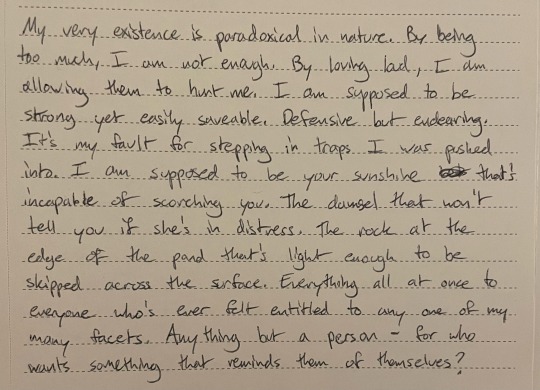

#that monologue it just…put so many abstract thoughts and feelings into concrete words

Text

I wrote this on February 16th of this year. it reads like an extension of the Gloria monologue in Barbie. Greta gets it.

#that monologue it just…put so many abstract thoughts and feelings into concrete words#and america ferrera fucking killed it#bri speaks#barbie 2023

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Telling Stories Through Patience and Implication: More Showing, Less Telling

Sometimes I get asked by other writers how to make their scenes and writing more immersive, like how to influence readers to experience that “I feel like I’m right in the scene, or the room with these characters, and I’m crying” kind of reaction to their words. I had an idea on the way home from taking my kid to preschool today and thought I’d make it into an advice post: on how to use more ACTION and DESCRIPTION of object and place in our writing, instead of relying too much on interior monologue when telling stories. I also thought it would be useful to talk about forcing patience (for yourself and for your reader), and also using implication rather than purely narration to both push the story forward and to stimulate climactic, emotional moments and/or reveals. This is a little long! But if you’re so inclined, I hope it helps!!

Why is using too much interior monologue ineffectual in telling stories?

One thing I’ve learned over many many years of reading and writing and also teaching reading and writing is that there is a HUGE distinction between the inclination to tell stories through telling and then the inclination to tell stories through showing. The “telling” way, which is often funneled through a close third or first person POV and manifests as a list and/or series of interior thoughts and abstract perception is something that we, as writers, often start off doing. This is because choosing to write is largely choosing to put a part of your inner self on the page, and the easiest, most obvious way to do that is by narrating interior monologue. It looks something like this:

She felt pain. Real pain. Pain for the first time. And hunger. Like she was falling through a glass plate and never hitting the ground, falling so fast, and she wanted to land, but there was nowhere to fall to, and so she just kept wanting. And wanting. And her heart felt forever wound into the threads of time and imagination. She was helpless to his touch, and yet she hated everything about it, because it was old. So she just kept falling, hoping maybe somewhere there would be a surface for her to land.

There is nothing wrong with this “interiority” type of writing. It can often be quite beautiful and imaginative. As long as it is not the only or super dominant type of writing in a story. This type of writing is very “telling.” It’s explaining the meaning and feelings of a character’s mind, as well as the themes of the story, to the readers in a somewhat unfiltered way. But note that it’s also very far up in the writer’s head, and because it is so abstract, this type of writing all by itself actually cancels immersion for most readers. It is like floating in a sea of feelings, which might be interesting at first, especially if the prose is beautiful, but after a while, you get tired as the reader, and you find yourself searching for a lifeboat. This type of writing is often found scattered in with dialogue in scenes as well--replacing action and description, and it’s sometimes italicized to indicate that it is an “inner thought” of the POV character.

So what is the opposite of this? Well, the opposite would be pure showing, ie: using description of action and object only to imply emotion and idea (rather than simply telling emotion and idea):

She went to the bathroom, and when she got back, she sat down at her desk. The room was warm. She stared at the picture frame he had purchased for her at a truck stop in Missoula, Montana five years before. She had never put anything in the picture frame. It was still the same smiling people from the stock photo provided by the manufacturer. A long time ago, they had used to go paddling down the Clark Fork river and then tie the canoe to a sturdy root in the bank and hold hands on the shore. Now, he had not held her hand in many months. She picked up the picture frame and then she placed it in a drawer, and then she got up to dust the curtains.

The above type of writing communicates a similar sense of sadness and unclear emotion over a relationship that seems to have changed or died, but that emotional message is communicated through a kind of literal stoicism: actions and descriptions of objects, not the character’s interior monologue. It is not as overtly emotional, but this type of writing is a very effective tool, because it puts things in the scene, creates actions for the characters to undertake, sets up choices that affect the physical world, and attends to setting as well as exposition and character code. It puts your reader in a concrete place, too, a lifeboat, so to speak, giving them actual information to process. It is a break from the effusive emotion we see in the first example, balancing said effusion with stoic and solid objects in the world.

A (Brief) Case for Why We Should All Read Hemingway

Note that most writing has a combination of both of these things--the interior and the exterior. But some writers avoid interior monologue altogether, or reserve it only for VERY important moments. Many of them are short story writers of the modern tradition of Realism, ie: Ernest Hemingway and his many acolytes of the 1970s and 80s--Ray Carver, Ann Beattie, Joy Williams, etc. Even if you hate this sort of writing, it is worth studying. Why?

Many writers, particularly young writers, I find, eschew writing like Hemingway’s as stilted and boring, and in truth, I did not fully appreciate Hemingway till I was in my late twenties (I’m “old” lol). But I think the reason we reject Hemingway is because it is just...so different from what we’re used to. It demands a great deal of us, the reader, and it never EVER tells us what to think, what to feel, or what the characters are thinking or feeling. Instead, it communicates ALL of this through pure description of action, object, and setting. When you learn how to read Hemingway effectively, even if you still don’t love it, you will see that he is an excellent teacher when it comes to using ONLY action and description to communicate messages about emotion and theme. This is a valuable skill in terms of taking steps toward immersion in your writing and creating concrete settings and pictures for your reader to experience. His writing is very stylized but also very stoic in this way, and it is my experience that a great deal of writing these days could use a bit more stoicism and a bit less effusion, because it is robust ACTION and DESCRIPTION that immerses readers in scenes and settings the most--not soft and abstract interiority and feelings alone.

How Implication Works in Writing, ie: Make Your Readers WORK

The word implication here just literally means “implied meaning.” When I’m teaching, one of the most tell-tale qualities that I look for in a writer’s work is whether they rely too much on overt, over-explained meaning and theme via interiority and narration, or whether they use some form of implication in their writing: do they IMPLY their themes through action and description in the story, attend to both setting and process writing, and do they allow their characters to make choices and their reader to do a little work. The latter style usually indicates a writer that is somewhat more mature in their craft. They have read more and understand the importance of setting and action in fiction. They take their cues from books, not movies and TV. But even if you read a LOT, it’s really difficult and takes a long time to get out of your own head as a writer, and to acknowledge that the most important thing in terms of pushing any story forward is action, not thought or narration, and the most important trait in terms of immersing your reader in any scene or situation is through description of action, description of setting, and description of process (ie: giving your characters something to do).

A common problem I see when teaching writing is the tendency to hand readers everything on a silver platter through the narration of the story: here is what the character is feeling, and here is what the story is about. This is usually handled in the most overt, effusive way possible, and very poetically in very poetic prose. It is also a tendency related to the tradition of “voiceover,” a product of film and TV. But the thing is, much of this is really the writer making notes for themselves, often overcompensating for their failure or unwillingness to imply these ideas earlier or later through more successful means. However, as we grow as writers--by reading more, writing more, and learning over time--we slowly start to realize that readers are independent factions, and they have agency, and they are privy to MUCH more than we realize. They want to see characters doing concrete things in a concrete place, not just read their thoughts all the time. So it’s okay to allow the reader to do a little bit of work, to keep some or much of your meaning and messaging implied, and to allow your ideas to build and unfold overtime, through action and description. When writing, it is very difficult to avoid saying exactly the thing you want to say, and saying it as soon as possible. But as with everything, in writing, patience is a virtue, and it is a skill acquired over time.

An Example in a Song

The thing that drove me to make this post in the first place, while I was driving home from my kid’s preschool this morning, was actually a song. It came on Spotify, and I had not heard it in some time, but I have always thought that, in terms of stories, it is one of the best songs there is. The song is “Making Pies” by the folk singer Patty Griffin. In this song, there is very little interiority and literally zero effusiveness in terms of communicating or expressing emotion. It is tightly held, and its stoicism, in and of itself, is a part of the story it is trying to tell. Even its title is a concrete action: Making Pies. The best thing about this song is its patience in telling the story, and how it also demands patience in its listener.

Here is the song (youtube | spotify), and here are the lyrics. If you read and listen closely, especially the second time through, you’ll see just how long it takes Griffin to get the actual crux of the story, and even then, all is done through implication. Examples: In the first verse, she asks: “Did I show you this picture of my nephew taken at his big birthday surprise, at my sister’s house last Sunday?” This question is our first major clue into the narrator’s life: she has no children of her own, and she probably lives close to the place where she grew up. This, all by itself, is not a big deal, but as the song unfolds, more and more details begin to arise, cluing us into her sadness and sense of isolation and resignation: the constant, monotone repetition of “making pies,” the walking to work, the graying hair, the fact that she types for the local pastor on Thursdays, as it is an excuse to leave the house, her somewhat cynical, but ultimately resigned relationship to her religion, via her description of Jesus on the wall. All of these things show us SO MUCH about this character. We can feel her very distinct and specific sadness, even as she never ONCE tells us how she feels.

The first REAL clue that we get about her life and the story comes at the end of the second verse: “Did I show you this picture of my sweetheart, taken of us before the war? Of the Greek and his Italian girl, one Sunday at the shore.” This is a huge reveal, done through an action (not a thought): the showing and description of a photograph. We learn so much in the ensuing four lines, which are entirely descriptions of action and place:

We tied our ribbons to the fire escape

They were taken by the birds

Who flew home to the country

As the bombs rained on the world

Once this happens, we know. We now know everything there is to know, because we’ve been set up that way. This is the entire story, right here, and not ONCE does the narrator ACTUALLY “tell” us what happened. She does not say, “The only man I’ve ever loved died in the war, and now my life is an ongoing loop of resignation, quiet bitterness, and depression.” All of this she IMPLIES to us, through description of action (walking to work, making pies, typing for Father Mike on Thursdays, repeat) as well as description of objects (hair color, photographs, Jesus on the wall, the birds, the bombs). This song is beautifully sad and highly immersive in its storytelling. The reason for that is, it uses patience and subtle clues through action and description to tempt the audience forth, and then it uses more pointed clues through action and description to make its final reveal--but it takes a long time to get there. In this sense, the pay-off is immense, and it is an incredibly effective song. We aren’t just hearing about her feelings. We’re seeing what happened and experiencing those feelings for ourselves.

A slight tangent, but still related: One of the hugest problems I see with lots of current writing, particularly in how it manifests in the modern Hollywood filmmaking tradition, is that there is literally no patience anymore, anywhere. The “hook and snare” is all that matters. Modern dramatic television shows explain their entire thematic purpose via voiceover in the very first scene of the very first episode of the series. Modern action movies spend no time establishing character or contextual lens, and instead dive straight into violence and speed. Nobody trusts their audience. Nobody has any patience. Quietly terrifying blockbuster movies like Alien (1979), which unfold slowly over time, relying on character code, dramatic irony, and careful suspense are now incredibly rare outside the art house. Instead, we are hit with a barrage of color and animation. All messaging is linked directly to the surface level. Characters are stock, cliche, and/or one-dimensional in scope. And too many writers, as they are highly entrenched in the visual media culture of the day, are using these same cues in their fiction: tell the reader exactly what to feel, when to feel it, and how, instead of allowing for patience, build, and reveal, which allows the readers to figure through and come to the emotional climax by themselves. It is the latter that results in immersion.

Conclusion

Why do we love the stories that we love? I will use some modern video games that I love to show that, yes, even in visual media, incredible storytelling through implication exists. Games like The Last of Us and Red Dead Redemption 2 employ all facets of setting, character code, and action to tell their stories. They are often maddening, because we, the player, can often see what is coming, though by the time we realize, it’s usually far too late, and we can only watch it come to a boil, just beneath the surface, unable to do anything about it. We are controlling characters who, thrown into action, decision-making, consequences, and often fear for their lives, simply do not see what we see. We watch them make mistakes, and watch these mistakes unfold, manifesting in ways we could not have foreseen, and sometimes not for dozens of hours of gameplay. HUGE moments in these games, like Joel and Ellie’s reunion at the end of the Winter chapter of The Last of Us, or Arthur’s iconic “I’m afraid” line at the train station with Sister Calderon toward the end of Chapter 6 in Red Dead Redemption 2 are not contrived through overt telling and explanation of theme and emotion in the narration of the game. They are earned as longterm, complicated results of many, many actions and interactions that have lead up to these very poignant, very emotional and climactic moments in the story. The themes of the story are not only and overtly told by the characters, or by a narrator, or through voiceover. They are also shown (or reflected) through the setting--the way it looks, the atmosphere, how it changes over time, through the individual quests, how they look, and the types of choices they force the characters to make.

In this sense, patience and implication are the keys to stories that infuriate us with immersion and make us cry. If you want to slow down a moment, or a scene, or you want to hit your reader over the head with an emotional reveal, focus on earning that moment, scene, or reveal over time, and through much more than simple interior monologue of characters. Use the setting, use action and process writing to communicate your characters feelings and thoughts and the themes of your writing, and to simply anchor your readers in a PLACE. You can STILL use interior monologue, but balance it--with concrete stuff in the world, concrete actions, and concrete choices for your characters to make. Remember, the key to immersion is NOT to tell the reader to be immersed by relying only on beautiful language and narration of thought, feeling, and idea. It is to actually put them in the concrete world you’ve made, and to have them experience those thoughts, feelings, and ideas organically, for themselves.

174 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The smoke settles to reveal LEE JIEUN, also known as ODESSA or SAGE, a 23 year old witch of Sunseong. She is a part-time florist and part-time psychic who appears to be adept in divination and herbology --- but like most things in Sunseong, there must be more to her than meets the eye.

FACECLAIM: Lee Jieun (IU), soloist

BIOGRAPHY:

Jieun, known as Sage to her Blossoms customers and Odessa to those looking for a psychic, was born in mid-May. Her mother was a single parent, struggling just to support herself. To her, Jieun was another burden she was not ready to take on. Hazy memories of a beautiful but worn woman fill Jieun’s mind when she thinks back on her mother. Jieun was three when she was taken.

Her mother had been a witch. Jieun’s father had left her with child when he discovered this. Disgusted, he disappeared without a trace before Jieun was born. After Jieun was born, her mother struggled to make ends meet and provide for the two of them. She turned more ardently towards the pursuit of magical knowledge, looking for a way to save herself and her child. Slowly she began to isolate herself from her coven. Then from their neighbors. Then, she stopped going to work. Finally, her mother cut herself off from Jieun, who was forced to feed herself and her mother on the donations of neighbors who saw her and recognized her plight. Perhaps it was fortunate, then, that an older woman down the street noticed Jieun. Fortunate, that she realized what was going on behind their apartment doors, even though Jieun did not. But, perhaps, also, it was unfortunate. For Jieun screamed and cried as, at three years old, two young men dragged her away from her home on the instructions of the old lady down the street. Unfortunate, as Jieun watched men and women beat her mother into submission because she was no longer a witch, watched as her mother was labeled ‘warlock’ and was separated from her forever.

Jieun, who no longer had a place to call home, would call it unfortunate for many years. Others would whisper how lucky she was when they thought she couldn’t hear or wouldn’t understand. She was ushered from home to home when someone could take her in, but the bond between witches in generally weak and she spent more nights in shelters than she did in homes. She found herself spending days in gardens, looking at flowers and bugs instead of reading the books that should have taught her instead. Jieun found that tea filled her belly better than water and that at least after she was done drinking tea, she could pretend she could predict her future in the dredges to help her ignore the pangs of hunger.

What was fortunate was the day that same old woman found her again, booked her on a train to Europe, and saw her fed and taught. After all, the child of a witch is said to be more precocious and more inherently magical. In an apartment on the outskirts of Paris, Jieun found herself alone, but for the first time in ten year, happy. It seemed that her years of make-believe had helped her develop a keen eye for divination and herbology. When applied and focused, she was quite good at both (and crafting potions). She had modest abilities in other areas; nothing to brag about, but she found success when she took her time, drained though she would be. But, times came when she was lonelier than she knew how to put into words. Happier, but lonelier. That was when she met Peppo.

Or rather, she summoned him. She was nearly twenty when she was preparing to leave Yonerra, the school she had learned to call home. For years, she had tried to summon a familiar of her own. Most of her classmates had accomplished it and had the most spectacular animals to call theirs. She, on the other hand, was preparing to leave the few friends she had ever had to return to an unimaginable life. Old enough now to be on her own, but still very much a stranger to her homeland. She had not been there in seven years. It was then, as she shut the door on her apartment for the last time that she heard the soft padding of footsteps behind her. He was not but a kitten, small, and light gray with black stripes. He asked if she was Jieun and after stowing him in her purse, they made their way through the countryside of Europe and Asia where Jieun caught a plane from Shanghai to South Korea.

CHARACTERIZATION:

-optimistic- a strange trait for a girl who grew up so negative. In her younger years, Jieun could never have been characterized as ‘optimistic’ but now it would be hard to call her anything else. Whether genuine or faked, is never entirely clear. But, she has a relentless optimism that is both infectious and utterly infuriating.

-introverted- her preference, molded from years of solitude, is be alone. Other than Peppo, Jieun couldn’t care less to have company or to spend her days around people. Not that she particularly dislikes being around people, she just does not actively seek it out. Especially since her distasteful abilities mean she is safer alone and aloof.

-awkward- Jieun is not particularly adept in social situations. Rather, she tends to stutter and fall over her words quite easily. This is exasperated when she is flustered, often because she is caught doing she shouldn’t do (like bringing Peppo basically anywhere) or something embarrassing. She is particularly embarrassed when customers from one of her jobs meets her at her other.

-domestic- the type to sit home and cook herbal meals for her friends that will magically improve their health, or sew minor wards into the linings of gifts. She has a rather extensive herbal garden on her balcony and a plethora of spell books with different specialties to help her perform spells outside of her natural talents. Her favorite spell book lays open on her desk most of the time.

-messy- domestic though she may be, she is not organized. Rather, her apartment is more often an array of clothes, herbs, books, and papers strewn about her tables and floors. Many of her wooden furniture are covered in carvings of different sigils to help Jieun remember the most important ones, though she does mix them up more often than not.

-library-addict- the atmosphere reminds her so strongly of Yonerra, that she finds herself often gravitationally pulled towards them. If she is not at work or her apartment, it would not be odd to find her at the library closest to her house, or the one closest to Blossoms (thought she prefers the one near Blossoms because it has a nice section that is hidden from view where no one will see Peppo, or her practicing magic).

-hopeless romantic- Since she was little, Jieun has dreamed of meeting ‘the one’ who would accept her despite her flaws and magical abilities. As a result, she has watched a few too many k-dramas and romance animes and has set herself up for unachievable standards. Worse still, is the fact that Jieun has never dated so her expectations have never been set straight.

-dramatic- particularly when it comes to love, Jieun has a tendency to be overly dramatic because she believes this will give her the life she wants and make people like her, even though it tends to do the opposite.

SPECIALTIES:

-divination (rank II): Jieun is particularly talented when it comes to divination, but her specialization within this field is reading tea leaves. However, she has found success with crystal balls as well and has managed to open her mind to such a level that on occasion she will receive random, unprompted visions. These she may or may not be conscious of. When she is unconscious during her visions, they are often conveyed through a long monologue, though these spiels are uncommon for her. In fact, it is generally rare for her to receive random visions at all and they are normally triggered by something and cause her to feel exhausted afterwards. She is fairly good at interpreting stars and constellations as well as dreams, but when she wants more concrete rather than abstract fortune-telling through these means, it involves a much longer and more complicated process that is highly draining. As a result, she sticks almost solely to tea leaves and crystal balls, dabbling in smoke reading when requested by a customer.

-herbology & potion crafting (rank II): Jieun is particularly gifted at identifying and growing medicinal and magical herbs. As a result of this natural gift, she spent much of her time at school practicing her potion making so that these skills would be more ‘marketable’ and helpful. She is particularly skilled at making healing and medicinal potions, as this is an area she concentrated on quite fervently. She is dreadful at making love potions, but can adequately make any other potion someone may request of her.

-animal familiar (rank I): Jieun is not super great at conjuration and she can only ‘conjure’ Peppo. However, she has a close bond with Peppo, her familiar, which allows her to decipher his meows as if he were speaking Korean. He understands her when she speaks Korean to him as well.

1 note

·

View note