#themes are at odds but the narrative mechanics have core similarities

Text

the elden ring dlc story trailer just dropped so just letting you guys know that i’m gonna find a way to integrate elden ring lore into dunmeshi somehow because i need both stories like i need air to breathe

#aspects of both could definitely work in the same universe#my only hesitation in lumping both together is that i don’t really think they’re inherently compatible just because Fantasy Genre#the core themes of elden ring are so at odds with dungeon meshi lol#the shrouded path of seeking power mired in bloody sacrifice all in the name of ascending to godhood for your own ambition#(but not really bcs there’s always an outside cosmic influence so what of free will)#versus the humble everyday work of sustaining the self in relation to community as a way of living with purpose#(free will is the ultimate challenge to being trapped by your own desire)#themes are at odds but the narrative mechanics have core similarities#defeat the dungeon lord/legacy dungeon boss and obtain their power#also the premise of the shattering being comparable to the upheaval of mana in dunmeshi universe#and how it challenges the existing power structures#i have so many thoughts#i’m definitely gonna get the platinum for the ER dlc#so it’ll be a grind and you guys are gonna witness me in my gamerfail era#if it’s anything like the bloodborne dlc i’m ready to get my ass whooped#but i’m gonna love every second of it#wasabi rambles

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

You Got Blood On Your Money

Question: how do you make honest art? Is this not the eternal conflict as a creator- how to stay genuine to yourself and your art without tripping into the pitfalls that lay within fame or money or popular culture? Every creator must grapple with the fight between being seen and being sold. But very few artists struggle with this quite as visibly as My Chemical Romance has. From the inception of this band, which has always been more art project than musical endeavor, its members have tried desperately to convey a bone-deep sincerity fundamental to their work. From their very first song, the band proclaims itself as a savior to a generation that had been stripped of their will in the face of unimaginable horror. At the same time, there exists within their music a commitment to storytelling, a desire to fill the empty space in rock music with narrative and macabre and emotion that had been absent. Both of these elements manifest themselves into a band that very seriously considered it their mission to save people’s lives, as well as to create deeply meaningful art. But how do you save as many people as possible without being corrupted by the spotlight? And how do maintain genuine storytelling as you get further and further from the basement shows you got your started in?

These are questions that permeate their music at every turn, something that haunted each album and made itself known in each new project. And while there are many ways to dissect this particular struggle in their discography, nowhere is it more apparent than in the dispute between Thank You For the Venom and its reimagined successor- Tomorrow’s Money. These songs are noticeably similar in their structure as well as lyricism and imagery but instead of the latter building off of the other, they are inverses of each other. And they speak to My Chem’s long battle with becoming a legendary band in the midst of also attempting to keep their identities as artists and outsiders. And in analyzing their differences, it becomes reflective of the band’s main career-long conflict between the commodification of their art and the need to create something larger than themselves. And the question remains, were they successful?

Before we answer that, let's talk about Thank You for the Venom. To begin, it's important to note that Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge is an interesting part of My Chemical Romance’s discography because ultimately, it is unconcerned with legacy, but instead is centered on the immediacy of loss and the reactionary pursuit of revenge. In a record overwhelmed with death and grief, there is very little mention of the afterlife for either the living or the dead- characters are murdered but there is very little textual violence. Characters come back to life but there is minimal discussion of how they died or where exactly they were in death. However, that does not mean Revenge is not devoid of mythologizing- it just happens to be about immediate intention rather than a long-term commitment. It is because of this reckless drive forward almost to spite the odds that allows for Venom to exist as the band's declaration- it is their call to arms. Specifically, the track is a pronouncement of My Chemical Romance as renegades fighting against the fake, safe bands writing hits for money instead of survival or purpose: they “won’t front the scene” if you paid them, after all, but are instead running from their enemies. And not only are they an oppositional force, but they are pariahs, targets- something you can try to kill but will fail at. More specifically, in “If this is what you want the fire at will” there is an element of martyrdom, the idea that they are not just a necessary part of the very structure of society but also there is the implication that killing them is to concede to their influence and a necessary part of their lifecycle. Once you get big enough to become a target, you inevitably will be shot down- that is the final step of a great and honest band’s success. This also feeds into the album's wider ideas surrounding revenge as a concept as the greatest revenge is finding success in the aspects of yourself and, by extension, the things you create that other people thought were worthless (I don't think it's a coincidence so much of this album is steeped in comic book imagery and art and mixing punk and metal and theater when those are things the band would get shit on for enjoying). At the same time, this theme exists as the foundation necessary to create an anthem of survival- revenge is the fuel that keeps the protagonist, as well as the band, in motion. Look at the specifics of their thesis- “Just the way the doctor made me” and “You’ll never make me leave” are both reconciliations with the self in spite of the prevailing narrative against them. That connects to the way this song is a statement of a savior and a martyr twofold- “Give me all your hopeless hearts and make me ill” as a representation of the band taking on the pain of others to keep them both alive. All told, in Venom there is perseverance in the face of a large, unimaginable adversary. It is a threat directed at your enemies. It’s living as free and ugly and completely yourself as you can until they shoot you down in a hail of bullets. And then even that end is itself a victory.

Here, at its core, Venom is really the singular instance in the entire album where the band reconciles with an image. And the image the band creates for themselves is as outcasts in opposition to the "scene" and as a revenge plot, proving to their audience the value of authenticity and survival and rubbing it in the faces of those who doubted them. These themes about what My Chemical Romance is and what their goals are is something they wrestle with for the rest of their career- how do you say lives, reach an audience, and remain a fighting force against the societal norm when you exceed your mission and become part of the fabric of popular culture? But that is for later, at this moment, Revenge imagines no future. Only this desperate battlecry.

By contrast, Tomorrow’s Money is dealing with the aftermath. Functioning as a cynical reimagining of Venom, the song is structurally, thematically, and even lyrically reminiscent of Venom to an uncanny degree. First and foremost, the songs are structured the same- a slow build-up into a whispered intro, a multi-part chorus, the exact same chorus-verse layout, and a strikingly similar solo. Looking at the two Toro solos more closely, they both feature more building up as well as tremolos, triples, darker tones, and what sounds like a slide progression just ripping through both of them. Tomorrow’s Money is mimicking Venom pretty clearly here- either as a direct reference or because Venom is so reminiscent of the condensed MCR sound that they’re ripping off to make their point. And looking deeper at the themes present in Money specifically, just like Revenge, there is a clear lack of legacy- “we got no heroes ‘cause our heroes are dead” calling back to the very real disillusionment of Disenchanted that’s placed specifically in a song about becoming part of the machine, being heroes themselves, to nod to the fact that the very mission of the band is dead as well.

Simply put, Money tackles similar issues as Venom about fame and audience and creating art while using much of the same language and metaphors to completely invert the claims found in the “original”. To start with, both songs use the verbage “bleeding” to associate with a kind of suffering for your art that was an aspect of their previous band ideology. Namely, it’s the idea that the audience makes the band ill through the “hopeless hearts” as much as the “poison” does. The “what’s life like bleeding on the floor” of Venom is paired with “you’ll never make me leave” is a statement of defiance and survival against the odds while still bearing the burden of other’s pain. Money, on the other hand, explicitly says they “stopped bleeding three years ago” as a rejection of this leftover martyrdom prevalent in Revenge especially. But it also refers to their newfound luxury of comfort, they have a way to stitch themselves together that they didn’t have before. These implications transition directly into the ideas surrounding health, vitality and living- specifically surrounding both doctors and infection. Speaking of the former, Money has an interesting lines in “If we crash this time, we’ve got machines to keep us alive” and "me and my surgeons and my street-walking friends" because they speak to both becoming a part of the “industry” by mentioning mechanization but also specifically evokes the living dead. In the MCR canon, the idea of the undead (both vampires and zombies) are antagonistic forces that represent the outside world, specifically fake people or the music industry. And zombies, in general, are already rife with allegorical connections to consumerism, like how Dawn of the Dead, a known mcr influence, is directly about materialistic culture. Vampires, subconsciously or not, are often representatives of exuberant wealth as well as beauty and desire. They’re also blood-suckers and leeches that someone in this narrative has fallen in love with, as if colluding with the enemy and allowing them to literally drain them and their life force. Thus, in describing themselves as essentially undead (when they crash, they’re revived) as well as directly collaborating with the undead, they are connecting themselves to the very forces they’ve been fighting. But perhaps the most interesting aspect of this association is how they specifically relate it to survival, the only way of staying alive is to accept them, to allow themselves to be hooked up to the machines that make them undead in the first place. Almost as if you make it far enough not to tear yourself apart, you’ll eventually assimilate into and become part of the industry.

This idea of unavoidable assimilation is compounded with the multiple references to viruses- “You're loaded up with the fame. You’re dressed up like a virus” then being reemphasised with “We’re gonna give it for free. Hook up the veins to the antibodies, got it with the disease, we’re gonna give it to you”. Both these lines condemn fame but also implicates themselves as part of the contagion that is celebritidom at the same time it depicts this process as unavoidable. Not only that, they’re the ones spreading it at the same time they condemn it. This duality, possibly even exaggerated hypocrisy is buried deep into the foundation of Money. Even the ending line, as angry and inflammatory as it is- still names them as complicit as the "I’ll see you in hell" implies that they're going to hell too. Looking even deeper, there are multiple references to the dilution of their message: “Choke down the words with no meaning” and “The words get lost when we all look the same'' both representing meaninglessness in the lyrics while “the microphone’s got a tapwire” is reminiscent of wiretapping or even the surveillance company Tapewire, suggesting their words are under scrutiny, they are being monitored and that could be one of the reasons for meaningless words. All of these lyrics reference, with subtly or, in the case of the last one, very obviously about the sellibility and how rigid the label of “emo” is and how they couldn't escape it - they may not have gotten paid to front the scene, but they sure did inadvertently lead a cause. And being put in that position was clearly very stifling, striping them of their artistry. Even looking at the response to Black Parade, it's clear that popular culture at large did not appreciate the record for its genuine message but for the moment in time it represented or the aesthetics it called back too. In many ways it was taken at face value- “words with no meaning” or just another dark, death obsessed emo record. What Tomorrow's money is is a rejection of the glorification of suffering and nativity of Venom in the face of becoming pop culture icons but it's also, in a way, reconciling with a perception of failure and loss of creative control that will haunt My Chem for the rest of their years.

Ultimately Tomorrow's Money is representative of the band's response to the gradual shift of My Chemical Romance, as an entity, away from martyrs to an accepted part of the music industry and culture. How do you reconcile with that? In this moment, in a post-Black Parade era, they try taking everything down with them- becoming a whistle blower to their truth. But perhaps most importantly, this conflict lays the foundation for Danger Days as both critique of industry’s commodification of art, as well as the reutilization of the obsession with legacy and death in their next project -no longer can they let the machines revive them, they have to get out of the city, yell incendiary graffiti at the top of their lungs, and explode in brilliant colors. It was time to return to calls to arms. It was time to return to the power of not just of death but of living on long after it, the album the act of becoming folk heroes for a new generation. And while the bright lights didn't last forever, by scrapping Conventional Weapons and starting over in the name of artistic integrity they truly created a legacy of material unrivaled in its sincerity, reach, and cultural significance.

As we know, the story didn’t end there. The final chapter used to be closed, and ending with "I choose defeat I walk away and leave this place the same today" as the conclusion of their career. This was not the explosion Gerard wrote about, not the doomsday device but a quiet goodbye, a silent curtain call. It's another round of disillusionment finally fully-realized. And yet, the Reunion seems to be a direct contradiction to their farewell- in some way they did come back because they were needed, because their absence was a gaping hole in music at large which suggests they did change things, that they do have a noticeable effect on the world they inhabit. Looking at A Summoning for even a moment, the picture illustrated to the viewer is that they are an otherworldly power. That they are an entity that you plead for the return of, the hero and the savior on clear display. And regardless of how you feel about the postponement, you can never talk away that fact- some force bodily brought them back in their narrative, that it was human interference that started the resurrection. And that it was primarily through art, especially that video, that they declared their forced-to-be unfulfilled intentions. I've always liked to believe that we've cycled back around, that the cynicism of Conventional Weapons and then later Fake Your Death has had its moment but now it's time to return to that world of rebellion in this era of the desert- the reinhabiting of reckless living and creation. Again, we must ask: what does it mean to make art for the masses? I don’t think we’ll ever truly find the right answer, but I think My Chemical Romance have always tried their best to solve the equation.

#you know the drill. Bibliography Post <33#yes. i HAVE been thinking a lot about venom recently how can you tell?#my posts#mcr assigned reading

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Favourite Games of 2019

I don’t like making ranked lists anymore. So here’s a bunch of games old and new I played in 2019 because I was busy catching up due to not playing FFXIV as much as in previous years.

Ciconia When They Cry Phase 1: For You, The Replaceable Ones

I think going in, and even starting to play it, I felt like maybe the game would abandon the WTC mystery game conventions. It ended up not doing that, because the game leaves you with far more questions than answers at the end. The A3W World (“after World War III”) is still trying to deal with political issues and social issues that existed prior to World War III. A global stalemate exists due to the military implementation of the Gauntlet weapon. Eventually things happen where different countries need to deal with a shortage of resources, territorial conflicts, etc which sets off a chain reaction to World War IV. However, the children who grew up in the A3W era, settled into new ideologies and views of how society currently works are at odds with what the older generation wants and requires of them. Along the way, they need to deal with other groups and conspiracies in order to maintain the Walls of Peace.

So in essence, R07 still crafts a mystery for readers to figure out, but it isn’t a murder mystery. It’s an international conspiracy mystery and I am more than okay with that. I think this chapter required a lot of worldbuilding to set that kind of story up and coming out of Phase 1, I understood why the first chapter wasn’t exactly like Umineko’s. I thought that it was handled well, despite some of the purple prose (but if you’ve played a R07 game before, you’re likely used to it). I also thought he really tried to introduce and incorporate themes including gender, generational differences, societal tiers, geopolitics disguised as sports events (possibly mirroring the 2020 Olympics in Japan), etc. as well as he could throughout the story through the game’s cast. Even if the game meanders a bit (and it definitely feels that way towards the start), when it actually starts to roll, I felt compelled to keep reading.

And truly, the game has an incredibly large cast of characters. The TIPS section handles introductions well, and while some cast members don’t have as much time in the spotlight as others, I can see them getting their time eventually in subsequent chapters. Clearly Phase 1 exists to focus more on the children from the Arctic Ocean Union (the “AOU”) as evidenced by the additional stories unlocked at the end of the game so hopefully other chapters have the same amount of character backstory for the other factions. I also genuinely enjoyed that the big international cast of characters allowed for many different types of designs with characters with different types of hairstyles and hair texture or characters wearing hijabs and still managed to make them retain adorableness or a sense of style. I do not recall seeing it as often in Japanese media and I’m very happy to see it here.

I think Ciconia Phase 1 is a very good start to this subseries’ planned four episodes and I hope to see more sociopolitical commentary. It feels as though R07 looked at everything happening in Japan and social media/how news is consumed and decided to write a four-part SFF series about it. I’m eagerly looking forward to the next chapter.

Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night

I backed Bloodstained when it got put on Kickstarter a few years ago. It was shipped to me at… possibly the worst time since Shadowbringers was coming out very shortly after. My fiancé and I played ours for a short bit, felt very positive about the game, then dropped it to play Shadowbringers. We didn’t return to it until maybe September/October? Both of us ended up getting our Platinum Trophies for it so we both played through everything the game had to offer.

Bloodstained is a good experience, but not without its issues. I played on PS4 and I’ve had a few outright crashes or some glitching into walls early enough that I couldn’t come out of them again due to not having the required skill to try to get out of it. I also felt like the game meandered or had a bit of padding in its earlier stages). Later on, you realise you have to put in the farming work to have a better and faster time not unlike its Igavania counterparts, but I did feel like the drop rates prior to actually working towards higher luck stats/drop shards were low enough almost to the point of unfair or deliberately wasting my time. I also felt as though there were too many weapon types; with adequate shard use and shard grinding eventually you can settle into one weapon type that suits your playstyle or eventually use the gun for everything when you get the special hat quest reward).

However, I’m speaking about this game as someone who platinumed it which requires a lot of farming and synthesis. As a player going through the main campaign, I think the maps are adequate. The backgrounds are very lovingly crafted, and the music is absolutely one of the best of the year. Boss design is also fun and rewarding, requiring the player to learn how all the different weapon types work, adequate backstepping and closing in, and boss patterns. If you suck, the game will show you that you suck very quickly and deliberately. Essentially towards the end, I felt as though Bloodstained tried very hard to cater to fans of the metroidvania style of game, and the classicvania style of game. I personally don’t think it completely succeeded but for a first time experience of trying to combine the two into one, it did its job with preparation for another game.

I also feel like some criticism was lobbed towards the game’s narrative for being told in library/book entries, and while I understand that (I actually couldn’t open all of the books for fear of my game crashing), I don’t think elaborate cutscenes and continuous dialogue would work well with this game’s flow. Bloodstained prioritizes gameplay elements and player exploration over anything else, and to be honest, I’d rather it happen that way than with long elaborate cutscenes. I also felt as though I got more out of the game because I’d played the 8-bit prequel as well.

Overall, Bloodstained is a passable experience. I’m glad I played it, and I’m glad I put the work in to try to make the game a better experience. I got what I wanted out of the game for as much as I backed it and I hope they try again with a similar formula because this is a very good first step.

The Touryst

Sometimes when I see a game with voxel graphics, I feel pretty compelled to pick it up because it looks so darn lovingly rendered and it usually ends up being fun. The Touryst does a good job with its graphical style and visiting new islands is a complete delight because of it. It looks like a game with style, and performs super-well on the Switch. It’s also one of the freshest games I’ve played in a while.

Basically you’re playing a blocky dude with a moustache who just wants to have a good time but when he gets to TOWA Monument, he’s told he has to find monument cores to unlock the world’s secrets. And then you can do whatever you want. The different islands have their own little personalities: there’s an island called Fijy which is volcanic, there’s Ybiza with a bunch of dudes chilling on the beach and passed out on their chairs, there’s Santoryn which is just Greece, and a few other places that are essentially recreations of real-world places.

As you explore, there’s a lot of stuff to do. A variety of things to do. There are puzzles and mechanics that don’t necessarily overstay their welcome, you can play footy, you can play spelunker, you can take helicopter rides, you can take pictures, get stuff for a museum, surf, play rhythm games…. It’s your vacation, do what you want. It’s a little like Vegas. Unlike Vegas, you can use your ever-increasing money and diamonds to get new moves for your moustached character to reach new objects.

As a little game where you can do whatever you want little by little, and makes for a smooth experience, I’m glad I picked up the Touryst after asking another person what they thought of it. It has great puzzles, lots of stuff to do and explore and see, and ton of minigames for whatever mood you feel like you’re in. The game is fairly short, but I’m very glad the holiday doesn’t overstay its welcome.

A Short Hike

A Short Hike places you in the shoes of a bird who is utterly determined to walk to the top of Hawk Peak to get signal for her phone. I totally understand; sometimes you’ve gotta do what you gotta do.

But the game allows you to undertake that journey however you want to. You can go right away and finish up and get that darn signal. Or you can take your time and we’ll build that bridge when we get there. There are different types of terrains to explore if you opt to take the scenic route… and it’s rewarding to do so. You can find treasure, you can water a flower, you can talk to the Animal Crossing-esque characters to do some sidequests, you can do whatever you want.

I’m sorry to say that when the game introduced fishing, I spent a lot of my time doing that. Fishing ruins me. The completionist in me wanted to fish. But the whole thing is that you don’t have to do any of this. If you want to finish the game, you can absolutely positively focus on that and the game doesn’t pressure you for it.

And that’s one of the things I like about it. It’s just whatever about the whole ordeal. I don’t feel like I’m completely and utterly missing out if I don’t decide to do something. Even the task of getting Golden Feathers to progress is fine since you only need eight for it, and the game easily gives you enough rewards to get four or five before sidequests or exploration is factored in.

Sometimes you just need to take a walk and kind of think of nothing just to clear your head. And A Short Hike accomplishes that very well.

Worldend Syndrome

In my effort to try to find other games to play in 2019 because I’d fallen a little out of love with FFXIV, I realised that taking baby steps with visual novels and bite-sized games would be the best idea to try to get back into traditional games (particularly since I was, and am, still questioning whether I like games as a hobby or not). On a whim, I decided to download a boatload of visual novel demos one night and tried a bunch of them out. Worldend Syndrome’s demo didn’t exactly grab me until perhaps halfway through the demo when I a) realised that this demo was long af, and b) nothing appeared what it had seemed as I kept going through it and the characters were enjoyable.

So I decided to get the game and dragged my fiancé along for the ride. It’s one of those standard decision-making/pick which girl you want and go down her route VNs but it didn’t really feel skeezy or ecchi other than one particular point in each girl’s story where you get confessed to. You go through the VN as an unnamed protagonist who is visiting his cousin over the summer, and you and your friends get dragged into a school club whose focus revolves around folklore. The town the protagonist finds himself in is haunted by the Yomibito, spirits of the undead who look exactly like regular people but are eventually driven mad enough to kill.

One of the things that drew me to this visual novel was its assortment of animated backgrounds. They colourful and gorgeous. Every CG looks nice and coloured well, and the backgrounds for each area you visit are so beautiful and makes every single location easy to settle into. The cast is also surprisingly decent, where I expected to hate a few people but I ended up being okay with them because they were written well and weren’t as tropey as I had expected. I was also very pleased that the character that you were roleplaying as wasn’t skeezy when put into situations where he could have been, and that he treated the girls very well (though I won’t deny that there are some spots where behaviour was questionable but it doesn’t happen as often). Because the characters were written adequately enough, the game’s true ending route comes together very well and very naturally to a point where I could seriously believe that every character got along with one another to make sure the emotional impact of the mystery was satisfying.

In order to finish Worldend Syndrome, you have to do each route. A few characters’ routes don’t get unlocked until halfway through the game or even until the very end. The game also remembers everything you’ve done when it autosaves the system data on the world map, so if you need to reload a save to figure out someone’s schedule or if you mess up, it’s relatively easy to come back to something you’ve missed. I’ve played a lot of multiple route VNs before and Worldend Syndrome is easily one of the better VNs that allows the player to skip through to something they’ve missed or skip through previously-viewed text for another route.

As it is, Worldend Syndrome doesn’t really try to do anything spectacular, nor does it try to stand out like other visual novels of 2019 have (ie: Ciconia, presumably AI but I only tried the demo and I hated parts of the script, sorry). It does its job and tells its story which has a very good payoff in the end.

Judgement

I bought my fiancé Judgement earlier this year, as I had retired from playing Ryu ga Gotoku after Dead Souls/Ishin, and he was still playing the series religiously. I watched him play through part of it and I felt compelled to get my own copy because the combat looked nice, and the characters were compelling enough that I felt comfortable picking it up.

Judgement follows former lawyer Takayuki Yagami who is now a detective. His tale is one of redemption and conspiracies, reminiscent of some Phoenix Wright games (which this game gives clever nods to when the protagonist is in the courtroom). Yagami is more serious and down-to-earth than Kiryu is so the tone of the game feels quite different than other RGG games (or at least the ones I’ve played).

It still feels like a regular RGG game where you’re still wandering through Kamurocho, you’re still getting into fights with randos and Yakuza dudes, you date girls, you go to buy food, you play minigames, etc. But it isn’t as big as a standard RGG game; because you stay only in the one area, the cast is smaller, you get a job board to get your sidequests from, and the story itself is fairly short and sweet. I actually prefer that as a lapsed RGG player since it’s easier to get back into the games this way.

Judgement, however, disappointed me just a little in how little you spend in the courtroom. You’re given opportunities to present evidence, do some suspect tailing, use your smartphone to catch a cheating husband, or use a drone to search for evidence. I felt like when you had to use the drone to search for evidence, it ruined the pacing a little. The tailing missions are also reminiscent of Assassin’s Creed, and no that isn’t a good thing! Due to this, I felt like Judgement was not necessarily a great detective game but it did a decent job of trying to mold the RGG experience to a different main character.

Yagami can… fight… for some reason so he can beat up whatever randos come up to him on the streets. He’s actually more acrobatic than I remember Kiryu being in previous RGG games. He can kick off objects, he’s hard to back into a corner, he can do wall-flips, etc. It’s also much easier to earn XP where it’s all in one bar so you can do whatever you want to fill it up like play darts and just put stuff into his lockpicking. As a lapsed fan, the streamlining feels okay. The streamlining for combat also feels good because if you fights go on too long, the popo can come for you and you’d get fined, so emphasis is on finishing fights cleanly and quickly.

Overall, as a lapsed RGG fan, the way Judgement looks and feels and wraps up its twists and turns was really exciting for me. It may not have as many things to do as other RGG games, but honestly I think being a leaner experience was better and thus didn’t make the game overstay its welcome. I also am eagerly awaiting RGG7 since I enjoyed the demo a lot and I think the new protagonist can carry the series the way Yagami carried Judgement.

Cadence of Hyrule

Sometimes, after my fiancé and I bought our Switch, I’d wake up, go brush my teeth, and return to bed just to see my fiancé awake and playing Cadence of Hyrule. I was perplexed as it’s been ages since he’d willingly played a Zelda game, and his hands are super-huge for the joycons so he doesn’t like using them much.

You can easily say that Cadence of Hyrule is just a Crypt of the Necrodancer reskin with Zelda stuff all over it, but feels pretty clever in that it uses stuff from roguelikes and a rhythm game and makes the A Link to the Past world feel incredibly fresh. Bosses, especially, feel very fresh. Enemies move according to the rhythm and have a unique pattern that’s easily memorized so you can fall into the rhythm and take advantage of. If you’ve played Necrodancer, you’ll probably feel at home in this aspect, especially since the maps are also randomised (which leads different playthroughs feeling fresh).

The Zelda feels comes from recreating tunes from older Zelda games in puzzles, the magnificent sprite art, the great Zelda remixes, a simple-enough story, and a standard set of things to find in each procedurally generated dungeon. You also find a variety of traditional items like the bow, the bombs, boomerang… and a spear? It’s a nice blend of Zelda and Necrodancer.

The caveat is that it takes a little getting used to, since you’re not exactly used to not being able to freely move in a Zelda game. But when you do get used to it, it feels good. Everything is pretty expendable and if you die, you don’t feel like you necessarily lose a lot since you can accrue it all easily enough again. It’s unpredictable and that random roguelike nature is something that makes the Zelda experience feel fresh.

Spirit Hunter: Death Mark

My fiancé and I were trying to find spooky games to play for Halloween that wouldn’t make me squeamish because despite my profession dealing with analysis of body parts and human body fluids, I can’t see that kind of stuff on TV or in games in a realistic sense. It grosses me out. At least when it’s in front of me, it’s already out and off someone’s body and in a fume hood/biosafety cabinet and I didn’t have to see how it happened. My fiancé picked up Spirit Hunter: Death Mark on a sale we went through it together.

Death Mark is a tale about horror-themed urban legends and a curse that needs to be broken. People get marked with a crimson bite mark in the game’s H City and they eventually develop amnesia and die. A group of people live and gather at a spirit medium’s mansion (who is dead upon arrival). The only hint to break the curse in this mansion is a little talking doll named Mary. The protagonist eventually goes through several mysteries in an effort to break his curse and stop others from dying.

Death Mark does some surprisingly well-crafted worldbuilding. Each spirit you deal with has a well-told backstory, sometimes especially ghoulish (particularly the bonus post-game episode, the first episode, and the one episode with the telephone booth). The game excels with psychological horror and the enemies involved in each boss battle assist in making the player feel that way as well. The backgrounds also lend well to this as while they are simplistic, the shading and colours used help to execute a sense of dread. One particular chapter harkens back to Japan’s Aokigahara, and the backgrounds used connect very well to that particular location so that it feels super-eerie.

Regardless, Death Mark relies a lot on its text to establish its atmosphere and as someone who reads stuff like R07 VNs and other regular VNs with a lot of text, I was okay with that. The localization was well-done, albeit with some issues that would have been caught in editing but overall it carried the story very well.

There are boss battles prior to the end of each chapter, where you must use each item you find in your exploration segments. You need to use specific items in a specific order (even with the correct party setup) in order to achieve a good ending for that particular chapter (and thus eventually the game). I thought this was an interesting mechanic and while it got a little tired depending on the spirit, it showcased how creepy some of them can be on your screen.

Unfortunately, Death Mark does not have a variety for its soundtrack and it’s almost disappointing that the same piano tunes and boss themes played repeatedly as I felt it detracted from the experience.

Otherwise, I felt like Death Mark was a short and sweet horror experience that played into urban legends and folklore experiences. I loved the little vignettes that eventually ramped up to a central story point. I hope the sequel is good when we get around to it.

Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice

So my fiancé and I are doing this thing where we’ve started buying one copy of a game so we’d both own it together and go through it together. Sekiro and Man of Medan were two of those games this year.

Sekiro isn’t really like Souls. Eventually you’ll come to learn that very quickly when the game throws a boss at you and if you try to play like Souls, you’re not going to get the job done. It will show you that you never learned how to parry properly and you’re going to have to go back and learn it. Or if you didn’t grab a prosthetic that will make the job easier, you’re gonna have to do that too.

The game is interesting in that you aren’t exactly whittling down health bars all the time; you’re striking properly so you can overwhelm their posture bars, find an opening, and go in for the kill. Enemy health bars are essentially secondary to that posture bar. You have your own posture bar so you’ve got to learn how to parry properly. Sometimes you need to parry complete combos in order to deliver posture damage back to an enemy. It’s all about getting into the flow and rhythm of combat. And you must beat bosses in order for you to get a stat boost, so being able to beat a boss lies in your skill, and not necessarily your level/equipment.

Sekiro is Souls-like in its storytelling and worldbuilding. You can run around rooftops and areas to find secrets off the beaten path. You go back and forth between areas and speak to different NPCs to find out their backstories. The plot is also told via NPC conversations with the main characters. At first it’s a little dry but the story opens up eventually. It also has some great voiced NPCs for quests (one quest in particular had voicework that made me feel so sorry for the character that I was like “we need to get the proper item for this guy please don’t make him suffer”).

It feels rewarding to put in the work in order to beat the bosses, make it so you don’t resurrect as often to make people sick, and meet whatever standard Sekiro is throwing at you. It lets the player know that they’ve met that standard, and then throws another boss phase at them so you have to get even better.

Owl I’m looking at you.

Super Kirby Clash

My fiancé and I bought a Switch together this year (which, outside of dinner and movies and clothes, etc. was one of our major purchases together). We downloaded a few demos to try the control scheme out, including Super Kirby Clash. I am aware that this game is probably old, but hey it’s still going and it’s still being supported and I’m catching up.

I’m probably putting it here due to bias, but I think It’s really cute and the hats are super-adorable. I love getting new hats and new weapons for my little Kirby. It’s fairly standard as far as a “mobile experience” is concerned and playing it a little when I have the time to and hacking away at it little by little is rewarding when I get a new hat or new gear. My fiancé and I played it in multiplayer as well, which felt a lot like Kirby’s Return to Dream Land.

It’s pretty inoffensive and I haven’t paid real-life money for anything in it, and I still feel like I’m progressing. So as a Kirby game with light RPG elements (ie: something I’ve wanted for years and years), it’s nice to finally see realised.

Monster Boy and the Cursed Kingdom

An artist I commission very often from convinced me to move this game further up in queue than I originally had it when we were talking about games we were playing after finishing Shadowbringers’ main campaign.

Monster Boy and the Cursed Kingdom is the spiritual successor inspired by Wonder Boy III, with the formula being modernized for a new era. It feels fast, and it looks soooooooo pretty. The tracks are bumpin’ too. It’s also a little tough but with every difficult section successfully platformed through, you feel really good about it.

You play as a plucky boy named Jin whose uncle is an insano who turns everyone in the kingdom into animals. After you experience sweet freedom as a human boy platforming across things easily for like 15 minutes, Jin’s uncle turns him into a pig. Whoops. From there the platforming gets a little harder and you need to learn how to manipulate different forms and different spells in order to get across various sections.

Different animal forms give you different skills. Pig form allows you to sniff out secrets literally, snake form lets you cling to walls and go through tiny passages, frog has a sticky tongue for swinging, and lion form lets you go through obstacles. You need to use these forms well to platform well enough to get through each area and finish the game. Being successful at platforming in this game feels good and fulfilling and satisfying. As you unlock more, platforming experiences get more and more complex with more obstacles put in your way, so in essence it feels like the opposite of a standard metroidvania. Playing both Bloodstained and this in one year felt like playing polar opposites. That said, the checkpointing in Monster Boy is really good. Game Atelier knew what they were doing.

The bosses by contrast were really easy and it’s nice to take the time to look at the art for each boss. All of the effects are also super-nice. Playing Monster Boy on a 4K TV is quite a visual treat for its boss sections, its town section, and its platforming sections. The colours are off-the-charts. Each animal sprite has its own set of unique animations: the piggy farts and looks like >_>, froggy looking at flies, etc. And the music is so good. If this game were a 2019 game I’d definitely put its soundtrack on my list, but it isn’t. It’s a nice blend of new and old stuff and it’s a delight to hear in-context as encouragement to keep going when you fail a platforming section.

Monster Boy and the Cursed Kingdom is a faithful representation and homage of the old Wonder Boy games. It’s filled with references and secrets and awesome art, and I’m glad to have been convinced to move it up my queue for this year.

Most Disappointing Game: Final Fantasy XIV: Shadowbringers

I love Final Fantasy XIV. It’s brought me closer to so many people in recent years and I’ve met so many more through it. Playing this game means so much to me and I want the best for it for years to come. It’s one of the reasons why I’m so critical about it. If I hated this game, I would stop playing and honestly, I wouldn’t care about its future. I will say this before getting started: I like Shadowbringers’ story so far (we aren’t going to be finished with its story until 5.3). I don’t think It’s necessarily as consistent as Heavensward, but I think Shadowbringers’ story is the most Final Fantasy story we’ve gotten since perhaps FF10. Truly, it’s the best we’ve seen for the series this decade.

I had a lot of hopes and hype for Shadowbringers. I hated Stormblood, for a myriad of reasons: social reasons, gameplay reasons, and narrative reasons. The direction Shadowbringers was going and all the trailers made it seem like it was going to be fresh and exciting and new. My fiancé and I (and a few others) swapped servers+data centers in advance of the expansion for a fresh start, to boot. I watched the Job Actions trailer over and over and tried to decide what I was going to eventually main and gear up because I didn’t really have a main in Stormblood due to the combat changes and how easy things became for certain things.

During a live letter, they mentioned that they’re changing how things work in battle, and that’s when I became a little cautious. I was hoping for the best leading up to release and then I saw the scholar/healer changes and got very worried. I changed mains in Stormblood because playing Scholar was freaking horrible at the start of Stormblood.

I eventually had to change mains at the start of Shadowbringers because I was not having fun playing Scholar. For people who didn’t bother to level a healer at all, the writing was on the wall for healers during Stormblood. Essentially, it introduced an age of healing where you barely ever used your GCDs to heal. You mostly used OGCDs and preplanned shields. 90% of the time if you wanted to be a good healer, you’d mostly DPS. I don’t think I’ve cast a GCD heal at all in SB and ShB content unless things were going super-wrong.

The healing changes introduced in Shadowbringers made us think that things were going to change, that things were going to be harder to heal. I had my doubts, however, because all fights are scripted and if they were to introduce a substantial change to incoming damage, they would have to make it so most people (casual, midcore, hardcore, less experienced newbies, experienced folks) would be used to It and could handle it. There was no way they were going to introduce more difficulty given that subscription numbers were increasing.

And so, healers during Shadowbringers got some damage skills taken away, but in their place, they were given more tools to heal with:

- White Mage came away from this as a very well-rounded healer at launch. It had its damage spells, it had a damage spell with a stun, it finally had long-standing and easily useable mitigation, it has substantial MP recovery, and it has a damage spell that rewards you for using three GCD heals to make up for damage lost. White Mage still making out like a bandit in 5.1.

- Scholar felt dramatically different and didn’t feel as solid as it used to be. It had most of its damage tools taken away, the usefulness of its fairy was decreased because let’s be honest it was super-overpowered, it got one of its fairies and its AoE esuna taken away, and it was given its PvP move to act as an AoE that doesn’t have another effect. I had to completely unlearn everything I did as scholar in the last 5-6 years in order to play current scholar. Current 5.1 scholar is overpowered as heck and I don’t feel as satisfied to play it in SB/ShB content.

- AST LOL. All the cards are balance. MP regen is what. Heals are what. Everything is just what. Other fun skills were removed. That said, I really like AST just because it feels like I have to work twice as hard to achieve the same effect the other healers bring to the table.

So eventually with all of these changes, we had assumed that healing was going to be harder. It wasn’t. It’s the same experience and all we’re doing is pressing one single button all the time. I barely have to heal in dungeons. I barely have to heal in raid unless my party members step in stupid. I just can’t bring myself to play healer every single day anymore, and I love healing in this game. Or I loved it back when it was more dynamic. I just press one button over and over and over and over and over and maybe sometimes another but I just press one button a lot. It’s really sad and it makes me miss old Cleric Stance of all things.

I like Shadowbringers’ story. I felt rewarded playing through it as someone who’s played the game for years and did everything when it was in-content. So for me, it was like a good reunion. There were a lot of points where the story dragged or felt rocky. I felt like the start of the 5.0 campaign was utterly boring and poorly paced. It picked up again, then slowed down again, then picked up again, then got REALLY BAD, then picked up again for a good finish. I don’t think it’s as consistent as Heavensward’s 3.0 campaign, but it was very solid and made up for the 4.0 campaign.

However, story is only 20% of the experience for me. The rest of the time, I need to actually play the game. I actually liked the levelling and crafting changes and new skills they brought in during 5.0 because leveling a crafter never felt easier. I felt like I still had to work hard but the payoff came quickly and my macros still worked as well as they did from during Stormblood. I also used my Stormblood melds and Stormblood equipment for the entire levelling experience and had to make concessions for some of my macros as time went on. I still had to know what my skills did, basically. The 5.1 crafting/gathering changes kind of make me want to craft less since I don’t feel like I have to solve a puzzle anymore and to be honest, everyone crafts now so you make far less money than you previously did. The desynth changes also made it so that most of my markets tanked since what’s the point of gathering half the materials when desynth makes those materials easily accessible. I’m not saying to gatekeep at all, but I feel like the experience should have been a little harder (ie: like the Ixali experience where you had to learn what your skills did or desynth shouldn’t be this easy to keep the market fairly balanced). My server is a crafting server so I am more impacted in general from this. That said, I don’t have anything to spend gil on so it doesn’t matter, I guess. I just feel far less inclined to participate in what was one of my favourite pastimes in XIV.

I mained Ninja which got killed in 5.0. I was already dealing with the servers moving from East Coast to West Coast, so adding a bunch of stuff to squeeze into your TA window in 10 seconds in Shadowbringers utterly killed the job for me. 5.1 Ninja throws me off as someone who played this game since the time Ninja was introduced, and I can’t make myself play it. The current opener is the Doton opener (which is something I didn’t like in SB at all) and I can’t always rely on my tank to bring the thing to my Doton. That, and making it so you do different things per every other or every third TA just makes the job a little unpalatable for me at 80. I’m one of those people who wants TA to go. I don’t like that Ninja’s become the TA bot in recent years. I can still do well with it. People still throw buffs at me, but I don’t find enjoyment in the job anymore and I hope we get a proper retool in 6.0.

I switched back to ranged. Thankfully Bard hasn’t changed as much since SB (though I still prefer HW Bard like a weirdo), and Dancer is one of those “I worked too damn long today and I just wanna do the mindless brainless rotation” jobs. I miss old Machinist oddly enough. It felt really good when you played it well and pulled off a decent wildfire. Now it’s a little easier and I don’t feel as fulfilled playing it. That said, it’s probably the best incarnation of the job since it’s sad little introduction in 3.0.

Even tanking is substantially easier and that’s a mostly good thing. It sucked going into a low level dungeon and having trouble keeping aggro due to the level syncing and your DPS’ stats. Now you can just turn your stance on and go to town without losing any damage potency like you used to. I kind of miss swapping stances after I’ve established aggro though, because you could tell the difference between a good tank and a bad/less practiced tank if they didn’t bother to swap stances in a fight. Tanks came out of this expansion very balanced, though. They might need some work here and there (warrior I’m looking at you), but overall, they came out the best out of the three roles.

Other than that, you have monks not knowing what they should be, samurai continuously getting buffed and nerfed, black mage staying consistent, red mage being lol, summoner getting changed to the point where now it’s overpowered, among other DPS changes. DPS overall don’t have as much synergy so you can take any job you want to into raid and it’ll get the job done. That said if you want to do as much damage as possible, you’re generally going to take the same few classes into the raid if you’re less educated about them. And I feel like the lack of synergy or utility between classes or even the loss of something like mana shift makes the whole experience a little boring. It’s very “f you, I got mine” or the onus is on the player for their own personal burdens and no one’s really helping each other unless you’re a dancer, trick attack bot, dragoon or bard.

I really hope the other pieces of content are substantial but what I’ve seen aren’t exactly what I had in mind. Boss refights with an alternate version is really neat but I didn’t really want that for this raid tier. I wanted something more original given what we had to deal with in Omega. I don’t really care for the Nier Automata crossover because, again, I wanted something original to the XIV lore and the First. I think doubling down on Blue Mage is a bad idea and while some folks like its party-based content now, I can’t bring myself to keep doing the content given that it’s clear they don’t know what to do with it (or didn’t know what to do with it). With one dungeon coming per patch I have to question what’s happening internally or what they’re working on. I know SE is weird internally and I really hope that the kind of stuff I’ve read in previous postmortem articles isn’t happening.

Either way, I’m really disappointed that I want to stop playing XIV so much when it’s the most popular among my friends and followers because it’s so dissatisfying to me and it’s the most accessible that it’s ever been. I hope things get better eventually but going by what I think they have in store and their old reliable formula, I don’t have hope. I’m tired of the formula and I feel like it needs a shakeup. Overall, I’ve been less happy playing FFXIV than I’ve ever been and it makes me feel really sad.

#goty 2019#ciconia when they cry#bloodstained#the touryst#a short hike#worldend syndrome#judgment#cadence of hyrule#spirit hunter death mark#sekiro#super kirby clash#shadowbringers

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theoretical Frameworks in Alien (1979)

TW: Sexual assault, sexual themes

Alien (1979) is a film rife with sexual subtext. Swiss designer ‘Hans Rudolf Giger’ known better as ‘H.R Giger’ designed each set and character with a function, a certain practicality but also an overt sexuality. Giger’s work is macabre, it’s mechanical yet deeply sensual. The sexual underpinnings of the Xenomorph design extend to ‘LV-426’, the moon that our focal characters venture onto. As a result, the sexuality of Alien’s design philosophy imbues the film with distinct references to Freudian theory; namely, the uncanny.

Freud, in his 1919 essay Das Unheimliche, describes the uncanny as “that class of the terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar.” (Freud, 1919) Alien subverts expectations in a way that evokes the feelings and fears associated with the uncanny. It twists the conventions of male sexuality and repurposes them as the basis of its horror. Freud himself attributes castration anxiety in men to the idea that the vagina presents an uncanny form of the penis and Giger employs vaginal imagery in specific areas of the alien spacecraft found on LV-426 to evoke this.

The doors of LV-426 resemble the labia majora whilst the opening of the facehugger’s probe is designed to resemble the vagina. The facehugger’s probe is also phallic in nature and is the introduction to the persistent source of phallic imagery throughout the film – the lifecycle of the Xenomorph.

Part of the genius of Alien’s narrative is that it requires no exposition nor supplementary explanation. The viewer is exposed to the lifecycle of the Xenomorph directly as the story progresses and the three stages of life present sexuality imagery intended to attack the male audience.

Initially, the audience is presented with the Xenomorph egg as Nostromo crew member Kane ventures out to contact the alien ship. The opening of the egg resembles the labia.

Directly following this, Kane is attacked by a facehugger. The probe of the facehugger is phallic in nature and features an opening that resembles the vagina. The function of the facehugger also evokes fear of the uncanny via its reproductive mechanisms. The probe enters Kane’s throat, symbolising the brutal assault of rape, during which he is forcibly impregnated by eggs. The action is deeply sexual but also serves to inverse the conventional concept of pregnancy by making a man its host. The process of penetration resulting in impregnation is the basis of most reproduction amongst animals and humans alike and yet its presentation in Alien is perverse, invasive and attacks the male masculinity to evoke fear.

Next, the chestburster ruptures from Kane’s chest cavity. The form of the chestburster is phallic but this process continues to use an uncanny representation of pregnancy and birth as a source of terror. The bloodied chestburster resembles the fetus, birthed by a man and symbolic of his loss of the penis. Kane has lost his penis, and thus his masculinity, as a result of being overpowered and impregnated by the facehugger.

The final stage, the famous Xenomorph, presents a much sultrier depiction of the uncanny. The previous stages repurpose the male sexuality in ways indicative of body horror but the form of the Xenomorph is aesthetic. With a phallic head and sleek body, the serpentine movement of the Xenomorph provides beauty. It’s intriguing, it’s feminine and it’s perverse. It attacks the male sexuality by inviting men to engage with the seductive nature of the Xenomorphs’ form and contrasting this with a grotesque danger. H.R Giger describes his methodology when designing the Xenomorph and how he rejected the concept of an ugly monster “(The Xenomorph) can move gracefully, it can be sinuous.” (Williams, 2016)

Every stage of the Xenomorph’s birth cycle subverts the male sexuality to create the uncanny.

Conversely, the character of Ellen Ripley works to empower the Hollywood depiction of women by employing feminist perspective.

Anneke Smelik, film researcher at Radboud University, describes feminist film theory as criticizing “classical cinema for its stereotyped representation of women.” Smelik, Anneke. (2016).

As a warrant officer, Ellen Ripley is in a place of authority. The attempted invalidation of her authority is the catalyst for the events with the Nostromo. After Kane is assaulted by the facehugger, the other crew members attempt to recover him for placement on the ship. Ripley denies this request on the basis that this action could cause contamination due to the alien lifeform latched to Kane. Ash overrides this denial and allows for Kane to be brought onboard the Nostromo and, as Ripley had asserted, these actions introduced contamination and results in the eventual destruction of the Nostromo and its crew. This subverts the expectation of male authority and the male savior figure that is commonplace in films of its era.

This is compounded by Ripley’s direct comparison to another female character ‘Joan Lambert’. Lambert embodies the problematic female stereotype in a variety of ways throughout the film. She’s hysterical, she’s helpless and she’s callous. With the pressure mounting as the Xenomorph continues to ravage the dwindling crew, Lambert suggests escape via the ‘Narcissus’ with complete disregard for the fact that the remaining crew could not be accommodated. Lambert’s problematic traits result in the death of fellow crew member ‘Parker’ as he could not use his flamethrower on the Xenomorph in fear of killing Lambert who was paralyzed with fear. Overt femininity and dependence on a male savior are facets of a commonplace fantasy in male gaze cinema but, in this instance, it results in the death of the man. It’s a harsh critique on the nature of chauvinistic desires for female helplessness and submissiveness and Hollywood’s overdependence on the male savior complex.

Ripley embodies opposing traits; she’s independent, she’s determined and she’s in an administrative role where she has a voice. These are the traits that lead to her survival in the film as the ‘final girl’.

‘Final girl’ is a horror trope, most commonly associated with slasher films, wherein the character to overcome all odds and defeat the threat is a woman. Typically, this woman casts off femininity in favor of more male-applicable traits so as to appeal to the male audience. In her book, ‘Men, Women, and Chain Saws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film’ professor of film studies Carol J. Clover discusses male identification regarding the ‘final girl’ trope “At the moment that the Final Girl becomes her own savior, she becomes a hero; and the moment that she becomes a hero is the moment that the male viewer gives up the last pretense of male identification.” (Clover, 1993)

In addition to surviving against all odds, Ripley subverts sexual expectations also. She’s six feet tall, broad-shouldered and donning the correct uniform. Her body-type is not the curvaceous and voluptuous vessel of conventional beauty, as is often the case with male gaze cinema. She’s taller than her male counterparts and the final moments of the film subvert the voyeuristic pretenses that it originally constructs.

Ripley, having finally escaped the Nostromo, is undressing in preparation for cryosleep, a term used to describe being cryogenically frozen to allow for feasible transport across lightyears. She’s wearing a short vest top and underwear, white as a symbol of sexual purity, and the camera is distanced from her. It’s filmed in such a way to suggest that we are unseen spectators to Ripley’s undressing and the voyeuristic undertones are evident.

As we pull closer to Ripley, the moment is abruptly discontinued when the Xenomorph makes a surprise appearance aboard the Narcissus escape pod. Ripley is under threat once more, but the moment is more invasive and sexual. The Xenomorph draws closer to Ripley, unsheathing the phallic form of its inner mouth. Ripley opens the emergency hatch, allowing her to fire the harpoon gun at the Xenomorph and finally be rid of the threat. Ripley’s victory comes in the form of donning a phallic object and penetrating the Xenomorph with it. In that moment, she has taken the power and subverts male sexuality and asserts herself as an independent woman in control of her own sexuality.

The final moments of Alien also feature maternal abjection as a core theme. The brain of the Nostromo is a computer called ‘MU-TH-UR 6000’ but referred to only as ‘mother’ by the crew. The crew’s reliance on the computer called ‘mother’ establishes the theme of maternal abjection from the beginning. The computer being the core component of the ship is part of the theme of this abjection. The Xenomorph has the innate ability to become one with its environment and the presence of the threat’s symbiosis with the mother figure is literally driving the crew away; it represents the corruption of the paternal figure as it casts away those who seek its safety.

In addition to this, Ripley’s escape plan involves forcing the ship to overload via MU-TH-UR’s terminal. Upon trying to reverse these effects, once Ripley has extracted the coolant, the computer defies her and continues the self-destruct protocol regardless. Ripley’s frustration compels her to refer to MU-TH-UR as a “son of a bitch”. This represents a dichotomy of mother and daughter. They have both rejected one another and casted one another out.

Alien has always attracted academics to its subtext. It’s a classic horror film and papers cite its core themes to be Freudian or based on humanism or a depiction of otherness. Barbara Creed, professor of film studies, asserts that the chestburster scene is indicative of ‘primal scene’ and of “a common misunderstanding that many children have about birth, that is, that the mother is somehow impregnated through the mouth,” (Creed, 2019) This is featured in her book on the topic of similar theoretical frameworks ‘Horror and the Monstrous Feminine: An Imaginary Abjection’.

This is just one of many interpretations that exist to excite the minds of viewers. Filmmaker Quentin Tarantino discusses the abstraction of intention and reception regarding the meaning of art in a 2013 interview with Terry Gross on NPR “I mean, of course "King Kong" is a metaphor for the slave trade. I'm not saying the makers of "King Kong" meant it to be that way, but that's what, that's the movie that they made - whether they meant to make it or not.” (NPR, 2019)

Viewers will interpret art subjectively and, with studious justification, is it fair to say that any given interpretation can be deemed incorrect? Through the lens of society and psychology, these theoretical frameworks provide the literary basis for filmmakers to create and for film critics to critique - whether these frameworks were ever consciously included or not.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

WILD ARMS 2 - Golgotha Prison

The name is not subtle, but the reference itself is actually oddly superficial. At the end of the dungeon, Ashley is separated briefly from the party and Lilka and Brad are captured and tied to crosses, evoking the characters Dismus and Gestas, the thieves crucified during the same execution as the biblical christ. There is little reference to that actual narrative however, instead seeming to draw from the fact that the name Golgotha is taken to be an epithet to mean literally “A Place of Skulls,” which seems rather appropriate and obvious for an execution field.

Bookending the start and end of this dungeon, we fight the boss monster, Trask. First in a scripted “loss” and then in a solo match with Ashley’s new dark henshin hero form, the “Grotesque Black Knight,” Knightblazer.

“Trask” is yet another transliteration* issue that comes from the juggling between languages. It actually comes from the Tarrasque, another monster most readily identified from its appearance in the original Dungeons & Dragons Monster Manual, itself originally taken from semi-obscure French myth of Saint Martha of Bethany and the Tarasque of Tarascon.

*(I realize I use this word a lot and it might not be as common use to others. A “translation” lifts meaning between languages; a “transliteration” is to lift written characters between them. Example: “Left” in English translates to 左[the direction] or 残[what remains] but transliterates to レフト. Inversely 左 and 残 both translate back to English as “Left” but transliterate as “hidari” and “zan” respectively; and レフト transliterates back into English as “refuto.”)

Surprisingly, the Wild Arms 2 design (which would also go on to persist as the core design throughout the rest of the Wild Arms series) is based more on the original myth than the D&D representations tend to be: While the end product looks nothing like the depictions of the Tarasque of myth, it retains the spiked turtle shell, the prominent dual horns, poisonous quality, and fins on its head here account for being “half fish.”

Also of note is that the title card identifies it as a “Dragonoid” and it has various metallic and machine-like features. These details are neat because it positions it as being not-quite a dragon, to work around a fact that will pop up much later: That dragons in Filgaia are extinct. And also to play into the fact that Dragons in Wild Arms are semi-mechanical lifeforms.

In any case, our scripted loss to Trask the first time around ends with the team knocked out and imprisoned in what appears to be a disused execution ground and associated holding cells. In our escape we run into monsters fitting the theme, who appear to be natural inhabitants, rather than guards put in place by the Odessa terrorist soldiers who are actually holding us here.

First up is the Wight, a classic undead warrior monster generally taken from D&D, but with a little more behind it than you might expect. The term Wight in English lore actually traces back quite far as an archaic term with little to no real association with monsters. The real intersection with name and subject comes from an early English translation of the Nordic Grettis Saga; In it the zombie-like creatures now better known as Draugr were referred to as apturgangr (lit.”againwalker”) but were translated as Barrow-wight. (lit.”[burial-]mound person”)

This may seem an odd choice, but the translation came at the hands of the eminent bookman William Morris. I say “bookman” because he was not just a prolific author of prose and poetry, but a pioneer of the revival of the British textile and printing industry. He and his wife, Jane Burden, did extensive arts, craft and design work in book and print design, book binding, and wall paper all stemming from the intricate design of modular and tiled printing blocks and stamps. Oh and he translated various works of epic poetry and myth into English, including old Roman epics, French knightly romances, and of course Norse sagas. (all of which he wrote and published what was basically fanfiction of, btw)

His seemingly erroneous “translation” of the Barrow-wight came as an attempt to reflect a comparable agedness to the name: Rather than translating from old Norse into modern English, he chose what he thought a suitable old English equivalent; “Barrow” referring to pre-christian Anglo-Saxon burial mounds, and “Wight” meaning “thing” or “creature” but often used disparagingly to refer to a person. The nuance there is actually quite clever, as the old Wight referred pretty exclusively to those living, even if it didn’t specify by definition, and that uncertainty or contradictory kind of implication uniquely fits a description of the undead.

This term would be picked up by J.R.R. Tolkein for use in Middle-Earth, retaining their lore and function from Norse legend to describe undead warriors. And from there you can follow the usual chain of influence to D&D, where the shortened term Wight really solidified itself as synonymous with the undead, and eventually down to Game of Thrones, where George R.R. Martin cleverly brings the whole thing back around to old risen bodies of northern warriors, not unlike the Draugr of Norse myth.

Anyway in Wild Arms 2 we get some sorta death yeti ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Next up is the Ghoul, which I think we all know is a pretty generic term in modern parlance, but it’s specific origins date back to pre-Islamic Arabia. It entered into English via translations of the original French translation of 1001 Arabian Nights, where it appears in one story as a monster lurking about the cemetery devouring corpses.

The Ghoul identity as a corpse eater quickly broadened into flesh eaters, and the association with lurking about graves in turn marked them as undead themselves until eventually the term became loosely applied to any variety of undead, including the thrall of vampires, supplanting the flesh of the dead with blood of the living and achieving a truly far removed meaning. Even in modern Arabic the term now broadly applies to any number of fantasy monsters.

And so long as we’re dabbling in pop culture transplants; the Arabaian word Ghul is in fact the same used in the name of the Batman villain, R’as al-Ghul, whose name/title has always been erroneously translated as “Head of The Demon.“

I have no idea why it’s a chicken with a mohawk but i love it

And finally the Bone Drake. I don’t know that this one actually has any real specific lineage...

“Drake” is generally a synonym for dragon, although there is some case of fantasy semantics where different settings will try to define distinct body types of dragons each with their own name, in which case Drakes are often either dragons which simply don’t exceed a certain size (generally no bigger than a non-magical animal such as a dog or a horse) or a wingless variation of whatever the setting’s prototypical dragon might be. I don’t know for certain, but I think this distinction in modern fantasy started with Tolkien’s wingless fire breathing dragon, Glaurung, and its offspring who were referred to as fire-drakes.

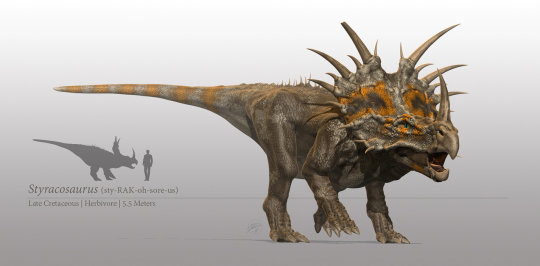

In any case, the specific term “Bone Drake” Doesn’t seem to appear with any visibility prior to Wild Arms 2, which leads me to believe it was just their name for a generic bone dragon-like creature. It does make for an interesting companion, aesthetically, to Trask being here, although there don’t seem to be any implications that Trask lives in this dungeon at all. Other than just being an obvious combination of cool fantasy things, it may also be pulled from Dungeon & Dragons’ Dracolich/Night Dragon; an undead (often skeletal) dragon raised from the dead, often by their own necromantic spells, hence the term “Lich.” For whatever reason they are oddly reminiscent of shield crested dinosaurs like the Triceratops or Styracosaurus.

The attack Rhodon Breath doesn’t tell me anything either. I think it’s just meant as “Rose Breath,” translating the “Rhodon” bit pretty literally, and references the smell of roses being present as a funeral, or else the palor of the faded pink color also called “Rose Breath.” There is some apocryphal reference to a Rhodon but of no significance that I can tell.

Clearly the theme here is death and the undead, and with some small stretch on part of the Wight, we could even say skulls all befitting Golgotha’s “Place of Skulls” epithet. It’s a really neat way to build this dungeon, albeit a little on the nose. But I really like the idea that the dungeon appears to be abandoned and now haunted by all these reanimated corpses and bones before the villains arrive to use it for their plans. Oddly there isn’t much of a martyrdom theme here, although we’ll get plenty of that a little later once we recruit our second magic user, summoner, christ figure, and perfect beautiful boy, Tim Rhymless to the team...

Anyway we get out, we fight Trask for real. Ashley turns into a saturday morning superhero. Trask gets solo’d. And we all just kinda move along without asking too many questions... Although the game dialogue describes this new form as a “grotesque black knight” the sprite work, 3D model, and even original character art don’t really convey much in the way of “grotesque” but in the context of the tokusatsu, henshin hero elements it’s not too hard to imagine that the design was meant to evoke a similar aesthetic to gruesome suit heroes like Guyver, Kamen Rider Shin, and Devilman. I do love the gill/tendon-like organic vent structure in the pauldrons that stay. And although it’s not visible in any of these images, but the D-Arts model has an exposed segment of vertebrae between the shoulders; that along with the teeth(?)/ribs on the open chest panels really helps bring out more of the “grotesque” quality of the design.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Endless Night Class

If you’re interested in studying game design, Atlus has provided a rare (possibly unique) opportunity in their Persona Endless Night Collection.

Be warned: I’m about to spend a lot of words advocating that you acquire, play extensively, and critically examine their three Persona dancing games. I’m in no way associated with (and have never been associated with) Atlus. Nor am I an evangelist for any of these three games individually (though I do enjoy them). Taken together, though, I think they prove both fascinating and illuminating, and it’s rare to find a series as odd as this collected like this.

I provide some possible alternatives for similar exercises at the bottom of the post.

For the uninitiated, Atlus released a beatmatch game for the Vita a few years back based on the fourth of their teenage dating-sim slash Jungian dungeon delve Persona games: Persona 4: Dancing All Night. (I’ll be calling this P4D.)

I’m personally a big fan and played the crap out of it for months. Which is not to say that it’s without some pretty significant flaws.

A few weeks ago, they released their follow-up(s), Persona 3: Dancing in Moonlight (P3D) and Personal 5: Dancing in Starlight (P5D).

The fact that any of these games exist at all is pretty weird. They’re beatmatch games that serve as spin-offs (and in two out of three cases, sequels) to narrative focused hundred-hour RPGs, each themed around dancing, despite the fact that dancing is in no shape, form, or fashion important to the core games.

Stranger still, the two new releases are essentially the same game from both a systemic and narrative perspective. The characters are different, the music is different, the UI is different, but essentially everything else - the mechanics, the UX, the inciting narrative, the way story content is accessed, the loot - is exactly the same.

Essentially Atlus made two games worth of content for the exact same “engine” and released them at the same time. It’s a little as if Fallout 3 and Fallout New Vegas had been released on the same day (had New Vegas not made any modifications to Fallout 3′s gameplay systems).

But here’s the kicker: for $100, you can get the “Endless Night Collection,” which contains both of the new releases and a code for the digital version of the original Dancing All Night (for PS4, if you get the PS4 bundle).

In other words, for $100 you get:

A game from mid-2015 developed for the Vita.

A follow-up to that game based on a different property developed for simultaneous release on PS4 and Vita.

A second follow-up to that game based on yet a different property developed for simultaneous release on PS4 and Vita, to be released at the same time as the above.

In addition to which, one of the two new games is a spin-off of a 12 year-old PS2 game while the other is a spin-off of a game that released last year.

That’s a whole lot of design from a whole lot of sources over a pretty long time kind of piled up on top of itself.