#their interests and ideologies overlap or at least complement each other

Note

I have to ask what drew vasco into falling in love with machete?

His snivelling runt ways were just that irresistable.

#no they were best friends first#it wasn't love at first sight#I think Vasco just gradually noticed that Machete is sincere and kindhearted and genuinely tries to be a good person#and it's hard not to appreciate that Vasco is known for having those qualities too his are just a lot more evident#he's an one person dog but when he gets attached to you he's fervently dedicated loyal caring and supportive#he's perceptive thoughtful and a good listener#sensible highly responsible and keeps his promises#does his part or dies trying even if no one is there to notice#he's learned knowledgeable and a lot more sharp-witted than people give him credit for and infodumps as a love language#their interests and ideologies overlap or at least complement each other#he has problems but really tries to do better and never takes any help he's given for granted#he always dresses well smells nice and has soft pettable fur#and he can be kind of funny and cute in his own dorky way#and Vasco sees how his presence continuously brings out the best qualities in him#and cherishes the fact he can be such a positive force in someone's life#answered#anonymous#Vaschete lore

278 notes

·

View notes

Note

Putting nostalgia aside, what in your opinion makes dramione greater than other Draco pairings? I love both equally personally, but I’d love to know as time has gone on, I now myself have a preference which i now gravitate towards on the basis of their“technicalities”.

So putting aside the nostalgia, what tropes, characteristics of each, do you find more fascinating or more unique in either pairing?

(Usual disclaimer that I'm a "ship and let ship" person and all fanfic portrayals of these fictional characters are valid, this is just a silly, long-winded opinion 😘)

Hmm, I don't think I would say it's "greater" (everything is subjective) than any other pairing, but if you're asking why dramione has remained my favorite, it's simply because I find them the most compelling. We get a lot of hermione in the books, sure, but as we're in harry's head for almost all of canon, i found myself interested in exploring her character and all its glory and flaws without the veil of harry's pov. I adore her intelligence, of course, and her capacity for kindness, but she can also be ruthless (keeping Skeeter in a jar, Marietta Edgecombe), unflinchingly pragmatic (her disdain for divination, wiping her parents' memories), and morally grey when it suits her interests (every book, y'all, every book she is breaking/bending rules with harry/ron).

I'm not going to even attempt to dig through my past asks because tumblr searches are terrible, but I've written before about Draco's unfinished and unsatisfying canon narrative. He is set up several times over to have a somewhat forgiving arc but ultimately it falls flat and it's a stupendous waste of potential for an on-page redemption. It makes him a fantastic character for fanfiction at least.

And so I prefer dramione for what it makes these two confront about themselves and each other. They have shared trauma, or at least overlapping trauma touchpoints, that can lend themselves to some gutwrenching conversations. A relationship, a friendship, fuck even earning the right to breathe in Hermione's vicinity is going to require a lot of soul-searching, apologizing, unlearning of hateful rhetoric and probably a fuckton of therapy for draco. I dont view dramione as opposites so much as complements and there's a vast potential for drama and angst and these two seem really intense in their desires to succeed in the world as very loyal, tightly wound, ambitious over-achievers.

I don't know honestly, it just makes me happy to think about them happy together. Put these two in some situations and let them kiss.

I adore drarry too of course, but harry and draco's animosity is often focused on draco confronting personal conflict/differences vs their ideological differences.

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gianluca Chimenti, Conceptual controversies at the boundaries between markets: the case of ridesharing, 23 Consumption, Markets & Cult 130 (2019)

Abstract

The drawing of boundaries has been deemed crucial for the shaping of markets. One type of such boundary is the boundary between markets to distinguish alternative market versions in all their heterogeneity. The so-called sharing economy – largely enabled by the current wave of digitalisation – represents a domain comprising many overlapping and contested market boundaries. This article explores how different conceptualisations of the sharing economy prompt strategic efforts to establish alternative market boundaries for the purpose of legitimising specific practices and to advance political and ideological ambitions. It also shows how this “boundary work” reinforces controversies when different processes of drawing boundaries interfere with and potentially threaten each other. Drawing on constructivist market studies, particularly the notions of framing and performation struggles, this article compares three dominating ridesharing platforms in Sweden: Uber, Skjutsgruppen and Heetch.

Introduction

There is great diversity among activities as well as baffling boundaries drawn by participants. TaskRabbit, an “errands” site, is often included, but Mechanical Turk (Amazon’s online labor market) is not. Airbnb is practically synonymous with the sharing economy, but traditional bed and breakfasts are left out. Lyft, a ride service company, claims to be in, but Uber, another ride service company, does not. Shouldn’t public libraries and parks count? (Schor, October 2014)

This quote by Schor about the sharing economy exemplifies the more general observation that nascent markets are often ambiguous, not least in terms of their boundaries (Callon, Lascoumes, and Barthe 2009). The so-called sharing economy is widely considered to be such a nascent market whose lack of clarity has generated conflicting practices and “matters of concern” (Geiger et al. 2014). For example critics have lamented how the adoption of feel-good rhetoric by commercial actors disguises an organisational spirit of predatory avarice (Sundararajan 2016). This “sharewashing” (Belk 2016) has produced several partially overlapping market concepts that nonetheless suggest quite different market boundaries: collaborative consumption (Botsman and Rogers 2010), commons-based peer production (Benkler 2004), access-based economy (Bardhi and Eckhardt 2012) or the gift economy (Mauss 2002), to name a few. In fact, there is burgeoning literature vividly contesting various attempts to demarcate what the sharing economy represents and how it is organised (Dredge and Gyimóthy 2015).

While the existence of multiple viewpoints on a single polysemic concept is often inevitable in emerging and therefore ambiguous environments, it also raises questions about the practical incompatibilities that may result from such unclear market boundaries (Frankel 2018). There is a widespread belief among social scientists that without a commonsensical understanding of the sharing economy, market actors will experience difficulties in sharing goods and services (Frenken and Schor 2017). Prominent marketing pundits have similarly highlighted the importance of market boundaries as a “basic foundation” for the analysis of competition (Buzzell 1999, 61). The issue of market boundaries is also central to any regulatory ambitions that governments may have concerning markets (Christophers 2015). A case in point is the recent report by the European Commission (Codagnone, Biagi, and Abadie 2016) stressing the need for a joint policy initiative concerning the sharing economy due to fragmented national regulations.1

While the sharing of goods and services is likely as old as mankind (Sahlins 1972), ICT-enabled sharing has triggered the recent rapid growth of the sharing economy. These technologies have afforded increased use of underutilised resources and widened the potential circle of sharers beyond kinship. Internet and smartphone technologies today allow for unprecedented matching of supply and demand without the use of traditional intermediaries, thereby reducing information asymmetries and other transaction costs (Rifkin 2001).

Questions of controversies in digitalised markets are thus inseparable from questions of market boundaries and the discussions arising when they coincide, yet the former has received much more scholarly attention than the latter. This study investigates how controversies concerning how to conceptualise a certain type of market – in this case “ridesharing” – contribute to the shape of that market. More specifically, it examines how different conceptualisations of the sharing economy prompt strategic efforts to establish market boundaries and how these boundaries may interfere with one another.

To follow this boundary work, one specific sharing market will be examined, namely the market for ridesharing in Sweden. By locating the inquiry in the Swedish context, this article studies a market that has been controversial from its early stages, not least due to the lack of regulatory frameworks. The Swedish ridesharing market further represents a suitable case due to the simultaneous presence of several more or less controversial platforms. A comparative study of three ridesharing ventures – Uber, Skjutsgruppen and Heetch – reveals the heterogeneity of ridesharing actors and also their efforts to reach consensus (or not) concerning the boundaries of this controversial market.

This complex state of affairs closely links to Callon and Muniesa’s (2005) characterisation of markets as calculative collective spaces that represent sites of confrontation and power struggles. Following Callon and Muniesa, this article conceptualises the sharing economy as a space in which multiple actors with diverse interests advance different political and economic agendas. The polysemic character of the “sharing economy” is explicitly used (and abused) by the actors, thereby perpetuating dialectic processes of bargaining over alternative designations. Given the heterogeneity of actors involved in framing the ridesharing market, including policy makers, entrepreneurs, investors, and incumbent transport operators, it is hardly surprising that they express radically opposing views concerning what this market “should be”. This is directly linked to the “pragmatic ambiguity” of the term (cf. Giroux 2006), in that a set of diverse phenomena is subsumed under a common sharing fiction, allowing a high degree of pluralism while sustaining a semblance of unity.

A small number of previous studies have theorised the consequences of controversies pertaining to market shaping (Giesler 2008; Venturini 2010; Caprotti 2012; Chakrabarti and Mason 2014; Blanchet and Depeyre 2016). For example, Chakrabarti and Mason (2014) demonstrate how different actors in a BoP community (farmers, villagers, researchers, trade collectives) negotiate consensus to create a market through contested and iterative framing processes. Caprotti (2012) discusses how definitional debates around the market of cleantech are pertinent to its emergence. More recent contributions discuss the multifaceted roles of boundaries and their political contingency across empirical phenomena (Fernandez and Figueiredo 2018). However, there is an unexpected dearth of research examining the role of controversies in shaping and challenging market boundaries. Moreover, how and for what purposes market boundaries are drawn in light of the ongoing digitalisation of markets merits further attention.

Based on the argument that markets are continuously re-emerging rather than merely expanding (Callon 1998), the focus of this study is directed towards the practical implications of realising and maintaining a “unified identity” in a field of disagreement (Giroux 2006). Drawing on previous work in constructivist market studies (Rinallo and Golfetto 2006; Araujo, Finch, and Kjellberg 2010; Christophers 2015; Onyas and Ryan 2015), particularly the concepts of framing (Callon 1998) and performation struggles (Callon 2007), the aim of the article is to extend our understanding of how conceptual controversies contribute to market shaping (Blanchet and Depeyre 2016). By employing a socio-material view on markets as plastic entities (Nenonen et al. 2014), the key theoretical contribution opens up a “space of debate and critique on both the appropriate scope of markets as well as the role of marketing in making and operating markets” (Araujo and Pels 2015, 451). The analysis complements prior research focused on marketisation (Çalışkan and Callon 2010) by following the construction of market boundaries and the work required to maintain their often mutually conflicting qualities.

The article proceeds as follows: First, I review the literature on the roles of market boundaries and relate this to performation struggles in low-consensus environments. Second, I flesh out the methodological approach by outlining how the empirical enquiry was conducted. Third, I account for the three dominant sharing economy concepts before describing each of the three studied ridesharing ventures in detail. Fourth, I discuss various struggles that have emerged in response to the ongoing boundary work concerning ridesharing in order to theorise the role of conceptual controversies in markets. Finally, I offer three conclusions and make two specific suggestions for further research.

Framing market boundaries

There are no such things as “natural” market boundaries (Dumez and Jeunemaitre 2010). Instead, markets are constantly subject to boundary work by a host of different actors, including, but not limited to, buyers and sellers, regulators, market analysts, and civil society organisations (Abbott 1995; Fligstein 1996; Ellis et al. 2010; Finch and Geiger 2010). While it is well known that there is no correct way to delimit a market (Day 1981), these actors’ efforts may occasionally result in market boundaries that for all practical purposes appear to be naturally given, at least for a time. Such periods of relative stability and agreement, however, should not distract observers from the fact that the work of maintaining market boundaries is never really over (Callon 1998).

In many contemporary markets, market boundaries are repeatedly and overtly “challenged, crossed and even transgressed” (Fernandez and Figueiredo 2018, 295). The resulting blurry and shifting market boundaries present challenges to both marketers and academics. For marketers, they complicate decisions concerning how and where to draw boundaries between more or less similar offerings to identify the competition (Callon, Méadel, and Rabeharisoa 2002). Previous research highlights this complexity in the context of product categories (Rosa et al. 1999), market categories (Navis and Glynn 2010), music genres (Anand and Peterson 2000) and geographical boundaries (Clark 1994). As discussed by Stigzelius et al. (2018) the conceptual blurriness also affects academic discussions, where conceptions of markets vary significantly across different traditions and in some cases make meaningful discussions on the topic difficult. Moreover, practical and academic conceptions of markets and market boundaries are to some extent communicating vessels. The resulting confluence of interpretations, concerns and conceptualisations creates an ambiguous space, “where the delimitation-bifurcation between the economy and politics is constantly being debated and played out” (Callon 2010, 165).

This socio-political dimension of market boundaries as sites of differences and commonalities hints at the malleability of markets. Once established, market boundaries remain debatable and when controversies emerge, “strategies aiming at changing the boundaries develop, and strategies at maintaining them develop in response” (Dumez and Jeunemaitre 2010, 153). Continuous boundary work is thus crucial in the making and unmaking of markets, and contributes to temporarily establishing which parameters are relevant for market exchange (Callon and Muniesa 2005). Given the multiplicity and heterogeneity of actors that engage in such work, Callon and Muniesa (2005) consider markets as multifaceted, value-laden “spaces of calculability” in which actors constantly seek to de-stabilise existing boundaries in “a game of strategic interaction” (Dumez and Jeunemaitre 2010, 156).

Drawing on Goffman’s (1974) frame analysis, Callon (1998) proposed the concepts of framing and overflowing to address this continuous process of defining and redefining markets. While framing reflects the process of stabilising market boundaries by temporarily putting the outside world in brackets to render economic exchange possible, overflowing represents its necessary corollary, namely that all entities included in such framing efforts at the same time constitute potential conduits to the outside world. Strathern (1996) similarly highlights the role of framing to “cut the network” to temporarily locate elements considered irrelevant to a particular market exchange outside the frame – and vice versa. Framing thus creates a paradox; it acts both as a divider and a connector between markets, creating the conditions for things to interfere. Nevertheless, Callon (1998, 17) argues that “it is owing to this framing that the market can exist and that distinct agents and distinct goods can be brought into play.” This process of framing and overflowing suggests that the boundaries between different (versions of) markets – such as between the sharing economy, the collaborative economy, the gig economy, etc. – cannot be entirely clear cut. A central implication for marketers is that there is neither a single nor a permanent way to frame a market. Moreover, since market boundaries per definition are leaky, framing is often a contested activity (Holm and Nielsen 2007), as is illustrated by debates concerning commercial organisations operating under the guise of the sharing economy (Sundararajan 2016).

The implied state of flux regarding market boundaries raises questions concerning what to make of legal market boundaries. Instead of merely “setting the legal stage”, Christophers (2015, 137) stresses that the drawing of legal boundaries, “can be highly and visibly material to market outcomes.” Araujo and Kjellberg (2015) illustrate this potential import of legal boundaries by showing how the US Airline Deregulation on the one hand opened the market to entrants and on the other triggered incumbents to reframe exchanges in the market by introducing Frequent Flyer Programs. Hence, while conceptual market boundaries may appear to be abstract and fluid, they can also be turned into concrete realities.

It seems clear that framing efforts can generate multiplicity in markets. Different concepts prompt actors to employ different framing strategies to stabilise particular boundaries. Such theory-induced change efforts may intentionally or unintentionally produce partially overlapping market boundaries (Araujo, Finch, and Kjellberg 2010). Such overlaps may, however, result in delicate situations if the boundaries are based on mutually incompatible concepts, which in turn can bring about controversies (Frankel 2018). To better understand the roles of boundaries in controversial market contexts, it is important to examine how different market boundaries may co-exist and co-evolve. This raises further questions about how specific framing efforts can be brought to bear in the presence of competing efforts. In order to address this, I use the notion of performation struggles (Callon 2007) to introduce controversies and disagreements in processes of continuous market framing. Combining the notions of framing and overflowing with performation struggles highlights the precariousness of redrawing established boundaries within a highly contested environment.

Performation struggles at the boundaries between markets

Ellis et al. (2010) show how market boundaries are shaped by the complex interplay of theory and practice when practitioners (wittingly or not) perform particular concepts. The sharing economy and its related concepts provide great examples of the practical relevance of market concepts. Depending on which conception is used to frame the sharing market a practice may pass as either altruistic sharing or “sharewashing,” second-hand flea markets may be included or excluded, and gifting, commodity exchange and sharing may or may not be used interchangeably (Belk 2010, 2014; Frenken and Schor 2017). Market concepts also provide guidelines and inspiration for practitioners on how to act when operating under the umbrella of “collaborative economy”, for instance (see Botsman and Rogers 2010). In this sense, specific market concepts carry statements about markets in that they suggest alternative ways of acting in relation to particular sharing practices.

Callon (2007) argues that the successful interplay between a market concept and market practice requires a specific environment, or conditions of felicity (cf. Austin 1962). This required environment cannot be entirely known in advance and differs across situations, and is thus revealed once a concept is employed as part of a framing effort. MacKenzie’s (2003) seminal study of the relation between the Black–Scholes model and actual option markets, for example, showed how the “required environment” was crucial in realising a market aligned with the model. The creation of such environments, however, is often disturbed by the existence of competing ideas about markets, which may lead to “dynamic confrontations” among actors (D’adderio and Pollock 2014, 1837).

In light of the tensions over competing sharing concepts and their inherent statements about markets, the development of the sharing economy represents what Callon (2007, 330) calls a performation struggle involving conflicting processes of adjustments of statements and their associated environments. Performation struggles arise when processes to establish alternative market boundaries interfere with and potentially threaten each other. They render visible the overflowing, the “misfires” and the political stakes inevitably generated by market framing (Callon 2010). An example of this is a recent debate centred around Uber’s framing efforts to position itself as digital tech-company in 2017. Uber has long operated as an “information society service” which classifies the platform as a digital match-maker between drivers and passengers. This subtle, self-proclaimed classification has allowed Uber to temporarily circumvent national transport regulations with little responsibilities for worker protection and other related issues. This attempt to adjust the (legal) boundaries was eventually rejected due to conflicting conceptions of “ridesharing” between Uber and the regulators. The highest court in Europe considered Uber’s practices to have more in common with taxi operators than tech-companies, and thus decided that Uber must fall under the legislation for transportation companies (The New York Times, December 20, 2017).

Kjellberg and Helgesson (2006) conceive of these processes of adjustments as chains of translations by which ideas about markets are both reified (made concrete in practice) and abstracted (transformed into theoretical concepts). This double-edged character of boundary work can be highly relevant for some actors, such as regulators and competition authorities when they assess legality. It can also be relevant for businesses when attempting to capitalise on the vagueness of boundaries by operating as free-riders under a popular sharing concept. Performation struggles thus provide a suitable vantage point to examine the productive and political contingency of boundaries in “really existing markets”, as they make visible the efforts to realise various versions of market concepts in parallel.

It should be clear that the concept of framing concerns efforts to enact boundaries that allow particular economised exchanges to occur, while performation struggles highlight the political complexities arising in situations where market concepts are put to productive use (Callon 2007; Ellis et al. 2010). Combining the two allows us to move away from the often-unrewarding discussions about the truthfulness of market concepts (e.g. “is it really sharing?”) and instead attend to their concrete effects on mundane markets. Based on these starting points, I seek to explore how multiple boundary arrangements and struggles to perform the sharing economy arise in the presence of competing market concepts. So, how can such an exploration be conducted? The next section outlines the chosen methodological approach – an Actor-Network Theory inspired framework for the study of controversies (Venturini 2010).

Following the shaping of market boundaries, notes on methods

In order to generate a thick description of the Swedish ridesharing market, two primary methods were utilised: First, I compiled a mixed-source database comprising a wide range of texts (promotion materials, news articles, legal documents, etc). Second, I conducted ethnographic fieldwork including participant observation and interviews with representatives of three selected ridesharing ventures.

By focusing on a single market “in the making” – ridesharing in Sweden – I was able to follow the actors (Latour 1987) and their relationships beyond the selected case organisations (e.g. to local transportation authorities and tax agencies). My attention was initially caught by several instances of contestation in ridesharing markets across Europe, which prompted me to investigate this further in the Swedish context. To assess the empirical suitability for a controversy study in the Swedish ridesharing market, I used Latour’s cartography of controversies and employed three principles: “hotness”, multiplicity and topicality (medialab.sciences-po.fr).

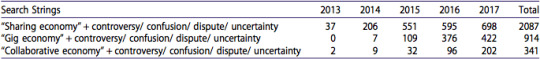

First, I sought out empirical accounts of “hot” situations, in which, “everything becomes controversial: the identification of intermediaries and overflows, the distribution of source and target agents, the way effects are measured” (Callon 1998, 260). Typical traits of hot markets are the complex web of issues being raised, the vivid disagreements between stakeholders, and the lack of accepted demarcations between matters of science, law, economy and society. Second, I mapped out a range of diverse initiatives aiming to establish or challenge a ridesharing market in Sweden. This revealed the multiplicity of actors and concerns involved in ongoing controversies (Latour 2004), including regulators, users, platform providers, journalists, activist groups, consultancies and various public authorities (i.e. city councils, municipalities and county councils). Third, Venturini (2010) encourages focusing on controversies in contemporary discourses. To assess the topicality of the Swedish debate, I consulted a database retrieved from Dow Jones Factiva comprised of press releases, academic journals, blog posts, web news and newspapers. Table 1 clearly illustrates the rising attention to and growing debate intensity concerning sharing economy concepts since 2013. This topicality allowed me to trace disputes in detail as they unfolded across various outlets.

Table 1. Summary Factiva search results, number of texts per year.

The research followed an abductive process of systematically combining information about the selected cases with conceptual insights concerning framing and performation struggles (Dubois and Gadde 2002). The case selection was theoretically driven (Davies 2012). Specifically, I looked for cases that: (a) were explicitly positioned within the Swedish ridesharing market, (b) had generated a reasonably-sized user base in Sweden and, (c) had diverging operational approaches. This resulted in a comparative design to study three ridesharing ventures – Uber, Heetch and Skjutsgruppen. The selected cases are the largest ridesharing platforms in Sweden and vary in terms of their respective approach to ridesharing.

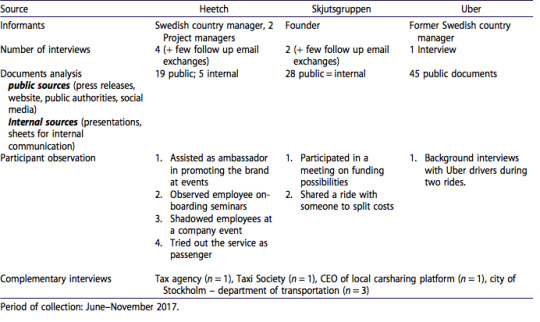

The fieldwork stretched over a period of five months (June–October, 2017). Echoing the literature on framing and performation, I sought to identify various activities geared towards shaping the market’s boundaries (Ellis et al. 2010). Participant observations, which are inherently multimethod, provided numerous opportunities for interviews and shadowing. Most interviews were semi-structured, transcribed verbatim and subsequently coded using the NVivo qualitative analysis software. Interviews included 8 informants across the three cases and took place in person, while a few follow-up interviews were arranged via email, Skype or phone. The initial phase of formal interviews was followed by active participation across a variety of activities such as meetings, promotion campaigns and business events. For example, as part of a marketing campaign I volunteered as “brand ambassador” for one of the organisations at a local event. A central task was to provide information about the services to potential ride-sharers, while raising brand awareness through games and merchandising. The resulting conversations were captured in shorthand jottings using a smart phone. First-hand observations moreover provided insights into how the employees themselves discussed different sharing concepts in situ. To better understand the different approaches of each case, I have tested all services myself by sharing rides to various places in Sweden.

This rather non-linear process was eventually complemented with secondary data sources retrieved from online platforms and in-house documents. The online fieldwork was conducted across a variety of social media platforms, including Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. In addition, local podcasts, radio shows, blogs, company websites and mobile applications offered detailed insights into their differences and commonalities. Lastly, by following the debates in news outlets and public position papers, I noted several cases of resentment among platform owners, regulators and journalists. For example, as we will see in the following sections, platform owners published debate articles in national newspapers to take an explicit stance against one another. Similarly, since Heetch capitalises on an ill-defined legal system for Swedish ridesharing, incumbent taxi operators publicly admit their desperation over vestigial regulatory frameworks. The resulting debates provided additional leads to conduct interviews with other involved stakeholders, including representatives from the city of Stockholm and regulators (see Table 2 attached for more details). The final dataset is therefore comprised of various formats: downloaded texts, field notes, pictures, audio files and social media communications.

Table 2. Description of empirical sources.

The analysis proceeded as follows: based on the insights from the literature on framing and performation, a theoretical understanding of boundary work was derived to guide the initial round of data assessment. This was followed by an in-depth study of each case generating visual graphs, timelines and maps to identify parallels and emerging patterns. By combining insights from observations, interviews and selected documents, I first fleshed out the most apparent efforts to establish alternative market boundaries across the cases. The individual boundary work was then categorised into clusters by iteratively revisiting collected information and by following ongoing initiatives as they unfolded. Given the topicality, occasional follow-up meetings with informants played a central role in the abductive process, particularly due to continuing changes in the market. The empirical accounts were subsequently compared with dominating sharing economy concepts in extant literature to identify links between theory and practice. Discrepancies and confirmations were noted in a spreadsheet to guide me in writing case narratives and conceptual conclusions.

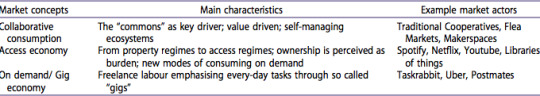

Multiple attempts to draw conceptual boundaries around the sharing economy

The sharing economy represents a low consensus paradigm encompassing a great wealth of concepts hybridising different practices and ideals. While these hybrid forms of economic organising are certainly not unprecedented – markets in early stages of formation are often “impure” – the blurring of conceptual market boundaries and the confusion they engender, is arguably more intense in the sharing economy than in mature markets (Arvidsson 2018). Disciplines as diverse as cultural theory, environmental economics, social anthropology and consumer behaviour attempt to frame the sharing economy on the basis of their respective understanding, turning the sharing economy literature into a conceptual maze (Dredge and Gyimóthy 2015). In the words of Frenken and Schor (2017, 4), “the confusion about the definition of the sharing economy is self-propelling due to the performativity of the term itself.” Central to this confusion is the engagement of many different types of actors in defining the sharing economy, including competitors, authorities, public press and academics. While the resulting bricolage of boundary work is quite bewildering at first, it is possible to discern three major alternative market conceptions (see Table 3).

Table 3. Alternative conceptions of the sharing economy.

First, while the concept of collaborative consumption was initially coined to describe mundane consumption practices (Felson and Spaeth 1978), it has been popularised as a concept that advocates tapping into idle capacity of underutilised assets. Responding to the digitalisation of markets and the rapid change of consumer attributes (e.g. informed, connected, purpose-driven), collaborative consumption represents, “traditional sharing, bartering, lending, trading, renting, gifting, and swapping, redefined through technology and peer communities” (Botsman and Rogers 2010; xv). This concept thus closely links to Tönnies’ (1887) notion of Gemeinschaft (as opposed to Gesellschaft), advocating the idea of joint governance and communal co-creation, wherein organisational hierarchies are malleable and changed according to degree of expertise (cf. Ostrom 2015). According to Benkler (2004), decision-making processes in the collaborative economy are based on the principles of meritocratic ideals, decentralised governance and self-organisation. There is no formal assessment of knowledge and skills by a single authority since the community collectively validates suitability along the formation process.

Second, the rise of online streaming platforms such as Netflix and Spotify diffused the concept of access economy, which has been adopted by a variety of industries, ranging from car sharing (Bardhi and Eckhardt 2012) to art collection (Chen 2008). In “the Age of Access” Rifkin (2001) refers to this new form of economic exchange as market transactions wherein no transfer of ownership occurs, while platforms allow individuals to receive temporary rights to use on – or offline commodities at their convenience. This usage-based approach is characterised by a servitisation of markets and the desire to live without the “burden” of ownership. It also aims at emancipating consumers from the old tradition to express social status through assets. Empirically, due to the low utilisation rate of cars, it is hardly surprising that the automobile industry has been particularly proactive in experimenting with access-based business models (e.g. BMW’s car sharing DriveNow).

Finally, and closely related, is the concept of on-demand or gig-economy, which designates pure service platforms that leverage the spare time, knowledge and skills of peers. Here, short-term labour is matched through decentralised networks of workers on specific platforms in order to supply local and temporary demand for menial tasks, such as furniture assembly, household chores, or fast urban courier services. Individuals provide these so-called gigs to attain additional income or simply find joy in altruistic work (Hamari, Sjöklint, and Ukkonen 2015). Essentially, services are provided by freelance workers or “micro-entrepreneurs” in exchange for remuneration. Herein, the gigs can be reciprocated either monetarily or through other comparable services. Workers can then add gigs to their portfolio and build their reputations (Schor 2014). Thus, central to the gig-economy is the role of rating systems that help facilitate trust for unprofessional workers.

In line with Schor’s introductory statement, the fine lines between these conceptions are unclear to many, and they are often used interchangeably across sharing markets. As we will see in the next section, these conceptions are also consequential for the boundary work that practitioners engage in to demarcate their sharing initiatives from others.

Boundaries at work – market concepts in action

How are these different market concepts employed as part of and in response to ongoing controversies? Each of the following cases highlights efforts to establish specific market boundaries for ridesharing in Sweden that challenge the boundaries drawn by competitors.

Uber – attempts to realise a purist marketplace

Uber entered the Swedish ridesharing market in 2014 with the intention of become the leading platform for professional ridesharing. It has launched services in Sweden’s two largest cities, Gothenburg and Stockholm. Profit and growth are central in Uber’s mission to become the market leader: Uber charges a 25% commission for each ride – the highest in the market – and the company has received multiple rounds of venture capital over the last five years (crunchbase.com).

The Uber case offers interesting insights into framing, overflowing and the shaping of market boundaries, especially due to the company’s repeated infringements on (explicit and implicit) regulatory boundaries, e.g. the case of UberPop. The business model is designed to match peers that either seek commercial work as chauffeurs or seek to hail professional rides. As such, Uber is akin to gig-economy platforms in other markets such as UrbanSitter (nanny service), Postmates (logistics platform) and Instacart (grocery delivery), which all operate on the basis of short term “gigs”. On its website, Uber constructs a professional image to portray the platform as a qualified ridesharing service provider. Promissory statements are used to signal efficiency, reliability and professionalism:

Your ride, On demand. Whether you’re headed to work […] or out of town, Uber connects you with a reliable ride in minutes. One tap, and a car comes directly to you. Your driver knows exactly where to go. (uber.com)

The strategy to build a reputation as a reliable taxi alternative has borne fruit. While the Swedish ridesharing market is still in its infancy, Uber clearly dominates urban ridesharing by any economic measure. For example, according to the country manager, Uber Sweden has circa 1500 drivers and 600,000 registered users of which 100,000 travel at least once per month. Interestingly, its success can be largely attributed to the recruitment of former taxi drivers, as monetary incentives represent the foremost reason to switch operator:

Forget about the high commission. The Uber app matches supply and demand much more efficiently than the Taxi app, or actually any other ridesharing competitor. This allows me to always keep rolling and make more money per shift than elsewhere. (Uber driver, interview October 2017)

By all appearances, Uber performs a version of the on-demand conception discussed above, which includes algorithmic surge pricing and the employment of cutting-edge technology (Uber’s legal name is in fact Uber Technologies Inc.). This is inter alia evident in the mobile app, which is very well-developed for both users and drivers. Drivers can track weekly and daily earnings at a glance, while users receive real-time information on the whereabouts of the drivers. To further resemble a marketplace for serious business, Uber seeks to attract service-minded drivers with a “commercial libido” prone to economic avarice:

Got a car? Turn it into a money machine. The city is buzzing and Uber makes it easy for you to cash in on the action. […] Earn money on your own terms. Drive full-or part-time, Uber gives you the flexibility to work as much or as little you want. (uber.com)

This reminds of Pollock and Williams’s (2010) postulate that markets are “made durable” by promissory work and convincing framing. A market studies reading of this promissory framing foregrounds the rhetorical work undertaken to “cut the network” to alternative ridesharing initiatives. The discursive positioning thus highlights a perlocutionary effect, i.e. the effect of persuading and convincing the reader of Uber’s differences.

The semblance of professionalism is further evident in the diversity of services, such as UberX, UberBlack, UberXL and UberLux. This diversification positions the platform as a professional mediator between supply and demand, and allows it to cater to a larger share of potential customers. This is closely linked to Uber’s efforts to position the platform vis-à-vis incumbent taxi operators, which also hints at the slipperiness of drawing precise market boundaries (Finch and Geiger 2010). In my dialogues with Uber drivers, I identified a degree of “porosity” in the boundaries between ridesharing and taxi, as Uber strongly mimics best practices found in established taxi schemes. Most pointedly, all of the interviewed Uber drivers used the term “taxi” interchangeably for both established taxi services and novel ridesharing platforms, even when referring to Uber itself. Uber drivers also adopt a certain “street behaviour” from incumbents; like taxis, Uber drivers circulate busy blocks and wait near crowded events to “snatch” customers without being hailed via the app. This might derive from the fact that many Uber drivers previously worked for one of the local taxi companies. In fact, Uber drivers explained to me how convenient it is to use apps from various platforms in parallel (ridesharing and taxi) to increase the number of gigs per shift. I also noticed a degree of detachment between drivers and the Uber brand, in that the drivers do not relate to Uber as much as they do to the benefits of working via Uber. Their motivation to use Uber is typically profit, thus mirroring the official Uber position.

The informants adopt business lingo loaded with market rhetoric when they stress the importance of “liquidity”. This represents arguably the most important KPI to measure whether the number of drivers available can meet the demand for rides at any given time (liquidity is here referred to as critical mass, rather than financial liquidity). Uber thus invests heavily to recruit drivers when entering a new Swedish city in order to sustain a high level of liquidity. Hence, new market entries typically come at a high cost for Uber to provide a strong presence on the streets (and in the app).

Lastly, and contrasting the other two cases in this study, it is hard to identify any effort to foster a (digital) community through, for instance, participatory practices or social events. However, responding to negative portrayals of Uber as “pseudo-sharing” (Belk 2014), Uber recently launched UberPool in an attempt to legitimise its positioning within the ridesharing market. UberPool matches passengers with already existing rides in a given direction (similar to Skjutsgruppen, below). While the on-demand conception still dominates the Uber-version of ridesharing, alternative conceptions are being tested.

Skjutsgruppen – attempts to realise a collaborative approach

Skjutsgruppen was founded in 2007 as a self-organising initiative through Facebook. Once a side project, it has turned into a non-profit organisation that operates across Sweden. The main intention is to make daily commutes affordable and long-distance travel more sustainable and fun. Skjutsgruppen is largely funded by participants and volunteers who collectively run the platform. Via the free membership, individual consumers can either find already scheduled journeys to join or advertise trips and share the cost of travel. This clearly contrasts on-demand services that (intentionally) operate akin to established taxi services. Rides are not hailed in the traditional sense but rather carefully planned and booked in advance to match travellers with the same destination.

The collaborative concept is fostered by a deep-rooted culture of civil activism. In conjunction with campaigns and official “Ride Sharing Days”,2 Skjutsgruppen’s founder travels across the nation to educate potential ride sharers and local authorities about the collaborative concept Skjutsgruppen stands for. The campaigns also aim to discourage single-occupancy car rides by explaining how ridesharing initiatives can be built in a self-organising manner. Campaigning venues are manifold and include sharing workshops (e.g. Ouishare3), political congresses (e.g. Almedalen4), hackathons (e.g. Civictech-Sweden5) and local radio channels (e.g. Sveriges Radio P4 Göteborg6). Most media appearances result from invitations by media platforms that support the collaborative concept that Skjutsgruppen stand for – an “earned” attention for Skjutsgruppen so to speak.

As such, Skjutsgruppen has evolved into Sweden’s largest ridesharing movement counting 70,000 members, while explicitly rejecting any association with profit-driven marketplaces:

We are a movement, which for us is both a wordplay, in that we are moving forward, but also an ideological framework. Everyone in the community has exactly the same freedom and opportunity to contribute. (skjutsgruppen.nu)

According to the founder, the driving force behind this movement stems from a culturally entrenched belief in the potential of collaborative and civil societies. In Sweden, the first major wave of popular movements emerged at the end of the twentieth century, ultimately paving the way for strong trade unions and consumer cooperatives (Wijkström 2007). Inspired by the temperance movement, the free church movement, and the labour movement, Skjutsgruppen advocates democratic values such as participatory governance, solidarity and reciprocal partnership. In fact, the founder himself provided me with a historical outline on this subject and appeared very well informed about Swedish activist movements. Combing this idealistic stance with ridesharing has resulted in several awards for his civil engagement, including the Civil Society Award in 2013.

This commitment to preserve the Swedish civil movement tradition hints at the boundary work necessary to dissociate other versions of ridesharing such as Uber’s for-profit platform. The efforts to demarcate Skjutsgruppen from other ridesharing platforms become even clearer in its dialectical stance towards competitors, as in this excerpt from an op-ed piece:

Imagine the public press would constantly refer to grilled steak as banana, it would probably not be accepted by the reader. Likewise, you should not mix up taxi with ridesharing. […] The municipalities we work with know what true ridesharing means. The tax agency knows it as well. (Göteborgs-Posten, May 14, 2016)

This statement clearly aims to convey Skjutsgruppen’s “otherness” and to highlight the lack of semantic sensibility among other ridesharing actors when relating to different sharing economy concepts.

Another dimension illustrating Skjutsgruppen’s otherness pertains to trust. As pointed out by Belk (2010, 717) “Sharing, whether with our parents, children, siblings, life partners, friends, co-workers, or neighbours, goes hand in hand with trust and bonding.” Here, Skjutsgruppen’s founder has sought to redesign the platform to shift from contemporary trust conceptions such as “trust-in-institutions” (cf. Fligstein 1996), towards new forms of decentralised “trust-in-peers”. That is, rather than creating a strong institutional brand that vouches for the trustworthiness of individuals, Skjutsgruppen encourages the formation of a lateral trust network among its members through which performance is assessed collectively. For example, unlike Uber, Skjutsgruppen does not use a review function to assess drivers’ performances, since “reviews commodify humans,” as the founder asserts (Interview, June 2017). Instead, Skjutsgruppen relies on radical transparency across all types of interactions occurring via the online platform. It is thus not possible to communicate privately when arranging a ride; all conversations on the website are visible to all members. Members of the platform are also required to link their profiles with social media sites, such as Facebook, to identify whether driver and passenger have “common friends” that can be contacted in case of doubt. Terms such as “member”, “participant” or “friend” are deliberately chosen to avoid the perceived negative and anonymous connotation of “user”.

This collaborative approach is further revealed by Skjutsgruppen’s priority to open innovation and dynamic organisational structures (Ostrom 2015). For example, I participated in an online meeting via Facebook in which we discussed how to collect the remaining sum required to build a mobile app (something the community has been planning for years but always postponed due to lacking financial means). During the meeting any participant (including myself) could suggest potential financial sources and, if the idea resonated with the participants, anyone could realise that idea individually or as part of a team. Such online meetings are typically organised via the Skjutsgruppen Facebook group so that meetings can be scheduled democratically at members’ convenience (using Facebook’s poll function). In addition, decision-making is approached in a self-organising manner according to the competencies and expertise of the volunteers. Participants who are motivated and knowledgeable in a particular subject area can take the lead in an initiative without the anaesthetising consequences of bureaucracy often found in corporations. In a way, this relates to the notion of equipotentiality put forward in the collaborative economy – the idea that everyone has equal chances to contribute in decision-making processes (Benkler 2004).

Lastly, in light of increasing digitalisation of the ridesharing market, efforts to realise the access-economy (Rifkin 2001) have surfaced, particularly in the provisioning of free travel data. To fully leverage ICT developments, Skjutsgruppen offers access to their Application Programming Interface (API), allowing other stakeholders to use their ridesharing data to develop other transportation platforms. Public transportation providers, such as bus operators, could combine their own travel data with the data from Skjutsgruppen to create a meta-platform for intermodal mobility solutions (also known as Mobility-as-a-Service). Such open source solutions thus enable collaboration on a technical level among those enthusiastic about sustainable travel. Representative statements of the founder such as “we don’t have anything to hide,” aptly echoes the overall passion for a collaborative approach to ridesharing.

Heetch – attempts to hybridise sharing economy concepts

Heetch was launched in Paris and entered the Swedish ridesharing market in 2016 with the aim of providing Millennials with a fun and safe alternative to established taxi services. The organisation is funded by venture capitalists and has launched its services only in Stockholm (crunchbase.com). Uniquely for Sweden, Heetch provides a platform for unprofessional drivers to convey passengers by utilising privately-owned cars. This case is interesting because it attempts to form a hybrid based on two conceptions outlined in the previous section, namely the on-demand economy and the collaborative economy.

Attempts to realise the on-demand economy

First, Heetch has a rather professional appeal akin to on-demand services such as Uber, especially in the way the platform is designed for drivers to obtain several gigs per shift. For example, Heetch provides a mobile application to hail drivers at their convenience, while (unlicensed) drivers in turn pay a 15% commission per ride. Interestingly, it has recently launched an additional “pro service”, which allows more qualified professional (licensed) drivers to operate at a higher price point, aiming to stretch the ridesharing boundaries towards professional incumbent taxi operators. As part of this add-on, Heetch recently introduced a technical makeover of the app, adding an interactive map providing customers the option to seek suitable drivers nearby and to choose between pro or classic services.

Second, in its quest to outperform competitors and establish a strong presence in Sweden, Heetch campaigns pro-actively to recruit new drivers and customers. For example, I identified multiple staffing efforts on local job portals, the Heetch website, LinkedIn and even through external recruitment agencies. Once accepted as a driver, individuals attend a series of training sessions to ensure a certain quality standard. While this closely parallels recruitment processes at Uber, it differs significantly from Skjutsgruppen’s membership-based approach.

Third, the political element in shaping markets advanced by Fligstein (1996), highlights the importance of social relations with authorities and other actors in the field. In line with Fligstein’s argument, Heetch has sought to establish a dialogue with politicians to foster a close relation based on trust and knowledge exchange. In addition, the country manger co-founded a think tank called Shared Economy Sweden to engage in conversations with stakeholders across administrative bodies and private actors. Specifically, the think tank focuses on three key issues: changing regulatory frameworks, improving tax systems, and disseminating knowledge about sharing (sharedeconomy.se). Correspondingly, Heetch has spent a significant amount of effort on lobbying and legal matters to defend its unique approach of combining professional and unprofessional drivers in ridesharing (see next section).

Thus in many respects, Heetch is oriented towards on-demand service for profit rather than “fun” and collaboration. However, in addition to the commercial practices illustrated so far, Heetch also engages in efforts that are more reminiscent of the collaborative economy.

Attempts to realise the collaborative economy

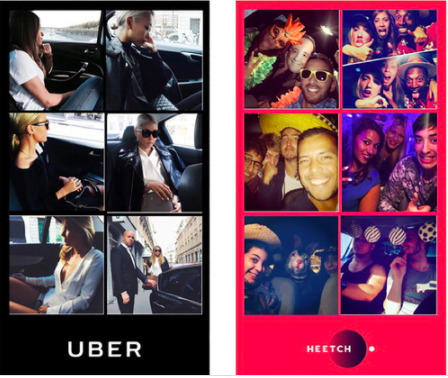

Consider the juxtaposed images in Figure 1, below, which illustrate how Heetch seeks to create an impression of difference from Uber. By highlighting ostensible differences Heetch attempts to position itself as different from Uber and the associated connotation of professionalism.

Figure 1. Heetch’s framing efforts to demarcate its otherness vis-à-vis Uber (source: company presentation, June 2017).

This juxtaposition is also emblematic for Heetch’s efforts to situate itself in the realm of “mobility as entertainment”, as stated on the website. It is clear that Heetch aims to be perceived as a platform for the people, or more pointedly, for young party-goers. The service operates only at night targeting young individuals who cannot afford regular taxis. In contrast to its main competitor, Uber, drivers stretch out to remote areas in order to make the city’s nightlife “more inclusive for young suburban residents” (Internal company presentation, June 2017). Relatedly, consider the following statement that frames Heetch as a complementary source of urban travel, rather than a substitute for established modes of transportation:

We are not a competitor to regular taxi services, instead we are a supplement to public transportation. After a trip is accomplished, the passenger gives a donation to the driver which allows to cover the costs for the drivers’ car […] (Internal company presentation, June 2017)

This statement is interesting for two reasons. First, it brings up the question of how Heetch manages to realise the two worlds it envisions. On one hand Heetch operates akin to incumbent taxi operators and is thereby de facto a competitor. On the other hand, it portrays itself as a collaborative ridesharing platform vis-à-vis public transport. Second, the statement reveals that Heetch uses a compensation model that is very different from regular transportation. Formally, a Heetch driver suggests a fare (price) in the form of a donation and passengers can opt out or alter the amount at their convenience. After each ride, passengers receive an automated notification on their mobile device with a suggested donation, which in effect works similar to a regular price.

It seems central for Heetch to have virtuous organisational characteristics in order for the commercial appropriation to succeed. In a variety of published debate articles with national coverage, Heetch assertively repeats its non-profit intention:

We provide a model for car owners to cover their costs through ridesharing, we do not provide a traditional [profit seeking] job as such. This becomes particularly clear through our implementation of the income ceiling. (Internal company presentation, June 2017)

The mentioned income ceiling means that Heetch inhibits drivers from generating excessive profits by stipulating a yearly income limit of 40,000 SEK (circa USD 4400). According to the country manager, this amount corresponds to the annual fixed costs related to maintaining a private car in Sweden. Note that this clearly reveals a different conceptualisation of the sharing economy compared to both Uber and Skjutsgruppen. For Heetch “ridesharing” is about “sharing the driver’s cost” as opposed to “sharing the cost of a trip” (Skjutsgruppen).

The official mission of Heetch reads: “to make sure that people can enjoy their night out”. But since the provision of rides by unlicensed drivers is not well-accepted yet in Sweden, Heetch launched few initiatives to address this. For example, to make customer rides safer at night, feedback functions such as performance rankings assess drivers’ “trustworthiness”. The performance ranking works similar to the system implemented at Uber (rating scale from 1 to 5), but also allows comments about the overall experience. Furthermore, Heetch makes it a priority to make rides interactive and comfortable for teenagers, creating a social atmosphere through an assortment of snacks, refreshments and “good vibes” (country manager, interview July 2017). These efforts seem to pay off. A user survey of 15,841 Heetch users suggested that, “Only 2% of Heetch users have ever felt in danger during a Heetch ride, versus 38% in public transportation services, 30% walking, 16% by (own) car and 14% on two-wheelers” (internal company documents).

Lastly, to foster a community ambience between driver and passenger, so-called brand ambassadors regularly represent Heetch at festivals to educate potential users about the platform and to provide opportunities to ask questions concerning prices and safety. For example, in my volunteering experience as ambassador during a festival, I noticed how playfully Heetch workers approached potential users in order to meet them at eye level and respond to their questions. Various games and a photo booth were set up to create a reliable but informal brand relation. It seems clear that Heetch tries to reconcile ideas drawn from two different sharing economy concepts, namely the on-demand economy and the collaborative economy. While Heetch provides professional services akin to incumbent taxi drivers (e.g. quick hailing on demand), it also attempts to build a reputation as taxi-for-Millennials, focusing on safety, entertainment and fair prices.

Summary

To briefly summarise, we can observe diverging approaches to ridesharing across the cases based on different conceptualisations of “ridesharing” as such and as driven by the actors’ interests in popularising their particular platform. We can also observe that each approach requires heavy investments in boundary work, which is done in different ways, e.g. through professional Apps, official Ride Sharing Days, and donation-based services. These observations beg the question: given the presence of multiple approaches to ridesharing, how do different boundaries co-exist and what happens when they coincide or conflict? The following section discusses this question to highlight the precariousness of multiple market boundaries, particularly when other stakeholders beyond the ridesharing platforms become involved, intentionally or not.

Performation struggles around ridesharing

Multiple efforts to frame the Swedish ridesharing market have heated up the climate among transport providers and intensified the controversies concerning the “right” market framing. In a public debate article, Skjutsgruppen suggested, “restaurants are no picnic – taxis are no ridesharing,” because “friends don’t make money off of friends” (Göteborgs-Posten, May 14, 2016). Following its activist approach, Skjutsgruppen takes a clear stance against on-demand platforms that adopt the ridesharing-label for the purpose of legitimising taxi-like services (e.g. Uber and Heetch). Ridesharing, according to Skjutsgruppen, is not about making profits.

Another obvious performation struggle involves the incumbent taxi operators. As noted above, Uber and Heetch drivers often use multiple apps simultaneously to increase the number of gigs per shift. Interviews with drivers revealed that many incumbent actors, such as Taxi Stockholm, strictly prohibit Heetch and Uber drivers from acquiring customers through both ridesharing and taxi companies at the same time. This means that drivers need to be aware of contractual agreements that deliberately exclude ridesharing platforms from the taxi market. The rising number of license-free drivers and the lax regulations for ridesharing in Sweden led the local taxi association to publicly announce their frustration concerning current regulatory frameworks: “Yes, we are desperate!” (Dagens Industry, June 16, 2016).

A recent report issued by the European Commission highlights the multiplicity related to these performation struggles, as the controversies enrol actors other than transport providers (Codagnone, Biagi, and Abadie 2016, 7), “rhetorical discourses, public controversies, and more tangible battles, as it occurs in any kind of polarisation process, fail to consider that sharing platforms cover a wide range of different activities.” Regulators, for example, are particularly concerned with ambiguous market boundaries. Following a series of court rulings, Uber subsidiary UberPop eventually had to terminate its operations in Sweden in 2016. This was largely due to inconsistencies between local authorities and Uber in framing the ridesharing market. Despite the absence of explicit legal definitions for ridesharing in Sweden, UberPop was regarded as an illegal taxi service because drivers were unlicensed and used privately owned cars with no official taxi metre. A Swedish appeals court moreover convicted dozens of UberPop drivers which led to the suspension of driving licences and in turn numerous missed job opportunities for previous Uber drivers (Reuters, May 11, 2016). Similarly, Heetch was found to operate illegally in France and was forced to shut down its services for a few months in 2017 (mainly due to unlicensed drivers). In line with this, Swedish journalists have expressed harsh critique against the platform, arguing that it is “illegal according to both the police and the transport agency, and those who are driving can now face the same fate as the drivers of the abandoned UberPop” (Sveriges Radio P4 Stockholm, October 21, 2016).

But the growing controversy around ridesharing has not been without merit: Swedish regulators have long disregarded the vestigial state of current transport jurisdictions. A point in case is the absence of a legal definition for ridesharing. To address this, in 2016 a year-long government inquiry set out to explore the necessary steps to establish a legal framework for new platforms (“Taxi and ridesharing – today, tomorrow and the day after tomorrow,” 2016). The inquiry proposed three key improvements. First, it was deemed crucial to create a legal category for ridesharing, including an official definition: “trips where two or more individuals travel together to the same destination or in the same direction, in order to share the costs incurred” (307). Second, it was suggested that drivers should be required to obtain a taxi license to guarantee professionalism and safety. Third, Swedish regulators were urged to improve the taxation system for sharing economy related income (e.g. for Uber-drivers). That is, drivers may use private cars but are required to use some form of digital taximeter that tracks each ride for tax purposes. Such regulatory adjustments are likely to intensify performation struggles. While the suggested definition for ridesharing is clearly in line with Skjutsgruppen, if this proposal will at any time become effective (which is highly probable given the ongoing controversy), Uber and Heetch could encounter legal difficulties due to their taxi-like practices.

Lastly, the conceptual controversies perpetuate a degree of vagueness that fuels performation struggles in the context of (mainly public) financing. In particular, professional service firms often strategically seek vague ways of framing the sharing economy in order to avoid personal scrutiny in their reporting. Consider this highly-cited report issued by PricewaterhouseCoopers in its Consumer Intelligence Series (2015):

For the purposes of consistency in our reporting and research, we used the label ‘the sharing economy’ to broadly define the emergent ecosystem that is upending mature business models across the globe.

However, the spread of such extremely vague definitions has implications for market developments because they act as mediators between “industry experts” and interested stakeholders when moving across spaces. As this vagueness lends itself to various interpretations, it produces confusing images of the sharing economy among public and private investors, which often rely on such reports when forming an understanding of new sharing platforms. For example, when Uber adopted the term “ridesharing” in the same way as other ridesharing platforms in Sweden, public investors (i.e. municipalities) became very hesitant to discuss financial backing with other non-profit ridesharing platforms. This hesitation was largely due to the repeated vagueness of the sharing economy reflected in whitepapers, consultancy reports and other media outlets.

Discussion

This paper has addressed two main questions. The first question concerns how controversies concerning how to conceptualise a certain market – in this case the market for “ridesharing” – contribute to shape that market. The second concerns what role(s) market boundaries play in putting market concepts into productive use. While the presence of multiple market conceptualisations may seem intangible and abstract, it should be clear that, in the Swedish ridesharing market, the opposite is true. The conceptual confusion renders visible how market boundaries, in all their heterogeneity and hybridity, are deliberately drawn and redrawn as a result of theoretical and political tensions. This redrawing concerns the boundaries between what is and is not “real” ridesharing, between what is and is not legal and between how the different market concepts – collaborative, on-demand and access economy – are brought to bear in daily practices.

Three interrelated themes from the digitalisation of ridesharing and the related conceptual controversies merit further discussion: (1) the roles of market boundaries in the shaping of markets; (2) the multiplicity of markets and the interference of individual versions; and lastly (3) the role of digitalisation in prompting parallel market strategies.

The roles of boundaries in shaping practices and space

Fernandez and Figueiredo (2018) recently argued that boundaries, in the more general sense of the word, are often being stretched and transgressed. My analysis of ridesharing suggests that market boundaries are no exception. This stretching and transgressing of boundaries involves different activities, such as efforts to hybridise previously separate markets (e.g. Heetch), engaging in (unfair) competition (e.g. UberPop), and efforts to create a ridesharing movement (e.g. Skjutsgruppen). Several noticeable attempts illustrate that boundaries are, as Dumez and Jeunemaitre (2010) suggest, not given from the outset but constantly drawn and redrawn.

First, platforms try to build and maintain boundaries through specific practices. For instance, Skjutsgruppen deliberately employs practices aligned with their underlying conceptualisation of the ridesharing market as collaborative economy. This includes the organising of official Ridesharing Days and the provision of free education in municipalities across the country. To make its position clear, Skjutsgruppen deliberately avoids, indeed actively resists, practices employed by other ridesharing platforms, such as Uber’s above-average commission for drivers. The boundaries it attempts to draw is also reflected in and reinforced by its use of specific terms such as “member” and “friend” rather than “user”. All the studied ridesharing platforms seek to shape the boundaries within which they wish to operate through rhetorical strategies and promissory work (Pollock and Williams 2010). In this sense the market boundaries they attempt to create and enforce work as “symbolic boundaries” (Lamont and Molnár 2002); they function as tools through which practices are legitimised and recognised.

This competition around boundary drawing hints at the marketing efforts required by platforms to put their ideas into productive use. As mentioned above, some actors engage in “sharewashing” strategies to disguise their profit motives and make them more similar to other sharing initiatives, whereas other actors employ narratives that instead distinguish them from (potential) competitors. The competition around boundary drawing thus illustrates how each actor tries to stretch and contort the boundaries of the market for their own benefit through specific practices, products and services. As a consequence, this has created an ongoing performation struggle concerning how to “properly” frame ridesharing. This struggle has become increasingly heated not least because Uber, for example, persistently employs practices akin to taxi firms, while positioning itself as a ridesharing platform. Unsurprisingly, borrowing a metaphor from Orwell’s “1984,” Skjutsgruppen confronted Uber with the statement that “Newspeak does not change the facts,” hinting at the misleading use of “ridesharing” in Uber’s on-demand practices (Göteborgs-Posten, May 14, 2016).

Second, and in line with Christophers’ (2014) claim that it is practically impossible to examine “really existing markets” without invoking their geographical dimension, there is a clear spatial dimension to the market boundaries being drawn. Skjutsgruppen employs a geographically wide definition of their market – a nationwide movement – which has led them to engage in activities across the country. In contrast, Heetch employs a much narrower definition of their market, offering rides only in the greater Stockholm area. Such territorial qualities reveal the spatial constitution of markets as “material particulars” (Berndt 2015). By “territorialising” the ridesharing market, i.e. linking it to a physical location, platforms render market boundaries more visible than without the associations to specific cities or regions. In this respect, Buzzell (1999) reminded us that marketing scholars have tended to overemphasise the idea of markets as abstract signifiers, i.e. marketspaces rather than marketplaces. Here, the contemporary ridesharing market offers an important insight: Despite the abstract and often de-territorialised character of its conceptual discussion (Sundararajan 2016), the spatiality of the ridesharing market remains an essential puzzle piece in its practical realisation. Especially marketers are confronted with the challenging task to orchestrate the range of digital devices (apps, websites, digital keys, social media, etc.) and simultaneously adapt these to local preferences and concerns.

This encourages us to rethink the dominant view of digitalised markets as geographically dis-embedded abstractions (cf. Alvarez León, Yu, and Christophers 2018). As the findings illustrate, the spatial dimension of digitalised markets directs attention to the situatedness of boundaries which do not seem reducible to a single homogeneous frame, but are instead linked to practical issues, regulations, local discourse, etc. In fact, economic geographers have recently highlighted the socio-political tension arising when digitalised markets become territorially contingent (Alvarez León, Yu, and Christophers 2018). Spatial boundaries are based on the proximity of potential customers (e.g. urban vs nationwide) but also depend on a complex infrastructure of digital devices, which leads to a balancing act of capturing opportunities and considering the available technology. Moreover, in foregrounding the dependency of urban agglomeration for Uber and Heetch, the Swedish ridesharing market once more renders visible the intertwinement of spatial and digital concerns in seeking a critical mass to gain momentum on digital platforms.

Continuous framing and market multiplicity

The three cases contain many examples of how individual efforts to frame the ridesharing market in Sweden come to produce multiple market versions. This multiplicity largely stems from actors entertaining and promoting different conceptions of the sharing economy, leading them to actively engage in constituting the reality they envision (Callon 2007). Consider the cases of Skjutsgruppen and Uber. Skjutsgruppen attempts to re-organise the ridesharing market as a collaborative economy driven by a strong belief in a governance model resembling the commons à la Ostrom (2015). Uber, on the other hand, bases its operations on a conceptualisation of the sharing economy in which economic avarice plays a key role, reflected in organisational forms and processes aiming at efficient matchmaking between drivers and customers. Even though Skjutsgruppen and Uber seek to perform different concepts, and thus employ different practices, both enact particular ideas discussed in the wider sharing economy literature. Given the generic performativity of market concepts (Callon 2007) and the volume and variety of contributions proffering ideas about sharing markets, the observed multiplicity of ridesharing versions in Sweden is hardly surprising.

The multiplicity of markets can be understood as the fluid manifestation of concepts enacted in the continuous process of market framing. Heetch started as a pure peer-to-peer platform without professional drivers, but morphed into a hybrid platform combining features of the collaborative and gig-economy to prevent further public turmoil. Rather than a single correct way of framing, markets are framed for different and multiple reasons, including risk reduction and ideology. But the boundary work required to maintain and challenge boundaries is neither entirely transparent nor always successful. Consider the controversial case of UberPop: For this on-demand concept to succeed, it required an adjustment of the environment within which it operated (i.e. changing fragmented and obsolete regulatory frameworks). Interestingly, the UberPop initiative did not just fail to produce the reality it envisioned, it also produced overflows in that public investors became hesitant towards other Swedish ridesharing platforms. In other words, a particular framing can lead to negative overflows that force other actors to actively dissociate themselves from a stigmatised or unsuccessful actor. One way of doing this is to present and reinforce an alternative market conception through active boundary work, as Skjutsgruppen does.

Such adjustments and reactions to ineffective market framings are obvious modalities of performation struggles (Callon 2010). As illustrated earlier, struggles arise when the presence of theoretical and political tensions interfere with the efforts to realise different versions of ridesharing (e.g. UberPop). This interference suggests that controversies are productive in that they enrol various actors and their concerns until market boundaries are temporarily stabilised. This also suggest that in controversial environments, such as ridesharing in Sweden, the complexity of market realities is increased through regulatory, geographical and historical contingencies as more actors become involved. Multiple market versions thus not merely co-exist, but bring to bear and render visible various historical and vested interests. A straightforward translation of market concepts into the “wilderness of the ‘real world’” is therefore hardly ever achieved (Berndt 2015, 1866). This wilderness is amplified by the ongoing processes of digitalisation, which already have affected how we travel and share rides. New payment systems, the Internet of Things, and soon self-driving cars will create further opportunities to disrupt traditional ridesharing and taxi services. Remember the time we used to say “never get into a stranger’s car?” For many of us, sharing rides with strangers has become the norm. Fuelled by the advent of ICT and the penetration of smartphones the potential circle of sharers has expanded far beyond immediate kinship.

Digitalisation prompting specific market responses

How does the digitalisation of markets concretely influence ridesharing in Sweden? Most obviously, it changes the elements of markets or “the stuff markets are made of” (cf. Hagberg and Fuentes 2018). This includes the development of new products (e.g. mobile apps, websites, blogs), the altering of market practices (e.g. riding with absolute strangers, hailing via digital platforms), the assessment of drivers and their behaviours (e.g. peer to peer reputation systems) and the democratisation of planning a trip through convenient digital platforms (e.g. Facebook groups). In short, the resulting sharing markets are very different from previous versions of such markets.