#this is a still a little wonk but less wonk than the last one. progress.

Note

If you're still doing art asks. A smidgen of your pacific rim Johnny? O-O

Prepare thyself for battle... ✨️In style✨️

This has given me a Mighty Need to draw more pacrim stuff,,,, hmm

#hyper-hellfire#ghost rider#johnny blaze#ghost rider pacific rim au#asked and answered#my art#this is a still a little wonk but less wonk than the last one. progress.#the whole reason i got a new computer is A) its rly slow but once i get used to it again itll be fine but b) it only has 2 usb ports#so its either unplug my keyboard or my mouse and#i am far too indecisive to live w/o my ctrl+T#so i am Mouseless which makes zooming. a challenge#but Still We Move#anyway tech rant over look at the Guy!!

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Value-based care – no progress since 1997?

By MATTHEW HOLT

Humana is out with a report saying that its Medicare Advantage members who are covered by value-based care (VBC) arrangements do better and cost less than either their Medicare Advantage members who aren’t or people in regular Medicare FFS. To us wonks this is motherhood, apple pie, etc, particularly as proportionately Humana is the insurer that relies the most on Medicare Advantage for its business and has one of the larger publicity machines behind its innovation group. Not to mention Humana has decent slugs of ownership of at-home doctors group Heal and the now publiciy-traded capitated medical group Oak Street Health.

Human has 4m Medicare advantage members with ~2/3rds of those in value based care arrangements. The report has lots of data about how Humana makes everthing better for those Medicare Advantage members and how VBC shows slightly better outcomes at a lower cost. But that wasn’t really what caught my eye. What did was their chart about how they pay their physicians/medical group

What it says on the surface is that of their Medicare Advantage members, 67% are in VBC arrangements. But that covers a wide range of different payment schemes. The 67% VBC schemes include:

Global capitation for everything 19%

Global cap for everything but not drugs 5%

FFS + care coordination payment + some shared savings 7%

FFS + some share savings 36%

FFS + some bonus 19%

FFS only 14%

What Humana doesn’t say is how much risk the middle group is at. Those are the 7% of PCP groups being paid “FFS + care coordination payment + some shared savings” and the 36% getting “FFS + some share savings.” My guess is not much. So they could have been put in the non VBC group. But the interesting thing is the results.

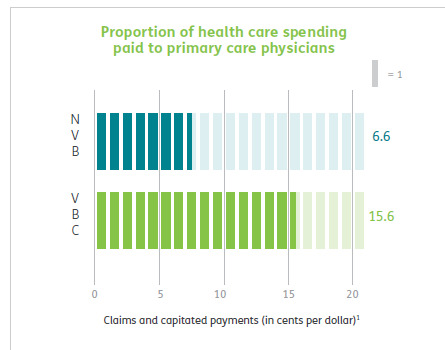

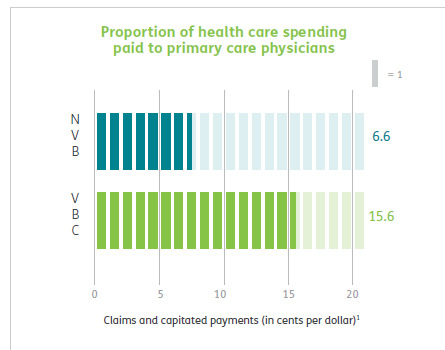

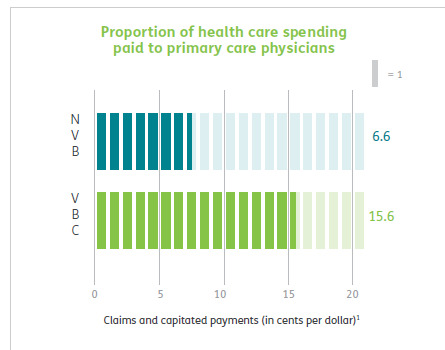

First up Humana is spending a lot more on primary care for all their VBC providers, 15% of all health care spend vs 6.6% for the FFS group, which is more than double. This is more health policy wonkdom motherhood/apple pie, etc and probably represents a lot of those trips by Oak Street Health coaches to seniors houses fixing their sinks and loose carpets. (A story often told by the Friendly Hills folk in 1994 too).

But then you get into some fuzzy math.

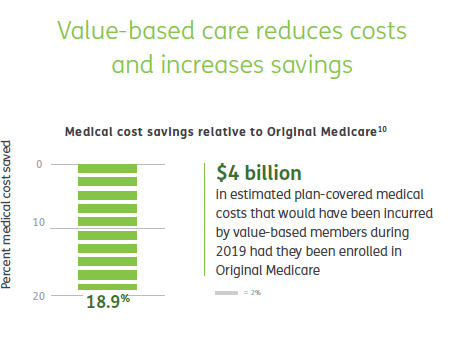

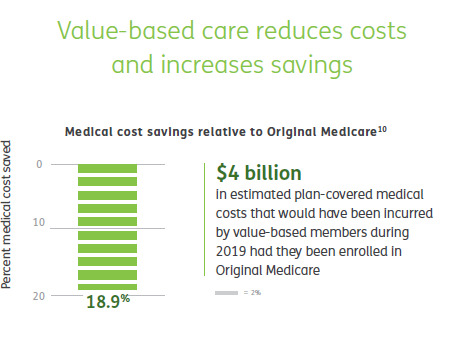

According to Humana their VBC Medicare Advantage members cost 19% less than if they had been in traditional FFS Medicare, and therefore those savings across their 2.4m members in VBC are $4 billion. Well, Brits of a certain age like me are wont to misquote Mandy Rice-Davis — “they would say that wouldn’t they”.

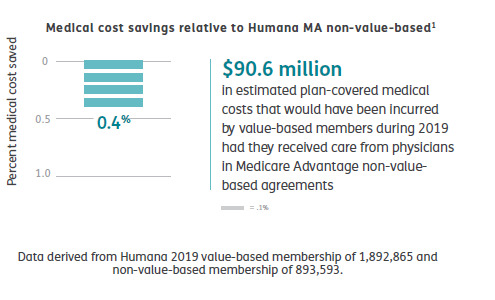

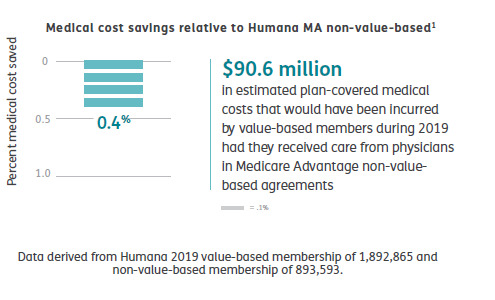

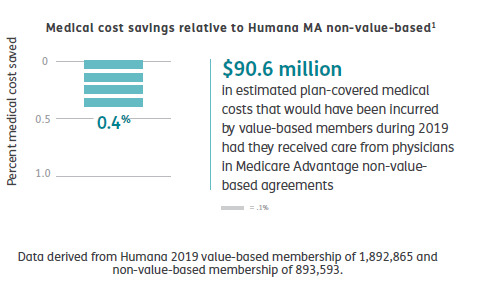

But on the very same page Humana compares the cost of their VBC Medicare Advantage members to those 33% of their Medicare Advantage members in non-VBC arrangements. Ponder this chart a tad.

Yup, that’s right. Despite the strung and dram and excitement about VBC, the cost difference between Humana’s VBC program and its non-VBC program is a rounding error of 0.4%. The $90m saved probably barely covered what they spent on the fancy website & report they wrote about it

Maybe there’s something going on in Humana’s overall approach that means that FFS PCPs in Medicare Advantage practice lower cost medicine that PCPs in regular ol’ Medicare. This might be that some of the prevention, care coordination or utilization review done by the plan has a big impact.

Or it might be that the 19% savings versus regular old Medicare is illusionary.

It’s also a little frustrating that they didn’t break out the difference between the full risk groups and the VBC “lite” who are getting FFS but also some shared savings and/or care coordination payments, but you have to assume there’s a limited difference between them if all VBC is only 0.4% cheaper than non-VBC. Presumably if the full risk groups were way different they would have broken that data out. Hopefully they may release some of the underlying data, but I’m not holding my breath.

Finally, it’s worth remembering how many people are in these arrangements. In 2019 34% of Medicare recipients were in Medicare Advantage. Humana has been one of the most aggressive in its use of value based care so it’s fair to assume that my estimates here are probably at the top end of how Medicare Advantage patients get paid for. So we are talking maybe 67% of 34% of all Medicare recipients in VBC, and only 25% of that 34% = 8.5% in what looks like full risk (including those not at risk for the drugs). This doesn’t count ACOs which Dan O’Neill points out are about another 11m people or about 25% of those not in Medicare Advantage. (Although as far as I can tell Medicare ACOs don’t save bupkiss unless they are run by Aledade).

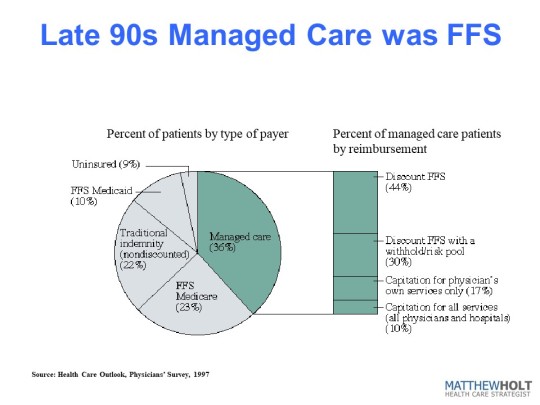

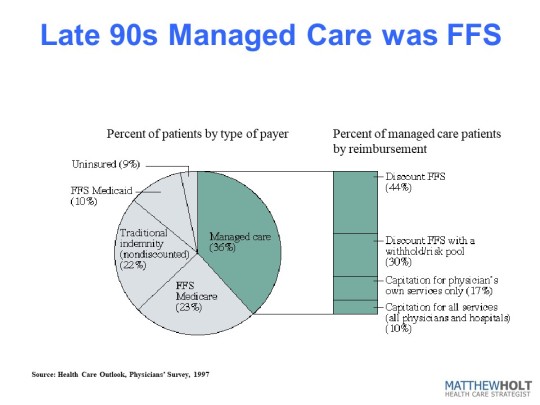

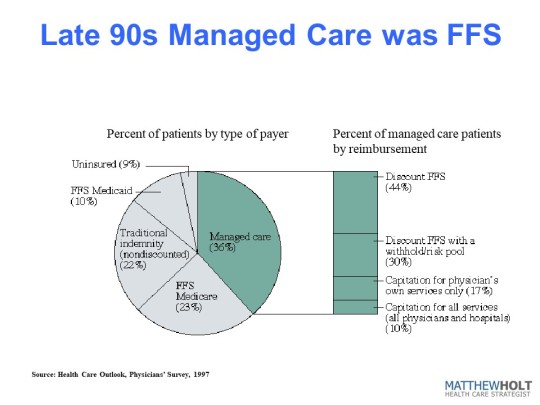

I did a survey in 1997 which some may recall as the height of the (fake) managed care revolution. Those around at the time may recall that managed care was how the health insurance industry was going to save America after they killed the Clinton plan. (Ian Morrison used to call this “The market is working but managed care sucks”). At the time there was still a lot of excitement about medical groups taking full risk capitation from health plans and then like now there was a raft of newly publicly-traded medical groups that were going to accept full risk capitation, put hospitals and over-priced specialists out of business, and do it all for 30% less. The Advisory Board, bless their very expensive hearts, put out a report called The Grand Alliance which said that 95% of America would soon be under capitation. Yeah, right. Every hospital in America bought their reports for $50k a year and made David Bradley a billionaire while they spent millions on medical groups that they then sold off at a massive loss in the early 2000s. (A process they then reversed in the 2010s but with the clear desire not to accept capitation but to lock up referrals, but I digress!).

In the 1997 IFTF/Harris Health Care Outlook survey I asked doctors how they/their organization got paid. And the answer was that they were at full risk/capitation for ~3.6% of their patients. Bear in mind this is everyone, not just Medicare, so it’s not apples to apples with the Humana data. But if you look at the rest of the 36% of their patients that were “managed care” it kind of compares to the VBC break down from Humana. There’s a lot of “withholds” which was 1990s speak for shared savings and dscounted fee-for-service. The other 65% of Americans were in some level of PPO-based or straight Medicare fee-for-service. Last year I heard BCBS Arizona CEO Pam Kehaly say that despite all the big talk, the industry was at about 10% VBC and the Humana data suggests this is still about right.

So this policy wonk is a bit depressed, and he’s not alone. There’s a little school of rebels (for example Kip Sullivan on THCB last year) saying that Medicare Advantage, capitated primary care and ACOs don’t really move the needle on cost and anyway no one’s really adopted them. On this evidence they’re right.

Matthew Holt is the Publisher of THCB and is still allowed to write for it occasionally

Value-based care – no progress since 1997? published first on https://wittooth.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

Value-based care – no progress since 1997?

By MATTHEW HOLT

Humana is out with a report saying that its Medicare Advantage members who are covered by value-based care (VBC) arrangements do better and cost less than either their Medicare Advantage members who aren’t or people in regular Medicare FFS. To us wonks this is motherhood, apple pie, etc, particularly as proportionately Humana is the insurer that relies the most on Medicare Advantage for its business and has one of the larger publicity machines behind its innovation group. Not to mention Humana has decent slugs of ownership of at-home doctors group Heal and the now publiciy-traded capitated medical group Oak Street Health.

Human has 4m Medicare advantage members with ~2/3rds of those in value based care arrangements. The report has lots of data about how Humana makes everthing better for those Medicare Advantage members and how VBC shows slightly better outcomes at a lower cost. But that wasn’t really what caught my eye. What did was their chart about how they pay their physicians/medical group

What it says on the surface is that of their Medicare Advantage members, 67% are in VBC arrangements. But that covers a wide range of different payment schemes. The 67% VBC schemes include:

Global capitation for everything 19%

Global cap for everything but not drugs 5%

FFS + care coordination payment + some shared savings 7%

FFS + some share savings 36%

FFS + some bonus 19%

FFS only 14%

What Humana doesn’t say is how much risk the middle group is at. Those are the 7% of PCP groups being paid “FFS + care coordination payment + some shared savings” and the 36% getting “FFS + some share savings.” My guess is not much. So they could have been put in the non VBC group. But the interesting thing is the results.

First up Humana is spending a lot more on primary care for all their VBC providers, 15% of all health care spend vs 6.6% for the FFS group, which is more than double. This is more health policy wonkdom motherhood/apple pie, etc and probably represents a lot of those trips by Oak Street Health coaches to seniors houses fixing their sinks and loose carpets. (A story often told by the Friendly Hills folk in 1994 too).

But then you get into some fuzzy math.

According to Humana their VBC Medicare Advantage members cost 19% less than if they had been in traditional FFS Medicare, and therefore those savings across their 2.4m members in VBC are $4 billion. Well, Brits of a certain age like me are wont to misquote Mandy Rice-Davis — “they would say that wouldn’t they”.

But on the very same page Humana compares the cost of their VBC Medicare Advantage members to those 33% of their Medicare Advantage members in non-VBC arrangements. Ponder this chart a tad.

Yup, that’s right. Despite the strung and dram and excitement about VBC, the cost difference between Humana’s VBC program and its non-VBC program is a rounding error of 0.4%. The $90m saved probably barely covered what they spent on the fancy website & report they wrote about it

Maybe there’s something going on in Humana’s overall approach that means that FFS PCPs in Medicare Advantage practice lower cost medicine that PCPs in regular ol’ Medicare. This might be that some of the prevention, care coordination or utilization review done by the plan has a big impact.

Or it might be that the 19% savings versus regular old Medicare is illusionary.

It’s also a little frustrating that they didn’t break out the difference between the full risk groups and the VBC “lite” who are getting FFS but also some shared savings and/or care coordination payments, but you have to assume there’s a limited difference between them if all VBC is only 0.4% cheaper than non-VBC. Presumably if the full risk groups were way different they would have broken that data out. Hopefully they may release some of the underlying data, but I’m not holding my breath.

Finally, it’s worth remembering how many people are in these arrangements. In 2019 34% of Medicare recipients were in Medicare Advantage. Humana has been one of the most aggressive in its use of value based care so it’s fair to assume that my estimates here are probably at the top end of how Medicare Advantage patients get paid for. So we are talking maybe 67% of 34% of all Medicare recipients in VBC, and only 25% of that 34% = 8.5% in what looks like full risk (including those not at risk for the drugs). This doesn’t count ACOs which Dan O’Neill points out are about another 11m people or about 25% of those not in Medicare Advantage. (Although as far as I can tell Medicare ACOs don’t save bupkiss unless they are run by Aledade).

I did a survey in 1997 which some may recall as the height of the (fake) managed care revolution. Those around at the time may recall that managed care was how the health insurance industry was going to save America after they killed the Clinton plan. (Ian Morrison used to call this “The market is working but managed care sucks”). At the time there was still a lot of excitement about medical groups taking full risk capitation from health plans and then like now there was a raft of newly publicly-traded medical groups that were going to accept full risk capitation, put hospitals and over-priced specialists out of business, and do it all for 30% less. The Advisory Board, bless their very expensive hearts, put out a report called The Grand Alliance which said that 95% of America would soon be under capitation. Yeah, right. Every hospital in America bought their reports for $50k a year and made David Bradley a billionaire while they spent millions on medical groups that they then sold off at a massive loss in the early 2000s. (A process they then reversed in the 2010s but with the clear desire not to accept capitation but to lock up referrals, but I digress!).

In the 1997 IFTF/Harris Health Care Outlook survey I asked doctors how they/their organization got paid. And the answer was that they were at full risk/capitation for ~3.6% of their patients. Bear in mind this is everyone, not just Medicare, so it’s not apples to apples with the Humana data. But if you look at the rest of the 36% of their patients that were “managed care” it kind of compares to the VBC break down from Humana. There’s a lot of “withholds” which was 1990s speak for shared savings and dscounted fee-for-service. The other 65% of Americans were in some level of PPO-based or straight Medicare fee-for-service. Last year I heard BCBS Arizona CEO Pam Kehaly say that despite all the big talk, the industry was at about 10% VBC and the Humana data suggests this is still about right.

So this policy wonk is a bit depressed, and he’s not alone. There’s a little school of rebels (for example Kip Sullivan on THCB last year) saying that Medicare Advantage, capitated primary care and ACOs don’t really move the needle on cost and anyway no one’s really adopted them. On this evidence they’re right.

Matthew Holt is the Publisher of THCB and is still allowed to write for it occasionally

Value-based care – no progress since 1997? published first on https://venabeahan.tumblr.com

0 notes

Note

Cloud x Lea

send me a ship and i’ll tell you

who hogs the duvetneither, tbh, as cloud nor lea are really susceptible to cold. chances are the duvet is actually going to end up somewhere at the foot of the bed instead while they’re basically just sprawled one on top of the other – either that, or twisted around whomever is lying on top.

who texts/rings to check how their day is goingi’d say lea might do it more at the start, but as their relationship progresses they’ll both end up doing it. followed by a whole slew of dirty texts.

who’s the most creative when it comes to giftsnot really sure - lea just tends to give gifts that remind him of cloud and most of the time he doesn’t really stop to think about whether or not it’s creative. i kind of see cloud as being the same type of gift giver in that regard.

who gets up first in the morninglea, much like axel, is still quite notorious for loving sleep; if there is any possibility of sleeping in, he’ll take it. for that reason, i actually see cloud as the one usually getting up first, even going as far that cloud will mostly be the one to pester lea to get up so he gets to his training on time.

who suggests new things in bedat first probably cloud, though considering the fact they have sex … a lot … after hurdling past that first time, and it definitely tends to border on kinky sometimes i’d say they both give quite a bit of uh, input on what goes on in the bedroom.

who cries at movieslea, probably. he still doesn’t really have a lot of control over his emotions and thus they come to the surface a lot quicker than with cloud who’s basically turned stoicism into an art form.

who gives unprompted massageslea. his hands are better than hot stones and he likes the way cloud reacts to it.

who fusses over the other when they’re sickthey both fuss over each other, though cloud’s more of a ‘tough love’ type of person, which works out well because lea’s a grump when he’s sick and he’ll stubbornly keep going about his day anyway unless someone orders / bullies him into slowing down.

who gets jealous easiesthonestly, they mark each other all the time. they’re both possessive bastards. that said, lea will probably hide it less; or be less good at hiding it than cloud, if it comes down to it.

who has the most embarrassing taste in musicthis will most likely also be lea … i mean, perhaps it wouldn’t exactly be embarrassing but it’ll certainly be quite eclectic especially at the restart of his existence as a somebody ; he has to catch up on all the joys he missed out on while he was a nobody. i could see him being into bubbly pop songs, though. pls.

who collects something unusualcloud likes to collect wood ( wink wonk ;DDDD ) carvings, or wood pieces with which he can make his own carvings, whereas lea doesn’t really collect anything in particular … except for perhaps ice cream sticks so he can finally get his hands on that damn easter statue tissue dispenser :||| so i guess lea does win this round after all.

who takes the longest to get readywell lea’s the one wearing the guyliner in this relationship, so …

who is the most tidy and organisedcloud, probably. that isn’t to say lea’s a total slob, but he does still have more of a teenage boy mentality ( that is to say, he tends to act like a frat boy a bit more than cloud does… )

who gets most excited about the holidayslea. dressing up for hallowe’en? count him the fuck in. giving gifts to the people he cares for during christmas? heck yeah! doing that cheesy new year’s kiss and the new year’s resolutions he’s only gonna hold on to for a week tops? been there done that!! EASTER EGG HUNT? he’s a goddamn pro. that isn’t to say cloud doesn’t enjoy celebrating the holidays, but he wouldn’t show as much excitement about it as lea.

who is the big spoon/little spoonmost of the time it’s lea as big spoon and cloud as little spoon.

who gets most competitive when playing games and/or sportsboth, okay. cloud may look stoic and unflappable, but challenge him and he’s gonna wreck your ass just to prove a point ; especially on the battle field … and lea is well … lea. :| need i say more?

who starts the most argumentsthey’re both stubborn and can both be argumentative so i don’t think there’s someone that would start more arguments than the other? the only difference would be that lea’s more prone to explosive bursts of anger that last shorter whereas cloud is more prone to that kind of silent, slow burning anger that makes him pull away, become kind of cold and aloof and short, like at the start of their acquaintance.

who suggests that they buy a petlea :|

what couple traditions they havethere’s this spot in the mountains surrounding hollow bastion where they go to whenever one of them can’t sleep, so they can watch the sunrise together. also lea tends to cook for cloud whenever he knows the other’s coming back from an exhausting day. when one of them is off-world, they try and text each other good morning or good evening at the very least, even if there’s not much time to text anything else.

what tv shows they watch togetherlook i’m not saying lea is into trash tv, but … he’s into trash tv. soap operas are a guilty pleasure, along with such riveting reality tv shows like family feud, judge judy, jerry springer, dr phil. at least everyone who appears on those shows as guests are infinitely bigger Tragedies™ than he is even with his past. cloud’s more of an old-school drama shows kind of guy. they like watching tv together whenever they can though - what they watch probably depends on what’s on.

how they spend time together as a couplethey train together quite often and otherwise just hang out either at cloud’s place ( preferable, there’s less neighbours … ) or lea’s place just relaxing together whenever they can. days they can spend together are few and far in between anyway, what with lea training to become keyblade master in the upcoming war and cloud helping leon & co. with the hollow bastion restoration effort. so whenever they do get time together, they usually just spend it at home, being lazy and enjoying each other’s presence.

who made the first movecloud. lea wasn’t confident enough to do so yet at that point, or at least not confident or well-versed enough in reading cloud’s emotions/moods to run the risk of ruining the friendship they’d managed to build against the odds.

who brings flowers homeneither are really the bring flowers home types … if one of them brings flowers home it’s probably because aerith bullied them into doing so.

who is the best cooklea, hands down.

#kyouminaine#cut it because it got quite long#♡. you scraped your body against mine like a matchstick begging for a fire ( cloud x lea )#here we are got a tag!#HEADCANON

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The outlook is dim for Americans without college degrees

AMERICA’S AGEING economic boom can still produce pleasant surprises. Companies added an astonishing 312,000 new jobs in December, the Bureau of Labour Statistics reported on January 4th, and raised pay at the fastest clip in years. For the third of working-age Americans without any college education, such spells of rapid income growth have been exceedingly rare, not only since the financial crisis but in the past half-century. But however long this expansion lasts, their economic prospects still look grim.

The misfortunes of the left-behind were a recurring topic at this year’s meeting, in Atlanta, of the American Economic Association, one of the biggest annual convocations of economists. David Autor of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology offered the most pointed characterisation, drawing on forthcoming research co-authored with Juliette Fournier, also of MIT. The earnings of workers without a college education have scarcely risen in 50 years, after adjusting for inflation; for men they have fallen. This stagnation coincided with tectonic changes in American employment. The share of jobs that require either a lot of training, or very little, has grown since 1970. Much of the production and office work that requires moderate training, which once employed vast numbers of workers without college degrees, has disappeared, either shipped abroad or offloaded on robots and computers. The resulting hardship has been implicated in a rise in mortality in parts of America and a turn toward angry nationalism that helped put Donald Trump in the White House.

Get our daily newsletter

Upgrade your inbox and get our Daily Dispatch and Editor's Picks.

Working out what to do about those left behind by economic progress is becoming an obsession of policy wonks. Mr Autor and Ms Fournier provide important new context. In the 1950s, they show, there was almost no relationship between how densely populated a place was and the share of its residents with college degrees. That has changed utterly: the share of the working-age population with a college degree is now 20 percentage points higher in urban places than it is in rural ones. In 1970 that gap was just five percentage points. Several decades ago mid-skilled work was clustered in big cities, while low-skilled work was most prevalent in the countryside. No longer; those mid-skilled jobs that remain are more likely to be found in rural areas than in urban ones.

As the geographical pattern of work has shifted, so has that of wages. Economists have long acknowledged the existence of an urban wage premium: workers in more densely populated places earn more, in part because of the productivity benefits of crowding together that nurture urban growth in the first place. This pay premium used to hold across the range of skills. In 1970 workers without any college education could expect to get a boost to their earnings when they moved to a big city, just as better-educated workers did. Since then the urban wage advantage for well-educated workers has become more pronounced, even as that for less-educated workers has all but disappeared.

Economists seeking to explain why poorer Americans are not moving to find better opportunities should take note, Mr Autor mused in his lecture. Explanations for falling mobility in America generally focus on obstacles to migration—expensive urban housing, location-specific occupational licences, varying government benefits and so on. These no doubt matter, but they may not be the whole story. Often, people may be staying where their economic prospects are best.

That is clearest among the well-off. In the past half-century young adults tended to move from less populous to more populous places, often to attend university. Once they became middle-aged they tended to move to suburban or rural locations. That has become far less likely. Falling mobility seems to reflect, in part, the fact that people who move to big cities tend to stay there, kept by higher wages, better amenities and crime rates in cities that are lower than they used to be.

But for workers without a college education, moving to big cities in the first place may provide no benefit. Building more affordable housing in those cities would allow them to accommodate more people. But the collapse of the urban wage premium for less-educated workers means that the extra housing would mostly attract additional college graduates.

The last mile

For now, technological progress is reinforcing these trends. When a sufficient number of people asked by Census officials to name their career respond with a previously untracked occupation (such as programmer or barista), the officials introduce a new occupational category. Analysing recent additions, Mr Autor and Ms Fournier reckon that new types of jobs fall into three broad categories: frontier work, closely associated with new technologies; wealth work, catering to the needs of well-to-do professionals; and “last-mile jobs”, which Mr Autor characterises as those left over when most of a task has been automated. That includes delivery services, picking packages in Amazon warehouses and scouring social-media posts for offensive content.

Most jobs in the first two of these categories are located in cities, open mainly to holders of college degrees and decently paid (frontier work is particularly lucrative). Only the last-mile jobs are occupied disproportionately by workers without a college education. They are better than nothing, but only just. Both wages and the quality of such jobs are typically low, which is just as well, since they are unlikely to avoid the creeping tide of automation for very long.

Perhaps the past will not prove a prologue. Some futurists, including Daniel Susskind of the University of Oxford, suggest that artificial intelligence may eventually displace highly trained professionals, just as earlier innovations squeezed out others. That might not help left-behind workers but would reduce both inequality (though by levelling down, not up) and the cost of crucial services. Meanwhile, as Mr Autor said, there is no land of opportunity for workers without a college education. That is a dismal state of affairs, and one the thousands of economists in Atlanta are just starting to confront.

0 notes

Link

When the government’s wildly popular program to cover small businesses’ overhead costs during the coronavirus pandemic came back online on Monday, thousands of Main Street businesses were lined up for the 10:30 a.m. starting pistol.

By 1 p.m. on Tuesday, banks had shoveled $52 billion dollars in federally backed small business loans out the door. By the close of business on Wednesday, more than $90 billion had been doled out. Struggling companies’ intense need for capital has had bankers across the country working around the clock to process loan applicants’ paperwork — and fighting government servers that keep crashing under the demand.

The small-business program, branded the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), is one of the biggest cash injections to the U.S. economy in history. The program’s first $349 billion in funding ran out in 14 days, and the second tranche of $310 billion, approved last week, is on track to do the same. The money is being loaned out by 5,300 separate banks without much direction from Washington other than to get the cash moving.

And yet as of today, the taxpayers footing the historic tab have no way of knowing who is getting the cash. Though some large firms that were recipients have been identified by their Securities and Exchange Commission filings — and shamed or bullied into giving back their loan money — the government body overseeing the enormous fund has yet to release any comprehensive list of beneficiaries. Though now-dated information is available on what sectors and states were the program’s biggest winners during the first funding round, it may be months before any complete public accounting takes place for who got what cash and to what end.

“We are missing a critical moment. All this money is going out the door,” says Liz Hempowicz, the director of public policy at the Project on Government Oversight, a nonpartisan watchdog group. “It’s a really live question what oversight is being done at this moment.”

Keep up to date on the growing threat to global health by signing up for our daily coronavirus newsletter.

The Paycheck Protection Program offers eligible businesses with fewer than 500 employees, non-profits and self-employed individuals loans from private lenders that will be forgiven if the firms keep their payrolls steady. In other words, companies can carry unneeded workers for free, a measure aimed at stopping the spiraling unemployment numbers of 26 million and counting.

The loans that went out under the program’s first pot of money came under fire for excluding smaller banks and minority communities. When Congress restocked the fund last week, those concerns yielded carve-outs to help smaller banks participate and offset potential favoritism of banks toward bigger, better-resourced customers. On Wednesday, the program also announced that only banks with assets of less than $1 billion could submit after-hours paperwork between 4 p.m. and midnight, giving smaller banks another advantage and the computer servers a break.

But without any real-time visibility into who is getting the funding, it is impossible to know whether the second tranche of money is avoiding the pitfalls of the first. Immediate disclosures of how the money is being spent was not part of either deal Congress struck for the first or second round of spending. The government, after all, had plenty on its plate and there were legitimate worries that rapid disclosure could put thumbs on the scale of competition. Some borrowers have been identified through SEC filings, but the mom-and-pop shops that were envisioned to be the core beneficiaries of the program aren’t regulated there.

“We know they have to make it public at some point. But they have not made it easy so far,” says Jordan Libowitz, the communications director for Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, a progressive watchdog group.

For now, the most recent public accounting of the program, posted on the Treasury Department’s website, tracks money through April 16. It breaks down the dispersed loans by state and sector, but it does not identify loan recipients, and it only identifies the biggest lenders under the program by a number. (For instance, an unnamed Lender One had an average loan amount of $515,000.) The Small Business Administration (SBA), the federal agency that’s on the hook for reimbursing the banks, offers a little more information about the size of the banks that are lending from the latest funds, but not who’s getting it.

Ultimately, the best source of solid information about the spending is likely to be the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee, a panel established in the broader law that set up the Paycheck Protection Program. After President Donald Trump sidelined the panel’s first leader in a bureaucratic swing, it has an interim chairman, the top watchdog at the Justice Department, and this week hired a top staffer to get work started. Anyone receiving help under any part the relief packages has to report back quarterly to the pandemic panel details about the money and what it’s being used for. The panel in turn will have 30 days to post that online for public review. But the quarter doesn’t end until June 30. The soonest disclosures could happen might be late July or early August for some of the first businesses to access the small business aid.

Congress also created the Office of the Special Inspector General at the Department of Treasury, a new watchdog dedicated to tracking where the pandemic dollars are going. The post, however, requires a Senate confirmation. Trump has selected White House lawyer Brian D. Miller, a former federal prosecutor and previous inspector general. But he faces a tough crowd in the Senate; last year, Miller told the independent Government Accountability Office (GAO) that the White House was done cooperating with its investigation into the withholding of security aid to Ukraine — the event that is central to Trump’s impeachment and acquittal earlier this year.

If Miller wins confirmation, he will have to build his office from scratch. Congress did not include any emergency language for the new watchdog to oversee a separate $500 billion fund that help businesses that fall outside the SBA loan program. That means Miller or anyone else running the office will face routine bureaucratic hurtles for hiring staff. Miller won’t be able to simply bring his inner-circle with him and the positions will have to be posted widely.

The prolonged process will inevitably mean missed opportunities for lawmakers and policy wonks to tinker with the programs as they figure out the most beneficial and effective way to pump more money in the beleaguered economy. Right now, Congress is considering another relief package, but hasn’t yet seen what the first two pots of small business cash has yielded.

“The bottom line is that this pandemic is going to be with us for a very long time,” says Austin Evers, the founder of American Oversight, a liberal group that has peppered the Trump Administration with requests and litigation for public records. “It’s unlikely this is the only financial support that businesses and individuals are going to be receiving. If we can’t see the data for how the first tranche has been spent, we don’t have the tools we need in the future.”

Some in Washington are ready to start cutting checks directly to local relief funds and pull back from the lenders. Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., and Sen. Steve Daines, R-Montana, have worked with Rep. Dan Kildee, D-Mich., on a $50 billion proposal that would give to local pools of money, with the goal of helping small businesses with fewer than 20 employees and those with 50 employees of less in poor neighborhoods.

“Oversight makes programs work better,” says Kildee. “These administrations and these banks will achieve their goals more effectively when they know someone is watching and measuring. If no one’s watching and measuring, things get sloppy.”

Others take a longer view. Former GAO assistant director John Kamensky notes that Congress has already set aside $280 million in oversight for the pandemic response so far and boosted the GAO budget by $20 million, in addition to creating the Treasury’s Special Inspector General position and the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee. On top of that, there’s talk of a 9/11 Commission-style panel, House Democrats’ own inquiry and the already robust oversight operations on the Hill.

“Transparency is going to be there, I think,” says Kamensky, who spent eight years advising former Vice President Al Gore’s Reinventing Government initiative and now is a senior fellow at the IBM Center for the Business of Government. “It’s a matter of getting it timely and getting it clean.”

Please send tips, leads, and stories from the frontlines to [email protected].

0 notes

Link

When the government’s wildly popular program to cover small businesses’ overhead costs during the coronavirus pandemic came back online on Monday, thousands of Main Street businesses were lined up for the 10:30 a.m. starting pistol.

By 1 p.m. on Tuesday, banks had shoveled $52 billion dollars in federally backed small business loans out the door. By the close of business on Wednesday, more than $90 billion had been doled out. Struggling companies’ intense need for capital has had bankers across the country working around the clock to process loan applicants’ paperwork — and fighting government servers that keep crashing under the demand.

The small-business program, branded the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), is one of the biggest cash injections to the U.S. economy in history. The program’s first $349 billion in funding ran out in 14 days, and the second tranche of $310 billion, approved last week, is on track to do the same. The money is being loaned out by 5,300 separate banks without much direction from Washington other than to get the cash moving.

And yet as of today, the taxpayers footing the historic tab have no way of knowing who is getting the cash. Though some large firms that were recipients have been identified by their Securities and Exchange Commission filings — and shamed or bullied into giving back their loan money — the government body overseeing the enormous fund has yet to release any comprehensive list of beneficiaries. Though now-dated information is available on what sectors and states were the program’s biggest winners during the first funding round, it may be months before any complete public accounting takes place for who got what cash and to what end.

“We are missing a critical moment. All this money is going out the door,” says Liz Hempowicz, the director of public policy at the Project on Government Oversight, a nonpartisan watchdog group. “It’s a really live question what oversight is being done at this moment.”

Keep up to date on the growing threat to global health by signing up for our daily coronavirus newsletter.

The Paycheck Protection Program offers eligible businesses with fewer than 500 employees, non-profits and self-employed individuals loans from private lenders that will be forgiven if the firms keep their payrolls steady. In other words, companies can carry unneeded workers for free, a measure aimed at stopping the spiraling unemployment numbers of 26 million and counting.

The loans that went out under the program’s first pot of money came under fire for excluding smaller banks and minority communities. When Congress restocked the fund last week, those concerns yielded carve-outs to help smaller banks participate and offset potential favoritism of banks toward bigger, better-resourced customers. On Wednesday, the program also announced that only banks with assets of less than $1 billion could submit after-hours paperwork between 4 p.m. and midnight, giving smaller banks another advantage and the computer servers a break.

But without any real-time visibility into who is getting the funding, it is impossible to know whether the second tranche of money is avoiding the pitfalls of the first. Immediate disclosures of how the money is being spent was not part of either deal Congress struck for the first or second round of spending. The government, after all, had plenty on its plate and there were legitimate worries that rapid disclosure could put thumbs on the scale of competition. Some borrowers have been identified through SEC filings, but the mom-and-pop shops that were envisioned to be the core beneficiaries of the program aren’t regulated there.

“We know they have to make it public at some point. But they have not made it easy so far,” says Jordan Libowitz, the communications director for Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, a progressive watchdog group.

For now, the most recent public accounting of the program, posted on the Treasury Department’s website, tracks money through April 16. It breaks down the dispersed loans by state and sector, but it does not identify loan recipients, and it only identifies the biggest lenders under the program by a number. (For instance, an unnamed Lender One had an average loan amount of $515,000.) The Small Business Administration (SBA), the federal agency that’s on the hook for reimbursing the banks, offers a little more information about the size of the banks that are lending from the latest funds, but not who’s getting it.

Ultimately, the best source of solid information about the spending is likely to be the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee, a panel established in the broader law that set up the Paycheck Protection Program. After President Donald Trump sidelined the panel’s first leader in a bureaucratic swing, it has an interim chairman, the top watchdog at the Justice Department, and this week hired a top staffer to get work started. Anyone receiving help under any part the relief packages has to report back quarterly to the pandemic panel details about the money and what it’s being used for. The panel in turn will have 30 days to post that online for public review. But the quarter doesn’t end until June 30. The soonest disclosures could happen might be late July or early August for some of the first businesses to access the small business aid.

Congress also created the Office of the Special Inspector General at the Department of Treasury, a new watchdog dedicated to tracking where the pandemic dollars are going. The post, however, requires a Senate confirmation. Trump has selected White House lawyer Brian D. Miller, a former federal prosecutor and previous inspector general. But he faces a tough crowd in the Senate; last year, Miller told the independent Government Accountability Office (GAO) that the White House was done cooperating with its investigation into the withholding of security aid to Ukraine — the event that is central to Trump’s impeachment and acquittal earlier this year.

If Miller wins confirmation, he will have to build his office from scratch. Congress did not include any emergency language for the new watchdog to oversee a separate $500 billion fund that help businesses that fall outside the SBA loan program. That means Miller or anyone else running the office will face routine bureaucratic hurtles for hiring staff. Miller won’t be able to simply bring his inner-circle with him and the positions will have to be posted widely.

The prolonged process will inevitably mean missed opportunities for lawmakers and policy wonks to tinker with the programs as they figure out the most beneficial and effective way to pump more money in the beleaguered economy. Right now, Congress is considering another relief package, but hasn’t yet seen what the first two pots of small business cash has yielded.

“The bottom line is that this pandemic is going to be with us for a very long time,” says Austin Evers, the founder of American Oversight, a liberal group that has peppered the Trump Administration with requests and litigation for public records. “It’s unlikely this is the only financial support that businesses and individuals are going to be receiving. If we can’t see the data for how the first tranche has been spent, we don’t have the tools we need in the future.”

Some in Washington are ready to start cutting checks directly to local relief funds and pull back from the lenders. Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., and Sen. Steve Daines, R-Montana, have worked with Rep. Dan Kildee, D-Mich., on a $50 billion proposal that would give to local pools of money, with the goal of helping small businesses with fewer than 20 employees and those with 50 employees of less in poor neighborhoods.

“Oversight makes programs work better,” says Kildee. “These administrations and these banks will achieve their goals more effectively when they know someone is watching and measuring. If no one’s watching and measuring, things get sloppy.”

Others take a longer view. Former GAO assistant director John Kamensky notes that Congress has already set aside $280 million in oversight for the pandemic response so far and boosted the GAO budget by $20 million, in addition to creating the Treasury’s Special Inspector General position and the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee. On top of that, there’s talk of a 9/11 Commission-style panel, House Democrats’ own inquiry and the already robust oversight operations on the Hill.

“Transparency is going to be there, I think,” says Kamensky, who spent eight years advising former Vice President Al Gore’s Reinventing Government initiative and now is a senior fellow at the IBM Center for the Business of Government. “It’s a matter of getting it timely and getting it clean.”

Please send tips, leads, and stories from the frontlines to [email protected].

0 notes

Text

Trump tiring of Mulvaney

New Post has been published on https://thebiafrastar.com/trump-tiring-of-mulvaney/

Trump tiring of Mulvaney

Acting White House Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney has been increasingly the subject of President Donald Trump’s irritation, revealing a slow deterioration of their relationship. | Win McNamee/Getty Images

White House

But the president is unlikely to replace his acting chief of staff for the foreseeable future, because finding a fourth chief of staff would be a heavy lift.

President Donald Trump’s honeymoon period with Mick Mulvaney is coming to an end.

In recent weeks, Trump has been snapping at his acting chief of staff with some frequency, and expressing greater frustration with him than usual, according to four current and former senior administration officials.

Story Continued Below

Trump has long said that he prefers the flexibility offered by temporary titles, but Mulvaney’s ongoing “acting” status underscores the uphill battle he faces as Trump’s third chief of staff in less than two-and-a-half years. While Mulvaney is not in danger of losing his job any time soon, officials stressed, Trump’s treatment of him still signals to aides the slow deterioration of their relationship has begun.

One White House official called it “inevitable since any chief of staff has to deliver both the good and bad news,” and this president does not like hearing the latter. Other senior administration officials said Trump gets annoyed with almost everyone apart from family members, so measuring someone’s internal standing by how often Trump speaks sharply to him or her is futile.

But speculation about Mulvaney’s standing with Trump jumped into the public eye earlier this month when the president called out his acting chief of staff for coughing during an interview with ABC News. Even though some saw the incident as reflective of Trump’s general disdain for germs, others viewed it as Trump’s private vexation spilling over.

“The president doesn’t have any good reason to dislike Mulvaney in terms of him being disloyal,” said one Republican close to the White House. Still, the Republican added that the president has asked people in recent months what kind of leadership they think Mulvaney is offering in the West Wing and the value he is adding, often a sign the president is souring on a staffer.

More broadly, several staffers have begun to murmur about Mulvaney’s approach to the job, arguing he’s grown too accustomed to the trappings of White House power. Mulvaney and his top aides have stacked the West Wing so far with 11 loyal staffers from the Office of Management and Budget, where he previously worked. Additionally, he has used Camp David — typically a respite for presidents, not staffers — to host three different retreats with White House senior staff, top health care officials and congressional lawmakers. This, combined with his tendency to load up Air Force One trips with favored administration aides, has made him a target of criticism among some West Wing staff.

Mulvaney’s public criticism of his predecessors like John Kelly has also grated on some staffers. Kelly was not popular among West Wing aides by the end, but staffers still consider Mulvaney’s recent barbs unnecessary.

White House press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders did not respond to calls and an email request for comment. Mulvaney, through a top aide, also did not respond to a request for comment.

Despite the frustrations with Mulvaney, Trump is unlikely to replace him for the foreseeable future, several aides said. Ultimately, the president likes the hands-off approach Mulvaney has taken to his schedule, whims and decision-making style. More importantly, Trump is wary to embark on another chief of staff search after the last one played out in the press over several days with two top candidates turning down offers and a raft of negative headlines.

And the conflict-averse president would never tell Mulvaney to his face that he is annoyed, aides said. Instead, Trump shows his frustration by polling staffers and friends about the person, or by making little digs at them. Trump does this either to signal his waning affection, or to assert his dominance over an ally or staffer who Trump feels has gotten too big for his britches, according to two former senior administration officials.

Some staffers thought the verbal reprimand Trump delivered to Mulvaney for coughing was an example of this type of behavior.

Labeled “Coughgate” by some in the Trump orbit, the TV clip showed the president asking his acting chief of staff to leave the room if he needed to cough again. “You just can’t, you just can’t cough,” Trump said toward Mulvaney as he shook his head.

Some Trump allies felt the tone represented the public airing of Trump’s newfound irritation with his acting chief, while others saw it as common practice for the president and germaphobe who does not like shaking hands or being around sick staffers. He doesn’t even like it if people sneeze around him, said one White House aide.

Adding to the percolating Mulvaney backlash are his mixed reviews in steering the White House on policy matters.

Although Mulvaney has long cultivated a reputation as a policy wonk in Washington, Senate Republicanshave not enjoyednegotiating directly with him to try to reach a deal on a looming budget showdown. With deadlines rapidly approaching this fall, the two sides have yet to make significant progress toward an agreement to raise the debt ceiling and lift stiff spending caps.

And Mulvaney’s guidance to Trump during the federal government shutdown in late December and January to win border wall funding waswidely seenas politically harmful to the White House and Republicans — as was Mulvaney’s eventual move to declare a national emergency to try to bypass Congress for wall funds.

Republicans similarly did not like it when Trump pivoted back to trying to repeal Obamacare this spring after the Republicans’ ill-fated efforts to repeal and replace the law during the president’s first year in office. GOP lawmakers, including Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, were irked that Mulvaney had allowed Trump to steer into an issue they felt had damaged the party ahead of the 2018 midterms.

Being Trump’s chief of staff has always been viewed as a semi-thankless job, no matter how one approaches it. Trump demands loyalty from everyone around him but never really returns it, staffers say, and he’s churned through three chiefs of staff in under three years — along with a long list of other top officials like national security adviser, communications director and deputy chief of staff.

Read More

0 notes

Link

Climate scientists told us this week in a long-awaited United Nations report that limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius would require a gargantuan global effort — and that we have roughly 12 years to do it. But how?

One bright spot in the report is that we already have the tools we need.

Let’s make something clear, though: The emissions we need to focus on now are the ones at the industrial, corporate level, not at the individual level.

Scared by that new report on climate change? Here’s what you can do to help:

• Seize the state

• Bring the fossil fuel industry under public ownership, rapidly scale down production

• Fund a massive jobs program to decarbonize every sector of the economy https://t.co/ZZ7lmunfVW

— Kate Scare-onoff (@KateAronoff) October 9, 2018

According to the Carbon Majors Database, 71 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions since 1988 can be traced back to just 100 fossil fuel companies. Hitting the 1.5°C or 2°C goals means these corporations, their customers, and other large enterprises must phase out fossil fuels (more aggressively than what Shell laid out in its vision for a zero-carbon world).

Governments will also have to come up with tax schemes to generate new revenue for investment in and incentives for renewable energy, reforestation, and carbon removal technologies. And we need to vote for leaders who will deliver on them.

The Trump administration is obviously contributing little to these efforts, trying its best to roll back Obama’s suite of climate policies and enable the continuation of fossil fuel dominance. But a growing number of younger leaders around the world understand what’s at stake and are pushing for more ambitious goals.

Here are some examples of strategies that are working and need to be rolled out worldwide:

By adding a cost to emitting greenhouse gases, you create an incentive to produce less of them and switch to alternatives.

It’s hard to convince someone to pay for something if they can get it for free. Right now, much of the world can dump their greenhouse gases in the atmosphere at no charge. And we don’t have many straightforward ways to value the carbon that trees and algae help pull out of the atmosphere.

Though the new Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report didn’t explicitly discuss the economics of fighting climate change, the authors highlighted at a press conference that attaching a price tag to greenhouse gases is a critical step in limiting warming. “Carbon pricing and the right economic signals are going to be part of the mix,” said Jim Skea, co-chair of IPCC Working Group III.

Even fossil fuel giant ExxonMobil is campaigning for a carbon tax.

To date, at least 40 countries have priced carbon in some form. Some have done it through a carbon tax. Cap-and-trade schemes for carbon dioxide are also underway, like the European Union’s Emissions Trading System. China now runs the world’s largest carbon trading market. Even some regions in the United States have cap-and-trade schemes, like the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative among eastern states.

But, as our colleague David Roberts wrote on Twitter, “A price on carbon of some sort is, wonks almost universally agree, an important part of a comprehensive climate strategy. But the details make all the difference in whether it’s regressive or not, effective or not, popular or not, passable or not.”

Shutterstock

Renewable energy sources like wind and solar power have already dropped drastically in price. In the United States, renewables are cost-competitive with fossil fuels in some markets. In Europe, new unsubsidized renewable energy projects are coming online.

From a market standpoint, it might seem like the time is near for pulling the plug on subsidies to renewables. But if your goal is to fight climate change, it makes more sense to keep giving cleaner energy sources a boost.

And the fossil fuel industry is still getting a number of direct and indirect subsidies. In the United States, these subsidies can amount to $20 billion a year. Globally, it’s about $260 billion per year. Getting rid of government support for these fuels seems like a no-brainer. But yes, the massive political influence of fossil fuels means this will continue to be extremely hard.

The world is still opening tens of thousands of coal-fired plants every year.

Each of these plants represents decades of further greenhouse gas emissions. Although the rate of new coal power plants is declining, that’s not enough. We still need to shut down the oldest, dirtiest coal power plants and preventing new ones from coming online.

According to the IPCC, to stay on track for climate goals the world would have to burn one-third of the coal its using by 2030.

And while natural gas emits about half the greenhouse gases of coal, the quantity isn’t zero, so these generators are in the cross-hairs too.

Some countries are already taking steps to shut off fossil fuel power. German Chancellor Angela Merkel has assembled a panel to figure out when the country can close all of its coal plants. The United Kingdom, meanwhile, has pledged to end its coal use by 2025.

Economists have also argued that countries should use supply-side tactics to restrict the supply of fossil fuels in other ways, too: like opting against new oil and gas pipelines, refineries, and export terminals.

Energy efficiency is the lowest of the low-hanging fruit in fighting climate change.

Increasing fuel economy, insulating buildings, and upgrading lighting are all small incremental changes that add up to dramatic reductions in energy use, curbing greenhouse gas emissions.

It’s also often the cheapest tactic.

“The combined evidence suggests that aggressive policies addressing energy efficiency are central in keeping 1.5°C within reach and lowering energy system and mitigation costs,” according to the new IPCC report.

Buildings, for example, account for roughly one-third of global energy use and about a quarter of total greenhouse gas emissions. To stay on track for 1.5°C of warming, indoor heating and cooling demands would have to decline by at least one-third by 2050.

Many countries already have building codes that require new structures to use state-of-the-art HVAC systems, double-pane glass windows, and energy-saving appliances. But most of the buildings that are standing now will still exist in 2050, so retrofitting existing homes and offices to use less energy needs to be a major policy priority.

Another way to use our resources more efficiently is to electrify everything: oil heaters, diesel trucks, gas stoves. That way, as our sources of electricity get cleaner, they pay climate dividends throughout the rest of the electrified economy. And products like electric cars are far more energy-efficient than their gasoline-powered counterparts.

However, we need financing, incentives, and penalties to push the global economy to do more with less.

Perhaps the best tools to fight climate change haven’t been invented yet — a battery that can store gobs of energy for months, a solar panel that’s twice as efficient, a crop that makes biofuels cheaper than petroleum, or something even better, beyond our imaginations.

So while we clamp down on heavy emitters and deploy cleaner alternatives, we also need to come up with new answers to climate change.

That means investing in basic research and development. It also means helping nascent technologies get out of the laboratory and onto the power grid, whether through loans, grants, or regulations.

The United States already has a framework for this. The Department of Energy runs the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E), a small federal program that funds high-risk, high-reward energy projects with an eye toward fighting climate change. It’s backed projects ranging from flow batteries to wide bandgap semiconductors.

While analysts have argued that programs like ARPA-E increase America’s competitiveness and that the world needs more innovation initiatives for clean energy, the Trump administration has repeatedly tried to zero out its $353 million budget. Congress has nonetheless kept it in place and gave the program a boost in the last spending bill.

California-based Proterra has sold hundreds of its all-electric buses. Proterra

Within a few decades, we are likely to see a worldwide transition away from vehicles that run on gas toward ones that use electricity.

But there’s a lot of uncertainty about how quickly it will happen. And governments have to hurry it along by phasing out the production and sale of gas and diesel vehicles altogether and helping consumers purchase EVs instead.

Fortunately, there’s a lot of momentum building. In 2017, both China and India, along with a few European countries, announced plans to end sales of gas and diesel vehicles. China is hustling toward that goal by providing incentives to manufacturers of electric car and bus makers, as well as subsidies to consumers who purchase EVs to the tune of $10,000 per vehicle on average.

The US is lagging, as per usual, despite the fact our transportation sector today emits more carbon than any other sector of the economy. California, however, is going full speed ahead on EV policy. Its target is 5 million zero-emissions vehicles by 2030 and 250,000 zero-emission vehicle chargers — including 10,000 DC fast chargers — by 2025.

A rainforest in Borneo, Malaysia was destroyed to make way for oil palm plantations. Shutterstock

Tropical forests in Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Central Africa are essential for keeping carbon in the ground and maintaining the climate.

And the current rate that we’re clearing them — to make way for cattle ranches, as well as palm oil, soy, and wood products — is putting us on a course for rapid climate change, with intensifying cycles of extreme droughts, more heat, and more forest fires.

All told, deforestation accounts for an estimated 15 percent of total greenhouse gas emissions.

Halting deforestation can’t be done from afar; it requires working closely with local communities who live in and rely on forests. But governments and corporations can also be pressured to buy commodities only from forest regions certified as “deforestation-free.”

Norway, for instance, now has a “zero deforestation policy,” where it has committed to ensuring “that public procurements do not contribute to deforestation of the rainforest.” Hundreds of companies have made zero-deforestation commitments, too, but we still have a long way to go before they’re airtight and working.

If we could stop deforestation, restore some of the forests we’ve cut down, and improve forestry practices, we could remove 7 billion metric tons of carbon from the atmosphere annually — equal to eliminating 1.5 billion cars, according to the Climate and Land Use Alliance.

Nuclear power currently is responsible for about 20 percent of US electricity — and 50 percent of its carbon-free electricity. As Vox’s David Roberts has noted, the US could lose a lot of this power if some 15 to 20 nuclear plants at risk of closing shut down in the next five to 10 years. Which means that, “saving it, or at least as much of it as possible, seems like an obvious and urgent priority for anyone who values decarbonization.”

Fortunately, Dave also looked at how we could keep these plants open. Near the top of the list is a relatively modest national carbon price (see No. 1 above).

But since we can’t count on a carbon price in the immediate future, it’s worth looking at the other state-level hacks — like zero emissions credits, paid for by a small tariff on power bills — already being deployed to keep nuclear plants running.

Other countries are also wrestling with the future of their nuclear plants. Germany committed to shutting down all of its nuclear reactors by 2022, but the country is now likely to miss its emissions reduction targets. France is now weighing whether to extend the operating life of some of its aging nuclear power plants.

Producing animal products, particularly beef and dairy, creates the majority of food-related greenhouse emissions, while the food supply chain overall creates 26 percent of total emissions. The most obvious way to bring these emissions down would be to engineer a massive shift in dietary patterns, reducing our meat and dairy consumption and shrinking the livestock sector.

“GHG emissions cannot be sufficiently mitigated without dietary changes towards more plant-based diets,” as Marco Springmann of the Oxford Martin Program on the Future of Food and co-authors wrote in a paper published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

But again, this is not about individual choices, not about your mother eating more tofu. This is about asking our leaders and institutions to make dietary change a priority to truly shift markets and lower emissions. Trouble is, no country has had significant success yet with reducing its meat consumption. And as Springmann and his co-authors note, “providing information without additional economic or environmental changes has a limited influence on behavior.”

The kinds of changes we need, they write, include “media and education campaigns; labeling and consumer information; fiscal measures, such as taxation, subsidies, and other economic incentives; school and workplace approaches; local environmental changes; and direct restriction and mandates.”

It’s that last one, “direct restriction and mandates,” that’s most interesting, most daring, and most essential to try immediately.

Some countries like China are beginning to work meat consumption reduction goals into their dietary guidelines. The US should do that too in its next update in 2020. There’s also the Cool Food Pledge, a platform launched in September by the World Resources Institute, to help food service providers slash food-related emissions by 25 percent by 2030. So far, a few companies and institutions have signed up, including Morgan Stanley, UC Davis Medical Center, and Genentech.

Companies and governments could also follow WeWork’s lead and stop serving or paying for meat at company events.

We need to launch many more experiments like this because we still have no idea really how to go about dietary change on the scale that’s necessary to reduce livestock-related emissions. And we need to try.

Every scenario outlined by the IPCC report counts on pulling carbon dioxide out of the air. However, many of technologies needed to do this are in their infancy.

Carbon dioxide removal (CDR) tactics range from the straightforward (like planting forests) to the novel (like scrubbing carbon dioxide straight from the air).

Governments will need to invest more in CDR technology to improve its effectiveness and bring down costs. Policies like renewable portfolio standards, feed-in tariffs, and investment tax credits can help drive the deployment of CDR, as Julio Friedmann, a researcher at Columbia University who studies carbon capture, noted in recently in The Hill. But the biggest thing CDR companies need to blossom is a price on carbon.

Dive into the Vox archives to learn more about these issues:

Carbon pricing

https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/2018/7/20/17584376/carbon-tax-congress-republicans-cost-economy

https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/2017/6/15/15796202/map-carbon-pricing-across-the-globe

https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/2018/7/20/17584376/carbon-tax-congress-republicans-cost-economy

Closing coal plants

https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/2018/4/3/17187606/fossil-fuel-supply

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-09-30/coal-pollution-gets-much-deeper-cut-ipcc-report-on-climate-change

Subsidies

https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/2017/10/6/16428458/us-energy-coal-oil-subsidies

https://www.vox.com/2018/5/30/17408602/solar-wind-energy-renewable-subsidy-europe

Carbon dioxide removal

https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/2018/6/14/17445622/direct-air-capture-air-to-fuels-carbon-dioxide-engineering

https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/2017/8/18/16166014/negative-emissions

Nuclear

https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/2018/4/5/17196676/nuclear-power-plants-climate-change-renewables

Original Source -> 10 ways to accelerate progress against global warming

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes

Text

Value-based care – no progress since 1997?

By MATTHEW HOLT

Humana is out with a report saying that its Medicare Advantage members who are covered by value-based care (VBC) arrangements do better and cost less than either their Medicare Advantage members who aren’t or people in regular Medicare FFS. To us wonks this is motherhood, apple pie, etc, particularly as proportionately Humana is the insurer that relies the most on Medicare Advantage for its business and has one of the larger publicity machines behind its innovation group. Not to mention Humana has decent slugs of ownership of at-home doctors group Heal and the now publiciy-traded capitated medical group Oak Street Health.

Human has 4m Medicare advantage members with ~2/3rds of those in value based care arrangements. The report has lots of data about how Humana makes everthing better for those Medicare Advantage members and how VBC shows slightly better outcomes at a lower cost. But that wasn’t really what caught my eye. What did was their chart about how they pay their physicians/medical group

What it says on the surface is that of their Medicare Advantage members, 67% are in VBC arrangements. But that covers a wide range of different payment schemes. The 67% VBC schemes include:

Global capitation for everything 19%

Global cap for everything but not drugs 5%

FFS + care coordination payment + some shared savings 7%

FFS + some share savings 36%

FFS + some bonus 19%

FFS only 14%

What Humana doesn’t say is how much risk the middle group is at. Those are the 7% of PCP groups being paid “FFS + care coordination payment + some shared savings” and the 36% getting “FFS + some share savings.” My guess is not much. So they could have been put in the non VBC group. But the interesting thing is the results.

First up Humana is spending a lot more on primary care for all their VBC providers, 15% of all health care spend vs 6.6% for the FFS group, which is more than double. This is more health policy wonkdom motherhood/apple pie, etc and probably represents a lot of those trips by Oak Street Health coaches to seniors houses fixing their sinks and loose carpets. (A story often told by the Friendly Hills folk in 1994 too).

But then you get into some fuzzy math.

According to Humana their VBC Medicare Advantage members cost 19% less than if they had been in traditional FFS Medicare, and therefore those savings across their 2.4m members in VBC are $4 billion. Well, Brits of a certain age like me are wont to misquote Mandy Rice-Davis — “they would say that wouldn’t they”.

But on the very same page Humana compares the cost of their VBC Medicare Advantage members to those 33% of their Medicare Advantage members in non-VBC arrangements. Ponder this chart a tad.

Yup, that’s right. Despite the strung and dram and excitement about VBC, the cost difference between Humana’s VBC program and its non-VBC program is a rounding error of 0.4%. The $90m saved probably barely covered what they spent on the fancy website & report they wrote about it

Maybe there’s something going on in Humana’s overall approach that means that FFS PCPs in Medicare Advantage practice lower cost medicine that PCPs in regular ol’ Medicare. This might be that some of the prevention, care coordination or utilization review done by the plan has a big impact.

Or it might be that the 19% savings versus regular old Medicare is illusionary.

It’s also a little frustrating that they didn’t break out the difference between the full risk groups and the VBC “lite” who are getting FFS but also some shared savings and/or care coordination payments, but you have to assume there’s a limited difference between them if all VBC is only 0.4% cheaper than non-VBC. Presumably if the full risk groups were way different they would have broken that data out. Hopefully they may release some of the underlying data, but I’m not holding my breath.

Finally, it’s worth remembering how many people are in these arrangements. In 2019 34% of Medicare recipients were in Medicare Advantage. Humana has been one of the most aggressive in its use of value based care so it’s fair to assume that my estimates here are probably at the top end of how Medicare Advantage patients get paid for. So we are talking maybe 67% of 34% of all Medicare recipients in VBC, and only 25% of that 34% = 8.5% in what looks like full risk (including those not at risk for the drugs). This doesn’t count ACOs which Dan O’Neill points out are about another 11m people or about 25% of those not in Medicare Advantage. (Although as far as I can tell Medicare ACOs don’t save bupkiss unless they are run by Aledade).

I did a survey in 1997 which some may recall as the height of the (fake) managed care revolution. Those around at the time may recall that managed care was how the health insurance industry was going to save America after they killed the Clinton plan. (Ian Morrison used to call this “The market is working but managed care sucks”). At the time there was still a lot of excitement about medical groups taking full risk capitation from health plans and then like now there was a raft of newly publicly-traded medical groups that were going to accept full risk capitation, put hospitals and over-priced specialists out of business, and do it all for 30% less. The Advisory Board, bless their very expensive hearts, put out a report called The Grand Alliance which said that 95% of America would soon be under capitation. Yeah, right. Every hospital in America bought their reports for $50k a year and made David Bradley a billionaire while they spent millions on medical groups that they then sold off at a massive loss in the early 2000s. (A process they then reversed in the 2010s but with the clear desire not to accept capitation but to lock up referrals, but I digress!).

In the 1997 IFTF/Harris Health Care Outlook survey I asked doctors how they/their organization got paid. And the answer was that they were at full risk/capitation for ~3.6% of their patients. Bear in mind this is everyone, not just Medicare, so it’s not apples to apples with the Humana data. But if you look at the rest of the 36% of their patients that were “managed care” it kind of compares to the VBC break down from Humana. There’s a lot of “withholds” which was 1990s speak for shared savings and dscounted fee-for-service. The other 65% of Americans were in some level of PPO-based or straight Medicare fee-for-service. Last year I heard BCBS Arizona CEO Pam Kehaly say that despite all the big talk, the industry was at about 10% VBC and the Humana data suggests this is still about right.

So this policy wonk is a bit depressed, and he’s not alone. There’s a little school of rebels (for example Kip Sullivan on THCB last year) saying that Medicare Advantage, capitated primary care and ACOs don’t really move the needle on cost and anyway no one’s really adopted them. On this evidence they’re right.

Matthew Holt is the Publisher of THCB and is still allowed to write for it occasionally

Value-based care – no progress since 1997? published first on https://wittooth.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

Has Canada lost its mojo?: Why tax cuts may not compensate for a lack of entrepreneurial verve

The quip of the week goes to Jack Mintz, an academic at the University of Calgary and the dean of Canadian tax wonks.

“Canada is becoming the Austin Powers of economies — increasingly passé and rapidly losing its mojo,” Mintz wrote in these pages on July 25 while pleading with Finance Minister Bill Morneau to cut taxes on corporate income.

Funny. And like Mike Myers’s groovy British spy, over the top.

There is reason for concern: the Bank of Canada, the International Monetary Fund, and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development all say the Canadian economy is less competitive than it could be. That’s been true for years, but only recently has the problem become acute. The uncertain future of the North American Free Trade Agreement has exposed how little Canada has done to find markets outside the United States. And President Donald Trump’s business-tax cuts eliminated one of Canada’s most important comparative advantages, leaving it with nothing to offset worries over excessive electricity prices, relatively higher wages, and chronically weak productivity rates.

ack Mintz: Morneau admits Canada’s ‘Trumped’ on competitiveness but still won’t fix it

Hey Mr. Trump, when it comes to trade, even you have sacred cows

Still, Mintz and those who share his world view tend to exaggerate the depths of the pit into which our economy has sunk. That wouldn’t matter, expect that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his advisers get obstinate when those they view as less progressive as themselves try to tell them what to do. Consider Morneau’s last budget. The document was all but silent on the question of competitiveness, even though every business lobbyist and economic think tank in the country was screaming for a response to Trumponomics.

“The responsible thing to do is to focus on the facts, not on speculation, anecdotes, and rumour,” Morneau wrote in a commentary for the Financial Post in May. “And the facts are clear: Canada, and Canadians, are competitive.”

That was Morneau sticking it to those who would goad him into a fight by pointing at the scoreboard. The unemployment rate was 5.8 per cent when he wrote those words, the lowest in at least four decades.