#that's too Frankensteiny even for me

Text

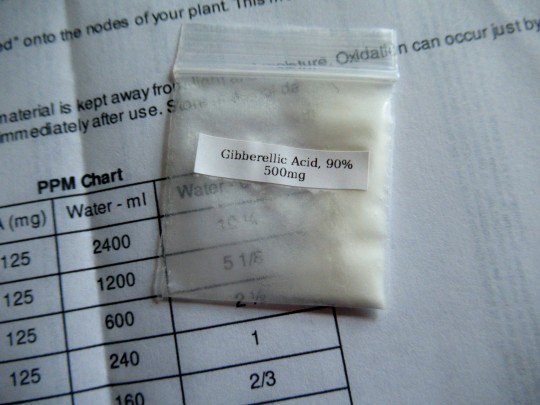

I'm officially about to enter the Frankenstein stage of gardening.

#this is a plant growth regulator#I'm going to use it to try to get better germination on some very dormant seeds#Galeopsis speciosa/large-flowered hemp nettle#I've had two plants succeed and the rest of the seed just lies there#waiting for some secret sign from god that is yet to arrive#thus I am compelled to interfere in nature's clockwork#however I draw the line at grafting#that's too Frankensteiny even for me

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

how do write so consistently and so often? i'm often swamped with work and when i finally have time to write, i'm too emotionally tired/anxious that it isn't good enough, so i go blank! any advice?

I’m about the worst person in the world to answer this lol

I think everyone has their own method and you just have to sort of...tailor it to fit your situation and your own personal writing habits. I tend to write very quickly when I get down to it, *if* the spark is flaring and words are wording. Which isn’t always.

I guess the key would be to just do it when you can? I have the benefit of not having a terribly strict schedule to adhere to, which admittedly makes it easier to find bits of time here and there to sit down and bang a few lines out whenever they come to me, but during the school year that gets a little harder because I homeschool two boys - one in elementary with severe ADHD and one in junior high with special needs - and that gets spread out across the entire day and sometimes into the evening. So I write little bits throughout the day, and then any serious writing that gets done usually happens late at night after everyone else has gone to bed. Your writing doesn’t have to be done all at once, and it’s sometimes better to have little pieces to string together later. It seems like sometimes the cobbled-together frankensteiny stuff ends up working out the best.

About that “anxious that it isn’t good enough” part - we all get that, trust me. I have 7 published books and 74 works on AO3 and I still have overwhelming anxiety when it’s time to share. It’s just something that you have to work around, and remember that it’s almost always better than your anxiety tells you it is :)

@pipingplover (it’s not letting me tag you, sorry - hope you see this!)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Those Who Remain review – a torturous exercise in mediocrity • Eurogamer.net

I almost gave up on Those Who Remain halfway through. It was the lions, you see. A first-person blunderfest for horror obsessives only, the game’s setting is split between a menacing night-time reality and a weed-choked, oceanic otherworld in which objects float and the puzzles are more, well, videogamey. One such puzzle is a labyrinth dotted with lion statues. The idea is to carry the statues to candlelit plinths. The problem is that there’s a monster in your path, an oily personification of buried guilt and suffering. There’s a lot of that kind of thing in Those Who Remain – accusing messages on walls, silver-masked demons chortling about sin and forgiveness – but for the most part, the emotions you’re repressing are boredom and frustration.

The main character has no means of defending himself, so you must take winding routes to those plinths while lugging chunks of Umbrella Mansion Surplus stoneware that prevent you from sprinting, block the view and have a habit of jumping out of your hands. These burdens create tension, of course, but only for the few seconds it takes you to realise that you’re playing a mandatory-stealth McGuffin-fetching puzzle with instadeath. After my eighth try I decided that life was too short. But I came back the next morning and beat the area, thanks partly to bloody-mindedness and partly (I speculate) to a developer update that prevents the monster from chasing you endlessly once alerted. Let me tell you: I wish I’d stopped at the lions.

Those Who Remain does have some neat ideas, but all of them are squashed beneath a great steaming heap of mediocrity. The premise is Silent Hill as rewritten by an Alan Wake who has run out of coffee, and possibly self-respect. Leading man Edward is drinking and monologuing himself into an early grave over the loss of his family, as leading men in horror games often do. As the curtain goes up, he’s driven to a motel to break off a torrid affair, only for somebody (Wake?) to steal his car and maroon him outside Dormont – a spookily abandoned, predictably metaphysical town whose shadows are filled with knife-wielding spectres, their eyes flickering in the depths of closets and cornfields. Turn on a light and the spectres vanish, rendering the area safe for traversal.

The immediate question is: why not carry a light source with you? And Edward does – for the first few minutes, brandishing a cigarette lighter as he hurries after his car. But he soon loses the lighter and declines to replace it, even as the game’s tedious psychodrama drags you to malls, toolsheds and police stations filled with, at the very least, burning chair-legs and candles. There’s something loveable about this unwillingness to spoil the game’s core concept. It fills me with nostalgia for those perversely specific lock-and-key puzzles in older Silent Hills. And the spectres are eerie enough to begin with, especially when encountered inside. One dependable source of heeby-jeebies is reaching around a door frame to flip a light switch, inches from death.

The fear lies partly with how the spectres turn Those Who Remain’s shortage of actual character animations into an advantage, and partly with the sense that they are still there when the lights are on – that you are walking through them, kept from their blades by a single parameter in a game where objects occasionally glitch themselves invisible. But that fear soon turns to familiarity and – when you’re scratching your head over an obtuse item puzzle – annoyance. I started throwing things at the watchers, trying to recreate the exploit from Skyrim where you could blind shopkeepers to your thievery by putting baskets over their heads. Even disregarding the point about mobile light sources, the perils of darkness are inconsistently applied: there are pools of deep shadow in the game that are somehow safe to walk through, which means that you always think of the light/dark conceit as a designer’s gimmick.

Still, all that’s small potatoes next to the irritation conjured by the game’s handful of mobile threats. These include a Frankensteiny blur of body parts with a searchlight for a face, whose approach is heralded by the dopplering wail of an ambulance siren. The Frankenstein creature stars in many of the stealth bits, fidgeting around as you try to solve puzzles that take you back and forth across the area. She’s not difficult to avoid, but she’s more of a meddler than an adversary. You kind of wish you could just usher her to a chair and give her a book to read, while you figure things out.

And then there’s the major antagonist of sorts, one of those flapping-head harridans familiar from Jacob’s Ladder who screams and sobs in your ear as you flee down corridors packed with dead ends and moving obstacles. These gauntlet runs throw the game’s lousy checkpointing into sharper relief – die, and you’ll often have to re-complete puzzles and re-experience scares that were pretty unconvincing to begin with.

The areas themselves are charmless and indistinct, not in an exciting, feeling-along-wall-with-danger-nearby way, but in an annoying, stepped-in-dogfood-while-fumbling-for-the-doorhandle way. The game’s buildings are, in theory, iconic chunks of Americana, the kind of thing Remedy revels in, but they all feel interchangeable thanks to furniture-showroom scene composition. The spirit realm is appealing mostly because it’s relatively well-lit, and has a wider colour palette. It’s accessed via magic doors, and creates some fleeting intrigue as you ponder what the differences between realities suggests about the characters and premise.

The puzzles run more of a gamut, quality-wise. Some are inoffensive but insipid, such as turning valves in the right order to activate fire sprinklers and clear a route. Others are slightly more involving. In one later section, the setting flicks rhythmically between realities, giving you a window to hurry past barriers or hazards that don’t exist in the other world. The spirit world conundrums incline towards the goofy – there’s a frightfully unwieldy specimen that has you covering runes with barrels to move blocks around. And some puzzles, like the item hunts, are an absolute chore. At intervals Edward is required to condemn or forgive some local sinner to progress, a series of choices that shapes his own fate. Before you can do this you need to learn everything you can about said unfortunate, which involves picking through dozens of lockers and drawers for backstory documents, often while hiding from Searchlight Lady.

Those Who Remain hints at being a serious exploration of mental illness, but in practice, Edward is just the same old Sad/Mad Dad the horror genre can’t seem to wash its hands of, growling things like “your life feels like a movie” as he lumbers towards the final accounting. The misbehaving men and boys he’s asked to pass judgement on are just as clumsily sketched – I felt nothing towards them, positive or negative. I can’t say the same for the game they’re a part of. If Those Who Remain is a purgatory for wayward souls, its true victim is the player.

from EnterGamingXP https://entergamingxp.com/2020/05/those-who-remain-review-a-torturous-exercise-in-mediocrity-%e2%80%a2-eurogamer-net/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=those-who-remain-review-a-torturous-exercise-in-mediocrity-%25e2%2580%25a2-eurogamer-net

0 notes

Text

Doctor Who Reviews, Season 2, Part 2

Note: These reviews contain many spoilers for season 2 and occasional spoilers for later seasons. There are also a few references to plot points from the classic series.

Rise of the Cybermen: Like “New Earth,” this episode gives us the opportunity to see a different world, although in this case one that aligns quite closely with ours, but it’s again a pretty meager effort—some technology upgrades, some zeppelins in the sky, the end. (The ability to travel between universes is also established in a fairly underwhelming way; there’s a lot of drama about how the TARDIS is dead, and then she isn’t, just a few minutes later, and I don’t know what it means for the Doctor to fix the problem by giving up ten years when he doesn’t generally die of old age.) The low-key approach to world-building might have worked well in service of a more engaging plot, but the Cybermen story never quite finds a way to make the metallic monsters interesting. The first scene at least goes to an entertaining Frankensteiny place, but after that, in spite of his constant references to his impending demise John Lumic just sort of feels like walking exposition, necessary because we need someone who isn’t a Cyberman to explain the plan. I’ve liked Roger Lloyd Pack in other things, but he’s one of the least convincing evil genius figures I’ve seen on this show, and without a charismatic human presence to move their story along, the Cybermen just don’t make enough of an impact—especially since they’re stuck with trying to take over the world via evil earpieces. The scene in which a bunch of homeless men are converted while “The Lion Sleeps Tonight” covers the sound is a brilliant piece of darkness, but the episode never otherwise manages to make them look more than moderately intimidating.

This could have been a disastrous episode if it relied too heavily on the Cybermen narrative, but, fortunately, it devotes a lot of time to Rose’s and Mickey’s parallel world families. It’s a fairly brief scene, but Mickey’s reunion with his grandmother—now dead in our universe—is the clear highlight of the episode, and continues with the work that “School Reunion” did to give Mickey more depth. His interactions with Rickey and his band of revolutionaries are also strong scenes, although while Noel Clarke does a great job as Mickey in this episode, he overacts Ricky to the point where he becomes comedic—it’s unclear whether or not this was intentional. Rose seems to have moved on completely from the abandonment that happened in the previous episode, which is frustrating, but she does have some memorable interactions with the Doctor. The look that she gives him in an attempt to get him to investigate this universe’s Pete and Jackie is the most directly flirtatious behavior that we’ve seen from her, and they are really adorable in their undercover guise as waitstaff at the party. (The Doctor’s reaction to tiny lapdog Rose is especially cute.) Rose’s attempts to get to know this version of her dad are really nicely depicted here, and it’s lovely to see a slightly different version of Pete. I am a bit put off, though, by what this story does to Jackie. It’s a different universe and, therefore, a different version of Jackie, but Mickey treats his grandmother as basically the same person as the one in his universe, and Pete winds up being seen as a substitute for this universe’s Pete, and that makes the portrayal of Jackie seem like a commentary on the main version of this character as well. She has moments of seeming like our Jackie, but her shallowness and snobbery are played up so much here that we’re left with the suggestion that if she were a rich, childless woman instead of a poor single mother, she’d lose all of her good qualities. The whole character just feels like we are being asked to laugh at Jackie by magnifying her flaws, and it seems mean-spirited to me. It also sort of seems like she was written as unlikeable for the purpose of making it easy to get her out of the way so that our Jackie can be with Pete at the end. This does set up a great moment in the finale, but the whole episode plays into the critics who find Jackie shrill and overbearing, and she’s way too good for that.

There is a lot to dislike in this episode, including the lackluster parallel universe, the Cyberman plot, and the treatment of Jackie Tyler. The interactions between Rose and the Doctor help, though, and Mickey and Pete are so good here that they mostly save the episode. I wish it had been linked to a more engaging narrative, but I really appreciate that the show is giving Mickey a lot of good material before (temporarily) writing him off of the show. B-

The Age of Steel: “He takes the living, and turns them into those machines.” “They cut out the one thing that makes them human.” In the Davies era of the show, this is what the Cybermen are. The fact that they were once human is lamented, but there’s definitely nothing human about them anymore. The precise nature of the Cyber identity has been somewhat ambiguous throughout their long history on the show, but this is one of its most disappointing formulations. The notion that Cybermen have had their emotions removed is completely consistent with what we know from the classic series—it’s integral to these monsters that their emotions have been deleted because they see emotion as weakness and uniformity as strength. Ideally, this can provoke interesting questions about what it means to have a human brain (even if it’s been programmed by Cyber control) while the human body and emotions have been replaced. Out of all of Who’s monsters, they are in some respects the closest to us because of this retention of this human brain, and that gives these figures the ability to be truly unsettling and uncanny.

The show’s approach to the Cyber identity has varied a lot over the years. In the classic series, many of the most interesting moments with the Cybermen came in the form of resistance to certain elements of Cyber design and control. “The Tomb of the Cybermen” lets us see a character resist the effects of partial conversion, for instance, while “The Invasion,” (the best Cyberman story) gives us essentially weaponized emotion, in which Cybermen suffer from having emotion gradually re-infused. Once Moffat takes over, human nature becomes tied so closely to the intellect that a Cyberman with a human brain has only had part of its humanity cancelled, which gives us terrifying encounters with machines who are still sort of human. (Granted, it takes him a while to find a logical balance between these elements, but I would say he gets there eventually.) Here, it’s not that humanity is permanently unavailable to these Cybermen, but it’s completely dependent on the fairly straightforward piece of mechanics that is the emotional inhibitor. This device, which appears to be linked to the nervous system, suggests that one’s humanity is entirely dependent on whether or not one’s emotions are physically operational. The Cyberman whose human form was about to get married is heartbreaking, but her humanity is reduced to an on-off switch. Functioning emotional inhibitor=not human. Broken emotional inhibitor=human again. When Tennant says that he gave the Cybermen their souls back by turning their emotions back on, he’s not kidding; the perspective here is genuinely that the soul and emotional experience are completely synonymous.

My issue with this is not so much that it is a dull exploration of what it means to be a Cyberman, and more that it is a dull exploration of what it means to be human. To be fair, emotion is probably our most important characteristic, but reducing the human soul to a question of whether or not your feelings button is turned on makes human nature look one-dimensional—there are lots of things that define our humanity, and feelings are central among them, but they’re not alone. It doesn’t help that the solution to the problem completely undercuts the episode’s apparent message. The Doctor insists that human individuality is important, and that grief, rage, and pain are intrinsic to the human experience. Then, once he returns to the Cybermen their “souls,” they all do basically the same thing, with only very slight variation. This uniform action involves being destroyed by their emotions, including their grief and pain, and while I understand that realizing what you had become could easily kill a person in this situation, it’s a bit odd to have a big speech about grief and pain being qualities that are important to humanity and then follow it by having everyone commit suicide because of these qualities. There’s a really effective shot of a Cyberman looking with horror at its reflection in a mirror, but watching the emotionally-restored Cybermen continue to behave with almost total uniformity and be completely unable to handle negative emotions works so directly against the themes of this episode that I’m just confused about what anyone was thinking when they put together this story. If we’d just had a few outliers—someone saying “I’m in a lot of pain, but at least I can stomp on my enemies now,” or someone determined to hold on to life and consciousness in spite of the reasons to let go of them, or someone trying desperately to call for re-conversion back to full humanity—this would at least let us see what the Doctor is saying about the importance of individuality and emotional experience. Instead, while there is some variation in terms of the gestures that they make, from what I can see they just wander about dying en masse.

Lumic gets even worse in this episode; his interactions with the Cybermen early in the episode are so awkwardly written that they almost seem unscripted. His final showdown with the Doctor is mostly forgettable, even if it does give the Doctor a few good lines. (I particularly liked his sarcastic, ““I’ve been captured, but don’t worry, Rose and Pete are still out there, they can rescue me!”) The Doctor’s speech about the need for grief and pain doesn’t really work well within the Cyberman narrative but is a nice moment in an episode that sees Rose lose Mickey, get rejected by this version of her father, and see the death of this version of her mother. While he’s going on about the human imagination, it’s delightful. He moves pretty quickly into self-satisfaction, though, and he never seems to think through how he might actually convince Lumic, whose death is dull and silly. There’s some fun running around and some entertaining action-movie stuff here, but overall the plot is just completely misguided.

Fortunately, a few characters get such good material that they elevate the episode well above the mediocre Cyberman plot. Mrs. Moore is a terrific character and makes a great temporary companion for the Doctor. In spite of dying pretty quickly, she’s a well-rounded, believable character, and her death seems like a meaningful loss. (I would love it if someday the show let us see the Mrs. Moore equivalent in our universe.) I also continue to enjoy Pete, although the episode kind of wastes the very good idea of having Rose and Pete pretend to be completely emotionless in order to get past the Cybermen in order to rescue Jackie. Watching Rose, by nature a fountain of emotion, fight off the need to express her fear and grief would have made for some excellent drama, but we don’t get to see that because they immediately find out that Jackie has already been converted and then they just stop pretending. Still, I love that Pete has been working as a spy, passing information about Cybus Industries to the Preachers. His final scene, in which he learns that Rose is his daughter from another world but rejects her because he needs to take down the rest of the Cybermen, is beautifully underplayed and really painful to watch, but even that gets overshadowed by Mickey’s decision to stay in the parallel world. This two-parter has maybe slightly overdone the whole “Rose and the Doctor treat Mickey as the tin dog” thing in preparation for this moment, and his magical hacker skills have never seemed plausible to me, but he gets an absolutely marvelous exit. His determination to both take Ricky’s place in fighting the Cybermen and to take care of his Gran is a great motivation for him to leave, and his last conversation with Rose is perfect in its simplicity. “We’ve had a laugh, though, haven’t we—seen it all, been there and back” isn’t the most poetic dialogue the show has ever had, but it’s exactly right for the moment. Then, when Rose and the Doctor have gone so that Rose can go give Jackie a gigantic hug, Mickey gets one more fantastic moment in his confidence that he can take down the Cybermen from a van because he “once saved the universe with a big truck.” Aw, Mickey Smith. You were really boring for a while but you got awesome eventually. B/B-

Idiot’s Lantern: Even if sometimes the stories themselves don’t completely work, Mark Gatiss is generally very good at writing a convincing Victorian-era setting, which is one of the reasons why “The Unquiet Dead” was so enjoyable. His efforts to convey the 1950s are a lot less specific: there’s some period-appropriate clothing and a general sense of patriarchy, and that’s pretty much it. It’s fun to see the Doctor and Rose in fifties garb, and I like that Rose continues to make use of stuff she knows just from being a human with a family—her flag knowledge from Jackie’s sailor boyfriend and her immediate suspicion of the number of televisions because of stories she’s heard from Jackie demonstrate that her human perspective is quite useful. It’s only useful for a brief period of time, though, because she quickly gets her face and brain sucked out and spends much of the episode trapped. (Rose has less than usual to do in this episode, “Fireplace,” and “Love and Monsters,” and I just don’t understand the concept of having Billie Piper on your payroll and not making as much use as possible of her talents.)

The plot, in which the television is sucking out people’s brains, is an overly literal depiction of the fear of technology, and the only really creepy moment is the visual of the faces trapped in TV screens. The Wire is eerie enough when she is keeping up the persona of the television host, but just sounds silly when yelling things like “Hungryyyy!!” or “Feeeed meee!” The domestic disharmony in Tommy’s family isn’t a terrible plot, but the father’s over-the-top performance and the dialogue’s heavy-handedness about how he’s exactly like the fascists he fought against render it pretty forgettable until the last few minutes. Rose’s insistence that Tommy go after his dad, and her wistful look in their direction, give us a nicely underplayed reminder of what she lost in the last episode, which is important in a season that tends to make Rose come across as forgetful. Although, given what we’ve seen of the dad’s temper, I’m a little concerned that she’s sending the kid into a situation where he’s going to be abused. It’s good that she’s still thinking about Pete, but this father seems like a very different model.

It’s the only really memorable piece of an awfully by-the-numbers episode, though, and one of Gatiss’s weakest contributions to the show. In general, I tend to like Gatiss as a writer of (relatively) realistic drama more than I like him as a sci-fi writer; I loved “An Adventure in Space and Time” and consider “The Hounds of Baskerville” to be the most underrated episode of Sherlock (where he’s a fantastic Mycroft), but when he writes for Doctor Who he tends to lean a bit too heavily on B-movie horror tropes. Old-timey, cheesy speculative fiction is an important influence on this show, but I think most of the other writers blend these influences more thoroughly with humor and character-driven drama than Gatiss does, and this episode is one of the most in need of an effort to reinterpret some of its influences in a more imaginative way. What we’re left with isn’t a terrible story, but it’s pretty pointless. C+/C

The Impossible Planet: The first part of this story isn’t quite as exhilarating as the near-perfect second part, but it’s a terrific piece of setup and a marvelous example of how well the Tenth Doctor/Rose pairing can work. A lot of episodes this season are let down by some combination of the setting, the monsters, and the minor characters, but this episode knocks it out of the park in all three respects. For the most part, the setting is ordinary Outer Space done very well—the endless series of sliding doors isn’t especially original, for instance, but it’s used very effectively. At times, though, the setting goes well beyond being a fun, slightly Star Trek-y space and becomes genuinely fascinating. The untranslatable writing immediately lends a compelling sense of mystery, the revelation of the somehow non-deadly black hole is astonishing, and the lost civilization is just gorgeous. The music is perhaps even more important than the visual—it’s lovely throughout the episode, and the brief sequence set to “Bolero” is an especial highlight. The Ood are among the best new monsters of the Davies era; they’ve got a striking appearance, and they create an intriguing perspective on what this future is like. They show not only a dark side of humanity’s future, but also a sense of how humans are attempting to justify that dark side—while it’s ultimately unconvincing, particularly in light of Season 4’s more in-depth look at the Ood, I can fully believe a future society using the idea of a species’ natural subservience as an excuse for exploiting them. Among the minor characters, Scooti is basically canon fodder, Danny is forgettable, and Toby never really interests me other than as a vessel for the Beast, but Ida, Zachary, and Jefferson seem like fully-rounded human beings within seconds.

Rose is just delightful here; she’s having a good time in spite of being trapped extremely far away from the Earth, and she’s trying to connect with the Ood, who remind her of the hopelessness she once felt. She also starts to have a real conversation with the Doctor about the possibility of living together on whatever planet they get dropped off on, and I wouldn’t have any objection to the Doctor/Rose romance if it always looked like this. Their conversation is hesitant and awkward, but it’s really sweet, and I love Rose’s amusement at the thought of the Doctor getting a mortgage. The Doctor himself is at his most jubilant here, and his impulse to hug the captain because of humanity’s obsession with exploration is a particularly nice moment. Everyone is just so loveable here that I spend more time basking in the wonderfulness of the characters and setting than actually taking in much of the plot, but there is some good setup for the next episode, particularly in the moments in which the Beast’s consciousness starts to come through. There’s a fair amount of exposition here, and most of the very best things happen in part two, but this is a glorious start to a terrific story. A/A-

The Satan Pit: This is generally a pretty highly-regarded episode, but I still think it’s massively underrated—I would put it in my top five. While it’s not as emotional as the finale, I would say it’s the best treatment of the Rose/Doctor relationship, and it’s also arguably the most fun episode of the entire reboot.

Both pieces of the story—the Doctor and Ida, Rose and the rest of the crew—work impeccably well on their own and dovetail together nicely. While I think that the Doctor’s adventures are a bit stronger, Rose gets a lot of great scenes with the crew, who continue to be extremely engaging minor characters. The crawling through the tunnels is claustrophobically terrifying, and Jefferson’s death is genuinely really tragic—at this point, it feels like he’s been in the last five episodes at least. The mysterious references to guilt about his wife give him a real sense of depth, and the actor does a stupendous job of making a man who could seem mindlessly violent truly likeable. Zachary is very well-written and acted throughout this episode; he could easily come across as a one-note character, but his capability in spite of guilt and uncertainty comes across very clearly. The script is nicely attentive to the ways in which the power structures in this time and place are allowing some of the problems to happen—I really like the fact that they’re having trouble tracking the Ood because the computer doesn’t register them as life forms. This is also the one episode this season in which I really believe that Rose’s personality has substantially shifted because of her time with the Doctor. She takes control in much the same way that the Doctor would, and she even sort of imitates some of the Doctor’s mannerisms in the way that she talks to the crew. Yes, she is basically suicidal in her attempted insistence on staying to wait for the Doctor instead of fleeing with the rest, but otherwise she is a terrific leader throughout this story.

The Doctor himself gets an even better adventure. His complicated feelings for Rose are woven throughout the narrative in a way that serves the story and their relationship; his initial retreat from the chasm is pretty clearly motivated by his need to get back to Rose, and it’s a beautiful expression of just how much of an impact she has on him. His almost-declaration of love for her, which he declines to actually say, because “Oh, she knows” is also a strong portrayal of the strength of both his feelings and his sense of hesitation. Ida isn’t quite as fully realized a character as Jefferson or Zachary, but she’s likeable and she works well as a foil for the Doctor’s religious musings. The old civilization looks amazing, and the elegiac music that accompanies their exploration of it is just perfect.

The Doctor doesn’t just wander about in this lovely little world, though, because the Beast has directed his attention toward ideas that are fairly unusual for this show. Doctor Who doesn’t often deal with faith in a religious sense—although it will do so much more frequently once Moffat takes over—and the Doctor really seems to struggle to articulate his own here. Early in the episode, he resists the notion that anything could come from before the universe, and the Beast’s response—“Is that your religion?”—seems like a pretty good reading of what the Doctor believes in. What his long run of speeches in the pit shows, though, is that he doesn’t cling to his beliefs, but rather looks for things that will challenge them; he wants to find things that will break the rules that inform his understanding. It’s a fascinating portrait of what faith looks like to him, and it’s entirely believable for someone who has had his lifespan and his adventures. This would have been a worthwhile look at the Doctor’s mind even if it had stopped here, but we also get a lot of attention to what he believes about humans. He is particularly enthusiastic here about human nature and about the specific humans that he encounters, and I especially like his ability to rewrite the Beast���s very negative reading of Rose and the crew in positive terms. He’s aware, though, of human failings as well, which takes its most interesting shape in his argument that humans don’t have an innate need to jump but rather one to fall. The mysterious pit gives him the opportunity to emulate that piece of human nature, and his descent into unmeasurable depths is a wonderful physical rendering of the more spiritual and psychological leaps of faith that he makes elsewhere in the episode.

His most dramatic analysis of humans comes, predictably, in response to the possibility of losing Rose. The entire scene of the Doctor versus the Beast is just splendid in every respect, even if it is sort of an unusual approach for this show to make. Meeting a trapped creature who could be the origin of all of the Satan (and other ultimate evil) myths across the universe is possibly branching out past science fiction into fantasy, and the idea that smashing the urns breaks the prison sounds like something out of a fairytale. The use of the black hole does give the story more of a science fiction basis, but it’s still a very different story from the rest of the season, and one that puts the Doctor in the rare position of coming into the situation with very little relevant knowledge and having to work to piece things together. His conversation with the Beast—who functions more as an inspiration of interesting behavior in other characters than as a compelling focal point himself—is really more of a monologue, but it’s an absolutely sublime one. His joy at gradually putting together the truth plays out beautifully, and his reaction to the thought of losing Rose is an excellent follow-up to his earlier unwillingness to verbalize his feelings. What he says here isn’t exactly a profession of love, but it’s a statement of the nature of his feelings for her: out of all of the universe, and the many wonders he has seen, she is what he has the most faith in. It is a sort of statement of love, rewritten in terms that make sense for a wanderer who is cut off in some ways from normal human experiences. The Doctor burning up a sun to say goodbye to Rose in “Doomsday” might be the popular choice for the most memorable portrayal of their relationship, but his exuberant exclamation of “I believe in her!” is the highlight of the Doctor-Rose pairing for me.

The rest of the scene is lovely as well, again thanks in part to the fantastic musical score. One could find some logical flaws here; the Doctor’s concerns about the rocket losing orbit if he destroys the urns could be satisfied by waiting a reasonable amount of time, until the rocket has had time to get past the gravitational force of the black hole, but this scene is such a burst of goodness that I don’t really care. Rose killing Toby and thereby getting rid of the mind of Satan is nicely in line with the characterization of Rose that appears in this episode, although the “Go to hell” line is a bit overly quippy. The music, the Doctor’s monologue, and Rose’s embrace of her role as hero in what she thinks are her last moments all work perfectly together until the tremendous moment in which the music triumphantly goes “Da-da-dahh!!!” because the Doctor has found the TARDIS. The death of all of the Ood gives a somber note to the otherwise joyous ending, but Zachary’s seriousness toward their deaths—putting all of them into the records individually—creates a sense of hope that this set of humans, at least, might start to recognize the problems with how the Ood race is treated. To be sure, using the TARDIS as a tow truck is a bit odd, but the universe has rarely looked more beautiful than it does in this scene, and the Tenth Doctor’s enthusiasm has rarely seemed more convincing. This Doctor is jubilant so often that his expressions of joy can sometimes seem diminished in effect, as if that joy is too easily won. Here, his determined outburst of positivity as he stares down Satan and faces the prospect of losing Rose portrays that sense of joy as something fought for and completely earned, and that makes this scene one of the Tenth Doctor’s very best moments.

This episode was written by Matt Jones, who never wrote for the show again, but I’ve read that it was heavily rewritten by Davies; it’s sort of a shame that he didn’t get a writing credit here, because I honestly think it’s his best work. “Midnight” is also a brilliant exploration of the Doctor’s mind and soul, but it’s a very bleak one; this episode manages to do a lot of serious, insightful work about the Doctor (and, to a lesser extent, about Rose as well) while maintaining the sense of optimism and enthusiasm that is so central to the Tenth Doctor. It shows that serious episodes and fun episodes don’t have to be completely separate categories, and as such it’s a pretty much perfect combination of everything that is good about this show. A+

#doctor who#female doctor#season 2#tenth doctor#david tennant#rose tyler#billie piper#russell t davies#reviews

0 notes