#that being said. i am hispanic and my childhood eyes saw spanish speaking latinos in every character.

Text

woop here we go-

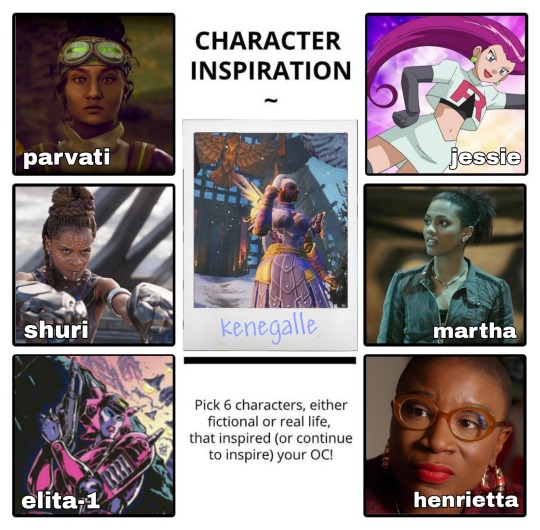

Women/girls in media beloved. In particular, Parvati, Elita, and Martha really impacted me as a teenager, and I already lean towards women of color when creating OCs for all my little series n books n games n whatnot. I hadn't thought too much about who influenced Kenegalle until I saw everyone else making this meme, so I dug deep and brought up all the ladies she carries a part of in her 💖💖

#WOC beloved and then there's jessie who's rockin with us#elita is an alien so human concepts of race and ethnicity don't really apppy to her huh#that being said. i am hispanic and my childhood eyes saw spanish speaking latinos in every character.#honorary latina elita-1. yes i am so based or whatever#PARVATI IS THE KENEGALLE BLUEPRINT BY THE WAY#Parvati 🤝 Kenegalle: i am an engineer and cheerful yet melancholy and also i miss my dad terribly#kenegalle speaks idk

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eraina

Where are you from?

Born: San Diego, California- Now: Most of my life in Georgia

How would you describe your race/ethnicity?

Mixed Race, includes being: African American, Chinese, and of Hispanic descent on Father's side.

Do you identify with one particular aspect of your ethnicity more than another? Have you ever felt pressure to choose between parts of your identity?

I do. I mainly feel inclined to identify as black as I was raised by my mother, who is black. My father wasn't really in my life, and only recently have we begun talking. This is one of the reasons why. But the other is that fact that I don't "look" chinese, and this has greatly messed with how I see myself.

Did your parents encounter any difficulties from being in an interracial relationship?

Not really. On both sides of my family, everyone was mixed up. My dad is Chinese and black-hispanic, and one of his sisters (my aunt) is Chinese and white. On my mom's side, I have cosins that are Japanese&Black, Porto Rican&Black, and Mexican&Black. So the relationship being mixed race was certainly not an issue, though I'll never know if they would've had problems raising me as a couple, that is uncertain.

How has your mixed background impacted your sense of identity and belonging?

Growing up, the topic of my race was very interesting. At first, I was always mistaken as another race. I didn't really see how strange it was, as my mom is very light skinned, and people would often think she was latina, just like me. But that happens so few and far between, so soon I found it strange that people expected me to know spanish, dispite just meeting me. Because of this, I had a hard time getting along with other black kids. I wasn't black enough. I was too light. And then I couldn't hang with the few asain kids in my school as I wasn't Chinese at all apparently. I felt alone. I felt unconfident in my asain heritage, and even though I felt ok with identifying as black, as I had for years, I started feeling weird saying I was black. I wasn't enough for anything.

Have you been asked questions like "What are you?" or "Where are you from?" by strangers? If so, how do you typically respond?

I normally get asked this if I'm out with my mom. I'm lighter than her, so when people see her skin compared to mine they realize I'm mixed and immediately start with the questions. At first I was happy that people saw that I was mixed and was interested. I would happily answer the questions. After a while the got a annoying and even offensive. I hate it when someone says, "You're really pretty for a black girl, what are mixed with?". It's like they're saying that black women can't be beautiful without being mixed with something, like all my cousins, aunts, and my mom aren't good enough to be beautiful. It's extra annoying when they first guess I'm mixed with white, looking so confident, and then when I say no, they get all confused. There are other races out there besides black and white!

Have you experienced people making comments about you based on your appearance?

Yes I have, bullied even. It was about my hair, and I have hair that's like my mother's, curly and kinky.

Have you ever been mistaken for another ethnicity?

Yep, normally a hispanic or latino nationality, like Mexican or Porto Rican.

Have you ever felt the need to change your behavior due to how you believe others will perceive you? In what way?

Yes actually. I've felt I needed to dress differently, talk differently, and listen to different music because too many of my friends have gotten on me for doing "white people things". Me not having an accent doesn't make me white, me not wearing the clothes you wear doesn't make me white, and me listening to different kinds of music doesn't me white; even less so if I'm actually listening to music that connects to my chinese side.

What positive benefits have you experienced by being mixed?

I wish I could say something, anything, but I can't. I only grew up with my mom and that's it. I didn't grow up with two cultures and had blended holidays and recipes. I just had my black mom raising me with her wonderful black family, where in my younger childhood I had prodominetly black friends. I've faced discrimination for being black, chinese, and mixed. For me, being mixed race was just in family line and blood. Something that just make me. Sometimes you're just mixed, the same way some people are only black, asain, native american, arab, pacific islander, etc. Seems sad to some, but I'm just me, being mixed.

Have you changed the way you identify yourself over the years?

Yes. I've never felt so fine with just saying I'm mixed race until now. If someone want to know what I am, I'm mixed. Yeah I'm black and chinese, but I'm not going to purposely choose a "side" any time soon.

Are you proud to be mixed?

Sometimes

Do you have any other stories you would like to share from your own experiences?

There this one moment that made me realize that I will never be asain to some people due to stupid stereotypes. My old "friend", Bella, said I wasn't chinese because I couldn't chinese (Also Bella, you speak Mandarin, not chinese.) I felt so, so, repulsed that she would say something so nonsensical. I never mentioned being mixed ever again. Especially after she said she was more likely to be chinese than me because she had "squity and small eyes". She said this, knowing full well that she was 100% black.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

For the Longest Time, I Didn’t Identify as Black

Pollyanna Rodrigues De La Rosa, who only recently began identifying as Afro-Latina (Photo: Roberto Caruso)

Pollyanna Rodrigues De La Rosa sat in the back of a cab, on her way to her favourite Toronto Latin music club, El Rancho. To get herself in the mood for a Saturday night of salsa, bachata and reggaeton, she asked the driver for the auxiliary cord to play “Eres Mia” by Romeo Santos from her phone. The music filled the cab and she sang along, the lyrics flowing smoothly off her tongue in Spanish, the language she speaks at home with her family. The driver raised his voice over the music and asked Rodrigues De La Rosa about her background—but her answer wasn’t what he was expecting.

“I thought you were Black!” he said. Rodrigues De La Rosa, who is part Cuban and part Panamanian, is used to this type of reaction. She stands at just over five feet tall, with big, long, black curly hair. Her dark skin matches her brown eyes, and if you saw her on the street you’d probably have no doubts about her racial identity, either.

But what the cab driver didn’t understand was that while she is indeed Black, she is also Latina. To be fair, Rodrigues De La Rosa didn’t always understand the nuances of her racial identity, either. “For the longest time, I actually didn’t know I was Black,” she says. That’s because, growing up, her family considered themselves Latino.

Though they shared the same skin tone and hair texture, her family never talked about their African heritage—in fact, they preferred to pretend it didn’t exist. Rodrigues De La Rosa’s mother even pressed her about her romantic choices, questioning why she dated Black men instead of white men. And the anti-Black racism was present in her extended family, too. When she visited Cuba in 2015, many of her family members would ask her to straighten her hair for a “better” look.

Between her family’s Latino identity and the anti-Black rhetoric she internalized, Rodrigues De La Rosa questioned whether or not she identified as Black.

Then, in 2015, she discovered a term on social media that she truly felt described her: Afro-Latina. The broad definition is simple—someone who identifies as Afro-Latina, Afro-Latino or the more inclusive and gender-neutral Afro-Latinx is Black and from Latin America. But the term’s meaning is much more political.

In these communities, which have a deep history of anti-Black racism, Afro-Latinx refers to “someone [from the Latino community] who reclaims their Africanness and Blackness, which for so many years was erased,” explains Columbian-Canadian academic Andrea Vasquez Jimenez, the co-director of the Latinx, Afro-Latin-America, Abya Yala Education Network (LAEN). “Utilizing terms such as Hispanic erases our Blackness.”

While Rodrigues De La Rosa may have felt like she stood out among her peers, she is actually part of a large cultural community. A quarter of the Hispanic population in the U.S. identifies as Afro-Latino according to a 2014 study. (Similar data is not available in Canada in part because though the census includes Black and Latin American as visible minority categories, there is no category combining the two identities. Respondents can write in their own classification, or mark all the categories that apply, but the data is counted towards the Black and Latin American categories separately.)

“I get looked at all the time when I start speaking Spanish. It’s still a culture shock, especially to old farts. I quickly let them know that there are Black people in [Cuba and Panama],” says Rodrigues De La Rosa, adding that people often seem to think that it’s impossible to be both Black and a Spanish-speaking Latina.

“When I heard the term Afro-Latina, as sad as this is going to sound, it was the first time I thought I was considered Black,” says Rodrigues De La Rosa. “I loved it.”

Unlearning anti-Black racism as an Afro-Latina

People like Rodrigues De La Rosa are why Jimenez started LAEN. She made sure the organization was a space for Afro-Latinx people to not only have a voice, but learn about their heritage.

“Blackness is global. An extremely high percentage of [people from Latin America] have African ancestry. The identities of Blackness, Africanness and being Latinx are not mutually exclusive,” says Jimenez.

The African diaspora originated with the transatlantic slave trade, when European colonizers dispersed millions of people from Africa to North America, South America and the Caribbean. And regardless of where slaves were taken, sexual violence was common. “This is the most f-cked up part, I don’t know if my Spanish ancestor loved my great-great-great-grandma or raped her,” says Rodrigues De La Rosa.

The intersectionality of Afro-Latinx people can get even more complex, especially for people like CityNews reporter Ginella Massa, who wears a hijab and is from Panama.

“Often, in the realm of my work, my Muslim identity is discussed; my ethnicity or my heritage are rarely ever mentioned,” says Massa. When she made headlines in 2016 for being the first hijabi news anchor, the coverage described her as a Muslim Canadian, but the Afro-Latinx aspect of her identity took a back seat.

CityNews reporter Ginella Massa

Even within Canadian Afro-Latinx communities, positive discussions about embracing all aspects of this intersectional identity are rare.

“Because of anti-Black racism, many folks don’t necessarily speak nor highlight our Blackness within families,” says Jimenez.

That’s especially true among older generations of Afro-Latinx people, who have internalized centuries of institutionalized anti-Black racism. Massa says her family’s Blackness was rarely discussed at home. Her family only focused on their Latin heritage.

“My grandmother, I can say this certainty, would never identify as Black,” says Massa. “I’m not sure where she got this from because to look at her, you would say she is a Black woman. But there is this obsession with light skin and desire to distance ourselves from Blackness.”

For Rodrigues De La Rosa, learning the term Afro-Latina was the catalyst that allowed her to understand her who she really was. She was tired of people constantly denying her parts of her heritage—but in embracing this term, she also had to go through a process of unlearning the anti-Black racism rooted in her community.

As she learned more, Rodrigues De La Rosa also tried teaching her family about their Afro-Latinx history. But it was challenging, especially since her mother, who grew up in Cuba, was ridiculed by other Cubans for her darker skin and tightly coiled hair.

“I’ve had to teach my mother to love herself more,” she says.

Amara La Negra and Afro-Latina celebs stepping into the spotlight

Celebrities such as Jennifer Lopez, Gina Rodriguez, and Camila Cabello are readily identified as representations of the Latinx community in Hollywood—yet celebs like Zoe Saldana, Orange is the New Black‘s Dascha Polanco and Cardi B are often denied their intersectional identity and instead solely seen as Black.

Earlier this year, reality TV star and singer Amara La Negra, whose parents are from the Dominican Republic, reignited the conversation about Afro-Latinx identity on Love and Hip Hop Miami. In the debut episode, La Negra and producer Young Hollywood were discussing ideas about how she should change her image to better promote her music. La Negra insisted her look represented her Afro-Latina heritage. In response, Hollywood proceeded to question her identity by asking, “Hold on! Afro-Latina? Elaborate, are you African or is that just because you have an afro?”

Reducing an identity to a hair type exemplifies why the Afro-Latinx community struggles with their identity. What Hollywood said demonstrated the common misperception that someone can only a singular racial or cultural identity, which for people like La Negra and Rodrigues De La Rosa is not the case. Immediately after the conversation aired, social media feeds were filled with discussions about what it meant to be Afro-Latinx.

“It’s annoying the fact I feel I always have to defend myself. Defend my race, defend my looks, defend my fro… so if I want to wear it a certain type of way that shouldn’t affect who I am as a person or my music,” La Negra said at the reunion episode.

youtube

The type of representation La Negra is bringing for Afro-Latinx women was totally absent from Rodrigues De La Rosa’s childhood. Growing up, she remembers watching telenovelas on TLN. In all the Spanish-language dramas she watched as a child, she doesn’t remember seeing a single Black actor. Celebs like La Negra are changing that.

“What Amara’s trying to do is, she trying to show that’s there are all types of Latino women, she’s showing the darkest shade,” says Rodrigues De La Rosa.

What’s in a name?

With her newfound sense of identity, Rodrigues De La Rosa is now confident in herself to identify as both Black and Latina—and sets people straight when they question her background.

“Now when I say a sentence in Spanish and people be like ‘Oh my God you speak Spanish? I thought you were Black!’ I don’t find it surprising, I find it ignorant. I choose to enlighten them,” she says.

Her struggle with identity has become less about unlearning her internalized anti-Black racism, and more about educating others every time they question her ethnicity or race. Rodrigues De La Rosa will probably always face questions from people who don’t understand intersectional identities. But that doesn’t stop her from letting them know she exists, and so does the Afro-Latinx community.

Related:

I Can’t Stop Thinking About Ellen Asking Constance Wu “Where Are You From?”

Could a DNA Test *Really* Help Me Figure Out My Biracial Identity?

Anyone Can Participate in Caribana, and Maybe That’s a Problem

The post For the Longest Time, I Didn’t Identify as Black appeared first on Flare.

For the Longest Time, I Didn’t Identify as Black published first on https://wholesalescarvescity.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

For the Longest Time, I Didn’t Identify as Black

Pollyanna Rodrigues De La Rosa, who only recently began identifying as Afro-Latina (Photo: Roberto Caruso)

Pollyanna Rodrigues De La Rosa sat in the back of a cab, on her way to her favourite Toronto Latin music club, El Rancho. To get herself in the mood for a Saturday night of salsa, bachata and reggaeton, she asked the driver for the auxiliary cord to play “Eres Mia” by Romeo Santos from her phone. The music filled the cab and she sang along, the lyrics flowing smoothly off her tongue in Spanish, the language she speaks at home with her family. The driver raised his voice over the music and asked Rodrigues De La Rosa about her background—but her answer wasn’t what he was expecting.

“I thought you were Black!” he said. Rodrigues De La Rosa, who is part Cuban and part Panamanian, is used to this type of reaction. She stands at just over five feet tall, with big, long, black curly hair. Her dark skin matches her brown eyes, and if you saw her on the street you’d probably have no doubts about her racial identity, either.

But what the cab driver didn’t understand was that while she is indeed Black, she is also Latina. To be fair, Rodrigues De La Rosa didn’t always understand the nuances of her racial identity, either. “For the longest time, I actually didn’t know I was Black,” she says. That’s because, growing up, her family considered themselves Latino.

Though they shared the same skin tone and hair texture, her family never talked about their African heritage—in fact, they preferred to pretend it didn’t exist. Rodrigues De La Rosa’s mother even pressed her about her romantic choices, questioning why she dated Black men instead of white men. And the anti-Black racism was present in her extended family, too. When she visited Cuba in 2015, many of her family members would ask her to straighten her hair for a “better” look.

Between her family’s Latino identity and the anti-Black rhetoric she internalized, Rodrigues De La Rosa questioned whether or not she identified as Black.

Then, in 2015, she discovered a term on social media that she truly felt described her: Afro-Latina. The broad definition is simple—someone who identifies as Afro-Latina, Afro-Latino or the more inclusive and gender-neutral Afro-Latinx is Black and from Latin America. But the term’s meaning is much more political.

In these communities, which have a deep history of anti-Black racism, Afro-Latinx refers to “someone [from the Latino community] who reclaims their Africanness and Blackness, which for so many years was erased,” explains Columbian-Canadian academic Andrea Vasquez Jimenez, the co-director of the Latinx, Afro-Latin-America, Abya Yala Education Network (LAEN). “Utilizing terms such as Hispanic erases our Blackness.”

While Rodrigues De La Rosa may have felt like she stood out among her peers, she is actually part of a large cultural community. A quarter of the Hispanic population in the U.S. identifies as Afro-Latino according to a 2014 study. (Similar data is not available in Canada in part because though the census includes Black and Latin American as visible minority categories, there is no category combining the two identities. Respondents can write in their own classification, or mark all the categories that apply, but the data is counted towards the Black and Latin American categories separately.)

“I get looked at all the time when I start speaking Spanish. It’s still a culture shock, especially to old farts. I quickly let them know that there are Black people in [Cuba and Panama],” says Rodrigues De La Rosa, adding that people often seem to think that it’s impossible to be both Black and a Spanish-speaking Latina.

“When I heard the term Afro-Latina, as sad as this is going to sound, it was the first time I thought I was considered Black,” says Rodrigues De La Rosa. “I loved it.”

Unlearning anti-Black racism as an Afro-Latina

People like Rodrigues De La Rosa are why Jimenez started LAEN. She made sure the organization was a space for Afro-Latinx people to not only have a voice, but learn about their heritage.

“Blackness is global. An extremely high percentage of [people from Latin America] have African ancestry. The identities of Blackness, Africanness and being Latinx are not mutually exclusive,” says Jimenez.

The African diaspora originated with the transatlantic slave trade, when European colonizers dispersed millions of people from Africa to North America, South America and the Caribbean. And regardless of where slaves were taken, sexual violence was common. “This is the most f-cked up part, I don’t know if my Spanish ancestor loved my great-great-great-grandma or raped her,” says Rodrigues De La Rosa.

The intersectionality of Afro-Latinx people can get even more complex, especially for people like CityNews reporter Ginella Massa, who wears a hijab and is from Panama.

“Often, in the realm of my work, my Muslim identity is discussed; my ethnicity or my heritage are rarely ever mentioned,” says Massa. When she made headlines in 2016 for being the first hijabi news anchor, the coverage described her as a Muslim Canadian, but the Afro-Latinx aspect of her identity took a back seat.

CityNews reporter Ginella Massa

Even within Canadian Afro-Latinx communities, positive discussions about embracing all aspects of this intersectional identity are rare.

“Because of anti-Black racism, many folks don’t necessarily speak nor highlight our Blackness within families,” says Jimenez.

That’s especially true among older generations of Afro-Latinx people, who have internalized centuries of institutionalized anti-Black racism. Massa says her family’s Blackness was rarely discussed at home. Her family only focused on their Latin heritage.

“My grandmother, I can say this certainty, would never identify as Black,” says Massa. “I’m not sure where she got this from because to look at her, you would say she is a Black woman. But there is this obsession with light skin and desire to distance ourselves from Blackness.”

For Rodrigues De La Rosa, learning the term Afro-Latina was the catalyst that allowed her to understand her who she really was. She was tired of people constantly denying her parts of her heritage—but in embracing this term, she also had to go through a process of unlearning the anti-Black racism rooted in her community.

As she learned more, Rodrigues De La Rosa also tried teaching her family about their Afro-Latinx history. But it was challenging, especially since her mother, who grew up in Cuba, was ridiculed by other Cubans for her darker skin and tightly coiled hair.

“I’ve had to teach my mother to love herself more,” she says.

Amara La Negra and Afro-Latina celebs stepping into the spotlight

Celebrities such as Jennifer Lopez, Gina Rodriguez, and Camila Cabello are readily identified as representations of the Latinx community in Hollywood—yet celebs like Zoe Saldana, Orange is the New Black‘s Dascha Polanco and Cardi B are often denied their intersectional identity and instead solely seen as Black.

Earlier this year, reality TV star and singer Amara La Negra, whose parents are from the Dominican Republic, reignited the conversation about Afro-Latinx identity on Love and Hip Hop Miami. In the debut episode, La Negra and producer Young Hollywood were discussing ideas about how she should change her image to better promote her music. La Negra insisted her look represented her Afro-Latina heritage. In response, Hollywood proceeded to question her identity by asking, “Hold on! Afro-Latina? Elaborate, are you African or is that just because you have an afro?”

Reducing an identity to a hair type exemplifies why the Afro-Latinx community struggles with their identity. What Hollywood said demonstrated the common misperception that someone can only a singular racial or cultural identity, which for people like La Negra and Rodrigues De La Rosa is not the case. Immediately after the conversation aired, social media feeds were filled with discussions about what it meant to be Afro-Latinx.

“It’s annoying the fact I feel I always have to defend myself. Defend my race, defend my looks, defend my fro… so if I want to wear it a certain type of way that shouldn’t affect who I am as a person or my music,” La Negra said at the reunion episode.

youtube

The type of representation La Negra is bringing for Afro-Latinx women was totally absent from Rodrigues De La Rosa’s childhood. Growing up, she remembers watching telenovelas on TLN. In all the Spanish-language dramas she watched as a child, she doesn’t remember seeing a single Black actor. Celebs like La Negra are changing that.

“What Amara’s trying to do is, she trying to show that’s there are all types of Latino women, she’s showing the darkest shade,” says Rodrigues De La Rosa.

What’s in a name?

With her newfound sense of identity, Rodrigues De La Rosa is now confident in herself to identify as both Black and Latina—and sets people straight when they question her background.

“Now when I say a sentence in Spanish and people be like ‘Oh my God you speak Spanish? I thought you were Black!’ I don’t find it surprising, I find it ignorant. I choose to enlighten them,” she says.

Her struggle with identity has become less about unlearning her internalized anti-Black racism, and more about educating others every time they question her ethnicity or race. Rodrigues De La Rosa will probably always face questions from people who don’t understand intersectional identities. But that doesn’t stop her from letting them know she exists, and so does the Afro-Latinx community.

Related:

I Can’t Stop Thinking About Ellen Asking Constance Wu “Where Are You From?”

Could a DNA Test *Really* Help Me Figure Out My Biracial Identity?

Anyone Can Participate in Caribana, and Maybe That’s a Problem

The post For the Longest Time, I Didn’t Identify as Black appeared first on Flare.

For the Longest Time, I Didn’t Identify as Black published first on https://wholesalescarvescity.tumblr.com/

0 notes