#the different lives of narrative structure and why cinema will never die

Text

rewatching korra as an adult is truly an insane experience

#ive noticed this w so many films and tv series and i find it so fascinating#how the narrative structure changes depending on where you are in life#it’s like seeing things through completely different eyes and its just ahsjdjkfk. wow#its that feeling of ’i wish i could experience this for the first time again’ and then you CAN#maybe i’ll write about it someday#the different lives of narrative structure and why cinema will never die

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

leftist suriya characters appreciation post

since soorarai pottru, been thinking more about all the explicit leftist characters suriya has played in his career. and i actually mean explicit - characters that are supported by the narrative framing and structure and not just my own headcanons and stuff or a throwaway generic goody-shoe typical hero line. i have been itching to talk about this cos it’s obviously in my field of interests

suriya has played 4 openly various brands of leftist now, and that’s pretty cool! i love that none of them are cookie cutter personalities of each other, they all have their own select trait. this post is a toast to them;

michael vasanth (ayutha ezhuthu, 2004)

vimalan (maattraan, 2012)

iniyan (thaanaa serndha koottam, 2018)

maara (soorarai pottru, 2020)

[small write up on each character with pics behind the cut]

*****

1. michael vasanth (ayutha ezhuthu, 2004)

so michael was his first, said to be inspired by an actual university popular marxist student leader, george reddy. michael is very obviously somewhere along these lines - he himself is within the film known as the leftist student leader on campus with a huge following, much to the chagrin of his professors who want to stamp that out of him. he’s openly engaged in campus politics as well as politics outside, and he’s most definitely no weak willed liberal because he has no problems with violence or direct action, which he organises. he organises villagers to stand against others on their own feet, never once preaches about lying down and taking it easy or playing polite. which was nice to see lol i hate liberals who have morals about property damage but in ayutha ezhuthu, michael clearly doesn’t give a fuck. he and his group break things and smash cars and lorries on their way and threaten physical violence on their opponents too which is the way it should be because to him human lives are worth more than any property or vehicular damage. he never shies away from that. hell yes to violence and structural damage!

probably the most definite trait of michael compared to other suriya leftist characters is that michael still believes in the establishment and electoral politics, which u don’t particularly see his other leftist ones talk about. but here, michael works within the system, and trusts it to bring change if u put in the effort into that. though, it’s not as frustrating as it sounds cos michael’s work is not geared towards other liberals, but in villages and rural districts where he goes to spread word, and makes them choose their own leadership to represent. it’s way more marxist aligned and ~rise of the proletariat~ here instead cos he bypasses liberal bougie nonsense and never once is his voice used for that, but used towards and for the working class directly to both take up arms and resist violently themselves + hold ranks for themselves and choose their own leaders to influence their local politics/protect their environment.

michael is fundamentally very marxist, with a dose of direct action plus violent resistance if need be, and supports organised proletariat uprising within an established political system playing towards electoral politics

(of course, a point to note in why this isn’t as frustrating as it sounds as mentioned above is cos this film was released in 2004. would michael still believe in the establishment and electoral politics now? things in 2020 are very different with all of us more aware of things around us and globally, it’s definitely a debate to be held. i doubt he will, since he’s not a pacifist or liberal. he’d say fuck electoral politics, all my homies hate electoral politics)

2. vimalan (maattraan, 2012)

second very openly communist character he played. prob gone a bit forgotten for others since he does die halfway through the film (which itself isn’t a favourite of anyone either, fans or neutrals) rip but can’t go by without mentioning cos i remember liking this character a lot and i teared up in the cinema first watch when he died. i was mad they killed the suriya i loved instead of the other one whom i found annoying lmao

vimal supports workers’ strikes and unions against bosses, even when that boss is their own shitty father. this automatically makes him stand out instantly considering he is sympathetic to the working class despite at the cost of his father’s annoyance with him. he’s also the first character suriya plays who’s explicitly anti-capitalist with line(s) about it, since michael had no canon lines regarding capitalism from what i recall. vimal outright does.

the leftist imagery tied to vimal the most is che, which is a nice touch. his room has at least one poster of him, and his phone’s wallpaper is also him. u can also see bhagat singh and ho chi minh books on his shelf. so.. safe to claim where vimal’s political ideologies are. it’s both tied in pictures and him siding with workers for their rights against corporations, since he obviously likes revolutionaries. vimalan was a class traitor and a supporter of the working class poor bb tragically gone too soon. ilu u didn’t deserve your terrible fate, sweet commie good boi :(

3. iniyan (thaanaa serndha koottam, 2018)

iniyannnnnn i love him and i think it’s a suriya char with one of the best character arcs in his whole career. mostly cos he had a very distinct ‘’yes i want to work for the government and change things from within’’ phase which gets squashed over the course of the film. we see him start off obviously in a very blatantly communist neighbourhood in a song that is also very specifically anti-establishment/politicians with a lot of hard resistance vibes. the entirety of sodakku is a very good introduction to him and what he stands for - in general the film promises upon wealth disparity, useless bougie politicians, and the rest of us being crushed under them.

what happens to him at the end of the movie is FANTASTIC because he no longer gels with what he wanted at the start of the movie. iniyan’s key leftist trait to me is that he’s the most anarchist of suriya characters, varying from other leftist suriya characters. he refuses to work with government powers and authorities, he looks down on their entire establishment and institutions (he does not at the start of the film, which is vital cos again, he wanted to work alongside them at first), and depends more on the good will of individual people over job titles, while clearly engaging in mutual aid and distributing wealth. these are very distinct anarchist ideals. i’d still peg him as anarcho-communist but would say he leans more towards anarchy and progressing on mutual aid over official state resources or state people for any kind of positive change since his faith in them has pretty much diminished by the climax. he does not give a shit about politicians, cops, or any kind of authorities at all, leaving them in the dust to raise his black flag and do his own anarchist hot shit.

iniyan is a good example of an anarchist arc for me in tamil cinema in simple commercial terms without heading too deep into actual words and phrases in a big hero movie, cos it’s also very easy to explain to anyone the shift in his ideas and his eroding faith in institutions with power. good for him!

4. maara (soorarai pottru, 2020)

this should be fresh in everyone’s memory, but yes, a character who is obviously in your face about it since he has an actual line - ‘’you’re a socialite, i’m a socialist’’ which caused all of us with good taste to whoop and cheer. plus he was very sexy in this whole scene, so what a bonus. it’s the most explicit thing said by him in the film, but there are also other little things peppered into his speech and background imagery showing u the kind of person maara is.

he gets married to bommi in a self-respect wedding ceremony. no priests or any kind of traditional hindu iyers/chants involved. u see it clearly with a periyar pic hanging behind him explaining who he is. he wears black a lot in the film, which fits him being a periyarist so i’d label him as such and consider it his standout trait from other leftist characters suriya has played previously because this is the only character with explicit periyar symbolism (i kid u not i saw multiple sanghis being very angry suriya dressed in black in this movie and were harassing him on twitter constantly since sp released. die mad, uglies). obviously, this also fuses well with the little things we see of him implying he’s ~lower caste~ like his in-laws being embarrassed about him on behalf of their own caste, and paresh sanitising his hands after shaking hands with maara on the plane, which is not subtle at all and trademark casteist behaviour about touching someone ‘’lesser’’ than you and u view them as ‘’dirty’’ or beneath you. as well as maara’s remark about breaking the class and caste barrier during his radio interview. being a periyarist fits seamlessly.

there’s also a bts vid of suriya on his bike where you can see an ambedkar pic pasted onto the side. i can’t remember any scene in the film where u can see his bike from this angle but it doesn’t matter, cos u can definitely tell the kind of person maara is and how he was envisioned as a character - an explicit socialist and periyarist, with a natural fondness for ambedkar too since ofc they overlap as many do irl as well. it is very in tune with his background in the film and i liked seeing the tiny aspects of these things seeded within the movie throughout from beginning to end. it’s explicit in a way that isn’t jarring or artificial, and a nice layer to him and feel endeared to since maara is a great character. u support him all the way with him being unquestionable in his stance and ideology. the sexiest leftist suriya character, if i say so myself, ahem.

/////

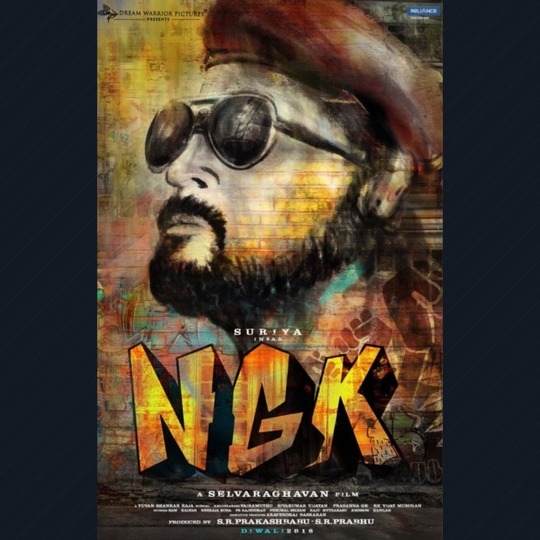

5. ngk (ngk, 2019)

bonus: THIS IS IT. THE BIGGEST SIKE. THE BIGGEST WHIPLASH. THE BIGGEST BASTARD.

it’s here cos damn, when they released that first look, i completely lost my shit cos that poster was sooo heavily che inspired and very, very obviously marxist. cue me thinking that holy shit suriya is openly playing some kind of marxist guerilla revolutionary in ngk and he’s gonna be some brand of violent radical leftist i’m gonna fall in love with. the beret, the raised fists, the red.. i was ready to be head over heels for this guy.

except of course, none of this was true, cos once the film released, u know that poster was only meant to signify how his village looked up to him before he sold them all out. it’s literally just a mural on the wall where a kid stares up at him in a larger extended poster. he COULD have been that character, but ngk’s character arc was a negative character arc and his moral downfall from the start to the end of the film, sacrificing all he stood for to arrive at his end point which was just dragging his village and all the youngsters who believed in him to the pits before jumping party to the winning group and abandoning all of them after manipulating them to act in his favour to gain sympathy. not to mention, also selling out to corporate tools to harness their power and influence in order to rise to the top himself, something he very openly states at the beginning of the film to his mum and wife that working like that is no way to live. he has a full reverse by this point, compared to how ngk was introduced to us as an audience with that first look of him.

the marxist poster was a complete 180 to how ngk falls on the spectrum at the end, but it was a great ride nevertheless and at least one thing was still true - i still fell in love with him cos he was such an asshole bastard but still so hot i had to give in. biiiicchh. i love u, non-leftist regressive jerk. u may have pulled the biggest sike on me, but.. my heart is yours, slut <3

*****

ok that’s really it and all i wanted to say so hopefully at least a few people read this lmafooo. i do think these characters and time have sort of seeped into suriya over the years as evident by his shifting left in the last couple of years, and openly also saying he has had a lot of perspective changes on things around him. he has been noted in recent interviews saying stuff like how he’s in favour of a cashless society, talking about a whole new level of poverty class being created during this pandemic. his written articles/statements/agaram related speeches takes jibes at india’s education system being brahministic/casteist in nature and how it creates barriers for the lowest strata of society while also being very sensitive about student suicides, showing understanding of it as a systematic failure and not an individual one, courts not functioning for justice, not demonising protests as it’s the only act left for the voiceless, etc. it’s nice. i wouldn’t go as far as to call him a leftist until he proves that to me (suriya is still very much in that liberal zone of appreciating the police and military institutions so i will never consider him one of us until he sheds these allegiances and rethinks his stance on them in society), but i’d say he’s definitely the furthest left of all prominent actors in tamil cinema as no one else really has said or written the things that he has, for which i’m very proud of him.

so keep up the good work and hot shit comments and ballsy articles, suriya, i look forward to u shifting further left and pissing off everyone from right wing patriotic assholes, to centrist bootlickers, and even cowardly liberal pacifists. i believe in u and i hope he crosses that steep liberal curve soon since we were all there at some point as well.

that’s all goodbye i love suriya thanks for reading

#hooo lads finally wrote this like i wanted to! target audience? spare target audience??#suriya#tamil cinema#kollywood#mix#mine*#commentary#politics

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

A hero in her own mind... On Daenerys Targaryen (part 5)

This post is a continuation of my analysis of Daenerys Targaryen’s narrative arc in Game of Thrones (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4). Like the previous post, the focus is on her season 6 arc, which I’ve had to break up into several separate parts due to length. Season 6 marks a crucial moment in Daenerys’ journey and there are a lot of things to unpack from her scenes.

DRAGON AND CONQUEROR

In the last post, I said that Daenerys burning down the Dosh Khaleen marked a symbolic rebirth for her. A rebirth that visually underscored her alignment with the elemental power of fire; an alignment she shares with her dragons, as they are Fire made Flesh. Thus, Daenerys the Dragon was awoken in the fires of the Dosh Khaleen. She is fiercer now, more ruthless and more determined than ever to do whatever it takes to reach her goal.

This becomes apparent in a scene from episode 6 where Daenerys are leading her new and improved Khalasar towards Meereen through a desert landscape. She discusses her plans for tavelling to Westeros with Daario, who says that “you weren’t made sit on a chair in a palace. You’re a conqueror Daenerys Stormborn”. I find this line interesting because it makes a distinction between conquering and governing. Daario is paying Dany a compliment but at the same time it reads as a bit of a backhanded one: she’s made for conquest, not governing. From his point of view it is absolutely a compliment because he doesn’t care about governing – he likes war and women. But Daenerys’ goal is not just conquest, it is also governing Westeros as its queen and she’s hasn’t been very successful in her attempts to govern Meereen.

This dialogue, however, isn’t the most important part of the scene but rather what follows after their little exchange. Dany stills her horse, sits quietly, scanning the landscape – as if she is sensing something that others cannot. Then she tells them to wait as she rides ahead alone. Daario and the khalasar wait. The horses become restless. Then we hear a loud shrieking and we see the shadow of a dragon gliding over the hills of yellow stone that surrounds the khalasar. Drogon flies into frame as the music swells triumphantly. Drogon lands before the men and we see Daenerys is sitting astride him, in complete control. Then she proceeds to give a motivational speech to her new khalasar.

youtube

What is important about this scene? Firstly, this scene establishes that Dany now has complete control over her Drogon, the most difficult of her dragons. Throughout season 4 and 5, she found it increasingly hard to control Drogon, to the point that he simply left her and ranged over various parts of Essos (Tyrion saw him in the ruins of Old Valyria). She had never ridden him until the last episode of season 5 and that only came about because of a state of emergency. Drogon was uncooperative when they landed in the Great Grass Sea. She couldn’t get him to obey her. Now Daenerys is in complete control of her dragon. She rides Drogon as if it is the most natural thing in the world – and she has a special bond with him. This is a demonstration of her power – a power that is every bit as otherworldly as walking unharmed out of a flaming inferno.

Then there’s the speech. Why include a motivational speech at this point in her narrative? The start of this scene has already established that the Dothraki now follow her and that she has decided to pursue her goal to conquer Westeros rather than continue to govern Meereen. On the surface of things, this speech offers no new information. However, I would argue that this scene has a very specific function in relation to the audience – and that it should be interpreted from a Doylist rather than a Watsonian perspective. That is, what is important about this scene is how it presents Daenerys and her ambitions to the TV audience.

This scene can be somewhat tricky to decode because it is, in a sense, a wolf in sheep’s clothing. It presents itself as a conventional variation on The Rousing Speech Trope, which is a standard element in epic cinema, be it fantasy, period or action movies. This scene, however, isn’t standard at all. Rather, it inverts the trope but you have to pay close attention and you have to be conversant with the conventions of the trope. In order to spot the inversion of the trope, it is necessary to compare Daenerys’ speech with a couple of straightforward examples of the trope.

One of my favorite examples of The Rousing Speech Trope is from Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003), where Aragorn gives heart to the soldiers before the Battle of the Black Gate in Mordor where they face overwhelming odds. It is a rather poetic speech and Viggo Mortensen is completely on point with the delivery. Interestingly enough, this speech is not from Tolkien’s books but an invention of the screenwriters. The reason for this invention can most likely be found in the conventions of the epic cinema. A rousing speech given by the hero before the final battle is standard operating procedure when it comes to this genre.

youtube

“Friends of Gondor, of Rohan – my brothers! I see in your eyes the same fear that would take the heart of me. The day may come when the courage of Men fails; when we forsake our friends and break all bonds of fellowship; but it is not this day – an hour of wolves and shattered shields, when the Age of Man comes crashing down – but it is not this day!!! This day we fight! By all that you hold dear on this good earth – I bid you stand! Men of the West!”

Another favorite of mine is the bastardized and altered version of Elizabeth I’s famous Tilbury Speech that Cate Blanchett delivers in Shekar Kapur’s Elizabeth: The Golden Age (2007).

youtube

“My loving people! We see the sails of the enemy approaching. We hear the Spanish guns over the water. Soon now, we will meet them face to face. I am resolved in the midst and heat of the battle to live and die amongst you all! While we stand together, no invader shall pass. Let them come with the armies of Hell! They will not pass! When this day of battle is ended, we will meet again in heaven… or on the field of victory!”

This scene is both visually and dramatically effective – with a flame haired Elizabeth who has donned armor like a latter-day Joan of Arc. Sitting a white horse, she is a dramatic sight as she delivers her rousing speech. However, this speech bears little resemblance to the original and very famous speech that Elizabeth I delivered at Tilbury in July 1588. Only a few lines from the original speech has been included (highlighted in black). Why is that? Elizabeth I’s Tilbury speech is very famous but it doesn’t really conform to genre conventions. It was written several centuries ago and thus it may not appeal to a modern audience.

The Rousing Speech Trope is most often deployed before a battle of some kind. (Top 10 Battle Speeches). The situation is dire, our heroes are on the defensive and the odds are overwhelming. Then the hero makes a speech to rally his men, reminding them of what they’re fighting for, etc. The music swells triumphantly as the soldiers cheer and then they are ready to fight. Such is the standard structure of a scene where this trope is used. What is particularly interesting about these speeches is the use of words such as we, us and our. The function of such a speech is to create a sense of fellowship, to create unity in the face of adversity. The aim is to stand united against a common foe by remembering the things that are worth fighting for, even worth dying for, whether that be family, country, freedom or even mankind itself. Within the narrative, the function of Rousing Speech is to give heart to the soldiers who are about to fight. However, such a speech can also evoke strong emotions in the audience and serve as a reminder of what we hold dear. Interestingly enough, the Rousing Speech Trope is almost always used in situations of defense. It is about motivating people to defend something precious. This is a very important point to keep in mind when we take a look at the speech Daenerys gives to her khalasar.

The scene with Dany’s speech to the Great Khalasar has roughly the same structure as most examples of The Rousing Speech Trope. However, the language and the message are quite different:

“Every khal who ever lived chose three blood riders to fight beside him and guard his way. But I am no khal. I will not choose three blood riders. I choose you all. I will ask more of you than any khal has ever asked of his khalasar. Will you ride the wooden horses across the black salt sea? Will you kill my enemies in their iron suits and tear down their stone houses? Will you give me the Seven Kingdoms, the gift Khal Drogo promised me before the Mother of the Mountains? Are you with me? Now and always?”

There is no real unity in this speech. Note how the key words: we, us and our aren’t present at all! Dany presents herself as an extraordinary ruler to the Dothraki – a Khal of Khals, so to speak. She asks a number of rhetorical questions? Questions that she doesn’t need any answer to. They just serve to rile up her troops into a frenzy. There is no us, no we; only you and I – there is no true fellowship between Dany and her army, only ruler and subject. She asks them to serve and they will serve her by giving her what she wants through violence. Daenerys paraphrases Drogo’s speech from season 1 (episode 7), leaving out the more unsavory bits about rape and slavery – though these things are not mentioned, neither are they expressly forbidden. It is understood that slaughter, pillage and rape will happen when she unleashes the Dothraki upon Westeros.

This speech highlights just how ruthless Daenerys has become in pursuit of her goal, especially when you compare it to the discussion she had with Jorah Mormont and Barristan Selmy when she arrived in Astapor in season 3 (episode 1). That was when she needed an army – and the reason she chose to acquire an army of Unsullied was because she didn’t want innocents to suffer in her war of conquest. She made that decision based on these words by Jorah Mormont:

“There’s a beast in every man and it stirs when you put a sword in it. But the Unsullied are not men. They do not rape. They do not put cities to the slaughter unless they are ordered to do so.”

The Daenerys of season 6 is a far cry from the kind-hearted young woman who was moved by the plight of innocents in season 3. That woman couldn’t bear the thought of her armies raping and pillaging their way through Westeros. Now she’s ready to unleash an army of Dothraki, whose entire culture appear to revolve around slaughter, rape and pillage! She may have told Yara Greyjoy that the Iron Islands has to stop reaving but she didn’t forbid the Dothraki their wartime “traditions”. Daenerys has definitely stepped onto a darker path and she is willing to compromise her own moral integrity to put her backside on the Iron Throne.

Since season 5 I have started to doubt whether Daenerys is supposed to be a hero in this story. She is undoubtedly one of the protagonists and she has done a number of remarkable things. Her crusade against slavery is a noble cause but the brutal way she handles opposition makes me wonder about her abilities as a ruler. So far, her intentions have been good but the road to Hell is often paved with good intentions. However, conquering a country because she thinks it is her birthright is a matter that very different from ending a cruel and inhumane system such as slavery. Daenerys’ quest for the Iron Throne is not an altruistic one. It is a selfish one – and the price will be paid by the people of Westeros.

He fiery “rebirth” marks a crucial change in Daenerys – a much more ruthless woman has emerged from the fire – and I think that her character is stepping onto a much darker path that may very well eclipse the heroic image she has enjoyed so far. This is the reason why I think the showrunners chose to write a scene for Dany that is typical for a traditional hero but where the significant part is the complete opposite of heroic. It is a speech that announces a war of aggression, not a speech that builds unity in the face of a stronger enemy – and heroes generally don’t preach slaughter and destruction in pursuit of conquest.

Incidentally, Jack Bender who directed this scene has some interesting thoughts on this particular subject:

“At the end of the scene, you should be somewhat roused by her and a little horrified. […] She’s not Hitler at Nuremberg, but she’s got the power.” (x)

The comparison to Hitler may be rather tasteless but Bender has a point. He articulates it better in an interview with Vulture:

“Historically, there are echoes of that kind of speech, seeing that kind of fervor for that kind of leader. Power is a seductive thing, and you have to decide whether to use if for good or bad. Every great leader has to know how to wield that sword, and she certainly has the charisma and power to get them back to her. Where it goes from here, who knows.” (x)

In this context, I find it very interesting that it is in season 6 that the show really begins to compare and contrast Jon Snow and Daenerys Targaryen in their roles as leaders. Until now, they have been on parallel journeys but now we begin to see the contrasts between them – and there are some very striking contrasts indeed. In my previous post, I noted the worshipful attitude the Dothraki exhibit towards Daenerys when she emerged unburnt from the fires of the Dosh Khaleen. Jon was met with a similar awestruck attitude when he emerged after his resurrection. But where Dany accepts and revels in the worshipful adoration, Jon quietly rejects it. When Tormund says “They think you’re some some kind of god, Jon simply answers: “I’m not a god” (episode 3).

Even the way the two scenes are shot reveals some interesting contrasts. When Dany exits the fire she remains standing on the steps that lead up to the burning building. There she stands while all the Dothraki prostrate themselves before her. When Jon emerges from the room where he had lain dead, Wildlings and Black Brothers stand in the courtyard of Castle Black, looking up at him. He descends the steps and walk among the men and he quietly defuses the awestruck atmosphere through his interactions with Tormund and Edd.

A similar comparison can be made between Jon and Dany with regard to the manner in which they recruit the Wildlings and the Dothraki to their causes respectively. I’ve already conducted an analysis of how Dany riles up the fervor of the Dothraki with a speech about killing her enemies. Jon Snow goes about his business in a markedly different manner (episode 7).

youtube

Jon Snow asks the Wildlings for their help – then he steps aside and let their leaders debate the question. When he steps into the debate, he stresses that they all need to stand together against the common enemy. The way the two scenes are filmed is also striking: Dany sits atop a huge dragon and looks down on the Dothraki whilst shouting at them whereas Jon is placed on equal footing with the rest of the Wildling leaders. He isn’t even in the centre of the shot – all of them actually stand in a circle! The difference between the two leaders couldn’t be more stark (pun intended). Daenerys secures the loyalty of the Dothraki through shock, awe and sheer charismatic presence whereas Jon secures the Wildlings through earnest cooperation and common goals. Both are strong leaders – but there’s a difference between military victory and governance, and strong military leaders are not necessarily good rulers.

235 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exits in Video Games: Immanence and Transcendence (Calum Rodger)

In this essay, Calum Rodger explores the poetics of exits and transcendence in video games, via the vectored planes of ‘Victorian-thought-experiments-turned-quirky-novella’ Flatland. Read on for reflections on the secret ecstasies and eeriness that accompany discoveries of glitches, nonsensical infrastructures and metatextual moments in the likes of Sonic the Hedgehog, Monkey Island and, of course, the virtual sublime of that San Andrean Heaven.

> Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions is the weirdest little book. Published in 1884, written by schoolmaster Edwin Abbott Abbott, and pseudonymously attributed to ‘A Square’, it describes a strange and awful world of only two dimensions. Its inhabitants – lines, triangles, squares and polygons – are organised according to a totalitarian caste system wherein rank corresponds to the number of one’s sides (nobility are hexagons and above; priests, the highest class, are circles; women, the lowest, are lines). Not that these shapes are conventionally perceived as such by Flatland’s residents: with no way of stepping outside their flat plane of existence, their world appears to them as a series of monotone straight lines in various shades of brightness (colour – the ‘chromatic sedition’ - is brutally suppressed, compromising as it does the ‘intellectual Arts’ of Flatland and, with it, the nobles’ hold on power). ‘Irregularities’ of all kinds - ‘an infant whose angle deviates by half a degree from the correct angularity’, say – are summarily destroyed at birth. Not only must Flatland be an awful place to live; it must also be interminably dull.

> The book is remarkable for the head-spinning extent to which it imagines how a world might be liveable in such dimensionally-limited conditions. It is a necessarily dystopian world: how can one conceive of liberty in a world literally without depth? Flatland is totalitarian by its very form, lacking a structure from which liberty might emerge; there is, in other words, no exit. Only after the narrator’s encounter with a ‘Stranger’ - a ‘Sphere’ from ‘Spaceland’ - does real exit become possible, as the visitor enlightens his incredulous host:

What you call Solid things are really superficial; what you call Space is really nothing but a great Plane. I am in Space, and look down upon the insides of the things of which you only see the outsides. You could leave the Plane yourself, if you could but summon up the necessary volition. A slight upward or downward motion would enable you to see all that I can see.

Unlike conventional dystopias, where the potential of exit is immanent to the system itself (in the irrepressible human parts: love, desire, freewill, etc.), exit from Flatland is transcendent in the genuinely metaphysical sense: a ‘climbing over’ (cf. immanent, ‘remaining within’) one’s dimensional limits, a ‘slight upward or downward motion’ beyond not merely the plausible, but the possible.

> There is an obvious religious subtext to Flatland (it’s telling that Abbott was a reverend and a theologian), with an exit into Spaceland and subsequent transcendence into a God-like omnipresence analogous with enlightenment and epiphany. But this is neither the most timely analogy nor, really, the most revealing. Among Victorian-thought-experiments-turned-quirky-novellas Flatland is surely singular, insofar as it could, conceivably, be accurately ‘translated’ into a 1980s-era home computer game (albeit a very difficult and boring one). And what are the ‘Spacelands’ of contemporary games but extensions of the formal principles of Flatland: virtual worlds constructed according to arbitrary limitations, underpinned by mathematical ‘realities’ to which we mere inhabitants are never granted access? The analogy, then, is between the immanent exits of the games themselves – their deaths, save points, level ends, level ups – which only ever lead to more game, and the transcendent exits lurking imperceptibly somewhere between the game and the code, a ‘slight upward or downward motion’ (which is to say a whole world) away from the limits and objectives set in advance by the game’s structure. It’s an idea which has long interested developers and, more recently, players, with whole subcultures dedicated to finding those exits through which one might ‘look down upon the insides of the things’. But what do transcendent exits look like? Are they even possible? And why – since games are not dystopias we are cursed to inhabit but fictional closed systems in which we participate willingly – do gamers ‘summon up the necessary volition’ to seek transcendent exits at all? While the answers to these questions are beyond the scope of this essay, the transcendent quirks of three classic games can, perhaps, point us in the right direction.

> First: the ambiguous ‘GOAL’ of Sonic the Hedgehog (1991). In Sonic –probably the first video game I ever played – there was one thing that always got me. In the vertigo-inducing bonus stage, your goal was to reach the ‘chaos emerald’ at the centre of a maze. But the maze’s numerous exits, which you endeavoured with rising panic to avoid, were all emblazoned with the word ‘GOAL’. Why, my perplexed seven-year-old self asked, did all the exits say ‘GOAL’ even though they were emphatically bad? What was in the least bit ‘GOAL’-like about these terrifying immanences? My childhood geekery led me to the Westernised version of the game’s back story, which revealed that the villain of the piece, Dr. Robotnik, had designed the mazes as traps. These apparently nefarious exits, then, were but sweet blessed releases from these endless, timeless labyrinths. But that explanation didn’t satisfy me. Leaving aside the fact that the game explicitly rewards you with extra lives for staying in the maze as long as possible, what kind of fool would go chasing the ‘GOAL’ exits, ‘scored’ as with an all-too-simple nudge left on the control pad? What kind of absurd universe was this anyway? Curiously, this was the only aspect of the universe that troubled me. Liberating tiny animals from robot shells with a mutant blue hedgehog I accepted as perfectly logical; the ambiguous ‘GOAL’ just didn’t make sense.

> I later learned that the ‘GOAL’ anomaly was probably due to a mistranslation in the Japanese-designed game, which Western distributors tried (with limited success) to accommodate in their back story. Two things to say about this: one) it makes me like it even more; and two) while this doesn’t involve transcendent exits per se, it frames the ‘flatlanding’ limitations of immanent exits. That’s why it didn’t make sense: it rendered both ‘GOAL’ and chaos emerald (failure and success) as ultimately one and the same. This error in translation – this glitch, you might say – is the accidental ‘Sphere’ that demonstrates such is the case. By extension, there is no essential (‘transcendent’) difference between the GAME OVER screen and the end credits the player is treated to once beating the final boss. Both say ‘now play again – or do something else’. But neither, the ambiguous ‘GOAL’ suggests, offers transcendence. As the theologian wants the real beyond the real, so the transcendent player wants the game beyond the game, the virtual beyond the virtual; like the ‘Sphere’, to ‘leave the Plane’.

> Second: the infamous ‘stump joke’ in The Secret of Monkey Island. While the ambiguous ‘GOAL’ of Sonic is a kind of poetic fortuity, the Monkey Island developers – primarily writer Ron Gilbert, a legend in a certain vintage school of game design that prizes narrative and humour over adrenaline and point-scoring – played with and extended the conventions of gaming to an extent that remains visionary today. Monkey Island has many of the generic hallmarks of postmodern fiction and cinema: intensely metatextual and ironically self-aware, its protagonist breaks the fourth wall more often than Mario and Luigi break crudely-pixellated blocks. But it’s the ways in which the game self-reflexively plays with its own medium – significantly, its exits – that are truly innovative. For one thing, you can’t die, subverting what is perhaps the most common gaming trope of all (this is partly a dig at rival developer Sierra, whose adventure games are infamous for the frequency and ease with which players pop their avatarial clogs). But even more amazing is the ‘stump joke’. Like all PC games of the time, Monkey Island was published on a number of floppy disks (in this case, three) which had to be switched around when moving between game areas (that is, at various immanent exits). The stump joke comes early on in the game, when attempting to interact with a nondescript tree stump in a labyrinthine forest. The player is told to ‘Insert disk 22 and press button to continue’, the first of several requests for high-numbered non-existent disks. Eventually the game resumes as the protagonist says, with characteristic understatement, ‘I guess I can’t go down there. I’ll just have to skip that part of the game.’ Joke is: there is no ‘down there’.

> Simple enough, you might think. But while I figured there was something amiss with the ambiguous ‘GOAL’, the stump joke in Monkey Island – which I first played around the same time as Sonic – was a meta conundrum way beyond my understanding. I was desperate for it to mean something: for the ‘down there’ to exist. And I wasn’t alone. The ‘joke’ was too confusing for many players (many of them grown-ups, I should add), and it was removed from later versions of the game. As ‘A Square’ is obliged to return to Flatland and, in an ending Plato could have predicted, is considered a lunatic and is promptly incarcerated for the social good, so the stump joke was just too transcendent for 1990s gamers’ mores. But games – and gamers – have changed a lot since then. The faux-transcendence of the stump joke has given way to a player-driven pursuit of transcendence, that ‘slight upwards or downward motion’ which breaks the game’s syntax, revealing it – even if momentarily – as something other than it claims to be. The increasing complexity of virtual game worlds, and the concomitant impossibility of testing its every ‘slight upward and downward motion’, has inspired gamers to play the game against its grain until it breaks, finding the glitch that reveals ‘that part of the game’ – the world inside the stump – which we were never supposed to see.

> Hence, third: ‘Hidden Interiors World’, or ‘Heaven’, of 2005 title Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas. It is difficult to describe, to a non-gamer, the sense of awe I have experienced on entering the world of San Andreas: its vastness; its character; its endless complexity; and, above all, its absolute liberty. But this liberty, I am aware even within my awe, is an illusion. All gamers know this (though the moralising press might disagree), but only the transcendent gamer, ‘summon[ing] up the necessary volition’, can see it for themselves. Such a gamer reaches for ‘Heaven’. As one how-to video on YouTube puts it:‘The Universe of Hidden Interiors or Heaven refers to [a] “universe” […] placed high in the sky, far from the fly height limit. Once inside Heaven, the normal world of San Andreas disappears.’

> In crude materialistic (virtualistic?) terms, ‘Heaven’ is where San Andreas keeps its interior areas, probably to limit loading times when passing (immanently) between them and the main external area. But this prosaic explanation is much too ‘superficial’ to do justice to ‘slight […] upward motion’ and the vision it begets! It’s the sudden collapse of space and distance, the eerie silence, the solitude. It’s the fact you’re in on a secret, have seen something few others have seen (seen it from the insideas well as the outside). It’s also the tranquility, a surprisingly affecting counterpoint to a game-world defined by its constant movement, violence, and energy. That said, I have to concede that its revelation, such as it is, bears little comparison to that of ‘A Square’. The excitement of being somewhere phenomenologically elsewhere is tempered – or perhaps it is exaggerated – by the knowledge that this world is merely an accident of design; its transcendence not a ground, but a figure’s remainder. And that too is its pleasure. ‘Heaven’ is a place where nothing ever happens – but we dream about it anyway.

> Poet and critic Ben Lerner has written of his ‘hatred of poetry’; actually, a frustration at poetry’s inevitable imperfections, borne of an idealistic love for it. He recalls, in his childhood, ‘speaking a word whose meaning I didn’t know but about which I had some inkling’, locating in that ‘provisional’ sense the essence of poetry. Once a word was ‘mastered’, it ‘click[s]’, and is no longer poetry. ‘Remember how easily our games could break down or reform or redescribe reality?’ he asks. Games have their poetry: their transcendent exits, metaphoric apertures nestled deep within the metonymic totality of their worlds. For innocence and experience, for order and liberty, for squares and spheres, they are exits worth chasing.

~

Text: Calum Rodger

Image: Sonic the Hedgehog (SEGA, 1991)

#essay#video games#Calum Rodger#Ben Lerner#Sonic the Hedgehog#SEGA#special stage#poetry#virtual sublime#critical games studies#Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas#Monkey Island#joke#glitch#Edwin Abbott Abbott#Flatland

0 notes

Text

Reading Notes

Ian Bogost wrote a piece in the atlantic, here are some of the notes I took on my second reading, as in-line replies.

A longstanding dream: Video games will evolve into interactive stories, like the ones that play out fictionally on the Star Trek Holodeck. In this hypothetical future, players could interact with computerized characters as round as those in novels or films, making choices that would influence an ever-evolving plot. It would be like living in a novel, where the player’s actions would have as much of an influence on the story as they might in the real world.

Okay straight off the bat that seems a pretty specific definition of story, which requires:

complex characters

Player Influencing plot

“Living in a novel” (which I’ll take for meaning complex simulated environments)

It’s an almost impossible bar to reach, for cultural reasons as much as technical ones. One shortcut is an approach called environmental storytelling. Environmental stories invite players to discover and reconstruct a fixed story from the environment itself. Think of it as the novel wresting the real-time, first-person, 3-D graphics engine from the hands of the shooter game. In Disneyland’s Peter Pan’s Flight, for example, dioramas summarize the plot and setting of the film. In the 2007 game BioShock, recorded messages in an elaborate, Art Deco environment provide context for a story of a utopia’s fall. And in What Remains of Edith Finch, a new game about a girl piecing together a family curse, narration is accomplished through artifacts discovered in an old house.

Okay so environmental storytelling is seen as an attempt at holodecking b/c it allows for rich environments, while artifacts imply or relate the life histories of complex characters, and player has influence in the sense that they move the plot along.

The approach raises many questions. Are the resulting interactive stories really interactive, when all the player does is assemble something from parts?

I think you doing the assembly rather than having someone assemble something for you is still a meaningful difference.

Are they really stories, when they are really environments?

I think I can only answer this when I understand what your definition of story is.

And most of all, are they better stories than the more popular and proven ones in the cinema, on television, and in books?

On this measure, alas, the best interactive stories are still worse than even middling books and films.

I’m a little confused by this standard. In terms of storytelling, are games falling short of the holodeck, or falling short of books and movies? b/c they seem like different questions to me. The holodeck question is about whether games meet the specific criteria to become the dreamed-of interactive movie. If the question is whether they measure to books/films, it’s more about whether games have equivalent ways to express characters and events but not necessarily whether it matches up to a linear, player-involved, immersive environment standard.

In retrospect, it’s easy easy to blame old games like Doom and Duke Nukem for stimulating the fantasy of male adolescent power. But that choice was made less deliberately at the time. Real-time 3-D worlds are harder to create than it seems, especially on the relatively low-powered computers that first ran games like Doom in the early 1990s. It helped to empty them out as much as possible, with surfaces detailed by simple textures and objects kept to a minimum. In other words, the first 3-D games were designed to be empty so that they would run.

An empty space is most easily interpreted as one in which something went terribly wrong. Add a few monsters that a powerful player-dude can vanquish, and the first-person shooter is born. The lone, soldier-hero against the Nazis, or the hell spawn, or the aliens.

Those early assumptions vanished quickly into infrastructure, forgotten. As 3-D first-person games evolved, along with the engines that run them, visual verisimilitude improved more than other features. Entire hardware industries developed around the specialized co-processors used to render 3-D scenes.

Ok so games are kinda doing the complex simulated environments part?

Left less explored were the other aspects of realistic, physical environments. The inner thoughts and outward behavior of simulated people, for example, beyond the fact of their collision with other objects. The problem becomes increasingly intractable over time. Incremental improvements in visual fidelity make 3-D worlds seem more and more real. But those worlds feel even more incongruous when the people that inhabit them behave like animatronics and the environments work like Potemkin villages.

But failing at the complex interactive characters part. True. (Some interesting experiments by SpiritAI and the game Event[0] however.)

Worse yet, the very concept of a Holodeck-aspirational interactive story implies that the player should be able to exert agency upon the dramatic arc of the plot. The one serious effort to do this was an ambitious 2005 interactive drama called Façade, a one-act play with roughly the plot of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. It worked remarkably well—for a video game. But it was still easily undermined. One player, for example, pretended to be a zombie, saying nothing but “brains” until the game’s simulated couple threw him out.

Also failing at the plot-influencing part and emergent events part (but some interesting experiments -- blood and laurels, for instance).

Environmental storytelling offers a solution to this conundrum. Instead of trying to resolve the matter of simulated character and plot, the genre gives up on both, embracing scripted action instead.

In between bouts of combat in BioShock, for instance, the recordings players discover have no influence on the action of the game, except to color the interpretation of that action. The payoff, if that’s the right word for it, is a tepid reprimand against blind compliance, the very conceit the BioShock player would have to embrace to play the game in the first place.

True, this is what 3D games do. But I’d argue that other games give up on the fully simulated environment in order to resolve simulated characters and/or simulated plots. All three of these things are happening they’re just not happening in the same games.

In 2013, three developers who had worked on the BioShock series borrowed the environmental-storytelling technique and threw away both the shooting and the sci-fi fantasy. The result was Gone Home, a story game about a college-aged woman who returns home to a mysterious, empty mansion near Portland, Oregon. By reassembling the fragments found in this mansion, the player reconstructs the story of the main character’s sister and her journey to discover her sexual identity. The game was widely praised for breaking the mold of the first-person experience while also importing issues in identity politics into a medium known for its unwavering masculinity.

Feats, but relative ones. Writing about Gone Home upon its release, I called it the video-game equivalent of young-adult fiction. Hardly anything to be ashamed of, but maybe much nothing to praise, either. If the ultimate bar for meaning in games is set at teen fare, then perhaps they will remain stuck in a perpetual adolescence even if they escape the stereotypical dude-bro’s basement. Other paths are possible, and perhaps the most promising ones will bypass rather than resolve games’ youthful indiscretions.

I love Gone Home but I certainly don’t think it shows the limits of what can be achieved at all, even within this palette of techniques. So far it feels like this article is trying to point out the weaknesses of games trying to holodeck, but Gone Home never felt like an attempt to. It felt like it was trying to glean which storytelling techniques come naturally to games and explore them.

* * *

What Remains of Edith Finch both adopts and improves upon the model set by Gone Home. It, too, is about a young woman who returns home to a mysterious, abandoned house in the Pacific Northwest, where she discovers unexpected and dark secrets.

The titular Edith Finch is the youngest surviving member of the Finch family, Nordic immigrants who came to the Seattle area in the late 19th century. It is a family of legendary, cursed doom, an affliction that motivated emigration. But once they arrived on Orcas Island, fate treated the Finches no less severely—all its lineage has been doomed to die, and often in tragically unremarkable ways. Edith has just inherited the old family house from her mother, the latest victim of the curse.

As in Doom and BioShock and almost every other first-person game ever made, the emptiness of the environment becomes essential to its operation. 3-D games are settings as much as experiences—perhaps even more so. And the Finch estate is a remarkable setting, imagined and executed in intricate detail. This is a weird family, and the house has been stocked with handmade gewgaws and renovated improbably, coiling Dr. Seuss-like into the air. The game is cleverly structured as a series of a dozen or so narrative vignettes, in which Edith accesses prohibited parts of the unusual house, finally learning the individual fates of her forebears by means of the fragments they left behind—diaries, letters, recordings, and other mementos.

The result is aesthetically coherent, fusing the artistic sensibilities of Edward Gory, Isabel Allende, and Wes Anderson. The writing is good, an uncommon accomplishment in a video game. On the whole, there is nothing to fault in What Remains of Edith Finch. It’s a lovely little title with ambitions scaled to match their execution. Few will leave it unsatisfied.

And yet, the game is pregnant with an unanswered question: Why does this story need to be told as a video game?

(This sort of conjures up the idea that game designers sit down with a linear plot and attempt to holodeck it, which I feel is less and less of a thing)

The whole way through, I found myself wondering why I couldn’t experience Edith Finch as a traditional time-based narrative. Real-time rendering tools are as good as pre-rendered computer graphics these days, and little would have been compromised visually had the game been an animated film. Or even a live-action film. After all, most films are shot with green screens, the details added in postproduction. The story is entirely linear, and interacting with the environment only gets in the way, such as when a particularly dark hallway makes it unclear that the next scene is right around the corner.

One answer could be cinema envy. The game industry has long dreamed of overtaking Hollywood to become the “medium of the 21st century,” a concept now so retrograde that it could only satisfy an occupant of the 20th. But a more compelling answer is that something would be lost in flattening What Remains of Edith Finch into a linear experience.

Yep, I would agree with that.

The character vignettes take different forms, each keyed to a clever interpretation of the very idea of real-time 3-D modeling and interaction. In one case, the player takes on the role of different animals, recasting a familiar space in a new way. In another, the player moves a character through the Finch house, but inside a comic book, where it is rendered with cell-shading instead of conventional, simulated lighting. In yet another, the player encounters a character’s fantasy as a navigable space that must be managed alongside that of the humdrum workplace in which that fantasy took place.

Something would be lost in flattening most “walking sims” and narrative investigation games and that’s the experience of space itself, perhaps the most prized thing holodecking adds to stories (after all, if you want to participate in an ever evolving, player influenced story, you could do d&d instead).

These are remarkable accomplishments. But they are not feats of storytelling, at all. Rather, they are novel expressions of the capacities of a real-time 3-D engine.

I disagree. “novel expressions of the capacities of a real-time 3-D engine” are the “telling” part of storytelling.

The ability to render light and shadow, to model structure and turn it into obstacle, to trick the eye into believing a flat surface is a bookshelf or a cavern, and to allow the player to maneuver a camera through that environment, pretending that it its a character. Edith Finch is a story about a family, sure, but first it’s a device made of the conventions of 3-D gaming, one as weird and improvised as the Finch house in which the action takes place.

Such repurposing was already present in earlier environmental story-games, including Gone Home and Dear Esther, another important entry in the genre that prides itself on rejecting the “traditional mechanics” of first-person experience. For these games, the glory of refusing the player agency was part of the goal. So much so that their creators even embraced the derogatory name “walking simulator,” a sneer invented for them by their supposedly shooter-loving critics.

But walking simulators were always doomed to be a transitional form. The gag of a game with no gameplay might seem political at first, but it quickly devolves into conceptualism. What Remains of Edith Finch picks up the baton and designs a different race for it. At stake is not whether a game can tell a good story or even a better story than books or films or television. Rather, what it looks like when a game uses the materials of games to make those materials visible, operable, and beautiful.

Right, so it rejects holodecking and tries to convey character, plot and space according to its own language. This feels like saying games are bad at holodecking, not necessarily bad at stories.

* * *

Think of a a medium as the aesthetic form of common materials. Poetry aestheticizes language. Painting aestheticizes flatness and pigment. Photography does so for time. Film, for time and space. Architecture, for mass and void. Television, for economic leisure and domestic habit. Sure, yes, those media can and do tell stories. But the stories come later, built atop the medium’s foundations.

What are games good for, then? Players and creators have been mistaken in merely hoping that they might someday share the stage with books, films, and television, let alone to unseat them. To use games to tell stories is a fine goal, I suppose, but it’s also an unambitious one.

lol

Games are not a new, interactive medium for stories. Instead, games are the aesthetic form of everyday objects. Of ordinary life. Take a ball and a field: you get soccer. Take property-based wealth and the Depression: you get Monopoly. Take patterns of four contiguous squares and gravity: you get Tetris. Take ray tracing and reverse it to track projectiles: you get Doom. Games show players the unseen uses of ordinary materials.

And if I take a story, shake it up and scatted it all over an environment? Is that the aesthetic form of storytelling?

As the only mass medium that arose after postmodernism, it’s no surprise that those materials so often would be the stuff of games themselves. More often than not, games are about the conventions of games and the materials of games—at least in part. Texas Hold ’em is a game made out of Poker. Candy Crush is a game made out of Bejeweled. Gone Home is a game made out of BioShock.

The true accomplishment of What Remains of Edith Finch is that it invites players to abandon the dream of interactive storytelling at last.

This doesn’t make sense to me. You’ve made a good case that games can convey character and plot well through “novel expressions of the capacities of a real-time 3-D engine”, and you’ve made a case that environmental storytelling doesn’t achieve holodecking, but I’m not going to rule out that other techniques might.

Yes, sure, you can tell a story in a game. But what a lot of work that is, when it’s so much easier to watch television, or to read.

A greater ambition, which the game accomplishes more effectively anyway: to show the delightful curiosity that can be made when stories, games, comics, game engines, virtual environments—and anything else, for that matter—can be taken apart and put back together again unexpectedly.

To dream of the Holodeck is just to dream a complicated dream of the novel. If there is a future of games, let alone a future in which they discover their potential as a defining medium of an era, it will be one in which games abandon the dream of becoming narrative media and pursue the one they are already so good at: taking the tidy, ordinary world apart and putting it back together again in surprising, ghastly new ways.

But this sort of gets why games have stories at all, which is that they are necessities to explain and contextualise the weird things game engines produce. I’d argue that regardless of whether you feel game stories are as good as books, some “novel expressions of the capacities of a real-time 3-D engine” need narrative context to be understood and enjoyed by players. Rapture is less rapturous without its story.

5 notes

·

View notes