in the United States. Together, the collections consist of approximately 250,000 objects from the ancient world to the present and across all media, including objects from the Americas, Europe, North Africa, the Mediterranean, and Asia. The museums’ Special Exhibitions Gallery presents important new research on artists and artistic practice, and the University Galleries are programmed in consultation with Harvard faculty to support coursework. Lectures, workshops, films, performances, special events, and other programs are held throughout the year at the museums. [pt_view id="6e59499cf8"] The Harvard Art Museums are comprised of three separate museums—the Fogg Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum, and Arthur M. Sackler Museum—each with a different history, collection, guiding philosophy, and identity. Fogg Museum The Fogg Museum opened in 1895 on the northern edge of Harvard Yard in a modest Beaux-Arts building designed by Richard Morris Hunt, twenty-one years after the President and Fellows of Harvard College appointed Charles Eliot Norton the first professor of art history in America. It was made possible when, in 1891, Mrs. Elizabeth Fogg gave a gift in memory of her husband to build “an Art Museum to be called and known as the William Hayes Fogg Museum of Harvard College.” In 1927, the Fogg Museum moved to its home at 32 Quincy Street. Designed by architects Coolidge, Shepley, Bulfinch, and Abbott of Boston, the joint art museum and teaching facility was the first purpose-built structure for the specialized training of art scholars, conservators, and museum professionals in North America. With an early collection that consisted largely of plaster casts and photographs, the Fogg Museum is now renowned for its holdings of Western paintings, sculpture, decorative arts, photographs, prints, and drawings dating from the Middle Ages to the present. The Fogg Museum is renowned for its holdings of Western paintings, sculpture, decorative arts, photographs, prints, and drawings from the Middle Ages to the present. Particular strengths include Italian Renaissance, British Pre-Raphaelite, and French art of the 19th century, as well as 19th- and 20th-century American paintings and drawings. The museum's Maurice Wertheim Collection is a notable group of impressionist and post-impressionist works that contains many famous masterpieces, including paintings and sculptures by Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Vincent van Gogh. Central to the Fogg's holdings is the Grenville L. Winthrop Collection, with more than 4,000 works of art. Bequeathed to Harvard in 1943, the collection continues to play a pivotal role in shaping the legacy of the Harvard Art Museums, serving as a foundation for teaching, research, and professional training programs. It includes important 19th-century paintings, sculpture, and drawings by William Blake, Edward Burne-Jones, Jacques-Louis David, Honoré Daumier, Winslow Homer, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Alfred Barye, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Auguste Rodin, John Singer Sargent, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and James Abbott McNeill Whistler. The art museum has Late Medieval Italian paintings by the Master of Offida, Master of Camerino, Bernardo Daddi, Simone Martini, Luca di Tomme, Pietro Lorenzetti, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Master of Orcanesque Misercordia, Master of Saints Cosmas and Damiançand Bartolomeo Bulgarini. Flemish Renaissance paintings — Master of Catholic Kings, Jan Provoost, Master of Holy Blood, Aelbert Bouts, and Master of Saint Ursula. Italian Renaissance period paintings — Fra Angelico, Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Gherardo Starnina, Cosme Tura, Giovanni di Paolo, and Lorenzo Lotto. French Baroque period paintings — Nicolas Poussin, Jacques Stella, Nicolas Regnier, and Philippe de Champaigne. Dutch Master paintings — Rembrandt, Emanuel de Witte, Jan Steen, Willem Van de Velde, Jacob Van Ruisdael, Salomon van Ruysdael, Jan van der Heyden, and Dirck Hals. American paintings — Gilbert Stuart, Charles Willson Peale, Robert Feke, Sanford Gifford, James McNeil Whistler, John Singer Sargent, Thomas Eakins, Man Ray, Ben Shahn, Jacob Lawrence, Lewis Rubenstein, Robert Sloan, Phillip Guston, Jackson Pollock, Kerry James Marshall, and Clyfford Still. Busch-Reisinger Museum The Busch-Reisinger Museum was founded in 1901 as the Germanic Museum. Unique among North American museums, the Busch-Reisinger is dedicated to the study of all modes and periods of art from central and northern Europe, with an emphasis on German-speaking countries. In 1921 the Germanic Museum moved to Adolphus Busch Hall, built partly with funds from Adolphus Busch’s son-in-law, Hugo Reisinger, and in 1950 it was renamed the Busch-Reisinger Museum. The museum moved again in 1991, this time to Werner Otto Hall at 32 Quincy Street, designed by Gwathmey Siegel & Associates. Adolphus Busch Hall continues to house the founding collection of plaster casts of medieval art and is the venue for concerts on its world-renowned Flentrop pipe organ, while the Busch-Reisinger Museum’s holdings include significant works of Austrian Secession art, German expressionism, 1920s abstraction, and materials related to the Bauhaus. Other strengths include late-medieval sculpture and eighteenth-century art. The museum also holds noteworthy postwar and contemporary art from German-speaking Europe. The Busch-Reisinger Art Museum has oil paintings by artists Lovis Corinth, Max Liebermann, Gustav Klimt, Edvard Munch, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Max Ernst, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Franz Marc, Karl Schmidt-Rotluff, Emil Nolde, Erich Heckel, Heinrich Hoerle, Georg Baselitz, László Moholy-Nagy, and Max Beckmann. It has sculpture by Alfred Barye, Kathe Kollwitz, George Minne, and Ernst Barlach. From 1921 to 1991, the Busch-Reisinger was located in Adolphus Busch Hall at 29 Kirkland Street. The Hall continues to house the Busch-Reisinger's founding collection of medieval plaster casts and an exhibition on the history of the Busch–Reisinger Museum; it also hosts concerts on its Flentrop pipe organ. In 1991, the Busch-Reisinger moved to the new Werner Otto Hall, designed by Gwathmey Siegel & Associates, at 32 Quincy Street. Arthur M. Sackler Museum In 1912, Langdon Warner taught the first courses in Asian art at Harvard, and the first at any American university. By 1977, Harvard’s collections of Asian, ancient, and Islamic and later Indian art had grown sufficiently in size and importance to require a larger space for their display and study. With the generosity of Dr. Arthur M. Sackler, a leading psychiatrist, entrepreneur, art collector, and philanthropist, the Harvard Art Museums founded a museum dedicated to works from Asia, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean. The Arthur M. Sackler Museum, a new museum building at 485 Broadway designed by James Stirling, opened in 1985. This structure remains the home of the History of Art and Architecture Department and the Media Slide Library. The museum collection holds important collections of Asian art, most notably, archaic Chinese jades (the widest collection outside of China) and Japanese surimono, as well as outstanding Chinese bronzes, ceremonial weapons, Buddhist cave-temple sculptures, ceramics from China and Korea, Japanese works on paper, and lacquer boxes. The ancient Mediterranean and Byzantine collections comprise significant works in all media from Greece, Rome, Egypt, and the Near East. Strengths include Greek vases, small bronzes, and coins from throughout the ancient Mediterranean world. The museum also holds works on paper from Islamic lands and India, including paintings, drawings, calligraphy, and manuscript illustrations, with particular strength in Rajput art, as well as important Islamic ceramics from the 8th through 19th century. Renovation and Expansion The Harvard Art Museums’ recent renovation and expansion builds on the legacies of these three museums and unites their remarkable collections under one roof for the first time. Renzo Piano Building Workshop’s responsive design preserved the Fogg Museum’s landmark 1927 facility, while transforming the space to accommodate twenty-first-century needs. Following a six-year building project, the museums now feature 40 percent more gallery space, an expanded Art Study Center, conservation labs, and classrooms, and a striking new glass roof that bridges the facility’s historic and contemporary architecture. In line with Harvard’s commitment to sustainability, the museums’ renovation and expansion achieved LEED Gold certification for incorporating a wide range of green building technologies including, energy efficient LED bulbs and an innovative water conservation system. The new Harvard Art Museums’ building is more functional, accessible, spacious, and above all, more transparent. The three constituent museums retain their distinct identities in this new facility, yet their close proximity provides exciting opportunities to experience works of art in a broader context.

0 notes

Text

Helpful Answers For Crucial Factors For Textile Testing Methods

Textile by Jackie Cardy.

Oksana Ivanik Art @Oksana Ivanik Art

Outlines For Uncomplicated Strategies Of

To develop the collection’s 19 colorways, Olivares researched natural pigments such as the charcoal gray of carbon found in the earth’s crust. To develop the collection’s 19 colorways, Olivares researched natural pigments such as the charcoal gray of carbon found in the earth’s crust. The Harvard Art Museums’ Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies is renowned for its collection of rare, naturally occurring pigments. The Harvard Art Museums’ Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies is renowned for its collection of rare, naturally occurring pigments. To develop the collection’s 19 colorways, Olivares researched natural pigments such as the charcoal gray of carbon found in the earth’s crust. To develop the collection’s 19 colorways, Olivares researched natural pigments such as the charcoal gray of carbon found in the earth’s crust. To develop the collection’s 19 colorways, Olivares researched natural pigments such as the charcoal gray of carbon found in the earth’s crust. To develop the collection’s 19 colorways, Olivares researched natural pigments such as the charcoal gray of carbon found in the earth’s crust. To develop the collection’s 19 colorways, Olivares researched natural pigments such as the charcoal gray of carbon found in the earth’s crust.

For the original version including any supplementary images or video, visit http://www.metropolismag.com/homepage/jonathan-olivares-kvadrat-twill-weave-textile/

youtube

textile testing laboratory textile lab

0 notes

Photo

X-radiograph(s) of "Last Judgment", January 20, 1995, Harvard Art Museums: Photographs

X-Radiograph Description: X-Radiograph (12) X-Radiograph Settings: 5 ma, 75 kv, 3 1/2 min. Burroughs Number: 4406 X-Radiograph(s) of: Artist: Provost, Jan, the younger, Netherlandish, ca.1465-1529 Title: Last Judgment Owner: Harvard Univer... Harvard Art Museums/Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Alan Burroughs Collection of X-Radiographs

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/347744

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

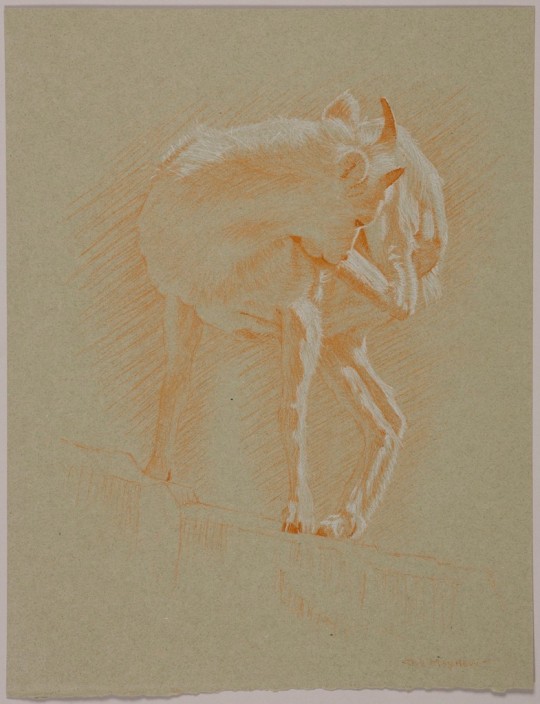

Study of a Juvenile Dall Sheep Scratching Its Neck, Timothy David Mayhew, 21st century, Harvard Art Museums: Drawings

Harvard Art Museums/Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Gift of the artist in memory of Craigen Bowen, the Philip and Lynn Straus Conservator of Works of Art on Paper and Deputy Director of the Straus Center for Conservation © Timothy David Mayhew

Size: 35.3 x 27.1 cm (13 7/8 x 10 11/16 in.)

Medium: Natural red and white chalk on handmade beige wove paper

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/324803

1 note

·

View note

Text

Just when I think I know all about special libraries...

...I discover another astonishing one! The Forbes Pigment Collection at the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies at Harvard Art Museums houses 2,500 colors created around the world!

The stories behind the making of these pigments is a weird testimony to human imagination -- like feeding cows mango leaves and collecting their urine to create “Indian yellow.” (Because mangos are yellow? But only on the inside. Whose idea was this, or did it happen by accident?)

But this collection isn’t merely a curiosity. Thanks to the center’s pigment analysis, an unearthed Jackson Pollack painting was discovered to be a fake. Oh science! <3

#libraries#harvard art museums#straus center for conservation and technical studies#awesomeness to the power of awesome

1 note

·

View note

Photo

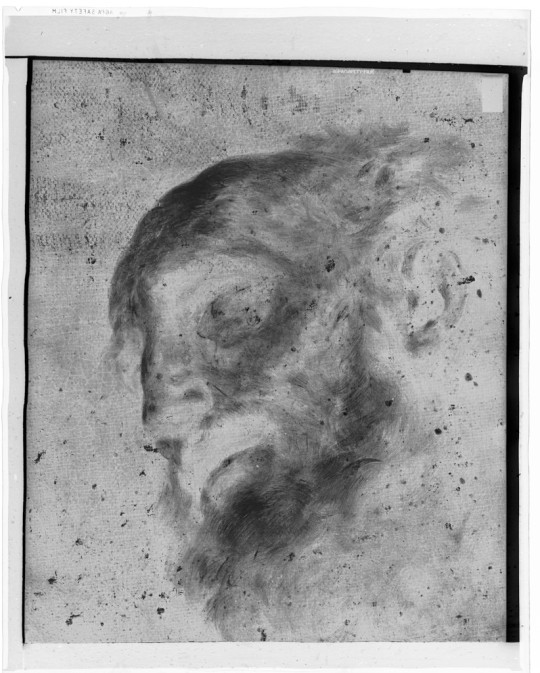

X-radiograph(s) of "St. Peter", Harvard Art Museums: Photographs

X-Radiograph Description: Negative, Prints Burroughs Number: 063 X-Radiograph(s) of: Artist: Feti, Domenico (?), Italian, ca.1589-1623 Artist: Also att. to Reni, Guido, Italian, 1575-1642 Title: St. Peter Owner: St. Gregory College, Shawnee,... Harvard Art Museums/Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Alan Burroughs Collection of X-Radiographs

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/343703

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

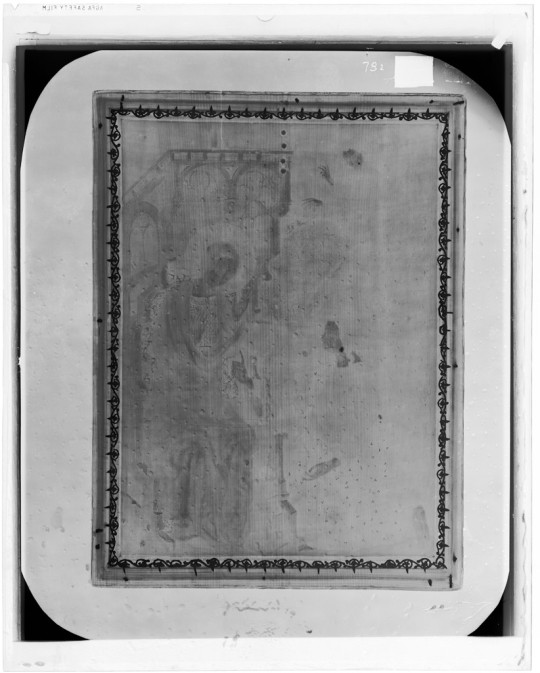

X-radiograph(s) of "Annunciation", Harvard Art Museums: Photographs

X-Radiograph Description: Negative Burroughs Number: 782 X-Radiograph(s) of: Artist: French School Title: Annunciation Date: 15th century Owner: Private Collection Harvard Art Museums/Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Alan Burroughs Collection of X-Radiographs

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/344493

32 notes

·

View notes