#the category of female husband was very broad but it includes identities which would be lesbian bisexual or trans today

Photo

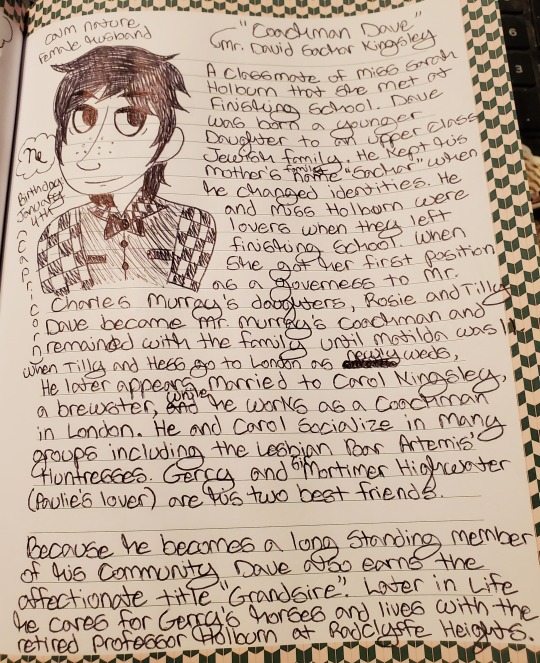

12/22/22- And I did a sheet for Coachman Dave too.

“Coachman Dave”/ Mr. David Sachar-Kingsley

A classmate of Sarah Holburn that she met at finishing school. Dave was born a younger daughter to an upper class Jewish family. He kept his mother’s family name Sachar when he changed identities.

He and Miss Holburn were lovers when they left finishing school together. When she got her first position as governess to Mr. Charles Murray’s daughters Rosie and Tilly, Dave became Mr. Murray’s coachman. He remained with the family until Tilly was eleven.

When Tilly and Hess honeymoon in London as newly weds, he later appears married to Carol Kingsley, a brewster while he works as a coachman in London. He and Carol socialize in many groups including the lesbian bar, Artemis’ Huntresses. Gerry and Mort (Paulie’s lover) are his two best friends.

Because he becomes a long standing member of his community he also earns the affectionate title “Grandsire” to indicate his elder status. Later in life, he cares for Gerry’s horses and lives at Radclyffe Heights with the retired Professor Sarah Holburn.

Birthday: January 4th (Capricorn)

Dave is a calm natured female husband. If he were alive in the 2020s instead of the 1800s, he’d most likely be a trans man.

#Tilly: The Progress of a Victorian Lesbian and Female Husband#b. h. avondale#female husband#victorian lgbt characters#historic fiction#writeblr#WIP#my drawing#capricorn is traditionally the sign of the father in the zodiac and I wanted Dave to be a father figure to a lot of the younger gays#he is old enough to be tilly's father and he's the generation before her#Carol is ten years older than him while Sarah is his age#they're his two main loves#I was trying to give everyone different love stories and life stories but there's some overlap and mirroring#nanowrimo 2022#the category of female husband was very broad but it includes identities which would be lesbian bisexual or trans today#he's level headed to counter balance Gerry being very ready to throw hands

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Literature & Reading// Fiction and American Lit

Going into EWU I had little to know knowledge of what a literary analysis actually was, nor did I have any idea how to do it without plain summary. However, through Ian Green’s Intro to Fiction and American Lit I class I have developed my skills tremendously and I can create theses so much more easily and know how to prove them. These classes have improved my writing so much and with them I know I can apply some of the different techniques he used to teach me into lower level classes, so those students may find success earlier than I did. I have also been able to find a stronger interest in classics in literature and with a teacher who did not encourage just the canon and the white man’s perspective, I can help create an environment in which voices are actually represented in what we read and learn through.

The Language versus the Origin: Identities Exist Long Before Their Labels Do

NOTICE: It is important to note that throughout this paper, as a writer, I can only critique these scholars from a homosexual, cisgender female point of view. As a scholar, one must note that they inherently have biases especially when writing about a group of people they do not identify as and it must be noted as such. Whether one identifies as a woman or a womxn or a they/them or anything else, it must also be recognized that much of this language has only erupted in the last thirty years or so and we must infer from the descriptions other’s use.

While the ideas of gender roles have existed for hundreds and thousands of years, those not aligning to the binary of these pink and blue stereotypes as we know now have been around for just as long. While the acceptance of these non-traditional ideas is still formulating in big waves, the language that we have to surround these topics has increased exponentially in the last few decades. However, this allows for much disagreement over older texts that deal with gender and sexuality and whether they “were” gay, transgender, or non-binary among other identities, and whether as scholars we can accurately pinpoint the identities without having these explicit messages that “This Character is Trans”. In regard to Mountain Charley, a tale of a person who was born and raised “female” who took upon a male identity in parts of adulthood, and other 19th century American texts, gender is discussed and critiqued in negative ways because to the inability to perfectly define the sexual and gender experience due to the lack of language available during that period.

Professor Peter Boag, a history teacher at WSU, has multiple articles about gender in 19th century Western novels. Boag says, “This reveals a problem that confronts historians: it is anachronistic to impose our present-day terms and concepts for and about gender and sexuality — such as transgender — onto the past” ([The Trouble…]325), but if someone were to describe in detail how to make banana bread, but instead called bananas plantains and measure everything in the metric system and titled it “Fancy Loaf”, would it still be incorrect to point out that it is still, literally, banana bread? Though it is notable that the word “transgender” only became commonly used within the last quarter of the 20th century (Boag [The Trouble…]324), the language not being available for use does not excuse that existing not within a gender binary but instead a gender spectrum has happened for all of history.

While the west is typically thought of as being settled by white men, the Homestead Act allowed for anyone to purchase 160 acres for only fourteen dollars (Patterson-Black 67). Between five and ten percent of all homesteaders were women (Patterson-Black 68) as the only requirement was to be head of a family or twenty-one years of age. This uncommon knowledge has been holding back the gender ratios as well as power structure that was at work of the nineteenth century that we can distinctly trace back with a paper trail. While female homesteaders were perpetuated as dependent on their husbands, dance hall participants, or prostitutes (Patterson-Black 69), the real women who took on this land ownership were strong and independent workers. If these women were to exist in these generally “masculine” roles, why can’t other people existing on the gender spectrum have also taken advantage of the “wild wild west” and its opportunities?

While we have a large dictionary of words to describe various sexuality and gender labels, the incorrect and offensive terms are still used. Boag says, in his article from only fifteen years ago:

“Of course applying our terms and concepts of transgenderism and transsexuality to the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century is problematic. The concept of transsexuality only crystallized in the 1940s and 1950s when advancements in medical technology allowed individuals who felt they had the wrong sex or body to surgically reshape them. Since then, transsexual identity has expanded to include those who choose not to, or are unable to, surgically change their bodies to conform with their gender identity. In the last quarter of the twentieth century a broader concept of transgenderism emerged. The new understanding includes transsexuals, but it also embraces a whole set of people who, perfectly satisfied with their bodies, nevertheless identify with the gender "opposite" of the one society normally assigns to their bodies; it also counts people who truly transcend normative gender categories, wanting to be seen as neither female nor male.” (Boag 479-480)

The term “transsexual” is not a term used to describe those who are transgender and most of the population is very uncomfortable of this term; one’s gender experience is not limited to their genitals and whether or not they would like to alter it. While many trans people would like to transition as much as they can medically, not everyone wants to or needs to, and either way they all fall under the broader term of transgender (or trans-masc or trans-feminine). This language used to refer to such a broad group of people is not a positive or useful thing to do, especially when in the twenty first century now that there is easy-to-access language to discuss these things. This idea ties into the transmed community who believe that one must medically transition and desire to to be trans, whereas not everyone who experiences dysphoria that comes with being trans would have their dysphoria solved from being on hormones or getting surgeries, and for some, medically transitioning is just not possible. One’s genitals does not in any way determine their gender, and only may help someone feel comfortable with their body upon altering them.

Boag says, “Such a sequence of events undoubtedly helped Greeley reclaim balance in his sense of gender norms and sex roles which had recently been upset by encountering a "woman" dressed as a man in a region where, and at a time when, few women could actually be found. Moreover, the meaning embedded within this story about changing physical locations and gender identities anticipated a theme that decades of later regional historians and popular writers assumed as axiomatic: the West was a man's world, a place either not welcoming to, or simply devoid of, women-creatures best relegated to the more domesticated East” (478) in response to a journalist finding a womxn dressed in traditionally “male” clothing working in the west, which turned out to be not quite as prosperous as he once thought. This section of Boag’s article, “Go West Young Man, Go East Young Woman: Searching for the Trans in Western Gender History”, is exactly contradictory of what Patterson-Black claims in her article in which she is researching women in the great plains. While Boag notes what the writers and historians said during this time, he ignores the researchable statistics and within this ignores all of the women who made their way across America.

In researching gender in the nineteenth century, one might come across a book called, “‘The Horrors of the Half Known Life’: Male Attitudes toward Women and Sexuality in Nineteenth Century America” by G.J.Barker-Benfield, a man. This book “covers” (albeit very, very generalized) the ideas a man would have about a woman during the 1800s; from gynecology to multiple chapters about sex, this text, much like the articles by Peter Boag, can not accurately define the life of a woman during this period. This book not only perpetuates the binary gender idea rather than one existing on a spectrum, but also titles its chapters “Man Earn--Woman Spread” and “Architect of the Vagina” whereas not all women “spread” for men nor do all women have vaginas. While the in the intro, Barker-Benfield notes that he is a man and is to be met with criticism for creating this text following a variety of other men creating “feminist” texts about women, this did not prevent his publishing nor did it make him second guess these incredibly sexualized phrases about the real experiences of womxn. It is important to question why something would need to be published about the male version of the womxn’s experience when that is almost solely the history we receive anyway. The Horrors intro is almost entirely about how feminists are interested in the gynecological aspect of the text, but this limits all women to only their sex, and not even all women. While Horrors does recognize the difficulty of a non-male lifestyle in the nineteenth century within its title, the encouragement of a binary gender situation obscures and ignores all the womxn who did not participate in the standard gender roles of the time and who existed beyond the binary.

“Arresting Dress: Cross-Dressing, Law, and Fascination in Nineteenth-Century San Francisco” by Clare Sears opens with the true story of a womxn, who in 1866, was caught “cross-dressing” in public on the arm of another person (who the author calls a man or possibly a woman). The mxn who were regularly arrested for dressed in feminine style clothing called for her arrest, as she had just been ignored during her first appearance so the police arrested the womxn, Eliza DeWolf, the next day (Sears). This text addresses the increasing number of laws against “cross-dressing” put in place, aggressively, in the nineteenth century. While this did have a detrimental effect on those not “dressing in accordance to their sex” (however possible that is), it also publicized those who did it and therefore increased awareness of the womxn who were not wearing “less than three pieces of women’s clothing” (Sears). Other than the language of cross-dressing, the people who suffered these laws were able only to express their gender identity without the structure and the labels we have today and without these, they were even less understood.

However, the act of “cross-dressing” is not a politically correct one; clothes do not have gender and people should and get to decide how they identify on their own. By referring to the people who chose to dress eclectically between standard feminine and masculine clothing items, it is easy to assume that they are just doing it for fun or to be weird or because they are weird, and not because they identify differently and present differently on the spectrum than the majority of people in that day and age. While these people did dress in clothes traditionally the opposite of what their assigned gender is (based on sex), it is inappropriate to call them cross-dressers at any point in time.

Gender and sexuality ultimately exist on an intersectional spectrum. Darnell Moore, of Columbia University and inaugural chair of Mayor Cory Booker's LGBT Concerns Advisory, writes that queerness is both inherently structured within each class and then, due to its intersection, is also structureless: “Yet, and again, even in its quests to resist structures, the "queer" exists as another space wherein structure is once again reconfigured and operationalized, particularly as it relates to the ways that some bodies and political interests are made visible in queer movements while others are not” (Moore 259). It is nearly impossible to interpret Mountain Charley’s gender and sexual identity because, at the time of writing, the language did not exist. However, this lack of structure and identity labels does not disprove that Mountain Charley very well could have been butch, transgender, non-binary, gender fluid, or a myriad of different identities.

Moore says, “[this] critique, however, was not enough to correct the erasure. Instead, we developed the Queer Newark archive, a structure of documents and material culture, as a means to render visible the lives of queer subjects who have been othered out of queer histories by, often, other queer” (259-260). This is important to note, that while there may be clearer historical texts out there of people being definitively queer (gay or lesbian for example), it should not have to erase the other examples that are less obvious. It is still ever important to recognize those who do not have that label, whether their story was created before or after the label existed, and not to erase them from history, just because they are not outright saying they are homosexual.

In chapter three, when Charley decides to act upon the solution they composed, it does appear as Charley’s “only option”. “At length, after casting over in my mind everything that presented itself as a remedy, I determined upon a project, which, improbable as it may appear to my sex and to those who have followed my life thus far, I actually soon after put into execution. It was to dress myself in male attire, and seek for a living in this disguise among the avenues which are so religiously closed against my sex” (Mountain Charley 18). Note that the only concern is against religion, however, Charley does feel that they could find themselves in this role despite their sex. Charley “fully determined to seek a living in the guise of a man” (Mountain Charley 19). While one could argue that this was their only option, the truth is that Charley ultimately could have found another man to marry or become a beggar; most people would not want to live as the gender they do not identify with unless it was life or death, and at this point the options were poverty, admitting the mistakes they made to their father, or finding a new husband. While Charley never explicitly says that they are a man confidently, rather only commenting on the comfort of being in that “persona”, it is not improbable to assume that Charley was not a cisgender woman.

“Although I had resumed my womanly dress and habits, I could not wholly eradicate many of the tastes which I had acquired during my life as one of the stronger sex” (Mountain Charley 29). Had Charley been cisgender, there would have been an experience of gender euphoria at the return to “womanly dress”, instead, Charley was not comfortable in this femininity and still found something to identify with in their masc side.

Gender has no perfect definition; it is something that exists as a spectrum and almost no one lies perfectly on either edge. The spectrum is not a single line either, there is not just male and female with a combination in the middle but instead it is more of a circle with different points along the edges: agender, cisgender, genderqueer, bigender, two-spirit, and the list goes on. While the visibility of gender non-conforming people has improved infinitely since the nineteenth century, what with these different labels being created and being publicized, it still is not a perfect utopia of freedom of expression. Much of Mountain Charley’s concerns over dressing “like a man”, such as religion, are still ever present today. Much as one may argue that Charley had to dress as a man to survive, there are thousands of people today who have to dress aligned to one sex or another to survive in the same way. Charley’s story could be comparative to trans-masc or trans-feminine individuals who have to dress according to their assigned gender at birth to continue to have a safe life, whether it exists as protection from being kicked out of their home, attacked or assaulted, or to continue to partake in their own religion.

Not only this, but Charley variates between comfort in their masculine dress and their feminine dress and it is inconsistent; there is no true gender euphoria within either. Charley, by this definition, falls under the umbrella of genderqueer. While gender does exist more than dress, the “personas” Charley takes on impacts their personality and skews either side together to create a non-binary individual. While Charley does not have any language to determine this, nor do they necessarily need any because labels are not important for everybody, it is important to be able to consider any and all texts queer texts and not omit anything.

Boag says “Period stories of Monahan as well as those of the Mountain Charleys and even Horace Greeley's clerk are progress narratives in their own right: the cross-dresser's transformation into a man is temporary and for some specific purpose. But more, the progress successfully terminates when the subject resumes a womanly identity, passing the remainder of her life, as one period observer put it, in "a sphere suited to her sex." (“Go West” 497). While these womxn often dressed in quintessentially male attire to “save” themselves, they have to go back to what is “suited to her sex”. These womxn were obligated to reveal their sex and align with their sex, whether or not they felt more like themselves when they were dressed in that masculine attire; it was easier to wrap up the story of these Mountain Charleys to have a conclusion that they are “normal” and weak feminine ladies who desire to return to that life, rather than to live out their lives as butch womxn, men, or gender non-conforming individuals. Boag’s argument that these stories are just for “cross-dressers” is not accurate; it is a way to expose the womxn who did not live on their designated gender line and allow for other people to view it in a positive manner.

Ultimately, as scholarship is continually written about these people in history, the language one uses must be updated and relevant with the times; we have the words to describe these people and we should use them. However, we should use them with caution--no one knows these people and their “true” stories, but one can identify transgender and queerness in any text from every point in time, despite the word “transgender” only finding its grounds less than a quarter of a century ago. The biases these authors have must be taken into account as one reads their scholarship and it is important for us, as readers, to recognize transphobic and anti-LGBTQ+ commentary in works and let others know that it is not okay. Due to language and certain views, Mountain Charley and other 19th century texts are critiqued negatively due to either their representation or alleged non-representation of transgender or non-binary individuals.

Works Cited:

Barker-Benfield, G J. The Horrors of the Half-Known Life. Routledge, 2000.

Boag, Peter. “Go West Young Man, Go East Young Woman: Searching for the Trans in Western Gender History.” The Western Historical Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 4, 2005, pp. 477–497. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25443237.

Boag, Peter. “The Trouble with Cross-Dressers: Researching and Writing the History of Sexual and Gender Transgressiveness in the Nineteenth-Century American West.” Oregon Historical Quarterly, vol. 112, no. 3, 2011, pp. 322–339. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5403/oregonhistq.112.3.0322.

Guerin, E J. Mountain Charley or the Adventures of Mrs. E.J. Guerin Who Was Thirteen Years in Male Attire. University of Oklahoma Press, 1968.

Moore, Darnell L. “Structurelessness, Structure, and Queer Movements.” Women's Studies Quarterly, vol. 41, no. 3/4, 2013, pp. 257–260. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23611522.

Patterson-Black, Sheryll. “Women Homesteaders on the Great Plains Frontier.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, 1976, pp. 67–88. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3346070.

Sears, Clare. "Arresting Dress: Cross-Dressing, Law, and Fascination in Nineteenth-Century San Francisco". Duke University Press, 2015.

0 notes