#this is combined with his elitist attitudes towards music

Text

podcast where its just interviews with people who have an ok/completely average relationship with their dads taking 30 minutes to an hour psychologically analyzing everything wrong with said dads

#.txt#for me this would look like a discussion on my dads fervent hatred of the bee gees#likely a result of his unaddressed homophobia#and furthered by his complicated relationship with the expectations of traditional masculinity#a relationship which is in turn further complicated by being raised by a single mom in the 70s#this is combined with his elitist attitudes towards music#as a professional musician he believes the beauty in music is in technical mastery and ingenuity#rather than in human expression and Having a Good Time#something we are diametrically opposed on

0 notes

Photo

https://datacide-magazine.com/from-subculture-to-hegemony-transversal-strategies-of-the-new-right-in-neofolk-and-martial-industrial/

From Subculture to Hegemony: Transversal Strategies of the New Right in Neofolk and Martial Industrial

11 Comments

Neo-Folk and Martial Industrial are two sub-categories of Industrial Music, which developed in the 1980’s. Industrial as such was a direction that – parallel to Punk Rock – worked with the latest electronics in order to create an aesthetic of futuristic noise machines of the late 20th century and research extreme zones of contemporary society and history. Throbbing Gristle already thematized concentration camps, serial killers, Aleister Crowley etc by using cut-up techniques of William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin and thus with strategies of liberation from brain washing. Similarly, Cabaret Voltaire were said to wage a “propaganda war against the propaganda war” (Industrial Culture Handbook). With SPK this was combined with a critique of Psychiatry and a presentation of extremes of the body and death. In the 80’s there were agitational and critical bands such as Test Dept., Nocturnal Emissions and Bourbonese Qualk which were often associated with the ever broadening spectrum of “Industrial”. However, with Laibach the critique of totalitarianism became more ambivalent. This ambivalence was at first seemingly shared by Death In June, the band that in many ways was at the origin of what is now considered Neo-Folk and Martial Industrial.

Death In June has already been the subject of an article in datacide by Stewart Home.

Although the band’s name derives from the “night of the long knives” when the SA leadership and other elements in German fascism were liquidated by Hitler and the SS in June 1934, DIJ’s left wing origins as well as their collaboration with a number of musicians not suspected to have far right leanings seemed to suggest to followers of 80’s industrial that their use of fascist imagery had some sort of critical element to it. There was a romantic and fetishistic element to it and and when Tony Wakeford was sacked from the band (supposedly) for his membership in the National Front it seemed to show that indeed they were rejecting politics and their use of fascist themes and imagery was on the level of aesthetic provocation.

In the course of the late 80’s and throughout the 90’s a number of other bands flocked to the use of this strategy creating a small sub-culture heavy with far right symbolisms and content, sometimes more, sometimes less explicit and politically oriented. Although there is no doubt that this scene harbours a lot of entirely “unpolitical” elements, there are definite personal connections to some elements of the organized far right who are trying to use a “metapolitical” strategy of intervention to fight their fascist kulturkampf.

Right wing sub-cultures are still mostly associated with White Power rock, Skinhead and Oi!-music. This has historical reasons. Central in this is the band Skrewdriver around Ian Stuart Donaldson. The first couple of 7”s and the first album came out on the pub/punk rock label Chiswick Records in 1977. Lack of success however made the band dissolve twice until they reformed again in 1982 and released a 12” on Last Resort’s Boot and Braces Records and then a couple of 7”s on the National Front’s White Noise Records. By now they had become the quintessential White Power band and played numerous “Rock Against Communism” festivals, the NF-answer to the much more popular Rock Against Racism festivals at the time. In 1987, Ian Stuart fell out with Patrick Harrington and Derek Holland of the White Noise Club, the National Front’s “musical” arm, and founded his own Blood & Honour network, in which he played a leading role until his death in a car accident in 1993.

Two things have to be stated in our context here:

1. The ludicrous paranoid race hate ramblings present in the lyrics of Skrewdriver and a host of other like-minded bands that joined them just didn’t lead them anywhere in terms of commercial success, which is something Stuart by his own admission wanted to achieve.

2. With that avenue barred, this scene didn’t and doesn’t have problems outing themselves as National Socialists. To present their political ideas they can do without references to obscure authors of the “conservative revolution” or völkish occultists, and are quite happy to chant their primitive slogans undiluted.

The same is true with “National Socialist Black Metal (NSBM), the openly neo-nazi section of the Black Metal scene and certain White Power Noise Bands. There seems to be a competition to pronounce the most inhuman, brutal and anti-Semitic messages. Song titles as “Die Juden sind unser Unglück”, “Systematische Judische Vernichtung” (Deathkey), “Sieg Heil Vaterland”, “Europa Erwache!” (Der Stürmer), “The Whitest Power”, “Blood Banner SS”, “Juda Verrecke” (Streicher) are quite common.

With Neo-Folk and other outgrowths of the Industrial scene this is different. A great importance is attached to avoid being easily associated with the brown swamp. Their attitude is intellectual and elitist with adoration for Ernst Jünger and Julius Evola not Hitler and Mussolini. Even with key figures who have undeniably been members of far right political groups (in Britain this is crystallized around the mid-80’s National Front and its “Political Soldier” faction), there is a surprising eagerness to distance themselves from allegations of “fascism”. This has a historical precedent in the French “Nouvelle Droite” (see appendix) who, motivated to get out of the neo-Nazi cul-de-sac, and on their march through the institutions, tried hard to avoid being tagged fascists while serving old wine in new bottles, or old ideology in new phraseology for to the present day.

Troy Southgate, head of the group HERR, seems particularly eager not to be branded a fascist despite his history as a wanderer from one group of the extreme right to the other (such as the National Front, the International Third Position, the English Nationalist Movement, the National Revolutionary Faction etc). Presumably this is a tactical move not to scare away potential recruits to his more recent “National Anarchist Movement”. With a list of his favorite authors including pre-cursors like Bakunin, Proudhon and Nietzsche, “classic” fascist and National-Bolshevik authors such as Julius Evola, the Strasser Brothers, Ernst Jünger, Martin Heidegger, Gabriele D’Annunzio, Ernst Niekisch, Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, Karl Haushofer, and finally more contemporary fascists and esoteric Hitlerists like Francis Parker Yockey, Miguel Serrano and Savitri Devi, one wonders why he pretends to be so allergic to the f-word. While this is not necessarily a homogenous bunch of authors, and most of them are not “Nazis” in the sense of toeing the line of the NSDAP, all of them (minus the 19th century pre-cursers) can reasonably be called fascist in the sense of using “fascism” as an umbrella term for tendencies including the conservative revolution, national bolshevism, the Hitler-Nazis to the various strains of the contemporary New Right.

Armin Mohler, a historian and speaker of the “conservative revolution” said: “Fascism for me, is when disappointed liberals and disappointed socialists come together for something new. Out of this emerges what is called conservative revolution.” He somewhat modifies this point in 1973/74: “Apart from a few extras from the ‘lunatic fringe’, no one was defining themselves as ‘fascist’ anymore.” He then tries to define what “fascist” means. He chooses a procedural method he terms the “physiognomic approach”: “In any case all attempts to understand fascism from its theoretical declarations, or (which is not the same) to reduce it to a theory, are doomed to fail (…) In this area of politics the relationship to the concept (Begriff) is just instrumental, indirect, retrospective. Preceding there is a decision for a gesture, a rhythm, in short: a style. This style can of course express itself in words – fascism is not mute, on the contrary. It loves words – but they are not there to communicate a logical context”, rather, according to Mohler, they lead “most of the time” to “random and arbitrary results”. “To summarize we can say that fascists can obviously easily accept discrepancies in theory, because their communication is happening in a shorter curve, exactly through ‘style’”. (Von Rechts gesehen, 181f.)

Mussolini declared in an almost more radical fashion: “Fascism is to the highest degree a relativist movement, because it never made the attempt to clothe its multi-layered and powerful mentality in a defined program. Its success lies rather in the fact that it has followed constantly changing individual inspirations (…) Us fascists have always expressed our complete indifference towards any theory…” Mohler (1920-2003) himself was increasingly openly calling himself a fascist towards the end of his life, while the younger “new right” adepts on the contrary try to utilize an ideological fog machine to obscure their positions.

While Southgate only more recently added a musical “career” to his CV, his former comrade in the NF, Tony Wakeford, has been involved with music longer than his involvement with far right politics. In fact, Wakeford did have roots in the far left scene as a member of the Socialist Workers Party when he was in the band Crisis (see Datacide 7). Douglas Pearce was simultaneously in the International Marxist Group, a competing Trotskyist group. Crisis was dissolved apparently out of disillusionment with the left, and Death In June was founded in 1981.

Shortly afterwards Tony Wakeford joined the National Front. The NF had been the most important party of British neo-fascism in the 1970’s. However, in the early 80’s it already was in a state of decline and internal factional disputes. There was soon a de facto split between the “Official NF” and the “Flag Group”. In control of the “Official NF” was the “Political Soldier” faction around Nick Griffin and Patrick Harrington, and it was with this latter faction that Wakeford was sympathizing. Supposedly Wakeford had to leave the band DIJ for this reason, although this seems strange, given that this was right at the point when the NF took a turn to Strasserism, the so-called “left wing” of National Socialism. Douglas Pearce himself said in 1992 that when “searching for a new political perspective we stumbled across nationalist Bolshevism (…) people like Gregor Strasser and Ernst Röhm, who were later known as the ‘second revolutionaries’”.

This is a position that would have been compatible with the “Political Soldiers” from the NF.

The question has to be inserted here: why wasn’t DIJ immediately recognized as a far right band by most people? There are different reasons for this. Their background was explicitly left, texts and imagery seemed to be ambivalent, one wanted to recognize not a glorification but also a critique, and when the band was singing the Horst Wessel Lied, it was seen as a provocation embedded in a historical collage. One could and should have been more critical, but songs like “Death of the West” were serving both “left” and “right”-wing anti-Western resentment. People like John Balance and David Tibet, who seemed unsuspicious, were playing on DIJ records and Douglas Pearce was working for a time in Rough Trade record shop, which was supposed to be politically correct – hadn’t they banned Whitehouse records for the fact the band shared the same address as the fascist League of St. George? And last but not least hadn’t Wakeford been sacked from the band for his involvement with the NF?

After leaving DIJ, Wakeford founded the band Above The Ruins with the bassist Gary Smith of No Remorse, which was an openly neo-nazi band similar to Skrewdriver both in terms of musical style and ideological direction. Above The Ruins released one album and became effectively the first line-up of the new band Sol Invictus, in which Wakeford is still active. Sol Invictus first album was called “Against The Modern World” in homage to Julius Evola, on which Smith still played bass, and was joined by Ian Read and Liz Gray. Wakeford has denied this connection for many years, although there was a re-release of the album in 1996 which was also sold through the Sol Invictus mail order. Above the Ruins featured on a National Front benefit sampler called “No Surrender” alongside the likes of Skrewdriver on the Rock-o-Rama label, who have as recently as 2008 released a track by No Remorse on a 30 years anniversary compilation. Interesting detail: The track “Waiting” had not previously been released on Rock-o-Rama, but was on the “Songs of the Wolf” album. This album, released originally on cassette tape in 1984, then on vinyl in 1986, had already reaped praise in Scorpion magazine from Michael Walker, who is another figure of the British New Right as former NF member.

What is certain is that Wakeford makes some sort of effort at damage control concerning his involvements with the far right. His strategy seems to be to make flimsy disclaimers and otherwise deny everything (see his “Message from Tony” on his website). The legend that he was only briefly involved with far right politics in ca. 1984 doesn’t hold up. His involvement with the NF went back at least two years during which he was a member of DIJ. Wakeford has had many personal involvements with important figures of the far right till at least 1999 when Richard Lawson was best man at his wedding, which also include figures like Patrick Harrington and National Socialist Movement leader Tony Williams. We already encountered Patrick Harrington as one of the organizers of the White Noise Club in the mid 80’s, and he was also a part of the Political Soldier faction of the NF. When this faction split at the end of the decade (leaving the small rump of the NF to the “Flag” group), it produced the International Third Position (Griffin, Holland) and the “Third Way” (Harrington), which is posing as a “think tank” rather than a political group. Harrington remains a confidant of Griffin as the chairman of the fake trade union Solidarity, which is essentially a BNP front. Wakeford was good friends with Harrington and Tony Williams, the future leader of the National Socialist Movement and the person who would issue his NSM membership card to London nail-bomber David Copeland. Wakeford’s other close friend Richard Lawson had a career in the extreme right going back into the 70’s. He was editor of “Britain First” together with Dave McCalden, who became known as a holocaust revisionist, followed the Strasserite split of the short lived National Party. In the 80’s he returned to the “Strasserized” National Front, founded the IONA-Group (Islands of the North Atlantic) and wrote for Scorpion, the magazine of Michael Walker (who was one of the people who safe-housed Italian neo-fascist terrorist Roberto Fiore). In the mid-90’s, Lawson founded the fluxeuropa website and was involved along with Southgate in Alternative Green, the nationalistic spin-off from Green Anarchist. As we can see, Wakeford was surrounded by key figures of the extreme right until the end of the 90’s at least. So it’s not surprising that he spouts on about Europe in true new right fashion in an interview with Jean Louis Vaxelaire, which was published on Lawson’s fluxeuropa site. Wakeford said that Europe was “one of my obsessions”, and slightly distanced himself from 19th century concepts of nationalism by preferring to see “Europe as a collection of regions”, but he then in accordance with the new right decried the “unstoppable” “americanization of European culture.”

Wakeford and Southgate are by no means the only ones involved in the far right. Ian Read, a founding member of Sol Invictus and occasional member of Current 93, who featured on Death In June’s “Brown Book”, founded his own project Fire & Ice in 1990. Known in occult circles for his editorship of Chaos International, his interests are focussed on runes, odinism, nordic mythology, and he thinks of himself as one of the most important occultists of the British Isles. But he too has a history as a far right militant as he acted as security for Michael Walker and Michèle Renouf at events around 1990.

Renouf is one of the leading figures of British holocaust denial and anti-Semites. Amongst other things, she participated in the Teheran holocaust conference, and is one of the most active supporters of David Irving. She also pops up in our context again in 2007 when she spoke at an event of Southgate’s New Right groupuscule, as reported by the anti-Fascist magazine Searchlight. This (and a looming leadership contest) led to disputes within the British National Party, since its culture commissioner, self-declared “philosopher” and “artist” (who made garish oil paintings with titles such as “Adolf and Leni” or “Freud was wrong”) was simultaneously Southgate’s partner in the New Right grouplet. This was at a time when Nick Griffin (former Political Soldier, now BNP chairman and recently elected to the European Parliament) tried to create a more “respectable” image for the party. Of course if leading functionaries rub shoulders with radical anti-Zionists and anti-Semites, who, as Renouf does, believe that “Hamas fights for us all”, then Griffin’s attempt to clear the BNP from charges of anti-Semitism have little credibility.

Back to Neo-Folk: In contrast to “Battlenoise!”, the book titled “Looking For Europe” was received with praise in the scene. The 500 page convolute is stuffed with information on bands and records. It functions a bit like a film documentary cut with snippets of interviews in between the text, and amended with “essays” on the “philosophical” background of the artists. The book title of course is taken from a song by Sol Invictus. All sides of the scene are presented and indeed all kinds of references are mentioned and quoted, but the overall agenda seems to be to discredit the anti-Fascists who are active in monitoring and counter-acting the fascist tendencies in neo-folk. Thus, “Rik” from the fluxeuropa web site comments on whether the Neofolk-scene in England has the reputation of being politically incorrect: “The witch hunters of Political Correctness have their very own and narrow minded political agenda – a kind of ‘social marxism’ – and are not satisfied with anything less than complete compliance with their own values and aims. To justify oneself towards these people would be to play their game, and is ultimately futile. This is why I think we shouldn’t even pose this question.” (p 24) This “Rik” can be none other than Richard Lawson, who we already encountered as NF cadre and IONA founder, but the reader is kept in the dark about these facts. It would be interesting to know if the authors of the book knew this information. If the answer is yes, it would show that they are manipulating the reader on this question; if no, it means they didn’t do their research properly. Either way it illustrates well how the book operates – consciously or not – in its quest to create a whitewashed encyclopedia of Neofolk. Why left wing authors like Martin Büsser or Lars Brinkmann let themselves be instrumentalized remains unclear, but it makes it possible that pretend-equilibrium is created. Most importantly, the involvement of the far right in Neofolk is trivialized and reduced to footnote status.

One other method in this strategy is to present authors such as Ernst Jünger and Julius Evola as heroic mavericks and mystical sages. It is worth briefly looking into their relationships with fascism. Ernst Jünger was active as a publicist and author from the 1920’s onwards on the fringes of the furthest right of the Weimar Republic. He was never a Hitlerite National Socialist, but still he was one of those intellectuals who expected to be the helm of intellectual life after the “German Revolution”. Benn and Heidegger are other examples of this. In 1964, Jünger wrote in his book “Maxima-Minima”: “Revolutions also have a mechanical side”, complaining that the result is that “subaltern” types are coming to the fore. I’m sure he is thinking of the mediocre writers that became national authors of Nazi Germany. Of course Jünger is a stylistic “genius” compared to a Herbert Böhme. It was beneath him to formulate cheap adulations of the “Führer”. Much has been made of Jünger’s supposed refusal to join the Deutsche Akademie der Dichtung when it was purged and then filled with Nazis in the spring of 1933. Fact is that he wasn’t actually invited to join it in May ‘33. One month later, when the NSDAP was already consolidating its power, five more writers were nominated to the Academy. Besides Jakob Schaffner, this also included Jünger. However Jünger got the least number of votes. The poet was insulted and penned a letter of refusal even before the actual invitation arrived. He wrote: “The character of my work lies in its essentially soldierly character, which I do not wish to compromise with academic ties… I ask you therefor to see my refusal as a sacrifice which my participation in the german mobilisation is imposing on myself, in which service I have been active since 1914.” He was obviously offended by the preferential treatment lesser authors were receiving. In any case there is no anti-fascist attitude that can be projected into this statement, and is rather a position that is still consistent with his critique of the Hitlerites from the right.

In his post war writings there is clearly a different tone, and Jünger may well have learned something from the horrors, but it is also possible that a very similar message was encrypted in a different way for a different cultural climate (see the box on “Der Waldgang”). Whatever may be the case, there is definitely no self-critical analysis of his own role in the “german mobilization”. Instead, he often revised his older writings including those versions in his collected works making the texts more compatible for the cultural climate of the post war era. In passing it should be mentioned that Armin Mohler, who was Jünger’s secretary for a while in the early 50’s, turned away from the author exactly for this reason.

Julius Evola was one of the main inspirations for the extreme end of Italian post war fascism. Marginally involved with avant-garde art after WWI, he soon became an ideologist of a radical and anti-Semitic “traditionalism”. That he was not just some random occultist will be clear from the following quote from the preface of the English edition of “Men Among the Ruins”:

“… for us as integral advocates of the “Imperium”, for us as aristocratically inclined, for us as unbending enemies of plebeian politics, of any ‘nationalistic’ ideology, of any and all party ranks and all forms of party ‘spirit’, as well as of any more or less disguised form of democracy, “Fascism is not enough”. We should have wanted a more radical, more fearless, a more absolute fascism that would exist in pure strength and unbending spirit against any compromise, inflamed by a real fire for imperial power. We can never be viewed as ‘anti-Fascists’ except to the extent that ‘super-Fascism’ can be equated with ‘antifascism’.”

Despite this, various protagonists of the neo-folk scene are allowing themselves to present Evola only as an eccentric mystic in order to trivialize what he is really about: “super-fascism”.

Not everybody sees it like that. For example, the Ukrainian academic and fascism scholar Anton Shekhovtsov wrote the article “Apoliteic music: Neo-Folk, Martial Industrial and ‘Metapolitical’ Fascism”, which appeared in “Patterns of Prejudice” magazine in December 2009. His starting point is that in the post war years the radical right had to switch from openly political forms to what he calls “apoliteic” form. Here, he is particularly referring to Evola, Mohler and Jünger. These conservative revolutionaries find themselves in an interregnum until the time would be ripe again for the “glorious” national re-awakening. The metapolitcal fascism of the New Right manifests itself less in the form of parties than in networks of think tanks, conferences, journals, institutes and publishing houses. Shekhovtsov demonstrates how this strategy is at work in Neo-folk and Martial Industrial with bands such as Folkstorm, Death In June, HERR and others. Of course, record labels and distributors, venues and festivals, fashion and fetishism also add to the cohesion of the scene and operate as transmitters of ideas.

We have seen how certain activists of the scene have roots in the political milieu of British neo-fascism, and that their later activities appear not to be “sins of the youth” but rather a conscious change in strategy. This makes it easier to sell records and exert influence, and also makes is possible that the Antifa can be portrayed as “intolerant” and “totalitarian”. The examples shown in this article are by far not the only ones. From the US, examples such as Michael Moynihan, Boyd Rice or Robert Taylor could be examined and would show deep involvement with far right politics, just as the band Von Thronstahl from Germany would. There are numerous other examples. On the other hand, it doesn’t mean that everybody involved in this scene is automatically to be seen as a far right activist. There are even members with years of involvement who seemed to be unaware of the political components. The right wing Gramscian strategy works best when the recipients of the ideas don’t identify them with the hard right, but with “common sense”. This is a very small scene which tries to ennoble its consumers into being supposedly part of some “elite”.

One of the more prevalent opinions on this topic is: as long as these are just the quirks of some pseudo-eccentrics, we shouldn’t care. However, the danger of lies in a camouflaged and sneaking popularisation of ideas as concepts of the New Right can not be underestimated. Caught in the cul-de-sac of “straight” neo-nazi politics, the individuals involved in the far right and neo-folk switched to “metapolitical”, sub-cultural strategies. Therefore, it is absolutely necessary to expose these actual connections, to prompt those in the “grey zone” to distance themselves, and especially to expose the actual arbitrariness and banality of fascist thinking.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

How afrofuturism gives Black people the confidence to survive doubt and anti-Blackness

by Anthony Q. Briggs and Warren Clarke

Afrofuturism, like the kind seen in Marvel’s Black Panther, allows Black people to imagine themselves into the future. Marvel Studios

In 2018, Black people globally got a signal of hope when director Ryan Coogler and Marvel Studios released the critically acclaimed movie, Black Panther. While few knew of the Black Panther as a superhero despite the comic being released in the 1960s, millions now know of him because of the film’s overwhelming success.

Its success can be due, in part, because of what it tells us about Black people’s futures. Many Black people — seeking belonging and better outcomes for their lives — have turned to afrofuturism as the source of optimism. According to afrofuturist expert and author Ytasha Womack, afrofuturism refers to “an intersection of imagination, technology, the future and liberation … Afrofuturists redefine culture and notions of Blackness for today and the future by combining elements of science fiction, historical fiction, speculative fiction, fantasy, afrocentricity and magic realism with non-western beliefs.”

Black Panther had Black people chanting “Wakanda Forever,” while many imagined that they too could put on the Black Panther suit to gain a sense of belonging. Black people, including Canadians, believed that Wakanda, the utopian city where the Black Panther resides, is a real place. For Black Canadians, Wakanda offers a place that exists outside the harsh reality of an anti-Black white settler narrative that is anti-Black.

Black legal scholar Lolita Buckner Inniss says anti-Black racism is deeply enmeshed in the Canadian social fabric. Anti-Black racism cuts deep enough so that many, if not all, Black Canadians feel there is no hope for a better future.

Leaving family but not tradition

Nnedi Okorafor’s Binti must deal with racism and isolation as she traverses a universe that does not value her people’s knowledge. (Tor Books)

Afrofuturism in cinema is but one source. Writer Nnedi Okorafor’s 2015 science fiction novella, Binti, features a Black woman protagonist named Binti Ekeopara Zuzu Dambu Kaipka. Binti is an intelligent woman leader of the Himba tribe whose genius gets her into to the prestigious Oomza University, which floats about the galaxy. Binti is the first member of the Himba ethnic people to attend the school. Her decision to attend is met with ridicule, laughter and threats to her life due to the fear and insecurities of her people.

Her people have never been allowed to imagine futures beyond their traditional way of life and identification with the land. Binti states:

We Himba don’t travel. We stay put. Our ancestral land is life; move away from it and you diminish. We even cover our bodies with it. Otjize is red land. Here in the launch port, most were Khoush and a few other non-Himba. Here, I was an outsider; I was outside.

She echoes the social challenges that Black people face when embarking upon new ways of living after leaving traditional family and cultural contexts. Often, their families and cultures pressure them to remain entrenched within the known confines of family, culture and community, rather than explore the new and unknown.

One of us, Anthony, was the first member of his immediate family to attend post-secondary education and graduate school. He wanted to apply to graduate school but had to fight internalized feelings of low self-worth that insisted he did not belong in academia. Indeed, a lack of self-confidence influenced the choice to avoid applying to programs that required a high grade-point average with a full scholarship because he did not believe he would be accepted.

Blazing a trail to a Black future

In her village, Binti had been one of the few who used knowledge to create peace in her tribe, so she had to overcome pressure to remain in the village in order to embrace new learning. On a spaceship, travelling from her village to the Oomza University, Binti as the only Himba at the university encounters another obstacle: the false assumption that people from her land are evil, dirty and primitive.

In one moment, one of the Khoush (a different lighter-skinned tribe) students touches Binti’s braids out of curiosity and without consent. Her hair is mixed with sweet smelling red clay and perfume called Otijze, which is connected to her cultural heritage. One of the Khoush students responds that it has a horrible smell, suggesting a passive discriminatory logic of sanitation.

One can observe strong echoes of the attitudes of privileged whites towards high-priority Black neighbourhoods whose inhabitants are stereotyped as criminal, irrational, impoverished and unintelligent. The book suggests that there is no such thing as neutral space and that structural inequities and racial inequalities make space and place difficult to navigate, especially in elitist environments.

But Binti is gripped by the challenge of the new. Her journey of self-discovery begins when she decides to leave village life, defying her ancestors’ dedication to their land and cultural identity. Binti explains that tribal knowledge was handed down orally as her father had taught her 300 years of oral lessons “about astrolabes including how they worked, the art of them, the true negotiation of them, the lineage … circuits, wire, metals, oils, heat, electricity, math current and sand bar.” Her mother had also transmitted mathematical insights and gifts, but never in formal educational settings. Family unity and protection were paramount.

Binti symbolizes the trailblazer who encounters politics, racism, stereotypes, ignorance, systemic inequalities, gender inequities, classism and so on. Additionally, she faces the strong pull of past traditions since she is the first member of her family and tribe to attend a formal educational institute.

youtube

Afrofuturism offers a way for Black people to envision their futures, as Missy Elliot’s futuristic music videos exemplify.

Some Black individuals living such stories will inevitably encounter feelings of isolation, lack of belonging and self-doubt. Their internal battles will pit self-trust and the drive towards the new against the safety and security of the past. They will have to develop a secure sense of self and an understanding that it does not matter how far they travel among the galaxies because everyone has unique gifts they can contribute to the universe.

Against the pull of anxieties and insecurities, Anthony graduated with a master’s degree and a PhD; he currently has a post-doctoral fellowship — yet is in another galaxy of his own among the stars.

Afro-Caribbean Black people living in white settler, colonized nations such as Canada face discrimination and negative stereotypes. Afrofuturism can enable Black communities to reimagine new possibilities, especially when the future trajectory for Black Canadians is at times uncertain.

About The Authors:

Anthony Q. Briggs, Research Fellow, Department of Sociology, Anthropology, Social Work and Criminal Justice, Oakland University and Warren Clarke, PhD student, Department of Sociology, Carleton University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: The Use an Abuse of Paint: ‘Fast Forward’ at the Whitney

Eric Fischl, “A Visit To / A Visit From / The Island” (1983), oil on canvas, 84 × 168 inches (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic)

When was the last time you complained that a museum exhibition was too small?

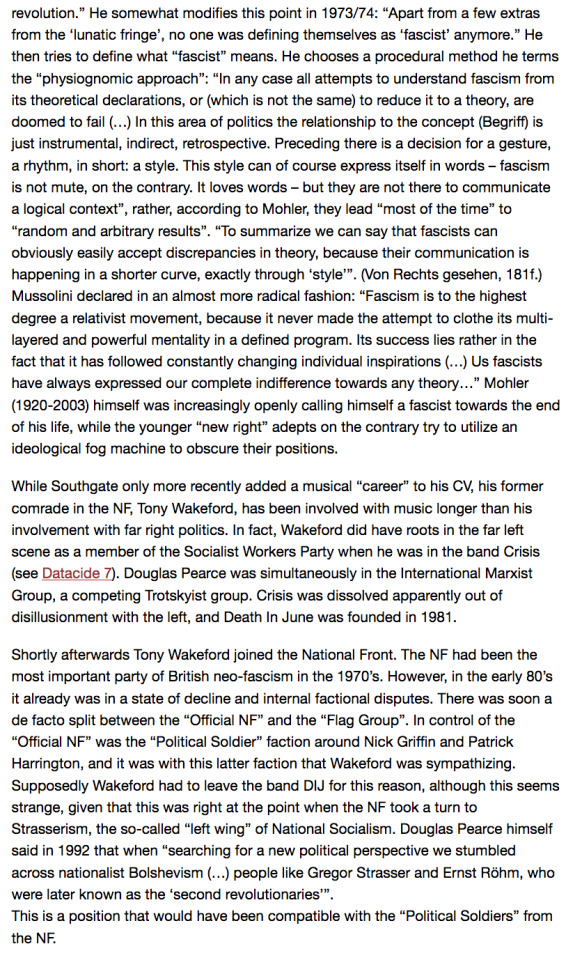

Fast Forward: Painting from the 1980s is installed in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s light-filled 8th-floor gallery — arguably the most gorgeous viewing space of any museum in the city — but for the purposes of the exhibition, it is divided into three moderately sized rooms and a wide, narrow elevator lobby. I would like to have seen this show at least tripled in size across one of the sprawling galleries downstairs.

With the spare allotment of space, is the Whitney hedging its bets on the long-term significance of the work on display? The museum can be commended for its effort to place painting front and center, even as it derives the show’s title from the 1980s video revolution, which has absorbed most of the decade’s critical analysis, but the show feels like something of a missed opportunity. I believe that a case can be made for a deeper and wider examination of the period.

That said, the exhibition, like the decade it represents, is a mixed bag. In a sense, it serves as an institutional chaser for two scrappier, broader, and, taken together, richer examinations of the period that closed in late November, Paradise: underground culture in NYC 1978-84 at Stephen Harvey Fine Art Projects and Something Possible Everywhere: Pier 34 NYC, 1983–84 at the 205 Hudson Street Gallery of Hunter College.

At the Whitney, there are 23 large works hung one or two per wall, while a salon-style installation presents 16 smaller pieces from floor to ceiling. This is a mistake. At the press preview, the curators explained that they decided to display the works in this fashion because they wanted to get away from the “white box” and approximate the free-for-all hangings typical of East Village galleries and countercultural extravaganzas like The Times Square Show (1980).

The main problem with this idea — aside from its denial of the Whitney’s de facto white box ambiance — is that we go to museums to look into, rather than at, works of art. The crowded installations in the raw, stained, and smelly spaces where much of this art had its debut did not consist of the cream of the crop; the Whitney show does. This miscalculation suggests a fundamental misunderstanding that equates a painting with its image, but more on that later.

One service that the exhibition does perform is that it separates American painting of the period from its European counterpart, the transavanguardia whose sound and fury is all but synonymous with art of the ‘80s: Anselm Kiefer, Georg Baselitz, Jörg Immendorff, Francesco Clemente, Enzo Cucchi, Sandro Chia, Mimmo Paladino, the list goes on.

The resulting array of home-grown, almost entirely New York-based work seems lighter in two respects: the feeling that an enormous weight has been lifted, allowing the images of these artists to be seen on their own terms, and correspondingly, that there is something missing — a global dimension or a sense of historical awareness.

The other salutary effect is that the market heavyweights of the time have been set off in their own corners, affording a place in the sun for those who had once been shouldered aside by the Schnabel-Salle-Fischl juggernaut.

The exhibition opens with a fizzy blast of Neo-Pop: a billboard-size canvas by Kenny Scharf, “When the Worlds Collide” (1984), in oil and spray paint, hung against black-and-white vinyl wallpaper adapted from a mural that Keith Haring made for his Pop Shop (1986-2005) in downtown Manhattan.

The Scharf/Haring pairing, combined with Julia Wachtel’s “Membership” (1984), a painting that facilely juxtaposes kitschy greeting card imagery with a black-and-white rendering of matching African fertility figures, seems to signal that the Geist of the decade’s art was bent toward crowd-pleasing hijinks and elitist condescension.

But thankfully, on the opposite side of the exhibition entrance, the Haring wall takes a grittier turn with Jean-Michel Basquiat’s “LNAPRK” (1982), a graffitied, scrawled, and distressed canvas sporting grotesque heads and musical notes. Alongside the Basquiat hangs Haring’s maze-like untitled drawing (1983-84) in fiber-tipped pen on synthetic leather, evoking a Native American hide painting.

Installation view of “Fast Forward: Painting from the 1980s” (2017), Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

The three galleries are thematically arranged: politics; appropriation; and abstraction. The salon-style wall is located in the appropriation room, a correspondence that fits most but not all of the work. The same can be said for the larger paintings as well: an acrylic on canvas of a shuttered storefront, “Closed” (1984-85) by Martin Wong, hangs in the abstraction gallery, but isn’t abstract at all, and only two out of the five paintings in the politics room are overtly political: Leon Golub’s monumental “White Squad I” (1982) and Eric Fischl’s diptych of frolicking vacationers abutted against drowned and desperate refugees, “A Visit To / A Visit From / The Island” (1983).

It quickly becomes apparent, however, that even though a set of paintings may look well together, there can be fundamental differences among them, in both content and form — differences that don’t so much undermine the curatorial structure but speak to the artist’s ability to use the language of paint — to reinvent its application and to put across a construct of ideas.

The two above-mentioned canvases in the politics gallery offer distinct contrasts in attitude and painterly approach. For his depictions of Central American death squads — bands of indiscriminate killers who, with the support of the Reagan administration, spent much of the decade terrorizing the peasantry of Guatemala and El Salvador — Golub rethought the idea of the triumphal frieze, transferring the red oxide of Roman frescoes to his monochromatic fields, while incising his super-sized figures in scraped-down, ever-shifting layers of dark and light.

Golub has cast his gun-toting, khaki-clad thugs as the dominant characters in the scene, leaving their victims virtually anonymous, and all but forcing the viewer to identify with the perpetrators. This standpoint operates collectively and individually, underscoring the culpability of a free and prosperous electorate whose tax dollars are funneled to support atrocities south of the border, as well as the genetic propensity of the human species to abandon mercy and reason for animalistic, tribal instincts. In Golub’s cool-eyed worldview, evil prevails; there is no uplift beyond the painting’s mesmerizing formal strengths. The only vulnerability of power is the extent of its overreach.

Leon Golub, “White Squad I” (1982), acrylic on linen, with metal grommets, 120 × 210 inches

At its best, and “White Squad I” is among his most exceptional works, Golub’s art conveys thorny truths with a sophisticated, stratified sense of nuance that inflects but never tempers his paintings’ overwhelming force. Eric Fischl’s “A Visit To / A Visit From / The Island,” on the other hand, relates to Golub’s work in category but not in kind; instead of the collective responsibility of a democratic society to remain vigilant over the actions of its government, we are presented with limousine liberal guilt over indulging upper-middle-class lotus-eating in climes where the majority of the population is black, destitute, and hopeless.

In contrast to Fischl’s truly disturbing early work — in which prurient, self-lacerating subject matter is underscored by the artist’s attempts at realism via the “Bad Painting” aesthetic defined by the New Museum exhibition of the same name (curated by Marcia Tucker in 1978) — “A Visit To / A Visit From / The Island” is executed in a not-entirely-successful academic technique that possesses none of the material exploration evidenced in Golub’s scoured pigment or the sooty exactitude of Wong’s “Closed.”

While it is tempting to imagine one of its panels bedecked with the buttery lushness and clashing colors of Luisa Chase’s “Limb” (1981), which hangs on an adjacent wall, while the other is painted with the knowing trashiness of Walter Robinson’s borrowed pulp-novel cover art, “Baron Sinister” (1986) from the neighboring appropriation room, it is of course pointless to play “what if” with a firmly established artist’s oeuvre.

Still, in a museum exhibition concentrating on a decade that brought about, in the minds of critics and collectors at least, a revival of image-based painting, the fusion or disconnect that exists between the handling of the medium and the picture it generates deserves special attention.

Like the bits of celluloid that make up a film, the laying-on of paint skews our emotions and layers our perception. Despite the flashiness of Fischl’s diptych as a whole and the undeniable beauty of its portrayal, in the right panel, of black refugees emerging from a black sea under a lowering sky, the blatancy of the political message and the retro quality of the neo-Manet brushwork render it the most incurious work in the show.

Despite the emphasis on subject matter that the decade heralded, the most effective works are those that take painting apart and put it back together again, often leaving traces of the process in scars and ghosts across the surface.

Christopher Wool, “Untitled” (1990), enamel on aluminum, 107 7/8 x 71 3/4 inches

In Christopher Wool’s untitled enamel-on-aluminum painting from 1990, the black-stenciled words “RUN DOG RUN” split and shift down the length of the white surface — a juicy presence in itself augmented by a vestigial “R” from a painted-over “RUN” in the uppermost rank. It is a work that would seem to genuflect before the denatured terms and conditions of mechanical reproduction, but can be fully experienced only in person, a sly subversion of expectations that leads you to look deeper into painting, where the drips hold a sexual charge and swatches of dark blue appear seemingly out of nowhere.

Wool’s painting hangs in the appropriation room, but it feels misplaced there, even though its text comes from an exterior source; its modus operandi is instead the kind of garden-variety appropriation that has been practiced by modernists from Pablo Picasso to Jasper Johns — an instigation for formal inquiry.

The type of appropriation that prevailed in the ‘80s involved a wholesale repurposing of imagery as the work’s primary statement. It has since become a byword for the bulk of Neo-Conceptual art, but its experiment in painting, as manifested here, feels as hermetic as it did when it first hit the scene — despite its aim to reopen art to mass media and the breakneck speed of contemporary life. The paintings in the rooms on either side of the appropriation-based works feel fresh and inquisitive by comparison.

Moira Dryer, “Portrait of a Fingerprint” (1988), casein on plywood, 48 1/8 × 61 1/4 × 4 inches

The exhibition is drawn entirely from the Whitney’s collection, which explains some of its lacunae and odd choices. I was surprised that the curators selected, for the political room, “The Three Graces: Art, Sex and Death” (1981), a candy-colored send-up of a classical theme by Robert Colescott, rather than one of the artist’s many trenchant and disquieting satires on race. But when I checked the Whitney’s website, I discovered that, at least according to the information provided by the collection database, it’s the only Colescott that the museum owns.

To my mind, the salon-style wall is the most problematic aspect of the exhibition; the obstacles it places in the way of absorbing the art is especially self-defeating in light of the high quality of what is on display.

The combo of Joyce Pensato’s untitled mouse head from 1992 (more Ignatz than Mickey) and Elizabeth Murray’s shaped abstraction, “Druid” (1979), smack in the middle of the uppermost reaches of the installation, is an instant eye-magnet, but it would be so much more enriching to experience, in a larger show, these two idiosyncratic artists facing off in a room of their own.

I also wish I could have had a better look at Carroll Dunham’s antic, untitled painting in oil and graphite on wood veneer (1984); Rex Lau’s painted landscape on carved wood, “The Mountain Demons” (1980); and Nellie Mae Rowe’s fanciful, untitled depiction of a woman raising her yellow-gloved hands above her head, which the artist made in 1981, the year before she died at age 82.

And it would have been intriguing to revisit in depth the individualistic, at times bizarre early work of such artists as Jonathan Borofsky, Andrew Masullo, Ida Applebroog, Glenn Ligon, among others, whose inclusion on the salon wall seems to relegate them to a footnote in the larger picture.

One striking omission in the museum’s collection was brought to light by a collaborative lithograph, “The Feminization of Poverty” (1987) by Nancy Spero and Leon Golub, which hangs in the lower right-hand corner of the installation. A quick search of the collection revealed that this is the only work by Spero owned by the Whitney, which makes you hope that the database is incomplete (though the text above the website’s search engine invites us to “browse the full collection”).

Of course, you could fill a pocket-size phone book with the artists who were active during these years but are not included in the exhibition, even Peter Halley and Philip Taaffe, who achieved substantial critical acclaim and market success at the time. Perhaps it would have been more fitting for the Whitney to present Fast Forward as a rotating exhibition, like the wonderful Human Interest portrait show downstairs.

These caveats, however, should not detract from the museum’s efforts to shine a light on the importance of painting in an era that has proven deeply influential on succeeding generations of artists, both inspirationally and critically — an era, it should be kept in mind, whose reactionary policies, as destructive as they were, will be nothing compared to what we are about to undergo.

Perhaps this is why the abstraction room offers such solace and grace. These are paintings, based on the human body, botanical forms, and other sources, that sublimate a storm of emotions into transcendently formal terms, none more than Ross Bleckner’s “Count No Count” (1989) in oil and wax on canvas, a glimmering memorial to those lost to the AIDS epidemic.

No less poignant are Carlos Alfonzo’s “Told” (1990) — an abstracted silhouette of a despairing figure made the year before the artist’s AIDS-related death at the age of 41 — and “Portrait of a Fingerprint” (1988) by Moira Dryer, a green-and-red abstraction in casein on plywood.

Dryer’s life was also cut short, by cancer, when she was 35. Her composition is smeared by solvent on three sides, turning her edge-to-edge horizontal red strokes against a green field into a fog lit by flashing patrol car lights. Dryer’s imagery typically played with dissolution, which we read now, rightly or wrongly, as the slipperiness of mortality and the inadequacy of trying to hold onto anything.

Elsewhere in the room we encounter the feathery whiteness of Susan Rothenberg’s “Tuning Fork” (1980), the zigzagging blue and white bars of Mary Heilmann’s “Big Bill” (1987), and the pollen spores and floating cells of Terry Winters’ “Good Government” (1984) — a title that refers to Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s masterwork “The Effects of Good Government in the City” (1338-1339) in the Sala della Pace in Siena.

We may be tempted to smirk or shrug at the irony of Winters’ title, given what we’ve experienced in the past week alone, though the wall label suggests that the artist was playing it straight:

Winters considered this painting finished only when the elements began to cohere and the composition reminded him “of those maps you saw in grammar school and it said ‘good government’ and everything was working together.”

“Good Government,” which was done in oil on linen, is a tour de force of painterly techniques, where rough-hewn impastos in dark, aggressive earth tones are laid beside delicate stains and linear patterns, while scraped knife strokes in blue and white seem to glow from within. Though at times mottled and choked, it’s the kind painting, along with others in this room, that you would want to linger over, and that’s saying something.

Fast Forward: Painting from the 1980s continues at the Whitney Museum of American Art (99 Gansevoort Street, Meatpacking District, Manhattan) through May 14.

The post The Use an Abuse of Paint: ‘Fast Forward’ at the Whitney appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2kE5FKY

via IFTTT

0 notes